Abstract

The distinction between implicit and explicit retrieval of learned material is central to recent thinking about the neural systems underlying memory. Word stem completion is one task in which subjects can be instructed either to make a deliberate recall (explicit instruction) or to be told to complete the stem with any appropriate word (implicit instruction). Positron emission tomography (PET) studies have indicated that during implicit retrieval, there is reduced blood flow in right posterior areas, whereas some tasks of explicit retrieval involve frontal and hippocampal activation. However, there is no information about the timing of these activations or how implicit and explicit retrieval might be related.

We used word stem completion tasks similar to those used in the PET studies, but used high-density electrical recording designed to allow localization of the regions involved in the tasks and to provide temporal information. We found reduced activity for primed words in right posterior cortex corresponding to previous PET results. The reduction occurred within the first 200 msec after input, suggesting early interaction with the information stored in this area. Similar reductions observed during explicit recall of the previously presented words indicate that priming is similar under implicit and explicit conditions. In addition, when priming was not an adequate basis for response, then frontal areas were active. Retrieval of unprimed words under implicit instruction elicited right frontal activation, whereas explicit retrieval activated frontal areas bilaterally. Left frontal and hippocampal activations appear to occur only when the retrieval involved use of the words from the list studied previously.

Keywords: priming, word stem completion, implicit memory, explicit memory, hippocampus, frontal cortex, parietal cortex, temporal cortex

Recent experiments using a variety of techniques have supported the view that memory is not a unitary faculty and that different types of memory have distinct neural networks (Tulving and Schacter, 1990; Schacter et al., 1993; Nyberg et al., 1996). One such distinction is between explicit (intentional) and implicit (unintentional) retrieval (Graf and Schacter, 1985; Schacter et al., 1993).

Of particular importance are tasks in which the same material can be retrieved implicitly under one instruction and explicitly under another. In the word stem completion task, subjects learn a list of words and then later, three-letter strings are used as cues for retrieval. When the instruction is to pronounce the first word that comes to mind beginning with the three-letter stem, the subject need not be aware of any relationship to the previously learned words. Nonetheless, previously learned words are recalled with significantly higher than chance probability (Squire et al., 1992; Buckner et al., 1995). In this task, explicit retrieval strategies can be evoked by instructing the subject to retrieve words from the studied list.

Under implicit instructions, stems of the studied words (primed stems) show a reduction of blood flow in right posterior cortex when compared with unprimed stems (Squire et al., 1992; Buckner et al., 1995;Schacter et al., 1996). Frontal and hippocampal activations have been found in some tasks involving explicit retrieval (Buckner et al., 1995;Schacter et al., 1996), but the precise cognitive function associated with these activations is unclear. In addition, because positron emission tomography (PET) studies lack temporal resolution, it is uncertain whether the reduced flow in the right cortex is a result of the memory for the previously presented words stored in the right posterior area or the easier word generation that occurs when an item that has been primed simply results in reduced blood flow.

To address these questions, we recorded event-related potentials (ERPs) in 64 channels during retrieval of words from three-letter stems. In this study, explicit and implicit retrieval tasks differed only in the instructions. In the implicit task, subjects were required to pronounce the first word that came to mind, beginning with the presented stem, whereas in the explicit retrieval task, subjects were instructed to complete the stems using previously shown study words and to generate novel words only if the stems could not be completed using the study list. Stems from the primed and unprimed words were presented randomly in the same task block.

Recent studies of word association have shown that scalp-recorded ERPs can be related to PET generators by use of Brain Electric Source Analysis (BESA) algorithm (Scherg and Berg, 1995), even in complex cognitive tasks (Abdullaev and Posner, 1997; Snyder et al., 1995). In addition to the timing information, the use of ERPs allowed us to sort mixed primed and unprimed trials presented within the same list. In addition, by presenting primed and unprimed stems randomly in a single block, we ensured that the subjects did not develop a separate strategy to deal with each type of item.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The experiment was conducted in three phases on a total of 48 native English-speaking students of the University of Oregon (female, 26; mean age, 22.2 years). All subjects were paid for their participation, reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and were right-handed as assessed by Edinburgh handedness inventory questionnaires (Raczkowski et al., 1974).

In the first phase, ERPs were recorded in 24 subjects and grand averaged waveform generated. In the second phase, this experiment was repeated on 16 subjects to confirm replicability of the results. In the first two phases, subjects were tested first for implicit recall and then for explicit recall on similar paradigms. In the third phase, eight subjects were tested only for explicit recall to verify that previous exposure to the implicit task did not affect the activity during the explicit task.

For this experiment, a list of 450 words was prepared in such a way that no two words had similar first three letters (stem) and each stem made at least 10 words in Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary. Length of words varied between four and nine letters. These words were randomized, and 90 of them were separated for use as filler words that were presented before and after each study list to minimize primacy and recency effects. The remaining words were randomly divided in 12 lists of 30 words. Six of these were presented as study lists and were used to study implicit or explicit recall, whereas the remaining lists were used for the control tasks.

After informed consent was obtained, the EEG electrode net was applied and the subject was seated in a sound-attenuated chamber. In the first two phases, the experiment began with three implicit memory blocks. Each of these blocks had a word-reading stage and a stem-completion stage (Table 1). In the word reading stage, a list of 45 words was presented in upper case (black on white background). Each word was displayed for 3 sec on the center of a computer monitor. The first 9 and the last 6 words were drawn from the filler list, and 30 words from one of the study lists were shown between the fillers. Subjects were asked to assess whether the word would be easy or difficult for a child to understand and to respond by pressing either a right or left key. This task was introduced to ensure that the presented words were attended. After an interval of 2 min, the stem-completion stage began. In this stage, 60 lower case three-letter strings were shown for 3 sec each. Half of the strings were the first three letters of the previously presented study list, and the remaining strings were derived from one of the three control lists. None of the control stems could be completed using any of the study words. Stems from the two lists were presented in random order, and the task of the subject was to pronounce the first word that came to mind, beginning with the stem. They were advised not to use proper nouns and to avoid blinking before making a response. Subjects were also instructed not to make any body movements not associated with the response. Pronounced words were recorded on a tape recorder, and the voice onset latency was determined using a microphone channel connected to a voice-operated relay. While the subjects were completing stems, a scalp EEG was recorded using a 64 channel EEG electrode net (Tucker et al., 1994).

Table 1.

Scheme of experimental paradigm

| Word-reading stage (Stage 1) | Stem-completion stage (Stage 2) | Condition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implicit memory | 45 Upper case words | 30 Lower case stems (primed) | PRIMING |

| (3 Blocks) | Filler 1–9 and 40–45 | 30 Lower case stems (unprimed) | PRIMING BASELINE |

| Study list 10–39 | |||

| Explicit memory | 45 Upper case words | 30 Lower case stems (primed) | RECALL |

| (3 Blocks) | Filler 1–9 and 40–45 | 30 Lower case stems (unprimed) | RECALL BASELINE |

| Study list 10–39 |

There were three implicit memory blocks. Each block contained stems from the PRIMING condition, in which stems were derived from the words presented during word-reading stage, and the PRIMING BASELINE condition, in which no previously learned word could complete the stem. At the end of the implicit memory blocks, subjects were allowed a break for ∼5 min before beginning the three explicit memory blocks.

The explicit memory blocks had the same structure as the implicit memory blocks, but had different words/stems and instructions. In the stem-completion stage, subjects were informed that it was possible to complete some of the stems using the list of words shown in the word-reading stage and were instructed to use the study list words for completing stems whenever possible. They were allowed to make guesses and were told to come up with a novel word only if they could not recall any study list word beginning with the given stem. Tasks involving stems from the study list were designated as RECALL, and those involving stems from the control list were named RECALL BASELINE. Each subject was tested in three such blocks. Control list words were never shown to the subjects in any of the implicit or explicit memory blocks.

In the first two phases, implicit memory blocks always preceded explicit memory to reduce explicit recall effort during implicit memory blocks. In the third phase, subjects were tested only for explicit memory.

During the stem completion stage, a 1 sec EEG epoch beginning 184 msec before stem onset and sampled at 250 samples/sec was collected. The EEG samples were collected with a 0.15–50 Hz bandpass from 64 electrode sites referenced to the right mastoid channel. The signals were baseline corrected, edited off-line for exclusion of ocular and motion artifacts, and referenced algebraically to an average reference derivation. The averaged ERP data were filtered digitally with a 50 Hz low-pass filter to reduce electromyographic contamination. The ERPs were averaged separately for each of four conditions, PRIMING, PRIMING BASELINE, RECALL, and RECALL BASELINE. For comparing two conditions, difference waves were analyzed statistically using nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for each of the 4 msec samples. Where appropriate, ANOVA was used on selected windows. Two-dimensional spherical spline interpolated head surface images were created for the difference waves at 4 msec intervals to depict the temporal continuity and topography of statistical significance of difference byt test. Difference waves were also analyzed using BESA algorithm (Scherg and Berg, 1995) to determine topography of the best-fitting dipoles.

Grand averaged waveforms were generated separately for each condition for all subjects who participated in the study, and the differences were considered significant only when the probability wasp < 0.05.

RESULTS

The words produced during the stem-completion stage were analyzed to assess whether there was a difference between implicit and explicit instructions. For the words actually presented during the word-reading stage, 42.2% were produced during the stem-completion stage under implicit instruction and 47.4% under explicit instruction. This difference was significant by t test (p < 0.01). Subjects completed 18.1% of the items with words from the control list. Because subjects were never shown the control lists, generating items from this list had to occur only by chance.

In the implicit memory blocks, mean latency for completing a stem with a word that was on the previously studied list (PRIMING) was 1293 msec, whereas for words not on the list (PRIMING BASELINE), mean latency was 1311 msec. In the explicit memory blocks, latencies were longer than under implicit conditions. For primed words (RECALL), this was 1452 msec, and for unprimed (RECALL BASELINE), 1508 msec.

The longer reaction times and higher percentages of recall from the list under explicit instructions indicate an effort by subjects to recall items from the list. The lower response times and higher percentage of correct response for primed items indicate that having an item on the previously studied list increased the likelihood that it would be generated for stem completion irrespective of instructions.

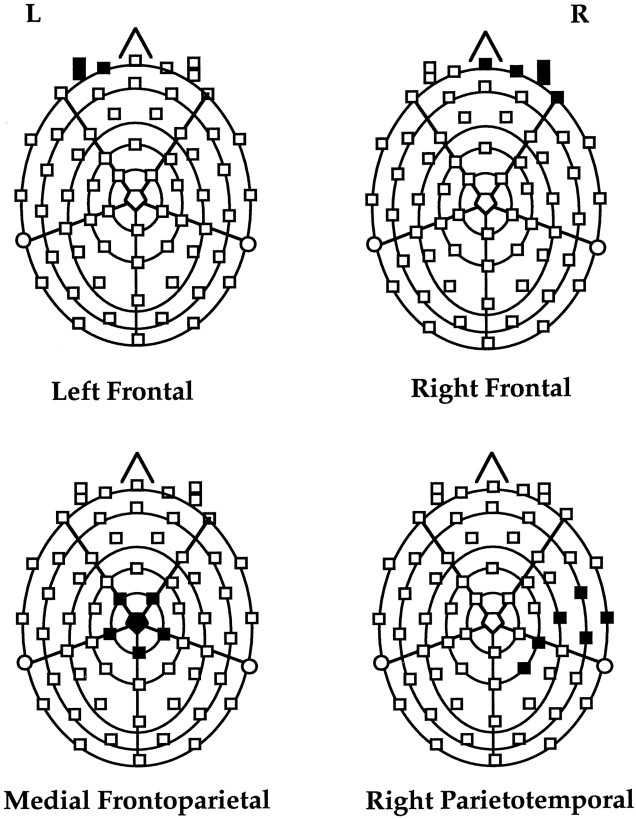

ERPs recorded using a 64 channel electrode net were average referenced, and separate grand average waveforms were plotted for each condition of the study. The channels found to have significant variation under any two conditions in phase 1 were selected for additional analyses in phases 2 and 3. Topographic location of these channels is shown in Figure 1. ERPs of the channels in each of the four regions (left frontal, right frontal, right parietotemporal, and medial frontoparietal) were collapsed, and these collapsed ERPs represented potentials in the respective areas.

Fig. 1.

Topography of the 64 channel EEG net showing location of the channels (shaded area), which showed significantly different potentials under any two task conditions in phase 1 of the study. These channels were selected for additional analyses in this study.

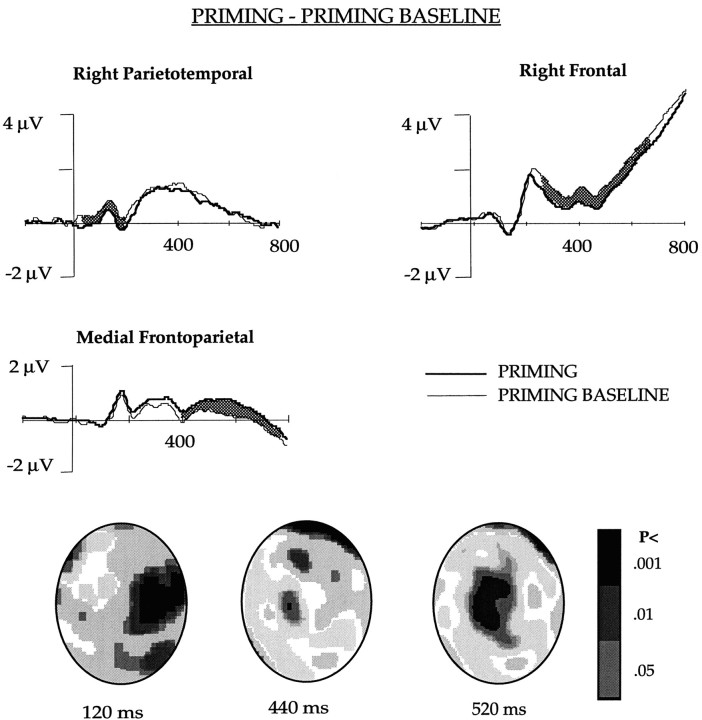

In earlier publications (Badgaiyan and Posner, 1996a,b), we reported that for primed items under implicit instruction, ERPs differed significantly from unprimed items over a set of channels in the right parietotemporal and another set in the right frontal area (Fig.2). Potentials at these two sites were collapsed separately, and the resultant ERP suggested that at both of these sites, electrical activity was less positive for words that had been primed compared with the unprimed baseline. Whereas the difference appeared early (60–200 msec) in the right parietotemporal area, it was not evident until 250 msec after stem presentation in the right frontal channels. The posterior activity seems to reflect the hypothesized reduction in activity because of priming. We hypothesized that the frontal activity might reflect the requirement that subjects have to generate an appropriate word for unprimed items when no information was stored. Such additional computation is not needed for primed items, because the response word had been stored at the word-reading stage. This may be the reason for attenuated right frontal activity in priming tasks.

Fig. 2.

The ERPs obtained in the PRIMING and PRIMING BASELINE conditions after collapsing potentials of the channels in the right parietotemporal, frontal, and medial frontoparietal regions shown in Figure 1. The waveforms differed significantly (p < 0.01) in the shaded area. The figure also shows an interpolated image of the significance of difference between the two conditions.

In addition to the attenuation of potentials over the right parietotemporal and frontal areas, the ERPs for primed words were more positive than baseline in the medial frontoparietal channels. The difference was significant after 400 msec following stimulus presentation. Interpolated images showing statistical difference between the ERPs in the PRIMING and PRIMING BASELINE items after 120, 440, and 520 msec following stem presentation are shown in Figure2.

In the explicit memory blocks, we separated stems derived from the study list (RECALL) and those derived from the control list (RECALL BASELINE). In the former condition, the subjects intentionally recalled the study words they were presented earlier, whereas in the later condition, besides making an effort to retrieve study list words, the subjects also generated an unstudied novel word, because none of the baseline stems could be completed using the study list. Thus, although both conditions required recall effort, one (RECALL) involved recall of primed (studied) words, whereas the other (RECALL BASELINE) involved retrieval of unprimed words.

Under both instruction conditions (Implicit and Explicit memory blocks), mean voice onset latency and percentage of correct retrieval differed significantly for the primed and unprimed items. To understand the neural computations involved in the recall of primed and unprimed words, grand averaged ERPs obtained during the PRIMING and PRIMING BASELINE conditions were subtracted from those obtained in primed (RECALL) and unprimed (RECALL BASELINE) conditions of the explicit memory blocks. The subtraction of PRIMING ERP from RECALL ERP represented brain activations required by recall from the list. Similarly, the subtraction of the PRIMING BASELINE ERP from the RECALL BASELINE ERP provides information about brain activity related to attempts to recall words from the list, because in both cases, subjects had to generate a novel word. Subtraction of RECALL and RECALL BASELINE could reveal how priming from previous learning influenced responses under the explicit instructions as well as influenced the additional operations needed to generate a response when subjects fail to retrieve an appropriate response from the list.

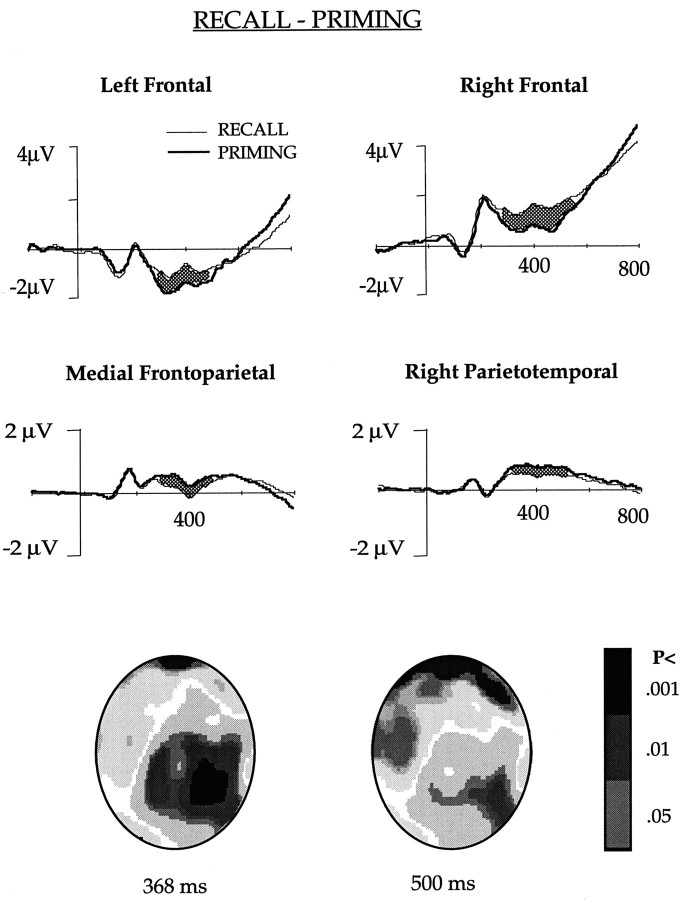

RECALL and PRIMING comparison (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3.

The ERPs obtained in the RECALL and PRIMING conditions after collapsing potentials of the channels in the left and right frontal, medial frontoparietal, and right parietotemporal regions shown in Figure 1. The waveforms differed significantly (p < 0.01) in the shaded area. The figure also shows an interpolated image of the significance of difference between the two conditions.

ERPs elicited in the RECALL and PRIMING tasks differed significantly in channels over the right and the left frontal, right parietotemporal and medial frontoparietal areas in phase 1. These channels were selected for further analysis. Grand averaged ERPs for each of these regions are shown in Figure 3.

ERPs of the RECALL and PRIMING tasks differed significantly in the left frontal channels between 312 and 496 msec. Mean amplitude between 350 and 450 msec of stem presentation was −0.9 μV in the RECALL and −1.6 μV in the PRIMING condition. Potentials in the right frontal channels differed significantly between 308 and 540 msec, and the mean potential between 350 and 450 msec in the RECALL and PRIMING task was 1.3 and 0.67 μV, respectively.

Right parietotemporal channels that differed in the PRIMING and PRIMING BASELINE subtraction between 60 and 200 msec did not show any difference during this time window in the RECALL and PRIMING subtraction. The potentials, however, differed significantly between 220 and 496 msec. During this time period, RECALL evoked less positivity than the PRIMING, and the mean potential was 1.1 μV in the PRIMING and 0.58 μV in the RECALL condition.

Medial frontoparietal channels that elicited higher potential in the PRIMING as compared with the PRIMING BASELINE after 400 msec of stem presentation showed a difference in the RECALL and PRIMING subtraction too, but the difference appeared earlier. They differed significantly between 260 and 484 msec. The PRIMING ERP was more positive than the RECALL ERP, and the mean potential between 260 and 484 msec was 0.63 and 0.22 μV, respectively, in the PRIMING and RECALL conditions.

Interpolated images showing statistical difference between the ERPs obtained in the RECALL and PRIMING conditions after 368 and 500 msec following stem presentation are shown in Figure 3.

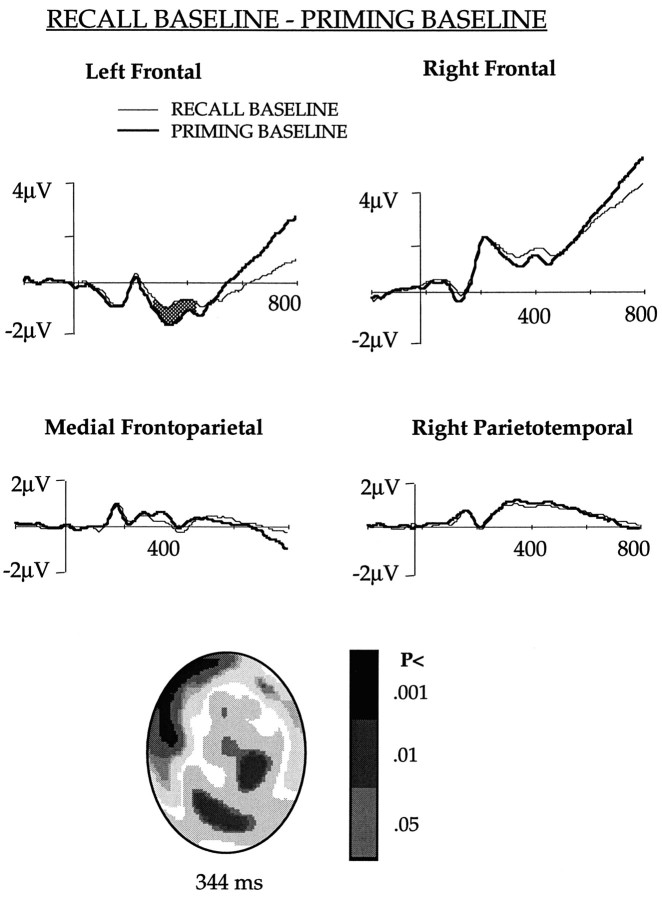

RECALL BASELINE and PRIMING BASELINE comparison (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4.

The ERPs obtained in the RECALL BASELINE and PRIMING BASELINE conditions after collapsing potentials of the channels in the left and right frontal, medial frontoparietal, and right parietotemporal regions shown in Figure 1. The waveforms differed significantly (p < 0.01) in theshaded area. The figure also shows an interpolated image of the significance of difference between the two conditions.

To understand the brain activations during explicit recall of unprimed words, ERPs evoked by the RECALL BASELINE and PRIMING BASELINE tasks were compared. This comparison indicated that unlike the RECALL and PRIMING comparison, frontal activation was unilateral. There was no significant difference in the right frontal ERP, and the difference in the left frontal channels was similar to that observed in the RECALL and PRIMING comparison. Potentials were less negative in the RECALL BASELINE than in the PRIMING BASELINE between 260 and 440 msec. Mean amplitude during this period was −0.96 and −1.78 μV for the RECALL BASELINE and PRIMING BASELINE, respectively.

Interestingly, right parietotemporal channels that differed at different time windows in the PRIMING and PRIMING BASELINE and the RECALL and PRIMING comparisons did not show any difference in the RECALL BASELINE and PRIMING BASELINE comparison. The ERPs in the medial frontoparietal channels were also similar in the two baseline conditions.

Interpolated images showing statistical difference between the ERPs in the RECALL BASELINE and PRIMING BASELINE tasks after 344 msec of stem presentation are shown in Figure 4.

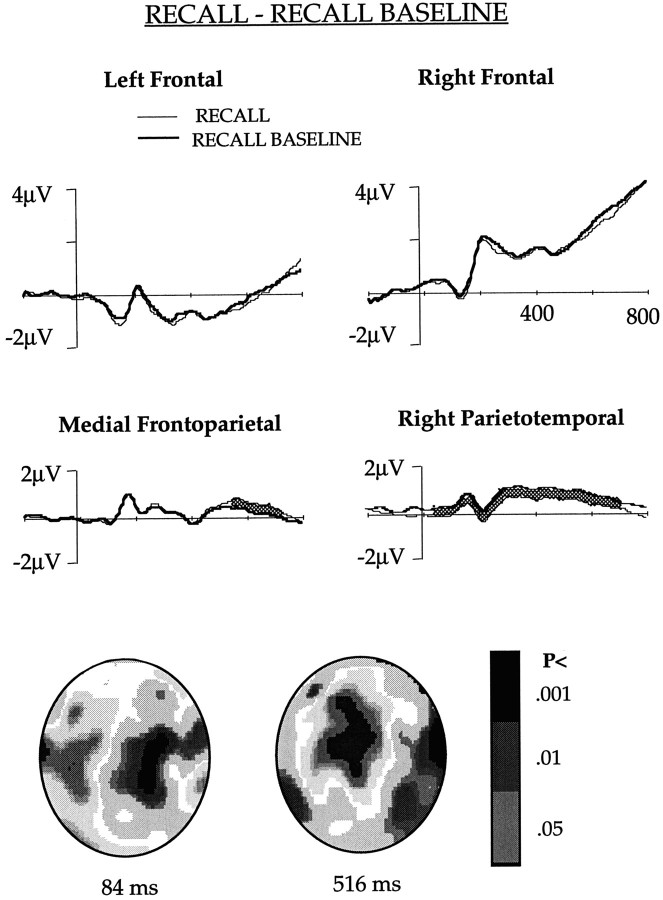

RECALL and RECALL BASELINE comparison (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5.

The ERPs obtained in the RECALL and RECALL BASELINE conditions after collapsing potentials of the channels in the left and right frontal, medial frontoparietal, and right parietotemporal regions shown in Figure 1. The waveforms differed significantly (p < 0.01) in theshaded area. The figure also shows an interpolated image of the significance of difference between the two conditions.

Comparison of the ERPs elicited in the two explicit memory conditions did not show any difference in frontal channels, indicating that frontal activity was similar during explicit retrieval of primed and unprimed words. Right parietotemporal channels that elicited less positivity in the PRIMING and PRIMING BASELINE comparison in the early phase (60–200 msec) and in the RECALL and PRIMING comparison in the late phase (220–496 msec) showed lower potential for the RECALL as compared with the RECALL BASELINE, at both the early and the late phases. Mean potential in the early phase was 0.46 μV in the RECALL BASELINE and 0.08 μV in RECALL. It was 1.15 and 0.72 μV, respectively, in the RECALL BASELINE and RECALL in the late phase. Because the attenuation in the early phase was observed in both the PRIMING and the RECALL conditions, and both tasks required recall of the primed words, this effect may be associated with the retrieval of primed words. This finding supports the idea that storage of the previously studied word involves right posterior areas, and this storage is activated automatically irrespective of the instruction. In the medial frontoparietal channels, the RECALL ERP was significantly more positive than RECALL BASELINE ERP between 566 and 732 msec. Mean potential during this period was 0.55 and 0.16 μV for the RECALL and RECALL BASELINE, respectively. This difference was similar to that observed in the PRIMING and PRIMING BASELINE comparison, but it was 166 msec later in the RECALL and RECALL BASELINE subtraction.

Interpolated images showing statistical difference between the ERPs in the RECALL and RECALL BASELINE after 84 and 516 msec of stem presentation are shown in Figure 5.

In phase 3, eight subjects participated in the explicit memory blocks only. The idea of introducing this phase was to see whether the brain activations were similar when explicit memory blocks were not preceded by implicit memory blocks. Grand averaged ERPs of these subjects were essentially the same as those obtained in the RECALL and RECALL BASELINE conditions of phases 1 and 2. Comparison of the RECALL and RECALL BASELINE ERPs revealed similar differences in the medial frontoparietal and right parietotemporal channels observed in the grand averaged ERP of 40 subjects who participated in phases 1 and 2.

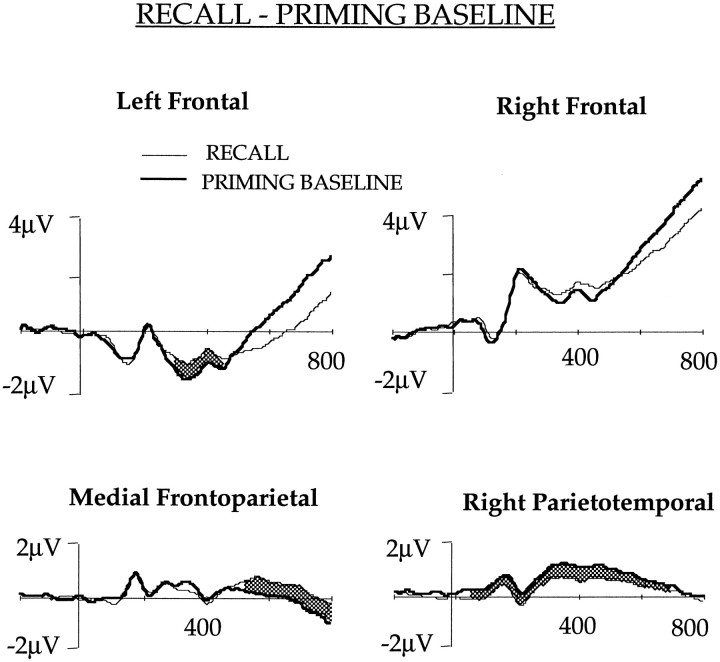

RECALL and PRIMING BASELINE comparison (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6.

The ERPs obtained in the RECALL and PRIMING BASELINE conditions after collapsing potentials of the channels in the left and right frontal, medial frontoparietal, and right parietotemporal regions shown in Figure 1. The waveforms differed significantly (p < 0.01) in theshaded area.

This comparison revealed significant left frontal activation in the RECALL task. The difference was statistically significant between 288 and 448 msec, and the mean potentials during this time window were −1.12 and −1.45 μV, respectively, for the RECALL and PRIMING BASELINE. The difference was similar to that observed in the RECALL and PRIMING comparison, indicating that left frontal activity was not altered by priming.

Medial frontoparietal channels evoked an effect that was similar to the effect observed in the PRIMING and PRIMING BASELINE and the RECALL and RECALL BASELINE comparisons. In these channels, RECALL ERP was more positive than the PRIMING BASELINE ERP after 512 msec of stem presentation. Potentials in the right parietotemporal channels differed in both the early (60–200 msec) and the late phases (220–496 msec), with the RECALL task showing greater positivity.

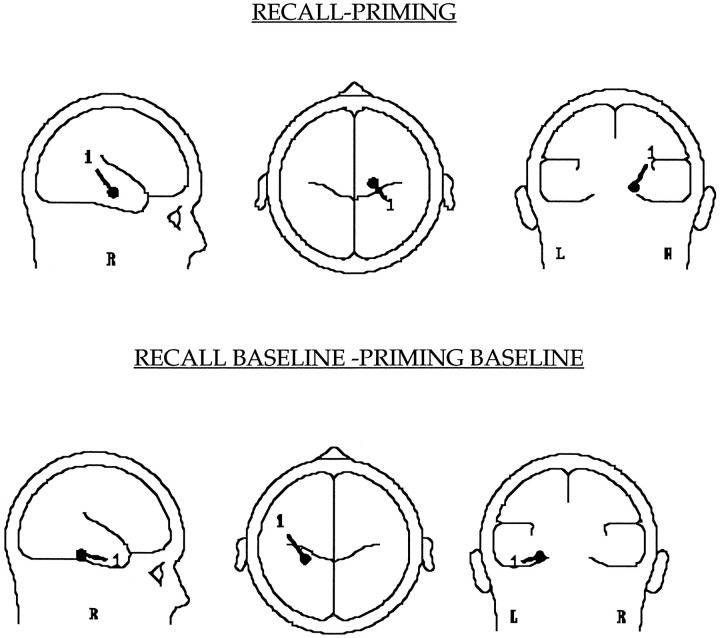

Dipole source localization

Difference waves between the RECALL and PRIMING ERPs were analyzed using the BESA algorithm (Scherg and Berg, 1995) to determine topography of the best-fitting dipoles (Fig. 7). This subtraction essentially revealed the brain activations required for explicit recall of recently studied words when there was a possibility of successful retrieval. A single-source dipole localized deep in the right hemisphere was responsible for 84% of neural activity between 165 and 215 msec of stem presentation.

Fig. 7.

Location of the best-fit dipole (generated using BESA) in the difference wave obtained after the RECALL and PRIMING (135–165 msec) and the RECALL BASELINE and PRIMING BASELINE subtractions.

The difference wave between the RECALL BASELINE and PRIMING BASELINE conditions represented the brain activations involved in the explicit recall effort, where there was no possibility of successful retrieval from the previously studied list. In this condition, a single source of dipole was responsible for 83.6% of activity between 234 and 284 msec (Fig. 8) after stimulus presentation. This dipole was localized deep inside the left hemisphere.

Although precise localization of the dipoles responsible for generating scalp potentials is difficult in terms of the involved brain areas, location of the dipoles when combined with the information obtained from the imaging studies having better spatial resolution provides clues about the brain areas involved. Topography of the dipoles (x = 18.3, y = −8.0, z= −24; and x = −28.0, y = −26.0,z = −22.0 mm) interpreted in light of the PET studies (Squire et al., 1992; Kapur N. et al., 1995; Schacter et al., 1996) that have reported hippocampal activations under explicit recall conditions suggests that the dipole sources were located in the right (PRIMING − RECALL) and the left (RECALL BASELINE − PRIMING BASELINE) hippocampal regions.

Analysis of the difference waves generated after the PRIMING − PRIMING BASELINE and the RECALL − RECALL BASELINE subtractions did not reveal any strong source of dipole in the 1 sec epoch.

DISCUSSION

Implicit retrieval

When subjects receive a stem from an item in a memorized list and are asked to say the first word that comes to mind beginning with the stem, there is a reduction of right posterior electrical activity during the first 200 msec after stem input in comparison to control items for which no appropriate word had been presented. This result confirms earlier PET work demonstrating reduced right posterior activation for primed words (Squire et al., 1992; Buckner et al., 1995;Schacter et al., 1996) and also suggests that information stored in the right posterior brain is contacted by the string within the first 200 msec of input.

As a result of a successful match, the frontal operations involved in retrieving candidate words do not occur. Thus, primed words under implicit instruction show reduced right frontal electrical activity after 250 msec. This view of priming as an early automatic influence of the stored words is confirmed when one compares the RECALL to RECALL BASELINE. RECALL also involves influence from earlier learning, because the word was presented previously, but now a successful match is not sufficient, because the subject must also know explicitly that the word comes from the previous list. Thus, in this subtraction, there is a right posterior attenuation indicative of priming, but both the RECALL and the RECALL BASELINE conditions also activate equivalent bilateral frontal search systems.

It appears that the explicit and implicit retrieval processes for primed words share common computations in the right posterior cortex. However, there was also attenuation of the right frontal potentials in the PRIMING task compared with the PRIMING BASELINE. An earlier PET study (Buckner et al., 1995) also found reduced blood flow in the right frontal area for primed items, but the difference was not significant statistically. It appears that the activation of the frontal cortex is not required for implicit recall of primed words (Schacter et al., 1996), but it becomes involved when additional search operations are required, either because there is no priming by previous learning or because the instructions require search of the stored information.

Explicit retrieval

What activity is involved in explicit retrieval? A major result of this study is that explicit retrieval creates a pattern of frontal brain activity that is not present for implicit priming. The frontal activity begins by 250 msec. However, the activity in the frontal and hippocampal region is complex and highly overlapping in time. It will clearly require additional studies to sort out their function and time course.

There are many conditions that produce explicit retrieval. When the instruction is to say the first word that comes to mind, but the response has not been primed, only right frontal activation was found. In this case, there is little competition between retrieved items, because all words that start with the string are appropriate.

However, when instructed to recall a specific item from the previously memorized list, there is likely to be competition between items, and subjects must take the additional step of checking any candidate with the stored list. This process requires ∼200 msec and is associated with left frontal activity. Our results, then, suggest activation of the left frontal cortex in the tasks that require explicit effort to search for the appropriate word from the previously studied list and right frontal activation in the tasks associated with the conditions in which any word starting with the string is correct.

A review of earlier imaging studies suggests that when a task requires explicit search effort, there is activation of the left frontal cortex. Thus, search for an appropriate use for a noun (Petersen et al., 1988;Raichle et al., 1994) or for a semantic relation (Demb et al., 1995) or for words in the study list (Buckner et al., 1995; Schacter et al., 1996) all produced left frontal activation. Conditions requiring simple associations after extensive practice with a list and thus without competition can produce right frontal activity (Snyder et al., 1995), as can retrieval of a previously studied picture (Tulving et al., 1994;Tulving and Pearlstone, 1996) or a face–name association (Haxby et al., 1996).

Results from imaging studies have shown activation of the hippocampus in memory and recall tasks (Squire et al., 1992; Kapur N. et al., 1995;Schacter et al., 1996). However, a precise definition of what activates either right or left hippocampus is still unclear. In our experiments, we found evidence of activation in the hippocampal region only in explicit recall, which is consistent with the findings of recent PET experiments in which increased blood flow was observed in the area of the hippocampus in tasks of explicit memory (Squire et al., 1992;Schacter et al., 1996), but not in implicit memory tests (Schacter et al., 1996). Activation in the hippocampal region overlapped the time course of frontal activity, as discussed above.

We found evidence of activity in the right hippocampal region when words had been studied and subjects were successful in recalling them. This result is consistent with the view that the right hippocampus is involved in short-term retrieval (Squire, 1992; Frackowiak, 1994) but also supports the idea that the right hippocampal region reflects successful retrieval. In contrast, activation in the left hippocampal region was found under conditions when subjects searched unsuccessfully for an appropriate studied item such as in the RECALL BASELINE where no item in the previously studied list fit the string. The association of activity in the right hippocampal region with successful retrieval of a stored word fits with the PET findings that indicate that successful retrieval is associated with the activation of posterior cortical regions (Kapur S. et al., 1995) and that the subtraction of low recall from high-recall conditions leads to activity in the right hippocampal formation (Schacter et al., 1996).

Output

A midfrontoparietal area showed activation after 400 msec whenever a relatively fast response condition (PRIMING, RECALL) was compared with a slower response condition (PRIMING BASELINE, RECALL BASELINE). We conclude that this area has more to do with preparing the candidate word for output. The scalp distribution of this activation, centered over frontoparietal electrodes, fits with other data from our laboratory suggesting a relationship of this area to phonological coding of words (Posner et al., 1997).

Circuitry

Consider successful retrieval of a previously stored word under explicit instructions. According to our results, the input string makes contact with the previously stored words in the right posterior cortex within the first 200 msec of input. This occurs automatically under both implicit and explicit instructions. In the case of implicit instructions, priming is sufficient to generate a response so that no additional search occurs. However, for explicit retrieval, priming is not sufficient to make the response, because subjects need to verify explicitly that this word was on the previously studied list. Thus, under this condition, frontal activity is initiated ∼250 msec after input. The search for an explicit response potentially involves several overlapping mechanisms, and we are suggesting only some of them. Because in the case of explicit recall, only some of the retrieved words are acceptable (those from the studied list), bilateral frontal activity is found, and during the same period (250–600 msec), there is attenuation of the right parietal activation. The hippocampal activation occurs during the same time interval, suggesting that retrieval of candidate words is a major part of the explicit recall task. Output processes involved in generation of a motor program for making the response appear over phonological areas starting at ∼400 msec and continuing to 800 msec. The actual verbal response output began as early as 1100 msec (mean response time, 1452 msec) in this condition. Thus, the convergence of PET and ERP data begins to reveal the complex organization of computations needed to perform this word-retrieval task.

Footnotes

This research was supported by Office of Naval Research Grant N00014-96-0273, grants from the J. S. McDonnell and Pew Memorial Trusts, and the W. M. Keck Foundation to the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience of Attention at the University of Oregon. We are grateful to Bruce McCandliss for his help.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Rajendra D. Badgaiyan, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, 3811 O’Hara Street, Suite E-533, Pittsburgh, PA 15213.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdullaev YG, Posner MI. Time course of activating brain areas in generating verbal associations. Psychol Sci. 1997;8:56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badgaiyan RD, Posner MI (1996a) Priming of the human brain. Cognitive Neuroscience Society (Abstr) p57.

- 3.Badgaiyan RD, Posner MI. Priming reduces input activity in right posterior cortex during stem completion. NeuroReport. 1996b;7:2975–2978. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199611250-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckner RL, Petersen SE, Ojemann JG, Miezin FM, Squire LR, Raichle ME. Functional anatomical studies of explicit and implicit memory retrieval tasks. J Neurosci. 1995;15:12–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00012.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demb JB, Desmond JE, Wagner AD, Vaidya CJ, Glover GH, Gabrieli JDE. Semantic encoding and retrieval in the left inferior prefrontal cortex: a functional MRI study of task difficulty and process specificity. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5870–5878. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-05870.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frackowiak RSJ. Functional mapping of verbal memory and language. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:109–115. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graf P, Schacter DL. Implicit and explicit memory for new associations in normal and amnesic subjects. J Exp Psychol Learn Memory Cogn. 1985;11:501–518. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.11.3.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haxby JV, Ungerleider LG, Horwitz B, Maisog JM, Rapoport SL, Grady CL. Face encoding and recognition in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:922–927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapur N, Friston KJ, Young A, Frith CD, Frackowiak RS. Activation of human hippocampal formation during memory for faces: a PET study. Cortex. 1995;31:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapur S, Craik FI, Jones C, Brown GM, Houle S, Tulving E. Functional role of the prefrontal cortex in retrieval of memories: a PET study. NeuroReport. 1995;6:1880–1884. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199510020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nyberg L, Cabeza R, Tulving E. PET studies of encoding and retrieval: the HERA model. Psychonomic Bull Rev. 1996;3:135–148. doi: 10.3758/BF03212412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersen SE, Fox PT, Posner MI, Mintun M, Raichle ME. Positron emission tomography studies of the cortical anatomy of single-word processing. Nature. 1988;331:585–589. doi: 10.1038/331585a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Posner MI, Abdullaev YG, McCandliss BD, Sereno S. Anatomy, circuitry and plasticity of word reading. In: Everatt J, editor. Visual and attentional processes in reading and dyslexia. Routledge; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raczkowski D, Kalatm JW, Nebes R. Reliability and validity of some right handed questionnaire items. Neuropsychology. 1974;6:43–47. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(74)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raichle ME, Fiez JA, Videen TO, MacLeod A-MK, Pardo JV, Fox PT, Petersen SE. Practice-related changes in human brain functional anatomy during nonmotor learning. Cereb Cortex. 1994;4:8–26. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schacter DL, Peter-Chieu C-Y, Ochsner KN. Implicit memory: a selective review. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1993;16:159–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schacter DL, Alpert NM, Savage CR, Rauch SL, Albert MS. Conscious recollection and the human hippocampal formation: evidence from positron emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:321–325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scherg M, Berg P. Brain electric source analysis handbook. Neuroscan; Herndon, VA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snyder A, Abdullaev YG, Posner MI, Raichle ME. Scalp electrical potentials reflect regional cerebral blood flow responses during processing of written words. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1689–1693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Squire LR. Memory and the hippocampus: a synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys, and humans. Psychol Rev. 1992;99:195–231. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Squire LR, Ojemann JG, Miezin FM, Petersen SE, Videen TO, Raichle ME. Activation of the hippocampus in normal humans: a functional anatomical study of memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1837–1841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tucker DM, Liotti M, Potts GF, Russell GS, Posner MI. Spatiotemporal analysis of brain electrical fields. Hum Brain Mapp. 1994;1:134–152. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tulving E, Pearlstone Z. Availability versus accessibility of information in memory for words. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav. 1996;5:381–391. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tulving E, Schacter DL. Priming and human memory systems. Science. 1990;247:301–306. doi: 10.1126/science.2296719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tulving E, Markowitsch HJ, Kapur S, Habib R, Houle S. Novelty encoding networks in the human brain: positron emission tomography data. NeuroReport. 1994;5:525–536. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]