Abstract

Background

The development of an autistic brain is a highly complex process as evident from the involvement of various genetic and non-genetic factors in the etiology of the autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Despite being a multifactorial neurodevelopmental disorder, autistic patients display a few key characteristics, such as the impaired social interactions and elevated repetitive behaviors, suggesting the perturbation of specific neuronal circuits resulted from abnormal signaling pathways during brain development in ASD. A comprehensive review for autistic signaling mechanisms and interactions may provide a better understanding of ASD etiology and treatment.

Main body

Recent studies on genetic models and ASD patients with several different mutated genes revealed the dysregulation of several key signaling pathways, such as WNT, BMP, SHH, and retinoic acid (RA) signaling. Although no direct evidence of dysfunctional FGF or TGF-β signaling in ASD has been reported so far, a few examples of indirect evidence can be found. This review article summarizes how various genetic and non-genetic factors which have been reported contributing to ASD interact with WNT, BMP/TGF-β, SHH, FGF, and RA signaling pathways. The autism-associated gene ubiquitin-protein ligase E3A (UBE3A) has been reported to influence WNT, BMP, and RA signaling pathways, suggesting crosstalk between various signaling pathways during autistic brain development. Finally, the article comments on what further studies could be performed to gain deeper insights into the understanding of perturbed signaling pathways in the etiology of ASD.

Conclusion

The understanding of mechanisms behind various signaling pathways in the etiology of ASD may help to facilitate the identification of potential therapeutic targets and design of new treatment methods.

Keywords: WNT, BMP/TGF-β, SHH, FGF, Retinoic acid (RA), Signaling crosstalk, Autism spectrum disorder, Neurodevelopmental disorders

Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a multifactorial neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impaired social interactions and elevated repetitive behaviors, in which various circuits in the sensory, prefrontal, hippocampal, cerebellar, striatal, and other midbrain regions are perturbed [1, 2]. Compared to de novo non-coding variations, the de novo coding variants have a strong association with ASD as shown by the whole-genome sequence association (WGSA) studies in 519 ASD families [3]. Kosmicki et al. further showed CHD8, ARID1B, DYRK1A, SYNGAP1, ADNP, ANK2, DSCAM, SCN2A, ASH1L, CHD2, KDM5B, and POGZ genes with ≥ 3 class 1 de novo protein-truncating variants (PTVs) in individuals with ASD [4]. ANK2, CHD8, CUL3, DYRK1A, GRIN2B, KATNAL2, POGZ, SCN2A, and TBR1 genes are identified as high-confidence ASD risk genes, of which CHD8 is strongly associated with ASD because of the largest number of de novo loss-of-function (LOF) mutations observed in patients [5, 6]. Various gene mutations reported in ASD patients are either core components of the WNT signaling pathway or their modulators [7–9]. More recently, a few reports support the idea of modulation of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling as a contributing factor in ASD model organisms and humans. For instance, Neuroligins (NLGN), fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1), ubiquitin-protein ligase E3A (UBE3A), and DLX, which modulate BMP signaling, have been found to be associated with ASD [10–13]. Dysregulation of sonic hedgehog (SHH) [14, 15], fibroblast growth factor (FGF) [16], transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) [17, 18], and retinoic acid (RA) [19] signaling pathways have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of ASD. Valproic acid (VPA), used in the treatment of epilepsy and bipolar disorder, may affect the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway. However, its prenatal exposure in rats also causes susceptibility to autism [20]. Due to the scarcity of information on the mechanisms underlying the etiologies of ASD, the success of therapeutic strategies is greatly limited.

Altered WNT signaling in ASD

WNT signaling is fundamental for neurodevelopmental and post-neurodevelopmental processes, such as CNS regionalization, neural progenitor differentiation, neuronal migration, axon guidance, dendrite development, synaptogenesis, adult neurogenesis, and neural plasticity [21–30], and therefore, any perturbation in WNT signaling may trigger the advent of disorders related to the structures and functions of the CNS [9, 31]. Studies in genetically modified animal models and human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) models, along with large-scale human genomic studies in several neurodevelopmental disorders over the last few decades, have revealed the importance of spatiotemporal regulation of WNT signaling throughout the lifespan of an animal [9]. Moreover, dysregulation of WNT signaling has been reported in several psychiatric disorders, including ASD, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, as well as in case of intellectual disability [8, 9, 31–34]. Although several genetic and epigenetic factors have been linked with the etiologies of neurodevelopmental disorders, they often seem to affect a few common processes, such as chromatin remodeling, WNT signaling, and synaptic function [32, 35, 36]. Despite the heterogeneity in WNT signaling, it is broadly classified into “canonical” (β-catenin-dependent) and “non-canonical” (β-catenin-independent) pathways [37, 38]. Both canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling pathways play crucial roles in neural development and related neurodevelopmental disorders.

Genetic etiologies

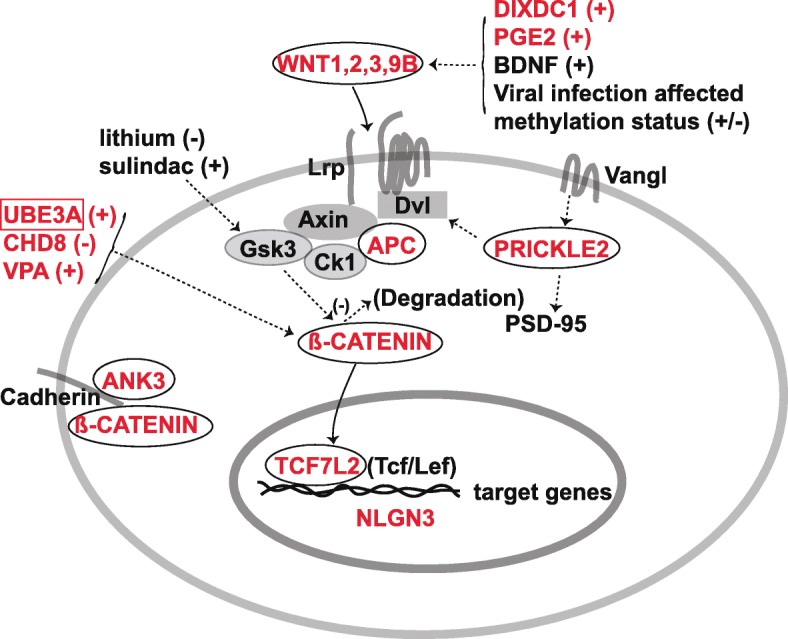

Several genetic loci/mutations linked to and/or reported in ASD patients are either core components of canonical WNT signaling, such as β-catenin (CTNNB1) [8, 9, 36, 39] and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) [1], or non-canonical WNT signaling, such as PRICKLE2 [40], suggesting crucial roles of both canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling pathways in the etiologies of ASD (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) causal genes influencing WNT, BMP/TGF-β, SHH, FGF, and RA signaling pathways in vertebrates and invertebrates

| ASD causal genes | Region/neurons/cells in which gene function is affected | Species | Affected signaling pathway | Phenotypes/downstream targets | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT GOF (gain-of-function) | Blood | Human | TGF-β | TGF-β pathway identified as a novel hyperserotonemia-related ASD genes | [18] |

| ALDH1A3 | Human | RA | [135] | ||

| ANK3 LOF (loss-of-function) | P19 cells, proliferating neural progenitors of E16 mouse cortices, E15 brain slices | Mouse | WNT (canonical) | Increases proliferation of neural progenitor cells and nuclear β-catenin | [85] |

| APC LOF | Forebrain neurons, and hippocampal, cortical, and striatal regions | Mouse | WNT (canonical) | Learning and memory impairments and autistic-like behaviors (increased repetitive behaviors, reduced social interest) | [1] |

| BTBR T+ Itpr3tf/J (BTBR) mice | Spleen and brain tissues | Mouse | TGF-β | Decreased TGF-β levels | [17] |

| CD38 | Lymphoblastoid cell lines | Human and mouse | RA | Upregulation of CD38 by RA | [140, 141] |

| CHD8−/− LOF | Whole | Mouse | WNT (canonical) | Embryonically lethal | [87] |

| CHD8+/− LOF | Nucleus accumbens (NAc) | Mouse | WNT (canonical) | Macrocephaly, craniofacial abnormalities, and behavioral deficits; WNT signaling upregulates in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) region of the brain | [89] |

| CTNNB1 LOF | Parvalbumin interneurons | Mouse | WNT (canonical) | Impaired object recognition and social interactions; elevated repetitive behaviors; enhanced spatial memory | [66] |

| CTNNB1 cKO LOF | Dorsal neural folds | Mouse | WNT (canonical) | Spina bifida aperta, caudal axis bending, and tail truncation | [65] |

| CTNNB1 haploinsufficiency LOF | Whole | Human and mouse | WNT (canonical) | Neuronal loss, craniofacial anomalies, and hair follicle defects | [64] |

| DHCR7 LOF | MEFs | Mouse | SHH | Impaired SMO and reduced SHH signaling | [111] |

| DIXDC1 LOF | Mouse cortex | Human and mouse | WNT (canonical) | Impaired dendrite and spine growth, positive modulator of WNT signaling | [79] |

| Dlx5 GOF | 2B1 cell line | Mouse | BMP | Upregulation of BMP binding endothelial regulator (Bmper) | [13] |

| DNlg4 LOF | NMJ | Drosophila | BMP | Reduced growth of neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) with fewer synaptic boutons | [10] |

| EN2 GOF | Post-mortem samples | Human | SHH | Elevated SHH expression | [117] |

| FGF22/FGF7 LOF | Hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons | Mouse | FGF | Impaired synapse formation | [124] |

| FMRP depletion | COS-7 cells | Monkey | BMP | Increase in BMPR2 and activation of LIMK1, stimulates reorganization of actin to promote neurite outgrowth and synapse formation | [11] |

| FOXN1 | Human | RA | [135] | ||

| mGluR5 LOF | Cortical neurons | Mouse | FGF | Increased NGF and FGF10 mRNA levels | [125] |

| PGE2 | Differentiating neuronal cells | Humans | WNT (canonical) | Upregulation of WNT3 and TCF4 | [80, 93, 94] |

| PRICKLE2 LOF | Hippocampal neurons | Mouse | WNT (non-canonical) | Altered social interaction, learning abnormalities, and behavioral inflexibility | [40] |

| PTCHD1 LOF | Dentate gyrus | Mouse | SHH (hypothetical) | SHH independent; disrupted synaptic transmission | [109] |

| RERE | Human | RA | [137] | ||

| RORA LOF | Lymphoblastoid cell lines | Human | RA | Reduced protein levels of RORA and BCL-2 in autistic brain; aberrant methylation | [133] |

| TCF7L2 LOF | Human and mouse | WNT (canonical) | Required for thalamocortical axonal projection formation | [68–71] | |

| UBE3A GOF | Prefrontal cortex | Mouse | RA | Negative regulation of ALDH1A2; impaired RA-mediated synaptic plasticity | [139] |

| ube3a LOF | NMJ | Drosophila | BMP | Compromised endocytosis in the NMJs and an upregulated BMP signaling in the nervous system | [12] |

| UBE3AT485A LOF | HEK293T cells | Human | WNT (canonical) | Stabilizes nuclear β-catenin and stimulates canonical WNT signaling | [78] |

| WNT1, WNT2, WNT3, WNT9B | Human | WNT (canonical) | Elevated WNT3 expression in the prefrontal cortex of ASD patients | [34, 41–45] |

Fig. 1.

Possible interactions between ASD causal genes and WNT signaling. Most molecules (red) encoded by the ASD-associated genes are either core components of WNT signaling pathways, such as WNTs, APC, β-catenin, TCF7L2, and PRICKLE2, or their modulators, such as DIXDC1, PGE2, UBE3A, and CHD8. ANK3 interacts with β-catenin at the plasma membrane. Note: plus sign indicates upregulation; minus sign indicates downregulation

Core components of canonical WNT signaling

WNTs

Among 19 WNT ligands, mutations in WNT1, WNT2, WNT3, and WNT9B have been linked with ASD. A rare WNT1 missense variant found in ASD patients has a higher capability than the wild-type WNT1 to activate WNT/β-catenin signaling [34]. Rare variants in WNT2, WNT3, and WNT9B have also been found in ASD patients [41–44]. Notably, WNT3 expression is elevated in the prefrontal cortex of ASD patients [45], suggesting overactivation of WNT signaling leads to ASD pathogenesis. In animal models, Wnt1 is required for midbrain and cerebellar development [46–48]. Wnt2 has been shown to be sufficient for cortical dendrite growth and dendritic spine formation, and its expression is regulated by a brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [49], while altered dendritic spines result in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders [49]. Wnt3 is essential for gastrulation and regulates hippocampal neurogenesis [50, 51]. Loss-of-function of T-brain-1 (Tbr1), a T-box transcription factor and one of the high-confidence ASD risk genes, in cortical layer 6 neurons (Tbr1layer6 mutant) during late mouse gestation has been reported to cause a decrease in inhibitory synaptic density and excitatory synapse numbers [52]. It is important to note that the restoration of Wnt7b expression rescues the synaptic deficit in Tbr1layer6 mutant neurons [52]. Wnt9b promotes lip/palate formation and fusion [53, 54], while its role in neurodevelopment remains unclear. In addition to the other WNT ligands, there are various types of WNT receptors, including FZD1 to FZD10, LRP5/6, RYK, and ROR1/2 [30, 55], whose roles in ASD etiology remain elusive.

APC

The tumor suppressor APC is a key component of the β-catenin-destruction complex [56]. Human APC inactivating gene mutations have been linked to ASD [57, 58]. Compared with wild-type littermates, conditional knockout (cKO) Apc mice exhibit learning and memory impairment and autistic-like behaviors [1]. β-catenin and canonical WNT target gene expressions (Dkk1, Sp5, Neurog1, Syn2) are increased in Apc-cKO forebrain neurons [1]. Moreover, the lysates from the hippocampal, cortical, and striatal regions of Apc-cKO mice showed higher β-catenin levels compared to those of control mice [1]. These results also indicate that overactivation of WNT/β-catenin signaling may be a cause of ASD.

CTNNB1 (β-catenin)

β-Catenin is a key intracellular molecule in the canonical WNT signaling pathway and plays significant roles in development and disease [59, 60]. De novo CTNNB1 mutations have been reported in individuals with ASD, intellectual disability, microcephaly, motor delay, and speech impairment [36, 39, 61–63]. CTNNB1 haploinsufficiency has been found to cause neuronal loss, craniofacial anomalies, and hair follicle defects in both humans and mice [64]. Conditional ablation of β-catenin in the dorsal neural folds of mouse embryos represses the expression of Pax3 and Cdx2 at the dorsal posterior neuropore and leads to a decreased expression of the WNT/β-catenin signaling target genes T, Tbx6, and Fgf8 at the tail bud, resulting in spina bifida aperta, caudal axis bending, and tail truncation [65]. Conditional ablation of β-catenin in parvalbumin interneurons in mice leads to impaired object recognition and social interactions, as well as elevated repetitive behaviors, which are core symptoms of ASD patients, and surprisingly, they showed enhanced spatial memory [66]. These mice have reduced c-Fos activity in the cortex, which is unaffected in the dentate gyrus and the amygdala, suggesting a cell type-specific role of β-catenin in the regulation of cognitive and autistic-like behaviors [66].

TCF7L2 (TCF4)

TCF7L2 is one of the TCF/LEF1 transcription factors in the canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway and is associated with type II diabetes in humans [67]. De novo loss-of-function variants of TCF7L2 have been found in ASD patients [68, 69]. In mice, Tcf7l2 is required for the formation of thalamocortical axonal projections, as is the key Wnt co-receptor Lrp6 [70, 71], suggesting that abnormal thalamocortical axonal inputs may contribute to ASD. It remains unclear if other members of the TCF/Lef1 transcription factors are associated with ASD.

Core components of non-canonical WNT signaling

PRICKLE2

PRICKLE2 variants (p.E8Q and p.V153I) have been reported in ASD patients [40]. PRICKLE2’s role in ASD is further supported by the finding of a 3p interstitial deletion including PRICKLE2 in identical twins with ASD [72]. Prickle2-deficient mice display ASD-like phenotypes, such as altered social interaction, learning abnormalities, and behavioral inflexibility [40]. PRICKLE2 is known to interact with post-synaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95), and this relationship is enhanced by Vangl2, a key component in the non-canonical WNT/PCP (planar cell polarity) pathway [73]. Reduced dendrite branching, synapse number, and PSD size have been observed in hippocampal neurons of Prickle2-deficient mice [40]. An in vitro study shows that Prickle1 and Prickle2 promote neurite outgrowth via a Dvl-dependent mechanism [74]. Future works need to address the involvement of other PCP genes and the signaling interaction between the PCP and WNT/β-catenin signaling pathways in ASD etiology.

Modulators and effectors of WNT signaling in ASD etiology

Several ASD-associated genes are direct or indirect modulators of WNT signaling, such as ankyrin-G (ANK3) [75–77], chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 8 (CHD8) [5, 6], HECT domain E3 ubiquitin ligase (UBE3A) [78], DIX domain-containing 1 (DIXDC1) [79], and Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [80] (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Intriguingly, a recent study suggests that the ASD-associated gene Neuroligin 3 (Nlgn3) is a direct downstream target of WNT/β-catenin signaling during synaptogenesis [81] (Fig. 1).

ANK3

Whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing studies in ASD patients have identified mutations in ANK3 gene [75–77]. Ankyrin-G, a scaffolding protein encoded by ANK3 gene, localizes to the axon initial segment (AIS) and the nodes of Ranvier, where it has roles in the assembly and maintenance of the AIS and neuronal polarity [82, 83]. Ankyrin-G facilitates cell-cell contact by binding to E-cadherin at a conserved site distinct from that of β-catenin and localizes it to the cell adhesion site along with β-2-spectrin in early embryos and cultured epithelial cells [84]. Ankyrin-G is enriched at the ventricular zone of the embryonic brain, where it regulates the proliferation of neural progenitor cells [85]. Ankyrin-G LOF increases the proliferation of neural progenitor cells and nuclear β-catenin, probably by disruption of the β-catenin/cadherin interaction [85].

CHD8

CHD8, an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler, interacts with β-catenin and negatively regulates the expression of β-catenin-targeted genes [86]. CHD8 binding to p53 leads to the formation of a trimeric complex with histone H1 on chromatin, which suppresses p53-dependent transactivation and apoptosis during early embryogenesis [87]. CHD8 is also required for the expression of E2 adenovirus promoter-binding factor target genes during the G1/S transition of the cell cycle [88]. Chd8 gene knockout (Chd8−/−) in mice is embryonic lethal [87], whereas its heterozygous LOF mutations (Chd8+/−) result in mice with macrocephaly, craniofacial abnormalities, and behavioral deficits [89]. Its knockdown in SK-N-SH human neural progenitor cells alters the expression of genes involved in neuronal development [90]. WNT signaling is upregulated in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) region of the brain of Chd8+/− mice, highlighting the critical role CHD8 plays in the regulation of WNT signaling in the NAc [89].

UBE3A

Dysfunction of UBE3A is linked to autism, Angelman syndrome, and cancer [78]. UBE3AT485A, a de novo autism-linked UBE3A mutant that disrupts phosphorylative control of UBE3A activity, ubiquitinates multiple proteasome subunits, reduces proteasome subunit abundance and activity, stabilizes nuclear β-catenin, and stimulates canonical WNT signaling more effectively than the wild-type UBE3A [78].

DIXDC1

Rare missense variants in DIXDC1 were identified in ASD patients [79]. These variants prevent phosphorylation of DIXDC1 isoform 1, causing impairment to dendrite and spine growth [79]. DIXDC1 is a positive modulator for WNT signaling and regulates excitatory neuron dendrite development and synapse function in the mouse cortex [79]. MARK1, which is also linked to ASD, phosphorylates DIXDC1 to regulate dendrite and spine development through modulation of the cytoskeletal network in an isoform-specific manner [79]. Dixdc1-deficient mice exhibit behavioral disorders, including reduced social interaction, which can be alleviated through pharmacological inhibition of Gsk3 to upregulate WNT/β-catenin signaling [91, 92]. These studies suggest a potential approach to ASD treatment through manipulation of WNT/β-catenin signaling activities.

PGE2

PGE2, an endogenous lipid molecule, has been linked to ASD and alters the expression of downstream WNT-regulated genes previously associated with neurodevelopmental disorders [80]. The link between prostaglandin and autism came from the report of Möbius sequence with autism and positive history of misoprostol use during pregnancy [93]. The prostaglandin analog misoprostol is used as an abortifacient as well as for the prevention of gastric ulcers. Among seven children with ASD, four (57.1%) had prenatal exposure to misoprostol [93, 94]. In undifferentiated stem cells, PGE2 downregulates PTGS2 expression and upregulates MMP9 and CCND1 expression, whereas in differentiating neuronal cells, PGE2 causes upregulation of WNT3, TCF4, and CCND1 [80].

NLGN3

Mutations in neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 have been reported in autistic patients [95]. These type I transmembrane proteins are neural cell adhesion molecules and are required for the formation and development of synapses [10]. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and promoter luciferase assays demonstrate that WNT/β-catenin signaling directly regulates Nlgn3 expression [81]. It will be important to address whether WNT/β-catenin signaling regulates other ASD-associated genes.

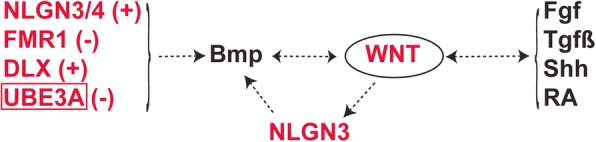

Altered TGF-β/BMP signaling in ASD

The TGF-β/activin and the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/growth and differentiation factor (GDF) are the two subgroups of TGF-β superfamily [96]. BMPs constitute the largest subdivision of the TGF-β superfamily [97] and are critical in the development of the nervous system [98]. Their signaling has been shown to be dysregulated in ASD. BMPs regulate the expression of various genes by the canonical pathway (Smad-dependent) and non-canonical pathways (such as MAPK cascade) [99]. In the canonical pathway, the binding of BMPs to type I or type II serine/threonine kinase receptors forms a heterotetrameric complex. This leads to the transphosphorylation of the type I receptor by the type II receptor. The type I receptor then phosphorylates the R-Smads (Smad1/5/8). The phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 along with the co-Smad (Smad4) translocate to the nucleus and regulate gene expression. There are various factors such as plasma membrane co-receptors and extracellular and intracellular factors known to modulate BMP signaling [99]. BTBR T+Itpr3tf/J (BTBR) mice are widely used in the study of ASD [17]. It has been reported that TGF-β levels are reduced in BTBR mice in comparison with B6 mice [17] (Table 1). Significant changes in the expression of TGF-β have been found in the spleen and brain tissues of BTBR mice compared to those in adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR) agonist CGS 21680 (CGS)-treated mice [17]. ASD has been linked with higher levels of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) in the blood [18] (Table 1). In a network-based gene set enrichment analysis (NGSEA), components of the TGF-β pathway have been identified as novel hyperserotonemia-related ASD genes, based on LOF and missense de novo variants (DNVs) [18].

NLGN4

Drosophila neuroligin 4 (DNlg4) LOF results in reduced growth of neuromuscular junctions (NMJs), with fewer synaptic boutons due to the reduction in the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type I receptor thickvein (Tkv) [10], suggesting important roles of BMP signaling in normal and autistic brains.

FMR1

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is the most common heritable form of intellectual disability and ASD, which is caused due to the silencing of FMR1 [11]. FMR1 protein (FMRP) depletion results in an increase in the bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor (BMPR2) and activation of a non-canonical BMP signaling component LIM domain kinase 1 (LIMK1), which stimulates reorganization of actin to promote neurite outgrowth and synapse formation [11]. Increased BMPR2 and LIMK1 activity has been reported in the prefrontal cortex of FXS patients compared with that of healthy subjects [11].

UBE3A

The inhibition of BMP signaling by Ube3a has been reported to play a role in the regulation of synapse growth and endocytosis [12]. A direct substrate of ube3a, the BMP receptor Tkv, is degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [12]. Drosophila ube3a has been known to regulate the NMJ development in the presynaptic neurons through the BMP signaling pathway [12]. Drosophila ube3a mutants have been shown viable and fertile. However, they display compromised endocytosis in the NMJs and upregulated BMP signaling in the nervous system due to an increase in Tkv [12].

DLX

The DLX genes encoding homeodomain transcription factors have been associated with ASD [100–102]. These genes control craniofacial patterning and differentiation and survival of forebrain inhibitory neurons [100]. The BMP-binding endothelial regulator (Bmper) has been found upregulated in a cell line overexpressing Dlx5 [13], suggesting dysregulated DLX function in ASD patients may lead to altered BMP signaling.

Altered SHH signaling in ASD

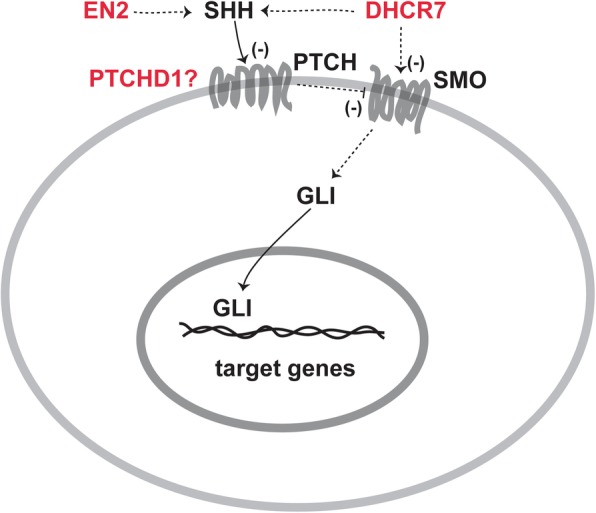

SHH plays a crucial role in the organization of the vertebrate brain [103]. SHH has a wide range of roles in developing as well as the adult brain and drives proliferation, specification, and axonal targeting within the forebrain, hindbrain, and spinal cord [104]. Although the role of neural primary cilia in embryonic CNS patterning is well studied, their role in adult CNS plasticity has recently emerged [105]. SHH signaling at the primary cilium has been described [106] and is summarized in Fig. 2. In the absence of SHH activity, PTCH represses SMO. This leads to the phosphorylation of GLI proteins, and their subsequent proteolytic truncation into repressor forms that inhibit transcriptional activity. However, the binding of SHH to PTCH causes its internalization followed by degradation which in turn leads to SMO accumulation and phosphorylation. In this case, GLI is transported to the cytosol and enters the nucleus in its full form, which further activates target transcription. Pathological roles of SHH, Indian hedgehog (IHH), and BDNF have been suggested in children with ASD [14]. SHH signaling influences neurogenesis and neural patterning during the development of the central nervous system. Dysregulation of SHH signaling in the brain leads to neurological disorders like ASD [15]. SHH has also been associated with oxidative stress in autism [107]. Significantly higher levels of oxygen free radicals (OFR) and serum SHH protein have been demonstrated in autistic children, suggesting a pathological role of oxidative stress and SHH in ASD [108]. Figure 2 summarizes the interaction between ASD causal genes and SHH signaling.

Fig. 2.

Possible interactions between ASD causal genes and SHH signaling. The genes encoded for PTCHD1, EN2, and DHCR7 are potential ASD genes. Note: minus sign indicates downregulation; question mark indicates undefined role of PTCHD1 in SHH signaling

PTCHD1

Mutations in the gene patched domain-containing 1 (PTCHD1) have been reported in ASD and ID patients [109]. Ptchd1 KO male mice exhibit cognitive alterations [109]. LOF experiments do not support a role for PTCHD1 protein in SHH-dependent signaling but reveal a disruption of synaptic transmission in the mouse dentate gyrus [109]. PTCHD1 has been shown to bind with the post-synaptic proteins PSD95 and SAP102 [110]. Ptchd1 deficiency in male mice (Ptchd1−/y) induces global changes in synaptic gene expression, affects the expression of the immediate-early expression genes Egr1 and Npas4, and impairs excitatory synaptic structure and neuronal excitatory activity in the hippocampus, leading to cognitive dysfunction, motor disabilities, and hyperactivity [110].

DHCR7

The impaired function of the cholesterol biosynthetic enzyme 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7) has been associated with the ASD [111]. The activation of the transmembrane protein Smoothened (SMO), through which SHH signaling is transduced, and its localization to the primary cilium is affected by conditions of reduced cholesterol biosynthesis [111].

EN2

The transcription factor engrailed2 (EN2) has been associated with ASD [112–116]. The increased levels of EN2 in affected individuals with EN2 ASD-associated haplotype (rs1861972-rs1861973 A-C) further support the susceptibility of EN2 gene for ASD [77, 117, 118]. The increased EN2 levels result in the elevated levels of the SHH expression as reported in post-mortem samples [117]. SHH is one of the genes flanking EN2 which is coexpressed during brain development [119, 120].

Altered FGF signaling in ASD

FGF signaling plays a crucial role in brain patterning, and its malfunction can result in various neurological disorders [121]. There are 18 secreted FGFs and 4 tyrosine kinase FGF receptors (FGFRs) reported in the mammalian FGF family whose interaction is regulated by cofactors and extracellular binding proteins [122]. Activation of FGFRs leads to the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues which further results in the interaction between cytosolic adaptor proteins and the RAS-MAPK, PI3K-AKT, PLCγ, and STAT intracellular signaling pathways [122]. Dysregulation of FGF signaling has been suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of ASD [16]. For instance, cortical abnormalities observed in autistic brains have been associated with defective FGF signaling [121, 123]. Perturbations in the number of excitatory and inhibitory synapses have been implicated in ASD [124]. Mutant mice lacking FGF22 or FGF7, which displayed impaired synapse formation in the hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons, have been reported [124], supporting the pathological role of dysregulated FGF signaling in ASD (Table 1). The metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) LOF results in aberrant dendritogenesis, one of the characteristics observed in autistic brains, in the cortical neurons by increasing nerve growth factor (NGF) and FGF10 mRNA levels [125] (Table 1).

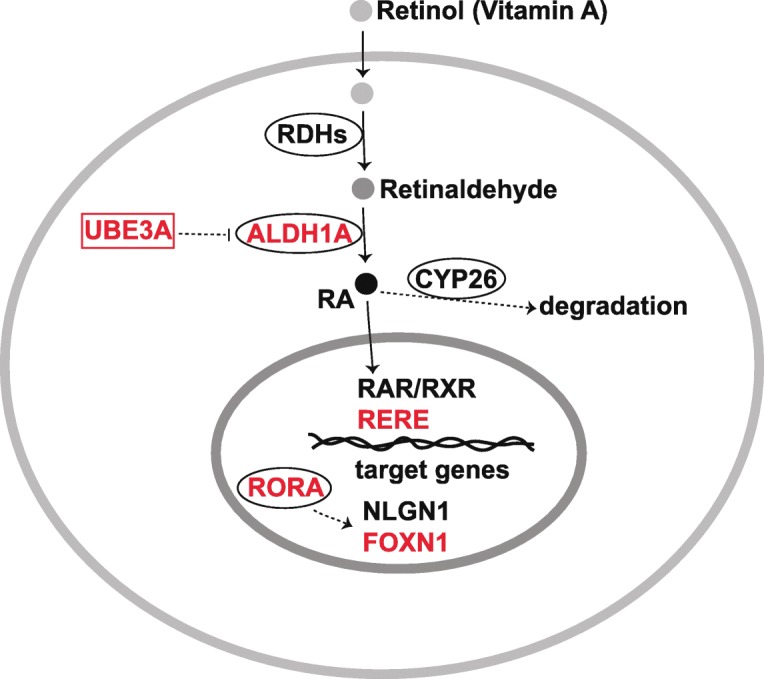

Altered retinoic acid signaling in ASD

Retinoic acid (RA), the functional metabolite of vitamin A, is an essential morphogen in vertebrate development [126, 127]. RA mediates both genomic transcriptional effects by binding to nuclear receptors called retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs) as well as non-genomic effects such as retinoylation (RA acylation), a post-translational modification of proteins [128, 129]. A range of co-activators and co-repressors have been reported in modulating RA signaling activity [129]. In the developing CNS, RA is required for neural patterning, differentiation, proliferation, and the establishment of neurotransmitter systems [130]. RA from the meninges regulates cortical neuron generation [131]. Vitamin A deficiency may induce ASD-like behaviors in rats [132]. It has been proposed that an abnormality in the interplay between retinoic acid and sex hormones may cause ASD [19]. Aberrant methylation and decreased protein expression of retinoic acid-related orphan receptor alpha (RORA) have been found in the autistic brain [133], while RORA variants have been associated with ASD [134]. Whole-exome sequencing in a South American cohort links RA signaling genes, including an RA-synthesizing gene aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A3 (ALDH1A3) and the RORA-regulated FOXN1 to ASD [135]. Low level of ALDH1A1 has been found in a subset of autistic patients [136]. De novo mutations in arginine-glutamic acid dipeptide repeats (RERE) that encode a nuclear receptor coregulator for RA signaling may cause ASD and other defects associated with proximal 1p36 deletions [137]. Genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that RORA transcriptionally regulates several ASD-relevant genes, including NLGN1 [138]. Intriguingly, overexpression of UBE3A represses ALDH1A2 and impairs RA-mediated synaptic plasticity in ASD, which can be alleviated by RA supplements [139]. All-trans-RA can upregulate the reduced CD38 expression in lymphoblastoid cell lines from ASD, while CD38-deficient mice exhibit ASD-like behavior [140, 141]. Beta-carotene, a precursor of vitamin A, has been shown as a potential treatment of autistic-like behavior in BTBR mice [142]. A synthetic RORA/G agonist has been tested to alleviate autistic disorders in a mouse model [143]. These studies suggest therapeutic approaches for treating ASD by targeting RA and related signaling pathways. The possible interactions among ASD causal genes and RA signaling have been described in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Possible interactions between ASD causal genes and RA signaling. UBE3A affects ALDH1A expression and thereby affects retinoic acid signaling pathway. RORA is associated with ASD which influences NLGN1. The RA signaling coregulator RERE is also associated with ASD

Non-genetic etiologies of ASD and altered signaling pathways

Various exogenous factors, such as prenatal exposure to viral infection or VPA, lead to several neurodevelopmental disorders with perturbed WNT signaling (Fig. 1). The transcription factor GATA-3 is critical for the brain development [144] and is involved in the WNT [145] and TGF-β/BMP [146, 147] signaling pathways. An increase in binding to GATA sites in DNA has been reported while exposure to thalidomide, valproate, and alcohol is known to cause ASD [148].

Viral infection

The infection with rubella in early pregnancy has been linked to autism in clinical and epidemiological studies [149]. Prenatal viral-like immune activation has recently been reported to induce stable hyper- and hypomethylated CpGs at WNT signaling genomic regions (WNT3, WNT7B, WNT8A) which further disrupt the transcription of downstream target genes [150], suggesting a potential role of epigenetic modulation of WNT signaling in ASD etiologies.

VPA

The use of the anticonvulsant valproic acid (VPA) during early pregnancy has been reported to cause autism in 11% children and autistic traits in an even larger number of children [151]. VPA is used in the treatment of epilepsy and bipolar disorder. However, rat prenatal exposure to VPA results in animals that are susceptible to autism-like phenotypes [20]. Prenatally VPA-treated rats exhibit an imbalance in oxidative homeostasis that facilitates susceptibility to autism [20, 152]. VPA treatment in rats resulted in lowered social interaction, longer moving time in the central area, and reduced standing times. Sulindac is a small molecule inhibitor of the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway [20, 152]. Sulindac treatment can correct the VPA-induced autistic-like behaviors, p-Gsk3β downregulation, and β-catenin upregulation in the prefrontal lobe, hippocampus, and cerebellum [152].

Conclusions

ASD causal genes may act upstream or downstream of WNT, BMP/TGFβ, SHH, FGF, and RA signaling pathways in vertebrates and invertebrates (Table 1 and Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4). Alteration in these signaling pathways during brain development seems to cause ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Previous studies support possible roles for these signaling pathways in the design of therapeutic targets for autism. However, systematic developmental studies are required to identify the temporal window in which impairment of these signals has the most significant impact on brain structure and function and resulting behavioral impairment. Such studies may also help in elucidating the upstream and downstream signaling pathways in the etiology of neurodevelopmental disorders as well as the mechanisms behind a particular impaired behavior. Although crosstalk among signaling pathways has been reported in several developmental processes and related diseases, similar studies in autistic models are lacking. Crosstalk between WNT and Hedgehog/Gli signaling in colon cancer has been studied and suggested as a potential target for its treatment [153]. β-Catenin and Gli1 are negatively regulated by GSK3β and CK1α [154–156] and have antagonistic roles in regulating TCF and downstream target genes in metastatic colon cancer [157]. The suppressor of the fused kinase (Sufu), a negative regulator of Gli1, has been reported to regulate the distribution of β-catenin in the nucleus and cytoplasm [158–160]. In colon cancer, loss of either PTEN or p53 leads to the activation of both β-catenin and Gli1 [157, 161]. The inhibition of SMO, an upstream active factor of Gli1, has been shown to reduce active β-catenin levels and induce its nuclear exclusion [162]. Gli1 negatively regulates Gli3R and vice versa [157]. Further, Gli3R has been shown to inhibit the activity of β-catenin [163]. The transcription of Wnt2b, Wnt4, and Wnt7b is shown to be induced by Gli1 [164]. The crosstalk between TGF-β and SHH pathways has also been reported in cancer [165], as well as in cyclosporine-enhanced cell proliferation in human gingival fibroblasts [166]. Neuropilin-1 (NRP1), a TGF-β co-receptor expressed on the membrane of cancer cells, is known to enhance the canonical SMAD2/3 signaling in response to TGF-β [167]. Further, HH signaling increases NRP1 transcription and NRP1 is also reported to increase the activation of HH target genes by mediating HH transduction between activated SMO and SUFU [168, 169]. While TGF-β is important for SMO-mediated cancer development [170], its role in the induction of GLI2 and GLI1 expression by inhibition of PKA activity has also been reported [171]. A hierarchical pattern of crosstalk has been suggested in which TGF-β upregulates Shh and leads to cyclosporine-enhanced Shh expression and cell proliferation in gingival fibroblasts [166]. Crosstalk between FGF and WNT pathways has been observed in zebrafish tailbud [172] and mouse craniofacial development [173]. Reciprocal positive regulation between FGF and WNT signaling has been observed [172]. WNT/β-catenin signaling in the anterior neural ridge and facial ectoderm has been shown to positively target Fgf8, and β-catenin GOF leads to ectopic expression of Fgf8 in the facial ectoderm [173]. Wnt has been reported to increase FGF signaling within the Mapk branch by elevating Erk phosphorylation levels [172]. Further, Fgf has been shown to inhibit the Wnt antagonists, dkk1 and notum1a, resulting in the elevation of WNT signaling [172]. A LOF mutation in UBE3A, an ASD-associated gene, influences both the WNT and BMP signaling pathways, suggesting possible crosstalk between them [12, 78]. Xu et al. further demonstrated that excessive UBE3A impairs RA-mediated neuronal synaptic plasticity in ASD probably by negative regulation of ALDH1A2, the rate-limiting enzyme of retinoic acid (RA) synthesis. [139]. Medina et al. [81] suggested that while Nlgn3 is a direct target of WNT/β-catenin signaling, the ASD-associated gene may also regulate BMP signaling. These results suggest that signaling crosstalk among morphogenetic pathways is mediated by autistic causal genes, thereby demonstrating value in further in-depth studies on interactions between signaling molecules in normal physiological and diseased conditions. Evidence has suggested a tissue-specific mechanism behind WNT and BMP signaling crosstalk [174]. Moreover, WNT signaling may repress RA signaling during orofacial development [175], while WNT signaling positively regulates RA signaling in the dorsal optic cup during eye development [176], suggesting context-dependent mechanisms of signaling interactions. Therefore, the interaction between various signaling pathways should be studied in neuronal as well as glial cells for ASD, which may help in designing treatment and targeting perturbed signaling in a cell-specific manner. Among the nine high-confidence ASD risk genes, only a few have been studied so far in the context of impaired signaling pathways. The investigation of roles for other ASD genes in neurodevelopment and in the regulation of various signaling pathways may increase the understanding of mechanisms behind the etiology of ASD. Overall, this article proposes to study how different ASD causal genes interact with each signaling pathway in the development of the brain and whether there is any crosstalk between them.

Fig. 4.

ASD causal genes affecting BMP signaling and potential crosstalk with other signaling pathways. ASD causal genes-encoded proteins, such as NLGN3/4, FMR1, DLX, and UBE3A, interact with BMP signaling pathway which may further affect WNT signaling. It should be noted that overexpression of UBE3A affects WNT and RA signaling pathways. However, its loss-of-function affects BMP signaling. Note: plus sign indicates upregulation; minus sign indicates downregulation

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the technical assistance from Rebecca Donham, Yue Liu, and Taylor Imai during the manuscript preparation.

Funding

The Zhou Laboratory is supported by grants from the NIH (R01NS102261 and R01DE026737 to CZ) and the Shriners Hospitals for Children (85105 and 86600 to CZ).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AIS

Axon initial segment

- ALDH1A3

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A3

- ANK3

Ankyrin-G

- APC

Adenomatous polyposis coli

- ASD

Autism spectrum disorder

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BMP

Bone morphogenetic protein

- Bmper

BMP binding endothelial regulator

- BMPR2

Bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor

- CHD8

Chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 8

- cKO

Conditional knockout

- CTNNB1

β-Catenin

- DHCR7

7-Dehydrocholesterol reductase

- DIXDC1

DIX domain containing 1

- DNlg4

Drosophila neuroligin 4

- DNVs

De novo variants

- EN2

Engrailed2

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- FMR1

Fragile X mental retardation 1

- FMRP

FMR1 protein

- FXS

Fragile X syndrome

- GOF

Gain-of-function

- hiPSC

Human induced pluripotent stem cell

- IHH

Indian hedgehog

- LIMK1

LIM domain kinase 1

- LOF

Loss-of-function

- mGluR5

Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5

- NAc

Nucleus accumbens

- NGF

Nerve growth factor

- NGSEA

Network-based gene set enrichment analysis

- NLGN

Neuroligins

- Nlgn3

Neuroligin 3

- NMJs

Neuromuscular junctions

- OFR

Oxygen free radicals

- PCP

Planar cell polarity

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- PTCHD1

Patched domain-containing 1

- RA

Retinoic acid

- RERE

Arginine-glutamic acid dipeptide repeats

- RORA

Retinoic acid-related orphan receptor alpha

- SHH

Sonic hedgehog

- SMO

Transmembrane protein Smoothened

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor β

- Tkv

BMP type I receptor thickvein

- UBE3A

Ubiquitin-protein ligase E3A

- VPA

Valproic acid

Authors’ contributions

KS conceptualized the subject, reviewed the literature, and wrote the draft manuscript. KR, YJ, RG, and SR assisted in the manuscript preparation. CZ initiated the topic, designed the figures, and revised and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Santosh Kumar, Email: samkumar@ucdavis.edu.

Kurt Reynolds, Email: ksreynolds@ucdavis.edu.

Yu Ji, Email: yvji@ucdavis.edu.

Ran Gu, Email: rangu@ucdavis.edu.

Sunil Rai, Email: skrrai@ucdavis.edu.

Chengji J. Zhou, Email: cjzhou@ucdavis.edu

References

- 1.Mohn JL, Alexander J, Pirone A, Palka CD, Lee SY, Mebane L, et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli protein deletion leads to cognitive and autism-like disabilities. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:1133–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Golden CE, Buxbaum JD, De Rubeis S. Disrupted circuits in mouse models of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2017;48:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werling DM, Brand H, An JY, Stone MR, Zhu L, Glessner JT, et al. An analytical framework for whole-genome sequence association studies and its implications for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Genet. 2018;50:727–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Kosmicki JA, Samocha KE, Howrigan DP, Sanders SJ, Slowikowski K, Lek M, et al. Refining the role of de novo protein-truncating variants in neurodevelopmental disorders by using population reference samples. Nat Genet. 2017;49:504–510. doi: 10.1038/ng.3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willsey AJ, Sanders SJ, Li M, Dong S, Tebbenkamp AT, Muhle RA, et al. Coexpression networks implicate human midfetal deep cortical projection neurons in the pathogenesis of autism. Cell. 2013;155:997–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cotney J, Muhle RA, Sanders SJ, Liu L, Willsey AJ, Niu W, et al. The autism-associated chromatin modifier CHD8 regulates other autism risk genes during human neurodevelopment. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6404. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae SM, Hong JY. The Wnt signaling pathway and related therapeutic drugs in autism spectrum disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2018;16:129–135. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2018.16.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalkman HO. A review of the evidence for the canonical Wnt pathway in autism spectrum disorders. Mol Autism. 2012;3:10. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulligan KA, Cheyette BNR. Neurodevelopmental perspectives on Wnt signaling in psychiatry. Mol Neuropsychiatry. 2016;2:219–246. doi: 10.1159/000453266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Rui M, Gan G, Huang C, Yi J, Lv H, et al. Neuroligin 4 regulates synaptic growth via the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:17991–18005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.810242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashima R, Roy S, Ascano M, Martinez-Cerdeno V, Ariza-Torres J, Kim S, et al. Augmented noncanonical BMP type II receptor signaling mediates the synaptic abnormality of fragile X syndrome. Sci Signal. 2016;9:ra58. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaf6060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W, Yao A, Zhi H, Kaur K, Zhu YC, Jia M, et al. Angelman syndrome protein Ube3a regulates synaptic growth and endocytosis by inhibiting BMP signaling in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Sajan SA, Rubenstein JLR, Warchol ME, Lovett M. Identification of direct downstream targets of Dlx5 during early inner ear development. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1262–1273. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halepoto DM, Bashir S, Zeina R, Al-Ayadhi LY. Correlation between hedgehog (Hh) protein family and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25:882–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel SS, Tomar S, Sharma D, Mahindroo N, Udayabanu M. Targeting sonic hedgehog signaling in neurological disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;74:76–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwata T, Hevner RF. Fibroblast growth factor signaling in development of the cerebral cortex. Develop Growth Differ. 2009;51:299–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2009.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ansari MA, Attia SM, Nadeem A, Bakheet SA, Raish M, Khan TH, et al. Activation of adenosine A2A receptor signaling regulates the expression of cytokines associated with immunologic dysfunction in BTBR T+Itpr3tf/J mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2017;82:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen R, Davis LK, Guter S, Wei Q, Jacob S, Potter MH, et al. Leveraging blood serotonin as an endophenotype to identify de novo and rare variants involved in autism. Mol Autism. 2017;8:14. doi: 10.1186/s13229-017-0130-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niculae AS, Pavăl D. From molecules to behavior: an integrative theory of autism spectrum disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2016;97:74–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Zhang Y, Sun Y, Wang F, Wang Z, Peng Y, Li R. Downregulating the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway attenuates the susceptibility to autism-like phenotypes by decreasing oxidative stress. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:1409–1419. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0724-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang SJ. Synaptic activity-regulated Wnt signaling in synaptic plasticity, glial function and chronic pain. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13:737–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Wada H, Okamoto H. Roles of noncanonical Wnt/PCP pathway genes in neuronal migration and neurulation in zebrafish. Zebrafish. 2009;6:3–8. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2008.0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wodarz A, Nusse R. Mechanisms of Wnt signaling in development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:59–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosso SB, Inestrosa NC. WNT signaling in neuronal maturation and synaptogenesis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:103. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bielen H, Houart C. The Wnt cries many: Wnt regulation of neurogenesis through tissue patterning, proliferation, and asymmetric cell division. Dev Neurobiol. 2014;74:772–780. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abu-Khalil A, Fu L, Grove EA, Zecevic N, Geschwind DH. Wnt genes define distinct boundaries in the developing human brain: implications for human forebrain patterning. J Comp Neurol. 2004;474:276–288. doi: 10.1002/cne.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bengoa-Vergniory N, Kypta RM. Canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling in neural stem/progenitor cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:4157–4172. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2028-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burden SJ. Wnts as retrograde signals for axon and growth cone differentiation. Cell. 2000;100:495–497. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inestrosa NC, Varela-Nallar L. Wnt signalling in neuronal differentiation and development. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;359:215–223. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1996-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onishi K, Hollis E, Zou Y. Axon guidance and injury-lessons from Wnts and Wnt signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;27:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okerlund ND, Cheyette BNR. Synaptic Wnt signaling-a contributor to major psychiatric disorders. J Neurodev Disord. 2011;3:162–174. doi: 10.1007/s11689-011-9083-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oron O, Elliott E. Delineating the common biological pathways perturbed by ASD’s genetic etiology: lessons from network-based studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:828. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwan V, Unda BK, Singh KK. Wnt signaling networks in autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. J Neurodev Disord. 2016;8:45. doi: 10.1186/s11689-016-9176-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin PM, Yang X, Robin N, Lam E, Rabinowitz JS, Erdman CA, et al. A rare WNT1 missense variant overrepresented in ASD leads to increased WNT signal pathway activation. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Hormozdiari F, Penn O, Borenstein E, Eichler EE. The discovery of integrated gene networks for autism and related disorders. Genome Res. 2015;25:142–154. doi: 10.1101/gr.178855.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krumm N, O’Roak BJ, Shendure J, Eichler EE. A de novo convergence of autism genetics and molecular neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grainger S, Willert K. Mechanisms of Wnt signaling and control. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2018:e1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Komiya Y, Habas R. Wnt signal transduction pathways. Organogenesis. 2008;4:68–75. doi: 10.4161/org.4.2.5851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Roak BJ, Vives L, Girirajan S, Karakoc E, Krumm N, Coe BP, et al. Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature. 2012;485:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sowers LP, Loo L, Wu Y, Campbell E, Ulrich JD, Wu S, et al. Disruption of the non-canonical Wnt gene PRICKLE2 leads to autism-like behaviors with evidence for hippocampal synaptic dysfunction. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:1077–1089. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wassink TH, Piven J, Vieland VJ, Huang J, Swiderski RE, Pietila J, et al. Evidence supporting WNT2 as an autism susceptibility gene. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:406–413. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marui T, Funatogawa I, Koishi S, Yamamoto K, Matsumoto H, Hashimoto O, et al. Association between autism and variants in the wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 2 (WNT2) gene. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:443–449. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709990903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin PI, Chien YL, Wu YY, Chen CH, Gau SS, Huang YS, et al. The WNT2 gene polymorphism associated with speech delay inherent to autism. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:1533–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Levy D, Ronemus M, Yamrom B, Lee Y, Leotta A, Kendall J, et al. Rare de novo and transmitted copy-number variation in autistic spectrum disorders. Neuron. 2011;70:886–897. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chow ML, Pramparo T, Winn ME, Barnes CC, Li HR, Weiss L, et al. Age-dependent brain gene expression and copy number anomalies in autism suggest distinct pathological processes at young versus mature ages. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Thomas KR, Capecchi MR. Targeted disruption of the murine int-1 proto-oncogene resulting in severe abnormalities in midbrain and cerebellar development. Nature. 1990;346:847–850. doi: 10.1038/346847a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McMahon AP, Bradley A. The Wnt-1 (int-1) proto-oncogene is required for development of a large region of the mouse brain. Cell. 1990;62:1073–1085. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90385-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McMahon AP, Joyner AL, Bradley A, McMahon JA. The midbrain-hindbrain phenotype of Wnt-1-/Wnt-1- mice results from stepwise deletion of engrailed-expressing cells by 9.5 days postcoitum. Cell. 1992;69:581–595. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90222-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hiester BG, Galati DF, Salinas PC, Jones KR. Neurotrophin and Wnt signaling cooperatively regulate dendritic spine formation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2013;56:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lie DC, Colamarino SA, Song HJ, Désiré L, Mira H, Consiglio A, et al. Wnt signalling regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nature. 2005;437:1370–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Liu P, Wakamiya M, Shea MJ, Albrecht U, Behringer RR, Bradley A. Requirement for Wnt3 in vertebrate axis formation. Nat Genet. 1999;22:361–365. doi: 10.1038/11932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fazel Darbandi S, Robinson Schwartz SE, Qi Q, Catta-Preta R, Pai EL, Mandell JD, et al. Neonatal Tbr1 dosage controls cortical layer 6 connectivity. Neuron. 2018;100:831–845.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Jin YR, Han XH, Taketo MM, Yoon JK. Wnt9b-dependent FGF signaling is crucial for outgrowth of the nasal and maxillary processes during upper jaw and lip development. Development. 2012;139:1821–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Juriloff DM, Harris MJ, McMahon AP, Carroll TJ, Lidral AC. Wnt9b is the mutated gene involved in multifactorial nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in A/WySn mice, as confirmed by a genetic complementation test. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006;76:574–579. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacDonald BT, He X. Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors for Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a007880. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou XL, Giacobini M, Anderlid BM, Anckarsäter H, Omrani D, Gillberg C, et al. Association of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene polymorphisms with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:351–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Barber JC, Ellis KH, Bowles LV, Delhanty JD, Ede RF, Male BM, et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli and a cytogenetic deletion of chromosome 5 resulting from a maternal intrachromosomal insertion. J Med Genet. 1994;31:312–316. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.4.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grigoryan T, Wend P, Klaus A, Birchmeier W. Deciphering the function of canonical Wnt signals in development and disease: conditional loss- and gain-of-function mutations of beta-catenin in mice. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2308–2341. doi: 10.1101/gad.1686208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuechler A, Willemsen MH, Albrecht B, Bacino CA, Bartholomew DW, van Bokhoven H, et al. De novo mutations in beta-catenin (CTNNB1) appear to be a frequent cause of intellectual disability: expanding the mutational and clinical spectrum. Hum Genet. 2015;134:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O’Roak BJ, Vives L, Fu W, Egertson JD, Stanaway IB, Phelps IG, et al. Multiplex targeted sequencing identifies recurrently mutated genes in autism spectrum disorders. Science. 2012;338:1619–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.1227764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sanders SJ, Murtha MT, Gupta AR, Murdoch JD, Raubeson MJ, Willsey AJ, et al. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature. 2012;485:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dubruc E, Putoux A, Labalme A, Rougeot C, Sanlaville D, Edery P. A new intellectual disability syndrome caused by CTNNB1 haploinsufficiency. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:1571–1575. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao T, Gan Q, Stokes A, Lassiter RNT, Wang Y, Chan J, et al. β-Catenin regulates Pax3 and Cdx2 for caudal neural tube closure and elongation. Development. 2014;141:148–157. doi: 10.1242/dev.101550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dong F, Jiang J, McSweeney C, Zou D, Liu L, Mao Y. Deletion of CTNNB1 in inhibitory circuitry contributes to autism-associated behavioral defects. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:2738–2751. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grant SFA, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, Benediktsson R, Manolescu A, Sainz J, et al. Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2006;38:320–323. doi: 10.1038/ng1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Rubeis S, He X, Goldberg AP, Poultney CS, Samocha K, Cicek AE, et al. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature. 2014;515:209–215. doi: 10.1038/nature13772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iossifov I, O’Roak BJ, Sanders SJ, Ronemus M, Krumm N, Levy D, et al. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2014;515:216–221. doi: 10.1038/nature13908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou CJ, Pinson KI, Pleasure SJ. Severe defects in dorsal thalamic development in low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-6 mutants. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7632–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Lee M, Yoon J, Song H, Lee B, Lam DT, Yoon J, et al. Tcf7l2 plays crucial roles in forebrain development through regulation of thalamic and habenular neuron identity and connectivity. Dev Biol. 2017;424:62–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Okumura A, Yamamoto T, Miyajima M, Shimojima K, Kondo S, Abe S, et al. 3p interstitial deletion including PRICKLE2 in identical twins with autistic features. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;51:730–733. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nagaoka T, Tabuchi K, Kishi M. PDZ interaction of Vangl2 links PSD-95 and Prickle2 but plays only a limited role in the synaptic localisation of Vangl2. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12916. doi: 10.1038/srep12916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fujimura L, Watanabe-Takano H, Sato Y, Tokuhisa T, Hatano M. Prickle promotes neurite outgrowth via the Dishevelled dependent pathway in C1300 cells. Neurosci Lett. 2009;467:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shi L, Zhang X, Golhar R, Otieno FG, He M, Hou C, et al. Whole-genome sequencing in an autism multiplex family. Mol Autism. 2013;4:8. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iqbal Z, Vandeweyer G, van der Voet M, Waryah AM, Zahoor MY, Besseling JA, et al. Homozygous and heterozygous disruptions of ANK3: at the crossroads of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:1960–1970. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bi C, Wu J, Jiang T, Liu Q, Cai W, Yu P, et al. Mutations of ANK3 identified by exome sequencing are associated with autism susceptibility. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1635–1638. doi: 10.1002/humu.22174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yi JJ, Paranjape SR, Walker MP, Choudhury R, Wolter JM, Fragola G, et al. The autism-linked UBE3A T485A mutant E3 ubiquitin ligase activates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by inhibiting the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:12503–12515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.788448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kwan V, Meka DP, White SH, Hung CL, Holzapfel NT, Walker S, et al. DIXDC1 phosphorylation and control of dendritic morphology are impaired by rare genetic variants. Cell Rep. 2016;17:1892–1904. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wong CT, Ussyshkin N, Ahmad E, Rai-Bhogal R, Li H, Crawford DA. Prostaglandin E2 promotes neural proliferation and differentiation and regulates Wnt target gene expression. J Neurosci Res. 2016;94:759–775. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Medina MA, Andrade VM, Caracci MO, Avila ME, Verdugo DA, Vargas MF, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling stimulates the expression and synaptic clustering of the autism-associated Neuroligin 3 gene. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:45. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0093-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hedstrom KL, Ogawa Y, Rasband MN. AnkyrinG is required for maintenance of the axon initial segment and neuronal polarity. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:635–640. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kordeli E, Lambert S, Bennett V. AnkyrinG. A new ankyrin gene with neural-specific isoforms localized at the axonal initial segment and node of Ranvier. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2352–2359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kizhatil K, Davis JQ, Davis L, Hoffman J, Hogan BLM, Bennett V. Ankyrin-G is a molecular partner of E-cadherin in epithelial cells and early embryos. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26552–26561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Durak O, de Anda FC, Singh KK, Leussis MP, Petryshen TL, Sklar P, et al. Ankyrin-G regulates neurogenesis and Wnt signaling by altering the subcellular localization of β-catenin. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:388–397. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thompson BA, Tremblay V, Lin G, Bochar DA. CHD8 is an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling factor that regulates beta-catenin target genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3894–3904. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00322-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nishiyama M, Oshikawa K, Tsukada Y, Nakagawa T, Iemura S, Natsume T, et al. CHD8 suppresses p53-mediated apoptosis through histone H1 recruitment during early embryogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:172–182. doi: 10.1038/ncb1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Subtil-Rodríguez A, Vázquez-Chávez E, Ceballos-Chávez M, Rodríguez-Paredes M, Martín-Subero JI, Esteller M, et al. The chromatin remodeller CHD8 is required for E2F-dependent transcription activation of S-phase genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:2185–2196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Platt RJ, Zhou Y, Slaymaker IM, Shetty AS, Weisbach NR, Kim JA, et al. Chd8 mutation leads to autistic-like behaviors and impaired striatal circuits. Cell Rep. 2017;19:335–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Wilkinson B, Grepo N, Thompson BL, Kim J, Wang K, Evgrafov OV, et al. The autism-associated gene chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 8 (CHD8) regulates noncoding RNAs and autism-related genes. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e568. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Martin PM, Stanley RE, Ross AP, Freitas AE, Moyer CE, Brumback AC, et al. DIXDC1 contributes to psychiatric susceptibility by regulating dendritic spine and glutamatergic synapse density via GSK3 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:467–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Kivimäe S, Martin PM, Kapfhamer D, Ruan Y, Heberlein U, Rubenstein JLR, et al. Abnormal behavior in mice mutant for the Disc1 binding partner, Dixdc1. Transl Psychiatry. 2011;1:e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Bandim JM, Ventura LO, Miller MT, Almeida HC, Costa AES. Autism and Möbius sequence: an exploratory study of children in northeastern Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2003;61:181–185. doi: 10.1590/S0004-282X2003000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Landrigan PJ. What causes autism? Exploring the environmental contribution. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:219–225. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328336eb9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jamain S, Quach H, Betancur C, Råstam M, Colineaux C, Gillberg IC, et al. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nat Genet. 2003;34:27–29. doi: 10.1038/ng1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zi Z, Chapnick DA, Liu X. Dynamics of TGF-β/Smad signaling. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1921–1928. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lowery JW, Rosen V. Bone morphogenetic protein-based therapeutic approaches. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10:a022327. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bond AM, Bhalala OG, Kessler JA. The dynamic role of bone morphogenetic proteins in neural stem cell fate and maturation. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72:1068–1084. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang RN, Green J, Wang Z, Deng Y, Qiao M, Peabody M, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in development and human diseases. Genes Dis. 2014;1:87–105. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hamilton SP, Woo JM, Carlson EJ, Ghanem N, Ekker M, Rubenstein JLR. Analysis of four DLX homeobox genes in autistic probands. BMC Genet. 2005;6:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu X, Novosedlik N, Wang A, Hudson ML, Cohen IL, Chudley AE, et al. The DLX1and DLX2 genes and susceptibility to autism spectrum disorders. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:228–235. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rubenstein JLR, Merzenich MM. Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2:255–267. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183X.2003.00037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Choy SW, Cheng SH. Hedgehog signaling. Vitam Horm. 2012;88:1–23. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394622-5.00001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Álvarez-Buylla A, Ihrie RA. Sonic hedgehog signaling in the postnatal brain. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;33:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kirschen GW, Xiong Q. Primary cilia as a novel horizon between neuron and environment. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12:1225–1230. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.213535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Seppala M, Fraser GJ, Birjandi AA, Xavier GM, Cobourne MT. Sonic hedgehog signaling and development of the dentition. J Dev Biol. 2017;5:6. doi: 10.3390/jdb5020006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ghanizadeh A. Malondialdehyde, Bcl-2, superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase may mediate the association of sonic hedgehog protein and oxidative stress in autism. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:899–901. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0667-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Al-Ayadhi LY. Relationship between sonic hedgehog protein, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and oxidative stress in autism spectrum disorders. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:394–400. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0624-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tora D, Gomez AM, Michaud JF, Yam PT, Charron F, Scheiffele P. Cellular functions of the autism risk factor PTCHD1 in mice. J Neurosci. 2017;37:11993–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 110.Ung DC, Iacono G, Méziane H, Blanchard E, Papon MA, Selten M, et al. Ptchd1 deficiency induces excitatory synaptic and cognitive dysfunctions in mouse. Mol Psychiatry. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 111.Blassberg R, Macrae JI, Briscoe J, Jacob J. Reduced cholesterol levels impair Smoothened activation in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:693–705. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Brune CW, Korvatska E, Allen-Brady K, Cook EH, Dawson G, Devlin B, et al. Heterogeneous association between engrailed-2 and autism in the CPEA network. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:187–193. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sen B, Singh AS, Sinha S, Chatterjee A, Ahmed S, Ghosh S, et al. Family-based studies indicate association of Engrailed 2 gene with autism in an Indian population. Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9:248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang L, Jia M, Yue W, Tang F, Qu M, Ruan Y, et al. Association of the ENGRAILED 2 (EN2) gene with autism in Chinese Han population. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:434–438. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yang P, Lung FW, Jong YJ, Hsieh HY, Liang CL, Juo SH. Association of the homeobox transcription factor gene ENGRAILED 2 with autistic disorder in Chinese children. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;57:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 116.Yang P, Shu B-C, Hallmayer JF, Lung FW. Intronic single nucleotide polymorphisms of engrailed homeobox 2 modulate the disease vulnerability of autism in a Han Chinese population. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62:104–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 117.Choi J, Ababon MR, Soliman M, Lin Y, Brzustowicz LM, Matteson PG, et al. Autism associated gene, engrailed2, and flanking gene levels are altered in post-mortem cerebellum. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gharani N, Benayed R, Mancuso V, Brzustowicz LM, Millonig JH. Association of the homeobox transcription factor, ENGRAILED 2, 3, with autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:474–484. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wechsler-Reya RJ, Scott MP. Control of neuronal precursor proliferation in the cerebellum by sonic hedgehog. Neuron. 1999;22:103–114. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Simon HH, Scholz C, O’Leary DDM. Engrailed genes control developmental fate of serotonergic and noradrenergic neurons in mid- and hindbrain in a gene dose-dependent manner. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Turner CA, Eren-Koçak E, Inui EG, Watson SJ, Akil H. Dysregulated fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;53:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ornitz DM, Itoh N. The fibroblast growth factor signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2015;4:215–266. doi: 10.1002/wdev.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Amaral DG, Schumann CM, Nordahl CW. Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Terauchi A, Johnson-Venkatesh EM, Toth AB, Javed D, Sutton MA, Umemori H. Distinct FGFs promote differentiation of excitatory and inhibitory synapses. Nature. 2010;465:783–787. doi: 10.1038/nature09041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Huang JY, Lu HC. mGluR5 tunes NGF/TrkA signaling to orient spiny stellate neuron dendrites toward thalamocortical axons during whisker-barrel map formation. Cereb Cortex. 2017:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 126.Niederreither K, Dollé P. Retinoic acid in development: towards an integrated view. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:541–553. doi: 10.1038/nrg2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rhinn M, Dollé P. Retinoic acid signalling during development. Development. 2012;139:843–858. doi: 10.1242/dev.065938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Das BC, Thapa P, Karki R, Das S, Mahapatra S, Liu TC, et al. Retinoic acid signaling pathways in development and diseases. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:673–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 130.Zieger E, Schubert M. New insights into the roles of retinoic acid signaling in nervous system development and the establishment of neurotransmitter systems. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2017;330:1–84. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Siegenthaler JA, Ashique AM, Zarbalis K, Patterson KP, Hecht JH, Kane MA, et al. Retinoic acid from the meninges regulates cortical neuron generation. Cell. 2009;139:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lai X, Wu X, Hou N, Liu S, Li Q, Yang T, et al. Vitamin a deficiency induces autistic-like behaviors in rats by regulating the RARβ-CD38-oxytocin axis in the hypothalamus. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018;62:1700754. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201700754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Nguyen A, Rauch TA, Pfeifer GP, Hu VW. Global methylation profiling of lymphoblastoid cell lines reveals epigenetic contributions to autism spectrum disorders and a novel autism candidate gene, RORA, whose protein product is reduced in autistic brain. FASEB J. 2010;24:3036–3051. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-154484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sayad A, Noroozi R, Omrani MD, Taheri M, Ghafouri-Fard S. Retinoic acid-related orphan receptor alpha (RORA) variants are associated with autism spectrum disorder. Metab Brain Dis. 2017;32:1595–1601. doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-0049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Moreno-Ramos OA, Olivares AM, Haider NB, de Autismo LC, Lattig MC. Whole-exome sequencing in a South American cohort links ALDH1A3, FOXN1 and retinoic acid regulation pathways to autism spectrum disorders. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Pavăl D, Rad F, Rusu R, Niculae AS, Colosi HA, Dobrescu I, et al. Low retinal dehydrogenase 1 (RALDH1) level in prepubertal boys with autism spectrum disorder: a possible link to dopamine dysfunction. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2017;15:229–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 137.Fregeau B, Kim BJ, Hernández-García A, Jordan VK, Cho MT, Schnur RE, et al. De novo mutations of RERE cause a genetic syndrome with features that overlap those associated with proximal 1p36 deletions. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:963–970. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sarachana T, Hu VW. Genome-wide identification of transcriptional targets of RORA reveals direct regulation of multiple genes associated with autism spectrum disorder. Mol Autism. 2013;4:14. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Xu X, Li C, Gao X, Xia K, Guo H, Li Y, et al. Excessive UBE3A dosage impairs retinoic acid signaling and synaptic plasticity in autism spectrum disorders. Cell Res. 2018;28:48–68. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Riebold M, Mankuta D, Lerer E, Israel S, Zhong S, Nemanov L, et al. All-trans retinoic acid upregulates reduced CD38 transcription in lymphoblastoid cell lines from autism spectrum disorder. Mol Med. 2011;17:799–806. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kim S, Kim T, Lee HR, Jang EH, Ryu HH, Kang M, et al. Impaired learning and memory in CD38 null mutant mice. Mol Brain. 2016;9:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 142.Avraham Y, Berry EM, Donskoy M, Ahmad WA, Vorobiev L, Albeck A, et al. Beta-carotene as a novel therapy for the treatment of “autistic like behavior” in animal models of autism. Behav Brain Res. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]