1.0. Introduction

HBV is a hepatotropic DNA virus that replicates by reverse transcription [1]. The virus is genetically diverse, with at least 8 genotypes that differ by ~8% at the amino acid level. It chronically infects about 290 million people world-wide, causing hepatitis, hepatic fibrosis, and cirrhosis that lead to the death of >850,000 patients annually via liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma [2]. Therapy primarily employs nucleos(t)ide analog drugs that can drive HBV below the detection limit, but interferon α is used in some patients [3]. The ideal goal of therapy would be a complete cure, in which no trace of the virus remains in the body and HBV-induced disease is eliminated. Unfortunately, extremely low levels of replication competent HBV can persist in patients even after they have appeared to resolve an acute infection. Therefore, the consensus is that the goal of HBV treatment, at least for the foreseeable future, will be a “functional cure”. The clinical definition of a functional cure is still being debated, but it essentially means attaining a stable state where there is no detectable virus in the body after drug withdrawal and disease progression has been halted [4]. Current therapies achieve a functional cure in only a few percent of patients [5] because viral replication is not completely suppressed and HBV titers resurge if the nucleos(t)ide analogs are withdrawn. Furthermore, the overall chances of death from liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma induced by chronic HBV infection are reduced by only ~2- to 4-fold [3].

Reverse transcription is catalyzed by the coordinate action of the viral reverse transcriptase (RT) and ribonuclease H (RNaseH) activities located on adjacent domains of the viral polymerase protein [1]. RNaseHs cleave RNA within an RNA:DNA heteroduplex, and the role of the HBV RNaseH is to degrade the viral RNA after it has been copied into DNA by the RT to permit synthesis of the second DNA strand. Inhibiting the RNaseH causes synthesis of the viral minus-polarity DNA strand to stall and blocks synthesis of the plus-polarity strand. This fatally damages the viral DNA. No drugs have been developed against the RNaseH despite its essential function, primarily due to lack of suitable screening assays.

2. Prospects for HBV RNaseH drugs

2.1. The RNaseH as a drug target

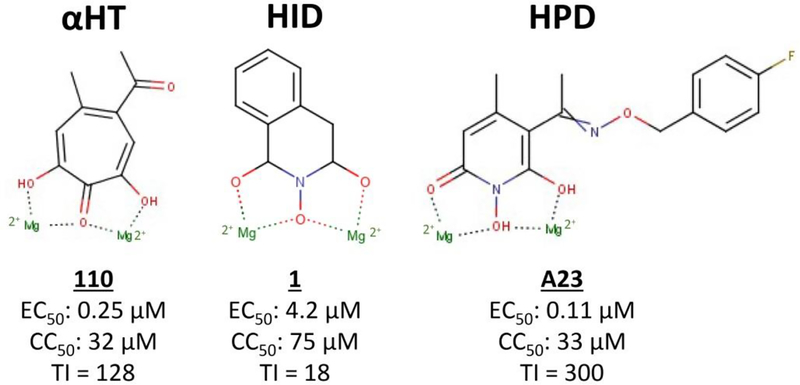

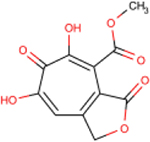

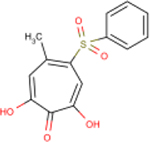

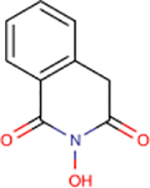

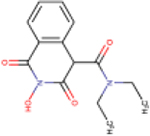

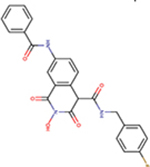

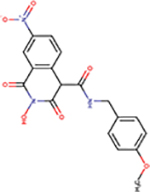

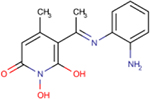

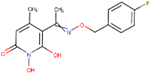

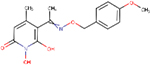

The HBV RNaseH is an attractive drug target because disabling it causes accumulation of RNA:DNA heteroduplexes in capsids, prematurely arrests most minus-polarity DNA strands, and blocks production of the plus-polarity DNA strand [6]. Expression of functional recombinant HBV RNaseH [7] prompted development of pipelines of biochemical and cell-based screening assays that are sensitive to RNaseH inhibition. Over 130 RNaseH inhibitors have been identified that suppress HBV replication in culture with 50% effective concentrations (EC50) from low micromolar values to ~100 nM, primarily in three chemotypes, the α-hydroxytropolones (αHT), N-hydroxyisoqinonlinediones (HID), and N-hydroxypyridinediones (HPD) [8–12] (Fig. 1). 50% cytotoxic concentrations (CC50) range from 3 to >100 μM with therapeutic indexes (TI, CC50/EC50) of up to 350. The most effective compound to date is A23, with an EC50 of 0.11 μM and a TI of 300 [10].

Fig. 1. Example HBV RNaseH inhibitors.

The relative location of the Mg++ ions as they would be found when the inhibitors are bound in the RNaseH active site is shown. HBV, Hepatitis B Virus; RNaseH, ribonuclease H.

These compounds inhibit the HBV RNaseH in biochemical assays and cause accumulation of RNA:DNA heteroduplexes in viral capsids, confirming they target the RNaseH [6,9]. The RNaseH inhibitors repress HBV RNaseHs from three genotypes, indicating that HBV’s high genetic diversity is unlikely to complicate drug development [13]. The inhibitors are synergistic with the nucleoside analog drug Lamivudine and additive with the experimental HBV capsid protein assembly modifier Hap12 without enhancing cytotoxicity [10,14]. Two RNaseH inhibitors, an HPD (208) and an αHT (110), can significantly suppress HBV replication in chimeric mice carrying humanized livers [15]. Despite having to use unoptimized primary screening hits in this mouse study, it proved that RNaseH inhibitors can work in vivo. Together, these data validate the HBV RNaseH as a drug target.

2.2. Mechanism of action: Metal chelation

RNaseHs have a “DEDD” motif in their active sites that coordinates two Mg++ ions, and RNA cleavage requires both divalent cations to promote hydroxyl-mediated nucleophilic scission. The HBV RNaseH is Mg++-dependent, and all known HBV RNaseH inhibitors have metal-coordinating moieties that could chelate the cations in the active site. Disrupting ability of the compounds to coordinate Mg++ ablates inhibition, so the HBV RNaseH inhibitors appear to share the metal-chelating mechanism used by HIV RNaseH inhibitors [16] (Fig. 1).

Metal chelation has a poor reputation in some drug discovery circles due to the perceived propensity of metal coordinators to promiscuously inhibit metalloenzymes. This view needs to be revised because 64 drugs based on metal-binding groups have earned FDA approval as of 2017 [17]. For example, metal chelation is central to efficacy of HIV integrase strand transfer inhibitors such as Elvitegravir and Raltegravir and the recently approved anti-Influenza Virus drug Baloxavir marboxil. The potential for HBV RNaseH inhibitors to be specific is highlighted by the high TI values of many of the compounds and by counter-screening against a panel of human pathogens and the human RNaseH1 (Table 1). Therefore, the metal chelation mechanism is not a liability for HBV RNaseH drug development.

Table 1.

Performance of example HBV RNaseH inhibitors

| Compound | Formal Name | Structure | EC50 HBVa | CC50a | TIb | IC50 Human RNaseH1a | HSV-1 inhibitionc | MIC80 E. colid | MIC80 Staphylo-coccus spp.d | MIC80 C. neoformanse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αHT | ||||||||||

| 46 | β-Thujaplicinol |  |

1.0 ± 0.6 | 25 ± 20 | 25 | 58 | 5 | 44 | 20 | 8 |

| 107 | CM1012–6b |  |

0.4 ± 0.2 | >80 | >200 | 221 | - | - | - | 50 |

| 280 | AG77 |  |

0.5 ± 0.1 | >77 | >154 | 177 | - | - | - | - |

| 336 | YA-I-78 |  |

0.4 ± 0.2 | 45 ± 8 | 130 | 37 | + | - | 44 | - |

| HID | ||||||||||

| 1 | TRC 939800 |  |

4.2 ± 1.4 | 75 ± 24 | 18 | 218 | - | - | - | - |

| 83 | MB88 |  |

2.3 ± 1.6 | 100 ± 35 | 43 | 45 | - | - | - | ND |

| 86 | VS42 |  |

1.4 ± 0.3 | 99 ± 2 | 71 | 158 | - | - | ND | ND |

| 89 | VS51 |  |

2.6 ± 0.8 | 28 ± 8 | 11 | 111 | - | ND | ND | ND |

| HPD | ||||||||||

| 208 | Sun B8155 |  |

0.69 ± 0.2 | 15 ± 7 | 22 | 194 | - | - | - | ND |

| A23 | ARB-270496–1 |  |

0.11 ± 0.01 | 10 ± 2 | 300 | 21 | - | - | ND | ND |

| A24 | ARB-270497–1 |  |

0.29 ± 0.1 | 31 ± 16 | 352 | 28 | - | - | ND | ND |

μM

CC50/EC50

Log10 reduction in viral titers at 5 μM; -, <10-fold reduction of titers at 5 μM; + >10-fold reduction in titer at 5 μM

Minimum inhibitory concentration 80% (MIC80) (μM); -, no inhibiton at 70 μM

MIC80 (μM); -, no inhibition of growth at 50 μM

Abbreviations: EC50; 50% effective concentration; CC50, 50% cytotoxic concentration; TI, therapeutic index; IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; RNaseH1, ribonuclease H1; HSV, Herpes Simplex Virus;

MIC80, minimal 80% inhibitory concentration; E. coli, Escerichia coli; Spp., any of multiple species within a genus; αHT, α-Hydroxytropolones; HID, N-Hydroxyisoquinolinediones; HPD, N-Hydroxypyridinediones; ND, not determined.

2.3. Biochemical screening: Insensitive enzyme or outstanding target?

Recombinant HBV RNaseH is typically about 50-fold less sensitive to RNaseH inhibitors than is viral replication in culture. Inhibition of HBV replication can be confirmed for the inhibitors by detecting accumulation of RNA:DNA heteroduplexes in capsids [6,9], excluding off-target effects for the quantitative discrepancy. We see two possible explanations for this discrepancy. First, and most probable by Occom’s Razor, is that the recombinant HBV RNaseH does not fully reflect the activity of the native enzyme. This is plausible because the recombinant enzyme is produced in E. coli rather than human cells, and it contains only the RNaseH domain from the four-domain HBV polymerase protein. However, recent studies employing a recombinant enzyme carrying both the RT and RNaseH domains of the polymerase did not resolve the insensitivity of the recombinant RNaseH to inhibition, nor has altering the enzyme sequence, the purification protocol, or assay conditions. This raises an intriguing alternative possibility: that the recombinant enzyme accurately reflects the primary efficacy of the inhibitors, and that HBV reverse transcription is very sensitive to disruption of the RNaseH activity. This could occur if the majority of the RNaseH cleavages during reverse transcription were to employ the enzyme’s recently identified 3’ to 5’ exonuclease activity [7] rather than the endonucleolytic activity that is measured in the biochemical assays, and if the enzyme cannot back up once it has translocated far enough that the RNA’s 3’ end is no longer in the RNaseH active site. If this latter explanation is true, then RNaseH inhibitors would share one of the key assets of nucleo(s)tide analog DNA elongation terminators: blocking only one or a few catalytic cycles during reverse transcription terminates production of functional HBV genomes.

2.4. Prospects for RNaseH drugs in combination therapies

Achieving a functional cure for chronic HBV infection will be challenging due to HBV’s diverse clinical presentation, the extensive liver damage present in many patients when they are diagnosed, and the stability of the covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), the non-replicating form of the viral genome that is the transcriptional template for all viral RNAs. Of these challenges, eliminating the cccDNA will be the most difficult due to the cccDNA’s long half-life, which indicates a low turnover rate.

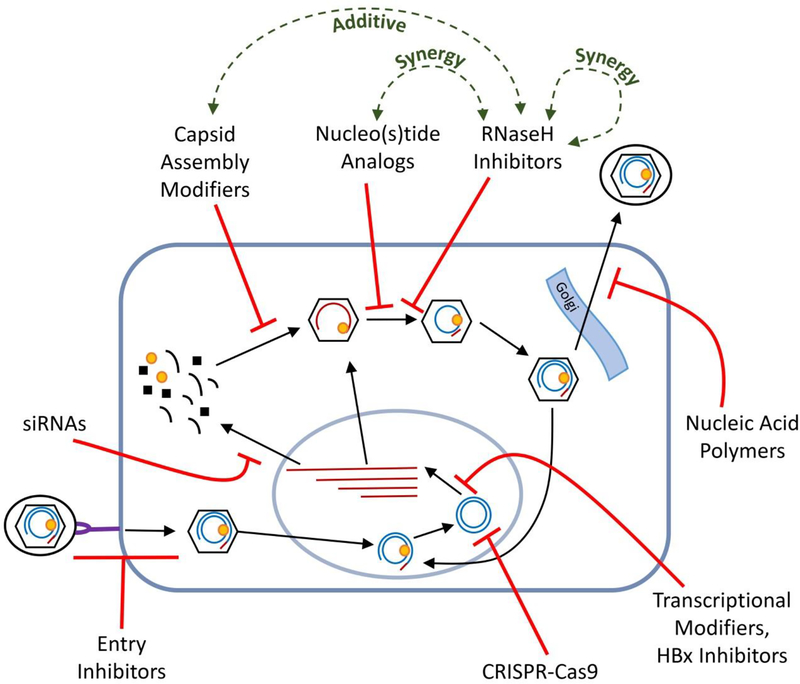

The inability of interferon α and nucleos(t)ide analog therapies to clear the cccDNA in a significant fraction of patients despite causing deep reductions in serum viremia has led to the widespread conviction that combination therapy is the best route to a cure. A wide range of novel drug development strategies are being pursued in support of combination therapy. Direct-acting agents targeting viral functions include capsid assembly modifiers, siRNAs, entry inhibitors, anti-cccDNA CRISPER/Cas9s, improved nucleos(t)ide analogs, nucleic acid polymers, transcriptional modifiers, HBV X antigen inhibitors, RNaseH inhibitors, and others (Fig. 2). All these efforts except the anti-cccDNA approaches share the basic strategy of suppressing viral replication beyond what is currently possible. As it is unclear if profound suppression of viral replication can lead to a cure by itself, immune-modulators are also under rigorous development. These approaches include therapeutic vaccination, adoptive T-cell strategies, cytokines such as TLR7, etc. We believe that curative therapies are likely to require both direct-acting drugs and immune modulators because cure requires eliminating or inactivating all cccDNA molecules, a tall task for replication inhibitors by themselves.

Fig. 2. Relationship of HBV RNaseH inhibitors to approved and experimental drugs.

HBV’s cellular replication cycle is shown indicating the site of action for major classes of inhibitors. These direct-acting approaches except cccDNA targeting agents (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9) and the HBV surface antigen secretion inhibitors (e.g., nucleic acid polymers) share a common strategy of suppressing viral replication without directly attacking the viral cccDNA. RNAs are shown in red; DNAs are in blue; Gold oval, the HBV polymerase that carries both the RT and RNaseH enzyme activities. HBV, Hepatitis B Virus; cccDNA, covalently closed circular DNA (the viral transcriptional template); CRISPER, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; Cas9, CRISPER-associated sequence 9; RT, reverse transcriptase; RNaseH, ribonuclease H.

The diverse disease spectrum among HBV patients and HBV’s high genetic diversity indicate that multiple drug combinations will almost certainly be required to attain high functional cure rates. This is conceptually similar to the multiple drug combinations needed to attain widespread control of HIV viremia and to cure HCV infections. HBV RNaseH inhibitors are well placed to be included among the drugs in a curative pharmacological arsenal (Fig. 2). This is because HBV RNaseH inhibitors work synergistically with nucleoside analogs and additively with capsid assembly modifiers, are insensitive to HBV’s genetic variation, and different chemotypes of RNaseH inhibitors can be synergistic with each other [10,14]. Developing such a battery of anti-HBV drugs may finally achieve the long-sought goal of achieving a functional cure for chronic HBV infections.

3. Expert Opinion

Work with the HBV RNaseH has yielded drug discovery pipelines, identified inhibitors from multiple chemotypes worthy of exploration, and validated the RNaseH as a drug target. The mechanism of action is almost certainly via specifically chelating the two Mg++ ions in the enzyme active site. The successes in developing other drugs that act by chelating active site cations, including the HIV integrase strand transfer inhibitors and an inhibitor of the Influenza Virus cap-snatching PA endonuclease, set a clear precedent for developing anti-RNaseH drugs that work by this mechanism. The goal of anti-RNaseH efforts should be to develop RNaseH drugs that can be combined with drugs that work by other mechanisms to cure chronic HBV infections. As curative HBV treatments are likely to take many months to years and to frequently be used in patients with badly damaged livers, minimizing both adverse drug-drug interactions and toxicity will be essential.

Key among the challenges to developing anti-RNaseH drugs that extend beyond the standard complexities of drug development are designing high throughput screening assays for RNaseH inhibitors and determining the enzyme’s structure to accelerate discovery efforts. Also important will be resolving whether the poorer efficacy of RNaseH inhibitors against the purified enzyme compared to their ability to suppress HBV replication in cells stems from limitations to the recombinant enzyme or from HBV replication being unanticipatedly sensitive to RNaseH inhibition. As development proceeds, it will be essential to explore compatibility of the inhibitors with drugs that work by complementary mechanisms as early as possible.

Curative therapies for HBV will be challenging due to the clinical complexity of HBV disease and the durability of the cccDNA form of the viral genome in cells. Curing HBV is likely to require drugs that profoundly inhibit HBV replication rather than just eliminate viremia and that have outstanding pharmacokinetic profiles that eliminate suboptimal drug concentration troughs. This will block cccDNA generation in the liver and ease its clearance. RNaseH inhibitors are not anticipated to have direct effects on pre-existing cccDNA molecules and would contribute to cccDNA clearance in this manner. The direct-acting agents in future drug cocktails will almost certainly need to be paired with very safe immune-activating drugs that can mop-up cells containing residual cccDNA that could restart HBV replication following drug withdrawal and re-infect the liver. The novel mechanism of action employed by RNaseH inhibitors and their ability to work together with existing and experimental drugs make them strong candidates for a place among the direct-acting agents within the curative drug cocktails that the field is urgently seeking.

Funding

The work was supported by NIH R01 AI122669, NIH R21 AI124672, and DoD PRMRP Investigator-Initiated Grant PR170380 awarded to J Tavis.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

J Tavis holds awarded and pending patents associated with the subject matter and materials reported in this manuscript. Some of the intellectual property underlying the work reported in this article has been licensed to Casterbridge Pharmaceuticals, Inc, MO, USA. J Tavis is a stockholder and scientific advisor to Casterbridge Pharmaceuticals. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers

- 1.Seeger C, Zoulim F, Mason WS. Hepadnaviruses In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. 6 ed. Philadelphia PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. p. 2185–2221. [Google Scholar]; * This is the premier review on HBV biology.

- 2.Polaris Observatory Collaborative. Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018. June;3(6):383–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lok AS, McMahon BJ, Brown RS Jr, et al. Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B viral infection in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2016. January;63(1):284–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Testoni B, Levrero M, Zoulim F. Challenges to a Cure for HBV Infection. Semin Liver Dis. 2017. August;37(3):231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zoulim F, Durantel D. Antiviral therapies and prospects for a cure of chronic hepatitis B. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015. April 1;5(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tavis JE, Cheng X, Hu Y, et al. The hepatitis B virus ribonuclease h is sensitive to inhibitors of the human immunodeficiency virus ribonuclease h and integrase enzymes. PLoS pathogens. 2013. January;9(1):e1003125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This is the initial report of active HBV RNaseH and that it can be pharmacologically inhibited. It is somewhat dated by advances in both biochemsitry and drug discovery, but remains the foundational paper for this area.

- 7.Villa JA, Pike DP, Patel KB, et al. Purification and enzymatic characterization of the hepatitis B virus ribonuclease H, a new target for antiviral inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 2016. June 16;132:186–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This is the most advanced report on the HBV RNaseH biochemistry to date.

- 8.Lu G, Lomonosova E, Cheng X, et al. Hydroxylated Tropolones Inhibit Hepatitis B Virus Replication by Blocking the Viral Ribonuclease H Activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(2):1070–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards TC, Lomonosova E, Patel JA, et al. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by N-hydroxyisoquinolinediones and related polyoxygenated heterocycles. Antiviral Res. 2017. April 24;143:205–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards TC, Mani N, Dorsey B, et al. Inhibition of HBV replication by N-hydroxyisoquinolinedione and N-hydroxypyridinedione ribonuclease H inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 2019. February 12;164:70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tavis JE, Lomonosova E. The Hepatitis B Virus Ribonuclease H as a Drug Target. Antiviral Res. 2015;118:132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber AD, Michailidis E, Tang J, et al. 3-Hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-Diones as Novel Hepatitis B Virus Antivirals Targeting the Viral Ribonuclease H. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017. June;61(6):e00245–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu G, Villa JA, Donlin M, et al. Hepatitis B virus genetic diversity has minimal impact on sensitivity of the viral ribonuclease H to inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 2016. September 28;135:24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lomonosova E, Zlotnick A, Tavis JE. Synergistic Interactions between Hepatitis B Virus RNase H Antagonists and Other Inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017. March;61(3):e02441–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long KR, Lomonosova E, Li Q, et al. Efficacy of hepatitis B virus ribonuclease H inhibitors, a new class of replication antagonists, in FRG human liver chimeric mice. Antiviral Res. 2018. January;149:41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This reports efficacy of two chemotypes of HBV RNaseH inhibitors in a mouse model of HBV infection.

- 16.Himmel DM, Maegley KA, Pauly TA, et al. Structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with the inhibitor beta-Thujaplicinol bound at the RNase H active site. Structure. 2009;17(12):1625–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen AY, Adamek RN, Dick BL, et al. Targeting Metalloenzymes for Therapeutic Intervention. Chem Rev. 2019. September 7;119:1323–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]