Abstract

Background

Musculoskeletal pain in youth is common but little is known about the influence of the number of pain sites on pain characteristics. The objective of this study was to compare pain characteristics, quality of life, sleep, sport participation between adolescents without pain, those with single site pain, and those with multi-site pain and investigate the relationship between pain duration and number of pain sites.

Methods

An online survey was sent via email to 7177 possible middle- and high-school students. The students completed a survey containing questions about their pain (including location, duration, intensity, frequency), health-related quality of life, sleep quantity and quality, and sports participation. Quantitative variables were analysed with one-way ANOVAs or t-tests and qualitative variables were analysed with Pearson Chi-squared tests. Relationships were investigated with a Pearson Correlation.

Results

Of the respondents (n = 1021), 52.9% reported no pain, 17.2% reported pain in a single-site, and 29.9% reported pain in multiple sites. Those with multi-site pain reported significantly lower quality of life than both pain-free youth (p < 0.001) and those with single-site pain (p < 0.001); those with single-site pain had lower quality of life than pain-free youth (p < 0.001). Those with pain reported worse sleep than those without pain (P < 0.05). No differences in sport participation were found (p > 0.10). Those with multi-site pain reported greater intensity (p = 0.005) and duration (p < 0.001) than those with single-site pain. A positive, moderate, and significant correlation (r = 0.437, p < 0.001) was found between the pain duration and number of pain sites.

Conclusions

A large percentage of youth experience regular pain that affects their self-reported quality of life and sleep, with greater effects in those with multi-site pain.

Keywords: EQ-5D, Adolescents, Children

Background

Musculoskeletal (MSK) pain is a common complaint in adolescents. Approximately one third of adolescents experience regular (at least monthly) MSK pain [1]. Although the estimates vary between studies and populations, sports active adolescents appear to have the highest prevalence of pain complaints [2]. A concern is that adolescent pain complaints are not always transient, and 50% will continue to experience pain even years later [3]. Adolescent MSK pain is a public health concern, as it is the largest contributor to years lived with disability, which increases rapidly during the transition from childhood into adolescence [4]. The presence of persistent pain during adolescence can have a negative effect on physical activity, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), anxiety, school attendance, participation in hobbies and social activities, and can cause disturbances in appetite, sleep and mental health [5–7].

The presentation of MSK pain complaints in adolescents vary considerably, ranging from localised pain with a short duration [8], all the way to wide-spread multi-site pain [9], and can last through to adulthood [10]. Multi-site pain is common, with one in three of all adolescents (12–19 years) reporting pain in more than one location [11]. A greater number of pain sites appear to have a larger impact on physical and social activity, relative to localised pain [12]. Similarly, data have shown a link between multi-site pain during adolescence and future mental health disorders [13]. Despite the commonality of multi-site pain, the majority of previous research has focused on specific pain locations, such as the knee or back [14–16], neglecting the presence of co-occurring pain sites. However, the number of pain sites, may be of particular importance to investigate, as pain in multiple locations may indicate a progression of long-standing pain [17] and be indicative of a poorer prognosis [18].

Furthermore, adolescents’ pain experience may be modulated by lifestyle factors (sports participation, sleep) and psychosocial factors (quality of life). These factors represent potentially modifiable factors, and the question remains whether these factors are differentially associated with the number of pain sites or the location of MSK pain. Understanding their association to the adolescent’s pain experience may present a way to gain insight into the determinants of their pain experience and inform suitable treatment target.

Methods

This paper aims to 1) compare pain characteristics (intensity, duration), quality of life, sleep, sport participation between adolescents without pain, those with single site pain, and those with multi-site pain and 2) investigate the relationship between pain duration and number of pain sites.

Study design and recruitment

This cross-sectional survey study was conducted in January of 2017. The reporting of the study follow the STROBE guidelines [19]. This survey was conducted in a suburban school district in the Midwestern United States. The school district approved this study, as did the University’s Institutional Review Board. All middle- and high-school students (ages 10–18) and parents were sent information about this study and were given the opportunity to request that they be removed from the recruitment email list. Per parental request, a total of 33 potential participants were removed from the survey pool. A link to the final survey was sent to 7177 total students. Participants were able to respond to the link and indicate that they were not interested in participating in the study. Regardless of participation, each respondent was entered into a drawing for a $50 gift card.

Survey

The survey was designed to explore pain characteristics, HRQoL, sleep and sports participation. We used specific questions within these four domains, drawn from previous (population based) studies conducted in adolescent populations [20–22]. The survey was constructed in Google forms.

Pain

Participants were asked to indicate if they had experienced pain in the previous six months in any of nine predefined locations, and if they were currently experiencing pain in these locations. If current pain was reported, then additional variables of location, age of onset (i.e. duration) and, frequency of pain, average and worst pain (measured on a numerical rating scale from 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain in the last week and 10 being the worst pain imaginable). Participants were asked to report their average and worst pain over the last week. Participants were then asked about the location of pain with the options being neck, upper back, lower back, hips, knees, ankles/feet, shoulders, elbows, and wrists/hands. Participants were asked to report age when the pain first started, which was used to calculate pain duration (in years). The frequency of pain was assessed using the following options “Almost Daily”, “Several times a week”, “Weekly”, “Monthly”, and “Rarely”.

Health related quality of life

Health-related quality of life was assessed with the EuroQol Group 5-Dimensional 3 levels Self-Report Questionnaire (EQ-5D-3 L). The EQ-5D is a general health questionnaire where participants report the problems (none, some or a lot) in the areas of walking about, washing/dressing, doing usual activates, pain/discomfort, and feelings of worry, sadness, or unhappiness. To calculate the index score we used the time trade-off method specific for the US population [23]. The index score for EQ-5D ranges from − 0.59 to 1.00, with higher scores indicate better quality of life.

Sleep

Sleep quality was assessed using methods described by Auvinen et al. [21]. Participants were asked “How well does each statement apply at present, or over the past 6 months?” (1) “I have nightmares”, (2) “I am too tired” and (3) “I have sleep problems”. Participants could respond to these statements as “Never”, “To some extent or sometimes”, and “Very much or often”. Sleep quantity (average hours/night) was assessed via participants self-report [22]. Based on these qualitative and quantitative responses, all participants were categorized as having (1) sufficient sleep (8–9 h per day and no nightmares, tiredness or general sleep problems), (2) intermediate sleep (7 or 10 or more h per day, or having nightmares, tiredness or general sleep problems to some extent or sometimes) or (3) insufficient sleep (6 h or less per day, or often having nightmares, tiredness, or general sleep problems) [21].

Sports participation

Participants were asked if they participated in sports (yes/no), and if yes, the number of days and hours of sport participation per week. Weekly sports participation was computed by multiplying the number of days per week of sports participation by the average daily hours of sports participation [22]. Participants self-reported sex, age, height, and mass. Height and mass were used to calculate BMI (kg/m2).

Data analyses

For this study, participants were included in the single site-pain group if they described current pain in one site, irrespective of location on the body. If they reported pain in more than one location, they were included in the multi-site pain group. The no-pain (control) group was defined as youth reporting no pain in the previous six months. Those who reported no current pain, but pain in the last six months were excluded from the analysis (n = 106).

To compare quantitative variables (age, height, weight, BMI, EQ-5D index scores, sleep hours, sports participation hours and HRQoL) among groups (single-site versus multi-site versus control), one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were utilized. Pairwise comparisons were completed using Tukey tests for significant main effects. Pearson chi-squared tests were used for categorical and dichotomous variables (sex, pain frequency, sleep quality, sports participation). Pairwise comparisons were performed using chi-squared tests with Bonferroni corrections. Comparisons of pain intensity (average, worst) and duration were performed with independent t-tests. To investigate the relationship between pain duration (pain site with longest duration) and the total number of pain sites, a Pearson Correlation was used. Pearson correlation magnitudes were interpreted as small (0–0.3), moderate (0.3–0.5), large (0.5–0.7), and very large (0.7–1.0) [24]. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

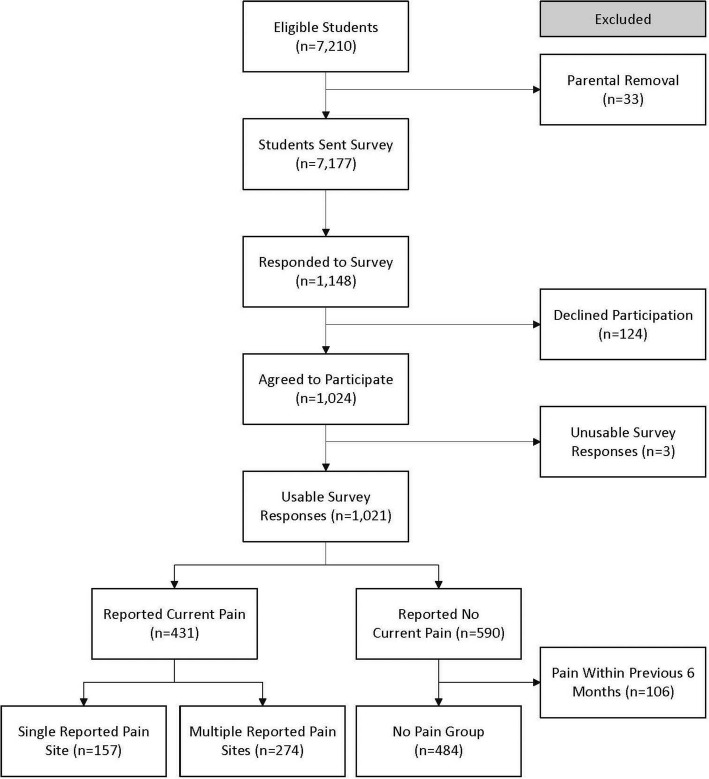

A total of 1148 (16%) responded to the survey, with 1024 participants volunteering for the study (14.3%). Three participants’ data was unusable due to nonsensical responses and was removed. Of the 1021 participants, 431 (42.2%) reported current pain. Those who had no current pain but reported pain in the previous 6 months were excluded from this analysis (n = 106, 10.4%). Final group allocations (out of n = 915) were 484 (52.9%) controls, 157 (17.2%) with single-site pain, and 274 (29.9%) with multi-site pain (Fig. 1). The multi-site group had a median ± IQR of 3 ± 2 (range: 2–9) pain sites.

Fig. 1.

STROBE Flow Chart

Our sample contained a significantly greater proportion of girls than boys in all pain groups (67.3% female, p < 0.001); however, pairwise comparisons did not demonstrate significant differences for sex between any of the groups. Groups were not significantly different in terms of mean age (p = 0.050), height (p = 0.686), weight (p = 0.783), or BMI (p = 0.702). Participant characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and comparisons among pain groups

| No Pain (n = 484) | Single Site Pain (n = 157) | Multi-Site Pain (n = 274) | Main Effect | NPvSSP | NPvMSP | SSPvMSP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, N (%) | Girls: 302 (62.8%) | Girls: 111 (70.3%) | Girls: 216 (78.5%) | p < 0.001 | ns | ns | ns |

| Boys: 179 (37.2%) | Boys: 47 (29.7%) | Boys: 59 (21.5%) | |||||

| Age, (years) | 14.6 ± 2.0 (14.5–14.8) | 15.0 ± 1.9 (14.7–15.3) | 14.9 ± 1.9 (14.7–15.2) | p = 0.050 | na | na | na |

| Height (m) | 1.65 ± 0.14 (1.63–1.66) | 1.66 ± 0.11 (1.64–1.67) | 1.65 ± 0.12 (1.64–1.66) | p = 0.686 | na | na | na |

| Weight (kg) | 61.2 ± 18.3 (59.6–62.9) | 62.0 ± 16.0 (59.5–64.5) | 62.1 ± 15.7 (60.2–64.0) | p = 0.783 | na | na | na |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.5 ± 5.6 (21.9–23.0) | 22.7 ± 5.8 (21.8–23.7) | 22.8 ± 5.2 (22.2–23.4) | p = 0.702 | na | na | na |

All variables reported as mean ± standard deviation (95% confidence interval), except for sex

NP No Pain, SSP Single-Site Pain, MSP Multi-Site Pain, ns not significant, na not performed

There was a significant difference between groups in health related quality of life (EQ-5D scores) (p < 0.001). The no pain group had significantly higher health related quality of life compared to those with single-site pain (mean difference 0.073 95% CI = 0.035–0.110, p < 0.001) and compared to the multi-site pain group (mean difference 0.166 95% CI = 0.135–0.197, p < 0.001). Those with multi-site pain has significantly lower quality of life compare to those with single site-pain (mean difference 0.094 95% CI = 0.052–0.134, p < 0.001). All quality of life data can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality of life, sleep, and sports participation among pain groups

| No Pain (n = 484) | Single Site Pain (n = 157) | Multi-Site Pain (n = 274) | Main Effect | NPvSSP | NPvMSP | SSPvMSP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ 5D Index Score | 0.834 ± 0.15 (0.820–0.847) | 0.761 ± 0.17 (0.734–0.788) | 0.667 ± 0.21 (0.642–0.693) | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| Sleep Hours | 7.42 ± 1.4 (7.29–7.54) | 7.07 ± 1.6 (6.82–7.31) | 6.75 ± 1.6 (7.05–7.26) | p < 0.001 | p = 0.041 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.099 |

| Sports Participation, N Yes (%) | 317 (65.9%) | 118 (74.2%) | 195 (70.9%) | p = 0.099 | na | na | na |

| Sports Hours/Week | 10.2 ± 6.9 (9.4–10.9) | 11.2 ± 6.7 (10.0–12.5) | 10.9 ± 8.8 (9.6–12.2) | p = 0.349 | na | na | na |

All variables reported as mean ± standard deviation (95% confidence interval), except for sports participation

NP No Pain, SSP Single-Site Pain, MSP Multi-Site Pain, na not performed

Sleep quantity was significantly different among groups (p < 0.001; Table 2), with pairwise comparisons showing significantly reduced sleep in those with single-site pain (mean difference = 0.35 h, 95% CI = 0.01–0.69, p = 0.041) and multi-site pain (mean difference = 0.67 h, 95% CI = 0.39–0.95, p < 0.001) compared to the no pain group. There was no difference between those with single- versus multi-site pain (mean difference = 0.32 h, 95% CI = -0.05–0.69, p = 0.099). There was a significant difference between groups in the proportion with sufficient, intermediate, or insufficient sleep (p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons demonstrated that youth with multi-site pain had a significantly greater proportion of intermediate and insufficient sleep quality compared to no pain (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively) and single site pain (p = 0.004 and p = 0.004, respectively) groups. Sleep data is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sleep categories between pain groups

| No Pain (n = 484) | Single Site Pain (n = 157) | Multi-Site Pain (n = 274) | Main Effect | NPvSSP | NPvMSP | SSPvMSP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sufficient | 23 (4.9%) | 3 (1.9%) | 5 (1.8%) | p < 0.001 | ns | ns | ns |

| Intermediate | 275 (58.0%) | 81 (51.9%) | 98 (36.0%) | ns | p < 0.001 | p = 0.004 | |

| Insufficient | 176 (37.1%) | 72 (46.2%) | 169 (62.1%) | ns | p < 0.001 | p = 0.004 |

NP No Pain, SSP Single-Site Pain, MSP Multi-Site Pain, ns not significant

No significant differences among the proportion of those participating in sports were found (p = 0.099). Significant differences among groups were also not found for sport participation hours per week (p = 0.349). All sport participation data can be found in Table 2.

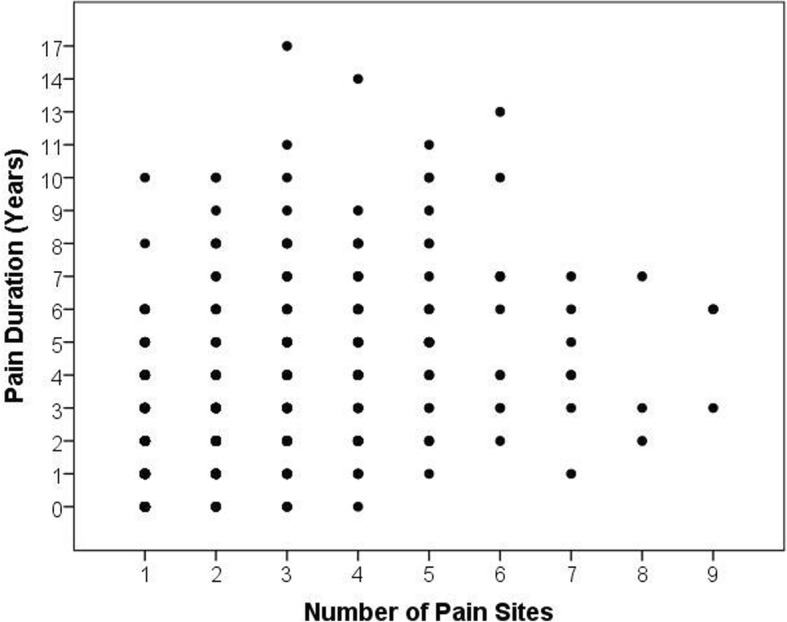

Average and worst pain (i.e. intensity) in the previous week was significantly (p = 0.005 and p = 0.005, respectively) greater in those with multi-site pain (4.34 ± 2.09 and 6.66 ± 2.29, respectively) compared to single site pain (3.76 ± 1.90 and 6.00 ± 2.16, respectively). The knee, lower back, and ankle were the most common pain sites for both single site pain and multi-site pain groups (Table 4). There were no significant differences (p = 0.065) in pain frequency between pain groups (Table 5). Duration of pain was also significantly greater (p < 0.001) in youth with multi-site pain (3.90 ± 2.75 years) compared to those with single site pain (1.78 ± 1.84 years). A positive, moderate, and significant correlation (r = 0.437, p < 0.001) was found between the pain duration and number of pain sites (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Pain location frequencies for pain groups, N(%)

| Single Site Pain | Multi-Site Pain | |

|---|---|---|

| Knee | 39 (24.8%) | 157 (17.1%) |

| Lower Back | 31 (19.7%) | 149 (16.0%) |

| Ankle | 28 (17.8%) | 112 (12.2%) |

| Wrist/Hand | 18 (11.5%) | 90 (9.8%) |

| Neck | 12 (7.6%) | 102 (11.1%) |

| Shoulder | 10 (6.4%) | 93 (10.1%) |

| Hip | 9 (5.7%) | 92 (10.0%) |

| Upper Back | 8 (5.1%) | 106 (11.5%) |

| Elbow | 2 (1.3%) | 19 (2.1%) |

Table 5.

Frequency (%)of pain for pain groups

| Single Site Pain | Multi-Site Pain | |

|---|---|---|

| Almost Daily | 29.4% | 42.0% |

| Several Times Per Week | 25.5% | 24.1% |

| Weekly | 23.5% | 15.3% |

| Monthly | 13.1% | 12.8% |

| Rarely | 8.5% | 5.8% |

Fig. 2.

Scatterplot of pain duration relative to the number of pain sites. A positive, moderate, and significant correlation (r = 0.437, p < 0.001) was found

Discussion

In this population based survey of adolescents, we found a high prevalence of pain, with knee pain being the most common. Those with MSK pain demonstrated poorer sleep quality and HRQoL, compared to those without pain. These assocoations were even stronger with those in pain in more than one location. Worryingly, a high proportion (nearly one third) reported pain in more than one location. This group of adolescents with multi-site pain may need particular focus, as in additon to poor sleep and HRQoL, they are characterized by high frequency and intensity of pain, compared to those with single-site pain. These factors have been indicated to increase the risk of a poor prognosis [5, 25].

This study confirms previous evidence indicating that knee pain is the single most common MSK pain location among adoelscents [11]. However the results indicate the commonality of multi-site in this population- nearly twice as many as those with pain in a single location. Perhaps unsurprisingly multisite pain was associated with a longer pain duration (despite no difference in age). This may suggest that having pain in one location is a risk factors for developing MSK pain in another location [26]. The high number of participants, and low HRQoL in this group underscores the need need for a paradigm shift away from looking at isolated pain complaints and to focus on how best to manage adolescents with pain in multiple locations.

Previously, in a population based sample of adolescents [27], those classified as having multi-site bodily pain (predominantly knee, back, head, stomach) are often females with a low HRQoL and lower sports participation than other pain patterns such as localized pain. These characteristics are similar in those with mulit-site pain in the current study. This may cause for concern, as having more multi-site and/or widespread pain [28–30], longer pain duration [28, 30], and pain intensity [29, 30] have all been associated with worse prognosis across a range of different MSK pain conditions, and in adolescents are associated with pain and functional limitations after 5 years study (Holden et al. in review, prog-paper). Further research should investigate if identifying these common profiles or characteristics early on can help identify the adolescents who are most in need of attention.

A high volume of sports participation has previously been linked to overuse pain and injury in youth [31, 32]. In general, injured youth completing more organized sports hours per week than those compared to those who were not injured [31]. The weekly hours of sports participation in our study (overall = 10.2 ± 6.9) are similar to levels previously reported (uninjured = 9.1 ± 6.3, injured = 11.2 ± 2.6) study [31]. However, we did not find differences in sports participation between groups. This difference could be attributed to the use of a diagnosed injury (both chronic and acute) vs self-reported pain (which can also be associated high sedentary time [33]) in our study. Future research should investigate the relationships among hours of sport participation, injury status, and chronic pain in this population, including non-linear relationships.

It has been proposed that adolescence is a critical developmental period in which small investments in health promotion, or ‘nudges’ in health behaviours can have impacts across the life-span [34, 35]. One critical health related phenomenon during this period is sleep. According to the National Sleep Foundation, adolescents need 8–9 h of sleep per night [36]. In our study, nearly 60% of the adolescents with multi-site pain reported insufficient sleep (6.75 h), which is a cause for concern as it is higher than 45% of the general youth population who get insufficient sleep, reported by the National Sleep Foundation [36]. Sleep and pain have a complex intertwining recipricol relationship- in the short term acute lack of sleep is associated with subsequent worse pain [37, 38], but in the longer term decreased sleep quantity and quality is an independant risk factors for both the onset and prognosis of pain [25, 39]. However, the lack of sleep these adolescents experience can go beyond pain and can have wider implications for health due to the association between sleep problems and psychological factors [40].

In a Danish sample, Rathleff et al. [11] found that single-site pain was twice as common as multi-site pain, but it is the reverse in this sample with multi-site being more common. The difference may be due to differences in the populations studied. Further due to the low response rate in the current study, it is unknown if this finding is as a result of response bias (i.e. those with more pain more likely to respond to questionnaire). Further the lower HRQoL in this study, with pain-free adolescents from the current study having similar values as those with pain from the Danish population. Overall, the HRQoL was low compared to other studies, also among those without pain. Perhaps this is linked to poor sleep, and associated psychological problems that may be expected, but this is speculative and future research is needed to understand this.

The response rate was low, but not deemed a major threat to the validity of our findings as this cross-sectional study aimed to compare pain characteristics (intensity, duration), quality of life, sleep, sport participation between adolescents those with single site pain, multi-site pain and those without pain, rather than estimate the prevalence of pain complaints. The difference in response rates between sexes seems consistent with females being more vigilant about pain and seeking medical care at a higher rate than males [41]. This study relied on self-reported data, similar to previous studies. This may cause unknown bias towards some the exposures we collected. However, as the adolescents where not aware of our main hypothesis, we expect this to equally affect all adolescents.

Conclusions

A large percentage of youth (10–18 years) experience regular pain that greatly reduces their self-reported quality of life and sleep quantity and quality. Those reporting multi-site pain report a greater reduction in quality of life and increased pain intensity and duration. The duration of pain is related to the number of pain sites, possibly demonstrating a rational for earlier intervention in those with single-site pain. Complaints of pain in youth should be disregarded with caution.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the School District of Waukesha, WI, USA, for their collaboration on this project.

Abbreviations

- EQ-5D

EuroQol Group 5-Dimensional 3 levels Self-Report Questionnaire

- HRQoL

Health-related quality of life

- MSK

Musculoskeletal

Authors’ contributions

DBJ collected, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manucript. MSR and SH were also major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors were involved in the design and planning of this study and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided from the Carroll University Faculty Development Grant Program.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Carroll University Institutional Review Board. Parents did not complete a written or verbal consent but they were given the opportunity to remove their child from the email list of who was sent the survey. Participants consented by completing the anonymous online questionnaire. The need for written consent was waived according to US regulations 45 CFR 46.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

David M. Bazett-Jones, Phone: 419-530-4241, Email: david.bazettjones@utoledo.edu

Michael S. Rathleff, Email: misr@hst.aau.dk

Sinead Holden, Email: siho@hst.aau.dk.

References

- 1.King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain. 2011;152(12):2729–2738. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamper SJ, Henschke N, Hestbaek L, Dunn KM, Williams CM. Musculoskeletal pain in children and adolescents. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(3):275–284. doi: 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Metwally A, Salminen JJ, Auvinen A, Kautiainen H, Mikkelsson M. Prognosis of non-specific musculoskeletal pain in preadolescents: a prospective 4-year follow-up study till adolescence. Pain. 2004;110(3):550–559. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray CJ, Richards MA, Newton JN, Fenton KA, Anderson HR, Atkinson C, et al. UK health performance: findings of the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2013;381(9871):997–1020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rathleff MS, Rathleff CR, Olesen JL, Rasmussen S, Roos EM. Is knee pain during adolescence a self-limiting condition? Prognosis of patellofemoral pain and other types of knee pain. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(5):1165–1171. doi: 10.1177/0363546515622456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brattberg G. Do pain problems in young school children persist into early adulthood? A 13-year follow-up. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(3):187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuss S, Page G, Katz J. Persistent pain in a community-based sample of children and adolescents. Pain Res Manag. 2011;16(5):303–309. doi: 10.1155/2011/534652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dissing KB, Hestbaek L, Hartvigsen J, Williams C, Kamper S, Boyle E, et al. Spinal pain in Danish school children - how often and how long? The CHAMPS study-DK. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1424-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones GT, Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ. Predicting the onset of widespread body pain among children. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(9):2615–2621. doi: 10.1002/art.11221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathleff MS HS, Straszek C ,Olesen JL, Jensen MB, Roos EM. Five-year prognosis and impact of adolescent knee pain: a prospective population-based cohort study of 504 adolescents. In Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Rathleff MS, Roos EM, Olesen JL, Rasmussen S. High prevalence of daily and multi-site pain--a cross-sectional population-based study among 3000 Danish adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:191. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamaleri Y, Natvig B, Ihlebaek CM, Bruusgaard D. Localized or widespread musculoskeletal pain: does it matter? Pain. 2008;138(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckhoff C, Straume B, Kvernmo S. Multisite musculoskeletal pain in adolescence and later mental health disorders: a population-based registry study of Norwegian youth: the NAAHS cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012035. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rathleff Michael S., Roos Ewa M., Olesen Jens L., Rasmussen Sten, Arendt-Nielsen Lars. Lower Mechanical Pressure Pain Thresholds in Female Adolescents With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2013;43(6):414–421. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2013.4383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coenen P, Smith A, Paananen M, Peter O'Sullivan P, Beales D, Leon Straker P. Trajectories of low-back pain from adolescence to young adulthood. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Michaleff ZA, Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Evans R, Broderick C, Henschke N. Low back pain in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness of conservative interventions. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(10):2046–2058. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3461-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arendt-Nielsen L, Graven-Nielsen T. Translational musculoskeletal pain research. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(2):209–226. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bot SD, van der Waal JM, Terwee CB, van der Windt DA, Bouter LM, Dekker J. Course and prognosis of elbow complaints: a cohort study in general practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(9):1331–1336. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):800–804. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rathleff MS, Roos EM, Olesen JL, Rasmussen S. Early intervention for adolescents with patellofemoral pain syndrome--a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auvinen JP, Tammelin TH, Taimela SP, Zitting PJ, Jarvelin MR, Taanila AM, et al. Is insufficient quantity and quality of sleep a risk factor for neck, shoulder and low back pain? A longitudinal study among adolescents. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(4):641–649. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1215-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milewski MD, Skaggs DL, Bishop GA, Pace JL, Ibrahim DA, Wren TA, et al. Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34(2):129–133. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson JA, Coons SJ, Ergo A, Szava-Kovats G. Valuation of EuroQOL (EQ-5D) health states in an adult US sample. PharmacoEconomics. 1998;13(4):421–433. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199813040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopkins WG, Marshall SW, Batterham AM, Hanin J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(1):3–13. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013;14(12):1539–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Picavet HS, Berentzen N, Scheuer N, Ostelo RW, Brunekreef B, Smit HA, et al. Musculoskeletal complaints while growing up from age 11 to age 14: the PIAMA birth cohort study. Pain. 2016;157(12):2826–2833. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holden S, Rathleff MS, Roos EM, Jensen MB, Pourbordbari N, Graven-Nielsen T. Pain patterns during adolescence can be grouped into four pain classes with distinct profiles: a study on a population based cohort of 2953 adolescents. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(4):793–799. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green DJ, Lewis M, Mansell G, Artus M, Dziedzic KS, Hay EM, et al. Clinical course and prognostic factors across different musculoskeletal pain sites: a secondary analysis of individual patient data from randomised clinical trials. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(6):1057–1070. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Artus M, Campbell P, Mallen CD, Dunn KM, van der Windt DAW. Generic prognostic factors for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e012901. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallen CD, Peat G, Thomas E, Dunn KM, Croft PR. Prognostic factors for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(541):655–661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jayanthi NA, LaBella CR, Fischer D, Pasulka J, Dugas LR. Sports-specialized intensive training and the risk of injury in young athletes: a clinical case-control study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):794–801. doi: 10.1177/0363546514567298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DiFiori JP, Benjamin HJ, Brenner J, Gregory A, Jayanthi N, Landry GL, et al. Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: a position statement from the American medical Society for Sports Medicine. Clin J Sport Med. 2014;24(1):3–20. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vierola A, Suominen AL, Lindi V, Viitasalo A, Ikavalko T, Lintu N, et al. Associations of sedentary behavior, physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and body fat content with pain conditions in children: the physical activity and nutrition in children study. J Pain. 2016;17(7):845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bundy DAP, de Silva N, Horton S, Patton GC, Schultz L, Jamison DT. Investment in child and adolescent health and development: key messages from disease control priorities, 3rd Edition. Lancet. 2018;391(10121):687–699. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32417-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dahl RE, Allen NB, Wilbrecht L, Suleiman AB. Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature. 2018;554(7693):441–450. doi: 10.1038/nature25770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foundation NS. 2006 Sleep in America Poll 2006 [Available from: http://sleepfoundation.org/sites/default/files/2006_summary_of_findings.pdf.

- 37.Lewandowski AS, Palermo TM, De la Motte S, Fu R. Temporal daily associations between pain and sleep in adolescents with chronic pain versus healthy adolescents. Pain. 2010;151(1):220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slavish D, Graham-Engeland J, Martire L, Smyth J. (394) bidirectional associations between daily pain, affect, and sleep quality in young adults with and without chronic back pain. J Pain. 2017;18(4):S73. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonvanie IJ, Oldehinkel AJ, Rosmalen JG, Janssens KA. Sleep problems and pain: a longitudinal cohort study in emerging adults. Pain. 2016;157(4):957–963. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boakye PA, Olechowski C, Rashiq S, Verrier MJ, Kerr B, Witmans M, et al. A critical review of neurobiological factors involved in the interactions between chronic pain, depression, and sleep disruption. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(4):327–336. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rathleff MS, Skuldbøl SK, Rasch MNB, Roos EM, Rasmussen S, Olesen JL. Care-seeking behaviour of adolescents with knee pain: a population-based study among 504 adolescents. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:225. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.