Abstract

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is essential for proper neuronal function, homeostasis, and protection of the central nervous system (CNS) microenvironment from blood-borne pathogens and neurotoxins. The BBB is also an impediment for CNS penetration of drugs. In some neurologic conditions, such as epilepsy and brain tumors, overexpression of P-glycoprotein, an efflux transporter whose physiological function is to expel catabolites and xenobiotics from the CNS into the blood stream, has been reported. Recent studies reported that overexpression of P-glycoprotein and increase in its activity at the BBB drives a progressive resistance to CNS penetration and persistence of riluzole, the only drug approved thus far for treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), rapidly progressive and mostly fatal neurologic disease. This review will discuss the impact of transporter-mediated pharmacoresistance for ALS drug therapy and the potential therapeutic strategies to improve the outcome of ALS clinical trials and efficacy of current and future drug treatments.

Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, blood-brain barrier, P-glycoprotein, pharmacoresistance, riluzole

INTRODUCTION

The complexity of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) etiology and the pathologic changes in the blood–brain barrier (BBB) have contributed significantly in limiting the development of a successful pharmacotherapy. With the discovery of ALS-linked genes, genetic mutations have been discovered in up to 20% of apparent sporadic and 60% of familial ALS cases (1). Clinically, ALS is classified as an upper and lower motor neuron disease. There are also atypical ALS phenotypes, which include the “pure” lower motor neuron (LMN)-type progressive muscle atrophy, pure upper motor neuron (UMN)-type primary lateral sclerosis, and predominant bulbar palsy (2). Several mechanisms have been proposed to cause ALS disease, including glutamate excitotoxicity, neuroinflammation, dysfunction of mitochondria, aberrant protein aggregation, and oxidative stress, which led to the launching of multiple preclinical and clinical trials. However, only one drug, riluzole, was found to be modestly effective in slowing down the progression of ALS (3). The lack of suitable biomarkers for early detection and diagnosis has also negatively impacted the design of clinical trials, possibly decreasing the chance of success. Failure to find new, more effective drugs may also be attributed to the inability of the investigated drugs to gain access to the brain in therapeutic concentrations due to the activity of multidrug efflux transporters at the BBB (pharmacoresistance) (4). The BBB has been considered a major obstacle for central nervous system (CNS) penetration and persistence of bioactive drugs. Some neurologic diseases, such as epilepsy, brain tumors, and more recently ALS, have been associated with overexpression of P-glycoprotein (permeability-glycoprotein, P-gp) at the endothelial cells of the BBB that hinders even more the access of drugs to CNS tissues. Hence, it becomes a necessity to overcome P-gp mediated multidrug resistance (MDR) to improve the efficacy of clinically prescribed CNS targeting drugs.

THE BLOOD-BRAIN BARRIER

The BBB separates blood components from the CNS. Integrity of the barrier is essential for proper neuronal function, maintenance of brain microenvironment, and protection from blood-borne pathogens and toxins (5). The BBB consists of a physical barrier, formed by microcapillary endothelium that is held firmly together by tight junctions (TJs), and a transport barrier, formed by presence of several efflux transporters and vesicular systems. This system limits the paracellular diffusion of polar molecules, yet allows a strict controlled transport of nutrients, solutes, and circulating immune cells into the brain.

Drug Efflux Transporters

To enter the CNS from the peripheral circulation, most drugs and solutes have to traverse the BBB, while paracellular permeability is limited by the TJ of capillary endothelium (6). Endothelial cells of the brain capillaries are considered major physical blocks that form the BBB together with the help of cells of the neurovascular unit including astrocytes, neurons, and pericytes. Cells of the neurovascular unit work together to support the BBB and to contribute in regulating its structural as well as functional integrity (7).

Although lipid soluble and low molecular weight compounds may readily diffuse across the BBB, most of those compounds are ultimately limited by specialized efflux transport systems. The entry and persistence of many compounds in the CNS are restricted by ATP binding cassette (ABC) efflux transporters, which are active efflux pumps that use ATP as a source of energy to shuttle endogenous and exogenous molecules across the BBB (2). Most relevant drug efflux transporters include P-gp (ABCB1), multidrug resistance-associated proteins MRPs (ABCCs), and the breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2) (2). P-Glycoprotein. P-gp, the first identified MDR protein (8), is a 170-kDa transporter, highly expressed at the BBB, and localizes to the luminal membrane of the brain endothelial cells (BEC) (9,10). P-gp regulates brain removal of various biomolecules such as cholesterol, lipid, glucocorticoid, and peptides (11). In addition, P-gp has broad substrate specificity which makes it capable of hindering the brain access of many CNS-active drugs, such as the human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors including indinavir, nelfinavir, and saquinavir (12).

In humans, two isoforms (1 and 2) of P-gp are present. Isoform 1 is encoded by the MDR1 gene, which is expressed at the BBB, while isoform 2 is encoded by MDR2/MDR3 genes and it is expressed predominantly in canaliculi of hepatocytes (13). In rodents, mdr1a and mdr1b genes encode P-gp isoform 1. mdr1a is expressed in brain capillaries, whereas mdr1b is expressed exclusively in brain parenchyma (14). Substrate specificity of both isoforms, although partly overlapping, is different. Due to the expression of P-gp at the lumen of BEC, P-gp substrates entering the brain through capillary lumen are largely effluxed back into the blood, and thus, their brain access is strikingly reduced (13). P-gp, despite being predominantly localized at the plasma membrane, is also expressed in intracellular compartments, such as cytoplasmic vesicles, plasmalemmal vesicles, and nuclear envelope (15,16). P-gp-containing cytoplasmic vesicles concentrate drugs into the lumen of the vesicles.

Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein.

Multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRPs) are nine members that belong to the subfamily MRP/CFTR of the 48 human ABC transporters’ family. Unlike P-gp whose substrates are unconjugated and cationic, the majority of substrates for MRPs (MRP1 or MRP2) are anionic. However, due to the broad specificity of both P-gp and MRPs, there is a substrate overlap for both transporter families (12,17,18). Like P-gp, MRPs are also expressed at the BBB. However, unlike P-gp whose expression is restricted at the apical membrane of capillary endothelium, MRPs are expressed both apically (MRP2 and MRP4) and basolaterally (MRP1, MRP3, and MRP5) (12,17).

Breast Cancer Resistance Protein.

Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), subfamily G member 2 (ABCG2), is an ABC efflux transporter discovered in a drug-resistant breast cancer cell line. Like P-gp, BCRP is expressed at various barrier tissues, suggesting that both transporters similarly protect various tissues from harmful xenobiotics (12). In the brain, the expression of BCRP has been detected at the apical side of capillary endothelium of different animal species such as, pigs, mice, and humans (12,19,20). In humans, mRNA transcripts of BCRP are more abundantly expressed at the BBB than that of P-gp or MRP1 (21). BCRP has been suggested to have a role in regulating drug distribution into the brain. Inhibition of BCRP at the BBB was shown to increase brain penetration of prazosin and mitoxantrone in mdr1a knockout mice (19). In support of the similarities in tissue expression and protective function of BCRP and P-gp, BCRP expression was shown to increase by 3-fold in capillary endothelium of mdr1a knockout mice, indicating a compensatory role played by BCRP (19).

DYSFUNCTION OF BBB IN ALS

Alterations in Brain Vasculature in ALS

Proper function of the brain vasculature is essential to maintain normal microenvironment required for optimal neural cells function (22). However, in disease condition, the BBB may undergo structural and functional deteriorations that lead to or exacerbate neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Studies reported disruption of the BBB integrity and function in many neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis, stroke, epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease, and ALS (1,23).

A compromised BBB in ALS patients has been hypothesized early in 1980s (24). Quantitative and immunofluorescence analyses of brain tissue and CSF proteins revealed infiltration and deposition into the CNS of blood-borne molecules, suggesting damaged BBB (24,25). Impairments in the BBB of the SOD1-G93A mouse model of ALS as well as in microvessels of post-mortem brain and spinal cord tissues of ALS patients have been reported (1), including endothelial cell degeneration, capillary leakage, perivascular edema, downregulation of TJ proteins, and microhemorrhages (1). In the SOD1-G93A mouse, the blood-spinal cord barrier (BSCB) is disrupted most likely because of downregulation of the TJ proteins ZO-1, occludin and claudin-5. This likely resulted in microhemorrhages and the associated release of neurotoxic hemoglobin-derived products, reductions in microcirculation, and hypoperfusion (26). These changes precede some disease events such as neuroinflammation and motor neuron death, suggesting that BBB alterations may contribute to disease initiation. However, another study in a rat model of ALS reported dysfunction in BBB and BSCB by showing distribution of Evans blue dye into spinal cord and brain stem of symptomatic, but not asymptomatic animals, suggesting that BBB alterations occurred as a consequence of disease (27). Modifications occur also at the transport level, which included overexpression of P-gp and BCRP mainly in spinal cord microcapillaries (28).

The BBB in ALS suffers from multiple injuries and downregulation in major TJ proteins that may eventually lead to increased paracellular permeability of the BBB to systemic blood components and circulating drugs. Qosa and colleagues studied changes in paracellualr permeability in an in vitro model of the ALS BBB and found that increased paracellular permeability of the BBB to Na fluorescein (a substance that does not undergo active transport) did not increase the permeability of a P-gp substrate, LD800 (29). The authors concluded that P-gp upregulation presumably reduced leakage of P-gp substrates across dysfunctional BBB model of ALS (29). Interestingly, similar observations were reported in other CNS diseases. For example, in epilepsy, the TJs are dysfunctional causing a BBB leakage and impaired neuronal function, yet the transport across the BBB is still restricted by P-gp causing drug resistance (30). Similarly in stroke, the TJs are disrupted and the BBB is dysfunctional; however, those changes are associated with P-gp upregulation and limited brain permeability of CNS-active drugs that are P-gp substrates (28,31). Nonetheless, it is advisable that whenever studying, P-gp activity in BBB cellular and animal models of CNS diseases should be included in paracellular markers (e.g., inulin, sucrose, and sodium fluorescein) to account for paracellular leakage and accurately measure the contribution of efflux transporters in drug transport across the BBB.

Evidence of Transporter-Mediated Pharmacoresistance in ALS

Transporter-mediated pharmacoresistance has attracted attention over the last decade in neurological diseases like epilepsy, in which P-gp efflux transporter at the brain endothelium of the BBB appears to be a major player. This multidrug efflux transporter has also been implicated in pharmacoresistance in other non-neurologic diseases, such as cancer and HIV (32). Due to the ability of P-gp to prevent a broad range of drugs from accessing the CNS, a disease condition in which P-gp is downregulated (e.g., AD and PD) will increase the brain penetration of systemic drugs and potentially result in adverse effects (28). On the other hand, a disease condition in which P-gp expression is increased at the BBB (e.g., epilepsy, stroke, and ALS) will decrease the brain penetration of CNS-active drugs and, therefore, limit their therapeutic benefits (28).

An early study by Boston and colleagues suggested the occurrence of P-gp-mediated pharmacoresistance in the SOD1-G93A mouse model of ALS (33). The authors screened a library of 1040 FDA-approved drugs to find candidates that enhance glutamate uptake, aiming at controlling glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity in ALS. They reported that nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA), an anti-inflammatory molecule and inhibitor of lipoxygensases, increased glutamate uptake in vitro in MN-1 cells and chronically in vivo in non-transgenic, wild-type mice. However, when NDGA was given to the SOD1-G93A transgenic mice, it failed to sustain, over time, the increase in glutamate uptake. Interestingly, the same study also found in these mice that an upregulation of P-gp expression in the spinal cord microcapillary endothelium starts at disease onset. Based on these observations, it was hypothesized that the lack of a sustained effect of NDGA in the SOD1-G93A mice could be due to increased P-gp-mediated resistance to NDGA penetration into the CNS (33). Following these initial findings, the same lab further reported that protein and mRNA levels of Abcb1 and Abcg2 were selectively increased in the spinal cord and cerebral capillaries of SOD1-G93A mice models of ALS (4). Subsequently, other groups reported increased expression of P-gp, but not BCRP in the mutant SOD1-G86R mouse and SOD1-G93A rat models of ALS (34,35). P-gp overexpression may limit the ability of investigational drugs that are P-gp substrates to cross the BBB and reach the brain in therapeutic concentrations, therefore adversely impacting their efficacy. For example, riluzole, the only drug approved for treatment of ALS, is a P-gp and BCRP substrate (36). In one study by Milan and colleagues, higher brain penetration of riluzole by 2.1-fold was observed when it was co-administered with a P-gp inhibitor, minocycline, and by 1.4-fold, when administered to mdr1 knockout mice (36). Furthermore, the uptake of riluzole increased significantly after inhibition of BCRP in mdr1a (−/−) mice and BeWo cells (37). In a recent study, Jablonski and colleagues showed that double inhibition of P-gp and BCRP with elacridar increased riluzole therapeutic efficacy in SOD1-G93A ALS mice (38). Similarly, brain uptake of riluzole decreased by 70% in mutant SOD1-G86R mice (34). These observations suggest that the therapeutic efficacy of P-gp/BCRP substrates, such as riluzole, could be limited, at least partially, as a result of pharmacoresistance that develops over the course of ALS.

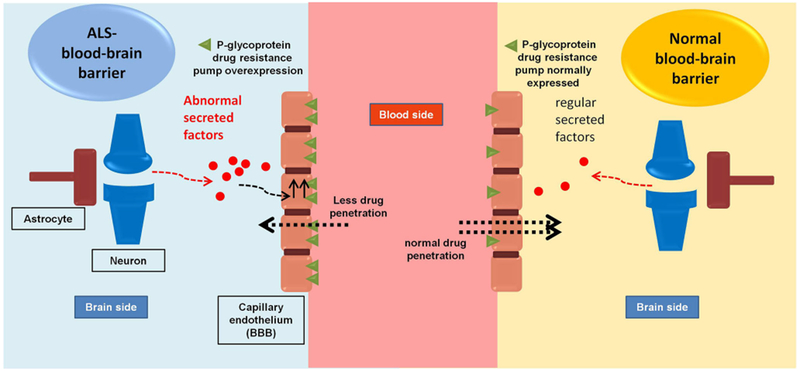

ABC transporters’ upregulation was also detected in ALS patients’ post-mortem lumbar spinal cord tissue, further suggesting the development of pharmacoresistance following disease pathology (4). Therefore, drug-transporter/drug-drug interaction may occur at the BBB level and impact brain permeability of ALS therapeutics, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Table I shows drugs that have been tested in ALS clinical trials; many of which are also P-gp substrates. The time course of P-gp upregulation in ALS patients remains however to be further investigated .

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram showing changes in P-glycoprotein expression at the BBB in ALS

Table I.

Summary of ALS disease modifying treatments in completed and ongoing clinical trials and their potential interaction with multidrug efflux transporter, P-glycoprotein

| Target | Proposed mechanism | Stage of development | Ref. | Interaction with P-gp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excitotoxicity | ||||

| Riluzole | Reduces presynaptic glutamate release | Approved | (39,40) | Substrate |

| l-Threonine | Improve glutamate metabolism | Phase 2 studies completed negative | (41) | ? |

| Talampanel | AMPA-R antagonist | Phase 2 study completed negative | (42) | ? |

| Memantine | NMDA-R non-competitive antagonist | Phase 3 study results not available | (43,44) | ? |

| Topiramate | AMPA-R antagonist and decreases glutamate release in the CNS | Phase 2/3 study completed negative | (45) | Substrate |

| Lamotrigin | Sodium channel blocker; inhibits glutamate and aspartate release | Phase 2 study add on to riluzole; active not recruiting yet | (46) | ? |

| Gabapentin | Inhibits voltage-gated calcium channels, decreases synthesis of glutamate | Phase 2 study completed negative | (47,48) | Not Substrate |

| Nimodipine | Calcium channel blocker | Phase 2 study completed negative | (49) | Substrate |

| Dextromethorphane | NMDA-R non-competitive antagonist | Phase 3 study completed negative | (50) | Substrate |

| AVP-923 (dextromethorphan/quinidine) | Not known, reported to protect cortical neurons against excitotoxicity | Phase 2 study completed negative | (51,52) | ? |

| Methylcobalamine | Increases astrocytic glutamate transporter activity | Phase 2 study completed negative Phase 2/3 studies + Phase 4 study in PBA (pseudobulbar affect) |

(53,54) (55) |

? |

| Ceftriaxone | Phase 2/3 study completed, no results Phase 2/3 study ongoing, not recruiting Phase 3 study completed negative |

(56) NCT00445172 (57) |

? | |

| Mithocondrial dysfunction | ||||

| Minocycline | Mitochondrial membrane permeability stabilizers with antioxidant, antiexcitotoxic, and antiapoptotic properties | Phase 3 study completed negative | (58) | Substrate |

| Creatine | Phase 2 studies completed negative | (59) | ? | |

| Olesoxime (TRO19622) | Phase 2/3 study completed negative | (59,60) | ? | |

| Dexpramipexole (KNS-760704) | Sustains mitochondrial bioenergetic processes | Phase 3 study completed negative | (61) | Not Substrate |

| Rasagiline | Phase 2 study completed negative | (62) | ? | |

| Tauroursodeoxycholic acid | Phase 2 study completed, positive | (63) | ? | |

| Acetyl-l-carnitine | Phase 2 study completed, negative Phase 2 study completed, no conclusions drawn about efficacy |

(64) (65) |

? | |

| Apoptosis | ||||

| TCH346 (CGP 3466B) | Blocks the GAPDH apoptotic pathway | Phase 2/3 study completed negative | (66) | ? |

| Oxidative stress | ||||

| N-Acetylcisteine, glutathione | Increase antioxidative property, free radical scavengers | Phase 2 and 3 studies completed negative | (67) | ? |

| Selegilene, Vit E, Vit C, CoQ10 | Free radical scavenger | Phase 2 study completed positive Phase 2 study completed negative |

(68) (69) |

Substrate |

| Edaravone (MCI-186) | Free radical scavenger | Phase 3 studies completed, no results available In 2015, it was approved in Japan and South Korea for the treatment of ALS by intravenous injection. |

NCT00330681; NCT00424463 |

Substrate ? |

| Treeway (TW001): oral formulation of edavarone | No data available, presumably it modifies GSH level | Phase I clinical trial completed, no results available yet | NCT00415519 | |

| EPI-589/(R)-troloxamide quinone | Phase 2 study recruiting | NCT01492686, NCT02460679 | ||

| Peroxisome | ||||

| Pioglitazone | Anti-inflammatory activity, induces transcription of peroxisome proliferation activated receptors (PPARs) | Phase 2 study completed, negative | (70) | Inhibitor |

| Neuroinflammation: astrocytes | ||||

| Arundic acid (ONO-2506) | Blocks gliosis by inhibition of S100B | Phase 2 studies, no results available | NCT00694941; NCT00403104 | ? |

| Neuroinflammation: microglia | ||||

| NP001 | Downregulate NFkB expression | Phase 2 study completed, negative | (71) NCT02794857 |

? |

| RNS60 | Phase 2 study ongoing, recruiting | NCT02525471 | ? | |

| MN-166 (ibudilast) | Inhibits phosphodiesterase-4 and phosphodiesterase-10 and macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) | Phase 1 study ongoing, recruiting | NCT02714036 | ? |

| Tocilizumab | Ab anti-IL 6 | Phase 1/2 study ongoing, recruiting Phase 2 study active, not recruiting Phase 1/2 studies completed, no conclusions drawn about efficacy Phase 2 ongoing, recruiting |

NCT02238626 (72,73) NCT02469896 |

? |

| Immunomodulation: T lymphocytes | ||||

| IL-2 | Enhances T regulatory cells expansion | Phase 2 study completed, no results available yet | NCT02059759 | ? |

| Glatiramer acetate | Generation of GA-specific T helper 2-type T cells | Phase 2 study completed, negative | (74) | ? |

| Fingolimod | Blocks T cell in the secondary lymphoid tissue | Phase 2 study completed, no results available yet | NCT01786174 | Substrate |

| Immunosuppression | ||||

| Basiliximab (mAb anti-IL2) | Inhibits activated T lymphocytes | Phase 2 study completed, no results available yet | NCT01884571 | ? |

| Methylprednisolone | Exerts a broad action in decreasing the inflammatory cycle | Phase 2 study completed, no results available yet | NCT01884571 | Substrate |

| Tacrolimus | Inhibits calcium-dependent event and T cell proliferation | Substrate | ||

| Mycophenolate mofetil | Inhibits the growth of T and B cells | Substrate | ||

| Viral infection | ||||

| Tilorone | Antiviral therapy | Phase 2 study completed, negative | (75) | ? |

| Indinavir | Antiretroviral therapies | Phase 2 study completed, negative | (76) | Substrate |

| Triumeq | Phase 1/2 study ongoing, recruiting | NCT02868580 | ? | |

| Gene therapy | ||||

| SB-509 | Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) activator | Phase 2 study completed, no results available yet | NCT00748501 | ? |

| VM202 | Stimulate release of hepatocyte growth factor HGF, which acts as a neurotrophic factor and induce angiogenesis | Phase 1/2 study completed, no results available yet | NCT02039401 | ? |

| RNA | ||||

| ISIS-SOD1RX – antisense SOD1 oligonucleotides | Lowers concentration of mutant SOD1 | Phase 1 study completed in FALS, no results available Phase 1 study ongoing, recruiting |

NCT01041222 NCT02623699 |

? |

| Proteinopathy | ||||

| Pyrimethamine | Not known, suggested a generalized reduction in protein production, related to cytotoxicity | Phase 1 study completed, no conclusions drawn about efficacy Phase 1/2 study concluded, waiting for results |

(77) NCT01041222 |

? |

| Arimoclomol | Amplifies HSP gene expression, facilitates degradation of protein aggregation | Phase 2 study completed, no results available yet Phase 2/3 study ongoing in FALS, not recruiting |

NCT00244244 NCT00706147 |

? |

| Autophagy | ||||

| Lithium carbonate | Facilitates degradation of protein aggregates | Phase 3 study completed, negative | (78) | ? |

| Growth factors | ||||

| Growth hormone | Myotrophic and systemic trophic effects | Phase 2 study completed, negative | (79) | ? |

| Erythropoietin (EPO) | Protects from motor neuron degeneration, reduces SOD1 aggregates in motor neurons | Phase 3 study completed, negative | (79) | ? |

| Recombinant human insulinlike growth factor I (rhIGF-I) | Increase motor neurons survival by decreasing excitotoxicity | Phase 3 study completed, negative | (80) (81) |

? |

| Neurotrophic factors | ||||

| Recombinant human ciliary neurotrophic factor (rHCNTF) | Neuroprotective effect in response to nerve injury | Phase 2/3 study completed, negative | (82) | ? |

| Xaliprodene | Neurotrophin-like activity | Phase 3 study completed, negative | (83) | ? |

| r-metHuBDNF | Foster motor neuron survival | Phase 1/2 study completed, no conclusions drawn about efficacy | (84) | ? |

| GM604 | Modulates neuroprotection, neurogenesis, neural development, neuronal signaling, neuronal transport. | Phase 2 study completed, no results available yet | NCT01854294 | ? |

| SNN0029 (rhVEGF-165) | Contains recombinant human VEGF which acts as a neurotrophic factor | Phase 2 study terminated for “lack of favorable benefit risk ratio” | NCT01384162 | ? |

| Protein kinases | ||||

| Masitinib (AB1010) | C-kit tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Phase 2/3study active, not recruiting | NCT02588677 | ? |

| Fasudil | Rho kinase inhibitor | Phase 2 study recruitment status unknown | NCT01935518 | Inhibitor |

| Stem cell therapy | ||||

| Hematopoietic stem cells - autologous | stimulate neuroplasticity | Phase 2/3 study completed, no results available yet | NCT01933321 | ? |

| Hematopoietic stem cells - allogeneic | stimulate neuroplasticity | Phase 1 study completed, negative | (85) | ? |

| Peripheral blood mononuclear cell-derived CD133+ stem cells | Neuroregeneration | Phase 1/2 studies completed, positive | (86,87) | ? |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | stimulate neuroplasticity | Phase 1 study completed, positive | (88) | |

| Long-term safety study Phase 1/2 completed, positive Phase 1 ongoing, not recruiting Phase 1/2 studies recruiting Phase 1 studies recruiting |

(89) (90) NCT01609283 |

|||

| Neurotrophic factors: secreting mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC-NTF, NurOwn™) | Neuroregeneration | Phase 1/2 and phase 2 studies concluded, no results available Phase 2 study ongoing, not recruiting |

NCT02917681; NCT02290886 |

? |

| Bone marrow stromal cell-derived neural stem cells | Neuroregeneration | Phase 1 study completed, negative |

NCT02987413; NCT02492516 |

? |

| Human fetal spinal cord-derived neural stem cell (HSSCs) | Neuroregeneration | Phase 1 study completed, positive Phase 1 and phase 2 studies ongoing, not recruiting |

NCT01051882; NCT02017912 NCT01777646 (91) (92) NCT01348451; NCT01730716 |

? |

| Muscles | ||||

| CK-2017357 - Tirasemtiv | Stimulates fast skeletal muscle troponin, and improves muscle | Phase 2 study completed, negative | (93) | ? |

| Ozanezumab (hmAb against Nogo-A) - GSK1223249 | Promotes neurite growth | Phase 1/2 study completed, positive.Phase 2 study completed, no results available yet | (94) NCT01753076 | ? |

Search strategy and selection criteria

Full-text articles were identified in PubMed between Jan 1, 1970 and Jan 12, 2017, with a combination of the search terms: “Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis”, “ALS”, “Motor Neuron Disease”, “Clinical Trials” and each drug, agent, mechanism of action listed in this Review Other articles or sources were identified by manual searches of the reference lists of selected articles. Only English-language articles were reviewed. No trial about symptomatic treatments was included. We also accessed ClinicalTrials.gov to obtain information on current registered studies of ALS

Regulation of P-gp Expression in ALS

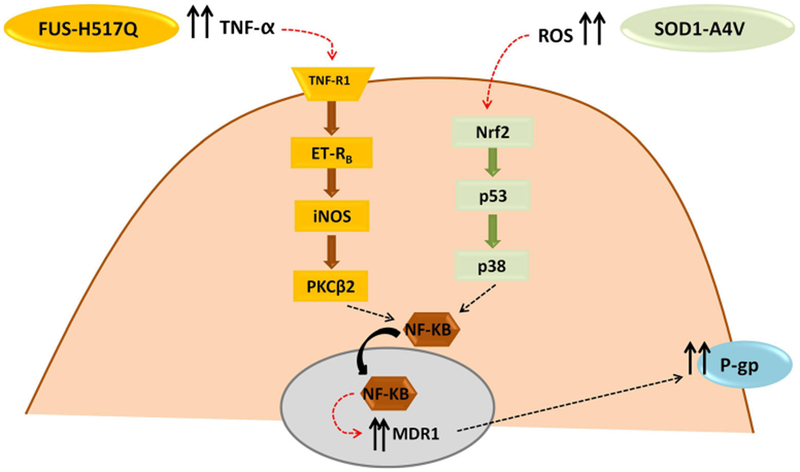

Regulation of P-gp and BCRP expression at the capillary endothelium of the BBB involves multiple signaling pathways, which can be activated by multiple stimuli. Brain capillary endothelium expresses several ligand-activated nuclear receptors, of importance, pregnane-x receptor (PXR), constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), and glucocorticoid receptor (GR). These ligand-activated nuclear receptors regulate P-gp/BCRP expression through different pathways. They can be stimulated by many chemicals and food ingredients which induce efflux transporters’ expression along with phase I and II cytochrome-P450 (CYP-450) enzymes’ expression (95). The mechanism involves binding of stimuli to the specific receptor, translocation of the complex to the nucleus, and binding to the promoter region of the targeted gene. Other mechanisms involve indirect activation of transcription factors through stimulation of plasma membrane receptors, with activation of multiple signaling pathways that converge into nuclear translocation of the ABC transporter master regulator, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFKB), and stimulation of ABC target genes. Upregulation of P-gp and BCRP through receptor-mediated activation can result from several cell stressors, inflammatory mediators, and extracellular glutamate. Most of CNS disorders are characterized by inflammation and are associated with alterations in several pro-inflammatory mediators. One common inflammatory mediator is the tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), which has been found to modulate P-gp expression in endothelial cell culture and in rodent-isolated brain capillaries. TNF-α upregulates P-gp expression, through stimulation of NFKB nuclear translocation, by activating a cascade of upstream molecules including TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), iNOS, and protein kinase C isoform β2 (PKCβ2). An alternative pathway of activated TNFR1 causes immediate reduction in P-gp activity without altering its protein expression by activating PKCβ1 instead of PKCβ2 (96).

Astrocytes expressing the ALS-causative mutations SOD1-G93A or SOD1-A4V when co-cultured with endothelial cells enhances expression and activity of P-gp through the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and stimulation of transcription factor Nrf2 (Fig. 2). In addition, recent studies showed that accompanying ROS changes, there was an increase in the systemic level of the ratio of glutathione disulfide (GSSG)/reduced glutathione (GSH) in ALS patients (97). Interestingly, glutathione, an important antioxidant, was shown to regulate P-gp expression at the BBB by regulating ROS brain level and protecting the BBB endothelial cells from oxidative stress (98,99). Nonetheless, the direct relationship of reduced glutathione and P-gp upregulation at the BBB in ALS has not been studied. Suggested studies may include addressing whether changes in GSSG/GSH ratio observed in ALS patients could be correlated to changes in P-gp expression, which could be a useful biomarker for drug-resistant patients.

Fig. 2.

Suggested pathways that regulate P-gp expression at the BBB in ALS. TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-α, TNF-R1 tumor necrosis factor receptor-1, ET-RB endothelin receptor-B, iNOS inducible itric oxide synthase, PKCB2 protein kinase C isoform β2, ROS reactive oxygen species, Nrf2 Erythroid derived 2 like-2, NFkB nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, mdr1 multidrug resistance protein-1, P-gp permeability glycoprotein or P-glycoprotein

Additionally, astrocytes harboring another ALS-causative mutant protein, FUS-H517Q, drive P-gp upregulation through inflammatory stress, namely by secreting TNF-α that is known to ultimately activate NFkB, as depicted in Fig. 2 (29,100–102). Because both familial and sporadic ALS types are characterized by upregulation of P-gp at the BBB, it could be concluded that factors that upregulate P-gp expression do not depend on specific disease-driven mutations. It is worth mentioning that the increase in P-gp expression at the BBB in ALS occurs not only at the protein level but also at the mRNA level. In addition, there is an increased transcriptional activity of NFKB, a master regulator of P-gp (4,29). Furthermore, Western blot studies showed that the increase in P-gp expression occurred not only in the plasma membrane fraction but also in the total protein sample from cell or tissue lysate, suggesting that P-gp upregulation is attributed to an increase in its de novo synthesis rather than trafficking from cytoplasmic to plasma membrane compartment (29). However, more experiments should be done on this line of investigation to make more firm assessments.

ASSESSING P-GP ACTIVITY IN HUMANS

The association of P-gp overexpression with drug resistance has been directly correlated with poor therapeutic outcome (103–105). Since the blood is usually sampled to determine pharmacokinetic profile of a drug, it would be difficult to assess drug concentration in specific organs, such as the liver, kidneys, and brain. This is because changes in transporters’ expression may alter the drug pharmacokinetic distribution at the tissue level with minor changes to blood concentrations (106,107). For example, when drug concentrations are measured at steady state in the blood and brain, a ratio of unity of blood/brain drug concentration is expected. However, in case of a drug substrate of efflux transporters at the BBB, the blood/brain ratio of drug concentration is significantly altered (i.e., rapid equilibrium between blood and brain cannot be assumed) (108,109). In this respect, it is very important to determine the influence of transporters on distribution of drugs in the brain in humans.

One of the most powerful, non-invasive tools to assess drug distribution and function of transporters is the use of advanced imaging of radiolabeled substrates, such as positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) techniques. These techniques have been widely used to quantitatively assess P-gp activity in many CNS diseases and to address pharmacoresistance in patients with refractory epilepsy, brain cancers, AD, and HIV (110–112). P-gp function and expression can be determined using two types of radiolabeled tracers, either P-gp substrate tracers or inhibitors of P-gp function. The transporter substrate or inhibitor should be labeled with a positron emitting radioisotope, such as carbon-11 or fluorine-18 (113).

[99mTc]methoxyisobutylisonitrile or [99mTc]sestamibi is a widely used radioisotope for SPECT imaging to detect P-gp function in tumors in rodents and humans (114–116). However, [99mTc]sestamibi is a substrate for not only P-gp but also MRP1, which decreases its specificity toward imaging only P-gp function. Another disadvantage of [99mTc]sestamibi is the lower magnitude of signal produced compared to other PET radiotracers. However, [99mTc]sestamibi has the advantage of producing a radiochemically pure signal, an important criteria for a substrate radioligand (117). Following to the discovery of [99mTc]sestamibi, many other radioligands were developed to be used for PET imaging such as [11C]verapamil, [11C]daunorubicin, [11C]paclitaxel, [11C]loperamide, and [11C]N-desmethyl-loperamide, all of which were evaluated in animals, but only [11C]verapamil, [11C]loperamide, and [11C]N-desmethyl-loperamide were extended to application in humans (118). The most common substrate tracer for P-gp that has been used in PET imaging is (R)-[11C]verapamil. (R)-[11C]verapamil was considered an ideal P-gp tracer due to its low baseline signal and its radiolabeled metabolites which could enhance its PET signal (119). However, the lipophilicity of this probe and its radioactive metabolites, which could potentially enter the brain, complicate data interpretation. In addition, (R)-[11C]verapamil may not be suitable for tracking P-gp functional upregulation, as seen in epilepsy and ALS, because of its low baseline signal (119). Currently, efforts are focused on the development of PET probes that are capable to detect both up- and downregulation of transporter function and expression, with reduced lipophilicity and brain-entering metabolites and a longer physical half-life (labeling with 18F instead of 11C) (120).

PET imaging was useful as a diagnostic tool for ALS patients compared to control subjects. For example, the brain metabolism of fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) was studied using PET with advanced discriminant analysis methods, which accurately distinguish ALS from controls and aided in assessing individual prognosis (121). However, the application of PET imaging in studying altered transporters expression and function at the BBB in ALS remains to be determined.

EXAMPLES OF ABC TRANSPORTERS POLYMORPHISMS IN HUMANS: IMPLICATION FOR CNS PHARMACORESISTANCE

ABCB1 is a highly polymorphic gene. In some instances, polymorphism in genes has been reported to impact protein expression and function. In epilepsy, antiepileptic drug resistance (ADR) is linked to P-gp polymorphism in subgroup of patients (122). However, the correlation between P-gp overexpression and the presence of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ABCB1 and ABCC2 genes in ADR-type epilepsy patients is still controversial and may vary between different ethnic groups (123–125). Using a rigorous screening of pediatric epileptic patients, Escalante-Santiago and colleagues examined nucleotide changes in Mexican patients to identify new and reported mutations in 22 ADR patients and 7 control patients (126). The study genotyped 11 exons in ABCB1 and ABCC1 genes using genomic DNA from leukocytes and revealed 10, new and reported, SNPs in ABCB1. Out of these, rs2229109 (G → A) and rs2032582 (A → T and A → G) were identified in ADR patients, but not control. Six SNPs were identified in ABCC2 gene with rs3740066 (T → T) and 66744 T > A (T → G) unique to the ADR group. Further, the SNP rs2032582 in the ABCB1 gene and the presence of rs3740066 in ABCC2 gene posed the strongest risk factors for ADR. Although this study showed the presence of frequently reported ABCC1 polymorphisms, there was a striking correlation between SNPs in the ABCC2 gene and the occurrence of drug resistance. In another study, Sterjev and colleagues examined the correlation between presence of ABCB1 SNP (C3435T) and response to treatment with carbamazepine (CBZ) in 162 epilepsy patients (127). The study did not find any statistically significant differences in the distribution of C3435T SNP between CBZ-respondent or resistant patients. However, patients who are respondent to higher doses of CBZ treatment correlated well with the presence of ABCB1 SNP (C3435T).

The correlation between the overexpression of P-gp and pharmacoresistance to therapeutic agents and ABCB1 polymorphism has not yet been addressed in ALS. However, findings from other neurological conditions like epilepsy and depression could support this hypothesis. Correlating the expression levels of P-gp to the presence of polymorphisms in ABCB1 gene could be utilized to stratify patients according to their ABCB1 genotype and response to treatment. In addition, screening ALS patients for ABCB1 polymorphisms linked to P-gp overexpression may predict the therapeutic efficacy of drugs that are P-gp substrates.

OVERCOMING PHARMACORESISTANCE AS A THERAPEUTIC STRATEGY FOR ALS

Inhibition of Drug Efflux Transporters

The strategy to use drug efflux transporter inhibitors in combination with the therapeutic drug has been largely employed for chemotherapy in brain tumors (32). First-generation inhibitors are pharmacologically active drugs that not only have clinical use but also inhibit drug efflux transporters. A classical example is verapamil, a calcium channel blocker and the first P-gp inhibitor used to improve brain delivery of anticancer therapeutics (128). In clinical trials, however, verapamil caused serious cardiac side effects due to its higher affinity to inhibit calcium channels than P-gp by 106 times (128). First-generation P-gp inhibitors are toxic and many of them failed in clinical trials (129). For this reason, another class of P-gp inhibitors (second generation), such as valspodar (PSC 833), and dexverapamil were developed to improve specificity. This class of inhibitors faced, however, a major drawback of having overlapping substrate specificity with CYP450, an enzymatic system involved in about 70% of total drug metabolism (130,131). A compound that also interacts with CYP-450 may change the pharmacokinetics of other drugs that are metabolized by CYP-450 and, therefore, is a potential risk for drug-drug interactions. Third-generation inhibitors with highest specificity, and fewer adverse effects were therefore developed. Most notable examples include laniquidar (R101933), tariquidar (XR9576), and elacridar (GF120918/GG918) (13).

Many marketed CNS-active drugs are P-gp substrates and/or inhibitors. For example, the antipsychotics fluphenazine, amisulpride, and demethyl-clozapine and the antiemetic domperidone are P-gp substrates (131). In addition, some antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, chlorpromazine, pimozide, protriptyline, haloperidol, trimipramine, clozapine, and desipramine) inhibit P-gp, which suggest their use as P-gp inhibitors in combination with anticancer drugs to increase their CNS penetration for brain tumor treatment (131–133). For example, coadministration of the chemotherapeutic agent daunorubicin with maprotiline, trimipramine, desipramine, imipramine, or doxepin increased daunorubicin uptake in tumor drug-resistant cell lines (134). Inhibition of P-gp as a strategy to overcome BBB has been tested largely for psychoactive drugs. Inhibition of P-gp with verapamil in rats increased the brain dialysate levels of phenobarbital, felbamate, and lamotrigine as compared to plasma by 1.5- to 2-folds (135). Another example, the brain-to-serum ratio of nortriptyline was significantly increased in rats treated with a P-gp inhibitor compared to untreated animals (136). Therefore, the distribution of psychoactive drugs into the brain may be potentially limited by P-gp at the BBB. Another class of drugs that showed better brain penetration with P-gp inhibitors is central analgesics, such as methadone, morphine, meperidine, oxycodone, and fentanyl (137,138). Central tolerance is a major obstacle facing opioid analgesics, which require higher doses to maintain their effect. One suggested mechanism of opioid tolerance is P-gp-mediated efflux of opioids at the BBB by limiting their brain penetration (137,139). Several preclinical studies showed inhibition of P-gp could increase brain levels of opioids and improve their efficacy (138,140,141). Inhibition of P-gp with GF120918 significantly enhanced morphine antinociceptive effects in rats compared to morphine treatment alone (141). In a recent study, morphine brain uptake was increased over time in rats pretreated with P-gp inhibitors, PSC833 (valspodar) and cyclosporine-A, as determined by in situ brain perfusion(142)

Despite the success of the third-generation P-gp inhibitors in preclinical studies, most of them have largely failed in clinical trials and did not improve therapeutic efficacy of drugs (120,143). Therefore, fourth-generation P-gp inhibitors have been suggested as novel strategy by using natural products, peptidomemetics, and dual-targeting approaches(143). In drug discovery, the development of therapeutics from marine natural products is considered a very promising approach. P-gp inhibitors of marine-derived compounds are largely studied for cancer therapy (144). Some marine-derived compounds are P-gp inhibitors and also demonstrate some anticancer activity, such as alkaloids, terpenoids, and polyoxygenated sterols. An example of marine-derived alkaloids is Lamellarins, which can be isolated from prosobranch mollusk (Lamellaria sp.) (145). Lamellarin I directly inhibits P-gp and increased accumulation and efficacy of vinblastine, doxorubin, and daunorubicine in cancer drug-resistant cells. Compared to verapamil, Lamellarin I enhances the cytotoxicity of doxorubicin in Lo Vo/Dx cell line by 16-fold (145,146). Methoxy-derivatives of lamellarin D, K, and N provide more potent P-gp inhibition and overcome drug resistance in cancer cell lines (144). Alkaloids show more P-gp selectivity, but they have some toxicity. Synthetic analogues of marine natural compounds have shown improved selectivity with less toxicity. However, most of marine inhibitors are scarcely studied and their mechanisms of action are still under investigation. Creating derivatives with higher potency, favorable pharmacokinetic profiles, and less toxicity using rational drug design would result in more clinically effective drug candidates (145).

CHALLENGES OF INHIBITING P-GP FUNCTION AT THE BBB IN THE CLINIC

In preclinical studies, inhibition of P-gp at the BBB resulted in robust increase in brain penetration of drugs that are P-gp substrates by 2- to 100-fold (147). However, in humans, such effect has not been demonstrated (147). A reason for this lack of effect in humans is the low unbound inhibitor concentration in the plasma, which is not sufficient to provide appreciable P-gp inhibition. The highest doses of most marketed P-gp inhibitors examined for use in the clinic provide less than 50% P-gp inhibition based on their reported unbound maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax), with <2-fold increase in brain penetration of the examined therapeutic drug (147). For example, in preclinical animal studies, 50 mg/kg I.V. dose of cyclosporin A increased brain penetration of [11C]-verapamil by 5.3- to 5.8-fold and achieved 83 to 90% P-gp inhibition in mice and rats (148). In the clinic, a dose of 2 mg/kg/h of cyclosporine-A caused 1.6- to 1.9-fold increase in brain penetration of [11C]-verapamil with only 38 to 50% P-gp inhibition (149,150). Given the low plasma fraction unbound of cyclosporin A (≈0.10), in human, higher doses of cyclosporin A are required to increase Cmax, obtain 80 to 90% P-gp inhibition, and achieve appreciable (<2-fold) verapamil brain penetration. A 100 times greater dose of tariquidar than its inhibition constant (Ki) is necessary to increase P-gp substrate in the brain by 50% (151). Thus, with the current marketed P-gp inhibitors, such increases in the dose are hampered by potential side effects and toxicity. It is noteworthy that most clinical studies that examined the inhibition of P-gp at the BBB to increase brain penetration of P-gp substrates are acute studies with a single dose of the tested inhibitor, or infusion for short time. Chronic use of P-gp inhibitors in a combinatorial regimen with drugs that are P-gp substrates may have a different overall impact on brain penetration of drugs.

Another reason for poor preclinical to clinical translation of P-gp inhibitors could be attributed to species differences in P-gp expression and sensitivity. However, while P-gp expression at the BBB is ~2-fold higher in mice than humans, the majority of reported half maximal inhibitory concentrations for most P-gp inhibitors in rodents and humans are comparable (152). Therefore, the difference in P-gp expression and sensitivity between rodents and humans are modest and unlikely to contribute to the poor clinical translation of P-gp inhibitors. Consequently, preclinical rodent models are expected to show comparable P-gp inhibition to humans if the P-gp inhibitors are given to animals at doses that mimic unbound inhibitor concentration in humans’ plasma. Advanced mathematical modeling could be a useful tool to predict unbound brain concentrations of the investigated drugs. However, to date, accurate quantification of unbound extracellular brain concentration of drugs in humans can only be determined using microdialysis technique, which is extremely invasive and not applicable to patients (153).

Targeting Transporters Regulation

Inhibition of P-gp to overcome limited brain penetration of riluzole in ALS could prove to be a suitable strategy, but there are some challenges with the use of current P-gp inhibitors, which include: (1) The high dose for available inhibitors required to significantly block P-gp is in the micromolar concentration range, which may lead to adverse reactions and toxicity and (2) selectivity and specificity of inhibition of P-gp only at the BBB and not in excretory organs like liver, kidneys, and the intestine. Therefore, indirect targeting of P-gp by blocking signaling pathways that regulate P-gp expression in ALS could provide a possible alternative. Our lab recently identified some of the signaling pathways involved in P-gp upregulation in ALS (29). Different genetic mutations linked to familial ALS appear to drive P-gp upregulation through soluble factors secreted by astrocytes that trigger different signaling pathways converging on NFKB activation and its nuclear translocation in endothelial cells. Qosa and colleagues showed that overexpression of P-gp in pMBEC was driven by SOD1-G93A astrocytes and inhibited by SN50, an NFkB inhibitor (29). Therefore, targeting the endothelial cell NFKB signaling could be a possible strategy to alleviate drug resistance mediated by P-gp.

It is interesting that the neurotransmitter glutamate also appears to regulate P-gp expression at the BBB through a signaling pathway that involves NFKB activation. In rodents, as well as in human cells, glutamate stimulates P-gp upregulation via activation of NMDA receptors expressed on the brain capillary endothelium (154). COX-II is a downstream molecule in this signaling pathway. Several preclinical studies have indeed targeted inhibition of COX-II to overcome glutamate-mediated P-gp upregulation (155).

Bypassing BBB

Transient BBB disruption by hyperosmolar agents and the use of Trojan horse receptor-mediated transport, nasal drug delivery, and transcranial delivery has been employed to bypass the BBB (156). Targeted drug delivery to the brain has been studied using nanotechnology in neurologic diseases such as PD and AD (156). For example, glutathione, a neuroprotective antioxidant, has been encapsulated in liposomes, lecithin, and glycerol lipid vesicles, which can cross the BBB and can be taken up by neurons (157). Nanotechnology has also been employed to improve drug absorption via nasal route in Parkinson’s disease animal model utilizing nanoparticles modified with odorranalectin to enhance nanoparticles uptake by nasal epithelial cells and, hence, improve brain delivery (156). For ALS, Bondi and colleagues prepared riluzole as drug-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles using the warm oil-in-water microemulsion technique, which improved drug-loading capacity and produced small particle size. This formula improved riluzole brain penetration and efficacy in rats with minimal distribution to other body organs such as the liver, spleen, heart, kidneys, and lung (158). In another study, riluzole was encapsulated in nanoparticles made of Chitosan-conjugated NIPAAM (N-isopropylacrylamide) and coated with tween80 prepared by free radical polymerization in order to improve the overall riluzole aqueous solubility and BBB penetration in cerebral ischemia animal model (159). Animals treated with nanoriluzole showed significant neuroprotection at lower concentration and improved aqueous solubility with longer half-life compared to conventional riluzole (159). Minocycline, a tetracyclic antibiotic, was previously reported to have neuroprotective properties and was tested alone and in combination with riluzole in phase I and III clinical trials in ALS patients. Failure in combination therapy was suggested due to drug–drug interaction at the BBB (160). In that study, minocycline inhibited P-gp at the BBB which increased riluzole brain penetration by 2-fold and was suggested to cause brain neurotoxicity with the 10 mg/kg tested dose of riluzole (160). A similar dose of riluzole was shown to cause neurotoxicity in P-gp null mice (160). As a monotherapy, minocycline brain penetration is limited by P-gp at the BBB. One attempt to improve minocycline efficacy was by encapsulation into lipopolysaccharide-modified liposomes to target TLR4 receptors of microglia and reduce neuroinflammation in SOD1-G93A mice (156). Minocycline-targeted nanoliposomes showed better efficacy compared to un-modified nanoliposomes and delayed disease onset and increased life span. However, this approach was used to improve minocycline site-specific action as the drug was infused intracerebroventricularly, while its ability to cross the BBB in this formulation was not examined (156).

THE NEED OF STRATIFYING ALS PATIENTS IN CLINICAL TRIALS

A complete understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying P-gp overexpression in ALS may guide the development of personalized therapy for patients. This may help to improve the selection and inclusion criterion for clinical trials. If P-gp-mediated pharmacoresistance hypothesis is confirmed in the clinic, then it would be very important to consider testing investigational drugs that interact with P-gp in preclinical stages. Identifying therapeutics at preclinical stages would improve designing clinical trials. For example, examining ALS patients for polymorphisms in ABCB1 gene that are causative of pathologic P-gp overexpression and drug resistance could be useful to stratify patients according to their ABCB1 genotype. Therefore, patients who are positive for that particular ABCB1 polymorphism are categorized as a treatment non-respondent group and considered for individualized therapeutic regimen. Changes in therapeutic regimen may include combinatorial therapy of ALS drugs with P-gp inhibitors, or adjustments in dose, frequency and length of treatment.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Overcoming drug resistance at the BBB using compounds that regulate expression and activity of P-gp and other drug efflux transporters is still an active area of research. Ideal compounds that would provide a clinically significant inhibition of multidrug efflux transporter activity are compounds that can be safely administered at doses that provide unbound plasma concentration many fold higher than the Ki of the inhibitor. Thus, clinical application of, for instance, P-gp inhibitors remain challenging with regard to potency as well as specificity. Other possible strategies include targeting signaling pathways that regulate P-gp expression in disease. However, a complete understanding of P-gp regulatory mechanisms in neurological conditions such as ALS is required to find promising therapeutic targets. Although P-gp overexpression has been detected in ALS post-mortem brain and spinal cord tissues, further studies are still essential to proof this hypothesis in living patients. Utilizing advanced imaging technology would help to accomplish this goal.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number RO1-NS074886 to DT) and Target ALS (to DT and PP).

REFERENCES

- 1.Garbuzova-Davis S, Sanberg PR. Blood-CNS barrier impairment in ALS patients versus an animal model. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scherrmann JM. Expression and function of multidrug resistance transporters at the blood-brain barriers. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2005;1(2):233–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheah BC, Vucic S, Krishnan AV, Kiernan MC. Riluzole, neuroprotection and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17(18):1942–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jablonski MR, Jacob DA, Campos C, Miller DS, Maragakis NJ, Pasinelli P, et al. Selective increase of two ABC drug efflux transporters at the blood-spinal cord barrier suggests induced pharmacoresistance in ALS. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;47(2):194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obermeier B, Verma A, Ransohoff RM. The blood-brain barrier. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;133:39–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbott NJ, Patabendige AA, Dolman DE, Yusof SR, Begley DJ. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37(1):13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolburg H, Noell S, Mack A, Wolburg-Buchholz K, Fallier-Becker P. Brain endothelial cells and the glio-vascular complex. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335(1):75–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juliano RL, Ling V. A surface glycoprotein modulating drug permeability in Chinese hamster ovary cell mutants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;455(1):152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernacki J, Dobrowolska A, Nierwinska K, Malecki A. Physiology and pharmacological role of the blood-brain barrier. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60(5):600–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamiie J Progress of drug transport study based on absolute quantitative method for membrane transporter proteins. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2008;128(4):507–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terasaki T, Hosoya K. The blood-brain barrier efflux transporters as a detoxifying system for the brain. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1999;36(2–3):195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schinkel AH, Jonker JW. Mammalian drug efflux transporters of the ATP binding cassette (ABC) family: an overview. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55(1):3–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amin ML. P-glycoprotein inhibition for optimal drug delivery. Drug Target Insights. 2013;7:27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demeule M, Regina A, Jodoin J, Laplante A, Dagenais C, Berthelet F, et al. Drug transport to the brain: key roles for the efflux pump P-glycoprotein in the blood-brain barrier. Vasc Pharmacol. 2002;38(6):339–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bendayan R, Ronaldson PT, Gingras D, Bendayan M. In situ localization of P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) in human and rat brain. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54(10):1159–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajagopal A, Simon SM. Subcellular localization and activity of multidrug resistance proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(8):3389–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borst P, Evers R, Kool M, Wijnholds J. A family of drug transporters: the multidrug resistance-associated proteins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(16):1295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seelig A, Blatter XL, Wohnsland F. Substrate recognition by P-glycoprotein and the multidrug resistance-associated protein MRP1: a comparison. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;38(3):111–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cisternino S, Mercier C, Bourasset F, Roux F, Scherrmann JM. Expression, up-regulation, and transport activity of the multidrug-resistance protein Abcg2 at the mouse blood-brain barrier. Cancer Res. 2004;64(9):3296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooray HC, Blackmore CG, Maskell L, Barrand MA. Localisation of breast cancer resistance protein in microvessel endothelium of human brain. Neuroreport. 2002;13(16):2059–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenblatter T, Huwel S, Galla HJ. Characterisation of the brain multidrug resistance protein (BMDP/ABCG2/BCRP) expressed at the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res. 2003;971(2):221–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008;57(2):178–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Vries HE, Kooij G, Frenkel D, Georgopoulos S, Monsonego A, Janigro D. Inflammatory events at blood-brain barrier in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative disorders: implications for clinical disease. Epilepsia. 2012;53(Suppl 6):45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leonardi A, Abbruzzese G, Arata L, Cocito L, Vische M. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol. 1984;231(2):75–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donnenfeld H, Kascsak RJ, Bartfeld H. Deposits of IgG and C3 in the spinal cord and motor cortex of ALS patients. J Neuroimmunol. 1984;6(1):51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong Z, Deane R, Ali Z, Parisi M, Shapovalov Y, O’Banion MK, et al. ALS-causing SOD1 mutants generate vascular changes prior to motor neuron degeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(4):420–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicaise C, Mitrecic D, Demetter P, De Decker R, Authelet M, Boom A, et al. Impaired blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barriers in mutant SOD1-linked ALS rat. Brain Res. 2009;1301:152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qosa H, Mohamed LA, Alqahtani S, Abuasal BS, Hill RA, Kaddoumi A. Transporters as Drug Targets in Neurological Diseases. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100(5):441–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qosa H, Lichter J, Sarlo M, Markandaiah SS, McAvoy K, Richard JP, et al. Astrocytes drive upregulation of the multidrug resistance transporter ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein) in endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier in mutant superoxide dismutase 1-linked amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Glia. 2016;64(8):1298–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oby E, Janigro D. The blood-brain barrier and epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47(11):1761–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cen J, Liu L, Li MS, He L, Wang LJ, Liu YQ, et al. Alteration in P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier in the early period of MCAO in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2013;65(5):665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agarwal S, Hartz AM, Elmquist WF, Bauer B. Breast cancer resistance protein and P-glycoprotein in brain cancer: two gatekeepers team up. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(26):2793–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boston-Howes W, Williams EO, Bogush A, Scolere M, Pasinelli P, Trotti D. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid increases glutamate uptake in vitro and in vivo: therapeutic implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp Neurol. 2008;213(1):229–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milane A, Fernandez C, Dupuis L, Buyse M, Loeffler JP, Farinotti R, et al. P-glycoprotein expression and function are increased in an animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci Lett. 2010;472(3):166–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan GN, Evans R, Banks D, Mesev E, Miller DS, Cannon RE. Selective induction of P-glycoprotein at the CNS barriers during symptomatic stage of an ALS animal model. Neurosci Lett. 2016;3(639):103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milane A, Fernandez C, Vautier S, Bensimon G, Meininger V, Farinotti R. Minocycline and riluzole brain disposition: interactions with p-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier. J Neurochem. 2007;103(1):164–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milane A, Vautier S, Chacun H, Meininger V, Bensimon G, Farinotti R, et al. Interactions between riluzole and ABCG2/BCRP transporter. Neurosci Lett. 2009;452(1):12–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jablonski MR, Markandaiah SS, Jacob D, Meng NJ, Li K, Gennaro V, et al. Inhibiting drug efflux transporters improves efficacy of ALS therapeutics. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2014;1(12):996–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bensimon G, Lacomblez L, Meininger V. A controlled trial of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS/Riluzole Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(9):585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lacomblez L, Bensimon G, Leigh PN, Guillet P, Meininger V. Dose-ranging study of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/Riluzole Study Group II. Lancet. 1996;347(9013):1425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tandan R, Bromberg MB, Forshew D, Fries TJ, Badger GJ, Carpenter J, et al. A controlled trial of amino acid therapy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: I. Clinical, functional, and maximum isometric torque data. Neurology. 1996;47(5):1220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pascuzzi rM, Shefner J, Chappell AS, Bjerke JS, Tamura R, Chaudhry V, et al. A phase II trial of talampanel in subjects with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010;11(3):266–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine TD, Bowser R, Hank N, Saperstein D. A pilot trial of memantine and riluzole in ALS: correlation to CSF biomarkers. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010;11(6):514–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Carvalho M, Pinto S, Costa J, Evangelista T, Ohana B, Pinto A. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of memantine for functional disability in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010;11(5):456–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rotto DM, Hill JM, Schultz HD, Kaufman MP. Cyclooxygenase blockade attenuates responses of group IV muscle afferents to static contraction. Am J Phys. 1990;259(3 Pt 2):H745–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cudkowicz ME, Shefner JM, Schoenfeld DA, Brown RH Jr, Johnson H, Qureshi M, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2003;61(4):456–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eisen A, Stewart H, Schulzer M, Cameron D. Anti-glutamate therapy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a trial using lamotrigine. Can J Neurol Sci. 1993;20(4):297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryberg H, Askmark H, Persson LI. A double-blind randomized clinical trial in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using lamotrigine: effects on CSF glutamate, aspartate, branched-chain amino acid levels and clinical parameters. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;108(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller RG, Moore DH 2nd, Gelinas DF, Dronsky V, Mendoza M, Barohn RJ, et al. Phase III randomized trial of gabapentin in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2001;56(7):843–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller RG, Shepherd R, Dao H, Khramstov A, Mendoza M, Graves J, et al. Controlled trial of nimodipine in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuromuscul Disord. 1996;6(2):101–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gredal O, Werdelin L, Bak S, Christensen Pb, Boysen G, Kristensen MO, et al. A clinical trial of dextromethorphan in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1997;96(1):8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brooks BR, Thisted RA, Appel SH, Bradley WG, Olney RK, Berg JE, et al. Treatment of pseudobulbar affect in ALS with dextromethorphan/quinidine: a randomized trial. Neurology. 2004;63(8):1364–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammond FM, Alexander DN, Cutler AJ, D’Amico S, Doody RS, Sauve W, et al. PRISM II: an open-label study to assess effectiveness of dextromethorphan/quinidine for pseudobulbar affect in patients with dementia, stroke or traumatic brain injury. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pioro EP, Brooks BR, Cummings J, Schiffer R, Thisted RA, Wynn D, et al. Dextromethorphan plus ultra low-dose quinidine reduces pseudobulbar affect. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(5):693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith R, Pioro E, Myers K, Sirdofsky M, Goslin K, Meekins G, et al. Enhanced bulbar function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the nuedexta treatment trial. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(3):762–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ikeda K, Iwasaki Y, Kaji R. Neuroprotective effect of ultra-high dose methylcobalamin in wobbler mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2015;354(1–2):70–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cudkowicz ME, Titus S, Kearney M, Yu H, Sherman A, Schoenfeld D, et al. Safety and efficacy of ceftriaxone for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a multi-stage, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(11):1083–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gordon PH, Moore DH, Miller RG, Florence JM, Verheijde JL, Doorish C, et al. Efficacy of minocycline in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase III randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(12):1045–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shefner JM, Cudkowicz ME, Schoenfeld D, Conrad T, Taft J, Chilton M, et al. A clinical trial of creatine in ALS. Neurology. 2004;63(9):1656–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gordon PH, Cheung YK, Levin B, Andrews H, Doorish C, Macarthur RB, et al. A novel, efficient, randomized selection trial comparing combinations of drug therapy for ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2008;9(4):212–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lenglet T, Lacomblez L, Abitbol JL, Ludolph A, Mora JS, Robberecht W, et al. A phase II-III trial of olesoxime in subjects with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(3):529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cudkowicz ME, van den Berg LH, Shefner JM, Mitsumoto H, Mora JS, Ludolph A, et al. Dexpramipexole versus placebo for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (EMPOWER): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(11):1059–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Macchi Z, Wang Y, Moore D, Katz J, Saperstein D, Walk D, et al. A multi-center screening trial of rasagiline in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: possible mitochondrial biomarker target engagement. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;16(5–6):345–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elia AE, Lalli S, Monsurro MR, Sagnelli A, Taiello AC, Reggiori B, et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23(1):45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beghi E, Pupillo E, Bonito V, Buzzi P, Caponnetto C, Chio A, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of acetyl-L-carnitine for ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14(5–6):397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miller R, Bradley W, Cudkowicz M, Hubble J, Meininger V, Mitsumoto H, et al. Phase II/III randomized trial of TCH346 in patients with ALS. Neurology. 2007;69(8):776–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Orrell RW, Lane RJ, Ross M. A systematic review of antioxidant treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2008;9(4):195–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoshino H, Kimura A. Investigation of the therapeutic effects of edaravone, a free radical scavenger, on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (phase II study). Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2006;7(4):241–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abe K, Itoyama Y, Sobue G, Tsuji S, Aoki M, Doyu M, et al. Confirmatory double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety of edaravone (MCI-186) in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2014;15(7–8):610–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dupuis L, Dengler R, Heneka MT, Meyer T, Zierz S, Kassubek J, et al. A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in combination with riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e37885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miller RG, Block G, Katz JS, Barohn RJ, Gopalakrishnan V, Cudkowicz M, et al. Randomized phase 2 trial of NP001-a novel immune regulator: safety and early efficacy in ALS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015;2(3):e100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mizwicki MT, Fiala M, Magpantay L, Aziz N, Sayre J, Liu G, et al. Tocilizumab attenuates inflammation in ALS patients through inhibition of IL6 receptor signaling. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2012;1(3):305–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fiala M, Mizwicki MT, Weitzman R, Magpantay L, Nishimoto N. Tocilizumab infusion therapy normalizes inflammation in sporadic ALS patients. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2013;2(2):129–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meininger V, Drory VE, Leigh PN, Ludolph A, Robberecht W, Silani V. Glatiramer acetate has no impact on disease progression in ALS at 40 mg/day: a double-blind, randomized, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10(5–6):378–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Olson WH, Simons JA, Halaas GW. Therapeutic trial of tilorone in ALS: lack of benefit in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurology. 1978;28(12):1293–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scelsa SN, MacGowan DJ, Mitsumoto H, Imperato T, LeValley AJ, Liu MH, et al. A pilot, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of indinavir in patients with ALS. Neurology. 2005;64(7):1298–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lange DJ, Andersen PM, Remanan R, Marklund S, Benjamin D. Pyrimethamine decreases levels of SOD1 in leukocytes and cerebrospinal fluid of ALS patients: a phase I pilot study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14(3):199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morrison KE, Dhariwal S, Hornabrook R, Savage L, Burn DJ, Khoo TK, et al. Lithium in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (LiCALS): a phase 3 multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(4):339–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sacca F, Quarantelli M, Rinaldi C, Tucci T, Piro R, Perrotta G, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of growth hormone in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: clinical, neuroimaging, and hormonal results. J Neurol. 2012;259(1):132–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sorenson EJ, Windbank AJ, Mandrekar JN, Bamlet WR, Appel SH, Armon C, et al. Subcutaneous IGF-1 is not beneficial in 2-year ALS trial. Neurology. 2008;71(22):1770–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beauverd M, Mitchell JD, Wokke JH, Borasio GD. Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor I (rhIGF-I) for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD002064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of subcutaneous recombinant human ciliary neurotrophic factor (rHCNTF) in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS CNTF Treatment Study Group. Neurology, 1996; 46(5):1244–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meininger V, Bensimon G, Bradley WR, Brooks B, Douillet P, Eisen AA, et al. Efficacy and safety of xaliproden in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: results of two phase III trials. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2004;5(2):107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ochs G, Penn RD, York M, Giess R, Beck M, Tonn J, et al. A phase I/II trial of recombinant methionyl human brain derived neurotrophic factor administered by intrathecal infusion to patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1(3):201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Appel SH, Engelhardt JI, Henkel JS, Siklos L, Beers DR, Yen AA, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2008;71(17):1326–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Martinez HR, Gonzalez-Garza MT, Moreno-Cuevas JE, Caro E, Gutierrez-Jimenez E, Segura JJ. Stem-cell transplantation into the frontal motor cortex in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Cytotherapy. 2009;11(1):26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Martinez HR, Molina-Lopez JF, Gonzalez-Garza MT, Moreno-Cuevas JE, Caro-Osorio E, Gil-Valadez A, et al. Stem cell transplantation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: methodological approach, safety, and feasibility. Cell Transplant. 2012;21(9):1899–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mazzini L, Ferrero I, Luparello V, Rustichelli D, Gunetti M, Mareschi K, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase I clinical trial. Exp Neurol. 2010;223(1):229–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mazzini L, Mareschi K, Ferrero I, Miglioretti M, Stecco A, Servo S, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell transplantation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a long-term safety study. Cytotherapy. 2012;14(1):56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Karussis D, Karageorgiou C, Vaknin-Dembinsky A, Gowda-Kurkalli B, Gomori JM, Kassis I, et al. Safety and immunological effects of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(10):1187–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nafissi S, Kazemi H, Tiraihi T, Beladi-Moghadam N, Faghihzadeh S, Faghihzadeh E, et al. Intraspinal delivery of bone marrow stromal cell-derived neural stem cells in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a safety and feasibility study. J Neurol Sci. 2016;362:174–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Feldman EL, Boulis NM, Hur J, Johe K, Rutkove SB, Federici T, et al. Intraspinal neural stem cell transplantation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: phase 1 trial outcomes. Ann Neurol. 2014;75(3):363–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shefner JM, Wolff AA, Meng L, Bian A, Lee J, Barragan D, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase IIb trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of tirasemtiv in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2016;17(5–6):426–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Meininger V, Pradat PF, Corse A, Al-Sarraj S, Rix Brooks B, Caress JB, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic, and functional effects of the nogo-a monoclonal antibody in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomized, first-in-human clinical trial. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chan GN, Hoque MT, Bendayan R. Role of nuclear receptors in the regulation of drug transporters in the brain. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34(7):361–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Miller DS. Regulation of ABC transporters at the blood-brain barrier. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97(4):395–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Blasco H, Garcon G, Patin F, Veyrat-Durebex C, Boyer J, Devos D, et al. Panel of oxidative stress and inflammatory biomarkers in ALS: a pilot study. Can J Neurol Sci. 2017;44(1):90–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Said Ahmed M, Hung WY, Zu JS, Hockberger P, Siddique T. Increased reactive oxygen species in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with mutations in SOD1. J Neurol Sci. 2000;176(2):88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hong H, Lu Y, Ji ZN, Liu GQ. Up-regulation of P-glycoprotein expression by glutathione depletion-induced oxidative stress in rat brain microvessel endothelial cells. J Neurochem. 2006;98(5):1465–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vehvilainen P, Koistinaho J, Gundars G. Mechanisms of mutant SOD1 induced mitochondrial toxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cassina P, Cassina A, Pehar M, Castellanos R, Gandelman M, de Leon A, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in SOD1G93A-bearing astrocytes promotes motor neuron degeneration: prevention by mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants. J Neurosci. 2008;28(16):4115–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tortarolo M, Vallarola A, Lidonnici D, Battaglia E, Gensano F, Spaltro G, et al. Lack of TNF-alpha receptor type 2 protects motor neurons in a cellular model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and in mutant SOD1 mice but does not affect disease progression. J Neurochem. 2015;135(1):109–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]