Abstract

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from CA1 pyramidal and dentate gyrus granule cells (GCs) in hippocampal slices to assess the effects of withdrawal from chronic flurazepam (FRZ) treatment on the function of synaptic GABAA receptors. In slices from control rats, acute perfusion of FRZ (30 μm) increased the monoexponential decay time constant of miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) in CA1 and GCs (from 3.4 ± 0.6 to 7.6 ± 2.1 msec and from 4.2 ± 0.6 to 7.1 ± 1.8 msec, respectively) but did not change their mean conductance, 10–90% rise time, or frequency of occurrence. Withdrawal (2–5 d) from chronic in vivo FRZ treatment (40–110 mg/kg per day, per os) resulted in a dramatic loss of mIPSCs in CA1 neurons. On day 5 of withdrawal, no mIPSCs could be recorded in 40% of CA1 pyramidal cells. In the remaining 60% of the neurons, mIPSCs had a reduced mean conductance (from 0.78 ± 0.12 nS in vehicle-treated controls to 0.31 ± 0.05 nS) and a diminished frequency of occurrence (from 20.7 ± 7.9 to 4.1 ± 0.6 Hz). We have estimated that >80% of GABAA synapses on CA1 pyramidal cells had become silent, whereas at still-active synapses the number of functional GABAA receptor channels decreased by 60%. This reduction rapidly reverted to control levels on day 6 of withdrawal. FRZ withdrawal did not alter mIPSC properties in GCs. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that chronic benzodiazepine treatment leads to a reduced number of functional synaptic GABAA receptors in a region-specific manner that may stem from differences in the subunit composition of synaptic GABAA receptors.

Keywords: withdrawal, inhibitory synapses, drug dependence, benzodiazepines, GABAA, IPSCs, hippocampus

Benzodiazepines (BZ) commonly are used as anxiolytic, antiepileptic, sedative hypnotic, and muscle relaxant agents. However, their usefulness in chronic therapy is limited by a combination of tolerance, side effects, abuse potential, and interaction with ethanol (File, 1993). Furthermore, withdrawal symptoms develop after prolonged exposure to BZs, and these symptoms may occur even after low to moderate doses (Gallager and Primus, 1993; Klein and Harris, 1996).

During prolonged BZ treatment tolerance develops and is associated with the progressive loss of drug effectiveness. It implies an increase of the dose required to obtain therapeutic effects. Cessation of drug treatment produces a behavioral syndrome called withdrawal, which is characterized by agitation, anxiety, tremor, insomnia, or convulsions (Schoch et al., 1993); these symptoms can be relieved by readministering the drug, and therefore they define a state of drug dependence. Animal studies have revealed that withdrawal symptoms after the termination of chronic BZ treatment may be blocked by the application of BZ receptor antagonists (Gonsalves and Gallager, 1985,1988).

The loss of anticonvulsant activity after chronic BZ treatment is thought to be associated with an uncoupling of BZ and GABA binding at the level of GABAA receptors (Gallager et al., 1984; Marley and Gallager, 1989). In some studies no or little change has been seen in the expression levels of GABAA receptor subunits and GABA/BZ binding (Gallager and Primus, 1993; Klein and Harris, 1996). Other studies indicate that chronic BZ exposure leads to a decrease in the number of BZ binding sites (Zhao et al., 1994b) and certain subunit GABAA receptor mRNAs (Heninger et al., 1990; Kang and Miller, 1991; O’Donovan et al., 1992; Primus and Gallager, 1992; Tietz et al., 1993; Wu et al., 1994; Zhao et al., 1994a,b; Holt et al., 1995). Intracellular second messengers also may be involved, because reduction of the α1 subunit expression induced by chronic flunitrazepam exposure is reversed completely by micromolar concentrations of the protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine (Brown and Bristow, 1996).

To date, few studies have focused on GABAAreceptor-mediated synaptic transmission during and after chronic BZ administration. Recently, a specific decrease of GABAAsubunit mRNAs and immunoreactivity in the hippocampal CA1 region has been correlated with a persistent decrease of the amplitude of evoked and spontaneous GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic potentials and currents (Zeng and Tietz, 1995; Zeng et al., 1995). To resolve further the possible long-term alterations of synaptic GABAA receptor function caused by BZ withdrawal in the adult rat hippocampus, we have compared miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) of CA1 pyramidal and dentate gyrus granule cells (GCs) in slices from controls and animals after the withdrawal of chronic flurazepam (FRZ) treatment. As opposed to the study of stimulus-evoked or action potential-dependent spontaneous IPSCs, analysis of mIPSCs allowed us to resolve synaptic transmission at the level of each individual “bouton” and to exclude possible presynaptic mechanisms related to action potentials or calcium entry (Mody et al., 1994). We demonstrate BZ withdrawal to result in temporary “silent” inhibitory synapses in CA1 neurons, but not in GCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chronic FRZ treatment. Rats were allowed to drink FRZ dissolved in distilled water containing 0.02% saccharine ad libitum. Treatment consisted of 4 d with a low concentration of FRZ (2 mm), followed by 3 d of a higher concentration (3 mm). The amount of FRZ effectively consumed was 40.0 ± 5.3 mg/kg per day (n = 6) during the first period (low dose) and 113.3 ± 35 mg/kg per day (n = 6) in the second period (high dose). Slices were prepared after 2–6 d of withdrawal. Vehicle-treated rats freely drank water containing only 0.02% saccharine, or, to avoid any bias because of differences in water consumption, another group of controls was allowed to drink the same amount of saccharine water as their FRZ-treated counterparts. No differences were found between the two vehicle-treated groups; therefore, data from these groups were pooled as “controls.”

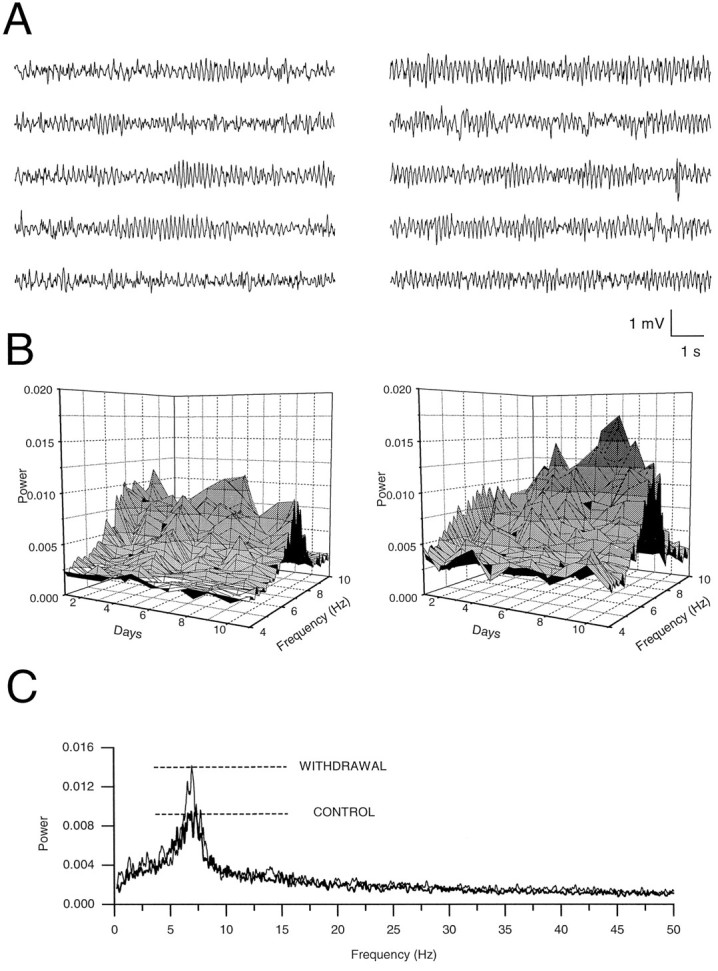

Electrographic assessment of BZ administration and withdrawal.To assess changes of electrical activity in the hippocampal CA1 region during and after the BZ treatment, we implanted stainless steel bipolar electrodes in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer of male Wistar rats under Na-pentobarbital anesthesia (65 mg/kg, i.p.) The coordinates for electrode positions were 3.4 mm posterior to bregma, 1.7 lateral to midline, and 2.1 mm below the surface of the cortex. After at least 1 week of postsurgical recovery, the electrical activity was recorded and stored on videotape after being filtered at 30 kHz. Recordings were made every day (before, during, and after cessation of the chronic BZ treatment) at the same hour and in similar environmental conditions for 4–8 min. Two examples of such electrographic recordings are shown in Figure 1A in control conditions (before the beginning of the treatment, left traces) and after 5 d of withdrawal (right traces). To analyze these recordings further, we filtered traces off-line at 200 Hz and digitized them at 500 Hz with the Strathclyde Electrophysiology software (CDR; by J. Dempster, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK). These parameters were used routinely after it was verified that filtering and digitizing at higher frequencies gave similar results.

Fig. 1.

Depth electrode recordings of hippocampal CA1 electrical activity and its analysis. A, Continuous electrograms of 50 sec each depict extracellular voltage oscillations before drug treatment (left five traces) and on day 5 of FRZ withdrawal (right five traces). B, Daily progression of the spectral amplitude of the CA1 electrogram measured in the range of 4–10 Hz. In this example the animal consumed FRZ (35–65 mg/kg per day) from days 2 through 7, and the withdrawal period started on day 8. Compared with the control values in a vehicle-treated animal (left graph) and before the beginning of the treatment (right graph, Day 1), the peak at 7 Hz was increased during the withdrawal period. During FRZ treatment the spectra were similar to those observed in controls, except on the first day of FRZ treatment (Day 2 on the graph), in which the peak at 7 Hz was strongly reduced. C, A larger frequency range (0–50 Hz) of the electrogram spectra before the start of the FRZ treatment (thick line) and 4 d after withdrawal (thin line) illustrates the largest increase in power at ∼7 Hz (theta frequency range).

Spectral analysis of the recordings was performed with the “built-in” Fast Fourier Transform of Microcal Origin Software (Microcal Software, 1995). Examples of the frequency spectra obtained by this method are shown in Figure 1B (spectra 4–10 Hz) and Figure 1C (spectra 0–50 Hz). As shown by these examples, one major peak was detected at 7 Hz, corresponding to the range of theta oscillations. Compared with a vehicle-treated control animal (Fig. 1B, left graph; 1C, thick line), the power of this peak at 7 Hz was increased during the withdrawal period, reaching a maximum at day 9 (see Fig. 1 legend for details).

Slice preparation and solutions. Coronal slices were prepared from control, vehicle-, and FRZ-treated Wistar rats (350–400 gm) as previously described (Otis et al., 1991; Otis and Mody, 1992;Staley et al., 1992). Briefly, after ketamine xylazine anesthesia (10 mg/kg), animals were decapitated, and the brains were removed quickly and immersed for 1–2 min in cold (4°C) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mm): 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose, and 2 kynurenic acid (Fluka BioChemika, Ronkonkoma, NY) continuously bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.35 ± 0.05. The brain was glued, at its frontal surface, to a brass platform, and coronal brain slices (450 μm thick) were prepared with a Vibratome (Lancer Series 1000). Then the slices were hemisected and stored submerged in kynurenic acid containing ACSF at 32°C until individually transferred to the recording chamber. Recordings were performed at 34–35°C, with slices immobilized with a piece of lens paper and small platinum weights. Before recordings, 1 μm tetrodotoxin (TTX; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) was added to the ACSF in the presence of the glutamate receptor antagonist kynurenic acid (2 mm).

Whole-cell recordings and data collection. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were obtained by using borosilicate glass capillaries with an inner filament [KG-33; 1.12 mm inner diameter, 1.5 mm outer diameter (o.d.); Garner Glass] pulled to 1.5–3 μm (o.d.) in two stages with a vertical puller (Narishige PP-83). Intrapipette solutions contained (in mm): 130 CsCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.2 bis-aminophenoxy-ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetra-acetic acid (BAPTA), 0.8 CsOH, and 2 MgATP (pH was adjusted with CsOH; total osmolality, 255–285 mOsm).

Recordings were obtained by lowering patch electrodes into the CA1 and/or granule cell layer while monitoring current responses to 5 mV voltage pulses and applying suction to form >GΩ seals. Axopatch 200A and 1D amplifiers (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) were used; series resistance was compensated by >70%. Access resistance was monitored throughout each experiment, and only recordings with access resistances of 5–15 MΩ were considered acceptable for analysis. Recorded membrane currents were filtered (DC to 10 kHz), digitized (44 kHz; Neurocorder, Neurodata), and stored on videotape. Off-line, recordings were filtered (DC to 3 kHz; −3 dB, 8-pole Bessel, Frequency Devices 9002) and sampled at 20 kHz on a microcomputer. Data were analyzed with the Strathclyde Electrophysiology software and in-house software designed by Y. De Koninck and I. Mody.

Event detection and selection. Detection of individual mIPSCs was performed by using a software trigger previously described in detail (Otis and Mody, 1992; Soltesz et al., 1995); >95% of events that satisfied the trigger criteria were detected, even during compound mIPSCs. For each experiment all detected events were examined, and any noise that spuriously met trigger specification was rejected.

Statistical analysis and curve fitting. The mean values of the conductances, decay time constants, and frequency of occurrence of mIPSCs were compared among groups with Student’s t test. Decay time constants of mIPSCs were fitted by nonlinear least square methods; goodness of fit was evaluated on the basis of fitting subsets of points drawn from the whole set of data points and from evaluation of the reduced χ2 values. The change in the Fvalues was calculated from the sum of squared differences from the fitted line (Soltesz and Mody, 1995). The conductance, decay time constant, and 10–90% rise time of mIPSCs are represented graphically in cumulative probability plots drawn on a probability scale ordinate. All numerical data are expressed as mean ± SD.

RESULTS

Characteristics and potentiation by FRZ of GABAAreceptor-mediated mIPSCs in control CA1 and GCs.

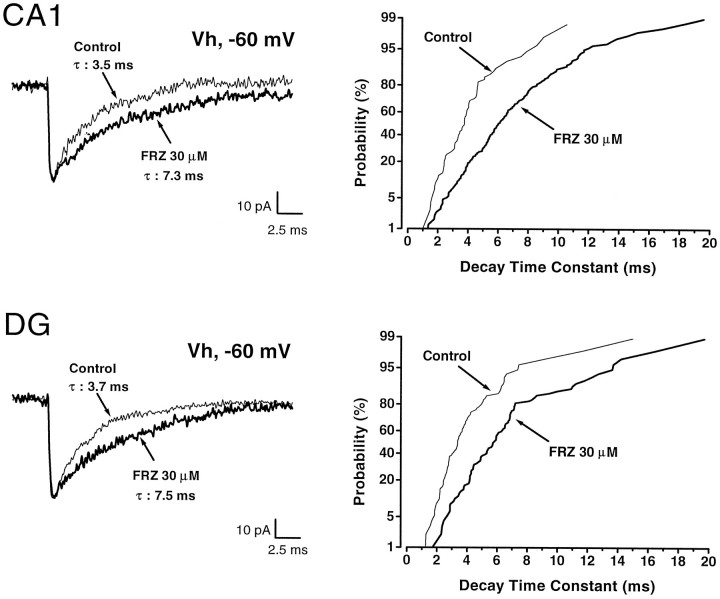

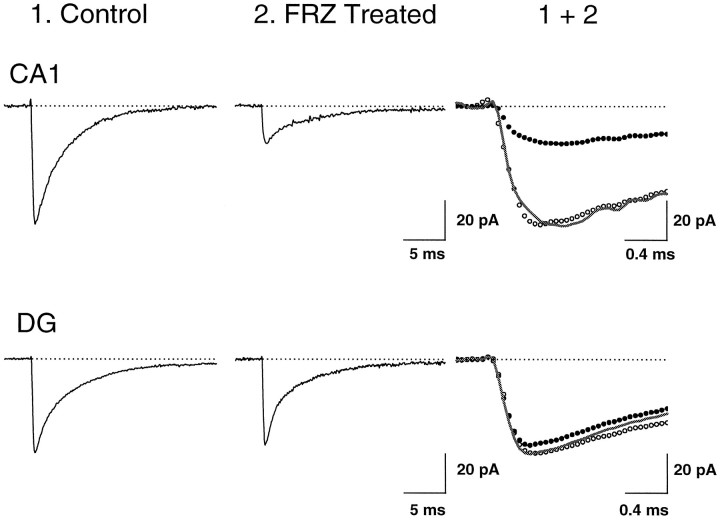

As a preliminary step in the study of the effects of FRZ withdrawal on mIPSCs, we ascertained that acute FRZ application altered the properties of mIPSCs, as has been demonstrated for other BZ agonists (Otis and Mody, 1992; Mody et al., 1994). At a holding potential of −60 mV, GABAA receptor-mediated mIPSCs recorded in both CA1 (n = 18) and GCs (n = 15) were inward as a consequence of Cl− loading and were characterized by the 10–90% rise times, decay time constants, conductances at the peak of mIPSCs, and frequency of occurrence indicated in Table 1. The major difference between mIPSCs recorded from these two cell groups was their frequency of occurrence. Bath application of FRZ (30 μm) prolonged the decay time constant of mIPSCs (from 3.4 ± 0.6 to 7.6 ± 2.1 msec in CA1, n = 12; from 4.2 ± 0.6 to 7.1 ± 1.8 msec in GCs, n = 6) but did not alter their mean 10–90% rise time, conductance, or frequency of occurrence in either CA1 or GCs (Table 1, Fig. 2). Cumulative probability plots (Fig. 2, right panels) of the decay time constants were shifted to the right in a parallel manner, indicating that FRZ elicited a proportional increase of the decay time constants of all detected mIPSCs.

Table 1.

Modulation of GABAA receptor-mediated mIPSCs by acute perfusion of FRZ in CA1 and dentate gyrus (DG) hippocampal neurons

| CA1 | DG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Acute FRZ | Control | FRZ | |

| Conductance (nS) | 0.69 ± 0.15 | 0.73 ± 0.26 | 0.62 ± 0.12 | 0.71 ± 0.11 |

| Decay time constant (msec) | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 7.6 ± 2.1* | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 7.1 ± 1.8* |

| 10–90% Rise time (msec) | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 0.62 ± 0.11 | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 0.63 ± 0.03 |

| Frequency (Hz) | 22.6 ± 7.0 | 18.7 ± 6.6 | 8.2 ± 4.7 | 7.4 ± 3.3 |

| Number of cells | 18 | 12 | 15 | 6 |

In both CA1 and DG, perfusion of FRZ (30 μm) produced prolongation of mIPSCs without affecting the mean conductance, 10–90% rise time, and frequency of occurrence. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Asterisk indicates statistically significant differences (t test) with respect to the control at p< 0.0001. Values without asterisk are not significantly different from control at p > 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Effect of FRZ (30 μm) onCA1 and dentate gyrus (DG) granule cell GABAA receptor-mediated mIPSCs. The left panels represent superimposed averages of 30–35 mIPSCs in control (thin line) and FRZ (thick line) traces. Note that FRZ at concentrations corresponding to “low dose” chronic treatment (30 μm) induced prolongation of the decay time constant from 3.5 to 7.3 msec and from 3.7 to 7.5 msec inCA1 pyramidal cells and DG, respectively. The right panels represent the cumulative probabilities of 92–235 mIPSC decay time constants in the same cells. In both cases, i.e., CA1 and DG, FRZ increased the decay time constants of all mIPSCs. Holding potential was −60 mV.

Withdrawal from FRZ alters mIPSCs in CA1, but not GCs

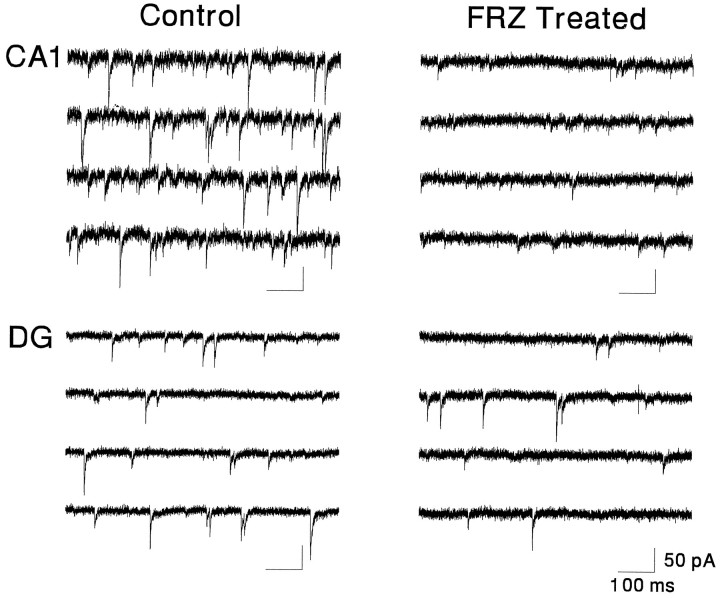

The properties of mIPSCs recorded in CA1 and GCs in slices obtained from rats after withdrawal from FRZ treatment were compared with those in slices from vehicle-treated (control) animals. mIPSCs in CA1 and GCs of vehicle-treated animals had kinetic properties similar to those of untreated animals (compare values in Table 2with those in Table 1). After 2–5 d of withdrawal from FRZ treatment, however, the properties of mIPSCs recorded in CA1, but not in GCs, became altered. Figure 3 illustrates an example of the massive reduction of the amplitude and frequency of mIPSCs in CA1, but not GCs, after FRZ withdrawal. In 40% (n = 20) of the CA1 pyramidal cells recorded after 5 d of FRZ withdrawal, no mIPSCs could be detected at all. This effect was not a consequence of changes in the input resistance of the CA1 neurons nor a failure to detect mIPSC. First, input resistances measured during seal test pulses were similar between control and FRZ-treated cells. Second, if small, undetected events were still present but were buried in the baseline noise, one would expect the baseline current to have different spectral characteristics from “eventless” traces in vehicle-treated controls. Yet stationary noise analysis of current traces devoid of mIPSCs in CA1 neurons from control and FRZ-treated animals yielded similar power spectra with comparable corner frequencies (data not shown).

Table 2.

Comparison of conductances, decay time constants, rise times, and frequencies for CA1 and dentate gyrus (DG) granule cells in control and FRZ-treated rats

| CA1 | DG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | FRZ | Conrol | FRZ | |

| Conductance (nS) | 0.78 ± 0.12 | 0.31 ± 0.05* | 0.67 ± 0.25 | 0.62 ± 0.13 |

| Decay time constant (msec) | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 4.1 ± 0.7 |

| 10–90% Rise time (msec) | 0.65 ± 0.16 | 0.56 ± 0.11 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.52 ± 0.02 |

| Frequency (Hz) | 20.7 ± 7.9 | 4.1 ± 0.6* | 8.4 ± 5.8 | 8.7 ± 7.0 |

| Number of cells | 18 | 31 | 6 | 9 |

In CA1 neurons, withdrawal after 5 d of FRZ treatment induced a 60% decrease in the mean conductance and an 80% reduction in the frequency. Note that this table does not include 40% (n = 20) of CA1 neurons, which were silent after 5 d of withdrawal after chronic FRZ exposure. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Asterisk indicates statistically significant differences (ttest) with respect to controls p < 0.0001. Values without asterisk are not significantly different from control (p > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Specific reduction of mIPSCs in CA1neurons versus dentate gyrus (DG) granule cells in FRZ-treated rats after 5 d of withdrawal. Continuous raw traces (3 sec each) depicting mIPSCs in a control CA1 pyramidal and a DG granule cell are shown in the left panels and can be compared with those obtained in similar cells in FRZ-treated animals on day 5 of withdrawal (right panels). Note the low incidence of small amplitude mIPSCs in the CA1 pyramidal neuron after chronic FRZ. Holding potential was −60 mV in all cases.

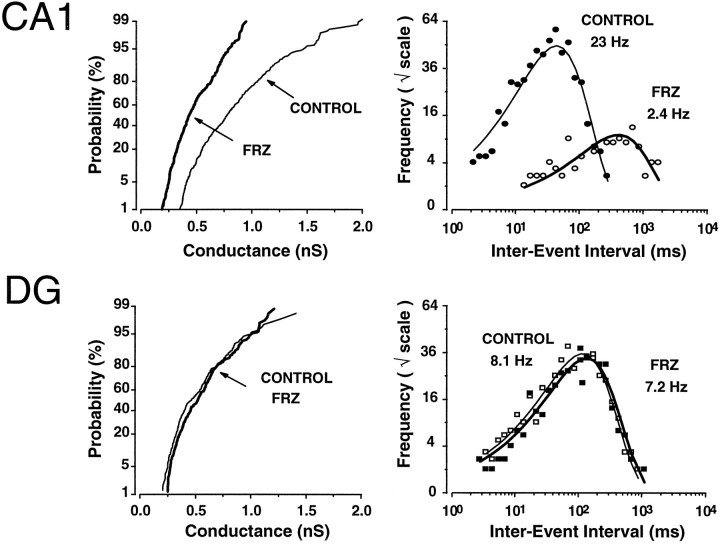

The reduction of mIPSCs in CA1 neurons consisted of a 2.5-fold decrease (−60%) in their mean conductance at peak and a fivefold (−80%) reduction in their frequency of occurrence (Fig. 4). The values for the various mIPSC parameters for groups of neurons recorded in control slices and after 5 d of FRZ withdrawal are presented in Table 2. Note that these data do not include the 40% of CA1 neurons on day 5 of the withdrawal in which mIPSCs were abolished completely. Cumulative probability plots demonstrate that the distribution of the mIPSCs conductance generated in CA1 neurons recorded after FRZ withdrawal were shifted to the left in an approximately parallel manner (Fig. 4, top left panel), regardless of individual mIPSC size. This was not the case for GCs recorded from the same slices and with identical methods as for CA1 neurons, in which FRZ withdrawal failed to alter the conductance or the frequency of occurrence of mIPSCs (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Example of conductance and frequency of mIPSCs inCA1 and dentate gyrus (DG) granule cells recorded in a slice of a control animal and a slice obtained after 5 d of withdrawal. Left panels represent the cumulative probability plots of the conductance of mIPSCs measured at their peak in control (thin lines; n= 477 for CA1 and n = 224 forDG) (n represents number of events) and FRZ-treated rats (thick lines; n = 388 for CA1 and n = 249 forDG). A decrease in conductance after chronic FRZ treatment was observed only in CA1 neurons. On theright panels log-binned (10 bins/decade) inter-event intervals are plotted on a square root ordinate and illustrate the mIPSC frequency in a control (thin lines, filled symbols) and FRZ-treated (thick lines,open symbols) CA1 pyramidal andDG, respectively. The fitted lines are exponential probability density functions illustrating the random nature of mIPSCs. In these representative CA1 cells, the mIPSC frequency was reduced from 23 Hz (n = 547 mIPSCs) to 2.4 Hz (n = 115 mIPSCs). This effect was not observed inDG granule cells after FRZ withdrawal. In the two granule cells illustrated, the mIPSC frequencies were 8.1 Hz (n = 407 events in control) and 7.2 Hz (n = 384 in FRZ-treated).

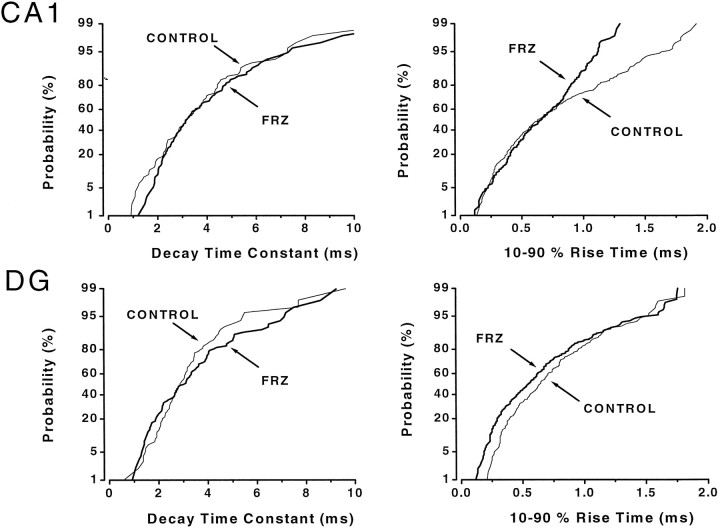

In contrast to the conductance at the peak, the decay time constants and 10–90% rise times of mIPSCs generated in CA1 and GCs did not change after FRZ withdrawal (Figs. 5, 6, Table 3). In summary, these data indicate that the frequency of occurrence and conductance of mIPSCs are decreased greatly after FRZ withdrawal in CA1, but not in GCs.

Fig. 5.

Example of unaltered mIPSCs kinetics on day 5 of FRZ obtained in CA1 and dentate gyrus (DG) granule cells recorded from vehicle- and FRZ-treated animals, respectively. Left panelsillustrate the lack of difference in the mIPSC decay time constants between control (thin lines; n = 96 IPSCs for CA1 and n = 98 IPSCs forDG) and FRZ-treated cells (thick lines;n = 96 IPSCs for CA1 andn = 95 IPSCs for DG). Theright panels show that, although there were fewer events with long rise times in this cell, the mean and median 10–90% rise time of mIPSCs were unaffected (also see Table 2 for pooled data) inCA1 neurons (n = 253 events for control and n = 279 events for FRZ withdrawal) andDG granule cells (n = 181 events for control and n = 252 events for FRZ withdrawal).

Fig. 6.

Average mIPSCs in vehicle- and FRZ-treatedCA1 pyramidal neurons and dentate gyrus (DG) granule cells. Top traces are average mIPSCs (n = 144 events) in a vehicle-treated CA1 neuron (1) and of 150 events in a CA1 pyramidal cell (1 of the 31 cells showing mIPSCs of a total 51 cells, of which 20 had no mIPSCs activity at all) recorded in a slice obtained from a rat after 5 d of FRZ withdrawal (2). Superimposition of traces 1 and 2 is shown in the right panel (1 + 2) on a faster time scale to demonstrate the absence of alteration in their kinetics (solid line is normalized trace2). Fitting the sum of single exponential rising and decaying functions to these averages (Soltesz and Mody, 1995) yielded rise time constants (τR) of 0.126 and 0.156 msec and decay time constants (τD) of 3.31 and 3.44 msec for control and FRZ-withdrawn preparations, respectively. The traces on thebottom panels depict average mIPSCs in twoDG granule cells (averages of n = 263 events for control and n = 123 events for FRZ withdrawal). The τR were 0.112 and 0.103 msec, whereas the τD were 3.07 and 3.18 msec in the two preparations, respectively. Cells were voltage-clamped at −60 mV.

Table 3.

Alteration of the conductance (g) and frequency of occurrence (Fr.) of mIPSCs in CA1 neurons at different days of withdrawal (WD) after chronic FRZ treatment

| Control | WD2 | WD3 | WD4 | WD5 | WD6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g (nS) | 0.78 ± 0.12 | 0.51 ± 0.18* | 0.35 ± 0.03** | 0.30 ± 0.09** | 0.31 ± 0.05** | 0.81 ± 0.06 |

| Fr. (Hz) | 22.9 ± 8.6 | 24.5 ± 8.1 | 7.8 ± 4.7* | 4.8 ± 2.1** | 4.1 ± 0.6** | 17.8 ± 8.2 |

| Number of cells | 18 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 31 | 5 |

Massive reductions in the conductance and frequency of occurrence were observed between 3 and 5 d of withdrawal. Note that, after 2 d of withdrawal, only a decrease in mIPSC conductance was observed in CA1 neurons. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Asterisks indicate statically significant differences (t test) from controls p < 0.01 (*) and p < 0.001 (**). Values without asterisks are not significantly different from controls (p > 0.05). During chronic BZ exposure, there were no differences between the doses of FRZ consumed by each animal.

The magnitude of the selective reduction of tonic inhibition in the CA1 region was dependent on the withdrawal time period (Table 3). The mean conductance of GABAA receptor-mediated mIPSCs decreased progressively from 2–5 d of withdrawal and was found to be statistically different over this period (p < 0.01). The mean frequency of occurrence became reduced only between days 3–5 of withdrawal but not after 2 d after the cessation of chronic BZ treatment. However, mIPSC properties returned to control values after 6 d of withdrawal. The time course of these actions is summarized in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to examine the effects of withdrawal from chronic BZ exposure on synaptic GABAAreceptor function by recording mIPSCs in the hippocampal CA1 and dentate gyrus region. After 3–5 d of withdrawal from oral FRZ treatment, we observed a massive loss of synaptic GABAAreceptor-mediated currents in CA1, but not in GCs. This effect was maximal after 5 d of withdrawal when 40% of CA1 neurons exhibited no mIPSCs, whereas in the remaining 60% of the neurons, mIPSCs occurred less frequently and had a reduced conductance.

Flurazepam prolongs mIPSCs

The properties of mIPSCs generated in CA1 and GCs of untreated and vehicle-treated animals were similar to those recorded previously by us and others in similar preparations (Mody et al., 1991; Cohen et al., 1992; Otis and Mody, 1992; De Koninck and Mody, 1994; Pitler and Alger, 1994; Soltesz and Mody, 1995). We found no differences between the properties of mIPSCs generated in GCs and CA1 neurons, apart from the relatively greater frequency of occurrence in CA1 neurons, which may indicate a greater release probability at, or a greater number of GABAergic synapses on, CA1 neurons (Li et al., 1992; Halasy and Somogyi, 1993; Buhl et al., 1994). Perfusion of FRZ (30 μm) prolonged the decay of mIPSCs without affecting their amplitude, rise time, or frequency of occurrence. This observation is consistent with a high degree of saturation of hippocampal synaptic GABAA receptors (Otis and Mody, 1992; Mody et al., 1994). The similar increase in mIPSC decay time constant induced by acute FRZ in control CA1 and GCs indicates that possible differences in the distribution of GABAA receptor subunits between the CA1 region and the dentate gyrus (Laurie et al., 1992; Persohn et al., 1992; Wisden et al., 1992; Fritschy et al., 1994) do not influence the modulation of synaptic GABAA receptor channels by this BZ.

BZ withdrawal modifies mIPSCs

Withdrawal from chronic exposure to FRZ led to a major reduction of the tonic action potential-independent inhibition in CA1 neurons but did not alter the properties of mIPSCs in GCs. In CA1 neurons a large decrease of the conductance and frequency of occurrence of mIPSCs was observed, but these effects were not accompanied by a change in their decay time constants, whereas in GCs recorded from the same slices, no changes in mIPSC properties were noted. The loss of mIPSCs in CA1 neurons after FRZ withdrawal extends the observations of previous studies to the level of synaptic GABAA receptors. The decreased number of GABA binding sites (Gallager et al., 1984; Marley and Gallager, 1989), the loss of certain GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs (Heninger et al., 1990; Kang and Miller, 1991; O’Donovan et al., 1992; Primus and Gallager, 1992; Tietz et al., 1993; Wu et al., 1994; Zhao et al., 1994a,b; Holt et al., 1995), the diminished potency of GABA on evoked field potentials (Xie and Tietz, 1992), and the reduction of evoked inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (Zeng et al., 1995) are all consistent with our findings of reduced GABAergic inhibition at individual CA1 synapses. However, the magnitude of the reduction of synaptic GABAA receptor channel function in the CA1 pyramidal neurons of our study is considerably greater than that detected previously by more indirect methods. The effects of FRZ withdrawal were time-dependent, reaching a maximum at 5 d of withdrawal and then recovered abruptly so that at 6 d of withdrawal the properties of mIPSCs approached those recorded in control cells. A recovery of evoked IPSPs 7 d after FRZ withdrawal also was noted by Zeng et al. (1995).

We have studied the full time course (2–6 d of withdrawal) of alterations in mIPSCs recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons. After 5 d of withdrawal, no mIPSCs could be recorded in 40% of CA1 neurons. In the remaining 60% of the neurons with recordable mIPSCs, a 95% reduction of frequency and 75% decrease in conductance were noted. Furthermore, at 3–5 d of withdrawal, the reduction of mIPSC frequency and conductance occurred in parallel, indicating a possible common underlying mechanism. We suggest that withdrawal from chronic FRZ treatment forces synaptic GABAA receptor channels into a nonfunctional state so that at many synapses all subsynaptic receptor channels become nonfunctional, whereas at other synapses only some fraction of the total number of receptor channels remains functional. On the basis of the 80% decrease in frequency, after 5 d of withdrawal only an estimated 12% of CA1 pyramidal cell GABA synapses possess functional GABAA receptor channels activated by action potential-independent GABA release. In this small fraction of functioning synapses, only 40% of GABAA receptor channels appear to be activated because mIPSC conductance was reduced by 60%. Our conclusions are supported by the stringent criteria used to detect all small amplitude mIPSCs. The failure of the stationary noise analysis to discern mIPSCs collapsed into the baseline noise indicates the unlikely possibility that small events were missed by our detection. The reduced mIPSC conductance is consistent with a reduction in the number of functional postsynaptic GABAA receptors on inhibitory synapses of CA1 pyramidal cells. Because the mIPSCs we studied are independent of presynaptic action potentials or calcium entry, alterations in any of these presynaptic parameters are unlikely to have played a role in the observed changes.

It is still an open question as to how rapidly the nonfunctional GABAA receptors can be reconverted into functional ones. Based on our data at 6 d after FRZ withdrawal, this must happen within 24 hr. The rapid reversal of withdrawal effects by the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil (Gonsalves and Gallager, 1985,1988) may indicate that the conversion to functional receptors could be even more rapid (<1 hr). Accordingly, nonfunctional GABAAreceptors might be present at the level of the membrane during withdrawal. Therefore, the decreased function of synaptic GABAA receptor channels observed here may not necessarily result from an active process of receptor removal but, rather, may involve a “masking” mechanism. Alternatively, the reduction in the frequency and conductance of mIPSCs may stem from rapidly reversible alterations in the subunit composition of synaptic GABAAreceptor channels (Klein and Harris, 1996). Because our findings demonstrate a total absence of mIPSCs in some neurons, such subunit alterations, if present, should render GABAA receptors nonfunctional.

Region specificity of the withdrawal

Our findings are the first demonstration of a region-specific alteration of GABAergic inhibitory synaptic transmission during withdrawal from chronic benzodiazepine treatment. A possible explanation for the region specificity may be the inability of FRZ to reach equally the CA1 region and the dentate gyrus. This possibility is extremely unlikely, because there is no experimental evidence demonstrating that systematically administered excitatory or inhibitory receptor agonists/antagonists reach the CA1 region and the dentate gyrus in a quantitatively different manner. The regional differences thus may stem from distinct GABAA receptor subunit composition between the CA1 region and the dentate gyrus of the adult rat hippocampus (Laurie et al., 1992; Persohn et al., 1992; Wisden et al., 1992; Mertens et al., 1993; Fritschy et al., 1994). In particular, α4 and δ subunits are more abundant in the dentate gyrus, whereas α5 is expressed predominantly in CA1. Considering this heterogeneity, it is conceivable that some region-specific subunit composition-dependent alterations of synaptic GABAAreceptors occur after BZ withdrawal. Changes in hippocampal GABAA receptor subunits during tolerance/withdrawal to BZs include a downregulation of the expression of α1, α5, β2, β3, and γ2 (Tietz et al., 1993; Zhao et al., 1994a,b; Impagnatiello et al., 1996). The α5 subunit mRNAs specific to the CA1 region are downregulated consistently after FRZ treatment (O’Donovan et al., 1992; Zhao et al., 1994b). A replacement of certain α-subunits with another type of α-subunit or a different type of subunit altogether has been proposed to take place after chronic BZ treatment (Klein and Harris, 1996) but would not adequately explain the complete dysfunction of most synaptic GABAA receptors observed after 5 d withdrawal in our experiments. Alternatively, a reorganization of synaptic GABAA receptor subunits during and after chronic BZ treatment could produce drastic changes in their regulation by intracellular effectors such as kinases or phosphatases (Brown and Bristow, 1996), particularly because specific phosphorylation recognition consensus sequences exist on the intracellular loops of specific GABAA receptor subunits (Macdonald and Olsen, 1994).

In summary, we have demonstrated a decrease in tonic GABAergic synaptic inhibition in the CA1 region, but not in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampal formation after FRZ withdrawal. Our data are consistent with a reversible formation of “silent” inhibitory synapses during benzodiazepine withdrawal.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NS-30549 to I.M. S.R.W. is supported by a fellowship from the American Epilepsy Foundation. P.P. is supported in part by the Philippe Foundation. We thank Dr. R. W. Olsen for valuable comments on this manuscript and Brian K. Oyama and Michael T. Kim for excellent technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Istvan Mody, Reed Neurological Research Center, University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine, Department of Neurology, 710 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1769.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown MJ, Bristow DR. Molecular mechanisms of benzodiazepine-induced downregulation of GABAA receptor α1 subunit protein in rat cerebellar granule cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:1103–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buhl EH, Halasy K, Somogyi P. Diverse sources of hippocampal unitary inhibitory postsynaptic potentials and the number of synaptic release sites. Nature. 1994;368:823–828. doi: 10.1038/368823a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen GA, Doze VA, Madison DV. Opioid inhibition of GABA release from presynaptic terminals of rat hippocampal interneurons. Neuron. 1992;9:325–335. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Koninck Y, Mody I. Noise analysis of miniature IPSCs in adult rat brain slices; properties and modulation of synaptic GABAA receptor channels. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1318–1335. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.4.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.File SE. The biology of benzodiazepine dependence. In: Hallstrom C, editor. Benzodiazepine dependence. Oxford UP; Oxford: 1993. pp. 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fritschy J-M, Paysan J, Enna A, Möhler H. Switch in the expression of rat GABAA-receptor subtypes during postnatal development: an immunohistochemical study. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5302–5324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05302.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallager DW, Primus RJ. Benzodiazepine tolerance and dependence: GABAA receptor complex locus of change. Biochem Soc Symp. 1993;59:135–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallager DW, Lakoski JM, Gonsalves SF, Rauch SL. Chronic benzodiazepine treatment decreases postsynaptic GABA sensitivity. Nature. 1984;308:74–77. doi: 10.1038/308074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonsalves SF, Gallager DW. Spontaneous and RO 15–1788-induced reversal of subsensitivity to GABA following chronic benzodiazepines. Eur J Pharmacol. 1985;110:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonsalves SF, Gallager DW. Persistent reversal of tolerance to anticonvulsant effects and GABAergic subsensitivity by a single exposure to benzodiazepine antagonist during chronic benzodiazepine administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;244:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halasy K, Somogyi P. Distribution of GABAergic synapses and their targets in the dentate gyrus of rat: a quantitative immunoelectron microscopic analysis. J Hirnforsch. 1993;34:299–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heninger C, Saito N, Tallman JF, Garrett KM, Vitek MP, Duman RS, Gallager DW. Effects of continuous diazepam administration on GABAA subunit mRNA in rat brain. J Mol Neurosci. 1990;2:101–107. doi: 10.1007/BF02876917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt RA, Bateson AN, Martin IL. GABAA receptor subunit mRNA levels are differentially affected by chronic diazepam and abecarnil exposure. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1995;21:1590. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Impagnatiello F, Pesold C, Longone P, Caruncho H, Fritschy JM, Costa E, Guidotti A. Modifications of γ-aminobutyric acid, receptor subunit expression in rat neocortex during tolerance to diazepam. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:822–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang I, Miller LG. Decreased GABAA receptor subunit mRNA concentrations following chronic lorazepam administration. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1285–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb09781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein RL, Harris RA. Regulation of GABAA receptor structure and function by chronic drug treatments in vivo and with stably transfected cells. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1996;70:1–15. doi: 10.1254/jjp.70.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laurie DJ, Wisden W, Seeburg PH. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. III. Embryonic and postnatal development. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4151–4172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04151.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li XG, Somogyi P, Tepper JM, Buzsáki G. Axonal and dendritic arborization of an intracellularly labeled chandelier cell in the CA1 region of rat hippocampus. Exp Brain Res. 1992;90:519–525. doi: 10.1007/BF00230934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macdonald RL, Olsen RW. GABAA receptor channels. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:569–602. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marley RJ, Gallager DW. Chronic diazepam treatment produces regionally specific changes in GABA-stimulated chloride influx. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;159:217–223. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mertens S, Benke D, Möhler H. GABAA receptor populations with novel subunit combinations and drug-binding profiles identified in brain by α5- and δ-subunit-specific immunopurification. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5965–5973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mody I, Tanelian DL, MacIver MB. Halothane enhances tonic neuronal inhibition by elevating intracellular calcium. Brain Res. 1991;538:319–323. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mody I, De Koninck Y, Otis TS, Soltesz I. Bridging the cleft at GABA synapses in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:517–525. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Donovan MC, Buckland PR, Spurlock G, McGuffin P. Bi-directional changes in the levels of messenger RNAs encoding γ-aminobutyric acid A receptor α subunits after flurazepam treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;226:335–341. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(92)90051-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otis TS, Mody I. Modulation of decay kinetics and frequency of GABAA receptor-mediated spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents in hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 1992;49:13–32. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90073-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otis TS, Staley KJ, Mody I. Perpetual inhibitory activity in mammalian brain slices generated by spontaneous GABA release. Brain Res. 1991;545:142–150. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91280-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persohn E, Malherbe P, Richards JG. Comparative molecular neuroanatomy of cloned GABAA receptor subunits in the rat CNS. J Comp Neurol. 1992;326:193–216. doi: 10.1002/cne.903260204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitler TA, Alger BE. Depolarization-induced suppression of GABAergic inhibition in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells: G-protein involvement in a presynaptic mechanism. Neuron. 1994;13:1447–1455. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90430-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Primus RJ, Gallager DW. GABAA receptor subunit mRNA levels are differentially influenced by chronic FG 7142 and diazepam exposure. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;226:21–28. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(92)90078-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoch P, Moreau JL, Martin JR, Haefely WE. Aspects of benzodiazepine receptor structure and function with relevance to drug tolerance and dependence. Biochem Soc Symp. 1993;59:121–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soltesz I, Mody I. Ca2+-dependent plasticity of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents after amputation of dendrites in central neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:1763–1773. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.5.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soltesz I, Smetters DK, Mody I. Tonic inhibition originates from synapses close to the soma. Neuron. 1995;14:1273–1283. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staley KJ, Otis TS, Mody I. Membrane properties of dentate gyrus granule cells: comparison of sharp microelectrode and whole-cell recordings. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:1346–1358. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.5.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tietz EI, Huang X, Weng X, Rosenberg HC, Chiu TH. Expression of α1, α5, and γ2 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs measured in situ in rat hippocampus and cortex following chronic flurazepam administration. J Mol Neurosci. 1993;4:277–292. doi: 10.1007/BF02821559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wisden W, Laurie DJ, Monyer H, Seeburg PH. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. I. Telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1040–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01040.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Y, Rosenberg HC, Chiu TH, Zhao TJ. Subunit- and brain region-specific reduction of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs during chronic treatment of rats with diazepam. J Mol Neurosci. 1994;5:105–120. doi: 10.1007/BF02736752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie XH, Tietz EI. Reduction in potency of selective γ-aminobutyric acid A agonists and diazepam in CA1 region of in vitro hippocampal slices from chronic flurazepam-treated rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:204–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeng X, Tietz EI. Decreased amplitude and frequency of spontaneous IPSCs recorded in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons after chronic flurazepam treatment. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1995;21:1589. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng X, Xie XH, Tietz EI. Reduction of GABA-mediated inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons following oral flurazepam administration. Neuroscience. 1995;66:87–99. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00558-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao TJ, Chiu TH, Rosenberg HC. Decreased expression of γ-aminobutyric acid type A/benzodiazepine receptor β subunit mRNAs in brain of flurazepam-tolerant rats. J Mol Neurosci. 1994a;5:181–192. doi: 10.1007/BF02736732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao TJ, Chiu TH, Rosenberg HC. Reduced expression of γ-aminobutyric acid type A/benzodiazepine receptor γ2 and α5 subunit mRNAs in brain regions of flurazepam-treated rats. Mol Pharmacol. 1994b;45:657–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]