Abstract

Background:

Advances in fracture fixation and soft tissue coverage continue to improve the care of patients after limb-threatening lower extremity (LE) trauma. However, debate continues regarding which treatment option—reconstruction or amputation—is most appropriate. Many authors have attempted to quantify the patient experience in this treatment paradigm; however, they have not used patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments specific to this population. Our aim was to identify and evaluate PRO instruments developed specifically for LE trauma, applicable to reconstruction and amputation, using established PRO instrument development and validation guidelines.

Methods:

A multidisciplinary team used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses method to query PubMed, Medline Ovid, EMBASE, Cochrane, Medline Web of Science, and Psych Info databases from inception to November 2016. Publications were included that described the development and/or validation of a PRO instrument assessing satisfaction and/or quality of life in LE trauma, applicable to both amputation and reconstruction. Two authors independently reviewed each full-text citation.

Results:

After removing duplicates, 6,290 abstracts were identified via the database query. Following a preliminary title and abstract screen, 657 full-text citations were reviewed. Of these references, none satisfied the previously established inclusion criteria.

Conclusions:

No studies were identified that described a PRO instrument developed to assess outcomes in LE trauma patients applicable to both reconstruction and amputation. There is thus a need for a PRO instrument designed specifically for patients who have sustained limb-threatening LE trauma to guide treatment decisions.

INTRODUCTION

Severe lower extremity (LE) traumatic injuries are life-changing events. Treatment options include early amputation, limb reconstruction, or delayed amputation after reconstructive attempts; however, there is a no consensus regarding the best treatment modality.1–7 Successful reconstruction may involve numerous operations with a high rate of complications and long-term disability.3,8 However, amputation has its own limitations, including life-long reliance on a prosthesis for ambulation. In the setting of modern reconstructive microsurgery and orthopedic trauma care, the optimal treatment has not yet been established.

The impact of severe LE trauma is multidimensional. Traditional metrics including infection rates, postoperative complications, and pure functional assessments only capture a small portion of the experience borne by this patient population, neglecting outcomes such as return to work status, social integration, and substance abuse. A thorough assessment of the utility of amputation versus reconstruction must therefore be more comprehensive than the approach we have applied in the past to other surgical conditions, and therefore requires the development and application of a meaningful, appropriate patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument.

PRO instruments are broadly categorized into 2 groups: generic and disease specific. Generic instruments evaluate concepts of interest (COI) across a broad range of patient populations, allowing for a general comparison of health and well-being. Disease-specific PRO instruments capture COI relevant to the disease process and allow an assessment of change within these COI domains.11 Both types of PRO instruments are in contrast to ad hoc measures, which are a nonvalidated compilation of questions felt to be important by the research team and/or clinician.

Current PRO research in LE trauma has relied heavily upon generic measures, such as the SF-36 and Sickness Impact Profile. Disease-specific PRO instruments designed for populations other than LE trauma patients, such as the Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire (designed for amputees) and the Musculoskeletal (MSK) Tumor Society Scoring System (designed for MSK oncology) have also been used, along with ad hoc instruments.12–15 Although these instruments may offer some insight into LE trauma patient experiences, none have been rigorously developed for, or validated in, the LE trauma population. Therefore, these instruments lack the content validity required to fully capture all COI relevant to these patients.

Given the stakes of LE trauma decision-making—the significant length of time, use of resources, and potential morbidity associated with salvage, and the permanence of amputation—a disease-specific, valid, reliable instrument allowing comparison between these treatment conditions is essential. To identify and evaluate available options, we conducted a systematic review of the literature. Our primary aim was to identify PRO instruments developed specifically for LE trauma patients, applicable to both reconstruction and amputation patient cohorts. Our secondary aim was to evaluate any identified instruments based on established guidelines for PRO instrument development and validation.16

METHODS

Search Strategy

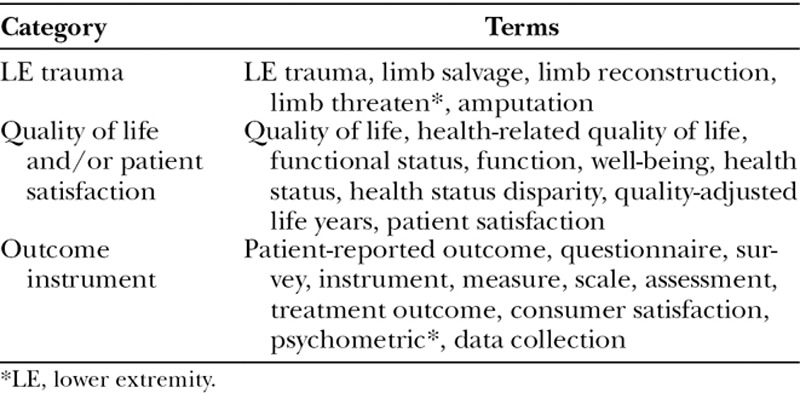

A comprehensive search was designed with the assistance of a medical librarian using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines to identify PRO instruments assessing quality of life and/or satisfaction for patients with LE traumatic injuries, applicable to both patients undergoing reconstruction and/or amputation.17 The search was conducted in PubMed, Medline Ovid, EMBASE, Cochrane, Medline Web of Science, and Psych Info, from inception to November 2016. Search terms were developed for LE trauma and outcome instruments, as listed in Table 1. The search terms were searched as text words and mapped to medical subject headings when applicable. Terms within each search category were combined with the Boolean operator OR, and the 3 categories were combined with AND.

Table 1.

Search Strategy

Selection Criteria

Publications were included if they were published in English and if they described the development and/or validation of a PRO instrument designed to measure satisfaction and/or quality of life in LE trauma patients, applicable to both amputation and reconstruction cohorts. Conference abstracts, theses, letters to the editor, editorials, and review articles were excluded. Secondary searching, including a citation review of applicable publications, was performed to identify additional instruments. Corresponding authors were contacted to obtain additional information if necessary.

Data Extraction

One author (L.R.M.) reviewed all titles and abstracts. All potentially applicable publications were reviewed as full-text by 2 authors (A.J.G. and L.R.M.). Any disagreements between A.J.G. and L.R.M. were resolved by consensus with the senior author (M.J.G.). All publications utilizing a PRO instrument that was not applicable to both amputation and reconstruction patients were excluded. Excluded citations were sorted into the following categories: ad hoc instruments, non-MSK PRO instruments, MSK PRO instruments not developed for LE trauma, MSK PRO instruments assessing functional outcomes only, PRO instruments specific to amputation patients only, LE PRO instruments specific to reconstruction only, and trauma PRO instruments not specific to the LE. Utilization frequencies of each PRO instrument in each category were also recorded.

RESULTS

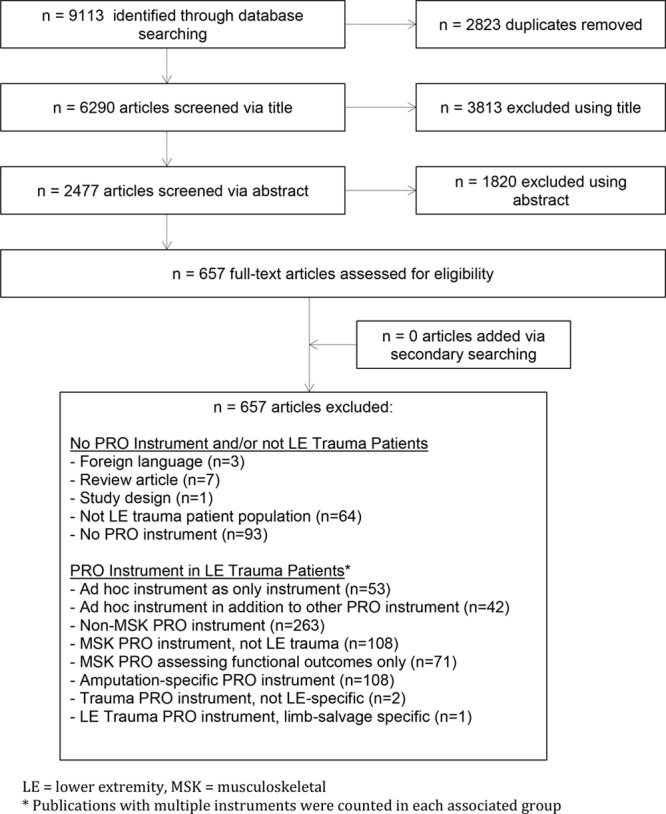

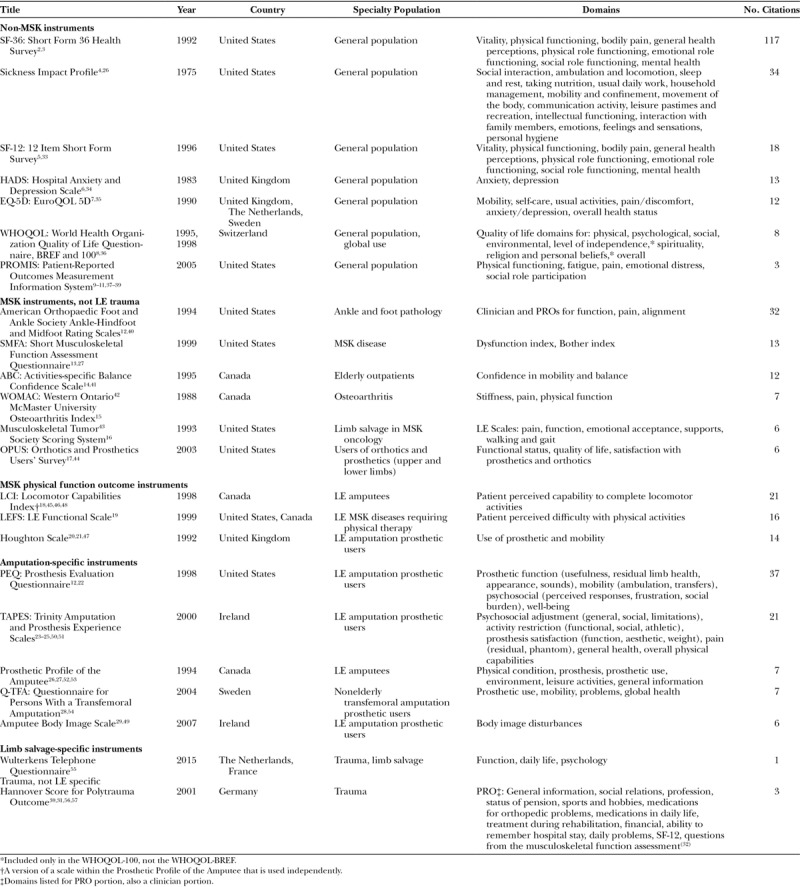

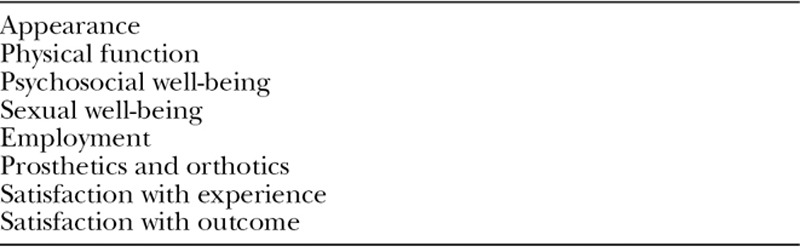

The results of the electronic search are shown in Figure 1. There were 9,113 publications identified in the search, with 6,290 publications after removal of duplications. After the initial title and abstract screen, there were 657 articles remaining, all of which were reviewed in full text and assessed for eligibility. There were no articles meeting inclusion criteria; none described a PRO instrument assessing outcomes in LE trauma patients that were applicable to both reconstruction patients and amputation patients. There were no additional articles added via secondary searching. Table 2 reports the most frequently utilized PRO instruments that are used to assess outcomes in LE trauma patients. The majority of studies utilized multiple PRO measures, with a combination of ad hoc measures, generic PRO instruments, and disease-specific PRO instruments. These instruments were most commonly designed for nontrauma MSK injuries and/or disease processes. Table 3 lists the proposed domains for a novel PRO instrument for LE trauma patients, based on the topics covered in the instruments listed here and expert opinion.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of systematic review. *Publications with multiple instruments were counted in each associated group.

Table 2.

Frequently Identified PRO Instruments Utilized for LE Trauma Patients

Table 3.

LE PRO Instrument Proposed Conceptual Framework

DISCUSSION

The decision to pursue reconstruction or amputation in the setting of limb-threatening LE trauma represents a significant challenge to both surgeons and patients. These injuries are often the result of high-energy mechanisms and patients present with extensive soft tissue loss, periosteal stripping, concomitant damage to neurovascular structures, and varying degrees of contamination.18 Early initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, wound debridement, rigid fracture stabilization, and soft tissue coverage has revolutionized the treatment of these injuries and led to increased rates of limb salvage.2,19,20 However, debate continues concerning who should undergo reconstruction versus amputation. Although each treatment group faces unique challenges, both groups have worse clinical and functional outcomes compared with the general population due to persistent wounds, multiple procedures, depression, pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, and, in the setting of amputees, difficulties with prostheses.21–25

The LE Assessment Project (LEAP) is the most comprehensive civilian study to date. This study attempted to determine whether amputated or salvaged patients had superior clinical, functional, and health-related quality of life outcomes using the Sickness Impact Profile.22,23,26 This prospective observational trial of 601 patients enrolled from 1994 to 1997 found no difference in clinical and functional outcomes or with health-related quality of life, patient satisfaction with treatment, or rates of returning to work. Worse outcomes, based on the Sickness Impact Profile, were alternatively correlated with patient and environmental factors independent of treatment pathway, including lower socioeconomic status, non-white race, tobacco use, using the legal system for injury compensation, and low levels of self-efficacy.

The Military Extremity Trauma Amputation/Limb Salvage (METALS) study attempted to answer the same question in a military population.24 A retrospective cohort study from 2003 to 2007 was performed on 324 service members who served in either Afghanistan or Iraq and who had suffered limb-threatening trauma to the LE. In addition to outcome measures for depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, chronic pain, and daily activities, general MSK PROs were evaluated with the Short Musculoskeletal Function Assessment (SMFA).27 In contrast to the LEAP study, amputees had higher SMFA scores and engagement in vigorous sports in comparison to reconstruction patients. Amputation patients also had lower rates of posttraumatic stress disorder, although both groups had equivalent rates of employment and depression. These findings reflected the higher levels of intensive postinjury rehabilitation services and access to prostheses and support devices provided to the military amputees, in comparison with both civilian amputees and military reconstruction patients.

The LEAP and METALS studies have improved our understanding of treatment outcomes in high-energy LE trauma patients, but a major limitation to the above studies is the use of the Sickness Impact Profile, a generic PRO instrument, and the SMFA, a general MSK PRO instrument. These measures are appropriate tools to compare outcomes between LE trauma patients and either the general population or patients with various MSK diseases besides LE trauma. However, they do not have the sensitivity to evaluate LE trauma-specific COI that is critical to make comprehensive inferences about LE trauma treatment outcomes. Qualitative interviews of LE trauma patients have identified numerous COI that are of importance to this population, which are not captured in the above measures. Physical function and symptoms, appearance, psychosocial and sexual well-being, social support, impact on family, perceptions of recovery, coping, self-efficacy, medical decision-making, the impact on work and education, and impact on finances have all been identified as COI in qualitative research of LE trauma patients.28–30

Although many of these COI may be addressed in various other PRO instruments or ad hoc measures, no instrument was found that comprehensively evaluates all COI relevant to LE trauma patients to allow for reproducible, rigorous comparisons between treatment outcomes. The most frequently observed paradigm was the use of a non–MSK-specific PRO instrument on patients with LE trauma (n = 266). It was also observed that authors often utilized an ad hoc instrument either alone (n = 61), or in addition to another PRO instrument (n = 44), in an attempt to describe the outcomes of their cohort. The frequency with which ad hoc instruments were employed further reinforces that there is a need for a metric capable of capturing and reporting severe LE trauma-relevant domains that are not adequately reflected in any of the currently available instruments.

With regards to study limitations, the results of this systematic review are dictated by the reliance upon the reviewed studies. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines were used to design our search query to reduce our risk of inadvertently omitting any studies that may be applicable to our hypothesis. However, missed relevant texts are possible. For those studies captured, the use of 2 separate reviewers reduced the possibility of selection bias from one reviewer.

CONSLUSIONS

The results of this systematic review highlight the need for a rigorously developed, reliable, and well-validated outcome instrument to better understand those with limb-threatening LE trauma. This tool would allow for the collection of more specific outcomes to this population. Additionally, it would provide a better understanding of the domains that are most important to limb-threatened patients and focus our clinical efforts to provide a greater impact on their outcomes.

Footnotes

Published online 3 May 2019.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Georgiadis GM, Behrens FF, Joyce MJ, et al. Open tibial fractures with severe soft-tissue loss. Limb salvage compared with below-the-knee amputation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1431–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gopal S, Majumder S, Batchelor AG, et al. Fix and flap: the radical orthopaedic and plastic treatment of severe open fractures of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naique SB, Pearse M, Nanchahal J. Management of severe open tibial fractures: the need for combined orthopaedic and plastic surgical treatment in specialist centres. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penn-Barwell JG, Myatt RW, Bennett PM, et al. ; Severe Lower Extremity Combat Trauma (SeLECT) Study Group. Medium-term outcomes following limb salvage for severe open tibia fracture are similar to trans-tibial amputation. Injury. 2015;46:288–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saddawi-Konefka D, Kim HM, Chung KC. A systematic review of outcomes and complications of reconstruction and amputation for type IIIB and IIIC fractures of the tibia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1796–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akula M, Gella S, Shaw CJ, et al. A meta-analysis of amputation versus limb salvage in mangled lower limb injuries—the patient perspective. Injury. 2011;42:1194–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busse JW, Jacobs CL, Swiontkowski MF, et al. ; Evidence-based Orthopaedic Trauma Working Group. Complex limb salvage or early amputation for severe lower-limb injury: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber CD, Hildebrand F, Kobbe P, et al. Epidemiology of open tibia fractures in a population-based database: update on current risk factors and clinical implications. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Economides JM, Patel KM, Evans KK, et al. Systematic review of patient-centered outcomes following lower extremity flap reconstruction in comorbid patients. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2013;29:307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinemann AW, Connelly L, Ehrlich-Jones L, et al. Outcome instruments for prosthetics: clinical applications. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25:179–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh SJ, Sodergren SC, Hyland ME, et al. A comparison of three disease-specific and two generic health-status measures to evaluate the outcome of pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD. Respir Med. 2001;95:71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, et al. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:931–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Toole RV, Castillo RC, Pollak AN, et al. ; LEAP Study Group. Determinants of patient satisfaction after severe lower-extremity injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1206–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoogendoorn JM, van der Werken C. Grade III open tibial fractures: functional outcome and quality of life in amputees versus patients with successful reconstruction. Injury. 2001;32:329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chmell MJ, McAndrew MP, Thomas R, et al. Structural allografts for reconstruction of lower extremity open fractures with 10 centimeters or more of acute segmental defects. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9:222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aaronson N, Alonso J, Burnam A, et al. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. ; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gustilo RB, Anderson JT. Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones: retrospective and prospective analyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, Quaba AA, et al. Locked intramedullary nailing of open tibial fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:959–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godina M. Early microsurgical reconstruction of complex trauma of the extremities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ, et al. Use and satisfaction with prosthetic devices among persons with trauma-related amputations: a long-term outcome study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80:563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Kellam JF, et al. An analysis of outcomes of reconstruction or amputation after leg-threatening injuries. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1924–1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Kellam JF, et al. Characterization of patients with high-energy lower extremity trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:455–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doukas WC, Hayda RA, Frisch HM, et al. The Military Extremity Trauma Amputation/Limb Salvage (METALS) study: outcomes of amputation versus limb salvage following major lower-extremity trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egeler SA, de Jong T, Luijsterburg AJM, et al. Long-term patient-reported outcomes following free flap lower extremity reconstruction for traumatic injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:773–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilson BS, Gilson JS, Bergner M, et al. The sickness impact profile. Development of an outcome measure of health care. Am J Public Health. 1975;65:1304–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swiontkowski MF, Engelberg R, Martin DP, et al. Short musculoskeletal function assessment questionnaire: validity, reliability, and responsiveness. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1245–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aravind M, Shauver MJ, Chung KC. A qualitative analysis of the decision-making process for patients with severe lower leg trauma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:2019–2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shauver MS, Aravind MS, Chung KC. A qualitative study of recovery from type III-B and III-C tibial fractures. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66:73–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trickett RW, Mudge E, Price P, et al. A qualitative approach to recovery after open tibial fracture: the road to a novel, patient-derived recovery scale. Injury. 2012;43:1071–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305(6846):160–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skevington SM, Sartorius N, Amir M. Developing methods for assessing quality of life in different cultural settings. The history of the WHOQOL instruments. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S14–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fries JF, Bruce B, Cella D. The promise of PROMIS: using item response theory to improve assessment of patient-reported outcomes. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S53–S57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, et al. ; PROMIS Cooperative Group. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S22–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kitaoka HB, Alexander IJ, Adelaar RS, et al. Clinical rating systems for the ankle-hindfoot, midfoot, hallux, and lesser toes. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powell LE, Myers AM. The Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50A:M28–M34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, et al. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, et al. A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinemann AW, Bode RK, O’Reilly C. Development and measurement properties of the Orthotics and Prosthetics Users’ Survey (OPUS): a comprehensive set of clinical outcome instruments. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2003;27:191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gauthier-Gagnon C, Grise M, Lepage Y. The locomotor capabilities index: content validity. J Rehabil Outcomes Meas. 1998;2:40–46. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, et al. The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network. Phys Ther. 1999;79:371–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Devlin M, Pauley T, Head K, et al. Houghton scale of prosthetic use in people with lower-extremity amputations: reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1339–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Houghton AD, Taylor PR, Thurlow S, et al. Success rates for rehabilitation of vascular amputees: implications for preoperative assessment and amputation level. Br J Surg. 1992;79:753–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallagher P, Horgan O, Franchignoni F, et al. Body image in people with lower-limb amputation: a Rasch analysis of the Amputee Body Image Scale. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86:205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gallagher P, MacLachlan M. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scales (TAPES). Rehabil Psychol. 2000;45:130. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gallagher P, MacLachlan M. The Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scales and quality of life in people with lower-limb amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gauthier-Gagnon C, Grisé MC. Prosthetic profile of the amputee questionnaire: validity and reliability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:1309–1314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grisé MC, Gauthier-Gagnon C, Martineau GG. Prosthetic profile of people with lower extremity amputation: conception and design of a follow-up questionnaire. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:862–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hagberg K, Brånemark R, Hägg O. Questionnaire for Persons with a Transfemoral Amputation (Q-TFA): initial validity and reliability of a new outcome measure. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2004;41:695–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wulterkens L, Aurégan JC, Letellier T, et al. A telephone questionnaire in order to assess functional outcome after post-traumatic limb salvage surgery: development and preliminary validation. Injury. 2015;46:2452–2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stalp M, Koch C, Ruchholtz S, et al. Standardized outcome evaluation after blunt multiple injuries by scoring systems: a clinical follow-up investigation 2 years after injury. J Trauma. 2002;52:1160–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stalp M, Koch C, Regel G, et al. Development of a standardized instrument for quantitative and reproducible rehabilitation data assessment after polytrauma (HASPOC). Chirurg. 2001;72:312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin DP, Engelberg R, Agel J, et al. Development of a musculoskeletal extremity health status instrument: the musculoskeletal function assessment instrument. J Orthop Res. 1996;14:173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]