Abstract

The shaking-B2 mutation was used to analyze synapses between haltere afferents and a flight motoneuron in adult Drosophila. We show that the electrical synapses among many neurons in the flight circuit are disrupted inshaking-B2 flies, suggesting thatshaking-B expression is required for electrical synapses throughout the nervous system. In wild-type flies haltere afferents are dye-coupled to the first basalar motoneuron, and stimulation of these afferents evokes electromyograms from the first basalar muscle with short latencies. In shaking-B2 flies dye coupling between haltere afferents and the motoneuron is abolished, and afferent stimulation evokes electromyograms at abnormally long latencies. Intracellular recordings from the motoneuron confirm that the site of the defect in shaking-B2 flies is at the synapses between haltere afferents and the flight motoneuron. The nicotinic cholinergic antagonist mecamylamine blocks the haltere-to-flight motoneuron synapses inshaking-B2 flies but does not block those synapses in wild-type flies. Together, these results show that the haltere-to-flight motoneuron synapses comprise an electrical component that requires shaking-B and a chemical component that is likely to be cholinergic.

Keywords: gap junctions, Drosophila, shaking-B, Passover, synapse, flight

Genetic and molecular analyses in both the mouse and the fly have identified a host of molecules that function in the assembly and operation of synapses. An understanding of mechanisms by which these molecules act requires preparations in which molecular genetic techniques can be combined with electrophysiological techniques for monitoring synaptic transmission. Although Drosophilaprovides powerful molecular and genetic tools, presently only two sets of synapses in Drosophila have been investigated by using combined genetic and physiological approaches: the larval/embryonic neuromuscular junction (for review, see Keshishian et al., 1996) and the adult giant fiber circuit (for review, see Thomas and Wyman, 1983). Differences undoubtedly exist between the neuromuscular junction and central synapses, and the central synapses comprising the giant fiber circuit are presently the only identified central synapses inDrosophila (see Wyman et al., 1984). One goal of our study is to identify other central synapses in adult Drosophilathat are amenable to both molecular genetic and physiological techniques.

In this study we characterize the synapses between haltere afferents and a flight motoneuron in adult Drosophila. Halteres are reduced metathoracic wings containing ∼200 sensory neurons that monitor haltere movements and convey this information to central neurons coordinating flight (Pflugstaedt, 1912; Pringle, 1948; Cole and Palka, 1982; Heide, 1983; Chan and Dickinson, 1996; Fayyazuddin and Dickinson, 1996). In the large fly, Calliphora vicina, both electrical and chemical synapses exist between haltere afferents and a flight motoneuron (Fayyazuddin and Dickinson, 1996). Previously,shaking-B mutations were shown to disrupt electrical synapses in the giant fiber circuit (Thomas and Wyman, 1984; Baird et al., 1990, 1993; Krishnan et al., 1993; Phelan et al., 1996; Sun and Wyman, 1996); we demonstrate in Drosophila that the mutationshaking-B2 eliminates the electrical synapses between haltere afferents and a flight motoneuron. Our results indicate that electrical synapses among many neurons are disrupted inshaking-B2 flies, and shaking-Bexpression probably is required throughout the nervous system for the establishment of most, if not all, electrical synapses. In addition, we show pharmacologically that the chemical synapses persisting inshaking-B2 flies are likely to be cholinergic. Together, these results show that the haltere-to-flight motoneuron synapses in Drosophila are composed of an electrical component that requires shaking-B and a chemical component. These central synapses are amenable to both genetic and neurophysiological techniques and, therefore, will facilitate investigations into molecular mechanisms underlying the assembly and operation of central synapses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Stocks

The shaking-B2 (also known asshaking-B(neural)) and Passovermutant stocks were obtained from the laboratory of Robert J. Wyman (Yale University, New Haven, CT). These mutations behave as viable genetic nulls, and although we show only the data forshaking-B2, Passover yielded similar results (Krishnan et al., 1993; Crompton et al., 1995). Canton-Special (Canton-S) flies were used as wild-type controls. Oregon-R flies, another wild-type control stock, yielded results similar to Canton-S flies.

Anatomy

Staining haltere afferents and dye-coupled neurons.Flies were anesthetized lightly, using ether, and were waxed ventral-side up to the bottom of a small Petri dish. The haltere was waxed by its capitellum in an outstretched position. A glass capillary pulled to an electrical resistance of 3∼2 MΩ when filled with 2% neurobiotin (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) in saline was pushed into the haltere at the junction between the scabellum and pedicellus. A silver/silver chloride wire placed in the abdomen served as a ground. Neurobiotin was iontophoresed from the capillary by using 20 μsec, 30 nA stimuli delivered at 1 Hz for 6 min. Flies were incubated in a moist chamber for 10 min at room temperature.

After incubation, flies were partially dissected, exposing the thoracic ganglia, and fixed overnight at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde in 1.0 m PBS. Thoracic ganglia were removed and stored in 1.0 m PBS at 5°C for 1–3 d, after which preparations were rinsed and incubated for 1.5 hr in 0.4% Triton X-100–PBS. Ganglia were rinsed in PBS and incubated overnight in 2% ABC (Vector Labs) in PBS. After being rinsed in PBS, preparations were incubated in chromogen 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (0.33 mg/ml PBS), activated with H2O2 (5 l of 0.3%/ml PBS), and intensified with NiCl2 (5 l of 8%/ml PBS). Ganglia were rinsed in PBS, dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series, cleared in methyl salicylate, and mounted in Canada balsam. Preparations were viewed with a Nikon Optiphoto-2 compound microscope. Photographs were taken with Kodak Ektachrome slide film, and slides were scanned with a Polaroid SprintScan35 and Macintosh Power PC running Adobe Photoshop 3.0 software. Photo montages were created in Adobe Photoshop.

Staining B1mn and dye-coupled neurons. A technique similar to that used by Trimarchi and Schneiderman (1994) was used to retrogradely stain the motoneuron (B1mn), innervating the first basalar muscle (B1). Briefly, flies were anesthetized lightly, using ether, and were waxed to the bottom of a small Petri dish. An etched tungsten wire was used to punch a small hole in the cuticle at the point of insertion of B1, and a neurobiotin-coated tungsten wire was used to apply crystals to the underlying muscle. Flies were incubated in a moist chamber for 10 min at room temperature. Ganglia were processed for B1mn staining in a manner identical to that used for haltere afferents described above.

Physiology

Electromyograms from B1. Flies were anesthetized lightly, using ice, and were waxed to the bottom of a small Petri dish. The haltere was waxed by its capitellum in an outstretched position. When the fly was flooded with saline, an air bubble was trapped around the fly, maintaining its viability. The composition of the saline was (in mm): 115 NaCl, 5 KCl, 6 CaCl2·2H2O, 1 MgCl2·6H2O, 4 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4·1H2O, 5 trehalose, 75 sucrose, and 5 N-Tris (hydroxymethyl) methyl-2-aminoethane sulfonic acid (modified from Koenig and Ikeda, 1983; Singleton and Woodruff, 1994). When drugs were applied, the pro- and mesothoracic pre-episternum were removed, exposing the fused thoracic ganglia to saline and mecamylamine (0.5 mm) for 15 min before data were gathered; otherwise, only the abdomen was opened, forming a saline bridge to the electrical ground. A silver/silver chloride wire in the saline served as a ground. Stimulation of haltere afferents was accomplished via a glass capillary filled with saline (electrical resistance of 2 MΩ) positioned at the junction between the scabellum and pedicellus. The air bubble surrounding the fly allowed electrical isolation of the stimulating electrode from the silver/silver chloride wire, grounding the saline bathing the fly. Because of the resistance between the stimulating electrode and ground electrode (∼20 MΩ) and the capacitance of the stimulating electrode, there was a significant voltage drop (>50%) across the electrode tip. Thus, the stimuli haltere sensory neurons underwent are linearly related to, but considerably less than, those mentioned in the text, figures, and figure legends. Haltere afferents were stimulated with 20 μsec stimuli at 1 Hz by using a personal computer running pCLAMP software, a DMA interface board (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), and a Grass S44 stimulator (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA). Using an etched tungsten wire, we punched a small hole in the cuticle at the insertion site of B1. A recording glass electrode pulled to an electrical resistance of ∼2 MΩ was inserted into the muscle. Signals were amplified with a Getting microelectrode amplifier (model 5A, Getting Instruments, Iowa City, IA) and stored on a personal computer with pCLAMP software and a DMA interface board. In a manner similar to that used for analysis of synapses in the giant fiber circuit, we measured B1 electromyogram (EMG) response latencies from the onset of the stimulus to the onset of the evoked EMG in the muscle (Tanouye and Wyman, 1980). All analysis was done with pCLAMP, Excel 4.0 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), and SigmaPlot (Jandel Scientific, Corte Madera, CA) software.

Intracellular recordings from B1mn. The methodology of Ikeda and Kaplan (1974) was modified to develop a preparation that allows reliable intracellular recording and staining of neurons in the adult thoracic ganglia of Drosophila. Flies were anesthetized lightly, using ice, and were waxed ventral-side up to the bottom of a small Petri dish. The haltere was waxed by its capitellum in an outstretched position. The proboscis, pro-, and mesothoracic pre-episternum were removed, exposing the fused thoracic ganglia. The neurolemma was treated with 1% Pronase E (Type XIV, Sigma) for 8–12 sec. The preparation was visualized with a Wild Kombistereo microscope with a 10×/0.2 objective and 20× eyepieces. To stabilize the ganglia, we positioned an Insulex-coated spoon under it. Stimulation of haltere afferents was accomplished in a manner identical to that used for evoking EMGs (see Electromyograms from B1).

Intracellular recordings from B1mn were obtained with an aluminosilicate glass microelectrode, the tip of which was filled with 2% neurobiotin in 3 m KCl. KCl (3 m) was used to fill the rest of the electrode, resulting in electrical resistances of 150–250 MΩ. Signals were amplified with a Getting microelectrode amplifier (model 5A) and stored on a personal computer with pCLAMP software and a DMA interface board. To confirm the identity of the impaled neuron, we injected neurobiotin, using positive biased sinusoidal (0.8 Hz) current of 1.0 nA for 2–10 min. Ganglia were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for staining in a manner identical to that used for haltere afferents described above. Using the contour of the ganglia and nerves as landmarks, we could impale B1mn reliably in approximately one of seven preparations (21 of 165 attempts in wild type; 4 of 26 attempts inshaking-B2). When B1mn was not impaled often (63 of 165 attempts in wild type; 17 of 26 attempts inshaking-B2), adjacent flight and leg motoneurons were impaled, including dorsal longitudinal motoneurons (Coggshall, 1978; Ikeda and Koenig, 1988), other steering motoneurons (Trimarchi and Schneiderman, 1994), the tergotrochanteral motoneuron (TTMn; Baird et al., 1993), and the fast extensor tibiae motoneuron (FETi; TLMn inTrimarchi and Schneiderman, 1993).

RESULTS

Dye coupling reveals B1mn is a postsynaptic target of haltere afferents

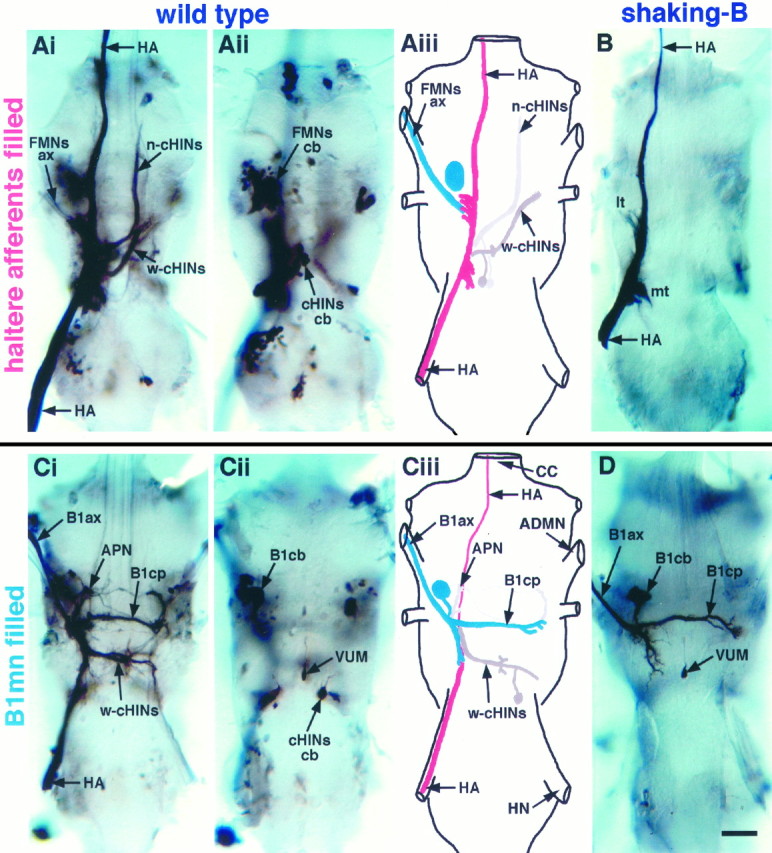

Neurobiotin injected into the haltere was transported anterogradely by haltere afferents to their axon terminals in the CNS, where the dye passed trans-synaptically from afferents to a variety of motoneurons and interneurons (Fig. 1A, Tables 1, 2). Haltere afferents (HA) project into the thoracic ganglia through the haltere nerve, extend through the dorsal region, and project to the brain through the cervical connective (Fig. 1A,B; Ghysen, 1978; Palka et al., 1979; Chan and Dickinson, 1996). We have summarized the prominent neurons dye-coupled to haltere afferents in Figure1Aiii. These dye-coupled neurons include contralaterally projecting haltere interneurons (cHINs, described below and in Strausfeld and Seyan, 1985) and flight motoneurons (FMNs). The morphology of one of the dye-coupled motoneurons is consistent with that of the ipsilateral motoneuron (B1mn) innervating the first basalar muscle (B1). The B1mn is characterized by having a large axon (B1ax) that projects through the anterior dorsal mesothoracic nerve (ADMN) and a large, ventrally located cell body (B1cb; Fig. 1D;Trimarchi and Schneiderman, 1994). In 95% of the preparations haltere afferents were dye-coupled to a motoneuron with a large axon (FMNsax) in the ADMN and a large ventrally located cell body (FMNscb; Fig.1A, Tables 1, 2). In addition, B1mn has a prominent neurite that extends contralaterally through the mesothoracic decussation (B1cp; Fig. 1D; Trimarchi and Schneiderman, 1994). In 25% of the preparations a faintly stained neurite was observed that projects contralaterally through the mesothoracic decussation in a manner similar to that of B1mn.

Table 1.

Occurrence of neurons dye-coupled to haltere afferents

| Blmn (%) | n-cHINs (%) | w-cHINs (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 95 (19/20)1-a | 100 (20/20) | 100 (20/20) |

| shaking-B | 0 (0/13) | 0 (0/13) | 0 (1/13) |

Percentage of ganglia that exhibited trans-synaptic dye coupling from haltere afferents. Shown in parentheses is the number of ganglia that exhibited dye-coupling per number of ganglia stained.

Table 2.

Occurrence of neurons dye-coupled to B1mn

| Haltere afferents (%) | w-cHINs (%) | APNs (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 94 (15/16)2-a | 100 (16/16) | 63 (10/16) |

| shaking-B | 0 (0/10) | 0 (0/10) | 0 (0/10) |

Percentage of ganglia that exhibited trans-synaptic dye coupling from B1mn. Shown in parentheses is the number of ganglia that exhibited dye-coupling per number of ganglia stained.

Fig. 1.

Dye coupling is eliminated inshaking-B2 flies. A, Anterograde staining of haltere afferents in a wild-type fly. Shown is a montage of dorsal projections (Ai) and ventral cell bodies (Aii). Aiii, Schematic derived from Ai and Aii illustrating the prominent neurons dye-coupled to haltere afferents (see Tables 1, 2 for frequency of occurrence). Nerve trunks are labeled inCiii. Stained haltere afferents (HA;red) are visible in the haltere nerve and extend through the dorsal region of the ganglia before exiting through the cervical connective. Dye passes from haltere afferents to flight motoneurons identified by staining of axons (FMNs ax;blue) in the ADMN and large ventral cell bodies (FMNs cb; blue). Dye also passes to several large interneurons [neck (n-cHINs) and wing contralaterally projecting haltere interneurons (w-cHINs; gray)] with cell bodies (cHINs cb; gray) located in the ventroposterior rind of the mesothoracic leg neuromere.B, Anterograde staining of haltere afferents in ashaking-B2 fly. Dye did not pass from haltere afferents to any other neurons. Stained haltere afferents (HA) are visible in haltere nerve and extend through the dorsal region of the ganglia, forming a medial tuft (mt) and lateral tuft (lt) of arbors before exiting through the cervical connective. C, Retrograde staining of the B1mn in a wild-type fly. Shown is a montage of dorsal projections (Ci) and ventral cell bodies (Cii).Ciii, Schematic derived from Ci andCii illustrating the prominent neurons dye-coupled to B1mn (see Tables 1, 2 for frequency of occurrence). The B1mn axon (B1ax; blue) is visible in the ADMN, and the contralateral process (B1cp; blue) crosses the midline through the mesothoracic decussation. B1mn has a large ventrally located cell body (B1cb). Dye passes from B1mn (blue) to haltere afferents (HA; red). Neurobiotin appears to travel preferentially in the retrograde direction; thus haltere afferent projections that extend anteriorly through the cervical connective were stained only faintly. Dye also passed to several interneurons (w-cHINs; gray) with cell bodies (cHINs cb; gray) located in the ventroposterior rind of the mesothoracic leg neuromere. Note that the w-cHINs dye-coupled to B1mn appear to be contralateral homologs of those coupled to haltere afferents. Several anteriorly projecting neurons (APNs;gray) also were dye-coupled to B1mn. D, Retrograde staining of B1mn in a shaking-B2fly. Dye did not pass from B1mn to any other neurons. The B1mn axon (B1ax) is visible in the ADMN, and the contralateral process (B1cp) crosses the midline through the mesothoracic decussation. The ventral unpaired median cell (VUM) that also innervates B1 is visible inCii and D. Scale bar, 20 μm.

We confirmed that B1mn is a postsynaptic target of haltere afferents by observing dye coupling in the opposite direction, from B1mn to haltere afferents (Fig. 1C, Tables 1, 2). In 95% of the preparations neurobiotin introduced into B1mn by retrograde filling from the B1 muscle passed trans-synaptically from B1mn to haltere afferents (HA; Fig. 1C, Tables 1, 2). Neurobiotin introduced into B1mn by an alternate method, direct intracellular injection, also passed trans-synaptically to haltere afferents (for example, see below Fig. 4Aii). Twenty-one B1mns successfully were injected intracellularly with neurobiotin, 18 of which passed dye to haltere afferents. Regardless of the method used to introduce neurobiotin into B1mn, the dye routinely passed trans-synaptically to haltere afferents.

Fig. 4.

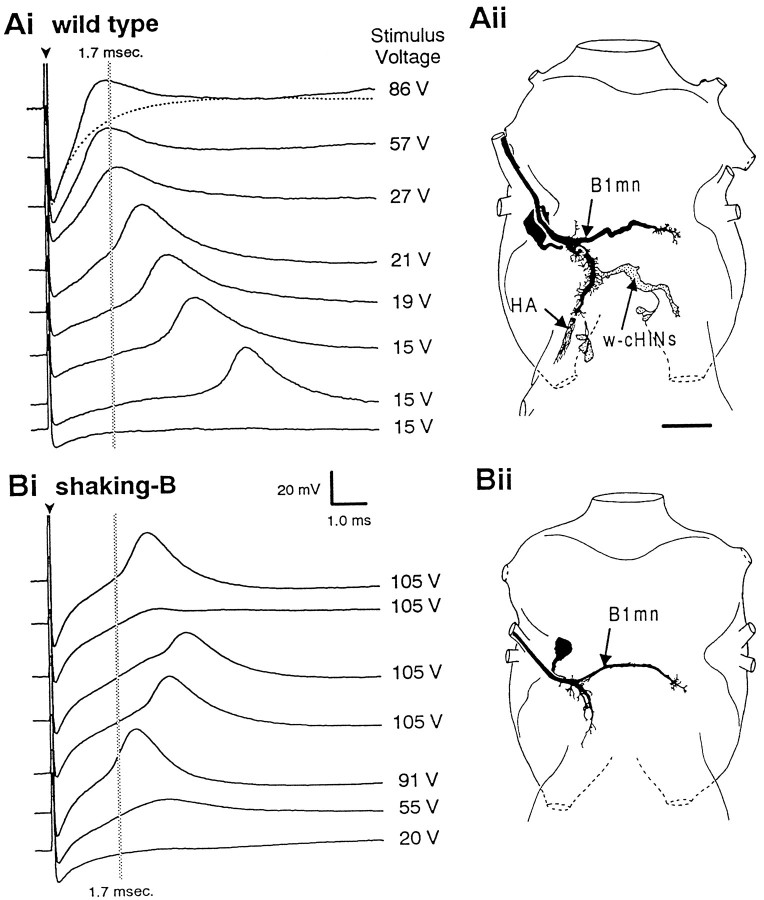

Intracellular recordings from B1mn.Ai, Action potentials recorded intracellularly from B1mn evoked by haltere afferent stimulation in a wild-type fly. Low-voltage stimuli evoke action potentials that occur at long latencies. As the stimulus intensity is increased, the latency from the stimulus to the action potential decreases. Strong stimuli evoke action potentials that occur at extremely short latencies (<1.7 msec), resulting in the peak of the action potential being partially obscured by the stimulus artifact. The dotted line in the top trace is the stimulus artifact when the electrode was adjacent to, but not in, the cell and can be used as a reference to illustrate that the action potential is obscured partially by the stimulus artifact. The arrowhead marks the stimulus artifact. Thegray vertical line is at 1.7 msec and denotes the average latency at which haltere afferent stimulation evokes short-latency EMGs from the B1 muscle in wild type (see Fig. 2).Aii, Camera lucida drawing of an intracellularly stained B1mn from a wild-type fly (dorsal view). Neurobiotin was injected intracellularly into B1mn and passed to haltere afferents and w-cHINs. Scale bar, 20 μm. Bi, Action potentials recorded intracellularly from B1mn evoked by haltere afferent stimulation in ashaking-B2 fly. At all stimulus voltages action potentials were evoked with variable and abnormally long latencies (>1.7 msec). Unlike in wild-type flies, action potentials inshaking-B2 flies were never obscured by the stimulus artifact. Occasionally, strong stimuli did not evoke action potentials in shaking-B2 flies (second trace from the top).Bii, Camera lucida drawing of an intracellularly stained B1mn from a shaking-B2 fly (dorsal view). Neurobiotin was injected intracellularly into B1mn and did not pass to any other neurons. Scale bar is the same as in Ai.

Several neurons, in addition to haltere afferents, were consistently dye-coupled to B1mn (Fig. 1C, Tables 1, 2). In 100% of the preparations, neurobiotin introduced into B1mn by retrograde staining from the B1 muscle passed trans-synaptically to a set of large, contralaterally projecting haltere interneurons (cHINs) that exhibit a structure similar to neurons described by Strausfeld and Seyan (1985)(Fig. 1C, Tables 1, 2). These cHINs are so named because they extend from the posterior branch of B1mn and terminate at the medial tuft of the contralateral haltere projection and are distinguished as wing-related contralaterally projecting haltere interneurons (w-cHINs) (Fig. 1C). In 63% of the preparations, anterior-projecting neurons (APNs) also were dye-coupled to B1mn (Fig. 1C, Tables 1, 2). Neurobiotin introduced into B1mn by direct intracellular injection also revealed that B1mn is dye-coupled to APNs and w-cHINs (Fig. 4Aii). Twenty-one B1mns successfully were injected intracellularly with neurobiotin, all of which passed dye to either APNs or w-cHINs or both. Regardless of the method used to introduce neurobiotin into B1mn, neurobiotin routinely passed trans-synaptically from B1mn to APNs and w-cHINs, suggesting that gap junctions exist between B1mn and these neurons.

In addition to the large B1mn, retrograde staining from the B1 muscle also consistently revealed a small ventral neuron in both wild-type (Fig. 1Cii) and shaking-B2 (Fig.1D) flies. This small neuron has a morphology similar to that of ventral unpaired median cells (VUMs) inDrosophila larvae (Goodman et al., 1988; Sink and Whitington, 1991) and other insects (Brookes and Weevers, 1988; Eckert et al., 1992; Stevenson et al., 1992; Pflüger et al., 1993;Monastirioti et al., 1995). Its cell body lies ventrally between the mesothoracic leg neuromeres from which it extends a small diameter (∼1 μm) neurite dorsally that bifurcates, extends laterally to the wing neuropil, and exits the ganglia on both sides through the ADMNs. The bilateral axon extends through the ADMNs to the periphery and is most likely the smaller axon innervating the B1 muscle (King and Tanouye, 1983; Fayyazuddin and Dickinson, 1996; Tu and Dickinson, 1996). This VUM-like neuron is retrogradely stained from the B1 muscle and is not dye-coupled to B1mn.

Dye in haltere afferents consistently passed trans-synaptically to several neurons in addition to B1mn (Fig. 1A, Tables 1, 2). In 100% of the preparations, neurobiotin in haltere afferents passed trans-synaptically to two classes of cHINs (Fig.1A, Tables 1, 2). One class of cHINs is likely to be the contralateral homologs of the w-cHINs coupled to B1mn (Fig.1A). These w-cHINs extend from the medial tuft of the haltere projection and terminate at the lateral edge of the mesothoracic decussation in the contralateral wing neuropil (Fig.1A). The second class of cHINs extends from the medial tuft of the haltere projection and terminates in the contralateral prothoracic neuromere (Fig. 1A). These cHINs arborize among the neurites of neck motoneurons and are distinguished as neck-related contralaterally projecting interneurons (n-cHINs) (Fig. 1A). Strausfeld and Seyan (1985)identified a similar set of n-cHINs dye-coupled to haltere afferents inCalliphora. The dye coupling we consistently observed between haltere afferents and cHINs suggests that gap junctions exist between haltere afferents and cHINs. Dye coupling from haltere afferents to motoneurons (DLMs) innervating the dorsal longitudinal flight muscles (DLMs) was never observed.

These data show that several neurons are dye-coupled to either haltere afferents or B1mn or both and indicate that gap junctions exist between a specific set of flight-related neurons in wild-type flies. In particular, dye consistently passed reciprocally between haltere afferents and the ipsilateral B1mn, suggesting that monosynaptic electrical synapses exist between haltere afferents and B1mn.

shaking-B2 abolishes dye coupling between haltere afferents and B1mn

Mutations in shaking-B eliminate dye coupling and electrical synapses among neurons in the giant fiber circuit ofDrosophila (Thomas and Wyman, 1984; Baird et al., 1990,1993; Phelan et al., 1996; Sun and Wyman, 1996). To test whether dye coupling between haltere afferents and B1mn also is eliminated inshaking-B2 flies, we stained haltere afferents anterogradely with neurobiotin. Neurobiotin did not pass trans-synaptically from haltere afferents to B1mn, n-cHINs, w-cHINs, or any other central neurons in any of the 13shaking-B2 preparations stained (Fig.1B, Tables 1, 2).

It is possible that the elimination of dye coupling between haltere afferents and central neurons in shaking-B2flies results from changes in the projections ofshaking-B2 haltere afferents; however, haltere projections in shaking-B2 flies did not differ from those described for wild-type flies. Inshaking-B2 flies haltere afferents project into the thoracic ganglia through the haltere nerve and extend through the dorsal regions of the mesothoracic and prothoracic neuromeres before exiting through the cervical connective (Fig. 1B). In the thoracic ganglia haltere afferents branch into two tufts of arbors: medial tuft (mt) and lateral tuft (lt) (Fig. 1B). Owing to the dye coupling we observed with neurobiotin in wild-type flies, we were unable to compare directly the haltere afferent projections in wild-type and shaking-B2 flies. Nevertheless, the haltere projections we describe inshaking-B2 flies are consistent with those described for wild-type flies when stained with dyes that do not result in dye coupling [compare Fig. 1B with Fig. 4 inGhysen (1978) and Fig. 5 in Palka et al. (1979)]. Although haltere afferents in shaking-B2 flies might exhibit more subtle changes not perceived with the light microscope without disrupting the gross anatomy of haltere afferents, dye coupling between haltere afferents and central neurons is eliminated inshaking-B2 flies.

To confirm that the shaking-B2 mutation eliminated dye coupling between haltere afferents and B1mn, we examined dye coupling from B1mn to haltere afferents. The B1mn was stained retrogradely from the B1 muscle, and neurobiotin did not pass from B1mn to haltere afferents, APNs, w-cHINs, or any other central neurons in any of the 10 shaking-B2 preparations stained (Fig. 1D, Tables 1, 2). Similarly, neurobiotin introduced into B1mn by direct intracellular injection also did not pass trans-synaptically from B1mn to haltere afferents or to any central neurons in shaking-B2 flies (Fig.4Bii). Five B1mns successfully were injected intracellularly with neurobiotin, none of which passed dye to any other neurons.

Regardless of the method used to introduce neurobiotin into B1mn, the morphology of B1mn did not differ from that observed in wild-type flies (compare Fig. 1D with Figs. 3, 4 in Trimarchi and Schneiderman, 1994). In shaking-B2 flies B1mn has a large ventral cell body, an axon in the ADMN, and two primary dorsal neurites, one that projects posteriorly and the other that projects to the contralateral wing neuropil through the mesothoracic decussation. In addition, the shaking-B2mutation does not result in an obvious change in the number or morphology of secondary branches of B1mn. Although it is possible that the B1mn in shaking-B2 flies and the B1mn in wild-type flies exhibit differences not perceived with the light microscope, the morphological features of B1mn inshaking-B2 flies are consistent with those known for B1mn in wild-type flies (Trimarchi and Schneiderman, 1994). Thus, without disrupting the gross anatomy of B1mn, dye coupling between B1mn and other neurons is eliminated in shaking-B2flies.

shaking-B2 alters the physiology of haltere afferent-to-B1mn synapses

The dye coupling between haltere afferents and B1mn in wild-type flies suggests that monosynaptic electrical synapses exist among these neurons. Consistent with this dye coupling, extracellular stimulation of haltere afferents reliably evokes electromyograms (EMGs) from B1 in wild-type flies (Fig. 2). Strong stimuli (>50 V) evoke B1 EMGs at short and constant latencies of 1.72 ± 0.16 msec (Fig.2). Although the mean response latency is 1.7 msec, it is important to note that all responses evoked by strong stimuli occurred at latencies <2.1 msec. On the basis of conduction velocities of insect axons (Pearson et al., 1970) and taking into account the length and diameter of the haltere afferent and B1mn axons (Smith, 1969; Trimarchi and Schneiderman, 1994), the expected conduction time from the haltere to the B1 muscle is ∼1.7 msec. Therefore, these short and consistent EMG latencies (∼1.7 msec) accompanied by dye coupling between haltere afferents and B1mn are consistent with activation of B1mn through monosynaptic electrical synapses (see Discussion).

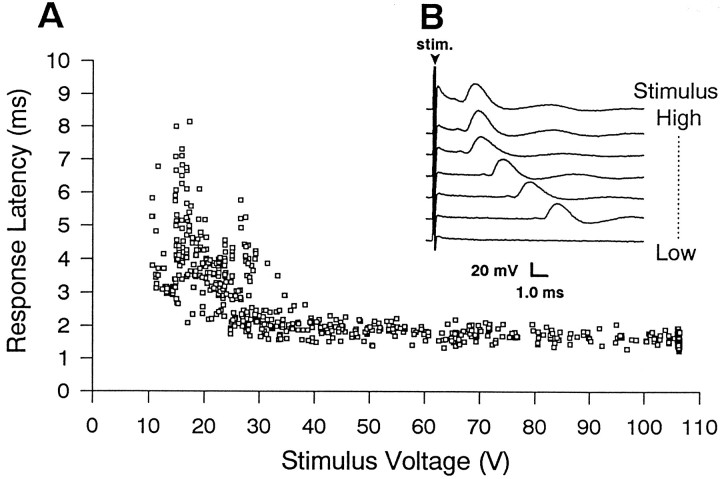

Fig. 2.

In wild-type flies stimulation of haltere afferents evokes EMGs from B1. A, Summary of B1 EMG latencies evoked by a range of stimulus intensities (n = 6 flies). Low-voltage stimuli (<30 V) evoke B1 EMGs at long and variable latencies (2.1–8.5 msec), consistent with the activation of B1mn via a polysynaptic pathway. Stronger stimuli evoke B1 EMGs at a constant short latency of, on average, 1.7 msec, consistent with the activation of B1mn via monosynaptic electrical synapses. All six flies displayed similar response profiles, exhibiting B1 EMGs at both long and short latencies. B, Sample B1 EMGs evoked by an ascending series of stimulus intensities applied to haltere afferents. The bottom trace was evoked by the weakest stimulus intensity, and as the stimulus intensity was increased, the latency from the stimulus to the evoked EMG from B1 decreased. The arrowhead marks the stimulus artifact. Response latencies were measured from the onset of the stimulus to the onset of the evoked EMG.

Weaker stimuli (<50 V), in contrast, evoke B1 EMGs at long and variable latencies (2.1–8.5 msec) (Fig. 2). Long and variable response latencies could arise from a variety of physiological phenomena, including synaptic summation, monosynaptic chemical pathways, and polysynaptic pathways. The gradual change in response latencies evoked as the stimulus strength was increased from 10 to 50 V prevented the unambiguous characterization of the underlying pathways. We, therefore, concentrated our analysis on the short-latency B1 EMGs evoked only by strong stimuli (>50 V).

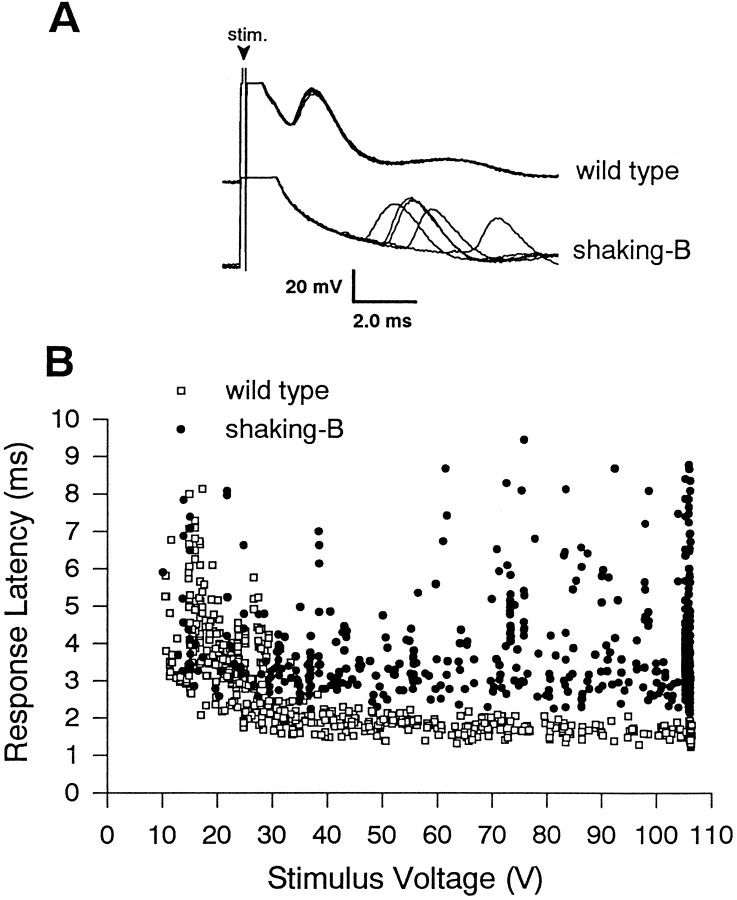

In shaking-B2 flies the dye coupling between haltere afferents and B1mn is eliminated; nevertheless, stimulation of haltere afferents evokes EMGs from B1 (Fig. 3). The latency from strong stimulation of afferents to the evoked B1 EMGs, however, is abnormally long and variable (2.1–9.5 msec). Stimuli (>50 V) that evoke B1 EMGs at latencies <2.1 msec in all wild-type flies tested (n = 6) evoke B1 EMGs at latencies >2.1 msec in all shaking-B2 flies tested (n = 6) (Fig. 3). These longer response latencies observed inshaking-B2 flies could arise from abnormal postsynaptic summation; however, these latencies are consistent with activation of B1mn via pathways other than monosynaptic electrical synapses (for example, monosynaptic chemical synapses). The elimination of dye coupling between haltere afferents and B1mn inshaking-B2 flies is in agreement with this later interpretation of the longer EMG latencies (see Discussion). Flies mutant for Passover, another allele of shaking-B, yielded results similar to shaking-B2, and Oregon-R flies, another wild-type control stock, yielded results similar to Canton-S flies.

Fig. 3.

In shaking-B2flies stimulation of haltere afferents evokes EMGs from B1 with abnormally long latencies. A, B1 EMGs evoked by haltere afferent stimulation at 80 V. The five B1 EMGs evoked consecutively from a wild-type fly occur at similar latencies (∼1.7 msec). In contrast, the five B1 EMGs evoked consecutively from ashaking-B2 fly occur at longer (>2.1 msec) and more variable latencies. The arrowhead marks the stimulus artifact. B, Summary of B1 EMGs latencies evoked by a range of stimulus intensities (n = 6shaking-B2 flies, 6 wild-type flies). The wild-type data (□) have been replotted from Figure 2 and serve as a reference. Low-voltage stimuli (<50 V) evoke B1 EMGs from bothshaking-B2 (•) and wild-type flies that occur at similar long and variable latencies (2.1–9.5 msec). By contrast, stimuli (>50 V) that evoke B1 EMGs at latencies <2.1 msec in all wildtype flies tested (n = 6) evoke B1 EMGs at latencies >2.1 msec in allshaking-B2 flies tested (n = 6). Importantly, many of the strong stimuli evoke EMGs from shaking-B2 flies that occur at latencies 0.5–2.2 msec longer than 1.7 msec (see Discussion). The vertical cluster of shaking-B2 data points at the far right of the graph result from stimuli of 105 V that evoked B1 EMGs occurring at a wide range of latencies (2.1–9.5 msec). A similar number of data points were gathered from wild-type flies but exhibited remarkably constant latencies (<2.1 msec), and thus the plotted points overlap (also see Fig. 2).

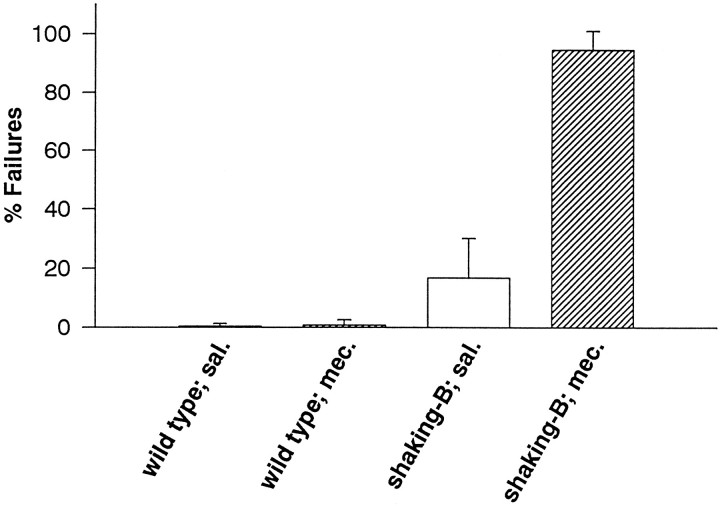

Chemical synapses tend to be less reliable than electrical synapses (Bennett, 1977), and strong stimulation of haltere afferents evokes B1 EMGs in shaking-B2 flies less reliably than in wild-type flies (17% failures in shaking-B2flies as compared with <1% failures in wild-type flies at 1 Hz stimulation; also see Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained at 5 and 10 Hz stimulation (data not shown). Together, the lack of dye coupling, longer response latencies, and less reliable activation of B1mn inshaking-B2 flies suggest that the electrical synapses present in wild-type flies are no longer present inshaking-B2 flies and that chemical synapses likely persist.

Fig. 5.

Mecamylamine blocks B1 EMGs evoked by haltere afferent stimulation in shaking-B2 flies, but not wild-type flies. The percentage of stimuli that failed to evoke EMGs in shaking-B2 flies was increased dramatically by the presence of mecamylamine (17% in saline; 95% in mecamylamine). The percentage of stimuli that failed to evoke EMGs in wild-type flies was not increased by the presence of mecamylamine (<1% in saline; <1% in mecamylamine).

Despite this agreement between the anatomical results and EMG latencies, it is possible that the abnormal B1 EMG latencies observed in shaking-B2 flies (Fig. 3) result from a peripheral deficit between the B1mn and the B1 muscle rather than from a central deficit between the afferents and B1mn. To determine whether the shaking-B2 mutation altered the synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn, we recorded intracellularly from B1mn and stimulated haltere afferents in wild-type (n = 5) and shaking-B2 flies (n = 2) (Fig. 4). These recordings demonstrate that the synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn are abnormal inshaking-B2 flies and that the timing of these mutant synapses can account for the abnormal EMG latencies recorded from the B1 muscle in shaking-B2 flies. These recordings, however, do not rule out the existence of additional defects between the motoneuron and the muscle inshaking-B2 flies.

In wild-type flies low-voltage stimulation evokes action potentials in B1mn that occur at long and variable (>1.7–9.0 msec) latencies. As the stimulus strength was increased, the latency from the stimulus to the evoked B1mn action potential decreased. Strong stimuli evoked action potentials that occur at latencies <1.7 msec and resulted in the peak of the action potential being partially obscured by the stimulus artifact (Fig. 4Ai, top traces). The action potentials that occur at short latencies (<1.7 msec) resulted in the short-latency B1 EMGs that occurred at <2.1 msec.

In contrast, in shaking-B2 flies action potentials in B1mn evoked by haltere stimulation occurred at abnormally long latencies (Fig. 4Bi). Throughout the range of stimulus strengths action potentials were evoked at latencies >1.7 msec. In particular, strong stimuli that reliably evoked action potentials from B1mn at latencies <1.7 msec in wild-type flies (Fig.4Ai) evoked action potentials from B1mn at latencies >1.7 msec in shaking-B2 flies (Fig.4Bi). Unlike in wild-type flies, stimulation of haltere afferents in mutants did not evoke any action potentials that occurred at latencies short enough to be obscured by the stimulus artifact. The action potentials in shaking-B2flies occurring at >1.7 msec resulted in B1 EMGs that occurred at latencies >2.1 msec.

These intracellular recordings from B1mn confirm that the site of the defect in shaking-B2 flies is at the synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn. Moreover, these data, together with the dye coupling (Figs. 1A,C,4Aii), suggest that, in wild-type flies, monosynaptic electrical synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn give rise to B1mn action potentials that occur at short latencies (<1.7 msec; Fig.4Ai), which, in turn, result in short-latency B1 EMGs that occur at <2.1 msec (Figs. 2, 3). In contrast, inshaking-B2 flies the dye coupling between haltere afferents and B1mn is abolished (Figs. 1B,D,4Bii), and strong stimulation of haltere afferents evokes B1mn action potentials that occur at abnormally long latencies (>1.7 msec; Fig. 4Bi), which, in turn, result in B1 EMGs that occur at latencies >2.1 msec (Fig. 3). These data indicate that, in shaking-B2 flies, the monosynaptic electrical synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn have been eliminated (see Discussion).

Mecamylamine blocks the synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn in shaking-B2 flies

The elimination of electrical synapses by theshaking-B2 mutation does not prevent stimulation of haltere afferents from evoking responses from B1mn (Figs. 3, 4). It is possible that a few electrical synapses remain inshaking-B2 flies; however, theshaking-B2 mutation results in a stop codon in the signal and thereby does not produce any functional protein and behaves as a fully penetrant genetic null. Moreover, all dye coupling is completely eliminated in shaking-B flies; none of the 23 shaking-B flies we stained showed any signs of dye coupling. As a result, it is unlikely that some gap junctions remain inshaking-B2 flies, but rather, that chemical synapses underlie these responses that persist in shaking-Bflies. Most insect sensory neurons use the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (Satelle, 1985), and choline acetyltransferase immunoreactivity, indicative of acetylcholine production, is observed in haltere sensory neurons (Gorczyca and Hall, 1987). To test whether the synapses that persist in shaking-B2 flies are cholinergic, we recorded EMGs from B1 in the presence of mecamylamine, a nicotinic cholinergic antagonist, in invertebrates, including Drosophila (Gorczyca et al., 1991; Albert and Lingle, 1993; Trimmer and Weeks, 1993).

In shaking-B2 flies 0.5 mmmecamylamine blocked the chemical synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn, resulting in a change in the percentage of stimuli that fail to evoke B1 EMGs (% Failures; Fig. 5). Stimulation of haltere afferents in the presence of mecamylamine rarely evoked EMGs from B1, and >95% of the stimuli failed to evoke EMGs (Fig. 5). In saline, by contrast, only 20% of the stimuli failed to evoke B1 EMGs (Fig. 5). Mecamylamine concentrations as low as 0.2 mm blocked EMGs from shaking-B2flies. Thus, the synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn inshaking-B2 flies are blocked by mecamylamine and are likely to be cholinergic.

As a control for nonspecific effects, we tested whether mecamylamine altered the percentage of failures in wild-type flies. The B1 EMGs evoked by strong stimulation in wild-type flies seem to result from activation of B1mn via electrical synapses and, therefore, should be resistant to mecamylamine. However, if mecamylamine is acting nonspecifically inshaking-B2 flies, then it also should block B1 EMGs in wild-type flies. Mecamylamine (0.5 mm) did not change the percentage of stimuli that failed to evoke a B1 EMG (0.5% failures in saline, 0.8% failures in mecamylamine; Fig. 5), nor did it change the latencies of these EMGs in wild-type flies (data not shown). Mecamylamine concentrations as high as 1.2 mm did not block B1 EMGs from wild-type flies (data not shown). These results indicate that mecamylamine does not act via nonspecific effects, but rather, that the B1 EMGs blocked in shaking-B2 flies result from mecamylamine acting specifically on chemical synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn.

DISCUSSION

We identified electrical and chemical synapses between haltere afferents and the B1 flight motoneuron in adultDrosophila and demonstrated that mutations inshaking-B disrupt only the electrical synapses. Haltere afferents are dye-coupled to B1mn, and strong stimulation of haltere afferents reliably evokes B1 EMGs at short and constant latencies. The mutation shaking-B2 abolishes dye coupling between haltere afferents and slows synaptic transmission. Intracellular dye injection and recordings from B1mn confirm that the defect in shaking-B2 flies exists at the central synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn. In addition, we show pharmacologically that the persisting synapses inshaking-B2 flies are likely to be cholinergic. Together, these results suggest that electrical and chemical synapses coexist between haltere afferents and B1mn, that the electrical synapses require shaking-B, and that the chemical synapses are likely to be cholinergic.

Electrical and chemical synapses coexist between haltere afferents and the B1mn

Our most telling evidence for monosynaptic electrical synapses in this pathway is that haltere afferents are dye-coupled reciprocally to B1mn in wild-type flies (Figs. 1, 4Ai, Tables 1, 2). The shaking-B2 mutation, known to eliminate electrical synapses in the giant fiber circuit (Thomas and Wyman, 1984;Baird et al., 1990, 1993; Phelan et al., 1996; Sun and Wyman, 1996), abolished this dye coupling between haltere afferents and B1mn (Fig. 1, Tables 1, 2). Dye coupling often is indicative of an electrotonic connection (Strausfeld and Bassemir, 1983; Pereda et al., 1995), and our physiological data support the idea that electrical synapses exist between haltere afferents and B1mn and that these electrical synapses are eliminated in shaking-B2 flies. In wild-type flies strong stimulation of haltere afferents evokes action potentials recorded intracellularly from B1mn that occur at extremely short latencies (<1.7 msec; Fig. 4). In shaking-B2flies similar stimulation of haltere afferents results in action potentials recorded intracellularly from B1mn at abnormally long latencies (>1.7 msec; Fig. 4). These data support the conclusion that synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn have a monosynaptic electrical component that depends on shaking Bexpression.

This electrical connection is consistent with findings in the larger fly, Calliphora, in which dye coupling from haltere afferents to B1mn was demonstrated with two different tracers: cobalt (Hausen et al., 1988; Hengstenberg et al., 1988) and neurobiotin (Fayyazuddin and Dickinson, 1996). In addition, recordings from the dendrite of the B1mn in Calliphora demonstrate that synaptic potentials evoked by haltere stimulation are biphasic. The early phase occurred at a constant short latency, was calcium-independent, and did not fatigue on repetitive stimulation, suggesting that it results from monosynaptic electrical synapses. The later phase occurred with a slight delay, is calcium-dependent, and fatigues on repetitive stimulation, suggesting that it results from monosynaptic chemical synapses. Synaptic potentials resulting from chemical synapses typically follow those of electrical synapses by 0.5–2.2 msec, and in the larger fly a similar delay exists between the early and later phases of the biphasic B1mn synaptic response (Bennett, 1977; Lin and Faber, 1988; Perrins and Roberts, 1995; Fayyazuddin and Dickinson, 1996).

Several observations suggest that, similar to Calliphora,Drosophila also exhibits chemical synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn. First, choline acetyltransferase immunoreactivity is observed in Drosophila haltere sensory neurons (Gorczyca and Hall, 1987), suggesting that these neurons make acetylcholine. Second, when electrical synapses were removed genetically byshaking-B mutations, chemical synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn were uncovered. We found that the B1 EMGs evoked by haltere afferent stimulation in shaking-B2 flies occurred at latencies 0.5–2.2 msec longer than B1 EMGs evoked by similar stimulation in wild-type flies (Fig. 3). These longer latencies observed in shaking-B2 flies are consistent with a shift from activation of B1mn via monosynaptic electrical synapses in wild-type flies to activation of B1mn via monosynaptic chemical synapses in shaking-B2 flies. Third, chemical synapses tend to be less reliable than electrical synapses (Bennett, 1977), and in both species of flies responses presumed to result from chemical synapse were less reliable than those resulting from electrical synapse. For example, stimulation of haltere afferents inshaking-B2 flies evokes B1 EMGs less reliably than in wild-type flies [17% failures inshaking-B2 flies as compared with <1% failures in wild-type flies at 1 Hz (Fig. 5); similar results were obtained at 5 and 10 Hz]. Finally, we show that, although theshaking-B2 mutation eliminates electrical synapses, synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn persist, are blocked by mecamylamine, and are, therefore, likely to be cholinergic chemical synapses (Fig. 5). Together, these data suggest that the synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn have a monosynaptic chemical component that is like to be cholinergic, as well as the electrical component described above.

It is possible that single afferents exhibit both electrical and chemical synapses with B1mn. Mixed synapses have been identified between afferents and central neurons in several other systems [leech:Nicholls and Purves (1970), Stuart (1970); alligator lizard: Szpir et al. (1995); goldfish: Lin and Faber (1988)]. However, neither our results in Drosophila nor those in Calliphora can distinguish whether individual haltere afferents exhibit mixed electrochemical synapses or whether two separate populations of afferents exist. In any event, the results in the two species of flies are completely consistent and demonstrate strong electrical synapses between haltere afferents and B1mn that coexist with chemical synapses.

Our data also suggest that haltere afferents can activate B1mn via a polysynaptic pathway. Low-voltage stimulation (<50 V) of haltere afferents evokes B1 EMGs that occur at long and variable latencies, indicative of a polysynaptic pathway (Figs. 2, 4). It is likely that changes in recruitment of afferents, synaptic summation, and polysynaptic pathways underlie the gradual change in B1 latency observed as the stimulus voltage is increased from 0–50 V. Therefore, we have concentrated on the short-latency monosynaptic pathways by stimulating with high voltages.

It is possible that only electrical synapses exist between haltere afferents and B1mn in wild-type Drosophila and that theshaking-B2 mutation not only genetically removes the electrical synapses but also induces compensatory construction of cholinergic chemical synapses. However, comparison of the haltere afferents-to-B1mn synapses in Calliphora to those inDrosophila argue against this. Fayyazuddin and Dickinson (1996) determined that in Calliphora both electrical and chemical synapses exist between haltere afferents and B1mn. The data we present are consistent with these findings and suggest that both electrical and chemical synapses also exist between haltere afferents and B1mn in wild-type Drosophila.

shaking-B is required at many synapses

Mutations in shaking-B were shown previously to disrupt electrical synapses in the giant fiber circuit (Thomas and Wyman, 1984;Krishnan et al., 1993; Sun and Wyman, 1996). In situhybridization with cDNA probes indicates that shaking-Bexpression is concentrated in a set of neurons presumed to be those in the giant fiber circuit (Krishnan et al., 1993; Crompton et al., 1995). Similarly, Phelan et al. (1996) show that shaking-Bimmunoreactivity is localized to synaptic sites among members of the giant fiber circuit. Although emphasis has been on the selectivity of the shaking-B expression and the selective disruption of the giant fiber circuit by shaking-B2 mutations, we demonstrate here that the shaking-B2 mutation eliminates electrical synapses among a variety of other neurons. Thus, we hypothesize that shaking-B is required for electrical synapses throughout the fly nervous system.

Several observations support this hypothesis. Theshaking-B2 flies exhibit many behavioral deficits. The original description of theshaking-B2 phenotype by Homyk et al. (1980)includes hyperactivity, inability to fly, improper leg positioning and movements during tethered flight, and abnormal electroretinograms.Balakrishnan and Rodrigues (1991) determined thatshaking-B2 flies exhibit defects in gustatory responses to sucrose, NaCl, and KCl. Crompton et al. (1995) describeshaking-B2 flies as defective in courtship, andPhillis et al. (1993) show that shaking-B2 flies are defective in grooming behavior. It is unlikely that specific elimination of electrical synapses in the giant fiber circuit or between haltere afferents and the B1mn accounts for this wide array of behavioral deficits. Rather, it is more likely thatshaking-B expression is required for electrical synapses among many Drosophila neurons.

Indeed, studies that demonstrate that shaking-B expression is localized specifically to members of the giant fiber circuit also describe low levels of shaking-B expression throughout the nervous system, including cells of the medulla, lobula, and almost all of the cells of the thoracic nervous system (Krishnan et al., 1993;Crompton et al., 1995). Consistent with a more ubiquitous expression pattern of shaking-B, Phelan et al. (1996) describeshaking-B immunoreactivity in several regions of the nervous system other than those occupied by neurons of the giant fiber circuit. Thus, although shaking-B expression is concentrated in a few specific neurons, the more general low levels of expression throughout the nervous system have profound functional consequences, and mutations in shaking-B result in disruption of many synapses and many behaviors.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a postdoctoral National Research Service Award F32 NS 09700 (to J.R.T.) and Grant NS15571 from National Institutes of Health (to R.K.M.). We thank Dr. R. J. Wyman for kindly providing the shaking-B2 stock and M. A. Friedman and P. Caruccio for assistance with the neurobiotin protocol. We also thank Dr. B.A. Trimmer for suggesting the use of mecamylamine and Dr. Randy Phillis and members of the R. K. Murphey lab for suggestions on experimental design and help with this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. James R. Trimarchi at the above address.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albert JL, Lingle CJ. Activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on cultured Drosophila and other insect neurons. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;463:605–630. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baird DH, Schalet AP, Wyman RJ. The Passover locus in Drosophila melanogaster: complex complementation and different effects on the giant fiber neural pathway. Genetics. 1990;126:1045–1059. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.4.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baird DH, Koto M, Wyman RJ. Dendritic reduction in Passover, a Drosophila mutant with defective giant fiber neuronal pathway. J Neurobiol. 1993;24:971–984. doi: 10.1002/neu.480240710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balakrishnan R, Rodrigues V. The shaker and shaking-B genes specify elements in the processing of gustatory information in Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Biol. 1991;157:161–181. doi: 10.1242/jeb.157.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett MVL. Electrical transmission: a functional analysis and comparison to chemical transmission. In: Brookhart JM, Mountcastle VB, editors. Handbook of physiology: the nervous system. American Physiological Society; Bethesda, MD: 1977. pp. 357–416. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brookes SJH, Weevers R deG. Unpaired median neurons in a lepidopteran larva (Antheraea pernyl). I. Anatomy and physiology. J Exp Biol. 1988;136:311–332. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan WP, Dickinson MH. Position-specific central projections of mechanosensory neurons on the haltere of the blowfly, Calliphora vicina. J Comp Neurol. 1996;369:405–418. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960603)369:3<405::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coggshall JC. Neurons associated with the dorsal longitudinal flight muscles of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 1978;177:707–719. doi: 10.1002/cne.901770410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole ES, Palka J. The pattern of campaniform sensilla on the wing and haltere of Drosophila melanogaster and several of its homeotic mutants. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1982;71:41–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crompton D, Todman M, Wilkins M, Ji S, Davies J. Essential and neural transcripts from the Drosophila shaking-B locus are differentially expressed in the embryonic mesoderm and pupal nervous system. Dev Biol. 1995;170:142–158. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckert M, Rapus J, Nörnberger A, Penzlin H. A new specific antibody reveals octopamine-like immunoreactivity in cockroach ventral nerve cord. J Comp Neurol. 1992;322:1–15. doi: 10.1002/cne.903220102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fayyazuddin A, Dickinson MH. Haltere afferents provide direct, electrotonic input to a steering motoneuron in the blowfly, Calliphora. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5225–5232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05225.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghysen A. Sensory neurones recognize defined pathways in Drosophila central nervous system. Nature. 1978;274:869–872. doi: 10.1038/274869a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman CS, Bastiani MJ, Doe CQ, du Lac S, Helfand SL, Kuwada JY, Thomas JB. Cell recognition during neuronal development. Science. 1988;225:1271–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.6474176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorczyca M, Hall JC. Immunohistochemical localization of choline acetyltransferase during development and in ChAT mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1361–1369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-05-01361.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorczyca M, Budnik V, White K, Wu CF. Dual muscarinic and nicotinic action on a motor program in Drosophila. J Neurobiol. 1991;22:391–404. doi: 10.1002/neu.480220407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hausen K, Hengstenberg R, Wiegand T (1988) Flight control circuits in the nervous system of the fly: convergence of visual and mechanosensory pathways onto motoneurons of steering muscles. Sense organs between environment and behavior. Proceedings of the 16th Göttingen Neurobiology Conference (Elsner N, Barth FG, eds), p 130. New York: Thieme. Location of printing is New York, NY.

- 18.Heide G. Neural mechanisms of flight control in Diptera. In: Nachtigall W, editor. BIONA report. Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur Mainz; New York: 1983. pp. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hengstenberg R, Hausen K, Hengstenberg B. Cobalt pathways from haltere mechanoreceptors to inter- and motoneurons controlling head posture and flight steering in the blowfly Calliphora. Sense organs between environment and behavior. Proceedings of the 16th Göttingen Neurobiology Conference (Elsner N, Barth FG, eds), p 129. Thieme; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Homyk T, Jr, Szidonya J, Suzuki DT. Behavioral mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. III. Isolation and mapping of mutations by direct visual observations of behavioral phenotypes. Mol Gen Genet. 1980;177:553–565. doi: 10.1007/BF00272663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikeda K, Kaplan WD. Neurophysiological genetics in Drosophila melanogaster. Am Zool. 1974;14:1055–1066. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda K, Koenig JH. Morphological identification of motor neurons innervating the dorsal longitudinal flight muscle of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 1988;273:436–444. doi: 10.1002/cne.902730312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keshishian H, Broadie K, Chiba A, Bate M. The Drosophila neuromuscular junction: a model system for studying synaptic development and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:45–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.002553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King DG, Tanouye MA. Anatomy of motor axons to direct flight muscle in Drosophila. J Exp Biol. 1983;105:231–239. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koenig JH, Ikeda K. Characterization of the intracellularly recorded response of identified flight motor neurons in Drosophila. J Comp Physiol [A] 1983;150:295–303. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krishnan SN, Frei E, Swain GP, Wyman RJ. Passover: a gene required for synaptic connectivity in the giant fiber system of Drosophila. Cell. 1993;73:967–977. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90274-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin J-W, Faber DS. Synaptic transmission mediated by single club endings on the goldfish Mauthner cell. I. Characteristics of electrotonic and chemical postsynaptic potentials. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1302–1312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-04-01302.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monastirioti M, Gorczyca M, Rapus J, Eckert M, White K, Budnik V. Octopamine immunoreactivity in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 1995;356:275–287. doi: 10.1002/cne.903560210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicholls JG, Purves D. Monosynaptic chemical and electrical connexions between sensory and motor cells in the central nervous system of the leech. J Physiol (Lond) 1970;209:647–667. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palka J, Lawrence PA, Hart HS. Neural projection patterns from homeotic tissues of Drosophila studied in bithorax mutants and mosaics. Dev Biol. 1979;69:549–575. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(79)90311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearson KG, Stein RB, Malhotra SK. Properties of action potentials from insect motor nerve fibers. J Exp Biol. 1970;53:299–316. doi: 10.1242/jeb.53.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereda AE, Bell TD, Faber DS. Retrograde synaptic communication via gap junctions coupling auditory afferents to the Mauthner cell. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5943–5955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-05943.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perrins R, Roberts A. Cholinergic and electrical synapses between synergistic spinal motoneurones in the Xenopus laevis embryo. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;485:135–144. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pflüger H-J, Witten JL, Levine RB. Fate of abdominal ventral unpaired medial cells during metamorphosis of the hawkmoth, Manduca sexta. J Comp Neurol. 1993;335:508–522. doi: 10.1002/cne.903350404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pflugstaedt H. Die halteren der Diptera. Z Wiss Zool. 1912;100:1–59. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phelan P, Nakagawa M, Wilkin MB, Moffat KG, O’Kane CJ, Davies JA, Bacon JB. Mutations in shaking-B prevent electrical synapse formation in the Drosophila giant fiber system. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1101–1113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01101.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phillis R, Bramlage AT, Wotus C, Whittaker A, Gramates LS, Seppala D, Farahanchi F, Caruccio P, Murphey RK. Isolation of mutations affecting neural circuitry required for grooming behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1993;133:581–592. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.3.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pringle JWS. The gyroscopic mechanism of the halteres of Diptera. Philos Trans R Soc Lond [Biol] 1948;233:347–384. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Satelle DB. Acetylcholine receptors. In: Kerkut GA, Gilbert LI, editors. Comprehensive insect physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. Pergamon; Oxford, UK: 1985. pp. 395–434. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singleton K, Woodruff RI. The osmolarity of adult Drosophila hemolymph and its effect on oocyte-nurse cell electrical polarity. Dev Biol. 1994;161:154–167. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sink H, Whitington PM. Location and connectivity of abdominal motoneurons in the embryo and larva of Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurobiol. 1991;22:298–311. doi: 10.1002/neu.480220309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith DS. The fine structure of haltere sensilla in the blowfly, Calliphora erythrocephala (Meig.), with scanning electron microscopic observations on the haltere surface. Tissue Cell. 1969;1:443–484. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(69)80016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevenson PA, Pflüger H-J, Eckert M, Rapus J. Octopamine immunoreactive cell populations in the locust thoracic-abdominal nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1992;315:382–397. doi: 10.1002/cne.903150403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strausfeld NJ, Bassemir UK. Cobalt-coupled neurons of a giant fiber system of Diptera. J Neurocytol. 1983;12:971–991. doi: 10.1007/BF01153345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strausfeld NJ, Seyan HS. Convergence of visual, haltere, and prosternal inputs at neck motor neurons of Calliphora erythrocephala. Cell Tissue Res. 1985;240:601–615. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stuart AE. Physiological and morphological properties of motor neurons in the central nervous system of the leech. J Physiol (Lond) 1970;209:627–646. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun Y-A, Wyman RJ. Passover eliminates gap junctional communication between neurons of the giant fiber system in Drosophila. J Neurobiol. 1996;30:340–348. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199607)30:3<340::AID-NEU3>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szpir MR, Wright DD, Ryugo DK. Neuronal organization of the cochlear nuclei in alligator lizards: a light and electron microscopic investigation. J Comp Neurol. 1995;357:217–247. doi: 10.1002/cne.903570204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanouye MA, Wyman RJ. Motor outputs of giant nerve fiber in Drosophila. J Neurophysiol. 1980;44:405–421. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.44.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas JB, Wyman RJ. Normal and mutant connectivity between identified neurons in Drosophila. Trends Neurosci. 1983;6:214–219. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas JB, Wyman RJ. Mutations altering synaptic connectivity between identified neurons in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1984;4:530–538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-02-00530.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trimarchi JR, Schneiderman AM. Giant fiber activation of an intrinsic muscle in the mesothoracic leg of Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Biol. 1993;177:149–167. doi: 10.1242/jeb.177.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trimarchi JR, Schneiderman AM. The motor neurons innervating the direct flight muscles of Drosophila melanogaster are morphologically specialized. J Comp Neurol. 1994;340:427–443. doi: 10.1002/cne.903400311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trimmer BA, Weeks JC. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors modulate the excitability of an identified insect motor neuron. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:1821–1836. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.6.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tu MS, Dickinson MH. The control of wing kinematics by two steering muscles of the blowfly (Calliphora vicina). J Comp Physiol [A] 1996;178:719–730. doi: 10.1007/BF00225830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wyman RJ, Thomas JB, Salkoff L, King DG. The Drosophila giant fiber system. In: Eaton RC, editor. Neural mechanisms of startle behavior. Plenum; New York: 1984. pp. 133–161. [Google Scholar]