Abstract

Membraneless organelles are distinct compartments within a cell that are not enclosed by a traditional lipid membrane and instead form through a process called liquid-liquid phase separation. Examples of these non-membrane-bound organelles include nucleoli, stress granules, P bodies, pericentriolar material and germ granules. Many recent studies have used Caenorhabditis elegans germ granules, known as P granules, to expand our understanding of the formation of these unique cellular compartments. From this work, we know that proteins with intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) play a critical role in the process of phase separation. IDR phase separation is further tuned through their interactions with RNA and through protein modifications such as phosphorylation and methylation. These findings from C elegans, combined with work done in other model organisms, continue to provide insight into the formation of membraneless organelles and the important role they play in compartmentalizing cellular processes.

Keywords: intrinsically disordered regions, liquid phase separation, non-membrane-bound organelles, P granules

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

The cell is comprised of many distinct compartments (or organelles) that partition cellular functions. Organelles can be subdivided into those encompassed by a lipid membrane (eg, nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, vacuoles and mitochondria) and those that are not (eg, nucleoli, stress granules, P bodies, pericentriolar material and germ granules). In the past decade, the dynamics of non-membrane-bound organelle partitioning and assembly have generated much interest, and for a good reason. Membraneless organelles can respond rapidly to fluctuations in temperature, pH and osmolarity without first requiring nuclear feedback and new synthesis of mRNA and protein. In addition, intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), protein domains that lack a distinct structural conformation, provide distinct microenvironments and solvent properties within these organelles that can concentrate and process very specific substrates, such as the different classes of RNA.1 The biophysics underlying membrane-less organelle partitioning and assembly are pervasive, and each new finding expands our understanding of cellular physiology and pathology beyond models that previously focused only on rigid protein structures with enzymatic functions.

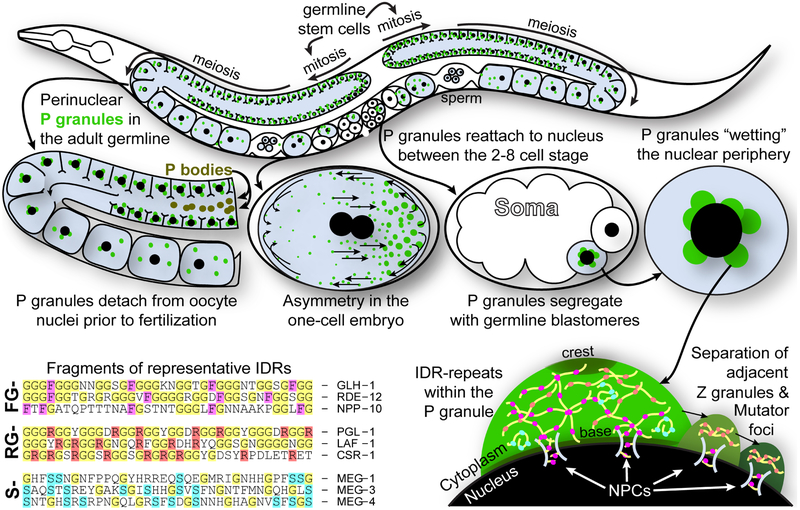

The functional dynamics of non-membrane-bound organelles during the course of development are best understood when they can be observed in living animals; however, in most cases, they are not accessible until animal cells, and tissues are disassociated, dissected and fixed. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans provides a solution to this challenge, as the animal’s transparency allows fluorescently tagged proteins of non-membrane-bound organelles to be visualized and tracked throughout development. One of the most visually striking and dynamic of these membraneless organelles are the germ granules. In C elegans, germ granules are called P granules because they segregate with germline blastomeres (the P lineage) during embryogenesis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

P granules in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. P granules (green) are shown in the germline (blue) of an adult. Germline stem cells (GSCs) proliferate in distal end of both gonad arms and are pushed from the stem cell niche where they enter meiosis. Each germ cell at this stage is attached to a common cytoplasm, and while similar but distinct P bodies are found in the syncytium, P granules remain at the periphery of each germ cell nucleus. As germ cells mature into oocytes and cellularize, P granules detach from the nuclear periphery and redistribute in the cytoplasm. During ovulation, oocytes pass through the spermatheca, become fertilized and enter the uterus. Fertilization initiates a cellular asymmetry cascade that culminates with P-granule condensation at the posterior of the cell before the first cell division. P granules segregate with germline blastomeres through four cell divisions, reattaching to the nucleus between the 2 and 8 cell stages. On the bottom left, representative IDRs from P-granule and NPC proteins are shown. A cartoon shows the complex heterogeneity of P granules, Z granules and Mutator foci at they sit at the nuclear periphery

Germ granules are a heterogeneous mix of RNA and protein.2 These organelles are found in the germline cytoplasm of almost all animals, and while the exact composition of germ granules varies across the phylogenetic tree, a conserved germ-granule core that includes Vasa, Tudor and Argonaut proteins can be found from C elegans to humans (with some noted exceptions such as flukes and tapeworms).3,4 P granules ensure the integrity of C elegans germ cells and are sites of small RNA biogenesis and post-transcriptional regulation.5 They help retain a memory of transcripts licensed for germline expression from one generation to the next, and while they seem to be dispensable for the specification of primordial germ cells (PGCs) in the early embryo, they are required for fertility in the adult.6-8 Taken together, the conservation and accessibility of P granules combined with the ease of editing the C elegans genome makes these nematodes a perfect genetic model for understanding membraneless organelle condensation, dissolution and dynamics across species. As many aspects of P-granule function have been extensively reviewed (see citations above), we will focus here on the pivotal advances from P-granule studies that have reshaped how we think about cytoplasmic microenvironments and non-membrane-bound organelles.

2 ∣. GRANULE MIGRATION TO LIQUID PHASE SEPARATION

P-granule dynamics were first observed with time-lapse imaging by Hird et al.9 after fluorescein-conjugated anti-P-granule monoclonals were injected into the C elegans germline. One-cell embryos from the injected nematodes showed posterior movement of individual P granules, but on reaching the posterior, they moved anteriorly along the cortex, following described patterns of cytoplasmic streaming. Importantly, the authors noted that P granules at the extreme anterior of the one-cell embryo did not move, but “progressively disappeared during mitosis”–something they attributed to disassembly or degradation in non-germline cytoplasm.

In the decade following this initial observation, Brangwynne et al10 observed that P-granule intensity is spatiotemporally controlled. They showed, for the first time, that the net flow of P granules traveling posteriorly is equal to those moving anteriorly along the cortex, but the symmetry is broken by a MEX-5 concentration gradient that somehow caused dissolution of anterior P granules and condensation of those in the posterior. They also showed that P granules behave similar to liquid droplets, exhibiting wetting-like interactions with the nuclear envelope instead of granule-like behavior. This paradigm-changing discovery exposed these “granules” as liquid droplets and was the catalyst for this past decade's quest to understand factors that regulate liquid phase separation of P granules and other non-membrane-bound organelles.

On the other hand, defining P granules as liquid droplets connotates homogeneity and fails to capture their enriched complexity. Electron microscopy has revealed that P granules in the adult germline have electron-dense bases and crests, and immunostaining shows an order of layers that connect P granules to the nuclear periphery.11 In the early embryo, the P-granule component MEG-3 forms a gel-like scaffold that provides a stable location that the more dynamic P-granule proteins adhere to.12,13 Later in embryogenesis when PGCs and their precursors form, P-granule components like ZNFX-1 and RDE-12 separate to form adjacent exogenous siRNA processing centers called Z granules and mutator foci (respectively), which persist as separate phases in the adult germline.14,15 Furthermore, some P-granule proteins are enriched and can exchange between processing bodies (P bodies) in the germline syncytium, while other P-granule and P-body proteins are exclusive to their respective membraneless organelles.16 The reason P granules, Z granules, mutator foci and P bodies occupy distinct cytoplasmic domains is still unclear. What defines multiple liquid droplets within the same cell, or layers and subdomains within a single liquid droplet, is the subject of ongoing research and likely has something to do with specific disordered protein motifs within the droplets.

3 ∣. INTRINSICALLY DISORDERED PROTEINS IN P-GRANULE ASSEMBLY

Approximately 44% of human protein-coding genes contain IDRs longer than 30 amino acids.17 IDRs contain low-complexity (glycine, serine and arginine-rich) sequences and repetitive motifs, and C elegans P-granule proteins are loaded with them.18 IDRs tend to phase separate in vitro, with properties ranging from liquids to hydrogels to amyloid-fibers and crystals.19 IDRs do not phase separate as readily in vivo, but new precision-generated IDR deletion alleles promise to clarify the endogenous function of these low-complexity regions. In some cases IDRs may confer the ability to switch back and forth between liquid, gel and solid states in a regulated fashion.20 Phase-separated IDRs can promote the recruitment of other IDR-containing proteins, which may explain why so many different types of IDRs are found in P granules.21

One IDR prevalent in P-granule proteins consists of FG-repeats–hydrophobic phenylalanine residues interspersed in glycine-rich domains every 10 to 15 amino acids (Figure 1). FG-repeats found in the P-granule associated DEAD-box helicase proteins GLH-1, GLH-2, GLH-4, RDE-12 and DDX-19, resemble the FG-repeats of nuclear pore complex (NPC) proteins.11 FG-nucleoporins (FG-Nups), establish the size exclusion barrier of NPCs, likely through the hydrophobicity of these regularly-spaced phenylalanines to form a mesh or “smart sieve”.22 In C elegans, FG-Nups are necessary to retain P-granule association with NPCs.23,24 P-granule FG-repeats extend the environment and size exclusion properties of the pore into the germline cytoplasm; as with FG-Nups, low concentrations of hexanediol readily disperse the weak hydrophobic interactions holding FG-rich GLH-1 granules together.25 Interestingly, some GLH-1 mutants that leave its FG-repeats intact still cause GLH-1 to dissociate from P granules.26 And, experiments driving the expression of GLH-1 outside the context of the C elegans germline do not result in phase separation unless the FG-repeat domain of GLH-1 is significantly lengthened or GLH-1 is seeded by other self-assembling P-granule proteins such as PGL-1 and PGL-3.25,27 Combined, these observations suggest that while FG-repeats contribute to the inherent properties of P granules and direct their association with the nuclear periphery, other nucleating factors are required for complete phase separation.

The self-assembling P-granule proteins PGL-1 and PGL-3 contain RG-repeats, a similar type of glycine-rich IDR where arginines, instead of phenylalanines, occur in regularly-spaced intervals (Figure 1). Shorter RG-repeat sequences are found in the DEAD-box helicases LAF-1 and VBH-1, the LSM14 family protein CAR-1, and the Argonaute proteins CSR-1, ALG-3, ALG-4 and HRDE-1, each of which at least transiently associates with P granules. RG-repeat proteins are not exclusive to P granules, but they do seem to have an affinity for membraneless organelles, such as the RGG-box protein FIB-1 (fibrillarin) in the nucleolus. These RG-repeats have been studied, traditionally, in the context of their non-sequence specific RNA-binding properties,28,29 while more recent studies have emphasized their role in self-assembly and phase separation.30 Despite the repulsive charge of arginines, they can form what are called planar Pi-Pi interactions with diglycines and other arginines, and these interactions increase in protein segments that lack secondary structure (ie, IDRs).31 PGL-1 and PGL-3 self-assemble through a separate self-interaction/dimerization domain, but their RG-repeat is essential to bind RNA and recruit other P-granule components.27,32,33

Because of the similarities between FG and RG-repeat domains, it is reasonable to wonder if they function redundantly in P granules and if they can be can be readily exchanged. Evolution provides some insight because the conserved germ-granule protein Vasa contains RG-repeats in insects, mammals and some flatworms, FG-repeats in nematodes and hydra, and a combination of FG, RG and other G-rich repeats in sponges, annelids, tardigrades and crustaceans. So, it appears RG and FG-repeats of Vasa have been exchanged multiple times throughout evolution without an obvious consequence. Similar to the FG-repeats of C elegans Vasa homolog GLH-1, in vitro experiments using the RG-repeats of the P-granule protein LAF-1 shows that this domain can also (a) establish a size exclusion barrier, and (b) enhance the ability to phase separate when artificially tethered together into a longer RG-repeat.34,35 Interestingly, both PGL-3 and LAF-1 droplets dissolve in high salt concentrations in vitro, suggesting that the positive charges distinguishing RG- from FG-repeats could confer added tunability to phase separation. For example, RG-repeats may respond to changes in the localized concentration of counteranions (such as RNA) or post-translational modifications (such as phosphorylation or methylation).30,35-37 A better understanding of (a) FG and RG-repeat exchangeability, and (b) how the RG-repeats of LAF-1, PGL-1 and PGL-3 are regulated during P-granule phase separation will be critical for discovering ways to manipulate phase separation of RG-repeat proteins in humans. For example, an imbalance causing cytoplasmic aggregation of a human RG-repeat protein called FUS is tied to both type 6 ALS and frontotemporal lobar dementias. Reversing these pathologies may be a matter of leveraging RG-repeat tunability.

The P-granule proteins MEG-1, MEG-2, MEG-3 and MEG-4 contain a third type of IDR consisting of a long, serine-rich N-terminus (Figure 1).12 MEG-3 and MEG-4 also contain an HMG-box in their structured C-terminal tail and share some homology with the ancient GCNA family of disordered proteins that function in the germline.38 All four MEGs are expressed in the early embryo and are required for proper germline development.39 MEG-3 and its IDR can phase separate in vitro at high concentrations, and in the early embryo, it functions upstream of PGL assembly, as will be discussed in detail below.

4 ∣. RNA AND POST-TRANSLATIONAL MODIFICATIONS IN P-GRANULE ASSEMBLY

RNA by itself can be a modulator of P-granule assembly, either as a counteranion for positively charged IDRs, as a tethering factor for multiple RNA-binding proteins, or most likely a combination of both. The simple addition of RNA to purified PGL-3 and MEG-3 can reduce the concentration of protein needed to induce phase separation in vitro.32,40 However, in the case of LAF-1, the in vitro formation of liquid droplets does not change with the addition of RNA. Instead, the addition of RNA causes a 3-fold reduction in LAF-1 droplet viscosity that is accompanied by an increase in the diffusive dynamics of proteins and RNA within the droplet.35 As to the relevance of these in vitro observations, we can turn to the phase separation dynamics of P-granule proteins in the one-cell embryo.

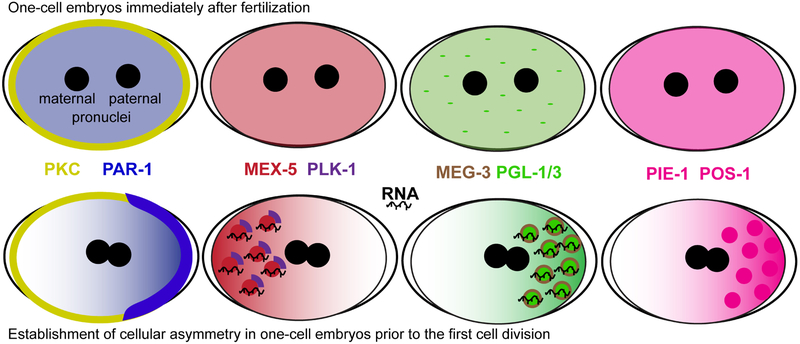

P-granule symmetry in the one-cell embryo is broken by the MEX-5 concentration gradient (Figure 2).41 PAR-1 mediated phosphorylation increases the rate of MEX-5 diffusion in the posterior end of the cell, but in the anterior, MEX-5 is stabilized by RNA-binding.41 Higher MEX-5 concentration in the anterior end of the cell antagonizes mRNA-induced phase separation of both PGL-3 and MEG-3.32,40 Because this activity depends on the ability of MEX-5 to bind RNA with its zinc finger domains, it has been proposed that this anteriorly stabilized MEX-5 acts as an RNA-sink, decreasing the pool of RNA available to PGL-3 and MEG-3, and thus antagonizing their ability to phase separate in the cell's anterior. In the posterior of the cell, the absence of MEX-5 allows PGL-3 and MEG-3 to bind RNA and stimulate P-granule condensation. This supports the in vitro studies showing the effect of RNA on the phase-separation; however, more recent findings suggest the story is more complex in vivo.

FIGURE 2.

Liquid-phase separation as symmetry breaks in the one-cell embryo. Embryos in the top panels demonstrate the symmetry of maternally inherited proteins just after fertilization and before maternal (left) and paternal (right) pronuclei meeting. The paternal pronucleus then migrates toward what will become the cell's posterior to initiate a cascade of events that result in PAR-1 enrichment at the posterior cortex. Embryos in the bottom panel are shown at a later point where maternal and paternal pronuclei migrate toward each other and meet. Posterior PAR-1 increases the diffusion rate of MEX-5, while slow diffusing MEX-5 in complex with PLK-1 and RNA phase separates in the cell's anterior. MEX-5's high affinity for RNA creates a potential RNA-sink, and this combined with the kinase activity of PLK-1 increases the rate of MEG-3, PIE-1 and POS-1 diffusion in the anterior, while slower diffusing MEG-3, PIE-1 and POS-1 phase separate in the posterior before the first cell division

If a MEX-5 RNA-sink alone is driving phase separation, the posterior condensation of both PGL-3 and MEG-3 should be independent events, but this does not seem to be the case. In vivo, MEG-3 posterior granules condense in the absence of PGL-1 and PGL-3, while in zygotes, lacking meg-3/4 PGL-1 granules remain symmetrically distributed, suggesting that MEG-3 functions upstream of PGL-1 condensation.13,40 Phospho-directed granule condensation was previously reported for MEG-3, which is a substrate for the kinase MBK-2 and the phosphatase PP2A, however it was unclear how asymmetry was achieved as both MBK-2 and PP2A are symmetrically distributed.12 A current model is that MEX-5 asymmetry is driven by posterior PAR-1, and that phosphorylation of MEX-5 by MBK-2 provides a binding site for PLK-1.42 When MEX-5 interacts with PLK-1 both proteins are relocalized to the anterior. Anterior PLK-1 kinase activity then either directly or indirectly increases POS-1, PIE-1 and MEG-3 mobility so these factors become posteriorly enriched.43-45 Posterior MEG-3 aggregates resemble a ribbon-like lattice that could then act as a scaffold for PGL assembly and granule formation.13,40 These models are provocative, but more data will be needed to rectify observations between early embryo and in vitro studies, especially in regards to the roles of IDRs and free RNA in enhancing phase separation.

Post-translational modifications of RG-repeats also drive P-granule dissolution outside of the germline, and in ways similar to RG-repeat regulation in humans. Altered arginine methylation of RG-repeat domains in human FUS contributes to the gain-of-function toxicity of ALS-linked FUS mutations.46 In normal conditions, PRMT1's methyltransferase activity antagonizes the cytoplasmic accumulation of FUS aggregates in motor neurons. Similarly, the phase-separating properties of Vasa in insects and mammals are fine-tuned through arginine methylation of its RG-repeat by the methyltransferases PRMT1 and PRMT5.47,48 PRMT1 has been shown to destabilize the phase separation of Vasa similarly to what is seen with human FUS.46 Furthermore, in the developing C elegans embryo, the PRMT1 homolog EPG-11 destabilizes and clears PGL-1 and PGL-3 aggregates from somatic blastomeres by direct methylation of their RG repeats, suggesting this type of tunability is conserved.37 These somatic PGL granules can reappear following heat shock, a response that depends on the TOR kinase LET-363, which directly phosphorylates PGL-1 and PGL-3 in vitro and induces phase separation at lower concentrations.36 Experiments such as these demonstrate the utility of C elegans and their P granules as a model for determining the specificity and extent that phosphoregulation and methylation impacts and tunes phase separation.

5 ∣. THE FUTURE OF P GRANULES AND NON-MEMBRANE-BOUND ORGANELLES

The drive for understanding how non-membrane organelles are formed and regulated is multifaceted. Research over the last decade has provided us with a better understanding of the layers of regulation that impact phase separation. We now know that proteins containing IDRs, such as FG or RG repeats, are particularly critical for promoting phase separation in vitro. IDRs are further tuned by interactions with RNA as well as phosphorylation or methylation, giving us insight into the complexity of how membraneless organelles form. However, many questions remain to be answered. How have specific proteins and IDRs been used over the course of evolution and development, and to what extent do they promote phase separation in vivo? Why do certain cytoplasmic processes, like small RNA biogenesis in P granules, need to be partitioned to maintain germ cell integrity? Do non-membrane-bound organelles confer resilience and adaptability during acute and prolonged stress? Can cytotoxic and pathological phase separations be safely reversed or tuned? Are IDRs viable targets for drug development? Can phase-separated organelles be used as solvents for molecular cargo delivery within the cell? The answer to these questions lies in the development of genetic model systems like C elegans to validate in vitro results and discover novel pathways that regulate the assembly of non-membrane-bound organelles. This applies not only to P granules but to P bodies, stress granules, pericentriolar material, meiotic synapses, nucleoli and other organelles assembled by cellular phase separations. Thus, answering these questions will not only help us understand the unique biological roles of membraneless organelles in animal development, but will offer novel insights into treating pathologies caused when phase separation goes awry.

Footnotes

EDITORIAL PROCESS FILE

The Editorial Process File is available in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nott TJ, Craggs TD, Baldwin AJ. Membraneless organelles can melt nucleic acid duplexes and act as biomolecular filters. Nat Chem. 2016; 8(6):569–575. 10.1038/nchem.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seydoux G The P granules of C. elegans: a genetic model for the study of RNA-protein condensates. J Mol Biol. 2018;430(23):4702–4710. 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skinner DE, Rinaldi G, Koziol U, Brehm K, Brindley PJ. How might flukes and tapeworms maintain genome integrity without a canonical piRNA pathway? Trends Parasitol. 2014;30(3):123–129. 10.1016/j.pt.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao M, Arkov AL. Next generation organelles: structure and role of germ granules in the germline. Mol Reprod Dev. 2012;80:610–623. 10.1002/mrd.22115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strome S, Updike D. Specifying and protecting germ cell fate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16(7):406–416. 10.1038/nrm4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirayama M, Seth M, Lee H-C, et al. piRNAs initiate an epigenetic memory of nonself RNA in the C. elegans germline. Cell. 2012;3:1–13. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallo CM, Wang JT, Motegi F, Seydoux G. Cytoplasmic partitioning of P granule components is not required to specify the germline in C. elegans. Science. 2010;330(6011):1685–1689. 10.1126/science.1193697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Updike DL, Knutson AK, Egelhofer TA, Campbell AC, Strome S. Germ-granule components prevent somatic development in the C. elegans germline. Curr Biol. 2014;24(9):970–975. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hird SN, Paulsen JE, Strome S. Segregation of germ granules in living Caenorhabditis elegans embryos: cell-type-specific mechanisms for cytoplasmic localisation. Development. 1996;122(4):1303–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brangwynne CP, Eckmann CR, Courson DS, et al. Germline P granules are liquid droplets that localize by controlled dissolution/condensation. Science. 2009;324(5935):1729–1732. 10.1126/science.1172046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheth U, Pitt J, Dennis S, Priess JR. Perinuclear P granules are the principal sites of mRNA export in adult C. elegans germ cells. Development. 2010;137(8):1305–1314. 10.1242/dev.044255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JT, Smith J, Chen B-C, et al. Regulation of RNA granule dynamics by phosphorylation of serine-rich, intrinsically-disordered proteins in C. elegans. eLife. 2014;3:e04591 10.7554/eLife.04591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Putnam A, Cassani M, Smith J, Seydoux G. A gel phase promotes condensation of liquid P granules in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2019;26:220–226. 10.1038/s41594-019-0193-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips CM, T a M, Breen PC, Ruvkun G. MUT-16 promotes formation of perinuclear mutator foci required for RNA silencing in the C. elegans germline. Genes Dev. 2012;26(13):1433–1444. 10.1101/gad.193904.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan G, Fields BD, Spracklin G, Shukla A, Phillips CM, Kennedy S. Spatiotemporal regulation of liquid-like condensates in epigenetic inheritance. Nature. 2018;557:679–683. 10.1038/s41586-018-0132-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallo CM, Munro E, Rasoloson D, Merritt C, Seydoux G. Processing bodies and germ granules are distinct RNA granules that interact in C. elegans embryos. Dev Biol. 2008;323(1):76–87. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oates ME, Romero P, Ishida T, et al. D2P2: database of disordered protein predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue): D508–D516. 10.1093/nar/gks1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uversky VN, Kuznetsova IM, Turoverov KK, Zaslavsky B. Intrinsically disordered proteins as crucial constituents of cellular aqueous two phase systems and coacervates. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(1):15–22. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han TW, Kato M, Xie S, et al. Cell-free formation of RNA granules: bound RNAs identify features and components of cellular assemblies. Cell. 2012;149(4):768–779. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toettcher JE, Shin Y, Pannucci N, Berry J, Brangwynne CP, Haataja MP. Spatiotemporal control of intracellular phase transitions using light-activated optoDroplets. Cell. 2016;168(1-2):159–171.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin Y, Protter DSW, Rosen MK, Parker R. Formation and maturation of phase-separated liquid droplets by RNA-binding proteins. Mol Cell. 2015;60(2):208–219. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt HB, Görlich D. Nup98 FG domains from diverse species spontaneously phase-separate into particles with nuclear pore-like permselectivity. eLife. 2015;4:1–30. 10.7554/eLife.04251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Updike DL, Strome S. A genomewide RNAi screen for genes that affect the stability, distribution and function of P granules in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2009;183(4):1397–1419. 10.1534/genetics.109.110171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voronina E, Seydoux G. The C. elegans homolog of nucleoporin Nup98 is required for the integrity and function of germline P granules. Development. 2010;137(9):1441–1450. 10.1242/dev.047654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Updike DL, Hachey SJ, Kreher J, Strome S. P granules extend the nuclear pore complex environment in the C. elegans germ line. J Cell Biol. 2011;192(6):939–948. 10.1083/jcb.201010104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spike C, Meyer N, Racen E, et al. Genetic analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans GLH family of P-granule proteins. Genetics. 2008;178(4):1973–1987. 10.1534/genetics.107.083469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanazawa M, Yonetani M, Sugimoto A. PGL proteins self associate and bind RNPs to mediate germ granule assembly in C. elegans. J Cell Biol. 2011;192(6):929–937. 10.1083/jcb.201010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burd CG, Dreyfuss G. Conserved structures and diversity of functions of RNA-binding proteins. Science. 1994;265(5172):615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Järvelin AI, Noerenberg M, Davis I, Castello A. The new (dis)order in RNA regulation. Cell Commun Signal. 2016;14(1):9 10.1186/s12964-016-0132-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chong PA, Vernon RM, Forman-Kay JD. RGG/RG motif regions in RNA binding and phase separation. J Mol Biol. 2018;430(23):4650–4665. 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vernon RM, Chong PA, Tsang B, et al. Pi-pi contacts are an overlooked protein feature relevant to phase separation. eLife. 2018;7:e31486 10.7554/eLife.31486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saha S, Weber CA, Nousch M, et al. Polar positioning of phase-separated liquid compartments in cells regulated by an mRNA competition mechanism. Cell. 2016;166(6):1572–1584.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aoki ST, Kershner AM, Bingman CA, Wickens M, Kimble J. PGL germ granule assembly protein is a base-specific, single-stranded RNase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;133:1–6. 10.1073/pnas.1524400113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuster BS, Reed EH, Parthasarathy R, et al. Controllable protein phase separation and modular recruitment to form responsive membraneless organelles. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2985 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.11.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elbaum-Garfinkle S, Kim Y, Szczepaniak K, et al. The disordered P granule protein LAF-1 drives phase separation into droplets with tunable viscosity and dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112:7189–7194. 10.1073/pnas.1504822112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang G, Wang Z, Du Z, Zhang H. mTOR regulates phase separation of PGL granules to modulate their autophagic degradation. Cell. 2018; 174(6):1492–1506.e22. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li S, Yang P, Tian E, Zhang H. Arginine methylation modulates autophagic degradation of PGL granules in C. Elegans. Mol Cell. 2013;52 (3):421–433. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carmell MA, Dokshin GA, Skaletsky H, et al. A widely employed germ cell marker is an ancient disordered protein with reproductive functions in diverse eukaryotes. eLife. 2016;5(October 2016):1–25. 10.7554/eLife.19993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leacock SW, Reinke V. MEG-1 and MEG-2 are embryo-specific P-granule components required for germline development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2008;178(1):295–306. 10.1534/genetics.107.080218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith J, Calidas D, Schmidt H, Lu T, Rasoloson D, Seydoux G. Spatial patterning of P granules by RNA-induced phase separation of the intrinsically-disordered protein MEG-3. elife. 2016;5:e21337 10.7554/eLife.21337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffin EE, Odde DJ, Seydoux G. Regulation of the MEX-5 gradient by a spatially segregated kinase/phosphatase cycle. Cell. 2011;146(6):955–968. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishi Y, Rogers E, Robertson SM, Lin R. Polo kinases regulate C. elegans embryonic polarity via binding to DYRK2-primed MEX-5 and MEX-6. Development. 2008;135(4):687–697. 10.1242/dev.013425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Y, Han B, Li Y, Munro E, Odde DJ, Griffin EE. Rapid diffusion-state switching underlies stable cytoplasmic gradients in the Caenorhabditis elegans zygote. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(36): E8440–E8449. 10.1073/pnas.1722162115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu Y, Han B, Gauvin TJ, Smith J, Singh A, Griffin EE. Single molecule dynamics of the P granule scaffold MEG-3 in the C. elegans zygote. Mol Biol Cell. 2018;30:333–345. 10.1091/mbc.E18-06-0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han B, Antkowiak KR, Fan X, Rutigliano M, Ryder SP, Griffin EE. Polo-like kinase couples cytoplasmic protein gradients in the C. elegans zygote. Curr Biol. 2018;28(1):60–69.e8. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tradewell ML, Yu Z, Tibshirani M, Boulanger M-C, Durham HD, Richard S. Arginine methylation by PRMT1 regulates nuclear-cytoplasmic localization and toxicity of FUS/TLS harbouring ALS-linked mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(1):136–149. 10.1093/hmg/ddr448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirino Y, Vourekas A, Kim N, et al. Arginine methylation of vasa protein is conserved across phyla. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(11):8148–8154. 10.1074/jbc.M109.089821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nott TJ, Petsalaki E, Farber P, et al. Phase transition of a disordered nuage protein generates environmentally responsive membraneless organelles. Mol Cell. 2015;57(5):936–947. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]