Abstract

Background:

In MTN-020/ASPIRE, a dapivirine vaginal ring effectiveness trial in sub-Saharan Africa, we assessed whether worries about ring use changed over time and were associated with adherence.

Methods:

Participants (N=2585) were surveyed at baseline and follow-up about worries regarding daily ring use. First, they answered a question about general worries and then responded to 15 items covering specific worries. From a nested qualitative component (N=214), we extracted themes related to ring worries and adherence. Seven months into the trial, aggregate adherence data were shared with study sites as part of an intervention that included counseling and social support. Nonadherence was defined as dapivirine plasma levels of ≤95 pg/ml. Mixed-effect logistic regression models were used to assess changes in ring worries and nonadherence from baseline to month 3 and later.

Results:

Worry about wearing the ring decreased from 29% at baseline to 4% at month 3 (p<0.001), while having a specific worry decreased from 47% to 16% (p<0.001). Among those enrolled preintervention, 29% with baseline worries were nonadherent at month 3 (95% CI: 19%, 39%) compared to 14% without worries (95% CI: 9%, 19%; p=0.005); the difference persisted through month 6. There was no difference in nonadherence by baseline worry for those enrolled postintervention (p=0.40). In the qualitative subset, initial ring anxieties reportedly subsided with self-experimentation and practice and the beneficial influence of the intervention.

Conclusions:

Although worries may be an initial deterrent to correct ring use, intervening early by leveraging social influences from peers and clinicians should facilitate successful adoption and correct ring use.

Keywords: HIV Prevention, Microbicides, Pre-exposure Prophylaxis, Africa, women

INTRODUCTION

HIV-1 infection is a public health challenge, especially for women in sub-Saharan Africa, and efforts to develop woman-specific prevention technologies are ongoing.1,2 The monthly dapivirine vaginal ring is one such technology, which has shown modest but statistically significant HIV-1 risk reduction in two phase III clinical trials, MTN-020/ASPIRE (A Study to Prevent Infection with a Ring for Extended Use), and The Ring Study, and improved (>50%) effectiveness with higher ring adherence in open-label extension studies.3–7

Although the monthly ring offers potential adherence benefits over daily or on-demand methods, it is a new technology unfamiliar to most women in sub-Saharan Africa. Accordingly, it may generate worries, defined here as feeling or experiencing concerns and/or anxiety. These, in turn, if not addressed, can impair uptake and continued use of prevention methods.8,9 Indeed, the vaginal ring is a user-controlled method, and effectiveness hinges on correct use.

Multiple clinical trials have evaluated the acceptability of the dapivirine ring among reproductive-aged women in Africa.10,11 In ASPIRE and other studies, women reported initial fears about the ring’s unfamiliar appearance, placement in situ and side effects,10,12–14 as well as concerns about the ring interfering with sex and/or being noticed by the sex partner.15 Nevertheless, with use and increased familiarity, participants appreciated the ring, found it easy to use and to integrate into their lives and favored it over other delivery forms such as daily oral pills or condoms.14,16 Seven months into the ASPIRE trial, aggregate adherence data were shared with study teams as part of an intervention that included counseling and social support to improve adherence and retention.17,18

The purpose of this paper was to further investigate worries about ring use during the ASPIRE trial. Specifically, we assessed if reported ring worries at baseline 1) persisted after participants started using the ring, 2) influenced ring adherence during follow-up, and if so, 3) what factors may have mitigated or attenuated worries.

METHODS

MTN-020/ASPIRE (2012–2015) was a multicenter, double-blind, phase III randomized controlled trial of a monthly silicone elastomer matrix ring containing 25mg of dapivirine (NCT: 01617096). Details of the trial’s main results were previously reported.3 Briefly, 2629 women were enrolled in Malawi, South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe and were randomized 1:1 to receive a dapivirine or placebo ring. Participants returned for monthly follow-up visits for ≥12 months (maximum 33 months). At each visit, women received HIV-1 serologic and pregnancy testing, one-on-one HIV risk reduction counseling and condom provision, safety monitoring, and individualized adherence counseling. Women were counseled to wear the ring for the entire month and received a new ring at every visit.

Starting in March 2013 (seven months after the first enrollment), numerous site-specific participant engagement activities were implemented to improve adherence and retention in the trial, including adherence workshops, retention meetings, waiting room educational talks, social gatherings (“tea parties,” movie days, holiday parties), on-site study lab visits, and male partner meetings.18 Concurrently, monthly aggregate summary data on dapivirine plasma levels were provided to study teams regarding study participants’ adherence to the ring.17 As part of this adherence monitoring strategy, during ASPIRE meeting events, participants received feedback on estimates of their research site’s aggregate level of adherence relative to other sites. Data on individual women were not provided to participants or the study team to preserve blinding. We refer to the participant engagement activities and adherence monitoring strategy as the ‘ASPIRE intervention.’ Of note, all participants in Malawi were enrolled post-intervention.

The ASPIRE study protocol, including its qualitative component, was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each of the corresponding study sites, and was overseen by the regulatory infrastructure of the US National Institutes of Health and the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN). All participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

Ring worries.

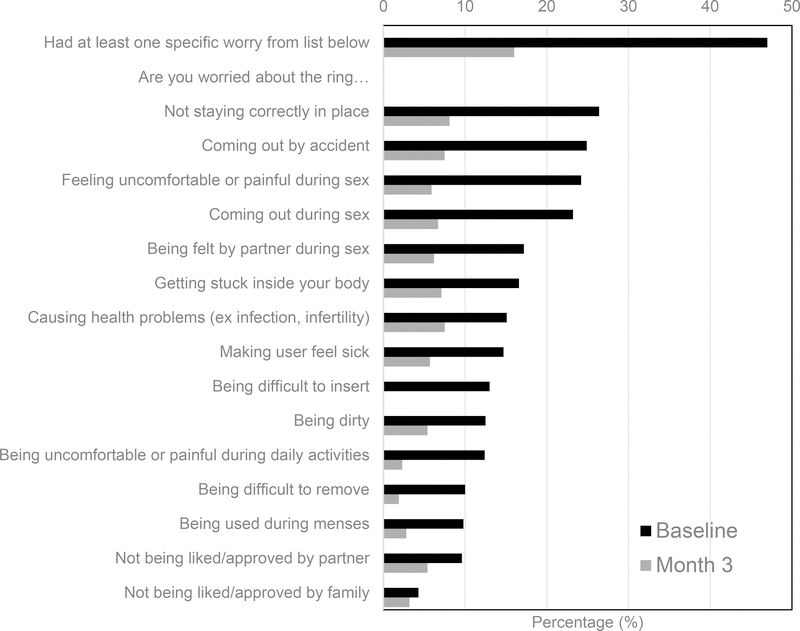

Over the course of three visits (i.e., at enrollment, month 3, and at study product discontinuation visit [PDV]) participants were asked, through a quantitative survey administered by a trained interviewer, if they had worries about using the ring during the ASPIRE trial. Women were first asked generally, “How worried are you about having a vaginal ring inside of you every day for at least a year?” (Possible responses were: very, somewhat, or not-at-all worried; general worry, dichotomized as very/somewhat worried and not-at-all worried). Next, (regardless of response to the general worry question) all women were asked a series of 15 yes/no questions regarding specific worries they might have about the ring. The questions were derived from findings in previous clinical studies,11,19,20 and assessed concern with use attributes, health, hygiene, sex, and social approval (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Percentage of women who answered ‘yes’ to a series of 15 questions regarding specific worries they might have about using the vaginal ring, at baseline and after 3 months of use (N=2585). There was a significant decrease in worries about the ring by the month-3 visit (p<0.001).

Adherence.

In women randomized to the active ring, adherence was measured quarterly by dapivirine plasma levels,17 with a cutoff at ≤95 pg/ml indicating little or no ring use in the 8 hours prior to blood collection.21 Therefore, a participant was considered nonadherent if the dapivirine plasma level was ≤95 pg/ml.

Study Sample and Analysis

All participants with follow-up data related to ring worries were included in the quantitative analyses. Fishers exact test was used to compare baseline ring worries of those with and without follow-up data. Visits occurring after product hold or seroconversion were excluded. The adherence portion of the analysis included women randomized to the dapivirine ring who had access to the ring in the previous month. Age group was dichotomized as younger (18–21 years) versus older (22–45) women. Mixed-effect logistic regression models were used to assess longitudinal patterns of change in general and worries specifically by age group and enrollment status (before or after the start of the ASPIRE intervention), controlling for country and time in study (i.e., number of months enrolled). A mixed-effect logistic regression model was also used to evaluate longitudinal changes in nonadherence; the model included an interaction between baseline general worry, enrollment pre-ASPIRE intervention, and visit, and it adjusted for age group, country, and time in study. All models included a random intercept to account for correlation of repeated measures within a participant. Analyses were conducted using Stata 15.0.22

We conducted a nested qualitative study (N=214), within the larger ASPIRE trial, across all four countries, using a combination of random and purposive sampling, as described previously.12 Qualitative participants contributed to single or serial interviews or exit focus-group discussions conducted in local languages by trained social scientists, following semi-structured guides. Topics covered a range of ring adherence and acceptability issues. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, translated, uploaded into NVivo11 qualitative software, coded, and analyzed. We previously reported on codebook development and high (>90%) intercoder reliability maintenance.12 To elucidate the quantitative findings, we reviewed code reports pertaining to various aspects of ring adherence: REMOVAL, EXPULSION AND EXECUTION, and ACTIVITIES, which captured data relative to the ASPIRE intervention. From these reports, we conducted a matrix analysis from which we drew interview excerpts that described participants’ fears or concerns about the ring and their influencers. Exemplary quotes are presented for illustrative purposes in the Results section.

RESULTS

Of the 2629 women enrolled in the ASPIRE study, 2585 (98%) provided follow-up data regarding ring worries and were included in the quantitative analysis. Baseline worries about the ring were not significantly different between those with and without (n=45) follow-up data (p=0.38). The median follow-up time was 24 months (interquartile range, IQR: 15–30). Characteristics of participants are described in Table 1. The median age was 26 (range 18–45) years, with 20% of women between the ages of 18 and 21. Almost half (46%) completed secondary school. Nearly all (99.6%) had a primary sex partner in the past 3 months.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Sample Enrolled in MTN-020/ASPIRE Vaginal Ring Trial (2012–2015).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 2585 | (100) |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 26 | (22–31) |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 18–21 | 511 | (20) |

| 22–45 | 2074 | (80) |

| Currently married | 1061 | (41) |

| Secondary school education or higher | 1182 | (46) |

| Earns own income | 1169 | (45) |

| Had primary sex partner past 3 months | 2574 | (99) |

| Condom use during last vaginal sex | 1481 | (57) |

| Contraceptive method | 2585 | (100) |

| Injectable | 1425 | (55) |

| Implant | 495 | (19) |

| Intrauterine device (IUD) | 321 | (12) |

| Oral contraceptives | 280 | (11) |

| Male condom | 94 | (4) |

| Male sterilization | 77 | (3) |

| Country | ||

| South Africa | 1394 | (54) |

| Zimbabwe | 673 | (26) |

| Malawi | 268 | (10) |

| Uganda | 250 | (10) |

At baseline, 29% of women (95% CI: 28%, 31%) expressed that, in general, they were very (1%) or somewhat (28%) worried about using the ring every day. When asked the series of specific worry questions, 47% voiced at least one specific worry (95% CI: 45%, 48%). The most common specific worries were the ring not staying in place (26%), coming out by accident (25%), causing discomfort or pain during sex (24%), and coming out during sex (23%). Few were worried about social approval from family (4%) or their male partner (10%, see Figure 1). Of those with specific worries, the median number of worries was four (interquartile range 2–7).

In corroborating the quantitative data on baseline specific worry, some of the more salient worries in the qualitative subsample focused on the ring interfering with sex, the ring being out of place or falling out, and whether the ring could be harmful to their health. In South Africa, several participants had specific concerns about vaginal insertion: “I was afraid of inserting something down my vagina. I don’t know what it was going to do to me” (Lesedi, IDI, South Africa), or the widening effect of the ring on the vagina “I removed it because it was said that I will have a wide vagina (Ivory, FGD, South Africa). A few participants were worried that the ring would be “pushed up” during sex, and early on, this led to sex-associated ring removals, as reported by Anelisa:

One of the things that made me not to use the ring is that I was scared to have it on me during sex. I was scared it might be pushed up and what will happen after? (IDI, South Africa)

The fear that the male partner would notice the ring during sex and react to it was the most salient concern expressed by participants across all countries:

Some have not disclosed to their husbands so they are scared that if they insert the ring her husband may feel it...So when they get home they remove it (Mbira, IDI, Zimbabwe).

A fear of the ring coming out by accident was also frequently reported at first, mostly when going to the toilet. Nanteza shared: “Walking was never a problem, because on the first day when they inserted it I walked out of the room feeling nothing. I only got worried whenever I went to the toilet thinking it would fall out” (IDI, Uganda). Similarly, Florence explained that the novelty of inserting a device vaginally and not feeling it when wearing it, made her worry she may have lost it: “Maybe during the early days in the study when I was afraid that if I go to the toilet, it might drop in the toilet” (IDI, Malawi). She was reassured by staff that it was normal to not feel the ring when properly placed, and with practice, she overcame these initial fears.

Baseline general ring worry differed significantly by country, with more general worry in South Africa (43%) and Uganda (33%) than in Zimbabwe (6%) and Malawi (8%), p<0.001. This difference was persistent even among those enrolled after the start of the adherence intervention. Similarly, more women in South Africa (66%) and Uganda (76%) had at least one specific worry; however, their most common specific worries did not differ. Odds of having general worry or any of the specific worries at baseline did not significantly differ by age group (p≥0.08). Women who discontinued the study early (<12 months of follow-up, n=178) were more likely to have general worry about the ring at baseline (AOR 1.58, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.10, 2.27; p=0.01). Women enrolled before the start of the ASPIRE intervention had higher odds of general ring worry at baseline (AOR 2.26, 95% CI: 1.68, 3.03; p<0.001).

After 3 months of use, there was a significant decrease in general and specific worries about the ring (p<0.001), with 4% (95% CI: 3%, 5%) expressing a general worry and 16% (95% CI: 14%, 18%) expressing at least one specific worry. Overall, the most common specific worries at month 3 were the ring not staying in place (8%), causing health problems (8%), coming out by accident (8%), and getting stuck inside (7%). Odds of general or specific worries at month 3 did not differ between those enrolled pre/post the ASPIRE intervention (p>0.2 for both). At PDV/study exit, 2% had general worry (95% CI: 1%, 2%) and 7% had specific worries (95% CI: 5%, 8%).

As explained in qualitative interviews, ring worries were dispelled in several different ways. First, as highlighted above, practice and experience eased concerns. Second, some women conducted personal experimentations. Thokozani explains:

It was that time I was sick, I thought it was the ring which was making me sick and I took it out. [..] When I went to take a bath, I was still not feeling well and I just decided to reinsert it back because I was not feeling better after I removed it. (IDI, Malawi)

Dembe directly compared her sexual experience with her husband and her boyfriend and concluded: “When I realized that my husband couldn’t feel it [the ring] I got to know that my other boyfriend wouldn’t have felt it, too, so I realized that it was wrong for me to remove it” (IDI, Uganda).

Thirdly, worries were dispelled by educating women at the clinic so they gain knowledge about the ring. Participants spoke often of the beneficial influence of staff and the education they received. For example, Nanteza spoke of “the counseling that made my heart strong,” which motivated her to use the ring correctly by only removing it “in the doctor’s office” (IDI, Uganda).

Fourthly, and most prominently, participants’ worries were eased through continuing social support, creating positive ring norms, and role modeling from peers. Referring to participants’ engagement meetings conducted in the context of the ASPIRE intervention, Rudo recalls how encouraging they were: “When someone said, ‘I am using [the ring] and that all is well,’ the others will also do likewise saying, ‘Ah that one is saying that she is using! Let me also do the same.’ She will continue using it without looking back” (IDI, Zimbabwe).

Nonadherence

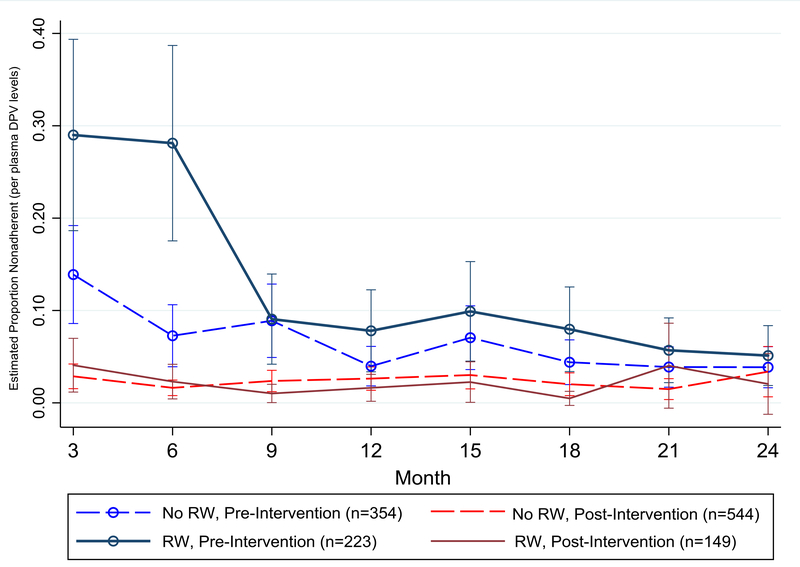

Figure 2 displays the estimated proportion of women using a dapivirine ring who were nonadherent, by baseline ring worry and enrollment pre/post ASPIRE intervention (n=1270). Women enrolled before the start of the intervention had higher odds of nonadherence compared to those enrolled after the start (p=0.004). Baseline general worry about using the ring influenced odds of nonadherence only for women enrolled before the intervention. Among those who were enrolled preintervention, 29% of women with baseline ring worries were nonadherent at month 3 (95% CI: 19%, 39%) compared to 14% without ring worries (95% CI: 9%, 19%; p=0.005). The difference remained significant at month 6, but by the month 9 visit, there was no difference in nonadherence by baseline ring worry for those enrolled preintervention (p=0.95). There was no difference in nonadherence by baseline ring worry for those enrolled postintervention (p=0.40). We found a similar trajectory for nonadherence by baseline specific worry and enrollment preintervention (data not shown).

Figure 2.

The estimated proportion of women who were nonadherent based on plasma dapivirine (DPV) levels, by baseline general ring worry (RW) and enrollment pre-/post adherence monitoring intervention among women using a dapivirine ring in the ASPIRE trial (N=1,270). Estimates are from mixed-effect logistic regression model adjusting for age group, country, and time in study.

Reflecting on their experiences, participants discussed in interviews how the ring—a new HIV prevention technology with an unconventional mode of administration—initially elicited a range of concerns, and for some, fearful reactions which led to poor adherence. Masauso said, “When I was given the first ring, I was not at peace; I indeed removed and placed it somewhere” (IDI, Malawi). Another participant mentioned she was “afraid” since this “was the first time [for the ring] to be inserted in the [her] body!” (IDI, Malawi). Pinky who said that her first month was “hectic” and “the most difficult one,” explained:

At the beginning I was scared. The first day after inserting it [the ring], when I bathed I removed it and put it inside the plastic bag. I asked myself, ‘Why did I remove it?’ I put it back. You see? To be honest at the beginning I removed it. But as time went by when I was talking to other people, they said, ‘This thing is just seated there; you won’t feel it.’ (FGD, South Africa)

The influence of the intervention on both adherence and ring worry was apparent in the qualitative data. Some fears were mentioned as initially fueled by stories and rumors circulating among the participants (e.g., ring causing cancer, infertility, or bewitching men); however, as a result of participants’ engagement activities, these stories were transformed into ones of empowerment, success, and solidarity, which helped dispel misconceptions and promoted ring adherence:

Most of us, when we were new in the study, we were afraid that it may cause cancer, or that the ring may drop, all this was because of fear. However, we were able to discuss this during our adherence meeting and we were able to encourage each other (Florence, IDI, Malawi).With the ASPIRE intervention, when receiving feedback on estimates of their site’s aggregate level of biological adherence relative to other ASPIRE sites, striving for success and contributing toward a common cause encouraged participants into a “virtuous cycle” to improve adherence:

Those meetings are really of benefit, because while being involved in the study, there also a lot of challenges affecting our site. Our doctors motivate us, and this has resulted in us using the ring appropriately. Some participants were not vigilant and were not using the ring as instructed. Because of this, our site performed poorly on ring use, while other sites were way ahead of us. Then we were called for the meeting and we were asked about our performance. It really affected us; we wanted to compete with others on the first position. I can now see that we are trying hard to wear the ring so that our study should progress well (Chimwala, IDI, Malawi).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated 1) what worries ASPIRE participants reported about daily ring use, 2) factors that influenced the emergence and decline of these ring worries, and 3) the effect of ring worries on nonadherence during the trial. Worries were common at baseline but mostly resolved over time, and they did not significantly differ by age. Baseline worries were associated with nonadherence, but only for those enrolled prior to the ASPIRE intervention; they affected adherence for the first 6 months in the trial but not thereafter. The qualitative findings corroborated our quantitative analyses, indicating initial anxieties about the ring and a range of worries related mostly to sex, use attributes, and health. These subsided with practice, self-experimentation, and the ASPIRE intervention, which included education and counseling by staff and facilitated discussion and social support from peer participants. These findings have practical importance as they provide evidence that women became more comfortable (had fewer worries) with the ring over time; they inform early counseling and support strategies; and finally, they highlight important aspects of messaging for ring introduction in the future.

The novelty of the ring and lack of familiarity with vaginal insertion created initial apprehension among ASPIRE participants. Women sought various processes to alleviate these worries. Worries related to correct placement and use attributes were mostly alleviated with practice. Experience brought a sense of normality, comfort, and bodily ‘fit” with wearing the device, as reported in another ring study.13 Sex- and health-related worries were both aggravated (e.g. spread of rumors23) and eased (e.g. normalizing challenges) by social interaction with fellow participants and were also addressed with education by staff and self-experimentation. Self-experimentation with the ring highlights the importance of a corporeal experience for ring fit, suggesting that the learning phase of ring use should extend beyond simple insertion and removal practice at the clinic, as previously advised for other vaginal products.24,25 Indeed, wearing the ring in daily life (e.g., through daily activities and bodily functions) and in different situations, including sex, may be paramount for adoption.13,26 Early stage counseling and adherence support should recognize that with a new technology there will be an appraisal period with psychological, emotional, and behavioral adjustments. As we showed, during this appraisal phase when worries ran high, women were most vulnerable to misconceptions, negative social influences, and mis-execution of ring use. Importantly, for ring adherence support and dispelling worries early on, social interventions may be more impactful than 1-on-1 approaches. In ASPIRE, ring worries were high and affected adherence only preintervention (when only individual adherence counseling was conducted); worries and nonadherence decreased postintervention. Finally, our findings suggest that when preparing for ring introduction and messaging, ring adoption should not be expected to be “love at first sight” and will require knowledge, time, and practice14 and the support of key influencers such as ring-educated clinic staff and peers, particularly during the appraisal period. A study of menstrual cup adoption—another vaginally inserted product, for example—showed that the peer effect on technology adoption was most pronounced early on, and that it impacted women’s success at usage.27

In contrast to previous effectiveness trials,8,28in ASPIRE, the intervention which had important social components, appeared to have counteracted product-related fears and research mistrust and elicited a communal goal for study success.12,29 Beyond education and counseling, the intervention normalized concerns by addressing them in a supportive social environment and stimulated peer role modeling. Furthermore, adherence may have been incentivized through promoting team work, altruism, and friendly competition for social reward.13

The study’s main limitation is that participants were not randomly assigned to the ASPIRE intervention and causality cannot be determined. Also, it is not possible to untangle which component(s) of the adherence monitoring and participant engagement activities were most important to address fears, promote adherence, or mitigate the effect of worries on adherence. Experimental designs in the context of future implementation research should help tease these out. Differences in ring worries by country could not be explained, in part because trial initiation was not consistent across sites; although the qualitative findings suggest more concerns with vaginal insertion of the device in South Africa. Nevertheless, future multisite, open-label trials and implementation research may help address the question of country differences in concerns about and willingness to use this new technology.30

To conclude, we found that worries may be a deterrent to ring adherence especially in the first few months of use. Intervening early and promoting hands-on practice of the ring during the appraisal period may be decisive. Positive social influence from supportive peers and clinicians may be critical to promote successful adoption and correct use of the ring.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding

The MTN-020/ASPIRE study was designed and implemented by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN). The MTN is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615, UM1AI106707), with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the US National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The vaginal rings used in this study were supplied by the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM).

Presented (in part) previously at: HIV Research For Prevention (R4P), Chicago, October 2016

Study Team Leadership: Jared Baeten, University of Washington (Protocol Chair); Thesla Palanee-Phillips, Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute (Protocol Co-chair); Elizabeth Brown, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Protocol Statistician); Lydia Soto-Torres, US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Medical Officer); Katie Schwartz, FHI 360 (Clinical Research Manager)

Study sites and site Investigators of Record: Malawi, Blantyre site (Johns Hopkins University, Queen Elizabeth Hospital): Bonus Makanani; Malawi, Lilongwe site (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill): Francis Martinson, South Africa, Cape Town site (University of Cape Town): Linda-Gail Bekker; South Africa, Durban – Botha’s Hill, Chatsworth, Isipingo, Tongaat, Umkomaas, Verulam sites (South African Medical Research Council): Vaneshree Govender, Samantha Siva, Zakir Gaffoor, Logashvari Naidoo, Arendevi Pather, and Nitesha Jeenarain; South Africa, Durban, eThekwini site (Center for the AIDS Programme for Research in South Africa): Gonasagrie Nair, South Africa, Johannesburg site (Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, University of the Witwatersrand ): Thesla Palanee-Phillips, Uganda, Kampala site (John Hopkins University, Makerere University): Flavia Matovu Kiweewa, Zimbabwe, Chitungwiza, Seke South and Zengeza sites (University of Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences Clinical Trials Research Centre): Nyaradzo Mgodi, Zimbabwe, Harare, Spilhaus site (University of Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences Clinical Trials Research Centre): Felix Mhlanga, Data management was provided by The Statistical Center for HIV/AIDS Research & Prevention (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) and site laboratory oversight was provided by the Microbicide Trials Network Laboratory Center (Pittsburgh, PA).

Footnotes

None of the authors declare any conflicts of Interest.

We used the definition of “worry” from www.merriam-webster.com—”to feel or experience concern or anxiety”—to frame this feeling.

A list of the members of the Microbicide Trials Network 020-A Study to Prevent Infection with a Ring for Extended Use (MTN-020-ASPIRE) Study Team is provided in the Acknowledgements section.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS. Women and girls and HIV. UNAIDS, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 07 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.AVAC. Microbicide Trial Summary Table. 2018; https://www.avac.org/trial-summary-table/microbicides. Accessed 2018.

- 3.Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, et al. Use of a vaginal ring containing Dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention in women. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2121–2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nel A, van Niekerk N, Kapiga S, et al. Safety and efficacy of a Dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention in women. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2133–2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Mgodi NM, et al. High Uptake and Reduced HIV-1 Incidence in an Open-Label Trail of the Dapivirine Ring. CROI; 2018; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nel A, Van Niekerk N, Van Baelen B, Rosenberg Z. HIV incidence and adherence in DREAM: an open-label trial of Dapivirine vaginal ring. CROI; March 4–7, 2018, 2018; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown E Residual dapivirine ring levels indicate higher adherence to vaginal ring is associated with HIV-1 protection AIDS 2016; 2016; Durban, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, et al. Women’s experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: the VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pillay D, Chersich MF, Morroni C, et al. User perspectives on Implanon NXT in South Africa: a survey of 12 public-sector facilities. S Afr Med J. 2017;107:815–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Straten A, Montgomery ET, Cheng H, et al. High acceptability of a vaginal ring intended as a microbicide delivery method for HIV prevention in African women. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1775–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nel A, Bekker L-G, Bukusi E, et al. Safety, acceptability and adherence of Dapivirine vaginal ring in a microbicide clinical trial conducted in multiple countries in sub-Saharan Africa. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0147743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Chitukuta M, et al. Acceptability and use of a dapivirine vaginal ring in a phase III trial. AIDS. 2017;31(8):1159–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLellan-Lemal E, Ondeng’e K, Gust DA, et al. Contraceptive vaginal ring experiences among women and men in Kisumu, Kenya: A qualitative study. Frontiers in women’s health. 2017;2(1): 10.15761/FWH.1000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minnis AM, Roberts ST, Agot K, et al. Young women’s ratings of three placebo multipurpose prevention technologies for HIV and pregnancy prevention in a randomized, cross-over study in Kenya and South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laborde ND, Pleasants E, Reddy K, et al. Impact of the Dapivirine vaginal ring on sexual experiences and intimate partnerships of women in an HIV prevention clinical trial: managing ring detection and hot sex. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(2):437–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Straten A, Shapley-Quinn MK, Reddy K, et al. Favoring “peace of mind”: a qualitative study of african women’s HIV prevention product formulation preferences from the MTN-020/ASPIRE Trial. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(7):305–314. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Husnik MJ, Brown ER, Marzinke M, et al. Implementation of a novel adherence monitoring strategy in a phase III, blinded, placebo-controlled, HIV-1 prevention clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76(3):330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz K, Ndase P, Torjesen K, et al. Supporting participant adherence through Structured Engagement Activities in the MTN-020 (ASPIRE) Trial. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30(S1):A80–A80. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Cheng H, et al. Vaginal ring adherence in sub-Saharan Africa: expulsion, removal, and perfect use. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1787–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Straten A, Panther L, Laborde N, et al. Adherence and acceptability of a multidrug vaginal ring for HIV prevention in a phase I study in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(11):2644–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nel A, Haazen W, Nuttall J, Romano J, Rosenberg Z, van Niekerk N. A safety and pharmacokinetic trial assessing delivery of dapivirine from a vaginal ring in healthy women. AIDS. 2014;28(10):1479–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp, LLC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chitukuta M, Duby Z, Katz A, et al. Negative rumours about a vaginal ring for HIV-1 prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. Cult Health Sex. 2019:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beksinska M, Smit J, Joanis C, Hart C. Practice makes perfect: reduction in female condom failures and user problems with short-term experience in a randomized trial. Contraception. 2012;86(2):127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery ET, Blanchard K, Cheng H, et al. Diaphragm and lubricant gel acceptance, skills and patterns of use among women in an effectiveness trial in Southern Africa. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2009;14(6):410–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epstein LB, Sokal-Gutierrez K, Ivey SL, Raine T, Auerswald C. Adolescent experiences with the vaginal ring. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(1):64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oster E, Thornton R. Determinants of technology adoption: peer effects in menstrual cup take-up. J Eur Econ Assoc. 2012;10(6):1263–1293. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corneli A, Perry B, McKenna K, et al. Participants’ explanations for nonadherence in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(4):452–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amico KR, Wallace M, Bekker L-G, et al. Experiences with HPTN 067/ADAPT study-provided open-label PrEP among women in Cape Town: facilitators and barriers within a mutuality framework. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1361–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Microbicide Trials Network. About the REACH Study (MTN-034/IPM 045). 2017; http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/news/about-reach-study-mtn-034ipm-045. Accessed 21 May 2018.