Key Points

Carp macrophages exhibit a trained immunity-like profile in vitro.

Both peptidoglycan and β-glucan can induce trained immunity in carp macrophages.

Abstract

Trained immunity is a form of innate immune memory best described in mice and humans. Clear evidence of the evolutionary conservation of trained immunity in teleost fish is lacking. Given the evolutionary position of teleosts as early vertebrates with a fully developed immune system, we hypothesize that teleost myeloid cells show features of trained immunity common to those observed in mammalian macrophages. These would at least include the ability of fish macrophages to mount heightened responses to a secondary stimulus in a nonspecific manner. We established an in vitro model to study trained immunity in fish by adapting a well-described culture system of head kidney–derived macrophages of common carp. A soluble NOD-specific ligand and a soluble β-glucan were used to train carp macrophages, after which cells were rested for 6 d prior to exposure to a secondary stimulus. Unstimulated trained macrophages displayed evidence of metabolic reprogramming as well as heightened phagocytosis and increased expression of the inflammatory cytokines il6 and tnf-α. Stimulated trained macrophages showed heightened production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species as compared with the corresponding stimulated but untrained cells. We discuss the value of our findings for future studies on trained immunity in teleost fish.

Introduction

Traditionally, innate immune responses have been viewed as rapid, relatively nonspecific, and lacking immunological memory. New insights have challenged this view, introducing a novel concept referred to as trained immunity, which is defined as a heightened response to a secondary infection that can be exerted toward both homologous and heterologous microorganisms (1). Typical criteria of trained immunity include the following: 1) induction upon primary infections or immunizations and subsequent protection against a secondary infection in a T and B lymphocyte–independent manner, 2) a response that is less specific than an adaptive immune response but that still confers increased resistance upon reinfection of the host and, 3) the involvement of innate cell types, such as NK cells and macrophages, involved in improved pathogen recognition and an increased inflammatory response.

Initial experiments showed that Rag−/− mice exposed to a sublethal Candida albicans infection were better protected against a subsequent lethal dose of these yeasts, whereas monocyte-deficient mice did not show this increased protection, suggesting a form of memory present in the myeloid compartment. Furthermore, in vitro re-exposure of human PBMC to C. albicans induced a significant IL-6 and TNF-α response, even after a resting period of 6 d following primary exposure to C. albicans. Activation of the Dectin-1/RAF proto-oncogene serine/threonine–protein kinase (Raf-1) pathway in PBMCs by β-glucans present in the cell wall of C. albicans proved crucial for inducing trained immunity (2, 3). Concurrently, nonspecific protection induced by bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination also resulted in increased cytokine production in monocytes upon secondary exposure to unrelated pathogens in a T and B cell–independent manner. This process, active for prolonged periods of up to 3 months after vaccination, proved dependent on recognition by nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain–containing protein 2 (NOD2) and signaling via receptor-interacting serine/threonine–protein kinase 2 (Rip2) (4). Further investigation of receptor-specific induction of trained immunity revealed that, depending on the dose, membrane-bound TLR-activation could also induce trained immunity (5). Additionally, it was shown that inhibitions of MAP kinases and histone methylation and acetylation could abolish the trained immunity cytokine profile. These studies highlighted that the pathways to induce trained immunity could be redundant and that the downstream activation is more determinant for the induction of trained immunity. Nevertheless, the Dectin-1/Raf-1 (β-glucans) and NOD2/Rip2 (BCG) could be considered as the best-characterized pathways associated with trained immunity in mammalian monocytes.

Further studies that sought to unravel the underlying mechanisms of trained immunity revealed crucial roles for epigenetic modifications and metabolic reprogramming. Trained immunity, induced by exposure of monocytes to β-glucans or BCG, was associated with long-lived epigenetic modifications in the form of increased trimethylation of histone 3 (H3) lysine 4 and acetylation of H3 lysine 27, both activation markers (2, 6, 7), and with decreased trimethylation of H3 lysine 9, a repressor marker (8). These epigenetic modifications, positioned at promotor sites of immune genes, helped explain the heightened IL-6 and TNF-α response in PBMC after a resting phase of 6 d following primary exposure and appear key to the inflammatory response associated with trained immunity. Epigenetic modifications were also noted at promotor sites of metabolic genes, among which the mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (mTOR) and hexokinase 2 (HK2), introducing metabolic reprogramming as a mechanism underlying trained immunity. Indeed, crucial to the onset of trained immunity appears to be a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation toward glycolysis, orchestrated via the protein kinase B (Akt1)/mTOR/hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF1A) pathway (6, 7). Transcriptome analysis in mice, comparing constitutive expression of trained and untrained monocytes, revealed significantly higher expression of several genes associated with glycolysis, among others, aldehyde dehydrogenase (Aldh2), ADP-dependent glucokinase (Adpgk), and bisphosphoglycerate mutase (Bpgm) (7). Further, activation of the cholesterol synthesis pathway was also noted as an important mechanism underlying trained immunity (9). The metabolic shift resulted in the accumulation of several metabolites, such as fumarate, a substrate of the TCA cycle, and mevalonate, an intermediate in the cholesterol synthesis pathway. Both metabolites could by themselves induce epigenetic modifications and induce cytokine profiles associated with trained immunity (8–10). In addition, blocking metabolic shifts toward glycolysis or glutaminolysis abolished these epigenetic modifications and cytokine profiles, illustrating the strong connections between epigenetic modifications, metabolic reprogramming, and trained immunity.

Little is known about the conservation of aspects of trained immunity in fish, including the aspects described above. Two recent studies in zebrafish have touched upon such aspects, including observations on an increased antiviral state in rag−/− zebrafish associated with increased transcription of innate immune genes (11), and a study describing the lack of effects of pre-exposure to different pathogen-associated molecular patterns on subsequent viral challenges (12). Given the evolutionary position of teleost fish as early vertebrates with a fully developed immune system (13), it is likely that the innate immune cells of fish, such as macrophages, should possess the ability to express specific features of trained immunity. In fact, given that numerous examples exist of a relatively prominent role of innate immunity in fish (14–18), trained immunity could be considered highly relevant to this group of cold-blooded vertebrates. Recently, a review summarized potential benefits and constraints of exploiting trained immunity to our benefit in larval aquaculture (19). We already summarized long-lived effects of β-glucans in fish (20) and hypothesized these might well be explained by features of trained immunity.

In this study, we sought to investigate the hypothesis that trained immunity is conserved in a teleost fish, the common carp. To this end, a well-established in vitro culture of macrophages derived from the head kidney (21), the fish equivalent to mammalian bone marrow, was adapted to study the mechanisms of trained immunity in the common carp. Recent studies have shown trained immunity in monocytes and in bone marrow–derived macrophages (3, 22) and even comparable trained immunity profiles between these two cell populations (23). These findings support the use of a heterogeneous myeloid primary cell culture, such as the head kidney–derived macrophage culture in carp. Given that the existence of a true Dectin-1/Raf-1–like pathway in fish is still elusive (24, 25), but that a NOD2/Rip2–like pathway was proven to exist in zebrafish (26–28), we used a soluble NOD-specific ligand to train carp macrophages. Following a resting period of 6 d, like the experimental setup used to study trained immunity in human PBMC (29), unstimulated trained macrophages showed increased phagocytosis, elevated constitutive expression of several immune- and glycolysis-related genes, as well as a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation toward glycolysis, the latter measured as increased production of lactate. Stimulated trained macrophages typically showed an increased inflammatory response measured as increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and NO. Altogether, our data provide evidence that innate immune cells, such as macrophages, of teleost fish possess the ability to express specific features of trained immunity.

Materials and Methods

Animals

European common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) of the R3 × R8 strain were used, which results from crossing the Hungarian R8 strain and the Polish R3 strain (30). Carp were bred and raised in the Aquatic Research Facility of Carus of Wageningen University at 20–23°C in recirculating UV-treated water and fed pelleted dry food (Carpe-F; Skretting) twice daily. No yeast-derived β-glucans were in the feed ingredients. All experiments were performed with the approval of the animal experiment committee of Wageningen University (Ethical Committee documentation number 2017.W-0034).

Macrophage culture and training stimulus

Carp were euthanized with 0.3 g/L tricaine methanesulfonate (Crescent Research Chemicals) in aquarium water buffered with 0.6 g/L sodium bicarbonate and bled via the caudal vein. Head kidney was isolated and total head kidney leukocytes were separated on a Percoll (GE Healthcare, Thermo Fisher Scientific) density gradient. Macrophages were obtained by culturing head kidney leukocytes in complete NMGFL15 medium at 17.5 × 106 cells per flask (75 cm2; CORN430725U; Corning) for 6 d at 27°C without CO2, as previously described (21). From this point onwards, 6-d cultured, head kidney–derived macrophages will be referred to as “macrophages.”

Culture flasks were placed on ice for 15 min, macrophages were harvested by gentle scraping, washed once with ice-cold PBS, and centrifuged at 450 × g for 10 min. NMGFL15 is formulated to promote proliferation; therefore, subsequent culturing was performed in a different culture medium. Following centrifugation, cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 culture medium with 25 mM HEPES, supplemented with l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin G (100 U/ml), streptomycin sulfate (50 mg/ml) (cRPMI), and cRPMI supplemented with heat-inactivated pooled carp serum (2.5% v/v).

For selection of the optimal concentration of training stimulus, production of ROS and NO were measured according to the protocol described below. As the initial trained immunity experiments on human monocytes found that sublethal dose of C. albicans induced trained immunity, an optimal concentration was defined as a concentration that induces a clear but not maximal innate immune response, measured in this study by NO and ROS production. For NO production, macrophages were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in 96-well culture plates (CORN3596; Corning) and stimulated for 24 h with various concentrations of the NOD-ligand soluble sonicated peptidoglycan from Escherichia coli K12 (PGN-ECndss; InvivoGen) resuspended in endotoxin-free Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) water, hereafter referred to as “PGN.” For ROS production, macrophages were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in white 96-well plates (CLS3912; Corning) and stimulated for 2 h with various concentrations of PGN.

Optimization of the training period

Macrophages were obtained as described above, and the training stimulus (1 μg/ml PGN) was added directly to the culture flask (20 μl 1 mg/ml solution in 20 ml medium) for 2 h at 27°C without CO2. Cells were harvested as described above and washed 3× in ice-cold PBS containing 0.02% (w/v) EDTA (PBS–EDTA) to remove any unbound stimulus. Cells were then seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in 96-well culture plates and either incubated in cRPMI supplemented with heat-inactivated pooled carp serum (1.5% v/v) (cRPMI-1.5) or stimulated for additional 24 h with 1 μg/ml PGN. NO production in the cell culture supernatants was measured as described below.

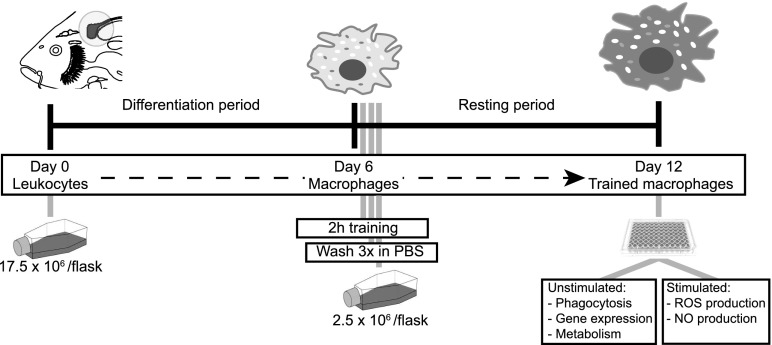

In vitro setup for studying trained immunity

Macrophages were trained by adding PGN directly to the flask at a final concentration 1 μg/ml and incubated for 2 h at 27°C in the absence of CO2. Alternatively, laminarin (tlrl-lam; InvivoGen) at a concentration 50 μg/ml was added (100 μl 10 mg/ml solution in LAL water, in 20 ml medium). As a control, cells were exposed to LAL water in a volume equal to the training stimulus. Cells were then harvested as described above and washed 3× in ice-cold PBS–EDTA to remove any unbound stimulus. The obtained cells will be referred to as “trained macrophages” or “untrained macrophages.” Subsets of trained and untrained macrophages were always analyzed for cell viability with trypan blue exclusion and for reactivity with an NO assay, as described in section Nitrogen radicals production. The remaining cells were seeded at 2.5 × 106 macrophages in 20 ml cRPMI supplemented with heat-inactivated pooled carp serum (2.5% v/v) in 75-cm2 culture flasks (T-75 TC treated, 0030711114; Eppendorf). Cells were incubated at 27°C for additional 6 d (resting period) before harvesting as described above. Subsequently, trained and untrained macrophages were washed once with ice-cold PBS, centrifuged at 450 × g for 10 min, and resuspended in cRPMI. Cell growth, viability, and morphology of trained macrophages after the resting period were comparable to that of untrained macrophages. A schematic overview of the in vitro setup is depicted in Fig. 1.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the in vitro experimental setup to obtain trained macrophages. On day 0, leukocytes are collected from common carp head kidney and cultured for 6 d to allow for differentiation into macrophages (differentiation period). On day 6, macrophages are or are not exposed to the training stimulus for 2 h in the culture flask. Subsequently, cells are harvested and washed three times in ice-cold PBS–EDTA. Cells are transferred to new culture flasks at a fixed density per flask and cultured for another 6 d (resting period). On day 12, trained macrophages are harvested and used for subsequent analysis. Macrophages not exposed at day 6 were treated similarly and served as untrained controls.

ROS production

Production of ROS was determined by a real-time luminol-based ECL assay, as previously described (31). Trained or untrained macrophages were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in white 96-well plates (CLS3912; Corning) and stimulated with one of the following: zymosan (tlrl-zyd, 250 μg/ml, heterologous stimulus; InvivoGen), PGN (10 μg/ml; homologous stimulus), cRPMI (unstimulated control), or PMA (P8139, 1 μg/ml, stimulated control; Sigma-Aldrich). The PGN concentration was increased from 1 to 10 μg/ml to induce a maximal response. Chemiluminescence emission was measured in real time (every 2 min for 120 min) with a FilterMax F5 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader at 27°C and expressed as area under the curve. Fold changes were calculated as the area under the curve of trained- or untrained-stimulated macrophages relative to untrained-unstimulated control (cRPMI).

Nitrogen radicals production

Production of NO was determined as nitrite accumulation using the Griess reaction, as previously described (32). Trained or untrained macrophages were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in 96-well culture plates (CORN3596; Corning) and stimulated with the one of the following: zymosan (250 μg/ml; heterologous stimulus), PGN (10 μg/ml; homologous stimulus), cRPMI (unstimulated control), or LPS (L2880, 50 μg/ml, stimulated control; Sigma-Aldrich). After 15 h at 27°C in the presence of 5% CO2, nitrite production was measured at OD540, using a FilterMax F5 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader and quantified using a sodium nitrite (NaNO2) standard curve. Fold changes were calculated as production of nitrite by trained- or untrained-stimulated macrophages relative to untrained-unstimulated control (cRPMI).

Phagocytosis analysis

Analysis of phagocytic capacity was performed by flow cytometry (FACS) as previously described (33), with minor modifications. Briefly, trained or untrained macrophages (5 × 104 cells per well in 96-well cell culture plates [CORN3596; Corning]) were incubated with fluorescent beads (PSF-001UM Red, MagSphere; cell/bead ratio of 1:10) for 120 min at 27°C in the presence of 5% CO2. Subsequently, macrophages were treated with 0.25% (v/v) trypsin–EDTA (11560626; Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min, resuspended in ice-cold FACS buffer (0.5% [w/v]) BSA [Roche], 0.01% [w/v] NaN3 in PBS), washed twice with ice-cold FACS buffer, and centrifuged at 450 × g for 5 min. Finally, macrophages were resuspended in FACS buffer, and phagocytosis was quantified using a FACSCanto A (BD Biosciences); data were analyzed using FlowJo v10 (BD Biosciences). Phagocytic activity was calculated as the relative proportion of cells that ingested at least one bead. Phagocytic capacity was calculated as the relative proportion of cells that ingested 1, 2, or ≥3 beads. Fold changes were calculated as phagocytic activity or phagocytic capacity of trained-unstimulated macrophages relative to untrained-unstimulated controls.

Gene expression analysis

Gene expression was analyzed by directly lysing 1.5 × 106 trained or untrained macrophages (n = 3 independent cultures) in RLT buffer, immediately after harvest on day 12. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Kit (QIAGEN), including on-column DNase treatment according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and stored at −80°C. Prior to cDNA synthesis, 500 ng total RNA was treated with DNase I, Amplification Grade (InvivoGen), and cDNA was synthesized using random primers (300 ng) and Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis for RT-PCR (InvivoGen). cDNA samples were diluted in nuclease-free water prior to real-time quantitative PCR using the primers listed in Table I. Gene expression was measured by real-time quantitative PCR analysis using ABsolute QPCR, SYBR Green Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett Research), and fluorescence data were analyzed using Rotor-Gene Analysis software version 1.7. The relative gene expression of unstimulated trained versus untrained macrophages was measured immediately after the resting period (day 12). The relative expression ratio was calculated according to the Pfaffl method (34) based on the take-off deviation of the unstimulated trained sample versus each of the unstimulated untrained controls at the same time point and normalized relative to the s11 protein of the 40s subunit as reference gene (Table I).

Table I. Overview of real-time quantitative PCR primers used for in the current study.

| Primer | Forward (5′ – 3′) | Reverse (5′ – 3′) | GenBank Accession Numbera |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40s | 5′-CCGTGGGTGACATCGTTACA-3′ | 5′-TCAGGACATTGAACCTCACTGTCT-3′ | AB012087 |

| il6a | 5′-CAGATAGCGGACGGAGGGGC-3′ | 5′-GCGGGTCTCTTCGTGTCTT-3′ | KC858890 |

| il6b | 5′-GGCGTATGAAGGAGCGAAGA-3′ | 5′-ATCTGACCGATAGAGGAGCG-3′ | KC858889 |

| Tnf-αa1 | 5′-GAGCTTCACGAGGACTAATAGACAGT-3′ | 5′-CTGCGGTAAGGGCAGCAATC-3′ | AJ311800 |

| Tnf-αa2 | 5′-CGGCACGAGGAGAAACCGAGC-3′ | 5′-CATCGTTGTGTCTGTTAGTAAGTTC-3′ | AJ311801 |

| Tnf-αb1 | 5′-GAAGACGATGAAGATGATACCAT-3′ | 5′-AAGTGGTTTTCTCATCCTCAA-3′ | cypCar_00029601, LHQP01065580 |

| Tnf-αb2 | 5′-CTTGGACGAAGCCGATGAAGAC-3′ | 5′-ATCTTGTGACTGGCAAACA-3′ | cypCar_00023012, LHQP01037150 |

| adpgk-1 | 5′-GGCACCACTGAACTTCT-3′ | 5′-GCGTGACCTCTGAAAACAG-3′ | cypCar_00013411, LHQP01005743 |

| adpgk-2 | 5′-GCAAGCCGTGGATATTACA-3′ | 5′-GCGTGAGATGGAAGGA-3′ | cypCar_00024520, LHQP01021894 |

| aldh2.1-1 | 5′-TCCAGAACTTTCCCACAA-3′ | 5′-GCAGATAACCTCACCAGT-3′ | cypCar_00011521, LHQP01009285 |

| aldh2.1-2 | 5′-GATTCCTGCCCCGAGTC-3′ | 5′-TTCTCCACATCCGCCTTC-3′ | cypCar_00046381, LHQP01040595 |

| bpgm-1 | 5′-CGCCACCCCCCATTGAGGAGA-3′ | 5′-GCAGAGATGAGGACTGTTTG-3′ | cypCar_00001430, LHQP01009643 |

| bpgm-2 | 5′-CTAAACGAGCGGCACTAC-3′ | 5′-GGGCAGTTCCTCCTTT-3′ | cypCar_00018360, LHQP01029542 |

cypCar numbers identify open reading frames in the draft carp genome (BioProject: PRJNA73579) that were also confirmed by RNA sequencing; LHQP number refers to the accession number of the associated scaffold.

Lactic acid production

Production of lactic acid was measured using a lactate colorimetric assay (Kit II K627; BioVision), including an optional filtration step (Amicon 10K spin column; Z677108-96EA; Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, macrophages (5 × 105 per well on a 96-well culture plate [CORN3596; Corning]) were incubated in 150 μl cRPMI-1.5 for 24 h at 27°C plus 5% CO2, after which supernatants from triplicate wells (from n = 5 independent cultures) were pooled and filtered. For each pooled sample, a volume of 10 μl was diluted 5× in lactate assay buffer and transferred to 96-well plates. Subsequently, 50 μl reaction mix composed of lactate substrate mix (2 μl), lactate enzyme mix (2 μl), and lactate assay buffer (46 μl), was added to each sample and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. OD was measured at 450 nm and concentration of extracellular lactate was calculated based on a lactic acid calibration curve supplied by the manufacturer. Fold changes were calculated as lactic acid production of trained-unstimulated macrophages relative to untrained- unstimulated controls.

Intracellular fumarate accumulation

Accumulation of intracellular fumarate was measured using a fumarate colorimetric assay (K633; BioVision) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, including an optional filtration step (Amicon 10K spin columns; as above). Briefly, macrophages (5 × 105 per well, 96-well culture plate [CORN3596; Corning]) were incubated in 150 μl cRPMI-1.5 for 24 h at 27°C, after which supernatants were removed, and the macrophages were lysed in 50 μl fumarate assay buffer (n = 4 independent cultures). Cell lysates from duplicate wells were pooled and filtered as mentioned above. For each pooled sample, 25 μl were diluted 2× in fumarate assay buffer and transferred to a 96-wells plate. Subsequently, 100 μl reaction mix composed of fumarate developer mix (8 μl), fumarate enzyme mix (2 μl), and fumarate assay buffer (90 μl) was added to each sample and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. OD was measured at 450 nm, and concentration of intracellular fumarate was calculated based on a fumarate calibration curve supplied by the manufacturer. Fold changes were calculated as fumarate accumulation in trained-unstimulated macrophages relative to untrained-unstimulated controls.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (v23.0), and differences were considered significant if p ≤ 0.05. Data presented as fold change were tested for significance after log transformation. Data used for phagocytosis activity and capacity were first logit-transformed. All data, after testing for Gaussian distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test, were analyzed as paired data to eliminate interference caused by high variability between individual cultures. Optimization of training period was tested with a Friedman test on untransformed NaNO2 values (micromolars), followed by a Dunn post hoc test. Comparison between untrained and trained macrophages of ROS and NO production and comparison of constitutive gene expression were performed with a linear mixed model, followed by a least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test. Comparison of phagocytic activity and phagocytic capacity was performed with a paired samples t test. Comparison of lactate production and fumarate accumulation was performed with an independent samples t test. For multiple comparisons of the stimulatory effect of PGN versus laminarin, a multivariate analysis followed by LSD post hoc test was used.

Results

Soluble peptidoglycan can be used as primary stimulus to induce trained immunity in carp macrophages

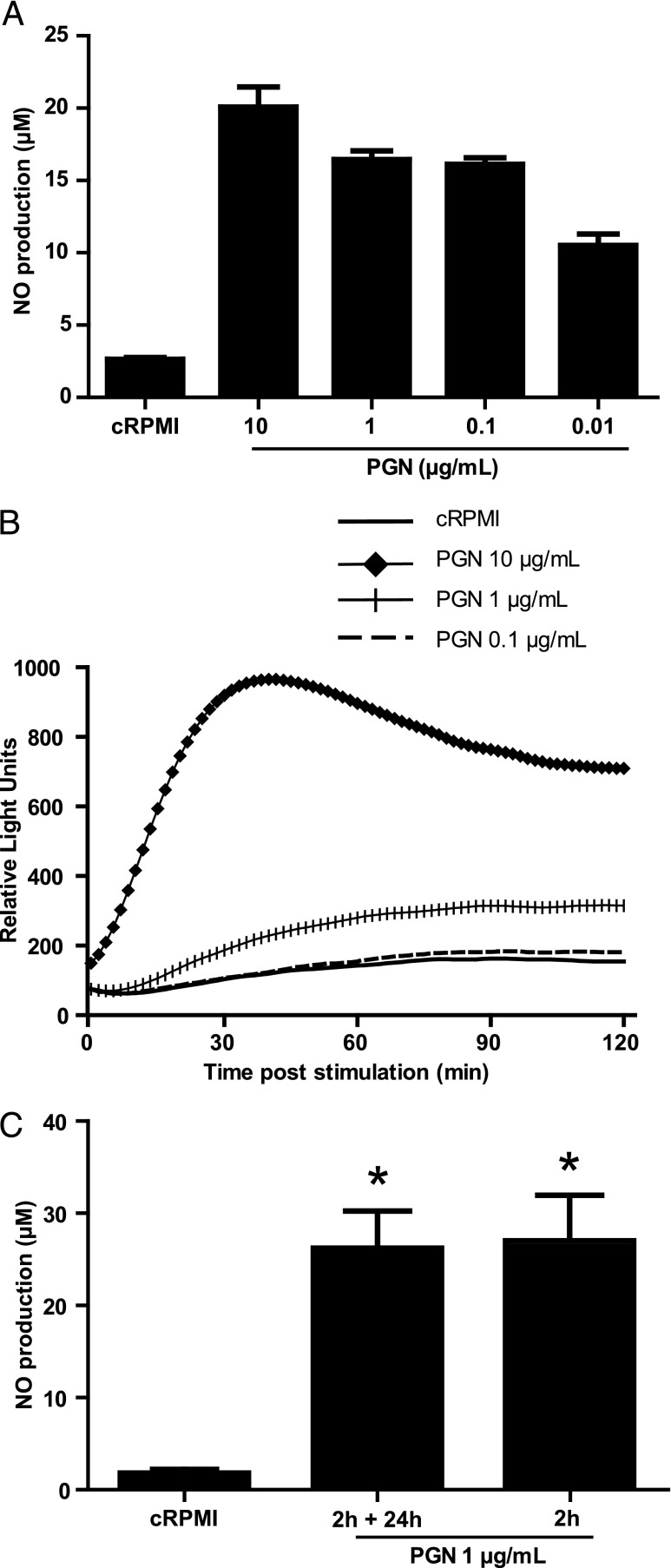

Given that induction of trained immunity in human and mouse monocytes could be achieved via stimulation with a NOD2 ligand, we used the PGN as a ligand to stimulate carp macrophages. To determine the optimal concentration, on day 6 of culture (Fig. 1), macrophages were stimulated with various concentrations of PGN. Induction of NO was measured in cell supernatants after 24 h (Fig. 2A), whereas ROS production was measured in real time for 2 h and expressed as relative light units (Fig. 2B). A dose-dependent response was observed for both assays. The concentration of 10 μg/ml induced a maximal response, judging from both cumulative NO production over 24 h and immediate oxidative burst measured in the 2 h following stimulation. The concentration of 0.1 μg/ml induced a substantial but not maximal NO production and almost no oxidative burst. As the concentration of 1 μg/ml induced a substantial but not maximal response for both cumulative NO production over 24 h and oxidative burst immediately after stimulation, we chose this concentration as optimal dose for training. Subsequent experiments were performed with a concentration of 1 μg/ml PGN as primary stimulus to induce trained immunity because this dose stimulated a robust but not maximal response.

FIGURE 2.

PGN induces a dose-dependent response in carp macrophages. After the differentiation period (day 6), carp macrophages were harvested, seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 105 cells per well) and stimulated with cRPMI or with the indicated concentration of PGN. (A) Dose-dependent analysis of PGN on NO production. NO production was measured as NaNO2 in the supernatant 24 h poststimulation. Bars indicate mean + SD of triplicate measurements from one representative experiment out of (n = 3) performed independently. (B) Dose-dependent analysis of PGN on ROS production. Real-time ROS production was measured immediately following stimulation. Lines indicate acquisition of light emission in one representative experiment out of (n = 3) performed independently. (C) Time course analysis of PGN on NO production. Cells were stimulated for 2 h by directly adding PGN or RPMI to the flask. Cells were then seeded and either incubated in cRPMI-1.5 or stimulated for additional 24 h with PGN (2 h plus 24 h). NO production was measured as NaNO2 in the supernatant 24 h postseeding. Bars indicate mean + SEM of (n = 5) independently performed experiments. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference (p < 0.05) relative to the cRPMI control as assessed with a Friedman test, followed by a Dunn post hoc test (C).

After having determined the optimal concentration of the training stimulus, we next investigated the duration of the primary stimulation required to train macrophages. Previous studies reported that exposure for 24 h to the training stimulus followed by a 6-d resting period, was required for optimal training of human or mouse macrophages (29). In our case we tested whether 24 h or an even shorter period would be suitable to train carp macrophages. When carp macrophages were stimulated for a total of 26 h (2 h plus 24 h) or for only 2 h with PGN, in all cases a significantly higher NO production was measured relative to the unstimulated untrained cells (cRPMI) with no difference between the two durations of treatment (Fig. 2C). This suggested that a stimulation period as short as 2 h was sufficient to stimulate carp macrophages. Altogether, soluble PGN induced a dose-dependent production of NO and ROS in carp macrophages, and a 2 h primary stimulation with 1 μg/ml PGN followed by a 6-d resting period was selected to further investigate trained immunity in carp macrophages.

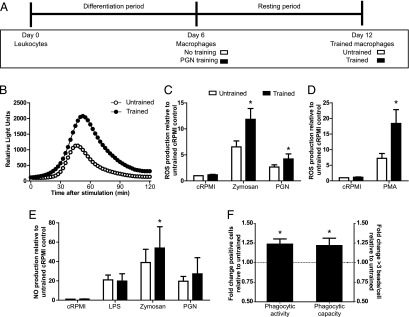

Trained macrophages show heightened innate immune responses

Next, we investigated whether the response of trained macrophages differed from that of untrained macrophages upon restimulation with either the training stimulus (PGN, homologous) or with a different stimulus (zymosan, heterologous) (for experimental setup see Figs. 1, 3A). Stimulation with zymosan resulted in comparable kinetics of ROS production between trained and untrained macrophages, but the production of ROS was significantly higher in trained macrophages (Fig. 3B). Constitutive ROS production was not different between untrained and trained macrophages (Fig. 3C, cRPMI), whereas it was significantly higher in trained macrophages exposed to zymosan or PGN (Fig. 3C). Similarly, exposure to the receptor-independent stimulus PMA resulted in a significantly higher production of ROS in trained as compared with untrained macrophages (Fig. 3D). With respect to production of NO, constitutive production was not different between untrained and trained macrophages (Fig. 3E, cRPMI). Exposure to zymosan but not to LPS or PGN resulted in a significantly higher NO production in trained as compared with untrained macrophages (Fig. 3E). Phagocytic activity and phagocytic capacity of macrophages was compared between unstimulated trained and unstimulated untrained macrophages. A significantly higher number of cells with internalized beads, as well as higher number of beads per cell, was observed for trained as compared with untrained macrophages, indicative of a heightened phagocytic activity as well as phagocytic capacity of trained macrophages (Fig. 3F). The increase in phagocytic activity and capacity may not necessary result in downstream proinflammatory responses. Nevertheless, the increased ROS production observed after stimulation with zymosan could be considered reflective of both phagocytosis and increased proinflammatory responses because our analysis of zymosan-induced ROS production is phagocytosis based (35). Altogether, measurement of ROS and NO production, as well as measurement of phagocytosis, showed heightened innate immune functions of trained carp macrophages.

FIGURE 3.

Trained carp macrophages show increased innate immune functions. (A) Experimental in vitro setup. Head kidney leukocytes were differentiated into macrophages for 6 d. On day 6, macrophages were stimulated with 1 μg/ml PGN (trained) or vehicle control (untrained), followed by a resting period of 6 d. On day 12, trained or untrained macrophages were harvested and used for subsequent analyses. (B–D) Trained or untrained macrophages were seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 105 cells per well) and stimulated with cRPMI, zymosan (250 μg/ml), PGN (10 μg/ml), or PMA (1 μg/ml). The concentration of PGN was increased to 10 μg/ml to ascertain the induction of a maximal response. (B) Real-time ROS production was measured immediately following stimulation. Lines indicate acquisition of light emission measured in one representative experiment out of (n = 11) independently performed experiments. (C and D) Total ROS production relative to unstimulated, untrained macrophages (cRPMI); bars indicate mean + SEM of (n = 11) experiments performed independently. (E) Trained or untrained macrophages were seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 105 cells per well) and stimulated with cRPMI, LPS (50 μg/ml), zymosan (250 μg/ml), or PGN (10 μg/ml). The concentration of PGN was increased to 10 μg/ml to ascertain the induction of a maximal response. NO production was measured as NaNO2 in the supernatant 15 h poststimulation. NO production is expressed relative to unstimulated untrained macrophages (cRPMI); bars indicate mean + SEM of (n = 7) experiments performed independently. (F) Unstimulated trained or unstimulated untrained macrophages were analyzed for their phagocytic activity (left, y-axis) and phagocytic capacity (right, y-axis) after 2 h incubation with fluorescent beads (1 cell/10 beads). Fold change is expressed relative to the corresponding untrained cells; bars indicate mean + SEM of (n = 6) experiments performed independently. For phagocytic capacity, only the proportion of cells phagocytosing ≥3 beads is shown. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference (p < 0.05) relative to the corresponding untrained sample as assessed by a linear mixed model one-way ANOVA, followed by an LSD post hoc test (C–E) or paired samples t test (F).

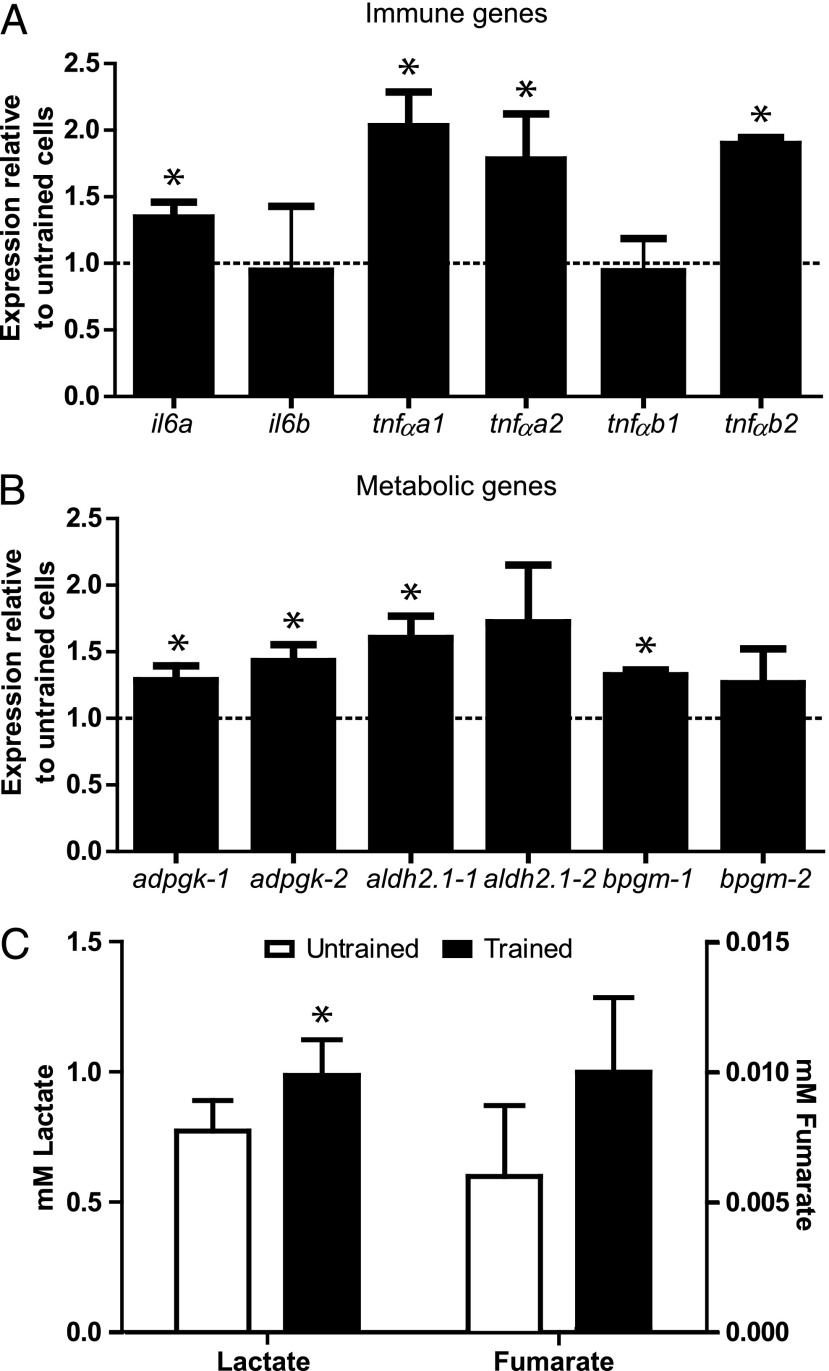

Trained macrophages show immune and metabolic reprogramming

Studies on trained human PBMC revealed a differential expression of IL-6 and TNF-α in response to microbial stimulation, which introduced metabolic reprogramming toward glycolysis as an important mechanism underlying trained immunity. Sensitive, validated cytokine ELISAs to detect fish cytokines are not commercially available, and in-house development has been relatively unsuccessful (36), we therefore measured cytokine responses as gene expression. After having assessed that trained macrophages display heightened responses to stimulation (Fig. 3), we analyzed whether trained macrophages would display differences in constitutive gene expression of inflammatory or metabolic genes (Table I). Trained macrophages showed moderate but significantly increased expression of inflammatory genes, including il-6 and tnf-α, each present in multiple copies (paralogs) in carp (Fig. 4A). A trend toward increased il-1β expression in trained macrophages was also observed (p value = 0.06), whereas il-10 and inosb expression remained unchanged (data not shown). With respect to the expression of metabolic genes, trained macrophages showed significantly increased expression of specific paralogs of adpgk, aldh2.1, and bpgm (Fig. 4B), suggestive of activation of the glycolysis pathway compared with untrained cells. Further evidence of metabolic reprogramming in unstimulated trained macrophages toward glycolysis was obtained upon measurement of extracellular lactate concentrations and intracellular accumulation of the metabolite fumarate. Trained macrophages showed significantly higher lactate values and a trend (p value = 0.077) toward higher accumulation of fumarate as compared with untrained cells (Fig. 4C). To validate epigenetic reprogramming and elucidate kinetics of reprogramming, further analysis would be required. Nevertheless, the increased expression of both immune and metabolic genes in unstimulated but trained macrophages after a 6-d resting period suggests immunologic and metabolic reprogramming.

FIGURE 4.

Trained carp macrophages show immune and metabolic reprogramming. Trained or untrained macrophages were obtained as described in Fig. 3. (A and B) Gene expression of il6 and tnf-α paralogs (A) or selected metabolic genes and their paralogs (B) in unstimulated trained macrophages relative to unstimulated untrained controls; bars indicate mean + SEM of (n = 3) experiments performed independently. (C) Lactate and Fumarate accumulation. Unstimulated trained or unstimulated untrained macrophages were seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 105 cells per well), and accumulation of extracellular lactate and intracellular fumarate was measured 24 h later; bars indicate mean + SEM of (n = 5, lactate) and (n = 4, fumarate) experiments performed independently. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference (p < 0.05) relative to the corresponding untrained sample as assessed by a linear mixed model one-way ANOVA, followed by an LSD post hoc test (A and B) or independent samples test (C).

Soluble β-glucan laminarin is a potent training stimulus

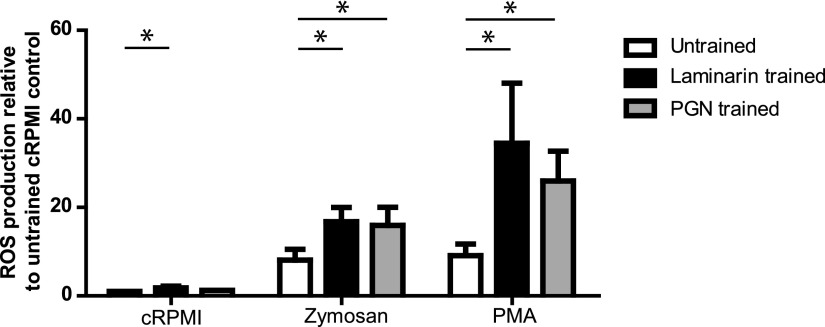

In human PBMC, stimulation with BCG or β-glucans could induce trained immunity. We therefore investigated whether, besides PGN, the soluble β-glucan laminarin could also induce trained immunity in carp macrophages (Fig. 5). Training with laminarin but not PGN led to a marginal but significant increase in constitutive production of ROS as compared with untrained cells (cRPMI). Training with laminarin and subsequent exposure to zymosan or PMA resulted in significantly heightened production of ROS, comparable to macrophages trained with PGN. Altogether, measurement of ROS production proved particularly informative to identify ligands able to train carp macrophages and revealed that not only NOD-ligands but also β-glucans can serve as suitable training stimuli of fish macrophages.

FIGURE 5.

Exposure to laminarin leads to trained immunity in carp macrophages. On day 6, macrophages were trained with laminarin (20 μg/ml) or PGN (1 μg/ml) or left untrained (vehicle control), followed by a resting period of 6 d. On day 12, trained or untrained macrophages were harvested and seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 105 cells per well). ROS production was measured immediately following stimulation with either cRPMI, zymosan (250 μg/ml), or PMA (1 μg/ml) and expressed relative to the unstimulated untrained control (cRPMI); bars indicate mean + SEM of (n = 6) experiments performed independently. Asterisk (*) indicates significant differences (p < 0.05) relative to the corresponding untrained sample as assessed by a multivariate analysis, followed by LSD post hoc test.

Discussion

In the current study, we adapted a well-described in vitro culture system of head kidney–derived macrophages to investigate conservation of trained immunity in teleost fish. A 2-h in vitro exposure to a soluble NOD-specific ligand or to soluble β-(1,3/1,6) glucan resulted in carp macrophages that displayed typical features of trained immunity for a period of at least 6 d. The use of soluble ligands allowed for thorough washing and removal of traces of ligands, a procedure we considered crucially important to exclude continuous restimulation of macrophages. Typical features of trained macrophages of carp included heightened phagocytosis and inflammatory responses following stimulation with (homologous or heterologous) microbial stimuli. The inflammatory profile displayed heightened production of ROS or nitrogen species, increased constitutive gene expression of selected immune and metabolic genes, as well as an increased constitutive lactate production, illustrative of a metabolic shift. Measurement of the production of ROS proved particularly informative to identify ligands able to train carp macrophages.

The present study provides in vitro evidence for conservation of several key features of trained immunity in macrophages of carp, a representative teleost fish but provides no in vivo evidence for trained immunity. However, vaccination with BCG, a known stimulant of trained immunity in mice/human monocytes, has already been shown to provide cross-protection against Mycobacterium species infections in several fish species (37–39), including zebrafish (40), a well-known animal model closely related to carp. The nonspecific protection provided by BCG injection also suggests that in fish in vivo evidence for trained immunity already exists. In addition, zebrafish i.p.-injected with β-glucans and subsequently challenged with spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) either showed a significant but minor increase in survival at seven but not 35 d posttreatment (12) or a clear increase in survival at 14 d posttreatment (41). Thus, relatively long-lived effects of immune stimulants not specifically associated with antiviral immunity provide at least circumstantial in vivo evidence for trained immunity in zebrafish. All of the above-described studies clearly indicate the complexity of in vivo experiments, not unique to experiments in fish, in which it is not easy to exclude the involvement of adaptive immunity and the possibility of continuous stimulation as opposed to a single training event, a clear advantage of our in vitro system based on soluble ligands and rigorous washing steps.

Zebrafish could prove especially informative for in vivo studies on trained immunity owing to the availability of rag−/− strains. Increased survival of rag−/− zebrafish upon lethal challenge with Edwardsiella ictaluri 8 wk postexposure to an attenuated nonvirulent strain of this bacterium (42) could be considered in vivo evidence of trained immunity, although persistence of attenuated bacteria and absence of nonspecific cross-protection against another bacterium, Yersinia ruckeri, could not fully exclude the involvement of other protective mechanisms. Only recently, rag−/− zebrafish were shown to exhibit a constitutively heightened innate immune activity, characterized by an increased antiviral state and associated resistance to a viral challenge with SVCV (11). In the latter study, NK cell markers, such as cd8 and nklysin, were also constitutively higher expressed in rag−/− than in wild-type zebrafish. This observation is of particular interest in view of the BCG-induced (43) and virus-induced (44, 45) memory-like NK cells, recently highlighted as cell types associated with trained immunity in mammals. Further study could thus be relevant for NK-like cells in relation to virus-induced trained immunity in the rag−/− zebrafish model and to explore genes associated with an antiviral state as novel markers for trained immunity.

Teleost fish (e.g., carp, zebrafish) are poikilotherms, which allows for manipulation of temperature and, thus, allows for studies on temperature-associated effects on trained immunity in vitro and in vivo. Adaptive immunity, more than innate immunity, is considered sensitive to temperature change, reflected by reduced IgM serum concentrations and suppression of T cell responses at lower temperatures (46, 47). Thus, the use of poikilothermic animals opens the possibility to knockdown adaptive immune responses in animals for which rag−/− strains are not available and to study, in vivo, aspects of trained immunity, including the duration of cross-protection against a secondary infection in a T and B lymphocyte–independent manner. Temperature-mediated knockdown of adaptive immune responses in teleost fish might thus allow for unraveling mechanisms underlying long-lived protection likely mediated by innate immune cells that also remain active at lower temperatures.

One of the determining and underlying mechanisms of trained immunity is based on long-lived epigenetic modifications that persist even after removal of the training stimulus [as reviewed by (48)]. For example, histone modifications, such as trimethylation of H3K4 and mono acetylation of H3K27, have been associated with β-glucan–induced trained immunity of human PBMC. These epigenetic changes were strongly correlated with differential gene expression induced by β-glucan training in monocytes (2). In the same study, comparable epigenetic changes were observed in peritoneal macrophages isolated from C. albicans–infected mice, linking the observed in vitro histone modifications to an in vivo model of trained immunity. The onset of these epigenetic modifications is strongly connected to metabolic reprogramming and dependent on specific metabolites, such as fumarate and mevalonate (8, 10). In our in vitro model, we investigated epigenetic modifications in trained macrophages by measuring (increased) constitutive expression of several immune- and glycolysis-related genes and a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation toward glycolysis. To study in more detail epigenetic modifications underlying trained immunity in fish, future studies could build on, for example, a recent chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing study performed on SVCV-infected zebrafish (49). Another interesting aspect of trained immunity that could be studied in vivo, at least in oviparous fish, is transgenerational epigenetic reprogramming. Because primordial F2 germ cells are not present upon exposure of F0 individuals to potential training stimuli, one less generation is needed to prove transgenerational effects in oviparous fish (50). In conclusion, the constitutive antiviral state of rag−/− zebrafish, the cold-blooded nature of teleost fish allowing natural knockdown of the adaptive immune system, and the suitability of oviparous fish for transgenerational experiments all provide arguments in favor of studying conserved but also unique aspects of trained immunity in teleost fish.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Raphael Barbetta de Jesus and Fabiana Pilarski for discussions on the potential impact of trained immunity on aquaculture practice and Cassandra van Doorn for contribution to the initial cell culture optimization.

This work was supported by and research leading to this review was funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research and São Paulo Research Foundation, Brazil (FAPESP) as part of the Joint Research Projects BioBased Economy Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research–FAPESP Programme (Project 729.004.002).

- BCG

- bacillus Calmette-Guérin

- cRPMI

- RPMI 1640 culture medium with 25 mM HEPES, supplemented with l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin G (100 U/ml), streptomycin sulfate (50 mg/ml)

- cRPMI-1.5

- cRPMI supplemented with heat-inactivated pooled carp serum (1.5% v/v)

- H3

- histone 3

- LAL

- Limulus amebocyte lysate

- LSD

- least significant difference

- NOD2

- nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain–containing protein 2

- PBS–EDTA

- ice-cold PBS containing 0.02% (w/v) EDTA

- PGN

- soluble sonicated peptidoglycan from Escherichia coli K12 resuspended in endotoxin-free LAL water

- Raf-1

- RAF proto-oncogene serine/threonine–protein kinase

- Rip2

- receptor-interacting serine/threonine–protein kinase 2

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- SVCV

- spring viremia of carp virus.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Netea M. G., Quintin J., van der Meer J. W. 2011. Trained immunity: a memory for innate host defense. Cell Host Microbe 9: 355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quintin J., Saeed S., Martens J. H. A., Giamarellos-Bourboulis E. J., Ifrim D. C., Logie C., Jacobs L., Jansen T., Kullberg B. J., Wijmenga C., et al. 2012. Candida albicans infection affords protection against reinfection via functional reprogramming of monocytes. Cell Host Microbe 12: 223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ifrim D. C., Joosten L. A. B., Kullberg B. J., Jacobs L., Jansen T., Williams D. L., Gow N. A. R., van der Meer J. W. M., Netea M. G., Quintin J. 2013. Candida albicans primes TLR cytokine responses through a Dectin-1/Raf-1-mediated pathway. J. Immunol. 190: 4129–4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleinnijenhuis J., Quintin J., Preijers F., Joosten L. A., Ifrim D. C., Saeed S., Jacobs C., van Loenhout J., de Jong D., Stunnenberg H. G., et al. 2012. Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 17537–17542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ifrim D. C., Quintin J., Joosten L. A. B., Jacobs C., Jansen T., Jacobs L., Gow N. A. R., Williams D. L., van der Meer J. W. M., Netea M. G. 2014. Trained immunity or tolerance: opposing functional programs induced in human monocytes after engagement of various pattern recognition receptors. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 21: 534–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saeed S., Quintin J., Kerstens H. H., Rao N. A., Aghajanirefah A., Matarese F., Cheng S. C., Ratter J., Berentsen K., van der Ent M. A., et al. 2014. Epigenetic programming of monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and trained innate immunity. Science 345: 1251086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng S. C., Quintin J., Cramer R. A., Shepardson K. M., Saeed S., Kumar V., Giamarellos-Bourboulis E. J., Martens J. H. A., Rao N. A., Aghajanirefah A., et al. 2014. mTOR- and HIF-1α-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. [Published erratum appears in 2014 Science 346: aaa1503.] Science 345: 1250684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arts R. J. W., Carvalho A., La Rocca C., Palma C., Rodrigues F., Silvestre R., Kleinnijenhuis J., Lachmandas E., Gonçalves L. G., Belinha A., et al. 2016. Immunometabolic pathways in BCG-induced trained immunity. Cell Rep. 17: 2562–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bekkering S., Arts R. J. W., Novakovic B., Kourtzelis I., van der Heijden C. D. C. C., Li Y., Popa C. D., Ter Horst R., van Tuijl J., Netea-Maier R. T., et al. 2018. Metabolic induction of trained immunity through the mevalonate pathway. Cell 172: 135–146.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arts R. J., Novakovic B., Ter Horst R., Carvalho A., Bekkering S., Lachmandas E., Rodrigues F., Silvestre R., Cheng S. C., Wang S. Y., et al. 2016. Glutaminolysis and fumarate accumulation integrate immunometabolic and epigenetic programs in trained immunity. Cell Metab. 24: 807–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García-Valtanen P., Martínez-López A., López-Muñoz A., Bello-Perez M., Medina-Gali R. M., Ortega-Villaizán M. D., Varela M., Figueras A., Mulero V., Novoa B., et al. 2017. Zebra fish lacking adaptive immunity acquire an antiviral alert state characterized by upregulated gene expression of apoptosis, multigene families, and interferon-related genes. Front. Immunol. 8: 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Álvarez-Rodríguez M., Pereiro P., Reyes-López F. E., Tort L., Figueras A., Novoa B. 2018. Analysis of the long-lived responses induced by immunostimulants and their effects on a viral infection in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Front. Immunol. 9: 1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magor B. G., Magor K. E. 2001. Evolution of effectors and receptors of innate immunity. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 25: 651–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rebl A., Goldammer T. 2018. Under control: the innate immunity of fish from the inhibitors’ perspective. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 77: 328–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tokunaga Y., Shirouzu M., Sugahara R., Yoshiura Y., Kiryu I., Ototake M., Nagasawa T., Somamoto T., Nakao M. 2017. Comprehensive validation of T- and B-cell deficiency in rag1-null zebrafish: implication for the robust innate defense mechanisms of teleosts. Sci. Rep. 7: 7536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aoki T., Takano T., Santos M. D., Kondo H., Hirono I. 2008. Molecular innate immunity in teleost fish: review and future perspectives. In Fisheries for Global Welfare and Environment, Memorial Book of the 5th World Fisheries Congress. Tsukamoto K., Kawamura T., eds. Terrapub, Tokyo, Japan, p. 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnadóttir B. 2006. Innate immunity of fish (overview). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 20: 137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wcisel D. J., Yoder J. A. 2016. The confounding complexity of innate immune receptors within and between teleost species. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 53: 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Z., Chi H., Dalmo R. A. 2019. Trained innate immunity of fish is a viable approach in larval aquaculture. Front. Immunol. 10: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petit J., Wiegertjes G. F. 2016. Long-lived effects of administering β-glucans: indications for trained immunity in fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 64: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joerink M., Ribeiro C. M., Stet R. J., Hermsen T., Savelkoul H. F., Wiegertjes G. F. 2006. Head kidney-derived macrophages of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) show plasticity and functional polarization upon differential stimulation. J. Immunol. 177: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walachowski S., Tabouret G., Fabre M., Foucras G. 2017. Molecular analysis of a short-term model of β-glucans-trained immunity highlights the accessory contribution of GM-CSF in priming mouse macrophages response. Front. Immunol. 8: 1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saz-Leal P., Del Fresno C., Brandi P., Martínez-Cano S., Dungan O. M., Chisholm J. D., Kerr W. G., Sancho D. 2018. Targeting SHIP-1 in myeloid cells enhances trained immunity and boosts response to infection. Cell Rep. 25: 1118–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zelensky A. N., Gready J. E. 2004. C-type lectin-like domains in Fugu rubripes. BMC Genomics 5: 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petit J., Bailey E. C., Wheeler R. T., de Oliveira C. A. F., Forlenza M., Wiegertjes G. F. 2019. Studies into β-glucan recognition in fish suggests a key role for the C-type lectin pathway. Front. Immunol. 10: 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maharana J., Sahoo B. R., Bej A., Jena I., Parida A., Sahoo J. R., Dehury B., Patra M. C., Martha S. R., Balabantray S., et al. 2015. Structural models of zebrafish (Danio rerio) NOD1 and NOD2 NACHT domains suggest differential ATP binding orientations: insights from computational modeling, docking and molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS One 10: e0121415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oehlers S. H., Flores M. V., Hall C. J., Swift S., Crosier K. E., Crosier P. S. 2011. The inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) susceptibility genes NOD1 and NOD2 have conserved anti-bacterial roles in zebrafish. Dis. Model. Mech. 4: 832–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou P. F., Chang M. X., Li Y., Xue N. N., Li J. H., Chen S. N., Nie P. 2016. NOD2 in zebrafish functions in antibacterial and also antiviral responses via NF-κB, and also MDA5, RIG-I and MAVS. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 55: 173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bekkering S., Blok B. A., Joosten L. A., Riksen N. P., van Crevel R., Netea M. G. 2016. In vitro experimental model of trained innate immunity in human primary monocytes. [Published erratum appears in 2017 Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 24: e00096–e00117.] Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 23: 926–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irnazarow I. 1995. Genetic variability of Polish and Hungarian carp lines. Aquaculture 129: 215. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piazzon M. C., Savelkoul H. S., Pietretti D., Wiegertjes G. F., Forlenza M. 2015. Carp Il10 has anti-inflammatory activities on phagocytes, promotes proliferation of memory T cells, and regulates B cell differentiation and antibody secretion. J. Immunol. 194: 187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saeij J. P., Van Muiswinkel W. B., Groeneveld A., Wiegertjes G. F. 2002. Immune modulation by fish kinetoplastid parasites: a role for nitric oxide. Parasitology 124: 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J., Barreda D. R., Zhang Y. A., Boshra H., Gelman A. E., Lapatra S., Tort L., Sunyer J. O. 2006. B lymphocytes from early vertebrates have potent phagocytic and microbicidal abilities. Nat. Immunol. 7: 1116–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfaffl M. W. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scharsack J. P., Koch K., Hammerschmidt K. 2007. Who is in control of the stickleback immune system: interactions between Schistocephalus solidus and its specific vertebrate host. Proc. Biol. Sci. 274: 3151–3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dixon B., Barreda D. R., Sunyer J. O. 2018. Perspective on the development and validation of ab reagents to fish immune proteins for the correct assessment of immune function. Front. Immunol. 9: 2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kato G., Kondo H., Aoki T., Hirono I. 2010. BCG vaccine confers adaptive immunity against Mycobacterium sp. infection in fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 34: 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kato G., Kato K., Saito K., Pe Y., Kondo H., Aoki T., Hirono I. 2011. Vaccine efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis BCG against Mycobacterium sp. infection in amberjack Seriola dumerili. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 30: 467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kato G., Kondo H., Aoki T., Hirono I. 2012. Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine induces non-specific immune responses in Japanese flounder against Nocardia seriolae. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 33: 243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oksanen K. E., Halfpenny N. J., Sherwood E., Harjula S. K., Hammarén M. M., Ahava M. J., Pajula E. T., Lahtinen M. J., Parikka M., Rämet M. 2013. An adult zebrafish model for preclinical tuberculosis vaccine development. Vaccine 31: 5202–5209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.M Medina-Gali R., Ortega-Villaizan M. D. M., Mercado L., Novoa B., Coll J., Perez L. 2018. Beta-glucan enhances the response to SVCV infection in zebrafish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 84: 307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hohn C., Petrie-Hanson L. 2012. Rag1-/- mutant zebrafish demonstrate specific protection following bacterial re-exposure. PLoS One 7: e44451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kleinnijenhuis J., Quintin J., Preijers F., Joosten L. A., Jacobs C., Xavier R. J., van der Meer J. W., van Crevel R., Netea M. G. 2014. BCG-induced trained immunity in NK cells: role for non-specific protection to infection. Clin. Immunol. 155: 213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun J. C., Beilke J. N., Lanier L. L. 2009. Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. [Published erratum appears in 2009 Nature 457: 1168.] Nature 457: 557–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlums H., Cichocki F., Tesi B., Theorell J., Beziat V., Holmes T. D., Han H., Chiang S. C., Foley B., Mattsson K., et al. 2015. Cytomegalovirus infection drives adaptive epigenetic diversification of NK cells with altered signaling and effector function. Immunity 42: 443–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magnadottir B. 2010. Immunological control of fish diseases. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY) 12: 361–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bowden T. J. 2008. Modulation of the immune system of fish by their environment. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 25: 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dominguez-Andres J., Netea M. G. 2019. Long-term reprogramming of the innate immune system. J. Leukoc. Biol. 105: 329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Medina-Gali R., Belló-Pérez M., Martínez-López A., Falcó A., Ortega-Villaizan M. M., Encinar J. A., Novoa B., Coll J., Perez L. 2018. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and high throughput sequencing of SVCV-infected zebrafish reveals novel epigenetic histone methylation patterns involved in antiviral immune response. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 82: 514–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Best C., Ikert H., Kostyniuk D. J., Craig P. M., Navarro-Martin L., Marandel L., Mennigen J. A. 2018. Epigenetics in teleost fish: from molecular mechanisms to physiological phenotypes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 224: 210–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]