Abstract

Cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels in vertebrate photoreceptors are crucial for transducing light-induced changes in cGMP concentration into electrical signals. In this study, we show that both native and exogenously expressed CNG channels from rods are modulated by tyrosine phosphorylation. The cGMP sensitivity of CNG channels, composed of rod α-subunits expressed in Xenopus oocytes, gradually increases after excision of inside-out patches from the oocyte membrane. This increase in sensitivity is inhibited by a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) inhibitor and is unaffected by three different Ser/Thr phosphatase inhibitors. Moreover, it is suppressed or reversed by application of ATP but not by a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog. Application of protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) inhibitors causes an increase in cGMP sensitivity, but only in the presence of ATP. Taken together, these results suggest that CNG channels expressed in oocytes are associated with active PTK(s) and PTP(s) that regulate their cGMP sensitivity by changing phosphorylation state. The cGMP sensitivity of native CNG channels from salamander rod outer segments also increases and decreases after incubation with inhibitors of PTP(s) and PTK(s), respectively. These results suggest that rod CNG channels are modulated by tyrosine phosphorylation, which may function as a novel mechanism for regulating the sensitivity of rods to light.

Keywords: cGMP, rod outer segment, photoreceptor, phototransduction, tyrosine, protein kinase, protein phosphatase, phosphorylation

Cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels are crucial for generating electrical signals during phototransduction in vertebrate photoreceptors. Light triggers a decrease in the cytoplasmic concentration of cGMP, causing CNG channels in the plasma membrane to close. The sensitivity of CNG channels to cGMP can be modulated by several intracellular constituents, with important physiological consequences. Intracellular Ca2+ causes a decrease in cGMP sensitivity of rod CNG channels, mediated by direct binding of calmodulin and other Ca2+-binding proteins to the CNG channel protein (Hsu and Molday, 1993; Gordon et al., 1995a; Nakatani et al., 1995). The intracellular concentration of Ca2+ decreases in the rod outer segment during the light response, leading to an increase in the cGMP sensitivity of CNG channels, possibly contributing to light adaptation. Rod CNG channels are also modulated by transition metals (Zn2+ and Ni2+), which increase cGMP sensitivity (Ildefonse et al., 1992; Karpen et al., 1993), and diacylglycerol, which inhibits the channels (Gordon et al., 1995b).

The cGMP sensitivity of rod CNG channels is also modulated by protein phosphorylation. Gordon et al. (1992) showed that CNG channels in inside-out patches from rod outer segments exhibit a gradual increase in sensitivity after patch excision. This increase in cGMP sensitivity is Ca2+-dependent and is blocked by specific Ser/Thr phosphatase inhibitors. Exogenous applica-tion of Ser/Thr phosphatases (phosphatases 1 and 2A) reinstates changes in cGMP sensitivity after exposure to EGTA to remove Ca2+. These results suggest that CNG channels, like many other ion channels, are modulated by Ser/Thr phosphorylation.

Recent studies reveal that ion channels can also be modulated by tyrosine phosphorylation (for review, see Siegelbaum, 1994). Protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) and protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) are functionally associated with voltage-gated (Huang et al., 1993; Wilson and Kaczmarek, 1993; Prevarskaya et al., 1995; Xiong and Cheung, 1995;Holmes et al., 1996a; Aniksztejn et al., 1997) and ligand-gated channels (Swore and Huganir, 1993; Moss et al., 1995; Wang et al., 1996). Receptor PTKs, such as prolactin (Prevarskaya et al., 1995) and insulin (Jonas et al., 1996) receptors, regulate ion channel activity, but constitutively active nonreceptor PTKs, such as v-Src, also have profound effects on certain channels (Moss et al., 1995; Holmes et al., 1996b; Yu et al., 1997). Typical agonists that interact with receptor PTKs and PTPs include polypeptide hormones and growth factors, which affect slow processes such as cell differentiation and growth. Modulation of channels by PTKs or PTPs can occur in seconds, suggesting that ion channel regulation may be an early physiological event occurring in response to growth factor activation of PTKs or PTPs.

In this paper, we show that tyrosine phosphorylation is a novel mechanism for modulating rod CNG channels. Rod CNG channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes are associated with active PTK(s) and PTP(s), with phosphorylation or dephosphorylation, respectively, decreasing or increasing their cGMP sensitivity. Moreover, native CNG channels in salamander rod outer segments are also modulated by PTKs and PTPs intrinsic to the retina. We propose that modulation of CNG channels by tyrosine phosphorylation is an important mechanism for controlling the light sensitivity of rods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and recording from oocyte CNG channels. A cDNA clone encoding the bovine rod photoreceptor CNG channel α-subunit (Kaupp et al., 1989) was used for in vitrotranscription of mRNA, as described previously (Goulding et al., 1992), which was injected into Xenopus oocytes (50 nl/oocyte at 1 ng/nl). After 2–7 d, the vitelline membrane was removed from injected oocytes, which were then placed in a chamber for patch-clamp recording at 21–24°C. Glass patch pipettes (2–3 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing 115 mm NaCl, 5 mm EGTA, and 10 mm HEPES, pH-adjusted to 7.5 with NaOH. This also served as the standard bath solution and cGMP perfusion solution unless noted otherwise. After formation of a gigaohm seal, inside-out patches were excised and the patch pipette was quickly (<30 sec) placed in the outlet of a 1-mm-diameter tube for cGMP application. We used a perfusion manifold containing up to 15 different solutions that is capable of solution changes within 100 msec. A series of four to five cGMP concentrations (10–2000 μm cGMP) was applied to the patch. Application of the series required 20–30 sec and was repeated at 1 min intervals. ATP (Mg salt) was applied at 200 μmand either was present in all solutions and applied continuously (e.g., see Figs. 6, 7) or was applied transiently for 3 min starting 10.5 min after patch excision (e.g., see Figs. 4, 5). Phosphatase and kinase inhibitors were prepared as concentrated stock solutions in water or DMSO, and aqueous solutions containing the final concentrations were prepared for use as needed. The final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1%, which had no effect on CNG channels or their modulation. Sodium pervanadate was prepared as described previously (Wallace, 1995). cGMP, ATP, AMP-PNP, and ATP-γ-S, microcystin-LR, and staurosporine were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), K252a was obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA), and okadaic acid, calyculin A, lavendustin A and B, and erbstatin (stable analog) were obtained from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA).

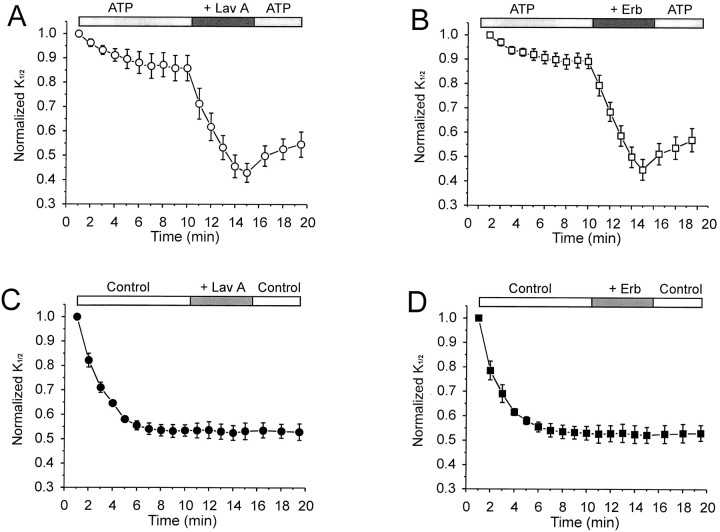

Fig. 6.

Effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on CNG channel modulation in oocytes. A, Effect of 10 μm lavendustin A (Lav A).B, Effect of 25 μm erbstatin (Erb) analog on the K1/2 for cGMP activation, both in the presence of continuously appliedATP (200 μm). C, Lack of an effect of lavendustin A. D, Lack of an effect of erbstatin analog, both in the absence of ATP (n = 5–7 patches for each condition).

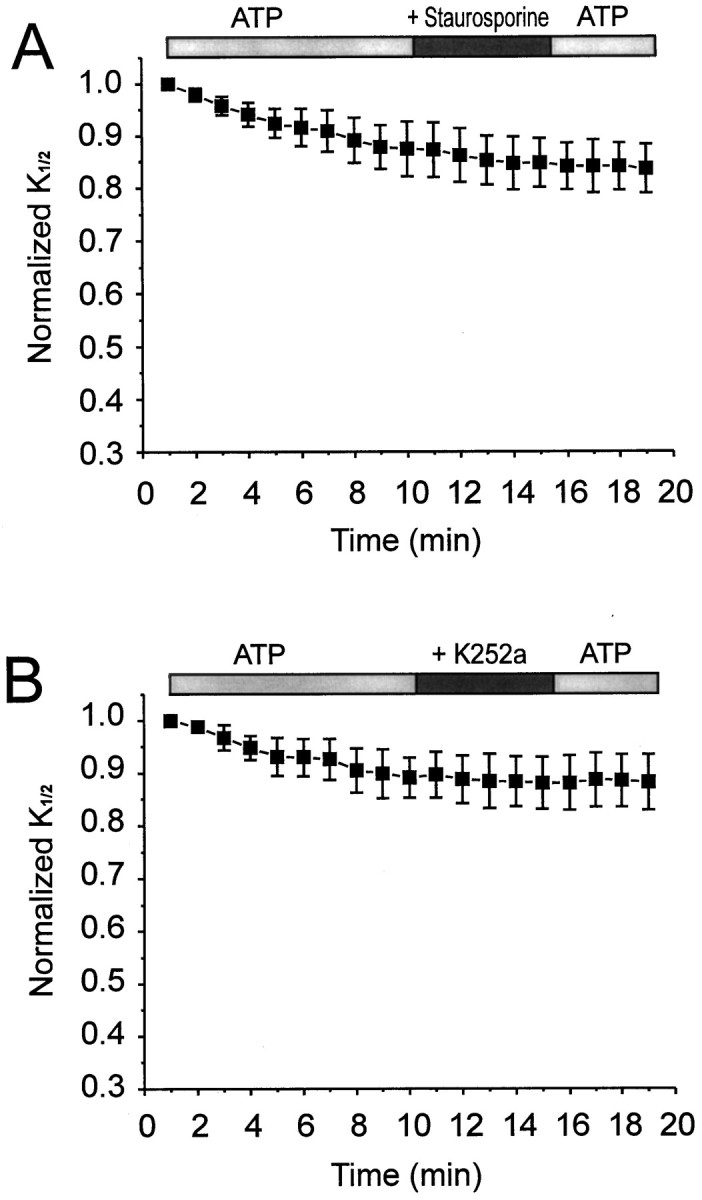

Fig. 7.

Effects of Ser/Thr kinases inhibitors on CNG channel modulation in oocytes. A, Application of staurosporine (100 nm; n = 7).B, Application of K252a (500 nm;n = 11). Both inhibitors were used in the presence of continuously applied ATP (200 μm).

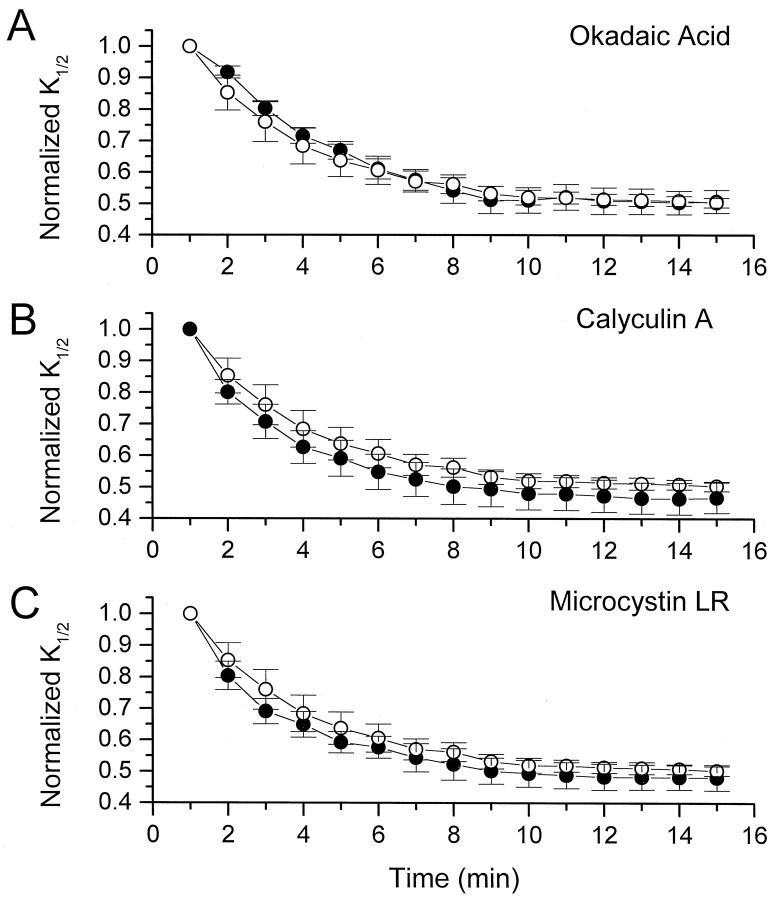

Fig. 4.

Effects of continuous exposure to Ser/Thr phosphatase inhibitors on the change in K1/2in oocyte patches. A, Effect of 250 nmokadaic acid (n = 7). B, Effect of 10 nm calyculin (n = 6).C, Effect of 500 nm microcystin-LR (n = 6). Changes in K1/2for each inhibitor (filled circles) are plotted along with changes in K1/2 in control solution (open circles; n = 6). All data are normalized to the initial K1/2(t = 1 min).

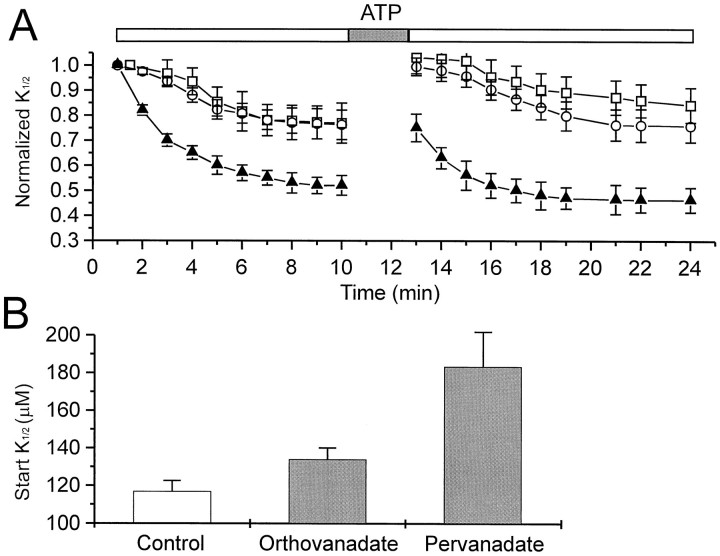

Fig. 5.

Effects of the tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor vanadate on modulation of CNG channels from oocytes. A, Effect of continuous exposure to 200 μm orthovanadate (open circles; n = 11), 100 μm pervanadate (open squares;n = 5), or neither (filled triangles; n = 34) on changes inK1/2 after patch excision and ATP exposure.B, Effect of pretreatment of intact oocytes (1 hr) with control saline, 200 μm orthovanadate, or 100 μm pervanadate on the initialK1/2 measured 1 min after patch excision (n = 47, 16, and 7, respectively).

Current responses through CNG channels were obtained with an Axopatch 200A patch clamp (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), digitized, stored, and later analyzed on a 486 PC using pClamp 6.0 software. Membrane potential was held at −75 mV in all experiments. Current responses were normalized to the maximal CNG current (Imax), which was elicited by saturating cGMP (2 mm). Normalized dose–response curves were fit to the Hill equation: I/Imax = 1/(1 + (K1/2/A)n), where A is the cGMP concentration and n is the Hill coefficient, using a nonlinear least-squares fitting routine (Origin, Microcal Software). Changes in cGMP sensitivity in the presence of drugs were plotted together with matched control results from the same batches of oocytes (i.e., see Figs. 3, 4, 5). Variability among measurements is expressed as mean ± SEM.

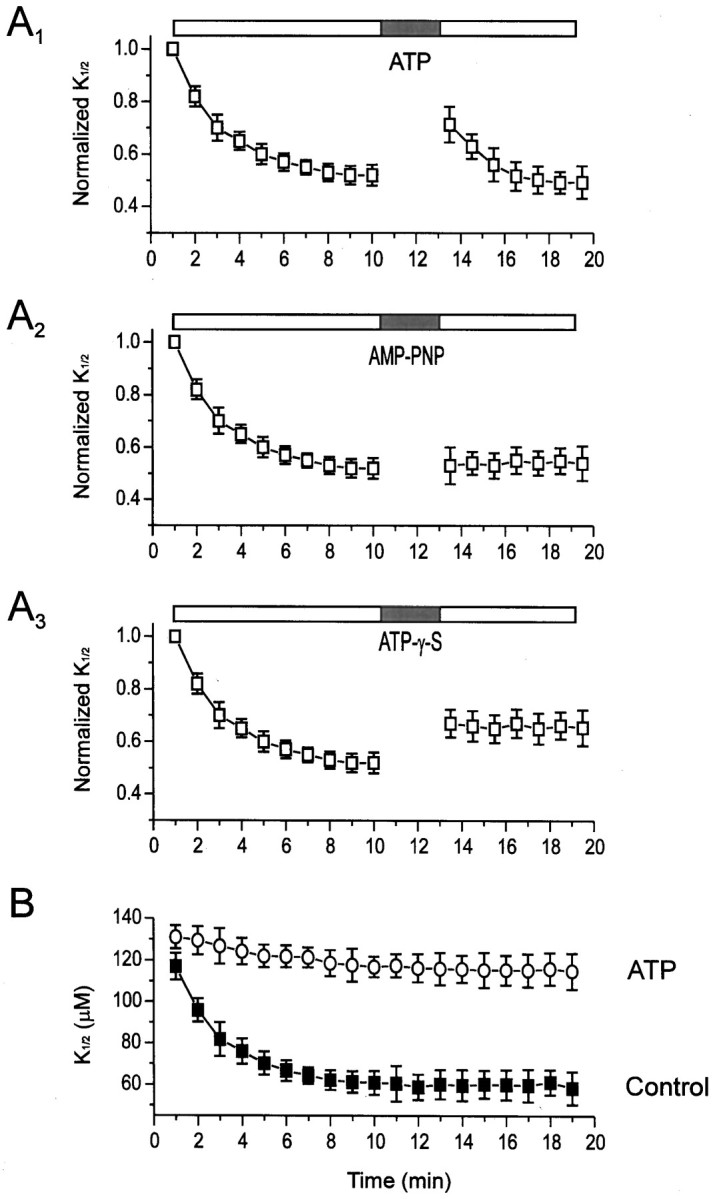

Fig. 3.

The effects of ATP and its analogs on the time course of the changes of K1/2.A, Changes in K1/2 after patch excision and application of ATP (A1), AMP-PNP (A2), and ATP-γ-S (A3). Each was applied at a concentration of 200 μm for 3 min. For each patch,K1/2 data were normalized to the value generated from the first dose–response curve after excision (1 min). Symbols represent mean ± SEM for all patches tested (n = 34, 13, and 16 patches forA1, A2, andA3, respectively). Horizontal bars on this and subsequent figures show time of drug application. B, Changes inK1/2 in patches with (open circles; n = 20 patches) and without (filled squares; n = 58 patches) continual exposure to 200 μm ATP from the moment of excision.

Recording from CNG channels from rod outer segments.Water-phase tiger salamanders (Ambystoma tigranum) maintained in a temperature-controlled aquarium (16°C) on a 12 hr light/dark cycle were used in all experiments at the same time of day. Animals were dark-adapted for 1 hr and anesthetized in an ice-cold solution containing 1 gm/l 2-amino benzoic acid for 20 min before decapitation and removal of eyes under dim red light. Eyes were placed in saline containing (in mm): 155 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.5. A fine Hamilton syringe was used to inject 50 μl of control saline, saline containing 200 μm lavendustin A or B, or saline containing 100 μm Na-pervanadate. After a 2 hr incubation in the dark, retinas were removed under dim illumination and placed in 1 ml of the same saline used for injection for an additional 2 hr in the dark. Finally, after a total of 4 hr of treatment, the retinas were cut into quarters and gently triturated to obtain rod outer segments, which were placed in a recording chamber in the same solution used for eye injection. Borosilicate glass pipettes (3–5 MΩ) were filled with standard patch solution (see oocyte section above) and were used to obtain excised inside-out patches from the outer segment. The standard patch solution containing four to five concentrations of cGMP (2–1000 μm) was applied to excised patches immediately (0.5–1.0 min) after excision.

RESULTS

This study started with the observation that rod CNG channels in excised patches from Xenopus oocytes gradually increase their sensitivity to cGMP after a patch is excised from the cell. Homomeric CNG channels were expressed in oocytes by injecting mRNA encoding the α-subunit of the bovine rod CNG channel (Kaupp et al., 1991). The native rod CNG channel is heteromeric, containing both α- and β-subunits (Chen et al., 1993; Koerschen et al., 1995), but expression of α-subunits alone is sufficient for formation of functional CNG channels. Although these homomeric channels have somewhat different kinetic and pharmacological properties than the native channels, they exhibit many similarities, including similar conductance and permeation properties, cyclic nucleotide selectivity, and modulatability by transition metals (for review, see Zagotta and Siegelbaum, 1996).

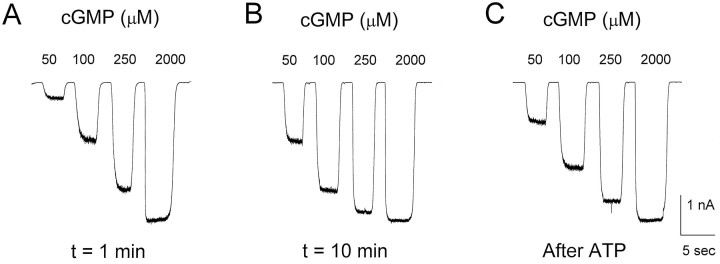

After obtaining an excised patch containing homomeric CNG channels, various concentrations (10–2000 μm) of cGMP were applied repeatedly at 1–2 min intervals. Figures1 and 2show changes in cGMP sensitivity of CNG channels from one representative patch. Current responses to subsaturating cGMP concentrations (e.g., 10–250 μm) increased during the first 10 min after excision, whereas the response to saturating cGMP (2000 μm cGMP) did not change (Fig.1A,B). After 10 min, the cytoplasmic side of the patch was exposed to 200 μm ATP for 3 min. Then the ATP was washed away and cGMP responses were elicited again. The transient exposure to ATP led to a decrease in the response to subsaturating cGMP concentrations without affecting the saturating response (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Modulation of current through CNG channels in an excised patch from a Xenopus oocyte. Currents were elicited by application of cGMP at concentrations of 50, 100, 250, and 2000 μm 1 and 10 min after excision, and after a 3 min application of 200 μm ATP (13.5 min after excision).

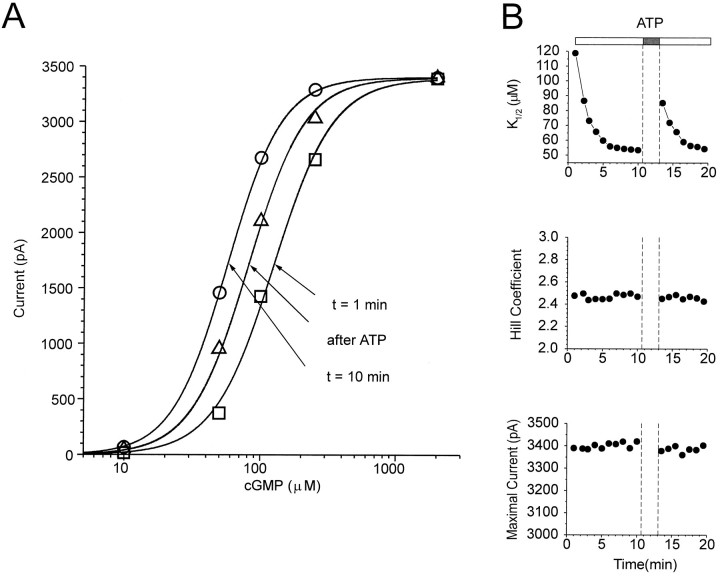

Fig. 2.

Change in cGMP sensitivity of CNG channels in an excised patch from an oocyte. A, Dose–response curves of CNG channel activation by cGMP, with data taken from Figure 1.Solid curves show the fit to the Hill equation.B, Changes in K1/2, but not the Hill coefficient or maximal current, with time after patch excision and after ATP application. This figure shows an analysis of dose–response data from a single patch collected at 1 min intervals.

Dose–response curves show that less cGMP is required to activate the CNG channels 10 min after patch excision than 1 min after excision, whereas the maximal current does not change (Fig.2A). Transient ATP application leads to an opposite change, decreasing the cGMP sensitivity. To analyze these effects further, each of the repeated dose–response curves was fit with the Hill equation, and the free parameters (K1/2, Hill coefficient, and maximal current) were plotted over time. Figure 2B shows that the Hill coefficient and the maximal current did not change with time and were unaffected by ATP. However, the K1/2decreased from 119 to 54 μm over the first 10 min and then stabilized, exhibiting no further spontaneous changes. However, transient application of ATP caused theK1/2, measured immediately after ATP exposure, to increase to 85 μm. Subsequently, theK1/2 again decreased to 55 μm with a time constant (τ) of 1.7 min, similar to that observed for the decrease in K1/2 after excision (τ = 1.9 min). This suggests that the same process underlying the initial decrease inK1/2 also underlies the decrease inK1/2 after ATP exposure.

To investigate whether ATP is used as a substrate in a phosphorylation reaction, we compared its effects with those of two ATP analogs that differ from ATP in their ability to phosphorylate proteins. Data from multiple patches were normalized such that theK1/2 of the first dose–response curve after excision (1 min) was set to 1.0. Whereas transient application of ATP increased the K1/2 by ∼37% (Fig.3A1), application of the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog adenylyl-imidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP) had no effect (Fig. 3A2). Application of ATP-γ-S (adenosine-5′-O-(3′-thiotriphosphate) elicited a smaller increase in K1/2 than did ATP (∼27%), but its effect appeared to be irreversible (Fig.3A3). ATP-γ-S is a poor substrate for many protein kinases. However, most protein phosphatases cannot dephosphorylate thio-phosphorylated proteins; thus ATP-γ-S often results in irreversible responses caused by irreversible phosphorylation (Cassidy et al., 1979; Chen et al., 1992; Xiong and Cheung, 1995).

We also examined the effect of continuous application of ATP from the moment the patch was excised (Fig. 3B). Continuous exposure to ATP greatly reduced the spontaneous change inK1/2, such that 10 min after excision theK1/2 was 88% of the initialK1/2 compared with control patches (ATP-free), in which the K1/2 dropped to 52% after 10 min. Taken together with our ATP analog experiments, these results suggest that ATP is a substrate in a phosphorylation reaction that opposes or reverses the spontaneous decrease in K1/2.

We propose that the following scenario accounts for the changes in sensitivity of CNG in oocyte patches. The cGMP sensitivity of CNG channels (or a closely associated regulator protein) is modulated by phosphorylation, with cGMP sensitivity being low in the phosphorylated state and high in the dephosphorylated state. The oocyte patch contains active protein phosphatase(s) and protein kinase(s) that remain associated with the membrane after patch excision. In the absence of ATP, the kinase cannot catalyze phosphorylation; thus, the phosphatase dephosphorylates the channels within 10 min after excising the patch, increasing cGMP sensitivity. In the presence of ATP, both the kinase and the phosphatase are active, more closely maintaining the initial phosphorylation state. Thus, in the presence of ATP, the sensitivity of the CNG channels reflects a balance between phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, similar to the situation in the intact cell. In the following experiments, we use phosphatase and kinase inhibitors to test this hypothesis.

Effects of phosphatase inhibitors

To determine whether Ser/Thr dephosphorylation is involved in the increase in CNG channel sensitivity in oocyte patches, we applied three selective inhibitors of Ser/Thr phosphatases: okadaic acid, calyculin A, and microcystin-LR (Cohen, 1989; MacKintosh et al., 1990). Figure 4 shows that, for all three inhibitors, the decrease in K1/2 exhibited during the first 10 min after excision was not significantly different from the decrease that occurs in control patches without the inhibitors. These results strongly suggest that Ser/Thr dephosphorylation does not underlie the modulation of CNG channels in oocyte patches.

We next asked whether inhibitors selective for tyrosine phosphatases could inhibit the decrease in K1/2. Orthovanadate (Swarup et al., 1982) and pervanadate (Heffetz et al., 1990; Wallace, 1995) selectively inhibit tyrosine phosphatases without affecting Ser/Thr-specific phosphatases (Hunter, 1995). Incubation of patches in solutions containing either form of vanadate reduced the spontaneous decrease in K1/2 (Fig.5A). In control solution, theK1/2 declined by 48% in the fist 10 min; in solutions with vanadate, the decrease in K1/2was only 22%. The rise in K1/2 brought about by ATP was unaffected by vanadate. However, the subsequent decrease inK1/2 after ATP exposure, like the initial decrease in K1/2 after patch excision, was reduced by both orthovanadate and pervanadate. These results suggest that, in both cases, most of the decrease inK1/2 was attributable to the action of a tyrosine phosphatase. The incomplete inhibitory effect of vanadate on the change in cGMP sensitivity may result from incomplete inhibition of tyrosine phosphatase by saturating vanadate, as has been reported in enzyme assays performed in cell-free systems (Swarup et al., 1982).

To test whether such a phosphatase might regulate the sensitivity of CNG channels to cGMP in intact oocytes, cells were pretreated with 100 μm pervanadate, which is membrane-permeant, for 1 hr before obtaining an excised patch (Fig. 5B). Patches from pervanadate-treated oocytes had an initial K1/2(measured at 1 min after excision) of 184 ± 18 μm, significantly higher than that exhibited by untreated oocytes (117 ± 6 μm). Pretreatment with orthovanadate, which is not membrane-permeant, caused a small but significant increase inK1/2 to 134 ± 6 μm. However, this may result from the effect of orthovanadate during the first minute after excision, before the initial K1/2could be measured.

Effects of kinase inhibitors

To test whether the effect of ATP on the cGMP sensitivity of CNG channels is attributable to phosphorylation, we first used selective inhibitors of protein tyrosine kinases. Figure6, A and B, shows the effects of lavendustin A (Onoda et al., 1989) and erbstatin (Umezawa et al., 1990) on CNG channels in patches that were exposed continuously to ATP. Addition of either inhibitor resulted in a striking decrease in K1/2, which partly reversed after the inhibitor was removed. In contrast, lavendustin A and erbstatin had no effect when the inhibitors were applied to patches in the absence of ATP (Fig. 6C,D). The observation that lavendustin A and erbstatin only affectK1/2 in the presence of ATP suggests that these agents act specifically by inhibiting a protein kinase.

We also tested whether inhibitors of Ser/Thr kinase inhibitors affect the sensitivity of CNG channels to cGMP. Staurosporine, an inhibitor of several Ser/Thr kinases including protein kinase C and cAMP-dependent protein kinase (Ruegg and Burgess, 1989), had no effect on theK1/2 in the presence of ATP (Fig.7A). Likewise, K252a, a broad-spectrum Ser/Thr kinase inhibitor (Ruegg and Burgess, 1989) that also blocks some tyrosine kinases (Tapley et al., 1992), also had no effect on K1/2 in the presence of ATP (Fig.7B). Taken together with the effect of lavendustin A and erbstatin, these results strongly suggest that the effect of ATP on CNG-channel cGMP sensitivity is mediated by a PTK that is resistant to K252a.

Experiments on native rod CNG channels

Our experiments on rod CNG channels expressed in oocytes show that PTKs and PTPs in the oocyte membrane can modulate the channels. Are native CNG channels in rod outer segments also modulated by tyrosine phosphorylation? Unlike our findings with oocytes, spontaneous increases in cGMP affinity in CNG channels from rod outer segments fail to occur in very low-Ca2+ solutions (<10−7m) (Gordon et al., 1992). A distinct form of modulation, which is Ca2+-dependent and involves Ser/Thr dephosphorylation, occurs within minutes after patches are excised from rods. If tyrosine phosphorylation also modulates the native rod CNG channels, the enzymes that control tyrosine phosphorylation state might act over a much slower time course, or they may be inactive in excised patches.

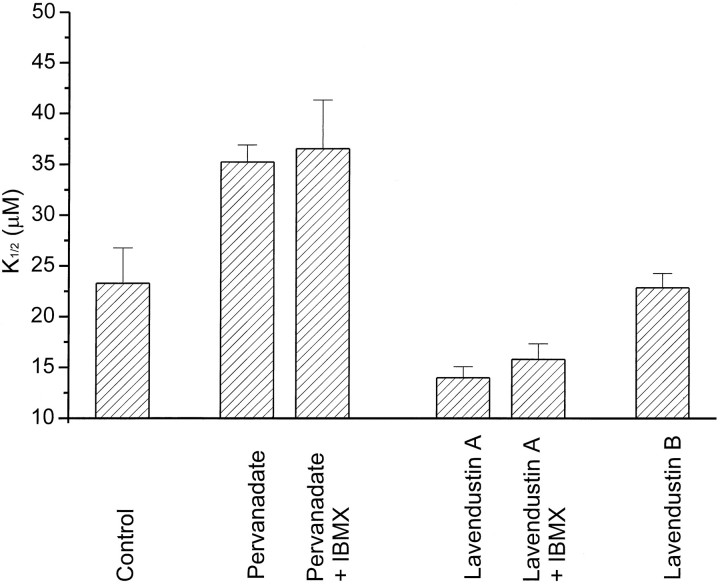

Therefore, to examine the possible effect of tyrosine phosphorylation of the native CNG channels, we applied tyrosine kinase or phosphatase inhibitors to intact rods for a longer time (3.5–4.0 hr). Eyes dissected from tiger salamanders (Ambystoma tigranum) were injected with 50 μl of a solution containing lavendustin A, lavendustin B (an inactive analog), pervanadate, or control saline. After 2 hr, retinas were removed and incubated for an additional 2 hr in the same solutions. Then outer segments were isolated and patch-clamp experiments were begun to obtain inside-out patches. Figure8 shows the initialK1/2 (1 min after excision) of CNG channels from each group of rods. Patches from lavendustin A-treated rods had CNG channels with a K1/2 of 14 ± 1 μm, whereas patches from pervanadate-treated rods had CNG channels with a K1/2 of 32 ± 2 μm, both significantly different (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively) than patches from control rods (K1/2 = 23 ± 2 μm). TheK1/2 of channels from lavendustin B-treated rods was 23 ± 1 μm, not significantly different from control.

Fig. 8.

Effects of PTK and PTP inhibitors on native CNG channels. K1/2 of cGMP activation was measured 1 min after excision of patches from rod outer segments from tiger salamander retina. Rods were exposed to control saline (n = 5), 100 μm pervanadate (n = 7), 10 μm lavendustin A (n = 7), or 10 μm lavendustin B (n = 4) for 3.5–4.0 hr before patch excision. cGMP test solutions were with or without added IBMX (100 μm) as indicated (n = 4 patches for each).

Patches excised from rod outer segments can retain elements of the phototransduction cascade, including rhodopsin, transducin, and cGMP phosphodiesterase (PDE) (Ertel, 1989). The apparent affinity of CNG channels in these patches can be underestimated because active PDE can reduce the concentration of cGMP reaching the channels (R. Kramer and S. Nawy, unpublished observations). To rule out the possibility that modulation of PDE activity, rather than modulation of CNG channels, underlies differences in the apparent affinity of rod CNG channels exposed to lavendustin A or pervanadate, the initialK1/2 was measured in some experiments in the presence of 100 μm isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX), which blocks PDE. Even with IBMX present, the lavendustin A-treated rods had CNG channels that were twice as sensitive to cGMP (K1/2 = 16 ± 2 μm) than CNG channels from pervanadate-treated rods (K1/2 = 37 ± 5 μm).

Thus, it appears that enhancing dephosphorylation by inhibiting tyrosine kinase results in channels with a high sensitivity to cGMP, whereas enhancing phosphorylation by inhibiting tyrosine phosphatase results in channels with a low sensitivity to cGMP. It should be noted that the magnitude and the direction of the change in apparent affinity brought about by phosphorylation are similar for CNG channels from rods and from oocytes; tyrosine phosphorylation results in an approximately twofold decrease in cGMP sensitivity.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that the cGMP sensitivity of rod CNG channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes is modulated by active PTKs and PTPs that remain associated with the channels in excised patches for many minutes after excision. The modulation of CNG channels may involve direct tyrosine phosphorylation of the channel protein(s), or it may be indirect, with tyrosine phosphorylation occurring on unidentified proteins that may be closely associated with CNG channels. Although this remains a possibility, there is a growing body of electrophysiological and biochemical evidence that suggests that signaling complexes containing closely associated kinases, phosphatases, and channels are common for many channels in many cell types (see Reinhart and Levitan, 1995). Moreover, PTKs and PTPs, specifically, have been shown to form functional complexes with many channels including Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Pevarskaya et al., 1995; Xiong and Cheung, 1995), voltage-gated K+ channels (Holmes et al., 1996a,b), and nonselective cation channels (Wilson and Kaczmarek, 1993; Aniksztejn et al., 1997). Indeed, several channels, including nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (Swope and Huganir, 1994; Fuhrer and Hall, 1996) and certain voltage-gated K+ channels (Holmes et al., 1996b), contain specialized amino acid sequences that bind to Src homology domains SH2 or SH3, characteristic sequences found in many PTKs and PTPs.

Do CNG channels contain specific sequences that mediate interactions with PTPs or PTKs? Recent studies of a specific K+channel (Kv1.5) have shown that it contains a proline-rich consensus sequence that mediates association with SH3 domains in the PTK v-Src (Holmes et al., 1996b). Prolines are rare in the α-subunit of the rod CNG channel (Kaupp et al., 1987), and the SH3 binding domain is missing. Therefore, if the α-subunit of the rod CNG channel is itself tyrosine-phosphorylated, PTKs distinct from v-Src are probably responsible. However, it is interesting to note that the β-subunit of the rod CNG channel (Koerschen et al., 1995) does contain several proline-rich regions in predicted cytoplasmic portions of the protein, and one of these bears a striking resemblance to the SH3 binding domain. Thus, it is possible that SH3 binding domains in native CNG channels are important for mediating interactions with PTKs or PTPs, perhaps including v-Src.

Our results show that transient ATP application only partially reverses the increase in cGMP sensitivity after excision of patches from oocytes (Fig. 3A1) and that continuous ATP application only partially suppresses the increase in sensitivity (Fig.3B). In addition, the cGMP sensitivity of CNG channels treated with tyrosine kinases inhibitors only partially recovers after these inhibitors are removed, even though ATP is present (Fig.6A,B). We propose that the following scenario accounts for the observed partial effects of ATP: After excision, the rate of phosphorylation is slower than that of dephosphorylation, such that a new equilibrium is reached, with a net decrease in phosphorylation, even in the presence of ATP. The change in phosphorylation/dephosphorylation rates after excision could result from wash-out, either of some regulatory factor of either the kinase or the phosphatase,or wash-out of the kinase itself. Because the kinase cannot keep up with the phosphatase, addition of ATP cannot restore the original sensitivity of the channel.

Modulation of native rod CNG channels is more complex than modulation of the expressed homomeric channels, with both Ser/Thr phosphorylation and tyrosine phosphorylation decreasing the sensitivity to cGMP. Ca2+-dependent Ser/Thr phosphatases increase the cGMP sensitivity of rod CNG channels in excised patches (Gordon et al., 1992), suggesting that these enzymes are active and have a sufficiently high enzymatic rate to dephosphorylate the channels within minutes after excision. Although our evidence establishes a role for regulation of rod channels by tyrosine phosphorylation, spontaneous changes in CNG channel sensitivity are not detected in excised rod patches in the presence of Ser/Thr phosphatase inhibitors (Gordon et al., 1992), and ATP application has no effect (our unpublished observations). This suggests that modulation by tyrosine phosphorylation either requires activators (intracellular or extracellular) that are not present in the excised patch or is too slow to be observed within the typical lifetime of an excised patch (tens of minutes). In these respects, the PTKs and PTPs in oocytes may be different from those in rods, because the oocyte enzymes act rapidly and do not require exogenous activators. It is possible that, although the specific PTPs and PTKs responsible for modulation may act over different time courses in oocytes and rods, both sets of enzymes may act on common phosphorylation sites to bring about an equivalent modulation of CNG channels. It should be noted that native rod patches may contain protein constituents that are absent from oocyte patches, including auxiliary subunits of CNG channels, adapter proteins, and cytoskeletal proteins. These proteins may add additional targets for tyrosine phosphorylation, which could influence the native CNG channels in an indirect manner.

The rate of decrease in K1/2 is accelerated when the channels are opened with cGMP. In addition, the decrease in cGMP sensitivity after ATP application can be prevented by opening the channels with saturating cGMP (E. Molokanova and R. H. Kramer, unpublished observations). Therefore, modulation mediated by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation is dependent on the open/closed state of the channel, strongly implying that modulation involves phosphorylation of the CNG channel itself. In particular, these observations suggest that either cGMP occupancy of its binding sites or the conformational change associated with channel opening (or both) alters the accessibility of the tyrosine phosphorylation site(s) to PTKs and PTPs. The conserved cyclic nucleotide binding domain of the α-subunit contains six tyrosines, and there are nine more in putative cytoplasmic domains. Ongoing experiments are aimed at determining whether the CNG channel itself is tyrosine-phosphorylated and, if so, identifying the specific tyrosine residues that underlie the modulation of cGMP sensitivity.

The PTPs and PTKs that regulate rod CNG channels may be active independent of extracellular ligands (such as v-Src), or they may be receptor-activated. Rod outer segments contain several types of growth factor receptors that exhibit PTK activity in the presence of the appropriate ligands. Most notably, receptors for insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) are found in high density in rod outer segments and can elicit tyrosine phosphorylation of the G-protein transducin (Zick et al., 1987), suggesting that IGF-1 can influence phototransduction. IGF-1 is synthesized and released by retinal pigment epithelial cells (Waldbillig et al., 1991), which are crucial for regulating photoreceptor function. Other receptor PTKs also exist on rod outer segments (Mascarelli et al., 1989), but it remains to be determined which, if any, are involved in modulating the sensitivity of CNG channels.

In conclusion, we have shown that the sensitivity of rod CNG channels to cGMP is modulated by tyrosine phosphorylation. Our results raise many intriguing questions about the site of tyrosine phosphorylation, the intracellular and extracellular signals that regulate PTKs and PTPs in rods, and the impact of tyrosine phosphorylation on the light response. Thus, despite having achieved a detailed and advanced understanding of the complexity of phototransduction, our results demonstrate that new levels of biochemical modulation of the signaling cascade continue to be discovered.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (NS 30695) and the American Heart Association, Florida Affiliate (9502002) to R.H.K. B.T. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Predoctoral Fellow. We thank Dr. Scott Nawy for advice and comments on this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addresses to Dr. Richard H. Kramer, P.O. Box 016189, University of Miami School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33101.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aniksztejn L, Catarsi S, Drapeau P. Channel modulation by tyrosine phosphorylation in an identified leech neuron. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;498:135–142. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassidy P, Hoar PE, Kerrick WG. Irreversible thiophosphorylation and activation of tension in functionally skinned rabbit ileum strips by [35S]ATP-γ-S. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:11148–11153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Martin BL, Brautigan DL. Regulation of protein serine-threonine phosphatase type-2A by tyrosine phosphorylation. Science. 1992;257:1261–1264. doi: 10.1126/science.1325671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen T-Y, Peng Y-W, Dhallan RS, Ahamed B, Reed RR, Yau K-W. A new subunit of the cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel in retinal rods. Nature. 1993;362:764–767. doi: 10.1038/362764a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen P. Structure and regulation of protein phosphatases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:453–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ertel EA. Excised patches of plasma membrane from vertebrate rod outer segments retain a functional phototransduction enzymatic cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4226–4230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuhrer C, Hall ZW. Functional interaction of Src family kinases with the acetylcholine receptor in C2 myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32474–32481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon SE, Brautigan DL, Zimmerman AL. Protein phosphatases modulate the apparent agonist affinity of the light-regulated ion channel in retinal rods. Neuron. 1992;9:739–748. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90036-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon SE, Downing-Park J, Zimmerman AL. Modulation of the cGMP-gated ion channel in frog rods by calmodulin and an endogenous inhibitory factor. J Physiol (Lond) 1995a;486:533–546. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon SE, Downing-Park J, Tam B, Zimmerman AL. Diacylglycerol analogs inhibit the rod cGMP-gated channel by a phosphorylation-independent mechanism. Biophys J. 1995b;69:409–417. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79913-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heffetz D, Bushkin I, Dror R, Zick Y. The insulomimetic agents H2O2 and vanadate stimulate protein tyrosine phosphorylation in intact cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2896–2902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes TC, Fadool DA, Levitan IB. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Kv13 potassium channel. J Neurosci. 1996a;16:1581–1590. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01581.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes TC, Fadool DA, Ren R, Levitan IB. Association of Src tyrosine kinase with a human potassium channel mediated by SH3 domain. Science. 1996b;274:2089–2091. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter T. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Cell. 1995;80:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu YT, Molday RS. Modulation of the cGMP-gated channel in rod photoreceptor cells by calmodulin. Nature. 1993;361:76–79. doi: 10.1038/361076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang X-Y, Morelli AD, Peralta EG. Tyrosine kinase-dependent suppression of a potassium channel by the G1 protein-coupled muscarinic receptor. Cell. 1993;75:1145–1156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90324-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ildefonse M, Crouzy S, Bennett N. Gating of retinal rod cation channel by different nucleotides: comparative study of unitary channels. J Membr Biol. 1992;130:91–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00233741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonas EA, Knox RJ, Kaczmarek LK, Schwartz JH, Solomon DH. Insulin receptor in Aplysia neurons: characterization, molecular cloning, and modulation of ion currents. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1645–1658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01645.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karpen JW, Brown RL, Stryer L, Baylor DA. Interactions between divalent cations and the gating machinery of cyclic GMP-activated channels in salamander retinal rods. J Gen Physiol. 1993;101:1–25. doi: 10.1085/jgp.101.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaupp BU, Niidome T, Tanabe T, Terada S, Bonigk W, Stuhmer W, Cook NJ, Kangawa K, Matsuo H, Hirode T, Miyata T, Numa S. Primary structure and functional expression from complementary DNA of the rod photoreceptor cGMP-gated channel. Nature. 1989;342:762–766. doi: 10.1038/342762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koerschen HG, Illing M, Seifert R, Sesti F, Williams A, Gotzes S, Colville C, Muller F, Dose A, Godde M, Molday L, Kaupp UB, Molday RS. A 240 kDa protein represents the complete beta subunit of the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel from rod photoreceptor. Neuron. 1995;15:627–636. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacKintosh C, Beattie KA, Klumpp S, Cohen P, Cod GA. Cyanobacterial microcystin-LR is a potent and specific inhibitor of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A from both mammals and higher plants. FEBS Lett. 1990;264:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80245-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mascarelli F, Raulais D, Courtois Y. Fibroblast growth factor phosphorylation and receptors in rod outer segments. EMBO J. 1989;8:2265–2273. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moss SJ, Gorrie GH, Amato A, Smart TG. Modulation of GABAA receptors by tyrosine phosphorylation. Nature. 1995;377:344–348. doi: 10.1038/377344a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakatani K, Koutalis Y, Yau K-W. Ca2+ modulation of the cGMP-gated channels of bullfrog retinal rod photoreceptors. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;484:69–76. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onoda T, Iinuma H, Sasaki Y, Hamada M, Isshiki K, Naganama H, Takeuchi T, Tatsuta K, Umezawa K. Isolation of a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor, lavendustin A, from Streptomyces griseolavendus. J Nat Prod. 1989;52:1252–1257. doi: 10.1021/np50066a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reinhart PH, Levitan IB. Kinase and phosphatase activities intimately associated with a reconstituted calcium-dependent potassium channel. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4572–4579. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04572.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruegg UT, Burgess GM. Staurosporine, K252a and UCN-01: potent but nonspecific inhibitors of protein kinases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1989;10:218–222. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegelbaum SA. Ion channel control by tyrosine phosphorylation. Curr Biol. 1994;4:242–245. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swarup G, Cohen S, Garbers DL. Inhibition of membrane phosphotyrosyl-protein phosphatase activity by vanadate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982;107:1104–1109. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)90635-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swope SL, Huganir RL. Molecular cloning of two abundant protein tyrosine kinases in Torpedo electric organ that associate with the acetylcholine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25152–25161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swope SL, Huganir RL. Binding of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor to SH2 domains of Fyn and Fyk protein tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29817–29824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tapley P, Lamballe F, Barbacid M. K252a is a selective inhibitor of the tyrosine protein kinase activity of the trk family of oncogenes and neurotrophin receptors. Oncogene. 1992;7:371–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umezawa K, Hori T, Tajima H, Imoto M, Isshiki K, Takeuchi T. Inhibition of epidermal growth factor-induced DNA synthesis by tyrosine kinase inhibitors. FEBS Lett. 1990;260:198–200. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80102-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waldbillig RJ, Pfeffer BA, Schoen TJ, Adler AA, Shen-Orr Z, Scavo L, LeRoith D, Chader GJ. Evidence for an insulin-like growth factor autocrine-paracrine system in the retinal photoreceptor-pigment epithelial cell complex. J Neurochem. 1991;57:1522–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb06347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallace BG. Regulation of the interaction of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors with the cytoskeleton by agrin-activated protein tyrosine kinase. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:1121–1129. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang YT, Yu XM, Salter MW. Ca2+-independent reduction of N-methyl-d-aspartate channel activity by protein tyrosine phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1721–1725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson GF, Kaczmarek LK. Mode-switching of a voltage-gated cation channel is mediated by a protein kinase-A regulated tyrosine phosphatase. Nature. 1993;366:433–438. doi: 10.1038/366433a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiong Z, Cheung DW. ATP-dependent inhibition of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle cells by neuropeptide Y. Pflügers Arch. 1995;431:110–116. doi: 10.1007/BF00374383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu X-M, Askalan R, Keil GJ, Salter MW. NMDA channel regulation by channel-associated protein tyrosine kinase Src. Science. 1997;275:674–678. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zick Y, Spiegel AM, Sagi-Eisenberg R. Insulin-like growth factor I receptors in retinal rod outer segments. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10259–10264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]