Abstract

At the molecular level, our knowledge of the low voltage-activated Ca2+ channel (T-type) has made little progress. Using an antisense strategy, we investigated the possibility that the T-type channels have a structure similar to high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels. It is assumed that high voltage-activated channels are made of at least three components: a pore forming α1 subunit combined with a cytoplasmic modulatory β subunit and a primarily extracellular α2δ subunit. We have examined the effect of transfecting cranial primary sensory neurons with generic anti-β antisense oligonucleotides. We show that in this cell type, blocking expression of all known β gene products does not affect T-type current, although it greatly decreases the current amplitude of high voltage-activated channels and modifies their voltage dependence. This suggests that β subunits are likely not constitutive of T-type Ca2+ channels in this cell type.

Keywords: T-type Ca2+ current, HVA Ca2+ currents, sensory neurons, β subunit, antisense oligonucleotide, polyethylenimine

The low voltage-activated Ca2+ (LVA or T-type) currents have been the focus of a great deal of interest. Because they are activated above the resting potential of the membrane, they are assumed to boost synaptic signals and to be responsible for the generation of repetitive firing activity or intrinsic neuronal oscillations and of most for the Ca2+ entry accompanying the spike activity (for review, see Huguenard, 1996). The structure of the Ca2+ channels generating the various LVA currents is still unknown. Because of recent progress in the knowledge of the molecular structure of the high voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels, it is now possible to determine whether T-type channels are formed by a particular combination of already identified subunits or more generally whether they are structurally similar to hetero-oligomeric HVA Ca2+channels (Perez-Reyes and Schneider, 1994; De Waard et al., 1996).

The precise structures of all neuronal channels underlying the various HVA Ca2+ currents have not been unambiguously established, but it is generally assumed that these channels are formed from at least four constitutive subunits: α1(A, B, C, D, or E), β (1, 2, 3, or 4), α2, and δ (Takahashi et al., 1987; Witcher et al., 1993). The last two are cross-linked by a disulfide bridge and arise from the same precursor. Although the distinct biophysical and pharmacological properties of each channel are imposed primarily by the corresponding pore-forming α1 subunit, further diversity is introduced by the ancillary subunits (mainly the β subunits) associated with the channel. The β subunit, which is entirely cytoplasmic, has been shown to increase the peak current amplitude, to shift activation/inactivation curves toward more hyperpolarized potentials, and to alter kinetics of activation and inactivation (Mikami et al., 1989; Wei et al., 1991; Perez-Reyes et al., 1992;Castellano et al., 1993a,b; Stea et al., 1993; Tomlinson et al., 1993;De Waard and Campbell, 1995; Bourinet et al., 1996). Because a single α2δ gene is expressed in neurons, no major diversity is likely to arise from this latter subunit, which increases the current generated by any α1 subunit and potentiates the stimulatory response of β subunits (Brust et al., 1993; Shistik et al., 1995; Wei et al., 1995; Gurnett et al., 1996).

T-type currents do not differ fundamentally from other Ca2+ currents. Like HVA Ca2+channels, T-type channels are selectively permeable to divalent cations, provided that a minimal concentration of divalent cations is present in the external medium. For LVA currents, this minimal Ca2+ concentration is 25 μm (Lux et al., 1990), and for HVA currents it is 1 μm (Kostyuk et al., 1983; Almers and McCleskey, 1984; Hess and Tsien, 1984). The T-type current saturates with a KD of ∼10 mm Ca2+ (Bossu et al., 1985), similar to the value (15 mm) reported for HVA currents (Hess et al., 1986; De Waard et al., 1995). The corresponding channels differ in their relative permeability to divalent cations. HVA channels are characteristically more permeable to Ba2+ than to Ca2+, with an anomalous molar fraction effect when the channel conductance is examined under bi-ionic (Ca2+ and Ba2+) conditions (Hess et al., 1986; Armstrong and Neyton, 1992; but also see Yue and Marban, 1990). T-type channels are equally or slightly less permeable to Ba2+ than to Ca2+ (Bossu et al., 1985; Bossu and Feltz, 1986; Carbone and Lux, 1987). T-type channels can also be characterized by their slower activation/inactivation and deactivation kinetics and their relatively higher sensitivity to Ni2+ (Carbone and Lux, 1984; Nowycky et al., 1985;Carbone and Lux, 1987; Carbone et al., 1987). Thus, in spite of the differences between LVA and HVA Ca2+ currents, their properties are close enough to suggest that T-type channels may belong to the same channel family as HVA channels and may have a similar molecular structure. Therefore, it is important to determine whether β subunits are a likely component of these channels by contributing to T-type current properties and thereby increasing their diversity. Here, using an antisense strategy (Lambert et al., 1996) in cranial sensory neurons, we show that blockade of β subunit synthesis greatly modifies HVA currents but does not alter the characteristics of the T-type current recorded in these cells. The data suggest that β subunits are not a component of the T-type channels present in cranial sensory neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfection. A detailed dissociation procedure has been described previously (Bossu et al., 1985). Briefly, desheathed nodosus ganglia were mechanically dissociated after a 30 min enzymatic treatment at 37°C in a solution containing 1 mg/ml dispase (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) and 1 mg/ml type IV collagenase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Dissociated cells were plated on collagen-coated petri dishes and allowed to develop in L15 medium for 12 hr before a 4 hr exposure to 4.10−4m fluorodeoxyuridine (Sigma) to prevent excessive glial growth over the 8 d required to carry out the full experiment. Three days after plating, cells were transfected by a recently reported procedure (Lambert et al., 1996) using polyethylenimine (50 kDa PEI; Sigma) as the transfecting agent. Cells were exposed for 4 hr to a 300 nm 5′-fluorescent generic anti-β antisense oligonucleotide (ON) (see sequence in Fig.3B) or a 5′-fluorescent scrambled ON (5′-ACCTCGCATCCCTAGCACCACTGATT-3′). All ONs have phosphorothioate linkages in all positions. PEI was added to reach a ratio of PEI nitrogen per DNA phosphate equal to 10.

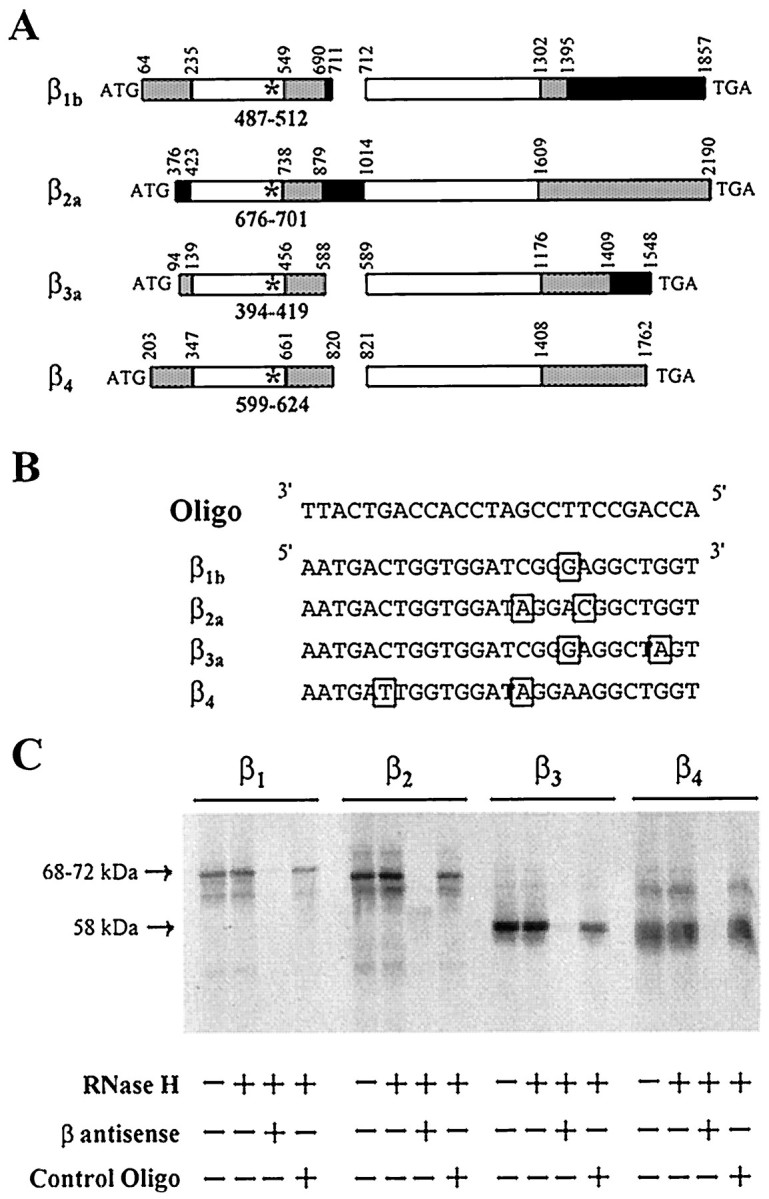

Fig. 3.

Synthesis of all β1–4 gene products is blocked by the selected antisense ON. A, Mapping of the 26 mer antisense ON on the rat β subtypes sequences.Star, Position of the sequence complementary to the β antisense ON; empty boxes, domains highly conserved throughout all β subtypes; gray boxes, domains conserved among single β subtypes; black boxes, domain subject to alternative splicing and/or cross species divergences. The diagram is to scale; gaps have been inserted to maintain the alignment of conserved sequences. Numbers refer to nucleotide positions in published cDNA sequences: β1b, GenBank nucleotide access number X61394 (Pragnell et al., 1991); β2a, M80545 (Perez-Reyes et al., 1992); β3a, M88751 (Castellano et al., 1993a); β4, L02315 (Castellano et al., 1993b).B, Alignment of the antisense ON sequence with the corresponding rat β nucleotide sequences. Sequence mismatches are shown in boxes. C, In vitro coupled transcription–translation of four different β subunit plasmids (β1b, β2a, β3a, and β4) is blocked by the addition of antisense ON (lane 3). Lanes 2 and 4 show that the translation of intact β subunits is not affected by the addition of RNase H (lane 2) or RNase H with a scrambled ON (lane 4,Control Oligo). Molecular weights for β1b, β2a (68–72 kDa), and β3-β4 (58 kDa) are indicated on theleft.

Electrophysiology. Transfected cells were identified by the fluorescence of their nucleus by conventional fluorescence microscopy. Currents were recorded using an Axopatch 200A amplifier and pClamp6 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) in the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique. Current traces were obtained using a sampling frequency of 10 kHz and were analyzed after filtering at 1 kHz with a digital Gaussian filter. To separate the low and high threshold-activated Ca2+ currents optimally, 10 mm Ca2+ as divalent ions was added to the bath solution otherwise containing (in mm): trichloroacetate 110, HEPES 10, and tetraethylammonium chloride 10, adjusted to pH 7.4 with Tris-base. Pipette solution imposed an intracellular medium containing (in mm): HEPES 95, CaCl2 3, EGTA 30, NaCl 5, MgATP 1, and GTP 0.2, adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH. Cell capacitance was estimated by applying 5 mV hyperpolarizing steps from a holding potential of −80 mV. Capacitance was estimated from the time constant of the decay phase of the evoked transient (sampled at 100 kHz). This transient allowed also a precise determination of the access resistance indicating mean value of 14.3 ± 0.4 MΩ (n = 88). Compensation of the cell capacitance and series resistance was above 70%. In each cell, current density was measured by constructing severalI–V curves, with successive 200 msec depolarizing steps ranging from −60 to 50 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV and an increment of 5 mV. Data reported are mean ± SEM.

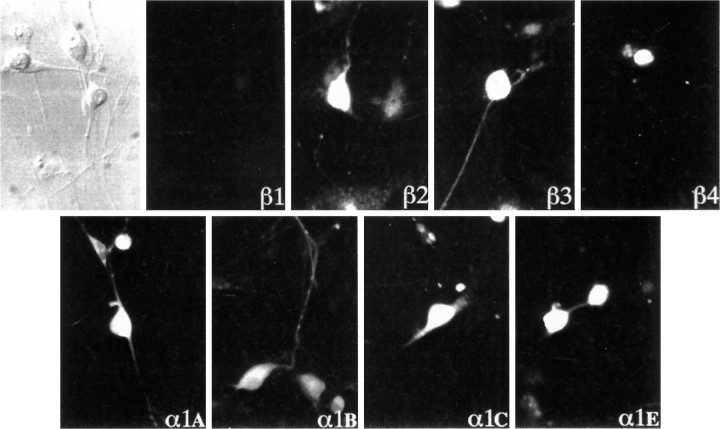

Immunocytology. Expression of endogenous Ca2+ channels in nodosus ganglion neurons was assessed by immunofluorescence using a panel of subtype-specific polyclonal antisera to α1 and β subunits. Three polyclonal antisera specific for human α1A, α1B, and α1E prepared in rabbits against unique sequences present in the cytoplasmic loop between IIS6 and IIIS1 (Volsen et al., 1995) were used. In addition, an anti-α1C rat polyclonal antibody directed against the C-terminal region of the rat protein was used. To assess β subunit expression, four polyclonal antisera specific for human β1, β2, β3, and β4 were used. The preparation and detailed characterization of these reagents is described elsewhere (Volsen et al., 1997).

Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins were prepared against amino acid sequences comprising the C terminus of each β subunit. For β2, β3, and β4 subunits, class-specific immunogens were selected to encode a sequence conserved between splice variants. For the β1 subunit, the polypeptide immunogen was designed from the sequence of the β1b splice variant. All β antisera were extensively purified and characterized. Briefly, the immunoglobulin fraction from each serum was purified by protein A-Sepharose chromatography. This was followed by immunoaffinity purification with the relevant fusion protein. Cross-reactivity was monitored by ELISA, and any observed cross-reactivity was removed using additional immunoaffinity columns. Finally, specificity was verified by immunofluorescent staining of human epithelial kidney cell (HEK 293) stably transfected with constructs of human α1, α2δ, and β subunits and untransfected HEK as negative controls and by Western blot analysis.

Immunofluorescence characterization was performed on neurons maintained in culture and fixed at the indicated day by direct application of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min. After washing in PBS the fixed neurons were then permeabilized with freshly prepared 10% v/v acetic acid in ethanol at −20°C for 20 min. One wash with PBS was followed by the addition of a blocking buffer (10% v/v goat serum/PBS) for 30 min. This blocking buffer was used as a diluent and wash solution for all subsequent steps. Primary antibodies were applied at the appropriate concentration (α1A, B, E at 4 μg/ml; β1–4 and α1C at 10 μg/ml) and incubated for 1 hr at room temperature. After washing, a FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Southern Biotechnologies, Birmingham, AL) was applied, and it was incubated in the dark for an additional hour. After further washing, the coverslip was mounted on a slide and examined by fluorescence microscopy.

In vitro transcription/translation experiments and ON-induced inhibition. The 35S-labeled β subunits were synthesized by coupled in vitro transcription and translation using the TNT system from Promega (Madison, WI). Four different cDNA plasmids were used that encoded the rat β1b and β4 (GenBank accession numbersX61394 and L02315) and rabbit β2a and β3(X64297, M88751). The reactions were conducted at 30°C for 2 hr under various conditions: with RNase H (Promega) at 0.1 U/μl with or without 300 nm ON (scrambled or anti-β antisense). Samples (2 μl) of the final products were analyzed on 9% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Gels were then dried and exposed overnight to films (Kodak X-Omat AR). Binding of the in vitro translated35S-labeled β subunits to the α1 interaction domain of the α1C subunit (AID) GST- or to control GST-fusion proteins was performed as described previously (De Waard et al., 1995). Briefly, 1 μm control GST or AID–GST fusion protein was coupled to glutathione beads and incubated overnight with 2 μl of translated 35S-labeled β subunits at 4°C. The beads were then washed four times with PBS, and the radioactivity was determined by β counting. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting binding to GST from binding to AID–GST. Reduction in β subunits synthesis induced by the antisense ON was determined by calculating the percentage reduction in specific binding of35S-labeled β subunits to AID–GST.

RESULTS

Ca2+ currents in nodosus ganglion neurons

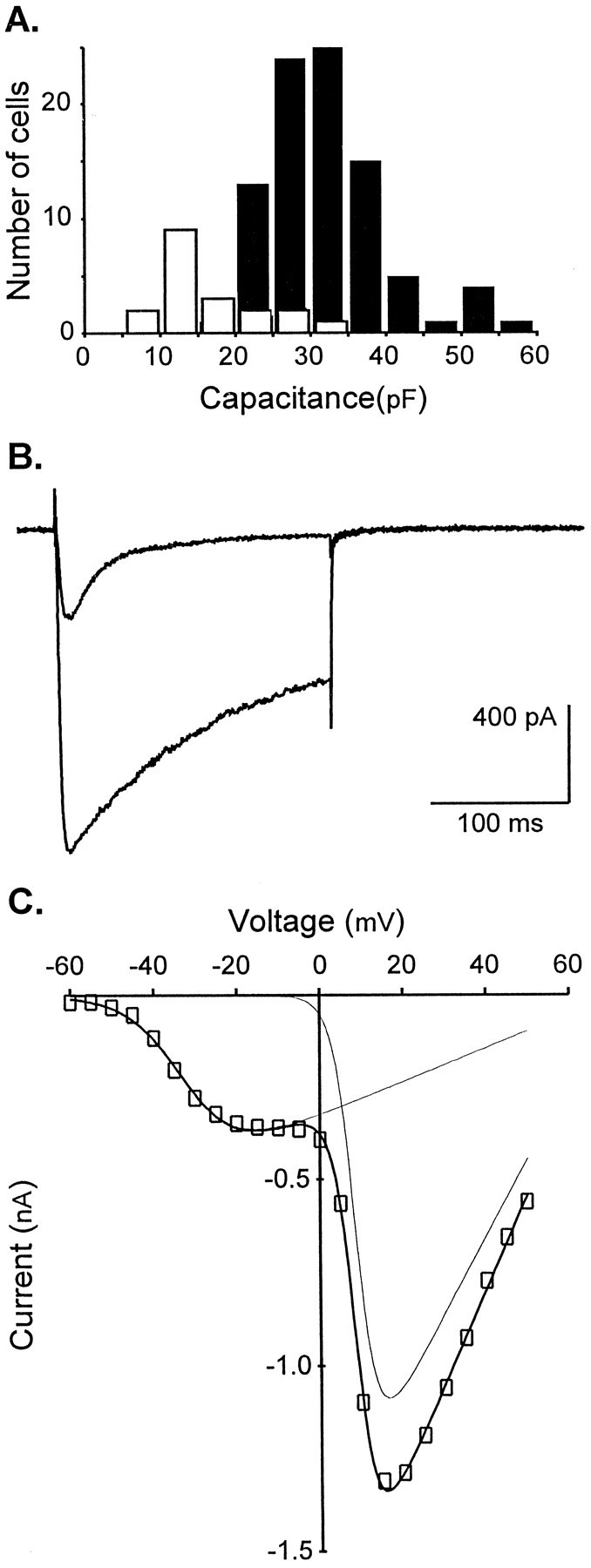

As illustrated in Figure1A, rat nodosus ganglion neurons with an LVA Ca2+ current can be easily identified by their large size. In these cells, depolarizing steps ranging from −60 to −15 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV elicit a transient (T-type) current, whereas depolarizations to higher potentials evoke a maintained (HVA) current (Fig.1B). As shown previously in this preparation (Bossu et al., 1985), the LVA current is generated by a single channel population. The T-type current density was fairly constant over the 9 d in vitro (see Fig. 4B) that we examined, and its mean value was −12.0 ± 0.8 pA/pF (n = 45) at −15mV. This channel inactivates with time and membrane potential (Bossu and Feltz, 1986). Its activation curve and hence its I–V relationship can be fitted by a Boltzmann equation with a voltage for half activation of −29.2 ± 1.1 mV (n = 44) (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the HVA current is of composite origin. Ca2+currents subtypes are probably similar in nodosus ganglion neurons and in primary sensory neurons of dorsal root ganglion (Mintz et al., 1992), with N-, P/Q-, and L-type components. These various components activate differentially at distinct potentials with specific kinetics, and the respective steady-state inactivations occur at different potentials with a pronounced sensitivity to cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration (not illustrated). Although theoretically unsound, however, the Boltzmann equation was used to describe the composite HVA current for phenomenological purposes. Using such a fitting procedure with two Boltzmann equations (Fig.1C), we show that under our recording conditions the LVA and HVA currents can be recorded almost in isolation. At −15 mV, the current recorded is only T-type, and its amplitude is close to its peak value.

Fig. 1.

T-type Ca2+ current characteristics in sensory neurons of the nodosus ganglion.A, The histogram shows the number of neurons as a function of their capacitance (class width: 5 pF) in which a T-type current was present (black bars) or absent (white bars). Note that LVA currents were observed in most neurons with a capacitance above 20 pF; 108 cells were recorded to construct this histogram, and every cell had an HVA Ca2+current. B, Depolarizing steps (200 msec) to −15 mV and +30 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV yield a transient and a maintained current, respectively. C, Current–voltage relationship of the Ca2+ current. Note the quite distinct LVA and HVA components and that at −15 mV T-type current is recorded in isolation. A sum of two Boltzmann functions (I = G (V −E)/(1 + exp[ − (V −V1/2)/k]) was used to describe this I–V curve (fit obtained with no constraint; E = 71.4 mV;G = 4.6 and 20.8; k = 6.7 and 2.6 for the first and second Boltzmann function, respectively). Corresponding fits are shown as thin lines. Voltage for half activation (V1/2) of the T-type current was −32 mV and +9 mV for the HVA currents. Same cell as inB.

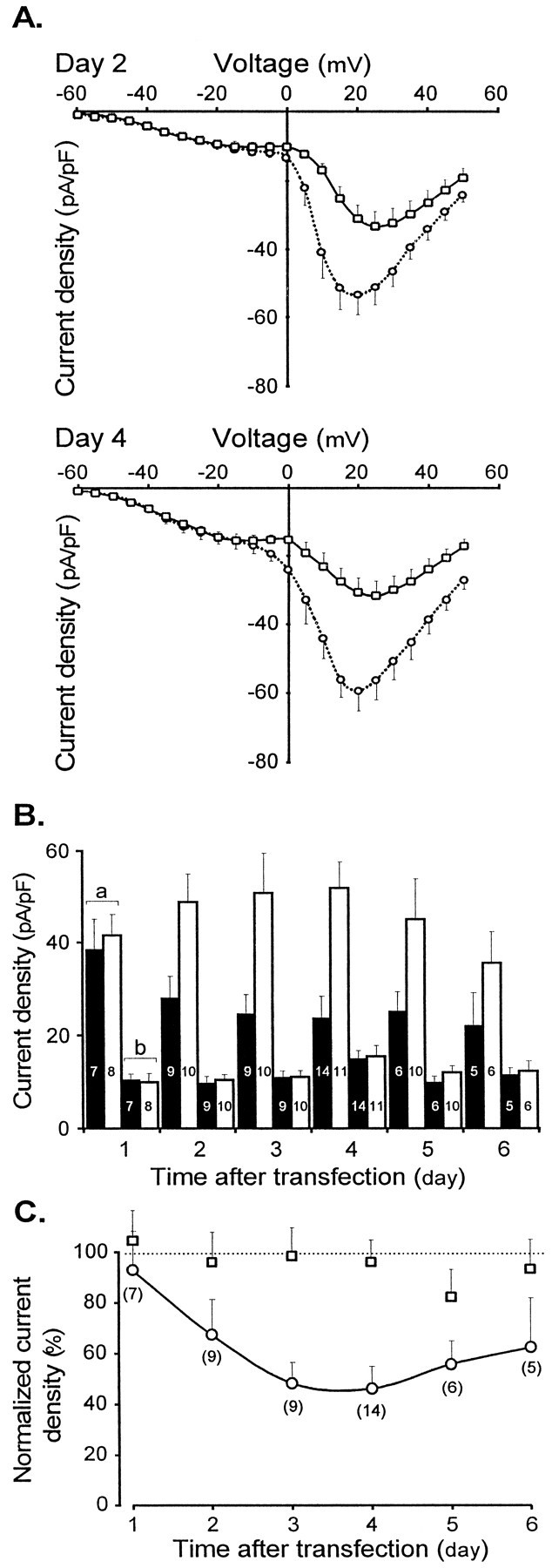

Fig. 4.

The generic anti-β antisense ON reduces the HVA current amplitude, with no effect on the T-type current.A, Mean I–V curves obtained 2 d (top) and 4 d (bottom) after transfection with the antisense ON (continuous line and squares, day 2,n = 9; day 4, n = 14) and a scrambled ON (dotted line and circles, day 2, n = 10; day 4, n = 11). Currents were evoked by 200 msec step depolarizations from a holding potential of −80 mV. Note that the current density of the T-type current remains constant in contrast to the reduction in density of the HVA current. B, Change of the T-type and HVA current density with time after transfection. Paired bars a and b refer to HVA and LVA mean current densities, respectively. Data obtained from antisense ON transfected neurons are averaged in black bars. Data obtained from scrambled ON transfected neurons are averaged in white bars. Numbers of cells are indicated inside each bar. Note that the current density of the T-type channels remains constant and that the HVA current is reduced in cells treated with an antisense ON as compared with cells treated with a scrambled ON. C, Curve representing the change with time after transfection of the normalized effect of the antisense ON on the LVA (square) and the HVA (circle) current densities. Mean % values were obtained by expressing for each experiment the current density of the anti-β antisense ON transfected cells as a percentage of the average current density of scrambled ON transfected cells from the same culture and recorded on the same day. This normalization eliminates differences introduced by culture-to-culture and transfection-to-transfection variabilities and by developmental modification of current density. Numbers of cells are indicated in brackets.

Immunocytochemical identification of β subunits present in nodosus ganglion neurons

As expected from neurons with a composite HVA Ca2+ current, the various α1A–Esubunits could be demonstrated immunocytologically, and all subtypes are present on the soma (Fig. 2); however, images obtained with the various specific β subunit antibodies were more contrasted. A very clear immunoreactivity indicative of a synthesis of β2 and β3subunits was observed, but only a faint labeling with the anti-β4 antibody and no reactivity for β1subunits were obtained. Interestingly, the α1E and β4 subunits are confined to small-diameter neurons, in which no T-type current has been recorded.

Fig. 2.

Immunocytochemical characterization of the Ca2+ channel subunits present in large sensory neurons. Using a battery of polyclonal antibodies, the presence of the various β1–4 (top row) and α1A, B, C, E (bottom row) subunits was examined at day 5 in culture. β2 and β3 subunits are the main β subunits present in this cell type, which contains no β1 subunits. Note that there is only a low density of β4 subunits, which are further restricted to small diameter cells, probably with no T-type current. All α1A, B, C, and E subunits are present in nodosus ganglion neurons. α1A is distributed equally on the soma and all along the neurites. α1B, which seems predominant, has a punctate distribution along the neurites. Interestingly, β2 gives the same punctate distribution as α1B. α1C is clearly restricted to the soma and main neurites. α1E is only weakly present and only in small neurons.

Efficiency of the anti-β antisense oligonucleotides to block synthesis of the β subunits in vitro

To test whether β subunits contribute to the definition of the T-type current properties using antisense ONs, we had to show that the antisense ONs could block the synthesis of all three β subunits that are detected in these cells by immunocytochemistry. In previous studies, an anti-β antisense ON has been shown to specifically affect Ca2+ currents in various neuronal types (Lambert et al., 1996) and to dramatically decrease the anti-β antibody staining of dorsal root ganglion neurons (Berrow et al., 1995); however, although the sequence of the anti-β antisense ON was optimized to hybridize with the mRNA of every β subunit subtype, some nucleotide mismatches are unavoidable (Fig.3B). Therefore, the ability of this ON to suppress the translation of various β subunit isoforms was tested in vitro. The obtained data demonstrate that the addition of RNase H to an in vitro transcription/translation of β1b, β2a, β3, and β4 has itself little effect on the synthesis of these various β subunits (Fig. 3C); however, the addition of the antisense ON almost totally abolishes the synthesis of all four β subunits. This inhibition was quantified by the binding of the various in vitro translation products to a protein corresponding to the AID, a region of the α1subunit that is essential for the β subunit anchoring (De Waard et al., 1995). The inhibition was of the order of 96 (β3) to 100% (β2), as determined by the reduction in AID sequence binding (data not shown). In contrast, an ON with the same composition but with a scrambled sequence (scrambled ON; see sequence in Materials and Methods) had little or no effect on the synthesis of full length β subunits able to bind the AID peptide. These results demonstrate that in spite of some sequence mismatches, the antisense ON efficiently represses the synthesis of several, and probably all, β subunits.

Blockade of synthesis of β subunits and characteristics of the Ca2+ currents

To test the effect of β subunit suppression on T-type current characteristics, nodosus ganglion neurons were transfected with anti-β antisense ON coupled with fluorescein. In every experiment, controls were neurons from the same batch of cultures that were transfected by the scrambled fluorescein-conjugated ONs. In this way, the effect of a nonspecific ON transfection on the membrane properties of the neurons was assessed. Transfected neurons were identified by their fluorescent nuclei.

As expected, a clear reduction of HVA Ca2+ currents was observed in anti-β antisense ON transfected neurons, and this effect increased with time. The I–V curves obtained by averaging current amplitude at each potential allow direct comparison of the current density in sensory cells transfected with either the antisense ON or the scrambled ON (Fig.4A). Typically, 2 d after transfection, the decrease in HVA current was already 35%. In sharp contrast, the LVA current density was unaffected. The lack of effect of the anti-β antisense ON on the T-type current can be assessed precisely by comparing the current density measured at −15 mV (where T-type current was recorded almost in isolation) in cells transfected with the antisense ON and with the scrambled ON. Similarly, the effect on the HVA current density can be quantified by comparing the current density measured at peak of the HVA current (after subtraction of the LVA component, which in every cell can be extrapolated at this voltage from the Boltzmann fit of theI–V curve). Such an analysis demonstrates clearly that the antisense ON specifically affected the HVA current density and that a maximal effect was reached between 3 and 4 d after transfection (Fig. 4B). The effect is statistically highly significant (for example, p < 0.001 at day 4; Student’s t test); however, the LVA current densities were identical in the two groups of cells during the 6 d after transfection (Fig. 4B).

Because expression experiments have suggested that β subunits could affect biophysical properties of Ca2+ channels, such as voltage dependence and activation/inactivation kinetics, without modifying Ca2+ current amplitude, we compared current characteristics in cells transfected with the anti-β antisense ON and the scrambled ON. As expected, the HVA currents displayed a significant shift of their voltage dependence toward more depolarized potentials. Three to four days after transfection, the voltage for half activation was 16.8 ± 1.3 mV (n= 25) in antisense ON transfected neurons and 8.9 ± 1.3 mV (n = 21; p < 0.0001 Student’st test) in control cells. The effect of the anti-β antisense ON on the HVA current characteristics was not investigated further because of the various effects expected from a composite HVA channel population; however, properties of the T-type current were studied in greater detail 3–4 d after transfection. When LVA currents recorded in anti-β antisense ON transfected neurons and scrambled ON transfected neurons were compared, neither the voltage-dependent activation (voltage for half activation was −29.2 ± 1.0 mV,n = 25, and −29.3 ± 1.6 mV, n = 20, respectively) nor the voltage-dependent inactivation (voltage for half inactivation was −44.5 ± 0.6 mV, n = 7, and −44.6 ± 1.2 mV, n = 8, respectively) were different (Fig. 5A). In addition, the activation/inactivation kinetics of the T-type current were not modified by the antisense treatment. The rise time of T-type current exponentially decreases according to the depolarizing potential in a similar way for the two cell populations (Fig. 5B). The decline has a mean e-fold change for 6.6 ± 0.4 mV (n = 14) in the anti-β antisense ON transfected neurons and 6.6 ± 0.3 mV (n = 17) in the scrambled ON transfected neurons. Similarly, the inactivation time constant can be evaluated by fitting a single exponential to the decay phase of the T-type current. The time constants obtained also decrease exponentially with the depolarizing potentials and are not affected by antisense treatment. The decline has a mean e-fold change for 9.1 ± 0.5 mV (n = 14) in the anti-β antisense ON transfected neurons and 9.0 ± 0.6 mV (n = 17) in the scrambled ON transfected neurons. Finally, the deactivation kinetics was estimated at −80 mV by fitting a double exponential to the tail current evoked by a 20 msec depolarizing step to −20 mV (Fig.5C). Both time constants were not sensitive to β suppression, with τ1 = 2.6 ± 0.4 msec, τ2 = 17.8 ± 1.6 msec (n = 10) in anti-β antisense ON transfected cells, and τ1 = 2.0 ± 0.2 msec, τ2 = 16.2 ± 1.9 msec (n = 10) in control cells. The complex deactivation kinetics is somewhat different from the monoexponential deactivation process described by Armstrong and Matteson (1985), which is in the range of tens of milliseconds (our slower component). One should remember, however, that in addition to the dominant voltage-dependent inactivation, we have already identified a small Ca-dependent component in the inactivation process of T-channels in nodosus cells (Bossu and Feltz, 1986): any absorbing inactivated state of the channel could lead to the more complex kinetics that we observed.

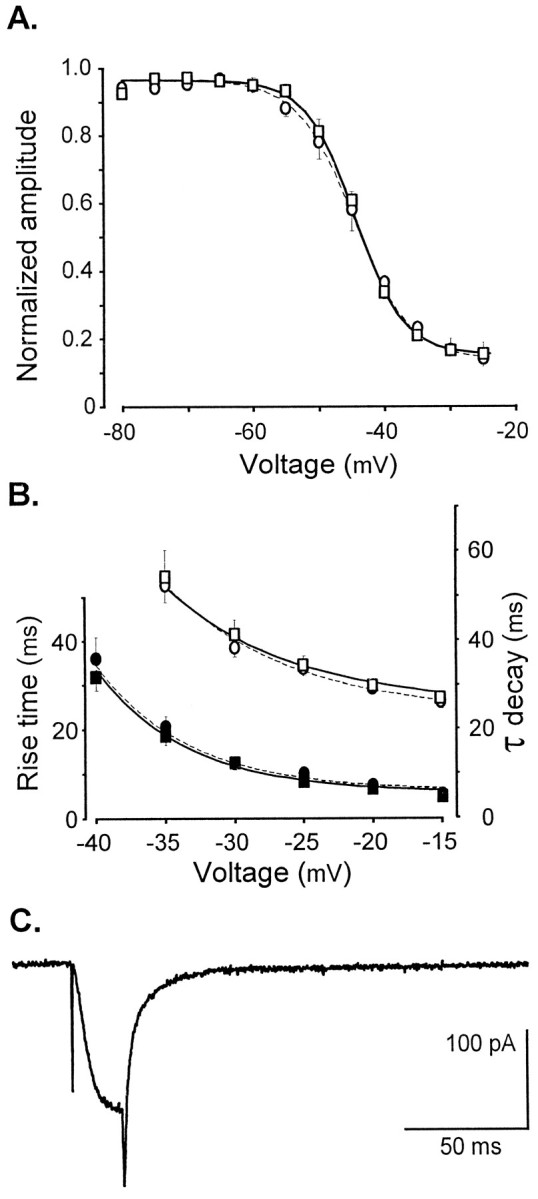

Fig. 5.

T-type current properties are not modified by β subunit suppression. A, The generic anti-β antisense ON does not alter T-type channel inactivation. A 300 msec depolarizing prepulse has an inhibitory effect on the amplitude of the current evoked by step depolarization to −15 mV. Normalized amplitude of the current is plotted as a function of the prepulse potential. Fit by a Boltzmann equation (Y = 1/(1 + exp[ − (V −V1/2)/k)]) yields a half inactivation potential (V1/2) of −44.5 ± 0.6 mV (n = 7) and −44.6 ± 1.2 mV (n = 8) for antisense (square) and scrambled (circle) ON-treated cells, respectively. B, The generic anti-β antisense ON does not alter T-type current kinetics. T-type current activation was estimated at each potential (range, −40 to −15 mV) by measuring the time necessary to observe an increase in current amplitude from 10 to 90% of its maximal value. Inactivation time constants were estimated using a monoexponential fit to describe the decaying phase in the voltage range in which the T-type current can be recorded in isolation. T-type currents were elicited by 200 msec step potentials from −80 mV holding potential. The activation rise time (black symbols) and inactivation time constants (empty symbols) are plotted as a function of the depolarizing step potentials (square, antisense ON transfected cells, n = 14; circle, scrambled ON transfected cells, n = 17). For each cell, the voltage dependence of values was described by a decreasing exponential, and the resulting mean exponentials are also plotted in the graphs. The solid and dotted linesrefer to values obtained on antisense or scrambled ON-treated cells, respectively. C, A 30 msec step depolarization from −80 to −20 mV generates a tail current reflecting the deactivation kinetics of the T-type channels in control conditions. Such tail currents can be fitted by two exponentials. The present trace is the average of five recordings performed successively in the same neuron.

In conclusion, because blocking β synthesis in rat nodosus ganglion neurons neither modifies the T-type current density nor affects any other of its biophysical properties, we conclude that this ancillary subunit does not contribute to the definition of the T-type current characteristics in this cell type.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, a subtractive approach, based on an antisense strategy, was used to determine whether T-type channels and HVA channels possess similar auxiliary β subunits. The study was performed on nodosus ganglion neurons, which express both low and high voltage-activated currents. The modifications in HVA current properties were used to attest the blockade of β subunit synthesis in the recorded neurons. We show that suppression of the synthesis of β subunits present in cranial sensory neurons (mainly β2and β3) induced a marked decrease in the HVA current amplitude and a change in its properties, as expected from previous results obtained in other cell types (Berrow et al., 1995;Lambert et al., 1996). In contrast, in the same neurons, depletion in β subunits does not modify in any way the T-type current.

The absence of effect of the anti-β antisense ON on the T-type current can be interpreted in different ways. First, it can be hypothesized that the synthesis of the β subunit specific to the T-type channel is not blocked by the anti-β antisense ON; however,in vitro transcription/translation experiments showed that the common anti-β antisense ON is equally efficient in blocking the transcription of each of the four cloned β subunit genes, which strongly suggests that this ON acts similarly in situ. Although unlikely, it could still be assumed that the putative T-type β subunit has not already been cloned and is very different from the four other β genes, even in the two strongly conserved domains.

Second, the cells may contain some residual β gene products, attributable either to a large store of β proteins already synthesized at the time of transfection, or to a partial blockade of this protein synthesis. Consequently, any effect of the anti-β antisense ON would be masked. In this case, however, no modification of the HVA Ca2+ currents should be observed. To explain that T-type channels are less sensitive to partial depletion of the β subunits than HVA channels, it would have to be assumed that the LVA channels have a much higher affinity for β subunits than the HVA channels do.

Another possible explanation is that the turnover of the putative β subunit constitutive of the T-type channels is lower than the turnover of HVA Ca2+ channels β subunits (at ∼4 d) (see Fig. 4B) (Berrow et al., 1995; Lambert et al., 1996) and that at the various times examined after transfection, the LVA channels still possess their β subunits. The life span of nodosus ganglion neurons in culture, and the possible intracellular degradation of the ONs, did not allow us to test the effect of the antisense ON more than 6 d after transfection; however, T-type current densities remained almost constant throughout the culture period. Because these neurons developed neurites and showed an increase in mean capacitance, they must have synthesized new T-type channels during this period. These channels should have been devoid of any β subunits after the antisense ON treatment and therefore might have displayed modified activities.

The lack of effect of the antisense ON on T-type current properties does not rule out the possibility that the LVA channels do possess a β subunit that does not modulate the activity of the pore-forming subunit; however, the expression of all α1 channels has always demonstrated a modulatory effect of this ancillary subunit. Current amplitude stimulation by β subunits has been observed for almost all α1 subunits (for review, see De Waard et al.,1996). For example, in Xenopus laevis oocytes, coexpression of β1b with α1A (De Waard et al., 1994), α1B (Stea et al., 1993), or α1E(Wakamori et al., 1994) subunit induces a multiplication of the peak current by 18, 4, or 3, respectively. In addition, coexpression of the different β subunits with the α1C (Wei et al., 1991;Hullin et al., 1992; Perez-Reyes et al., 1992; Castellano et al., 1993a,b) or α1A (Mori et al., 1991; De Waard et al., 1995) subunit increases the current between 2- and 19-fold. It also seems that β subunits systematically modify the biophysical properties of α1 subunits. In each case, the auxiliary subunit induces a shift in the current I–Vrelationship toward more hyperpolarized potentials (for review, see De Waard et al., 1996). This systematic effect explains why for the composite HVA currents of nodosus ganglion neurons we observed a difference of ∼8 mV between the voltage for half activation of the composite currents, measured in cells transfected with the scrambled ONs and the anti-β antisense ON. Following this line of thought, the shift in the I–V relationship observed in our study suggests that the remaining HVA currents are attributable to channels devoid of β subunits. Concerning inactivation, several studies show that β subunits also shift the inactivation curve of the current toward more hyperpolarized potentials. These auxiliary subunits systematically modify the inactivation kinetics of the current, although with a variable effect, according to the β and α1 subunits studied. In addition, in several cases they also modify the activation kinetics of the current (for review, see De Waard et al., 1996). Therefore, the hypothesis that T-type channels have a β subunit that does not modify their current properties would imply quite significant structural differences between their pore-forming subunit and the other α1 subunits. It would also mean that the pore-forming subunit of T-type channels is not one of the classical α1 subunits (S, A, B, C, D, or E).

Finally, to explain our results, we can postulate that β subunits are not a constitutive subunit of the T-type channels in nodosus ganglion neurons. This argues against the possibility that the pore-forming subunit of the T-type channels has already been cloned, because expression and in vitro experiments suggest that every cloned α1 subunit binds a β subunit with concomitant modifications of the current properties. The only α1 gene coding for Ca2+ channels with properties reasonably close to those of the T-type currents known so far is the α1E channel (Soong et al., 1993; Bourinet et al., 1996). Interestingly, in some cases, β subunit association to α1E was without effect on current amplitude (Soong et al., 1993); however, β subunits were still able to shift activation and inactivation voltage dependence. If no β subunit participates in the definition of the LVA current properties, as is the case in nodosus ganglion neurons, the α1E subunit per se should account for the observed properties of this current. There are some irreconcilable differences, mainly in the inactivation and deactivation kinetics, which are both much slower for the T-type current than for an expressed α1E current, and in the elementary conductance of the channels (Ellinor et al., 1993; Soong et al., 1993; Zhang et al., 1993; Schneider et al., 1994; Williams et al., 1994; Bourinet et al., 1996). As such, it is noteworthy that α1E subunits are demonstrated in the present study in nodosus ganglion neurons, which probably do not express a T-type current. In other cell types, however, a number of LVA currents have been described with variable properties (Huguenard, 1996). T-type currents vary by up to 10-fold in their recovery time in steady-state inactivation and by up to 20 mV in their activation and inactivation ranges, and their sensitivity to Ni2+ varies with IC50 values from 40 up to 770 μm. Therefore, it is possible that T-type currents are attributable to distinct channels in different cell types, some of which may result from an α1Eβ combination.

In conclusion, our results show that in nodosus ganglion neurons a classical β subunit is not necessary to maintain the function of T-type channels. This hypothesis is consistent with the recent observation that a knock-out of the β1 subunit normally present in skeletal muscle leaves the T-type current recorded in this cell type intact (Strube et al., 1996). The results also strongly indicate that if there are any β subunits associated with T-type channels, and this is questionable, their interaction must be fundamentally different from other types of Ca2+channels.

Footnotes

R. C. Lambert was the recipient of an Eli Lilly postdoctoral fellowship, and J. Mouton was funded by an MESR predoctoral fellowship. We thank Drs B. Demeneix and J. P. Behr who helped us in the development of the PEI technique and without whom this work could not have been performed.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Anne Feltz, Laboratoire de Neurobiologie Cellulaire, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 5 rue Blaise Pascal, 67084 Strasbourg, France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almers W, McCleskey EW. Non-selective conductance in calcium channels of frog muscle: calcium selectivity in a single-file pore. J Physiol (Lond) 1984;353:585–608. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong CM, Matteson DR. Two distinct populations of calcium channels in a clonal line of pituitary cells. Science. 1985;227:65–67. doi: 10.1126/science.2578071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong CM, Neyton J. Ion permeation through calcium channels. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1992;635:18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb36477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berrow NS, Campbell V, Fitzgerald EM, Brickley K, Dolphin A. Antisense depletion of β-subunit modulates the biophysical and pharmacological properties of neuronal calcium channels. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;482:481–491. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bossu JL, Feltz A. Inactivation of the low-threshold transient calcium current in rat sensory neurones: evidence for dual process. J Physiol (Lond) 1986;376:341–357. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bossu JL, Feltz A, Thomann JM. Depolarization elicits two distinct calcium currents in vertebrate sensory neurones. Pflügers Arch. 1985;403:360–368. doi: 10.1007/BF00589247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourinet E, Zamponi GW, Stea A, Lewis BA, Jones LP, Yue DT, Snutch TP. The α1E calcium channel exhibits permeation properties similar to the low-voltage-activated calcium channels. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4983–4993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-04983.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brust PF, Simerson S, McCue AF, Deal CR, Schoonmaker S, Williams ME, Velicelebi G, Johnson EC, Harpold MM, Ellis SB. Human neuronal voltage-dependent calcium channels: studies on subunit structure and role in channel assembly. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1089–1102. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90004-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carbone E, Lux HD. A low voltage-activated, fully inactivating Ca channel in vertebrate sensory neurones. Nature. 1984;310:501–502. doi: 10.1038/310501a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbone E, Lux HD. Kinetics and selectivity of a low-voltage-activated calcium current in chick and rat sensory neurones. J Physiol (Lond) 1987;386:547–570. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carbone E, Morad M, Lux HD. External Ni2+ selectively blocks the low-threshold Ca2+ current of chick sensory neurons. Pflügers Arch. 1987;408:R60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castellano A, Wei X, Birnbaumer L, Perez-Reyes E. Cloning and expression of a neuronal calcium channel β subunit. J Biol Chem. 1993a;268:12359–12366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castellano A, Wei X, Birnbaumer L, Perez-Reyes E. Cloning and expression of a third calcium channel β subunit. J Biol Chem. 1993b;268:3450–3455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Waard M, Campbell KP. Subunit regulation of the neuronal α1A Ca2+ channel expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;485:619–634. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Waard DR, Pragnell, Campbell KP. Ca2 channel regulation by a conserved β subunit domain. Neuron. 1994;13:495–503. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Waard M, Witcher DR, Pragnell M, Liu H, Campbell KP. Properties of the α1-β anchoring site in voltage dependent Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12056–12064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Waard M, Gurnett CA, Campbell KP. Structural and functional diversity of voltage-activated calcium channels. In: Naharashi T, editor. Ionic channels, Vol 4. Plenum; New York: 1996. pp. 41–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellinor PT, Zhang JF, Randall AD, Zhou M, Schwarz TL, Tsien RW, Horne WA. Functional expression of a rapidly inactivating neuronal calcium channel. Nature. 1993;363:455–458. doi: 10.1038/363455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurnett CA, De Waard M, Campbell KP. Dual function of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel α2δ subunit in current stimulation and subunit interaction. Neuron. 1996;16:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hess P, Tsien RW. Mechanism of ion permeation through calcium channels. Nature. 1984;309:453–456. doi: 10.1038/309453a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess P, Lansman JB, Tsien RW. Calcium channel selectivity for divalent and monovalent cations. J Gen Physiol. 1986;88:293–319. doi: 10.1085/jgp.88.3.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huguenard JR. Low-threshold calcium currents in central nervous system neurons. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:329–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.001553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hullin R, Singer-Lahat D, Freichel M, Biel M, Dascal N, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V. Calcium channel β subunit heterogeneity: functional expression of cloned cDNA from heart, aorta and brain. EMBO J. 1992;11:885–890. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kostyuk PG, Mironov SL, Shuba YM. Two ion-selecting filters in the calcium channels of the somatic membrane of mollusc neurones. J Membr Biol. 1983;76:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambert RC, Maulet Y, Dupont JL, Mykita S, Craig P, Volsen S, Feltz A. Polyethylenimine-mediated DNA transfection of peripheral and central neurons in primary culture: probing Ca2+ channel structure and function with antisense oligonucleotides. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;7:239–246. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lux HD, Carbone E, Zucker H. Na+ currents through low-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels of chick sensory neurones: block by external Ca2+ and Mg2+. J Physiol (Lond) 1990;430:159–188. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikami A, Imoto K, Tanabe T, Niidome T, Mori Y, Takeshima H, Narumiya S, Numa S. Primary structure and functional expression of the cardiac dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel. Nature. 1989;340:230–233. doi: 10.1038/340230a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mintz IM, Adams ME, Bean BP. P-type calcium channels in rat central and peripheral neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mori Y, Friedrich T, Kim MS, Mikami A, Nakai J, Ruth P, Bosse E, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Furuichi T, Mikoshiba K, Imoto K, Tanabe T, Numa S. Primary structure and functional expression from complementary DNA of a brain calcium channel. Nature. 1991;350:398–402. doi: 10.1038/350398a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nowycky MB, Fox AP, Tsien RW. Three types of neuronal calcium channel with different calcium agonist sensitivity. Nature. 1985;316:440–446. doi: 10.1038/316440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez-Reyes E, Schneider T. Calcium channels: structure, function, and classification. Drug Dev Res. 1994;33:295–318. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez-Reyes E, Castellano A, Kim HS, Bertrand P, Baggstrom E, Lacerda AE, Wei X, Birnaumer L. Cloning and expression of a cardiac/brain β subunit of the L-type calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1792–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pragnell M, Sakamoto J, Jay SD, Campbell KP. Cloning and tissue-specific expression of the brain calcium channel β-subunit. Fed Eur Biochem Soc. 1991;2:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81296-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider T, Wei X, Olcese R, Costantin JL, Neely A, Palade P, Perez-Reyes E, Qin N, Zhou J, Crawford GD, Smith RG, Appel SH, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Molecular analysis and functional expression of the human type E neuronal Ca2+ channel α1 subunit. Receptors Channels. 1994;2:255–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shistik E, Ivanina T, Hosey MM, Dascal N. Ca2+ current enhancement by α2/δ and β subunits in Xenopus oocytes: contribution of changes in channel gating and α1 protein level. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;489:55–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soong TW, Stea A, Hodson CD, Dubel SJ, Vincent SR, Snutch TP. Structure and functional expression of a member of the low voltage-activated calcium channel family. Science. 1993;260:1133–1135. doi: 10.1126/science.8388125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stea A, Dubel SJ, Pragnell M, Leonard J, Campbell KP, Snutch TP. A β subunit normalizes the electrophysiological properties of a cloned N-type Ca2+ channel α1-subunit. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1103–1116. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strube C, Beurg M, Powers PA, Gregg RG, Coronado R. Reduced Ca2+ current, charge movement, and absence of Ca2+ transient in skeletal muscle deficient in dihydropyridine receptor β1 subunit. Biophys J. 1996;71:2531–2543. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79446-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takashi M, Seagar MJ, Jones JF, Reber BFX, Catterall WA. Subunit structure of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels from skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5478–5482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomlinson WJ, Stea A, Bourinet E, Charnet P, Nargeot J, Snutch TP. Functional properties of a neuronal class C L-type calcium channel. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1117–1126. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90006-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Volsen SG, Day NC, McCormack AL, Smith W, Craig PJ, Beattie R, Ince PG, Shaw PJ, Ellis SB, Gillespie A, Harpold MM, Lodge D. The expression of neuronal voltage-dependent calcium channels in human cerebellum. Mol Brain Res. 1995;34:271–282. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00234-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volsen SG, Day NC, McCormack AL, Smith W, Craig PJ, Beattie RF, Smith D, Ince PG, Shaw P, Ellis SB, Mayne N, Burnett JP, Gillespie A, Harpold MM. The expression of voltage dependent calcium channel β subunits in human cerebellum. Neuroscience. 1997;80:161–174. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wakamori M, Niidome T, Furutama D, Furuichi T, Mokoshiba K, Fujita Y, Tanaka I, Katayama K, Yatani A, Schwartz A, Mori Y. Distinctive functional properties of the neuronal BII (class E) calcium channel. Receptors Channels. 1994;2:303–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei X, Perez-Reyes E, Lacerda AE, Schuster G, Brown AM, Birnbaumer L. Heterologous regulation of the cardiac Ca2+ channel α1 subunit by skeletal muscle β and γ subunits. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21943–21947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei X, Pan S, Lang W, Kim H, Schneider T, Perez-Reyes E, Birnbaumer L. Molecular determinants of cardiac channel pharmacology. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27106–27111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams ME, Marubio LM, Deal CR, Hans M, Brust PF, Philipson LH, Miller RJ, Johnson EC, Harpold MM, Ellis SB. Structure and functional characterization of neuronal α1E calcium channel subtypes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22347–22357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Witcher DR, De Waard M, Sakamoto J, Franzini-Armstrong C, Pragnell M, Kahl SD, Campbell KP. Subunit identification and reconstitution of the N-type Ca2+ channel complex purified from brain. Science. 1993;261:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.8392754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yue DT, Marban E. Permeation in the dihydropyridine-densitive calcium channel. Multi-ion occupancy but no anomalous mole-fraction effect between Ba2+ and Ca2+. J Gen Physiol. 1990;95:911–940. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.5.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang JF, Randall AD, Ellinor PT, Horne WA, Sather WA, Tanabe T, Schwarz TL, Tsien RW. Distinctive pharmacology and kinetics of cloned neuronal Ca2+ channels and their possible counterparts in mammalian CNS neurons. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1075–1088. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90003-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]