Short abstract

Purpose

There appears to be an association between poor oral hygiene and increased risk of aspiration pneumonia – a leading cause of mortality post-stroke. We aim to synthesise what is known about oral care after stroke, identify knowledge gaps and outline priorities for research that will provide evidence to inform best practice.

Methods

A narrative review from a multidisciplinary perspective, drawing on evidence from systematic reviews, literature, expert and lay opinion to scrutinise current practice in oral care after a stroke and seek consensus on research priorities.

Findings: Oral care tends to be of poor quality and delegated to the least qualified members of the caring team. Nursing staff often work in a pressured environment where other aspects of clinical care take priority. Guidelines that exist are based on weak evidence and lack detail about how best to provide oral care.

Discussion

Oral health after a stroke is important from a social as well as physical health perspective, yet tends to be neglected. Multidisciplinary research is needed to improve understanding of the complexities associated with delivering good oral care for stroke patients. Also to provide the evidence for practice that will improve wellbeing and may reduce risk of aspiration pneumonia and other serious sequelae.

Conclusion

Although there is evidence of an association, there is only weak evidence about whether improving oral care reduces risk of pneumonia or mortality after a stroke. Clinically relevant, feasible, cost-effective, evidence-based oral care interventions to improve patient outcomes in stroke care are urgently needed.

Keywords: Stroke, oral health, oral hygiene, oral cavity, mouth, dental, pneumonia, quality of life, tooth-brushing

Introduction

Poor oral care after a stroke can have serious physical, psychological and social consequences and adversely affect quality of life.1–3

Aspiration pneumonia causes the highest attributable mortality of all medical complications following stroke and its prevention is therefore of paramount importance.4,5 There is a growing body of evidence to indicate that poor oral hygiene increases the risk of pneumonia.6,7 It would be rational to expect good oral hygiene and plaque control in the early stages after a stroke to reduce risk, but evidence for this is weak.8–10

Dysphagia and loss of sensation affects up to 78% of patients who have recently had a stroke and can cause stasis of saliva and food in the oral cavity.11–13 Reduced tongue pressure and altered lateral movements result in increased risk of aspiration as well as causing food to pool in the sulci of the oral cavity resulting in denture problems and stomatitis.14–16 There also appears to be a higher than normal pathogenic bacterial and yeast count in the oral cavity in the acute phase of stroke.17,18 This combination increases the risk of aspiration pneumonia.9,19–24 Approximately 10,000 microbial phylotypes have been identified in the human oral microflora.25 There is a huge diversity of bacterial organisms in the oral cavity of stroke patients. The balance between organisms may be as important for containing risk of aspiration pneumonia as the presence or the absence of any particular bacteria in the oral cavity.26

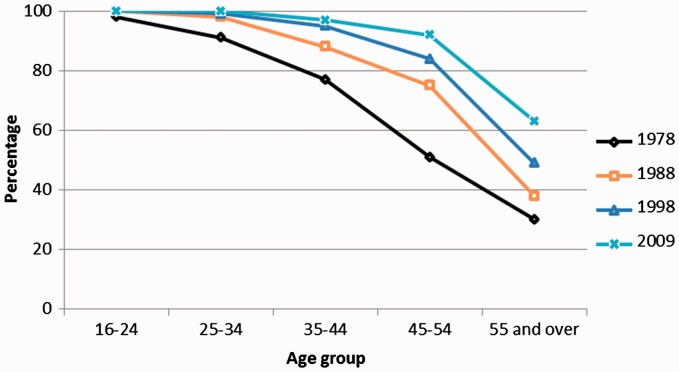

Whilst stroke can affect people of all ages, the average is 71 years.27 In many low and middle-income countries, the incidence of stroke is increasing but even in many European countries where it is decreasing, the size of the problem, based on the actual number of new strokes is rising because of the ageing population.27 Figure 1 shows the improving pattern of dentition between 1978 and 2009 in England. Although considerably more people are surviving into old age with some natural teeth, very few have excellent oral health. Most have periodontal disease, a sizeable number of restorations (fillings and implants) and need help to maintain their oral health.28,29

Figure 1.

Trends in percentage of adults with 21 or more natural teeth by age, England 1978–2009.

Source: Oral health and function – a report from the adult dental health survey 2009. NHS Information centre for health and social care. Copyright© 2016, Re-used with the permission of the Health and Social Care Information Centre, also known as NHS Digital. All rights reserved.

The cost of dental care in the European Union is expected to rise from €54 billion in 2000 to €93 billion in 2020.30 A significant proportion of this relates to the provision of oral care for the growing number of dependent older people – including those who have had a stroke.31,32

People who have a stroke tend to have worse oral health than the rest of the population but a cause and effect relationship cannot be assumed and the relative importance of specific risk factors such as smoking, poor nutrition and diabetes that stroke and poor oral health have in common is unclear.33 A scoping review of oral care post stroke found that stroke survivors aged 50 to 70 years have fewer natural teeth and are more likely to wear dentures than a control group of a similar age who had not had a stroke.19,34 A systematic review found that patients with stroke had a poorer clinical oral health status across a range of parameters (tooth loss, dental caries experience and periodontal status).20 Other reviews have demonstrated an association between periodontal disease and stroke.33,35

What is to follow

In this paper, we review the latest research on oral health in people who have had a stroke and the care dilemmas this creates. We reflect on what people who have had a stroke and their carers think about the oral care patients receive and investigate the challenges of its provision in this population. We identify gaps in knowledge about optimum oral care for stroke patients and areas where further research is needed to provide the evidence to support best practice.

Method

This is a narrative review, based on findings from systematic reviews, primary research, other published literature combined with expert and lay opinion. It provides a holistic interpretation of the current situation in relation to oral care in stroke patients.

Consensus on knowledge gaps for optimum oral care and research priorities was reached after a series of discussions with stroke survivors, carers, clinical and academic experts in dental care, health economics, physical medicine, speech and language therapy, medical imaging, public health and nursing. It takes account of the pluralities and diversities of the disciplines involved. An iterative process to synthesise the main issues and their implications, identify gaps and directions for future research was undertaken through a series of meetings and discussions. The manuscript was drafted and revised by all authors.

Findings

A prompt oral examination and assessment in patients who have had a stroke is important because it determines oral hygiene needs, informs an oral care plan and identifies problems that may affect recovery.36 Available oral assessment protocols score features such as saliva, soft tissues and odour; with dental plaque, oral function, swallowing, voice quality and hard tissue assessment suggested in some. However, few oral assessment tools exist, and those that do, are not specifically developed for, or validated in patients with stroke and are rarely used.19,37 Nurses are best placed to conduct the initial oral assessment and can also be trained to identify patients who may need referral to a dental specialist.38

Dependent stroke survivors rely on nursing staff to help them, but without evidence based pathways, adequate knowledge, skills, confidence and support from senior staff and dental professionals, nurses cannot provide effective, good quality oral care.

Hospitalisation, reduced food and drink intake, increased exposure to antibiotics and dependency can affect stroke patients’ ability to maintain oral hygiene effectively.14,19 Dehydration and xerostomia can be a particular problem because of oxygen therapy, mouth breathing, side-effects of medications and reduced food and fluid intake.39,40 In these circumstances, oral care can be challenging and is often given low priority by nurses.41

Oral care can be further complicated where swallow safety is compromised, as patients may be unable to keep any food residue, toothpaste or rinsing fluids from entering their airway.

There is currently neither evidence nor consensus guidance for best practice in assessment of need, equipment, procedure or how frequently oral care should be provided. Practice in different locations varies widely and staff feel insufficiently trained to deliver oral care effectively.19,42–44 The current lack of appropriate training and failure to prioritise oral care within the stroke care pathway has the biggest impact on patients with greatest need who are at high risk of complications.10

Patient, carer and professionals’ perspectives

For those who survive a stroke, life often changes dramatically as they and their families learn to live with the disabling consequences such as paralysis, muscle weakness, cognitive impairment, fatigue, anxiety and depression.45,46 Stroke patients often experience oral discomfort and pain, oral infections (especially oral candidiasis) and difficulties in denture wearing.2,3,14,47 Normal daily activities that affect oral hygiene such as eating, drinking and tooth brushing can be severely disrupted.48

Table 1 summarises findings from studies exploring stroke patients, carers and professionals experience of oral care. Barriers such as fear of possibly causing harm, lack of knowledge, skill or ability, lack of time, low priority, inadequate resources and lack of guidance are the main explanations provided by carers and professionals for inadequate oral care provision in stroke patients.1,49–51

Table 1.

Key points.

| • Oral care is perceived as important by patients, carers and professionals.52,53 |

| • Patients feel anxious and distressed about their appearance and worry that they may have halitosis.2,53 |

| • Lack of care is common and is a cause of distress for patients and their families.52,54 |

| • Nurses make assumptions about patients’ ability to attend to their own oral care, and patients find it difficult to ask for what they need.42,53 |

| • Relatives and friends express empathy but feel powerless to intervene and provide the care themselves.42,53 |

| • Basic materials needed to provide good oral care are often unavailable in stroke units.44 |

| • There is uncertainty and fear about the best way to provide oral care for stroke patients.51,53 |

Evidence

There are few evidence-based assessment tools, guidelines and protocols for oral care in the stroke population.19,55,56 A Cochrane systematic review on staff-led interventions for improving oral hygiene following a stroke was updated in 2011.1 The review included three trials. Gosney et al.57 found high carriage of and colonisation by aerobic Gram-negative bacteria in stroke patients. In this randomised controlled trial, the use of an oral decontaminating gel reduced the presence of bacteria and documented episodes of pneumonia, but mortality remained unchanged. Frenkel et al.58 found that education can improve caregivers’ knowledge, attitudes and oral care performance. Fields59 found that the ventilator associated pneumonia rate in an intensive care unit that included, but was not specific to, stroke patients dropped to zero in the intervention group within a week of beginning a tooth-brushing regime. After six months, the control group was dropped, and all intubated patients’ teeth were brushed every 8 hours, maintaining a zero rate of ventilator-associated pneumonia until the end of the two-year study. Lack of adequate data meant that the findings were not included in the meta-analysis.

The Cochrane review concluded that provision of training in oral care interventions can improve staff knowledge and attitudes, cleanliness of patients' dentures and reduce incidence of pneumonia. However, evidence was weak and improvements in the cleanliness of patients’ teeth were not observed. Table 2 provides an overview of the relevant research published on oral care in stroke patients since the 2011 Cochrane review update.

Table 2.

Recent oral care research.

| Author | Design | Study | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smith et al., 201660 | Mixed methods feasibility study (29 patients, 10 staff) | Staff education and training, and twice-daily brushing with chlorhexidine gel (or non-foaming toothpaste) and denture care if required. | Interventions were feasible, acceptable and raised knowledge and awareness. |

| Wagner et al, 201610 | Quasi-experimental, n= 1656 (949 in the intervention group 707 controls) | To compare the proportion of pneumonia cases in hospitalised stroke patients before and after implementation of an oral health care intervention in the United States. | Systematic oral health care was associated with decreased odds of hospital-acquired pneumonia. |

| Kuo et al, 201561 | Randomised controlled trial (RCT), n=94 (48 in intervention group, 46 controls) | To evaluate the effectiveness of a home-based oral care training programme for stroke survivors in Taiwan. | Poor oral hygiene and neglect of oral care was observed at baseline.The intervention group had significantly lower tongue coating and dental plaque than the control group.There was no difference in symptoms of respiratory infection between the groups. |

| Dai et al, 201520 | Systematic review of observational studies | Studies exploring oral health outcomes and oral-health-related behaviours in stroke patients. | Patients with stroke had poorer oral health than healthy controls, and prior to the stroke tended to be less frequent dental care attenders. |

| Horne et al, 201542 | Qualitative study. Two focus groups (n=10) | Explored experiences and perceptions about the barriers to providing oral care in stroke units in Greater Manchester (UK). | Lack of understanding of the importance of oral care, inconsistent practice, lack of equipment and inadequate training for staff and carers. |

| Juthani-Mehta et al, 201562 | Non stroke-specific cluster RCT, n=834 (434 intervention, 400 control) | Manual tooth/gum brushing plus 0.12% chlorhexidine oral rinse delivered twice a day and upright feeding position was compared to usual care in nursing homes in the United States. | Fewer cases of pneumonia in the intervention group, the difference was not statistically significant. |

| Chipps et al, 20148 | Randomised controlled pilot study, n=51 (29 intervention, 22 control) | A standardised oral care intervention performed twice a day was compared to usual care in a stroke rehabilitation setting in the United States. | Subjects in both groups showed improvement in their oral health assessments, swallowing and oral intake over time, but the difference was not statistically significant.Staphylococcus aureus colonisation in the control group almost doubled (from 4.8% to 9.5%), while colonisation in the intervention group decreased (from 20.8% to 16.7%) but again differences were not statistically significant. |

| Kim et al, 201447 | RCT n=56 (29 intervention, 29 control) | Impact of an oral care programme delivered to patients who had recently experienced their first stroke in the intensive care unit of a university hospital in Korea. | Plaque index, gingival index and presence of candida in the saliva were significantly lower in the intervention compared to the control group. There was no significant difference between the groups in clinical attachment, tooth loss or presence of Candida albicans on the tongue. |

| Seguin et al, 201463 | RCT, n=179 (91 intervention, 88 control) | A non-stroke-specific trial conducted in six intensive care units in France. The intervention consisted of washing the oropharyngeal cavity with diluted povidone-iodine or placebo. | No evidence to recommend oral care with povidone-iodine to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in high-risk patients. The use of povidone-iodine seemed to increase the risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome. |

| Lam et al, 201364 | RCT, n = 102 (33 in group 1, 34 in group 2, 35 in group 3) | Three groups in a stroke rehabilitation ward in Hong Kong were provided with an electric toothbrush and standard fluoride toothpaste. Group one received oral hygiene instruction only, group two received this plus chlorhexidine mouthwash and group three received the same as two, plus assistance with brushing twice a week. | Poor oral hygiene was noted in all groups at baseline. Significant reductions in dental plaque and gingival bleeding were noted in both intervention groups 2 and 3 compared to group 1. The impact on pneumonia could not be ascertained as no cases were recorded. |

| Lam et al, 201265 | Literature review | A review of non-stroke-specific studies that evaluated the effectiveness of oral hygiene interventions in reducing oropharyngeal carriage of aerobic and facultatively anaerobic gram-negative bacilli (AGNB) in medically compromised patients. | The effects of antiseptic agents could not be discerned from the adjunctive mechanical oral hygiene measures. High-quality RCTs are needed to determine which combinations of oral hygiene interventions are most effective in eliminating or reducing AGNB carriage. |

Discussion

Adequate oral care improves patients’ oral health, comfort and quality of life, but definitive evidence of its ability to reduce the risk of pneumonia is lacking.55 Two non-stroke specific nursing home based studies, one from Japan (2002) and the second from the United States (2008) evaluated the impact of an oral care intervention in a setting where there were a number of stroke patients.6,66 Both studies reported fewer cases of pneumonia (or related death) amongst residents that received oral health care but the Japanese trial excluded incapacitated, dysphagic, unstable and unconscious residents.6 Unfortunately, in many trials the challenges associated with gaining informed consent result in patients who are most dependent for oral care being excluded.

Several guidelines refer to oral care following a stroke (See Supplementary Appendix 1 which will be available online with this article, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2396987318775206). Many refer to the lack of evidence to support detailed guidance. Answers to basic questions about whether it is best to use an electric or manual toothbrush, size and type of head, which – if any toothpaste, how frequently care should be given, etc. are not provided. No guidelines contain information or advice to alleviate nurses’ anxieties about how best to reduce risk of choking when delivering oral care for dysphagic stroke patients.

It is a limitation of this study that there is little evidence about oral care practice in stroke units across Europe, hence most of the included studies are from elsewhere.

Future considerations

Emerging evidence supports the rationale for developing best practice guidelines for oral care in stroke care units.19 High-quality evidence is needed to inform improvements in staff training and delivery of consistent oral care. Protocols need to be developed that focus on maintenance of dentition and a quality of life associated with having acceptable oral function. Protocols need to describe simple preventative measures at every stage in the care pathway, combined with early diagnosis and management of significant dental pathology. Several oral hygiene interventions appear to be feasible and well-tolerated in early-stage studies.47,55,59,60,63,64

Research is needed to inform the spectrum and variation in existing ‘usual’ care and service provision (including the role of specialist dental services) as well as optimal oral assessment tool(s), including for patients who are intubated as well as later during the rehabilitation phase.

Safety, acceptability and resources required to deliver high-quality oral care assessments and protocols needs to be established.

Clarity is needed about the multi-disciplinary team support required, especially around optimisation of effective staff education and training, including from dental specialists.

Ultimately, large phase three randomised trials supported by realistic recruitment and clinically relevant strategies, economic evaluation and implementation strategies are required. They need to produce practical clinical outcomes that address barriers and facilitators to change and adoption of evidence into policy and practice.

Priority should be given to research that provides evidence to inform standards for oral care delivery, and guidelines for each patient with individualised care plans that illustrate the safest, most efficient equipment to use.

Conclusions

There is a lack of knowledge about how and what oral care is currently provided as well as inadequate research to inform best practice in acute stroke care, rehabilitation and nursing home settings.

Staff feel inadequately prepared to provide oral care, especially when dysphagia or other problems are present and it tends to be given low priority. This review provides an objective platform to encourage health and care services to incorporate oral care into future stroke pathways, whilst stimulating greater engagement with this under-researched area.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix 1 for Oral care after stroke: Where are we now? by Mary Lyons, Craig Smith, Elizabeth Boaden, Marian C Brady, Paul Brocklehurst, Hazel Dickinson, Shaheen Hamdy, Susan Higham, Peter Langhorne, Catherine Lightbody, Giles McCracken, Antonieta Medina-Lara, Lise Sproson, Angus Walls and Dame Caroline Watkins in European Stroke Journal

Acknowledgements

Mary Harrington, Head of Speech & Language Therapy, Hull & East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust reviewed and commented on the paper.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a NIHR CRN/British Association of Stroke Physicians stroke writing group grant.

Informed consent

Not applicable as this is a review article.

Ethical approval

Not applicable as this is a review article and contains no primary research.

Guarantor

CLW.

Contributorship

CW and CS devised the conceptual framework. CS, EB, MCB, HD, ShH, SH, ML and GMcC contributed sections to this paper. ML synthesised contributions with support from PL, CL, AM-L, LP, AW and CW. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final version of the paper.

References

- 1.Brady MC, Furlanetto D, Hunter R, et al. Staff-led interventions for improving oral hygiene in patients following stroke. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2006. (Updated 2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schimmel M, Leemann B, Christou P, et al. Oral health-related quality of life in hospitalised stroke patients. Gerodontology 2011; 28: 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Locker D, Clarke M and, Payne B. Self-perceived oral health status, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction in an older adult population. J Dent Res 2000; 79: 970–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langhorne P, Stott D, Robertson L, et al. Medical complications after stroke a multicenter study. Stroke 2000; 31: 1223–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzan IL, Cebul RD, Husak SH, et al. The effect of pneumonia on mortality among patients hospitalized for acute stroke. Neurology 2003; 60: 620–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoneyama T, Yoshida M, Ohrui T, et al. Oral care reduces pneumonia in older patients in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sjogren P, Nilsson E, Forsell M, et al. A systematic review of the preventive effect of oral hygiene on pneumonia and respiratory tract infection in elderly people in hospitals and nursing homes: Effect estimates and methodological quality of randomized controlled trials. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56: 2124–2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chipps E, Gatens C, Genter L, et al. Pilot study of an oral care protocol on poststroke survivors. Rehabil Nurs 2014; 39: 294–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorensen RT, Rasmussen RS, Overgaard K, et al. Dysphagia screening and intensified oral hygiene reduce pneumonia after stroke. J Neurosci Nurs 2013; 45: 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner C, Marchina S, Deveau JA, et al. Risk of stroke-associated pneumonia and oral hygiene. Cerebrovasc Dis) 2016; 41: 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S and, Hamdy S. Dysphagia in stroke patients. Postgrad Med J 2006; 82: 383–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martino R, Foley N, Bhogal S, et al. Dysphagia after stroke: Incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke 2005; 36: 2756–2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teismann IK, Steinstraeter O, Stoeckigt K, et al. Functional oropharyngeal sensory disruption interferes with the cortical control of swallowing. BMC Neurosci 2007; 8: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter RV, Clarkson JE, Fraser HW, et al. A preliminary investigation into tooth care, dental attendance and oral health related quality of life in adult stroke survivors in Tayside, Scotland. Gerodontology 2006; 23: 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hori K, Ono T, Iwata H, et al. Tongue pressure against hard palate during swallowing in post-stroke patients. Gerodontology 2005; 22: 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim IS and, Han TR. Influence of mastication and salivation on swallowing in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 86: 1986–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu HW, McMillan AS, McGrath C, et al. Oral carriage of yeasts and coliforms in stroke sufferers: A prospective longitudinal study. Oral Dis 2008; 14: 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millns B, Gosney M, Jack C, et al. Acute stroke predisposes to oral gram-negative bacilli–a cause of aspiration pneumonia?. Gerontology 2003; 49: 173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwok C, McIntyre A, Janzen S, et al. Oral care post stroke: A scoping review. J Oral Rehabil 2015; 42: 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai R, Lam OL, Lo EC, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical, microbiological, and behavioural aspects of oral health among patients with stroke. J Dent 2015; 43: 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lafon A, Pereira B, Dufour T, et al. Periodontal disease and stroke: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Neurol 2014; 21: 1155–1161, e66–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam OL, McMillan AS, Li LS, et al. Oral health and post-discharge complications in stroke survivors. J Oral Rehabil 2016; 43: 238–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azarpazhooh A, Leake JL. Systematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral health. J Periodontol 2006; 77: 1465–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scannapieco FA, Bush RB, Paju S. Associations between periodontal disease and risk for nosocomial bacterial pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol 2003; 8: 54–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keijser B, Zaura E, Huse S, et al. Pyrosequencing analysis of the oral microflora of healthy adults. J Dent Res 2008; 87: 1016–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boaden E, Lyons M, Singhrao SK, et al. Oral flora in acute stroke patients: A prospective exploratory observational study. Gerodontology 2017; 34: 343–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, et al. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2014; 383: 245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Office for National Statistics Social Survey Division Information Centre for Health and Social Care. Adult Dental Health Survey, 2009. 2nd ed. In: UK Data Service. SN: 6884, 2012.

- 29.Derks J, Tomasi C. Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology. J Clin Periodontol 2015; 42: S158–S171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Widsträm E, Eaton KA. Oral healthcare systems in the extended European Union. Oral Health Prev Dent 2004; 2: 155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glick M, Monteiro da Silva O, Seeberger GK, et al. FDI Vision 2020: Shaping the future of oral health. Int Dent J 2012; 62: 278–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersson P, Renvert S, Sjogren P, et al. Dental status in nursing home residents with domiciliary dental care in Sweden. Commun Dent Health 2017; 34: 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pickett FA. State of evidence: Chronic periodontal disease and stroke. Can J Dent Hygiene 2012; 46. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida M, Murakami T, Yoshimura O, et al. The evaluation of oral health in stroke patients. Gerodontology 2012; 29: e489–e493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leira Y, Seoane J, Blanco M, et al. Association between periodontitis and ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol 2016; 32: 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. National clinical guideline for stroke 5th ed. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2016.

- 37.Abidia RF. Oral care in the intensive care unit: A review. J Contemp Dent Pract 2007; 8: 76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones H. Oral care in intensive care units: A literature review. Spec Care Dentist 2005; 25: 6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerr GD, Sellars C, Bowie L, et al. Xerostomia after acute stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2009; 28: 624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bahouth MN, Hillis A and, Gottesman R. A prospective study of the effect of dehydration on stroke severity and short term outcome. Stroke 2015; 46(1S). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costello T and, Coyne I. Nurses’ knowledge of mouth care practices. Br J Nurs 2008; 17: 2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horne M, McCracken G, Walls A, et al. Organisation, practice and experiences of mouth hygiene in stroke unit care: A mixed-methods study. J Clin Nurs 2015; 24: 728–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willumsen T, Karlsen L, Næss R, et al. Are the barriers to good oral hygiene in nursing homes within the nurses or the patients? Gerodontology 2012; 29: e748e–e755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Talbot A, Brady M, Furlanetto DL, et al. Oral care and stroke units. Gerodontology 2005; 22: 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luengo-Fernandez R, Paul NLM, Gray AM, et al. Population-based study of disability and institutionalization after transient ischemic attack and stroke: 10-year results of the Oxford Vascular Study. Stroke 2013; 44: 2854–2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crichton SL, Bray BD, McKevitt C, et al. Patient outcomes up to 15 years after stroke: Survival, disability, quality of life, cognition and mental health. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016; 87: 1091–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim E-K, Jang S-H, Choi Y-H, et al. Effect of an oral hygienic care program for stroke patients in the intensive care unit. Yonsei Med J 2014; 55: 240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terezakis E, Needleman I, Kumar N, et al. The impact of hospitalization on oral health: A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol 2011; 38: 628–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wårdh I, Hallberg LRM, Berggren U, et al. Oral health care—a low priority in nursing. Scand J Caring Sci 2000; 14: 137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams R. Qualified nurses lack adequate knowledge related to oral health, resulting in inadequate oral care of patients on medical wards. J Adv Nurs 1996; 24: 552–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brady MC and, Furlanetto D. Oral health care following stroke - a review of assessments and protocols. Clin Rehab 2009; 23: 7565–7763. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salamone K, Yacoub E, Mahoney A-M, et al. Oral care of hospitalised older patients in the acute medical setting. Nurs Res Pract 2013; 2013: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dickinson H. Improving the evidence base for oral assessment in stroke patients. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Central Lancashire, UK, 2016.

- 54.Health Education England. Mouth Care Matters. 2017.

- 55.Brady MC, Stott DJ, Norrie J, et al. Developing and evaluating the implementation of a complex intervention: Using mixed methods to inform the design of a randomised controlled trial of an oral healthcare intervention after stroke. Trials 2011; 12: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karki AJ, Monaghan N, Morgan M. Oral health status of older people living in care homes in Wales. Br Dent J 2015; 219: 331–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gosney M, Martin MV, Wright AE. The role of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in acute stroke. Age Ageing 2006; 35: 42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frenkel HF, Harvey I, Newcombe RG. Improving oral health of institutionalised elderly people by educating caregivers: A randomised controlled trial. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol 2001; 29: 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fields LB. Oral care intervention to reduce incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in the neurologic intensive care unit. J Neurosci Nurs 2008; 40: 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith CJ, Horne M, McCracken G, et al. Development and feasibility testing of an oral hygiene intervention for stroke unit care. Gerodontology 2016; 34: 110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuo YW, Yen M, Fetzer S, et al. Effect of family caregiver oral care training on stroke survivor oral and respiratory health in Taiwan: A randomised controlled trial. Commun Dent Health 2015; 32: 137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Juthani-Mehta M, Van Ness PH, McGloin J, et al. A cluster-randomized controlled trial of a multicomponent intervention protocol for pneumonia prevention among nursing home elders. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60: 849–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seguin P, Laviolle B, Dahyot-Fizelier C, et al. Effect of oropharyngeal povidone-iodine preventive oral care on ventilator-associated pneumonia in severely brain-injured or cerebral hemorrhage patients: A multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2014; 42: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lam OL, McMillan AS, Samaranayake LP, et al. Randomized clinical trial of oral health promotion interventions among patients following stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94: 435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lam OL, McGrath C, Li LS, et al. Effectiveness of oral hygiene interventions against oral and oropharyngeal reservoirs of aerobic and facultatively anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. Am J Infect Control 2012; 40: 175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bassim CW, Gibson G, Ward T, et al. Modification of the risk of mortality from pneumonia with oral hygiene care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56: 1601–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Appendix 1 for Oral care after stroke: Where are we now? by Mary Lyons, Craig Smith, Elizabeth Boaden, Marian C Brady, Paul Brocklehurst, Hazel Dickinson, Shaheen Hamdy, Susan Higham, Peter Langhorne, Catherine Lightbody, Giles McCracken, Antonieta Medina-Lara, Lise Sproson, Angus Walls and Dame Caroline Watkins in European Stroke Journal