Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION TO SURFACE-INDUCED DISSOCIATION

Many mass spectrometry applications make use of tandem mass spectrometry, where two stages of m/z analysis are coupled. In between the two stages of m/z analysis, an activation or reaction step is carried out to cause either structurally-informative fragmentation or structurally-characteristic reaction of the precursor ion of interest. This review focuses on the use of collisions with a surface (surface-induced dissociation, SID) as the activation method in tandem mass spectrometry. Because this is the first review of SID in this Anal. Chem. Series, an emphasis on SID papers published over the past four years, rather than only two, years is included. SID is described and compared with other activation methods. The major application focused on in this review is the structural characterization of native protein complexes, complexes kinetically trapped that retain native-like solution structures upon transfer to the gas-phase and throughout the relatively short timeframe of the mass spectrometry experiment. Other SID applications currently under investigation are also briefly described. Pioneering work on SID has been summarized previously and thus will not be discussed in detail here.1–4

Surface-induced dissociation was developed in the laboratory of Graham Cooks, with many studies later carried out in the labs of Cooks, Russell, Wysocki, Whetten, Beck, Futrell, Laskin, Hanley, Gaskell, and Turecek, among others.5–14 SID has been used for fragmentation of many different types of ions. Initially, SID was used to fragment lower mass, singly-charged projectiles because the ionization methods and mass analyzers needed to form, transmit, and characterize high m/z, multiply-charged ions had not yet been developed to the point where high m/z ions could be conveniently studied. In the early days of SID, it was determined that self-assembled monolayer surfaces (SAMs) of CF3(CF2)10CH2CH2S- on gold serve as effective collision targets for surface-induced dissociation (SID) in a tandem mass spectrometer.7,15 The use of these easy-to-prepare surfaces has persisted, although several other surface types have been utilized.16–24 These SAMs provide a large effective mass for collision of projectile ions, the fluorocarbon chains are relatively rigid so that they don’t severely dampen the energy of the colliding projectile, and the fluorocarbon resists facile electron transfer to the incoming ions. Surface targets, in contrast to the typical gaseous targets such as Ar that are used for the more common activation method collision-induced dissociation (CID), have proven to be exceptionally useful for the characterization of protein complex quaternary structure. The ability of SID to produce subcomplexes that remain compact and provide connectivity information of the original native complex structure is currently unmatched by other dissociation techniques. While each dissociation method can provide unique information that is complementary to other gas- and solution-phase techniques, no singular mass spectrometry method currently exists in which the entire protein complex structure – including topology, relative interfacial strengths, and ligand binding details – can be determined and thus, complementary techniques are appealing to gain a more thorough understanding of structural details.

Native or native-like protein complexes are produced by electrospray or nano-electrospray ionization in electrolytes such as ammonium acetate at approximately physiological ionic strength and pH. SID of these multiply-charged protein complexes generally produces compact, native-like fragments that retain a symmetrically-distributed proportion of charge.25,26 This results in unique, easy-to-distinguish spectra in which the subcomplex products center around a narrower m/z distribution when compared with other tandem MS activation methods. Additionally, SID products and the energy at which they begin to form are typically reflective of relative interfacial strengths and topology of the protein complex.26 For example, a D2-symmetric homo-tetramer (dimer of dimers) is anticipated to dissociate into dimers at lower SID energies, with the dimers further dissociating into monomers at higher SID energies.26 In contrast, a C4-symmetric tetramer (ring with equal protein-protein interactions between each subunit) will dissociate into monomer, dimer, and trimer at low SID energy.25 These characteristic dissociation patterns help to assess the quaternary structure of the intact protein complex. These two characteristics in particular – symmetric charge partitioning and dissociation dependent on interfacial strengths of protein complexes – are unique to SID and make an SID spectrum distinctive from that obtained by other dissociation techniques.

COMPARISON OF SID WITH OTHER DISSOCIATION METHODS

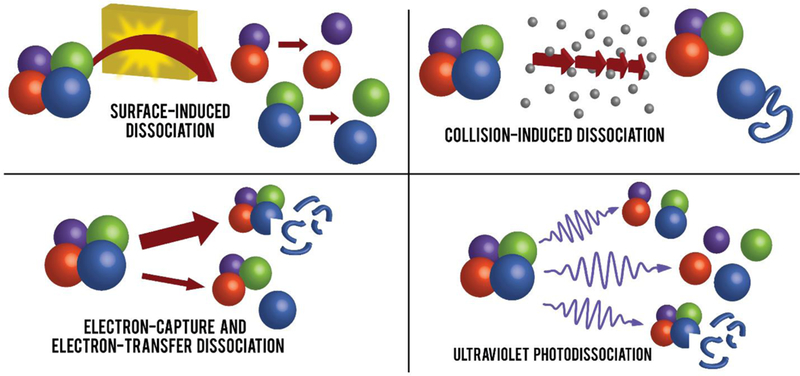

Herein we describe alternative dissociation methods commonly employed within mass spectrometry with an emphasis on the outcomes of probing native protein complexes using these techniques. The various techniques described, in addition to SID, are shown as a cartoon in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cartoon illustration representing the major products of various common dissociation methods in the study of protein complexes. Small blue fragments correspond to covalent cleavage of an individual protein chain.

Collision-induced dissociation

Collision-induced dissociation (CID, or collisionally-activated dissociation (CAD)) is a technique incorporated in essentially every commercial tandem mass spectrometer due to its robust nature and simple integration and operation within an instrument.27 CID is accomplished by accelerating precursor ions into a neutral background gas, resulting in multiple, low-energy collisions. During these collisions, a portion of the kinetic energy of the ion is converted into vibrational internal energy, resulting in a stepwise buildup of internal energy within the precursor ion.28 As the internal energy builds up, dissociation of the ion can occur. Because it typically takes many small steps of energy conversion in order to result in dissociation, CID is often referred to as a “slow heating” process, and the products are often reflective of the lowest energy dissociation pathways (often rearrangements) as illustrated in Figure 2.25 CID has found broad utility in the sequencing of peptides and proteins in proteomics applications or in fragmentation of small molecules in metabolomics. Covalent fragments that dominate in CID activation of peptides are typically b- and y-type ions, which occur from fragmentation of the peptide bond, but other fragment ion types are also produced including internal fragment ions, a-type ions, immonium ions, and b and y ions that have lost NH3 or H2O. CID is used in the majority of routine proteomics experiments in order to identify proteins via tandem mass spectrometry. Because CID generally fragments via the lowest energy pathways, CID sometimes results in labile modifications being lost in the fragmentation process, particularly phosphorylation.29–31

Figure 2.

Simplified representation of the pathways a protein complex may take when undergoing CID (left) or SID (right). CID involves multiple low-energy collisions (top left) that generally result in dissociation via the lowest energy pathway (bottom left). SID involves a single-step, high energy deposition via collision with a surface (top right) and typically results in dissociation via alternative dissociation pathways and dissociation products form that are often compact and reflective of the native structure (bottom right). Reproduced from Zhou, M.; Wysocki, V.H., Surface induced dissociation: Dissecting noncovalent protein complexes in the gas-phase. Acc. Chem. Res., 47(4), 1010–1018. Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

The dominance of CID and its characteristic fragmentation patterns make it the standard to which all other dissociation techniques are compared. With the increasing popularity of native mass spectrometry, it has been demonstrated that CID of protein complexes typically yields reproducible dissociation in which a single subunit is ejected from the complex,27,32,33 providing information about the stoichiometry and some limited information regarding connectivity of the protein complex.34 This ejected subunit typically holds a disproportionately large amount of charge which implies unfolding, a hypothesis confirmed through both ion mobility studies and MD simulations.27,35–38 There are a few published exceptions, for example, 2-keto-3-deoxyarabinonate dehydratase, in which the dimer-of-dimers topology is reflected in the dissociation of the complex via CID into dimers.39 Although much is known regarding CID of protein complexes, there is still much to learn such as the nature of charge migration during the unfolding process and whether this occurs because of unfolding or is the cause of it.27,36,40 Additionally, the unfolding/restructuring of the complex that occurs before monomer subunit ejection is still not fully understood.27,36

The unfolding associated with CID has been transformed into an area of research called collision-induced unfolding (CIU) that takes advantage of this characteristic unfolding and couples it with ion mobility to provide insight into the structure of native ions within the gas-phase. Recent work has helped to establish CIU as a potential analytical fingerprinting technique that is gaining traction in the analysis of the structural stability of proteins, protein complexes, protein-ligand complexes, and antibodies.41–43 CIU in combination with CID has also been utilized to investigate the effect of different salts on the stability of proteins and protein complexes in the gas-phase.44 Anions in the Hofmeister series were investigated for perturbations of protein complex gas-phase stability. Han et al. demonstrated that significant differences exist between anions that result in increased solution-phase stability and those that result in increased gas-phase stability.44 Using both CID and CIU it was shown that anions that bind with high affinity, but dissociate readily from the protein complexes in the gas-phase, result in increased stabilization of the protein complexes in the gas-phase. Furthermore, they demonstrated that anion-complex interactions are involved in both the local protein structure and protein-protein interactions.44

Despite its popularity, and although CID can provide a wealth of information in certain areas of research, it is not well suited for every tandem mass spectrometry task. The stepwise energy deposition mechanism of CID may lead to “dead end” fragmentation pathways for some ions. Because low energy products are favored, rearrangement pathways such as water and ammonia loss tend to be prevalent CID products of peptides and proteins, and are typically structurally uninformative.29,30 When working with protein complexes, CID often requires additional experiments such as in-solution disruption to generate subunit mapping information.45,46 Additionally, although unfolding via CID can be useful in probing stability through CIU analysis, the unfolding/restructuring pathway is sometimes unwanted in the study of native-like proteins and protein complexes as it can lead to a loss in information about tertiary and quaternary structure.

The effect of precursor charge in CID vs. SID

A noteworthy factor when comparing CID and SID of protein complexes is the effect of precursor ion charge on the observed products. The collision cross sections, CCS, of a wide variety of intact biomolecular complexes as determined by IM under native-like conditions, agree well with theoretical CCS calculations based on structural models.45 CCS values of subcomplexes produced via dissociation of the complex in the gas-phase can also be measured by IM and compared with subcomplex structures “clipped” from X-ray or NMR structures.47 When a complex is dissociated by CID, theoretical and measured CCS values of the subcomplexes deviate significantly, with the highly-charged, ejected monomer having much higher CCS than expected for a monomer with tertiary structure intact.48,49 This is unsurprising as many IM studies have shown correlations between unfolded, extended protein structure and disproportionately high charge density.50,51 It has also been observed for some large multimeric complexes that higher charge density can cause compaction rather than unfolding – a different structural rearrangement but an aberration from the native structure nonetheless.52 Because of concerns over this correlation, one practice is the use of charge-reducing reagents to produce more “native-like” ions for probing the quaternary structure of protein complexes.49,53,54

While ammonium acetate is the most commonly used volatile salt in native mass spectrometry, charge-reducing reagents allow for an overall lower average charge state distribution of the generated ions and reportedly increase the gas-phase stability and preserve intact protein complex and antibody structures.48,49,55 Such charge-reducing agents function based on their relatively higher gas-phase basicity when compared with ammonium acetate.54,56,57 Electrolyte additives such as triethylammonium acetate (TEAA) or electrolytes that can be used instead of ammonium acetate such as ethylenediamine diacetate (EDDA) promote lower-charged protein ions when compared with ammonium acetate because the more basic ionic species will compete for charges with the basic sites of the protein, essentially removing charge from the protein.54,56,57

Use of these reagents in MS/MS experiments has shown that lower-charged precursors display suppressed unfolding and dissociation upon CID activation when compared with their higher-charged counterparts.36,49 Additionally, the monomers produced by CID of charge-reduced precursors show a preference for lower-charge and compact conformations.49 While not entirely impervious to unfolding, some of the lowest precursor charge states do result in compact monomer production upon CID. Supercharging of the protein complex precursor ion, on the other hand, results in dissociation into subunits upon lower onset voltage with both SID and CID. SID of supercharged precursors typically favors dissociation of protein-protein interactions over unfolding, resulting in similar spectra when compared with “normal”-charged precursors.58 Overall, the charge of the precursor shows a significant effect on the CID dissociation pattern of protein complexes.

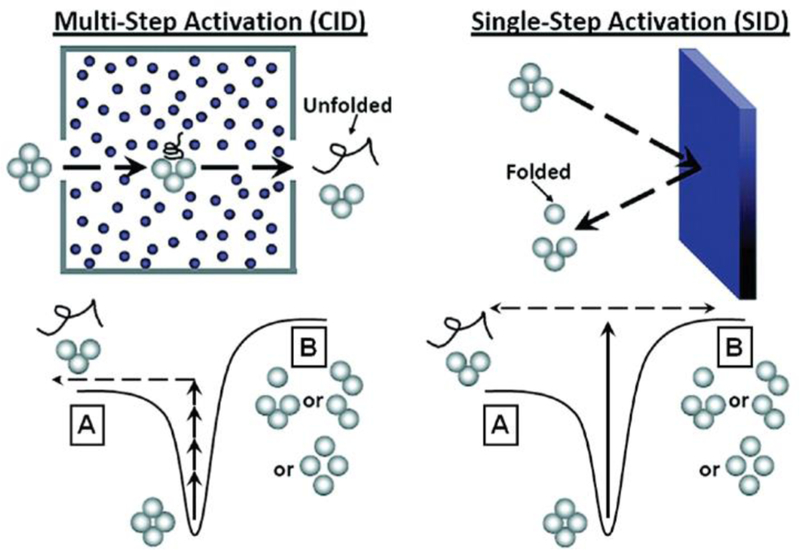

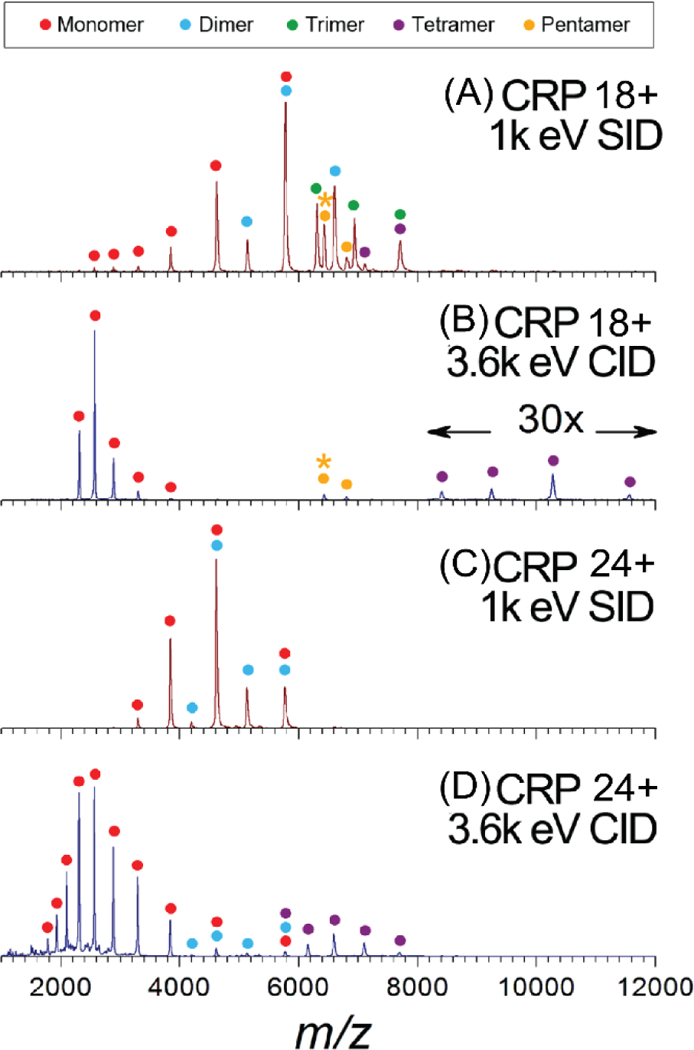

In recent years, the Wysocki group has investigated the effect of reduced precursor charge on SID products. One example is the pentameric C-reactive protein (CRP). Under “normal”-charge conditions when sprayed from ammonium acetate solution, a dominant 24+ pentamer is observed. With the addition of the charge-reducing reagent triethylammonium acetate (TEAA), the dominant precursor charge state becomes 18+. It was observed that low-charged, compact monomers, dimers, trimers, and tetramers were all observed upon SID of the 18+ precursor whereas only low-charged, compact monomers and dimers were produced upon SID of the 24+ precursor (Figure 3A and C).58 All four oligomeric products would be expected for dissociation of a cyclic pentamer (cleave any two interfaces to yield products), so the dissociation of the lower charge state precursor is more predictive of the complex’s structure. All subcomplexes produced from SID of either charge state precursor maintain compact conformations, so the difference in fragmentation patterns for lower and higher charge state precursor suggests better retention and preservation of subunit interactions within the pentamer, or less secondary fragmentation under charge-reducing conditions.58 In a side-by-side comparison, CID and IM of the same protein complex and charge states shows that the charge-reduced precursor unfolds to a lesser extent than the “normal”-charged precursor as has been shown by previous studies of the effect of charge reduction on CID products.58 For both charge states, however, monomer is still the dominant product from CID (Figure 3B and D), highlighting that CID cannot provide complete information on subunit connectivity in this case. Fragments generated via SID of charge-reduced precursor protein complex ions have been shown to be more reflective of the solved native structure for a number of protein complexes, such as concanavalin A, GroEL, trp RNA-binding attenuation protein (TRAP), and phosphorylase B.47,59–61 Overall, charge reduction continues to be a useful tool for providing fragments that can generate more information on the native protein complex structure.

Figure 3.

Spectra of C-reactive protein (CRP) pentamer undergoing SID (A and C) and CID (B and D). The top two spectra (A and B) utilize charge-reducing conditions to reduce the average charge state of the precursor ions relative to the spectra in (C and D) under “normal”-charge conditions. Under charge-reducing conditions, a greater variety of subcomplex products are formed via SID indicating that subunit interactions are maintained to greater extent under lowercharge. In both cases, CID results only in the production of monomer and tetramer. Reproduced from Zhou, M.; Dagan, S.; Wysocki, V.H., Impact of Charge State on Gas-Phase Behaviors of Noncovalent Protein Complexes in Collision Induced Dissociation and Surface Induced Dissociation. Analyst 2013, 138, 1353–1362.58 with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Photodissociation

Photodissociation occurs when gas-phase ions are energized and fragmented through the absorption of photons. There are many different photon sources available, typically in the form of lasers, each of which provide unique activation advantages. For example, using lasers with high energy photons, such as those in the UV range, can deposit a large amount of energy into the ion with a single photon. Using lasers with short pulses results in fast activation time frames due to the narrow pulse widths. We will focus on UV photodissociation (UVPD) as well as infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD) for the purpose of comparison with SID for native MS applications.

Recently, significant contributions to the field of native mass spectrometry have been made utilizing various photodissociation methods.62–67 The use of UV lasers provides access to excited electronic states which allows for new pathways of fragmentation to be accessible, in comparison to CID, SID, and ECD/ETD.68,69 UVPD at 193 nm has proven efficacy in the realm of top-down protein analysis as it provides diverse fragments ion types across the entire protein backbone in the form of a, b, c, x, y, z, and other covalent fragment ion types.62 The retention of labile PTMs by 193 nm UVPD is yet another advantage that has led to more thorough protein characterization from this technique.70–72

Other common UV wavelengths used in mass spectrometry include 157 nm and 266 nm. 7.9 eV photons (λ=157 nm) are absorbed by amide bonds, similarly to 6.4 eV photons (λ=193 nm) resulting in the excitation of proteins and peptides into higher electronic states, and gives an array of fragments similar to those from 193 nm activation.73 4.7 eV photons (λ=266 nm) are absorbed by aromatic side chains such as tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine and are also capable of homolytically cleaving disulfide bonds.74 UVPD at 266 nm has also been coupled with ion mobility (IM) on a Q-TOF instrument to provide the ability to not only mass-select a specific m/z ion by a quadrupole mass filter but also mobility-select the conformation of interest to then interrogate via laser irradiation.75 Using the unique mobility-selection capabilities to probe the UVPD fragmentation patterns of mass-coincident species, the Barran group has shown the utility in these orthogonal techniques for melittin and both the dimer and monomer of peptide gramicidin A, among other species.76 Additionally, recent commercialization of 213 nm UVPD (5.8 eV photons) within the Orbitrap™ Fusion Lumos instrument allows for this technology to reach even more users.

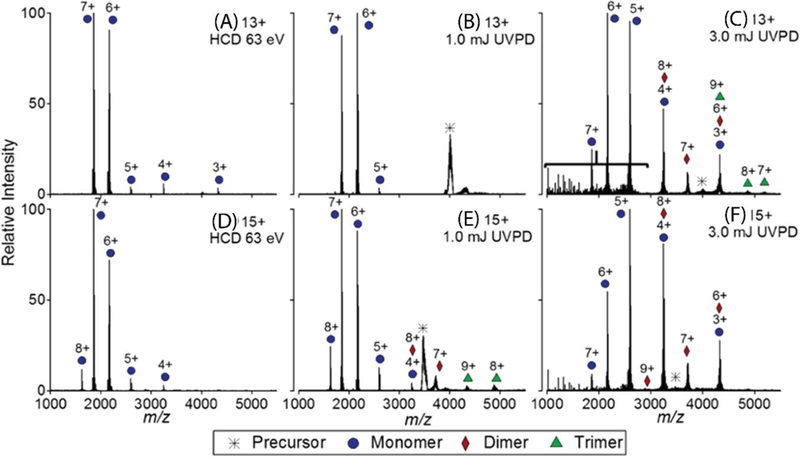

Aside from its utility in top-down studies of monomeric proteins, UVPD has also been investigated as an additional tool to be used for the analysis of protein complexes. Morrison and Brodbelt investigated the effect of 193 nm UVPD on tetrameric protein complexes and observed a strong dependency of the dissociation pathway based on the properties of the protein complex and the laser power. They studied three tetramers – streptavidin, transthyretin, and hemoglobin – all of which have a dimer-of-dimers topology. For streptavidin (Figure 4), UVPD using 2 mJ pulse energy began to produce dimers. With transthyretin, UVPD with 1.5 mJ pulse energy was the onset energy at which dimers were observed. However, in both cases, the onset energy of lower-charge monomer production was similar to that for dimer formation, suggesting a nonsequential formation of monomers in contrast to the sequential tetramer-dimer-monomer dissociation observed with SID. Additionally, UVPD of hemoglobin with 0.5–3 mJ pulse energy did not result in dissociation into dimers, but exclusively produced monomer subunits; the interfaces in hemoglobin are weaker than that of the other two complexes which might provide some explanation for this observation.77

Figure 4.

UVPD of streptavidin tetramer for precursor charge state 13+ (A, B, and C) and 15+ (D, E, and F). HCD of both 13+ and 15+ resulted in the ejection of highly-charged monomers (A and D). UVPD using 1 mJ pulse energy produced highly-charged monomers (B and E) but after increasing the pulse energy to 3 mJ, the products were more symmetrically charged partitioned (C and F). Reprinted with permission from Morrison, L.J.; Brodbelt, J.S. 193 nm Ultraviolet Photodissociation Mass Spectrometry of Tetrameric Protein Complexes Provides Insight into Quaternary and Secondary Protein Topology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 10849–10859. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Regardless of the complex properties, it was observed that UVPD products, although potentially indicative of interfacial strength, were not always symmetrically charge partitioned. At lower UVPD energy (1 mJ), subcomplexes did not all show symmetric charge partitioning, but at higher UVPD energy (3 mJ), the charge partitioning was more symmetric and therefore more similar to SID-like fragments. This suggests the need for a higher photon density in order to produce symmetrically-charged products from multiphoton absorption. Another interesting aspect of UVPD of protein complexes is the covalent fragmentation that occurs at higher UVPD energy. With 3 mJ pulses, subcomplex products are more symmetrically charge partitioned, but covalent fragmentation begins to occur as well. At higher pulse energy it has also been found that the lowcharge monomer products tracked with the formation of dimer products, suggesting that these two species have similar onset energy and thus, do not occur from sequential dissociation. Additionally, the decrease of highly-charged monomers coinciding with covalent fragmentation at high energy pulses suggests that the secondary dissociation of the highly-charged monomer subunits are responsible for the production of these covalent fragments. This quality could make 193 nm UVPD well suited for “complex-down” experiments in which the complex is broken down into subunits and then further into covalent fragments for secondary structure analysis.77 Other work has suggested that UVPD of protein complexes leads to an overall greater degree of symmetrically charge partitioned fragments than HCD but did show a dependence on the size and interfacial interactions of the complex.78

Recent work has shown the utility of 193 nm UVPD when working with ligand-protein complex systems. Irradiating such systems with 193 nm photons results in both backbone and non-covalent fragmentation which allows for insights into ligand binding sites as well as conformational changes that may occur as a result of ligand binding.79,80 Similar to SID, 193 nm UVPD of protein-ligand complexes typically retains the bound ligand, yielding fragments that are structurally informative of this binding location.79,80

IRMPD offers an interesting alternative to CID activation in that it allows for absorption of energy in a manner independent of charge state. Additionally, the laser source provides the capability to control both the activation intensity and timescale of activation. IRMPD has been utilized in the field of native mass spectrometry for both soluble and membrane protein complexes and has proven advantageous in the retention and further study of lipid binding to membrane proteins.66 In the study of membrane proteins, where the protein has to be solubilized in a mimic for the membrane environment such as a detergent micelle, activation must be used to liberate the complex from the detergent micelle. It has been shown that for a membrane protein complex that required 400 V of CID to liberate the complex (higher than typically allowed without instrument modification), IRMPD was capable of providing comparable cleanup while leaving the complex intact.66 Advantageously, increasing the radiation intensity does not result in signal loss.81,82 Interestingly, Mikhailov et al. were able to show that IR activation was gentle enough to retain membrane protein complex-lipid interactions between aquaporin Z (AqpZ) and phosphatidylglycerol (PG) lipids.66 Additionally, using both pulsed and continuous IR radiation, it was observed that although pulsed IRMPD produced symmetrically charge partitioned fragments in some scenarios, the majority of complexes dissociated through an asymmetrically charge partitioned pathway despite pulsed IRMPD occurring on a faster timescale than collisional cooling.66 Mapping IRMPD fragments of glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), a homohexamer, on a 3D structure showed that the covalent fragments are produced from the outer regions of the structure while leaving the trimer-trimer interface intact.67 This pattern of preferential IRMPD fragmentation on the outer region has been observed with other complexes and could prove useful in interrogating the quaternary structure of complexes.67

Electron-based dissociation techniques

Electron transfer and electron capture dissociation (ETD and ECD, respectively) are two additional activation methods used in analyzing peptides, proteins, and protein complex systems. ECD involves an interaction between low energy electrons and multiply-charged analyte cations in which the electrons are captured by the analyte cation. This exothermic reaction leads to subsequent charge reduction, energy transfer, and fragmentation.83,84 ECD is most commonly performed within FT-ICR instruments in which both the electrons and analyte cations are simultaneously trapped within the magnetic field. Performing such experiments in quadrupole ion traps proved to be challenging because rf voltages are not sufficient for trapping the thermal electrons.85 To combat this issue, ETD was developed as an alternative, but similar, technique more applicable for instruments that utilize rf trapping. In ETD, multiply-charged analyte cations interact with reagent radical anions resulting in the transfer of an electron.86,87 Similar to ECD, this process involves an exothermic reaction that causes backbone cleavage via migration of a hydrogen radical.88 Both ECD and ETD are believed to proceed via pathways that involve very little vibrational energy redistribution prior to backbone cleavage, which allows for the retention of labile modifications and for their use in characterizing hydrogen deuterium exchange products.89

Electron capture dissociation, perhaps best known for its success within the analysis of intact proteins, has also been utilized in the study of protein complexes. When undergoing ECD, complexes predominantly fragment into c/z-type ions while retaining some noncovalent interactions. This has allowed for mapping of protein-ligand contacts.90–92 ECD tends to preferentially cleave in backbone regions that are more flexible both within proteins and protein complexes, allowing for correlation between fragment efficiency via ECD and B-factors of the protein of interest.90,92 Because covalent fragmentation tends to dominate, information regarding the overall assembly of the macromolecule is usually lost. While backbone fragmentation is the most common outcome of ECD, at least one study has shown protein-protein interface dissociation being favored over covalent fragmentation.93

A major pitfall of electron-based methods is the observation of fewer fragments at lower charge, due to both a reduction of fragmentation efficiency and decreased fragment separation because of the more compact conformation of lower charge states. While this is known to be true for monomeric proteins and can be addressed in many ways when secondary structural information is desired, the correlation between charge and ECD fragmentation is even more drastic for native-like proteins exhibiting low charge states. Because lower-charge has been shown to be demonstrative of compact, folded, native-like structure, this is often a desirable regime in which to perform native mass spectrometry experiments, particularly within the study of larger protein complexes. However, this makes electron-based methods significantly more challenging to operate under such conditions. ETD operates in a similar manner, encountering many of the same challenges when working with native-like ions. In one example, a study that compared dissociation of insulin hexamer with both 193 nm UVPD and ETD reported that ETD mainly charge reduced the protein complex.80

To help combat the challenges facing ECD and ETD when studying native protein complexes (such as charge state dependency and electron capture efficiency), electron-induced dissociation (EID) utilizes >20 eV electrons to excite proteins to create electronically excited oxidized radical species and subsequently fragment the radical ions producing a, b, c, x, y, and z product ion types.94 By oxidizing the analyte cation during EID, alternative fragmentation pathways are accessed that allow for greater sequence coverage than other electron-based methods. While still in the early stages for utility in studying protein complexes, EID has been shown to provide complementary information to ECD such as providing interfacial fragments when ECD provided no fragmentation for the Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) enzyme.95

SID INSTRUMENTATION: DEVELOPMENTS AND APPLICATIONS OVER THE PAST FOUR YEARS

SID in ion mobility Q-TOFs

The combination of ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) and mass spectrometry is gaining importance due to its ability to separate and interrogate individual conformations of ions, to distinguish between different classes of molecules,96 and to resolve overlapping species—for example, different oligomeric states of proteins which are present at the same m/z ratio.97–99 In IM-MS, ions are separated based on their mass, charge, size, and shape. Ion mobility allows an ion’s rotationally-averaged collision cross section (CCS), which depends on its size and shape, to be determined. An ion’s CCS provides coarse-grained information on the conformations adopted in the gas-phase, and can be compared to solution coordinates obtained from molecular modelling, or structures solved by NMR, X-ray crystallography, and cryoEM.100–104 Ion mobility-mass spectrometry has been used in a wide range of applications, from peptide analysis,105–107 proteomics,108–110 metabolomics,111,112 small molecule and isomer identification,113–115 and native mass spectrometry. Within native MS and structural biology, ion mobility has been used to study the conformations of proteins and protein complexes,52,116,117 to study ligand binding,118 protein unfolding,42,119 and conformationally dynamic and intrinsically disordered proteins.120–122

Ion mobility has been coupled with many different types of mass analyzers, details of which can be found elsewhere.123 For many years, IM-MS experiments were limited to certain laboratories with home-built instruments.124–129 In 2006, Waters introduced the first commercially available integrated IM-MS instrument, the Synapt HDMS.130,131 In recent years, several additional ion mobility instruments have come onto the market including a linear drift tube Q-TOF instrument from Agilent, a field asymmetric ion mobility interface that can be coupled with Thermo instruments,132,133 and a trapped ion mobility Q-TOF instrument from Bruker. 134,135

To date, the Synapt G2 and G2-S instruments are the only commercial IM-MS instruments that have been modified to include SID, although home-built ion mobility instruments in investigator laboratories have previously been coupled with SID.136,137 The Wysocki group has previously reported that either the trap cell (the collision cell before the IM) or the transfer cell (the collision cell after the IM) can be truncated allowing incorporation of an SID device at either location, depending on the desired experiment.48,138 When SID is placed before the IM, CCS can be determined for the precursor and for the SID products, giving additional structural information on subcomplexes,26,48 whereas when SID is placed after the IM region, complexes can be separated based on their arrival times before dissociation and structural information can be obtained on different conformations of precursors and the conformationally-different precursors can each be fragmented independently.47,138

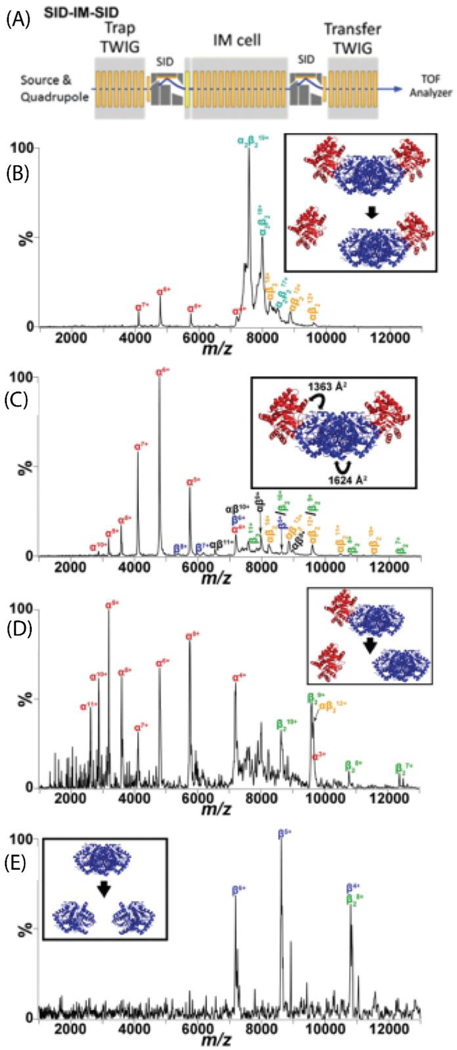

In 2015, Wysocki and coworkers demonstrated that two SID devices can be coupled, one before and one after the IM, to allow two stages of dissociation for protein complex ions, as shown in Figure 5A.139 In this proof-of-concept study, they demonstrated application of SID-IM-SID to study the disassembly of several standard protein complexes, which can provide information on the assembly of the complex. One of the model systems studied was tryptophan synthase (TS), a heterotetramer with a linear αββα subunit arrangement. The strength of each interface was analyzed using PISA,140 which calculates the interfacial area and number and nature of interactions from Protein Data Bank (PDB) files. PISA interfacial analysis for TS showed that the β/β interface is larger (1624 Å2) than the α/β interface (1363 Å2). In SID-IM-SID experiments, a single charge state of the intact complex (19+ TS) was selected by the quadrupole and collided with the surface in the first SID device. In the first stage of dissociation, at low energy, the weakest (smallest) interfaces are broken first, producing a ββα trimer (Figure 5B). By increasing the SID energy, additional interfaces can be broken producing ββ dimer in addition to the trimer (Figure 5C). The production of a ββ dimer as opposed to a βα dimer is consistent with the ββ interface being the strongest. As complex dissociation is favored over subunit unfolding in SID, further information on the disassembly and hence assembly can be obtained by performing a second stage of SID. In the first stage of SID (SID-IM), products are generated before the IM cell, separated by IM, and appear in separate TOF pulses. However, the fragments produced from the second stage of SID are formed after the IM region, and therefore appear in TOF pulses along with the products from which they are generated. By taking horizontal slices of the mobiligram plots, one can extract the MS/IM/MS spectra and successfully identify the fragments produced from the dissociation of the ββα trimer (Figure 5D) and ββ dimer individually (Figure 5E). Dissociation of the ββα trimer produced primarily ββ dimer and α monomer, which is again consistent with the solved structure of TS, and suggests SID-IM-SID is a useful tool to study disassembly pathways of protein complexes, which can provide information on the relative strengths of various interfaces within the protein complex. This approach was also applied to study a protein complex of unknown structure to aid in an MS-based structural determination.59

Figure 5.

(A) Traveling wave (T-wave) region of the modified Waters Synapt G2-S instrument showing the SID-IM-SID experiments. (B) Low energy SID-IM spectrum for 19+ tryptophan synthase hetero-tetramer (comprised of αββα subunits arranged in a linear fashion) at a collision energy of 570 eV. Inset is the dominant dissociation pathway illustrated with the crystal structure (PDB: 1WBJ). (C) High energy SID-IM spectrum for 19+ tryptophan synthase hetero-tetramer at a collision energy of 1330 eV. The interfaces and corresponding interfacial areas broken are highlighted in the inset. (D) SID-IM-SID of the 12+ αβ2-trimer and (E) 8+ β2-dimer, produced from SID-IM of the tetramer (collision energy of 1330 eV) with the second stage of SID performed at 2280 eV. Insets show the dissociation pathways. Reproduced from Quintyn, R.S., Harvey, S.H., Wysocki, V.H. Illustration of SID-IM-SID (surface-induced dissociation-ion mobility-SID) mass spectrometry: homo and hetero model protein complexes. Analyst, 2015 Oct 21;140(20):7012–9 with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

SID in FT-ICR mass spectrometers

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) mass spectrometers are capable of providing mass measurements with ultra-high resolution and high mass accuracy. These features make FT-ICR mass spectrometers suitable for a wide range of different applications including complex mixture analysis,141,142 analysis of petroleum products,143,144 and proteomics and metabolomics studies.145–148 In addition to the high mass accuracy and resolution, an advantage of FT-ICR instruments is that they can be used to perform multiple types of dissociation experiments,149 including collision-induced dissociation (CID), electron-transfer dissociation (ETD),150 electron-capture dissociation (ECD),151,152 electron ionization dissociation (EID),94 ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD),153–155 and infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRPMD).156 In addition, surface-induced dissociation has previously been implemented in FT-ICR instruments, particularly for the study of fundamentals of peptide fragmentation.10,24,157–161 SID has been applied to study the energetics and kinetics of gas-phase fragmentation within an ICR instrument.161 In this case, after ions are transferred into the ICR cell, they are directed towards, and collide against, a surface located at the rear trapping plate of the ICR cell. The acceleration of the ions for collision with the surface is controlled via the potential applied to the ICR cell electrodes. This device design allows SID spectra to be acquired as a function of the ion kinetic energy and the time between the ion-surface collision and the analysis. Furthermore, utilizing resonant ejection of fragment ions, the kinetics of fragment ion formation can be further probed by varying the delay time between the surface collision and ejection pulse. This approach has been used to better understand the gas-phase fragmentation of protonated peptides, odd-electron peptide ions, noncovalent ligand-peptide complexes, and ligated metal clusters. These applications are described briefly below.161

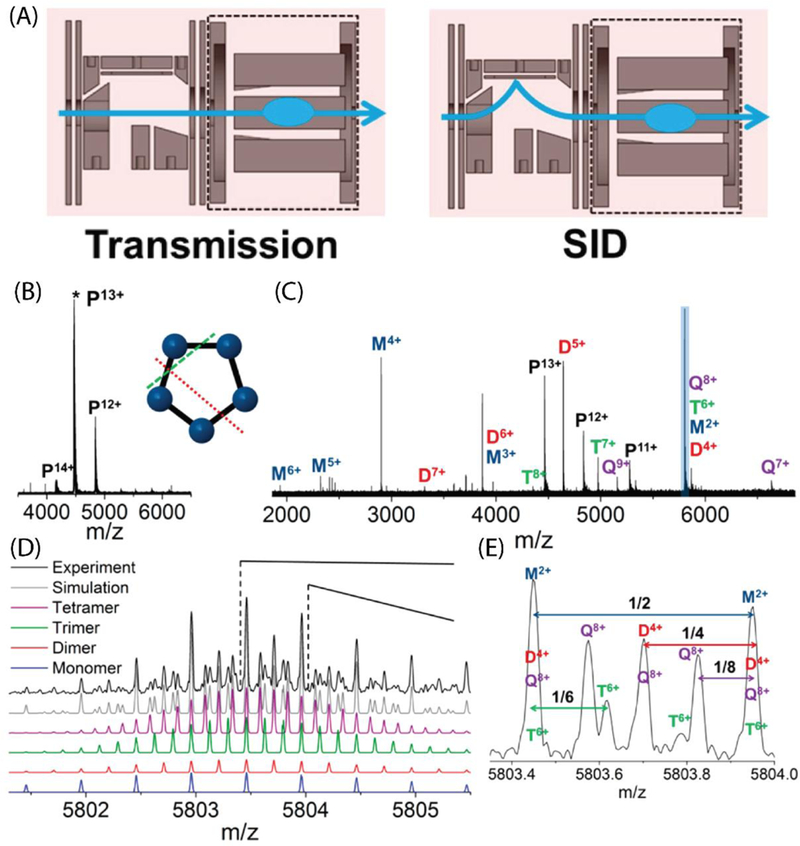

FT-ICR instruments have more recently also been used in native mass spectrometry and structural biology applications,162–164 including structural characterization,95,165,166 top-down dissociation,67,92 ligand binding,167,168 and membrane protein studies.169,170 In 2017, Yan et. al. presented the design and application of a surface-induced dissociation device to study multimeric protein complexes on a hybrid 15T FT-ICR mass spectrometer.171 In this design, an SID device with a trapping region was designed to fit in place of the standard CID cell in the Bruker SolariX XR cart. The SID device measures 2.75 cm long and is comprised of ten DC electrodes (Figure 6A). The SID device can be tuned either to allow ions to pass through without collision with the surface for intact mass measurements (Figure 6B), or the ion beam can be directed up towards the surface for dissociation studies (Figure 6C). After passing through the SID device, the ions enter a rectilinear quadrupole, with four asymptotic electrodes, that acts as the trapping region. This trapping region is enclosed to allow for higher pressure and is filled with argon for collisional cooling. Rf and dc voltages are applied to the rectilinear quadrupole for trapping ions and dc voltages are applied to the asymptotic electrodes for trapping and pulsing ions into the ICR cell. Yan et al. demonstrated the application of this device with several model protein complexes. As described above, SID is advantageous in such studies as it produces compact products, and products that are consistent with the known structure of the complex, cleaving the weakest interfaces in the complex first.26 Previous reports using Q-TOF instruments, however, have required the use of ion mobility to distinguish between overlapping oligomers, however the 15T FT-ICR was able to isotopically resolve overlapping oligomers (Figure 6D–E), as well as metal cations and ligands. The use of this device was further demonstrated by Zhou et. al.,172 for characterization of a heterooligomeric protein complex MnX from Bacillus sp. PL-12. Here the authors used SID to dissociate the 211 kDa complex into smaller subunits, which could then be isotopically resolved on the 15T FT-ICR although the high m/z products were not well-resolved. As SID dissociated the complex to produce compact subunits, copper bound to two different subunits was retained, which is important for a better understanding of structure and function for this complex, for which a high-resolution structure does not exist.172

Figure 6.

(A) SID device including SID region and rectilinear quadrupole with four asymptotic electrodes, schematic of transmission mode (left) and SID mode (right). (B) 4 μM CTB pentamer in 100 mM EDDA, acquired by averaging 30 scans with a 4.6 s transient. (C) SID of 13+ CTB pentamer at an SID acceleration voltage of 35 V. The spectrum was acquired by averaging 181 scans with a 9.2 s transient. (D) Zoomed-in region showing the peak highlighted in blue in (B). The experimental data are shown in black and the simulated isotopic distributions from different species are shown in purple (8+ tetramer), green (6+ trimer), red (4+ dimer), blue (2+monomer), and gray (sum of all species). (E) Further zoom in of m/z around 5803.7. Adapted with permission from Yan, J.; Zhou, M.; Gilbert, J. D. ; Wolff, J. J.; Somogyi, A.; Pedder, R. E.; Quintyn, R. S.; Morrison, L. J.; Easterling, M. L.; Paša-Tolić, L.; Wysocki , V. H. Surface-Induced Dissociation of Protein Complexes in a Hybrid Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometer, Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 895, Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

SID in Orbitrap platforms

Although the Orbitrap mass analyzer, introduced commercially in 2005, is one of the newest mass analyzers in mass spectrometry, its contributions have been widespread.173,174 The Orbitrap analyzer’s combination of resolution, speed, and sensitivity have become an indispensable tool in life science research, particularly in the fields of proteomics175–177 and metabolomics.178,179 However, the Orbitrap would not be such a powerful tool for proteomic analysis were it not for the many activation techniques such as beam type CID (HCD),30 electron transfer dissociation (ETD),180 infrared and ultraviolet photodissociation (IRMPD),181 (UVPD),62 electron capture dissociation (ECD),182 and combinations thereof (EThcD, AI-ETD)183,184 that have been implemented on the Orbitrap platform. Each activation method serves as an important, and often complementary, tool in bottom-up and top-down proteomics research.

Traditionally, the Orbitrap platform has been utilized for the analysis of digested or denatured proteins, with mass/charge ranges not exceeding 6,000 m/z. Recently however, Orbitrap instruments specifically suited for the study of large biomolecular complexes have been introduced to the market. The Orbitrap Exactive Plus EMR and Q-Exactive UHMR mass spectrometers have made it possible to study large viral particles, membrane protein complexes, and soluble protein complexes at high mass-resolution, with unrivaled sensitivity.185–188 The highresolution, high mass-accuracy, and (in the case of the experimental EMR instruments modified with a selection quadrupole, and the Q-Exactive UHMR) high m/z precursor selection capability have made it possible to study small ligand binding to large non-covalent complexes.189,190

With an increasing interest in studying the proteome at the non-covalent multi-protein complex level,191 additional activation methods are necessary to elucidate this higher-order structure. As discussed above, surface-induced dissociation has been shown to access dissociation pathways for non-covalent complexes that are often inaccessible by other activation methods, and it produces subcomplexes reflective of the overall native structure.3 With the Orbitrap increasingly being used for the study of large biomolecular complexes, it became clear that the combination of the high-resolution capabilities of the Orbitrap analyzer and structural information provided by SID may extend the current capabilities of native MS analysis.

VanAernum et al. recently implemented surface-induced dissociation on an Exactive Plus EMR Orbitrap platform that had previously been modified to include a selection quadrupole (manuscript in preparation). The SID device was designed to fit in place of the small transfer multipole between the quadrupole mass filter and the C-trap. This design choice means that the same SID design can be implemented in the newer Q-Exactive UHMR platform without any additional modifications. The performance of the SID-modified Exactive EMR was characterized by the dissociation of a range of previously studied non-covalent protein complexes. The dissociation patterns and subcomplexes produced from streptavidin tetramer (53 kDa) and glutamate dehydrogenase hexamer (334 kDa) showed the distinctive symmetric charge partitioning that was previously reported on time of flight instruments (and in the case of streptavidin tetramer, also on an ICR instrument), and reflected the dissociation pathways that would be expected based on the native structures.26,60,171 Furthermore, it was shown that subcomplexes that overlap in m/z space (e.g. 3+ monomer and 6+ dimer) could be distinguished with the high resolving power of the instrument by directly resolving the overlapping isotope distributions, or by differentiating the number of non-volatile salt adducts. The authors also demonstrated that the streptavidin-biotin interaction could remain intact through the SID process and the relative amount of biotin on streptavidin subcomplexes could be easily quantified with the high-resolution capabilities of the Orbitrap instrument.

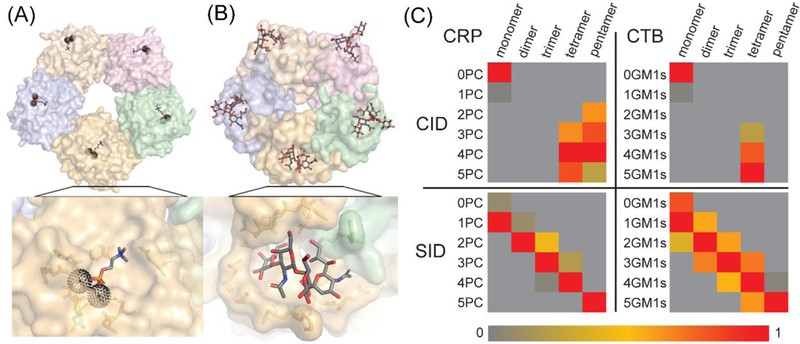

In another study, Busch et al. used SID on the Orbitrap EMR platform to localize the relative site of ligand binding on two model homopentameric protein complexes (Figure 7A–B).190 Using the high-resolution and high m/z precursor selection capability of the modified EMR instrument, they were able to dissociate C-reactive protein pentamer bound to 5 phosphocholine ligands and cholera toxin B pentamer bound to five GM1s ligands. Subjecting the holo pentamers to CID resulted in ligand loss and ligand migration with the produced subcomplexes providing limited to no information on the original location of ligand binding within the pentamer, as has already been observed previously.192 However, when the holo pentamers were subjected to SID, the ligands were retained on the resulting subcomplexes in a pattern that clearly indicated that CRP binds its ligand within each subunit, while CTB binds its ligands at the interface between subunits (Figure 7C). This result was made possible by the high-resolution provided by the Orbitrap instrument, and suggests that the combination of SID on the Orbitrap platform may be useful for the further study of ligand binding within large protein complexes.

Figure 7.

Surface presentations of (A) CRP (1B09) with PC ligands bound within each subunit and (B) CTB (2CHB) with GM1s ligands bound at the interface of two subunits. Ligands PC and GM1s are shown in stick presentation and calcium ions are shown as black spheres. Subunits are identical but individually colored for clarity. (C) Distribution of ligands on (sub)complexes generated from dissociation of CRP and CTB pentamers by CID and SID. Dissociation by CID results in ligand loss and ligand migration while dissociation by SID results in protein-ligand subcomplexes indicative of the ligand binding location in the original pentamer. Reprinted with permission from Busch, F.; VanAernum, Z.L.; Ju, Y.; Yan, J.; Gilbert, J.D.; Quintyn, R.S.; Bern, M.; Wysocki, V.H. Localization of protein complex bound ligands by surface-induced dissociation high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2018, Just accepted manuscript. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

STRUCTURAL BIOLOGY APPLICATIONS: SID COUPLED TO NATIVE MS

SID as tool to distinguish different gas-phase structures

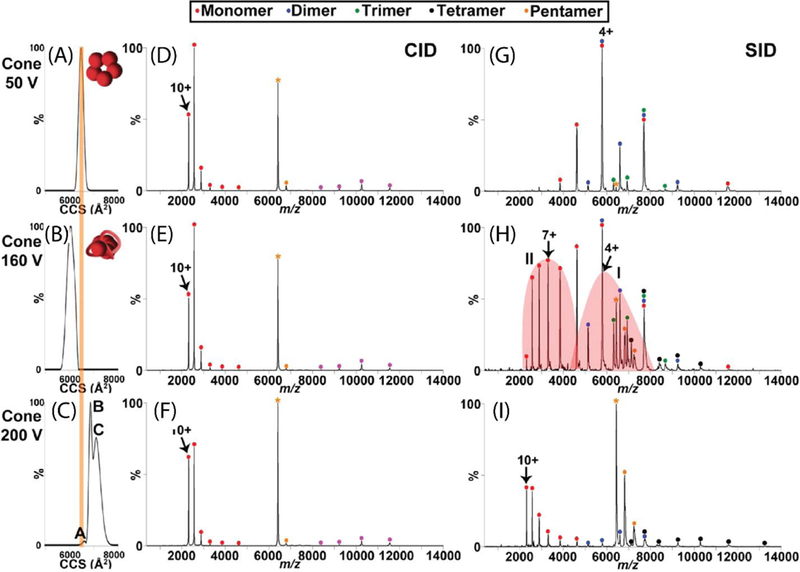

Changes in tandem MS fragmentation patterns and CCS values are commonly used to determine structural alterations that have occurred prior to or during mass spectrometric measurements of proteins and protein complexes. SID can be used as a tool to gain insight into structural alterations that might not be detectable otherwise. For instance, it is of particular importance to control the retention of structural integrity during analysis, while in some cases - if necessary - also activating the complex ions. The latter is important to reduce adduct formation, thereby allowing for improved apparent resolution in order to resolve different proteoforms and small-ligand adducts.193 While unfolding intermediates due to excessive in-source CID activation can sometimes be detected by IM, such intermediates might be too similar to provide distinguishable CCS values. SID of selected protein complex ions after in-source activation results in dissociation patterns reflective of structural change, making it a suitable tool to further monitor for structural integrity, irrespective of CCS value (Figure 8).47 Whereas native-like protein complexes dissociate into sub-complexes with symmetric charge state partitioning,3,60 excessive in-source activation results in restructuring as monitored by a change to more CID-like dissociation behavior (dissociation into highly-charged monomer and remaining tetramer) for SID of protein complex ions.47 The use of SID as a tool to determine subtle structural changes can further be used to monitor how the absence of solvent affects the structures of proteins and protein complexes over time. For this purpose, six model protein complexes were confined within the trap T-wave region of a modified Waters Synapt G2 over the range of 1–60 seconds.194 SID revealed similar dissociation patterns after trapping for up to 60 seconds, indicating that no significant structural changes occurred during this time that are sufficient to cause a change in dissociation pattern. Consistent SID fragmentation patterns for non-activated complexes trapped for different time as well as in-source activated complexes trapped for different time suggested that structural changes in these particular complexes are preserved in the gas-phase during a time span of up to 60 seconds.

Figure 8.

The effect of cone activation (collisional in-source activation) on CID and SID spectra of C-reactive protein (CRP). (A, B and C) demonstrate CCS plots of the +18 CRP pentamer at 50 V, 160 V, and 200 V cone activation, respectively. The theoretical CCS calculated from the crystal structure is overlaid as an orange line on these plots. CID and SID spectra are shown at these same cone activation energies in (D, E, and F) and (G, H, and I), respectively. While CID products show a highly-charged monomer and complementary tetramer regardless of the in-source activation, SID products reflect the structural rearrangement induced by this cone activation and suggest rearrangement to a more stable but less native conformation upon the highest energy of cone activation. Reprinted with permission from Quintyn, R. S.; Zhou, Z.; Yan, J.; Wysocki, V. H., Surface-induced dissociation mass spectra distinguish different structural forms of gas-phase multimeric protein complexes, Analytical Chemistry, 2015, 87, 11879–11886. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

SID as tool to determine different in-solution structures

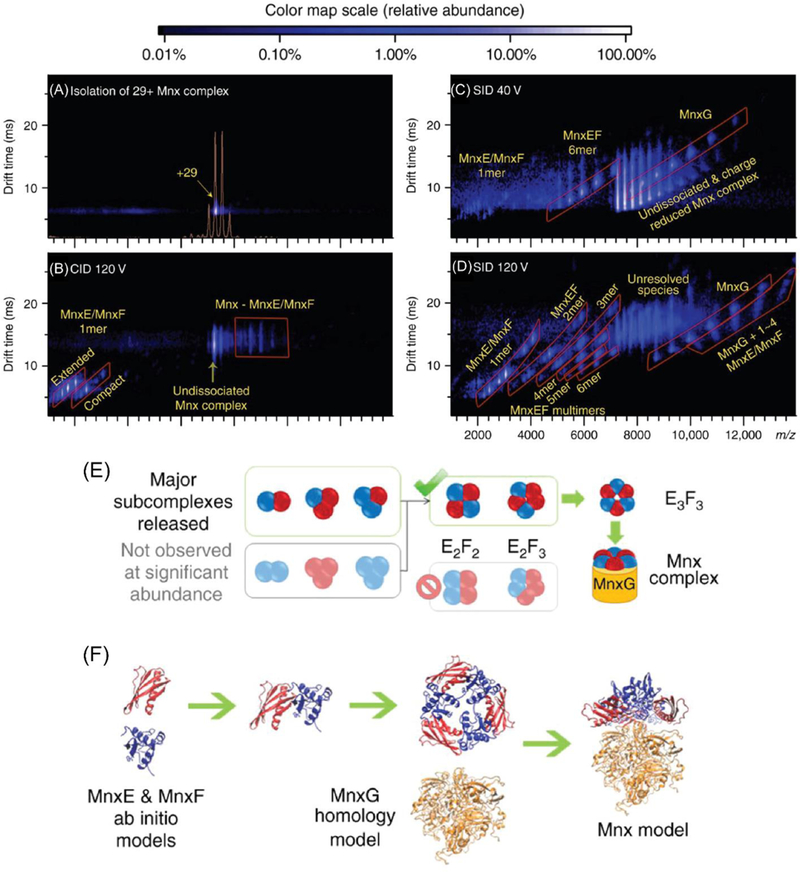

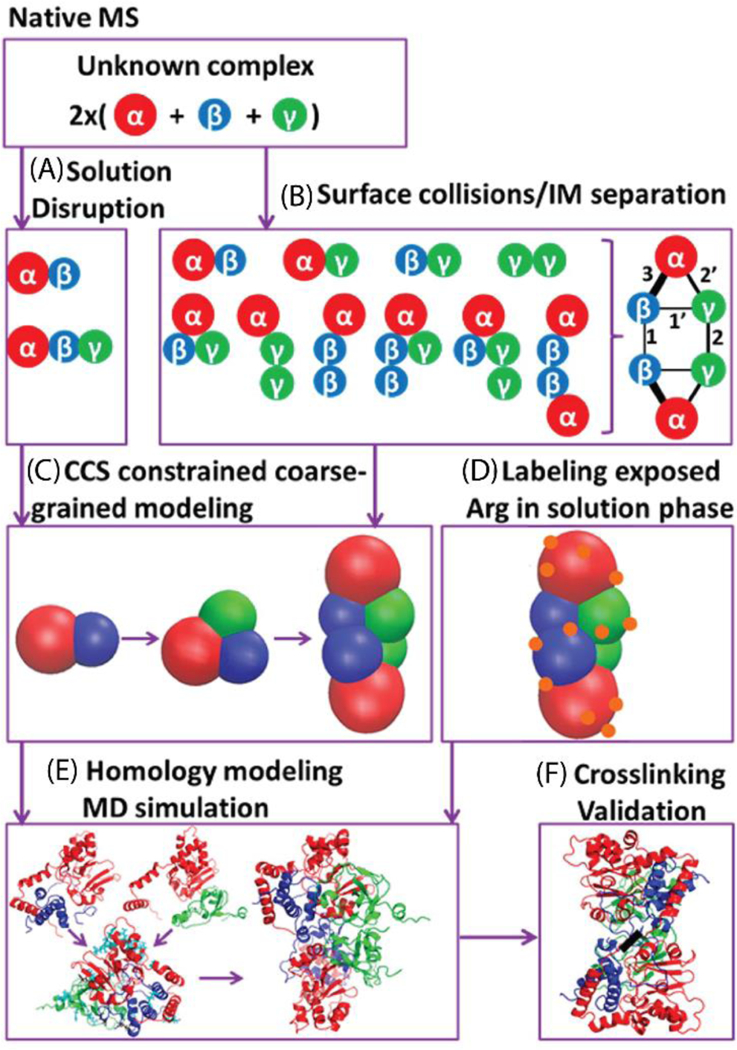

The main application of SID lies in probing non-covalent assemblies to obtain information on their initial in-solution topology/connectivity. Early work has focused on exploring the capability of SID for structural analysis by probing protein complexes of known structure.26,61 However, the need to obtain quaternary structural information for proteins that are elusive to other characterization methods, as well as an increased understanding of SID, have driven its usage for the confirmation of computationally designed proteins as well as for the investigation of protein complexes with no known structure.59,172,195 Recently, SID has been demonstrated for the analysis of computationally designed protein complexes. Dissociation into subcomplexes characteristic of the intended hetero-dodecamer design of two trimers connected by three dimers was observed for three different dodecamers.196 Taking into account advances in design of protein interfaces and de novo protein complexes,197–199 it is reasonable to assume that native MS in conjunction with SID will provide a means for rapid structural screening of a large number of protein complex designs, and will help to accelerate the development and optimization of computational design protocols by providing fast feedback on the topology of the obtained protein complexes. SID is now also frequently used to study protein-ligand, protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid interactions in quaternary assemblies derived from nature. In conjunction with IM measurements, SID provided insights into Cu(I) binding to the homo-tetrameric copper-sensitive operon repressor (CsoR) from Bacillus subtilis.200 Whereas the apo protein predominantly dissociated into monomers, Cu(I)-bound CsoR preferentially dissociates into dimers, requiring much higher SID energy in line with the coordination of Cu(I) between two subunits.200 Combined with other techniques, SID has recently been employed to investigate the quaternary structure of the two hetero-oligomeric complexes manganese oxidase (Mnx) from Bacillus sp. PL-12 and toyocamycin nitrile hydratase (TNH) from Streptomyces rimosus. Mnx plays an important role in biomineralization. It consists of three different subunits (MnxE,F,G), two of which have no homolog of known structure. This made it impossible to model the quaternary structure and obtain information on the structure-function relationship of this enzyme complex. Whereas the average diameter of the complex as well as the process of biomineralization could be observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and CID only produced MnxE and MnxF monomer ejection (Figure 9A–B), SID revealed that MnX is composed of one MnxG bound to a MnxE3F3 hexamer. Subcomplexes generated from this hexamer at higher collision energies suggested it to be a cyclic assembly composed of alternating MnxE and MnxF subunits (Figure 9C–E). Information on complex topology derived from SID-IM-MS in conjunction with docking of ab initio models for MnxE and MnxF and a homology model for MnxG allowed the authors to build a structure of this complex (Figure 9F).195 Like Mnx, TNH is a hetero-oligomeric complex composed of three different subunits. TNH catalyzes the hydration of a nitrile to an amide, a reaction of significant importance for industry. Using the abundance of subcomplexes generated at different SID energies as guide, the topology and relative interface strength of TNH were assessed. In combination with covalent labeling and cross-linking mass spectrometry data, homology and coarse grain modeling were utilized to determine that the TNH complex consists of two αβγheterotrimers connected via the β- and γ-subunits (Figure 10).59

Figure 9.

A structural model of the Mnx complex was built using information from SID experiments. (A) Ion mobility displays the selection of the 29+ Mnx complex, (B) products from 120 V CID, products from (C) 40 V and (D) 120 V SID. (E) Subcomplexes produced in SID revealed the topology of this complex. Because dimers released from the complex were predominantly E1F1 and trimers were predominantly E1F2 and E2F1, the strong presence of heterodimers and heterotrimers suggested a symmetric structure consisting of alternating E and F subunits. (F) Using the topology suggested from SID data in combination with additional restraints such as CCS and surface labeling results, computational models were generated to allow for docking experiments modeling the Mnx complex. Reprinted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature Communications (Romano, C.A., Zhou, M., Song, Y., Wysocki, V.H., Dohnalkova, A.C., Kovarik, L., Paša-Tolić, L., Tebo, B.M. Biogenic manganese oxide nanoparticle formation by a multimeric multicopper oxidase Mnx. Nature Comm. 2017, 8:746), copyright 2017.

Figure 10.

Workflow for protein structure identification by MS and complementary methods. SIDIM-MS and in solution disruption data provide information on the topology and shape of the complex and constituting sub-complexes (A-F). In combination with additional constraints, for instance obtained from labeling and crosslinking experiments, detailed structural models can be built. This Figure depicts the strategy used to obtain a quaternary structure model for TNH. Reprinted with permission from Song, Y.; Nelp, M. T.; Bandarian, V.; Wysocki, V. H., Refining the Structural Model of a Hetero-hexameric Protein Complex: Surface Induced Dissociation and Ion Mobility Provide Key Connectivity and Topology Information, ACS Central Science, 2015, 1, 477487. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

SID as a tool to probe the quaternary structure of RNA-protein complexes

Fundamental biological processes including regulation of gene expression, RNA splicing, and protein synthesis are all facilitated by RNA-protein interactions.201 To understand these processes in detail, it is essential to obtain structural models of the ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) involved. Structural models of high enough resolution to enable the study of position, orientation and interactions of individual atoms within RNPs are often time consuming or impossible to obtain.202 The structural characterization of RNA and RNPs is highly challenging mainly due to limitations for obtaining homogeneous samples at a concentration and purity suitable for X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy, which is also reflected by the small proportion of RNP structures relative to all structures deposited in the PDB (~ 5%).203,204 Native mass spectrometry can act as a complement to those techniques due to its sensitivity and relatively high tolerance to heterogeneity. The study of RNA and RNPs imposes additional requirements on native MS when compared to the study of soluble proteins and protein complexes. For instance, interactions of cations with the negatively charged RNA backbone often causes extensive adducting, resulting in peak broadening.205 In many cases, Mg2+ cannot be omitted from the sample solution as it is required for the structural integrity and the ability of RNAs to interact with their partnering proteins.206 However, limiting the Mg2+ concentration along with careful tuning of instrument conditions can make the study of RNA and RNPs manageable by native MS. For example, Ma et al. recently utilized SID-IM-MS to determine the stoichiometry of Pyrococcus furiosus RNaseP, an archeal RNP that catalyzes the maturation of tRNAs.207 Utilizing a minimum amount of Mg2+ (2 mM) needed to maintain enzymatic activity, individual charge states could be resolved and quadrupole-selected for CID and SID experiments. While it was not possible to dissociate the complex by CID, SID produced a variety of subcomplexes that indicated that the RNaseP complex consists of RPP21, RPP29, POP5, and RPP30 subunits bound to the catalytic RNaseP RNA. Future work will examine the 5-protein complex that includes L7Ae and will attempt softer tuning than was possible in the earlier study. In another work, the ternary complex between Prolyl-tRNA synthetase (ProRS), tRNA, and editing domain Ybak, which is formed to ensure the fidelity of tRNA charging with the correct amino acid, was investigated by native MS.208 In a first step, the (ProRS)2tRNAPro and YbaK/tRNAPro complexes were probed by SID and CID, respectively. Subsequent analyses of the complete complex provided insights into its ProRS/tRNA/YbaK stoichiometry of 2:1:1.209 This work highlights the utility of native MS and SID to assess the stoichiometry of RNPs with unknown structure.

SID of Membrane proteins

Membrane proteins are essential for many tasks including signal transduction and energy generation.210 This essential class of proteins makes up about 60% of known drug targets, however,211 only < 3% of the entries in the PDB are for membrane proteins. This is due to the fact that structural characterization of this class of proteins is very challenging because of their low expression yields, insolubility in aqueous solutions, and tendency to aggregate.212 MS is emerging as a powerful tool to study membrane protein complexes, in part because relatively small amounts of material are needed compared to traditional techniques.43,213,214 In order to retain their native oligomeric state and conformation, membrane proteins must be solubilized using a mimic for the membrane environment. For MS studies, this typically involves the use of detergent micelles, amphipols, or nanodiscs so that these membrane protein-containing assemblies can be introduced intact into the mass spectrometer and then disrupted with collisional activation or by heating of the source region.215–217

Harvey et. al., first reported the use of SID as a structural characterization method for membrane protein complexes.218 In this proof-of-concept study they chose two integral membrane proteins, trimeric AmtB and tetrameric AqpZ from Escherichia coli. Both complexes have solved crystal structures and had been studied previously with native MS using the charge-reducing detergent tetraethylene glycol monooctyl ether (C8E4).219 When AmtB and AqpZ were sprayed from C8E4 in a modified Waters Synapt G2, CID resulted in limited dissociation, with highlycharged, unfolded, monomer being the major product observed. SID of trimeric AmtB, with the SID device placed between the trap and IM cell of the Synapt G2,138 resulted in the production of compact monomers and dimers, consistent with the ring-like structure of this complex which has equal interfaces between all subunits. Similar results were observed for tetrameric AqpZ, with compact monomers, dimers and trimers being observed in agreement with the solved structure (cleavage at two interfaces is required to produce free fragment ions - monomer:trimer and dimer:dimer). This study highlighted that SID of membrane protein complexes produces subcomplexes consistent with their solved structure and therefore has potential in the study of membrane protein complexes without solved structures.

The Robinson lab has recently demonstrated the use of SID as a method to probe membrane protein lipid binding and selectivity. In these studies semiSWEET, a dimeric bacterial sugar transporter, was studied using a modified Synapt G2-Si with a longer TOF for enhanced resolution, SID before the IM, and a segmented quadrupole in place of the transfer ion guide.220 Previous studies have demonstrated that semiSWEET is stabilized through binding of cardiolipin and shows selectively towards longer chain lengths.221–223 In their SID studies, Robinson and coworkers observed greater stabilization of dimers with longer chain lengths of cardiolipin, consistent with the previous studies showing selectivity towards longer chain lengths. This study highlighted that SID can be useful tool to study membrane protein lipid interactions and that CID did not allow the distinction that was possible by SID.

SID APPLICATIONS OUTSIDE OF STRUCTURAL BIOLOGY

In addition to its utility for structural biology studies, SID has also been used for other applications. We present here a brief summary of other studies that have taken advantage of SID.

The use of SID for the study of lipid structure

In the McLean lab at Vanderbilt University, SID has recently been applied to the study of lipids as a potentially advantageous method of observing greater fragmentation than possible by CID. In the study of phosphatidylcholines, it has been shown that SID results in greater fragmentation than CID when comparing equivalent lab frame energies. Head group loss and subsequent head group breakdown shows a similar trend between the two techniques. While the types of fragments produced between the two techniques are the same, SID does so at lower lab frame energies, providing higher-energy fragments that would not be accessible by CID within instrument acceleration voltage limits. While this work is still ongoing, it shows promise for production of fragments that typically appear in lower abundance via CID and that can be used in indicating fatty acyl composition in the lipids.224

Combining simulations and SID

Another area in which SID has proven useful is the study of fragmentation energetics and mechanisms. The relationship between simulations, mechanisms, and SID fragmentation patterns are important in understanding the experimental outcome of ion-surface collisions.225 Combining quantum mechanical/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) simulations and RRKM modeling, Laskin and coworkers have been able to explain fragmentation kinetics of singly-protonated peptides that have enough vibrational energy to fragment yet do not show fragmentation during the experimental time period.226 Additionally, by utilizing a combination of time- and collision energy-resolved SID experiments and resonant ejection experiments, dissociation pathways and dissociation onset energies for basic residues have also been investigated. Specific peptides were used to represent dissociation via salt-bridge and canonical pathways. Using resonant ejection in the dissociation of these peptides allowed for both fast and slow kinetics to be studied, in the msec to sec timeframe of the ICR.227

Hase and coworkers have contributed significantly to the understanding of SID by utilizing chemical dynamics simulations to investigate energy transfer upon collision with a surface in addition to mechanisms of soft-landing and reactive-landing. Utilizing a QM approach for the intramolecular potential of the protonated peptide and an MM approach for the surface as well as interaction between the surface and protonated peptide, comparisons between experimental results and simulations can be made for protonated peptide fragmentation to provide a better understanding of the SID mechanism and dynamics involved upon such collisions.225,228,229

SID for the characterization of metal-organic cluster ions

Within recent years SID has also been utilized in the study of ultra-small gold cluster ions consisting of 7–9 Au atoms ligated with phosphines. Such ultra-small gold clusters can be useful in catalysis and energy production. However, the complexity (with greater than 500 vibrational degrees of freedom) and size of these clusters make it particularly challenging to obtain information needed for scalability such as thermodynamic and kinetic parameters for clusters with a specific number of Au atoms and charges. In one study, SID was used to investigate the size-dependent stability toward fragmentation as well as ligand binding energies because no other direct experimental measurements exist. The ability of SID to remain sensitive to small variations in threshold energies as well as activation entropies makes SID a valuable choice in probing the dissociation of these ions.230 This allowed observation of dissociation pathways that could then be related back to RRKM-based modeling. SID has also been utilized with monolayer-protected silver clusters to identify gas-phase structural isomers, perhaps pointing to different cluster configurations. SID provided different fragmentation of these isomers than CID at similar energy, producing a wide range of fragments and resulting in charge stripping that had not yet been observed with similar gold or silver clusters.231

EMERGING COMPLEMENTARY TECHNOLOGIES

Native MS coupled to SID and/or other activation methods, and to ion mobility, can be used throughout the biochemical/biological study of a complex, allowing mid-course adjustments and guiding higher resolution (X-ray crystallography, NMR, cryoEM) studies that are too time and resource intensive to be used in routine work. Many groups have come to recognize, however, that extensive protein purification followed by manual desalting with spin columns, or dialysis, and static (nano)electrospray approaches is too slow for routine application to structural biology throughout a study. Direct introduction of cell lysates using static nano-spray for detection of overexpressed protein complexes has been reported, which simplifies the protein purification steps.232,233 The long-term goal for such studies would be to study single cells. An alternative approach to this is online desalting.234 Online desalting offers the advantage of higher-throughput and reduced sample handling compared to conventional desalting approaches and the potential to automate the use of native MS for routine screening of protein complexes. We describe below the efforts in this field, including additional approaches to automate native MS acquisition and SID experiments.

Non-denaturing rapid online desalting coupled to native mass spectrometry

One of the critical steps in the native mass spectrometry workflow is sample preparation to remove non-volatile salts and additives. The presence of non-volatile salts, buffers or additives in the sample will sacrifice sensitivity, mass accuracy, and mass resolution and will often lead to increased down time for cleaning of the mass spectrometer. To avoid these problems, the structures and functions of proteins and protein complexes are typically studied in volatile buffers. For many years, this has been accomplished by buffer exchanging the biological sample into a volatile electrolyte such as ammonium acetate prior to MS analysis. This method works very well, however, the use of gel filtration spin columns or ultrafiltration devices to perform the buffer exchange can become time consuming and cumbersome when analyzing large numbers of samples. Furthermore, it is often not obvious how extended storage in MS-friendly buffers might affect the protein integrity. Consequently, several alternatives to the manual buffer exchange process have been developed. It has also been shown that the presence of additives such as electrolytes,235,236 amino acids,162 or supercharging agents237 can help to mitigate some of the adverse effects of non-volatile salts. While these results are impressive, they are typically used during protein purification. More recently, Williams and coworkers have shown that the use of sub-micron nanospray emitters provides the ability to ionize proteins directly from high concentrations of non-volatile buffers while still achieving narrow, well-resolved protein signals. The simplicity of using a narrow diameter nanospray emitter to spray samples directly from biological buffers is appealing and this approach is being characterized in the native MS community. However, results indicate that the signal from non-volatile salts in the low m/z region still dominates the protein signal even when spraying from narrow emitters, which may cause interference with species in this m/z region. Furthermore, narrow emitters tend to clog more readily than larger nanospray emitters, making it more difficult to automate this process.

An alternative approach is to physically separate non-volatile salts from the analyte of interest such as by manual buffer exchange, but doing so in a rapid, high-throughput and automatable manner. To the best of our knowledge, Shen et al. were the first to couple size exclusion chromatography online with mass spectrometry for the detection of non-covalent protein complexes.238 This method was further improved to provide robust removal of non-volatile salt in a rapid and efficient manner using self-packed gel filtration columns and automated using traditional HPLC equipment.234,239 Additionally, online desalting methods based on diffusion,240 dialysis,241,242 and electrophoresis243 have also been demonstrated.

Size exclusion-based methods benefit from the wide variety of commercially available SEC columns and resins currently available, and the ease of automation with basic HPLC equipment. Building off the work by Cavanagh et al. and Waitt et al.,234,239 we recently showed that online desalting can be implemented easily in any native MS lab for the routine screening of native protein complexes. VanAernum et al. showed that a wide range of proteins and protein complexes can be separated from different biological buffers including phosphate, Tris and HEPES- based buffers, as well as different additives such as glycerol, imidazole, and DMSO. (Manuscript in preparation) Analysis time, including flushing salt from the columns, is approximately 3 minutes per sample. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that the desalting could be automated as an MS, MS/MS and/or MS-IM-MS experiment, extending the rapid screening approach to subunit dissociation studies in addition to the intact complex measurement. Using this approach, we were able to screen > 100 heterodimers in an effort to provide rapid feedback on successful protein complex designs.244 This approach continues to be useful and widely utilized in the Wysocki lab and other labs for general screening of large numbers of protein complexes.232,245

Towards automation and simplified tuning of SID-MS

The work described in this review demonstrates the utility of SID as a structural biology tool, however further dissemination into the structural biology community will require technological advances to improve the usability of SID by non-experts. Ongoing work in the Wysocki lab involves redesigning SID devices for increased ion transmission, product ion collection efficiency, decreased mass- and energy-dependent bias, and increased ease of tuning (unpublished data). Furthermore, progress is being made in automation of SID experiments to produce energy resolved mass spectra over a wide range of SID energies without user intervention or manual data collection. Future work will focus on developing data dependent SID capabilities to allow dissociation of protein complexes by SID on a chromatographic time scale. Online SID MS/MS capabilities will become even more beneficial as the application of non-denaturing separation techniques continues to advance.246

As native mass spectrometry becomes an increasingly important tool in structural biology, it will be beneficial to have an automated workflow to screen samples for molecular weight, subunit connectivity, and topology. To this end, we envision that the incorporation of automated gel filtration-based online desalting and automated (SID/CID/UVPD) MS/MS methods along with data analysis packages capable of automated processing of MS and IM data will further cement native MS in the structural biology toolbox.

Coupling with computational structure prediction

The power of mass spectrometry as a structural biology tool is greatly increased when coupled with computational methods, which can provide a greater depth of information. Computational methods are routinely used with IM data to determine theoretical CCS from solved structures or computational models, which can be compared with the experimental CCS.102,247,248 In addition, computational tools to assist in structure prediction exist for complementary techniques such as crosslinking and HDX.249–251 A previous report has coupled SID, IM, and covalent labeling data with coarse-grained computational approaches to predict a structure for a heterohexamer whose structure was unknown,59 however, the coupling of SID with computational structure prediction is not yet routinely done. We expect that SID data could provide useful structural restraints which would assist in the structure prediction process and research in this area is currently underway.252

FUTURE OUTLOOK

Native MS coupled to SID, along with current commercially available activation methods and ion mobility, is a useful tool for characterization of protein and nucleoprotein complexes and is complementary to other structural biology tools. As mass spectrometers designed to characterize higher-mass complex assemblies continue to improve, effective dissociation methods such as SID will be needed to fragment those large complexes. Furthermore, as cryoEM studies continue to rapidly expand our detailed working knowledge of protein structure and function, we predict that native MS coupled to surface-induced dissociation and applied to structural biology questions will become increasingly important for oligomeric state determination, sample preparation optimization, and for providing connectivity information for 3D structural refinement. SID is already playing a role in characterization of designed protein and protein complexes and we expect that to continue and expand. Several challenges remain before SID becomes a mainstream commercial activation method. Improvements to the SID devices are needed so that they will work optimally for the MS instrument types that will play a strong role in future structural biology studies. Coupling of SID to other activation methods, to allow fragmentation of complex to subcomplex and subcomplex to covalent fragments, needs to be developed for complex-down characterization of protein complexes. Coupling of SID to improved resolution ion mobility will allow improved structural characterization so IM improvements are desired along with SID improvements. As progress on these technology developments is made, e.g., within the NIH-funded Biomedical Technology Research Resource that supports SID and IM development for structural biology studies, SID will initially be offered to early adopters via third party vendors. As use of these early disseminated SID devices increases, instrument vendors will make decisions on whether to fully commercialize and support SID as an activation method in mass spectrometers specifically designed for structural biology applications.

Acknowledgements