Abstract

Epidemiological studies were controversial in the association between beverage intake and risk of Crohn disease (CD). This study aimed to investigate the role of beverage intake in the development of CD. A systematic search was conducted in public databases to identify all relevant studies, and study-specific relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were pooled using a random-effects model. Sixteen studies were identified with a total of 130,431 participants and 1933 CD cases. No significant association was detected between alcohol intake and CD risk (RR for the highest vs the lowest consumption level: 0.85, 95% CI 0.68–1.08), and coffee intake and the risk (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.46–1.46). High intake of soft drinks was associated with CD risk (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.01–1.98), and tea intake was inversely associated with CD risk (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.53–0.93). In conclusion, high intake of soft drinks might increase the risk of CD, whereas tea intake might decrease the risk.

Keywords: alcohol, coffee, Crohn disease, meta-analysis, soft drinks, tea

1. Introduction

Crohn disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the intestinal tract, which is clinically characterized by diarrhea, abdominal pain, and extra-intestinal manifestations.[1] During the past decades, its incidence is steadily on the rise across the world.[2] As it relapses frequently and has a high risk of surgery, the patients suffer from a low-quality life and high medical costs.[3] However, the etiology is still unknown, and it is hypothesized to result from a dysregulation of both the innate and adaptive immune response against the intestinal microecology in the genetically susceptible host.[4] In addition, growing evidence indicated that dietary factors might also play an important role in the development of CD.[5] In the meta-analysis by Li et al, high consumption of fruit was found to be inversely associated with the risk of CD (odds ratio [OR] 0.57, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.44–0.74).[6] In the meta-analysis by Zeng et al, dietary intake of total carbohydrate was associated with CD risk (relative risk [RR] for per 10 g increment/d 0.991, 95% CI 0.978–1.004), whereas fiber intake was inversely associated with CD risk (RR for per 10 g increment/d 0.853, 95% CI 0.762–0.955).[7]

During the past decades, the prevalence of westernized diet came along with an increasing incidence of CD in the regions with an originally low incidence.[8] Thus, westernized diet was usually regarded as a potential etiological factor for CD.[9] As 1 feature of the westernized diet, beverage intake might also play a certain role in the development of CD. However, the findings of previous epidemiological studies were inconsistent, and no meta-analyses have focused on this. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to identify the role of beverage intake in the development of CD.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Search strategy

The databases of PubMed, Embase, China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database (CNKI), and Cochrane Library databases were searched for relevant studies published up to December 1, 2018, using the key words “beverage,” “alcohol,” “wine,” “liquor,” “beer,” “coffee,” “tea,” “soda,” “soft drinks,” “diet,” “environmental factor,” “risk factor” in combination with “inflammatory bowel disease” and “Crohn disease.” Moreover, the references of related studies, reviews, and meta-analyses were also reviewed for undetected studies. This study was approved by the ethics committee of The Central Hospital of Enshi Autonomous Prefecture.

2.2. Study selection and exclusion

All the studies were reviewed independently by 2 investigators (Y.Y. and L.X.). Studies were included if they satisfied the following criteria: observational studies published originally; investigated the intake levels of at least one of the beverages (alcohol, coffee, tea, and soft drinks) by Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs); had a definite diagnosis for CD cases; the association between beverage intake and CD risk was evaluated by the effect sizes of RR, OR, or hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CI. Abstracts without full texts and review articles were excluded. In each included study, the protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each study center. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before registration, and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

The following information was extracted from each included study: first author, publication year, area, study design, number of cases and controls, beverage types, intake categories, exposure comparison, effect sizes, and adjustment. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), which contained 9 terms with each term accounting for 1 score, was used to assess the methodological quality of included studies.

2.4. Statistical analysis

As the absolute incidence of CD is low, OR was roughly regarded as RR in this meta-analysis.[10] To evaluate the risk of high beverage intake, we pooled the risk estimates for the highest versus the lowest intake levels. A random-effects model was used as the pooling method, which considered both within-study and between-study variation. The heterogeneity between studies was estimated by Q test and I2 statistic, and I2 >50% represented substantial heterogeneity.[11] Subgroup analysis was performed on cohort, study design, intake categories, and adjustment of dietary factors and smoking to evaluate the stability of the primary results. Altman and Bland test was performed to assess the difference between inconsistent subsets.[12] Egger test was used to detect publication bias.[13] All statistical analyses were performed using Stata SE12.0 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), and all tests were sided with a significance level of .05.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

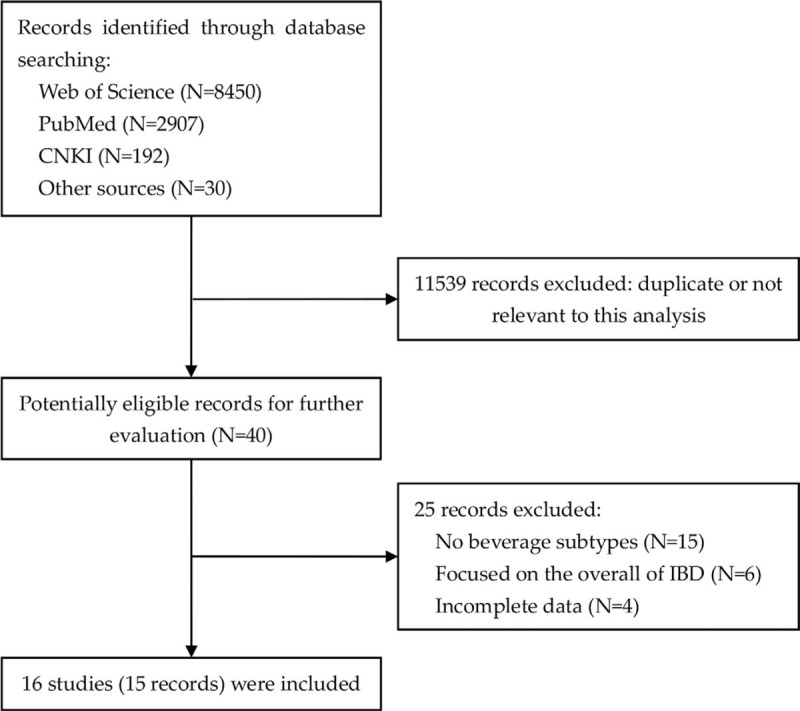

The search strategy identified 11,579 records: 8450 from Web of Science, 2907 from PubMed, 192 from CNKI, and 30 from other sources (Fig. 1). After eliminating duplicated and irrelevant records, 16 studies were included in the meta-analysis (Table 1).[14–28] The record of Khalili et al consisted of 2 large prospective studies. Among the 16 studies, there were 10 population and/or hospital-based case-control, 2 nested case-control, and 4 prospective cohort studies, with a total of 130,431 participants and 1933 CD cases. In study quality assessment, the quality scores ranged from 6 to 8, with an average of 7.25.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature search.

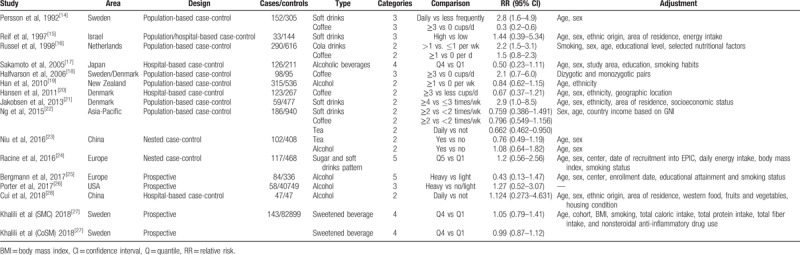

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

3.2. Alcohol intake and CD risk

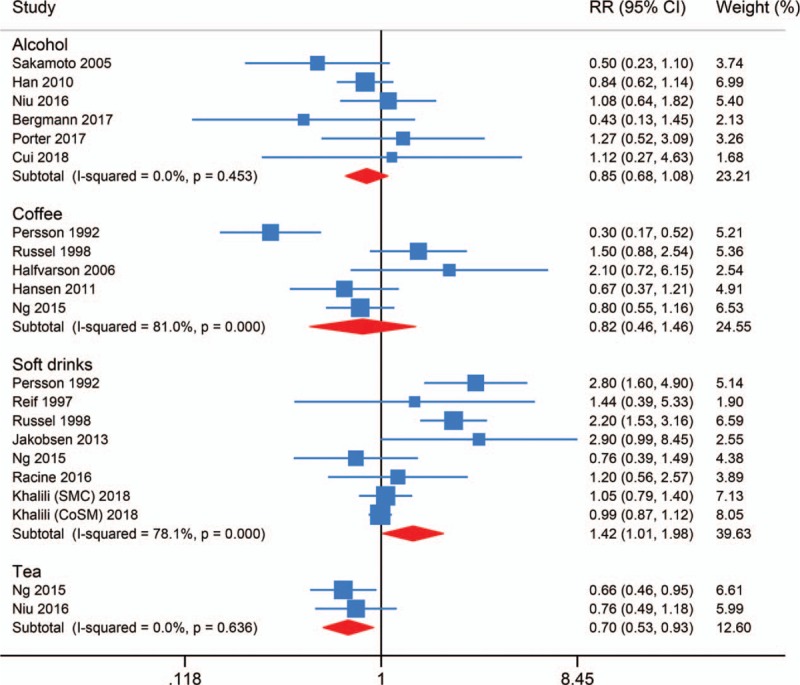

Six studies evaluated the association between alcohol intake and CD risk. The pooled RR for the highest versus the lowest intake was 0.85 (95% CI 0.68–1.08, I2 = 0.0%, Pheterogeneity = .453), indicating no obvious association between them (Fig. 2). Egger test detected significant publication bias (P = .992).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of beverage intake and risk of Crohn disease.

3.3. Coffee intake and CD risk

Five studies evaluated the association between coffee intake and CD risk. The pooled RR for the highest versus the lowest intake was 0.82 (95% CI 0.46–1.46, I2 = 81.0%, Pheterogeneity < .001), suggesting no obvious association between them (Fig. 2). Egger test detected no significant publication bias (P = .444).

3.4. Soft drinks intake and CD risk

Eight studies evaluated the association between soft drinks intake and CD risk, among which 1 focused on the subtype of cola drinks. The pooled RR for the highest versus the lowest intake was 1.42 (95% CI 1.01–1.98, I2 = 78.1%, Pheterogeneity < .001) (Fig. 2). High intake of soft drinks might increase the risk of CD. Egger test detected no significant publication bias (P = .140).

3.5. Tea intake and CD risk

Two studies evaluated the association between tea intake and CD risk. The pooled RR for the highest versus the lowest intake was 0.70 (95% CI 0.53–0.93, I2 = 0.0%, Pheterogeneity = .636) (Fig. 2). High intake of tea might decrease the risk of CD.

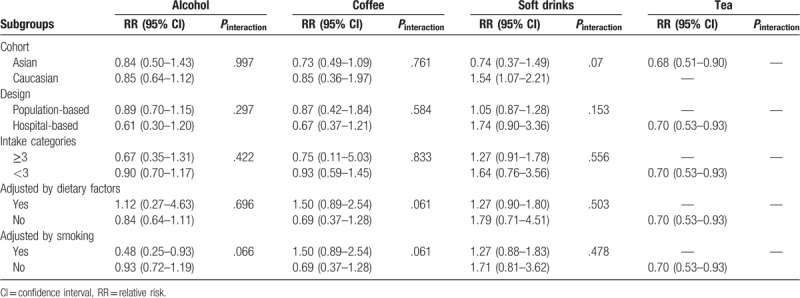

3.6. Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was performed on cohort, study design, intake categories, and adjustment of dietary factors and smoking to evaluate the stability of the primary results (Table 2). As the results were influenced by these factors except for the tea, Altman and Bland test was conducted to evaluate the difference between inconsistent subsets. Finally, no significant difference was found between these subsets (Pinteraction > .05). This indicated the inconsistency in subgroup analyses might contribute to the limited number of included studies, and the primary results were stable in general.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of beverage intake and risk of Crohn disease.

4. Discussion

The etiology of CD was still unknown, and it was hypothesized to result from multiple factors, like the ethnicity of Caucasian, and environmental factors of smoking, early-life antibiotic use, breastfeeding, childhood pet exposure, and urban residence.[29] Dietary factors were also known to be associated with CD. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to investigate the association between beverage intake and CD risk, and 4 most common daily subtypes were analyzed, respectively. For alcohol intake, it was not associated with CD risk (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.68–1.08). However, alcohol could cause direct mucosal injury and increase bacterial translocation, and it was usually regarded as the cause for intestinal inflammation.[30] The inconsistency might result from the difference between experimental studies and epidemiological studies, and the latter was confused by more factors. Just like fat intake, it was associated with experimental colitis, but epidemiological studies found an insignificant association with CD risk.[31]

Coffee intake also showed an insignificant association with CD risk (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.46–1.46). In vivo, mice treated with caffeine displayed a delayed response towards dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis.[32] We thought coffee intake might play different roles in the etiology and disease activity. For the inflammatory mucosa, it might play a protective role, but its role in pre-illness intestinal tract might be affected by multiple factors. As for the other subtype of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), coffee intake was also found in an insignificant association with ulcerative colitis (UC) (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.33–1.05).[33]

For the consumption of soft drinks, it was associated with CD risk (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.01–1.98). Soft drinks had been a highly visible and controversial public health issue, which were also viewed by many experts as a major contributor to obesity and related chronic diseases.[34,35] Soft drinks are rich in carbohydrate, especially sugar, and high sugar intake has been experimentally found in association with inflammation induction and gut microbiota alteration.[36,37] In the study by Opstelten et al, IBD patients consumed more carbonated beverages, and sugar and sweets than individuals from a general population (P < .05).[38] Thus, low intake of soft drinks might help decrease the incidence of CD, especially among the children. For CD patients, this strategy might help decrease the disease activity and the risk of relapse.

For tea consumption, it had a reverse association with CD (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.53–0.93). Animal studies found that tea alone or in combination with sulfasalazine could reduce inflammatory changes in experimental colitis, indicating a protective role of tea in CD.[39–41] Moreover, the presence of antioxidants in tea might also reduce the formation of free radicals that damaged cells in the body.[42] Thus, high intake of tea might help decrease the incidence of CD, especially among the adults. For CD patients, this strategy might help decrease the disease activity and the risk of relapse.

This meta-analysis had several strengths. First, this is the first meta-analysis to investigate the association between beverage intake and CD risk. Second, we evaluated the four most daily subtypes. There were also several limitations. First, the results based on case-control studies were prone to introduce considerable bias, particularly recall bias and interviewer bias. Second, there existed considerable heterogeneity in the meta-analyses of coffee and soft drinks, which might contribute to the limited number of included studies. Third, not all potential confounders were adjusted in every study. As health involves a dynamic process of adaptation to a constantly changing environment, supporting health and well-being is a multidimensional act that can be promoted and maintained by different ways of living, curative actions, mental interactions, public interventions, and global developments and crises, and also by the design of the setting.[43] Thus, environmental and social problems can lead to alcohol intake or intake of soft drinks, and different social circumstances can lead to the change of behaviors. In the future, we think a large-scale prospective designed study which considers these factors is needed to validate the role of beverage intake in the development of CD.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, high intake of soft drinks might increase the risk of CD, while tea intake might decrease the risk.

Author contributions

Data curation: Yanhua Yang.

Formal analysis: Yanhua Yang.

Investigation: Lili Xiang.

Methodology: Lili Xiang.

Software: Lili Xiang.

Supervision: Jianhua He.

Writing – original draft: Yanhua Yang.

Writing – review & editing: Jianhua He.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CD = Crohn disease, CI = confidence interval, FFQ = Food Frequency Questionnaire, IBD = inflammatory bowel disease, NOS = the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, OR = odds ratio, RR = relative risk, UC = ulcerative colitis.

Y.Y. and L.X. contributed equally to this study.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn's and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology 2013;145:158–65. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54. e42; quiz e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Niewiadomski O, Studd C, Hair C, et al. Health care cost analysis in a population-based inception cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients in the first year of diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:988–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2007;448:427–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Spooren CE, Pierik MJ, Zeegers MP, et al. Review article: the association of diet with onset and relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:1172–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Li F, Liu X, Wang W, et al. Consumption of vegetables and fruit and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;27:623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zeng L, Hu S, Chen P, et al. Macronutrient intake and risk of Crohn's disease: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Nutrients 2017;9: doi: 10.3390/nu9050500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz PP, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:1266–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ng SC, Bernstein CN, Vatn MH, et al. Geographical variability and environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2013;62:630–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 1998;280:1690–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ 2003;326:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Irwig L, Macaskill P, Berry G, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Graphical test is itself biased. BMJ 1998;316:470author reply -1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Persson PG, Ahlbom A, Hellers G. Diet and inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Epidemiology 1992;3:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Reif S, Klein I, Lubin F, et al. Pre-illness dietary factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 1997;40:754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Russel MG, Engels LG, Muris JW, et al. Modern life’ in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study with special emphasis on nutritional factors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998;10:243–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sakamoto N, Kono S, Wakai K, et al. Dietary risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease: a multicenter case-control study in Japan. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005;11:154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Halfvarson J, Jess T, Magnuson A, et al. Environmental factors in inflammatory bowel disease: a co-twin control study of a Swedish-Danish twin population. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:925–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Han DY, Fraser AG, Dryland P, et al. Environmental factors in the development of chronic inflammation: a case-control study on risk factors for Crohn's disease within New Zealand. Mutat Res 2010;690:116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hansen TS, Jess T, Vind I, et al. Environmental factors in inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study based on a Danish inception cohort. J Crohns Colitis 2011;5:577–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jakobsen C, Paerregaard A, Munkholm P, et al. Environmental factors and risk of developing paediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a population based study 2007-2009. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ng SC, Tang W, Leong RW, et al. Environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based case-control study in Asia-Pacific. Gut 2015;64:1063–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Niu J, Miao J, Tang Y, et al. Identification of environmental factors associated with inflammatory bowel disease in a southwestern highland region of China: a nested case-control study. PloS One 2016;11:e0153524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Racine A, Carbonnel F, Chan SS, et al. Dietary patterns and risk of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: results from the EPIC study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:345–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bergmann MM, Hernandez V, Bernigau W, et al. No association of alcohol use and the risk of ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease: data from a European Prospective cohort study (EPIC). Eur J Clin Nutr 2017;71:512–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Porter CK, Welsh M, Riddle MS, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease among participants of the Millennium Cohort: incidence, deployment-related risk factors, and antecedent episodes of infectious gastroenteritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:1115–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Khalili H, Hakansson N, Chan SS, et al. No association between consumption of sweetened beverages and risk of later-onset Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cui DJ, Yang LC, Yang XL, et al. Risk factors of Crohn's disease in Guizhou population. J Clin Pathol Res 2018;38:1913–6. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Aniwan S, Park SH, Loftus EV., Jr Epidemiology, natural history, and risk stratification of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2017;46:463–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang HJ, Zakhari S, Jung MK. Alcohol, inflammation, and gut-liver-brain interactions in tissue damage and disease development. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:1304–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wang F, Lin X, Zhao Q, et al. Fat intake and risk of ulcerative colitis: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;32:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lee IA, Low D, Kamba A, et al. Oral caffeine administration ameliorates acute colitis by suppressing chitinase 3-like 1 expression in intestinal epithelial cells. J Gastroenterol 2014;49:1206–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nie JY, Zhao Q. Beverage consumption and risk of ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Medicine 2017;96:e9070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ruanpeng D, Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, et al. Sugar and artificially sweetened beverages linked to obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. QJM 2017;110:513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, O’Corragain OA, et al. Associations of sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened soda with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology 2014;19:791–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Beilharz JE, Kaakoush NO, Maniam J, et al. The effect of short-term exposure to energy-matched diets enriched in fat or sugar on memory, gut microbiota and markers of brain inflammation and plasticity. Brain Behav Immun 2016;57:304–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Beilharz JE, Maniam J, Morris MJ. Short-term exposure to a diet high in fat and sugar, or liquid sugar, selectively impairs hippocampal-dependent memory, with differential impacts on inflammation. Behav Brain Res 2016;306:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Opstelten JL, de Vries JHM, Wools A, et al. Dietary intake of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a comparison with individuals from a general population and associations with relapse. Clin Nutr 2018;doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.06.983 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tang J, Zheng JS, Fang L, et al. Tea consumption and mortality of all cancers, CVD and all causes: a meta-analysis of eighteen prospective cohort studies. Br J Nutr 2015;114:673–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Byrav DS, Medhi B, Vaiphei K, et al. Comparative evaluation of different doses of green tea extract alone and in combination with sulfasalazine in experimentally induced inflammatory bowel disease in rats. Digest Dis Sci 2011;56:1369–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rahman SU, Li Y, Huang Y, et al. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease via green tea polyphenols: possible application and protective approaches. Inflammopharmacology 2018;26:319–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Megow I, Darvin ME, Meinke MC, et al. A Randomized controlled trial of green tea beverages on the in vivo radical scavenging activity in human skin. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2017;30:225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Leischik R, Dworrak B, Strauss M, et al. Plasticity of health. German J Med 2016;1:1–7. [Google Scholar]