Abstract

The formation of a growth cone at the tip of a severed axon is a key step in its successful regeneration. This process involves major structural and functional alterations in the formerly differentiated axonal segment. Here we examined the hypothesis that the large, localized, and transient elevation in the free intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) that follows axotomy provides a signal sufficient to trigger the dedifferentiation of the axonal segment into a growth cone. Ratiometric fluorescence microscopy and electron microscopy were used to study the relations among spatiotemporal changes in [Ca2+]i, growth cone formation, and ultrastructural alterations in axotomized and intact Aplysia californica neurons in culture. We report that, in neurons primed to grow, a growth cone forms within 10 min of axotomy near the tip of the transected axon. The nascent growth cone extends initially from a region in which peak intracellular Ca2+ concentrations of 300–500 μm are recorded after axotomy. Similar [Ca2+]itransients, produced in intact axons by focal applications of ionomycin, induce the formation of ectopic growth cones and subsequent neuritogenesis. Electron microscopy analysis reveals that the ultrastructural alterations associated with axotomy and ionomycin-induced growth cone formation are practically identical. In both cases, growth cones extend from regions in which sharp transitions are observed between axoplasm with major ultrastructural alterations and axoplasm in which the ultrastructure is unaltered. These findings suggest that transient elevations of [Ca2+]ito 300–500 μm, such as those caused by mechanical injury, may be sufficient to induce the transformation of differentiated axonal segments into growth cones.

Keywords: growth cone formation, axotomy, calcium, fura-2, mag–fura-2, neuritogenesis

Axonal transection is followed, in many cases, by a process in which the tip of the severed axon is transformed into a motile growth cone (Shaw and Bray, 1977; Bray et al., 1978; Wessells et al., 1978; Baas and Heidemann, 1986; Baas et al., 1987; Rehder et al., 1992; Benbassat and Spira, 1993; Ashery et al., 1996). This growth cone serves as a path-finding sensor, a cytoskeleton assembly apparatus, and a site for membrane insertion (for review, see Letourneau et al., 1992). The dedifferentiation of the stable, cylindrical axonal segment into a motile, irregularly shaped growth cone is a crucial step in the regeneration of an amputated axon. Yet little is known about the mechanisms that underlie this transformation.

Axotomy causes a large increase of the free intracellular Ca2+ concentration in the transected axon, mainly because of Ca2+ influx through the cut end (Borgens et al., 1980;Happel et al., 1981; Mata et al., 1986; Strautman et al., 1990; Rehder et al., 1991, 1992; Ziv and Spira, 1993, 1995). This influx forms a steep [Ca2+]i gradient along the severed axon, in which Ca2+ concentrations >1 mmare recorded near the cut end. After the formation of a membrane seal over the cut end (Spira et al., 1993), [Ca2+]i rapidly recovers to control levels. Previous studies suggested that this calcium influx induces a gradient of ultrastructural damage or even neuronal death (Schlaepfer, 1974;Meiri et al., 1983; Roederer et al., 1983; Lucas et al., 1985; Emery et al., 1987; Gross and Higgens, 1987; Spira et al., 1993) (see alsoZelena et al., 1968; Ballinger and Bittner, 1980; Gross et al., 1983;Baas and Heidemann, 1986; Krause et al., 1994). However, the relationships between the [Ca2+]i gradient and the ultrastructural alterations have not been determined.

Although axotomy-induced alterations to axonal cytoarchitecture are considered to be pathological in nature, they also may be part of the process in which the affected axonal segment is transformed into a growth cone, a process that most certainly requires significant cytoarchitectural rearrangements. Therefore, if axotomy-associated structural changes are caused by an influx of Ca2+, it is possible that the subsequent formation of a new growth cone is the direct consequence of the axotomy-induced elevation in [Ca2+]i.

In the present study we tested the hypothesis that a transient elevation in [Ca2+]i, such as that caused by axonal transection, may be sufficient to induce the transformation of a differentiated axonal segment into a growth cone. We report that the growth cone formed after axotomy extends initially from a region in which peak intracellular Ca2+ concentrations of 300–500 μm are recorded. Electron microscopy (EM) analysis shows that this region corresponds to a sharp transition zone between axoplasm with major ultrastructural alterations and axoplasm in which the ultrastructure is unaltered. We then show that local and transient elevations of [Ca2+]i to 300–500 μm in intact axons induce ultrastructural alterations identical to those observed after axotomy and lead to the formation of ectopic growth cones, which subsequently develop into elaborate neuritic trees.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures. Neurons B1 and B2 from buccal ganglia of Aplysia californica were isolated and maintained in culture as previously described (Schacher and Proshansky, 1983;Benbassat and Spira, 1993; Ziv and Spira, 1993, 1995; Spira et al., 1996). Briefly, buccal ganglia were isolated and incubated for 1.5–2.5 hr in 1% protease (Sigma type IX) at 35°C. Then the ganglia were desheathed, the cell body of the neurons with their long axons were pulled out with sharp micropipettes, and they were placed on poly-l-lysine-coated (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) glass bottom culture dishes. The culture medium consisted of equal parts of filtered hemolymph from Aplysia fasciata collected along the Mediterranean coast and L-15 supplemented for marine species. All experiments were done 8–48 hr from plating, after the culture medium was replaced with reduced magnesium artificial seawater (ASW) composed of (in mm): NaCl 540, KCl 10, CaCl2 10, MgCl2 2, and HEPES 10, adjusted to pH 7.6. Because mag–fura-2 binds Mg2+ as well as Ca2+, the Mg2+ concentration in this solution was set at 2 mm to match the intracellular free Mg2+concentration (Ziv and Spira, 1995).

Axotomy. Axonal transection was performed as previously described (Benbassat and Spira, 1993, 1994; Spira et al., 1993, 1996) by applying pressure on the axon with the shaft of a micropipette under visual control. Occasionally, gentle forward and backward motions were necessary to complete the sectioning.

Ionomycin application. Ionomycin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), from a stock solution of 10 mm in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), was diluted with ASW to a final concentration of 0.5 mm and focally applied by pressure-ejecting the solution onto the axonal membrane with a micropipette (tip diameter of 2–4 μm). The application process was monitored in real time by fluorescence microscopy, and the ionophore was applied until a noticeable decrease in the fluorescence at 380 nm was observed (2–4 sec), after which the culture dish was perfused with ASW to remove the excess ionomycin from the vicinity of the neuron. Control applications of DMSO in ASW had no effect on axonal morphology or on [Ca2+]i.

Video microscopy. The system used for differential interference contrast (DIC) video microscopy consisted of a Zeiss Axiovert (Oberkochen, Germany) microscope equipped with DIC optics, a long working-distance condenser set for Koehler illumination, and a 100 W halogen light source. The specimens were illuminated for a minimal duration to minimize photodynamic damage. The objectives used were either a Zeiss 20× 0.50 NA Plan-Neofluar or a Zeiss 40× 0.75 NA Plan-Neofluar. In some instances a 4× teleconverter was placed between the projection lens of the microscope and the face plate of the video camera. The images were collected with a Vidicon video camera (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan) and stored during the experiment to a 3/4" video cassette recorder (Sony, Tokyo, Japan). Still images were formed after the experiments by averaging 4–64 video frames with a frame grabber (Imaging Technology, Woburn, MA), followed by the subtraction of an out-of-focus image of a vacant area of the culture dish. The final images were prepared with commercially available software (Adobe Photoshop).

Fura-2 and mag–fura-2 Ca2+ imaging. Fura-2 and mag–fura-2 loading, imaging, and calibrating were done as previously described (Ziv and Spira, 1993, 1995). Briefly, the cell body of each neuron was impaled with a microelectrode containing 2 m KCl and 10 mm fura-2 or mag–fura-2 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and the indicator was loaded iontophoretically or by pressure injection to a final concentration of 25–50 μm. Fluorescence images of the neurons loaded with the fluorescent indicator were taken by real-time averaging of 4–16 video frames at 340 ± 5 and 380 ± 5 nm excitation wavelengths. Background images, obtained at both wavelengths from regions adjacent to the dye-filled neuron, were subtracted from the averaged images. Ratio images of the fluorescent intensities were obtained by dividing each pixel in the 340 nm background-subtracted fluorescence image by the corresponding pixel in the 380 nm one. The ratio values were converted to free intracellular Ca2+ concentrations by means of calibration curves prepared as previously described (Ziv and Spira, 1993, 1995).

The fluorescent microscope system consisted of a Zeiss Axiovert microscope equipped with a 75 W Xenon arc lamp, a Zeiss 40× 0.75 NA Plan-Neofluar objective, 340 ± 5 and 380 ± 5 nm bandpass excitation filters set in a computer-controlled two-position filter changer, a dichroic mirror with a cut-off threshold of 395 nm, a 510 ± 10 nm bandpass emission filter, and computer-controlled electronic shutters (Uniblitz, Vincent Associates, Rochester, NY). The images were collected with a silicon-intensified target (SIT) video camera (Hamamatsu), digitized at 512 × 512 pixels with a PC-hosted frame grabber (Imaging Technology), stored as computer files, and processed with a software package developed in our laboratory.

Electron microscopy. The neurons were fixed by perfusing the culture dish with 10 ml of a fixative solution containing 3% glutaraldehyde in ASW at pH 6.9 (Forscher et al., 1987). After the initial fixation, the culture dishes were removed from the microscope, the fixative solution was substituted several times, and the neurons were incubated in the fixative for an additional 30 min. Then the cells were washed in ASW and cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, post-fixed by 0.5% osmium tetraoxide and 0.8% K3Fe(CN)6, and stained en bloc with aqueous 3% uranyl acetate solution for 30 min. Dehydration was performed via a series of ethanol solutions, and, finally, the neurons were embedded in Agar 100. The blocks were sectioned by a microtome, and thin sections of ∼70 nm were stained by lead citrate, tannic acid, and uranyl acetate.

RESULTS

Correlation between the spatial distribution pattern of [Ca2+]i after axotomy and the site of the growth cone formation

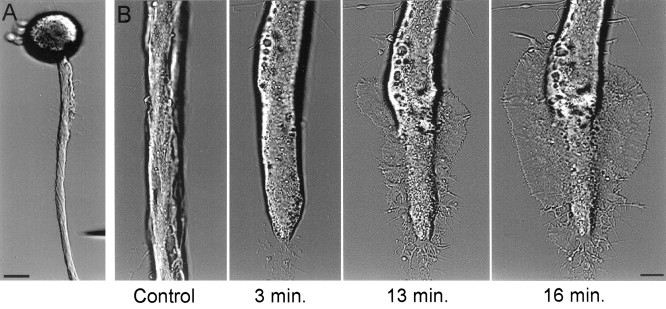

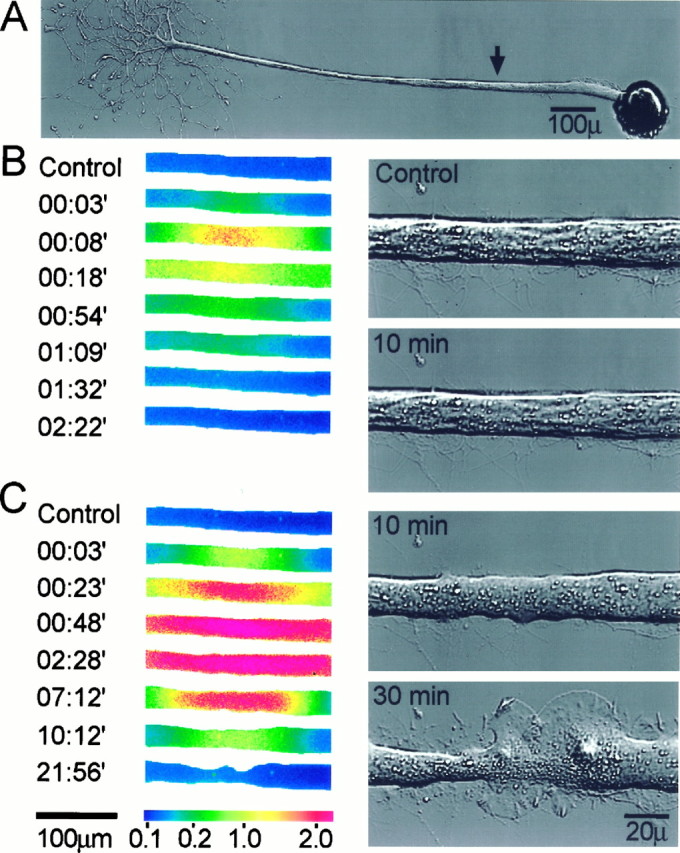

The procedures we use to isolate Aplysia neurons and maintain them in culture promote vigorous outgrowth of new neurites, suggesting that under these conditions the neurons are primed to regrow. Most of this new outgrowth extends from the tip of the main axon, whereas the rest of the original axon remains relatively free of new neurites. In these neurons, axotomy usually is followed by the rapid extension of a growth cone from a region near the cut end of the transected axon (Fig. 1). The formation of this growth cone usually is preceded by several characteristic changes in the morphology of the transected axon. After axotomy the transected axon retracts, and the ruptured membrane at the cut end reseals. During the next 10–20 min, the axonal segment adjacent to the transection site flattens out, its diameter is altered, and many vacuoles form within it (Fig. 1). At 10–30 min from axotomy, a lamellipodium rapidly extends from the affected axonal segment. In most experiments the lamellipodium first appeared near the boundary between the affected axonal segment and the rest of the axon (50–150 μm from the tip of the transected axon), whereas in fewer cases the lamellipodium was observed to extend from the tip of the axon.

Fig. 1.

Axotomy is followed by the rapid formation of a growth cone. A, A low-magnification image of a cultured buccal neuron B1 acquired before axonal transection. The micropipette used for transecting the axon is seen in the bottom right corner. B, After axotomy the morphology of the distal axonal segment was altered, and this was followed by the rapid formation of a growth cone in the form of an extending lamellipodium. Scale bars: A, 50 μm; B, 10 μm.

To study the spatiotemporal relations between axotomy-induced elevations in [Ca2+]i and the site of growth cone formation, we loaded buccal neurons with the low-affinity fluorescent Ca2+ indicator mag–fura-2 (Raju et al., 1989;Ziv and Spira, 1995), we transected their axons at a distance of 150–250 μm from the cell body, and we recorded the resulting alterations in [Ca2+]i during the transection and throughout the recovery process by collecting mag–fura-2 ratio images at a rate of one image every 3 sec. The alterations in axonal morphology were recorded by switching to DIC optics and storing video-enhanced images of the transected axons.

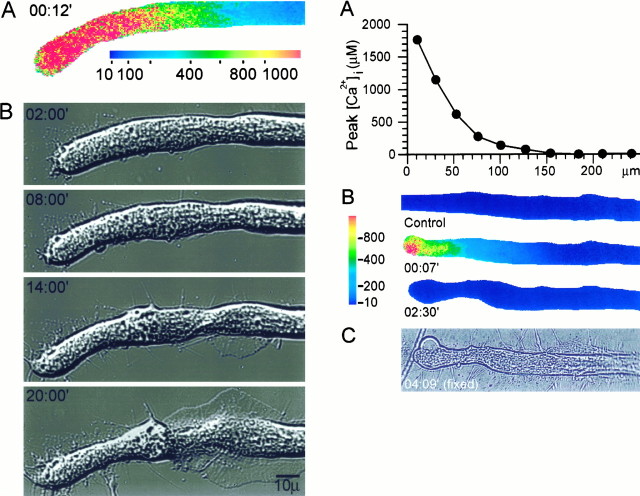

The peak [Ca2+]i recorded at the site from which a growth cone subsequently emerged was found consistently to be 300–500 μm (n > 10), significantly less than the peak Ca2+ concentrations recorded at the very tip of the axon. This is illustrated in the experiment shown in Figure2. Axotomy caused a large increase in [Ca2+]i in the form of a steep [Ca2+]i gradient along the cut axon that exceeded 1 mm near its distal tip (Fig.2A). Within 2 min from axotomy, the intracellular Ca2+ concentration recovered to near-control levels. During the next 10 min, the uniform cylindrical geometry of the axonal segment adjacent to the cut end was deformed (Fig. 2B), as described above. As a rule, these morphological alterations were limited to axonal segments in which [Ca2+]iwas elevated to >300 μm. At 14 min from axotomy, a lamellipodium began to extend from a region ∼100 μm from the cut end. At this distance [Ca2+]i was elevated after axotomy to a maximum of ∼300 μm (Fig. 2, compareA and B).

Fig. 2.

(Left) The correlation between peak [Ca2+]i after axotomy and the site of growth cone formation. A mag–fura-2 ratio image of the spatial distribution of [Ca2+]i at the time at which [Ca2+]i was elevated to its maximal levels (A) is compared with DIC images of the same neuron that show the subsequent formation of the new growth cone (B). [Ca2+]i was elevated to ∼300 μm at the site from which the lamellipodium was first observed to extend. [Ca2+]i is given in μm. Time is given in minutes from axotomy.

It is important to emphasize that the first morphological alterations indicative of growth cone formation are observed only after thecomplete recovery of the elevated [Ca2+]i to control levels (∼100 nm). Because mag–fura-2 is not suitable for resolving micromolar Ca2+ concentrations (Ziv and Spira, 1995), this observation was confirmed by performing similar experiments in which the high-affinity Ca2+ indicator fura-2 was used (data not shown).

Experiments in which axotomy was performed in Ca2+-free ASW never resulted in the formation of a growth cone (data not shown; see also Rehder et al., 1992). However, this does not necessarily imply that the formation of a growth cone after axotomy is triggered by Ca2+ influx, because extracellular Ca2+ is essential for resealing the ruptured membrane at the cut end (Yawo and Kuno, 1985; Gallant, 1988; Xie and Barrett, 1991; Rehder et al., 1992;Ziv and Spira, 1993). To differentiate between the roles of Ca2+ in resealing the ruptured membrane and in inducing growth cone formation, we devised an axotomy procedure that would allow the resealing of the ruptured membrane but would not cause elevations in [Ca2+]i in excess of 100–200 μm along the axon. To that end, axotomy was performed in ASW containing a low concentration of Ca2+ (0.5 mm). After ∼1 min from axotomy, this medium was replaced with ASW containing 1 mm Ca2+. Finally, the medium was replaced with normal ASW (10 mm). In these experiments (n = 5) mag–fura-2 ratio imaging revealed that the free intracellular Ca2+ concentration was elevated transiently along the axon to <100 μm, and then it gradually recovered, reaching preaxotomy levels after the medium was replaced by normal ASW. In contrast to axotomy performed in normal ASW, axotomy performed according to this procedure did not induce the transformation of transected axonal segments into growth cones. The severed axonal segments maintained their original morphology, and no lamellipodia were extended (data not shown).

Correlation between the elevation of [Ca2+]i and the ultrastructural alterations associated with axotomy

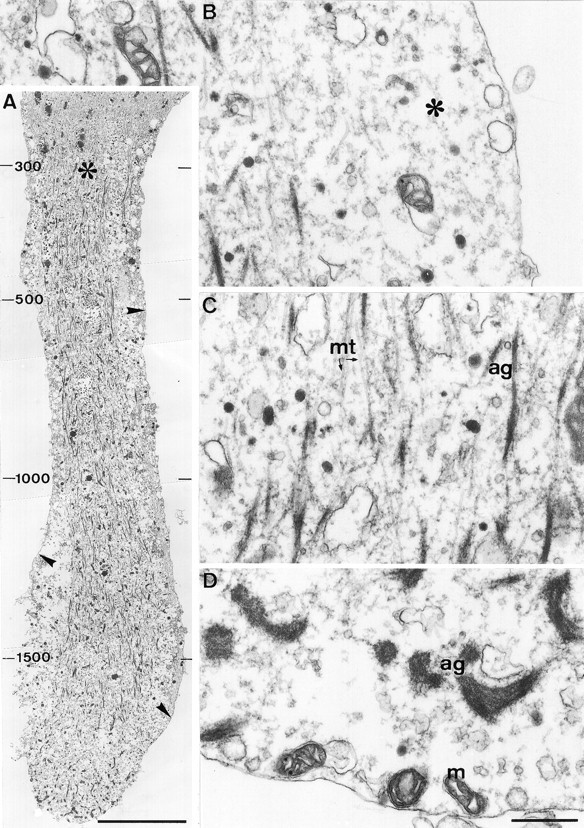

Previous studies reported that ultrastructural alterations associated with axotomy appear in the form of a gradient in which the highest degree of damage occurs near the tip of the cut axon (Ballinger and Bittner, 1980; Gross and Higgens, 1987; Spira et al., 1993). However, the relations between these pathological ultrastructural alterations and the calcium concentration gradient were not determined. To correlate the spatial distribution pattern of [Ca2+]i with the spatial pattern of the ultrastructural modifications postaxotomy, we loaded cultured neurons with mag–fura-2, we transected their axons, and we recorded the alterations in [Ca2+]i caused by axotomy. After the recovery of [Ca2+]i to near-control levels, the neurons were fixed for EM by rapid superfusion with a glutaraldehyde fixation buffer (Benbassat and Spira, 1993).

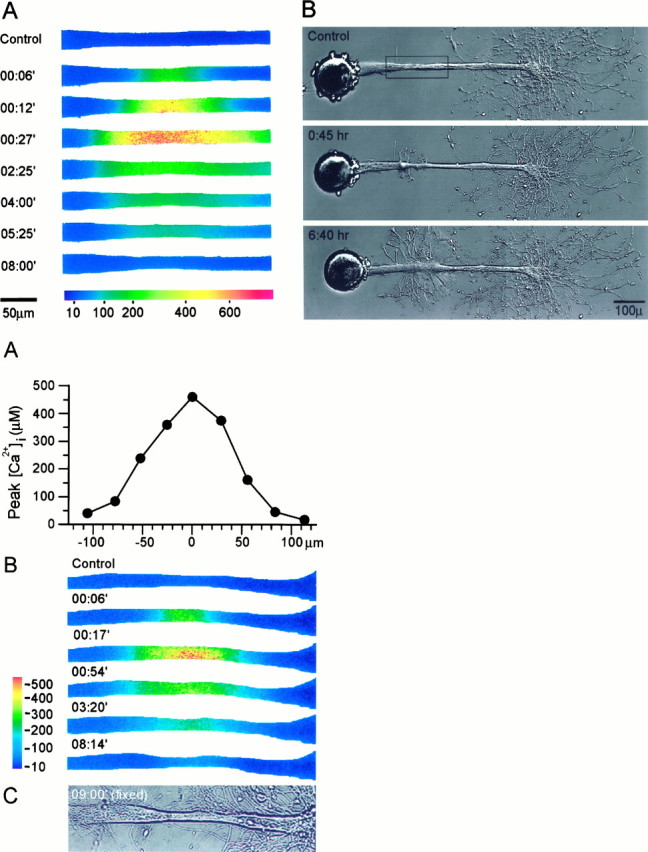

One such experiment (n = 3) is shown in Figure3. As previously described, axotomy caused a large increase in [Ca2+]i that exceeded 1 mm near the tip of the cut axon, forming a gradient of elevated [Ca2+]i along the axon (Fig.3A,B). After the subsequent recovery of [Ca2+]i, the neuron was fixed and processed for EM (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

(Right) Correlation between the [Ca2+]i gradient induced by axotomy and the ultrastructural alterations along the axon. The spatiotemporal alterations in [Ca2+]i caused by axotomy were recorded by mag–fura-2 ratio imaging. The neuron subsequently was fixed and processed for EM. A, The peak Ca2+concentrations recorded along the axon (7 sec after axotomy).B, Mag–fura-2 ratio images of the transected axon before axotomy (Control), 7 sec after axotomy, and after the recovery of [Ca2+]i(02:30′). C, A bright-field image of the axon after fixation for EM analysis. Note the detached membrane at the tip of the axon. The ultrastructural data for this experiment are shown in Figure 4.

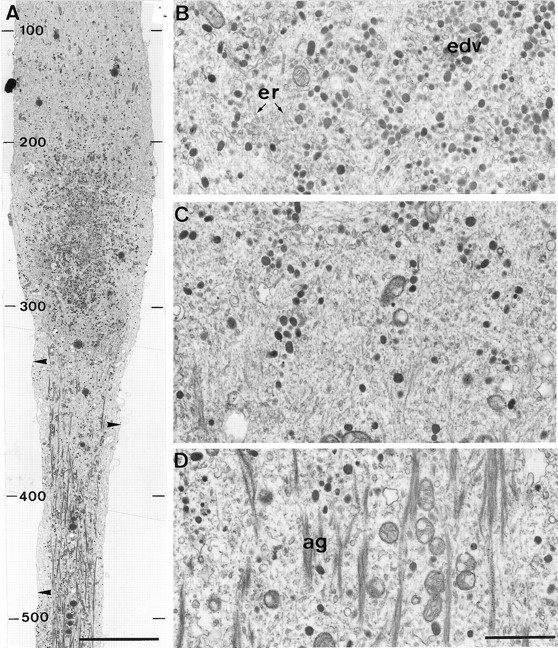

In control neurons, microtubules and neurofilaments are oriented in parallel to the longitudinal axis of the axon, and dense core vesicles and mitochondria are distributed throughout the axoplasm. After axotomy, microtubules are no longer detected at the tip of the transected axon in regions that correspond to [Ca2+]i elevations in excess of 1.5 mm (Fig. 4A,D). In addition, this region is characterized by the presence of large electron-dense deposits. Some vacuoles of unidentified origin are seen.

Fig. 4.

The elevation of [Ca2+]ito >300 μm is associated with significant alterations in the axonal cytoarchitecture. A longitudinal section through the distal region of the transected axon shown in Figure 3 reveals large changes in the axonal ultrastructure along a segment of ∼80 μm from the tip of the transected axon, in which [Ca2+]i was elevated to >300 μm. A, A low-magnification view of the transected axon. Note the disruption of microtubules and neurofilaments in the distal region of the axon, the formation of short fragments of electron-dense filamentous material in the core of the axoplasm, and the conspicuous separation of the axolemma from the axoplasmic core (arrowheads). In particular, note the sharp transition (asterisk) between the severely altered axoplasm and the unaltered axoplasm of the proximal region in which [Ca2+]i was elevated to <300 μm. The peak Ca2+ concentrations (in μm) recorded along the axon after axotomy are indicated on the left side of the figure. B, A high-magnification view of the region adjacent to the axolemma reveals a large gap between the axolemma and the cytoskeletal core (asterisk), which is filled with amorphous axoplasm and several large vacuoles. C, A high-magnification view of the severely altered axoplasmic core reveals that the electron-dense filaments are aggregates of amorphous material and short segments of microtubules (ag). D, A high-magnification view of the tip of the cut axon reveals that large electron-dense aggregates are formed near the tip as well as vacuoles of unidentified origin. mt, Microtubules;m, mitochondria. Scale bars: A, 10 μm;B–D, 0.5 μm.

A feature characteristic to the distal region of the transected axon along a segment of ∼100 μm is the detachment of the axolemma from the axoplasmic core (Figs. 4A,B,5A). This detachment is not a fixation artifact, because the detachment process is detected readily in real time, before fixation, at the light microscope level (data not shown). The space between the core of the axoplasm and the axolemma is filled with amorphous material, vesicles, and swollen subsurface cisterns.

Fig. 5.

The ultrastructure at the transition zone.A, Axolemma reattachment. A high-magnification view of the axolemma at the transition zone (asterisk) reveals that the axolemma, detached from the axoplasmic core along the distal region of the transected axon (left side), reattaches to the axoplasmic core in this region. B, The abrupt ultrastructural transition takes place over ∼5 μm. As seen in Figures 3 and 4, [Ca2+]i was elevated in this region after axotomy to ∼300 μm. Note the disappearance of the electron-dense aggregates (ag) and the recovery of the linear organization of the axoplasm in the proximal region (right side). mt, Microtubules;m, mitochondria; er, endoplasmic reticulum. Scale bar, 1 μm.

With increased distance from the transected tip (Fig.4A,C), clusters of relatively short fragments of microtubules are seen. These fragments are no longer oriented exclusively in parallel to the longitudinal axis of the axon. Many elongated electron-dense aggregates also are observed within this region (Fig. 4C) that appear, at high magnification, to be clusters of microtubule fragments “decorated” with electron-dense particles. No intact neurofilaments are observed along this segment.

The axotomy-induced alterations to the cytoarchitecture of the axon end abruptly 50–150 μm from the cut end, resulting in a sharp transition zone between the axonal segment in which the cytoarchitecture is altered and the rest of the axon in which the cytoarchitecture appears normal (Figs. 4A, 5). Examination of the spatiotemporal [Ca2+]i distribution pattern does not reveal any sharp drop in the [Ca2+]igradient that parallels the sharp transition in the axonal cytoarchitecture. In fact, the [Ca2+]igradually decreases through the transition region from ∼300 μm to the micromolar range (Fig. 3). The transition zone is characterized by the disappearance of the microtubular aggregates and the reappearance of intact neurofilaments and microtubules. It is of particular interest to note that at this transition zone the detached axolemma consistently reattaches to the axoplasmic core (Fig.5A). This region corresponds to the site from which a lamellipodium usually extends after axotomy, as judged by the peak [Ca2+]i recorded in these regions, as well as the typical shape of the axon at this region (Fig. 3C).

Growth cone formation and neuritogenesis can be induced by localized elevations of [Ca2+]i to 300–500 μm

The experiments presented so far established a spatial correlation among the distribution pattern of [Ca2+]iafter axotomy, the resulting morphological and ultrastructural modifications, and the site at which a growth cone is formed. These findings thus suggest a causal relationship between an elevation in [Ca2+]i and the transformation of an axonal segment into a new growth cone. In this section we describe experiments designed to test in a more direct manner whether and at what concentrations a transient, localized elevation of [Ca2+]i can trigger the formation of a growth cone.

To examine the effects of transient and localized elevations in [Ca2+]i on axonal morphology, we used focal applications of the calcium ionophore ionomycin to elevate [Ca2+]i locally in intact axonal segments of cultured Aplysia neurons. The neurons were loaded with a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator (fura-2 or mag–fura-2) to a final concentration of 25–50 μm. A micropipette containing 0.5 mm ionomycin in ASW was then positioned perpendicular to the axon, and the ionomycin solution was ejected onto the axon by applying brief (2–4 sec) pressure pulses to the micropipette. Changes in the spatiotemporal distribution pattern of [Ca2+]i were recorded in real time by fura-2 or mag–fura-2 ratiometric fluorescence microscopy, and the resulting alterations in the axons morphology were followed by DIC video microscopy.

We first examined whether a transient elevation of [Ca2+]i to the low micromolar range is capable of inducing the formation of a new growth cone. This is shown in the representative experiment depicted in Figure 6. Fura-2 imaging revealed that a brief application of ionomycin led to an elevation of [Ca2+]i to ∼2 μm(Fig. 6B). The intracellular Ca2+concentration recovered to control levels within 2 min without causing noticeable changes to the morphology of the axon (Fig.6B, right panels). A second, prolonged ionomycin application to the same site elevated the [Ca2+]i to higher levels (Fig.6C), which exceeded the upper limit of [Ca2+]i that can be resolved by using fura-2 in Aplysia neurons (Ziv and Spira, 1995). In contrast to the first ionophore application, the second application had a profound effect on the morphology of the axon (Fig. 6C, right panels). At 10 min from the second application, the central segment of the axon had flattened out. By 30 min, growth cones, in the form of extending lamellipodia, had formed.

Fig. 6.

Transient elevations in [Ca2+]i induce the formation of ectopic growth cones along intact axons. Focal applications of the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin were used to elevate transiently the [Ca2+]i in intact axons, and the effects of these Ca2+ transients on axonal morphology were recorded. A, The site of ionomycin application (arrow). B, Fura-2 ratio images (left panels) showing the spatiotemporal alterations in the axonal [Ca2+]i induced by a brief ionophore application. [Ca2+]i was elevated transiently to several micromolars. The right panelsshow the axon before (top panel) and 10 min after the application (bottom panel). No significant alterations were caused to the morphology of the axon.C, A second, prolonged ionophore application to the same site elevated [Ca2+]i to levels that exceeded those that could be determined reliably with fura-2 (left panels). The right panels show the axon 10 and 30 min after the second application. Note the general change in the appearance of the axon 10 min after the ionophore application and the subsequent formation of two prominent, overlapping growth cones on both sides of the application site. [Ca2+]i is given in μm. Time is give in minutes from ionomycin application.

To determine the intracellular Ca2+ concentrations sufficient to induce growth cone formation, we performed similar experiments in which the low-affinity Ca2+ indicator mag–fura-2 was used to record the changes in [Ca2+]i. In a representative experiment shown in Figure 7, the ionophore application elevated [Ca2+]i to a maximal level of ∼600 μm at the application point and to decreasing values at increasing distances from the site of application (Fig. 7A). This resulted in the formation of a growth cone structure along a segment in which [Ca2+]i was elevated maximally to 400–600 μm, and this growth cone subsequently developed into an elaborate neuritic tree (Fig.7B).

Fig. 7.

(Top) Axonal dedifferentiation requires transient elevations of [Ca2+]i to 300–600 μm. Mag–fura-2 ratiometric fluorescence microscopy was used to determine the intra-axonal [Ca2+]irequired for inducing the transformation of an intact axonal segment into a growth cone. A, The spatiotemporal alterations in the axonal [Ca2+]i induced by a focal application of ionomycin. The region shown corresponds to therectangle in B, top panel. [Ca2+]i is given in μm.B, The resulting changes in axonal morphology. The transient increase of [Ca2+]i to ∼500 μm induced the formation of a growth cone at the application site, which subsequently developed into a new neuritic tree.

In all of these experiments (n > 8) growth cone formation occurred only along regions where [Ca2+]i was elevated to 300 μmor more. Experiments in which [Ca2+]i was elevated to lower levels failed to induce the formation of ectopic growth cones. On the other hand, ionomycin applications that elevated [Ca2+]i to 1 mm or more usually resulted in the rapid degeneration (“beading”) of the axonal segments (n > 5; data not shown).

It is worth noting that the formation of the growth cone and the subsequent neuritogenesis occurred only after the [Ca2+]i recovered (5–10 min from the ionophore application), suggesting that the transient elevation in [Ca2+]i triggers the growth process but is not required for its perpetuation. In addition, these transient [Ca2+]i elevations and the ectopic growth they induced did not seem to have deleterious effects on the original neuritic trees at the distal end of the original axons (see, for example, Fig. 7B), suggesting that these [Ca2+]i transients did not lead to the degeneration of the axonal segments distal to the ionophore application point.

The ultrastructural alterations caused by localized elevations of [Ca2+]i are identical to those caused by axotomy

The ability of a transient elevation in Ca2+ to mimic the effects of axotomy was examined also at the ultrastructural level. To that end, we loaded buccal neurons with mag–fura-2 and recorded the spatial and temporal alterations in the intracellular Ca2+concentration induced by focal applications of ionomycin, as described above. After the [Ca2+]i recovered to control levels, the neurons were fixed and processed for EM.

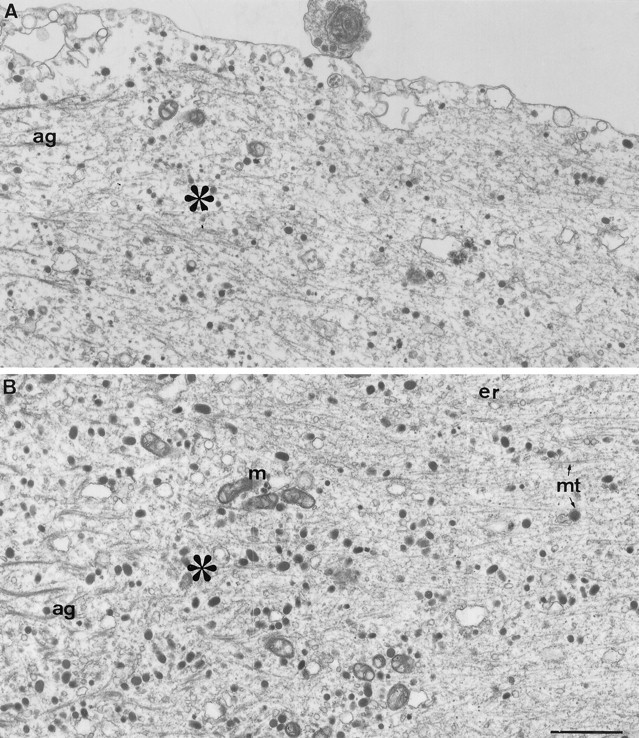

One such experiment (n = 4) is shown in Figures8 and 9. The focal ionomycin application elevated [Ca2+]i to a peak concentration of ∼500 μm (Fig. 8A,B). The corresponding ionomycin-induced alterations to the axonal cytoarchitecture are shown in Figure 9. The ultrastructural alterations caused by the ionophore application and their relations with the peak [Ca2+]i recorded after the application were practically identical to those observed in transected axons (compare with Figs. 4 and 5). Specifically, in regions where [Ca2+]i was elevated to more than ∼300 μm, microtubules were disrupted, and some of them collapsed to form small longitudinal clusters. Neurofilaments were lost, and the axolemma was detached from the axoplasmic core (Fig.9).

Fig. 8.

(Bottom) Correlation between the [Ca2+]i gradient induced by ionophore application and the ultrastructural alterations along the axon. The spatiotemporal alterations in [Ca2+]i caused by a local application of ionomycin were recorded by mag–fura-2 ratio imaging, and the neuron subsequently was fixed and processed for electron microscopy. A, The peak Ca2+concentrations recorded along the axon (17 sec after ionomycin application). B, Mag–fura-2 ratio images of the ionophore-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i.C, A bright-field image of the axon after fixation. The soma of this neuron is located to the left of the visible axonal segment (not shown). [Ca2+]iis given in μm. Time is given in minutes from ionomycin application.

Fig. 9.

Local elevation of [Ca2+]i to >300 μm induces ultrastructural alterations similar to those induced by axotomy. A longitudinal section through the axon shown in Figure 8 reveals that the ionophore-induced Ca2+ elevation caused ultrastructural alterations similar to those observed after axotomy (compare with Fig.4). A, A low-magnification view of the proximal region of the application site. In the central region (bottom), where [Ca2+]i was elevated to ∼300 μm or more, major alterations in axonal cytoarchitecture were observed, which included microtubule and neurofilament disruption and the detachment of the axolemma from the axoplasmic core (arrowheads). In the proximal region (top), the axoplasm retained its normal appearance. Many clear and electron-dense vesicles are seen in the transition zone between these two compartments. The peak Ca2+concentrations (in μm) recorded along the axon after the ionophore application are indicated at the left of the figure. B, A high-magnification view of the region immediately proximal to the transition zone shows that it contains a large number of electron-dense vesicles (edv).C, The transition zone. D, A high-magnification view of the short fragments of electron-dense filamentous aggregates (ag) seen in the core of the axoplasm in which [Ca2+]i was elevated to ∼300 μm or more. er, Endoplasmic reticulum. Scale bars: A, 10 μm; D, 1 μm.

In regions in which [Ca2+]i was not elevated above ∼300 μm, the normal appearance of the axoplasm was retained (Fig. 9A). In common with the ultrastructure of transected axons, well defined transition zones were observed on both sides of the application site (Fig. 9A,C). These transition zones were characterized by the disappearance of the electron-dense aggregates, the reappearance of intact microtubules, and the reattachment of the axolemma to the axoplasmic core (Fig.9A). In the particular experiment of Figures 8 and 9, many vesicles were observed to accumulate in the immediate vicinity of the proximal transition zone (Fig. 9A,B). This region corresponds to the site from which the extension of a lamellipodium usually occurs after the recovery of [Ca2+]i, as judged by the typical shape of the axon at this region.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we examined the hypothesis suggesting that a transient increase in [Ca2+]i, such as that caused by mechanical injury, may provide a signal sufficient to induce the transformation of a differentiated axonal segment into a growth cone. We found that in cultured Aplysia neurons either axotomy or a transient elevation in [Ca2+]iis followed by the extension of a new growth cone from a region along the axon in which [Ca2+]i has been elevated transiently to 300–500 μm. EM analysis revealed that this region is characterized by a sharp transition zone between severely altered axoplasm and axoplasm in which the ultrastructure is unaltered. These findings strongly suggest that a transient elevation of [Ca2+]i to several hundred micromolars may be sufficient to induce the dedifferentiation of an axonal segment into a growth cone. Finally, our experiments show that growth cone formation after axotomy does not occur if the large elevations in [Ca2+]i associated with axotomy are prevented, suggesting that elevations in [Ca2+]i are both necessary and sufficient for the formation of a growth cone after mechanical injury.

The intracellular Ca2+ concentrations recorded after axotomy at the site of growth cone formation (300–500 μm) are well below the peak [Ca2+]i levels recorded closer to the cut end, where [Ca2+]i is elevated to >1 mm (Ziv and Spira, 1995). The peak Ca2+concentrations reached at the sites of growth cone formation seem to be optimal for triggering neuronal outgrowth. We interpret these observations to suggest that key elements in the cellular cascades that lead to growth cone formation are activated by a transient increase in [Ca2+]i to 300–500 μm. Lower Ca2+ concentrations do not activate these cascades (see Fig. 6), whereas higher Ca2+ concentrations may result in severe pathological effects, such as those observed near the cut end of transected axons (see Fig. 4) or those caused by excessive applications of ionomycin.

Our ultrastructural analysis of axotomized and ionomycin-treated axons suggests that these treatments result in the formation of two distinctive axonal regions: regions with seemingly unaltered axoplasm and regions in which the axonal ultrastructure is altered drastically. The transition between these compartments is abrupt (see Figs. 4, 5,9), but, interestingly, this abrupt transition is not reflected in the spatiotemporal distribution pattern of [Ca2+]i. This suggests that [Ca2+]i must exceed a certain threshold to induce the drastic alterations in the axonal cytoarchitecture. It is intriguing that the transition zone delineates the boundaries of the three most prominent cytoarchitectural alterations, namely microtubule fragmentation, neurofilament degradation, and the detachment of the axolemma from the axoplasmic core. This observation may be interpreted to suggest that the activation of a single key element may underlie these ultrastructural modifications.

Calpains (Ca2+-activated neutral proteinases) are likely candidates to play such a role. These proteolytic enzymes are activated by very high levels of calcium, in the range of tens (calpain I) and hundreds (calpain II) of micromolars (for review, see Saido et al., 1994). Indeed, Xie and Barrett (1991) have provided evidence suggesting that calpains are activated after axotomy in cultured rat septal neurons and that their activation is required for the successful resealing of the ruptured axonal membranes. Furthermore, a recent study has suggested that growth cone formation after axotomy can be blocked by a specific inhibitor of calpain (Gitler and Spira, 1996). Calpains display a high degree of substrate selectivity. Among their known substrates are fodrin (Siman et al., 1984; Johnson et al., 1991), a protein that serves to couple the plasma membrane to the cytoskeleton (Bennett and Gilligan, 1993), and several members of the microtubule-associated protein family (Fischer et al., 1991; Johnson et al., 1991), proteins that strongly affect microtubule stability (Maccioni and Cambiazo, 1995). The degradation of these proteins by activated calpains may explain why large (>300 μm) increases in [Ca2+]i invariably are associated with axolemma detachment and microtubule fragmentation.

Microtubule fragmentation seems to be an important step in growth cone formation, because nascent growth cones usually extended near the ends of intact microtubules (Figs. 4, 9; see also Joshi et al., 1986). Microtubule discontinuity may lead to a local accumulation of membranous vesicles (Bray et al., 1978), thus providing an abundant source of membrane for the rapidly extending growth cone. Such vesicle accumulation was observed in several experiments (Fig. 9). In addition, numerous free microtubule ends could facilitate microtubule recruitment by the nascent growth cone (Lin and Forscher, 1993; Bentley and O’Connor, 1994; Lin et al., 1994; Yu et al., 1994; Tanaka and Sabry, 1995), promoting its stabilization and its subsequent transformation into an array of cylindrical neurites.

Our findings provide the first demonstration that a transient elevation in [Ca2+]i is sufficient to induce growth cone formation and irreversible neuritogenesis. These findings are consistent with previous studies that suggest that transient elevations in [Ca2+]i can trigger neuronal remodeling. For example, elevations of [Ca2+]i to hundreds of nanomolars induced by localized electric fields resulted in the transient extension of filopodia from growth cones (Davenport and Kater, 1992) or from neuritic shafts (Williams et al., 1995). However, these filopodia were transient in nature and failed to develop into persistent structures. The transient nature of these protrusions was attributed to a lack of stabilizing factors in the environment. However, other explanations are possible. For example, the stabilization of such structures may depend on their ability to recruit microtubules, as discussed above. This may require free microtubule ends, which, in turn, may require microtubule fragmentation (Joshi and Baas, 1993; Yu et al., 1994). It is likely that the elevations of cytosolic [Ca2+]i induced by focal electric fields (<1 μm) were insufficient to induce such microtubule fragmentation. Indeed, in a separate set of experiments, we were unable to detect significant alterations in the axonal ultrastructure or morphology after elevating [Ca2+]i to 3–4 μm for 2–4 min by intra-axonal injections of a CaCl2-containing solution (n > 10; N. E. Ziv, A. Dormann, M. E. Spira, unpublished observations). It is possible, however, that focal electric fields elevate submembranal [Ca2+]i to much higher levels than those recorded in the axoplasm, resulting in a transient remodeling of the cortical cytoskeleton that is manifested as filopodia extension.

A significant body of evidence suggests that morphological remodeling and neuronal regrowth may provide the basis for certain forms of long-term memory (Bailey and Kandel, 1993). It is tempting to speculate that some of the mechanisms invoked by axotomy and ionomycin applications also may be involved in such remodeling processes. Recent studies have provided evidence that neurotransmitter release is associated with transient elevations of [Ca2+]i to hundreds of micromolars at submembrane microdomains of the presynaptic terminal (Adler et al., 1991; Llinás et al., 1992, 1994). However, these elevations are extremely confined both spatially and temporally; thus, their capacity to invoke mechanisms activated by axotomy or ionomycin applications is not clear. It is quite possible, however, that such mechanisms may be involved in postsynaptic remodeling of dendrites and dendritic spines, in which [Ca2+]i may be elevated to >40 μm for several seconds in response to tetanic stimulation (Petrozzino et al., 1995) (see also Fifkova et al., 1983; Koch and Pogio, 1983; Lynch and Baudry, 1984; Lynch and Seubert, 1989; Lynch et al., 1990).

During development, axon and dendrite formation, as well as collateral branch extension, is preceded by the formation of growth cones (Harris et al., 1987; Dotti et al., 1988; O’leary and Terashima, 1988; Lefcort and Bentley, 1989). We are not aware of experimental data that show that growth cone emergence during neuronal development is preceded by a large increase in [Ca2+]i. It is clear, however, that the formation of these growth cones is preceded by cytoarchitectural rearrangements that underlie the extension of filopodia and lamellipodia, the hallmarks of the motile growth cone. Although the mechanisms that orchestrate these rearrangements are currently unknown, our findings may provide new opportunities for elucidating some of the mechanisms that underlie the initiation of neuronal outgrowth.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the United States–Israel Bi-National Research Foundation (93–00132/1) and from the Clore Foundation. M.E.S. is the Levi Deviali Professor in Neurobiology. We thank A. Dormann for her technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Micha E. Spira, Department of Neurobiology, Life Sciences Institute, Givat Ram Campus, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 91904, Israel.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler EM, Augustine GJ, Duffy SN, Charlton MP. Alien intracellular calcium chelators attenuate neurotransmitter release at the squid giant synapse. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1496–1507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01496.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashery U, Penner R, Spira ME. Acceleration of membrane recycling by axotomy of cultured Aplysia neurons. Neuron. 1996;16:641–651. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baas PW, Heidemann SR. Microtubule reassembly from nucleating fragments during the regrowth of amputated neurites. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:917–927. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.3.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baas PW, White LA, Heidemann SR. Microtubule polarity reversal accompanies regrowth of amputated neurites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5272–5276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey CH, Kandel ER. Structural changes accompanying memory storage. Annu Rev Physiol. 1993;55:397–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.55.030193.002145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballinger ML, Bittner GD. Ultrastructural studies of severed medial giant and other CNS axons in crayfish. Cell Tissue Res. 1980;208:123–133. doi: 10.1007/BF00234178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benbassat D, Spira ME. Survival of isolated axonal segments in culture: morphological, ultrastructural, and physiological analysis. Exp Neurol. 1993;122:295–310. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benbassat D, Spira ME. The survival of transected axonal segments of cultured Aplysia neurons is prolonged by contact with intact nerve cells. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:1605–1614. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett V, Gilligan DM. The spectrin-based membrane skeleton and micron-scale organization of the plasma membrane. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:27–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bentley D, O’Connor TP. Cytoskeletal events in growth cone steering. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borgens RB, Jaffe LF, Cohen MJ. Large and persistent electrical currents enter the transected lamprey spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:1209–1213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.2.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bray D, Thomas C, Shaw G. Growth cone formation in cultures of sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:5226–5229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davenport RW, Kater SB. Local increases in intracellular calcium elicit local filopodial responses in Helisoma neuronal growth cones. Neuron. 1992;9:405–416. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90179-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dotti CG, Sullivan CA, Banker GA. The establishment of polarity in hippocampal neurons in culture. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1454–1468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-04-01454.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emery DG, Lucas JH, Gross GW. The sequence of ultrastructure changes in cultured neurons after dendrite transection. Exp Brain Res. 1987;67:41–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00269451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fifkova E, Markham JA, Delay RJ. Calcium in the spine apparatus of dendritic spines in the dentate molecular layer. Brain Res. 1983;266:163–168. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer I, Romano-Clark G, Grynspan F. Calpain-mediated proteolysis of microtubule-associated proteins MAP1B and MAP2 in developing brain. Neurochem Res. 1991;16:891–898. doi: 10.1007/BF00965538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forscher P, Kaczmarek LK, Buchanan J, Smith SJ. Cyclic AMP induces changes in distribution and transport of organelles within growth cones of Aplysia bag cell neurons. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3600–3611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-11-03600.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallant PE. Effects of the external ions and metabolic poisoning on the constriction of the squid giant axon after axotomy. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1479–1484. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-05-01479.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gitler D, Spira ME. Calpain activation is a crucial step in the initiation of growth cone formation in cultured Aplysia neurons. J Neurochem. 1996;66:S24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross GW, Higgins ML. Cytoplasmic damage gradients in dendrites after transection lesions. Exp Brain Res. 1987;67:52–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00269452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross GW, Lucas JH, Higgens ML. Laser microbeam surgery: ultrastructural changes associated with neurite transection in culture. J Neurosci. 1983;3:1979–1993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-10-01979.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Happel RD, Smith KP, Banik NL, Powers JM, Hogan EL, Balentine JD. Ca2+ accumulation in experimental spinal cord trauma. Brain Res. 1981;2:476–479. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90976-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris WA, Holt CE, Bonhoeffer F. Retinal axons with and without their somata, growing to and arborizing in the tectum of Xenopus embryos: a time-lapse video study of single fibers in vivo. Development (Camb) 1987;101:123–133. doi: 10.1242/dev.101.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson GVW, Litersky JM, Jope RS. Degradation of microtubule-associated protein 2 and brain spectrin by calpain: a comparative study. J Neurochem. 1991;56:1630–1638. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joshi HC, Baas PW. A new perspective on microtubules and axon growth. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:1191–1196. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.6.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshi HC, Baas P, Chu DT, Heidemann SR. The cytoskeleton of neurites after microtubule depolymerization. Exp Cell Res. 1986;163:233–245. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(86)90576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koch C, Poggio T. A theoretical analysis of electrical properties of spines. Proc R Soc Lond [Biol] 1983;218:455–477. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1983.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krause TL, Fishman HM, Ballinger ML, Bittner GD. Extent and mechanism of sealing in transected giant axons of squid and earthworms. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6638–6651. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06638.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lefcort F, Bentley D. Organization of cytoskeletal elements and organelles preceding growth cone emergence from an identified neuron in situ. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1737–1749. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.5.1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Letourneau PC, Kater SB, Macagno ER. The nerve growth cone. Raven; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin CH, Forscher P. Cytoskeletal remodeling during growth cone-target interactions. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:1369–1383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.6.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin CH, Thompson CA, Forscher P. Cytoskeletal reorganization underlying growth cone motility. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4:640–647. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Llinás R, Sugimori M, Silver RB. Microdomains of high calcium concentration in a presynaptic terminal. Science. 1992;256:677–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1350109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Llinás R, Sugimori M, Silver RB. Localization of calcium concentration microdomains at the active zone in the squid giant synapse. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1994;29:133–137. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(06)80012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lucas JH, Gross GW, Emery DG, Gardner CR. Neuronal survival or death after dendrite transection close to the perikaryon: correlation with electrophysiologic, morphologic, and ultrastructural changes. Contemp Neurol Ser Trauma. 1985;2:231–255. doi: 10.1089/cns.1985.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lynch G, Baudry M. The biochemistry of memory: a new and specific hypothesis. Science. 1984;224:1058–1063. doi: 10.1126/science.6144182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynch G, Seubert P. Links between long-term potentiation and neuropathology. An hypothesis involving calcium-activated proteases. In: Khachaturian ZS, Cotman CW, Pettegrew JW, editors. Calcium, membranes, aging, and Alzheimer’s disease. New York Academy of Sciences; New York: 1989. pp. 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynch G, Kessler M, Arai A, Larson J. The nature and causes of hippocampal long-term potentiation. In: Storm-Mathisen J, Zimmer J, Ottersen OP, editors. Progress in brain research. Elsevier; New York: 1990. pp. 233–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maccioni RB, Cambiazo V. Role of microtubule-associated proteins in the control of microtubule assembly. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:835–864. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.4.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mata M, Staple J, Fink DJ. Changes in intra-axonal calcium distribution following nerve crush. J Neurobiol. 1986;17:449–467. doi: 10.1002/neu.480170508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meiri H, Dormann A, Spira ME. Comparison of ultrastructural changes in proximal and distal segments of transected giant fibers of the cockroach Periplaneta americana. Brain Res. 1983;263:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’leary DDM, Terashima T. Cortical axons branch to multiple subcortical targets by interstitial axon budding: implications for target recognition and “waiting periods.”. Neuron. 1988;1:901–910. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petrozzino JJ, Pozzo Miller LD, Connor JA. Micromolar Ca2+ transients in dendritic spines of hippocampal pyramidal neurons in brain slice. Neuron. 1995;14:1223–1231. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raju B, Murphy E, Levy LA, Hall RD, London RE. A fluorescent indicator for measuring cytosolic free magnesium. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:C540–C548. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.3.C540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rehder V, Jensen JR, Dou P, Kater SB. A comparison of calcium homeostasis in isolated and attached growth cones of the snail Helisoma. J Neurobiol. 1991;22:499–511. doi: 10.1002/neu.480220506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rehder V, Jensen JR, Kater SB. The initial stages of neural regeneration are dependent upon intracellular Ca2+ levels. Neuroscience. 1992;51:565–574. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90296-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roederer E, Goldberg NH, Cohen MJ. Modification of retrograde degeneration in transected spinal axons of the lamprey by applied DC current. J Neurosci. 1983;3:153–160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-01-00153.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saido TC, Sorimachi H, Suzuki K. Calpain: new perspectives in molecular diversity and physiological–pathological involvement. FASEB J. 1994;8:814–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schacher S, Proshansky E. Neurite regeneration by Aplysia neurons in dissociated cell culture: modulation by Aplysia hemolymph and the presence of the initial axonal segment. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2403–2413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-12-02403.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schlaepfer WW. Calcium-induced degeneration of axoplasm in isolated segments of rat peripheral nerve. Brain Res. 1974;69:203–216. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaw G, Bray D. Movement and extension of isolated growth cones. Exp Cell Res. 1977;104:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(77)90068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siman R, Baudry M, Lynch G. Brain fodrin: substrate for calpain I and endogenous calcium-activated protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3572–3576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spira ME, Benbassat D, Dormann A. Resealing of the proximal and distal cut ends of transected axons: electrophysiological and ultrastructural analysis. J Neurobiol. 1993;24:300–316. doi: 10.1002/neu.480240304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spira ME, Dormann A, Ashery U, Gabso M, Gitler D, Benbassat D, Oren R, Ziv NE. Use of Aplysia neurons for the study of cellular alterations and the resealing of transected axons in vitro. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;69:91–102. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(96)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strautman AF, Cork RJ, Robinson KR. The distribution of free calcium in transected spinal axons and its modulation by applied electrical fields. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3564–3575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03564.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanaka E, Sabry J. Making the connection: cytoskeletal rearrangements during growth cone guidance. Cell. 1995;83:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wessells NK, Johnson SR, Nuttall RP. Axon initiation and growth cone regeneration in cultured motor neurons. Exp Cell Res. 1978;117:335–345. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(78)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams CV, Davenport RW, Dou P, Kater S. Developmental regulation of plasticity along neurite shaft. J Neurobiol. 1995;27:127–140. doi: 10.1002/neu.480270202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xie X, Barrett JN. Membrane resealing in cultured rat septal neurons after neurite transection: evidence for enhancement by Ca2+-triggered protease activity and cytoskeletal disassembly. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3257–3267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03257.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yawo H, Kuno M. Calcium dependence of membrane sealing at the cut end of the cockroach giant axon. J Neurosci. 1985;5:1626–1632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-06-01626.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu W, Ahmad FJ, Baas PW. Microtubule fragmentation and partitioning in the axon during collateral branch formation. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5872–5884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-05872.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zelena J, Lubinska L, Gutmann E. Accumulation of organelles at the end of interrupted axons. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1968;91:200–219. doi: 10.1007/BF00364311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ziv NE, Spira ME. Spatiotemporal distribution of Ca2+ following axotomy and throughout the recovery process of cultured Aplysia neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:657–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ziv NE, Spira ME. Axotomy induces a transient and localized elevation of the free intracellular calcium concentration to the millimolar range. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:2625–2637. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.6.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]