Abstract

This analysis reflects on experiences and lessons from four country settings—Zambia, India, Sweden and South Africa—on building collaborations in local health systems in order to respond to complex health needs. These collaborations ranged in scope and formality, from coordinating action in the community health system (Zambia), to a partnership between governmental, non-governmental and academic actors (India), to joint planning and delivery across political and sectoral boundaries (Sweden and South Africa). The four cases are presented and analysed using a common framework of collaborative governance, focusing on the dynamics of the collaboration itself, with respect to principled engagement, shared motivation and joint capacity. The four cases, despite their differences, illustrate the considerable challenges and the specific dynamics involved in developing collaborative action in local health systems. These include the coconstruction of solutions (and in some instances the problem itself) through engagement, the importance of trust, both interpersonal and institutional, as a condition for collaborative arrangements, and the role of openly accessible information in building shared understanding. Ultimately, collaborative action takes time and difficulty needs to be anticipated. If discovery, joint learning and developing shared perspectives are presented as goals in themselves, this may offset internal and external expectations that collaborations deliver results in the short term.

Keywords: governance, collaborative governance, local health systems, coordination, collaboration, shared motivation

Summary box.

The presence of common problems and initiating leadership provide the conditions for collaborative action in local health systems.

Actors, however, need to learn how to collaborate through principled engagement.

Trust and trust building are central to developing shared motivations for collaboration.

Jointly developed new knowledge—through shared data, evaluations or reflective processes—creates capacity for collaboration.

The considerable work involved in building and maintaining collaborative action needs to be acknowledged.

Introduction

Health systems across the globe face a growing disconnect between the complex and ‘wicked’ nature of problems confronting them and their capacity to respond meaningfully. Ageing populations, rapid urbanisation, changing food environments and deepening social and economic inequalities have generated a host of new health challenges and landscapes of need. They include growing burdens of chronic, lifelong illness (HIV and non-communicable diseases), mental illness and violent injury. New thinking in service provision, such as ‘people-centred’, integrated models of care,1 community-based delivery, forms of social accountability, quality improvement and e-health technologies, go some way to providing conceptual and practical tools for navigating the new realities.

However, these innovations are embedded in wider health system contexts that are often characterised by organisational fragmentation and siloed functioning.2–4 The ‘disarticulated state’5 is the end result of a variety of forces impacting health systems in both the global north and south: proliferation of donor aid and vertical health programmes in the Millennium Development Goal era,6 New Public Management reforms and the splitting of purchaser and provider functions,7 8 various forms of decentralisation and the growth of private (for profit and non-governmental) health sectors.4 8 The prevailing institutional norms and incentives in many health systems are to compete rather than collaborate. Yet, addressing complex health needs requires new and better coordination between levels and actors within health systems and between health and others sectors.

This analysis reflects on experiences and lessons from four highly divergent contexts, each grappling with how to achieve collaborative action within local health systems to address an unmet need. Using a common framework of collaborative governance,9 four case studies are presented. The health needs they address are:

Improving access to healthcare for elderly populations in rural northern Sweden through ‘virtual health rooms’ (VHRs).

Responsive, multisectoral approaches to improving well-being in vulnerable local communities in the Western Cape Province, South Africa.

Increasing knowledge and access to adolescent sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services through the community health system in rural Zambia.

Introducing systems of care for epilepsy in primary healthcare in Uttarakhand State, India.

Collaborative governance is a non-hierarchical mode of governance defined as ‘the processes and structures of public policy, decision making and management that engage people constructively across the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished’.9 This definition and the accompanying framework by Emerson10, while intended for analysing formal collaborative governance arrangements such as multisectoral agreements, is also valuable for considering the challenges of coordination in the ‘everyday governance’11 of local health systems. The four case studies span these degrees of formality, from coordinating action in the community health system (Zambia), to initiating access to epilepsy care among a range of health sector governmental, non governmental organisation (NGO), community and academic actors (India), to joint planning and delivery across political and sectoral boundaries (Sweden and South Africa).

This paper presents an overview of, and lessons from the four case studies, that were all authored by players integrally involved in steering, supporting and/or researching the initiatives they describe. The cases were the basis of an organised session at the 5th Global Symposium on Health Systems Research in Liverpool in October 2018. Case study reports were developed following Emerson et al’s9 Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance, outlining contexts, collaboration drivers, timelines, key actors, achievements, processes and key lessons learnt (online supplementary files 1-4). These were discussed in a world café format at the Symposium, and notes were compiled.

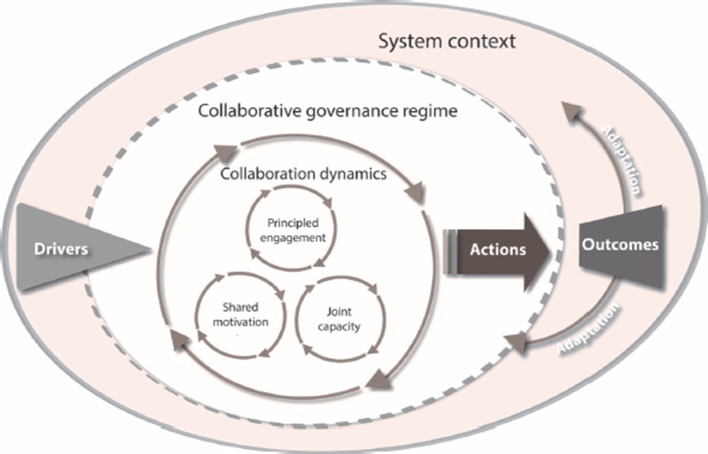

Based on the case study reports and notes, this analysis specifically seeks to shed light on the process dimensions of building collaborative action, referred to as ‘collaboration dynamics’ in Emerson’s framework (figure 1). Collaboration dynamics entail three interacting processes: (1) principled engagement that involves elements of ‘discovery’, ‘definition’, ‘deliberation’ and ‘determination’, through which actors come to understand each other’s interests and define a common purpose; (2) shared motivation refers to relational aspects of ‘trust’, ‘legitimacy’, ‘commitment’ and ‘mutual understanding’; and (3) joint capacity—the ‘procedural arrangements’, ‘knowledge’, ‘resources’ and ‘leadership’ required for the collaboration to proceed.

Figure 1.

Integrated framework for collaborative governance Source: Reproduced with permission from (10).

Table 1 summarises the setting/context, focus of collaboration, actors involved and evidence used to draw up the case studies.

Table 1.

Context, focus of collaboration, key actors involved and evidence used in constructing the case studies

| Case study | Key contextual factors | Focus of collaboration | Actors collaborating | Evidence for case study |

| Increasing access to care through virtual health rooms, northern Sweden |

|

Establishment of virtual health rooms in community settings with e-health technologies able to conduct remote consultations and follow-up of elderly patients without the presence of professionals. |

|

|

| Whole of Society Approach (WoSA) in the Western Cape Province, South Africa |

|

Multisectoral collaboration in four learning sites in the province bringing together provincial and municipal authorities, civil society and the private sector to address community needs in four local areas. |

|

|

| Community-based adolescent sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services in Nyimba District, Zambia |

|

Coordinated action in the community health system, led by CHAs, to address social norms and increase access to adolescent SRH. |

|

|

| Primary care (PC) epilepsy health systems project—Dehradun District, Uttarakhand, India |

|

Integration of epilepsy care into primary healthcare facilities; ensuring availability of drugs; building community awareness and healthcare seeking behaviour. |

|

|

NCDs, non-communicable diseases; TB, tuberculosis.

Drivers and achievements of collaboration

Across the case studies, the immediate driver of collaboration was consensus on a significant problem (whether broadly or specifically framed), recognised as beyond any individual actor’s capacity to solve: in Sweden, increasing numbers of elderly people needing follow-up care; in Zambia, conservative social norms placing the lives of adolescents at risk; in India, the absence of primary care for a relatively common condition; and in South Africa, a set of intractable social problems confronting several sectors simultaneously.

Initiating leadership10 was a necessary condition for collaboration in all four cases: in India and Sweden, this leadership came principally from one actor (Emmanuel Hospital and Centre for Rural Medicine, respectively), whereas in Zambia and South Africa, impetus and leadership came from several quarters. Collaboration was enabled by authorising directives and support from above: the National Mental Health Policy in India, clarification of community health assistant roles by the national government in Zambia and new strategic thinking and frameworks in the Western Cape. In Sweden, a well-connected local innovation hub developed the concept of the VHRs and was able to mobilise a national profile and funding from the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth.

All four cases succeeded in achieving some degree of local collaborative action. The agreements forged between municipalities and county councils led to the establishment of the first VHR, with seven additional ones planned in two counties of northern Sweden; in the context of a very high turnover of decision makers, coordinated action by frontline, district and state players ensured that the first patients with epilepsy started receiving treatment in government primary health centres in Dehadrun District, India; a collective of community-based players delivered adolescent sexual and reproductive services in health facilities, schools, police stations, home settings and community spaces in Nyimba District, Zambia; and entirely new modes of engagement—horizontally between sectors and vertically between levels of government and communities were fashioned in the Western Cape Province.

The next section introduces the four case studies and describes the dynamics underpinning their experiences of collaboration, addressing elements related to the constructs in Emerson’s framework of principled engagement, shared motivation and capacity for joint action.

Collaboration dynamics

Virtual Health Rooms in northern Sweden

VHRs are located within community structures and make use of sophisticated e-health technology to provide health services to remote rural areas. They are implemented through new partnerships between municipalities, county councils, community structures and patients. The leadership of the Centre for Rural Medicine (a centre of innovation associated with one of the county-administered community hospitals) took the first steps to engage county council, municipal and community actors, establishing a pilot VHR in 2013. The VHR concept resonated well with these actors and provided a fit with the need for innovative ways of providing follow-up care to the elderly living in rural areas.

A number of factors have enabled the establishment of VHRs. County councils and municipalities have shared responsibilities for the care of the elderly and a shared motivation to work on solutions. They had previously been engaged in different collaborative activities. The formation of ‘stakeholder’ and ‘steering’ groups provided the procedural arrangements for joint discussion and decision making on the VHRs specifically. The buy-in from communities has also been important. Open meetings with community members have been essential for building trust. Moreover, the VHRs offered new social spaces for the elderly and new roles for auxiliary nurses employed by the municipalities, who often accompany patients for the follow-up consultations in the VHR.

The VHRs have also been propelled by wider interest in the initiative. Champions among patients and innovators were interviewed frequently in the media about the experiences of the first VHR, giving it profile and status. Northern Sweden has historically sought to be at the forefront of e-health development and funding from the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth supported the establishment of new VHRs, adding to their legitimacy.

While many communities have shown interest in and seen the benefits of VHR, there are also some who see them as a threat and a replacement of ‘real’ services. There exists a degree of mistrust of the ‘central’ level of the health system by peripheral communities who perceive services to be declining. How VHRs are seen by users and communities is obviously key to their sustainability. The future of the first VHR and the scale up will also depend on ongoing capacity for joint action across authorities. The procedural and institutional arrangements for managing VHRs depend on highly motivated individuals at county, municipality and community levels. The lack of incentives to engage with e-health initiatives among service providers, outside a pilot initiative or project, is a recognised challenge. There are also questions on how to introduce a standardised data transfer system and how to ensure data confidentiality.

Whole of Society Approach (WoSA) in the Western Cape, South Africa

The WoSA is an initiative of the Western Cape Provincial Government that seeks to ‘embed and institutionalise a collaborative approach to service delivery which includes local, provincial and national government, state-owned institutions, the private sector and civil society to address a community’s specific needs, thereby creating “public value” in the communities concerned’.12 A focus on ‘well-being’ and addressing the social determinants of health has formed part of strategic thinking in the provincial health department since 2011. The WoSA initiative emerged from a series of province-wide experiments with cross-sectoral action, starting in 2014, that initially produced a series of top down, vertical, sector-specific interventions all targeting the same communities and with little impact. A subsequent experience with integrated spatial service delivery in one area led to the fundamental reconceptualisation of intersectoral action, and the basis of four WoSA sites—two rural and two urban—from 2017 onwards.

Addressing the long-standing mistrust between government and communities is the main short-term goal of WoSA. In this regard, ‘key design principles’ emphasise the importance of collaborative learning, developing shared mandates, distributed leadership, creating spaces for joint exploration of problems, responding to felt needs rather than imposing programmes from the top and values of ethical engagement, citizen-centredness and social inclusion.12 An external, public interest NGO has been contracted to facilitate local engagement. At a formal level, collective planning processes have been instituted that align the municipal and 13 provincial department plans in each site. These are aided by the development of common data repositories based on a ‘spatial indicator framework’ for each site, as well as a series of WoSA governance structures, which connect decision making at the frontline to that of senior managers and politicians.

WoSA is in the early phases of implementation, limited to four local areas, and has been given the latitude to innovate. Priorities may change with new political leadership. The over-riding incentive to focus on individual mandates and reporting in government bureaucracies is another ongoing threat.

Community-based SRH services in Nyimba District, Zambia

In 2010, the Ministry of Health in Zambia developed the National Community Health Assistant (CHA) strategy. The CHAs were introduced to promote SRH services in the midst of a variety of other community-based cadres and structures in Zambia, such as nurses and environmental health technicians (who together supervise the work of CHAs), community health workers and safe motherhood action groups. The CHAs are also expected to work with neighbourhood and health centre committees in mobilisation processes, while at the same time, these structures are also supposed to play an oversight role. In this complex dynamic, the manner in which CHAs position themselves in relation to other actors and how they navigate and negotiate community relationships is key to achieving collaboration for improved SRH.

When they were first introduced, the CHAs faced opposition from the other cadres, due among other things, to a lack of clear definition and communication of the CHA tasks. National government then moved to define CHA tasks and communicate this to other health providers, district authorities and community leaders.

Leveraging the agreements reached through the national government process, the CHAs exercised their agency to successfully negotiate the micropolitics of collaboration among health workers and community-based cadres on SRH. The CHAs used their health facility service delivery role to gain trust and entry into the community and promote shared motivations. They then built relationships of reciprocity with other community-level actors, holding regular joint meetings (deliberative processes) and acting as brokers between the volunteer health workers and the Ministry of Health. CHAs also capitalised on these social networks to deliver SRH services to adolescents (joint capacity). By embedding the provision of information about SRH into general life skills at community level, the topic’s sensitivity was reduced, and its acceptability was enhanced. However, logistical challenges such as limited supplies, competition from some health providers and busy work schedules also affected joint action.

Primary care for epilepsy in Uttarakhand State, India

Approval of the National Mental Health programme (NMHP) for implementation across Uttarakhand State in September 2016 was a catalyst for three partners (the Department of Health (DOH), the non-profit, the Emmanuel Hospital Association (EHA), and the academic institution, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) – Delhi) to respond to a funding call for implementation research projects. The joint proposal submitted was for research to support the establishment of primary care epilepsy services in public health centres. While there was a strong initial synergy with all three partners, the transfer of the State Secretary of Health reduced DOH engagement. The awarding of funding, however, promoted synergy between the non-DOH partners. The process of implementation stopped and started, while relationships and trust were built with the DOH, and then repeatedly renegotiated as key implementers were transferred.

Although the proposal was implementing an agreed strategy (the NMHP), the actual delivery of epilepsy care in primary and community health centres was a novel practice. The DOH team were unsure if there could be negative ramifications for them in implementing the strategy, which slowed decision making and the supply of antiepilepsy drugs. The parties were somewhat asymmetrically involved, with AIIMS – Delhi participating as a supportive consultant and EHA as the prime driver of the project.

Assessing capacity for joint action, the following were the strengths and contributions of each partner:

DOH: new team and staff in non-communicable diseases committed to implementing sanctioned guidelines. Some key functionaries such as district pharmacists and primary care doctors were active and understood the system sufficiently to work around administrative inertia.

AIIMS – Delhi: an energetic and committed approach to primary epilepsy care with contributions of human resources beyond those needed by the partnership.

EHA: local leadership and commitment to the partnership, with a strong implementation team and pre-existing relationships with the DOH and community.

All three partners’ participation and engagement in the partnership was ultimately critical to the eventual positive outcomes. These built on relationships of trust that were in place prior to this partnership.

No attempts were made to establish formal structures, such as a steering committee, and there was no clear process accounting for participation and engagement of DOH, which slowed engagement in the project initially. In addition, progress was impeded by repeated staff transfers at all levels including the State NHM Director—a position occupied by four different people in 12 months.

Table 2 summarises the main themes in the collaboration dynamic in each of the cases, along the three constructs of principled engagement, shared motivation and joint capacity.

Table 2.

Summary of collaboration dynamics

| Principled engagement | Shared motivation | Joint capacity | |

| Sweden |

|

|

|

| South Africa |

|

|

|

| Zambia |

|

|

|

| India |

|

|

|

AIIMS, All India Institute of Medical Sciences; CHA, Community Health Assistant; DOH, Department of Health; EHA, Emmanuel Hospital Association; USAID, United States Agency for International Development; VHR, virtual health rooms.

Conclusions

Despite their differences, the four case studies offer some common insights into the nature of collaboration dynamics. First, collaborative action in local health systems requires a jointly recognised problem and set of solutions to the problem. Problem definitions may be generated by others (such as adolescent SRH in Zambia and mental health in India), but collaborative action always involves coconstruction of specific solutions within local contexts.

Second, the currency of collaborative action is trust. Trust is both interpersonal between key actors and entails a degree of institutional trust in actors’ capacity to deliver on collaborative agreements.13 Where there are pre-existing trust relationships (such as In India and Sweden), initial collaborative arrangements may be agreed relatively easily. Where mistrust and suspicion are deep rooted (South Africa), the first goal in a collaborative arrangement is to build trust, prior to the development of formal agreements. This may require attention to asymmetries of power in the design of collaborative arrangements, the involvement of intermediaries (South Africa) or by showing goodwill through acts of reciprocity unconnected to the collaboration (Zambia).

Third, the development of collaborative action takes time and difficulty needs to be anticipated. Collaborations may proceed at the pace of the weakest link in the chain of the partnership (India), and need to start small, becoming more ‘mature’ with time. Strategies that incorporate joint critical reflection, relationship building and learning as goals in themselves (South Africa) may offset internal and external expectations that collaborations deliver results in the short term.

Fourth, collaborative action rests on mobilising the existing networks and resources of partners in the collaboration (all four cases) and may also require finding sustainable sources of additional funding (Sweden). Open access to knowledge is a key resource: compilations of routine information, action–reflection cycles and evaluations provide the platforms for shared understandings.

Finally, shared motivations among core groups of actors are the starting points for collaborations. However, as these expand and develop, they inevitably confront wider institutional environments, requiring new iterations of engagement, trust building and joint determinations.

In an era where the sustainable development goals have established expectations of greater synergy, this analysis has demonstrated the considerable challenges and the specific dynamics involved in developing collaborative action in local health systems. Common problems and initiating leadership create the conditions for collaboration. The Integrated Collaborative Governance Framework provides a valuable framework for systematising investigation into the dynamics of collaboration beyond this, highlighting the nature and ongoing ‘work’ of collaboration. In this regard, the case studies offer useful lessons, including recognising the need to learn how to collaborate through principled engagement, the central roles of trust and trust building in developing shared motivations and the value of jointly developed new knowledge as part of collaborative processes.

bmjgh-2019-001645supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001645supp002.pdf (2.9MB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001645supp003.pdf (2.5MB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001645supp004.pdf (2.1MB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

The case studies were presented at an organised session entitled: New frontiers in community-based health systems: experiences in the collaborative governance of innovations that expand access, at the 5th Global Symposium on Health Systems Research, Liverpool, 8–12 October 2018. http://healthsystemsresearch.org/hsr2018/. We would like to thank our colleagues who participated in developing the case studies and/or the organised session: Isabel Goicolea, Vardharajan Srinvasan, Ida Okeyo, Wolde Amde, Chama Mulumbwa and Charles Michelo.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: The case studies (supplementary files and text in the main article) were drawn up by each of the authors, with the lead author providing overall coordination. HS drafted the overall manuscript. All authors commented on and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: U2U (Umeå-UWC) Collaboration on Health Policy and Systems Research: Strengthening community health systems, funded by the South African National Research Foundation (NRF)/Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (STINT), Science and Technology Research Collaboration (Grant UID: 106770).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. World Health Organization Framework on integrated, people-centred health services. (Report by the Secretariat to the 69th World Health Assembly. Geneva: World Health Assembly, World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barr A, Garrett L, Marten R, et al. . Health sector fragmentation: three examples from Sierra Leone. Global Health 2019;15:1–8. 10.1186/s12992-018-0447-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nilsson P, Stjernquist A, Janlöv N. Fragmented health and social care in Sweden - a theoretical framework that describes the disparate needs for coordination for different patient and user groups. Int J Integr Care 2016;16:348–8. 10.5334/ijic.2896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McIntyre D, Garshong B, Mtei G, et al. . Beyond fragmentation and towards universal coverage: insights from Ghana, South Africa and the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:871–6. 10.2471/BLT.08.053413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Emerson K, Nabatchi T. Collaborative governance regimes. Washington D.C: Georgetown University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pallas SW, Ruger JP. Effects of donor proliferation in development aid for health on health program performance: a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med 2017;175:177–86. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pavolini E, Kuhlmann E, Agartan TI, et al. . Healthcare governance, professions and populism: is there a relationship? An explorative comparison of five European countries. Health Policy 2018;122:1140–8. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dahlgren G. Why public health services? experiences from profit-driven health care reforms in Sweden. Int J Health Serv 2014;44:507–24. 10.2190/HS.44.3.e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Emerson K, Nabatchi T, Balogh S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2012;22:1–29. 10.1093/jopart/mur011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Emerson K. Collaborative governance of public health in low- and middle-income countries: lessons from research in public administration. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(Suppl 4):e000381:1–9. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gilson L, Lehmann U, Schneider H. Practicing governance towards equity in health systems: LMIC perspectives and experience. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:1–5. 10.1186/s12939-017-0665-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saldanha Municipality, Western Cape Government The Whole of Society Approach (WoSA) to Socio-Economic Development: Framework document for the Saldahna Bay Municipality and the Western Cape Government. Cape Town: Western Cape Government, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gilson L. Trust and the development of health care as a social institution. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:1453–68. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00142-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2019-001645supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001645supp002.pdf (2.9MB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001645supp003.pdf (2.5MB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001645supp004.pdf (2.1MB, pdf)