Abstract

Objectives:

Miami has the highest rate of new HIV diagnoses in the United States. We examined the early successes and challenges in fulfilling recommendations made by the Miami-Dade County HIV/AIDS Getting to Zero Task Force, formed by local experts in 2016.

Methods:

We used a host of surveillance data, published empirical studies, public reports, and unpublished data from partners of the Task Force to evaluate progress and challenges in meeting the recommendations.

Results:

Improvements in prevention and care included routinized HIV testing in emergency departments, moving the linkage-to-care benchmark from 90 to 30 days, increased viral suppression, and awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis. However, treatment enrollment, viral suppression, and pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake remained low.

Conclusions:

Recommendations from the Task Force provide excellent guidance for implementing evidence-based HIV prevention in Miami, yet success in achieving the recommendations will require continued or increased support in many public health sectors in South Florida.

Keywords: HIV, HIV prevention, implementation science

What Do We Already Know About This Topic?

A Getting to Zero plan has been established, but we do not know the broad progress and challenges in fulfilling the recommendations put forth in the plan.

How Does Your Research Contribute to the Field?

We provide an overview of important accomplishments and challenges facing HIV prevention efforts in Miami, which continues to have the highest HIV incidence in the United States.

How Does Your Research Contribute to the Field?

Our research shows that significant work has yet to be done to apply the recommendations made in the Getting to Zero effort, although there has been significant progress in a handful of areas, including HIV testing, treatment, and awareness to pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Introduction

In 2017, Miami-Dade County in Florida had the highest annual rate of newly diagnosed HIV infections (42.9 cases per 100 000 residents) of all cities and counties monitored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States.1 This rate was more than twice as high as New York City (17.9), San Francisco (18.5), Los Angeles (15.0), and Washington, DC (18.0).1 The Miami rate was highest for all but 2 such surveillance reports in the United States since 2004.2 Since 2004, HIV incidence has decreased in Miami in all major transmission categories: injection drug use, heterosexual, and sex among men who have sex with men (MSM).3 These reductions have, however, lagged behind substantial progress in other metropolitan areas.2 Additionally, although the HIV epidemic in Miami is driven primarily by MSM transmission, other groups, particularly heterosexual non-Hispanic black men and women and persons who inject drugs, are at increased risk.3,4

The complex nature of the HIV epidemic in Miami (many racial, ethnic, and sexually diverse risk groups and geographic diversity of HIV risk) is an example of local challenges surrounding HIV prevention: no single pharmacological, behavioral, or structural intervention is sufficient to eliminate HIV transmission.5-8 For example, although condoms have been effective in preventing sexual HIV transmission,9 they have not been used to the extent necessary to eliminate HIV infections in Miami or elsewhere in the United States.10,11 More recently, promoted pharmacological interventions, such as secondary prevention through antiretroviral therapy and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), have also had real-world limitations in Miami and elsewhere, despite promising results in trial settings.12-16 These antiretroviral-based prevention strategies have encountered hurdles in their implementation with respect to early HIV diagnosis,17,18 drug adherence,18,19 and access to antiretroviral treatment or prophylaxis.14,18

To address the limitations of any single HIV prevention strategy, various jurisdictions have developed a combination of approaches to prevention, such as structural and individual-level prevention strategies that tailor program priorities to local epidemics for maximum effect.5,8 In 2016, experts from local government, the health sector, and academia formed the Miami-Dade County HIV/AIDS Getting to Zero Task Force (hereinafter, Task Force), which followed participation in the Paris Declaration as a Fast-Track City beginning in 2015. This Task Force brought together 29 leaders in business, social services, government, and health care to make recommendations for HIV prevention to the Mayor of Miami-Dade County and the Miami-Dade County Board of Commissioners. The Task Force was created in conjunction with the Office of the Mayor of Miami-Dade County and as an ad hoc subcommittee of the local Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative Planning Board of the Miami-Dade HIV/AIDS Partnership.

The Florida Department of Health (FDOH) in Miami-Dade County and the Office of the Mayor set 3 overarching goals that would be elaborated by subsequent Task Force recommendations:

Know the facts: 90% of all Miami-Dade County residents living with HIV will know their status by 2020.

Get tested: reduce the number of new HIV diagnoses by at least 25% by 2020.

Get treated: 90% of Miami-Dade County residents living with HIV who are in treatment will attain viral load suppression by 2020.

On February 13, 2017, the Task Force submitted 16 recommendations that were subsequently approved by the Office of the Mayor of Miami-Dade County, the Miami-Dade HIV/AIDS Partnership, and the FDOH in Miami-Dade County (Table 1).

Table 1.

Miami-Dade County “Getting to Zero” Taskforce Recommendations.

| Recommendation | Responsible Entities/Champions |

|---|---|

| Provide comprehensive sex education throughout the M-DCPS, recommending modifications in the M-DCPS comprehensive sex education curriculum as age-appropriate | Miami-Dade County Public Schools Government of Miami-Dade County |

| Expand PrEP and nPEP capacity throughout Miami-Dade County and increase utilization by all potential risk groups | FDOH in Miami-Dade County |

| Implement routine HIV/STI testing in health-care settings | FDOH in Miami-Dade County |

| Create a comprehensive HIV/AIDS communication toolbox | FDOH, Office of AIDS Central Office |

| Convene a multiagency consortium of public health/academic institutions/service providers to share data/collaborate on research identifying the driving forces of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Miami-Dade County | FDOH in Miami-Dade County Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative Program |

| Decrease the lag time from diagnosis to linkage to HIV/AIDS care to within 30 days or less for (1) clients newly diagnosed, (2) clients returning to care, (3) clients postpartum | FDOH in Miami-Dade County |

| Increasing system capacity to bridge the gaps in provision of treatment and medication when changes in income and/or residence create eligibility problems | Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative Program |

| Enlist commercial pharmacies as HIV/AIDS treatment partners, from making PrEP and nPEP more available to having pharmacist’s alert HIV/AIDS care clinicians and/or case managers when ARV medications are not picked up on time | FDOH, Office of AIDS Central Office Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative Program |

| Partnership with MCOs and Medicaid for the purpose of data-matching and to allow FDOH to follow HIV-positive clients in managed care positions (public and private) | FDOH, Office of AIDS Central Office Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative Program |

| Develop a county-wide integrated system of HIV/AIDS care, including a county-wide treatment consent form and county-wide data-sharing addressing various social service needs | Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Central Office FDOH Central Office |

| Expand the network of housing available for PLWHA, with particular attention to pregnant women, released ex-offenders, youth and other high-risk HIV-positive groups | Government of Miami-Dade County Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative Program |

| Create/expand a network of internal (in-jail) and post release HIV/AIDS service provision to inmates in the Miami-Dade County jail system | FDOH, Office of AIDS Miami Office Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative Program |

| Identify root causes of HIV/AIDS stigma; reduce stigma through educational and communication programs directed toward Miami-Dade County’s multicultural and multiethnic communities | Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative Program |

| Reform and modernize Florida’s current statutes criminalizing HIV nondisclosure | Government of Miami-Dade County Senator Rene Garcia’s Office |

| Build a county-wide system of HIV/AIDS program effectiveness evaluation, basing it on a common set of outcome measures across all providers | FDOH in Miami-Dade County Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative Program |

| Identify barriers and improve access to existing HIV/AIDS services for HIV positive undocumented immigrants | Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative Program |

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; ARV, antiretroviral; FDOH, Florida Department of Health; MCOs, managed care organizations; M-DCPS, Miami-Dade County Public School System; nPEP, nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis; PLWHA, people living with HIV/AIDS; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Evaluation of Progress and Challenges

The recommendations made by the Task Force were developed and approved by a consortium of policy-makers and HIV prevention stakeholders, yet they are not supported by any specific local legislation or budgetary allocation. The implementation of these recommendations should be—and are being—carefully monitored.20-22 We examine the early successes and challenges in fulfilling the Task Force recommendations and describe recent epidemiologic trends in Miami. The objective of this evaluation is to broadly characterize improvements in HIV prevention efforts recommended by the Task Force and summarize relevant outcomes. We focus on key areas: HIV incidence and risks for infection, the HIV continuum of care, PrEP, harm reduction, research data sharing, and legislative progress. We provide generalized summaries of efforts that have achieved notable progress or encountered substantial barriers.

Methods

We used the recommendations made by the Task Force as a guide to HIV prevention priorities for the Miami HIV epidemic, yet the progress and challenges in achieving these recommendations did not manifest only after the Task Force’s final report, so our evaluation extends to before their release, where possible. Specifically, we used surveillance data from FDOH from 1998 to 2017 to summarize epidemiologic trends in the prevalence and incidence of HIV infection in Miami-Dade County. We used published empirical studies, public reports, and unpublished data from partners of the Task Force to evaluate progress and challenges in meeting the proposed recommendations. These sources included public reports on the HIV care continuum, empirical studies of PrEP awareness and use, unpublished data from HIV testing and harm reduction services, and publicly available data on state and local legislation.

For all estimates of the HIV care continuum obtained from the FDOH in Miami-Dade County, HIV diagnosis refers to persons known to be diagnosed with HIV and living in Miami-Dade County at the end of 2017, from data as of June 30, 2018. Linkage to care status refers to persons diagnosed with HIV with ≥1 documented viral load or CD4 laboratory results, medical visit, or prescription from HIV diagnosis through March 31, 2018. Retained in care status refers to persons diagnosed with HIV with ≥2 documented viral load or CD4 laboratory results, medical visits, or prescriptions ≥3 months apart from January 1, 2017, through June 30, 2018. Viral suppression refers to persons diagnosed with HIV with a suppressed viral load (<200 copies/mL) on the last assay from January 1, 2017, through March 31, 2018.

Ethical and Informed Consent

Ethics approval and informed consent were not required for this study since all data obtained were publicly available or anonymized by the source; no direct contact with human participants was conducted.

Results

A total of 27 969 prevalent cases of HIV were reported among residents of Miami-Dade County in 2017, and they accounted for 23.9% (27 969/116 944) of all estimated HIV cases in Florida.3 Of the 27 969 diagnosed cases of HIV, 74.3% (n = 24 610) were among men. Most identified prevalent cases of HIV (88%, n = 24 610) were among Hispanic and non-Hispanic black residents.3

HIV Incidence and Risks for Infection

Although year-on-year reductions in new HIV diagnoses have been modest in Miami-Dade County since about 2009,3 HIV prevention efforts may have gained momentum since the end of 2015: the rate of new HIV diagnoses decreased by 14% from 2015 to 2017 (from 50.3 per 100 000 residents to 43.4, respectively).3 Florida Department of Health reported 1195 newly diagnosed cases of HIV in Miami-Dade County in 2017 (43.4 per 100 000 residents), which was almost double the rate of cases of newly diagnosed HIV in Florida (24.1 per 100 000 residents)3; about 80% of all new infections were reported among men (71.2 per 100 000 residents), of whom 84% reported a history of sex with men.3

The ratio of newly diagnosed HIV infections among men and women in Miami increased from 1.7:1.0 in 1998 to 2.7:1.0 in 2008, and 3.9:1.0 in 2017.3 Although women only accounted for about 20% of all new HIV infections in 2017, substantial risk existed among non-Hispanic black women (68.5 per 100 000 residents).3 Hispanic residents accounted for 59% of all new HIV diagnoses in 2017, yet their risk of new infections (37.8 per 100 000 residents) was lower than the risk for the non-Hispanic population (55.1 per 100 000 residents). Despite an overall decrease in the number of new HIV diagnoses, to 1270 in 2016 and to 1195 in 2017, the number of new diagnoses did not decrease among all risk groups: new diagnoses among non-Hispanic black women increased from a rate of 58.5 per 100 000 residents in 2014 to 68.5 per 100 000 residents in 2017.

HIV Care Continuum

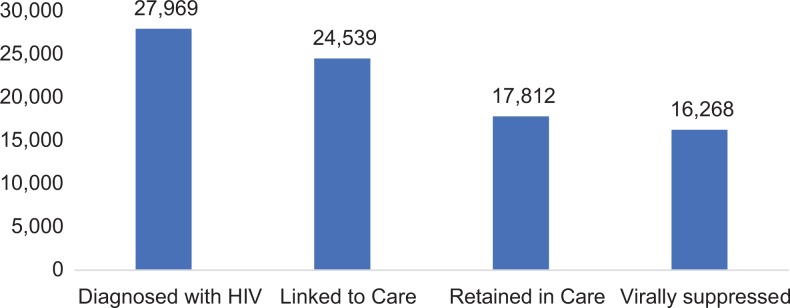

Although 87.1% of persons with HIV who were retained in care had achieved viral suppression by the end of 2017, these 15 521 virally suppressed persons represented only 55.5% of known HIV infections among Miami-Dade County residents (Figure 1). Sixty-two percent of all diagnosed cases were retained in care in 2017; however, about two-thirds of persons with diagnosed HIV (18 236/27 969) had ≥1 documented HIV care event.23 Of the 1195 persons newly diagnosed with HIV in 2017 in Miami-Dade County, 89.0% (1064/1195) had documented receipt of HIV care within 3 months of diagnosis.23

Figure 1.

HIV Care Continuum for Miami-Dade County, Florida, 2017. Diagnosed with HIV: The number of persons known to be diagnosed and living in Miami-Dade County with HIV at the end of 2017, from data as of June 30, 2018; Linked to Care: Those diagnosed with HIV with at least one documented viral load or CD4 lab, medical visit, or prescription from HIV diagnosis through March 31, 2018; Retained in Care: Those Diagnosed with HIV with 2 or more documented VL or CD4 labs, medical visits, or prescriptions at least 3 months apart from January 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018; Suppressed Viral Load: Those diagnosed with HIV with a suppressed viral load (<200 copies/mL) on the last assay from January 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018. This figure was assembled using data from the Florida Department of Health in Miami-Dade County.

Several major facilities in Miami-Dade County have implemented universal routine (opt-out) HIV testing for all patients aged ≥18 in settings that include academic medical centers, community hospitals, emergency departments, and primary care settings, as well as community programs that include Florida’s first and only needle-exchange demonstration project. Some of these facilities have implemented the Frontlines of Communities in the United States (FOCUS) program, developed by Gilead Sciences, to establish routine blood-borne virus (HIV, hepatitis C virus [HCV], and hepatitis B virus) screening, diagnosis, and linkage to care in US hospitals, clinics, and community centers. After a reactive screening test and confirmatory diagnosis, FOCUS programs provide support for staff members at each facility to contact FDOH to determine if the patient has received a previous HIV diagnosis or if this represents a new diagnosis. Florida Department of Health dispatches a disease intervention specialist to link the patient to HIV care within the next 30 days.

Jackson Memorial Hospital, which is located near several communities of elevated HIV risk within the Miami-Dade community, administers the greatest number of HIV diagnostic assays. According to Gilead Sciences (oral communication, June 2018), before implementation of the FOCUS protocol in 2017, Jackson Memorial Hospital administered approximately 800 targeted HIV tests per year in the emergency department. In the year after implementation of the new protocol, Jackson Memorial Hospital had screened >20 000 emergency department patients. Similarly, Homestead Hospital administered <100 HIV tests per year in its emergency department before 2016. In the year after implementation of the FOCUS protocol, it administered approximately 14 000 HIV screening tests. Three additional facilities have implemented routinized HIV testing with support from the FOCUS program: Jackson South Community Hospital, a sister hospital to Jackson Memorial Hospital in southern Miami-Dade; Borinquen Medical Center, a federally qualified health center; and the University of Miami Infectious Disease Elimination Act (IDEA) Exchange, the sole clean needle exchange program in Florida. The facilities were chosen because of their proximity to the local epidemic and because they provide HIV prevention and treatment services in Miami-Dade County. During May 1, 2017, through April 30, 2018, the FOCUS program supported 54 053 HIV screening tests among all partners in Miami-Dade County, with an overall HIV positivity of 1.9% (written communication, Gilead Sciences, March, 2019).

HIV testing has increased considerably in the past 20 years in Miami, yet it is difficult to obtain estimates for the proportion of the HIV-infected population in Miami that is unaware of its HIV status. Sparse data are available for some high-risk groups: in the 2014 MSM cycle of the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) system, the most recent year for which data are available, 32.6% of HIV-positive MSM in Miami reported that they were previously unaware of their HIV-positive status.24 In the 2013 cycle of the NHBS, 35% of HIV-positive heterosexual men and women at increased risk of infection in Miami were unaware of their status.25 Data are needed to determine whether the size of the undiagnosed population in these high-risk groups has decreased.

Starting in 2018, FDOH revised its objective for linkage to care from 90 days to 30 days after diagnosis. In the first quarter of 2018 (ie, January-March 2018), 76% of all newly diagnosed persons in Miami-Dade County were successfully linked to care within 30 days (written communication, FDOH Surveillance Unit for Linkage-to-Care, 2018). At FDOH testing sites, 92% were linked to care within 30 days. Among persons receiving HIV care in 2017, an estimated 85% had achieved viral suppression, an increase from 2013 when only 71% of those receiving any HIV care were estimated to be virally suppressed.23,26 As of March, 2019, a pharmacy work group established by the Miami-Dade Ryan White Partnership was expected to release findings of an investigation into the barriers to accessing HIV medications in Miami by the summer of 2019.

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

In 2017, FDOH committed to providing up to a 90-day free supply of medication for PrEP among all eligible patients visiting county health department sexually transmitted disease and family planning clinics.27 This commitment marks a positive step in scaling up PrEP delivery, yet many high-risk persons in this setting lack knowledge of or access to PrEP. A study conducted in 2014 among MSM recruited for the NHBS system found that only 41% of MSM in Miami had ever heard of PrEP as a means to prevent HIV infection, and <2% reported taking PrEP in the previous 12 months, despite reports of frequent risk-taking behaviors in the sample.28 Awareness of PrEP among MSM in Miami doubled from the 2011 (20% aware) to the 2014 (41%) NHBS surveys (P < .001).28,29 Research among sheltered women in Miami conducted in 2014 suggested a low awareness of PrEP, with 21% (15/74) reporting knowledge before being enrolled in the study.30

In 2017, Doblecki-Lewis et al published data on the continued use of PrEP among MSM who participated in the PrEP Demonstration Project.15 Of 99 MSM in Miami who participated in the PrEP Demonstration Project, 90% (89/99) reported interest in receiving PrEP after study completion.15 Yet, access to PrEP among project participants remained limited, with only 18% (18/99) reporting receiving a prescription since they left the original study.15

Researchers published evidence in 2018 of informal, or nonprescriptive, use of antiretroviral medication to prevent HIV acquisition among MSM in Miami and elsewhere in South Florida.31 Data from this research were first reported in 2017 when it was also found that of 24 MSMs who had a history of substance use, 2 had recently seroconverted while engaging in unsupervised and sporadic PrEP usage.32 Lack of access to medically supervised PrEP can lead to inappropriate usage of antiretroviral medication for primary prevention. Illicit sales and sharing of the medication should be monitored because these practices interfere with the effectiveness of interventions designed to interrupt HIV transmissions in the community.33

Lack of access may be due in part to the underuse of PrEP by medical providers. A study conducted during 2012 to 2013 among HIV care and infectious disease physicians in Washington, DC, and Miami found that only 17% had ever prescribed PrEP to ≥1 of their patients.16 Although provider characteristics have been identified as a perceived barrier to PrEP, a 2017 study among MSM in San Francisco and Miami found drug expense and lack of insurance to be the most common obstacles to adoption by prospective enrollees.15

Referring and linking persons at high risk of HIV infection to knowledgeable practitioners is a central component of delivering PrEP in Miami-Dade County. The quality of medical referral (eg, active versus passive) may have a substantial effect on responses and follow-up for HIV-related services.33 In early 2018, FDOH in Miami-Dade County released a draft protocol for an active referral system for PrEP (PrEPLink) that had 3 primary objectives: (1) increase community outreach activities to HIV-negative persons at high risk of infection, (2) establish a referral network for PrEP providers, and (3) track the linkage of care for persons who receive a PrEP referral.34 PrEPLink is currently advertised and described in materials being distributed by FDOH (Figure 2). It has proposed a 48 business-hour timetable for receipt of referrals for all major PrEP providers in Miami. The development of a comprehensive referral system represents a positive step toward enhanced centralization and tracking of PrEP services in Miami-Dade. A Miami PrEP workgroup, organized by FDOH in Miami-Dade County, has been convened to explore pathways to increased access to PrEP for high-risk populations and remove locally relevant barriers experienced by patients and at-risk persons in Miami.

Figure 2.

Sample “PrEPLink” referral advertisement designed by the Florida Department of Health in Miami-Dade County, Florida. This figure was adapted from a sample PrEPLink flyer developed by the Florida Department of Health in Miami-Dade County. PrEP indicates pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Harm Reduction

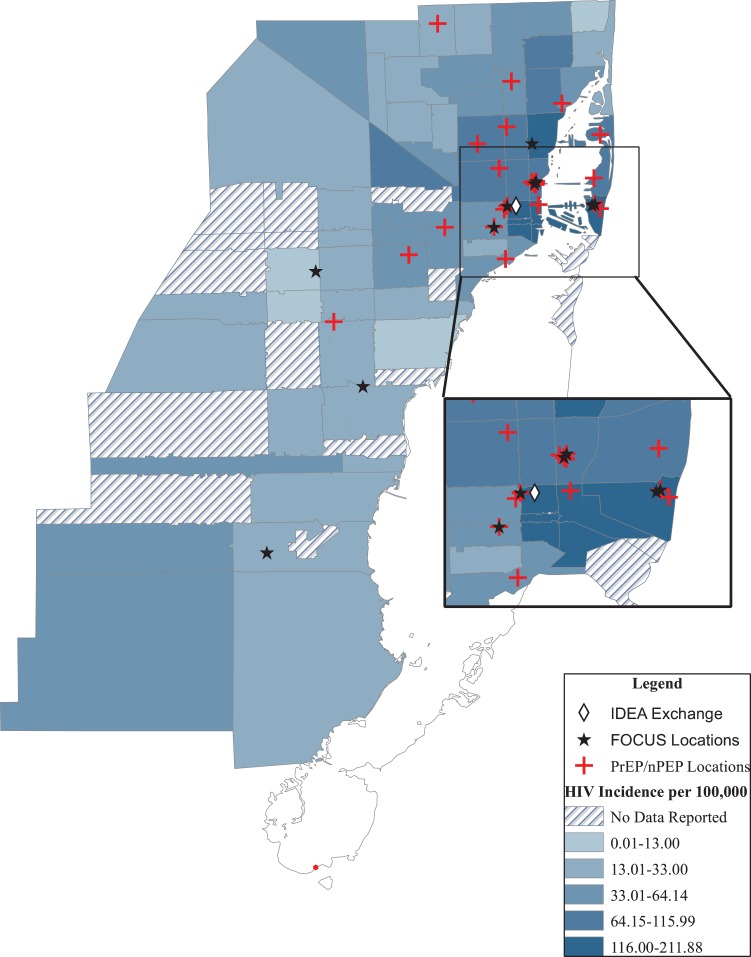

HIV transmission through injection drug use has decreased dramatically in Miami in recent decades3; however, a substantial risk remains among people who inject drugs (PWID). In 2016, the University of Miami’s IDEA Exchange began providing syringe exchange services to PWID in Miami.35 Infectious Disease Elimination Act Exchange provides evidence-based HIV prevention through harm reduction among a population with a highly elevated risk of HIV acquisition.36 Administered through the University of Miami and centrally located (Figure 3), IDEA Exchange also provides other services, such as HIV and HCV testing, naloxone, and linkage to addiction treatment providers. As of August 2018, IDEA Exchange reported having provided services to 845 PWID (with 6899 total visits), exchanged 184 322 clean needles, and delivered 1416 doses of naloxone, which resulted in 724 overdose reversals (written communication, August 2018). Recently, local officials addressed publicly an investigation into a potentially large number of new cases of HIV and HCV among homeless PWID in the Overtown area of Miami. Despite widespread media attention, this investigation has yet to uncover an identified outbreak or changing risk dynamics in this community.

Figure 3.

Map of selected HIV prevention services in Miami-Dade County, Florida, including PrEP/nPEP, routinized HIV testing, and harm reduction overlayed on HIV Incidence Estimates for 2016. The FOCUS program established routine blood-borne virus screening, diagnosis, and linkage to care in US hospitals, clinics, and community centers, including in Miami-Dade County. The IDEA Exchange provides HIV prevention services to people who inject drugs (PWID), including syringe exchange. FOCUS indicates Frontlines of Communities in the United States; IDEA Exchange, Infectious Disease Elimination Act Exchange; nPEP, non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Research Data Sharing

An important Task Force recommendation focuses on data sharing among care providers and researchers interested in secondary analyses. Florida Department of Health in Miami-Dade County has partnered with Florida International University to identify research opportunities and future collaboration; these institutions plan to develop a 5-year strategic plan outlining these goals.20 Similarly, a data-sharing agreement has been established between the Ryan White Part A/Minority AIDS Initiative program in Miami-Dade County and public health researchers at Florida International University. According to researchers at the Behavioral Science Research Corporation (written communication, June 2018), the data-sharing agreement permits researchers at Florida International University to access deidentified client-level data from almost 50 000 records, which include data on hundreds of clinical end points and demographic characteristics, including results of viral load testing, antiretroviral therapy regimens, behavioral risk factors, and client retention in care.

Legislative Progress

Several Florida state senators championed a bipartisan, bicameral anticriminalization of disclosure bill, the HIV Prevention Justice Act, in the 2017-2018 legislative session of the Florida State Congress. Identical bills, SB546 and H719, were filed in fall 2017 for spring 2018 legislative consideration. The Act sought to modernize Florida’s laws on the transfer of disease through bodily fluids by decreasing the severity of punishment for transfer of disease from a felony to a first-degree misdemeanor and to clarify the definition of “intent” in the transfer of disease through bodily fluids. In March 2018, both bills were indefinitely postponed and, ultimately, withdrawn from consideration.

The Task Force recommendations call for comprehensive, age-appropriate sexual education in Miami-Dade schools. These recommendations are supported by strong indications of sexual risk behavior in Miami-Dade adolescents: 56.8% of Miami-Dade high school students in 2017 reported sexual experience (slightly higher than the national average of 52.2%), and only 18.6% had ever been tested for HIV.37 Furthermore, Miami-Dade County has the most cases of bacterial sexually transmitted infections among 13- to 19-year-olds in Florida.38 In 2018, with guidance from FDOH in Miami-Dade County, Miami-Dade’s Board of County Commissioners unanimously passed a resolution (R-250-18) that urged Miami-Dade County Public Schools to modify the current comprehensive abstinence-only sexual education curriculum, as age-appropriate, to include education about HIV and sexually transmitted diseases to high school students. Although this represents a local political success in providing comprehensive sexual education in Miami-Dade County, less success has been achieved at the state level. After the failure of the Florida Healthy Adolescence Act (HB 859) to leave the Florida House of Representatives K-12 Subcommittee in 2016, no comprehensive statewide sexual education bills seeking to increase awareness of HIV prevention in the public school system have been introduced.39 Legislative failures demonstrate the difficulty in aligning local public health priorities with the statewide political environment in the implementation of the Task Force’s recommendations, particularly reliable sexual education for at-risk young persons.

Conclusion

Recommendations of the Task Force have established a multifaceted plan for eliminating new HIV infections in the Miami-Dade County. These recommendations provide guidance for implementing evidence-based HIV prevention and treatment strategies in a highly diverse setting. Although progress has been noted in some areas, such as routine HIV testing, linkage to care, and eliminating barriers to access to PrEP, much work remains, particularly in achieving population-level antiretroviral therapy enrollment, HIV suppression, and PrEP uptake. Furthermore, because the recommendations proposed by the Task Force were not accompanied by any budgetary commitments, it is difficult to estimate the effect of the proposed prevention plan.

Despite recent reductions in new HIV diagnoses, continued efforts must be made to ensure that all risk groups, including non-Hispanic black women, who have had an increase in new diagnoses, benefit from enhanced HIV prevention efforts. Further research is needed to determine the number of undiagnosed infections in various segments of the at-risk population; the most recent data available suggest that a substantial portion of HIV-infected persons may still be unaware of their HIV status. Success in achieving all of the evidence-based recommendations made by the Task Force will require continued or increased support throughout many sectors of the public health apparatus in South Florida.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the Getting 2 Zero Task Force, on which this work is based. They would also like to thank the Florida Department of Health in Miami-Dade County for providing critical support and review of the manuscript, and the Frontlines of Communities in the United States (FOCUS) program, and the Infectious Disease Elimination Act (IDEA) Exchange for providing details on their HIV testing protocol and HIV prevention services, respectively.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K01-AI138863, T32-AI007433) and a Developmental Award (P30-AI060354) from the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR).

ORCID iD: Daniel J. Escudero, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1621-2820

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1621-2820

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report. 2017;29 https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2017-vol-29.pdf. Published November 2018. Accessed March 19, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance reports archive. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance-archive.html. Published November 15, 2018. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- 3. Florida Department of Health. HIV cases per 100,000 population. 2017. http://www.flhealthcharts.com/charts/OtherIndicators/NonVitalHIVAIDSViewer.aspx?cid=0471. Accessed August 3, 2018.

- 4. AIDSVu. Local data: Miami (Miami-Dade County). https://aidsvu.org/state/florida/miami. Accessed May 14, 2019.

- 5. Caceres CF, Koechlin F, Goicochea P, et al. The promises and challenges of pre-exposure prophylaxis as part of the emerging paradigm of combination HIV prevention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(4 suppl 3):19949 doi:10.7448/IAS.18.4.19949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cremin I, Alsallaq R, Dybul M, Piot P, Garnett G, Hallett TB. The new role of antiretrovirals in combination HIV prevention: a mathematical modelling analysis. AIDS. 2013;27(3):447–458. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835ca2dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Padian NS, McCoy SI, Karim SS, et al. HIV prevention transformed: the new prevention research agenda. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):269–278. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60877-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hankins CA, de Zalduondo BO. Combination prevention: a deeper understanding of effective HIV prevention. AIDS. 2010;24(suppl 4):S70–S80. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000390709.04255.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weller S, Davis K. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD003255 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marshall BD, Paczkowski MM, Seemann L, et al. A complex systems approach to evaluate HIV prevention in metropolitan areas: preliminary implications for combination intervention strategies. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44833 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stevens PE, Galvao L. “He won’t use condoms”: HIV-infected women’s struggles in primary relationships with serodiscordant partners. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1015–1022. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.075705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spinner CD, Boesecke C, Zink A, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): a review of current knowledge of oral systemic HIV PrEP in humans. Infection. 2016;44(2):151–158. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0850-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilson DP. HIV treatment as prevention: natural experiments highlight limits of antiretroviral treatment as HIV prevention. PLoS Med. 2012;9(7):e1001231 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirby T, Thornber-Dunwell M. Uptake of PrEP for HIV slow among MSM. Lancet. 2014;383(9915):399–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doblecki-Lewis S, Liu A, Feaster D, et al. Healthcare access and PrEP continuation in San Francisco and Miami after the US PrEP Demo Project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(5):531–538. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000001236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castel AD, Feaster DJ, Tang W, et al. Understanding HIV care provider attitudes regarding intentions to prescribe PrEP. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(5):520–528. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dailey AF, Hoots BE, Hall HI, et al. Vital signs: human immunodeficiency virus testing and diagnosis delays—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(47):1300–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Serota DP, Rosenberg ES, Lockard AM, et al. Beyond the biomedical: preexposure prophylaxis failures in a cohort of young black men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(6):965–970. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koenig LJ, Lyles C, Smith DK. Adherence to antiretroviral medications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: lessons learned from trials and treatment studies. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(1 suppl 2):S91–S98. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Florida Department of Health. Miami-Dade County “Getting to Zero” HIV/AIDS Task Force implementation report: 2017-2018. Revised July 2018. https://www.miamidade.gov/budget/library/getting-to-zero-report.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2019.

- 21. Darrow W, Brown T, Blair Z, et al. Getting 2 Zero—Miami: filling the gap between program practice and program science. Poster Presented at: International Union Against Sexually Transmitted Infections 2018; June 27-30, 2018; Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown T, Blair Z, Brown M, et al. Implementation of “Getting 2 Zero” in Miami: a progress report. Poster Presented at: International AIDS Society Conference 2018; June 23-27, 2018; Amsterdam, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Florida Department of Health, Bureau of Communicable Diseases. HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Profile, Florida 2017. Tallahassee; 2018. http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/aids/surveillance/epi-profiles/index.html. Accessed March 27 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among men who have sex with men—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 U.S. cities, 2014. HIV Surveill Rep Special Rep. 2016;15:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV infection, risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among heterosexuals at increased risk of HIV infection—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 U.S. cities, 2013. HIV Surveill Rep Special Rep. 2015;13:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Florida Department of Health, HIV/AIDS Section. HIV/AIDS epidemiology area 11a: Miami-Dade County (excluding Department of Corrections). 2016. http://aidsnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/2015miamidadeepidata.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- 27. On World AIDS Day, Florida Health continues statewide fight against HIV/AIDS [news release]. Tallahassee, FL: Florida Department of Health; 2017. http://www.floridahealth.gov/_documents/newsroom/press-releases/2017/12/120117-world-aids-day.pdf. Accessed July 31, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patrick R, Forrest D, Cardenas G, et al. Awareness, willingness, and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in Washington, DC, and Miami-Dade County, FL: National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 2011 and 2014. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(suppl 3):S375–S382. doi:10.1097.QAI0000000000001414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Forrest DW, Cardenas G, Dodson CS, Metsch LR, Lalota M, Spencer E. Trends in the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in Miami-Dade County, Florida, 2004-2014. Florida Public Health Rev. 2018;15:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Doblecki-Lewis S, Lester L, Schwartz B, Collins C, Johnson R, Kobetz E. HIV risk and awareness and interest in pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis among sheltered women in Miami. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27(10):873–881. doi:10.1177/0956462415601304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buttram ME. The informal use of antiretroviral medications for HIV prevention by men who have sex with men in South Florida: initiation, use practices, medications and motivations. Cult Health Sex. 2018;20(11):1185–1198. doi:1080/13691058.2017.1421709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buttram ME, Kurtz SP. Preliminary evidence of HIV seroconversion among HIV-negative men who have sex with men taking non-prescribed antiretroviral medication for HIV prevention in Miami, Florida, USA. Sex Health. 2017;14(2):193–195. doi:10.1071/SH16108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Garland PM, Valverde EE, Fagan J, et al. HIV counseling, testing and referral experiences of persons diagnosed with HIV who have never entered HIV medical care. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(3 suppl):117–127. doi:10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3_supp.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Florida Department of Health in Miami-Dade County. PrEPLink: Miami-Dade County’s PrEP Referral System Draft—Policy and Procedures Manual. 2018.

- 35. University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. The infectious disease eimination act (IDEA Exchange): reducing the spread of HIV and hepatitis C through harm reduction. http://ideaexchangeflorida.org/about/. Published December 1, 2016. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- 36. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV infection, risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among persons who inject drugs—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance: injection drug use, 20 U.S. cities, 2015. HIV Surveill Rep Special Rep. 2018;18:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Florida Department of Health. FL Health Charts. Bacterial STDs. http://www.flhealthcharts.com/charts/OtherIndicators/NonVitalSTDDataViewer.aspx?cid=9767. Published May 24, 2017. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- 39. The Florida Senate. HB 859: Education in Public Schools Concerning Human Sexality. 2016. http://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2016/859. Accessed June 28, 2018.