Abstract

The goals of this research were to characterize suicidal behavior among a cohort of pregnant Peruvian women and identify risk factors for transitions between behaviors. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview suicide questionnaire was employed to assess suicidal behavior. Discrete-time survival analysis was used to study the cumulative age-of-onset distribution. The hazard function was calculated to assess the risk of onset of each suicidal behavior. Among 2062 participants, suicidal behaviors were endorsed by 22.6% of participants; 22.4% reported a lifetime history of suicidal ideation, 7.2% reported a history of planning, and 6.0% reported attempting suicide. Childhood abuse was most strongly associated with suicidal behavior, accounting for a 2.57-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation, nearly 3-fold increased odds of suicide planning, and 2.43-fold increased odds of suicide attempt. This study identified the highest prevalence of suicidal behavior in a population of pregnant women outside the USA. Diverse populations of pregnant women and their patterns of suicidal behavior transition must be further studied. The association between trauma and suicidal behavior indicates the importance of trauma-informed care for pregnant women.

Keywords: Peru, Pregnant, Risk assessment, Suicide

Introduction

Suicide is a leading cause of global mortality, claiming more than 800,000 lives worldwide annually (WHO 2014). While it is difficult to know when it will occur, the strongest predictor of suicide is suicidal behavior (WHO 2014). Suicidal behavior consists of suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts. Transitions from ideation to planning and from planning to attempts occur most often within the first year of developing the behavior (Nock et al. 2012). Impulsive attempts, those that are not preceded by ideation or planning, are more likely to be carried out with lower intent to die, using less lethal and more available means Rimkeviciene et al. 2015). For this reason, suicidal ideation has become a focus of research.

The World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys conducted by the World Health Organizaiton (WHO) found that the global prevalence of suicidal ideation in the general population was estimated to be 9.2% (Nock et al. 2008). While pregnancy has been previously thought to be protective against suicidal behavior (Appleby 1991), recent findings suggest that this is not always true, indicating that the prevalence of suicidal ideation in pregnancy may be as high as 33% (Gelaye et al. 2016; Newport et al. 2007), with variability depending on the assessment instrument used.

Most studies of suicidal behavior during pregnancy have measured suicidal ideation as part of an assessment of depression, rather than assessing it separately. Findings vary considerably depending on the instrument used. Previous studies have used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screening (EPDS). Studies comparing the BDI with the HRSD have found that the BDI estimates a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation (29%) than the HRSD (17%) (Gelaye et al. 2016; Newport et al. 2007).

In the general population, risk factors for suicidal behavior include female gender, young age, limited education, being unmarried, as well as psychiatric comorbidity, exposure to childhood adversity, and intimate partner violence (Devries et al. 2011; Nock et al. 2012). Similar risk factors are seen in pregnancy. Women who are unmarried, have low educational attainment, and whose pregnancies were not planned or desired face elevated risk of suicidal ideation during pregnancy (Gelaye et al. 2016). Additional risk factors include a history of childhood abuse, intimate partner violence, and comorbid psychiatric illness (Gelaye et al. 2016; Newport et al. 2007; Zhong et al. 2016). These common factors have been identified across North and South America, Europe, and Asia (Gelaye et al. 2016).

While pregnant women are more likely to experience suicidal ideation than the general population, they are less likely to attempt suicide (Appleby 1991; Gelaye et al. 2016; Newport et al. 2007; Nock et al. 2008). Thus, understanding which subset of pregnant women with suicidal ideation are at risk for attempting suicide is essential for delivering effective preventive care. However, transitions among suicidal behaviors in pregnant women have not been well-characterized. Recently, our group reported that in Lima, Perú, the prevalence of suicidal ideation ranges from 9 to 16%, depending on the screening instrument used (Zhong et al. 2014). The goals of this research will be to characterize suicidal behavior among this cohort of pregnant Peruvian women and identify risk factors for transitions between behaviors. To achieve this, we used the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) suicide questionnaire, which has been well-validated across diverse populations. We chose this instrument because it was designed specifically for the assessment of suicidal behavior and transitions between behaviors.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Participants in this cross-sectional study were women who received prenatal care at the Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal (INMP) from October 2014 through November 2015 and who enrolled in the ongoing Pregnancy Outcomes, Maternal and Infant Cohort Study (PrOMIS) during the second wave of recruitment. The INMP is the primary reference establishment for maternal and perinatal care operated by the Ministry of Health of the Peruvian Government. It serves low-income women, most of whom are publicly-insured. In 2015, 18,512 women gave birth at INMP. Eligible participants were pregnant women who were at least 18 years of age, initiated prenatal care prior to 16 weeks of gestational age, and could speak and read Spanish. Pregnant women were excluded if they had intellectual disabilities, twins, fetal malformation, or a history of chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, sepsis, or renal failure. All participants provided written informed consent prior to interview. The institutional review boards of the INMP, Lima, Peru and the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Office of Human Research Administration, Boston, MA, approved all procedures used in this study.

Our study population is derived from the PrOMIS cohort. During the study period, 2068 participants completed the structured interview, approximately 81% of eligible women who were approached. Details of the study setting and data collection procedures have been described previously (Barrios et al. 2015). Briefly, each participant was interviewed in a private setting at INMP by trained research personnel using a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was used to elicit information regarding maternal sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics, histories of childhood abuse and intimate partner violence, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD, and psychosis-like experiences. Six participants were excluded from the analysis described because there was information missing from their suicidal behavior assessments. The final analysis included 2062 participants.

Measures

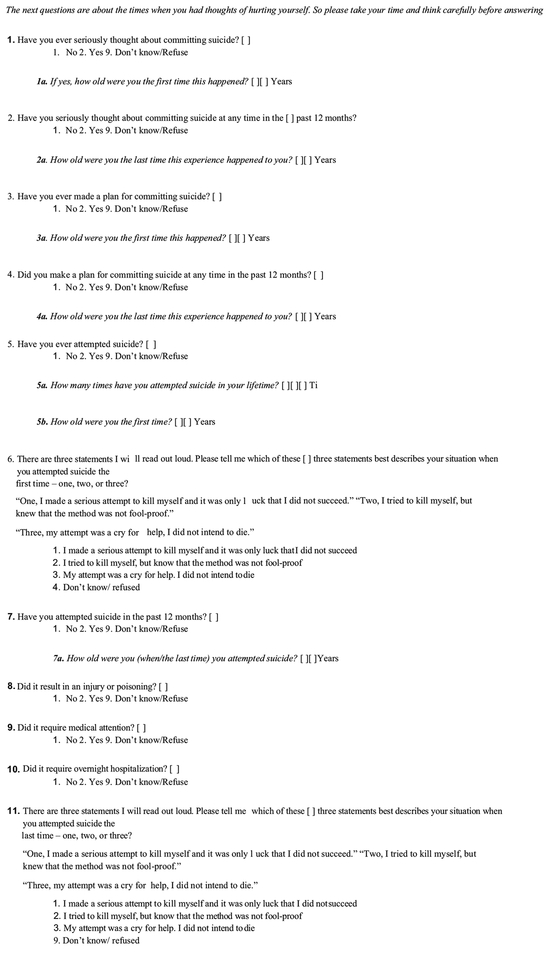

The Suicide Questionnaire from the WHO CIDI was used to assess suicidal behavior (see Fig. 1). This questionnaire was used to obtain data about suicide in the WMH Surveys (Kessler and Ustun 2004). It consists of 11 questions that assess the lifetime prevalence and age of onset of suicidal behaviors. All study personnel were trained on interviewing skills, contents of the questionnaire, and ethical conduct of human subject research (including issues of safety and confidentiality). Interviewers received structured training on administration of the CIDI questionnaire. The training program was similar to the one that one of the co-authors (BG) had attended at the Social Survey Institute at the University of Michigan (WHO Training Center). In addition to the structured training course for the interviewers, item-by-item description of questionnaires and role-plays were used. To ensure highest quality of data collection, while interviewers were in the field, they were provided strict on-site supervision and support.

Fig. 1.

Suicide Questionnaire from WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)

Covariates

Maternal sociodemographic and other characteristics were categorized as follows: age (18–19, 20–29, 30–34, and ≥ 35 years); educational attainment (≤ 6, 7–12, > 12 completed years of schooling); maternal ethnicity (Mestizo vs. others); marital status (married/living with partner vs. others); employment during pregnancy (employed vs. not employed); access to basics, including food and medical care (very hard/hard/somewhat hard vs. not very hard); parity (multiparous vs. nulliparous); planned pregnancy (yes vs. no); early pregnancy body mass index (BMI); gestational age at interviews (weeks); lifetime history of intimate partner violence (yes vs. no); and lifetime history of childhood abuse (yes vs. no).

Data analysis

We first examined the frequency distributions of maternal characteristics according to engagement in suicidal behavior. We reported mean scores and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. We evaluated the associations between maternal characteristics and suicidal behaviors by calculating odds ratios and confidence intervals. Discrete-time survival analysis was used to study the cumulative age-of-onset distribution of suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts (Efron 1988). The hazard function was calculated to assess the risk of onset of each suicidal behavior at discrete-time intervals. Subgroup analysis was then performed to characterize transitions between behaviors. Conditional, cumulative speed of onset was calculated for suicide planning among ideators, suicide attempting among ideators without a plan, and suicide attempting among ideators with a plan. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute 2016) and R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2015). The level of statistical significance was set at p values < 0.05, and all tests were two-tailed.

Results

Among 2062 participants, suicidal behaviors were endorsed by 22.6% of participants (N = 466); 22.4% (N = 461) reported a lifetime history of suicidal ideation, 7.2% (N = 149) reported a history of planning, and 6.0% (N = 124) reported attempting suicide. Selected sociodemographic and reproductive characteristics of participants by suicidal behavior are presented in Table 1. Among participants with no suicidal behaviors, the mean age was 27.8 years (SD 6.3 years). The majority were Mestizo (80.3%), married (83.2%), and with > 12 years of education (54.8%). Half of participants were employed. Difficulty accessing basic needs, including food, was reported by 41.5% of participants, and difficulty accessing medical care was reported by 39.5%. A total of 54.1% had previously given birth; 61.3% of pregnancies were unplanned. These demographic characteristics were overall similar among women who had engaged in suicidal behaviors.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics according to types of suicidal behavior among pregnant women, Lima, Peru (N = 2062)

| Characteristics | No suicidal behavior (N = 1596) |

Suicide ideation (N = 461) |

Suicide plan (N = 149) |

Suicide attempt (N = 124) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age (years)a | 27.8 (6.3) | 28.3 (6.3) | 28.5 (6.5) | 28.2 | (6.7) | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 18–19 | 103 | 6.5 | 27 | 5.9 | 10 | 6.7 | 10 | 8.1 |

| 20–29 | 897 | 56.2 | 246 | 53.4 | 77 | 51.7 | 64 | 51.6 |

| 30–34 | 322 | 20.2 | 108 | 23.4 | 32 | 21.5 | 25 | 20.2 |

| ≥ 35 | 274 | 17.2 | 80 | 17.4 | 30 | 20.1 | 25 | 20.2 |

| Education (years) | ||||||||

| ≤ 6 | 20 | 1.3 | 6 | 1.3 | 2 | 1.3 | 3 | 2.4 |

| 7–12 | 696 | 43.6 | 180 | 39.0 | 64 | 43.0 | 47 | 37.9 |

| ≥ 12 | 875 | 54.8 | 272 | 59.0 | 81 | 54.4 | 72 | 58.1 |

| Mestizo ethnicity | 1281 | 80.3 | 374 | 81.1 | 114 | 76.5 | 103 | 83.1 |

| Married/living with a partner | 1328 | 83.2 | 374 | 81.1 | 114 | 76.5 | 93 | 75.0 |

| Employed | 798 | 50.0 | 221 | 47.9 | 62 | 41.6 | 51 | 41.1 |

| Difficulty paying for basics | ||||||||

| Very hard/hard/somewhat hard | 663 | 41.5 | 223 | 48.4 | 66 | 44.3 | 64 | 51.6 |

| Not very hard | 927 | 58.1 | 236 | 51.2 | 81 | 54.4 | 59 | 47.6 |

| Difficulty paying for medical care | ||||||||

| Very hard/hard/somewhat hard | 630 | 39.5 | 207 | 44.9 | 73 | 49.0 | 58 | 46.8 |

| Not very hard | 950 | 59.5 | 251 | 54.4 | 74 | 49.7 | 65 | 52.4 |

| Nulliparous | 732 | 45.9 | 206 | 44.7 | 60 | 40.3 | 49 | 39.5 |

| Planned pregnancy | 617 | 38.7 | 166 | 36.0 | 54 | 36.2 | 45 | 36.3 |

| Early pregnancy measured BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||||

| < 18.5 | 33 | 2.1 | 6 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.8 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 722 | 45.2 | 208 | 45.1 | 63 | 42.3 | 54 | 43.5 |

| 25–29.9 | 613 | 38.4 | 160 | 34.7 | 57 | 38.3 | 45 | 36.3 |

| >30 | 216 | 13.5 | 79 | 17.1 | 27 | 18.1 | 23 | 18.5 |

| Gestational age (weeks) at interviewa | 7.8 (3.3) | 7.9(3.6) | 8.6(4.1) | 8.9 (4.5) | ||||

| Childhood abuse | 542 | 34.0 | 273 | 59.2 | 99 | 66.4 | 78 | 62.9 |

| Lifetime intimate partner violence | 349 | 21.9 | 155 | 33.6 | 57 | 38.3 | 46 | 37.1 |

| PHQ-9a | 6.5 (4.1) | 8.5 (4.5) | 9.4 (5.0) | 9.4 (5.2) | ||||

Mean (standard deviation)

Due to missing data, percentages may not add up to 100%

The associations between these characteristics and suicidal behaviors are presented in Table 2. Being unmarried was associated with planning (OR = 1.53; 95%CI 1.01–2.27) and attempting suicide (OR = 1.66; 95%CI 1.07–2.52). Difficulty accessing medical care was associated with suicidal ideation (OR = 1.24; 95%CI 1.01–1.53) and planning (OR = 1.49; 95%CI 1.06–2.09). Three characteristics were statistically significantly associated with all three behaviors: difficulty accessing food, history of childhood abuse, and intimate partner violence. Childhood abuse was most strongly associated with suicidal behavior; it accounted for a 2.57-fold increased odds (OR = 2.57; 95%CI 2.08–3.17) of suicidal ideation, nearly 3-fold increased odds (OR = 2.99; 95%CI 2.13–4.25) of suicide planning, and 2.43-fold increased odds (OR = 2.43; 95%CI 1.69–3.52) of suicide attempt.

Table 2.

Associations of sociodemographic characteristics with suicidal behavior among pregnant women, Lima, Peru

| Characteristics | OR (95%CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide ideationa (N = 461) |

Suicide plana (N = 149) |

Suicide attempta (N = 124) |

|

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–19 | 0.96 (0.60, 1.47) | 1.13 (0.54,2.16) | 1.36 (0.64,2.62) |

| 20–29 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 30–34 | 1.22 (0.94, 1.58) | 1.16 (0.74, 1.77) | 1.09 (0.66, 1.74) |

| ≥ 35 | 1.06 (0.80, 1.41) | 1.28 (0.81, 1.97) | 1.28 (0.78,2.04) |

| Education (years) | |||

| ≤ 6 | 0.97 (0.35, 2.29) | 1.08 (0.17,3.79) | 1.82 (0.42,5.48) |

| 7–12 | 0.83 (0.67, 1.03) | 0.99 (0.70, 1.40) | 0.82 (0.56, 1.20) |

| > 12 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Mestizo ethnicity | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Other | 0.95 (0.73, 1.23) | 1.26 (0.83, 1.85) | 0.83 (0.50, 1.33) |

| Married/living with a partner | |||

| Yes | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| No | 1.16 (0.88, 1.51) | 1.53 (1.01, 2.27) | 1.66 (1.07,2.52) |

| Employed during pregnancy | |||

| Yes | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| No | 1.09 (0.88, 1.34) | 1.40 (1.00, 1.98) | 1.43 (0.99,2.08) |

| Difficulty paying for basics | |||

| Very hard/hard/somewhat hard | 1.32 (1.07,1.63) | 1.72 (1.22, 2.42) | 1.52 (1.05,2.19) |

| hard Not very hard | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Difficulty paying for medical care | |||

| Very hard/hard/somewhat hard | 1.24 (1.01,1.53) | 1.49 (1.06, 2.09) | 1.35 (0.93, 1.94) |

| Not very hard | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Parity | |||

| Nulliparous | 0.95 (0.77, 1.17) | 0.79 (0.56, 1.12) | 0.77 (0.53, 1.12) |

| Multiparous | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Planned pregnancy | |||

| No | 1.13 (0.91, 1.40) | 1.11 (0.79, 1.59) | 1.11 (0.76, 1.64) |

| Yes | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Early pregnancy measured BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| < 18.5 | 0.63 (0.24, 1.42) | 0.35 (0.02, 1.65) | 0.41 (0.02, 1.94) |

| 18.5–24.9 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 25–29.9 | 0.91 (0.72, 1.14) | 1.07 (0.73, 1.55) | 0.98 (0.65, 1.48) |

| >30 | 1.27 (0.94, 1.71) | 1.43 (0.88,2.28) | 1.42 (0.84,2.34) |

| Childhood abuse | |||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 2.57 (2.08, 3.17) | 2.99 (2.13, 4.25) | 2.43 (1.69,3.52) |

| Lifetime intimate partner violence | |||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.81 (1.44, 2.27) | 2.21 (1.55, 3.13) | 2.11 (1.43, 3.08) |

Reference group: women without any suicidal behavior (N = 1596) 95% CI

Figure 2 depicts the distribution and overlap of suicide behaviors among participants. There were 466 participants who endorsed one or more suicidal behaviors. Three hundred two participants endorsed suicidal ideation alone. One hundred nine participants endorsed suicidal ideation, planning, and attempting. Forty endorsed suicidal ideation and planning but reported no history of attempting suicide. Ten participants endorsed suicidal ideation and attempting without planning, and five participants reported a history of suicide attempts without suicidal ideation or planning.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of lifetime suicide ideation (n = 461), plan (n = 149), and attempt (n = 124) among pregnant women, Lima, Peru

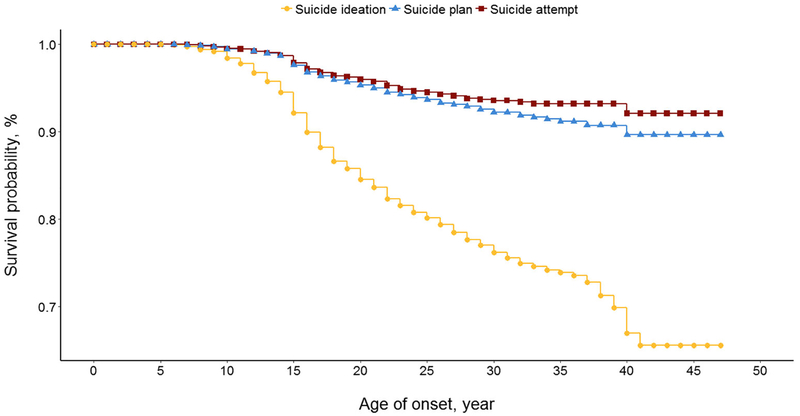

Figure 3 shows the survival curve for age-of-onset for first occurrence of suicidal ideation, planning, and attempting. The age of onset for each behavior is depicted as a hazard function in Fig. 4. All behaviors have an initial peak at age 15 and a second peak at age 40. Figure 5 illustrates the conditional cumulative likelihood of reporting the first onset of planning among ideators and attempting among ideators with and without a plan. Within a year, 28.7% of ideators had made a plan, 83.8% of those with a plan had made a suicide attempt, and 7.7% of those with ideation but no plan had attempted suicide.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative age-of-onset distribution of the lifetime suicide ideation, plan, and attempt among pregnant women, Lima, Peru (N = 2057)

Fig. 4.

Hazard function of first onset of suicide ideation, plan, and attempt among pregnant women, Lima, Peru (N = 2057)

Fig. 5.

Conditional, cumulative speed of onset of suicide plan among ideators (n = 149), suicide attempt among ideators without a plan (n = 10), and suicide attempt among ideators with a plan (n = 109) among pregnant women, Lima, Peru

Discussion

The results of this study confirm a high prevalence of suicidal behavior among pregnant women (22.6%), including ideation(22.4%), plan (7.2%), and attempt (6.0%). These findings are consistent with other studies of pregnant women, which have found the prevalence of suicidal behavior to be between 3 and 33% (Gelaye et al. 2016; Melville et al. 2010; Newport et al. 2007). However, prevalence estimates above 20% have only been identified within the USA; the prevalence of 22.6% in this Peruvian population is higher than what has been reported in other non-US samples of pregnant women (Gelaye et al. 2016).

It is also significant that 69% of women in this population report a history of childhood abuse (Barrios et al. 2015), as childhood adversity is associated with the development of suicidal behavior later in life (Gelaye et al. 2016; Newport et al. 2007; Zhong et al. 2016). This is likely a contributing factor to the high rates of suicidal behavior in this population.

The WHO multi-country study on women’s health established a clear link between exposure to violence, including childhood abuse, intimate partner violence, and non-partner violence, and suicidal behavior (Devries et al. 2011). A previous study of the PrOMIS cohort identified the link between child abuse and suicidal ideation (Q. Y. Zhong et al. 2016). The current study found that child abuse was the leading risk factor for suicidal behavior, underscoring the need for trauma-informed care during pregnancy for women with this history.

The WMH Surveys found an initial peak in suicidal behavior during adolescence, followed by a decline with age (Nock et al. 2012). Another study assessed women in Europe and found a peak during the peri-menopausal period (Usall et al. 2009). Our study also found a peak in adolescence, at age 15, followed by a second peak at age 40. In this sociocultural context, most women have children in their 20s and early 30s. The peaks in suicidal behavior in this study population are seen at ages that fall outside the usual range for pregnancy. Other studies have reported that unplanned pregnancy is a risk factor for suicidal behavior (Gelaye et al. 2016); our study did not find this. An increase in suicidal behavior at age 40 could be explained by the fact that at this age, many women in this study population are already grandmothers, and having a child is not culturally normative. It may be that participants underreported when pregnancies were unplanned due to shame or stigma. However, the rate of unplanned pregnancy in this population is consistent with what has been reported in other studies (Gelaye et al. 2016; Wilson et al. 1996; World Bank 2016). It is also possible that even in cases when the pregnancies were planned, being pregnant at an age outside the usual range is a source of stress; adolescence and advanced maternal age have been found to be associated with perinatal depression (Garcia-Blanco et al. 2017; Raisanen et al. 2014). Furthermore, women who become pregnant during adolescence or at an advanced maternal age are more likely to experience complications, which could lead to increased suicidal behavior (Melville et al. 2010; Newport et al. 2007).

This study also found that risk of transition among suicidal behaviors is highest in the first year of onset. More than a quarter of participants made a plan within a year of developing suicidal ideation, and more than 80% attempted suicide within a year of making a plan. These findings are consistent with the findings of the WMH Surveys in non-pregnant populations (Nock et al. 2008; Nock et al. 2012). Collectively, these findings suggest that suicide prevention depends on identifying suicidal ideation since a third of individuals who commit suicide die from their first attempt. Other studies of transitions among suicidal behaviors in pregnant women are lacking.

This study had a number of limitations. First, suicidal behaviors were assessed based upon retrospective self-report, which makes the data subject to under-reporting and recall bias. Also, this meant that reports of suicidal behavior at other times prior to the pregnancy were included, so the data does not exclusively represent suicidal behavior in pregnancy. Second, while psychiatric symptoms were assessed by self-report using the PHQ-9 and PCL-C, diagnostic interviews were not performed. Thus, there was no definitive information about psychiatric diagnoses included in these analyses. Finally, results from our hospital-based study may not be applicable to other populations of pregnant women because most women seeking care at INMP are low-income and may have high-risk pregnancies. This study provides an initial data point in the assessment of suicidal behaviors in diverse populations of pregnant women.

Further research is needed to characterize the extent and variability of the problem and establish reliable screening tools for suicidal behavior. Our study population had a higher prevalence of suicidal behavior than has been previously documented in pregnant women outside the USA. Existing data also show that the prevalence of these behaviors varies widely in distinct regions across the world, suggesting that it will be important to examine suicidal behaviors in diverse settings. Given that pregnant women have a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and a lower prevalence of suicide attempts than the general population (Appleby 1991; Gelaye et al. 2016), their patterns of transitioning among suicidal behaviors should be further studied to prevent negative health consequences for themselves as well as the next generation.

Suicide in pregnancy not only has catastrophic consequences for the woman and her unborn child; maternal depression and suicide have severe negative consequences for off-spring (Geulayov et al. 2014; Hammerton et al. 2016; Lahti et al. 2017; Plant et al. 2013). Particularly in low-resource settings, for many young women, pregnancy is their first contact with the healthcare system and is thus an opportunity for identifying women at risk for suicide.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the dedicated staff members of Asociacion Civil Proyectos en Salud (PROESA), Peru and Instituto Materno Perinatal, Peru for their expert technical assistance with this research.

Funding This research was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health (T32-MH-093310 and R01-HD-059835). The NIH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

All participants provided written informed consent prior to interview. The institutional review boards of the INMP, Lima, Peru and the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Office of Human Research Administration, Boston, MA, approved all procedures used in this study.

Conflicts of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Appleby L (1991) Suicide during pregnancy and in the first postnatal year. BMJ 302(6769):137–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios YV, Gelaye B, Zhong Q, Nicolaidis C, Rondon MB, Garcia PJ, … Williams MA (2015). Association of childhood physical and sexual abuse with intimate partner violence, poor general health and depressive symptoms among pregnant women. PLoS One 10(1):e0116609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries K, Watts C, Yoshihama M, Kiss L, Schraiber LB, Deyessa N, … Team, W. H. O. M.-C. S. (2011). Violence against women is strongly associated with suicide attempts: evidence from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Soc Sci Med 73(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B (1988) Logistic regression, survival analysis, and the Kaplan Meier curve. J Am Sociol Assoc 83(402):414–425 [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Blanco A, Monferrer A, Grimaldos J, Hervas D, Balanza-Martinez V, Diago V, … Chafer-Pericas C (2017) A preliminary study to assess the impact of maternal age on stress-related variables in healthy nulliparous women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 78:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelaye B, Kajeepeta S, Williams MA (2016) Suicidal ideation in pregnancy: an epidemiologic review. Arch Womens Ment Health 19(5): 741–751. 10.1007/s00737-016-0646-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geulayov G, Metcalfe C, Heron J, Kidger J, Gunnell D (2014) Parental suicide attempt and offspring self-harm and suicidal thoughts: results from the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children (ALSPAC) birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53(5):509–517 e502. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerton G, Zammit S, Thapar A, Collishaw S (2016) Explaining risk for suicidal ideation in adolescent offspring of mothers with depression. Psychol Med 46(2):265–275. 10.1017/S0033291715001671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB (2004) The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 13(2):93–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti M, Savolainen K, Tuovinen S, Pesonen AK, Lahti J, Heinonen K, … Raikkonen K (2017) Maternal depressive symptoms during and after pregnancy and psychiatric problems in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 56(1):30–39 e37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville JL, Gavin A, Guo Y, Fan MY, Katon WJ (2010) Depressive disorders during pregnancy: prevalence and risk factors in a large urban sample. Obstet Gynecol 116(5):1064–1070. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f60b0a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport DJ, Levey LC, Pennell PB, Ragan K, Stowe ZN (2007) Suicidal ideation in pregnancy: assessment and clinical implications. Arch Womens Ment Health 10(5):181–187. 10.1007/s00737-007-0192-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, … Williams D (2008) Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry 192(2):98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Ono Y (2012) Suicide: Global Perspectives from the WHO World Mental Health Survey. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge [Google Scholar]

- Plant DT, Barker ED, Waters CS, Pawlby S, Pariante CM (2013) Intergenerational transmission of maltreatment and psychopathology: the role of antenatal depression. Psychol Med 43(3):519–528. 10.1017/s0033291712001298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2015) R software (Version3.1.2). Vienna, Austria [Google Scholar]

- Raisanen S, Lehto SM, Nielsen HS, Gissler M, Kramer MR, Heinonen S (2014) Risk factors for and perinatal outcomes of major depression during pregnancy: a population-based analysis during 2002–2010 in Finland. BMJ Open 4(11):e004883 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimkeviciene J, O’Gorman J, De Leo D (2015) Impulsive suicide attempts: a systematic literature review of definitions, characteristics and risk factors. J Affect Disord 171:93–104. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute (2016) SAS Analytics Pro 9.4. SAS Institute Inc., Cary [Google Scholar]

- Usall J, Pinto-Meza A, Fernandez A, de Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Alonso J, … Haro JM (2009) Suicide ideation across reproductive life cycle of women. Results from a European epidemiological study. J Affect Disord, 116(1–2):44–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2014) Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/. Accessed 1 Feb 2018

- Wilson LM, Reid AJ, Midmer DK, Biringer A, Carroll JC, Stewart DE (1996) Antenatal psychosocial risk factors associated with adverse postpartum family outcomes. Cmaj 154(6):785–799 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank (2016) Adolescent Fertility Rates. Retrieved from Washington, DC: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.ADO.TFRT [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Q, Gelaye B, Rondon M, Sanchez SE, Garcia PJ, Sanchez E, … Williams MA (2014) Comparative performance of patient health Questionnaire-9 and Edinburgh postnatal depression scale for screening antepartum depression. J Affect Disord, 162:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong QY, Wells A, Rondon MB, Williams MA, Barrios YV, Sanchez SE, Gelaye B (2016) Childhood abuse and suicidal ideation in a cohort of pregnant Peruvian women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 215(4): 501 e501–501 e508. 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.04.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]