Abstract

We used paired recordings to study the development of synaptic transmission between inhibitory interneurons of the molecular layer and Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex of the rat. The electrophysiological data were combined with a morphological study of the recorded cells using biocytin or Lucifer yellow staining. Thirty-one interneuron–Purkinje cell pairs were obtained, and 11 of them were recovered morphologically. The age of the rats ranged from 11 to 31 d after birth. During this period synaptic maturation resulted in an 11-fold decrease in the average current evoked in a Purkinje cell by a spike in a presynaptic interneuron. Unitary IPSCs in younger animals exhibited paired-pulse depression, whereas paired-pulse facilitation was found in more mature animals. These data suggest that reduction in transmitter release probability contributed to the developmental decrease of unitary IPSCs. However, additional mechanisms at both presynaptic and postsynaptic loci should also be considered. The decrease of the average synaptic current evoked in a Purkinje cell by an action potential in a single interneuron suggests that as development proceeds interneuron activities must be coordinated to inhibit efficiently Purkinje cells.

Keywords: inhibitory synapses, cerebellum, paired recordings, development, single-axon IPSCs, stellate cells, basket cells

During development the number of synaptic contacts central neurons receive increases dramatically (Blue and Parnavelas, 1983; Miller, 1986). Functional changes have been reported to occur postsynaptically as a result of modifications of receptor properties (e.g., Sakmann and Brenner, 1978; Hestrin, 1992;Tia et al., 1996). However, little is known on the developmental changes in the strength of synaptic interactions among individual neurons, which depends on both presynaptic and postsynaptic factors. To explore these issues it is necessary to quantify synaptic currents in paired recordings of identified cells as a function of age, a task that has been achieved only once so far (Bolshakov and Siegelbaum, 1995). This study performed on excitatory synapses in the hippocampus showed a developmental decrease of the release probability without postsynaptic modification. It would be interesting to see whether other synapses in other regions of the CNS exhibit such functional modifications.

The cerebellar cortex of the rat undergoes major changes during the first 4 postnatal weeks (Altman and Bayer, 1997). Purkinje cells (PCs) are present at birth and grow extensive dendrites from postnatal day 7 (P7) until P30. Two types of inhibitory interneurons are traditionally distinguished in the molecular layer (ML) of the rat cerebellar cortex, basket cells (BCs) and stellate cells (SCs). They arise from dividing progenitor cells in the white matter between P1 and P14 (Zhang and Goldman, 1996) and reach their final location between P7 and P21 (Altman, 1972; Zhang and Goldman, 1996). The cell bodies of BCs and SCs are respectively found in the lower third and upper two-thirds of the ML.

The inhibitory control of PCs is mediated by SCs and BCs (Eccles et al., 1966a; Midtgaard, 1992b; Vincent and Marty, 1996) and by PCs via their recurrent collaterals (Eccles et al., 1966b). In mature rats, the number of ML inhibitory interneurons per PC is as high as 10 (Korbo et al., 1993). Therefore as development proceeds, between P7 and P21, the number of inhibitory interneurons contacting a single PC could increase considerably. Functional studies indicate that BCs and SCs inhibit PCs as early as P10 (Crépel, 1974; Batchelor and Garthwaite, 1992). In a recent study IPSCs evoked in PCs by the activity of a single presynaptic interneuron were monitored in paired recordings (Vincent and Marty, 1996). In this work powerful IPSCs were observed (up to several nanoamperes) in rat cerebellar slices at the second postnatal week (P9–P15). If large IPSCs are also present at later developmental stages, when PCs are likely to be contacted by a larger number of presynaptic interneurons, the resulting barrage of inhibitory currents would be expected to inhibit PCs and to prevent the initiation of action potentials.

We studied the development of the interneuron→PC synapse using paired recordings from synaptically connected neurons, combined with morphological techniques. A dramatic reduction with age of the average IPSC evoked in a PC by the activity of a single interneuron was found. Furthermore, both presynaptic and postsynaptic factors were found to be involved.

These results have been presented in an abstract form (Pouzat et al., 1996).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of slices

During deep anesthesia with Metofane (Jansen), Wistar rats (P11–P31) were decapitated, and the cerebellum was excised and placed in a cold (4°C) saline solution. Sagittal or parasagittal slices (150 μm thickness) were cut from the vermis with a Microslicer (Dosaka). The slices were allowed to recover for at least 1 hr in a saline solution maintained at ∼34°C before being transferred to the recording chamber, where they were continuously perfused at a rate of 1–2 ml/min with the same saline solution at room temperature.

Solutions

The extracellular saline contained (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 10 glucose and was bubbled with 5% CO2 and 95% O2. For PC recordings, pipettes contained (in mm): 150 CsCl or 150 KCl, 10 BAPTA or 10 EGTA, 4.6 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 1 CaCl2, 4 Na-ATP, and 0.4 Na-GTP and 0.2% biocytin or 0.1% Lucifer yellow (dipotassium salt). For interneuron recordings, the composition of the intracellular solution was (in mm): 150 potassium gluconate or 150 KCl, 1 EGTA and 0.1 CaCl2 or 10 EGTA and 1 CaCl2, 4.6 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 4 Na-ATP, and 0.4 Na-GTP and 0.2% biocytin or 0.2% neurobiotin. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) except neurobiotin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Presynaptic and postsynaptic recordings

Borosilicate patch pipettes (Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany) were pulled to a final tip resistance of 1.9–2.5 MΩ for PC pipettes (with chloride solution) and 10–12 MΩ for interneuron pipettes (with a gluconate solution). Cells were visually identified using differential interference contrast [Zeiss Axioscop; 63×, 0.9 numerical aperture (NA) objective, 0.63 NA condenser]. Owing to the distribution of boutons on the axons of mature basket (Bishop, 1993) and stellate (Pouzat and Kondo, 1996) cells, interneuron recordings were preferentially attempted in the putative dendritic field of the recorded PC. The membrane potentials of both postsynaptic and presynaptic (when a presynaptic whole-cell configuration was obtained) cells were held at −60 mV using two patch-clamp amplifiers (EPC 9, Heka; and Axopatch 200A, Axon Instruments). Series resistance compensation (50–80%) was routinely used for young PCs (Llano et al., 1991), but for the more mature ones it was generally not capable of speeding up the slow components of the current transient evoked by a voltage pulse (250 msec long) and therefore was not used for 3 of the 10 cell pairs at P26–P31.

In many experiments the presynaptic interneuron was recorded cell-attached, and the postsynaptic PC was recorded with the whole-cell configuration. In these cases continuous 1-min-long acquisition was used, with a sampling rate of 4 kHz and a Bessel filter set on 0.8 and 1 kHz for the EPC 9 and Axopatch, respectively. The series resistance of the postsynaptic PC was checked every one or two acquisition protocols. When a presynaptic whole-cell recording was used, the presynaptic interneuron was stimulated with short (2 msec) voltage pulse with an amplitude (typically 40–60 mV from rest) suitable to evoke an unclamped sodium action current. For the paired-pulse experiments, the onsets of the two pulses were separated by 30 msec, and the membrane was hyperpolarized by 10 mV between stimuli to remove voltage-dependent inactivation. This stimulation was repeated every 1–2 sec. Data were sampled at 20 kHz, and the Bessel filter was set to 4 and 2 kHz for the EPC 9 and Axopatch amplifiers, respectively.

No junction potential correction was applied for the experiments when a potassium gluconate solution was used to record from interneurons. Nevertheless, in several experiments several holding potentials (from −50 to −70 mV) were tried presynaptically, and no change in the postsynaptic response was found (as described by Vincent and Marty, 1996). Therefore, the 10 mV junction potential of the potassium gluconate solution should not affect the results.

Analysis

All the data were analyzed using Igor (Wavemetrics) together with in-house-developed routines.

Cell-attached presynaptic. Pairs of cells with a presynaptic cell-attached configuration were analyzed using an off-line, spike-triggered averaging process. Briefly, the presynaptic spikes were detected, and a window was positioned in the postsynaptic trace, with the peak of the presynaptic spike at given position, producing a series of “spike-locked sweeps.” These sweeps were then averaged, and positions were set for a peak measuring window (typically 2.5 msec long) and for a baseline measuring window (typically 2.0 msec long). The amplitudes of the individual events were then measured by subtracting the average currents within the two windows on each sweep. The noise was measured in a similar way (i.e., by using identical peak window length, baseline window length, and spacing between the windows) from the same sweeps, with the averaging windows positioned before the spike or from randomly generated points in the postsynaptic trace (this last method was preferred when the presynaptic firing rate was low). Care was taken to select a stationary presynaptic regimen to obtain a statistically meaningful estimate of the average evoked IPSC [or single-axon IPSC (sa-IPSC)].

Whole-cell presynaptic. For paired-pulse experiments in young animals (P11–P15), in which the synaptic response to the first stimulus was large and in which the prestimulus baseline current was not reached within the interstimulus interval (30 msec), the response to the first stimulus was subtracted to correct the measurement of the second response. A scaled averaged response was used for this subtraction.

Statistics

The statistical significance of the difference of the mean of two samples was computed with a Mann–Whitney test. When three samples were compared [for the amplitude, coefficient of variation (CV), failure frequency, and variance over mean], an ANOVA was used first to show that the samples came from distributions with different means, and then a Mann–Whitney test was used on each pair of samples. The correlation between rise time and half-width and between amplitude and rise time of sa-IPSCs was estimated with Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient. The variance used in the estimation of the CV and of the variance/mean ratio was computed by subtracting the noise variance from the evoked response variance. Because a reliable estimate of variance requires more data points than a reliable estimate of the mean, we obtained a reasonable estimate for only 21 of the 31 pairs. Averages are given together with the SE.

Estimation of failure frequency

In general the failure frequency (i.e., the estimate of the failure probability) could not be estimated by examining individual sweeps owing to the high background activity in the PCs and the small amplitude of the evoked events in more mature rats. Therefore, the cumulative distributions of both the sa-IPSCs and the noise were obtained by rank ordering, and the noise distribution was scaled to fit the sa-IPSC distribution in the negative current region. This scaling factor was taken as the failure frequency. For a few pairs with low background activity and large individual evoked IPSCs, an estimate of failure frequency could be obtained by classifying the individual sweeps as failure or success. In some pairs (5 of 31) insufficient data were collected to obtain a reliable estimate of failure probability.

Morphology

Our procedure was adapted from that of Horikawa and Armstrong (1988). At the end of each recording the patch pipettes were removed, the relative positions of the cells were noted, and the slice was fixed at room temperature in a phosphate buffer (PB) with 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde or, when the PC was filled with Lucifer yellow, with 4% paraformaldehyde. After 1 hr at room temperature, the slices were maintained at 4°C until processing. The slices were then washed in PB, and endogenous peroxidase was quenched with 89% PB, 10% methanol, and 1% H2O2 for 5 min. Slices were then incubated for 2 hr in PB with 0.4% Triton X-100 and then for at least 2 hr in PB with avidin-conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (ABC kit, Vector). The slices were then washed in PB or Tris buffer (TB) and stained with diaminobenzidine (DAB, 0.05%) and H2O2 (0.003%) in PB. The TB-washed slices were first incubated in TB with DAB (0.02%) and Nickel-ammonium (0.15%) for 20–40 min, after which the staining reaction was triggered by transferring the slices in a TB/DAB/Ni solution with H2O2 (0.02%). The reaction was stopped by transferring the slices back into PB or TB.

Two different embedding methods were used. The DAB-stained slices were dehydrated in an alcohol series and embedded in Canada balsam. A significant shrinkage (15–25%) occurred during the dehydration procedure. The DAB/Ni-stained slices were embedded directly in TB with 15–20% glycerol.

The Lucifer yellow-filled PCs were imaged with a CCD camera and a 63× water immersion objective. The DAB- and DAB/Ni-stained cells were photographed with a Zeiss microscope using a 100× (1.25 NA) oil immersion or a 40× (0.65 NA) objective, a 1.4 NA oil immersion condenser, differential interference contrast optics, and a green filter. The cells were drawn with a drawing tube attached to the microscope and the 100× objective. The photo montages were done with Adobe Photoshop.

RESULTS

This study is based on data from 31 basket cells (BC)– or stellate cells (SC)–PC pairs recorded from rat cerebellar slices, the ages of which ranged from P11 to P31. The whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique (Hamill et al., 1981, Edwards et al., 1989) was used to record from PCs. Because symmetrical chloride concentrations were used (see Materials and Methods), chloride-mediated currents were inward at the holding potential (−60 mV).

Recordings from inhibitory interneurons (BCs and SCs) were obtained using a cell-attached and/or whole-cell configuration. In the first case “action currents” attributable to the spontaneous firing of these cells (Midtgaard, 1992a; Llano and Gerschenfeld, 1993; Vincent and Marty, 1996) were observed. An off-line, spike-triggered averaging was used to estimate the amplitude of the sa-IPSC. This configuration is advantageous in the sense that dialysis of the presynaptic cell does not occur. It has, however, the drawback that the presynaptic spiking is not controlled. When the whole-cell configuration was used presynaptically, it was possible to control the interspike interval and to study its effect on the evoked response. The drawback associated with this recording configuration is the dialysis of the presynaptic cell and an associated rundown of synaptic transmission.

Developmental change of sa-IPSC amplitude

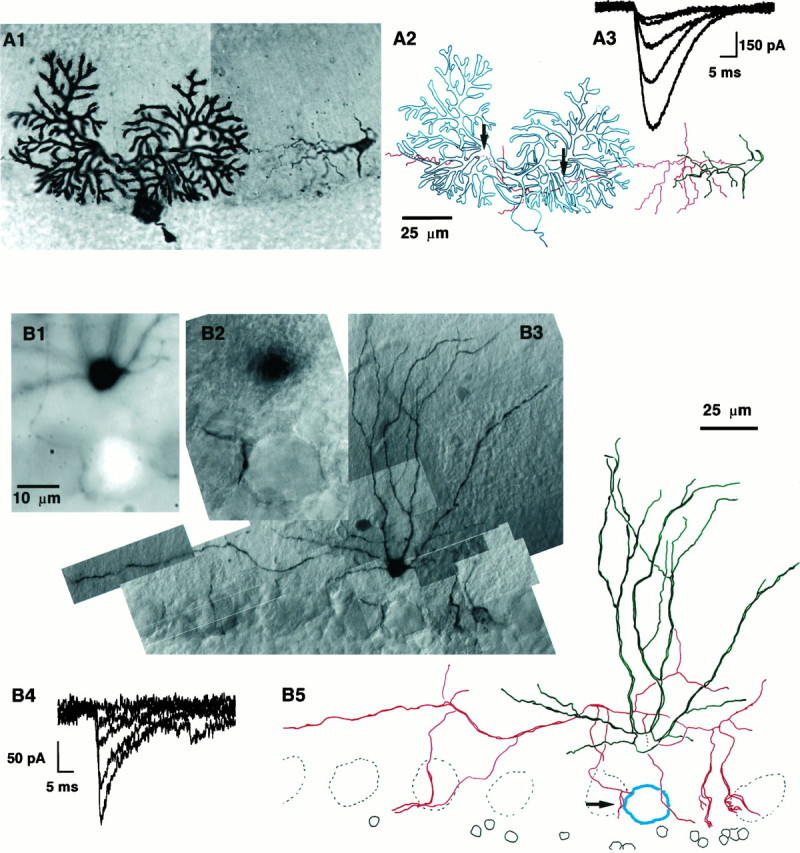

When paired recordings from young (P11–P15) and more mature (P26–P31) animals were compared, we observed a dramatic difference in sa-IPSC amplitude. This observation is illustrated in Figure1, in which two BC–PC pairs are shown. The first cell pair (Fig. 1A) is from a P11 rat, and the second (Fig. 1B) is from a P28 rat. The recordings shown were obtained with a presynaptic whole-cell configuration. Figure 1, A3 and B4, illustrates individual postsynaptic responses to presynaptic stimuli (2 msec voltage pulses from −60 to −10 mV). The trial-to-trial fluctuations of the responses are typical of CNS synapses (Kuno, 1964; Miles and Wong, 1984; Mason et al., 1991; Barbour, 1993; Thomson et al., 1993;Buhl et al., 1994) and have been reported already at this synapse for P9–P15 animals (Vincent and Marty, 1996). Two basic differences can be observed between the two cell pairs. First, the sa-IPSC amplitudes from the younger cell pair are much larger than those from the more mature cell pair. Second, failures were frequently observed in the cell pair from the more mature animal but only rarely in the younger cell pair.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the developmental decrease of sa-IPSC amplitude. The PC layer has been orientedhorizontally, the pial surface is toward thetop, and the granular layer is toward thebottom. A, BC–PC pair from a P11 rat.A1, Photo montage of the pair with both cells filled with biocytin. The PC is on the left, and the BC is on the right. The BC axon can be followed until it enters the PC dendritic field and can be seen again as it continues its course past the PC. The PC axon is cut shortly after its origin. The external germinal layer can be seen above the limit of the Purkinje cell dendritic field (top left corner). A2, Drawing of the pair; the somatodendritic compartment of the basket cell is drawn in green, and its axon is inred. The PC is drawn in blue. The twoarrows point to sites of putative synaptic contacts between the presynaptic axon and the postsynaptic cell. Note that the dendritic arborization of the BC is little developed at this stage, whereas its axon is already long and ramified but does not show any of the axosomatic specializations typical of BC–PC synapses. This pair was dehydrated and embedded in Canada balsam; during this procedure the slice shrunk with local inhomogeneities, which gave rise to the “wavy” appearance of the axon. The scale bar holds for bothA1 and A2. A3, Examples of sa-IPSCs recorded in the PC after short voltage pulses in the presynaptic BC. B, BC–PC pair from a P28 rat. The BC was filled with biocytin, and the soma of the PC was filled with Lucifer yellow. B1, Detailed picture of the pair taken with fluorescence microscopy. The soma of the PC is the bright spot at the bottom (the dendritic tree of the PC was not filled). The soma of the BC is the black spot at the top. The BC axon originates on theright of the cell body (at “3 o’clock”) and bends upward at the beginning of its course. Five out-of-focus dendritic branches of the BC are visible as well. A descending axon collateral of the BC comes in close apposition to the PC soma from the left. B2, Transmitted light picture of the same field as in B1. The soma of the PC is clearly recognizable (in focus) as well as the putative contact (on the left, at “9 o’clock”), the soma of the BC is slightly out of focus. The scale bar is common forB1 and B2. B3, General view of the BC (only two-thirds of the axon are shown). This slice was not dehydrated and was embedded in Tris buffer with 15% glycerol, leading to a better preservation of the neurite appearance than inA. B4, Examples of sa-IPSCs evoked in the PC on stimulation of the BC. Note the amplitude difference with the sa-IPSCs of A3. B5, Drawing of the pair. As in A, the somatodendritic compartment of the interneuron is green, the interneuron axon isred, and the postsynaptic PC is blue. Thearrow points to the putative synaptic contact. The dendritic arborization of the BC is much more extensive than inA2. The axon sends two thick descending collaterals toward PC somata on the right. The scale bar holds for both B3 and B5.

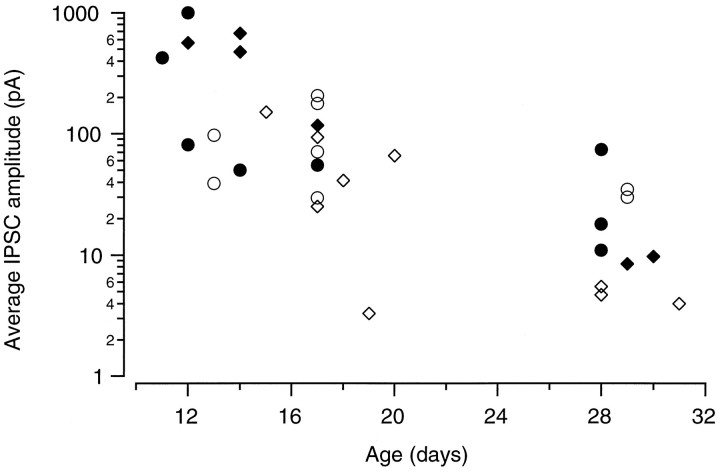

The developmental change in the mean unitary IPSCs obtained from 31 pairs is illustrated in Figure 2. We found that the average sa-IPSC decreased from 330 ± 100 pA in young animals (P11–P15) to 20 ± 7 pA in more mature animals (P26–P31). Thus, there is an order of magnitude difference between the amplitudes of sa-IPSCs observed in the two extreme ages. At the intermediate age (P16–P21) the mean sa-IPSC was 80 ± 18 pA. An ANOVA test showed that the three samples came from distributions with different means (p < 0.01). Moreover, the decrease in the average sa-IPSC amplitude with development is present independently of both cell type (circles, BCs;diamonds, SCs) and mode of presynaptic recording (filled symbols, whole-cell; open symbols, cell-attached).

Fig. 2.

Developmental changes of sa-IPSC amplitudes. Average sa-IPSCs from the 31 pairs studied. The data points for presynaptic BCs are marked by circles and for presynaptic SCs are marked by diamonds.Filled and open symbols represent presynaptic whole-cell and cell-attached recordings, respectively.

Several nonexclusive factors can account for such a developmental decrease. First, one can argue that because Purkinje cell dendrites grow extensively during the period under investigation (Berry and Bradley, 1976), one should expect increased dendritic filtering and an associated decrease in the average measured sa-IPSC amplitude (Rall and Segev, 1985; Major, 1993; Spruston et al., 1994). Second, developmental changes in the GABA receptors (receptor subunit composition, phosphorylation state, and aggregation state) could occur, as already shown at an other inhibitory synapse in the cerebellar cortex (Tia et al., 1996). Many presynaptic factors can be proposed as well, including changes in the number of release sites or in the release probability per site (which may reflect changes in action potential propagation failure, change in presynaptic calcium homeostasis, or changes in presynaptic release machinery). We next examined the various mechanisms that could give rise to the developmental decrease of sa-IPSC amplitude.

Morphology of the synaptic contacts

The morphology of 11 of the 31 pairs was retrieved (at least partially) after biocytin or Lucifer yellow staining (see Materials and Methods). The latter staining was used for PCs to make the interneuron axon easier to follow as it waves through the PC dendritic field. In young rats (P11–P15), pairs with either BCs or SCs as presynaptic elements were studied (Fig. 1A1,A2). In the intermediate period (P16–P21) one BC–PC pair and one SC–PC pair were visualized (data not shown), and in more mature rats (P26–P31) three BC–PC pairs were partially recovered (Fig.1B3,B5).

In young rats the axonal diameter was uniform, exhibiting very few varicosities (putative synaptic sites; Breitenberg and Schüz, 1991). Thus, it was not possible to estimate the number of release sites. However, the morphological data suggested putative locations for release sites. For instance, in Figure 1, A1 andA2, two regions (Fig. 1A2, arrows) could be identified where the axon came in close proximity to the PC dendrites such that the distance between these two elements was below the resolution limit of the optical microscope. On the other hand, in the other regions of the dendritic field, the axon and the dendritic branches were readily distinguishable as separate entities. For example, the descending collateral that runs along the primary dendrite of the PC (Fig. 1A2) does not contact it.

In the more mature rats, the BC axons were found to have a much more conventional morphology (Ramón y Cajal, 1911; Bishop, 1993), exhibiting varicosities on their collaterals and “thick” axosomatic contacts with PCs (Fig. 1B3,B5, the tworightmost descending axon collaterals). The three BC–PC pairs partially recovered from P26–P31 rats (corresponding to thethree filled circles at 28 d in Fig. 2) showed (at least some) somatic contacts.

The dendrites of Purkinje cells grow extensively during development. Therefore it is expected that attenuation of synaptic currents by dendritic filtering will increase with age. However, the morphological data suggest that at least some of the synaptic contacts in more mature animals are somatic or proximal, and thus, the attenuation of these contacts would be less than that expected at distal locations.

Kinetics of the average sa-IPSCs

If the developmental decrease in the amplitude of the sa-IPSC was the result of passive filtering, a reduction in the amplitude and a slowing in the kinetics of the currents would be expected (Rall and Segev, 1985; Major, 1993; Spruston et al., 1994).

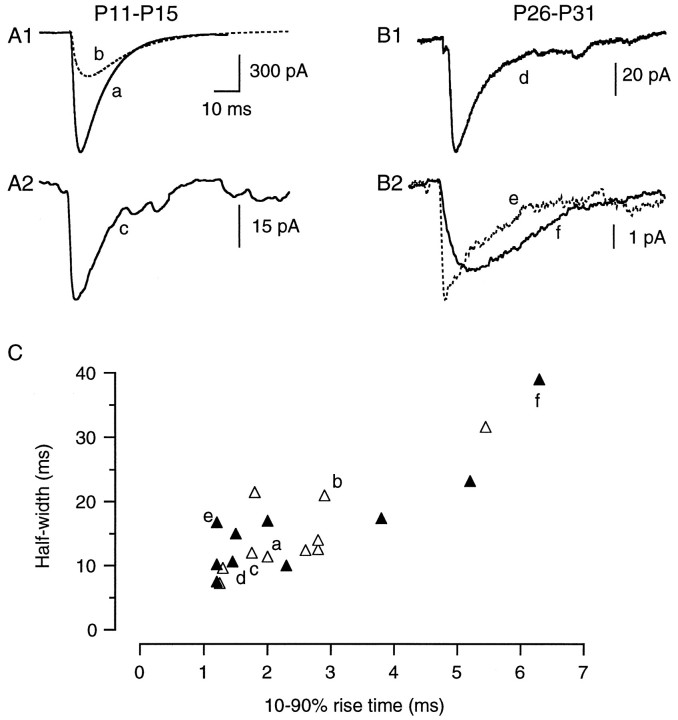

The kinetics of the currents within and between age groups (young, P11–P15; and more mature, P26–P31) were compared as illustrated in Figure 3. For both age groups the largest (Fig. 3a,d), smallest (Fig. 3c,f) and an intermediate (Fig. 3b,e) sa-IPSCs are shown, all with the same time scale but with different amplitude scales (Fig.3A1,A2,B1,B2). Figure 3B2 shows that slowly rising and decaying sa-IPSCs were recorded (Fig. 3f), as expected for an attenuated signal. But small average sa-IPSCs exhibiting a fast time course (the amplitude of Fig. 3e is 5 pA) were also recorded. A general comparison of the average sa-IPSC kinetics (Fig. 3C) showed a similarity of the two age groups, with rise times of 2.5 ± 0.4 msec at P11–P15 and 2.6 ± 0.5 msec at P26–P31 and half-widths of 15.3 ± 2.2 msec at P11–P15 and 16.7 ± 2.7 msec at P26–P31. Within both age groups a significant correlation was found between rise times and half-widths (p < 0.05) but not between rise times and amplitude (p > 0.05). The lack of correlation between the developmental reduction of synaptic current amplitude and slow kinetics together with the morphological data (showing that in more mature animals some of the PCs we recorded from receive somatic inputs from BCs) suggests that dendritic filtering cannot solely explain the 11-fold decrease in the sa-IPSC.

Fig. 3.

Kinetic properties of the sa-IPSCs. A, B, Averaged traces from P11–P15 (A) and P26–P31 (B) rats. For both ages the largest, the smallest, and an intermediate average are shown with the same time scale. A1, The largest (a, average of 80 sweeps) and an intermediate (b, dotted line, average of 71 sweeps) sa-IPSC from P11–P15 rats. A2, The smallest sa-IPSC from P11–P15 rats (c, average of 494 sweeps).B1, The largest sa-IPSC recorded from a P26–P31 rat (d, average of 50 sweeps). B2, An intermediate (e, dotted line, average of 969 sweeps) and the smallest sa-IPSCs (f, average of 2504 sweeps). These two currents have different time courses but similar peak amplitudes; f is filtered, and e is not. C, Plot of the half-width versus 10–90% rise time of the average sa-IPSCs in P11–P15 rats (open triangles) and P28–P31 rats (filled triangles). The two populations are kinetically similar, exhibiting the same correlation between rise time and half-width. Thelower-case letters correspond to the currents shown inA and B. The filled triangle at the bottom left (the fastest current) corresponds to the BC–PC pair shown in Figure1B; the slowest sa-IPSC from the younger rats (open triangle at top right) corresponds to the SC–PC pair of Figure 4A.

Developmental change of paired-pulse responses

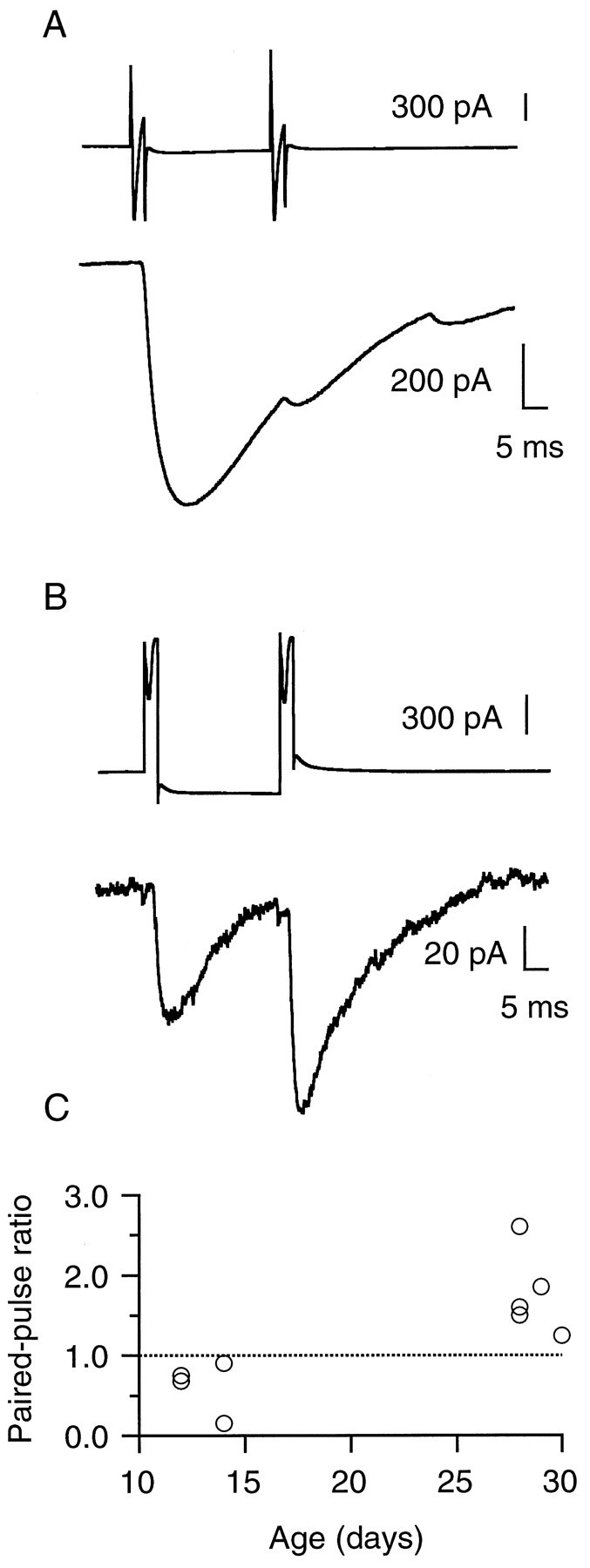

At the neuromuscular junction paired-pulse facilitation is inversely proportional to the mean quantal content, which is related to the release probability (Del Castillo and Katz, 1954; Martin, 1966;Mallart and Martin, 1968). Thus, changes in paired-pulse ratio (amplitude of the second response/amplitude of the first) are usually thought to be related to presynaptic function and to indicate changes in the release probability (Zucker, 1989; Manabe et al., 1993;Bolshakov and Siegelbaum, 1995). Therefore, to uncover a possible change in release probability, the response to a presynaptic paired-pulse protocol was studied.

Two short pulses interspersed by 30 msec were used, and the paired-pulse ratio was measured. In Figure4, an SC–PC pair from a P14 rat (Fig.4A) is compared with a BC–PC pair from a P28 rat (Fig. 4B). In agreement with the dependence of the mean amplitude with age the mean amplitude of the first pulse response in Figure 4A was >600 pA, whereas it was only 75 pA in Figure 4B. The inflection at the end of the postsynaptic trace in Figure 4A is attributable to a spontaneous event. A strong depression of the second response was seen in the younger rat, whereas facilitation occurred in the more mature rat. In four experiments (with three SCs and one BC as presynaptic interneurons) at P11–P15 a paired-pulse depression was always seen, whereas in five of five cell pairs at P26–P31, paired-pulse facilitation was found (with three BCs and two SCs as presynaptic interneurons). The individual results are shown on Figure4C. The average value of the paired-pulse ratio was 0.62 ± 0.16 at P11–P15 and 1.77 ± 0.23 at P26–P31; this difference was significant (p = 0.01).

Fig. 4.

Conversion of paired-pulse depression to paired-pulse facilitation. A, Paired-pulse stimulation at an SC–PC connection from a P14 rat. The top traceillustrates the presynaptic whole-cell current in response to the stimulating voltage pulse (the presynaptic interneuron was hyperpolarized from −60 to −70 mV between the two stimuli to avoid reduction of the sodium current amplitude). The bottom trace shows the average of six postsynaptic traces. The first response is large, and the second is strongly depressed.B, Paired-pulse stimulation of a BC–PC connection from a P28 rat. The bottom trace shows the average of six postsynaptic responses. The first response is small (compared withA), and the second response is facilitated.C, Individual paired-pulse ratios (second pulse response/first pulse response) found in nine pairs in which paired-pulse stimulations were applied. In younger animals the average paired-pulse ratio was 0.62 ± 0.16 (n = 4), whereas in more mature animals it was 1.77 ± 0.23 (n = 5).

Developmental changes of variance and failure frequency of the sa-IPSCs

The previous result suggests that the release probability at individual sites decreases as development proceeds. For pairs in which a large number of evoked responses could be recorded, two additional parameters, related to presynaptic function, could be estimated independently: the CV of sa-IPSCs and the failure probability.

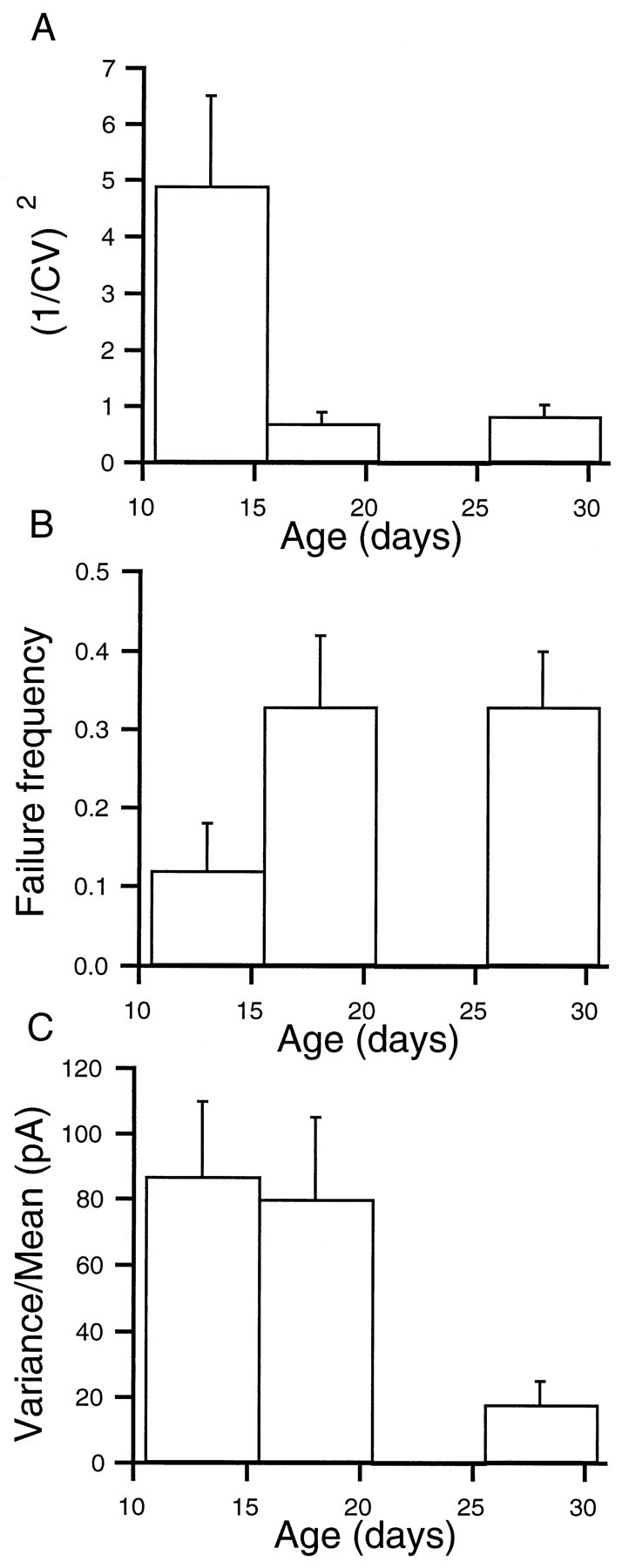

The squared inverse of the coefficient of variation, (1/CV)2, has been shown experimentally to increase by procedures increasing the release probability and to decrease when release probability is decreased (Clements 1990; Manabe et al., 1993;Barnes-Davies and Forsythe, 1995). In addition, however, a decrease in number of release sites would have an effect on (1/CV)2similar to that induced by a decrease in release probability. Therefore, changes in squared inverse of the coefficient of variation have been used to imply presynaptic changes (Manabe et al., 1993;Barnes-Davies and Forsythe, 1995). We found as shown in Figure5A that (1/CV)2decreases with development from 4.9 ± 1.6 (n = 8) at P11–P15 to 0.7 ± 0.2 (n = 7) at P16–P21 and 0.8 ± 0.2 (n = 6) at P26–P31. An ANOVA test showed that these samples came from distributions with different means (p < 0.025). Differences between the first and second means as well as between the first and third means were significant (p < 0.025 and p < 0.05, respectively), whereas the second and third means were not significantly different.

Fig. 5.

Developmental changes of (1/CV)2, failure frequency, and variance over mean ratio. A, (1/CV)2 decreased with development; at P11–P15 it was 4.9 ± 1.6 (n = 8); at P16–P21 it decreased to 0.7 ± 0.2 (n = 7); and at P26–P31 it was 0.8 ± 0.2 (n = 6). B, Failure frequency increased from 0.12 ± 0.06 (n = 8) at P11–P15 to 0.33 ± 0.09 (n = 10) at P16–P21, and it was 0.33 ± 0.07 at P26–P31 (n = 8). C, Var/mean decreased from 87 ± 23 pA (n = 8) at P11–P15 and 80 ± 25 pA (n = 7) at P16–P21 to 18 ± 7 pA (n = 6) at P26–P31.

The failure probability is another indicator of a presynaptic change that increases on a decrease of release probability or/and a decrease of number of release sites (Del Castillo and Katz, 1954; Martin, 1966;Isaacson and Walmsley, 1995). We have estimated the failure rate occurring at 26 cell pairs (see Materials and Methods). The failure frequency was 0.12 ± 0.06 (n = 8) at young cell pairs (P11–P15) and increased significantly to 0.33 ± 0.07 (n = 8) at more mature cell pairs (P26–P31). At an intermediate stage (P16–P21) the failure rate was 0.33 ± 0.09 (n = 10), similar to that estimated in more mature cell pairs. The ANOVA test showed that these samples came from distributions with different means (p < 0.025). The difference between the first and second or third means were significant (p < 0.025).

The three parameters previously studied suggest independently a presynaptic contribution to the overall developmental decrease in synaptic strength, but they do not rule out an additional postsynaptic change. To probe such a postsynaptic contribution, we evaluated the variance over mean ratio (var/mean) of individual sa-IPSCs. This parameter is expected to be dependent on the quantal size as predicted by the Poisson and the binomial models of synaptic transmission. In a Poisson model the quantal size, q is equal to var/mean, whereas in the binomial model q × (1 −p) = (var/mean), where p is the release probability. Therefore, in the former case a decrease of var/mean would indicate a decrease in q, and in the latter, given the decrease in p suggested by the paired-pulse experiments, a decrease of var/mean would indicate an even stronger decrease inq. These qualitative conclusions are expected to hold in a more general context, as shown by the calculations of Vincent and Marty (1996). We found that the average value of var/mean was 87 ± 23 pA (n = 8) at P11–P15; at P16–P21 it was 80 ± 25 pA (n = 7), and at P26–P31 it decreased to 18 ± 7 pA (n = 6). An ANOVA test showed that these samples came from distributions with different means (p < 0.01). The difference between the first and second means was not significant, whereas the difference between the first and the third means as well as the one between the second and the third were statistically significant (p < 0.05 and p < 0.025, respectively). These results suggest that a decrease in quantal size contributes to the overall developmental weakening of synaptic strength.

DISCUSSION

Our main finding is that the unitary IPSCs at both stellate cell→ and basket cell→Purkinje cell synapses undergo an 11-fold decrease in amplitude during development. During maturation paired-pulse depression is converted to paired-pulse facilitation. This finding suggests that developmental reduction of the release probability contributes to the decrease of unitary synaptic currents. Several other factors, both presynaptic and postsynaptic, however, may play a role.

Dendritic filtering cannot account for the developmental reduction of sa-IPSC amplitudes

During development Purkinje cell dendrites increase extensively in length. Therefore, attenuation of synaptic signals by dendritic filtering is likely to be more pronounced in more mature animals. The extent of the attenuation depends on the location of the synaptic inputs, however, and proximal synapses are expected to be attenuated less than distal ones. At least some of the cell pairs we recorded from in more mature animals had proximal or somatic contacts, as indicated by the relatively fast rise time (Fig. 2B,C) and the putative location of release sites (Fig. 1B). Moreover, as a deterministic relationship is expected between the amplitude and the rise and decay times of filtered currents, they should have smaller amplitude and slower kinetics than the unfiltered ones (Rall and Segev, 1985; Major, 1993; Spruston et al., 1994). Such a relation between amplitude and kinetics was not found in the sa-IPSCs we recorded (Fig. 3C), indicating that dendritic filtering cannot by itself account for the observed developmental decrease of sa-IPSC amplitudes. If four sa-IPSCs with slow rise times (>2 msec) from more mature rats are rejected, for the purpose of amplitude comparison, the average sa-IPSC amplitude of more mature rats is 30 ± 10 pA (the average without selection is 20 ± 7 pA), which is more than 11 times smaller than the corresponding one of young animals (330 ± 100 pA, P11–P15).

Presynaptic contribution to the developmental reduction of sa-IPSC amplitude

We have found that during development there is a change in the response to paired-pulse stimulation that is generally interpreted as reflecting presynaptic properties. The results of Figure 4 demonstrate a switch from paired-pulse depression in P11–P15 rats to paired-pulse facilitation in P26–P31 animals and suggest a decrease of release probability with development. In addition, we found a sixfold decrease in (1/CV)2 and a threefold increase in the frequency of failures that are usually interpreted as reflecting a decrease inp or/and a decrease in number of release sites (N). A precise interpretation of the changes of these last two parameters is model-dependent, but we see a clear decrease of the mean quantal content (i.e., the productp × N, or the mean number of vesicles released per action potential). Overall it seems reasonable to postulate a decrease in release probability, leaving open the possibility of a change in the number of release sites. This result corresponds to what Bolshakov and Siegelbaum (1995) found at an excitatory synapse in the hippocampus. Moreover, this presynaptic change would occur at an “early” stage (P16–P21) relative to the age range considered in this study (P11–P31).

Postsynaptic contribution to the developmental decrease of sa-IPSC amplitude

We found a sixfold developmental reduction in the variance over mean ratio. This change could be interpreted, under specific assumptions, as suggesting a decrease of quantal size. However, further experiments that study receptor function directly are needed to understand the possible role of postsynaptic receptors in the overall developmental IPSC decrease. Interestingly, at another GABAergic synapse in the cerebellar cortex, a change in miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) has been reported by Tia et al. (1996) and Brickley et al. (1996). These two groups have shown a decrease in the mIPSC amplitude and an acceleration of their kinetics.

Structure–function relation

As stated already, our morphological data do not allow us to evaluate the number of synaptic contacts between a given presynaptic interneuron and its postsynaptic PCs, and to our knowledge no quantitative morphological study of this synapse has been published. Nevertheless, our data can help address the nature of the difference between SCs and BCs. From the data in Figure 2, once dendritic filtering is taken into account, no major difference appears between IPSCs from BCs and SCs. Therefore, it seems reasonable to view SC and BC as a single cell type with different position of the cell bodies in the ML, as suggested by Ramón y Cajal (1911) and Sultan and Bower (1996).

From another viewpoint it seems interesting to remark that the active zone of the BC→PC synapse changes with development, being long in the young animals and becoming fragmented and shorter as development proceeds (Larramendi, 1969). It is tempting to correlate the ultrastructural change with the decrease of release probability, as has been suggested at the neuromuscular junction (Propst and Ko, 1987;Walrond et al., 1993; King et al., 1996).

Physiological consequences

Interneurons from the ML outnumber PCs by a factor of 10 in the adult rat (Korbo et al., 1993) and reach the molecular layer during the period we investigated (Altman, 1972; Zhang and Goldman, 1996). Therefore, a single PC should have few presynaptic interneurons at P11 and many more by P28. Moreover, Woodward et al. (1969), Crépel (1974), and Batchelor and Garthwaite (1992) have demonstrated that GABAergic inputs inhibit PCs as soon as P11, in contrast to other brain regions where GABA has an excitatory effect at early developmental stages [hippocampus (Ben-Ari et al., 1989), neocortex (Owens et al., 1996), and in cerebellar granule cells (Brickley et al., 1996)]. The present results show that the number of presynaptic elements and the strength of single inhibitory connections vary in opposing directions, which raises the possibility that one effect compensates the other, yielding an approximately constant inhibitory influence on PCs. The capability of a single interneuron to inhibit PC spikes, as has been shown in the turtle (Midtgaard, 1992b) and in the rat (without age specification; Clark and Häusser, 1995), would thus be expected to decrease strongly as development proceeds.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Max-Planck-Society, grants from the European Community, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinshaft Grant SFB 406 (C.P.), and National Eye Institute Grant EYE09120 (S.H.). We thank Alain Marty and Isabel Llano for helpful discussions and support and Andrew Boxall, Dario Protti, Henrique von Gersdorff, Ralf Schneggenburger, Vinod Subramaniam, Céline Auger, and Boris Barbour for comments and discussion.

Correspondence should be addressed to Christophe Pouzat, Arbeitsgruppe Zelluläre Neurobiologie, Max-Planck-Institut für Biophysikalische Chemie, Am Fassberg, D-37077 Göttingen, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman J. Postnatal development of the cerebellar cortex in the rat. I. The external germinal layer and the transitional molecular layer. J Comp Neurol. 1972;145:353–398. doi: 10.1002/cne.901450305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman J, Bayer SA. Development of the cerebellar system. CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbour B. Synaptic currents evoked in Purkinje cells by stimulating individual granule cells. Neuron. 1993;11:759–769. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes-Davies M, Forsythe ID. Pre- and postsynaptic glutamate receptors at a giant excitatory synapse in rat auditory brainstem slices. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;488:387–406. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batchelor AM, Garthwaite J. GABAB receptors in the parallel fiber pathway of rat cerebellum. Eur J Neurosci. 1992;4:1059–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Ari Y, Cherubini E, Corradetti R, Gaiarsa JL. Giant synaptic potentials in immature rat CA3 hippocampal neurones. J Physiol (Lond) 1989;416:303–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry M, Bradley P. The growth of the dendritic trees of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum of the rat. Brain Res. 1976;112:1–35. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bishop GA. An analysis of HRP-filled basket cell axons in the cat’s cerebellum. I. Morphometry and configuration. Anat Embryol. 1993;188:287–297. doi: 10.1007/BF00188219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blue ME, Parnavelas JG. The formation and maturation of synapses in the visual cortex of the rat. II. Quantitative analysis. J Neurocytol. 1983;12:697–712. doi: 10.1007/BF01181531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolshakov VY, Siegelbaum SA. Regulation of hippocampal transmitter release during development and long-term potentiation. Science. 1995;269:1730–1734. doi: 10.1126/science.7569903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breitenberg V, Schüz A. Anatomy of the cortex. Statistics and geometry. Springer; Berlin: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brickley SG, Cull-Candy SG, Farrant M. Development of a tonic form of synaptic inhibition in rat cerebellar granule cells resulting from persistent activation of GABAA receptors. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;497:753–759. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buhl EH, Halasy K, Somogyi P. Diverse sources of hippocampal unitary inhibitory postsynaptic potentials and the number of synaptic release sites. Nature. 1994;368:823–828. doi: 10.1038/368823a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark B, Häusser M. Synaptic inhibition of cerebellar Purkinje cells by single interneurons. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1995;21:595. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clements JD. A statistical test for demonstrating a presynaptic site of action for a modulator of synaptic amplitude. J Neurosci Methods. 1990;31:75–88. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crépel F. Excitatory and inhibitory process acting upon cerebellar Purkinje cells during maturation in the rat: influence of hypothyroidism. Exp Brain Res. 1974;20:403–420. doi: 10.1007/BF00237384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Castillo J, Katz B. Quantal components of the end-plate potential. J Physiol (Lond) 1954;124:560–573. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eccles JC, Llinás R, Sasaki K. Intracellularly recorded responses of cerebellar Purkinje cells. Exp Brain Res. 1966a;1:161–183. doi: 10.1007/BF00236869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eccles JC, Llinás R, Sasaki K. The action of antidromic impulses on the cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1966b;182:316–345. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards FA, Konnerth A, Sakmann B, Takahashi T. A thin slice preparation for patch-clamp recordings from neurones of the mammalian central nervous system. Pflügers Arch. 1989;414:600–612. doi: 10.1007/BF00580998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hestrin S. Developmental regulation of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic currents at a central synapse. Nature. 1992;357:686–689. doi: 10.1038/357686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth F. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high resolution current recordings from cells and cell free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horikawa K, Armstrong W. A versatile mean of intracellular labeling: injection of biocytin and its detection with avidin conjugate. J Neurosci Methods. 1988;25:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(88)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isaacson JS, Walmsley B. Counting quanta: direct measurements of transmitter release at a central synapse. Neuron. 1995;15:875–884. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King MJR, Atwood HL, Govind CK. Structural features of crayfish phasic and tonic neuromuscular terminals. J Comp Neurol. 1996;372:618–626. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960902)372:4<618::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korbo L, Andersen BB, Ladefoged O, Moller A. Total numbers of various cell types in rat cerebellar cortex using an unbiased sterological method. Brain Res. 1993;609:262–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90881-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuno M. Quantal components of excitatory postsynaptic potentials in spinal motoneurones. J Physiol (Lond) 1964;175:81–99. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larramendi LMH. Analysis of synaptogensis in the cerebellum of the mouse. In: Llinás R, editor. Neurobiology of cerebellar evolution and development. American Medical Association; Chicago: 1969. pp. 803–843. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Llano I, Gerschenfeld HM. Inhibitory synaptic currents in stellate cells of rat cerebellar slices. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;468:177–200. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Llano I, Marty A, Armstrong CM, Konnerth A. Synaptic- and agonist-induced excitatory currents of Purkinje cells in rat cerebellar slices. J Physiol (Lond) 1991;434:183–213. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Major G. Solutions for transients in arbitrarily branching cables: III. Voltage clamp problems. Biophys J. 1993;65:469–491. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81039-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mallart A, Martin AR. The relation between quantum content and facilitation at the neuromuscular junction of the frog. J Physiol (Lond) 1968;196:593–604. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manabe T, Wyllie DJA, Perkel DJ, Nicoll RA. Modulation of synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation: effect on paired pulse facilitation and EPSC variance in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1451–1459. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin AR. Quantal nature of synaptic transmission. Physiol Rev. 1966;46:51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mason A, Nicoll A, Stratford K. Synaptic transmission between individual pyramidal neurons of the rat visual cortex in vitro. J Neurosci. 1991;11:72–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-01-00072.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miles R, Wong RKS. Unitary inhibitory synaptic potentials in the guinea-pig hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 1984;356:97–113. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller WR. Maturation of rat visual cortex. III. Postnatal morphogenesis and synaptogenesis of local circuit neurons. Dev Brain Res. 1986;25:271–285. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(86)80236-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Midtgaard J. Membrane properties and synaptic responses of Golgi cells and stellate cells in the turtle cerebellum in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 1992a;457:329–354. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Midtgaard J. Stellate cell inhibition of Purkinje cells in the turtle cerebellum in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 1992b;457:355–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Owens DF, Boyce LH, Davis MBE, Kriegstein AR. Excitatory GABA responses in embryonic and neonatal cortical slices demonstrated by gramicidin perforated-patch recordings and calcium imaging. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6414–6423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06414.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pouzat C, Kondo S. An analysis of neurobiotin-filled stellate axons in the rat cerebellum. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1996;22:1632. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pouzat C, Hestrin S, Marty A. Decrease of synaptic strength with age at interneurone-Purkinje cells synapses. Eur J Neurosci [Suppl] 1996;9:6. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Propst JW, Ko C-P. Correlations between active-zone ultrastructure and synaptic function studied with freeze-fracture of physiologically identified neuromuscular junctions. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3654–3664. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-11-03654.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rall W, Segev I. Space-clamp problems when voltage clamping branched neurons with intracellular microelectrodes. In: Smith TG, Lecar H, Redman SJ, Gage PW, editors. Voltage and patch clamping with microelectrodes. American Physiological Society; Bethesda, MD: 1985. pp. 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramón y Cajal S. Histologie du système nerveux de l’homme et des vertébrés. Maloine; Paris: 1911. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakmann B, Brenner HR. Change in synaptic channel gating during neuromuscular development. Nature. 1978;276:401–402. doi: 10.1038/276401a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spruston N, Jaffe DB, Johnston D. Dendritic attenuation of synaptic potentials and currents: the role of passive membrane properties. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:161–166. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sultan F, Bower J. Classification of the rat cerebellar basket and stellate cells: evidence for a continuous distribution of types through principal component analysis. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1996;22:502. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomson AM, West DC. Fluctuations in pyramid-pyramid excitatory postsynaptic potentials modified by presynaptic firing pattern and postsynaptic membrane potential using paired intracellular recordings in rat neocortex. Neuroscience. 1993;54:329–346. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90256-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tia S, Wang JF, Kotchabhakdi N, Vicini S. Developmental changes of inhibitory synaptic currents in cerebellar granule neurons: role of GABAA receptor α6 subunit. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3630–3640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-11-03630.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vincent P, Marty A. Fluctuations of inhibitory postsynaptic currents in Purkinje cells from rat cerebellar slices. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;494:183–199. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walrond JP, Govind CK, Huestis SE. Two structural adaptations for regulating transmitter release at lobster neuromuscular synapses. J Neurosci. 1993;13:4831–4845. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-11-04831.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woodward DJ, Hoffer BJ, Lapham LW. Correlative survey of electrophysiological, neuropharmacological and histochemical aspects of cerebellar maturation in rat. In: Llinás R, editor. Neurobiology of cerebellar evolution and development. American Medical Association; Chicago: 1969. pp. 725–741. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang L, Goldman JE. Generation of cerebellar interneurons from dividing progenitors in white matter. Neuron. 1996;16:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zucker RS. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1989;12:13–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.12.030189.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]