Abstract

During development or after brain injury, oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) differentiate into oligodendrocytes to supplement the number of oligodendrocytes. Although mechanisms of OPC differentiation have been extensively examined, the role of epigenetic regulators, such as histone deacetylases (HDACs) and DNA methyltransferase enzymes (DNMTs), in this process is still mostly unknown. Here, we report the differential roles of epigenetic regulators in OPC differentiation. We prepared primary OPC cultures from neonatal rat cortex. Our cultured OPCs expressed substantial amounts of mRNA for HDAC1, HDAC2, DNMT1, and DNMT3a. mRNA levels of HDAC1 and HDAC2 were both decreased by the time OPCs differentiated into myelin-basic-protein expressing oligodendrocytes. However, DNMT1 or DNMT3a mRNA level gradually decreased or increased during the differentiation step, respectively. We then knocked down those regulators in cultured OPCs with siRNA technique before starting OPC differentiation. While HDAC1 knockdown suppressed OPC differentiation, HDAC2 knockdown promoted OPC differentiation. DNMT1 knockdown also suppressed OPC differentiation, but unlike HDAC1/2, DNMT1-deficinent cells showed cell damage during the later phase of OPC differentiation. On the other hand, when OPCs were transfected with siRNA for DNMT3a, the number of OPCs was decreased, indicating that DNMT3a may participate in OPC survival/proliferation. Taken together, these data demonstrate that each epigenetic regulator has different phase-specific roles in OPC survival and differentiation.

Keywords: oligodendrocyte precursor cell, cell differentiation, epigenetic regulator, HDAC, DNMT

Introduction:

The oligodendrocyte precursor cell (OPC) serves as a progenitor cell of terminally differentiated oligodendrocytes. Matured oligodendrocytes form myelin sheaths around axons in the central nervous system, and the myelin sheath is essential in the fast impulse propagation along the myelinated fiber. Because oligodendrocytes do not proliferate, OPCs play a critical role in increasing the number of oligodendrocytes during development or after oligodendrocyte/myelin damage. Mechanisms of OPC differentiation have been extensively examined, and several extrinsic signaling molecules have been identified as regulators of OPC differentiation into oligodendrocytes (Domingues et al. 2017; Takebayashi and Ikenaka 2015; Zhang et al. 2016). However, while the epigenetic system is known to participate in cell fate decisions, mechanisms as to how the epigenetic regulators contribute to OPC differentiation are still mostly unknown.

DNA chromatin modifications alter gene expression, a process known as epigenetic regulation. Past studies have demonstrated that epigenetic regulation is closely related to cell differentiation in most organs, including neurogenesis in brain (Yao et al. 2016). Epigenetic regulation can be categorized into histone modification and DNA methylation. Combinations of methylated DNA with acetylated histones are associated with “open” or “closed” epigenetic conditions for gene expression. The degree of histone acetylation is generally determined by a balance between histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), which acetylate and deacetylate lysine residues of histones, respectively. DNA methylation, on the other hand, is mediated by DNA methyltransferase enzymes (DNMTs), which are composed of DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B. In general, DNMT1 is necessary for the maintenance of DNA methylation, and DNMT3A/3B are necessary for de novo DNA methylation. Although the DNA chromatin homeostasis has been implied to participate in the regulation of oligodendrocyte lineage cells (Huang et al. 2015) and past studies demonstrated that epigenetic regulation by HDACs/DNMTs is critical for the process of OPC differentiation (Dugas et al. 2006; Jagielska et al. 2017; Kassis et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2007; Lyssiotis et al. 2007; Moyon et al. 2016; Shen et al. 2005; Shen et al. 2008; Ye et al. 2009), the precise mechanisms of how and when HDACs and DNMTs act on OPC differentiation still remain to be elucidated. In our cell culture system, among the HDAC and DNMT families, HDAC1, HDAC2, DNMT1, and DNMT3a are extensively expressed in OPCs compared to other types of glial cells. Therefore, in this study, we used a primary OPC culture system to examine the roles of these epigenetic regulators (i.e. HDAC1, HDAC2, DNMT1, DNMT3a) in OPC differentiation by suppressing them in different time points during OPC differentiation.

Materials and Methods:

All experiments were performed following institutionally approved protocols by Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care, and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

OPC isolation:

Primary cortical OPCs were prepared for experiments according to our previous work (Itoh et al. 2016; Miyamoto et al. 2015). Briefly, primary mixed glial cells were obtained from the brains of post-natal day 1 SD rats and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; ThermoFisher, #11965) containing 20 % fetal bovine serum. Ten days later, the flasks were shaken for 1 h on an orbital shaker (218 rpm) at 37°C to remove microglia. They were then changed to new medium and shaken overnight (~20 h). The medium was collected and plated on non-coated tissue culture dishes for 1 h at 37°C to remove contaminating astrocytes and microglia. Then, the non-adherent cells (i.e. OPCs) in the culture media were collected and seeded onto poly-DL-ornithine-coated plates. OPC differentiation was initiated on day 4 after cell seeding by changing culture media from the OPC proliferating media (Neurobasal Medium containing 2% B27 supplement, 2 mM glutamine, 10 ng/mL PDGF-AA, and 10 ng/mL FGF-2) to the OPC differentiation media (DMEM containing 2% B27 supplement, 10 ng/mL CNTF, and 15 nM T3). siRNA transfection was conducted either 1 day (i.e. 3 days before starting OPC differentiation) or 4 days (i.e. the same day of starting OPC differentiation) after sell seeding..

Transfection with plasmid and siRNA:

OPC was transfected with siRNA Universal negative control (MISSION, Sigma-Aldrich) or siRNA targeted for specific gene suppression using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To validate the transfection ratio OPC was transfected with pCMV-GFP (#11153, Addgene) using Lipofectamine 3000.

Immunocytochemistry:

Cells were fixed using 4% PFA for 15 min. After being washed three times in PBS, they were incubated with BLOCK ACE (DS Pharma Biomedical Co., Ltd) for 1 h. Cells were immunostained with primary antibodies of anti-PDGF-Rα (1:100, R&D), anti-MBP (1:100, Thermo Scientific) and anti-GSTpi (1:200, MBL) and 5-mC (1:100, Abcam) antibodies. Cell counting was performed in a double-blinded counting of labeled cells in the picture taken from well. At least five pictures were taken per well in three wells of each condition.

Quantitative RT-PCR (QRT-PCR):

RNA was isolated with RNeasy Plus Mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized with PrimeScript RT reagent (Takara-Clonetech). QRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex TaqⅡ (Takara-Clonetech) and analyzed with Fast real time system 7500 (Applied Biosystems). Expression levels of each target gene were measured relative to GAPDH as internal control. The following sequences of primers were used: 5’-tccagtatgactctacccacg-3’ for GAPDH forward; 5’-cacgacatactcagcaccag-3’ for GAPDH reverse; 5’-tgtggactctgacaacgcgtacat-3’ for PDGF-Rα forward; 5’- atctctgttcatccaggccacctt-3’ for PDGF-Rα reverse; 5’-actgccaacaacatgcggaagaag-3’ for Myrf forward; 5’-tgggttagaggcccgaacaatgat-3’ for Myrf reverse; 5’-ctactttggcaagagacctcc −3’ for CNP forward; 5’-agagatggacagtttgaaggc-3’ for CNP reverse; 5’-ttgactccatcgggcgcttcttta-3’ for MBP forward; 5’-ttcatcttgggtcctctgcgactt-3’ for MBP reverse; 5’-tctttggcgactacaagaccacca-3’ for PLP forward; 5’-caaacaatgacacacccgctccaa-3’ for PLP reverse; 5’-tcaccgaatccgaatgactcataa −3’ for HDAC1 forward; 5’-ctgggcgaatagaacgcaaga-3’ for HDAC1 reverse; 5’-cggcaagaagaaagtgtgct-3’ for HDAC2 forward; 5’-tccatcgaacactggacagt-3’ for HDAC2 reverse; 5’-ccagatacctaccggttattcg-3’ for DNMT1 forward; 5’-tcctttaactgcagctgaggc-3’ for DNMT1 reverse; 5’-ctgaaatggaaagggtgtttggc-3’ for DNMT3a forward; 5’-ccatgtcccttacacacaagc-3’ for DNMT3a reverse; 5’-gctacatacaggactctgctg-3’ for Nestin forward; 5’-aaactctagactcactggattct −3’ for Nestin reverse; 5’-gagatgatggagctcaatgacc-3’ for GFAP forward; 5’-ctggatctcctcctccagcga −3’ for GFAP reverse; 5’-agctgctcaggacctcaccat-3’ for CX3CR1 forward; 5’-gttgtggaggccctcatggctgat-3’ for CX3CR1 reverse.

Western blotting:

Collected OPCs were subjected to western blot analysis using cell lysis buffer (Pro-PREPTM Protein Extraction Kit, iNtRON Biotechnology). Protein level was measured using BCA protein assay (ThermoFisher), and for each lane, the same amount of protein (10 μg/well) was applied to gel. The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies, and then visualized using ECL chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific). The images were acquired on G-box (SYNGENE). Primary antibodies were used in this study: anti-DNMT1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology (CST)), anti-DNMT3a (1:1000, CST), anti-HDAC1 (1:1000, CST), anti-HDAC2 (1:1000, CST), MBP (1:500, Thermo Scientific) and anti-β-actin (1:5000, Sigma Aldrich). Protein expression level of target was calculated as a ratio relative to β-actin as internal control.

Cellular viability assay:

Cellular viability was quantified by a standard measurement of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) using LDH assay kit (Roche). The ratio of LDH released into the medium to total LDH derived from the medium and adherent cells was measured to validate the amount of cell death.

5-mC DNA methylation assay:

OPC was collected on the day 3 after siRNA transfection. DNA was extracted by using DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN). Total amount of 100 ng DNA was used to quantify the percentage of 5-mC in DNA according to manufactory’s protocol (ZYMO RESEARCH, Irvine, CA).

Statistical analysis:

Statistical significance was evaluated using the unpaired t-test (or Welch’s t-test if the normality of distribution was not assumed) to compare differences between the two groups and a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference test for multiple comparisons. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

Epigenetic regulators in OPC culture:

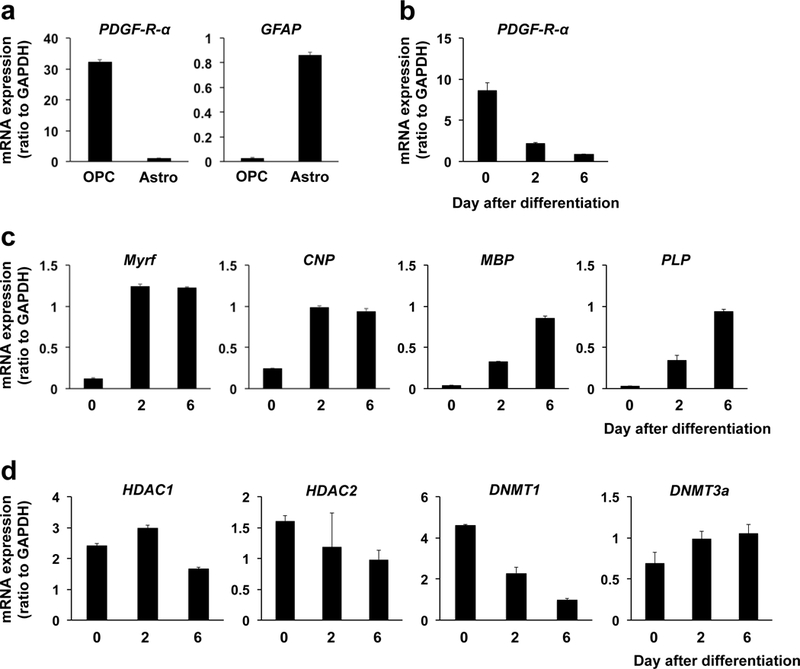

We first checked if our OPC cultures expressed epigenetic regulators. We prepared primary OPC cultures from neonatal rat brain cortex, and as expected, our OPC cultures showed a high level of PDGF-R-alpha mRNA (a OPC marker) but not GFAP mRNA (an astrocyte marker) (Figure 1a). As a positive/negative control, we also prepared primary astrocyte cultures from the same source. As expected, our astrocyte cultures did express the astrocyte marker GFAP but not the OPC marker PDGF-R-alpha (Figure 1a). Our OPC cultures were functional, i.e. they successfully differentiated into oligodendrocytes under some conditions. After switching the culture media from “OPC proliferation media” to “OPC differentiation media”, the mRNA level of PDGF-R-alpha was dramatically decreased (Figure 1b). On the other hand, mRNA levels of the oligodendrocyte markers, such as Myrf, CNP, MBP, and PLP, were all increased over time (Figure 1c). Then, we profiled the expression level of HDAC family (HDAC1–11) and DNMT family (DNMT1, 3a, 3b) in cultured OPCs, astrocytes, and microglia, which were all prepared from neonatal rat brains. As shown in Supplementary Figure S1, mRNA levels of HDAC1, HDAC2, DNMT1 and DNMT3a in OPCs were larger compared to the ones in astrocytes and/or microglia. In addition, at least in our system, mRNA level of DNMT3b was very low and could not be detected. Therefore, in this study, we focused on the roles of these four epigenetic regulators (HDAC1, HDAC2, DNMT1, and DNMT3a) in OPC differentiation. Notably, when OPCs started their differentiation into oligodendrocytes, HDAC1 mRNA level was transiently and slightly increased and then decreased, but HDAC2 mRNA level was gradually decreased (Figure 1e). On the other hand, DNMT1 mRNA level was gradually decreased but DNMT3a mRNA level was increased by OPC differentiation (Figure 1e). These basic data supported the idea that the epigenetic regulators may play differential roles in OPC differentiation.

Figure 1. mRNA expression of epigenetic regulators in OPC culture.

(a) mRNA expressions of PDGF-R-α (OPC marker) and GFAP (astrocyte marker) in cultured OPCs or astrocytes. Data are mean + SD from 3 independent experiments. (b) Expression level for PDGF-R-α was decreased by OPC differentiation. OPC differentiation was started by switching the culture media from “OPC proliferation media” to “OPC differentiation media”. Data are mean + SD from 3 independent experiments. (c) mRNA pattern for oligodendrocyte marker genes (Myrf, CNP, MBP, PLP). Cultured OPCs were initiated for cell differentiation by switching the culture media from “OPC proliferation media” to “OPC differentiation media”. mRNA levels of all the four oligodendrocyte marker genes were increased during the OPC differentiation period. Data are mean + SD from 3 independent experiments. (d) Changes in mRNA levels of epigenetic regulators by OPC differentiation. HDAC1, HDAC2, DNMT1, and DNMT3a showed different patterns in mRNA expression during the cell differentiation period in OPC cultures. Data are mean + SD from 3 independent experiments.

HDACs and OPC differentiation:

To examine the roles of HDACs in OPC differentiation, we transfected siRNAs for HDACs into OPC cultures. Transfection success was verified by confirming that the majority of OPCs were positive with GFP signal when OPC cultures were transfected with pCMV-GFP vector (Supplemental Figure S2). We first transfected siRNA for HDAC1 3 days before starting OPC differentiation. This protocol successfully downregulated the mRNA level of HDAC1 without affecting OPC number at the time when OPCs were initiated for their differentiation (Figure 2a, Supplementary Figure S3a). Also, the protein level of HDAC1 of the cells transfected with HDAC1 siRNA continued to be lower than control-siRNA-transfected-cells at 6 days after OPC differentiation (Figure 2b). During OPC differentiation, cells transfected with control siRNA showed an increase in oligodendrocyte mRNAs, but these increases were suppressed in HDAC1 siRNA pre-treated cells (Figure 2c). In addition, at day 6 after OPC differentiation, the number of MBP/GST-pi double positive cells (both are oligodendrocyte markers) was smaller in HDAC1-siRNA-transfected cells (Figure 2d). HDAC1 siRNA transfected cells did not show any cell damage at day 6 after OPC differentiation (Figure 2e), indicating that HDAC1 downregulation suppressed OPC differentiation without affecting cell survival. Notably, when HDAC1 siRNA was administered at the same time as the start of OPC differentiation, there were no robust changes of mRNA levels of oligodendrocyte markers (Figure 2f) and the number of GST-pi/MBP double positive cells (Figure 2g) on day 6 between control siRNA treated and HDAC1 siRNA treated cells. These data suggest that HDAC1 is important for initiating OPC differentiation.

Figure 2. HDAC1 and OPC survival/differentiation.

(a) OPCs were transfected with either control siRNA or HDAC1 siRNA. Three days later, cells were collected and subjected to QRT-PCR. OPCs with HDAC1 siRNA showed a lower mRNA level of HDAC1. Data are mean + SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (b) OPCs were transfected with either control siRNA or HDAC1 siRNA, and 3 days later, OPCs were started for cell differentiation. Then on day 6 after OPC differentiation, cell lysates were collected and subjected to western blotting. Cells with HDAC1 siRNA showed a lower protein level of HDAC1. Data are mean + SD from 4 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (c) mRNA level for oligodendrocyte marker genes (Myrf, CNP, MBP, PLP). Three days before starting OPC differentiation, OPCs were transfected with either control siRNA or HDAC1 siRNA. Cells with HDAC1 siRNA showed less mRNA levels for oligodendrocyte marker genes over time during the OPC differentiation. Data are mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (d) Concomitantly, on day 6 after OPC differentiation, the number of MBP/GST-pi-double positive oligodendrocytes was lower in the HDAC1 siRNA group. Data are mean + SD from 5 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (e) On day 6 after cell differentiation, there was no difference in cell viability between control-siRNA-treated and HDAC1-siRNA-treated cells. Data are mean + SD from 4 independent experiments. (f) When control or HDAC1 siRNA was transfected at the time for starting OPC differentiation (i.e. day 0), there was no robust change in mRNA level for oligodendrocyte marker genes (Myrf, CNP, MBP, PLP) between control-siRNA-treated and HDAC1-siRNA-treated cells on day 6 after OPC differentiation. Data are mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. (g) Under the siRNA transfection conditions, there was no change in the number of MBP/GST-pi-double positive oligodendrocytes between the two groups on day 6 after OPC differentiation. Data are mean + SD from 5 independent experiments.

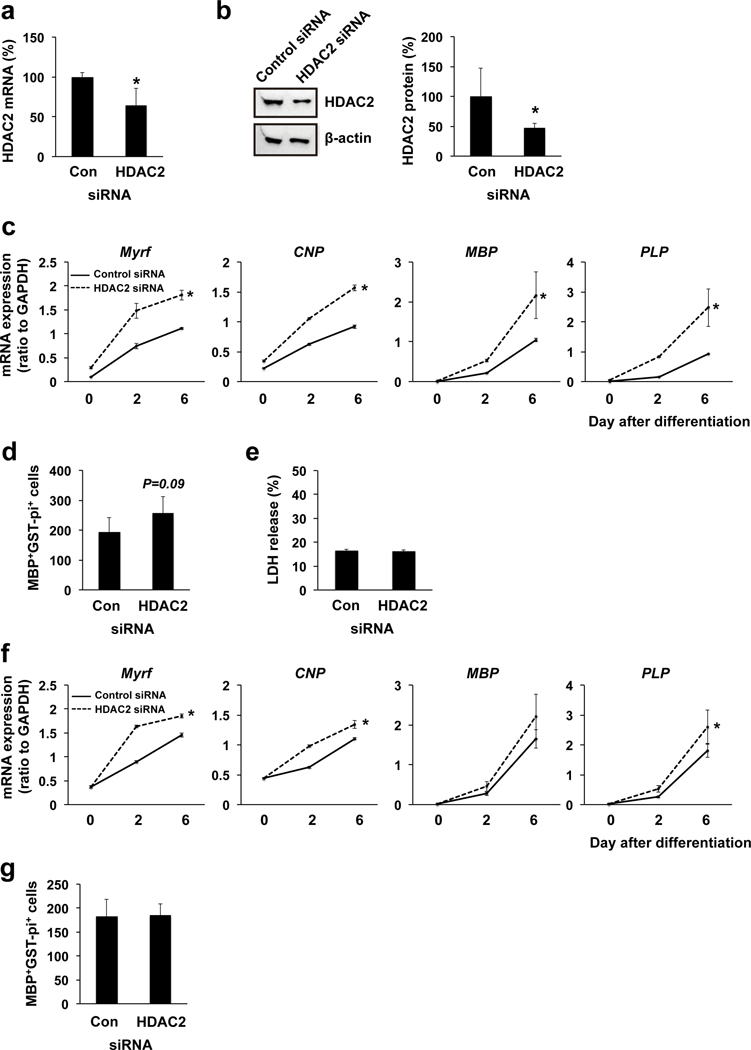

We then repeated the same paradigm of experiments for assessing the roles of HDAC2 in OPC differentiation. When siRNA for HDAC2 was applied 3 days before starting OPC differentiation, the mRNA level of HDAC2 was successfully downregulated without affecting OPC number at the time when OPC differentiation was initiated (Figure 3a, Supplementary Figure S3b). Concomitantly, the protein level of HDAC2 in the cells with HDAC2 siRNA was lower than control siRNA transfected cells at 6 days after OPC differentiation (Figure 3b). OPCs with HDAC2 siRNA showed higher levels of mRNA for oligodendrocyte markers than control siRNA-treated OPCs during the differentiation period (Figure 3c). Similarly, at day 6 after OPC differentiation, the number of MBP/GST-pi double positive cells was larger in the HDAC2 siRNA pre-treated cell group (Figure 3d). HDAC2 siRNA treated cells did not show any cell damage both at day 6 after differentiation (Figure 3e), confirming that HDAC2 downregulation promoted the OPC differentiation without affecting cell survival. When HDAC2 siRNA was administered at the same time as the initiation of OPC differentiation, there were fewer changes in mRNA levels of oligodendrocyte markers (Figure 3f) and no change in the number of GST-pi/MBP double positive cells (Figure 3g) at day 6 between control siRNA treated and HDAC2 siRNA treated cells. These data showed that unlike HDAC1, HDAC2 may play important roles in suppressing OPC differentiation. However, once cells are initiated to differentiate from OPCs to oligodendrocytes, HDAC2 would not show robust effects in suppressing the differentiation cascade in OPCs.

Figure 3. HDAC2 and OPC survival/differentiation.

(a) OPCs were transfected with either control siRNA or HDAC2 siRNA. Three days later, cells were collected and subjected to QRT-PCR. OPCs with HDAC2 siRNA showed less mRNA level of HDAC1. Data are mean + SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (b) OPCs were transfected with either control siRNA or HDAC2 siRNA, and 3 days later, OPCs were started for cell differentiation. Then on day 6 after OPC differentiation, cells were collected and subjected to western blotting. Cells with HDAC2 siRNA showed less protein level of HDAC2. Data are mean + SD from 4 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (c) mRNA level for oligodendrocyte marker genes (Myrf, CNP, MBP, PLP). Three days before starting OPC differentiation, OPCs were transfected with either control siRNA or HDAC2 siRNA. Cells with HDAC2 siRNA showed higher mRNA levels for oligodendrocyte marker genes over time during the OPC differentiation. Data are mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (d) Concomitantly, on day 6 after OPC differentiation, the number of MBP/GST-pi-double positive oligodendrocytes seemed larger in the HDAC2 siRNA group. Data are mean + SD from 5 independent experiments. P=0.09 vs control siRNA group. (e) On day 6 after cell differentiation, there was no difference in cell viability between control-siRNA-treated and HDAC2-siRNA-treated cells. Data are mean + SD from 3 independent experiments. (f) When control or HDAC2 siRNA was transfected at the time for starting OPC differentiation (i.e. day 0), there was slight but significant change in mRNA level for oligodendrocyte marker genes (Myrf, CNP, MBP, PLP) between control-siRNA-treated and HDAC2-siRNA-treated cells on day 6 after OPC differentiation. Data are mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. (g) However, those increases in mRNA level for oligodendrocyte marker genes did not change the number of MBP/GST-pi-double positive oligodendrocytes on day 6 after OPC differentiation. Data are mean + SD from 5 independent experiments.

DNMTs and OPC differentiation:

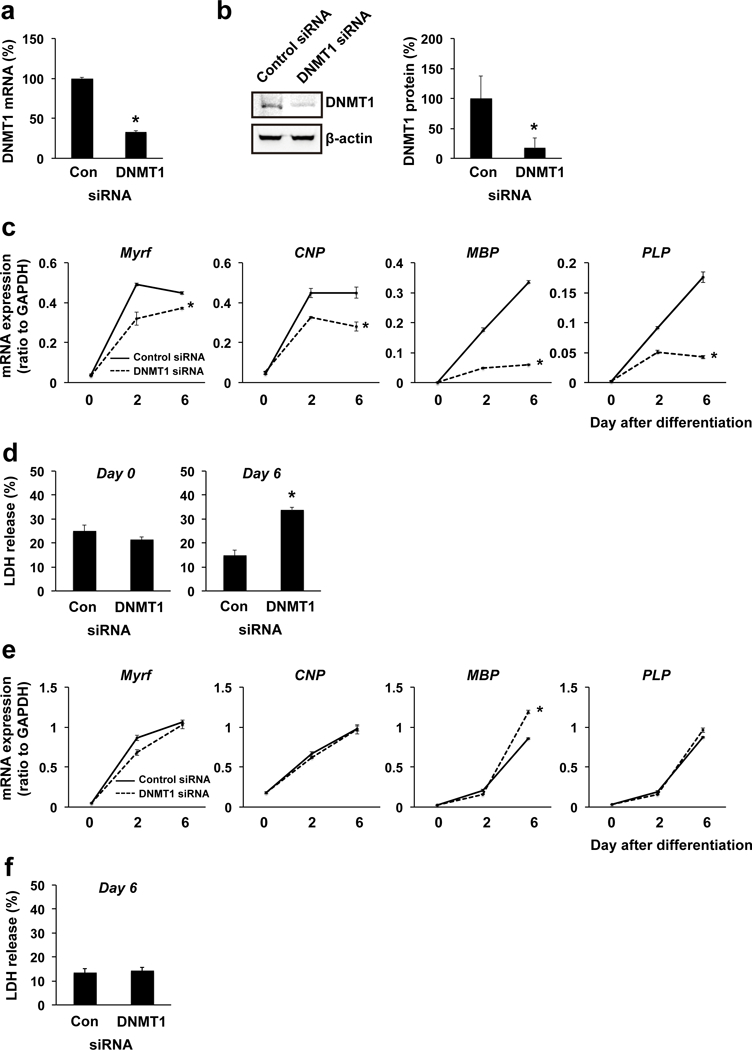

We next examined how DNA methylation was involved in OPC differentiation. When we transfected OPCs with siRNA for DNMT1 3 days before OPC differentiation, the mRNA level of DNMT1 was successfully downregulated at the time when OPCs began differentiation, but no change in OPC number (Figure 4a, Supplementary Figure S3c). Additionally, the protein level of DNMT1 in the cells with DNMT1 siRNA was confirmed to be lower than control siRNA transfected cells at 6 days after OPC differentiation (Figure 4b). In addition, DNMT1 downregulation was confirmed to decrease the percentage of 5-methylated cytosine (5-mC) of genome in OPCs (Supplementary Figure S4), showing that DNMT1 indeed participated in DNA methylation in cultured OPCs. Cells with DNMT1 siRNA exhibited lower mRNA levels of oligodendrocyte markers during the OPC differentiation period (Figure 4c). DNMT1-siRNA-transfected OPCs did not show any cell damage at the time point of starting OPC differentiation (i.e. day 0), but cells transfected with DNMT1 siRNA appeared to be damaged at day 6 after initiating OPC differentiation (Figure 4d). Therefore, DNMT1 downregulation may suppress OPC differentiation via at least partly disturbing cell survival. On the other hand, when DNMT1 siRNA was administered at the same time as the initiation of OPC differentiation, there were no robust changes of mRNA levels of oligodendrocyte markers between control siRNA treated and DNMT1 siRNA treated cells (Figure 4e). Also, under these experimental conditions, cells with DNMT1 siRNA did not show significant cell damage at day 6 after OPC differentiation (Figure 4f), suggesting that DNMT1 expression at the time of initiating OPC differentiation may be critical for maintaining cell survival.

Figure 4. DNMT1 and OPC survival/differentiation.

(a) OPCs were transfected with either control siRNA or DNMT1 siRNA. Three days later, cells were collected and subjected to QRT-PCR. OPCs with DNMT1 siRNA showed a lower mRNA level of DNMT1. Data are mean + SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (b) OPCs were transfected with either control siRNA or DNMT1 siRNA, and 3 days later, OPCs were started for cell differentiation. Then on day 6 after OPC differentiation, cells were collected and subjected to western blotting. Cells with DNMT1 siRNA showed less protein level of DNMT1. Data are mean + SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (c) mRNA level for oligodendrocyte marker genes (Myrf, CNP, MBP, PLP). Three days before starting OPC differentiation, OPCs were transfected with either control siRNA or DNMT1 siRNA. Cells with DNMT1 siRNA showed less mRNA levels for oligodendrocyte marker genes over time during the OPC differentiation. Data are mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (d) OPCs with DNMT1 siRNA did not show any cell damage at day 3 after siRNA treatment. However, when OPCs were started on cell differentiation 3 days after siRNA transfection (i.e. day 0), cells with DNMT1 siRNA showed a larger amount of LDH release (i.e. cell death) at day 6. Data are mean + SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group (e) When control or DNMT1 siRNA was transfected at the time for starting OPC differentiation (i.e. day 0), there was no robust change in mRNA level for oligodendrocyte marker genes (Myrf, CNP, MBP, PLP) between control-siRNA-treated and DNMT1-siRNA-treated cells on day 6 after OPC differentiation. Data are mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group (f) Under the siRNA transfection conditions, there was no change in cell survival between the two groups on day 6 after OPC differentiation. Data are mean + SD from 6 independent experiments.

Similarly, we transfected cultured OPCs with DNMT3a siRNA to assess the roles of DNMT3a in OPC differentiation. When OPCs were transfected with DNMT3a siRNA 3 days before starting OPC differentiation, the mRNA level of DNMT3a was successfully downregulated when OPCs were ready for differentiation (Figure 5a). In addition, DNMT3a downregulation decreased the percentage of 5-methylated cytosine (5-mC) of the genome (Supplementary Figure S4), confirming that DNMT3a also participated in DNA methylation in cultured OPCs. However, 3 days after transfection with DNMT3a siRNA, OPCs with DNMT3a siRNA showed less cell number compared to control-siRNA-treated cells (Figure 5b), suggesting that DNMT3a may be involved in OPC survival/proliferation. When DNMT3a siRNA was administered to the cells at the time of starting OPC differentiation, the DNMT3a mRNA level was decreased at day 6 (Figure 5c) and the number of MBP/GST-pi-positive oligodendrocytes was not changed at day 6 (Figure 5d). In addition, cells with DNMT3a siRNA did not show any significant changes in mRNA levels of oligodendrocyte markers compared to cells with control siRNA (Figure 5e). Taken together, these data suggest that DNMT3a may be involved in OPC proliferation/survival, but after cells are initiated for differentiating into oligodendrocytes, DNMT3a may not be heavily involved in the process of cell differentiation and survival.

Figure 5. DNMT3a and OPC survival/differentiation.

OPCs were transfected with either control siRNA or DNMT3a siRNA. Three days later, cells were collected and subjected to QRT-PCR. OPCs with DNMT3a siRNA showed less mRNA level of DNMT1. Data are mean + SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (b) Three days after siRNA treatment, the number of PDGF-R-α-positive OPCs in the DNMT3a-siRNA group was lower compared to the one in the control-siRNA group. Data are mean + SD from 5 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group. (c) When control or DNMT3a siRNA was transfected at the time for starting OPC differentiation (i.e. day 0), cells with DNMT3a siRNA showed less mRNA level for DNMT3a on day 6 after OPC differentiation. Data are mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control siRNA group (d) Under the siRNA transfection conditions, there was no change in the number of MBP/GST-pi-positive oligodendrocytes between the two groups on day 6 after OPC differentiation. Data are mean + SD from 5 independent experiments. (e) Concomitantly, there was no change in mRNA level for oligodendrocyte marker genes (Myrf, CNP, MBP, PLP) between the two groups during the OPC differentiation. Data are mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments.

Discussion:

Oligodendrocytes play an essential role in fast impulse propagation in the central nervous system by generating the myelin sheath that allows rapid conduction of action potentials along axons. Because oligodendrocytes do not proliferate, OPC proliferation and differentiation into oligodendrocytes are essential steps for proper central nervous system network during development. Even in adult brain, OPCs are widely distributed, comprising approximately 5% of all brain cells (Dawson et al. 2003; Levine et al. 2001; Pringle et al. 1992). These residual OPCs in adult brain are relatively quiescent, but after brain damage, they rapidly proliferate and differentiate into mature oligodendrocytes to restore myelin sheaths (Gensert and Goldman 1997; Miyamoto et al. 2010; Skihar et al. 2009; Stetler et al. 2016). The underlying mechanisms of OPC differentiation have been extensively examined, and several extracellular molecules are identified to promote OPC differentiation (Domingues et al. 2017; Takebayashi and Ikenaka 2015; Zhang et al. 2016). In addition, the phase-specific expression pattern of transcriptional factors is also well recognized in the function of oligodendrocyte lineage cells (Goldman and Kuypers 2015). By comparison, how epigenetic regulators contribute to OPC differentiation has been still relatively unknown and understudied. In this study, we show for the first time that in culture conditions, HDAC1, HDAC2, DNMT1, and DNMT3a are predominantly expressed in OPCs compared to other glial cells, such as astrocytes and microglia. Also, as summarized in Supplementary Figure S5, our study demonstrates the differential roles of these epigenetic regulators in OPC survival and differentiation.

As noted in the introduction section, HDACs deacetylate lysine resides of histones and have been shown to be involved in OPC differentiation. For example, HDAC inhibiters were confirmed to suppress OPC differentiation both under developmental stage and under diseased conditions in adult CNS (Lyssiotis et al. 2007; Shen et al. 2008). In addition, another study demonstrated that HDAC1/2 double-knockdown in OPCs suppressed OPC differentiation during perinatal period in vivo (Ye et al. 2009). In our in vitro cell culture system, HDAC1/2 double-knockdown indeed suppressed OPC differentiation (Supplementary Figure S6). Also recently, another study showed that although HDAC11 expression was low in OPCs under resting state, the expression level of HDAC11 would be increased during strain-induced oligodendrocyte maturation (Jagielska et al. 2017). Our current study supports and may expand these findings. One of the novel insights from this study is that HDAC1 and HDAC2 are predominantly expressed in OPCs compared to other HDACs. In addition, although both HDAC1 and HDAC2 belong to the Class I HDAC family, their actions on OPC differentiation appeared to be different, i.e. HDAC1 seems to promote OPC differentiation, while HDAC2 may inhibit OPC differentiation. In this study, however, we have not revealed yet why and how HDAC1 and HDA2 exhibit opposite effects on OPC differentiation. Future studies would be warranted to investigate the underlying mechanisms for this point.

Another novel finding in this study is to show how DNMTs are involved in OPC function, i.e. DNMT1 participates in OPC differentiation, DNMT3a is involved in OPC survival/proliferation, and DNMT3b is not extensively expressed in OPCs. As explained in the introduction section, DNMT1 maintains the methylation and DNMT3a/3b perform de novo methylation. Past studies showed that DNMT1 knockout mice are embryonic lethal (Li et al. 1992) and DMNT3a/3b knockout mice develop to term but die within a few weeks after birth (Okano et al. 1999). Recently, using DNMT-mutant embryonic stem cells, DNMT1 was shown to be essential for cell viability in undifferentiated stem cells (Liao et al. 2015). In addition, another study reported that DNMT3a would promote cell proliferation by accelerating the G1/S transition in gastric carcinogenesis (Cui et al. 2015). Thus far, roles of DNMTs in OPC function are mostly unknown, but recently, Mayon et al. demonstrated that DNMT1 would be important for OPC differentiation during prenatal stage (Moyon et al. 2016). Our current study implies that the general roles of DNMTs in stem cells (i.e. DNMT1 for cell viability and DNMT3a for cell proliferation) may apply for OPCs as well, and also supports the previous finding that DNMT1 is involved in OPC differentiation. However, the precise mechanisms as to how and why DNMT1 and DNMT3a play different roles in OPC function still remain unknown. Therefore, future studies are awaited to reveal the underlying mechanisms for deeply understanding the roles of epigenetic regulators in oligodendrocyte homeostasis.

Our study may also have important clinical implications because DNMT dysfunction is closely related to central nervous system disorders. In human, mutations of DNMT1 cause hereditary sensory neuropathy with dementia and hearing loss (Klein et al. 2011) or autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness and narcolepsy (Winkelmann et al. 2012). In animal models, deletion of DNMT1 leads to embryonic lethality and conditional knockout of either DNMT1 or DNMT3a in post-mitotic neuron of forebrain results in abnormal hippocampal CA1 long-term plasticity and deficits of learning and memory (Feng et al. 2010). In addition, disruption or mutation of methyl-CpG binding domain protein 2 (MECP2), which binds to methylated DNA sites in the methylated gene promoters, causes the X-linked Rett syndrome; a neurological disorder associated with axon growth deficiency and autistic symptoms (Gabel et al. 2015). On the other hand, DNA methylation may also adversely affect neuronal recovery after the central nervous system injury. DNA methylation is increased after brain ischemia in a DNMT1-activity-dependent manner, and mice with a heterozygous mutation for DNMT1 are resistant to mild ischemic damage (Endres et al. 2000). Although these studies focused on DNMT roles in neuronal function, our current study revealed that DNMTs also regulate the cell survival and differentiation of oligodendrocyte lineage cells. Because oligodendrocyte lineage cells are the major cell types in cerebral white matter, DNMTs can be a novel therapeutic target for white matter-related diseases.

Taken together, we have demonstrated that each epigenetic regulator has different roles in OPC differentiation. Nevertheless, there are some important caveats and limitations that need to be considered for future studies. First, although some epigenetic regulators may interact with each other, we did not examine whether different epigenetic regulators interact to promote/inhibit OPC differentiation. A previous study showed that DNMT1 multi-functionally would work as a transcriptional repressor and bind to HDAC2 under some conditions (Rountree et al. 2000). Therefore, future studies are warranted to co-knockdown HDAC(s) with DNMT(s) in cultured OPCs to see if those epigenetic regulators independently or cooperatively affect OPC differentiation. Second, although we showed that the percentage of 5-mC of genome was dependent in the function of DNMT1 and/or DNMT3a in cultured OPCs, we did not identify the methylation target region in the genome required for OPC differentiation. DNA methylation generally promotes gene repression, and therefore, the methylation target might be the positive transcriptional regulator for OPC such as Olig2 (Lu et al. 2000; Takebayashi et al. 2000; Zhou et al. 2000) or the negative one for oligodendrocytes such as Hes5 (Liu et al. 2006). However, our pilot experiments did not detect any association of the expression of between DNMT1 and Olig2 or Hes5 (data not shown). To understand the precise function of DNA methylation in the process of OPC differentiation, it would be necessary to identify the specific region(s) in whole genome for gene expression of oligodendrocyte linage cells. And finally, our cell culture experiments were conducted in well-controlled conditions. In the cell culture media, there were only favorable trophic factors that support OPC survival and differentiation. However, in brain, several kinds of factors including deleterious ones may exist around OPCs, and the repertoire of those factors may change depending on the context. Because extracellular signaling would change the expression patterns of epigenetic regulators, future studies need to examine whether the mechanisms observed in this study are indeed preserved in complex in vivo situations, especially under diseased conditions.

In summary, we report for the first time that epigenetic regulators - HDAC1, HDAC2, DNMT1, and DNMT3a - are all critical in OPC survival and differentiation. These regulators may possess different roles in the process of cell differentiation in OPCs. OPCs play important roles in supplementing mature oligodendrocytes during development and/or after oligodendrocyte/myelin damage, and a deeper understanding of the mechanism of OPC differentiation could lead to the development of new therapies for white matter-related diseases.

Supplementary Material

Main Points:

-

–

Epigenetic regulators play important roles in OPC function

-

–

HDAC1 and HDAC2 have opposite effects in OPC differentiation

-

–

DNMT1 and DNMT3a contribute to cell survival of oligodendrocyte lineage cells

Acknowledgements:

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health, Brain Science Foundation, and JSPS Overseas Research Fellowships. The authors thank Drs. Ryo Ohtomo, Gen Hamanaka, and Hajime Takase for many helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure:

None

References:

- Cui H, Zhao C, Gong P, Wang L, Wu H, Zhang K, Zhou R, Wang L, Zhang T, Zhong Sand others. 2015. DNA methyltransferase 3A promotes cell proliferation by silencing CDK inhibitor p18INK4C in gastric carcinogenesis. Sci Rep 5:13781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson MR, Polito A, Levine JM, Reynolds R. 2003. NG2-expressing glial progenitor cells: an abundant and widespread population of cycling cells in the adult rat CNS. Mol Cell Neurosci 24:476–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingues HS, Cruz A, Chan JR, Relvas JB, Rubinstein B, Pinto IM. 2017. Mechanical plasticity during oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Glia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas JC, Tai YC, Speed TP, Ngai J, Barres BA. 2006. Functional genomic analysis of oligodendrocyte differentiation. J Neurosci 26:10967–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres M, Meisel A, Biniszkiewicz D, Namura S, Prass K, Ruscher K, Lipski A, Jaenisch R, Moskowitz MA, Dirnagl U. 2000. DNA methyltransferase contributes to delayed ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci 20:3175–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Zhou Y, Campbell SL, Le T, Li E, Sweatt JD, Silva AJ, Fan G. 2010. Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a maintain DNA methylation and regulate synaptic function in adult forebrain neurons. Nat Neurosci 13:423–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel HW, Kinde B, Stroud H, Gilbert CS, Harmin DA, Kastan NR, Hemberg M, Ebert DH, Greenberg ME. 2015. Disruption of DNA-methylation-dependent long gene repression in Rett syndrome. Nature 522:89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensert JM, Goldman JE. 1997. Endogenous progenitors remyelinate demyelinated axons in the adult CNS. Neuron 19:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman SA, Kuypers NJ. 2015. How to make an oligodendrocyte. Development 142:3983–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N, Niu J, Feng Y, Xiao L. 2015. Oligodendroglial Development: New Roles for Chromatin Accessibility. Neuroscientist 21:579–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K, Maki T, Shindo A, Egawa N, Liang AC, Itoh N, Lo EH, Lok J, Arai K. 2016. Magnesium sulfate protects oligodendrocyte lineage cells in a rat cell-culture model of hypoxic-ischemic injury. Neurosci Res 106:66–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagielska A, Lowe AL, Makhija E, Wroblewska L, Guck J, Franklin RJM, Shivashankar GV, Van Vliet KJ. 2017. Mechanical Strain Promotes Oligodendrocyte Differentiation by Global Changes of Gene Expression. Front Cell Neurosci 11:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassis H, Chopp M, Liu XS, Shehadah A, Roberts C, Zhang ZG. 2014. Histone deacetylase expression in white matter oligodendrocytes after stroke. Neurochem Int 77:17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein CJ, Botuyan MV, Wu Y, Ward CJ, Nicholson GA, Hammans S, Hojo K, Yamanishi H, Karpf AR, Wallace DCand others. 2011. Mutations in DNMT1 cause hereditary sensory neuropathy with dementia and hearing loss. Nat Genet 43:595–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JM, Reynolds R, Fawcett JW. 2001. The oligodendrocyte precursor cell in health and disease. Trends Neurosci 24:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E, Bestor TH, Jaenisch R. 1992. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell 69:915–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J, Karnik R, Gu H, Ziller MJ, Clement K, Tsankov AM, Akopian V, Gifford CA, Donaghey J, Galonska C and others. 2015. Targeted disruption of DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B in human embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet 47:469–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Han YR, Li J, Sun D, Ouyang M, Plummer MR, Casaccia-Bonnefil P. 2007. The glial or neuronal fate choice of oligodendrocyte progenitors is modulated by their ability to acquire an epigenetic memory. J Neurosci 27:7339–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Li J, Marin-Husstege M, Kageyama R, Fan Y, Gelinas C, Casaccia-Bonnefil P. 2006. A molecular insight of Hes5-dependent inhibition of myelin gene expression: old partners and new players. EMBO J 25:4833–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu QR, Yuk D, Alberta JA, Zhu Z, Pawlitzky I, Chan J, McMahon AP, Stiles CD, Rowitch DH. 2000. Sonic hedgehog--regulated oligodendrocyte lineage genes encoding bHLH proteins in the mammalian central nervous system. Neuron 25:317–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyssiotis CA, Walker J, Wu C, Kondo T, Schultz PG, Wu X. 2007. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity induces developmental plasticity in oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:14982–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto N, Maki T, Shindo A, Liang AC, Maeda M, Egawa N, Itoh K, Lo EK, Lok J, Ihara M and others. 2015. Astrocytes Promote Oligodendrogenesis after White Matter Damage via Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. J Neurosci 35:14002–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto N, Tanaka R, Shimura H, Watanabe T, Mori H, Onodera M, Mochizuki H, Hattori N, Urabe T. 2010. Phosphodiesterase III inhibition promotes differentiation and survival of oligodendrocyte progenitors and enhances regeneration of ischemic white matter lesions in the adult mammalian brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30:299–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyon S, Huynh JL, Dutta D, Zhang F, Ma D, Yoo S, Lawrence R, Wegner M, John GR, Emery B and others. 2016. Functional Characterization of DNA Methylation in the Oligodendrocyte Lineage. Cell Rep 15:748–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA, Li E. 1999. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell 99:247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle NP, Mudhar HS, Collarini EJ, Richardson WD. 1992. PDGF receptors in the rat CNS: during late neurogenesis, PDGF alpha-receptor expression appears to be restricted to glial cells of the oligodendrocyte lineage. Development 115:535–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rountree MR, Bachman KE, Baylin SB. 2000. DNMT1 binds HDAC2 and a new co-repressor, DMAP1, to form a complex at replication foci. Nat Genet 25:269–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S, Li J, Casaccia-Bonnefil P. 2005. Histone modifications affect timing of oligodendrocyte progenitor differentiation in the developing rat brain. J Cell Biol 169:577–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S, Sandoval J, Swiss VA, Li J, Dupree J, Franklin RJ, Casaccia-Bonnefil P. 2008. Age-dependent epigenetic control of differentiation inhibitors is critical for remyelination efficiency. Nat Neurosci 11:1024–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skihar V, Silva C, Chojnacki A, Doring A, Stallcup WB, Weiss S, Yong VW. 2009. Promoting oligodendrogenesis and myelin repair using the multiple sclerosis medication glatiramer acetate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:17992–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetler RA, Gao Y, Leak RK, Weng Z, Shi Y, Zhang L, Pu H, Zhang F, Hu X, Hassan S and others. 2016. APE1/Ref-1 facilitates recovery of gray and white matter and neurological function after mild stroke injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E3558–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi H, Ikenaka K. 2015. Oligodendrocyte generation during mouse development. Glia 63:1350–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi H, Yoshida S, Sugimori M, Kosako H, Kominami R, Nakafuku M, Nabeshima Y. 2000. Dynamic expression of basic helix-loop-helix Olig family members: implication of Olig2 in neuron and oligodendrocyte differentiation and identification of a new member, Olig3. Mech Dev 99:143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann J, Lin L, Schormair B, Kornum BR, Faraco J, Plazzi G, Melberg A, Cornelio F, Urban AE, Pizza F and others. 2012. Mutations in DNMT1 cause autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness and narcolepsy. Hum Mol Genet 21:2205–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao B, Christian KM, He C, Jin P, Ming GL, Song H. 2016. Epigenetic mechanisms in neurogenesis. Nat Rev Neurosci 17:537–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye F, Chen Y, Hoang T, Montgomery RL, Zhao XH, Bu H, Hu T, Taketo MM, van Es JH, Clevers H and others. 2009. HDAC1 and HDAC2 regulate oligodendrocyte differentiation by disrupting the beta-catenin-TCF interaction. Nat Neurosci 12:829–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Zhang Z, Chopp M. 2016. Function of neural stem cells in ischemic brain repair processes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 36:2034–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Wang S, Anderson DJ. 2000. Identification of a novel family of oligodendrocyte lineage-specific basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Neuron 25:331–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.