Abstract

Objective(s):

Wounds are physical injuries that cause a disturbance in the normal skin anatomy and function. Also, it has a severe impact on the cost of health care. Wound healing in human and mammalian species is similar and contains a complex and dynamic process consisting of four phases for restoring skin cellular structures and tissue layers. Today, therapeutic approaches using herbal medicine have been considered. Although the benefits of herbal medicine are vast, some medicinal plants have been shown to have wound healing effects in different experimental studies. Therefore, the current review highlights information about the potency of herbal medicine in the experimental surgical skin wound healing.

Materials and Methods:

Electronic database such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Medscape were searched for Iranian medicinal plants with healing activity in experimental surgical skin wounds. In this area, some of the most important papers were included.

Results:

There are numerous Iranian medicinal plants with skin wound healing activity, but clinical application and manufacturing are very low in comparison to the research volume.

Conclusion:

In normal instances, the human/animal body usually can repair tissue damage precisely and completely; therefore, the utilization of herbs is limited to special conditions or in order to accelerate the healing process.

Key Words: Experimental, Iranian medicinal plants, Skin, Surgical, Wound healing

Introduction

The skin is the largest organ of the body and is the first line defense against injury and plays critical roles in maintaining homeostasis (1). A wound is a skin injury that is made by physical, chemical, or microbiological infections at all ages (2). The methods of managing wounds have changed dramatically in recent decades and wound healing is now a challenging global clinical problem. The primary goal is to heal the wound as fast as possible (3). The process of this natural restorative response to tissue injury is very complex, and four precisely and highly programmed phases are involved. They comprise hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and tissue remodeling that must occur in the proper sequence and time frame to create optimal wound healing (1, 3). Some factors such as oxygenation, infection, age, sex, hormones, stress, diabetes, obesity, medications, alcoholism, smoking, and nutrition can affect the wound healing process, causing improper or impaired tissue repair (1, 4).

Animal models are essential biological tools for ensuring the safety and efficacy of human drugs. Humans and animals have similar skin characteristics, therefore, an accurate model of human wound healing was simulated in animals (5). All animal models have been widely used in wound healing studies. Various animal wound models, especially rats and mice, are used to reflect human wound healing problems. Despite species differences, availability and relatively low cost allow rodents to serve as a valuable research tool (6, 7).

Herbal products including plant-derived extracts have long been used in the treatment of wounds and found to possess significant effects on wound healing (3). In recent years, the use of natural products especially those derived from plants has increased. World health organization estimated that more than 80% of the world’s population relies on traditional medicines for various skin diseases (8). On the other hand, there are many reports about medicinal plants affecting the wound healing process. Regardless of production method, formulation, component, antibacterial activity, and possible side effects, the efficacy of herbal extracts has been evaluated in excision, incision, dead space, and burn wound models (3). It has been estimated that 1–3 % of the modern drugs in use are for the treatment of wounds and skin disorders compared to one-third of all traditional medicines (8).

In Iranian herbal remedies, plant extracts have been used for treating a wide range of illnesses. Iran is one of the primary loci for medicinal plants, where now over 8000 species of flowering plants are growing (9). However, despite abundance of papers by Iranian investigators in the field of experimental surgical skin wound healing and herbal remedies, only a few are practically applied in the treatment of patients (unpublished data). Therefore, this review focuses on plants with medicinal properties and represents the significant efficacy of Iranian herbal products in experimental and surgical procedures and discusses their utilization in clinical medicine.

Materials and Methods

We have conducted extensive research in PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Medscape covering years 2000 to 2017 using keywords including experimental, surgical, skin wound healing, Iranian herbal medicine, Iranian ethnopharmacology, and Iranian medicinal plants. Then, the most important papers in the field of experimental surgical procedure were selected. This study was performed based on Iranian articles and Iranian medicinal plants; therefore, any non-Iranian articles were excluded.

Results

Peganum harmala

The extract of Peganum harmala which is commonly called wild rue was studied on skin defects and found to be effective in wound healing, causing a significant decrease in the epithelial gap and an increase in tensile strength of the wounds (10).

Quercus brantii

Evaluation of the efficacy of Quercus brantii or balut on the full-thickness wounds shows significant healing improvement in wound contraction, epithelialization period, hydroxyproline content, and tensile strength as compared with the control group (11).

Quercus persica

Quercus persica also called balut is found in Zagrossian region of Iran. The efficacy of methanolic extract of Q. persica as an antibacterial agent was confirmed in all concentrations, but it is significant in concentrations of 50 and 75 mg/ml. Besides, this extract had a wound healing potency and significant impact on epithelialization and reduction of the epithelial gap (12).

Elaeagnus angustifolia

The wound healing efficacy of Elaeagnus angustifolia or oleaster was tested on full-thickness skin wounds and showed a significant contraction and hydroxyproline increase after 15 days, which means it is probably useful in wound healing (1). In addition, the oleaster leaves water-soluble extract shows a pro-healing effect on experimental wounds and seems to be an available herbal preparation with a reasonable cost (13).

Table 3.

Kinds of wounds discussed in this review

Glycyrrhiza glabra

The effect of Glycyrrhiza glabra root extract (licorice) was tested on skin wounds of rats and rabbits. The results suggested that both licorice root extract and the hydro-alcoholic extract were able to cause the contraction of the wound, epithelialization, and infiltration of fibroblasts (5, 14). Moreover, a combination of licorice with sesame oil was an effective remedy for wound healing in female Holstein calves (15).

Camellia sinensis

The wound healing activity of Camellia sinensis also referred to as green tea was evaluated in Wistar rats; the ethanolic extract could accelerate the healing process (16).

Silybum marianu m

Silybum marianum, which is commonly called silymarin was supposed to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity (17). The application of silymarin on full-thickness wounds in Wistar rats causes increased in the fibroblast count, collagen synthesis, and wound contraction (17). Also, it improved the morphological, biochemical, and biomechanical properties of full-thickness wounds in rats (18).

Vitis vinifera

Wound healing activity of the hydro-alcoholic extract of Vitis vinifera (topical grape) seed was assessed on 20×20 mm square-shaped excision wounds in rabbits. The results show that topical grape was able to increase hydroxyproline and tensile strength of the wound and improve the healing process (19).

Cydonia oblonga

The aqueous extracts of Cydonia oblonga known as quince were prepared and applied on experimental wounds in rabbits, which was able to cause a significant acceleration in wound healing (20). Moreover, quince seed mucilage in 10–20% concentration has a good potential for promoting wound healing in rabbit (21).

Linum usitatissimum

The effect of Linum usitatissimum oil, which is known as flaxseed oil was evaluated on experimental incisions in rats and the results showed suppression of inflammatory process and wound healing acceleration (2).

Artemisia sieberi

Wormwood or Artemisia sieberi, which is mainly found in the Yazd province of Iran was extracted and applied on punch skin wounds. Results suggested that it could increase the fibroblastic population in the wound site and also cause wound contraction and angiogenesis (22).

Echium amoenum

The borage or Echium amoenum is another plant that has a significant level of gamma-linolenic acid, alpha-linolenic acid, and delta-6 fatty acid. The application of this plant on punch wounds in rats shows a decrease in wound size, and it could accelerate wound healing (23).

Allium sativum

Aqueous extract of garlic (Allium sativum) was applied to rectangular wounds in dogs, which resulted in a decrease in the epithelial gap and collagen synthesis (24).

Punica granatum

Ethanolic extract of Punica granatum, also called pomegranate, was prepared and applied on incisions in Wistar rats, which significantly reduced the wound size (8).

Achillea kellalensis

The aqueous extract of Achillea kellalensis (yarrow) showed significant wound healing activity on experimental full-thickness excision wound in male Wistar rats (8).

Achillea millefolium

The wound healing effect of the hydroalcoholic extract of Achillea millefolium was evaluated on full-thickness excision wounds in rabbits, and the concentration of 5% could accelerate the collagenation and proliferation of wound healing (25).

Verbascum thapsus

Verbascum thapsus is a traditional remedy for wound healing, which is commonly called mullein. The application of this plant extract at the concentration of 20% shows a significant wound healing activity in rabbits, making it a promising drug for the future (26).

Hypericum perforatum

Saint John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) can improve tissue regeneration by enhancing fibroblast proliferation (27). H. perforatum hydro-alcoholic extract was prepared and applied to rabbit wounds. As a result, the healing time was decreased, which means this plant could have a potential for wound healing acceleration (28). Moreover, H. perforatum can speed up cesarean wound healing with minimal scar formation (29).

Myrtus communis

The leaves of this plant known as myrtle could cause enhancement of wound contraction and fibroblast cell proliferation, which lead to wound healing (30).

Malva sylvestris

In rural areas of Iran, Malva sylvestris (common mallow) is used for the treatment of burn and cut wound healing. Experimental findings in rats demonstrate that extract of M. sylvestris effectively stimulates wound contraction (31). The beneficial effects of aqueous extract of M. sylvestris on the wound healing process were also evaluated in BALB/c mice (32).

Stachys lavandulifolia

The wound healing potency of Stachys lavandulifolia locally known as betony was investigated in rats using the excision wound model. The extract-treated animals showed about 95% reduction in the wound area compared with 92% for nitrofurazone as a standard drug (33).

Matricaria chamomilla

The extract of Matricaria chamomilla revealed an ability for wound healing in linear incisional wound model (34). The aqueous extract of M. chamomilla was also effective in treatment against acetic acid-induced colitis in rats (35).

Pistacia atlantica

Pistacia atlantica, locally known as mount atlas pistache, is used in traditional Iranian therapies for inflammatory wounds. The role of the hydro-ethanolic extract of P. atlantica was evaluated in excision and incision wounds in rats. The results show that P. atlantica ointment could shorten the inflammation phase by provoking the proliferation of fibroblasts. Moreover, it also promotes neovascularization and angiogenesis (36).

Astragalus gummifer

The wound healing activity of tragacanth (Astragalus gummifer) has been evaluated in full-thickness wounds of albino rats, and the results show skin wound contraction and healing acceleration in this model (37).

Lotus corniculatus (L. corniculatus)

A full-thickness rectangular wound was made in male rats to evaluate the healing effect of the hydro-ethanolic extract of Lotus corniculatus. The results showed that in addition to anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial effects, L. corniculatus is more effective in the healing of the wounds (38).

Plantago lanceolata

The efficacy of plantain (Plantago lanceolata) in the acceleration of wound healing was also evaluated in rats. The wounds with 0.75% P. lanceolata extract dressing had significantly accelerated wound healing enclosure (100% healing) during 14 days (39).

Althaea officinalis

The effect of flower mucilage of Althaea officinalis, commonly known as marshmallow, was evaluated on experimental full-thickness wounds and the results indicated reduction in the duration of wound healing (40).

Aloe littoralis

The significant healing effect of Aloe littoralis raw mucilaginous gel was shown in Wistar rats (41).

Aloe barbandensis

Both aqueous extract and gel of Aloe barbandensis, known as Aloe vera, were also evaluated in experimental wounds in rats, which showed wound contraction and healing acceleration (42, 43). Moreover, re-epithelialization and angiogenesis were significantly improved in the Aloe vera gel group with surgical incisions (44).

Sesamum indicum

Sesame oil extract, which contains sesamin and sesamolin was tested on wounds in Wistar rats, which led to significant wound contraction and a decrease in wound length and healing time (45).

Olea europaea

Oleuropein is the main component of the olive leaf extract (Olea europaea). The application of oleuropein to incision wounds in BALB/c mice showed a significant increase in the contraction of wounds (46).

Herbal marine compound

Herbal marine compound is a drug of marine herbal origin, and various concentrations of this remedy were used for investigation of wound healing in rats. The results suggest that the herbal marine compound could have a dose-dependent effect on healing and contraction of the wound (47). Table 1 shows Iranian medicinal plants with healing activity on experimental surgical skin wounds. Tables 2 and 3 indicate animal species and kind of wounds in the present review, respectively.

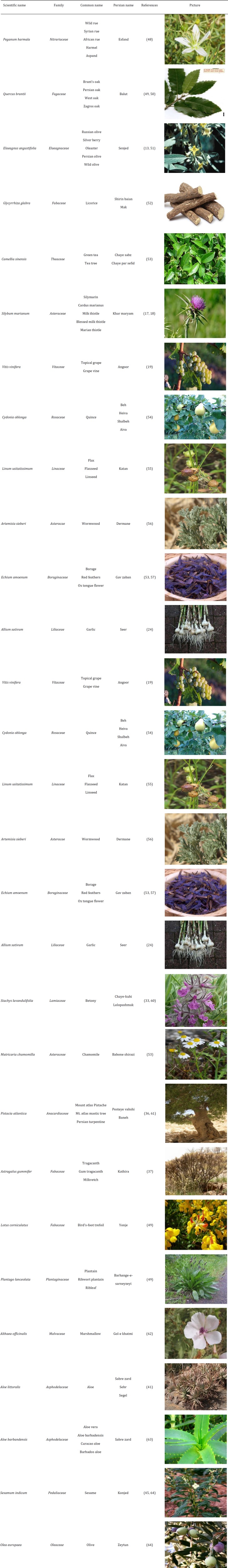

Table 1.

Some Iranian medicinal plants with healing activity on experimental surgical skin wounds

Table 2.

The animal species discussed in this review

Discussion

Wound is a disruption of the anatomical and functional integrity of the living tissue (48). Immediately, after a wound develops, the process of healing begins. Injured tissue goes through four temporal phases to repair the wound: hemostasis, acute inflammation, proliferation (granulation), and remodeling (maturation, contraction). The success of skin wound healing is often determined by whether the process occurs via first or second intention healing. First intention healing in the skin occurs when the edges of a wound site are directly apposed and re-attached and heal to each other rapidly. The wound lacking such close, intimate apposition is termed second intention healing (4, 49, 50). It seems some authors did not pay attention to differences between incision and excision wounds (2, 26). Incision means surgical cut into body tissues, while an excision involves taking the tissue out. So, the application of the term “incision” when the tissue is removed is not correct.

Plants have always been one of the most available resources for treating diseases. Persians were pioneers in applying plants for medicinal treatment. Iran has 11 climates out of the 13 world climates and has 7500–8000 plant species (51). The healing properties of these plant remedies are achieved through their secondary metabolites such as alkaloids, glycosides, flavonoids, saponins, tannins, carbohydrate, and essential oils via anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and anti-bacterial activity, angiogenesis, growth factor enhancement, cellular proliferation, collagen synthesis, re-epithelialization, and tissue remodeling (48). However, there is much still unknown about the role of plants in the treatment of wounds. In this regard, the major limitation is the paucity of clinical studies and the complexity of chemical constituents. As a rule, medicinal plants must be analyzed to identify the main active components (52).

Conclusion

It should be noted that in normal instances the human/animal body usually can repair tissue damages wholly and precisely. Therefore, the utilization of herbs is limited to particular conditions or in order to accelerate the healing process. Now, two fundamental questions must be answered:

1) To what extent the results of these studies can be applied to humans in clinical treatments?

2) To what extent the results of research will lead to the manufacturing of a new drug?

To answer the questions mentioned above will hopefully trigger further research in Iran.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (grant No. 1396-01-106-15062). We would like to thank Dr Ali Akbar Mohammadi in the Burn and Wound Healing Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Science, Shiraz, Iran.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Mehrabani Natanzi M, Pasalar P, Kamalinejad M, Dehpour AR, Tavangar SM, Sharifi R, et al. Effect of aqueous extract of Elaeagnus angustifolia fruit on experimental cutaneous wound healing in rats. Acta Med Iran. 2012;50:589–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farahpour MR, Taghikhani H, Habibi M. Wound healing activity of flaxseed Linum usitatissimum in rats. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;5:2386–2389. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thakur R, Jain N, Pathak R, Sandhu SS. Practices in wound healing studies of plants. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:1–17. doi: 10.1155/2011/438056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo S, Dipietro L. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arzi A, Hemmati A, Amin M. Stimulation of wound healing by licorice in rabbits. Saudi Pharm J. 2003;11:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peplow PV, Chung T-Y, Baxter GD. Laser photobiomodulation of wound healing: a review of experimental studies in mouse and rat animal models. Photomed Laser Surg. 2010;28:291–325. doi: 10.1089/pho.2008.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorsett-Martin WA. Rat models of skin wound healing: a review. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12:591–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.12601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghasemi Pirbalouti A, Koohpayeh A, Karimi I. The wound healing activity of flower extracts of Punica granatum and Achillea kellalensis in Wistar rats. Acta Pol Pharm. 2010;67:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khajoei Nasab F, Khosravi A. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants of Sirjan in Kerman Province, Iran. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;154:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derakhshanfar A, Oloumi M, Mirzaie M. Study on the effect of Peganum harmala extract on experimental skin wound healing in rat: pathological and biomechanical findings. Comp Clin Path. 2010;19:169–172. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemmati AA, Houshmand G, Nemati M, Bahadoram M, Dorestan N, Rashidi-Nooshabadi MR, et al. Wound healing effects of persian oak (Quercus brantii) ointment in rats. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2015;10:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebrahimi A, Khayami M, Nejati V. Evaluation of the antibacterial and wound healing activity of Quercus persica. J Basic Appl Sci. 2012;8:118–123. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oloumi MM, Derakhshanfar A, Molaei MM, Falahi P. The healing potential of oleaster leave water-soluble extract on experimental skin wounds in the rat. Iran J Vet Surg. 2007;2:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oloumi MM, Derakhshanfar A, Nikpoor A. Healing potential of liquorice root extract on dermal wounds in rats. J Vet Res. 2007;62:147–154. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oloumi M, Derakhshanfar A. The role of a liquorice preparation in healing of experimental wounds in calves: a histopathologic study. Vet Dermatol. 2004;15:41–41. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asadi SY, Parsaei P, Karimi M, Ezzati S, Zamiri A, Mohammadizadeh F, et al. Effect of green tea (Camellia sinensis) extract on healing process of surgical wounds in rat. Int J Surg. 2013;11:332–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashkani-Esfahani S, Emami Y, Esmaeilzadeh E, Bagheri F, Namazi MR, Keshtkar M, et al. Silymarin enhanced fibroblast proliferation and tissue regeneration in full thickness skin wounds in rat models; a stereological study. J Dermatol Dermatol Surg. 2013;17:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oryan A, Tabatabaei Naeini A, Moshiri A, Mohammadalipour A, Tabandeh M. Modulation of cutaneous wound healing by silymarin in rats. J Wound Care. 2012;21:457–464. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2012.21.9.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemmati AA, Aghel N, Rashidi I, Gholampur-Aghdami A. Topical grape (Vitis vinifera) seed extract promotes repair of full thickness wound in rabbit. Int Wound J. 2011;8:514–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemmati A, Mohammadian F. An investigation into the effects of mucilage of quince seeds on wound healing in rabbit. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2000;7:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamri P, Hemmati A, Ghafourian Boroujerdnia M. Wound healing properties of quince seed mucilage: In vivo evaluation in rabbit full-thickness wound model. Int J Surg. 2014;12:843–847. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derakhshanfar A, Oloumi MM, Kabootari J, Arab HA. Histopathological and biomedical study on the effect of Artemisia sieberi extract on experimental skin wound healing in rat. Iran J Vet Surg. 2006;1:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farahpour MR, Mavaddati AH. Effects of borage extract in rat skin wound healing model, histopathological study. J Med Plant Res. 2012;6:651–656. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saifzadeh S, Tehrani A, Shokouhi Sabet Jalali F, Oroujzadeh R. Enhancing effect of aqueous garlic extract on wound healing in the dog: clinical and histopathological studies. J Anim Vet Adv. 2006;12:1101–1104. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemmati A, Arzi A, Amin M. Effect of Achillea millefolium extract in wound healing of rabbit. J Nat Remedies. 2002;2:164–167. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehdinezhad B, Rezaei A, Mohajeri D, Ashrafi A, Asmarian S, Sohrabi-Haghdost I, et al. Comparison of in-vivo wound healing activity of Verbascum thapsus flower extract with zinc oxide on experimental wound model in rabbits. Adv Environ Biol. 2011;5:1501–1509. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadollah-Damavandi S, Chavoshi-Nejad M, Jangholi E, Nekouyian N, Hosseini S, Seifaee A, et al. Topical Hypericum perforatum improves tissue regeneration in full-thickness excisional wounds in diabetic rat model. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2015/245328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemmati A, Rashidi I, Jafari M. Promotion of wound healing by Hypericum perforatum extract in rabbit. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2007;2007:78–86. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samadi S, Khadivzadeh T, Emami A, Moosavi NS, Tafaghodi M, Behnam HR. The effect of Hypericum perforatum on the wound healing and scar of cesarean. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:113–117. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rezaie A, Mohajeri D, Khamene B, Nazeri M, Shishehgar R, Zakhireh S. Effect of Myrtus communis on healing of the experimental skin wounds on rats and its comparison with zinc oxide. Curr Res J Biol Sci. 2012;4:176–185. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghasemi Pirbalouti A, Azizi S, Koohpayeh A, Hamedi B. Wound healing activity of Malva sylvestris and Punica granatum in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Acta Pol Pharm. 2010;67:511–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Afshar M, Ravarian B, Zardast M, Moallem SA, Fard MH, Valavi M. Evaluation of cutaneous wound healing activity of Malva sylvestris aqueous extract in BALB/c mice. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2015;18:616–622. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghasemi Pirbalouti A, Koohpyeh A. Wound healing activity of extracts of Malva sylvestris and Stachys lavandulifolia. Int J Biol. 2011;3:174–179. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jarrahi M, Vafaei AA, Taherian AA, Miladi H, Rashidi Pour A. Evaluation of topical Matricaria chamomilla extract activity on linear incisional wound healing in albino rats. Nat Prod Res. 2010;24:697–702. doi: 10.1080/14786410701654875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmadi Nejad S, Abbasnejad M, Derakhshanfar A, Esmaili Mehani S, Kohpeyma H. The effect of intracolonic Matricaria recutita aqueous extract on acetic acid–induced ulcerative colitis in adult male rats. Govaresh. 2014;19:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farahpour MR, Mirzakhani N, Doostmohammadi J, Ebrahimzadeh M. Hydroethanolic Pistacia atlantica hulls extract improved wound healing process; evidence for mast cells infiltration, angiogenesis and RNA stability. Int J Surg. 2015;17:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fayazzadeh E, Rahimpour S, Ahmadi SM, Farzampour S, Anvari MS, Boroumand MA, et al. Acceleration of skin wound healing with tragacanth (astragalus) preparation: an experimental pilot study in rats. Acta Med Iran. 2014;52:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asadbegi M, Mirazi N, Vatanchian M, Gharib A. Comparing the healing effect of Lotus corniculatus hydroethanolic extract and phenytoin cream 1% on the rat’s skin wound: a morphometrical and histopathological study. J Chem Pharm Sci. 2016;9:746–752. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farahpour MR, Amniattalab A, Najad HI. Histological evaluation of Plantago lanceolata extract in accelerating wound healing. J Med Plant Res. 2012;6:4844–4847. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valizadeh R, Hemmati AA, Houshmand G, Bayat S, Bahadoram M. Wound healing potential of Althaea officinalis flower mucilage in rabbit full thickness wounds. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2015;5:937–943. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haj-Hashemi V, Ghannadi A, Heidari A. Anti-inflammatory and wound healing activities of Aloe littoralis in rats. Res Pharm Sci. 2012;7:73–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oryan A, Naeini A, Nikahval B, Gorjian E. Effect of aqueous extract of Aloe vera on experimental cutaneous wound healing in rat. Vet Arh. 2010;80:509–522. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takzare N, Hosseini M-j, Hasanzadeh G, Mortazavi H, Takzare A, Habibi P. Influence of aloe vera gel on dermal wound healing process in rat. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2009;19:73–77. doi: 10.1080/15376510802442444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tarameshloo M, Norouzian M, Zarein-Dolab S, Dadpay M, Mohsenifar J, Gazor R. Aloe vera gel and thyroid hormone cream may improve wound healing in Wistar rats. Anat Cell Biol. 2012;45:170–177. doi: 10.5115/acb.2012.45.3.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharif MR, Alizargar J, Sharif A. Evaluation of the wound healing activity of sesame oil extract in rats. World J Med Sci. 2013;9:74–78. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mehraein F, Sarbishegi M, Aslani A. Evaluation of effect of oleuropein on skin wound healing in aged male BALB/c mice. Cell J. 2014;16:25–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alizadeh AM, Ahmadi A, Mohammadzadeh M, Paknejad M, Mohagheghi M. The effect of HESA-A, an herbal-marine compound, on wound healing process: an experimental study. Res J Biol Sci. 2009;4:298–302. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghasemi M, Ghasemi N, Azimi-Amin J. Adsorbent ability of treated Peganum harmala-L seeds for the removal of Ni (II) from aqueous solutions: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. Indian J Mater Sci. 2014;2014:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohammadi H-a, Sajjadi S-E, Noroozi M, Mirhosseini M. Collection and assessment of traditional medicinal plants used by the indigenous people of Dastena in Iran. J Herbmed Pharmacol. 2016;5:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jalilian Tabar F, Lorestani A, Gholami R, Behzadi A, Fereidoni M. Physical and mechanical properties of oak (Quercus Persica) fruits. Agric Eng Int. 2012;13:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niknam F, Azadi A, Barzegar A, Faridi P, Tanideh N, Zarshenas MM. Phytochemistry and phytotherapeutic aspects of Elaeagnus angustifolia. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2016;13:199–210. doi: 10.2174/1570163813666160905115325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bahmani M, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Jeloudari M, Eftekhari Z, Delfan B, Zargaran A, et al. A review of the health effects and uses of drugs of plant licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) in Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2014;4:847–849. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nabati F, Mojab F, Habibi-Rezaei M, Bagherzadeh K, Amanlou M, Yousefi B. Large scale screening of commonly used Iranian traditional medicinal plants against urease activity. DARU. 2012;20:72–80. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-20-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gharaghani A, Solhjoo S, Oraguzie N. A review of genetic resources of pome fruits in Iran. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2016;63:151–172. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Masoomi F, Feyzabadi Z, Hamedi S, Jokar A, Sadeghpour O, Toliyat T, et al. Constipation and laxative herbs in Iranian traditional medicine. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sefidkon F, Jalili A, Mirhaji T. Essential oil composition of three Artemisia spp. from Iran. Flavour Fragr J. 2002;17:150–152. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moallem SA, Hosseinzadeh H, Ghoncheh F. Evaluation of antidepressant effects of aerial parts of Echium vulgare on mice. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2007;10:189–196. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Safavi K, Rajaian H, Nazifi S. The effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Punica granatum flower on coagulation parameters in rats. Comp Clin Path. 2014;23:1757–1762. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farhadi A, Eftekhari Z, Shahsavari F, Joudaki Y, Pour-Anbari P, Bahmani M, et al. The most important medicinal plants affecting the brain and nerves: an overview on Iranian ethnobotanical sources. Der Pharma Chemica. 2016;8:269–274. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Javidnia K, Mojab F, Mojahedi S. Chemical constituents of the essential oil of Stachys lavandulifolia from Iran. Iran J Pharm Res. 2004;3:61–63. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fathi Rezaei P, Fouladdel S, Hassani S, Yousefbeyk F, Ghaffari SM, Amin G, et al. Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by pericarp polyphenol-rich extract of Baneh in human colon carcinoma HT29 cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:1054–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valiei M, Shafaghat A, Salimi F. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the flower and root hexane extracts of Althaea officinalis in Northwest Iran. J Med Plant Res. 2011;5:6972–6976. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mikaili P, Shayegh J, Asghari MH, Sarahroodi S, Sharifi M. Currently used traditional phytomedicines with hot nature in Iran. Biol Res. 2011;2:56–68. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mikaili P, Shayegh J, Sarahroodi S, Sharifi M. Pharmacological properties of herbal oil extracts used in Iranian traditional medicine. Adv Environ Biol. 2012;6:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Farzaei H, Abbasabadi Z, Shams-Ardekani R, Abdollahi M, Rahimi R. A comprehensive review of plants and their active constituents with wound healing activity in traditional Iranian medicine. Wounds. 2014;26:197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eming SA, Martin P, Tomic-Canic M. Wound repair and regeneration: mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:1–36. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Y, Beekman J, Hew J, Jackson S, Issler-Fisher AC, Parungao R, et al. Burn injury: challenges and advances in burn wound healing, infection, pain and scarring. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018;123:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sharafzadeh S, Alizadeh O. Some medicinal plants cultivated in Iran. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2012;2:134–137. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pazyar N, Yaghoobi R, Rafiee E, Mehrabian A, Feily A. Skin wound healing and phytomedicine: a review. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;27:303–310. doi: 10.1159/000357477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]