Little is known about how CFTR, the Cl− channel that is mutated in cystic fibrosis, interacts with lipids. Abu-Arish et al. show that agents that stimulate salt and fluid secretion reduce CFTR lateral mobility and promote its clustering into ceramide-rich platforms, thereby increasing its surface expression.

Abstract

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is a tightly regulated anion channel that mediates secretion by epithelia and is mutated in the disease cystic fibrosis. CFTR forms macromolecular complexes with many proteins; however, little is known regarding its associations with membrane lipids or the regulation of its distribution and mobility at the cell surface. We report here that secretagogues (agonists that stimulate secretion) such as the peptide hormone vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and muscarinic agonist carbachol increase CFTR aggregation into cholesterol-dependent clusters, reduce CFTR lateral mobility within and between membrane microdomains, and trigger the fusion of clusters into large (3.0 µm2) ceramide-rich platforms. CFTR clusters are closely associated with motile cilia and with the enzyme acid sphingomyelinase (ASMase) that is constitutively bound on the cell surface. Platform induction is prevented by pretreating cells with cholesterol oxidase to disrupt lipid rafts or by exposure to the ASMase functional inhibitor amitriptyline or the membrane-impermeant reducing agent 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate. Platforms are reversible, and their induction does not lead to an increase in apoptosis; however, blocking platform formation does prevent the increase in CFTR surface expression that normally occurs during VIP stimulation. These results demonstrate that CFTR is colocalized with motile cilia and reveal surprisingly robust regulation of CFTR distribution and lateral mobility, most likely through autocrine redox activation of extracellular ASMase. Formation of ceramide-rich platforms containing CFTR enhances transepithelial secretion and likely has other functions related to inflammation and mucosal immunity.

Introduction

The CFTR (ABCC7) is an anion channel expressed in the plasma membrane of many cell types throughout the body (Riordan, 2008). In airway epithelia, it mediates the apical Cl− efflux that helps drive fluid secretion into the airways to humidify inspired air and enable the mucociliary transport of inhaled particles and bacteria from the lung (Frizzell and Hanrahan, 2012). Mutations in the cftr gene cause the autosomal recessive disease cystic fibrosis (CF), which is characterized by abnormal fluid and electrolyte transport and sticky, viscous mucus in the airways, pancreas, and other organs. Abnormal salt and fluid transport in CF airways leads to recurring bacterial infections, chronic inflammation, and a gradual decline in lung function (Ratjen et al., 2015). CFTR channel activity and transepithelial secretion are stimulated by various peptide hormones and neurotransmitters called secretagogues. Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) is a 28–amino acid neuropeptide released by nonadrenergic, noncholinergic neurons that innervate the airways (Wine, 2007), and also by immune cells (Martinez et al., 1999). Upon release, VIP binds to the G protein–coupled receptors VPAC1 and VPAC2 (vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor types 1 and 2, respectively) on airway epithelial cells (Groneberg et al., 2001; Dérand et al., 2004; Miotto et al., 2004), leading to activation of PKA and PKC signaling and stimulation of CFTR-mediated secretion (Schwartz et al., 1974; Dharmsathaphorn et al., 1985). In addition to canonical VIP signaling, CFTR can also be activated by other secretagogues such as the muscarinic agonist carbachol (CCh), which stimulates phospholipase C, Ca2+ mobilization, and Src tyrosine kinase regulation (Billet and Hanrahan, 2013; Billet et al., 2013).

CFTR is usually viewed as a single, homogeneous population at the cell surface, although it is known that some CFTR channels reside in a detergent-resistant membrane (DRM) fraction (Kowalski and Pier, 2004; Wang et al., 2008) and that this population is increased by the cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (Dudez et al., 2008). We identified two distinct CFTR channel populations in the plasma membrane of primary human bronchial epithelial cells that had been transduced with adenovirus containing enhanced GFP (EGFP)-CFTR, one population that is diffusely distributed and another that is in cholesterol-dependent clusters (Abu-Arish et al., 2015). CFTR channels are assumed to be static during physiological regulation due to tethering by sodium-hydrogen exchanger regulatory factor (NHERF) and other scaffold and adapter proteins, and the factors determining their distribution on the surface of well-differentiated airway epithelial cells are not well understood. We report here that lipid raft-like microdomains containing clusters of CFTR channels are closely associated with the bases of motile cilia and with acid sphingomyelinase (ASMase), an enzyme that hydrolyzes plasma membrane sphingomyelin to ceramide. Surprisingly, ASMase is bound constitutively on the extracellular surface of the membrane and is activated by secretagogues, most likely through an autocrine redox signaling mechanism rather than by translocation to the plasma membrane from lysosomes as in other cell types (Zeidan and Hannun, 2007; Li et al., 2012). Activation of extracellular ASMase promotes the aggregation of CFTR, the ciliary protein centrin2, and ASMase itself. Ceramide-rich platforms are a well-established signaling mechanism under a wide range of pathological conditions (Grassmé et al., 2007; Stancevic and Kolesnick, 2010). The present results indicate that they also contribute to the physiological regulation of CFTR.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

CF lung tissue was obtained from F508del/F508del patients after lung transplantation with informed written consent and following protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal and McGill University. Non-CF lung tissue was from the National Disease Research Interchange (Philadelphia, PA). Primary human bronchial epithelial (pHBE) cells were isolated by the Primary Airway Cell Biobank at McGill University and supplied at first passage. Cells were plated on collagen-coated (PureCol; Advanced BioMatrix) Transwell supports and cultured for >3 wk at the air–liquid interface (Fulcher et al., 2005; Robert et al., 2008), then scraped, centrifuged, and fixed as described below.

For live cell imaging, pHBE cells were seeded at first passage in polycarbonate FluoroDishes (23.5 mm diameter optical glass bottom; World Precision Instruments, Inc.) precoated with collagen and transduced with adenovirus particles that cause the expression of EGFP-CFTR (Abu-Arish et al., 2015). Briefly, cells were cultured in bronchial epithelium growth medium (5% CO2/95% air, 37°C) until 80% confluent, then infected with EGFP-CFTR adenovirus particles (Vais et al., 2004) in OptiMEM medium (Gibco) supplemented with 100 nM vitamin D3 (Calbiochem) at a multiplicity of infection of 100. Particles were removed after 2 d by rinsing with fresh OptiMEM. Imaging was performed 2 d later in OptiMEM (5% CO2/95% air, 37°C). Transduction efficiency was 10–20%.

Cell surface biotinylation (CSB) and Ussing chamber experiments were performed using the cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial (CFBE) 41o− cell line stably expressing WT CFTR (provided by J. Hong and E. Sorscher, Emory University, Atlanta, GA). For surface biotinylation, cells were seeded on 10-cm culture dishes coated with human fibronectin (Corning) and maintained in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (Wisent) supplemented with 10% FBS (Wisent), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Wisent), and 1% L-glutamine (Wisent). To measure short-circuit current (Isc), cells were seeded on fibronectin-coated polyester membrane inserts (0.4 µM pore diameter, 6.5 mm diameter; Corning Costar) and kept submerged until the transepithelial electrical resistance reached >400 Ω⋅cm2 as measured using an epithelial volt-ohmmeter (World Precision Instruments). Apical medium was then aspirated and cultures were maintained at the air-liquid interface for another 7 d (CFBE41o−) or >21 d (pHBE) as described previously (Wong et al., 2018).

Immunostaining

Non-CF pHBE cells were differentiated on collagen-coated Transwell supports at the air-liquid interface for ≥3 wk (Fulcher et al., 2005; Robert et al., 2008). To visualize endogenous CFTR and the effects of VIP, cells were exposed bilaterally to control medium or medium containing 200 nM VIP (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h, then gently washed and scraped from the insert into PBS and centrifuged onto glass coverslips (500 rpm, 5 min; Cytospin 4; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Adherent cells were rinsed with PBS and fixed in 10% neutral formalin overnight at 4°C. For intracellular protein immunostaining, cells were permeabilized using 1% Triton X-100/PBS, blocked with 2% BSA/PBS for 1 h, and incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-CFTR primary antibody 596 (1:200 dilution; provided by J. Riordan, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics, Inc.) alone or in combination with a rabbit anti-centrin2 antibody (1:200; Abcam). They were then exposed to Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:1,000 dilution; Invitrogen) for 1 h, mounted in ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen), and imaged using an LSM-780 confocal microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a multiline argon laser (488 nm, 25 mW) and a 561-nm line laser (15 mW). To examine ASMase distribution on the apical surface of differentiated non-CF pHBEs, the above procedure was followed but without the membrane permeabilization step. The effect of amitriptyline (Ami) on ASMase distribution was assessed by pretreating cells with 13 µM Ami bilaterally for 1 h and then exposing them to 200 nM VIP for 10, 30, or 60 min. To examine the colocalization of ASMase with CFTR or cilia, the isolated and fixed cells were permeabilized, then stained according to the same procedure mentioned above. Mouse anti-β-tubulin (1:200) was used to label cilia.

Bronchial tissue was fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-µm-thick sections. Immediately before immunostaining, the sections were deparaffinized in three sequential xylene baths (5 min each) and rehydrated in a series of alcohol solutions (95%, 95%, 70%; 5 min each) followed by two rinses with distilled-deionized H2O and equilibration in PBS. Sections were incubated for 30 min in PBS containing 3% BSA, then washed in PBS before and after 10 min incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide to quench endogenous peroxidase activity, then immunostained as detailed above.

ASMase activity

ASMase activity was measured fluorometrically (k-3200; Echelon Biosciences Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the following modifications: Assays were performed on live pHBE cells expressing EGFP-CFTR that had been seeded in fluorodishes as described above. Substrate buffer and ASMase substrate were added onto the cells, and ASMase activity was measured by collecting samples under control conditions and during acute stimulation with VIP (200 nM), with or without Ami pretreatment (13 µM for 1 h). Stop buffer was added to samples taken 30, 60, or 120 min after adding substrate. Fluorescence intensity was measured using a spectrophotometer at 360 nm excitation and 460 nm emission at several time points after adding stop buffer (10, 20, and 30 min) to ensure that fluorescence was stable.

Live cell imaging

Subconfluent pHBE cells on glass coverslips were transduced with EGFP-CFTR and studied at 37°C in a humidified incubator in 5% CO2/95% air (Live Cell Instrument) on the stage of the confocal microscope as described previously (Abu-Arish et al., 2015). Image time series comprising 800 regions of interest (ROIs; 256 × 256 pixels) were collected from a flat area of the plasma membrane in contact with the coverslip using a Plan-Apochromat 63× (numerical aperture = 1.40) oil immersion objective with a confocal pinhole of 1 Airy unit, digital gain = 900, 0.5% laser power, 6.5 Hz frame rate, pixel diameter = 0.06 µm, and pixel dwell time 1 µs. The total number of time series images collected under each condition is shown in Table 1. To visualize CFTR distribution and the formation of platforms, larger areas (1,024 × 1,024 pixels) were collected at 5% laser power and a frame rate of 0.2 Hz (0.13 µm pixel diameter, 6 µs dwell time). All experiments were performed at 37°C.

Table 1. VIP and CCh modulate CFTR distribution and confined mobility at the cell surface of pHBE cells through lipid-dependent mechanisms.

| Treatment | CD ratio | DA ratio | Dmicro (µm2/s) × 0.001 | fmicro | R (μm) | ncella | Nexpb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctr | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 10.9 ± 0.6 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.322 ± 0.005 | 224 | 10 |

| VIP | 0.50 ± 0.05c | 2.7 ± 0.4d | 3.3 ± 0.2c | 0.40 ± 0.03d | 0.279 ± 0.005c | 164 | 8 |

| CCh | 0.38 ± 0.08c | 2.5 ± 0.3d | 4.77 ± 0.6c | 0.35 ± 0.04d | 0.283 ± 0.004c | 40 | 2 |

| COase +VIP | 0.87 ± 0.08 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 10.7 ± 0.7 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.303 ± 0.005 | 112 | 4 |

| Ami +VIP | 1.4 ± 0.2d | 0.50 ± 0.07c | 18.0 ± 1.0d | 0.14 ± 0.01c | 0.335 ± 0.005 | 85 | 4 |

(ncell) total number of cells

(Nexp) number of independent experiments

Smaller than Ctr, pcell < 0.001, pexp < 0.05.

Larger than Ctr, pcell < 0.001, pexp < 0.05

pHBE cells were exposed to 200 nM VIP or 2 µM CCh for 20–30 min and imaged in their presence. To reduce membrane cholesterol and disrupt lipid rafts, cells were incubated with 1 unit/ml cholesterol oxidase (COase; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h before the 30-min exposure to VIP, then imaged with both COase and VIP present. To reduce membrane ceramide levels, cells were treated with Ami (13 µM; Sigma-Aldrich), a functional inhibitor of ASMase, for 40 min before VIP treatment before imaging.

Determining cluster and platform size

Individual clusters and platforms were encircled using ImageJ software, and their areas were estimated from the number of pixels × single pixel area (Rasband, 1997-2018). Although the clusters (in contrast to the platforms) were optical resolution–limited size in the images and this approach provides only an upper estimate of microdomain area, measuring the subdiffraction-sized aggregates more accurately would only strengthen our conclusion regarding the different dimensions of rafts versus platforms. Total fluorescence of each cluster or platform was calculated as the number of pixels × mean fluorescence/pixel and is proportional to the total amount of CFTR in the microdomain. Microdomain size was quantified using pixel number and total area; however, line scan fluorescence profiles of a representative cluster and platform are shown in Fig. S3 B for illustration purposes.

Spatial and k-space image correlation spectroscopy (ICS) analyses

Details regarding the spatial ICS and k-space ICS (kICS) analyses are found in the supporting materials and references (Wiseman and Petersen, 1999; Kolin et al., 2006). Spatial ICS was used to quantify CFTR cluster density (CD; i.e., the average number of independent fluorescent entities per unit area, No. clusters/µm2) and the degree of aggregation (DA; i.e., proportional to the number of fluorescent particles per cluster, the cluster size).

A modification of the kICS analysis was used to study CFTR membrane dynamics (Pandzic, 2013; Abu-Arish et al., 2015). Briefly, the k-space temporal correlation function is obtained by calculating the temporal correlation function from the k-space domain image time series (kx, ky, t). This reciprocal space time series input is first obtained by performing a two-dimensional spatial fast-Fourier transform on each image (x, y) in the original fluorescence microscopy time series. A two-component exponential fit is applied to the k-space time correlation function for a single molecular species system that exhibits confined (micro-scale) and unconfined (macro-scale) diffusion dynamics within and between small domains distributed in two dimensions. The model yields effective mean squared displacements (MSDs) for the confined (Dmicroτ) and unconfined (Dmacroτ) populations of molecules and their respective amplitude parameters ( and ) at each time lag.

The slope of the macro MSD-versus-τ plot yields Dmacro, an effective diffusion coefficient of CFTR that averages over its behavior both within and between microdomains, as has been shown using computer simulations (Pandzic, 2013). The slope of the first three temporal lags in the micro MSD-versus-τ plot was used to calculate Dmicro, an effective diffusion coefficient for particles that are confined within membrane domains. The steady-state fractions within the “macro” and “micro” populations were calculated from the amplitudes at long temporal lag values. The y axis intercept of the micro MSD plot extrapolated from long temporal lags τ is R2/4. The R value and domain confinement are inversely related (Pandzic, 2013); i.e., the smaller the R value, the stronger the domain confinement and vice versa. Thus, the R value provides a measure of confinement strength.

CSB and immunoblotting

To quantify CFTR at the cell surface biochemically, CFBE41o− cells expressing WT CFTR were cultured to ∼95% confluence, serum-starved in OptiMEM medium (5% CO2/95% air, 37°C) for 24 h, exposed to 200 nM VIP or vehicle for 1 h to allow maximal lipid redistribution and platform induction, then surface biotinylated as described previously (Luo et al., 2009). Briefly, cultures were rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS and once with sodium borate buffer containing (in mM) 10 boric acid, 154 NaCl, 7.2 KCl, and 1.8 CaCl2, pH 9, then exposed for 15 min in the dark to sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (sulfosuccinimidyl-20(biotinamido)ethyl-1,3-dithiopropionate; Pierce Biotechnology) that had been freshly dissolved in borate buffer at 0.5 µg/ml. After three rinses with quenching buffer (25 mM Tris and 192 mM glycine, pH 8.3), cells were scraped and solubilized in 200 µl ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA) lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Tris/HCl, 1% wt/vol deoxycholic acid, 1% wt/vol Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors) for 20 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 4°C, and total cellular protein content was measured in the supernatant. Aliquots containing 500 µg protein were incubated with 50 µl streptavidin-agarose beads (preequilibrated with RIPA buffer) for 2 h at 4°C. Beads were rinsed five times with RIPA buffer; then 2× sample buffer (4% wt/vol SDS, 20 mM dithiothreitol, 20% wt/vol glycerol, 125 mM Tris/HCl, and 0.2% bromphenol blue, pH 6.8) was added at a 1:1 ratio to elute adsorbed proteins. Cells and lysates were kept on ice, and solutions were prechilled to 4°C. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for immunoblotting. Scanning densitometry was used for analysis, and measurements were normalized to the signal for Na+/K+ pump α subunit, a housekeeping membrane protein that is also biotinylated and pulled down. Immunoblots were also probed for biotinylated actin to check for leakage of sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin into cells (Luo et al., 2009).

Effect of inhibiting platform formation on CFTR functional expression

CFTR-dependent transepithelial current was measured in Ussing chambers as described previously (Matthes et al., 2016). Inserts were mounted in modified Ussing chambers (Physiological Instruments Inc.) and maintained at 37°C. For nonpermeabilized cells, the basolateral saline solution contained (in mM) 115 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 CaCl2, 2.4 KH2PO4, 1.24 K2HPO4, and 10 D-glucose. The apical saline solution contained (in mM) 1.2 NaCl, 115 Na-gluconate, 25 NaHCO3, 1.2 MgCl2, 4 CaCl2, 2.4 KH2PO4, 1.24 K2HPO4, and 10 glucose. In some experiments with CFBE41o− cells, the basolateral membrane was permeabilized by adding nystatin (200 µg/ml) to the basolateral side and replacing apical and basolateral saline solutions. All reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich except the CFTR inhibitor CFTRinh-172, which was from R&D Systems. Cultures were studied under Isc conditions except during 2-s voltage steps to ±1 mV at 100-s intervals to monitor resistance (Rt). Output from the voltage clamp amplifier (VCC200; Physiological Instruments, Inc.) was digitized (Powerlab 8/30; AD Instruments) and analyzed using Chart5 software. Measurements were taken as the increase in Isc (ΔIsc) induced by sequential additions of 100 nM VIP to the basolateral side, followed by apical addition of 10 µM forskolin (FSK). The CFTR inhibitor CFTRinh-172 was added on the apical side to confirm that ΔIsc was CFTR dependent. As a positive control, the purinergic agonist ATP (100 µM) was added apically at the end of experiments to stimulate Ca2+-activated Cl− channel current and confirm monolayer viability.

Statistics

Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. For imaging experiments in which ROIs were analyzed, results from 20 to 40 ROIs were averaged to obtain a single value for each independent experiment that was used when testing significance (pexp) with the unpaired Student’s t test. Considering individual cells as independent further increased the significance of observed differences (pcell).

Glossary

The following terms are defined for clarity. “Membrane microdomain” is a general term that encompasses both lipid rafts and ceramide-rich platforms. “Puncta” are minute spots of fluorescence caused by clustering of EGFP-CFTR, immunostained endogenous CFTR, or ASMase. Regions with many puncta are described as having a punctate distribution. “CFTR clusters” are small groups of CFTR channels located within the point spread function (PSF) of the objective (<250 nM dia.). Clusters are thought to be situated in lipid rafts, as we have shown previously that they are reduced by cholesterol depletion and increased by cholesterol supplementation (Abu-Arish et al., 2015). “Aggregation” refers to the fusion of lipid rafts into large platforms that bring together CFTR clusters and other raft-localized proteins. “Platforms” are large (2–4 µm dia.) ceramide-rich membrane microdomains that form during cell stimulation.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows specific CFTR immunostaining at the apical membrane of non-CF bronchus and the absence of apical CFTR in bronchial tissue from a patient homozygous for F508del-CFTR. Fig. S2 shows that CFTR immunostaining in well-differentiated, non-CF primary bronchial epithelial cells is abolished when primary anti-CFTR antibody is omitted. Fig. S3 shows representative images and the dimensions of EGFP-CFTR aggregates under control conditions, during stimulation, and when cells are stimulated after pretreatment with COase or Ami. Fig. S4 shows CFTR dynamics in unstimulated cells after pretreatment with COase or Ami.

Results

CFTR aggregation in bronchial tissue and pHBE cells

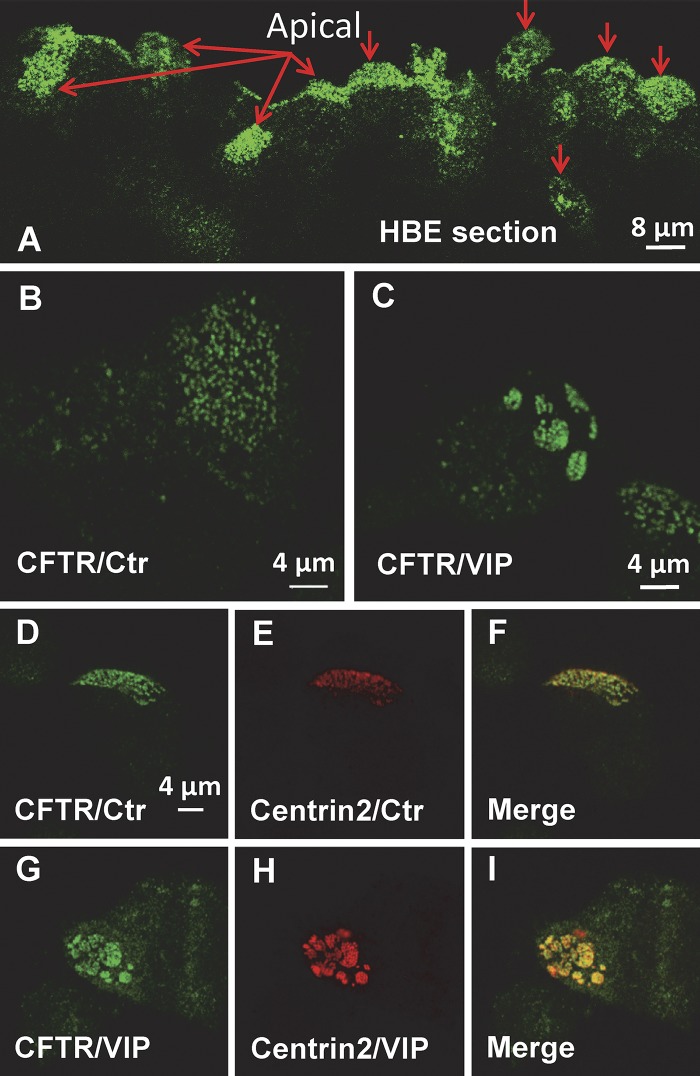

Immunostained sections of normal bronchus revealed CFTR at the apical pole of ciliated cells, with some aggregates apparent in oblique sections (Fig. 1 A, red arrows indicate apical aspect; see Fig. S1 A for perpendicular section). As expected, apical immunostaining was not detected in bronchial sections from a CF donor homozygous for F508del-CFTR (Fig. S1 C). pHBE cells were cultured at the air–liquid interface for 1 mo, then scraped into PBS, centrifuged onto glass coverslips, and fixed as described in Materials and methods. Immunostaining revealed two populations of endogenous CFTR at the apical membrane under control conditions, one that was diffusely distributed and the other that was punctate (Fig. 1 B). The distribution of endogenous CFTR closely resembled that of EGFP-CFTR observed during live cell imaging of unpolarized pHBEs transduced with an adenovirus (Abu-Arish et al., 2015). CFTR clusters or platforms were not observed when cells were exposed only to the secondary antibody (Fig. S2). Exposure of well-differentiated non-CF pHBE cells to 200 nM VIP caused a remarkable reorganization of CFTR into platform-like structures that were several micrometers in diameter (Fig. 1 C). The time course of platform induction varied between cells but usually began within 10 min and was maximal within 60 min. The number and distribution of CFTR clusters are reminiscent of motile cilia on airway epithelial cells, and since CFTR expression is detected predominantly in ciliated cells (Kreda et al., 2005), we examined whether CFTR clusters colocalize with the ciliogenesis marker centrin2 (Herawati et al., 2016). Immunostaining revealed that CFTR and centrin2 are colocalized under control conditions (Fig. 1, D–F) and also when VIP stimulation induces large platforms (Fig. 1, G–I). These unexpected results suggest that CFTR resides in the raft-like periciliary membrane surrounding the base of each cilium (Emmer et al., 2010), and that CFTR and cilia undergo extensive reorganization during stimulation by physiological secretagogues such as VIP.

Figure 1.

Immunolocalization of endogenous CFTR and Centrin2. Primary HBE cells were immunostained in superior bronchial tissue (A) and primary HBE cells (B–I) that had been cultured for >3 wk at the air–liquid interface. (A) Distribution of CFTR in non-CF bronchial tissue shows puncta and platforms. Red arrows point to the apical surface. (B and C) Distribution of endogenous CFTR under control (Ctr) conditions and after 1 h bilateral exposure to 200 nM VIP at 37°C, respectively. Note both diffuse and punctate immunostaining under Ctr conditions and aggregation into large (2–4 µm dia.) platforms on cells after VIP exposure. (D–F) Distribution of endogenous CFTR (CFTR/Ctr) and the ciliogenesis marker Centrin2 (Centrin2/Ctr) under Ctr conditions. Note the colocalization of CFTR puncta with cilia basal bodies. (G–I) Redistribution of endogenous CFTR and Centrin2 during VIP stimulation. Note the aggregation of CFTR and Centrin2, which remain colocalized. Images are representative of n = 20–40 cells in at least two experiments under each condition.

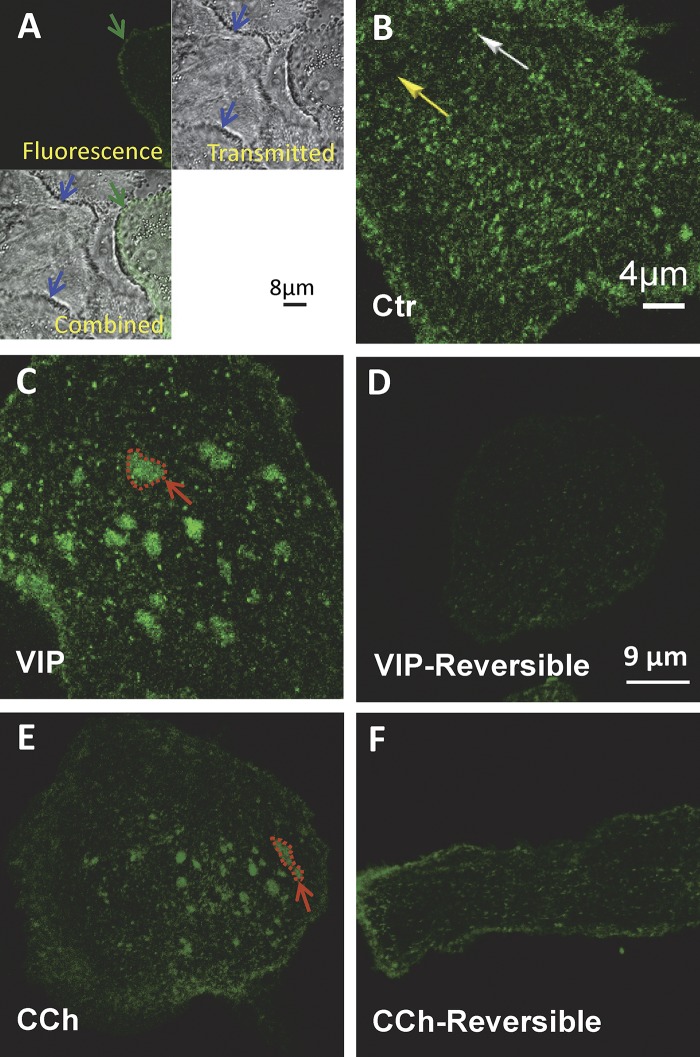

VIP caused aggregation of adenoviral EGFP-CFTR in live pHBE cells that closely resembled endogenous CFTR after fixation and immunostaining (Fig. 2). No signal was detected in adjacent untransduced cells, confirming that background staining was due to diffusely distributed EGFP-CFTR rather than cell autofluorescence (in Fig. 2 A, note EGFP-CFTR in a transduced cell indicated by the green arrow, and negligible fluorescence in neighboring cells indicated by blue arrows in the Transmitted and Combined images). As with endogenous CFTR, EGFP-CFTR on the plasma membrane of live cells formed diffuse (yellow arrow) and punctate (white arrow) populations under basal conditions (Fig. 2 B). The puncta contain clusters of two to six CFTR molecules within a PSF-sized focal spot according to Photobleaching Intensity Step Analysis (unpublished data).

Figure 2.

Reversible aggregation of EGFP-CFTR induced by VIP and CCh in pHBE cells. pHBE cells were transduced with EGFP-CFTR adenovirus and cultured on collagen-coated glass for 4 d. (A) Autofluorescence is negligible compared with EGFP-CFTR fluorescence. Upper left: Confocal image of pHBE cell transiently expressing EGFP-CFTR (green arrow). Upper right: Transmitted light image of the same field reveals the presence of nonfluorescent cells (blue arrows). Lower left: Combined image showing that autofluorescence of untransduced cells (blue arrow) is negligible compared with the EGFP-CFTR expressing cell (green arrow). (B) Distribution of EGFP-CFTR under Ctr conditions showing diffuse background staining (yellow arrow) and bright puncta (white arrow). (C) Aggregation of EGFP-CFTR into large (2–4 µm dia.) platforms after 20–30 min exposure to 200 nM VIP at 37°C (red arrow shows one example). The scale bar in B also applies to C. (D) Platforms have dispersed 24 h after VIP washout. (E) Aggregation of EGFP-CFTR into large platforms induced by 20–30 min exposure to 2 µM CCh at 37°C. (F) No platforms remain 24 h after CCh washout. The scale bar in D also applies to E and F.

Exposing cells to 200 nM VIP for 20 min produced large CFTR platforms (Fig. 2 C) that persisted for several hours in the presence of VIP and were completely dispersed within 24 h after VIP washout (Fig. 2 D). Platforms were generally observed within a few minutes but sometimes took longer to develop, and the delay was most variable using primary cells from different donors, suggesting individual variation may contribute to the variation. Regardless, platforms remained stable for >1 h once formed; therefore, we chose relatively long exposure times (20–60 min) for imaging and CSB experiments, respectively. Exposure to 2 µM CCh for 20 min also produced platforms (Fig. 2 E) that slowly disappeared after CCh removal and were eliminated within 24 h (Fig. 2 F). Platforms were not associated with shape changes or cell shrinkage, which would be detected using image correlation methods. Cells remained viable for ≥3 d after exposure to both secretagogues. The fraction of cells undergoing apoptosis was low and unaffected by VIP when assayed as surface phosphatidylserine using an annexin XII–based fluorescent probe (Kinetic Apoptosis kit; Abcam; data not shown). The presence of CFTR at the plasma membrane was not required for platform induction as platforms were observed in untransduced cells lacking WT CFTR. These results indicate that platforms form in response to physiological stimuli and are not limited to pathological conditions such as infection, cell stress, or the activation of TNF family death receptors.

VIP-induced aggregation into platforms reduces the number of CFTR clusters per unit area and is blocked by Ami

To characterize VIP-induced platforms, we began by estimating the dimensions and fluorescence of the membrane microdomains that contain CFTR, then determined the number of clusters per unit area (CD) and their DA under different conditions as described in Materials and methods (Fig. S3). Clusters were present under basal and stimulated conditions; however, platforms like those in Fig. 2 only appeared when cells were stimulated by CCh (2 µM, 20 min) or VIP (200 nM, 20 min; Fig. S3 A). Platform induction by VIP was reduced by 1 h pretreatment with 1 unit/ml COase (to deplete membrane cholesterol) or 40 min treatment with 13 µM Ami (to inhibit ceramide formation by ASMase; Fig. S3 A). Microdomains having dimensions near the limit of optical resolution (<0.25 µm) were considered clusters whereas large aggregates (>1 µm dia.) were considered platforms (Fig. S3 B). Microdomain areas were estimated by counting pixels (ROI = 1,024 × 1,024 pixels; five cells/condition from three different experiments; Fig. S3 C). On average, the total fluorescence of a platform was ∼20-fold higher than that of a cluster (Fig. S3 D), suggesting that ∼100 CFTR channels are incorporated into a typical platform during VIP stimulation.

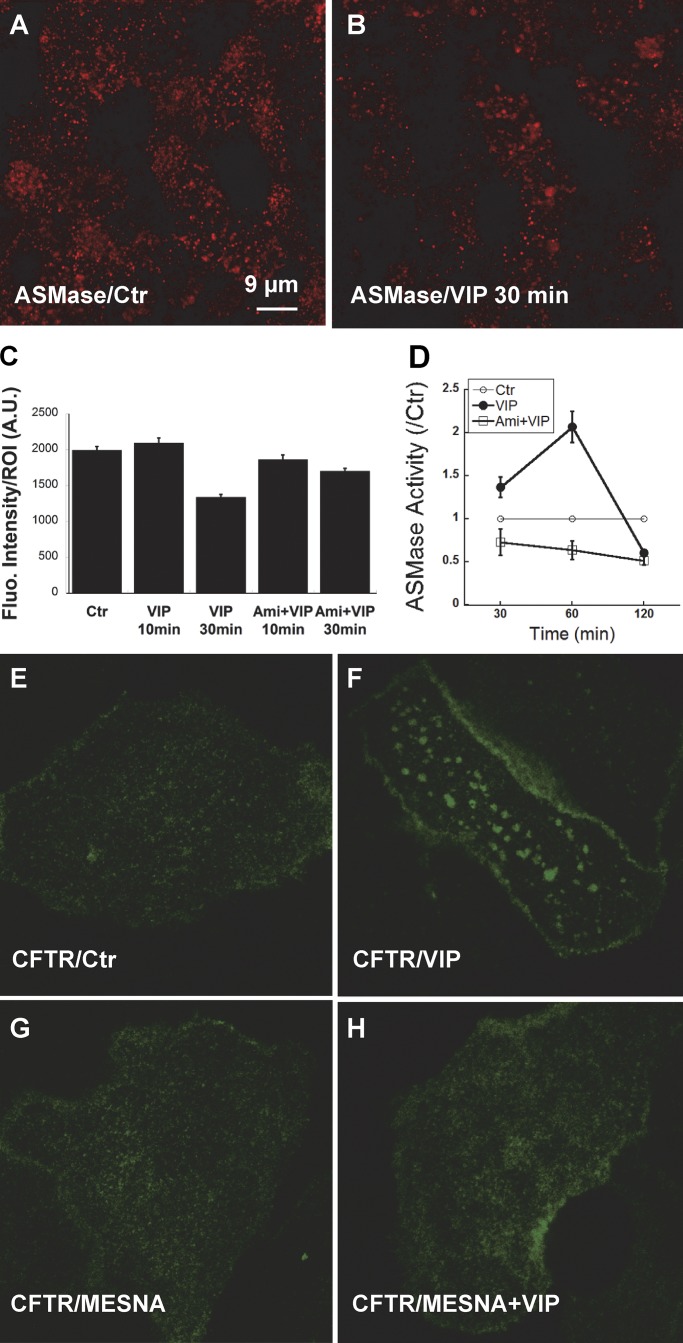

Extracellular ASMase colocalizes with CFTR clusters and is activated by VIP

Ceramide is formed in the plasma membrane by ASMase, which cleaves phosphocholine from sphingomyelin in the outer leaflet. In many cells, ASMase is translocated from the lysosomal compartment to the cell surface in response to cell stress and a broad range of pathological stimuli (Grassme et al., 2001; Zeidan and Hannun, 2007). Ceramide changes the biophysical properties of the membrane and causes lipid rafts to coalesce (Grassmé et al., 2007; Alonso and Goñi, 2018). To examine if ASMase is translocated to the plasma membrane during acute VIP stimulation, we compared ASMase immunostaining on unpermeabilized, well-differentiated pHBEs under control conditions and after exposure to 200 nM VIP. ASMase immunofluorescence was readily detected on unpermeablized pHBEs under control conditions and after stimulation with VIP for 10 or 30 min (Fig. 3, A and B). Total ASMase immunofluorescence was not altered after 10 min VIP exposure and was reduced by ∼33% after 30 min exposure according to the mean fluorescence intensity of multiple ROIs (1,024 × 1,024 pixels; n = 50–130 ROIs per condition, four donors studied in separate experiments; Fig. 3 C). Similar immunofluorescence was detected after 10 or 30 min VIP stimulation following pretreatment with 13 µM Ami for 1 h. These results demonstrate that ASMase protein is constitutively bound to the extracellular surface of the plasma membrane, and its levels are not increased by acute VIP stimulation.

Figure 3.

Constitutive binding of ASMase on the cell surface and its redox activation by VIP. (A and B) Immunofluorescence detection of ASMase on the apical membrane of unpermeabilized, well differentiated pHBE cells under Ctr conditions (A)and 30 min after treatment with 200 nM VIP (B). (C) Mean fluorescence intensity of ROIs (1,024 × 1,024 pixels; n = 50–130 ROIs per condition, cells from four donors studied in separate experiments). Cells were imaged under Ctr conditions, after 10 or 30 min stimulation with VIP, or following 1 h pretreatment with Ami (13 µM) followed by 10 or 30 min VIP. Stimulation for 30 min reduced ASMase surface immunostaining by 33%. (D) Normalized ASMase activity at the plasma membrane of subconfluent pHBEs expressing EGFP-CFTR at 30, 60, and 120 min after treatment with VIP. Pretreating cells with 13 µM Ami for 1 h reduced ASMase activity below the Ctr level, suggesting there is residual ASMase activity under basal conditions. Mean ± SEM. (E–H) Oxidation of extracellular ASMase stimulates formation of ceramide-rich platforms. (E) Confocal images of pHBE cells show the distribution of EGFP-CFTR under Ctr conditions. (F) EGFP-CFTR aggregation into large platforms after 20 min exposure to 200 nM VIP at 37°C. (G) The distribution of CFTR in unstimulated cells is unaffected by the extracellular reducing agent MESNA (100 mM). (H) MESNA blocks the formation of platforms in response to VIP; compare with F. Fluo., fluorescence; A.U., arbitrary units.

To determine if the extracellular ASMase is stimulated by VIP, we assayed its activity on the surface of subconfluent pHBEs expressing EGFP-CFTR using a fluorometric assay as described in Materials and methods. ASMase activity increased 1.4- to 2.0-fold following exposure to VIP for 30–60 min and then declined (Fig. 3 D). Pretreating cells with 13 µM Ami inhibited VIP-stimulated ASMase activity at both time points. VIP stimulation for 120 min reduced ASMase activity below the baseline level measured in time controls. Control experiments indicated that neither VIP nor Ami affected the fluorescence of the ASMase substrate under cell-free conditions, confirming that the fluorescence changes were due to ASMase activity on the epithelial cell surface.

Activation of extracellular ASMase by the G protein–coupled receptor agonist VIP was unexpected and raised a question as to what signaling mechanism might mediate stimulation ASMase and induce platforms. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been reported to activate ASMase in several other cell types; therefore, we examined if VIP could induce platforms in the presence of the mild, membrane-impermeant reducing agent 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate (MESNA). As expected, platforms were not observed under control conditions in pHBE cells expressing EGFP-CFTR (Fig. 3 E), although they appeared within 20 min during exposure to 200 nM VIP (Fig. 3 F). Exposure to MESNA alone did not alter the distribution of EGFP-CFTR (Fig. 3 G) and abolished the induction of platforms by VIP stimulation (Fig. 3 H). A redox mechanism for activation of extracellular ASMase was further suggested by an approximate twofold increase in ASMase activity when cells were exposed to exogenous 200 µM H2O2 that was abolished by Ami pretreatment (data not shown). These results are consistent with VIP activation of extracellular ASMase and formation of ceramide-rich platforms through autocrine release of an oxidant, although other inhibitory effects of MESNA cannot be excluded.

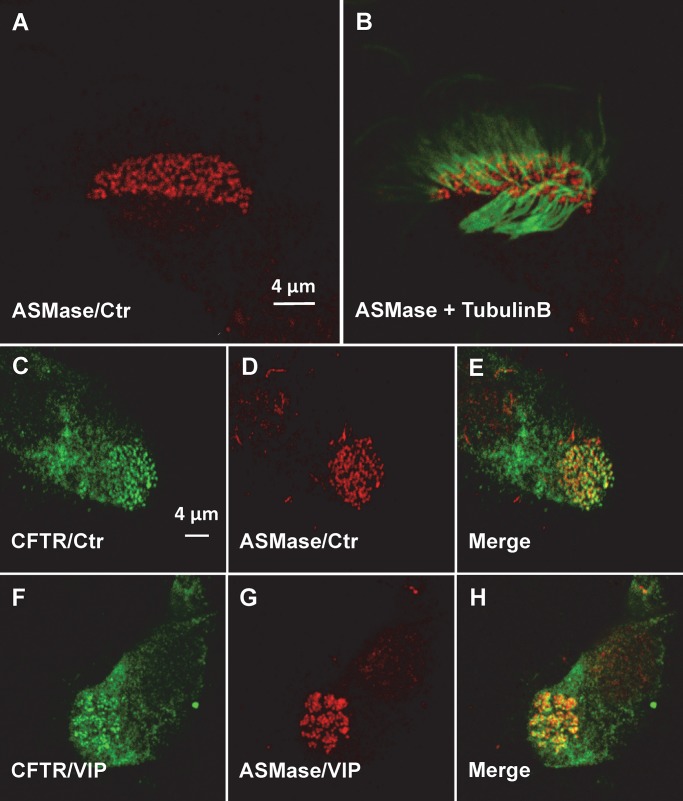

CFTR clusters are situated in lipid rafts (Abu-Arish et al., 2015) that coalesce into large platforms in response to VIP stimulation (this study, CFTR aggregation in bronchial tissue and pHBE cells). Ceramides that form in lipid rafts by hydrolysis of sphingomyelin are thought to coalesce spontaneously into microdomains due to their extensive hydrogen bonding, which causes them to become tightly packed, and also because they are extremely hydrophobic, with a phase transition temperature of ∼90°C. These properties are thought to cause ceramides to segregate from other lipids in the membrane and form highly ordered microdomains (Bollinger et al., 2005). Since ceramide would need to be generated within the lipid rafts that contain CFTR to induce its aggregation into platforms, we hypothesized that extracellular ASMase might colocalize with CFTR clusters. To test this, we performed immunofluorescence staining of CFTR and ASMase in well-differentiated pHBEs. Since CFTR clusters colocalize with motile cilia, cells were also exposed to antibody against the ciliary protein tubulin β. Endogenous ASMase had a punctate distribution under control conditions in both permeabilized and unpermeabilized pHBEs (Fig. 4 A), with ASMase immunostaining at the base of each motile cilium (Fig. 4 B) as shown above for CFTR. Colocalization of endogenous CFTR and ASMase was confirmed under unstimulated control conditions by coimmunostaining both proteins and observing yellow in the merged image (Fig. 4, C–E). CFTR and ASMase were both reorganized into large platforms during VIP stimulation (Fig. 4, F–H). These results indicate that ASMase is constitutively present on the exterior surface of the plasma membrane, apparently on the lipid rafts that also contain clusters of CFTR channels.

Figure 4.

Colocalization of endogenous ASMase and CFTR. (A) Punctate distribution of ASMase on the apical surface of well-differentiated, ciliated pHBEs under Ctr conditions. (B) ASMase immunofluorescence is detected at the base of each motile cilium (β-tubulin immunostaining). (C–E) Co-localization of endogenous CFTR and ASMase under Ctr conditions. (F–H) Redistribution of CFTR and ASMase into platforms during VIP stimulation.

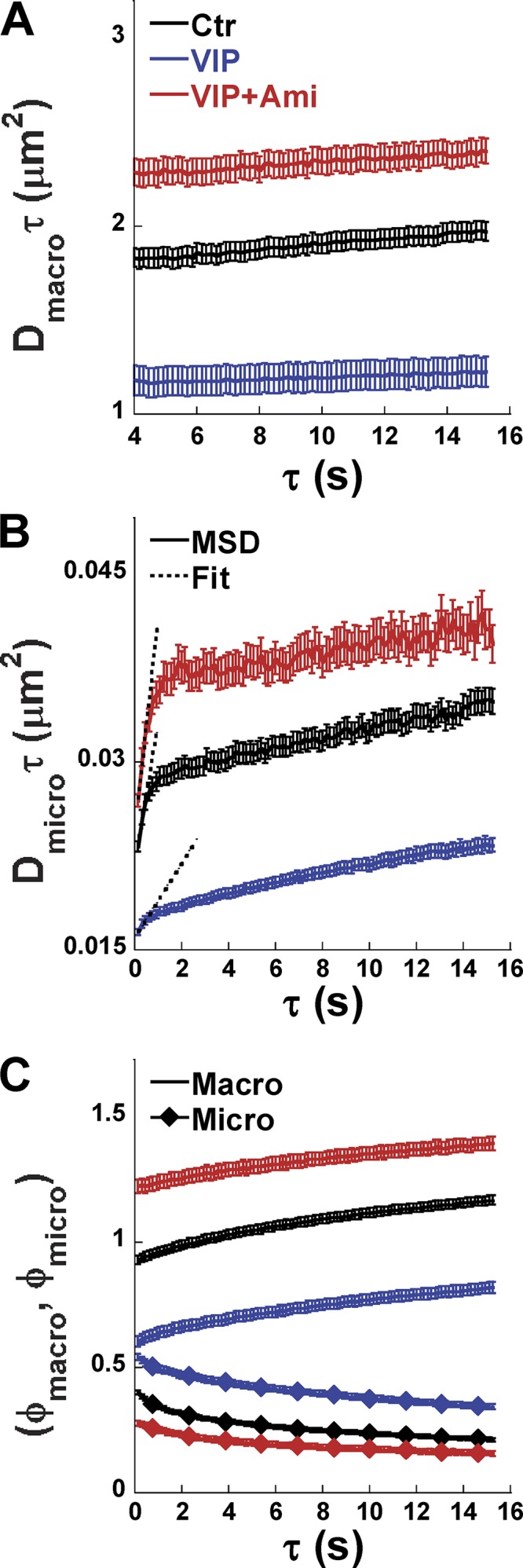

Induction of ceramide-rich platforms reduces CFTR lateral mobility and increases confinement

To study CFTR mobility and confinement on pHBEs, we used kICS (Kolin et al., 2006; Pandzic, 2013; Abu-Arish et al., 2015). This analysis yields the effective macroscopic diffusion coefficient for CFTR lateral movements within and between microdomains (Dmacro), the effective diffusion coefficient for CFTR exclusively within microdomains (Dmicro), and the fraction of CFTR in each of these two populations (fmacro and fmicro; see Materials and methods). VIP caused EGFP-CFTR aggregation and a simultaneous 3.2-fold decrease in Dmacro (control: Dmacro = 0.016 ± 0.001 μm, VIP: Dmacro = 0.005 ± 0.001 μm; Fig. 5 A). The decrease in Dmacro was calculated from the slopes of the macro MSD curves (i.e., Dmacroτ versus lag τ) during VIP treatment and under control conditions (Fig. 5 A). Pretreating cells with 13 µM Ami for 40 min to inhibit ASMase (Liu and Anderson, 1995; van Blitterswijk et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2005) increased Dmacro above control levels, further evidence that even basal ceramide levels influence CFTR dynamics. The plateau in the MSD curve of the slow CFTR population (Dmicroτ versus lag τ) indicates confinement, while linear regression of the first three points reveals a 3.3-fold decrease in microscopic diffusion coefficient during VIP exposure (Dmicro = 0.0033 ± 0.0002 μm) compared with control conditions (Dmicro = 0.011 ± 0.001 μm; Fig. 5 B). Amplitude plots of and versus lag τ demonstrated reciprocal changes in the fraction of CFTR within each population (fmacro and fmicro, respectively; Fig. 5 C) post VIP treatment. The confined fraction (, blue line) was increased and the unconfined fraction (, blue diamonds) was decreased accordingly (Fig. 5 C). This poststimulation redistribution into the low, more confined population fraction may be due to slower CFTR exit from ceramide-rich platforms, although enhanced entry into membrane microdomains cannot be excluded.

Figure 5.

VIP alters CFTR dynamics, and its effects are blocked by Ami. (A) Mean squared displacement Dmacroτ increases linearly as a function of τ under all conditions, and its slope (Dmacro) yields the effective macroscopic diffusion coefficient for the unconfined CFTR population. (B) Mean squared displacement Dmicroτ increases linearly for the first few temporal lags under all conditions, and then its slope decreases at long τ. The first three Dmicroτ values were fitted with straight lines as shown to obtain the initial slope and Dmicro, which quantifies CFTR mobility inside confinements (microdomains). VIP treatment resulted in a smaller Dmicro compared with Ctr conditions, and this decrease was abolished by pretreating cells with Ami to inhibit ceramide production. (C) Amplitudes of the macro (, line only) and micro (, diamond symbols) components of the k-space correlation function and their dependence on τ. Mean ± SEM. For the number of cells analyzed, see Table 1.

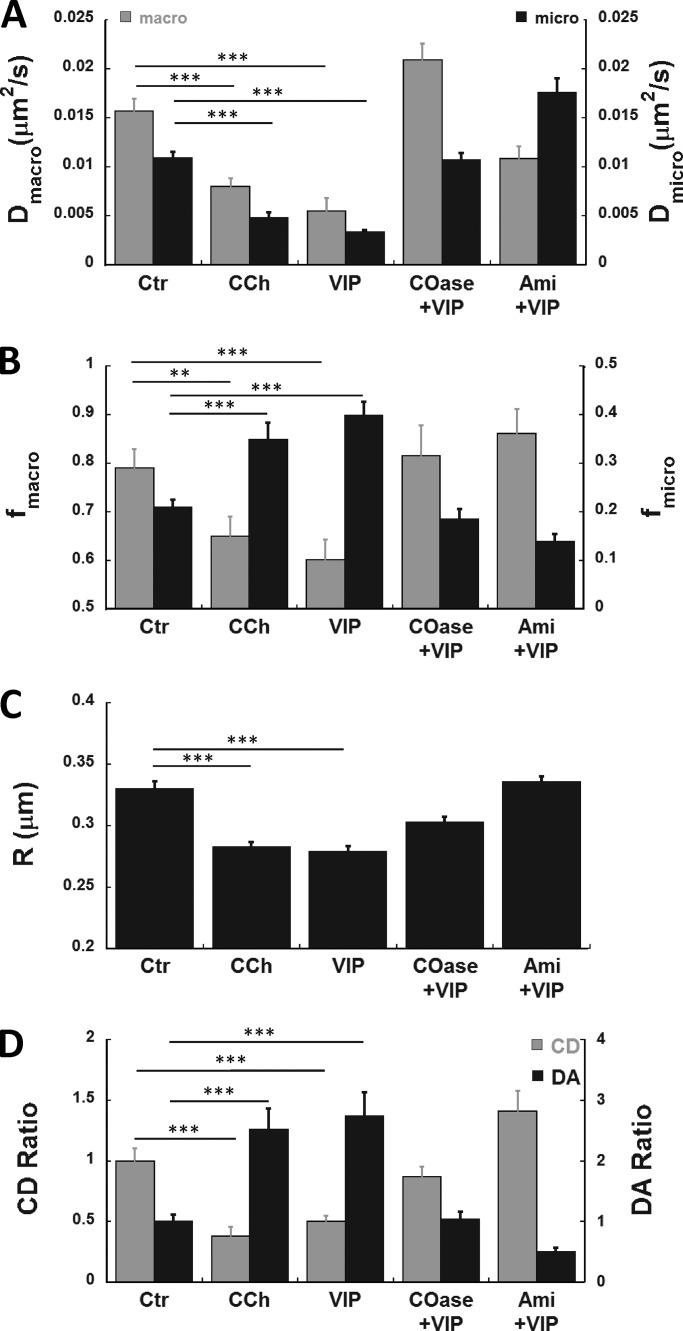

CFTR dynamics under different experimental conditions are summarized in Fig. 6 and Table 1. Dmicro and Dmacro were reduced during CCh and VIP stimulation, and these effects were diminished by pretreating cells with 1 unit/ml COase for 1 h to disrupt rafts, or 13 µM Ami for 40 min to inhibit ceramide synthesis (Fig. 6 A). The rapidly diffusing population fraction (fmacro) was reduced by both stimuli in concert with a twofold increase in the confined population fraction (fmicro), which was highly significant (Fig. 6 B). CCh and VIP reduced the confinement parameter R (inversely proportional to confinement strength), indicating that CFTR confinement was increased, and this decrease was blunted by cholesterol depletion and ASMase inhibition (Fig. 6 C). Taken together, these kICS results identify two dynamically distinct CFTR populations consistent with diffuse and punctate distributions and their regulation by VIP and CCh.

Figure 6.

CFTR aggregation and dynamics are regulated by VIP and CCh through lipid-dependent mechanisms. pHBE cells transduced with EGFP-CFTR adenovirus were imaged 4 d later under Ctr conditions and during exposure to CCh or VIP alone, VIP after 1 h pretreatment with COase to disrupt rafts (COase+VIP), or VIP after 40 min pretreatment with Ami to inhibit ceramide synthesis by ASMase (Ami+VIP). (A) Both Dmacro and Dmicro of CFTR were decreased significantly after VIP or CCh treatment. This decrease was prevented by pretreating cells with COase to disrupt lipid rafts or Ami to inhibit ceramide synthesis. (B) The unconfined fraction of the CFTR population fmacro (gray bars) decreased during VIP or CCh exposure but not if cells were pretreated with COase or Ami. The confined CFTR population fraction fmicro (black bars) increased approximately twofold during VIP stimulation, and this was prevented by pretreating cells with COase or Ami, confirming the lipid dependence of CFTR redistribution. (C) VIP reduced the effective diffusion radius R (inversely related to confinement strength), indicating a decrease in the exchange dynamics of CFTR between the bulk membrane and regions of confinement. This decrease coincided with the formation of platforms and was prevented by pretreating cells with COase or Ami. (D) Quantitation of CD and DA using spatial ICS. CD and DA after normalization to their respective control values (shown as CD ratio and DA ratio, respectively). CCh and VIP treatments both caused greater than twofold decrease in CD. Pretreatment with COase abolished the VIP effect, whereas Ami increased CD above the control level, suggesting there is significant ceramide formation even under basal conditions. Opposite changes in DA were also observed. The DA was increased greater than twofold by CCh or VIP, and these increases were abolished by maneuvers that disrupt rafts or platforms. Mean ± SEM, n = 40–224 ROIs, two to eight independent experiments, Error bars are ± SEM. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.005. See Table 1.

To quantify CFTR aggregation, we used spatial ICS (see Materials and methods) to determine a CD parameter (proportional to the number of independent fluorescent entities per unit area) and the DA (average fluorescence intensity divided by the CD parameter and therefore proportional to aggregate size). Since ICS relies on fluorescence collected on a sampling scale that corresponds to the diffraction-limited focal spot of the microscope, it yields a minimum estimate of CD and an upper limit for DA when analyzing microdomains larger than the optical PSF. Both CCh and VIP reduced the CD (gray bars) by >50% compared with prestimulation control levels, and this decrease was inhibited by pretreating cells with COase to deplete membrane cholesterol and disrupt lipid rafts (Fig. 6 D). Interestingly, pretreatment with Ami not only blocked the decrease in CD but increased it above the control level, suggesting that CFTR localization depends on basal ceramide levels even in unstimulated cells (Fig. S4). The reduction in CD during VIP stimulation is consistent with aggregation of nanoscale lipid rafts into a smaller number of microscale platforms, as indicated by the high DA during CCh or VIP exposure (Fig. 6 D, black bars). COase and Ami both inhibited aggregation. In summary, stimuli reduce the number of CFTR-containing microdomains per unit area by stimulating their fusion, and this effect depends on both cholesterol and ceramide (Table 1).

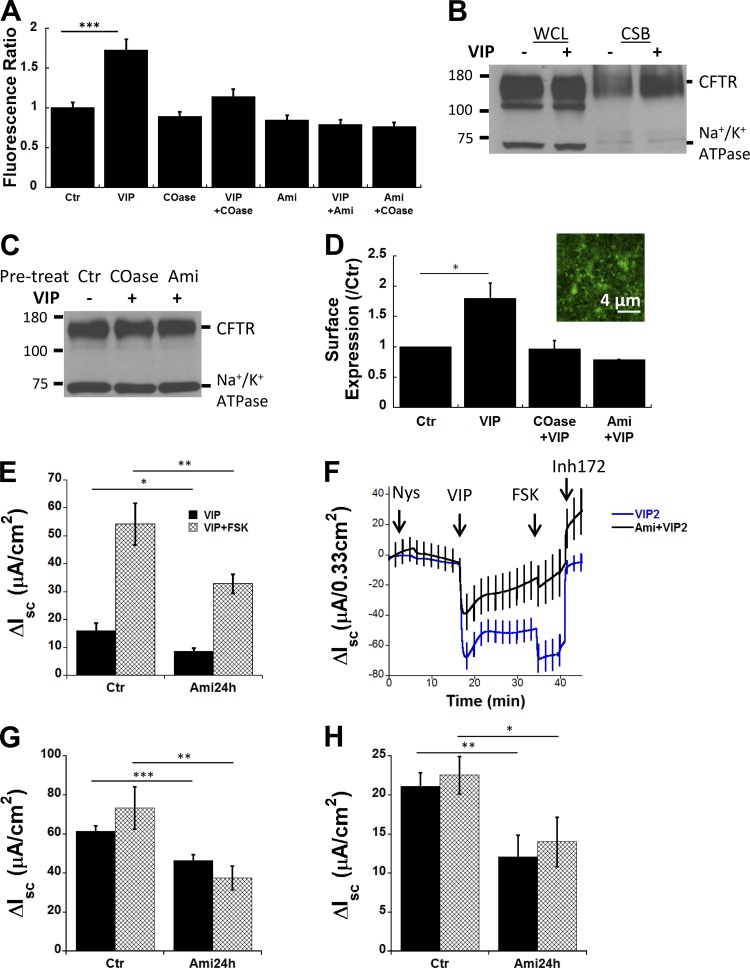

Inhibiting platform formation prevents plasma membrane CFTR accumulation, reducing channel activity during VIP stimulation

CFTR recycles between the plasma membrane and endosomes, and since microdomains containing CFTR can persist for many hours, we wondered if they might stabilize CFTR at the cell surface and increase its functional expression. We transduced pHBE cells with adenoviral EGFP-CFTR and measured fluorescence intensity before and during VIP stimulation while focusing on the ventral aspect of the cell that is in contact with the flat glass surface. Mean fluorescence increased ∼60% during VIP stimulation compared with control conditions (see Table 1 for n; P < 0.001, Fig. 7 A). Pretreating cells with COase reduced fluorescence near the plasma membrane and inhibited the increase elicited by VIP. Ami pretreatment also reduced surface fluorescence and abolished the VIP-induced increase (Fig. 7 A). The inhibitory effects of Ami and COase were not additive, suggesting they may act through a common pathway.

Figure 7.

VIP increases CFTR retention at the plasma membrane through a lipid-dependent mechanism. (A) EGFP-CFTR fluorescence ratio at the surface of subconfluent pHBE cells normalized to the control fluorescence before VIP stimulation. Fluorescence was increased ∼60% by VIP (P < 0.001), and this response was prevented by pretreating cells with COase to disrupt lipid rafts, or with Ami to inhibit ceramide synthesis. (B–D) CSB of CFTR in CFBE41o− cells. (B) Shows no effect of VIP stimulation on total CFTR expression or Na+/K+ ATPase α subunit (loading control) in whole cell lysates but reveals an 80% increase in CFTR that is CSB after VIP stimulation. (C) Pretreatment with COase or Ami individually prevents the VIP-induced increase in cell surface CFTR. (D) Summary of surface biotinylation results under Ctr conditions and with VIP. Inset: Exposure to VIP alone induces small EGFP-CFTR platforms in CFBE41o− cells. (E) Inhibiting ceramide synthesis blunts VIP-stimulated and also FSK-stimulated short-circuit current responses (ΔIsc). (F) Isc traces recorded using basolaterally permeabilized CFBE41o− cells and an apical-to-basolateral Cl− gradient to functionally remove the basolateral membrane. (G) Summary of Isc responses to VIP in basolaterally permeabilized CFBE41o− cells showing that VIP stimulation under these conditions was also inhibited 40–45% by Ami pretreatment. (H) VIP- and FSK- stimulated Isc across pHBE cells was reduced 43% and 38% by pretreatment with Ami, respectively. n = 8–12 filters/condition. Mean ± SEM, *, P < 0.025; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Nys, nystatin; Inh, inhibitor.

CSB was used as an independent method to assess the impact of platform formation on CFTR abundance in the plasma membrane. It was necessary to use the immortalized bronchial cell line CFBE41o− stably expressing CFTR for these experiments; however, CFBE41o− cells were cultured under the same conditions used when imaging primary cells. VIP (200 nM, 1 h) increased the amount of CSB CFTR by ∼80% without altering the level of CFTR abundance in whole cell lysates (Fig. 7 B), consistent with the increase in EGFP-CFTR fluorescence at the plasma membrane. This accumulation did not occur when cells were pretreated with COase or Ami to inhibit induction of platforms (Fig. 7 C). Surface biotinylation normalized to controls is shown in Fig. 7 D under each condition. The inset in panel Fig. 7 D confirms that VIP produces platforms in CFBE41o−, although they were smaller than those usually found in pHBE cells.

To assess the role of platforms in transepithelial anion transport, VIP and FSK-stimulated short circuit currents were compared with and without Ami pretreatment. VIP causes an increase in Isc across CFBE41o− cells, and FSK addition caused further stimulation (Fig. 7 E). Inhibiting ceramide synthesis with Ami reduced responses to sequential VIP and VIP+FSK stimulations by 40–45%, indicating a reduction in the functional expression of CFTR. The smaller stimulation elicited by VIP compared with FSK suggested basolateral entry might be rate-limiting; therefore, experiments were also performed after the basolateral membrane was permeabilized using nystatin, and an apical-to-basolateral Cl− gradient was imposed (Fig. 7 F). Ami pretreatment again caused ∼40% inhibition of the current that was carried by CFTR, as indicated by sensitivity to the CFTR inhibitor CFTRinh-172. Under these conditions, the stimulations produced by VIP and FSK were similar (Fig. 7, F and G). Regardless, VIP and maximal (VIP+FSK) stimulations were both inhibited by Ami. Finally, inhibiting ceramide formation also reduced responses to sequential VIP and FSK from 43% to 38% in well-differentiated pHBE cells, confirming the results obtained using the CFBE41o− cells (Fig. 7 H). These results indicate that VIP-induced accumulation of CFTR at the apical membrane contributes to the secretory response and depends on the formation of ceramide-rich platforms in both the CFBE41o− and well-differentiated pHBE cells.

Discussion

The present results indicate that CFTR behavior on the surface of bronchial epithelial cells is more dynamic than previously thought and depends on membrane lipids. Nanoscale clusters of CFTR channels fuse into large platforms up to several micrometers in diameter when cells are exposed to VIP or CCh. This aggregation of CFTR clusters into long-lived platforms is required for VIP to increase the amount of CFTR at the cell surface of both unpolarized and highly differentiated airway epithelial cells. Although platforms are commonly observed under pathological conditions, to our knowledge, this is the first evidence for a large-scale CFTR redistribution on the cell surface during regulation physiological agonists. In the present study, platforms were triggered by activation of ASMase that was constitutively bound to the cell surface rather than by rapid translocation from lysosomes as described for other cells. We examined CFTR distribution and lateral mobility within ceramide-rich platforms and found that CFTR clusters colocalize with both ASMase and the ciliogenesis marker centrin2, suggesting an association with motile cilia.

These results are consistent with previous reports that CFTR is present in a DRM fraction prepared from airway cells (Dudez et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008). Approximately half of the total CFTR in the Calu-3 cell line was found in a DRM fraction and was cholesterol-dependent (Wang et al., 2008). CFTR was also demonstrated in the DRM fraction in Madin-Darby Canine Kidney cells, where its abundance was increased by the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α (Dudez et al., 2008). Since the TNF-α receptor stimulates ceramide synthesis (Zhang et al., 2009), it is likely that the DRM fractions containing CFTR in those studies included both lipid rafts and ceramide-rich platforms. Ceramide-rich platforms are induced under a wide range of conditions that lead to apoptosis including activation of the FAS receptor CD95 (Grassme et al., 2001) and cell stresses such as short-wavelength ultraviolet light irradiation (Rotolo et al., 2005) and infection (Grassmé et al., 2003, 2005). A protective role of platforms during infection has been demonstrated in studies of ASMase knockout mice, which had exaggerated IL-1β release and increased mortality when infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Grassmé et al., 2003). The presence of CFTR in platforms may facilitate internalization of bacteria and viruses, thereby triggering apoptosis (Grassmé et al., 2003; Kowalski and Pier, 2004). In humans, mutations in the SMPD1 gene encoding ASMase cause Niemann–Pick disease types A and B and are associated with recurring pulmonary infections that begin in the first few months of life. The microdomains elicited by physiological secretagogues reported here have some similarities to those seen previously under pathological conditions but differ in that they do not require translocation of active ASMase to the plasma membrane during acute stimulation. Another major difference is that platforms in this study were fully reversible and not associated with apoptosis.

We reported previously that a population of CFTR channels resides in cholesterol-dependent clusters under basal conditions and concluded they are in nanoscale lipid rafts (Abu-Arish et al., 2015). The present study found that the clusters aggregate into ceramide-rich platforms during secretagogue stimulation. The mechanisms responsible for CFTR recruitment and retention in both types of sphingolipid-rich microdomains, i.e., sphingomyelin-rich lipid rafts and ceramide-rich platforms, are not known. Non-specific partitioning driven by differences in lipid composition probably contribute, especially for ceramide-rich platforms; however, specific protein–protein interactions may also be involved. CFTR binds to NHERF1 (Haggie et al., 2004; Bates et al., 2006a) and filamin A (Thelin et al., 2007), scaffold proteins that tether membrane proteins to the cytoskeleton. Single particle tracking studies showed that CFTR interaction with the PDZ (post synaptic density 95, disc large 1, zonula occludens 1) domains of NHERF1 nearly immobilizes CFTR (Bates et al., 2006a; Haggie et al., 2006). This was further suggested by incomplete fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (Haggie et al., 2004; Bates et al., 2006a) and by a fivefold faster effective diffusion coefficient calculated by ICS when the CFTR-NHERF interaction was disrupted by adding a polyhistidine tail to the C terminus of CFTR (Bates et al., 2006a,b). If scaffold proteins such as NHERF1 are themselves targeted to rafts or platforms, their interactions with CFTR could promote its recruitment or retention. Indeed, NHERF1 binds to cholesterol in artificial membrane vesicles (Sheng et al., 2012). Further studies are needed to establish if CFTR localization in rafts and platforms is enhanced by interactions with other proteins.

Another unexpected result was the colocalization of CFTR clusters with motile cilia and the ciliogenesis marker centrin2. The physiological significance of this distribution remains to be established. CFTR clusters are observed on CFBE cells that lack cilia; therefore, clustering does not depend on ability to form cilia. Conversely, ciliary function does not require CFTR expression, as most studies indicate that ciliary beat frequency is normal in CF cells (Rutland and Cole, 1981). However, ciliary beat frequency is only one measure of ciliary function, and CFTR may have more subtle effects. It is also possible that CFTR forms clusters wherever a lipid raft is available and is colocalized with cilia simply because it is embedded in lipid raft-like microdomains (Emmer et al., 2010).

The present results confirm that CFTR exists in two distinct populations having different effective diffusion coefficients (Abu-Arish et al., 2015). The punctate fluorescence of CFTR clusters, the cholesterol dependence of the slow component (Dmicro), and the plateau in the mean squared displacement curve (Dmicroτ − τ) all indicate confinement of the slow population in rafts with dimensions below the resolution limit of the light microscope (Abu-Arish et al., 2015). The slow component is due to movements within membrane microdomains (rafts and platforms), whereas the fast component corresponds to diffusion both within and between microdomains (Pandzic, 2013; Abu-Arish et al., 2015). Since Dmacro reports diffusion in both microdomains and the lipid bilayer, increases in both Dmicro and Dmacro by COase is consistent with slower diffusion within lipid rafts compared with the bulk bilayer (Abu-Arish et al., 2015).

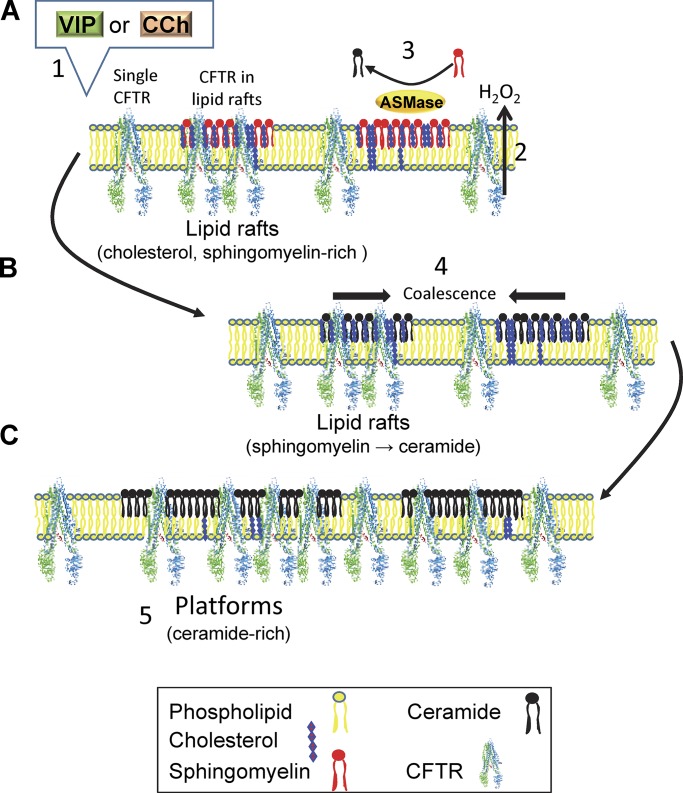

Activation of ASMase leads to formation of ceramides in lipid rafts, which causes the rafts to coalesce spontaneously into platforms due to intermolecular hydrogen bonding (Shah et al., 1995; Cremesti et al., 2002; Grassmé et al., 2002, 2003, 2005, 2007; Johnston and Johnston, 2008; Becker et al., 2010; Stancevic and Kolesnick, 2010). Ceramide formation also leads to displacement of cholesterol and caveolin-1 from microdomains (Yu et al., 2005), which is expected to further reduce lipid lateral mobility and viscosity (Kahya et al., 2003). The decrease in Dmicro and increase in the confined CFTR population fraction fmicro during secretagogue stimulation are consistent with ASMase activation and the effects of sphingomyelinase on other proteins. For example, treating HeLa cells with sphingomyelinase increases total ceramide levels sevenfold and reduces CD4 lateral mobility by fourfold (Finnegan et al., 2007), and exposing monocytes to sphingomyelinase reduces integrin receptor diffusion coefficients by twofold (Eich et al., 2016). Fig. 8, A–C, shows a cartoon summarizing the behavior of CFTR in pHBEs during stimulation by VIP and CCh. In this model, we propose that binding of VIP and CCh to their cognate G-protein coupled receptors leads to cellular release of an oxidant. The oxidant is probably H2O2 produced by dual oxidases rather than superoxide O2−⋅, since DUOX1 and DUOX2 are expressed at 1,000-fold higher levels than NADPH oxidases Nox1–5 (Schwarzer et al., 2004; Fischer, 2009). In this model, ASMase present on the surface of lipid rafts (this study) is activated by H2O2 oxidation of its C-terminal cysteine (Qiu et al., 2003). ASMase catalyzes cleavage of phosphocholine from sphingomyelin in the lipid raft to which it is bound, forming ceramide. The accumulation of ceramide in CFTR-containing lipid rafts leads to their fusion into large platforms similar to those described previously under pathological conditions. Platforms help stabilize CFTR at the cell surface, increasing its abundance in the plasma membrane and the Cl− conductance elicited during stimulation.

Figure 8.

Cartoon summarizing secretagogue-induced partitioning of CFTR into membrane microdomains. (A) VIP and CCh stimulate extracellular ASMase activity on lipid rafts, most likely through activation of their G protein–coupled receptors and autocrine release of H2O2. (B) Oxidation and activation of ASMase leads to sphingomyelin hydrolysis to phosphocholine and ceramide. The accumulation of ceramide in CFTR-containing lipid rafts causes them to fuse. (C) Fusion leads to the formation of large, ceramide-rich platforms that increase CFTR surface stability and functional expression.

In this study, we examined CFTR accumulation at the plasma membrane because it is known from previous studies that VIP inhibits CFTR retrieval from the plasma membrane, and this contributes to the secretory response in Calu-3 cells (Becq et al., 1999; Chappe et al., 2004, 2008; Qu et al., 2011). The latter might be explained by spatial isolation of CFTR in platforms from endocytosis machinery or reduced membrane invagination due to the rigidity of tightly packed ceramide acyl chains in platforms (Pinto et al., 2013). Ceramides are implicated in endocytosis as ceramide synthase (Cers) 2–null mice have reduced clathrin–mediated endocytosis, an effect that can be explained by a fourfold increase in reactive oxygen species production when very long chain ceramide (VLCC) levels are reduced (Volpert et al., 2017). In addition to increasing CFTR abundance at the cell surface, secretagogue-induced partitioning into microdomains may modulate its regulation and the pharmacological rescue of mutant CFTR by corrector drugs used to treat CF. Sequestering of CFTR into lipid microdomains may bring it into proximity with different cohort of regulatory proteins in a macromolecular complex (Li and Naren, 2010) if proteins are differentially excluded into platforms as described for caveolin. Platforms containing CFTR have also been linked to inflammation and mucosal immunity and are likely to serve other functions besides enhancing Cl− transport. We found that platforms can form in CF cells that lack CFTR at the cell surface; therefore, CFTR does not drive the formation of platforms and may be one of many proteins that become incorporated into platforms when the rafts fuse. Nevertheless, CFTR may modulate the lipid raft abundance and platform formation indirectly, for example, through its effects on cholesterol trafficking and distribution (Gentzsch et al., 2007; White et al., 2007; Fang et al., 2010).

ASMase plays an essential role in forming platforms that contain CFTR as they are prevented by pretreating cells with the functional ASMase inhibitor Ami. It has been suggested recently that Ami and other cationic amphiphilic drugs may be more selective for ASMase than was previously thought, and current efforts aim at developing more potent derivatives (Rhein et al., 2018). However, the mode of ASMase activation and perhaps the enzyme itself may differ from other cell types, where it is known to be activated intracellularly and rapidly translocated from lysosomes onto the plasma membrane during stimulation (Grassme et al., 2001; Zeidan and Hannun, 2007). In pHBE cells, we found no evidence for increased delivery of ASMase to the cell surface during VIP stimulation. ASMase was colocalized with CFTR clusters and cilia under basal conditions and aggregated into platforms along with CFTR and centrin2 during VIP stimulation. Increases in Ami-sensitive ASMase activity were measured using a biochemical assay 30 and 60 min after VIP stimulation despite a 33% decrease in ASMase immunostaining at the plasma membrane. An intriguing possibility is that platforms in pHBEs are produced by the secreted, complex-glycosylated form of ASMase rather than a lysosomal form (Jenkins et al., 2009). Regardless, the enzyme responsible is ASMase as it was recognized by an antibody that distinguishes it from neutral sphingomyelinase. In summary, the platforms induced by secretagogues have some similarities to those that have been described under pathological conditions, but differ in the mode of ASMase activation and their nonapoptotic signaling.

The activation of ASMase that is bound to the plasma membrane presumably requires autocrine signaling. The present results suggest that this signal may be an oxidant such as H2O2, as this would be compatible with reports that intracellular ASMase can be activated by oxidation before its translocation onto the cell surface (Dumitru and Gulbins, 2006; Li et al., 2012). Indeed, oxidation of cysteine 629 at the C terminus of ASMase increases its activity by fivefold (Qiu et al., 2003). Exogenous H2O2 increases ceramide levels in intact tracheobronchial cells and in isolated membranes, although ceramide production was ascribed to neutral Mg2+-dependent sphingomyelinase (Goldkorn et al., 1998), which is located on the intracellular surface of the plasma membrane. We found that secretagogue activation of ASMase and platform formation on pHBE cells are prevented by extracellular MESNA, a relatively mild reducing agent that is membrane impermeant. Such inhibition is consistent with autocrine redox activation of ASMase but could have other explanations, since ASMase has disulfide bridges that could be disrupted by MESNA. If VIP and CCh activate ASMase by autocrine redox signaling as proposed, it is probably mediated by H2O2 generated by DUOX1 or DUOX2, the predominant NADPH oxidases in airway epithelial cells (Fischer, 2009).

Ceramide-rich platforms are particularly interesting in the context of CF because ceramides and other lipids are altered in CF cells. VLCCs such as C24:0 that are considered anti-inflammatory are decreased in CF patients and CFTR knock-out mice (Guilbault et al., 2009), while proinflammatory long chain ceramides (LCCs; e.g., C16:0) are increased (Teichgräber et al., 2008). The synthetic retinoid derivative fenretinide is reported to correct the imbalance between VLCCs and LCCs in CFTR-null mice (Guilbault et al., 2008). A formulation of fenretinide (LAU-7B; Laurent Pharma) is presently entering a phase 2 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial to evaluate its safety and efficacy (APPLAUD, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03265288). Fenretinide down-regulates expression of the ER enzyme Cers5, which increases synthesis of VLCCs by Cers2:Cers5 heterodimers relative to synthesis of LCCs by Cers5:Cers5 homodimers, thereby correcting the ceramide imbalance (Garić et al., 2017). Although fenretinide targets de novo ceramide synthesis at the endoplasmic reticulum, it could lead to increased VLCC formation by ASMase (the ceramide salvage pathway) indirectly through elevated levels of very long chain sphingomyelin in the plasma membrane, a reaction catalyzed by sphingomyelin synthase 2 (Aureli et al., 2016). It will be interesting to investigate whether the sphingolipid imbalance influences the properties and functions of ceramide-rich platforms in CF.

In summary, the present results suggest a novel mechanism for the physiological regulation of plasma membrane proteins and lipids. The significance of CFTR association with motile cilia in bronchial epithelial cells remains to be established; however, its distribution and lateral mobility are regulated by secretagogues, likely through autocrine oxidation of extracellular ASMase that is colocalized with CFTR clusters in lipid rafts under resting conditions. The formation of ceramide-rich platforms in response to physiological secretagogues would enhance CFTR–mediated secretion and may have other functions related to cell signaling, inflammation, and mucosal immunity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Biobank of respiratory tissues of the Centre de recherche du CHUM (Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal), the Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal, and the Respiratory Health Network of Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé for tissue samples, and Julie Goepp, Carolina Martini, and Elizabeth Matthes of the Primary Airway Cell Biobank for pHBE isolation. We also thank Yishan Luo for help with CSB.

A. Abu-Arish received fellowships from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Cystic Fibrosis Canada, and the Groupe de Recherche Axé sur la Structure des Protéins. The work was funded by grants from the U.S. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (HANRAH17G0) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PJT-156183) to J.W. Hanrahan, and a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2017-05005) to P.W. Wiseman. J.W. Hanrahan and P.W. Wiseman were members of the Groupe d’Étude des Protéines Membranaires.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: A. Abu-Arish and J.W. Hanrahan designed the research, A. Abu-Arish, D. Kim, and H.W. Tseng collected the data, E. Pandžić, A. Abu-Arish, and P.W. Wiseman developed the analytical methods, A. Abu-Arish analyzed the data, and A. Abu-Arish and J.W. Hanrahan wrote the paper. All authors edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Richard W. Aldrich served as editor.

References

- Abu-Arish A., Pandzic E., Goepp J., Matthes E., Hanrahan J.W., and Wiseman P.W.. 2015. Cholesterol modulates CFTR confinement in the plasma membrane of primary epithelial cells. Biophys. J. 109:85–94. 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso A., and Goñi F.M.. 2018. The Physical Properties of Ceramides in Membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 47:633–654. 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070317-033309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aureli M., Schiumarini D., Loberto N., Bassi R., Tamanini A., Mancini G., Tironi M., Munari S., Cabrini G., Dechecchi M.C., and Sonnino S.. 2016. Unravelling the role of sphingolipids in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 200:94–103. 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates I.R., Hébert B., Luo Y., Liao J., Bachir A.I., Kolin D.L., Wiseman P.W., and Hanrahan J.W.. 2006a Membrane lateral diffusion and capture of CFTR within transient confinement zones. Biophys. J. 91:1046–1058. 10.1529/biophysj.106.084830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates I.R., Wiseman P.W., and Hanrahan J.W.. 2006b Investigating membrane protein dynamics in living cells. Biochem. Cell Biol. 84:825–831. 10.1139/o06-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K.A., Grassme H., Zhang Y., and Gulbins E.. 2010. Ceramide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections and cystic fibrosis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 26:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becq F., Mettey Y., Gray M.A., Galietta L.J.V., Dormer R.L., Merten M., Métayé T., Chappe V., Marvingt-Mounir C., Zegarra-Moran O., et al. 1999. Development of substituted Benzo[c]quinolizinium compounds as novel activators of the cystic fibrosis chloride channel. J. Biol. Chem. 274:27415–27425. 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billet A., and Hanrahan J.W.. 2013. The secret life of CFTR as a calcium-activated chloride channel. J. Physiol. 591:5273–5278. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.261909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billet A., Luo Y., Balghi H., and Hanrahan J.W.. 2013. Role of tyrosine phosphorylation in the muscarinic activation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). J. Biol. Chem. 288:21815–21823. 10.1074/jbc.M113.479360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollinger C.R., Teichgräber V., and Gulbins E.. 2005. Ceramide-enriched membrane domains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1746:284–294. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappe F., Loewen M.E., Hanrahan J.W., and Chappe V.. 2008. Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide Increases Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Levels in the Apical Membrane of Calu-3 Cells through a Protein Kinase C-Dependent Mechanism. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 327:226–238. 10.1124/jpet.108.141143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappe V., Hinkson D.A., Howell L.D., Evagelidis A., Liao J., Chang X.-B., Riordan J.R., and Hanrahan J.W.. 2004. Stimulatory and inhibitory protein kinase C consensus sequences regulate the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:390–395. 10.1073/pnas.0303411101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremesti A.E., Goni F.M., and Kolesnick R.. 2002. Role of sphingomyelinase and ceramide in modulating rafts: do biophysical properties determine biologic outcome? FEBS Lett. 531:47–53. 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03489-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dérand R., Montoni A., Bulteau-Pignoux L., Janet T., Moreau B., Muller J.-M., and Becq F.. 2004. Activation of VPAC1 receptors by VIP and PACAP-27 in human bronchial epithelial cells induces CFTR-dependent chloride secretion. Br. J. Pharmacol. 141:698–708. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmsathaphorn K., Mandel K.G., Masui H., and McRoberts J.A.. 1985. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-induced chloride secretion by a colonic epithelial cell line. Direct participation of a basolaterally localized Na+,K+,Cl- cotransport system. J. Clin. Invest. 75:462–471. 10.1172/JCI111721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudez T., Borot F., Huang S., Kwak B.R., Bacchetta M., Ollero M., Stanton B.A., and Chanson M.. 2008. CFTR in a lipid raft-TNFR1 complex modulates gap junctional intercellular communication and IL-8 secretion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1783:779–788. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitru C.A., and Gulbins E.. 2006. TRAIL activates acid sphingomyelinase via a redox mechanism and releases ceramide to trigger apoptosis. Oncogene. 25:5612–5625. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eich C., Manzo C., de Keijzer S., Bakker G.J., Reinieren-Beeren I., García-Parajo M.F., and Cambi A.. 2016. Changes in membrane sphingolipid composition modulate dynamics and adhesion of integrin nanoclusters. Sci. Rep. 6:20693 10.1038/srep20693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmer B.T., Maric D., and Engman D.M.. 2010. Molecular mechanisms of protein and lipid targeting to ciliary membranes. J. Cell Sci. 123:529–536. 10.1242/jcs.062968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang D., West R.H., Manson M.E., Ruddy J., Jiang D., Previs S.F., Sonawane N.D., Burgess J.D., and Kelley T.J.. 2010. Increased plasma membrane cholesterol in cystic fibrosis cells correlates with CFTR genotype and depends on de novo cholesterol synthesis. Respir. Res. 11:61 10.1186/1465-9921-11-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan C.M., Rawat S.S., Cho E.H., Guiffre D.L., Lockett S., Merrill A.H. Jr., and Blumenthal R.. 2007. Sphingomyelinase restricts the lateral diffusion of CD4 and inhibits human immunodeficiency virus fusion. J. Virol. 81:5294–5304. 10.1128/JVI.02553-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H. 2009. Mechanisms and function of DUOX in epithelia of the lung. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11:2453–2465. 10.1089/ars.2009.2558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frizzell R.A., and Hanrahan J.W.. 2012. Physiology of chloride and fluid secretion. In Cystic Fibrosis: Molecular Basis, Physiological Changes, and Therapeutic Strategies. Vol. 2 Riordan J.R., Boucher R.C., and Quinton P.M., editors. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor: a009563 Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulcher M.L., Gabriel S., Burns K.A., Yankaskas J.R., and Randell S.H.. 2005. Well-differentiated human airway epithelial cell cultures. Methods Mol. Med. 107:183–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garić D., De Sanctis J.B., Wojewodka G., Houle D., Cupri S., Abu-Arish A., Hanrahan J.W., Hajduch M., Matouk E., and Radzioch D.. 2017. Fenretinide differentially modulates the levels of long- and very long-chain ceramides by downregulating Cers5 enzyme: evidence from bench to bedside. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.). 95:1053–1064. 10.1007/s00109-017-1564-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentzsch M., Choudhury A., Chang X.B., Pagano R.E., and Riordan J.R.. 2007. Misassembled mutant DeltaF508 CFTR in the distal secretory pathway alters cellular lipid trafficking. J. Cell Sci. 120:447–455. 10.1242/jcs.03350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldkorn T., Balaban N., Shannon M., Chea V., Matsukuma K., Gilchrist D., Wang H., and Chan C.. 1998. H2O2 acts on cellular membranes to generate ceramide signaling and initiate apoptosis in tracheobronchial epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 111:3209–3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassme H., Jekle A., Riehle A., Schwarz H., Berger J., Sandhoff K., Kolesnick R., and Gulbins E.. 2001. CD95 signaling via ceramide-rich membrane rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20589–20596. 10.1074/jbc.M101207200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassmé H., Bock J., Kun J., and Gulbins E.. 2002. Clustering of CD40 ligand is required to form a functional contact with CD40. J. Biol. Chem. 277:30289–30299. 10.1074/jbc.M200494200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassmé H., Jendrossek V., Riehle A., von Kürthy G., Berger J., Schwarz H., Weller M., Kolesnick R., and Gulbins E.. 2003. Host defense against Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires ceramide-rich membrane rafts. Nat. Med. 9:322–330. 10.1038/nm823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassmé H., Riehle A., Wilker B., and Gulbins E.. 2005. Rhinoviruses infect human epithelial cells via ceramide-enriched membrane platforms. J. Biol. Chem. 280:26256–26262. 10.1074/jbc.M500835200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassmé H., Riethmüller J., and Gulbins E.. 2007. Biological aspects of ceramide-enriched membrane domains. Prog. Lipid Res. 46:161–170. 10.1016/j.plipres.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groneberg D.A., Hartmann P., Dinh Q.T., and Fischer A.. 2001. Expression and distribution of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide receptor VPAC(2) mRNA in human airways. Lab. Invest. 81:749–755. 10.1038/labinvest.3780283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilbault C., De Sanctis J.B., Wojewodka G., Saeed Z., Lachance C., Skinner T.A., Vilela R.M., Kubow S., Lands L.C., Hajduch M., et al. 2008. Fenretinide corrects newly found ceramide deficiency in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 38:47–56. 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0036OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilbault C., Wojewodka G., Saeed Z., Hajduch M., Matouk E., De Sanctis J.B., and Radzioch D.. 2009. Cystic fibrosis fatty acid imbalance is linked to ceramide deficiency and corrected by fenretinide. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 41:100–106. 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0279OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggie P.M., Stanton B.A., and Verkman A.S.. 2004. Increased diffusional mobility of CFTR at the plasma membrane after deletion of its C-terminal PDZ binding motif. J. Biol. Chem. 279:5494–5500. 10.1074/jbc.M312445200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggie P.M., Kim J.K., Lukacs G.L., and Verkman A.S.. 2006. Tracking of quantum dot-labeled CFTR shows near immobilization by C-terminal PDZ interactions. Mol. Biol. Cell. 17:4937–4945. 10.1091/mbc.e06-08-0670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herawati E., Taniguchi D., Kanoh H., Tateishi K., Ishihara S., and Tsukita S.. 2016. Multiciliated cell basal bodies align in stereotypical patterns coordinated by the apical cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 214:571–586. 10.1083/jcb.201601023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]