Abstract

Genetic studies in Drosophila and in vertebrates have implicated basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) genes in neuronal fate determination and cell type specification. We have compared directly the expression of Mash1 and neurogenin1(ngn1), two bHLH genes that are expressed specifically at early stages of neurogenesis. In the PNS these genes are expressed in complementary autonomic and sensory lineages. In the CNS in situ hybridization to serial sections and double-labeling experiments indicate that Mash1 andngn1 are expressed in adjacent and nonoverlapping regions of the neuroepithelium that correspond to future functionally distinct areas of the brain. We also showed that in the PNS several other bHLH genes exhibit similar lineal restriction, as dongn1 and Mash1, suggesting that complementary cascades of bHLH factors are involved in PNS development. Finally, we found that there is a close association between expression of ngn1 and Mash1 and that of two Notch ligands. These observations suggest a basic plan for vertebrate neurogenesis whereby regionalization of the neuroepithelium is followed by activation of a relatively small number of bHLH genes, which are used repeatedly in complementary domains to promote neural determination and differentiation.

Keywords: bHLH proteins, Mash1, neurogenins, Notch ligands, neurogenesis, cell lineage

Central questions in developmental neurobiology include understanding how the nervous system is patterned into functionally distinct areas and how cellular diversity is generated within these areas. These questions have been addressed, using genetic analysis in the fruit fly Drosophila. Several important concepts have emerged from this system. First, proneural genes such asachaete-scute (ac-sc) and atonal, which encode transcription factors of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) type, function as neural determination genes (Jan and Jan, 1993) (for review, see Weintraub, 1993). Second, distinct proneural genes are used in different neuronal sublineages. For example, ac-sc is essential for external sensory organ formation, whereasatonal is required for that of chordotonal organs (Jan and Jan, 1994). Moreover, ectopic expression of as-sc in the wing disk promotes external sensory organ formation (Rodriguez et al., 1990; Brand et al., 1993), whereas that of atonal promotes chordotonal but not external organ formation (Jarman et al., 1993). Thus, proneural genes play a critical role not only in the choice of neural fate but also in the choice of neuronal subtype.

The functional characterization of vertebrate homologs ofDrosophila proneural genes has suggested that the principles described above may be applicable to mammalian neurogenesis as well. For example, the mammalian ac-sc homolog 1 (Mash1) (Johnson et al., 1990) is expressed in subsets of neuronal precursors in both the PNS and CNS (Lo et al., 1991; Guillemot and Joyner, 1993; Guillemot et al., 1993). Within the PNSMash1 expression is restricted to autonomic progenitors (Lo et al., 1991). More recently, we have shown that a novelatonal-related gene, neurogenin (now calledngn1), is, conversely, expressed in sensory but not autonomic ganglia in the PNS (Ma et al., 1996). Thus, just as the proneural genes ac-sc and ato define distinct neuronal sublineages in Drosophila, Mash1, andngn1 define two major neuronal sublineages within the mammalian PNS.

To obtain further insights into the functions of Mash1 andngn1 in the CNS as well as the PNS, we have compared directly the expression patterns of ngn1, Mash1, and several other genes by single-color or double-color in situ hybridization to adjacent sections. We find that in many embryonic CNS regions ngn1 and Mash1 are expressed in complementary domains that exhibit adjacent and nonoverlapping boundaries, suggesting that they are involved in the development of distinct neuronal populations. Within the PNS, moreover, lineages expressing either ngn1 or Mash1subsequently express other bHLH genes, such as NSCL1 andeHAND with similar lineal restrictions, suggesting that different classes of peripheral neurons may be specified by complementary cascades of bHLH proteins. Finally, in the CNS, expression of ngn1 and Mash1 is associated closely with that of two vertebrate Notch ligands, Delta-1(Dll-1) (Bettenhausen et al., 1995) and/or Jagged(Lindsell et al., 1995). This overlap is consistent with a potential functional interaction between these two sets of proteins during neuronal fate determination, as demonstrated for their homologs inDrosophila and Xenopus (Ghysen et al., 1993;Chitnis and Kintner, 1996; Ma et al., 1996).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In situ hybridization. Digoxigenin-labeledin situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Groves et al., 1994) with the following probes: ngn1 (Ma et al., 1996), Mash1 (Lo et al., 1991), Dll-1 (from Domingos Henrique), Jagged (Lindsell et al., 1995),eHAND (Cserjesi et al., 1995), and NSCL1 (Begley et al., 1992). For double-color in situ hybridizationngn1 and Dll-1 were labeled with digoxigenin-UTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN), whereasMash1 and Jagged were labeled with fluorescein-UTP (Boehringer Mannheim). A detailed procedure is available on request.

RESULTS

Complementary cascades of bHLH gene expression in the PNS

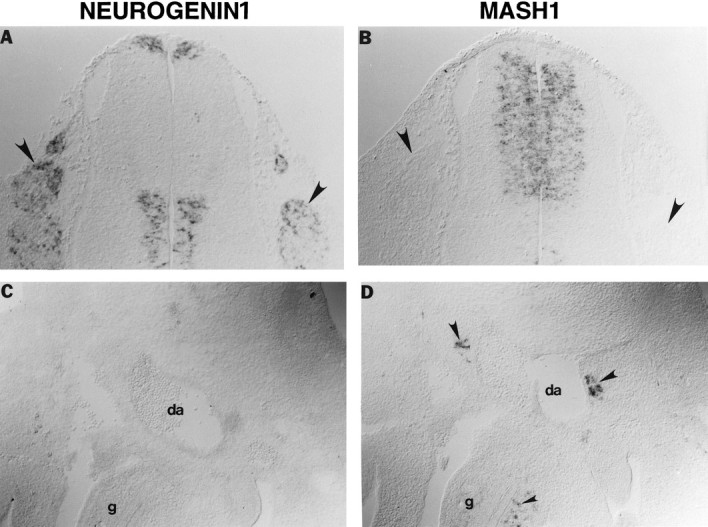

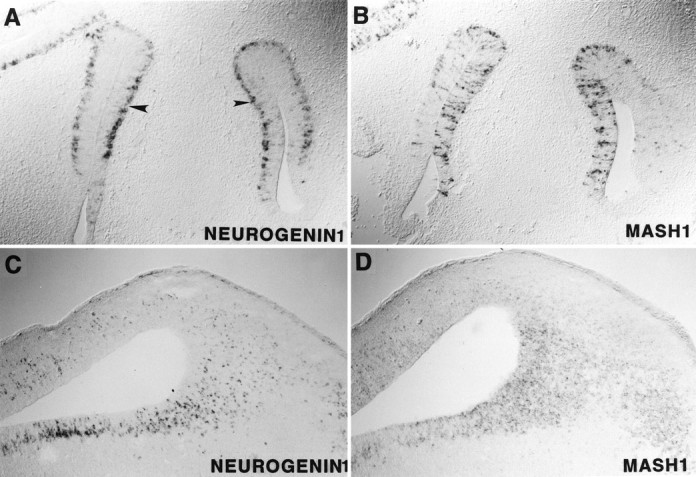

Previously, we reported in separate studies that MASH1 protein is expressed in peripheral autonomic but not sensory ganglia (Lo et al., 1991) and that ngn1 mRNA is expressed, conversely, in early sensory but not autonomic ganglia (Ma et al., 1996). To confirm this apparent mutual exclusivity of expression in the PNS, we performed a series of in situ hybridization experiments withMash1 and ngn1 probes on adjacent serial sections of rat embryos of various ages. At embryonic day (E) 13.5,ngn1 mRNA was detected in a subset of cells in the dorsomedial margins of the DRG (Fig.1A, arrowheads), whereas noMash1 transcripts were detected in this region (Fig.1B, arrowheads). Conversely, at E12.5Mash1 mRNA was detected easily in forming sympathetic and enteric ganglia (Fig. 1D, large andsmall arrowheads, respectively), whereas no ngn1mRNA was detectable in this region on adjacent sections (Fig.1C). Similar observations were made in embryos of other ages (data not shown), indicating that this apparent reciprocity is not a function of developmental stage. The mutual exclusivity of expression in the PNS extended to cranial sensory ganglia; ngn1 mRNA was detected in trigeminal ganglia (Fig. 2C,TG), the otic epithelium (small arrow), and the acoustic component of the facio–acoustic complex (large arrow), whereas none of these structures expressedMash1 (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 1.

Complementary expression of ngn1and Mash1 during development of the PNS. Shown are adjacent transverse sections through the trunk region of E13.5 (A, B) or E12.5 (C, D) rat embryos. ngn1is expressed in DRG (A,arrowhead) in which Mash1 is not expressed (B, arrowhead). Conversely, Mash1 is expressed in sympathetic ganglia adjacent to the dorsal aorta (da) (D,large arrowheads) and enteric ganglia (gut,g) (D, small arrowhead), none of which express ngn1(C). Mutual exclusivity betweenMash1 and ngn1 also is observed in the ventricular zone of the spinal cord (A,B; see also Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

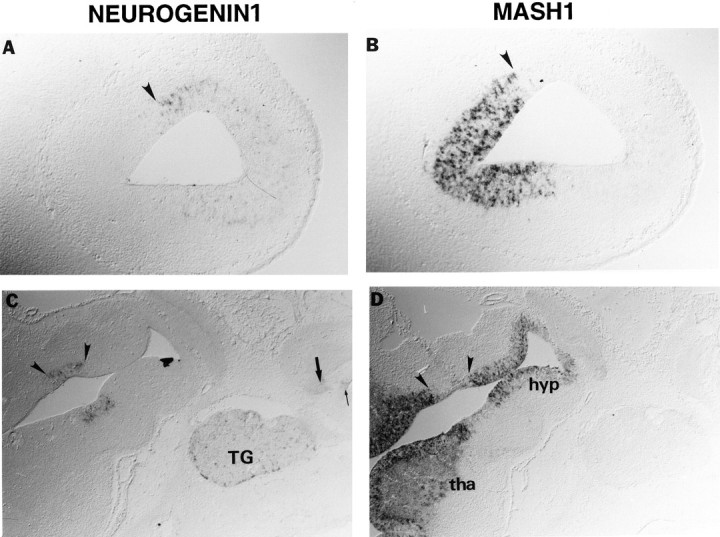

Mutual exclusivity of ngn1 andMash1 expression in forebrain and cranial sensory ganglia. Transverse sections through the developing olfactory lobe (A, B, in high magnification) and the diencephalon (C, D) of an E14.5 rat embryo. ngn1 is expressed in the dorsal/rostral side of the olfactory lobe (A), whereas Mash1 is expressed in the ventral/caudal side (B).Mash1 is expressed throughout the hypothalamus (hyp) and the thalamus (tha) except for a narrow region (D) in which ngn1 is expressed (C, arrowheads).ngn1 is expressed in the trigeminal ganglion (C, TG), the acoustic component of the facio–acoustic complex (C, large arrow), and the otic epithelium (C, small arrow), none of which express Mash1 (D). Expression of neurogenin1 in these cranial ganglia is much stronger in younger embryos (Sommer et al., 1996).

Several other bHLH genes have been isolated that exhibit complementary expression in the PNS similar to that observed for Mash1 andngn1. For example, NSCL1 and NSCL2, both related to the lymphoid-specific gene SCL (Porcher et al., 1996), were reported to be expressed in sensory but not autonomic ganglia (Begley et al., 1992; Göbel et al., 1992), as wasNeuroD (Lee et al., 1995); eHAND/Thing1/Hxt(hereafter referred to as eHAND) was, conversely, reported to be expressed in autonomic but not sensory ganglia (as well as in smooth muscle) (Cross et al., 1995; Cserjesi et al., 1995; Hollenberg et al., 1995). These observations raised the question of the temporal relationship between expression of these other bHLH genes and that ofMash1 and ngn1.

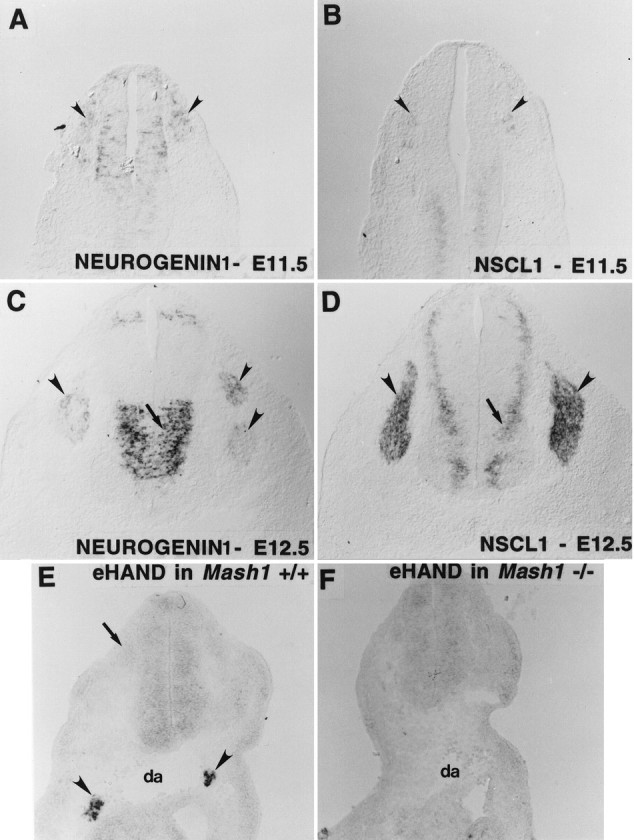

In trunk sensory ganglia early expression of both ngn1 andNSCL1 expression is detected at E11.5 (Fig.3A,B,arrowheads). However, at this age, expression of the former gene is stronger and is detected in more cells than that of the latter (compare Fig. 3A,B). Conversely, at E12.5 expression of ngn1 has begun to decline (Fig.3C, arrowheads), whereas that of NSCL1has increased (Fig. 3D, arrowheads). These data suggest that expression of NSCL1 follows or persists longer than that of ngn1. In support of the former interpretation,ngn1 mRNA at E12.5 is expressed most strongly in cells at the dorsomedial margins of the ganglia in which precursors are located; conversely, NSCL1 mRNA is expressed strongly in interior regions of the ganglia in which differentiated neurons are present (compare Fig. 3D). These data suggest that ngn1expression precedes that of NSCL1 during sensory neurogenesis. In the CNS, ngn1 expression also precedes that of NeuroD (Ma et al., 1996; Sommer et al., 1996). In the PNS, however, we did not observe a temporal difference betweenngn1 and NeuroD expression during early stages of DRG development (data not shown). Therefore, NSCL1 seems to be the latest expressed of the three bHLH genes we examined during sensory neurogenesis.

Fig. 3.

Lineage-specific bHLH cascades within the PNS. Both ngn1 and NSCL1 are expressed in rat DRG at E11.5 and E12.5 (A–D,arrowheads). NSCL1 expression is relatively weak at E11.5 (B, arrowheads) but strong at E12.5 (D, arrowheads).ngn1 expression at E12.5 has begun to fade in the ventral half of the DRG (C, arrowheads). Expression of NSCL1 is displaced more laterally from the ventricular zone (D, arrow) than that ofngn1 (C, arrow).eHAND is expressed in the sympathetic ganglia of E10.5 mouse embryo (E, arrowheads) but not in the sensory ganglia (E, arrows). Expression of eHAND in the sympathetic ganglia is undetectable in Mash1 knock-out mice of similar age (F).

In the case of autonomic ganglia, we wished to know the relationship between the expression of eHAND and that ofMash1. However, we were unable to detect any temporal separation between the expression of these two bHLH genes in sympathetic ganglia (Fig. 3E; data not shown). Therefore, to ask whether expression of eHAND is dependent onMash1 function, we examined its expression inMash1 knock-out mice (Guillemot et al., 1993). NoeHAND mRNA was detected in the sympathetic anlagen of these mutant embryos (Fig. 3F). This does not simply reflect an absence of neural crest-derived cells from these ganglion primordia, however, because we have shown previously that immature sympathetic neuron precursors are present in such mutant embryos (Sommer et al., 1995). These data, therefore, indicate that in autonomic ganglia eHAND expression requires that ofMash1. This, in turn, suggests that eHAND is expressed either downstream of, or cross-regulated by, MASH1. However,Mash1 expression is not sufficient for expression ofeHAND, as seen in the dorsal spinal cord whereMash1, but not eHAND, is expressed (compare Figs.1B, 3E).

Mutually exclusive domains of Mash1 andngn1 expression in the CNS

The foregoing observations of mutually exclusive bHLH gene expression in the PNS raised the question of whether this was true in the CNS as well. As detailed below, the results indicate that expression of Mash1 and ngn1 subdivides many regions of the ventricular zone into adjacent and nonoverlapping domains. At E13.5, for example, ngn1 is expressed in two zones that run the length of the spinal cord, a thin one close to the roof plate and a broad one in the ventral half (Fig.1A). Mash1, conversely, appears to be expressed between these two ngn1 stripes (Fig.1B). Double-label in situ hybridization to sagittal sections (passing through the ventricular zone of the spinal cord) indicated that the boundaries of Mash1 andngn1 expression are adjacent and nonoverlapping (Fig.4B). The combined expression ofMash1 and ngn1 accounts for essentially the entire ventricular zone of the spinal cord, with the exception of a small dorsal region in which Math1 is expressed (Akazawa et al., 1995) and the floorplate.

Fig. 4.

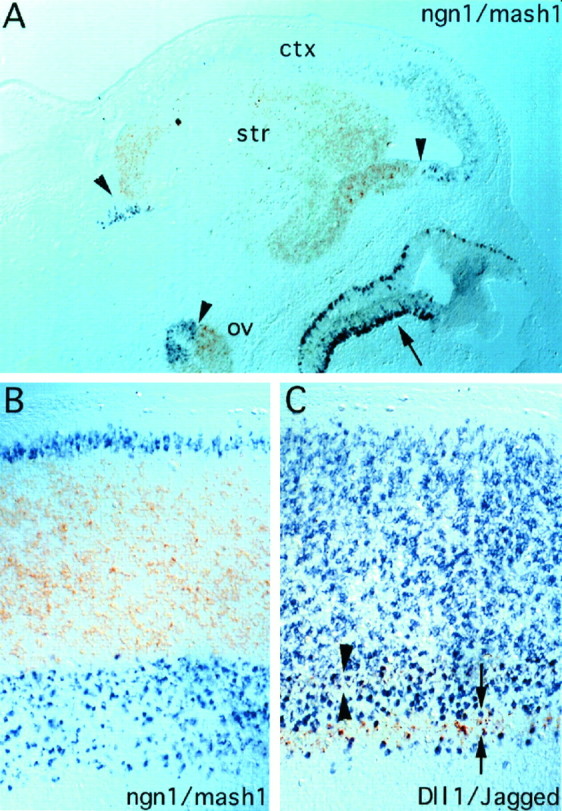

Mutually exclusive expression ofMash1 and ngn1 in spinal cord and forebrain of E14.5 rat embryos demonstrated by double-label in situ hybridization. Shown are sagittal sections of forebrain (A) and spinal cord (B); rostral is to the right, and dorsal is to the top inA and B. B, The section was cut through the ventricular zone, just lateral to the central canal. ngn1 expression is visualized with thepurple chromogen and Mash1 expression with the brown. A, The borders betweenngn1 and Mash1 expression are indicated by arrowheads. ngn1 is expressed in the presumptive cortex (ctx), and Mash1 is expressed in the striatum (str). Complementarity also is seen in optic vesicle (ov). Mash1 andngn1 are expressed in a partially overlapping manner in the olfactory epithelium (arrow; see also Fig. 5).B, The boundaries between Mash1 andngn1 expression are adjacent and nonoverlapping.C, Sagittal section through spinal cord adjacent to that shown in B, double-labeled with probes forJagged (brown) and Dll-1(purple). Double arrowheadsdemarcate the top stripe of Jagged mRNA expression (compare Fig. 6B,arrow), and double arrows demarcate the bottom stripe (compare Fig. 6B,arrowhead). The top stripe of Jagged mRNA (double arrowheads) partially overlaps the ventral boundary of the major dorsal Dll-1 expression domain (compare Fig. 6D, arrow), although it is not possible to determine at this level of resolution whether individual cells coexpress both genes. The ventral stripe ofJagged mRNA (compare Fig. 6B,arrowhead) appears perfectly interdigitated between the two stripes of Dll-1 mRNA (compare Fig.6D, arrow andarrowhead). Note that the boundaries ofJagged and Dll-1 do not correspond to those of Mash1 and ngn1; however,Jagged is expressed only in thengn1-expressing region (see also Fig. 6).

Similarly, in the telencephalon, Mash1 is expressed in the presumptive basal ganglia (Fig. 4A, str), whereas ngn1 is expressed in the presumptive cortex (ctx), as is the related gene ngn2 (Gradwohl et al., 1996; Sommer et al., 1996). Double labeling again revealed that the boundaries between the telencephalic expression domains ofngn1 and Mash1 are adjacent and nonoverlapping (Fig. 4A, arrowheads). A similar mutual exclusivity was observed elsewhere in the forebrain. For example, within the prospective olfactory lobes, ngn1 is expressed in the dorsal part (Fig. 2A), whereas Mash1mRNA is detected in the ventral regions (Fig. 2B). In the diencephalon Mash1 is expressed throughout the ventricular zone, with the exception of a small region (Fig.2D, arrowheads) in which ngn1is expressed instead (Fig. 2C). Such mutual exclusivity also is seen within the optic vesicle (Fig. 4A,arrowhead and ov).

In addition to this striking complementarity of Mash1and ngn1 expression, we also observed some CNS regions that express both genes, including the olfactory epithelium (Fig.5A,B), midbrain (Fig. 5C,D), and (at early stages (E11.5–E12.5)) the ventral spinal cord (data not shown). Within these regions of overlap, differences in the expression pattern of the two genes are, nevertheless, evident. For example, in the E14.5 olfactory epithelium, ngn1 expression is restricted to cells located in the basal layer (Fig. 5A), whereas Mash1 is expressed in cells that span the epithelium (Fig. 5B). In the midbrain the domain of highest ngn1 expression appears displaced laterally from the ventricular wall, whereas that ofMash1 fills the entire ventricular zone (compare Fig.5C,D). Moreover, expression ofMash1 appears relatively uniform (Fig. 5D), whereas that of ngn1 is restricted to a subset of cells (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Overlapping but sequential expression ofngn1 and Mash1. Transverse sections through the olfactory epithelium (A,B) and sagittal sections through the midbrain region (C, D) of an E14.5 rat embryo are illustrated. ngn1 is expressed in cells located in the basal layer of the olfactory epithelium (A,arrowhead), whereas Mash1 is expressed in cells spanning the epithelium (B). In the midbrainngn1 expression is scattered (C), whereas that of Mash1 is much more uniform (D). Also, ngn1 expression (but not that ofMash1) is displaced laterally from the ventricular wall (C, D).

Relationship of Mash1 and ngn1 expression to that of Delta and Jagged

In Drosophila the proneural genes ac-sc both activate expression of the lateral inhibitory signal Deltaand are, in turn, repressed by signaling through Notch, a receptor forDelta (Ghysen et al., 1993). Similarly, in Xenopus X-ngnr-1 activates expression of X-Delta-1 and is negatively regulated by signaling through X-Notch-1 (Ma et al., 1996). Recently, two mammalian Notch ligands, Dll-1 andJagged, have been identified (Bettenhausen et al., 1995;Lindsell et al., 1995). To determine whether MASH1 and/or Neurogenin1 similarly might activate expression of these Notch ligands in mammals, we compared their expression with that of Dll-1 andJagged.

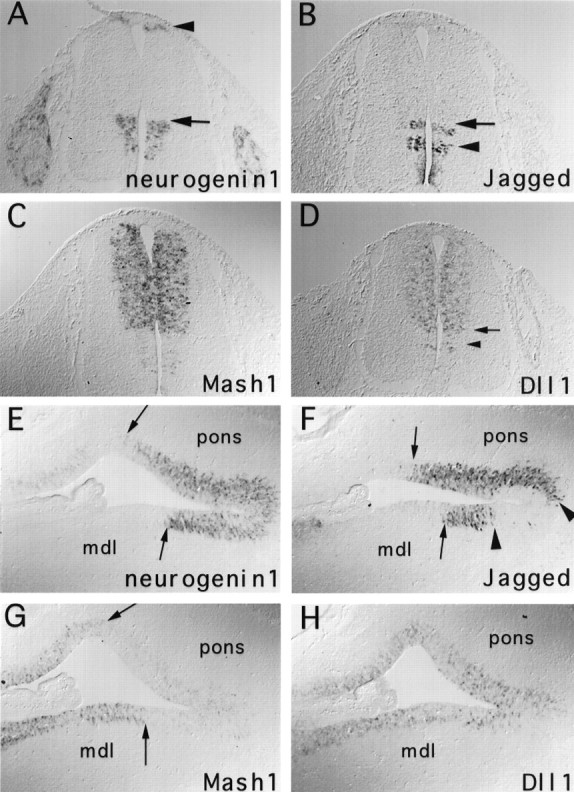

In the spinal cord at E13.5, Jagged is expressed primarily in the ventral region in several narrow longitudinal (i.e., rostrocaudal) stripes that appear as bands across the ventricular zone in transverse sections (Fig. 6B,arrow; see also Lindsell et al., 1995). Comparison of adjacent sections indicates that these bands lie within the region in which ngn1 also is expressed (compare Fig.6A,B; see also Fig.4B,C). Moreover, the top band ofJagged mRNA expression (Fig. 6B,arrow) appears well correlated with the dorsal boundary of the band of ngn1 expression (Fig. 6A,arrow). In contrast to Jagged, Dll-1is expressed primarily in the prospective alar (dorsal) region of the spinal cord (Fig. 6D; see also Bettenhausen et al., 1995; Lindsell et al., 1996) in a domain that encompasses the entire band of Mash1 expression (Figs. 4C,6C). Double-label in situ hybridization confirms that some boundaries of Jagged and Dll-1expression, like those of Mash1 and ngn1, are mutually exclusive (Fig. 4C, arrows), confirming previous observations made in rat (Lindsell et al., 1996) and chick (Myat et al., 1996). However, the dorsal stripe of Jaggedexpression (Fig. 6B, arrow) overlaps the ventral boundary of Dll-1 expression (Fig.6D, arrow), as confirmed by double-labeling on sagittal sections (Fig. 4C,arrowheads), so that the complementarity of Notch ligand expression in the spinal cord is not perfect.

Fig. 6.

Comparisons of Mash1 andngn1 expression to that of Dll-1 andJagged. Adjacent transverse trunk sections of E13.5 (A–D) and sagittal sections through the medulla and pons of E14.5 (E–H) rat embryos are illustrated. The dorsal boundary of the Jagged stripe (B, arrow) seems to correspond to the dorsal boundary of the ventral ngn1 expression domain (A, arrow). The dorsalDll-1 expression domain (D) encompasses that of Mash1 (C) and extends both dorsally to the region expressing the dorsal ngn1 stripe (A, arrowhead) and ventrally into the area corresponding to the top part of the ventralngn1 stripe (A). In the medulla (mdl) and pons (pons), complementarity between ngn1 and Mash1 is indicated by the arrows (E,G). Expression of Jagged is restricted to the region in which ngn1 is strongly expressed (F), whereas Dll-1 is expressed throughout the ventricular zone (H).Jagged expression in this region is discontinuous (F, arrowheads), as in the spinal cord (B).

Although both Mash1 and ngn1 andJagged and Dll-1 exhibit complementary boundaries of expression in the spinal cord, comparison of adjacent sections indicates that these boundaries are located in distinct regions. For example, Dll-1 expression (Fig. 6D) extends dorsally past the top boundary of the Mash1 band (Fig. 6C) to encompass the thin stripe of ngn1expression adjacent to the roof plate (Fig. 6A,arrowhead; compare Fig. 4B vsC). Furthermore, the ventral boundary of Dll-1expression (Fig. 6D, arrow) overlaps the top part of the ventral band of ngn1 expression (Fig.6A, arrow). Thus, expression ofDll-1 is detected in both Mash1- andngn1-expressing regions. Interestingly, however,Jagged expression is detected only in regions that expressngn1 (compare Fig. 6A vsB).

The correlation between Jagged and ngn1expression observed in the spinal cord seems to extend to other regions of the CNS. For example, in the ventricular zone of the medulla and pons Jagged expression is restricted primarily to the region that also expresses high levels of ngn1 (compare Fig.6E vs F). By contrast, in this brainstem region Dll-1 is expressed in a pattern that overlaps the expression domains of both Mash1 andngn1 (compare Fig. 6H vsE,G). Similarly, in the telencephalon strong Dll-1 expression is found in both the striatum, which expresses Mash1, and in the cortex, which expresses ngn1 (Lindsell et al., 1996) (data not shown). By contrast, strong expression of Jagged in the brain is observed only in regions in which ngn1 (or ngn2;Gradwohl et al., 1996; Sommer et al., 1996) is strongly expressed, although faint expression can be seen in some regions that only expressMash1 (such as in the striatum). Thus, a generalization that emerges from these studies is that in the CNS Jaggedexpression is associated primarily with that of ngn1, whereas Dll-1 expression can be associated with that of either ngn1 or of Mash1.

DISCUSSION

Mutual exclusivity of Mash1 and neurogeninsexpression during mammalian neurogenesis

The most striking finding to emerge from the present studies is that Mash1 and ngn1 are expressed in complementary domains, which exhibit adjacent and nonoverlapping boundaries, in many regions of the CNS. In several regions of the CNS the complementary domains delineated by Mash1 andngn1 expression correspond to future functional subdivisions: in the spinal cord to the alar and basal regions and in the forebrain to the cortex and striatum. This mutual exclusivity mirrors the complementarity of expression of these bHLH genes in the PNS, in which Mash1 is expressed by autonomic andngn1 by sensory progenitors.

Recently, we reported the isolation of two otherngn1-related genes, ngn2 and ngn3(Sommer et al., 1996). In the PNS ngn2 also is restricted to sensory lineages, such as in DRG and several epibranchial placode-derived ganglia in which Mash1 is not expressed (Sommer et al., 1996). In the CNS, particularly in the forebrain region, expression of ngn2 (also known as Math4A;Gradwohl et al., 1996) shows a similar regional restriction like that of ngn1 (Sommer et al., 1996) and appears complementary to that of Mash1 (Gradwohl et al., 1996). By contrast,ngn3 is expressed only in extremely restricted regions of the CNS. For example, in the spinal cord ngn3 expression is restricted to the region close to the floorplate (Sommer et al., 1996). Thus, much of the developing CNS can be divided into regions that express either Mash1 or one or more of thengns.

In the PNS the complementary expression of Mash1 and thengns appears to be reflected in the expression of several additional bHLH genes that may serve as potential downstream targets. Expression of NeuroD (Lee et al., 1995; Ma et al., 1996;Sommer et al., 1996) and NSCL1 (Begley et al., 1992) (Fig.3C,D) is restricted to the sensory lineage, whereas eHAND expression is restricted to autonomic lineages (Cserjesi et al., 1995). The finding that Mash1 function is necessary for expression of eHAND in sympathetic ganglia indicates that eHAND is likely a direct or an indirect target of Mash1. In Xenopus a homolog of the ngns,X-ngnr-1, activates expression of X-NeuroDin a unidirectional cascade during primary neurogenesis (Ma et al., 1996). Similarly, X-NeuroD has been shown to activate expression of Xenopus NSCL (J. Lee, personal communication). Our in situ data (Fig. 2A–D;Sommer et al., 1996) are consistent with the idea that thengns, neuroD, and NSCL1 may function in cascade during sensory neurogenesis in higher vertebrates, as well. Confirmation of this will, however, await loss-of-function analyses inngn1 and/or ngn2 knock-out mice.

Functional significance of complementary bHLH gene expression during neurogenesis

Why are different classes of bHLH genes used to promote neurogenesis in different regions of the CNS and PNS? The answer to this question is likely to relate to differences in the functions of these genes. In the Drosophila PNS, atonal (which is structurally related to the ngns) is required for development of chordotonal organs, whereas achaete-scute is required for that of external sensory (es) organs (Jan and Jan, 1994). These genes are not functionally interchangeable, and recent data indicate that the key amino acid residues responsible for these functional differences lie in the basic region and likely mediate protein–protein rather than protein–DNA interactions (Chien et al., 1996). Thus in Drosophila structural differences among different neural bHLH proteins account for their ability to promote the determination of particular neural cell types, and the same is likely to be true in vertebrates. The noninterchangeable functions of different classes of neural bHLH proteins indicate that the choice of a neural (or neuronal) fate is coupled to the specification of a particular cell identity from the earliest developmental stages. However, a given bHLH gene is not sufficient to specify a particular neural cell type, because in both Drosophila and vertebrates individual bHLH genes are required for the development of more than one class of neurons. A single bHLH gene is, therefore, likely to act in combination with other region-specific transcriptional regulators in the pathways that determine neuronal identities. This would explain why, for example, expression of Mash1 is followed by that ofeHAND in the PNS, but not the CNS.

Overlapping expression of Mash1and ngns

Although spatial complementarity between expression ofMash1 and ngns seems to be the rule in most parts of the CNS, there are some regions in which these genes are coexpressed. For example, Mash1, ngn1, andngn2 all are expressed in the midbrain region (Fig.5C,D; data not shown). Other sites ofngn1 and Mash1 coexpression include the olfactory epithelium and midbrain. Interestingly, within these overlapping regions differences in the expression of these genes are clearly seen. For example, in the olfactory epithelium ngn1 expression is restricted to the basal layer, whereas Mash1 expression spans the epithelium. Conversely, in the midbrain Mash1 is expressed in the ventricular zone, whereas both ngn1 andngn2 are displaced slightly lateral to this region (Fig.5C,D; data not shown). These differences suggest that even in these regions of overlap these genes may function at different developmental stages in the same cells or in distinct but intermingled groups of cells that develop on different schedules.

Relationship of bHLH gene expression to that of Notch ligands

Previously, it has been shown that the Notch ligandsc-Delta-1 and c-Serrate-1 (a chick homolog ofJagged) and Delta-1 (Dll-1) andJagged (Lindsell et al., 1996; Myat et al., 1996) exhibit complementary domains of expression in the spinal cord of chick and rat, respectively. In the chick this complementarity seems perfect. Our data indicate that it is partially lost in rat, however (Fig. 6). Because Jagged and Dll-1 are both ligands for Notch, they may be functionally equivalent. In that case, there would be little selection pressure to maintain such perfect complementarity. The bHLH genes Mash1 and ngn1 also exhibit complementary boundaries of expression in the rodent spinal cord. In the fly and the frog, homologs of these genes are demonstrably not functionally equivalent (Chien et al., 1996; Chitnis and Kintner, 1996;Ma et al., 1996). There may, therefore, be more selection pressure to maintain the complementarity of bHLH gene expression within the CNS. Analysis of the expression patterns of the chick homologs of these genes should be informative in this respect.

The side-by-side comparison of bHLH and Notch ligand gene expression presented here indicates that the boundaries of Jagged andDll-1 expression do not correspond precisely to the boundaries between the domains of Mash1 and ngn1expression (Figs. 4B,C, 6). Specifically, Dll-1 is expressed in domains expressing either Mash1 or ngn1. On the other hand, high-level Jagged expression usually is (but not always) associated with that of ngn1. If, indeed, Jaggedand Dll-1 are functionally equivalent, it is not clear why expression of Jagged should be associated preferentially with that of ngn1. This apparent linkage may reflect regulatory rather than functional constraints on the two genes.

The fact that the expression of the bHLH genes and that of the Notch ligands overlaps in the ventricular zone in both space and time raises the possibility that there is a regulatory interaction between these proteins in higher vertebrates, similar to that which occurs inDrosophila and Xenopus (Chitnis et al., 1995;Chitnis and Kintner, 1996; Ma et al., 1996) (for review, see Lewis, 1996). Specifically, proneural genes in the fly and X-ngnr-1in the frog have been shown to activate expression of Deltaand its Xenopus homolog, X-Delta-1, respectively. Our data are compatible with the idea that such an activation occurs in rodents as well, as suggested previously (Kunisch et al., 1994) (for review, see Lewis, 1996). Nevertheless, in Mash1 knock-out mice, expression of Dll-1 and Jagged in the CNS is not affected (our unpublished results), consistent with the failure to detect any other phenotypic defects in the CNS of these embryos (Guillemot et al., 1993). This may reflect functional redundancy or compensation between Mash1 and other unrelated bHLH genes; alternatively, Notch ligands may not be regulated by Mash1in mice. Similarly, in the case of ngn1 and ngn2, the overlap in their CNS expression may obscure defects in Notch ligand expression in single knock-out mice. Analysis of mice containing targeted mutations in both genes should, however, be informative.

Footnotes

Q.M. and L.S. are Associates of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; D.J.A. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We are grateful to Gerry Weinmaster for providing theJagged probe, to Domingos Henrique for the mouseDll-1 probe, to Richard Baer for the mouseNSCL1 probe, to Eric Olson and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments, and to Tetsu Saito for the double-labelin situ hybridization protocol.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. David J. Anderson at the above address.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akazawa C, Ishibashi M, Shimizu C, Nakanishi S, Kageyama R. A mammalian helix-loop-helix factor structurally related to the product of Drosophila proneural gene atonal is a positive transcriptional regulator expressed in the developing nervous system. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8730–8738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begley CG, Lipkowitz S, Gobel V, Mahon KA, Bertness V, Green AR, Gough NM, Kirsch IR. Molecular characterization of NSCL, a gene encoding a helix-loop-helix protein expressed in the developing nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:38–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bettenhausen B, Hrabe de Aggelis M, Simon D, Guenet JL, Gossler A. Transient and restricted expression during mouse embryogenesis of Dll-1, a murine gene closely related to Drosophila Delta. Development (Camb) 1995;121:2407–2418. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brand M, Jarman AP, Jan LY, Jan Y-N. asense is a Drosophila neural precursor gene and is capable of initiating sense organ formation. Development (Camb) 1993;119:1–17. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.Supplement.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chien C-T, Hsia C-D, Jan LY, Jan Y-N. Neuronal type information encoded in the basic helix-loop-helix domain of proneural genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13239–13244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chitnis A, Kintner C. Sensitivity of proneural genes to lateral inhibition affects the pattern of primary neurons in Xenopus embryos. Development (Camb) 1996;122:2295–2301. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.7.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chitnis A, Henrique D, Lewis J, Ish-Horowicz D, Kintner C. Primary neurogenesis in Xenopus embryos regulated by a homologue of the Drosophila neurogenic gene Delta. Nature. 1995;375:761–766. doi: 10.1038/375761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cross JC, Flannery ML, Blanar MA, Steingrimsson E, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Rutter WJ, Werb A. Hxt encodes a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor that regulates trophoblast cell development. Development (Camb) 1995;121:2513–2523. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cserjesi P, Brown D, Lyons GE, Olson EN. Expression of the novel basic helix-loop-helix gene eHAND in neural crest derivatives and extraembryonic membranes during mouse development. Dev Biol. 1995;170:664–678. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghysen A, Dambly-Chaudiere C, Jan LY, Jan Y-N. Cell interactions and gene interactions in peripheral neurogenesis. Genes Dev. 1993;7:723–733. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Göbel V, Lipkowitz S, Kozak CA, Kirsch IR. NSCL2, a basic domain helix-loop-helix gene expressed in early neurogenesis. Cell Growth Differ. 1992;3:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gradwohl G, Fode C, Guillemot F. Restricted expression of a novel murine atonal-related bHLH protein in undifferentiated neural precursors. Dev Biol. 1996;180:227–241. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groves AK, George KM, Tissier-Seta J-P, Engel JD, Brunet JF, Anderson DJ. Differential regulation of transcription factor gene expression and phenotypic markers in developing sympathetic neurons. Development (Camb) 1995;121:887–901. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.3.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillemot F, Joyner AL. Dynamic expression of the murine achaete-scute homologue Mash1 in the developing nervous system. Mech Dev. 1993;42:171–185. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90006-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guillemot F, Lo L-C, Johnson JE, Auerbach A, Anderson DJ, Joyner AL. Mammalian achaete-scute homolog-1 is required for the early development of olfactory and autonomic neurons. Cell. 1993;75:463–476. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollenberg SM, Sternglanz R, Cheng PF, Weintraub H. Identification of a new family of tissue-specific basic helix-loop-helix proteins with a two-hybrid system. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3813–3822. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jan Y-N, Jan LY. HLH proteins, fly neurogenesis, and vertebrate myogenesis. Cell. 1993;75:827–830. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90525-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jan Y-N, Jan LY. Genetic control of cell fate specification in the Drosophila peripheral nervous system. Annu Rev Genet. 1994;28:373–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.28.120194.002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarman AP, Grau Y, Jan LY, Jan Y-N. atonal is a proneural gene that directs chordotonal organ formation in the Drosophila peripheral nervous system. Cell. 1993;73:1307–1321. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90358-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JE, Birren SJ, Anderson DJ. Two rat homologues of Drosophila achaete-scute specifically expressed in neuronal precursors. Nature. 1990;346:858–861. doi: 10.1038/346858a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunisch M, Haenlin M, Campos-Ortega JA. Lateral inhibition mediated by the Drosophila neurogenic gene Delta is enhanced by proneural genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10139–10143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JE, Hollenberg SM, Snider L, Turner DL, Lipnick N, Weintraub H. Conversion of Xenopus extoderm into neurons by NeuroD, a basic helix-loop-helix protein. Science. 1995;268:836–844. doi: 10.1126/science.7754368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis J. Neurogenic genes and vertebrate neurogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:3–10. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindsell CE, Shawber CJ, Boulter J, Weinmaster G. Jagged, a mammalian ligand that activates Notch1. Cell. 1995;80:909–917. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindsell CE, Boulter J, diSibio G, Gossler A, Weinmaster G. Expression patterns of Jagged, Delta-1, Notch1, Notch2, and Notch3 genes identify ligand-receptor pairs that may function in neural development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;8:14–27. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo L, Johnson JE, Wuenschell CW, Saito T, Anderson DJ. Mammalian achaete-scute homolog 1 is transiently expressed by spatially restricted subsets of early neuroepithelial and neural crest cells. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1524–1537. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma Q, Kintner C, Anderson DJ. Identification of neurogenin, a vertebrate neuronal determination gene. Cell. 1996;87:43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myat A, Henrique D, Ish-Horowicz D, Lewis J. A chick homologue of Serrate and its relationship with Notch and Delta homologues during central neurogenesis. Dev Biol. 1996;174:233–247. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porcher C, Swat W, Rockwell K, Fujiwara Y, Alt FW, Orkin SH. The T cell leukemia oncoprotein SCL/tal-1 is essential for development of all hematopoietic lineages. Cell. 1996;86:47–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez I, Hernandez R, Modolell J, Ruiz-Gomez M. Competence to develop sensory organs is temporally and spatially regulated in Drosophila imaginal primordia. EMBO J. 1990;9:3583–3592. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sommer L, Ma QF, Anderson DJ. neurogenins, a novel family of atonal-related bHLH transcription factors, are putative mammalian neuronal determination genes that reveal progenitor cell heterogeneity in the developing CNS and PNS. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;8:221–241. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sommer L, Shah N, Rao M, Anderson DJ. The cellular function of MASH1 in autonomic neurogenesis. Neuron. 1995;15:1245–1258. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weintraub H. The MyoD family and myogenesis: redundancy, networks, and thresholds. Cell. 1993;75:1241–1244. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]