Abstract

Materials that are simultaneously ferromagnetic and ferroelectric – multiferroics – promise the control of disparate ferroic orders, leading to technological advances in microwave magnetoelectric applications and next generation of spintronics. Single-phase multiferroics are challenged by the opposite d-orbital occupations imposed by the two ferroics, and heterogeneous nanocomposite multiferroics demand ingredients’ structural compatibility with the resultant multiferroicity exclusively at inter-materials boundaries. Here we propose the two-dimensional heterostructure multiferroics by stacking up atomic layers of ferromagnetic Cr2Ge2Te6 and ferroelectric In2Se3, thereby leading to all-atomic multiferroicity. Through first-principles density functional theory calculations, we find as In2Se3 reverses its polarization, the magnetism of Cr2Ge2Te6 is switched, and correspondingly In2Se3 becomes a switchable magnetic semiconductor due to proximity effect. This unprecedented multiferroic duality (i.e., switchable ferromagnet and switchable magnetic semiconductor) enables both layers for logic applications. Van der Waals heterostructure multiferroics open the door for exploring the low-dimensional magnetoelectric physics and spintronic applications based on artificial superlattices.

Subject terms: Information storage, Magnetic properties and materials, Two-dimensional materials

Low dimensional multiferroic materials promise the technological advances in next generation spintronic and microwave magnetoelectric devices. Here the authors propose the multiferroicity in the atomically thin ferromagnetic Cr2Ge2Te6/ferroelectric In2Se3 van der Waals heterostructure due to the crosslayer magnetoelectric coupling.

Introduction

Multiferroics, a class of functional materials that simultaneously possess more than one ferroic orders such as ferromagnetism and ferroelectricity, hold great promise in magnetoelectric applications due to the inherent coupling between ferroic orders1–6, leading to technological advances in next generation of spintronics and microwave magnetoelectric devices. However, single-phase multiferroics are challenged by the different ferroics’ contradictory preference on the d-orbital occupation of metal ions: ferroelectricity arising from off-center cations requires empty d-orbitals, whereas ferromagnetism usually results from partially filled d-orbitals7. Conventional perovskite multiferroics (chemical formula: ABO3) have lone-pair-active A-sites which move to off-centers of centrosymmetric crystals for electric polarization, and B-sites with unpaired electrons for magnetic order. Because the ferroelectric and magnetic order in these materials are associated with different ions, the coupling between the ferroic orders are usually weak.

Heterogeneous multiferroics, synthesized composites of two mixed phases8, have the coupling between ferroelectric and magnetic order exclusively at inter-materials boundaries, with magnetoelectric effects occasionally established via interfacial magnetoelastic effect. As an example, magnetic nanopillars could be embedded in ferroelectric matrix. However, these heterogeneous multiferroics stringently demand the constituent materials on their structural similarity, lattice match and chemical compatibility, and have weak magnetoelectric effects limited by the interface/bulk ratios.

Van der Waals (vdW) crystals emerged as ideal material systems with unprecedented freedom for heterostructure construction9. Recent experimental advance discovered ferromagnetism10–12 and ferroelectricity13 in different two-dimensional vdW crystals separately. It remains a paramount challenge to realize multiple ferroic orders in a single-phase 2D material simultaneously14–17, as each order encounters its own challenge (e.g., ferromagnetism in 2D systems suffers from enhanced thermal fluctuations, whereas ferroelectricity the depolarization field). Constructing heterostructures of 2D magnets and 2D ferroelectrics potentially provides a generally applicable route to create 2D multiferroics. However, the fundamental question remains regarding whether the interlayer magnetoelectric coupling can be established, given the presence of the interlayer vdW spacing. If realized, layered heterostructure multiferroics would provide completely new platforms with all atoms participating in the inter-ferroics coupling, and largely reshape the landscape of multiferroics based on vdW superlattices.

Through first-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations based on a bilayer heterostructure of ferromagnetic Cr2Ge2Te6 and ferroelectric In2Se3 monolayers18–21, we discovered a strong interlayer magnetoelectric effect: the reversal electric polarizations in In2Se3 switches the magnetocrystalline anisotropy of Cr2Ge2Te6 between out-of-plane and in-plane orientations. For a 2D ferromagnet, such a change in magnetic anisotropy corresponds to a switching on/off of the ferromagnetic order at finite temperatures, for easy-axis anisotropy opens spin wave excitation gap and thus suppresses the thermal fluctuations, but easy-plane anisotropy does not10,22,23. The switching of ferromagnetic order by electric polarization promises a novel design of magnetic memory. Detailed analysis unraveled the interfacial hybridization as the cause of interlayer magnetoelectric coupling. Furthermore, In2Se3 becomes magnetized due to the proximity to Cr2Ge2Te6, making In2Se3 a single-phase multiferroics (i.e., ferromagnetic and ferroelectric orders coexist in In2Se3), although apparently the magnetization of In2Se3 requires the presence of the adjacent Cr2Ge2Te6. Such multiferroicity duality—that is, the interlayer multiferroicity and the In2Se3 intralayer multiferroicity—provides unique solid-state system in which ferroelectric and ferromagnetic orders interplay inherently. This unusual multiferroicity duality in vdW heterostructures may open avenues for developing new concepts of magnetoelectric devices: using single knob (the orientation of electric polarization in In2Se3) to control the magnetic order in both In2Se3 and Cr2Ge2Te6. We envision the multiferroicity duality potentially enriches the freedom of layer-resolved data storage and that of information processing due to the diverse magnetoelectric and magneto-optic properties of constituent layers.

Results

Material model and computational details

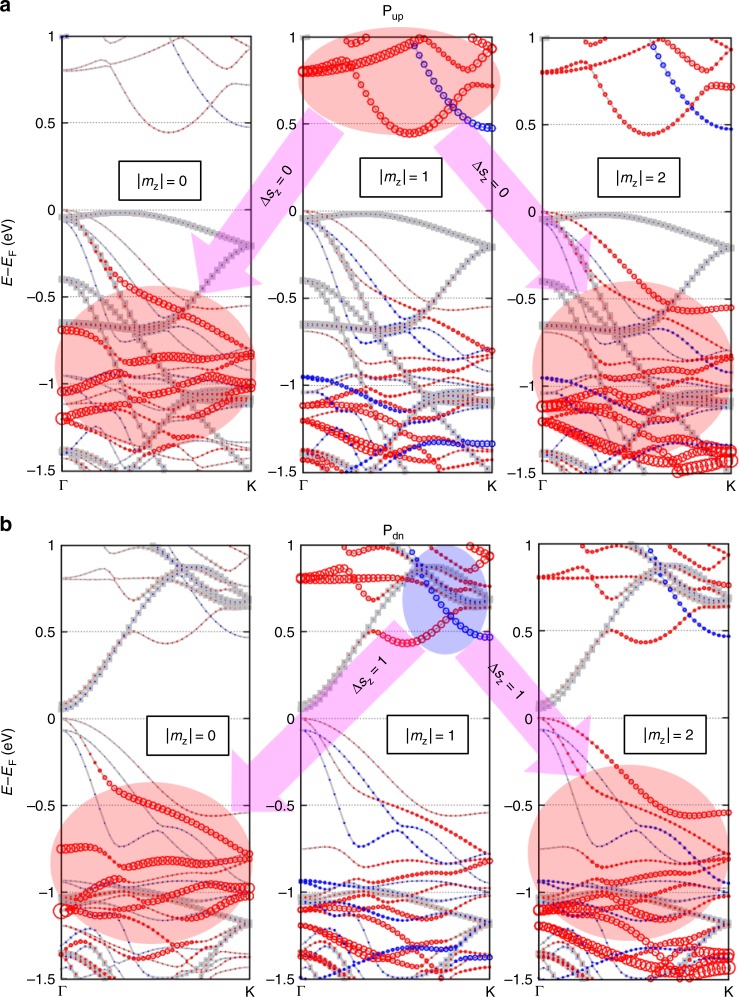

In this work, the lattice constant of Cr2Ge2Te6 adopted the experimental value 6.83 Å and was fixed in heterostructures for the sake of minimizing artifact effects, considering the magnetic properties of 2D Cr2Ge2Te6 are sensitive to structure parameters. It has been reported that a monolayer In2Se3 of either zincblende or wurtzite stacking is unstable with a tendency of the lateral displacement of the top Se layer, leading to the energetically degenerate ferroelectric monolayer18. Although the one relaxed from the zincblende stacking is chosen in this study, it will be also applicable to the other derived from the wurtzite, because the main mechanism to be shown is determined by the interfacial monolayers and thus independent of the detailed stacking type of the multilayer In2Se3. The optimized lattice constant of 1 × 1-In2Se3 (4.106 Å), is strained by −4.0% to match In2Se3- to Cr2Ge2Te6-1 × 1 as shown by Fig. 1a. In heterostructure, the relative spacing and registry between Cr2Ge2Te6 and In2Se3 are adjusted to find the energy minimum configuration. The reversal of the electric polarization of the isolated In2Se3 monolayer can be achieved via lateral displacement of the middle most Se layer, with an energy barrier as small as 0.04 eV per formula unit estimated by nudged elastic band calculation24. In heterostructure, due to the large vdW spacing, the presence of Cr2Ge2Te6 does not noticeably affect the energy barrier of the electric-polarization reversal process of In2Se3. The total energy of the heterostructure is lowest (highest) where the interfacial Te atoms sit at the hollow (top) site of In2Se3, with their relative energy difference amounts to 0.31 and 0.35 eV/u.c. for upward (Fig. 1b) and downward (Fig. 1c) polarizations, respectively. The equilibrium interlayer distance between Cr2Ge2Te6 and In2Se3 at the hollow configuration is 3.20 and 3.14 Å for up and down polarizations of In2Se3, respectively. The total energy of the down polarization (Fig. 1c) is lower by 0.07 eV/u.c. than that of the up polarization (Fig. 1b), due to the stronger interfacial coupling between downpolarized In2Se3 and Cr2Ge2Te6.

Fig. 1.

Van der Waals Cr2Ge2Te6/In2Se3 heterostructure and magnetoelectric coupling. a Lateral unit cell size is chosen to be equal to that of ferromagnetic Cr2Ge2Te6 experimental lattice constant and commensurate to ferroelectric In2Se3- with −4% strain. The interfacial two atomic layers (one atomic layer from each side of the interface) are shown in the top views of Cr2Ge2Te6-1 × 1 (top) and In2Se3- (bottom). b, c Heterostructure side views with the In2Se3 ferroelectric dipole moment directed upward and downward (Pup and Pdn), respectively, and the induced easy-plane and easy-axis Cr spins (SCr). The solid (dashed) arrow of SCr indicates the allowed (prohibited) finite temperature long-range ferromagnetic ordering in 2D systems by the Mermin-Wagner theorem. For each case, the most stable (hollow) and unstable (top) stacking configurations are given

In order to reproduce the experimental magnetic properties of bulk Cr2Ge2Te6, we used small onsite Hubbard U value 0.5 eV and Hund’s coupling J value 0.0 eV for Cr d orbital in DFT calculations (see ref. 10 for the choice of U = 0.5 eV, J = 0.0 eV). This small onsite Columbic interaction is consistent with the fact that Cr2Ge2Te6 is a small band gap material with less localization than Cr-oxides. The ferromagnetic ground state is confirmed with the Cr spin magnetic moment ~3.0 μB. With the spin–orbit coupling (SOC) included, the magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy (MAE) is calculated and defined as , where the former and latter correspond to the total energy with the Cr spins directed in-plane and out-of-plane, respectively. Due to the threefold rational symmetry of Cr2Te2Te6, there is not much magnetic anisotropy within the basal plane. We checked the convergence of MAE carefully, where a large value of K-mesh (12 × 12 × 1) was enough to ensure the error <10 μeV/Cr. For the isolated monolayer Cr2Ge2Te6, our calculated MAE is −70 μeV/Cr, favoring the in-plane direction. In the heterostructures with up- and downpolarized In2Se3, the calculated Cr MAE is −95 and 75 μeV, respectively, whose energetically favorable spin orientations are indicated by SCr in Fig. 1b, c. By modulating the polarization of the adjacent ferroelectric layer, the switching of the magnetization orientation is realized. This has significant application implications: For a 2D magnetic system with easy-plane anisotropy (X–Y model), the finite temperature ferromagnetic order is inhibited, whereas for easy-axis anisotropy (Ising model), the magnetic order can be sustained at finite temperatures. Therefore, in such a heterostructure, multiferroic effect offers a potential route to switch the ferromagnetism for logic devices.

Mechanism for interfacial multiferroicity

The mechanism for electric-polarization dependent MAE is discussed in details. The calculated Cr orbital moment is small (<Lx> = 0.04 μB, <Lz> = 0.01 μB for in-plane, out-of-plane spin directions), which is less likely the origin of MAE. The plausible mechanism is related to the detailed feature of spin-resolved orbital-decomposed band structure25. Starting from the collinear spin band structures, we analyzed the energy correction by the perturbation theory about λL∙S where λ is the radial part of Cr SOC. The orbital moment quenched by the crystal field results in the vanishing first order correction. Assuming the negligible change of the electron correlation energy between [100] and [001] spin directions, one can write the second order contribution to MAE as follows25:

| 1 |

Here the first and second summations correspond to the spin-conserving |Δsz| = 0 and spin-flipping |Δsz| = 1 transitions, and and are valence and conduction band states with spin σ, respectively, whose energy eigenvalues are and . The angular momentum matrix elements of Lz and Lx correspond to transitions with |Δmz| = 0 and |Δmz| = 1, respectively, for Cr d-orbitals. Therefore, for spin-conserving transition, SOC elements between occupied and unoccupied states with the same (different) magnetic quantum number through the operator contributes to positive (negative) MAE. For spin-flipping transition, the contribution to MAE is reversed26.

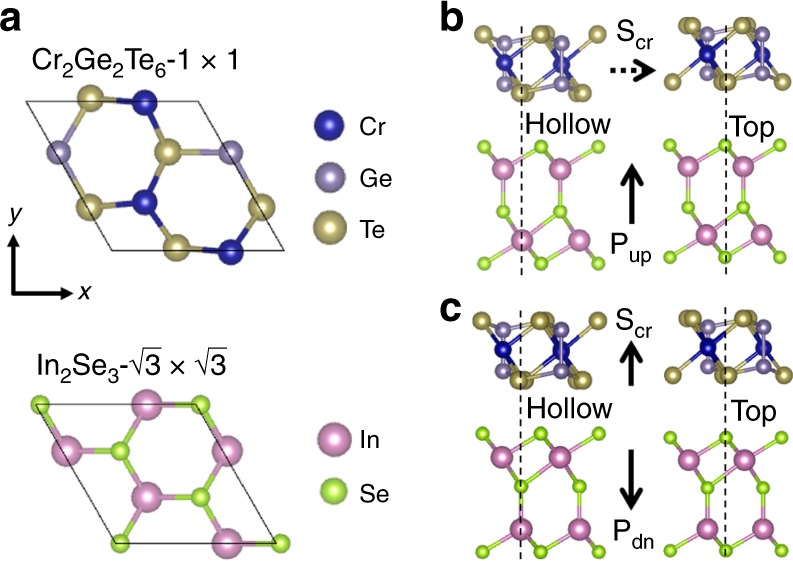

Figure 2a, b shows the spin-resolved orbital-decomposed band structure of heterostructures for up- and downpolarized In2Se3, respectively, where the contribution of Cr d-orbitals is indicated by the circles for |mz| = 0 (z2), 1 (xz and yz), or 2 (x2−y2 and xy). As shown by the arrows in Fig. 2a for the heterostructure with up-polarized In2Se3, our calculated negative MAE mainly originates from the spin-conserving transition from |mz| = 1 to |mz| = 0 or 2, i.e., |Δsz| = 0 and |Δmz| = 1 related to the second term of the first sum in Eq. (1). The mechanism is further confirmed by our results that the Cr MAE changes from about −100 to 200 μeV by intentionally increasing the U value from 0.5 to 2.0 eV: the increased U lowers the energy level of the majority spin in valence bands of |mz| = 0 or 2 (Supplementary Fig. 3), and thus the transition energy gap of |Δsz| = 0 and |Δmz| = 1 is increased and the associated contribution is weakened, leading to the positive MAE.

Fig. 2.

Spin-polarized and Cr d orbital-decomposed band structures of Cr2Ge2Te6/In2Se3 heterostructures. a, b The calculated band structures for the heterostructures with Pup and Pdn In2Se3, respectively. For each electric polarization, the heterostructure (in terms of contact registry and interlayer distance) adopted the configuration of global energy minimum (see Supplementary Fig. 1). The majority and minority spin states are indicated by the red and blue circles, respectively, whose size denotes the contribution of Cr d orbitals with certain azimuthal angular momentum |mz|. In2Se3 states are shown by the gray dots, and the band exhibits the overall shift down by ~1 eV while changing In2Se3 from Pup and Pdn, which indicates a strong In2Se3-polarization dependent interfacial coupling. The pink arrows indicate the SOC elements between empty and filled states, indicated by the red circle for the majority spin or blue for minority, causing the negative or positive value of MAE (see Eq. (1) and text) for (a) or (b), respectively, thus the easy-plane or easy-axis SCr

However, for the heterostructure with downpolarized In2Se3, as shown in Fig. 2b, the conduction band minimum of Cr d |mz| = 1 shows a large gap (~0.2 eV) near 0.5 eV above Fermi level, which is caused by hybridization with the In2Se3 conduction band minimum. Such hybridization results in a significant depletion of |mz| = 1 majority spin DOS (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Hence, the negative contribution to MAE found for the case of up-polarized In2Se3 is suppressed. Meanwhile the minority spin DOS remains almost unchanged for |mz| = 1 (Supplementary Fig. 2a), leading to positive MAE via |Δsz| = 1 and |Δmz| = 1, as illustrated by the arrows in Fig. 2b. Considering the interfacial hybridization depends on the band alignment of In2Se3 and Cr2Ge2Te6, we employed the Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional (HSE06) to recalculate the band properties of the heterostructures. As expected, the calculated band gaps widen compared with the GGA-PBE results, but the key features while In2Se3 reverses its electric orientation from up to down keep the same: the conduction band of In2Se3 moves down to hybridize with the conduction band of Cr2Ge2Te6, as clearly seen in Supplementary Fig. 4.

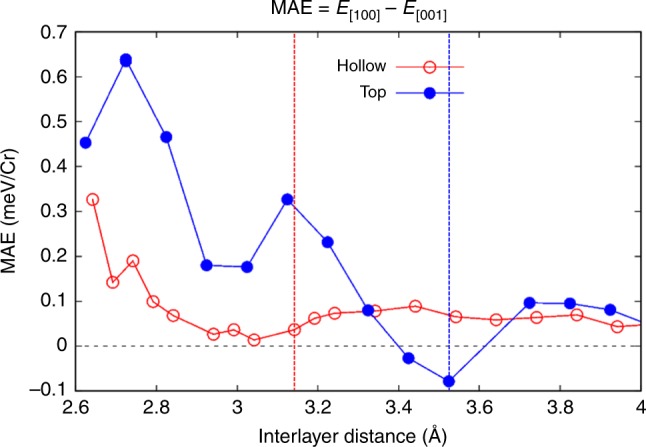

The sign change of Cr2Ge2Te6’s MAE upon the electric-polarization reversal of In2Se3 from up to down arises from the increased coupling, which causes the overall shift down of In2Se3 bands and its enhanced hybridization with Cr2Ge2Te6. This suggests that the positive MAE for the down polarization would be enhanced by a reduced vdW spacing. To confirm this scenario, we did interlayer spacing dependent MAE calculations for hollow configuration as shown in Fig. 3. As the interlayer distance decreases, MAE increases gradually with a slight fluctuation. The fluctuation originates from the detailed variation of energy levels in the spin-polarized band structures. From the same calculation conducted for the top configuration, it exhibits a stronger fluctuation with the interlayer spacing, due to the larger degree of interfacial orbital overlap in top configuration. The same trend of the two curves in Fig. 3 confirms that the increased interlayer hybridization tends to switch the magnetocrystalline anisotropy from easy-plane to easy-axis. Detailed spin-resolved orbital-decomposed analysis in Supplementary Fig. 5 shows that the decreased spin-flipping energy gap near K with decreased interlayer distance contributes to the positive MAE.

Fig. 3.

Calculated magnetocrystalline anisotropy of Cr2Ge2Te6 in the heterostructure versus the vdW interlayer distance. Magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy (MAE) (in meV/Cr) of Cr2Ge2Te6 as a function of the distance to In2Se3 in the Pdn state, showing a gradual increase towards the positive MAE (easy-axis SCr) upon decreasing the distance for both hollow and top stacking configurations. This set of calculations confirmed the scenario that the enhanced interfacial hybridization between Cr2Ge2Te6 and In2Se3 tends to switch the magnetocrystalline anisotropy from easy-plane to easy-axis. The calculation error is reflected by the symbol size (~0.01 meV/Cr). The red and blue dashed lines correspond to the equilibrium interfacial distances for hollow and top stacking configurations, respectively

Magnetized In2Se3 in proximity to Cr2Ge2Te6

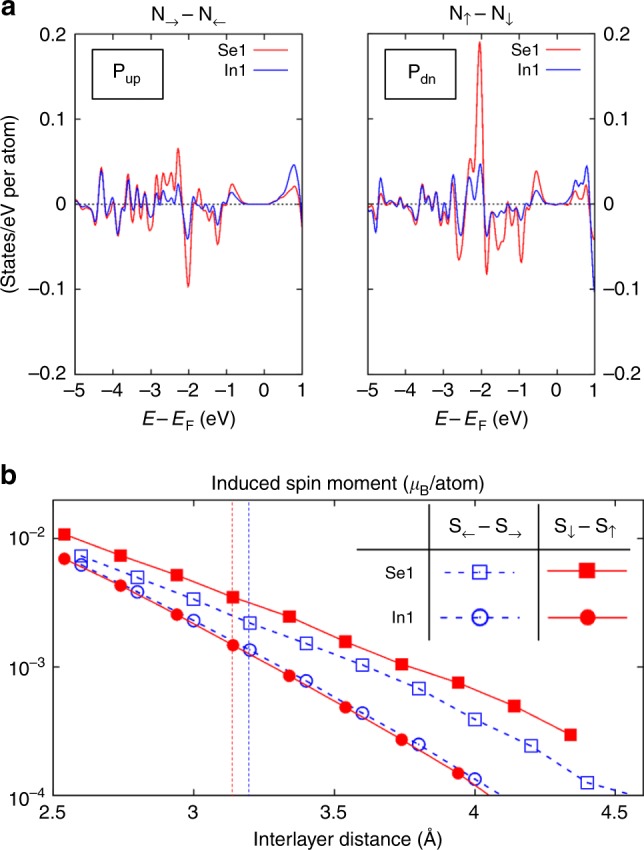

Remarkably, the exchange splitting in Cr d-band magnetizes In2Se3 by the proximity effect. As shown in Fig. 2, the highest valence band has a significant exchange splitting, where the majority-spin band is closer to the Fermi level near Γ. Those states are mainly caused by the surface Te atoms in Cr2Ge2Te6, which means the interfacial Te atoms have the electron spin antiparallel to that of Cr d electrons. Our calculated spin moment per Te atom is −0.11 μBfor In2Se3 of either electric polarizations. Also, the surface In and Se atoms has non-zero spin moments parallel to Te spins induced by the proximity. The spin-resolved DOS of interfacial In and Se, shown in Fig. 4a, confirmed the magnetized In2Se3. It is practically important to note the calculated magnetized In2Se3 here is a ground-state property. At finite temperatures, easy-plane magnetization of 2D In2Se3 is susceptible to thermal fluctuations and long-range order does not exist, but easy-axis magnetization of 2D In2Se3 could sustain the spin polarization at certain finite temperatures. Hence, a switching of 2D magnetic ferroelectric In2Se3 could be realized in this heterostructure multiferroics, leading to a design of spin field-effect transistor27,28.

Fig. 4.

Magnetoelectric effect in In2Se3, mediated by the magnetic proximity to Cr2Ge2Te6. a Projected spin density of states for the surface (Se1) and subsurface (In1) atomic layers close to Cr2Ge2Te6. Left and right panels correspond to the heterostructures with Pup and Pdn In2Se3, respectively, with the in-plane and out-of-plane spin quantization axis. Given the prohibited long-range magnetic order for the easy-plane 2D magnetic system, the spin-polarized In2Se3 as shown by the left panel of (a) is only a ground state at zero Kelvin. But the easy-axis spin-polarized In2Se3 as shown by the right panel of (a) is practical at finite temperatures. Hence, the magnetization of the semiconducting In2Se3 can be switched by its own electric polarization, while in proximity to Cr2Ge2Te6. b Interlayer distance dependence of the proximity-induced Se1 and In1 spin moments. The vertical dashed lines denote the equilibrium distances predicted by PBE with D2 vdW correction. Note that the induced spin moments are negative, which means the interlayer antiferromagnetic proximity effect in the studied In2Se3-Cr2Ge2Te6 heterostructures

The induced spin moment of surface Se is attributed to the exchange coupling J ~ t2/U between Te p and Se p orbitals, with t the hopping constant and U the intra-orbital Coulomb repulsion. In the limit of zero t or infinite U, the system favors the triplet state similar to the atomic Hund coupling, which is the case for Te p and Se p. For a given value of U, the t varies exponentially with the distance. Consistently, our calculations show the exponentially increasing Se spin moment with decreased interfacial distance, as shown in Fig. 4b. The correlation effect should depend on the specific nonlocal correlation functional. For different vdW functionals, the induced spin moments remain at nearly the same magnitude (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Discussion on practical experimental factors

It is of experimental guidance to remark on the possible effects of real material environments. Calculation and analysis in this work are based on the heterostructure of a bilayer system floating in vacuum. In the experimental realization, the initial anisotropy of the magnetic layer Cr2Ge2Te6 could be affected by a few factors, including contacting the materials of large dielectric constants22,29 or large SOC strengths30, unintentional doping31–33 caused by chemicals in device fabrication process, and small amount of artificial strain induced in heterostructure preparation. These factors may affect the resultant magnetoelectric effect quantitatively, as reflected from the calculated MAE of the heterostructures based on the arbitrary sets of U and J values (see Supplementary Fig. 7): the increased U value enhances the out-of-plane anisotropy, while the increased J value enhances the in-plane anisotropy; for any tested set of U and J values, the out-of-plane anisotropy is always enhanced by ~ 0.15 meV/Cr when the In2Se3 dipole is inverted from up to down. Therefore, even if our adopted values of U and J (U = 0.5 eV, J = 0.0 eV) slightly deviate from the exact description of the real heterostructure samples because of the aforementioned complex experimental conditions, the reversal of the In2Se3 polarization from up to down always strengthens the 2D ferromagnetic order in Cr2Ge2Te6. This leads to a general implication: in practice, one can always set a temperature so that 2D ferromagnetism could be found in Pdn-In2Se3-Cr2Ge2Te6 but disappear from Pup-In2Se3-Cr2Ge2Te6, leading to the practical switching experiments at finite temperatures. Therefore, the magnetoelectric effect presented here, based on the modification of MAE by the intricate interface hybridization which further relates to the electric polarization of the 2D ferroelectrics, is an intrinsic interfacial phenomenon.

Summary

We employed first-principles DFT calculations on a vdW heterostructure consisting of ferromagnetic Cr2Ge2Te6 and ferroelectric In2Se3 monolayers. By reversing the electric polarization of In2Se3, the calculated magnetocrystalline anisotropy of Cr2Ge2Te6 changes between easy-axis and easy-plane (i.e., switching on/off of the ferromagnetic order), which promises a novel design of magnetic memory. Furthermore, In2Se3 becomes magnetic ferroelectrics, with switchable spin polarizations according to its own electric polarization. The 2D multiferroic heterostructures would tremendously enlarge the landscape of multiferroics by artificially assembling 2D layers and provide new material platforms for a plethora of emergent interfacial phenomena.

Methods

The DFT method and parameters

All the calculations were performed by the DFT method implemented in Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)34, with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional35 in the scheme of generalized gradient approximation (GGA). The main data was calculated by GGA + U based on the Liechtenstein approach with U = 0.5 eV and J = 0.0 eV. The van der Waals interatomic forces are described by the D2 Grimme method36. The K-mesh of 6 × 6 × 1 and the energy cutoff of 300 eV are used for the structural optimization. The dipole correction is included to exclude spurious dipole–dipole interaction between periodic images.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

C.G., Y.W., and X.Z. acknowledge the support from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division under contract no. DE-AC02-05-CH11231 within the van der Waals Heterostructures program (KCWF16) for the conceptual development and preliminary calculations of 2D heterostructure multiferroics. The support from the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grant 1753380 for the calculation and analysis of 2D magnets and the King Abdulah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) Office of Sponsored Research (OSR) under Award OSR-2016-CRG5- 2996 for the calculation and analysis of 2D ferroelectrics was also acknowledged. G.L. acknowledges the support by the National Research Foundation of Korea (Basic Science Research Program: 2018R1D1A1B07045983) for the systematic computational studies of 2D heterostructure multiferroics. Computation was supported by KISTI (KSC-2018-CRE-0048).

Author contributions

C.G. and X.Z. conceived the project. G.L. and E.M.K. performed the calculations with the close discussions with C.G. C.G., G.L., and X.Z. did data analysis and wrote the paper with the assistance from Y.W.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Geunsik Lee, Email: gslee@unist.ac.kr.

Xiang Zhang, Email: xiang@berkeley.edu.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-10693-0.

References

- 1.Wang J, et al. Epitaxial BiFeO3 multiferroic thin film heterostructures. Science. 2003;299:1719. doi: 10.1126/science.1080615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimura T, et al. Magnetic control of ferroelectric polarization. Nature. 2003;426:55. doi: 10.1038/nature02018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramesh R, Spaldin NA. Multiferroics: progress and prospects in thin films. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:21. doi: 10.1038/nmat1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiebig M, et al. Revival of the magnetoelectric effect. J. Phys. D. 2005;38:R123. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/38/8/R01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiebig M, et al. The evolution of multiferroics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016;1:16046. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheong S-W, Mostovoy M. Multiferroics: a magnetic twist for ferroelectricity. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:13. doi: 10.1038/nmat1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill NA. Why are there so few magnetic ferroelectrics? J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:6694. doi: 10.1021/jp000114x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng H, et al. Multiferroic BaTiO3-CoFe2O4 nanostructures. Science. 2004;303:661. doi: 10.1126/science.1094207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geim AK, Grigorieva IV. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature. 2013;499:419. doi: 10.1038/nature12385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong C, et al. Discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals crystals. Nature. 2017;546:265–269. doi: 10.1038/nature22060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang B, et al. Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a van der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit. Nature. 2017;546:270–273. doi: 10.1038/nature22391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong C, Zhang X. Two-dimensional magnetic crystals and emergent heterostructure devices. Science. 2019;363:eaav4450. doi: 10.1126/science.aav4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu F, et al. Room-temperature ferroelectricity in CuInP2S6 ultrathin flakes. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12357. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seixas L, Rodin AS, Carvalho A, Castro Neto AH. Multiferroic two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;116:206803. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.206803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Qian X. Two-dimensional multiferroics in monolayer group IV monochalcogenides. 2D Mater. 2017;4:015042. doi: 10.1088/2053-1583/4/1/015042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo W, Xu K, Xiang H. Two-dimensional hyperferroelectric metals: a different route to ferromagnetic-ferroelectric multiferroics. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;96:235415. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.96.235415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qi J, Wang H, Chen X, Qian X. Two-dimensional multiferroic semiconductors with coexisting ferroelectricity and ferromagnetism. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018;113:043102. doi: 10.1063/1.5038037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding W, et al. Prediction of intrinsic two-dimensional ferroelectrics in In2Se3 and other III2-VI3 van der Waals materials. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14956. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Y, et al. Out-of-plane piezoelectricity and ferroelectricity in α-layered In2Se3 nanoflakes. Nano Lett. 2017;17:5508–5513. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b02198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui C, et al. Intercorrelated in-plane and out-of-plane ferroelectricity in ultrathin two-dimensional layered semiconductor In2Se3. Nano Lett. 2018;18:1253–1258. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b04852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao J, et al. Intrinsic two-dimensional ferroelectricity with dipole locking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018;120:227601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.227601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mermin ND, Wagner H. Absence of ferromagnetism or antiferromagnetism in one- or two-dimensional isotropic Heisenberg models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1966;17:1133. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.17.1133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruno P. Magnetization and Curie temperature of ferromagnetic ultrathin films: the influence of magnetic anisotropy and dipolar interactions. Mater. Res. Symp. Proc. 1991;231:299–310. doi: 10.1557/PROC-231-299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henkelman G. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 2000;113:9901–9904. doi: 10.1063/1.1329672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D, et al. First-principles theory of surface magnetocrystalline anisotropy and the diatomic-pair model. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;47:14932. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.14932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sui X, et al. Voltage-controllable colossal magnetocrystalline anisotropy in single-layer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;96:041410. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.96.041410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Datta S, Das B. Electronic analog of the electro-optic modulator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1990;56:665–667. doi: 10.1063/1.102730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gong S-J, et al. Electrically induced 2D half-metallic antiferromagnets and spin field effect transistors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:8511–8516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715465115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang S, Shan J, Mak KF. Electric-field switching of two-dimensional van der Waals magnets. Nat. Mater. 2018;17:406–410. doi: 10.1038/s41563-018-0040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avsar A, et al. Spin-orbit proximity effect in graphene. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4875. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang B, et al. Electrical control of 2D magnetism in bilayer CrI3. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018;13:544–548. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang S, Li L, Wang Z, Mak KF, Shan J. Controlling magnetism in 2D CrI3 by electrostatic doping. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018;13:549–553. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Z, et al. Electric-field control of magnetism in a few-layered van der Waals ferromagnetic semiconductor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018;13:554–559. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kresse G, Furthmuller J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996;6:15–50. doi: 10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimme S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comp. Chem. 2006;27:1787. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.