Abstract

Objective:

Increasing evidence suggests that mindfulness- and acceptance-based psychotherapies (MABTs) for bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge-eating disorder (BED) may be efficacious however little is known about their active treatment components or for whom they may be most effective.

Methods:

We systematically identified clinical trials testing MABTs for BN or BED through PsychINFO and Google Scholar. Publications were categorized according to analyses of mechanisms of action and moderators of treatment outcome.

Results:

Thirty-nine publications met inclusion criteria. Twenty-seven included analyses of therapeutic mechanisms and five examined moderators of treatment outcome. Changes were largely consistent with hypothesized mechanisms of MABTs, but substandard mediation analyses, inconsistent measurement tools, and infrequent use of mid-treatment assessment points limited our ability to make strong inferences.

Discussion:

Analyses of mechanisms of action and moderators of outcome in MABTs for BN and BED appear promising but use of more sophisticated statistical analyses and adequate replication are necessary.

Keywords: Bulimia Nervosa, Binge Eating Disorder, Acceptance-Based Therapies, Mindfulness, Eating Disorders

Treatments for Bulimia Nervosa and Binge Eating Disorder

Binge eating, defined as eating an objectively large amount of food within a discrete time-period while experiencing a sense of loss of control over eating, is a key feature of binge-eating disorder (BED) and bulimia nervosa (BN). BN also involves inappropriate compensatory behaviors (e.g., self-induced vomiting, compensatory exercise) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The current psychological treatment for BN and BED with the most empirical support is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; Fairburn, Wilson, & Schleimer, 1993) including the recently enhanced version, CBT-E (Fairburn & Beglin, 2008). Recent meta-analyses have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT in reducing behavioral and cognitive symptoms of eating disorders (EDs) relative to alternative psychological treatments (Linardon, Wade, de la Piedad Garcia, & Brennan, 2017; Peat et al., 2017).

Despite clinically significant improvements following CBT for many individuals with BN and BED, approximately 50% of patients still remain symptomatic at post-treatment (Brownley et al., 2016; Linardon, Wade, et al., 2017; Södersten, Bergh, Leon, Brodin, & Zandian, 2017). Further, rates of relapse following CBT appear to often match rates of remission occurring between post-treatment and follow-up in RCTs, giving the false impression that no relapse occurs when reported statistically (Södersten et al., 2017). When examined more closely, however, relapse rates following CBT for EDs are greater than 30% (Södersten et al., 2017). Multiple studies have also found approximately 25% of participants enrolled in clinical trials of CBT for BN and/or BED discontinue treatment prematurely (Agüera et al., 2017; Grilo, Masheb, Wilson, Gueorguieva, & White, 2011; J. R. Shapiro et al., 2007). Such findings suggest significant room for improvement in treatment acceptability and outcome for BN and BED.

Mindfulness- and Acceptance-Based Treatments for BN and BED

Mindfulness- and acceptance-based treatments (MABTs) have emerged within the past two decades for a variety of psychological disorders (Haynos, Forman, Butryn, & Lillis, 2016; Kahl, Winter, & Schweiger, 2012; Öst, 2008). MABTs are based on theoretical models targeting therapeutic change through psychological processes such as acceptance, mindfulness, psychological flexibility, cognitive defusion/distancing, and emotion regulation. Relative to traditional CBT theories which attribute psychopathology to maladaptive thought patterns and directly target their content and validity, MABTs posit that psychopathology is maintained through avoidance or problematic attempts to control distressing or undesired internal experiences and thus, target increases in psychological flexibility and acceptance (Forman et al., 2012; Hofmann & Asmundson, 2008).

MABTs tested for BN and BED include the following therapeutic approaches: acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction (Haynos et al., 2016). A brief description of the specific theoretical models underlying each MABT are presented in Table 1. Though research on these interventions to treat BN and BED is nascent, preliminary evidence suggests such treatments may be efficacious for this population (Godfrey, Gallo, & Afari, 2015; Katterman, Kleinman, Hood, Nackers, & Corsica, 2014; Linardon, Fairburn, Fitzsimmons-Craft, Wilfley, & Brennan, 2017).

Table 1.

Brief Description of Theories Underlying MABTs

| MABT | Description of Underlying Model and Treatment Targets |

|---|---|

| 1. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) | ACT theorists posit that a primary source of psychopathology and human suffering is psychological inflexibility (i.e. patterns of behavior rigidly guided by internal experiences, rather than by one’s personal values or direct contingencies; Luoma, Hayes, & Walser, 2007). ACT-based treatments therefore seek to increase one’s level of psychological flexibility, or one’s ability to fully and nonjudgmentally contact the present moment and, based on what the situation affords, change or persist in behaviors in the service of one’s chosen values (Hayes et al., 2006). Clinicians seek to increase this flexibility through six core psychological processes; acceptance, defusion, contact with the present moment; self-as-context; values clarification; and committed action (Hayes et al., 2006). |

| 2. Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) | The DBT model theorizes that problematic interpersonal styles and deficits in emotion regulation interact with personal and environmental factors in ways that facilitate and/or reinforce maladaptive behaviors (Feigenbaum, 2007). Therefore, the primary target within DBT-based interventions is an increase in emotion regulation skills (Telch et al., 2001). This is done through several psychological processes, often presented to clients in ‘modules’ including mindfulness skills, distress tolerance skills, and interpersonal efficacy skills (Feigenbaum, 2007). |

| 3. Mindfulness Based Interventions (MBIs) | MBIs seek to cultivate mindfulness skills and facilitate their use in individuals’ day-to-day lives. These interventions posit that by intentionally shifting one’s attention with openness and jon-judgementalness elicits decreases in psychological distress and facilitates increases in quality of life (S. L. Shapiro et al., 2006). Different interventions utilize one or more of a variety of mindfulness skills (i.e. meditation, body scans, grounding exercises) to cultivate this shift. |

Relevance of Mechanisms of Action and Moderators within MABTs

Most studies evaluating MABTs for BN and BED consist of small, uncontrolled pilot trials or clinical trials comparing the MABT to a non-CBT control condition (e.g., supportive psychotherapy, treatment-as-usual (TAU), waitlist). Additionally, much of the research evaluating these treatments to date, both for EDs and for varying forms of psychopathology broadly, is based on widely varied implementations (e.g. length/number of sessions; frequency of sessions; group vs. individual). These limitations minimize our ability as a field to draw firm conclusions on if, and in what form, MABTs appear to be most efficacious. Thus, more robust clinical trials that compare manualized versions of MABTs to CBT are sorely needed. However, just as necessary is implementation of alternative experimental designs and statistical analyses increasing our knowledge of how and for whom specific treatments work (Brauhardt, de Zwaan, & Hilbert, 2014; Murphy, Cooper, Hollon, & Fairburn, 2009).

While behavioral outcomes following MABTs for EDs appear to be comparable to CBT (Linardon, Fairburn, et al., 2017), several differences related to theory and technique are important to consider. MABTs emphasize skills and techniques facilitating increased acceptance of internal experiences (i.e. thoughts, feelings, physical sensations), contrasted with traditional cognitive-behavioral approaches which emphasize modifying the content of dysfunctional cognitions to make them more adaptive (Hayes, Villatte, Levin, & Hildebrandt, 2011; Stotts & Northrup, 2015). While a full outline of MABTs’ proposed mechanisms of action (i.e. the steps or processes through which therapy works to produce change) is beyond the scope of this paper, several previous reviews exist (e.g. Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006; Lynch, Chapman, Rosenthal, Kuo, & Linehan, 2006; S. L. Shapiro, Carlson, Astin, & Freedman, 2006).

Identification of mechanisms of action is crucial for enhancing the efficiency of treatment development and dissemination. A helpful first step is to examine mediators of treatment outcome (i.e. a construct showing important statistical relations between an intervention and an outcome, but may not explain the precise process through which the change comes about; Kazdin, 2007). Such research will: 1) clarify which treatment components should be prioritized and which could be reduced or eliminated, and 2) support development of innovative treatments that focus on promoting change through targeted mechanisms (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002). Despite calls for more research in this regard, (Murphy et al., 2009), few studies have evaluated the specific processes through which patient change occurs within ED treatment research (Brauhardt et al., 2014; Vall & Wade, 2015).

Additionally, discovering for whom treatments are effective using pre-treatment characteristics or conditions that differentiate more or less successful patients will provide data for facilitating treatment matching. Such characteristics might predict treatment outcome across individuals, regardless of treatment condition (i.e. non-specific predictors) or differentially across two or more treatments (as a moderator). Considering the comparable behavioral outcomes observed between MABTs and CBT for eating disorders to date (Linardon, Fairburn, et al., 2017), this knowledge may be particularly helpful in determining which approach may be more efficacious on an individual patient basis. Researchers can also use this knowledge to better maximize power when stratifying patients in randomized clinical trials (Kraemer et al., 2002).

Review Aims

The purpose of the current review is to systematically examine the literature on MABT outcome studies for BN and BED to: 1) determine how many studies have assessed mechanisms of action and moderators of treatment outcome, 2) identify which mechanisms and moderators (if any) emerge, 3) describe if significant mechanisms of action reported are consistent with MABTs’ putative mechanisms, and 4) make recommendations for treatment research investigating MABTs for BN and BED.

METHODS

Study Selection

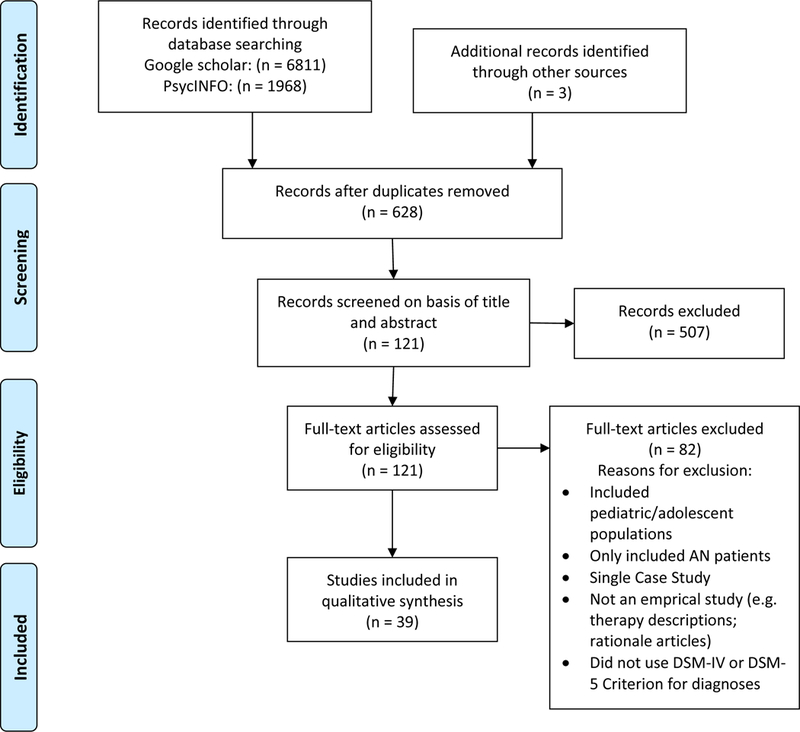

We conducted a systematic review of relevant treatment literature following PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009) (Figure 1). We utilized Google Scholar and PsycINFO electronic databases to conduct an independent search for all relevant English language, peer-reviewed publications dated through July 2018.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram

We systematically entered MABT-related search terms into each electronic database in conjunction with terms related to ED behaviors or diagnoses (e.g., “acceptance” and “binge*”). ACT terms included ‘acceptance’, ‘acceptance-based therapy’, ‘acceptance and commitment therapy’, and ‘acceptance-based intervention’. DBT terms included ‘dialectical behavior therapy’, and ‘DBT’. MBI terms included ‘mindfulness’, ‘meditation’, ‘mindfulness-based intervention’, ‘mindfulness-based therapy’,’ and ‘mindful eating’. ED terms included binge*, binge eat*, binge eating disorder*, bulimi*, bulimia nervosa, eating disorder*, and eating pathology. We also searched the reference sections of all articles meeting inclusion criteria from the online database search and articles cited by systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

The first author conducted an initial search of each database for eligible articles within each specified treatment category. A second search was then conducted individually by a subsequent author for one of the subgroups of therapy defined (ACT: SMM; DBT & MBIs: HBM). Studies identified for possible inclusion underwent a full review by both the first author and corresponding author conducting the relevant initial search based on the inclusion criteria outlined below. Any disagreement on articles between the two initial reviewing authors was opened to a full discussion with remaining authors to determine whether they met criteria for final inclusion.

Study Eligibility Criteria

To be eligible for inclusion, studies must have: 1) tested at least one MABT to treat BN or BED; 2) used an empirical design 3) included more than one participant diagnosed with BN, BED based on DSM-IV or DSM-5 criterion, or had clinically significant but subthreshold BN or BED eating pathology [i.e., individuals who do not meet DSM-IV or DSM-5 thresholds for BN or BED diagnosis due to binge eating/purging less than two times per week or only experiencing binges classified as subjective binge episodes (Fairburn et al., 1993), but who are engaging in these behaviors at least once in the past 28 days]; and 4) utilized only an adult sample. Due to the small number of RCTs conducted with ED treatments to date and the potential for alternative empirical designs to provide initial insight into mechanisms of action and moderators to examine in future research (Collins, Kugler, & Gwadz, 2016), we included non-randomized controlled trials and additional studies utilizing pre-post designs. Considering this broad inclusion criteria, we did not formally code studies based on design quality and all conclusions were based on qualitative synthesis of study results. However, limitations posed by differing study designs and risk of bias were considered in reference to the Cochrane handbook (Higgins & Green, 2008) and are discussed where relevant throughout the review.

Data Extraction

In total, 39 publications met all inclusion criteria (Table 2). All data were initially extracted by the first author and then confirmed for accuracy by therapy sub-group by the same author who conducted the related secondary literature search. Information extracted from studies included: study design; treatment type; sample characteristics (N, gender, ED diagnoses); process-relevant variables examined (theoretically relevant mechanisms of action/treatment targets, mediating variables and/or moderating variables); and reported findings relevant to these variables. Studies were grouped based on the theory most consistently related to the MABT being examined. “ACT-Based Interventions” included studies using a complete ACT protocol or examining alternative treatments supplemented with an acceptance-based component consistent with ACT theory. “DBT-Based Interventions” included studies using a complete DBT protocol, studies only using certain components of full DBT (e.g. skills groups) as the sole intervention, and studies examining alternative treatments supplemented with a DBT component. Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBIs) included studies using complete protocols in which mindfulness or meditation were the primary emphasis or studies examining an alternative treatment supplemented with an additional mindfulness component.

Table 2.

Mechanisms of Action in MABTs for BN and BED

| Publication | ED Sample (Diagnostic Criteria) |

Study Design | MABT (n) | Comparison Condition(s) (n) |

Intervention Delivery/ Length |

Process Variable(s) Assessed |

Summary of Relevant Findings |

Mediation Analysis Category |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT Based Interventions | |||||||||

| 1 | Hill et al. (2015) | BED (DSM-5) | Case-Series | ACT (2) | N/A | Individual/10 weekly sessions | Body-Image Specific Psychological

Flexibility; General Psychological Flexibility |

↑ Body Image Flexibility & General Cog. Flexibility for both pts paralleled ↓ binge eating (no formal analyses conducted) | “Proxy” Mediation |

| 2 | Juarascio et al. (2013a) | AN, BN, & EDNOS (DSM-IV) | NE/NR-G | Residential TAU w/ ACT (66) | TAU (74) | Biweekly ACT group supplementing residential TAU/Varied | Cognitive Acceptance; Affective Acceptance; Willingness; Cognitive Defusion; Psychological Acceptance; Emotion Regulation; Willingness to consume a “forbidden” food; Dysfunctional Thinking |

Significant improvement on all process

variables observed at EoT within both groups. Willingness significantly mediated effects of treatment condition on EDE-Q global scores pathology/behavior (↑ Willingness predicted ↓ EDE-Q global scores, and willingness trended toward greater improvements in the ACT condition). No other variables showed mediation effects |

Formal Mediation & “Proxy” Mediation |

| 3 | Juarascio et al. (2013b) | AN, BN, & EDNOS (DSM-IV) | NE/NR-G | Residential TAU w/ ACT (66) | TAU (74) | Biweekly ACT group supplementing residential TAU/Varied | None (Only examined moderators) | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 4 | Juarascio et al. (2015) | AN, BN, & EDNOS (DSM-IV) | NE/NR-G (Analyses of Treatment Completers Only) | Residential TAU w/ ACT (52) | TAU (53) | Biweekly ACT group supplementing residential TAU/Varied | Emotion Regulation; Cognitive Defusion; Psychological Flexibility |

↑ Cognitive Defusion Ability and ↑ access to effective emotion regulation strategies were both significantly correlated with ↑ ED-related Quality of Life at EoT (across all participants). | “Proxy” Mediation |

| 5 | Juarascio et al. (2017) | BED (DSM-5) | Open Trial | ABBT (19) | N/A | Group/10 weekly sessions |

Emotion Regulation; Non-acceptance of Emotions; Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behavior; Impulse Control; Emotional Awareness; Access to Emotional Regulation Strategies; Emotional Clarity; General Acceptance of Internal Experiences; Food-Specific Acceptance of Internal Experiences; Negative Urgency |

Significant improvement was observed on all process variables except difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, emotional awareness, and emotional clarity. ↓ EDE Global Scores were significantly related to ↓ Non-acceptance of emotions, ↑ access to emotion regulation strategies, ↑ acceptance of both general and food-specific internal experiences. ↓ EDE Global Scores were also significantly related to ↓ emotional clarity and ↓ emotional awareness, contradictory to study hypotheses. |

“Proxy” Mediation |

| 6 | Manasse et al. (2016) | BED (DSM-5) | Open Trial | ABGT (17) | N/A | Group/10 weekly sessions | None (Only examined moderators) | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 7 | Strandskov et al. (2017) | BN & EDNOS (DSM-IV) | RCT | ACT-Influenced CBT | WLC | Internet Based with Clinician Support/8 weeks | None | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| DBT-Based Interventions | |||||||||

| 8 | Ben-Porath, Wisniewski, & Warren (2009) | AN, BN, EDNOS (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | DBT-Informed PHP (40) | N/A | Biweekly DBT Skills Group w/ Additional weekly groups consisting of DBT-informed concepts/Varied | General Emotion Regulation

Ability; Ability to Regulate Emotions via Cognitive Strategies; Ability to Regulate Emotions via Behavioral Strategies |

Significant main effect of time on ↑ emotion regulation however, also significant interaction between diagnosis and time such that, at pretreatment, individuals who had a comorbid BPD diagnosis reported significantly ↓ emotion regulation than individuals without a comorbid BPD diagnosis, however at end of treatment there was no difference between groups. (Whether changes were significant within each group was not reported) | Pre-Post Only |

| 9 | Ben-Proath, Federici, Wisniewski, & Warren (2014) | AN & BN (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | PHP-TAU w/ DBT Skills Training (65) | N/A | CBT focused PHP with 2 hours of DBT Skills Training Group each week/Varied | Non-acceptance of

emotions; Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behavior; Impulse Control; Emotional Awareness; Access to Emotional Regulation Strategies; Emotional Clarity |

Significant ↑ with small to medium effect sizes in all emotion regulation skills except clarity of emotions (no change). Significant ↑ with small effect size on overall emotion regulation abilities. | Pre-Post Only |

| 10 | Chen (Hepworth, 2010) et al. (2008) | BN & BED, must have comorbid BPD (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | DBT (8) | N/A | Weekly DBT Skills Group; Weekly Individual Psychotherapy; access to 24-hour phone coaching/24 weeks | None | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 11 | Chen et al. (2017) | BN & BED (DSM-5) | A-RCT (Staged Randomization) | DBT (36) | CBTgsh (42) CBT+ (31) |

Stage 1: All participants received CBTgsh

manual and 4 weekly 20–30 min support sessions. Stage 2: “Early Strong Responders” assigned to continue CBTgsh (i.e. continued CBTgsh for up to 24 weeks). “Early Weak Responders” randomized to 6 months of weekly group and individual DBT with 24-hour access to phone coaching or 6 months of weekly group and individual CBT with 24-hour access to psychiatry resident on-call. |

None | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 12 | Courbasson, Nishikawa, & Dixon (2012) | AN, BN, & BED, must have comorbid SUD (DSM-IV) | M-RCT | DBT (13) | TAU (8) | Weekly group therapy & individual therapy as deemed necessary (TAU) or weekly skills-training group and weekly individual psychotherapy w/ access to 24 hour phone coaching (DBT) /1 year |

General Emotion Regulation Ability; Ability to Regulate Emotions via Cognitive Strategies; Ability to Regulate Emotions via Behavioral Strategies Urges to Eat in Response to Emotions; Drive for Thinness; Body Dissatisfaction; Ineffectiveness; Perfectionism; Interpersonal Distrust; Interoceptive Awareness |

Analyses were only possible for DBT condition due to high attrition in TAU. At EoT: Large time effect observed for improvements in general emotion regulation ability and moderate time effect observed for improvements in interoceptive awareness and ability to regulate emotions via behavioral strategies. Increased emotion regulation abilities were associated with ↑ perceived efficacy to resist substances and ↓ emotional eating, but not ↓ substance use & severity or binge eating frequency. At 3-mo. Follow Up: Large time effect observed (from baseline to follow up) for improvements in interoceptive awareness, general, and behavioral emotion regulation abilities. Moderate time effect observed for improvements in drive for thinness and perceived ineffectiveness. At 6-mo. Follow Up: Large time effect observed (from baseline to follow up) for improvements in interoceptive awareness, general and cognitive emotion regulation abilities. Moderate effect sizes observed for improvements in drive for thinness and behavioral emotion regulation abilities. |

Pre-Post & “Proxy” Mediation |

| 13 | Erb, Farmer, & Mehlenbeck (2013) | Full or Subthreshold BED (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | Condensed DBT (6) | N/A | Weekly DBT Skills Group/12 Weeks | Urges to Eat in Response to Emotions | ↓ Urges to eat in response to emotions observed in treatment completers (n=3). Changes were clinically significant in 2 out of 3 treatment completers. | Pre-Post Only |

| 14 | Hill, Craighead, Safer (2011) | Full or Subthreshold BN (DSM-IV) | RCT | Appetite Focused DBT (18) | 6 Week DTC (14) | Weekly individual sessions/12 Weeks | Emotion Regulation; Urge to Eat in Response to Emotions; Interoceptive Awareness; Emotional Awareness; ED Specific Cognitions |

Significant improvement on all process variables observed within ITT sample. At 6 weeks, treatment group reported significantly ↓ ED Specific cognitions and significantly ↑ Interoceptive Awareness relative to control group, but did not significantly differ on any other process variables. | Pre-Post Only |

| 15 | Kidd (2017) | BED (DSM-5) | Open Trial | Group DBT (6) | N/A | Weekly DBT Skills Group/18 Sessions | None | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 16 | Klein, Skinner, Hawley (2012) | Full or Subthreshold BN & Full or Subthreshold BED (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | Adapted DBT (5) | N/A | Weekly DBT Skills Group/16 Sessions | Interoceptive Awareness; Drive for Thinness; Ineffectiveness; Perfectionism; Body Dissatisfaction; Interpersonal Distrust |

Parametric and Non-Parametric tests found significant improvement for Ineffectiveness and Interoceptive Awareness at EoT. However, improvements in Perfectionism and Interpersonal Distrust were only significant in Parametric, but not in Non-Parametric analyses. | Pre-Post Only |

| 17 | Klein, Skinner, Hawley (2013) | Full or Subthreshold BN & Full or Subthreshold BED (DSM-IV) | RCT | Group DBT (22) | Individual self-monitoring (DBT diary cards) supported by brief individual sessions (14) | Weekly Individual or Group (dependent on treatment condition)/15 Sessions | Interoceptive Awareness; Drive for Thinness; Ineffectiveness; Perfectionism; Body Dissatisfaction; ED Specific Cognitions |

Significant improvement in Interoceptive Awareness for both groups, but significant improvements in Ineffectiveness, Drive for Thinness, Body Dissatisfaction, Perfectionism, and ED Specific Cognitions observed in Group DBT only. | Pre-Post Only |

| 18 | Kroger et al. (2010) | AN & BN, must have comorbid BPD & previously failed to respond to ED inpatient treatment (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | Inpatient DBT with added CBT-E module (24) | N/A | Inpatient setting with 3 weekly DBT Skils groups & 1 weekly individual session/3 months | None | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 19 | Masson et al. (2013) | BED (DSM-IV) | RCT | DBTgsh (30) | WLC (30) | Guided self-help including in person orientation to manual and 6 bi-weekly support phone calls/13 Weeks | Emotion Regulation | DBTgsh reported significant improvement in Emotion Regulation at EoT and 6-month follow up compared to baseline. At EoT, DBTgsh group’s Emotion Regulation scores were significantly ↑ (better) than WLC. | Pre-Post Only |

| 20 | Navarro-Haro et al. (2018) | AN, BN, & EDNOS, must have comorbid BPD (DSM-IV) | NE/NR-G | DBT (71) | CBT (47) | Weekly individual and group sessions/24 Sessions | Emotion Regulation through Cognitive

Reappraisal; Emotion Regulation through Expressive Suppression |

Improvements in both groups were not statistically significant; however, improvement in emotion regulation through reappraisal was significantly greater in the DBT group compared to CBT. | Pre-Post Only |

| 21 | Rahmani, Omidi, Asemi, & Akbari (2018) | BED, must have Obese or Overweight BMI (DSM-IV) | RCT | DBT (30) | WLC (30) | Twice weekly DBT skills group/10 weeks | Emotion Regulation | Significant improvement in emotion regulation skills observed within DBT group from pre to post treatment. Emotion regulation skills were significantly greater than those reported by WLC at EoT. | Pre-Post Only |

| 22 | Robinson & Safer (2012) | BED (DSM-IV) | RCT | DBT-BED (50) | ACGT (non-directive Rogerian Based treatment) (51) | Weekly group/20 Sessions | None (Only examined moderators) | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 23 | Safer & Joyce (2011) | BED (DSM-IV) | RCT | DBT-BED (50) | ACGT (non-directive Rogerian Based treatment) (51) | Weekly group/20 Sessions | None (Only examined moderators) | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 24 | Safer et al. (2002) | BED (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | DBT (32) | N/A | Weekly DBT Skills Group/20 Sessions | None (Only examined moderators) | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 25 | Safer, Robinson, & Jo (2010) | BED (DSM-IV) | RCT | DBT-BED (50) | ACGT (non-directive Rogerian Based treatment) (51) | Weekly group/20 Sessions | Emotion Regulation; Urges to eat in Response to Emotions |

Small effect sizes favoring DBT-BED over ACGT observed for Urges to eat in Response to Emotions at EoT. At 12-month follow up, small effect sizes favoring ACGT over DBT-BED were observed for emotion regulation. | Pre-Post Only |

| 26 | Safer, Telch, & Agras (2001) | Full or Subthreshold BN (DSM-IV) | RCT | DBT (14) | WLC (15) | Weekly individual psychotherapy/20 Sessions | Emotion Regulation; Urges to eat in Response to Emotions |

Medium effect size of time observed for both process variables at EoT, however no significant group differences were observed. | Pre-Post Only |

| 27 | Telch, Agras, Linehan (2000) | BED (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | DBT (11) | N/A | Weekly group/20 Sessions | Emotion Regulation; Urges to eat in Response to Emotions |

Significant ↓ in Urges to eat in response to emotions and significant ↑ in emotion regulation observed at EoT. | Pre-Post Only |

| 28 | Telch, Agras, Linehan (2001) | BED (DSM-IV) | RCT | DBT (22) | WLC (22) | Weekly group/20 Sessions | Emotion Regulation; Urges to eat in Response to Emotions |

No significant changes were observed on process variables. | Pre-Post Only |

| 29 | Wallace, Masson, Safer, von Ranson (2014) | BED (DSM-IV) | RCT (secondary analyses only) | DBTgsh (60) | N/A (WLC in initial RCT) | Guided self-help including in person orientation to manual and 6 support phone calls approx. every 2 weeks/13 weeks | Emotion Regulation | Improvement in Emotion regulation predicted

binge abstinence at EoT and at 4-, 5-, and 6-month follow

up. Odds ratios indicated that for every one-unit increase in Emotion Regulation change scores at EoT, there was an approx. 4–6% increase in the odds of being binge abstinent at EoT and each follow up point. Individuals who were binge abstinent at EoT reported significantly greater improvement in Emotion Regulation at EoT as compared to individuals who were not binge abstinent. The same pattern was observed at each follow up. |

“Proxy” Mediation |

| Mindfulness-Based Interventions | |||||||||

| 30 | Azari, Fata, & Poursharifi (2013) | BED (DSM-IV) | RCT | MBCT (14) | CBT (14) WLC (14) |

Weekly group/8 weeks | None | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 31 | Baer, Fischer, & Huss (2005) | Full or Subthreshold BED (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | MBCT (6) | N/A | Weekly group/10 Sessions | Observing Skills; Nonjudgmental Acceptance; Belief that eating helps manage negative affect; Belief that eating leads to feeling out of control; Belief that eating alleviates boredom |

Statistical significance could not be

determined due to small sample size, however beliefs that eating

alleviates negative affect decreased across participants (but was still

above normal range). Decrease was also observed across participants in

belief that eating leads to feeling out of control. Belief that eating

alleviates boredom increased slightly. Moderate increases observed in observing skills and a substantial increase observed in nonjudgmental acceptance of internal experiences. Both scores at EoT were still above means reported by nonclinical samples. |

Pre-Post Only |

| 32 | Courbasson, Nishikawa, & Shapira (2010) | BED, must have comorbid SUD (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | MACBT (38) | N/A | Weekly group/16 Sessions | None | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 33 | Duarte, Pinto-Gouveia, & Stubbs (2017) | BED (DSM-IV) | RCT |

CARE (Low-intensity intervention focused on compassion, mindfulness, and acceptance developed for trial) (11) |

WLC (9) | Guided at home practice/4 weeks | Cognitive Fusion with Undesired Thoughts about

Food Cravings; Body Image Shame; Body-Image Specific Psychological Flexibility; Trait Mindfulness; Self-Compassion; Compassion toward Others; Sense of Personal Inadequacy; Self-Hatred in Response to Setbacks; Self-Reassurance in Response to Setbacks |

Significant improvement in cognitive fusion

with undesired thoughts about food cravings, compassion toward others,

body-image specific psychological flexibility, trait mindfulness, and

sense of personal inadequacy were observed at EoT, and self-compassion

trended toward significance (p=.054). Compared to WLC,

the treatment group reported a significantly larger ↓ in body

image shame and self-hatred in response to setbacks and significantly

larger ↑ in self-reassurance in response to

setbacks. Effects were maintained at 1-month follow up for cognitive fusion with food cravings, body-image specific psychological flexibility, self-compassion, and compassion toward others. |

Pre-Post Only |

| 34 | Hepworth (2011) | AN, BN, & BED (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | Mindful Eating Group w/ long-term CBT (33) | N/A | Weekly Group/10 weeks | None | N/A | No Process Measures Assessed |

| 35 | Kristeller & Hallet (1999) | BED (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | Meditation-Based Group Treatment (18) | N/A | Weekly group/6 weeks | Sense of control while eating; Sense of mindfulness while eating; Interoceptive Awareness |

Significant ↑ on all process variables

at EoT. ↑ in perceived sense of control while eating, sense of mindfulness while eating and awareness of satiety (but not hunger) were all associated with ↓ number of binges at EoT. |

“Proxy” Mediation |

| 36 | Kristeller, Wolever, & Sheets (2014) | Full or Sub-threshold BED (DSM-IV) | RCT | MB-EAT (53) | PECB (50) WLC (47) |

9 weekly groups followed by 3 monthly “booster” sessions/approx. 4.5 months | Frequency of Meditation

Practice; Awareness of Internal Experiences; Disinhibition; Cognitive Restraint; Sense of control over eating behaviors |

In both treatment conditions, significant

↑ were observed on sense of control over eating, awareness of

internal experiences, and cognitive restraint. Significant ↓ in

disinhibition observed within both groups. All effect sizes were larger

in MB-EAT group than PECB group. In MB-EAT group only, ↑ time spent meditating was significantly associated with greater ↓ in binge eating and disinhibition. |

“Proxy” Mediation |

| 37 | Pinto-Gouveia et al. (2016) | BED, must have Obese or Overweight BMI (DSM-IV) | RCT (but only analyses of treatment condition reported) | BEfree (combined psychoeducation, compassion, and mindfulness-focused intervention) (31) | N/A (WLC in initial RCT) | Weekly group/12 sessions | Psychological Flexibility; Body Image Specific Cognitive Fusion; Engagement in Values-Driven Behavior; External Shame; Self-Criticism; Self-Compassion; Observing Skills; Describing skills; Acting with Awareness skills; Non-Judgmental Action skills; Non-Reactivity to Internal Experience skills |

Significant improvement observed on all

process variables at EoT except observing skills and describing skills.

All post-treatment therapeutic gains were maintained 3- and 6- month

follow-up. Psychological flexibility, body image cognitive fusion, and engagement in values-driven behavior all significantly mediated the effect of intervention on binge eating frequency (in hypothesized directions). Changes in external shame, self-compassion, and self-criticism mediated decreases in binge eating (in hypothesized directions). Only psychological flexibility and non-reactivity of internal experience skills significantly mediated decreases in global eating psychopathology. |

Formal Mediation |

| 38 | Pinto-Gouveia et al. (2017) | BED, must have Obese or Overweight BMI (DSM-IV) | RCT | BEfree (combined psychoeducation, compassion, and mindfulness-focused intervention) (19) | WLC (17) | Weekly group/12 sessions | Body-Image Specific Psychological

Flexibility; Body Image Specific Cognitive Fusion; Engagement in Values-Driven Behavior; Self-Criticism; External Shame |

Significant medium to large effect of

intervention observed on external shame, body-image specific

psychological flexibility, body-image specific cognitive fusion, and

self-criticism (all in hypothesized direction).. Results suggest that improvements in body-image specific psychological flexibility, body-image specific cognitive fusion, external shame, and self-criticism were maintained at 3- and 6- month follow-ups. |

|

| 39 | Woolhouse et al. (2012) | AN, BN, & BED (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | MMEG (intervention combining mindfulness & CBT components) (30) | N/A | Weekly group/10 sessions | Perceived control over

eating; Overeating in response to emotions; Mindfulness |

Significant improvements were observed on all

process variables at EoT. Qualitative analyses of participant feedback indicate that participants perceived “spending more time in the present moment” to have significantly improved their well-being. Participants also perceived treatment to have provided a “shift from avoidance to awareness of emotions”. |

Pre-Post Only |

NE/NR-G = Non-Equivalent, Non-Random Groups; RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial; M-RCT = Matched Randomized Controlled Trial

BED = Binge Eating Disorder; AN = Anorexia Nervosa; EDNOS = Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified BN = Bulimia Nervosa; BPD = Borderline Personality Disorder; SUD = Substance Use Disorder; BMI = Body Mass Index

ACT = Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; ABBT = Acceptance Based Behavioral Treatment; ABGT = Acceptance Based Group Treatment; DBT = Dialectical Behavioral Therapy; DBTgsh = Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Guided Self Help; MBCT = Mindfulness Based Cognitive therapy; MACBT = Mindfulness-Action Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; MB-EAT = Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training; MMEG = Mindfulness Moderate Eating Group

CBT = Cognitive behavioral Therapy; TAU = Treatment as Usual; PHP = Partial Hospitalization Program; WLC = Waitlist Control; CBTgsh = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Guided Self Help; ACGT = Active Comparison Control Group; PECB = Psychoeducational Cognitive Behavioral Treatment

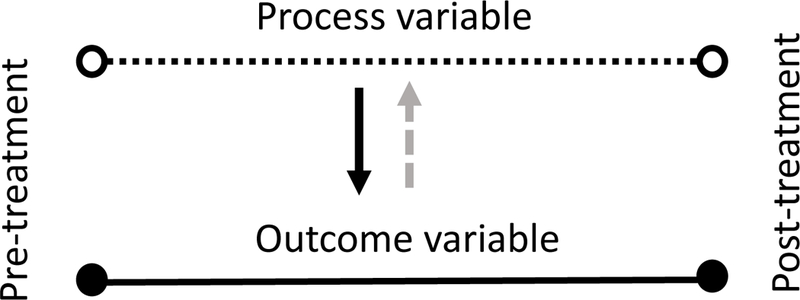

Examination of mediating variables was qualified based on analysis approach using the following categories: 1) did not examine any relevant process variables (n=12), 2) used pre-post change analyses only (n=20), 3) used “proxy”-mediation analyses [e.g., examined the relationship between changes in process measure and ED symptoms through analyses such as Pearson correlations or regression, but no temporal precedence can be determined] (n=5), 4) used formal mediation analyses (n=2), or 5) used ideal mediation analyses (non e). Figures 2–5 (Supplemental Information) provide additional detail. Additionally, any manuscript examining a moderator of treatment outcome is listed in Table 3 along with relevant outcomes.

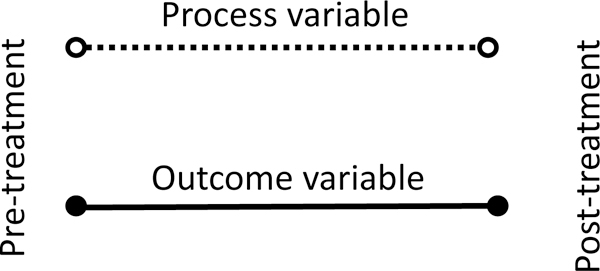

Figure 2. Pre-Post Change.

In pre-post change, changes in process measures and outcome measures from pre to post-treatment are examined in isolation. While improvements in process measures are in important first step, it is inappropriate to infer any relation with outcome.

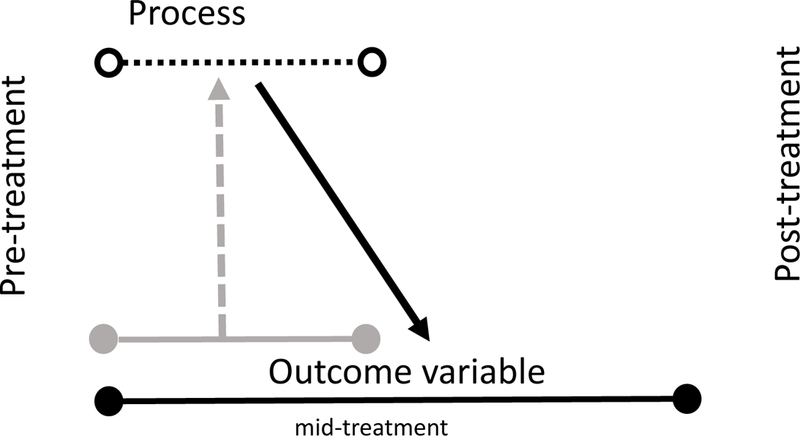

Figure 5. Mediation (Ideal).

In ideal mediation, change in process measures from pre- to mid-treatment are used to predict subsequent change in the outcome variable from mid to post-treatment. This design allows for more confidence that change in a process variable produced a subsequent change in the outcome variable (true mediation).

Table 3.

Moderators of Third-Wave Treatments for BN and BED

| Publication | ED Sample (Diagnostic Criteria) |

Study Design |

MABT used (n) |

Comparison Condition(s) (n) |

Intervention Delivery/Length |

Moderators Assessed | Summary of Relevant Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT Based Interventions | ||||||||

| 1 | Juarascio et al. (2013b) | AN, BN, & EDNOS (DSM-IV) | NE/NR-G | Residential TAU + ACT (66) | TAU (74) | Biweekly ACT group supplementing residential TAU/Varied | Severity of ED Symptoms; Prior Hospitalization related to ED |

↑ Baseline ED severity predicted worse

treatment outcomes across groups. Condition x ED severity interaction

trended toward significance suggesting that individuals with ↑ ED

severity did better following TAU+ACT

(p=.09). Individuals who reported prior hospitalization(s) trended toward larger improvements in the ACT+TAU condition (p=.09) |

| 2 | Manasse et al. (2016) | BED (DSM-5) | Open Trial | ABGT (17) | N/A | Group/10 weekly sessions | Negative Urgency; Delay Discounting; Inhibition; Inhibitory Control |

↑ Baseline negative urgency predicted

more gradual ↓ in binge frequency during & after

treatment. ↑ Baseline negative urgency also predicted less reduction in global ED pathology and ↑ difficulty sustaining symptom improvement relative to individuals with ↓ baseline negative urgency. |

| DBT Based Interventions | ||||||||

| 3 | Ben-Porath, Wisniewski, & Warren (2009) | AN, BN, EDNOS (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | DBT-Informed PHP (40) | N/A | Biweekly DBT Skills Group w/ Additional weekly groups consisting of DBT-informed concepts/Varied | Comorbid BPD diagnosis | Individuals with comorbid BPD diagnosis appeared to benefit more in regard to ↑ emotion regulation skills following treatment. Significant difference was observed in emotion regulation skills between those with or without comorbid BPD at baseline (comorbid BPD group significantly lower), however no group difference observed at EoT. Significance of within group change not reported. |

| 4 | Robinson & Safer (2012) | BED (DSM-IV) | RCT | DBT-BED (50) | ACGT (non-directive Rogerian Based treatment) (51) | Weekly group/20 Sessions |

Age; Sex; Ethnicity; ED psychopathology; Weight/BMI; Onset of ED symptoms; Emotional Eating; General Psychopathology; Emotion Regulation |

Individuals with early onset of overweight BMI

and/or early onset of dieting behaviors (≤ 15 years old) had

significantly larger ↓ in number of binge days at EoT when

assigned to DBT-BED as opposed to ACGT. Individuals who had a comorbid diagnosis of APD had significantly larger ↓ in number of binge days at EoT when assigned to DBT-BED condition as opposed to ACGT. Within DBT-BED group, individuals who had a comorbid diagnosis of APD had significantly ↑ number of binge days at EoT relative to those who did not have comorbid APD. |

| 5 | Safer & Joyce (2011) | BED (DSM-IV) | RCT | DBT-BED (50) | ACGT (non-directive Rogerian Based treatment) (51) | Weekly group/20 Sessions | Rapid Response to Treatment (RR; ≥ 65% reduction in binge eating days by week 4) | RRs reported significantly ↑ binge

abstinence and significantly ↓ eating concern, weight concern,

shape concern, depressive symptoms, disinhibition, and susceptibility to

hunger in both groups at EoT relative to non-RRs. Attrition was significantly ↑ among non-RRs in both groups compared to RRs. Within DBT-BED group, RRs reported significantly ↑ binge abstinence than non-RRs at EoT and 12-month follow up. Within ACGT group, RRs reported ↑ binge abstinence than non-RRs at EoT and 12-month follow up, but difference was not statistically significant at either time point. |

| 6 | Safer et al. (2002) | BED (DSM-IV) | Open Trial | DBT (32) | N/A | Weekly group/20 Sessions | EoT Dietary Restraint; EoT Weight & Shape Concern; EoT Urges to Eat in Response to Emotions; EoT Self-Esteem; Pre-Treatment Early Onset of Binge Eating (<16 years old) |

Analysis of predictors of relapse: Early onset

of binge eating predicted failure to maintain abstinence

↑ EoT Dietary Restraint at EoT predicted relapse at 6 months. |

NE/NR-G = Non-Equivalent, Non-Random Groups; RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial

BED = Binge Eating Disorder; AN = Anorexia Nervosa; EDNOS = Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified BN = Bulimia Nervosa

ACT = Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; ABGT = Acceptance Based Group Treatment; DBT = Dialectical Behavioral Therapy; DBT-BED = Dialectical Behavioral Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder; TAU = Treatment as Usual; PHP = Partial Hospitalization Program; ACGT = Active Comparison Control Group; PECB = Psychoeducational Cognitive Behavioral Treatment

RESULTS

In total, 39 studies were identified that met inclusion criteria (Table 2). Seven studies utilized an ACT-based intervention, 22 studies utilized a DBT-based intervention, and 10 studies utilized a mindfulness-based intervention.

ACT-Based Interventions

Of the seven studies examining either a full ACT protocol or an ACT-based intervention, four utilized a transdiagnostic ED sample, and the remaining three used samples consisting solely of individuals diagnosed with BED. Notably, only one study within this group conducted a fully randomized clinical trial, whereas the others utilized either a non-randomized groups or open trial design. Further, three out of the seven identified publications reported results from the same sample following the same ACT-based intervention. Regarding treatment delivery, one study reported results following an individual, face-to-face ACT protocol; one reported results following an internet-based intervention supported by clinician feedback; the remaining reported following a group-based intervention model. Three studies examining ACT-based interventions did not examine any process variables, and the remaining four conducted “proxy mediation” analyses on hypothesized mechanisms of action (i.e. process variables). One study also conducted formal mediation analyses in addition to “proxy” mediation analyses (Table 2).

The most frequently examined process variable in studies using ACT-based interventions was psychological flexibility (n=4 studies), with two studies also examining problem-specific forms of psychological flexibility (e.g. psychological flexibility in relation to one’s body-image or food-specific internal experiences). All studies utilized either the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II; Bond et al., 2011), the Body-Image Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (BI-AAQ; Sandoz, Wilson, Merwin, & Kellum, 2013), or Food-Specific Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (FAAQ; Juarascio, Forman, Timko, Butryn, & Goodwin, 2011) to assess these constructs. Additionally, one study assessed general levels of willingness, a theoretical mechanism of action related to psychological flexibility that assesses one’s willingness to experience distressing emotions while engaging in valued living, using the Brief Symptom Questionnaire (BSQ; Forman et al., 2012). Overall, findings across all studies indicated that both general and problem-specific forms of psychological flexibility increased following ACT-based treatment. Additionally, trends across two studies suggested that improvements in both general and psychological flexibility were associated with decreases in global eating pathology (Juarascio et al., 2017) or reported binge frequency (M. L. Hill, Masuda, Melcher, Morgan, & Twohig, 2015). However, each of these two studies contained insufficient sample sizes to conduct formal mediation or significance tests. Juarascio, Shaw, et al. (2013) also observed that willingness to experience distress significantly mediated the effects of treatment condition on global ED pathology within their inpatient sample such that willingness trended toward greater improvements within the ACT-based condition; across conditions, willingness significantly predicted lower global ED pathology scores at end of treatment. However, no other process variables examined in this study significantly mediated outcomes.

Additional process variables assessed within studies implementing ACT-based interventions include: emotion regulation skills (n=2); cognitive defusion (n=2); cognitive acceptance (n=1); affective acceptance (n=1); negative urgency (n=1); and dysfunctional thinking (n=1). All studies observed significant improvements across all process variables. Results of “proxy” mediation analyses indicated that improvements in global ED pathology (assessed by the Eating Disorder Examination or Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; Cooper & Fairburn, 1987; Luce & Crowther, 1999) were significantly related to increases in access to emotion regulation strategies following treatment (Juarascio et al., 2017; Juarascio, Schumacher, Shaw, Forman, & Herbert, 2015). Further, Juarascio et al. (2015) found that increases in cognitive defusion abilities were significantly associated with increases in ED-related quality of life at end of treatment. Importantly, all improvements and significant associations were observed across all participants, regardless of treatment condition (when a control or comparison condition was used), suggesting that these improvements may not be specific to ACT-based processes.

Only two ACT-based intervention studies reported analyses for at least one predictor or moderator of treatment outcome (Table 3). While not statistically significant, Juarascio, Kerrigan, et al. (2013)’s findings trended toward those with more severe ED symptoms at baseline showing greater improvements in ED symptomatology following TAU+ACT compared to TAU only. Manasse et al. (2016) found that elevated levels of negative urgency at baseline were significantly associated with smaller reductions in binge frequency and global ED pathology following a 10-session ACT-based group treatment compared to those with low levels of negative urgency at baseline.

DBT-Based Interventions

Twenty-two studies examining DBT-based treatments for BN and/or BED met our inclusion criteria. Nine of these studies utilized a transdiagnostic ED sample. The remaining studies evaluated their interventions using samples of only full or subthreshold BN (n=2) or BED (n=11). Notably, three studies also required that participants have a comorbid diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD), and one required that participants have a comorbid substance use disorder (SUD). A slight majority of these publications reported results from a study utilizing an RCT design (n=12), while the remainder used either an open trial (n=8) or non-randomized group (n=1) design.

Seven studies using a DBT-based intervention did not examine any process variables (Table 2). Among these seven, three studies did include analyses of at least one moderator of treatment outcome whereas the remaining four only reported ED symptom outcomes. Among the remaining 15 studies within this group, 13 conducted pre-post change analyses, one used both pre-post change and “proxy” mediation analyses, and one used only “proxy” mediation analyses. Three reported only on moderators of treatment outcome (Table 3), and one study reported results for both process variables and moderators.

Eleven DBT studies examined changes in emotion regulation, a core hypothesized mechanism of action in DBT. All but one utilized either one or both of two validated tools to measure emotion regulation: Negative Mood Regulation Scale (NMR; Catanzaro & Mearns, 1990) and Difficulties in Emotion Regulation scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004). Navarro-Haro et al. (2018), however, utilized the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003). Results across studies were widely varied: three studies found no significant pre-post changes in patients’ emotion regulation following the DBT-based treatment (Navarro-Haro et al., 2018; Safer, Robinson, & Jo, 2010; Telch, Agras, & Linehan, 2001), and the remaining nine studies showed variable levels of improvement ranging from small to large effect sizes (when reported). Interestingly, one study (D. M. Hill, Craighead, & Safer, 2011) found significant differences in ED symptoms but not in emotion regulation levels between treatment and delayed-treatment comparison participants when assessed at six weeks; however, when all participants’ outcomes were included after they had completed treatment, significant improvements in emotion regulation were observed.

Six studies examined “urges to eat in response to negative affect” as measured by the Emotional Eating Scale (EES; Arnow, Kenardy, & Agras, 1995). Two studies found no change in EES scores following individual DBT for BED (C. Courbasson, Nishikawa, & Dixon, 2012; Telch et al., 2001) while the other four studies found significant improvement (effect sizes varied from small to large). Several of these studies (n=3) consisted of small sample sizes and reported high attrition rates, further limiting the conclusiveness of observed changes.

Other mechanisms assessed within DBT studies included interoceptive awareness (n=4), perfectionism (n=3), drive for thinness (n=3), perceived personal ineffectiveness (n=3), body dissatisfaction (n=3), interpersonal distrust (n=2), and ED-specific cognitions (n=2). All studies observed significant increases in interoceptive awareness following DBT; however, no associations were evaluated between these increases and additional therapy outcomes such as global ED pathology or quality of life. Among the additionally assessed process variables, results were somewhat inconsistent across studies, but widely suggested that minor, statistically insignificant improvements across most variables occurred following DBT-based treatments.

Three studies examined moderators of DBT-based treatment outcomes for BN and BED. Robinson and Safer (2012) found that individuals with early onset (<15 years old) of overweight status and dieting had significantly fewer binge days when treated with DBT-BED than when treated with the active treatment control. Safer and Joyce (2011)utilized data obtained from the same sample and found that rapid responders (RRs; ≥65% reduction in binge eating days by week 4) in both of their treatment conditions reported significantly higher rates of binge eating abstinence, depression, and eating pathology at end of treatment (Table 3). However, they also noted that while RRs in both conditions reported higher rates of binge eating abstinence at both end of treatment and 12-month follow-up than non-RR participants in the same condition, these differences were only statistically significant within the DBT group. Safer, Lively, Telch, and Agras (2002) found that early onset of binge eating (≤16 years old) and higher levels of dietary restraint at end of treatment significantly predicted relapse at six months among individuals who had successfully achieved abstinence from binge eating following DBT-BED.

Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Ten studies examining MBIs met our inclusion criteria (Table 2). Two used a transdiagnostic ED samples, with participants having a diagnosis of AN, BN, or BED. The remaining eight studies consisted only of individuals diagnosed with full or subthreshold BED. One study using a BED-only sample also required participants to have a comorbid SUD diagnosis. Five studies used an RCT study design, and five used an open trial design.

Among the ten studies implementing MBIs, three did not examine process variables in any way and no studies examined moderators of treatment outcome. Four studies conducted pre-post change analyses of at least one process variable; two conducted mediation “proxy” analyses; one utilized formal mediation analyses (Table 2).

Five studies examined changes in general mindfulness or specific mindfulness skills (e.g., observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-reactivity to internal experiences). Overall, studies examining individuals’ self-reported sense of mindfulness following MBIs (n=3) observed significant improvements; however, findings relevant to specific mindfulness skills varied (see Table 2). Three studies also examined perceived sense of control over eating behaviors, and all reported significant increases at end of treatment. Further, Kristeller and Hallett (1999)found that increases in perceived sense of control over eating and sense of mindfulness while eating were both significantly associated with larger decreases in binge eating frequency following their meditation-based intervention for BED.

Three studies also examined problem-specific cognitive fusion and psychological flexibility. All three studies reported significant improvements for both variables at end of treatment within the MBI condition, however two of the publications were reporting results from the same sample and intervention. Additional process variables assessed included external shame (n=3); interoceptive awareness (n=1), self-compassion (n=2), self-criticism/sense of personal inadequacy (n=3), engagement in values-driven behaviors (n=2), response style to setbacks (n=1), and beliefs about or experiences of over-eating in response to negative affect (n=2). The majority of these studies observed significant increases at end of treatment on all process variables assessed (Table 2).

Kristeller, Wolever, and Sheets (2014) “proxy” mediation analyses indicated that participants who reported greater increases in time spent meditating following their MBI were significantly more likely to reporter larger decreases in binge eating behaviors and disinhibition. Pinto-Gouveia et al. (2016) conducted formal mediation analyses and found that changes in psychological flexibility, body image-specific cognitive fusion, engagement in values-driven behavior, self-compassion, and self-criticism significantly mediated the effect of their MBI on binge frequency, with greater improvements in process variables predicting greater decreases in binge frequency. However, when assessing mediation of global ED pathology, only changes in psychological flexibility and non-reactivity to internal experience skills mediated outcomes. Notably, the majority of the mindfulness skills assessed as mediators in this study were not significant, despite mindfulness being a primary target of their intervention. However, these results should be interpreted with caution as the measurement tool utilized to assess mindfulness skills (the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-15; Baer et al., 2008) had poor internal consistency in this study.

DISCUSSION

To inform the development of more efficient and effective treatments that can be matched to individual patient needs, the current review sought to: 1) determine how many MABT studies for BN and BED have assessed mechanisms of action and moderators of treatment outcome, 2) identify which mechanisms and moderators emerge as significant in extant studies, 3) determine whether emerging mechanisms of action are consistent with putative mechanisms of the corresponding theoretical models, and 4) make recommendations for future treatment research investigating MABTs for BN and BED. Consistent with previous empirical observations, our review demonstrates that very few extant studies report examination of either mechanisms of action or moderators of treatment outcome.

In studies where analyses of hypothesized mechanisms of action were reported, results generally supported theoretically consistent improvements following the MABT being tested. The two ACT-based treatment studies that utilized formal or “proxy” mediation both found that improvement in psychological flexibility is associated with improvement in ED symptoms. Pre-post change analyses in DBT studies supported general improvements in hypothesized mechanisms of action such as emotion regulation skills, impulse control, and acceptance of negative emotion. Similarly, pre-post improvements in hypothesized mechanisms of MBIs, including mindfulness and awareness skills, non-judgmental self-acceptance, and self-efficacy around eating were found across included studies.

Only six studies assessed predictors or moderators of treatment response. This is particularly surprising given that the majority of studies assessed demographic and process variables at baseline, providing the opportunity to evaluate whether these variables predicted treatment outcome either within one treatment (as a non-specific predictor) or differentially across two or more treatments (as a moderator). Further, the few studies that reported on predictors and moderators showed inconsistent responses to treatment and lacked appropriate control group comparisons.

Overall, studies evaluating MABTs for BN and BED have focused on assessment of treatment outcome as their primary aim, with little or no attention afforded to assessment of mediators and moderators. Further, while the small amount of preliminary evidence to date in this regard appears promising, statistical methodologies for assessing such mechanisms of action and moderation should be more sophisticated. The most commonly used methods among studies in this review (assessment of pre-post change in process measures and tests of “proxy” mediation) fail to establish temporal precedence in process variable change, limiting the ability to establish causality.

Future Directions and Recommendations

Recent NIH initiatives call for an increased emphasis on identifying mechanisms of action and moderators of treatment response to assess whether existing treatments truly impact their identified clinical targets (Insel, 2014). The results of our systematic review indicate that despite the growing interest in MABTs for BN and BED, there remains a substantial gap in our understanding of whom these treatments most benefit and how these treatments produce behavioral change. Conducting such research early and consistently across all empirical evaluations of ED treatments will inform more innovative and efficient treatment development and promote efficient use of financial resources when implementing RCTs and future clinical trials. Additionally, by identifying moderators of treatment response, we can begin to identify which patients may be best suited for a given treatment approach and utilize the processes known to best target individual patients’ specific needs. Therefore, we propose several recommendations for future research.

Reducing variability in theorized mechanisms and measurement tools

Our review demonstrated that even within each treatment approach (e.g., ACT, DBT, MBIs), there were inconsistencies in: (1) treatment implementation; (2) hypothesized moderators and mechanisms of action; and (3) the measurement tools used to assess moderators and mechanisms. For example, within MBIs, some treatments attempted to increase mindful eating directly while others aimed to reduce eating pathology by promoting a broader sense of mindful awareness outside of eating episodes directly. Discrepancies such as these can be limited by taking a more systematic approach to constructing treatment packages. Methods for doing so have been suggested through the multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) approach to intervention research and might include conducting analog studies comparing different techniques, or using component analyses to identify which components of a treatment are active in producing behavior change (Collins et al., 2016; Collins, Murphy, Nair, & Strecher, 2005).

Even within studies assessing one specific type of treatment with a strong and consistent theoretical background, there remains large variability in the measures chosen to assess mechanisms. Inclusion of different measures of the same construct makes comparison between trials and replication difficult, slowing progress in treatment development and the identification of key treatment “ingredients.” Additionally, while many studies evaluated one or more hypothesized mechanisms of action consistent to the treatment being used, comprehensive evaluation of all theoretically relevant mechanisms was considerably lacking. For example, many of the core processes theoretically postulated by ACT, such as values clarity and committed action, have not yet been evaluated (or reported on) in MABTs for BN and BED. Understanding which treatment components are truly driving treatment effects can facilitate the development or enhancement of more efficient therapy approaches by identifying therapy components that should be reduced, enhanced, or even removed if not functioning as theorized.

Transparency in results and inclusion of null-findings

In the 27 studies that reported on at least one process measure, it is unclear in many cases whether the authors reported all analyses that were conducted or only those that produced significant results (i.e., the “file drawer” effect). For both mechanisms and moderators, not including null findings in research reports stymies efficient treatment development and slows the pace of advancing research. While part of this problem lies in the mores of research publication (i.e., that null findings are not considered important to publish), researchers may also “cherry pick” significant findings only to include in publication submissions. One strong recommendation to the field is to publish study methods prior to publishing study outcomes to increase researcher accountability in reporting on all observed outcomes. Further, researchers should describe all measures that patients complete during the course of a trial, including those that showed non-significant changes or changed in ways contrary to hypotheses. These null findings, if observed over several trials, can provide useful information about aspects of treatment that may be less necessary in producing treatment gains.

Using appropriate study designs and analytic procedures to assess mechanisms of action

Only seven out of 39 studies included any type of mid-treatment assessment, which dramatically limits the ability to assess mechanisms of action. Statistical methods relying solely on pre- and post-assessments are not sufficient to evaluate mechanisms of action, as they do not provide evidence of mediation beyond improvement in one variable being concurrently associated with improvement in another. Process measures should be administered at multiple time points within a trial to evaluate whether changes in the process measure truly precede changes in an outcome variable (DeRubeis, Gelfand, German, Fournier, & Forand, 2014). The best way to detect this temporal relationship is to administer these measures early in treatment, and often, especially given evidence that early treatment gains (Linardon, Brennan, & De la Piedad Garcia, 2016; Vall & Wade, 2015) and sudden treatment gains (Utzinger, Goldschmidt, Crosby, Peterson, & Wonderlich, 2016) appear particularly important in ED treatment.

Most studies (within the ED field and broadly) that utilize mediation analyses have examined change in the mediator from Time 1 to Time 2 predicting change in outcome from Time 1 to Time 3 (Figure 4). Experts in the field have criticized this approaches’ validity (Lorenzo-Luaces, German, & DeRubeis, 2015), arguing that these analyses may only capture behavioral changes in the first half of treatment that are concurrently associated with change in the mediator, and thus not capture temporal causality. Preacher (2015) outlines how, if seeking to draw causal inferences, analyses must account for elapsed time between a putative cause and its associated effect. Changes in process measures from pre- to mid-treatment should predict subsequent change in the outcome variable from mid to post-treatment. Figure 5 depicts the process necessary to do so.

Figure 4. Mediation (Formal).

In formal mediation, change in process measures from pre- to mid-treatment are used to predict change in the outcome variable from pre- to post treatment. As denoted by the grey arrow, this design still allows for the possibility that in fact early change in the outcome leads to early change in the process variable (which in turn may be related to pre-post change in the outcome variable).

Further, Preacher (2015) provides detailed descriptions of three classes of robust longitudinal mediation models (i.e., methods based on the cross-lagged panel model; latent growth curve modeling; latent change scores) developed and commonly used for such analyses. Macro downloads for SPSS now exist to conduct these analyses (Montoya & Hayes, 2017), and include dropdown menus and simple instructions for assessing mediation. Additional analytic approaches such as multilevel modeling (Hox, Moerbeek, & Van de Schoot, 2017) should also be explored as potential alternatives for evaluating how change is occurring over the course of a treatment. Notably, the majority of these analyses require large sample sizes (n ≥ 100) to achieve the adequate power necessary to detect mediation effects (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). The fact that obtaining samples of this magnitude is often not feasible within clinical trials due to constrains such as time, resources, or location is certainly a limitation of these recommendations at this time. However, as dissemination options continue to increase through use of various technologies, theoretical models continue to be refined, and novel statistical approaches continue to be explored, clinical researchers should still consider the possibilities of examining mediation effects wherever possible within their work. The use of these and similar statistical methods will greatly enhance the meaning and utility of resources invested in researching MABTs for BN and BED.

Summary and conclusions

MABTs show promise for the treatment of BN and BED but assessment of mechanisms and moderators is crucial to enhance the study of treatment efficiency and efficacy. Extant research provides preliminary evidence that theorized mechanisms of action improve across various MABTs for BN and BED, and associations between these improvements and symptom improvement were observed, providing initial support for the theoretical models being used. However, research utilizing more advanced statistical procedures and empirical designs is needed to further understand whether therapeutic changes are derived as theorized. Similarly, few studies have reported on moderators of outcome (n=4), moderators examined varied, and results were largely inconsistent, precluding our ability to identify potential subtypes of individuals for whom certain MABTs may be most helpful. Overall, more research is needed comparing MABTs for BN/BED to treatments with the most empiric support (e.g., CBT), to elucidate the efficacy and efficiency of such treatments and to clarify the potential differences in therapeutic mechanisms and moderators.

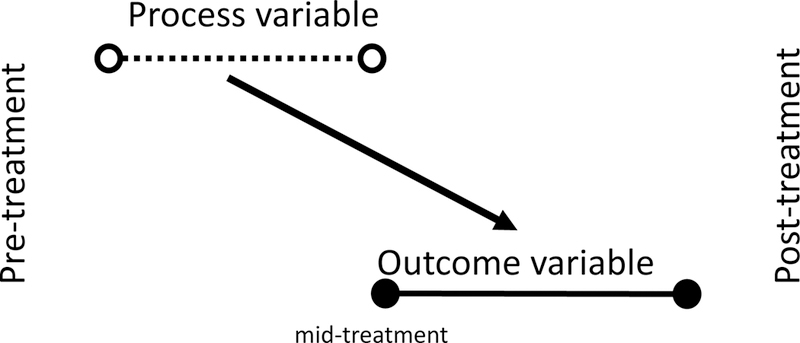

Figure 3. “Proxy” Mediation.

In “proxy” mediation, change in process measures from pre- to post-treatment were correlated with changes in outcome measures from pre-to post-treatment. As denoted by the grey dashed arrow, it is often assumed that change in the process variable change leads to change in the outcome variable, but this “proxy” mediation method leaves the possibility that change in the outcome is causing change in the process variable, or that both changes are being caused by an additional third variable.

Highlights:

Analyses of mechanisms of action and moderators of treatment outcome in MABTs for BN and BED are crucial for enhancing the efficiency of treatment development and dissemination.

Research to date supports improvements in theoretically consistent mechanisms of action from pre- to post-treatment when using MABTs for BN and BED, however conclusions relevant to whether these changes are occurring as theorized are limited by the use of substandard mediation methods, inconsistent measurement tools across studies, and infrequent use of mid-treatment assessment points.

Recommendations for enhancing future research on mechanisms of action and moderators of treatment outcome are discussed.

References

- Agüera Z, Sánchez I, Granero R, Riesco N, Steward T, Martín‐Romera V, … Segura‐García C (2017). Short‐term treatment outcomes and dropout risk in men and women with eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 25(4), 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow B, Kenardy J, & Agras WS (1995). The Emotional Eating Scale: The development of a measure to assess coping with negative affect by eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 18(1), 79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association AP (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) (5th ed.): American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Azari S, Fata L, & Poursharifi H (2013). The Effect of Short-Term Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy in Patients with Binge Eating Disorder. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 1(2), 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Fischer S, & Huss DB (2005). Mindfulness and acceptance in the treatment of disordered eating. Journal of rational-emotive and cognitive-behavior therapy, 23(4), 281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, … Williams JMG (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath DD, Federici A, Wisniewski L, & Warren M (2014). Dialectical behavior therapy: does it bring about improvements in affect regulation in individuals with eating disorders? Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 44(4), 245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath DD, Wisniewski L, & Warren M (2009). Differential treatment response for eating disordered patients with and without a comorbid borderline personality diagnosis using a dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)-informed approach. Eating Disorders, 17(3), 225–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, … Zettle RD (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior therapy, 42(4), 676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauhardt A, de Zwaan M, & Hilbert A (2014). The therapeutic process in psychological treatments for eating disorders: A systematic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(6), 565–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownley KA, Berkman ND, Peat CM, Lohr KN, Cullen KE, Bann CM, & Bulik CM (2016). Binge-eating disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165(6), 409–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzaro SJ, & Mearns J (1990). Measuring generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation: Initial scale development and implications. Journal of personality assessment, 54(3–4), 546–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Cacioppo J, Fettich K, Gallop R, McCloskey M, Olino T, & Zeffiro T (2017). An adaptive randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for binge-eating. Psychological medicine, 47(4), 703–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen EY, Matthews L, Allen C, Kuo JR, & Linehan MM (2008). Dialectical behavior therapy for clients with binge‐eating disorder or bulimia nervosa and borderline personality disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(6), 505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Kugler KC, & Gwadz MV (2016). Optimization of multicomponent behavioral and biobehavioral interventions for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior, 20(1), 197–214. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1145-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Murphy SA, Nair VN, & Strecher VJ (2005). A strategy for optimizing and evaluating behavioral interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 30(1), 65–73. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3001_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Z, & Fairburn C (1987). The eating disorder examination: A semi‐structured interview for the assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Courbasson C, Nishikawa Y, & Dixon L (2012). Outcome of dialectical behaviour therapy for concurrent eating and substance use disorders. Clinical psychology & psychotherapy, 19(5), 434–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courbasson CM, Nishikawa Y, & Shapira LB (2010). Mindfulness-action based cognitive behavioral therapy for concurrent binge eating disorder and substance use disorders. Eating Disorders, 19(1), 17–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte C, Pinto‐Gouveia J, & Stubbs RJ (2017). Compassionate Attention and Regulation of Eating Behaviour: A pilot study of a brief low‐intensity intervention for binge eating. Clinical psychology & psychotherapy, 24(6), O1437–O1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Farmer A, & Mehlenbeck R (2013). A condensed dialectical behavior therapy skills group for binge eating disorder: Overcoming winter challenges. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 27(4), 338–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C, & Beglin SJ (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C, Wilson GT, & Schleimer K (1993). Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment: Guilford Press New York. [Google Scholar]

- Feigenbaum J (2007). Dialectical behaviour therapy: An increasing evidence base. Journal of Mental Health, 16(1), 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Forman EM, Chapman JE, Herbert JD, Goetter EM, Yuen EK, & Moitra E (2012). Using session-by-session measurement to compare mechanisms of action for acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive therapy. Behavior therapy, 43(2), 341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, & MacKinnon DP (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological science, 18(3), 233–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey KM, Gallo LC, & Afari N (2015). Mindfulness-based interventions for binge eating: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(2), 348–362. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9610-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment, 26(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, & White MA (2011). Cognitive–behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge-eating disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 79(5), 675. doi: 10.1037/a0025049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & John OP (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of personality and social psychology, 85(2), 348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]