Nicotine permeates into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) where it begins an “inside-out” pathway that leads to addiction. Shivange et al. develop genetically encoded nicotine biosensors and show that nicotine and varenicline equilibrate in the ER within seconds of extracellular application.

Abstract

Nicotine dependence is thought to arise in part because nicotine permeates into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it binds to nicotinic receptors (nAChRs) and begins an “inside-out” pathway that leads to up-regulation of nAChRs on the plasma membrane. However, the dynamics of nicotine entry into the ER are unquantified. Here, we develop a family of genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors for nicotine, termed iNicSnFRs. The iNicSnFRs are fusions between two proteins: a circularly permutated GFP and a periplasmic choline-/betaine-binding protein engineered to bind nicotine. The biosensors iNicSnFR3a and iNicSnFR3b respond to nicotine by increasing fluorescence at [nicotine] <1 µM, the concentration in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of a smoker. We target iNicSnFR3 biosensors either to the plasma membrane or to the ER and measure nicotine kinetics in HeLa, SH-SY5Y, N2a, and HEK293 cell lines, as well as mouse hippocampal neurons and human stem cell–derived dopaminergic neurons. In all cell types, we find that nicotine equilibrates in the ER within 10 s (possibly within 1 s) of extracellular application and leaves as rapidly after removal from the extracellular solution. The [nicotine] in the ER is within twofold of the extracellular value. We use these data to run combined pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic simulations of human smoking. In the ER, the inside-out pathway begins when nicotine becomes a stabilizing pharmacological chaperone for some nAChR subtypes, even at concentrations as low as ∼10 nM. Such concentrations would persist during the 12 h of a typical smoker’s day, continually activating the inside-out pathway by >75%. Reducing nicotine intake by 10-fold decreases activation to ∼20%. iNicSnFR3a and iNicSnFR3b also sense the smoking cessation drug varenicline, revealing that varenicline also permeates into the ER within seconds. Our iNicSnFRs enable optical subcellular pharmacokinetics for nicotine and varenicline during an early event in the inside-out pathway.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Existing data show that nicotine evokes two processes at neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors (nAChRs). Historically, the best-characterized process is activation of nAChRs on the plasma membrane (PM). If one considers events at the scale of a neuron, activation of nAChRs at the PM may be termed the “outside-in” pathway. Like activation by the endogenous neurotransmitter ACh, activation by exogenous nicotine via the outside-in activation pathway involves an influx of Na+ and Ca2+ ions, depolarization and therefore increased frequency of neuronal action potentials. The outside-in pathway, and perhaps the subsequent desensitization of nAChRs, leads to the acute effects after nicotine enters the airways either from tobacco combustion (smoking) or from an electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS; “vaping”). These acute effects, beginning within <1 min after inhalation and lasting for dozens of minutes include a sense of well-being, a cognitive boost, appetite suppression, increased tolerance of stressful stimuli, and suppression of withdrawal (Miwa et al., 2011; Naudé et al., 2015; Nees, 2015; Picciotto et al., 2015).

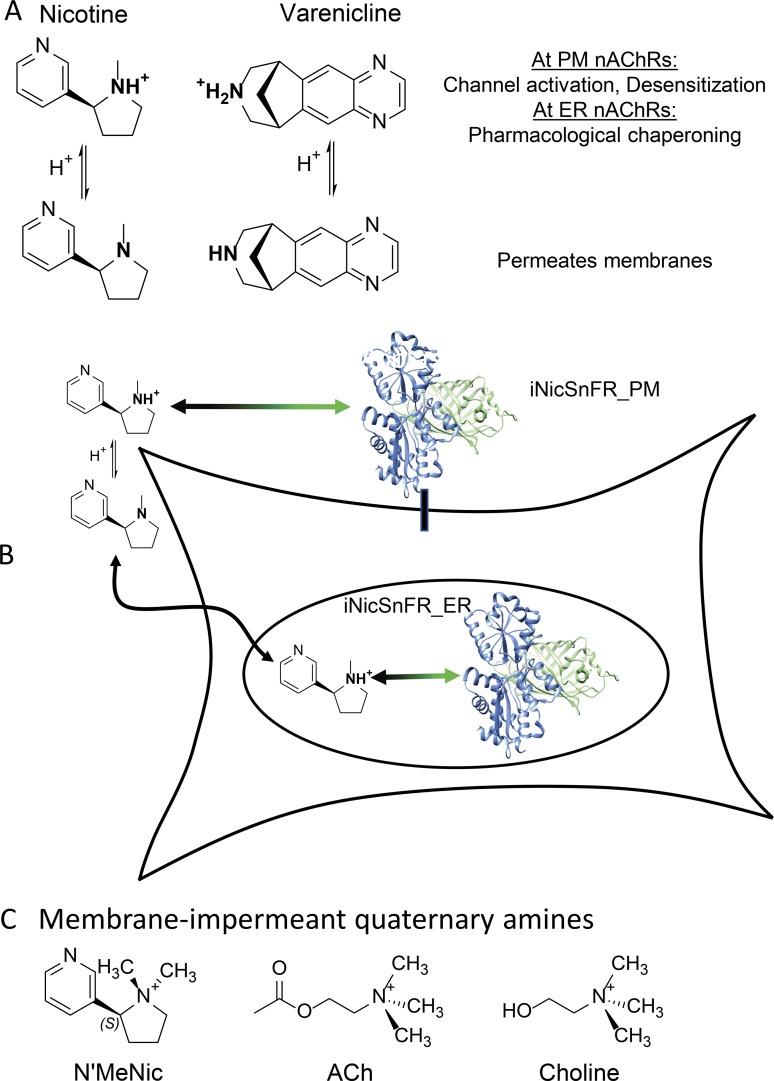

Since approximately 2005, evidence has been accumulating for a second process. We term this the “inside-out” pathway, because it begins when nicotine permeates into the ER. In the ER, nicotine binds to nascent nAChRs and becomes a stabilizing pharmacological chaperone for α4- and β2-subunit–containing (α4β2*) nAChRs, increasing their exit from the ER (Fig. 1 A; Kuryatov et al., 2005; Sallette et al., 2005; Lester et al., 2009). The inside-out pathway leads to up-regulation of nAChRs on the PM. The inside-out pathway results, jointly, from three properties (Fig. 1 A). (1) Like ACh, nicotine activates nAChRs (a pharmacological property). (2) In contrast to ACh, nicotine has a neutral, membrane-permeant form (a pharmacokinetic property). (3) In contrast to hydrolysis of ACh within <1 ms by Ach sterase, catabolic oxidation of nicotine proceeds on a time scale of ∼30 min, primarily by cytochrome P450 (another pharmacokinetic property; Henderson and Lester, 2015; Tanner et al., 2015).

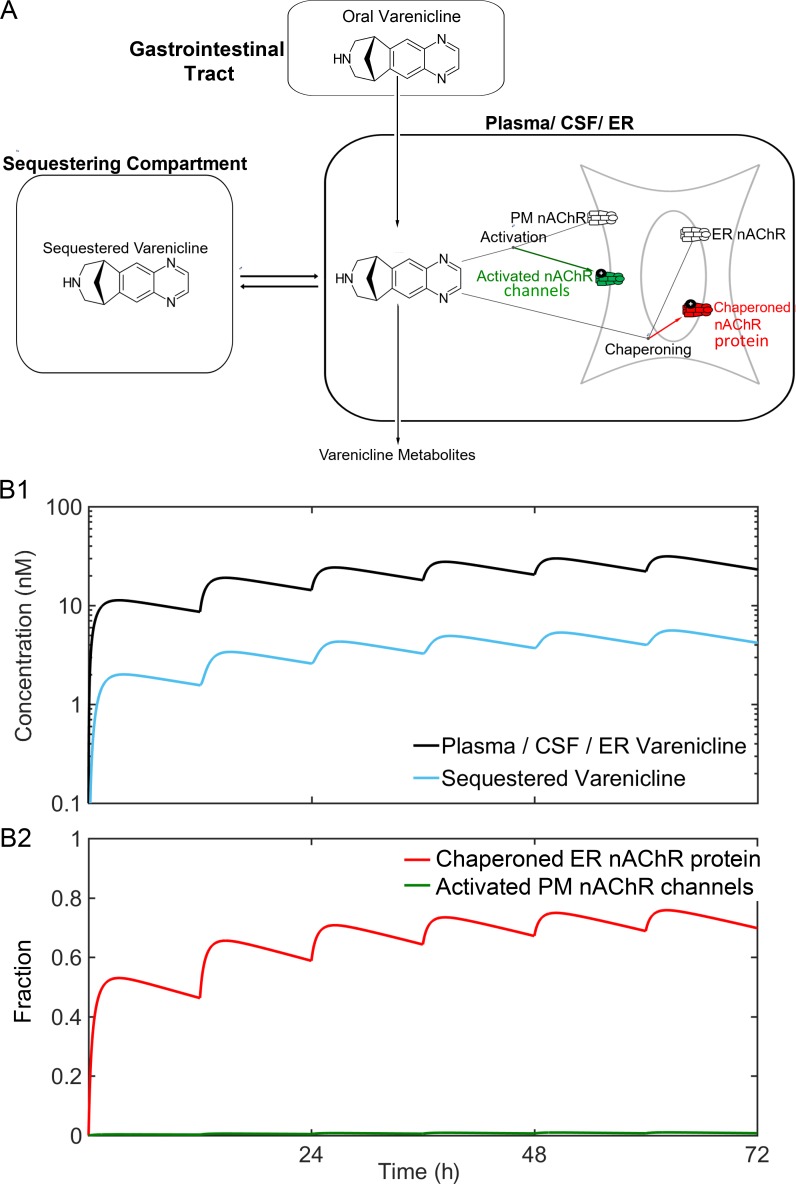

Figure 1.

Strategy of the experiments. (A) Nicotine (pKa, 7.5–8.1) and varenicline (pKa, 9.5–10) are weak bases. They interconvert on a millisecond time scale between protonated and deprotonated forms; these are respectively membrane impermeant and permeant. (B) The tactic of confining a genetically encoded fluorescent nicotinic drug sensor to the PM or the ER. (C) Choline, ACh, and N’MeNic exist only as charged, membrane-impermeant forms near physiological pH.

The research community has not yet reported decisive tests for the relative importance of the inside-out and outside-in pathways in nicotine dependence. Several laboratories are testing the hypothesis that the selective up-regulation of specific nAChR subtypes via the inside-out pathway is necessary and sufficient for some early events (days to weeks) of nicotine dependence (Govind et al., 2009; Henderson and Lester, 2015). Nicotine-induced up-regulation of nAChRs via chaperoning is post-translational, involving neither gene activation nor mRNA stability of nAChR subunits (Henderson and Lester, 2015).

A satisfactory comparison of the outside-in and inside-out pathways during smoking/vaping has been hampered by lack of information about the pharmacokinetics of nicotine at the subcellular scale: How long does it take nicotine to permeate into the ER, and what is its concentration there (Lester et al., 2009; Rollema et al., 2010; Hussmann et al., 2012)? Previous data show that, when nicotine is applied for more than several hours, it up-regulates nAChRs. This up-regulation has an EC50 of ∼30 nM (Kuryatov et al., 2005). It has not been known (1) whether nicotine concentration in the ER reaches the EC50 for up-regulation; (2) if so, how quickly; and (3) how quickly nicotine leaves the ER.

To approach these questions quantitatively, we have developed a series of genetically encoded intensity-based nicotine-sensing fluorescent reporters (iNicSnFRs). These biosensors comprise a fusion between a bacterial periplasmic-binding protein (PBP) moiety (276 amino acids), a circularly permuted GFP (cpGFP) moiety (244 amino acids), joining regions (“linkers”), and epitope tags. The development of the glutamate biosensor iGluSnFR (Marvin et al., 2013) has provided a model for this study. We report on use of a novel PBP moiety and on mutations that allow the PBP moiety of the biosensor to bind nicotine. We have directed these iNicSnFRs either to the PM (at the start of the outside-in pathway) or to the lumen of the ER (at the start of the inside-out pathway; Fig. 1 B). We have also verified the compartmentalization of the iNicSnFRs by showing that the fluorescence response to nicotine contrasts with responses to membrane-impermeant quaternary amines (Fig. 1 C).

Smoking cessation has become desirable for individual health and for public health (Royal College of Physicians, 2016). Varenicline (shown in Fig. 1 A), a partial agonist for α4β2 nAChRs and full agonist for α7 nAChRs, is now the most effective synthetic drug for smoking cessation. Nonetheless, varenicline therapy succeeds in only a minority of people who aspire to quit smoking (Fagerström and Hughes, 2008). Varenicline also permeates modestly well into the central nervous system (Rollema et al., 2010). Varenicline has a half-life of ∼24 h in human plasma (Faessel et al., 2006) and presumably in human brain. Exposure to varenicline also up-regulates α4β2 nAChRs (Turner et al., 2011; Marks et al., 2015; Govind et al., 2017), an indication that it too participates in the inside-out pathway. We therefore sought to determine whether varenicline also enters the ER and, if so, how much and how quickly. Serendipitously, an iNicSnFR also binds to and senses varenicline, and we suggest how varenicline’s entry into the ER may limit its therapeutic actions.

Materials and methods

Directed evolution of iNicSnFR proteins using bacterial-expressed protein assays

The Results section, below, begins by describing the overall strategy in constructing the iNicSnFRs. Class F PBPs consist of two domains that move relative to each other when the ligand binds at the interdomain interface (Berntsson et al., 2010). Previous biosensor constructs have placed a cpGFP molecule within the PBP. We constructed and measured ∼12,000 mutants iteratively, using fluorescence measurements as described below. We incorporated four additional linker1 residues before the N terminus of the “superfolder” cpGFP gene (Pédelacq et al., 2006; Marvin et al., 2018) and four additional linker2 residues after the C terminus of the superfolder cpGFP, because this cpGFP variant functions well in the ER (Aronson et al., 2011). We inserted linker1-cpGFP-linker2 at candidate positions within OpuBC sequence at positions near the interdomain interface of the PBP, based on previous structural data cited in Results for choline- and betaine-binding class F PBPs. We optimized linker1 and linker2 with site-saturated mutagenesis (SSM).

The ligand-binding site (originally for choline and/or betaine) lies at the interdomain interface of the PBP. To optimize the ligand site for nicotine, we performed SSM on several residues near the possible cation-π residues (first-shell residues that lie within 7 Å of the ligand binding pocket; Fig. S1), as well as on “second-shell” residues (residues that showed intraprotein interactions with the first-shell residues). Mutagenesis was performed by slight modifications to the Quikchange mutagenesis protocol (Agilent). Each round of SSM used NN(C/G) oligonucleotides that provided > 96% residue coverage for a collection of 188 randomly chosen clones.

One design goal was a 30% increase in fluorescence (ΔF/F0 = 0.3) at [nicotine] = 1 µM, a concentration thought to lie in the range of the peak [nicotine] in the plasma and brain of a smoker (Benowitz et al., 1991; Rollema et al., 2010). In preliminary characterization, lysates were tested with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 535 nm. Automated 96-well fluorescence plate readers were used to measure resting and nicotine-induced fluorescence (F0 and ΔF, respectively; Tecan M1000, equipped with monocomators; and Tecan Spark M10, equipped with filters). Promising clones were amplified and sequenced. The beneficial substitutions identified were combined with side-directed mutagenesis (SDM), and the “best” combination in each round of evolution was used as a template for the next round of SSM (Fig. S2).

We conducted one or more rounds of SSM experiments at each of the 25 codons shown in Fig. S1. In sum, these experiments improved the ΔF/F0 at 1 µM nicotine by a factor ∼105 (Fig. S2). In early experiments on weakly responding constructs, we measured responses to much higher concentrations (up to 10 mM). We extrapolated to responses at 1 µM nicotine, based on the EC50, on the maximal ΔF (ΔFmax) and the observed Hill coefficient of ∼1. We used automated liquid-handling devices at several stages of mutagenesis and quantification.

Measurements on purified iNicSnFRs

Biosensors selected for further study were purified with the His6 sequence (Fig. S1). Proteins were purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography as described (Marvin et al., 2013), using PBS, pH 7.4, and elution in an imidazole gradient (10–200 mM). Proteins were concentrated by centrifugation through a 10- or 30-kD cutoff column and by dialysis against PBS. The dialyzed protein was quantified, and 50 or (preferably) 100 nM was used in dose–response studies to characterize responses to various ligands.

We conducted isothermal titration calorimetry experiments with a Malvern Microcal iTC200 instrument. Purified iNicSnFR3a (100 µM) was titrated with 1 mM nicotine in PBS at 25°C. Analyses used the Origin software bundled with that instrument.

Proteins purified by size-exclusion chromatography were subjected to high-throughput crystallization trials in the presence of nicotine. Crystals were grown with hanging drop vapor diffusion at room temperature. Promising crystals of iNicSnFR1 were obtained with 15 mg/ml protein, 6 mM nicotine, 50 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and 30% vol/vol polyethylene glycol monomethyl ether 550. The diffraction datasets were collected at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory. The data were reduced using Mosflm (Powell et al., 2017) and Scala (Evans, 2011). The structure was solved using the CCP4 software suite (Evans, 2011) to carry out molecular replacement using a solved unliganded, open structure of an earlier version of iAChSnFR construct (Borden et al., in preparation). The structure was iteratively rebuilt using Coot (Emsley et al., 2010) and refined using PHENIX. The maximum resolution was 2.4 Å. After refinement (Table S1), the electron density for the ligand was incompletely resolved; therefore the molecular docking program SwissDock was used to study protein–ligand interactions (Fig. 2 B) and to design further SSM libraries. After we obtained the modeled-liganded, partially closed structure of Fig. 2 B, we concentrated on mutating the residues noted; this structural information accelerated progress toward the criterion responses of ΔF/F0 = 0.3 at [nicotine] = 1 µM.

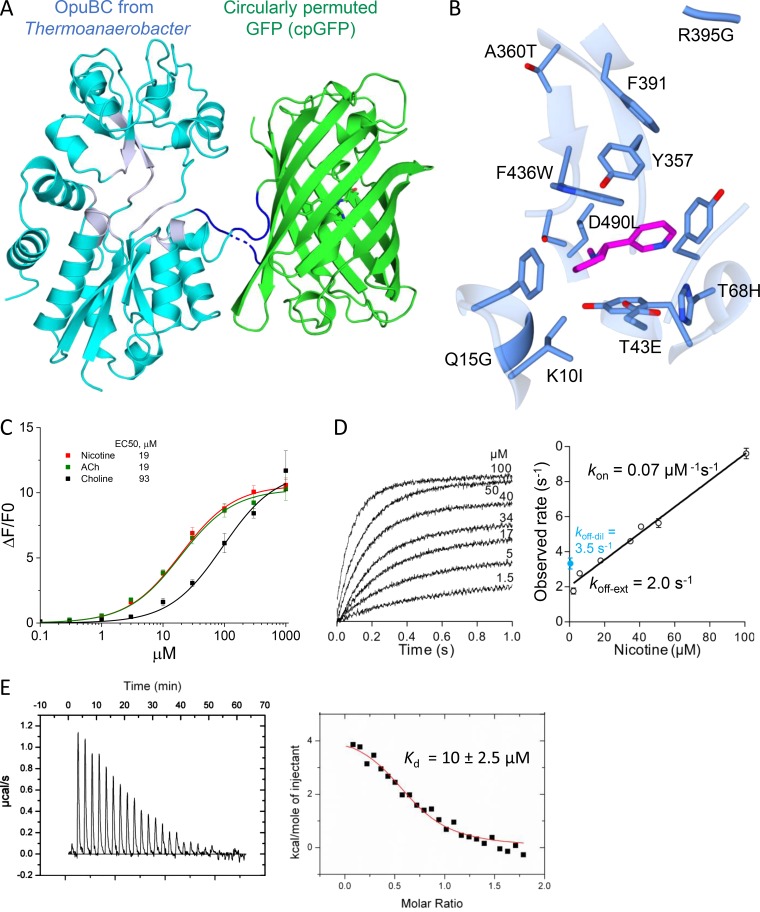

Figure 2.

The genetically encoded family of biosensors for nicotinic drugs, iNicSnFRs. (A) Cartoon of the x-ray crystallographic structure of iNicSnFR1, crystallized in the presence of nicotine. The structure is available as PDB file 6EFR. The iNiCSnFR family are fusion proteins. A superfolder cpGFP (shown in green) has been inserted into the coding sequence of OpuBC, a choline/betaine PBP from T. spX513. The linker sequences (shown in dark blue; see Fig. S1) were selected for optimal ΔF/F. One poorly resolved linker residue, Pro323, is shown as a dashed backbone. The engineered OpuBC is shown in cyan, except that the backbone residues near the incompletely resolved nicotine ligand are shown in gray. The nicotine-binding site lies between the two lobes of the PBP; these move relative to each other. (B) To generate later iNicSnFRs, the binding site of OpuBC was further engineered by mutagenesis for acceptable sensitivity to nicotine. ∼12,000 mutants were screened during the design of iNicSnFR3a and iNicSnFR3b. The image shows redesign of the nicotine-binding site of iNicSnFR1, naming the additional mutations present in iNicSnFR3a and iNicSnFR3b. Portions of the cartoon shown in gray are identical to the gray regions of OpuBC in A. The α-carbon atoms remain at the positions in the x-ray crystallographic data (PDB file 6EFR), and the conformers of the mutated side chains were selected based on the best-fit rotamer using University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco, CA) Chimera software. The pyrrolidine group of nicotine is at left, seen edge-on; the pyridine group is at right, seen from an acute angle. Also shown is Y357, which remains wild type in all iAChSnFR and iNicSnFR constructs (Fig. S1). The Y357A mutation renders all iNicSnFR and iAChSnFR constructs insensitive to the ligand. Also shown is F391, which remains unchanged in all iNicSnFR and iAChSnFR constructs, but differs from the glutamate in OpuBC. (C) Dose–response relations for purified iNicSnFR3a. Data were fitted to a single Hill equation with an assumed Hill coefficient of 1. Data are mean ± SEM (n ≤ 3). (D) Stopped-flow analysis. The rate constant for fluorescence decay, koff, was measured most consistently by extrapolation of the kon value to zero [nicotine] (koff-ext). The ratio, koff-ext/kon, gives an equilibrium-binding constant Kd = 29 µM. The blue symbols and label show measurements of koff in experiments that diluted an iNicSnFR3a-nicotine solution by 25-fold to [nicotine] values < 1 µM (koff-dil). (E) Isothermal titration calorimetry for nicotine. The data yield an equilibrium-binding constant Kd = 10 ± 2.5 µM, and a stoichiometry of 0.65 ± 0.03 moles of nicotine per mole of protein.

Spectrally resolved fluorescence measurements of pH dependence (Fig. 3, A–C) were conducted with an ISS (Champaign) K2 fluorometer running under MS-DOS. Excitation and emission bandwidths were 2 nm. Data were exported as ASCII files. Dose–response relations for ligands were conducted with the M1000 (Fig. 2 C) or Spark 10M (Fig. 3, D–H; and Fig. 9 A) plate reader. For excitation wavelength (λex) of 400 nm, an ideal emission filter would have been centered at ∼500 nm; but none was available, so we measured the ∼2-fold lower emission with a filter centered at an emission wavelength (λem) of 535 nm.

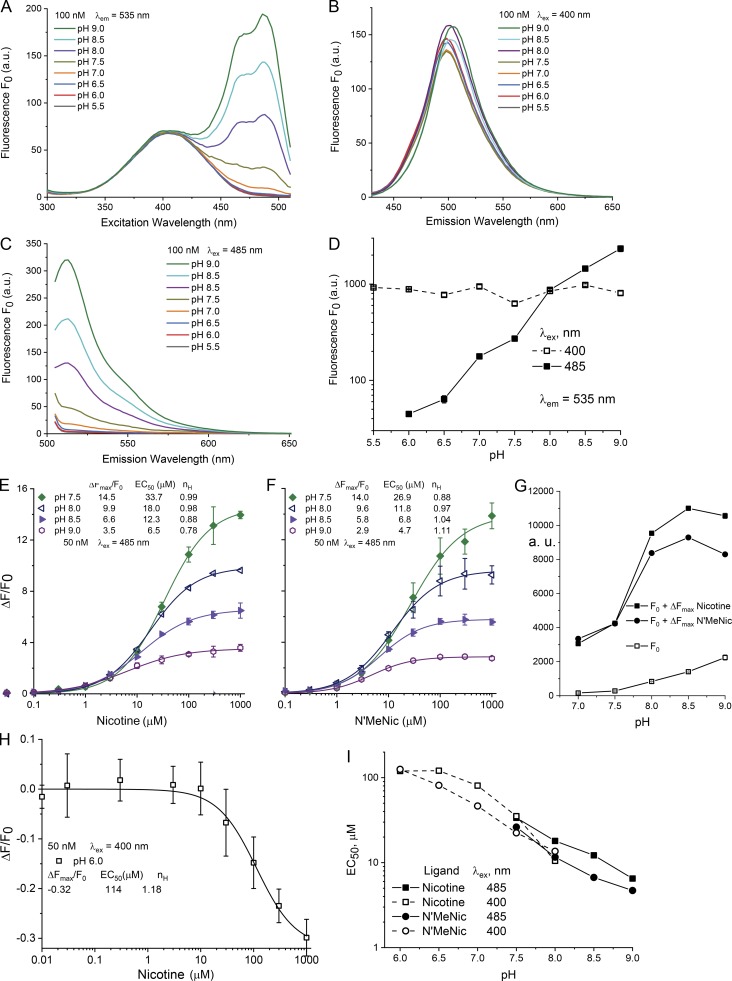

Figure 3.

The pH dependence of purified iNicSnFR3a in solution, over the range pH 5.5–9.0, at 25°C. Measurements were performed in 3× PBS, adjusted to nominal pH within 0.1 pH unit. (A–C) Measurements in a spectrofluorometer (see Materials and methods). 100 nM protein. Fluorescence is measured in the absence of ligand and termed F0. (A) Excitation spectra at various pH values, measured at a λem of 535 nm. (B) Emission spectrum at a λex of 400 nm. Note that F0 depends to only a limited extent on the pH. (C) Emission spectrum at λex = 485 nm. Note the strong dependence on pH. (D–H) Measurements in a 96-well plate reader, bandwidth 20 nm for excitation and 25 nm for emission; 50 nM protein, 25°C. (D) Data analogous to those of B and C. pH dependence of F0, with λex = 400 nm (open symbols) or 485 nm (closed symbols). Arbitrary units on the y axis (log scale; 30–3,000 arbitrary units; a.u.) differ from those taken with the instrument of A–C. Values for SEM are smaller than the size of the symbols. (E and F) Fluorescence dose–response relations for nicotine (E) and for N’MeNic (F). Excitation at 485 nm, at varying pH between 7.5 and 9.0. The data have been fitted to a single Hill equation, with parameters given in the legend. Error bars give SEM. Uncertainties for the ΔFmax/F0 and EC50 values are <10%, and for the Hill coefficient (nH) value are <0.2. (G) Summary of E and F to show both the unliganded fluoresce (F0) and maximal fluorescence (F0 + ΔFmax) in the pH range measured. (H) Exemplar dose–response relations from excitation at 400 nm, at pH 6.0. As expected (Barnett et al., 2017), nicotine produces a decrease in fluorescence intensity at 535 nm. The data have been fitted to a single Hill equation, with parameters given in the legend. Error bars give SEM. (I) Comparison of EC50 values for nicotine (squares) versus N’MeNic (circles). Data from experiments like those in B and C. Excitation at 400 and 485 nm are given by the open and closed symbols, respectively. Data were included if they were well fitted by a Hill coefficient between 0.75 and 1.2, if the observed ΔF at 1,000 µM ligand reached >85% of the fitted ΔFmax, and if the curve-fitting algorithm provided error bounds of EC50 < 10%.

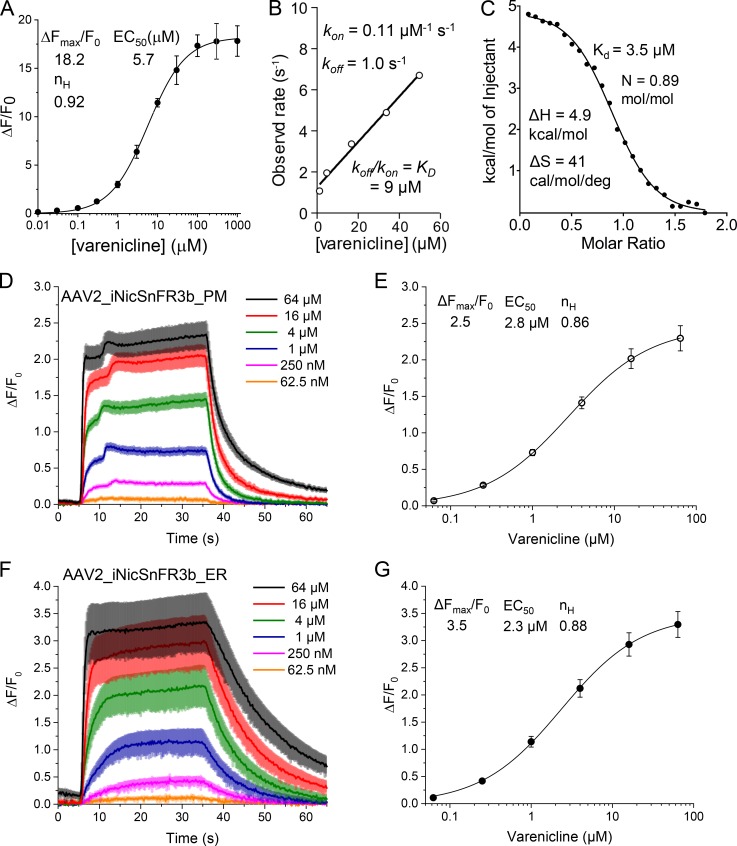

Figure 9.

Varenicline activity against purified iNicSnFR3a (A–C) and iNicSnFR3b expressed in hippocampal neurons (D–G). (A) Dose–response relations for varenicline-induced ΔF/F0, measured in 3× PBS, pH 7.4. Mean ± SEM; three measurements. (B) Stopped-flow measurements at various [varenicline]. (C) Isothermal titration calorimetry. (D–G) Exemplar varenicline-induced fluorescence increases for cultured hippocampal neurons transduced with AAV2/1.syn1.iNicSnFR3b_PM (D and E) or with AAV2/1.syn1.iNicSnFR3b_ER (F and G). (D and F) 30-s varenicline pulses, followed by 40-s wash in HBSS. The average waveform for five cells at each [varenicline] is overlaid for the PM and ER traces in A and C, respectively. The SEM is shown as colored bands around each line. (E and G) Dose–response relations, fitted to a single-component Hill equation, including zero response at zero [varenicline]. Parameters are shown.

Stopped-flow experiments were conducted on an Applied Photophysics SX-18MV instrument at 25°C. Equal volumes of iNicSnFR3a solution (100 nM) and ligand solution in PBS were mixed, yielding the final nicotine and varenicline concentrations given in Fig. 2 D and Fig. 9 B, respectively. The samples were excited at 470 nm via a monochromator (9.3 nm slit width), and the emission was collected at 520 nm using a 10-nm band-pass filter. Waveforms were fitted to single exponential waveforms, using Applied Photophysics software.

Expression in mammalian cells

We constructed two variants of the iNicSnFR biosensors for expression in mammalian cells. The constructs were cloned into vectors designed for expression either on the PM (iNicSnFR_PM) or in the ER (iNicSnFR_ER). For iNicSnFR3a_PM and iNicSnFR3b_PM, we cloned the bacterial constructs into pCMV(MinDis), a variant of pDisplay (Invitrogen) lacking the hemagglutinin tag (Marvin et al., 2013). To generate iNicSnFR3a_ER and iNicSnFR3b_ER, we replaced the 14 C-terminal amino acids (QVDEQKLISEEDLN, including the Myc tag; Fig. S1, final line) with an ER-retention motif, QTAEKDEL.

We conducted cDNA transfection experiments on iNiCSnFR3a_PM and iNicSnFR3a_ER expressed in HeLa cells, in SH-SY5Y cell, in HEK293 cells, and in N2a cells. All cell lines were purchased from ATCC and cultured according to ATCC protocols. Chemical transfection was achieved by combining 0.5 or 1 µg of plasmid with 1 µl of Lipofectamine 2000 (1 mg/ml; Invitrogen) in 500 µl OptiMEM (Gibco), incubating at room temperature for 30 min, and adding to dishes with fresh OptiMEM. Cells were incubated in the transfection medium for 24 h and then in growth media for ∼24 h before imaging.

For experiments on cultured mouse hippocampal neurons, an effective expression procedure used adeno-associated viral (AAV2) constructs. As stated in Results, iNicSnFR3a and iNicSnFR3b gave identical ΔF in solution experiments and in transfection experiments. After we obtained preliminary data with AAV2/1 constructs for iNiCSnFR3b with a synapsin promoter (in this paper, usually abbreviated AAV2_iNicSnFR3b_PM and AAV2_iNicSnFR3b_ER); we therefore judged that it was an unnecessary expense to generate the analogous iNicSnFR3a AAV constructs. The cells were grown on circular coverslips (1 cm diameter) glued to the bottom of 35-mm culture dishes (MatTek).

GFP immunoblot quantitation of biosensor levels

Transfected HeLa cells were lysed using 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, and 2% Triton X-100, pH 7.4 with 40 strokes of a disposable polypropylene pestle and incubated for 3 h at 4°C with agitation to solubilize membrane-bound proteins. The membrane fraction was pelleted via centrifugation (21,130 g for 10 min at 4°C) and the supernatant containing the protein fraction was isolated. Isolated proteins were incubated at 95°C for 5 min in 1× Laemmli sample buffer and 355 nM β-mercaptoethanol (BioRad). The pH of each sample was adjusted with 1 M Tris base and then alkylated using 100 mM iodoacetamide at 20–25°C for 1 h in the dark. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using a 6–18% bis-Tris gel and transferred to Immun-Blot low fluorescence polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (BioRad). Membranes were blocked using Odyssey Tris-buffered saline (TBS; Li-Cor) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with mouse anti-GFP antibodies (2955S; Cell Signaling), diluted 1:1,000 in Odyssey TBS-blocking buffer, supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20 (“antibody buffer”) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with anti-mouse secondary antibodies (925-32212; Li-Cor) diluted 1:10,000 in antibody buffer. The blot was washed and visualized using an Odyssey scanner (Li-Cor). Anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibodies (1:1,000 in antibody buffer; Ab9483; Abcam) were used as a loading control. GAPDH immunoreactivity was visualized with anti-goat secondary antibodies (1:10,000; 926-68074; Li-Cor). Anti-GAPDH primary and secondary antibodies were added concurrently with anti-GFP primary and secondary antibodies. To quantify biosensor levels, a standard curve of purified soluble iNicSnFR3b protein (0.23, 1.15, and 5.76 ng protein, in duplicate) was used in each blot. Data were analyzed using Odyssey application software (version 3.0; Li-Cor).

Preparation and transduction of hippocampal neurons

A pregnant mouse was euthanized at embryonic day 16. The pups were removed from the uterine sac and decapitated before dissection. The hippocampi from several pups were combined and digested in 50 units of papain for 15 min. After DNase treatment, cells were triturated in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; ThermoFisher; GIBCO) with 5% equine serum and spun down through a 4% BSA solution. The pellet was resuspended in plating medium, and the cells were plated onto glass bottom 35-mm imaging dishes (MatTek) coated with poly-d-lysine, poly-l-ornithine, and laminin. After 1 h, the cells were flooded with 3 ml of culture medium, and half of the culture medium was changed every 3 d. At 3 d in vitro, the cells were infected with AAV2_iNicSnFR3b_PM or AAV2_iNicSnFR3b_ER at a multiplicity of infection of 100,000 or 50,000, respectively.

Expression in dopaminergic neurons differentiated from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)

Fujifilm CDI (formerly named Cellular Dynamics International; CDI) furnished iCell DopaNeurons. These are human dopaminergic neurons differentiated from iPSCs. The supplier has measured that 89% of the cells are positive for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. The iCell DopaNeurons were maintained in 95% BrainPhys Neuronal medium (StemCell Technologies), 2% iCell Neural Supplement B (CDI), 1% iCell Nervous System Supplement (CDI), 0.1% of 1 mg/ml laminin (Sigma), and 1% N-2 Supplement 100× (ThermoFisher) and supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin. iCell DopaNeurons were maintained on dishes for 17–24 d before imaging. Glass bottoms of the 35-mm imaging dishes (MatTek) were coated with ∼0.07% poly(ethyleneimine) solution and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Dishes were rinsed with PBS, then rinsed with water and air dried overnight. Glass bottoms were then coated with 80 µg/ml laminin solution for 30 min at 37°C before cells were plated. We confirmed that ≥40% of the cells stained for TH by immunocytochemistry using a previously described assay (Srinivasan et al., 2016).

iCell DopaNeurons were transfected after either 13 or 21 d in culture using the Viafect kit (E4981; Promega) at 4:1 transfection reagent (µl) to DNA (μg) ratio. The transfection mixture was prepared in 100 µl OptiMEM (ThermoFisher), containing 4 μL of Viafect transfection reagent and 1 μg of either iNicSnFr3a_ER or iNicSnFr3b_PM cDNA. The mixture was incubated for 10–15 min and then added directly to fresh maintenance medium in the culture dish. Transfection medium was removed after 24 h, and cells were incubated for 48–72 h further before imaging.

iCell DopaNeurons were transduced with AAV2_iNicSnFr3b_ER virus particles after 7 d in culture. 1 µl of the stock (2 × 1012 genome copies/ml) was mixed with 100 µl of maintenance medium, and then the mixture was added to 2 ml of maintenance medium in the culture dish. Cells were studied after 24 d in culture.

Time-resolved fluorescence measurements in live mammalian cells

Experiments have been conducted at room temperature with four inverted microscope systems; each produced useful fluorescence increases when nicotine or varenicline was perfused into the chamber. Early experiments used a Zeiss 510 spectrally resolved laser-scanning confocal microscope, previously used for other biosensors that use cpGFP moieties. This group includes the GCaMP sensors and iGluSnFR (Marvin et al., 2013). We find that signals with the iNiCSnFR constructs have brightness and dynamic range similar to those of the previous cpGFP-based biosensors.

Most datasets were taken on an Olympus IX-81 microscope, in wide-field epifluorescence mode. Images were acquired at 3–4 fps with a back-illuminated EM charge-coupled device camera (iXon DU-897; Andor Technology; Pantoja et al., 2009), controlled by Andor IQ2 software. Initial experiments used excitation by the 488-nm line of an argon laser (IMA101040ALS; Melles Griot; Richards et al., 2011); however, this produced speckles and also excessive bleaching when the iNicSnFR was activated by ligands (Fig. S3). Therefore, we installed a considerably weaker incoherent light source: a light-emitting diode (LED). Although a peak at ∼485 nm would have been optimal, the closest available LED had peak emission at 470 nm (LZ1-10DB00; Led Engin). We used a 40-nm band-pass filter, centered at 470 nm (ET 470/40X; Chroma Technology), at currents of 40–800 mA. The epifluorescence cube was previously described (Srinivasan et al., 2011). We obtained useful signals with 20× (numerical aperture [NA] 0.4), 40× (NA 1.0; oil), 63×, and 100× (NA 1.45) lenses. The 40× lens proved most convenient for imaging several adjacent cells and was relatively insensitive to modest drift of the focus. For HeLa cells, the PM-directed constructs were measured with a region of interest (ROI) that included only the cell periphery.

Solutions were delivered from elevated reservoirs by gravity flow, through solenoid valves (Automate Scientific), then through tubing fed into a manifold at a rate of 1–2 ml/min. Experiments were performed with HBSS buffer, except that iPSC-derived neurons were studied in PBS plus d-glucose (5.56 mM), MgCl2 (0.49 mM), MgSO4 (0.4 mM), KCl (5.33 mM), and CaCl2 (1.26 mM). The most robust datasets were taken with gas-impermeable fluorinated ethylene propylene-lined Versilon tubing. This minimized loss of CO2, which in turn would produce transient pH increases that artifactually increased biosensor fluorescence in the absence of ligand (Fig. S5). Culture dishes were placed on a Warner Instruments SA-TS100 adapter that supported a DH-40i perfusion ring. With this arrangement, the stainless steel tubes for the inlet and aspiration were separated by 5 mm. Videos of dye solutions showed that local solution changes proceeded with a time constant of <1 s (California Institute of Technology “Katz” station). As usual in fluorescence imaging experiments, we excluded data from the brightest cells, because these may have fluorescent impurities or aggregates that produce a rapidly bleaching baseline (an example is the black trace in Fig. S5). Data analysis procedures included subtraction of blank (extracellular) areas and corrections for baseline drifts.

Experiments with micro-iontophoretic nicotine application (Fig. 7) used the following optical and electrophysiological instruments. A Nikon Diaphot 300 wide-field microscope was equipped with an Hg arc lamp (100 W), a 40× (NA 0.33) objective lens, and a fluorescein/GFP epifluorescence cube. Images were acquired with a Hamamatsu Orca 03G camera, controlled by Hamamatsu software. Iontophoretic pipettes were filled with 1 M nicotine HCl, had resistance of ∼50 MΩ and were mounted on a micromanipulator. Current was supplied by an Axon Instruments Geneclamp 500, commanded by Axon Instruments pCLAMP software (California Institute of Technology “Erlanger” station).

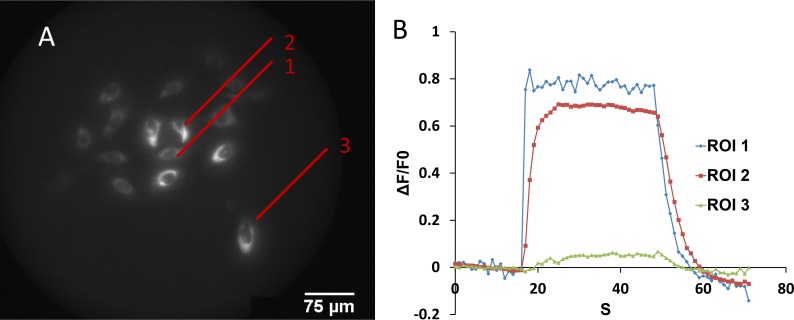

Figure 7.

Micro-iontophoretic nicotine application. (A) Cultured mouse hippocampal neurons transduced with AAV_iNicSnFR3b_ER. A nicotine-containing micro-iontophoretic pipette was positioned <10 µm above the cell in ROI 1. A 10-nA outward current pulse (32-s duration) was delivered. Most cells in the area showed fluorescence increases. (B) Fluorescence traces recorded simultaneously for cells at three distances from the pipette.

Structured illumination microscopy and confocal fluorescence images

Cells were cotransfected with cDNA for DsRed2-ER (Srinivasan et al., 2012) and with iNicSnFR3a_ER or iNicSnFR3a_PM (0.5 µg of each construct combined with 1 µl of Lipofectamine 2000 was added to the cells in OptiMEM and incubated for 24 h, followed by incubation in growth media for ∼24 h). The image in Fig. 4 C1 was acquired as Z stacks with a Zeiss ELYRA S.1 microscope, equipped with a 63× NA 1.4 objective lens. GFP illumination was at 488 nm, observed through a 495–550 nm band-pass + 750 nm long-pass filter. DsRed2-ER was illuminated at 561 nm and observed through a 570–620 band-pass + 750 long-pass filter. The structured illumination grating was rotated five times and processed using Zeiss ZEN software to produce the final image.

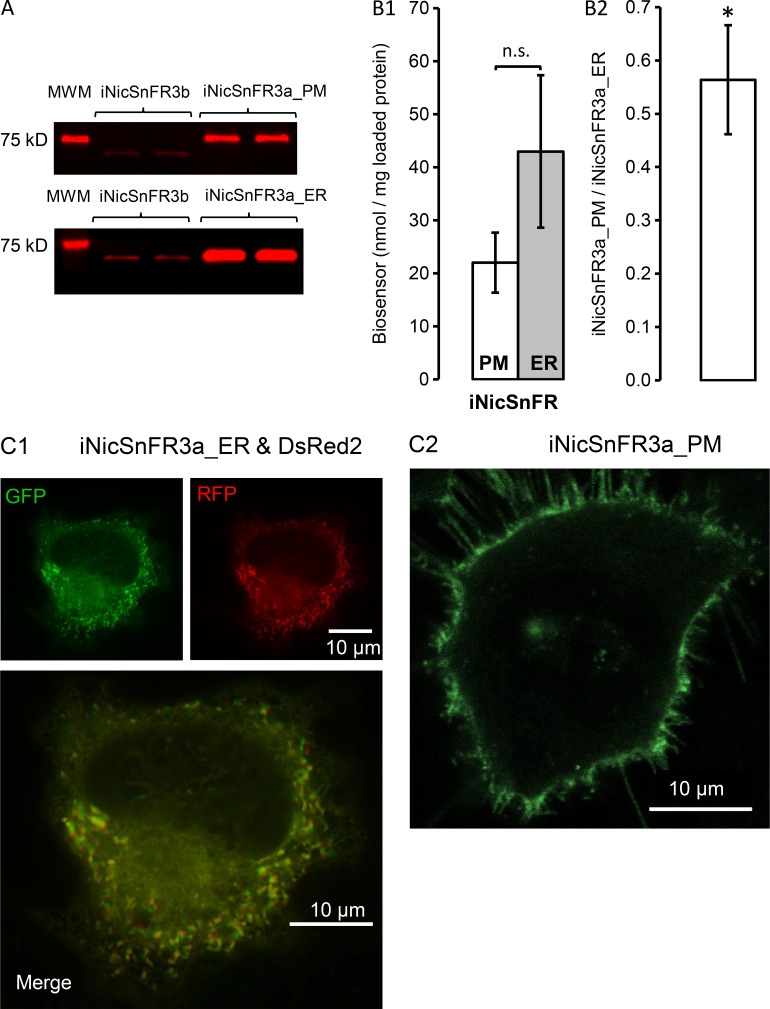

Figure 4.

Protein levels and subcellular imaging of iNicSnFR3a_PM and iNicSnFR3a_ER in HeLa cells. (A) Typical immunoblots with anti-GFP immunoreactivity to lysates (1 µg protein) from HeLa cells transfected with either iNicSnFR3a_PM (top) or iNicSnFR3a_ER (bottom). In each panel, the leftmost lane is the 75-kD molecular weight marker (MWM). The two middle lanes are duplicate samples of purified, diluted iNicSnFR3b (∼61 kD). The two rightmost lands are duplicate samples from the transfected cells. Bands for iNicSnFR3a_PM appear at ∼68 kD (slightly below the MWM), and bands for iNicSnFR3a_ER appear at ∼61 kD (markedly below the MWM and comparable with purified biosensor), confirming the predicted size difference of 7 kD between the two constructs. (B1) Absolute quantitation of iNicSnFR3a expression, based on GFP immunoblots, from five paired transfections, analyzed 7–23 h after transfection. Data are mean ± SEM (two duplicate lanes loaded with 1 µg protein per blot; one blot per transfection). Significance was determined using an unpaired Student’s t test. *, P ≤ 0.05; n.s., not significant. (B2) Ratio of iNicSnFR3a_PM to iNicSnFR3a_ER levels, within each set of transfections. The ratio varied from 0.40 to 0.95 with an average of 0.56 ± 0.10. The bar gives SEM. (C) Typical fluorescence microscopy images from cells cotransfected with iNicSnFR3a and with DsRed2-ER (red channel) and exposed to nicotine (15 µM). (C1) iNicSnFR3a_ER (green channel) and DsRed2-ER (red channel) and merged image. Structured illumination microscopy. (C2) iNicSnFR3a_PM (only the green channel is shown). Confocal microscopy.

The image in Fig. 4 C2 was acquired with a Zeiss LSM 710 laser-scanning confocal microscope, equipped with a 63× NA 1.4 objective lens. Neither microscope has a perfusion system; solutions were changed with a pipette. Nicotine (15 µM nicotine in HBSS) was used to wash and replace the growth medium in the dishes before imaging.

Reagents

(—)–Nicotine salts or free base (>98% purity) were obtained from several suppliers, with no detectable difference in properties. Samples of N’-methylnicotinium (N’MeNic; Fig. 1 C) were obtained from two sources, with no detectable difference in properties. A sample was synthesized by M.R. Post (California Institute of Technology), as described (Post et al., 2017), and purified by P.S. Lee (Janelia Research Campus). Other samples were purchased from Toronto Research ((S)-1’-methylnicotinium Iodide; M323280), and purity was verified by NMR by D.P. Walton (California Institute of Technology).

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic simulations

Simulations of nicotine and varenicline in human subjects were constructed and run in Matlab (2017a and later releases) using the SimBiology App. The detailed parameters of the simulation are given in Table S2. The code is available in SimBiology format (.sbproj, which presents the formatting of the diagrams in Fig. 8 A and Fig. 10 A, and in Systems Biology Markup Language [.xml]. See the ZIP file contained in the Supplemental material).

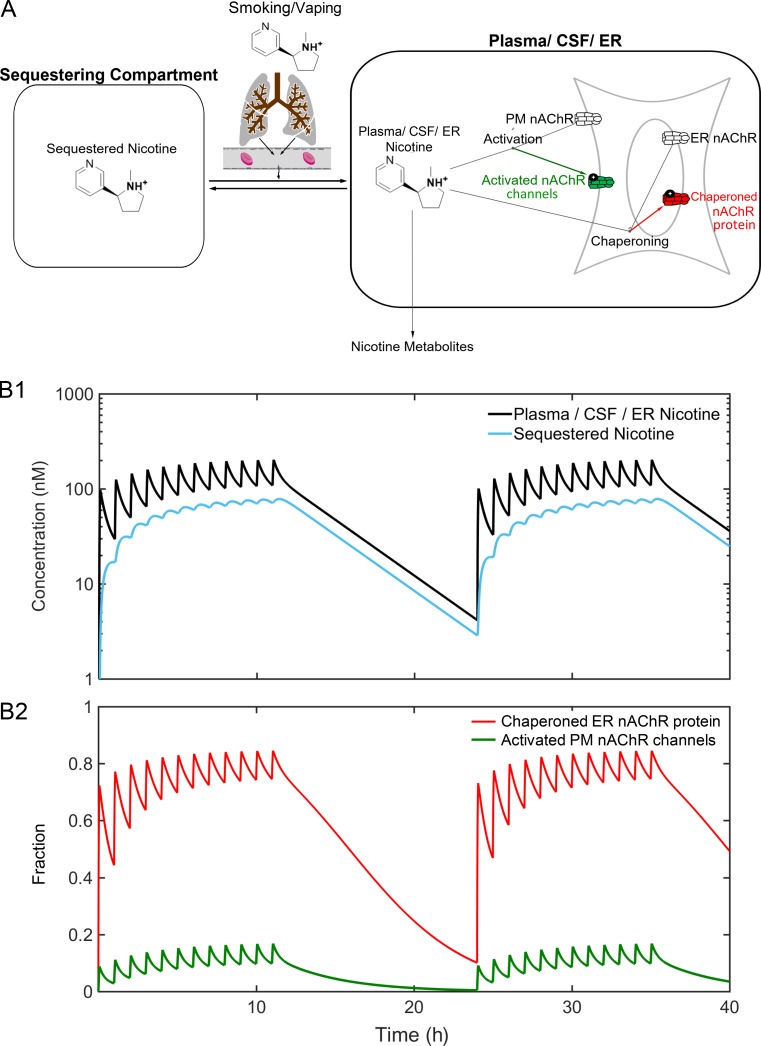

Figure 8.

Simulations of nicotine pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics during smoking. (A) The pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model, implemented in Matlab SimBiology. Individual parameters and structures and smoking dosages are presented in Table S2 and in Supplemental ZIP File. (B1) Nicotine concentrations in the plasma/CSF/ER and in the “sequestered” compartment, during 40 simulated hours for the standard habit (Table S2 and Supplemental ZIP File). The latter compartment was termed the “peripheral compartment” by Benowitz et al. (1991), but that terminology is less preferable in discussions of the nervous system. Note the logarithmic [nicotine] scale. (B2) Effects on the two processes shown in A. Note that the standard habit nearly activates nAChR protein chaperoning (inside-out process) >50%, but activates nAChR channel activation (outside-in process) <20%.

Figure 10.

Simulated pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics during oral varenicline administration. (A) In the pharmacokinetic model for orally administered varenicline, the lungs are replaced by the digestive tract. The parameters derive from studies on humans (Faessel et al., 2006). The parameters are given in Table S2 and in Supplemental ZIP File. (B1) Varenicline concentrations in two compartments: the plasma/CSF/ER and the sequestered compartment. (B2) Effects on the two processes shown in A. Note that recommended treatment with varenicline almost completely activates nAChR protein chaperoning (inside-out process), but only slightly produces nAChR channel activation (outside-in process).

Data analysis software

Image video files, spectral data, and dose–response data were analyzed further and presented with general purpose software. These programs include ImageJ, Excel (Microsoft), and Origin (OriginLab).

Online supplemental material

Online supplementary information includes text information that amine-containing buffers produce anomalous results and that acidic vesicles are candidates for the “sequestered compartment;” Table S1 shows steps in structure and refinement of iNicSnFR1 crystallized with nicotine; Table S2 shows parameters for nicotine and varenicline Matlab/SimBiology models; Fig. S1 shows sequences of PBPs and constructs described in this paper and/or studied in preliminary experiments; Fig. S2 shows directed evolution of the iNicSnFR family; Fig. S3 shows photoswitching noticeable at high [nicotine] with focused laser illumination; Fig. S4 shows responses to nicotine with iNicSnFR_ER in SH-SY5Y cells and HEK293 cells; Fig. S5 shows human iPSCs, differentiated to dopaminergic neurons, transduced with AAV_iNicSnFR3b_ER; and Fig. S6 shows varenicline at iNicSnFR3a expressed in HeLa cells. Additional online supplementary information includes a ZIP file containing Matlab SimBiology models for nicotine and varenicline in .sproj and Systems Biology Markup Language (.xml) format. Additional online supplementary files include a guide to the online videos, of which there are nine.

Results

Development and characterization of iNicSnFRs

We identified and optimized iNicSnFRs in parallel with the research program that produced the genetically encoded ACh biosensor molecule, iAChSnFR (Borden et al., in preparation). We had two goals for the optimized iNicSnFRs. (1) We sought ≥30% increase in fluorescence (ΔF/F0 ≥ 0.3) at [nicotine] = 1 µM, a concentration thought to lie at the upper end of the range of the peak [nicotine] in the plasma and brain of a smoker. (2) We sought to achieve this response with a time constant <1 s.

Many bacterial and archaeal species use the quaternary amines choline, glycine betaine, and proline betaine as osmolytes or energy sources. PBPs (also called substrate-binding proteins; SBPs) from some of these species bind these ligands, then present the ligands to transporters in the inner membrane. Structural studies of ligands bound to PBPs show a feature first noted by Schiefner et al. (2004a): a “box” of four aromatic side chains that participate in cation-π interaction(s) with the quaternary amine. This feature was previously noted for nAChRs (Zhong et al., 1998; Brejc et al., 2001; Morales-Perez et al., 2016). Furthermore, a cation-π box participates prominently in binding to other Cys-loop and G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) for other primary and secondary amine ligands including serotonin, GABA, glycine, and many drugs that mimic those transmitters (Van Arnam et al., 2013). We hypothesized that choline- and/or betaine-binding PBPs could be mutated by experimenters to bind ACh, nicotine, and perhaps other alkaloid (nitrogen containing, weakly basic) drugs. PBPs undergo substantial, well-characterized ligand-induced conformational changes upon binding their target ligand. In SnFRs, cpGFP is inserted into a PBP in such a way that this conformational change is allosterically transduced into rearrangements of the chromophore environment, leading to changes in fluorescence intensity, lifetime, etc. (Marvin et al., 2013). We reasoned that this strategy would work similarly well with PBPs mutated to bind exogenous molecules, so as to enable families of genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors for drugs (iDrugSnFRs).

In preliminary experiments, we synthesized the genes and expressed in bacteria PBPs of structural Class F (Berntsson et al., 2010), thought to bind choline and/or betaine. Studies included ChoX from Sinorhizobium meliloti (Oswald et al., 2008), ProX from Archaeoglobus fulgidus (Schiefner et al., 2004b), OpuAC from Lactococcus lactis (Wolters et al., 2010), OpuCC from Bacillus subtilis (Du et al., 2011), and OpuBC from Bacillus subtilis (Pittelkow et al., 2011). An OpuBC homologue (possibly a ProX homologue) from the hyperthermophilic bacterial species Thermoanaerobacter sp X513 appears in genomic databases, but was not previously characterized. We first performed isothermal titration calorimetry to detect any binding with the purified proteins. This paper presents experiments with the most promising PBP, the T. sp X513 OpuBC homologue; we found that betaine, choline, and ACh bind to this protein. We coupled it to cpGFP and optimized its sensitivity to nicotine, as described in Materials and methods and in Fig. 1 and Fig. S2.

We obtained an x-ray crystallographic structure of an early iNicSnFR, termed iNicSnFR1, in the presence of nicotine at 2.4 Å resolution (Fig. 2 A and Table S1, deposited as PDB file 6EFR). This construct has an apparent nicotine EC50 of 250 µM. This is, to date, the only iNicSnFR structure we have obtained in a liganded, closed (or partially closed) conformation. The structure, in common with several other OpuBC-related structures discussed above, reveals the ligand at the interface between two domains of the PBP moiety. Four aromatic side chains, contributed by both lobes, surround the pyrrolidine nitrogen. This resembles the “aromatic box” found in many PBPs that bind quaternary amines, as well as in nAChRs. We also obtained x-ray crystallographic structures of several other constructs in the iNicSnFR series; but in these, the upper domain of the PBP was flexed away from its position in Fig. 2 A, and there was no ligand present. Fig. 2 B presents our model of the ligand–protein interaction site of iNicSnFR3a and iNicSnFR3b.

During the development of iAChSnFR, for additional assurance that the ligand binds approximately as predicted in Fig. 2 B, we mutated several of the putative cation-π residues annotated as α through η noted in Fig. S1. The most dramatic elimination of sensitivity occurred at the γ aromatic residue, with the Y357A mutation. In Fig. 5 E, presented below, we show that incorporating the equivalent mutation into an iNicSnFR also eliminates nicotine sensitivity.

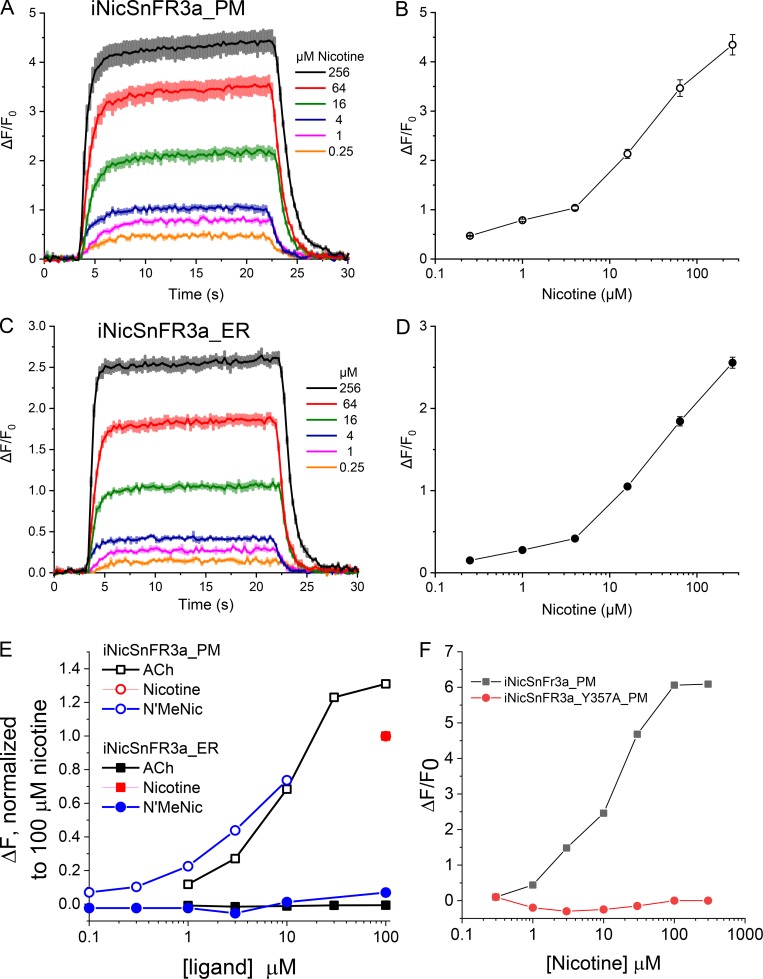

Figure 5.

Dose–response relations for nicotine-induced ΔF in HeLa cells. Exemplar data for iNicSnFR3a_PM and iNicSnFR3a_ER expressed in transfected HeLa cells. (A and C) 20-s nicotine dose application followed by 20-s wash in HBSS. The average response for three cells at each dose is overlaid in a 30-s window for the PM and ER traces in A and C, respectively. The SEM is shown as colored bands. (B and D) The averaged ΔF/F0 at each response in A and C, respectively, is plotted against the logarithmic concentration scale with SEM given as error bars. (E) Comparisons among nicotine itself, N’MeNic, and ACh; experiments in transfected HeLa cells. The iNicSnFR3a_PM responses to ACh and to N’MeNic were normalized to NicSnFR3a_PM responses for nicotine (100 µM). The iNicSnFR3b_ER responses to ACh and to N’MeNic were normalized to iNicSnFR3b_ER responses for nicotine (100 µM). Note that iNIcSnFR3a_PM responds robustly to all three ligands, but only iNicSnFR3b_ER responds robustly only to nicotine, the only permeant molecule among the three tested. (F) Mutating a probable cation-π interacting residue, Tyr357, eliminates nicotine-induced ΔF. Exemplar data from cells transfected in parallel and tested on the same day.

We used excitation near the absorption peak at 485 nm, and we made emission measurements at wavelengths >510 nm. Fig. 2 C shows dose–response relations for ΔF induced at iNicSnFR3a by three nicotinic agonists: nicotine, ACh, choline, and cotinine. The EC50 for choline is more than fourfold greater than for nicotine, showing a greater-than-desired sensitivity, but higher than the usual value for choline in brain (∼10 µM; Klein et al., 1992). The near-zero ΔF values for cotinine are too small for systematic study. The iNicSnFR3a and iNicSnFR3b proteins differ by one amino acid substitution at codon 11 (Asn vs. Glu, respectively; Fig. S1) and have no detectable photophysical differences.

The stopped-flow data (Fig. 2 D) show that the fluorescence increase reached steady-state with time constants extrapolating to a value of koff-ext = 2.0 s−1 at the lowest [nicotine]. This satisfied the criterion that the kinetics should be substantially complete within 1 s. In other experiments that diluted premixed solutions of 200 nM iNicSnFR3a plus nicotine into PBS, we measured modestly higher values of koff-dil = 3.3 ± 0.3 s−1. However, we consider koff-dil measurements less satisfactory because the resulting iNicSnFR3a concentrations were just 8 nM, producing small and noisy signals. The isothermal titration calorimetry data (Fig. 2 E) also show that nicotine binds to iNicSnFR3a (Kd = 10 ± 2.5 µM). Thus, all the available data indicate a noncooperative interaction between iNicSnFR3a and nicotine, with a Kd between 10 and 30 µM, that is complete within ∼1 s.

pH dependence of an iNicSnFR

We based additional photophysical studies on previous data with the GCaMP family. In the inactive conformation of cpGFP, the fluorophore has a pKa of 8–9. At neutral pH, the fluorophore is almost fully protonated, decreasing the absorption in the band centered at λex ∼485 nm (Barnett et al., 2017). In the active form, the pKa is ∼7, so that some of the fluorophore molecules are deprotonated. This allows absorption and fluorescence (Barnett et al., 2017). Our pH studies have the additional feature that nicotine itself is a weak base (Fig. 1, A and B), as are varenicline and many other neural drugs. One expects both the pH dependence of the biosensor, and that of the ligand, to affect measurements with iNicSnFRs. We also sought to determine whether the charged or the uncharged form of nicotine binds to the iNicSnFRs.

We investigated the pH dependence of both ligand-independent and ligand-induced fluorescence (F0 and ΔF, respectively, Fig. 3). Throughout the pH range from 5.5 to 9.0, excitation at λex = 400 nm produces detectable F0 at an λem of 535 nm, and this is nearly independent of pH (Fig. 3, A and B). This agrees with previous data on cpGFP-based biosensors (Barnett et al., 2017). The F0 values for λex = 485 nm show the expected, contrasting strong pH dependence (Barnett et al., 2017): F0 is approximately inversely proportional to [H+] (Fig. 3 C).

We determined the ΔF dose–response relations of iNicSnFR3a using excitation at λex = either 400 or 485 nm. At basic pH, we found the most reliable signals at λex= 485 nm, where nicotine induces increased fluorescence (ΔF > 0; Fig. 3 E). The ΔFmax decreases with increasing pH. Thus, ΔFmax/F0 at pH 7.5 is 14.5; but at pH 9.0, ΔFmax/F0 is only 3.5. This analysis is summarized by plotting both F0 and F0 + ΔFmax in the measured range (Fig. 3 G). The pH dependence of the F0 measurements is consistent with those measured more precisely in a spectrofluorometer (Fig. 3 C). The pH dependence of the fully saturated biosensor (F0 + ΔFmax) resembles that for the fully saturated GCaMP sensors (Barnett et al., 2017), reaching a plateau under basic conditions; however, the apparent pKa of iNicSnFR3a may be shifted to the right by ∼0.5 pH units from that for GCaMP6m (Barnett et al., 2017).

At acidic conditions for λex = 485 nm, nicotine evokes little or no ΔF; we therefore excited at λex = 400 nm and measured the nicotine-induced fluorescence decrease (ΔF < 0; Fig. 3 H). At pH = 7.5 and 8.0, where the two measurement modes both have adequate signals, the two modes yield good agreement in EC50 values (Fig. 3 I), consistent with the idea that the two modes are measuring the same nicotine-iNicSnFR binding. Nicotine exhibits a ∼20-fold decrease in EC50 as the pH is increased from 6.0 to 9.0 (Fig. 3 I). Both this pH dependence of the response to nicotine and the large pH dependence of F0 are complicating factors in our live-cell experiments.

A special environment in the iNicSnFR3-binding site

The nicotine derivative N’MeNic (Fig. 1 C) has a quaternary ammonium moiety at the pyrrolidine (N’) nitrogen. Like nAChRs (Beene et al., 2002; Post et al., 2017), iNicSnFR3 responds robustly to N’MeNic. Comparing N’MeNic-induced with nicotine-induced ΔF over a pH range is expected to reveal further mechanistic details about the ligand–protein interaction, independent of the pH dependence of other regions and/or transitions of the biosensor protein. We consider that systematic errors render the data most reliable for λex = 400 nm at pH ≤ 7.5, and for λex = 485 nm at pH ≥ 7.5. Fig. 3 (E–G) show that iNiCSnFR3a responds similarly to nicotine and to N’MeNic, with respect both to EC50 and to ΔFmax/F0, at basic pH. Fig. 3 G shows that the fully liganded state has a similar pH dependence whether the ligand is nicotine or N’MeNic. We found a similar trend under acidic conditions. Fig. 3 I shows that, over almost the entire measurable range from pH 6.0 to 9.0, the EC50 value for nicotine is 1.25- to 2-fold higher than that for N’MeNic. The modestly higher sensitivity to N’MeNic is not surprising, considering that the natural ligand of OpuBC is either choline or betaine, both quaternary compounds. Many nicotine-binding sites, such as those in AChBP and nicotinic receptors, tolerate the differences in charge density among protonated secondary amines (such as cytisine and varenicline), protonated tertiary amines (such as nicotine and ABT-418), and quaternary amines (such as choline and N’MeNic; Daly, 2005; Van Arnam and Dougherty, 2014).

How do we explain that the EC50 for nicotine remains a small multiple of the N’MeNic EC50 over nearly the entire measurable pH range, even though the concentration of protonated nicotine in free solution decreases for pH values above its pKa (7.5–8)? In a straightforward explanation, the binding site of iNicSnFR3, probably including a cation-π box, stabilizes diffuse positive charges such as those in quaternary amines and in protonated tertiary amines. Previous pH dependence studies of nAChRs show this phenomenon (Petersson et al., 2002). Regardless of the underlying mechanism, the data suggest that the pH dependence of the cpGFP moiety exerts a stronger effect than the pH dependence of the weakly basic ligand, nicotine.

Studies with nicotine in live cells

iNicSnFR3a_PM and iNiCSnFR3a_ER in HeLa cells

We conducted many of our optical and biochemical experiments in HeLa cells, which have a relatively large, flat appearance and prominent ER. Fig. 4 (A and B) shows protein expression of iNicSnFR3a_PM and iNiCSnFR3a_ER after transfection in HeLa cells. We performed immunoblotting using an anti-GFP antibody. Observed GFP immunoreactivity for proteins from iNicSnFR3a_PM- and iNiCSnFR3a_ER-transfected cells appears near the predicted values of ∼68 and ∼61 kD, respectively. Importantly, immunoblots demonstrated that the PM targeted biosensor is larger than the ER targeted biosensor, accounted for by the addition of the PM targeting sequence. We found no other bands with GFP immunoreactivity. In experiments conducted at 7–23 h post-transfection, we found that iNicSnFR3a_PM produced lower levels of protein than iNicSnFR3a_ER (22 ± 6 nM/mg protein compared with 43 ± 14 nM/mg protein, respectively). This expression level difference was not significant when we averaged absolute protein levels across the entire dataset (Fig. 4 B1), but was consistent and significant when assessed within each paired (same day) set of transfections (Fig. 4 B2). No detectable dependence on the time since transfection was observed.

We also imaged the transfected cells with higher-resolution fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4 C). We cotransfected some of these samples with DsRed2-ER to assess localization with the ER. As expected from the included targeted sequences, the iNiCSnFR3a_ER construct showed the expected ER structures typical of HeLa cells, and also colocalized well with DsRed2-ER (Fig. 4 C1). The iNiCSnFR3a_PM fluorescence was most intense at the periphery of the cell, as expected for a PM protein (Fig. 4 C2).

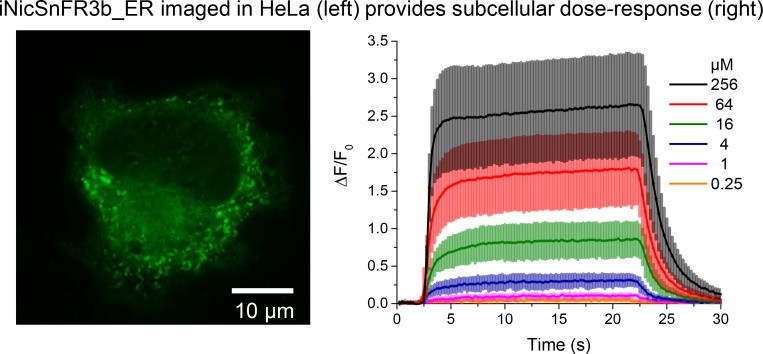

Fig. 5 presents a typical time-resolved fluorescence experiment, ∼24 h after transfection. For reasons reported in Section 1 above, the time-resolved imaging experiments were performed with illumination near the 485 nm absorption peak (see Materials and methods). Images were gathered at 4 Hz while cells were exposed to 20-s pulses of nicotine at 40-s intervals at fourfold concentration increments between 0.25 and 256 µM. Nicotine-induced fluorescence increases are well resolved, even at 0.25 µM. We note good reproducibility among cells: the coefficient of variation of ΔF/F0 < 10% within an experiment. Within a few seconds after the nicotine pulse begins in the extracellular solution, nicotine-induced fluorescence reaches an approximate plateau and changes by <10% over the next 20 s (the small increase in Fig. 5 was observed in only some experiments). Within a few seconds after [nicotine] is stepped to zero in the external solution, ΔF returns to zero. The temporal resolution of these experiments is limited by the speed of the solution change; we detected no difference between the iNicSnFR3a_PM and iNicSnFR3a_ER waveforms.

Fig. 5 exemplifies an idiosyncrasy of the HeLa cell nicotine-induced fluorescence increases. The dose–response relation at the higher [nicotine] shows less saturation than expected from experiments on purified iNicSnFR3a (Fig. 2 C and Fig. 3 E). We devoted little attention to this phenomenon, because [nicotine] never exceeds ∼10 µM during smoking or vaping.

iNicSnFR3_ER detects only membrane-permeant molecules

A key goal for our experiments is to distinguish ER nicotine ligands from extracellular molecules. Therefore we compared responses to nicotine itself versus two quaternary amines, thought to be membrane-impermeant molecules: N’MeNic and ACh (Fig. 5 E). In cells transfected with iNicSnFR3a_PM, we found comparable fluorescence increases among the three ligands. In contrast, for cells transfected with iNicSnFR3a_ER, only nicotine evoked fluorescence increases. In solution, iNicSnFR3a has comparable ΔF to nicotine, N’MeNic, and ACh (Fig. 2 C and Fig. 3, E and F). Therefore it may be concluded that iNicSnFR3a_ER samples only intracellular molecules. Given the predominant ER localization of iNicSnFR3a_ER (Fig. 4 C1), it may be concluded that this biosensor measures primarily ligands in the ER. We provide, in the section “Studies with varenicline in vitro and in live cells” of this paper, evidence that iNicSnFR3a_ER responds strongly to varenicline, an additional membrane-permeant ligand.

The data of Fig. 5, by themselves, cannot rule out the possibility that iNicSnFR3a_PM samples some intracellular nicotine. We argue against this possibility by noting the images of Fig. 4 C2, showing that iNicSnFR3a_PM fluorescence occurs only on the periphery of the cell. To investigate further, we conducted nicotine exposure experiments on iNicSnFR3a_PM with a 100× objective lens, and we chose ROIs including only the periphery. We found that ΔF/F0 measurements had comparable values to those of ROIs that include the entire cell (data not shown). One objection to these “periphery-only” experiments is that some iNicSnFR3a_PM might remain within endosomes that cannot be distinguished from the PM by light microscopy, as found for some transporters (Chiu et al., 2002; Moss et al., 2009). However such compartments have luminal pH values ∼5.5, and intraluminal cpGFP would fail to fluoresce. In summary, there is good evidence that iNicSnFR3a_PM and iNicSnFR3a_ER measure the nicotine concentration in the extracellular solution and in the ER, respectively.

Transfection of iNicSnFR3a_PM and iNicSnFR3a_ER into two other human clonal cell types, SH-SY5Y (Fig. S4 A) and HEK293 (Fig. S4 B) produced similar ΔF values in response to nicotine perfusion. We also obtained preliminary data in the only mouse cell line tested, N2a (data not shown).

We also tested whether eliminating a crucial cation-π interaction, at the γ amino acid (Fig. S1), eliminates nicotine-induced ΔF. In experiments on purified iAChSnFR, we found that the F357A mutation abolished sensitivity to ACh. In the present experiments, the equivalent mutation, iNiSnFR3a_Y357A_PM, was constructed and tested in HeLa cells. We found no detectable nicotine-induced ΔF at concentrations ≤300 µM (Fig. 5 F). This observation also provides assurance that the nicotine-induced ΔF has little or no nonselective component.

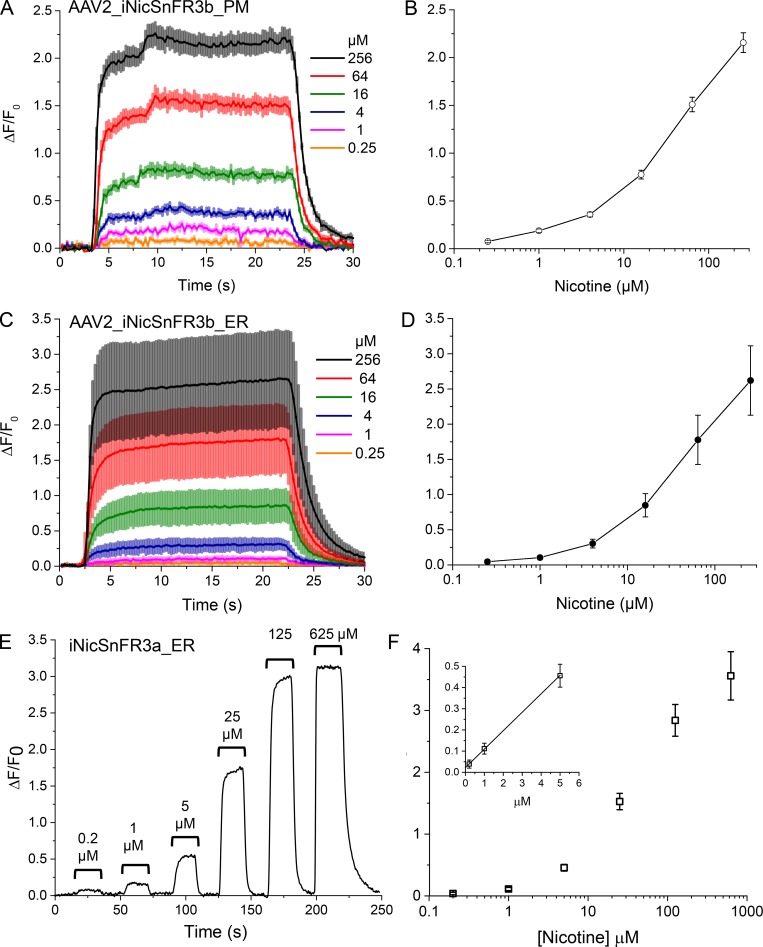

Nicotine enters the ER of neurons

Fig. 6 analyzes fluorescence induced by nicotine at two variants of iNicSnFR3 expressed in neurons. An AAV2 construct yielded basal fluorescence in >50% of cultured mouse hippocampal neurons, and each fluorescent cell also showed responses to nicotine within a few seconds after an increase or decrease of extracellular nicotine. Interestingly, neurons yield roughly the same ΔF/F0 values for iNicSnFR3b_PM and iNicSnFR3b_ER. A similar pattern of roughly equal nicotine-induced ΔF/F0 in neurons was observed for cDNA transfection, with iNicSnFR3a_PM and iNicSnFR3a_ER. As usual for neuronal cultures, cDNA transfection led to sparser expression (<10% of cells) than viral transduction.

Figure 6.

Nicotine in the ER of neurons. (A–D) Exemplar nicotine-induced fluorescence increases for cultured hippocampal neurons transduced with AAV2/1.sin1.iNicSnFR3b_PM (A and B) or with AAV2.sin1.iNicSnFR3b_ER (C and D). (A and C) 20-s nicotine pulses, followed by 20-s wash in HBSS. The average waveform for five cells at each [nicotine] is overlaid for the PM and ER traces in A and C, respectively. The SEM is shown as colored bands around each line. Dose–response relations are shown in B and D. (E and F) Human dopaminergic neurons transfected with iNicSnFR_ER3a. (E) Typical nicotine-induced fluorescence during 20-s pulses of nicotine at the indicated concentrations. Data were subjected to a triangle filter (half-time, 1 s). (F) Full dose–response data from 20 transfected human dopaminergic neurons. Inset, start of the dose relation at [nicotine] ≤ 5 µM. The slope of the line, [ΔF/F0]/[nicotine], is 0.087 µM−1.

Dopaminergic neurons of the reward pathway located in the ventral tegmental area play a role(s) in nicotine addiction (Subramaniyan and Dani, 2015). Studies also suggest that nicotine protects dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta during the initial stages of Parkinson’s disease, via an inside-out pathway (Srinivasan et al., 2014, 2016; Henderson et al., 2016). Therefore, we assessed the entry of nicotine into the ER of human dopaminergic neurons differentiated from iPSCs.

It is not yet routinely possible to specifically induce either ventral tegmental area–like or substantia nigra pars compacta–like dopaminergic neurons from iPSCs; therefore, we recorded fluorescence from all neurons expressing iNicSnFR3a_ER (Fig. 6, E and F). The data show recordings resembling those recorded from other cell types. The fluorescence reaches steady-state within a few seconds after nicotine appears near the cells and decays to F0 within a few seconds after removal. The ΔF/F0 values reach a maximum of 3–4, and the [nicotine] giving half-ΔFmax/F0 is on the order of 20 µM.

We also found that viral transduction with AAV2-iNicSnFR3b_ER proceeded efficiently in the induced iPSC cultures (Fig. S5). >90% of the neurons were fluorescent, and all of these gave detectable increases in the presence of nicotine. The responses resembled those for transfected dopaminergic neurons but had lower ΔF/F0, rarely exceeding 2. In two cells, we found that ΔF induced by N’MeNic (100 µM) was <0.2 times as large as ΔF induced by 1 µM nicotine. This confirms that iNicSnFR3b_ER senses only intracellular nicotine, as found for expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 5).

[Nicotine] in the ER approximately equals [nicotine] at the PM

To assess the relationship between [nicotine] in the ER versus [nicotine] applied in the extracellular solution, we compared the increase of ΔF/F0 versus applied [nicotine], as measured by the _ER and _PM constructs. Two cell types (HeLa and hippocampal neurons) provided complete datasets with both _ER and _PM constructs (presented in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6, A–D). For this analysis, we accepted data for applied [nicotine] ≤ 5 µM, because this concentration range is most pharmacologically relevant, well below the EC50, and least subject to pH perturbation in the ER. The appropriate metric is defined as [ΔF/F0]/[nicotine] and has the units µM−1. For measurements with the _ER constructs and for the _PM constructs, the metric is 0.075 ± 0.019 µM−1 and 0.063 ± 0.13 µM−1, respectively (mean ± SEM, n = 8 cells in each case; Fig. 6 F inset, gives an exemplar plot). This similarity shows that [nicotine] in the ER is approximately equal to [nicotine] applied in the external solution. Less complete data show a similar pattern in other cell types: SH-SY5Y (Fig. S4 A), HEK293 (Fig. S4 B), and human dopaminergic neurons differentiated from iPSCs (Fig. 6, E and F; and Fig. S5).

For purposes of the simulations described in a later section, we assumed that [nicotine] is equal in the ER and in the extracellular solution. We interpret “approximately equal” as a difference of less-than twofold. The uncertainty arises primarily because of differences between the pH of the ER and extracellular solution. In most estimates, this difference is <0.2 pH units (Casey et al., 2010), but has not been measured for the cell types we investigated. As noted, it is unlikely that nicotine and varenicline at the sub-µM concentrations of most interest perturb the pH of the ER. Such perturbation (for instance, by mitochondrial uncouplers; Mitchell, 1966) requires that both the uncharged and charged form of the drug can permeate through membranes, either passively or via transporters(s). All previous studies on nicotine conclude that only the uncharged form is membrane-permeant (Lester et al., 2009).

Micro-iontophoresis of nicotine: membrane permeation does not slow fluorescence increases

Results presented above show that a “jump” of [nicotine] in the external solution results in ΔF in the ER. We asked whether the kinetics of ΔF reveal any delay due to diffusion of nicotine across either the PM or the ER membrane. To decide this point, we obtained more rapid application of nicotine without complications from solution changes or pH changes. We delivered nicotine from micro-iontophoretic pipettes (Del Castillo and Katz, 1955). The data (Fig. 7) show that, for a cell within 10 µm of the pipette tip, iNicSnFR3b_ER produces fluorescence increases within <1 s, approximately equal to the response time of the iNicSnFR itself (Fig. 2 D). This result shows that the PM and the ER membrane do not present a detectable diffusion barrier on this time scale. For more distant cells, the fluorescence increase is slower and smaller. For instance, the cell in ROI 3, ∼150 µm from the tip of the micro-iontophoretic pipette, responded completely on a time scale of ∼10 s. This is consistent with a diffusion constant on the order of 1 µm2/ms.

It is not possible to quantify the [nicotine] ejected from the tip of an iontophoretic pipette. We conducted dose–response studies by varying the iontophoretic current between 10 nA (as shown in Fig. 7) and 100 nA. As the current was increased, the ΔF/F0 for the cell in ROI 1 did not increase; the response in the cell of ROI 2 increased modestly and became faster, to equal the value in ROI 1. The cell in ROI 3 increased more gradually, eventually reaching ΔF/F0 ∼0.3 at an ejection current of 100 nA.

Simulations of the outside-in and inside-out pathways during smoking

Our data generate two insights important for understanding the inside-out pathway. First, the genetically encoded nicotine biosensors targeted to the ER reveal that nicotine appears in the ER within ≤10 s after it appears in the extracellular solution. The delay may be as small as 1 s, but this distinction has no importance for the simulations in this section. Second, after this delay, the [nicotine] in the ER differs by less than twofold from [nicotine] in the extracellular solution.

The most complete data on pharmacological chaperoning have used extracellular nicotine, applied for several hours (Kuryatov et al., 2005). Therefore, a major question arising from previous data were whether nicotine enters the ER quickly enough to serve as a pharmacological chaperone. The answer, based on our present data, is clearly, “yes.” It is reassuring, but not crucial, to know that [nicotine] in the ER is rather close to that outside the cell, so that the highest-affinity states of nicotine-nAChR binding, which leads to pharmacological chaperoning, need not differ drastically from events at the PM.

A question of particular interest now arises about the exit of nicotine from the ER. When nicotine is removed from the extracellular solution, nicotine leaves the ER, again within 10 s. If [nicotine] in the ER drops below the EC50 for pharmacological chaperoning during the interval between cigarettes, then the inside-out pathway cannot readily account for nicotine dependence. We term this point the “rapid exit” problem.

The rapid exit problem may be addressed by existing data on the pharmacokinetics of nicotine during smoking. After a person receives a bolus of nicotine from a cigarette or an ENDS, [nicotine] in the body decreases with two exponential terms. During the slower phase, measurable nicotine endures in the plasma for several hours (Benowitz et al., 1991). We simulated fractional activation of the inside-out and outside-in pathways using the available data from the literature (Benowitz et al., 1991; Kuryatov et al., 2005; Rollema et al., 2007). We assume a common pattern of smoking: one cigarette, yielding 1 mg of ingested nicotine, each hour, for 12 h during each day (Table 1). The detailed parameters of the simulation are given in Table S2.

Table 1. Effect of dosing regimen variations on simulated nicotine concentrations in plasma/CSF/ER and on nAChR activation or chaperoning.

| Nicotine dose (mg) per cigarette | Total daily cigarettes, intervals | Average [nicotine] in plasma/CSF/ER (nM) | Average nAChR activation on PM | Average activation of nAChR chaperoning in ER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12/d, 1 h | 112 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| 0.5 | 12/d, 1 h | 56 | 0.05 | 0.55 |

| 0.3 | 12/d, 1 h | 34 | 0.03 | 0.44 |

| 0.1 | 12/d, 1 h | 11 | 0.01 | 0.2 |

| 0.05 | 12/d, 1 h | 6 | 0.006 | 0.13 |

| 3 | 12/d, 1 h | 321 | 0.23 | 0.83 |

| 1 | 6/d, 2 h | 65 | 0.06 | 0.6 |

| 1 | 20/d, 0.8 h | 148* | 0.13* | 0.75* |

Results have been averaged over 12 or 16 h. Asterisk (*) denotes 16-h average. The first row (in bold) presents our definition of a standard habit, plotted in Fig. 8. The following five rows show simulations for increasingly “denicotinized” cigarettes. The row presenting a dose of 3 mg might be appropriate for a schizophrenic’s smoking strategy (Miwa et al., 2011).

The simulations show how plasma/cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)/ER nicotine concentration varies on the time scale of minutes to hours (Fig. 8 B1). Clearly, [nicotine] in the ER remains greater than the EC50 for pharmacological chaperoning during the entire 1-h interval between cigarettes. The inside-out pathway remains substantially activated continually during the 12–16 smoking-period hours of our simulations (Fig. 8 B2).

Studies with varenicline in vitro and in live cells

In addition to detecting nicotine, the biosensors iNicSnFR3a and iNicSnFR3b also detect varenicline (Fig. 9 and Fig. S6). In fluorescence data, purified iNicSnFR3a displays a varenicline EC50 approximately sixfold less than for nicotine. The maximal response, ΔFmax/F0, is at least equal to that for nicotine (Fig. 9 A). Note that the fitted Hill coefficient is significantly less than unity, as also noted for the live-cell imaging described below.

Biochemical characterization also indicates that varenicline binds more strongly than nicotine to iNicSnFR. The stopped-flow kinetics (Fig. 9 B) reveal smaller pseudo–first-order forward and reverse rate constants (kon and koff, respectively) than for nicotine (Fig. 2 D), as well as an inferred equilibrium binding constant Kd, approximately threefold less than for nicotine (compare with Fig. 2 D). The isothermal titration calorimetry data for the varenicline–iNicSnFR3a interaction (Fig. 9 C) also reveal a several-fold lower Kd (3.5 µM) than for nicotine.

Varenicline enters the ER

Live-cell imaging shows robust dose-dependent, varenicline-induced fluorescence increases, both in HeLa cells and in neurons, both at the PM and in the ER (Fig. 9 and Fig. S6). The pharmacologically relevant varenicline concentrations are <1 µM, a range that yields varenicline-induced ΔF. Unlike the data for nicotine, the varenicline dose–response data for both HeLa cells and neurons do approach saturation, allowing the conclusion that the dose–response relations show an EC50 of 1–4 µM. This agrees well with the data on purified biosensor protein.

Especially in neurons, the growth and decay phases of the ER varenicline-induced fluorescence (Fig. 9 F and Fig. S6 C) are clearly slower than either the nicotine responses presented earlier or the varenicline responses on the PM (Fig. 9 D and Fig. S6 A). The relatively slow ER varenicline responses occur even for the smallest measured [varenicline] (≤ 1 µM), which are unlikely to perturb organellar pH. The slower ER entry and exit for varenicline than for nicotine are consistent with the lower logD7.4 (−1.27 vs. −0.04; Smith et al., 2012), as though the ER entry/exit of varenicline is rate-limited by membrane permeability.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic simulations of varenicline

The data show that varenicline does enter the ER within <30 s after appearing near cells and that varenicline then leaves the ER within at most 60 s after leaving the external solution, at the clinically relevant sub-µM concentrations. These data are adequate to add a subcellular dimension to pharmacokinetic simulations for orally administered varenicline. We used a model appropriate to twice-daily oral administration and with parameters that account for the very different absorption and metabolism of varenicline (Fig. 10) versus nicotine (Fig. 8 and Table S2). The simulations show that the usual doses of varenicline only slightly activate the outside-in pathway of nAChR activation. In contrast, varenicline activates the inside-out pathway of pharmacological chaperoning by >50% after the second dose of varenicline and by >70% after the fifth dose.

Discussion

The study quantifies the dynamics and extent of an early step in the inside-out pathway for nicotine: entry into the ER. Downstream steps have been studied and quantified in several a previous report using biochemistry, fluorescence microscopy, genetically altered mice, and immunocytochemistry (Henderson and Lester, 2015).

Development of the iNicSnFR family begins the field of optical subcellular pharmacokinetics for nicotine. We present data that extend to the sub-µM nicotine concentration that exists in the plasma and CSF of a smoker or vaper. The genetically encoded nicotine biosensors iNicSnFR3a and -3b, trapped in the ER, reveal that nicotine appears in the ER within at most 10 s after it appears in the extracellular solution (Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. S4, and Fig. S5). The [nicotine] in the ER is equal to that in the extracellular solution, at a precision of twofold. These conclusions hold for each of the five cell types we have investigated: three types of human clonal cell lines (HeLa, Fig. 5; SH-SY5Y, Fig. S4 A; and HEK293, Fig. S4 B), human dopaminergic neurons differentiated from iPSCs (Fig. 6, E and F; and Fig. S5), and mouse hippocampal neurons (Fig. 6, A–D; and Fig. 7).

Fluorescent biosensors for optical subcellular pharmacokinetics

Our strategy (Fig. 1) extends that used for iGluSnFR (Marvin et al., 2013). No known natural PBP binds nicotine; therefore, we engineered a PBP to bind a drug. That NicSnFRs also recognize Ach, and more weakly, choline, is useful for studies of compartmentalization. Related OpuBC proteins, further optimized to sense ACh itself, will also find use in neuroscience (Borden et al., in preparation).

Although the directed evolution of the iNicSnFR family (Fig. S2) did not explicitly include assays for varenicline, varenicline is a highly potent full agonist for iNicSnFR3 fluorescence. Interestingly, varenicline is also more potent than ACh at both α4β2 and α7 nAChRs (Coe et al., 2005; Mihalak et al., 2006). However, varenicline is a full agonist at α7, but not at α4β2 nAChRs. Thus, there are differences in the details of the binding site of the iNicSnFR constructs versus nAChRs. We found that the iNicSnFR3a and iNicSnFR3b constructs are less sensitive to other α4β2 agonists: cytisine, dianicline, and A-85380 (unpublished data).

Other neuronal drugs may also operate via inside-out pathways (Jong et al., 2009; Lester et al., 2012, 2015). With further modifications to the ligand site, preliminary data show that it may be possible to develop families of biosensors for optical subcellular pharmacokinetics of several amine-containing drug classes (Muthusamy et al., 2018; Shivange et al., 2017. Annual Meeting of the Society of General Physiologists. Abstract no. 32. J. Gen. Physiol.). Values for logD7.4 of most neural drugs suggest that they enter organelles (Lester et al., 2012; Nickell et al., 2013; Jong et al., 2018), and melatonin probably also enters neutral organelles (Yu et al., 2016). The most important limitation, at present, is the extreme pH sensitivity of the biosensors. This constrains their usefulness in acidic organelles, where some neuronal drugs may also act (Stoeber et al., 2018).

Another class of fluorescent protein-based biosensors is derived from GPCRs rather than from PBPs (Jing et al., 2018; Patriarchi et al., 2018). In the GPCR-based biosensors, the ligand sites face the extracellular solution; they would presumably face the lumen of organelles like most (but not all) PBP-based SnFRs. However, in the GPCR-based biosensors, the fluorescent protein moiety faces the cytosol and therefore might be relatively insensitive to luminal pH. If GPCR-based biosensors can function in acidic organelles, they may also find use for subcellular pharmacokinetics.

Implications for the inside-out pathway

Our data show that when [nicotine] in the extracellular solution falls to zero, nicotine completely leaves the ER, again within 10 s. Yet after a person receives a bolus of nicotine from a cigarette, [nicotine] in the body does not immediately fall to zero. The rather leisurely metabolism of nicotine (half-time, ∼20 min in humans; Benowitz et al., 1991) provides that a smoker’s CSF [nicotine] decreases on the time scale shown in Fig. 8 B1. Because of the highly nicotine-sensitive feature of pharmacological chaperoning, [nicotine] in the ER remains greater than the EC50 for pharmacological chaperoning during the entire 0.75–1-h interval between cigarettes. The inside-out pathway remains >50%-activated continually during the 12–16 h of our simulations (Fig. 8 B2). We conclude that the inside-out pathway, operating via pharmacological chaperoning, can readily account for up-regulation, an important component of nicotine dependence.

Our simulations also lead one to reexamine the relationship between the previously distinct concepts of “acute,” “repeated,” and “chronic” exposure to nicotine. In the “standard habit,” even a single cigarette, whose nicotine is fully ingested during 10 min, activates the inside-out pathway >50% until the next cigarette 1 h later (Fig. 8). Thus, a series of “acute” and “repeated” exposures, one per hour for 12 h, becomes “chronic” activation for the 12 h of smoking activity. By the next morning, nicotine levels have decreased below levels that activate pharmacological chaperoning; but the downstream trafficking and subsequent sequelae, including nAChR up-regulation, probably endure for several days (Marks et al., 1985).

Thus, subcellular pharmacokinetics readily explains dependence on smoked nicotine. Around the world at any time, several 100 million people have ingested tobacco within the past hour; they retain nicotine in every organelle of every cell. In the ER and cis-Golgi of the small percentage of cells that contain α4β2 nAChRs, these levels activate the inside-out pathway >50%, and therefore maintain one aspect of nicotine dependence.

Recently introduced ENDSs provide plasma levels with kinetics approaching those of cigarettes (Bowen and Xing, 2015). Thus, ENDSs can also maintain a key molecular/cellular basis of nicotine dependence: the inside-pathway at α4β2 nAChRs.

Can outside-in mechanisms, such as channel activation and Ca2+ influx, also account for cellular/molecular aspects of nicotine dependence? In contrast to pharmacological chaperoning, nAChR channels do not remain fully activated during the average smoker’s day; in fact, the average activation of PM nAChR channels is <20% (Fig. 8 B2). Some explanations of nicotine dependence assume that Ca2+ influx, either directly through nAChRs or indirectly through neuronal activity-induced Ca2+ channel influx, can account for nicotine addiction, even considering the rather modest level of nAChR channel activation shown by our simulations. Yet the rather general phenomenon of Ca2+ influx has not been shown to account for the highly specific aspects of nicotine addiction, such as post-translational nAChR up-regulation. Another frequently invoked explanation for nicotine dependence is desensitization of nAChR channels in response to the presence of nicotine. It is highly likely that some acute aspects of nicotine exposure arise from desensitization rather than activation (Miwa et al., 2011). However, no available data suggest that desensitized nAChRs begin an intracellular signaling pathway that could account for nicotine dependence.