Abstract

Acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) are present at the top of the postsynaptic membrane of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) at very high density, possibly anchored to cytoskeletal elements. The present study investigated whether AChR degradation is affected in animals lacking dystrophin, a protein that is an integral part of the cytoskeletal complex and is missing in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. The animal model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the mutant mdx mouse, was used to determine whether disruption of the cytoskeleton, caused by the absence of dystrophin, affects AChR degradation. Of the two populations of junctional AChRs, Rs (expressed in innervated adult muscles) and Rr (expressed in embryonic or denervated muscles), only Rs are affected in mdx animals. In innervatedmdx soleus, diaphragm, and sternomastoid muscles, the AChRs have an accelerated degradation rate (t1/2 of ∼3–5 d), similar to that acquired by Rs in control muscles after denervation. The Rs inmdx NMJs do not accelerate further when the muscles are denervated. The absence of dystrophin does not affect the degradation rate of the Rr AChRs (t1/2 of 1 d), which are expressed after denervation in mdx as in control muscles. These results suggest that dystrophin or an intact cytoskeletal complex may be required for neuronal stabilization of Rs receptors at the adult neuromuscular junctions.

Keywords: cAMP, forskolin, soleus, diaphragm, sternomastoid, turnover

The metabolic degradation of acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) at the vertebrate neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is under neuronal regulation (for review, see Salpeter, 1987). AChRs, synthesized and inserted in normal innervated adult muscles, have a slow degradation rate (t1/2 of 8–10 d). These receptors (called Rs) accelerate to at1/2 ∼3–5d after denervation but are restabilized by reinnervation (Salpeter et al., 1986; Andreose et al., 1993). As the accelerated Rs degrade after denervation, they are replaced by AChRs newly synthesized in the denervated muscle (Shyng and Salpeter, 1989), 90% of which are Rr (t1/2 ∼1 d). Reinnervation does not stabilize the Rr to adult innervated Rs values (Shyng and Salpeter, 1990), although recent studies indicate that reinnervation can stabilize Rr to the intermediatet1/2 of ∼3 d (M. M. Salpeter and M. Szabo, unpublished results). Eventually, however, Rr are downregulated by innervation (Fumagalli et al., 1990; Andreose et al., 1993). The mechanism by which the nerve differentially regulates Rs and Rr degradation is not yet known, but both muscle activity and trophic factors seem to be involved (Avila et al., 1989; Garcia et al., 1990;Shyng et al., 1991; Andreose et al., 1993; O’Malley et al., 1993,1997; Xu and Salpeter, 1995).

AChRs are anchored at the NMJ through a cytoskeletal network (for review, see Froehner, 1986; Hall and Sanes, 1993; Matsumura and Campbell, 1994; Apel and Merlie, 1995). One protein that is part of this cytoskeletal network is dystrophin, the 400 kDa protein from a gene missing in Duchenne muscular dystrophic patients (Hoffman et al., 1987; Koenig et al., 1987) and in the mutant mdx mice (Sicinski et al., 1989). The C termini of dystrophin and utrophin, a dystrophin-related protein (Ohlendieck et al., 1991; Bewick et al., 1992; Lebart et al., 1995), bind to a complex of glycoproteins that contain transmembrane components and link the subsarcolemmal cytoskeleton to the basal lamina (Ervasti and Campbell, 1991; Matsumura and Campbell, 1994). The dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex may also be associated with rapsyn (the 43 kDa protein) that colocalizes with AChRs (Burden et al., 1983; Apel et al., 1995). AChRs may also be connected with other cytoskeletal proteins, such as F-actin, through a 58 kDa protein/syntrophin and β-spectrin (Froehner et al., 1987;Bloch and Pumplin, 1988; Bloch and Morrow, 1989; Bloch et al., 1991). F-actin, in turn, is linked to dystrophin (Lebart et al., 1995). AChR stability may be associated with cytoskeletal anchoring (Salpeter and Loring, 1985); however, the role of individual cytoskeletal proteins in this process is not known.

In the present study we examined the role of dystrophin in AChR degradation by comparing mdx and normal muscles from the same mouse strain (C57BL10). In the mutant animals there is a marked effect on the stability of the Rs AChRs, synthesized in innervated muscle, but not on the Rr, expressed after denervation. The degradation rates of Rs AChRs in innervated adult mdx mouse muscles were significantly faster than those in the controls, resembling the values normally seen for Rs after denervation. Our results suggest that dystrophin (or its cytoskeletal complex) is required for neuronal stabilization of Rs receptors in adult muscles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Degradation of AChRs in adult muscles. Female (10–12 weeks old) mdx mice and controls from the same mouse strain (C57BL10; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were bred in our animal facility. [We confirmed by Western blot analysis with an antibody against the dystrophin C terminal (Novacastra, Burlingame, Ca) that themdx mice used in this study did indeed lack dystrophin.] Diaphragm, soleus, and sternomastoid muscles were denervated in each mouse, following the Cornell Guidelines approved by the Cornell University Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 90-109-97). The left hemi-diaphragms were denervated under ether/methoxyflurane anesthesia (Xu and Salpeter, 1995) by pulling out the left phrenic nerve with a glass hook inserted through a small incision in the thoracic wall and cutting a piece of the exposed nerve. The right sternomastoid and soleus muscles were denervated under nembutal anesthesia by cutting out a section of the nerve (spinal accessory or sciatic) and tucking the stump under an adjacent muscle. Innervated muscles were compared with contralateral denervated ones.

Selective labeling of Rs or Rr in vivo. To selectively label only the Rs AChRs present in innervated muscle, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with 150 μl of 0.5 μm125I-α-bungarotoxin (125I-α-BTX) (DuPont NEN, Boston, MA) at the time of denervation, before any Rr are inserted. By this injection procedure ∼60% of the surface AChRs on mouse diaphragms were labeled (Wetzel and Salpeter, 1991). For labeling Rr, the left diaphragm muscles were denervated in both control andmdx mice. Twenty-one days later, when the preexisting Rs have degraded and the receptors are predominantly newly synthesized Rr (Shyng et al., 1991), the receptors were labeled with 150 μl of 0.5 μm125I-α-BTX, injected intraperitoneally as described above.

Determining degradation rates. At different days after labeling, the mice were killed by cervical dislocation under ether anesthesia and perfused transcardially with 0.1 m phosphate buffer. Muscles were removed, washed, and counted on a gamma counter (Beckman). The radioactivity remaining on the muscle at different days after labeling was normalized to 100% on day 2 and plotted semilogarithmically. A least squares fit was then used to determine whether the data fit a single or double exponential as described previously (O’Malley et al., 1997). The slope(s) of such plots gives the degradation rates of the AChR populations (Fambrough, 1979;Salpeter, 1987), and the intercept on the y-axis gives their relative content.

Organ culture. Organ culture was used to study the effect of altering external factors on both Rs and Rr degradation in adult denervated muscles. We used diaphragm muscles in organ culture because they are thin and flat enough to allow chemicals to penetrate through the tissue (Somerville and Wang, 1988) and because our earlier studies on the effect of elevating cAMP levels was performed on these muscles (Shyng et al., 1991; Xu and Salpeter, 1995). To prepare diaphragms for organ culture, the mice were cervically dislocated under ether anesthesia and perfused transcardially with oxygenated Kreb’s buffer (125 mm NaCl, 4.7 mm KCl, 20 mmHEPES, 5.5 mmd-glucose, pH 7.4), and their diaphragms were removed, washed, and pinned to a mesh attached to Sylgard dishes (Wollcott-Park, Rochester, NY). The organ culture medium was as optimized by Wetzel and Salpeter (1991). The medium was changed daily, and the radioactivity released into it was counted in a gamma counter (Beckman). On the last day, residual radioactivity remaining on the muscles was also counted, and the sum of all the daily counts gave the total radioactivity on day 0. Residual radioactivity for each successive day was calculated by successive subtractions of the daily releases as described in Xu and Salpeter (1995). When residual radioactivity remaining on muscles with time after labeling is plotted on a semi-log scale, the slope gives a degradation rate as described above.

The effect of elevating intracellular cAMP was determined by adding cAMP analog, dibutyryl cAMP (dB-cAMP; 500 μm) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), or the adenylate cyclase activator forskolin (40 μm) (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) to the medium daily starting on day 3 in culture.

Primary cell culture. Primary cell culture was used to study Rr AChRs. Leg muscles were excised from decapitated, 4-week oldmdx and control mice. Cell cultures were prepared according to O’Malley et al. (1993, 1996), with minor modifications. Briefly, the muscles were digested in 0.1% collagenase (Sigma) in Kreb’s buffer at 37°C for 2–3 hr and plated in DMEM (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with penicillin (200 U/ml) and streptomycin (200 μg/ml) with 10% FBS (Life Technologies) for 3 d before changing to DMEM fusion medium containing 5% horse serum (Life Technologies) (Dickson et al., 1992). On day 3 the AChRs were incubated with 1 nm125I-α-BTX in 1 ml of Kreb’s buffer for 1 hr and washed five times (∼5 min each) in the buffer. Nonspecific binding was determined by adding 1 μmnonradioactive α-BTX. The fusion medium was removed daily, counted on a gamma counter, and replaced by fresh medium. On day 8, the medium as well as the cells were counted, the nonspecific binding was subtracted from the specific binding, and a degradation curve was obtained as described for cells in organ culture.

Experimental manipulations included adding dB-cAMP (500 μm) into the culture medium daily, starting on the day of labeling. Data were normalized to 100% on day 0 and fitted to two exponentials according to O’Malley et al. (1993).

cAMP assay. Diaphragm, soleus, and sternomastoid muscles were removed, the two halves of the diaphragm were separated, and all the muscles were placed in organ culture as described above for diaphragm muscles. Muscles from one side were treated with 40 μm forskolin, whereas those from the contralateral side were kept as an untreated control. On the next day, the muscles were washed and ground in lysis buffer (Tris 20 mm, EDTA 2 mm, leupeptin 25 μg/ml, aprotinin 2 μg/ml, pepstatin 10 μg/ml, Pefabloc 1 mm, 3-isobutyl-methyl-xanthine 0.5 mm, pH 7.2) and then centrifuged for 30 min (10,000 ×g) at 4°C. The supernatant was assayed for protein concentration (Bradford), and the cAMP concentration in the supernatant was assayed on the basis of competitive immunoprecipitation using a cAMP assay kit (DuPont NEN). The amount of cAMP was expressed as picomole per milligram of soluble proteins.

RESULTS

Rs degradation

Before denervation, Rs AChRs were labeled on sternomastoid, soleus, and diaphragm muscles. The degradation curves showed that in all three innervated muscles the Rs degradation rate was faster inmdx than in control muscles (Table1, Fig. 1). For studies on the behavior of such preexisting Rs after denervation, mice were injected with 125I-α-BTX at the time of denervation (before any Rr AChRs were inserted), and the degradation rates of AChRs on the denervated muscles were compared with those on the contralateral innervated muscles. Because of a shortage ofmdx muscles, not all time points were included in each experiment, yet all obtained a value for day 2, which was normalized to 100%. The data from different experiments could thus be pooled. The number of muscles used at each data point varies from 3 to 10.

Table 1.

Degradation rates of Rs AChRs in adult mdx and control muscles

| Muscle | Innervated | After denervation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control t1/2 (d) | mdx t1/2 (d) | Control t1/2(d) | mdx t1/2 (d) | |

| Sternomastoid | 9.9 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 3.8 |

| Soleus | 12.7 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 4.5 |

| Diaphragm | 9.3 | 5.7 | 4.2 | 6.4 |

The degradation rates were obtained from the slope of the best fit to the pooled data as described in the text. Muscles used for these experiments ranged from 3 to 8 for the control mice and 3 to 11 for themdx mice.

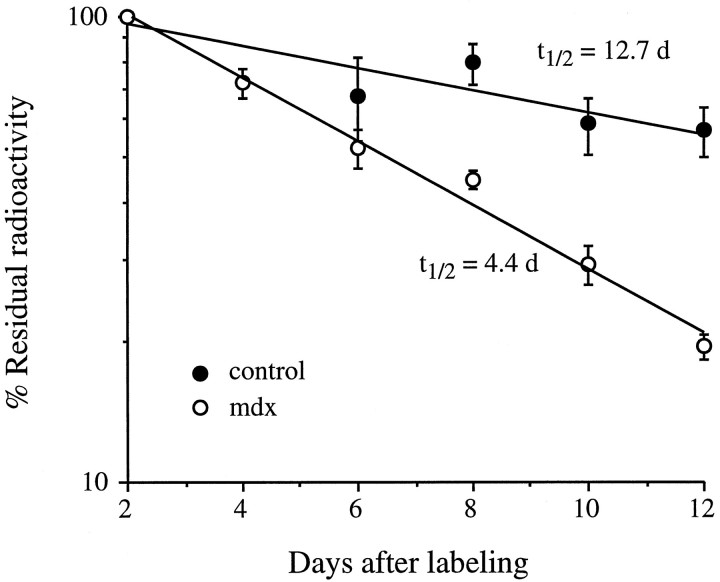

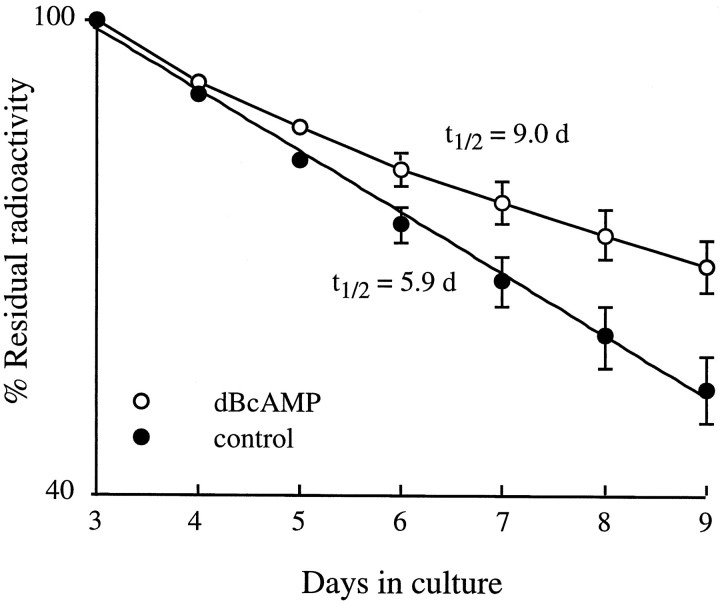

Fig. 1.

In vivo degradation rates of Rs AChRs in soleus muscles are faster in mdx (○) than in control (•) muscles. AChRs were labeled with 125I-α-BTX and counted at different days thereafter. The slope of residual radioactivity on a semi-log plot gives the rate of AChR degradation. Each data point is presented as mean ± SEM (n= ≥3).

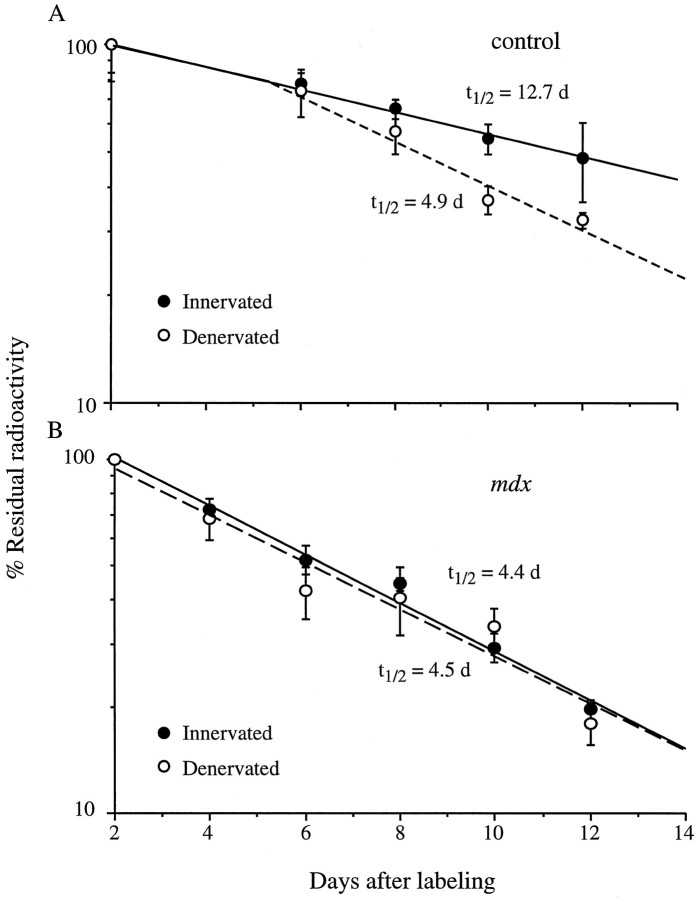

The degradation rate of the Rs AChRs in innervated mdxsoleus muscles had a t1/2 of 4.4 d compared with 12.7 d in controls (Fig. 1) and was similar to that seen for preexisting Rs in controls after denervation (Fig.2). Furthermore, although the Rs in the control soleus muscles accelerated with a ∼5 d delay after denervation, as described previously for these muscles (Bevan and Steinbach, 1983; Andreose et al., 1993), the Rs on mdxmuscles did not accelerate further after denervation but maintained their already accelerated predenervation degradation values.

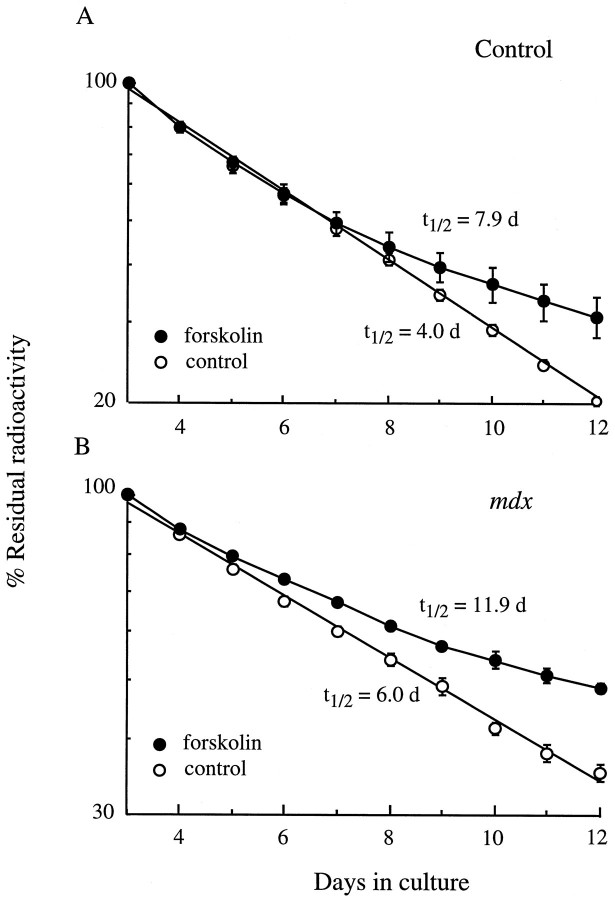

Fig. 2.

Denervation accelerates Rs AChR degradation in control muscles (A) but not in mdxmuscles (B). Right soleus muscles of adult mice were denervated at time of AChR labeling with 125I-α-BTX. Contralateral muscles served as innervated controls. Data points are mean ± SEM (n = ≥3).

Although the absolute Rs degradation rate was higher in the denervated diaphragms than in the denervated soleus or sternomastoid muscles, similar innervation/denervation ratios were seen in all three muscles (Table 1). In all cases, the accelerated Rs in mdx animals degraded with a single exponential, and there was no indication that a second more rapidly degrading Rr population was present. Thus in the NMJs of both the innervated mdx muscles and in controls, the junctional AChRs consist of a single population of Rs, yet the neuronal stabilization of the Rs, usually seen in normal innervated muscles, is absent in mdx mice.

Rr degradation

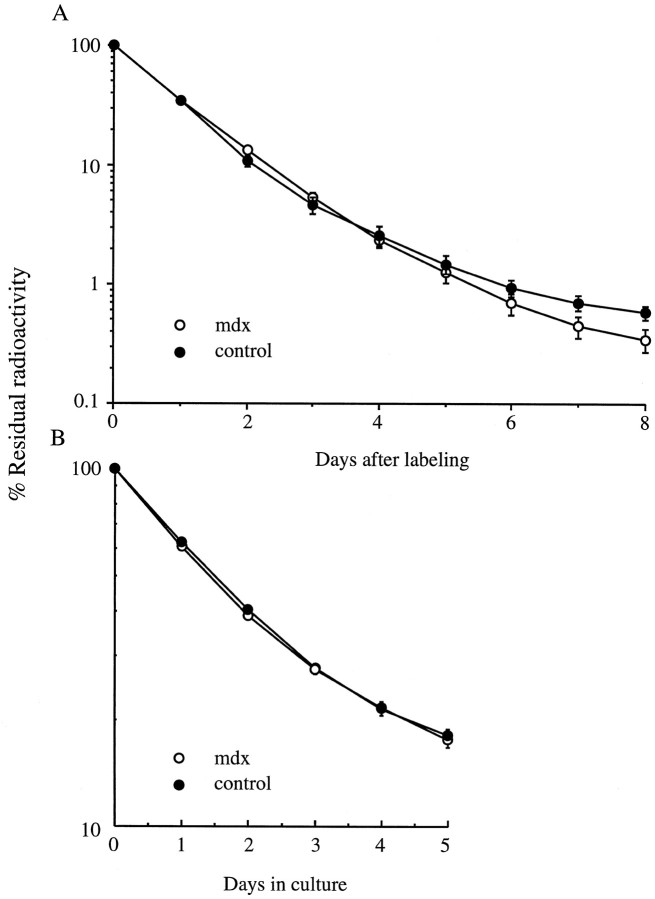

To determine whether the lack of dystrophin has a general effect on all AChRs or is restricted to Rs only, we examined the degradation rate of Rr AChRs that are synthesized after denervation and in tissue-cultured muscle. For that purpose, we used organ culture to study AChRs on long-term (21 d) denervated diaphragms and tissue culture to study the AChRs on aneural myotubes derived from leg muscles. In both systems the AChRs had the two component degradation curves characteristic of AChRs synthesized in noninnervated muscle (Shyng and Salpeter, 1990; O’Malley et al., 1993, 1997). We saw no difference between mdx and control muscles in the degradation rates of either the fast component Rr or the small (10%) slow component of accelerated Rs, normally seen in such muscles (Figs.3, 5). These results show that the absence of dystrophin does not influence Rr degradation in either tissue-cultured or long-term denervated muscles and seems only to prevent the neuronal stabilization of Rs in innervated muscles.

Fig. 3.

The degradation rates of Rr AChRs are the same inmdx as in control muscles. A, Leg muscles in cell culture (3 experiments with 6 dishes each); B, long-term denervated diaphragm muscles in organ culture: control (•) (n = 4) and mdx (○) (n = 3) mice. Overall the degradation rate of Rr in denervated muscles in organ culture is slower than that in tissue-cultured muscles, but in both systems there is no difference between Rr in control and mdx muscle. Data points are mean ± SEM. In all figures, SEM is not seen when smaller than symbol.

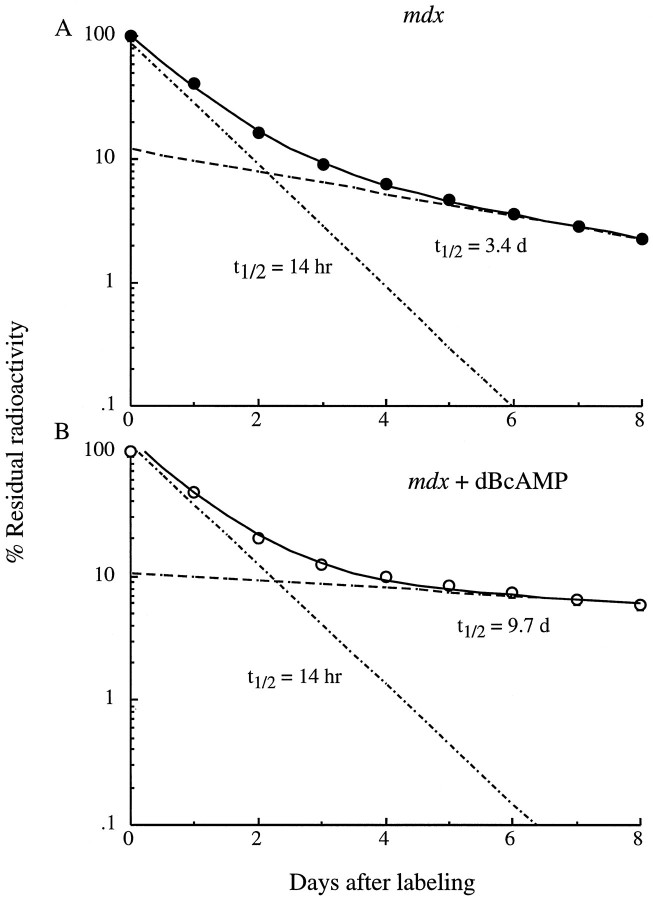

Fig. 5.

dB-cAMP stabilizes the slow component (Rs AChR) ofmdx muscles labeled on day 6 in cell culture.A, The degradation data are best fit (least squares) by the sum (solid line) of two exponentials: 90% constitutes a fast component (Rr; t1/2 ∼14 hr) and 10% a slow component (accelerated Rs;t1/2 of 3.4 d); B, dB-cAMP stabilized the slow component to at1/2 of 9.7 d without affecting the fast component or altering the ratio of the two populations. Data points are mean ± SEM (n = 6).

Stabilization of Rs AChRs by cAMP in mdx muscles

As indicated above and in Figures 1 and 2, Rs AChRs inmdx muscles are in the accelerated form even in innervated adult muscles, resembling that usually seen for preexisting AChRs after denervation. The mechanism whereby Rs is destabilized in adultmdx innervated muscle and how (or whether) dystrophin affects this is not known. Previous work (Shyng et al., 1991) has shown that elevation of intracellular cAMP in denervated muscles by both dB-cAMP and forskolin can mimic the effect of innervation in stabilizing accelerated Rs through a protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent pathway (Xu and Salpeter, 1995). We reasoned that if mdxmuscles lack the target for cAMP, this could explain why mdxRs are not stable even in innervated muscles. Using diaphragm muscles in organ culture, we examined the effect of dB-cAMP and forskolin on the accelerated Rs receptors in mdx muscles labeled at the time of denervation.

Figure 4 shows that 500 μmdB-cAMP was able to stabilize the accelerated Rs receptors inmdx muscles, as shown previously for normal muscles (Shyng et al., 1991; Xu and Salpeter, 1995). In addition, as seen previously in cultures from albino rats (O’Malley et al., 1993), dB-cAMP was able to stabilize the Rs receptors (∼10% of total population) onmdx muscles in cell culture (Fig.5A,B) without affecting the Rr population. These results show that Rs in mdx muscles are capable of responding to elevation of intracellular cAMP, and therefore the dB-cAMP regulating pathway is intact in the mdxmuscles.

Fig. 4.

dB-cAMP stabilized Rs AChRs in denervatedmdx muscle. Adult innervated mdxdiaphragm muscles were labeled with 125I-α-BTX at time of denervation to selectively label Rs. Muscles were placed in organ culture 6 d later, at a time when the control Rs had already undergone denervation-induced acceleration. dB-cAMP (500 μm) was added daily from day 3. Spontaneous fibrillation was used to verify muscle viability. Residual radioactivity, normalized to 100% on day 3 and plotted on a semi-log scale, gives the degradation rate from the slope. dBcAMP stabilized the degradation rate of the mdx Rs receptors to that of innervated controls (Table 1). Each data point is mean ± SEM (n = ≥3).

Because elevation of cAMP was able to stabilize the receptors inmdx muscles, we asked whether in the dystrophin-deficientmdx mice other proteins, such as adenylate cyclase, which regulates the synthesis of cAMP in vivo, may be affected. Earlier reports had indeed suggested that adenylate cyclase in dystrophic muscles were insensitive to stimulation by catecholamines or sodium fluoride (Witkowski, 1986). We therefore tested the effect of the adenylate cyclase activator forskolin on the degradation rate of the receptors in denervated diaphragm muscles. We found that forskolin was able to stabilize the accelerated receptors in mdx as in control muscles (Fig. 6). Thus the adenylate cyclase pathway for stabilizing Rs was functioning inmdx muscles, although as suggested by Witkowski (1986), the sensitivity to all factors may not be as in controls.

Fig. 6.

Forskolin, the activator of adenylate cyclase, stabilizes the AChRs in both control (A) andmdx (B) diaphragm muscles in organ culture. Diaphragm muscles were treated with 40 μmforskolin, starting on day 3 (n = 6). In both cultures, the half-lives of the AChRs doubled after forskolin treatment.

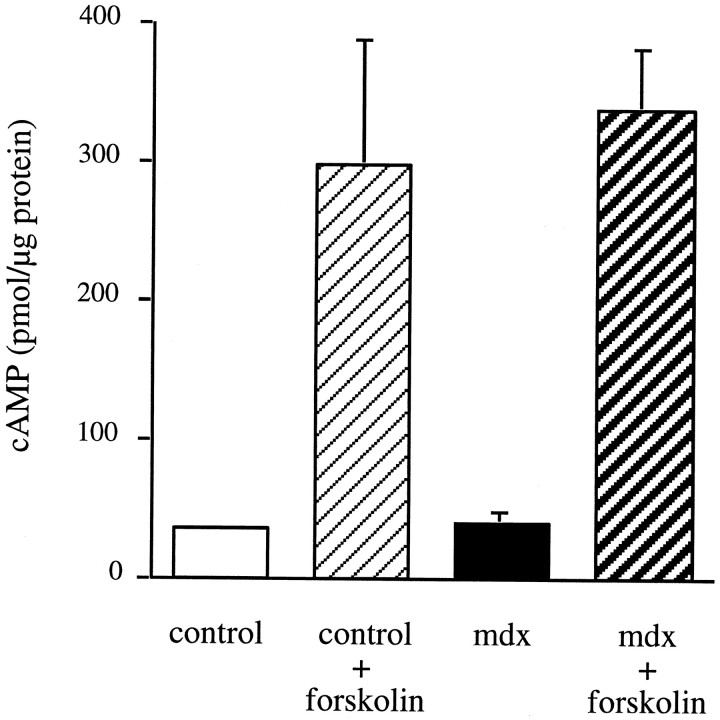

cAMP levels in mdx mice

Using the in vitro cAMP assay described in Materials and Methods, we determined the basal level of cAMP in the innervatedmdx muscles, and the extent to which forskolin treatment elevates the cAMP levels, and found them to be as in controls (Fig.7). Similar results were also obtained in diaphragms and sternomastoid muscles (Table2). Therefore, it is unlikely that the fast degradation rate of AChRs in mdx muscles is caused by a lower level or the lack of responsiveness of cAMP.

Fig. 7.

mdx and control muscles have the same amount of cAMP in innervated soleus muscles, and their adenylate cyclase can be activated equally with forskolin. In mdxmuscles, there was 40 ± 12 pmol/mg soluble cAMP protein (mean ± SEM; n = 3) compared with 35 ± 2.4 pmol/mg cAMP soluble protein (mean ± SEM;n = 3) in controls. Treatment with 40 μm forskolin overnight caused the cAMP level to increase to 337 ± 49 pmol/mg soluble protein (average ± range;n = 2) in mdx muscles and to 298 ± 93 pmol/mg soluble protein (average ± range;n = 2) in controls.

Table 2.

Effect of forskolin in elevating cAMP

| Muscle | Basal level (pmol/mg soluble protein) | Forskolin treatment (pmol/mg soluble protein) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | mdx | Control | mdx | |

| Sternomastoid | 15.0 ± 2.6 | 55.0 ± 17.0 | 323.0 ± 20.0 | 174.5 ± 52.5 |

| (n = 3) | (n = 2) | (n = 2) | (n = 2) | |

| Soleus | 35.3 ± 2.4 | 40.0 ± 12.0 | 298.0 ± 93.0 | 336.5 ± 48.5 |

| (n = 3) | (n = 3) | (n = 2) | (n = 2) | |

| Diaphragm | 29.0 ± 0.6 | 54.7 ± 14.7 | 128.0 | 124.0 ± 16.0 |

| (n = 3) | (n= 3) | (n = 1) | (n = 2) | |

Mean ± SEM when n = 2.

DISCUSSION

AChRs at adult mouse NMJs can be divided into two populations, Rs and Rr, on the basis of their degradation behavior. The Rs are synthesized mainly in innervated muscle and are maintained in a stable form by the presence of the nerve. In the absence of the nerve, as after denervation, the Rs are in an accelerated form (t1/2 of ∼3–5 d). At no time do the Rs go to a t1/2 of 1 d, which is characteristic of embryonic receptors (Levitt and Salpeter, 1981; Stiles and Salpeter, 1997). The Rr (t1/2 of 1 d) are synthesized in denervated muscle. In general the degradation curve of AChRs synthesized in denervated muscle is characterized by a double exponential decay (Shyng and Salpeter, 1990), indicating that more than one AChR population is present (e.g., Figs. 3, 5). These consist of the embryonic Rr (90% of total) and a small slower component, behaving as accelerated Rs (10% of total).

We report that the degradation of Rs in innervated muscle is aberrant in mdx mice, but no defect was seen in the Rr or accelerated Rs of denervated muscle. The degradation rate of Rs in innervated adultmdx muscle resembles that of accelerated Rs seen after denervation in normal muscle and does not accelerate further after denervation. Yet in respect to the AChR species being synthesized, the innervated mdx NMJ does not resemble the denervated junction. The Rs in innervated mdx muscle constitute a single population, with no indication of more rapidly degrading AChRs being present (compare Figs. 1 and 5). Thus the mdx animal seems to lack the neural mechanism whereby the nerve keeps the adult innervated Rs AChRs in its stabilized form. This suggests that neuronal stabilization of adult AChRs may require the presence of dystrophin or the integrity of the cytoskeletal matrix that includes dystrophin.

Unfortunately we were not able to determine any mechanism whereby dystrophin is involved in normal Rs stabilization and can only speculate on possible defects in mdx mice associated directly or indirectly with dystrophin. Normally dystrophin is distributed throughout muscle fibers but is concentrated at the NMJ (Watkins et al., 1988), particularly in synaptic troughs (Byers et al., 1991; Sealock et al., 1991; Bewick et al., 1992) in which the receptor density is low (Fertuck and Salpeter, 1974; Salpeter et al., 1984). Therefore, dystrophin is unlikely to anchor AChRs directly. Rather, dystrophin may affect the overall architecture of the NMJ, which may affect AChR trapping sites. Dystrophin is associated with a large glycoprotein complex (DGC) involving many components linking the cytoskeleton to the extracellular basal lamina (for review, seeMatsumura and Campbell, 1994). Much of this DGC is disrupted inmdx animals (Ohlendieck and Campbell, 1991), possibly reducing the structural integrity in the NMJ. One indication of this may be that in mdx mice the complexity of the NMJ is greatly reduced and the folds are shallower and much less regular (Torres and Duchen, 1987). Although AChR density is reported to be relatively normal in mdx mice despite a lack of dystrophin (Lyons and Slater, 1991), no information is yet available on the fine structural distribution of the AChRs on such disrupted folds. If the steady-state AChR density is indeed unaffected in mdx animals as reported by Lyons and Slater (1991), the fast degradation rate of AChRs in innervated mdx muscles must be compensated for by an increased synthesis of AChRs. In fact, total protein turnover has been reported to be elevated in mdx muscles (Witkowski, 1986;MacLennan and Edwards, 1990; MacLennan et al., 1991; Kämper and Rodemann, 1992). Future studies on the distribution and insertion rates of AChRs on mdx muscles should help resolve this issue.

The lack of dystrophin and the reduction of dystrophin-related proteins (Ohlendieck and Campbell, 1991) may also weaken the mechanical stability of the postsynaptic membrane (Pasternak et al., 1995). Compared with controls, the deformation of the mdx myotube membrane is much more pronounced in response to hypo-osmotic treatment (Menke and Jockusch, 1991). The membrane of mdx muscles is also leakier to Ca2+, resulting in an elevation of intracellular free Ca2+ (Turner et al., 1988, 1993) and muscle fiber degeneration (Leonard and Salpeter, 1979), which is a marked feature of human Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Moser, 1984).

One must consider the possibility that the apparent fast degradation rate of AChRs in innervated mdx muscles may be attributable to nonspecific degeneration of muscle fibers or that it may reflect a combination of adult (Rs) and embryonic (Rr) receptors, because Rr may be synthesized in the regenerating fibers. mdx mouse muscles begin a major cycle of degeneration and regeneration that stabilizes in most muscles by 10 weeks of age (Settles et al., 1996). The mice we used were between 10 and 12 weeks of age, which is when the majority of muscle fibers is resistant to additional degradation (Karpati et al., 1988). Furthermore, even after 12 d in organ culture,mdx muscles were still healthy and fibrillating. Most importantly, if some Rr (t1/2 ∼1 d) were present, they would be mostly degraded by 3–4 d, and we would have seen two components in our degradation curves, as is seen for receptors inserted in denervated muscles (Shyng and Salpeter, 1990). This was not the case.

Because in mdx mice the elevation of cAMP and the activation of adenylate cyclase are still capable of stabilizing Rs, it is possible that the lack of Rs stabilization in innervatedmdx muscles is upstream, at the level of neural trophic factors. Although adenylate cyclase can be activated by forskolin, it may not respond to some relevant neurotrophic factors, just as it is insensitive to catecholamines and sodium fluorides (Witkowski, 1986). One such possible neurotrophic factor is calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a 37 amino acid peptide that elevates intracellular cAMP (Laufer and Changeux, 1987, 1989; Miles et al., 1989; Crook and Yabu, 1992). CGRP appears in dense-core vesicles coexisting with ACh vesicles, and its release from the nerve terminal is Ca2+-dependent (Caldero et al., 1992; Sala et al., 1995). Additional research is needed to determine whether inmdx muscles there are defects in the release of or response to CGRP or of another yet unidentified trophic factor.

The challenge is now to discern how the regulation of adult muscle AChR degradation is affected by the presence or absence of dystrophin.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants NS09315 and GM10422 from National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Thomas Podleski for helpful discussions, Rui Lin and Kristine Reeser for technical assistance, and Kathie Burdick for help in preparing this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Miriam M. Salpeter, Section of Neurobiology and Behavior, W101 Seeley G. Mudd Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853.

Dr. Xu’s present address: Neurobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreose JS, Xu R, Lømo T, Salpeter MM, Fumagalli G. Degradation of two AChR populations at rat neuromuscular junction: regulation in vivo by electrical stimulation. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3433–3438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03433.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apel ED, Merlie JP. Assembly of the postsynaptic apparatus. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:62–67. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apel ED, Roberds SL, Campbell KP, Merlie JP. Rapsyn may function as a link between the acetylcholine receptor and the agrin-binding dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex. Neuron. 1995;15:115–126. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avila OL, Drachman DB, Pestronk A. Neurotransmission regulates stability of acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 1989;9:2902–2906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-08-02902.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bevan S, Steinbach H. Denervation increases the degradation rate of acetylcholine receptors at end-plate in vivo and in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 1983;336:159–177. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bewick GS, Nicholson LVB, Young C, O’Donnell E, Slater CR. Different distribution of dystrophin and related proteins at nerve-muscle junctions. NeuroReport. 1992;3:857–860. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199210000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloch RJ, Morrow JS. An unusual β-spectrin associated with clustered acetylcholine receptors. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:481–493. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloch RJ, Pumplin DW. Molecular events in synapto-genesis: nerve-muscle adhesion and postsynaptic differentiation. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:C345–C364. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.3.C345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloch RJ, Resneck WG, O’Neill A, Strong J, Pumplin DW. Cytoplasmic components of acetylcholine receptor clusters of cultured rat myotubes: the 58 kDa protein. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:435–446. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burden SJ, Depalma RL, Gottesman GS. Crossing of proteins in acetylcholine receptor-rich membranes: association between the β-subunit and the 43 kd subsynaptic protein. Cell. 1983;35:687–692. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byers TJ, Kunkel LM, Watkins SC. The subcellular distribution of dystrophin in mouse skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:411–421. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.2.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caldero J, Casanovas A, Sorribas A, Esquerda JE. Calcitonin gene-related peptide in rat spinal cord motoneurons: subcellular distribution and changes induced by axotomy. Neuroscience. 1992;48:449–461. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90504-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crook RB, Yabu JM. Calcitonin gene-related peptide stimulates intracellular cAMP via a protein kinase C-controlled mechanism in human ocular ciliary epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;188:662–670. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickson G, Azad A, Morris GE, Simon H, Noursadeghi M, Walsh FS. Co-localization, molecular association of dystrophin with laminin at the surface of mouse and human myotubes. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:1223–1233. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ervasti JM, Campbell KP. Membrane organization of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Cell. 1991;66:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90035-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fambrough DM. Control of acetylcholine receptors in skeletal muscle. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:165–227. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fertuck HC, Salpeter MM. Localization of acetylcholine receptor by 125I-labeled α-bungarotoxin binding at mouse motor endplates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1376–1378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Froehner SC. The role of the postsynaptic cytoskeleton in acetylcholine receptor organization. Trends Neurosci. 1986;9:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Froehner SC, Murnane AA, Tobler M, Peng HB, Sealock R. A postsynaptic Mr 58,000 (58K) protein concentrated at acetylcholine receptor rich sites in Torpedo electroplaques and skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:1633–1646. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.6.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fumagalli G, Balbi S, Cangiano A, Lømo T. Regulation of turnover and number of acetylcholine receptors at neuromuscular junction. Neuron. 1990;4:563–569. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90114-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia L, Pinçon-Raymond M, Romey G, Changeux J-P, Lazdunski M, Rieger F. Induction of normal ultrastructure by CGRP treatment in dysgenic myotubes. FEBS Lett. 1990;263:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80725-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall ZW, Sanes JR (1993) Synaptic structure and development: the neuromuscular junction. Cell 72/Neuron 10 [Suppl]:99–121. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Hoffman EP, Brown RH, Kunkel LM. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987;51:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kämper A, Rodemann HP. Alteration of protein degradation and 2-D protein pattern in muscle cells of mdx and DMD origin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189:1484–1490. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90242-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karpati G, Carpenter S, Prescott S. Small-caliber skeletal muscle fibers do not suffer necrosis in mdx mouse dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11:795–803. doi: 10.1002/mus.880110802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koenig M, Hoffman EP, Bertelson CJ, Monaco AP, Feener C, Kunkel LM. Complete cloning of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene in normal and affected individuals. Cell. 1987;50:509–517. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laufer R, Changeux J-P. Calcitonin gene-related peptide elevates cyclic AMP levels in chick skeletal muscle: possible neurotrophic role for a coexisting neuronal messenger. EMBO J. 1987;6:901–906. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laufer R, Changeux J-P. Calcitonin gene-related peptide and cyclic AMP stimulate phosphoinositide turnover in skeletal muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2683–2689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lebart M-C, Casanova D, Benyamin Y. Actin interaction with purified dystrophin from electric organ of Torpedo marmorata: possible resemblance with filamin-actin interface. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1995;16:543–552. doi: 10.1007/BF00126438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonard JP, Salpeter MM. Agonist-induced myopathy at the neuromuscular junction is mediated by calcium. J Cell Biol. 1979;82:811–819. doi: 10.1083/jcb.82.3.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levitt TA, Salpeter MM. Denervated endplates have a dual population of junctional acetylcholine receptors. Nature. 1981;291:239–241. doi: 10.1038/291239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyons PR, Slater CR. Structure and function of the neuromuscular junction in young adult mdx mice. J Neurocytol. 1991;20:969–981. doi: 10.1007/BF01187915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacLennan PA, Edwards RHT. Protein turnover is elevated in muscle of mdx mice in vivo. Biochem J. 1990;268:795–797. doi: 10.1042/bj2680795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacLennan PA, McArdle A, Edwards RHT. Effects of calcium on protein turnover of incubated muscles from mdx mice. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:E594–E598. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.4.E594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsumura KM, Campbell KP. Dystrophin-glycoprotein complex: its role in the molecular pathogenesis of muscular dystrophies. Muscle Nerve. 1994;17:2–15. doi: 10.1002/mus.880170103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menke A, Jockusch H. Decreased osmotic stability of dystrophin-less muscle cells from the mdx mouse. Nature. 1991;349:69–71. doi: 10.1038/349069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miles K, Greengard P, Huganir RL. Calcitonin-gene related peptides regulates phosphorylation of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in rat myotubes. Neuron. 1989;2:1517–1524. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moser H. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: pathogenic aspects and genetic prevention. Hum Genet. 1984;66:17–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00275183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohlendieck K, Campbell KP. Dystrophin-associated proteins are greatly reduced in skeletal muscle from mdx mice. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1685–1694. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.6.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohlendieck K, Ervasti JM, Matsumura K, Kahl SD, Leveille CJ, Campbell KP. Dystrophin-related protein is localized to neuromuscular junction of adult skeletal muscle. Neuron. 1991;7:499–508. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90301-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Malley J, Rubin LL, Salpeter M. Two populations of AChR in rat myotubes have different degradation rates and responses to cAMP. Exp Cell Res. 1993;208:44–47. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Malley JP, Greenberg I, Salpeter MM. The production of long-term rat muscle cell cultures on a Matrigel substrate and the removal of fibroblast contamination by collagenase. Methods Cell Sci. 1996;18:19–655–661. [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Malley JP, Moore CT, Salpeter MM. Stabilization of AChRs by exogenous ATP and its reversal by cAMP and calcium. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:159–165. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pasternak C, Wong S, Elson EL. Mechanical function of dystrophin in muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:355–361. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sala C, Andreose JS, Fumagalli G, Lomo T. Calcitonin gene-related peptide: possible role in formation and maintenance of neuromuscular junctions. J Neurosci. 1995;15:520–528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00520.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salpeter MM. Development and neural control of the neuromuscular junction and of the junctional acetylcholine receptor. In: Salpeter MM, editor. The vertebrate neuromuscular junction. Alan R. Liss; New York: 1987. pp. 55–115. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salpeter MM, Loring RH. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in vertebrate muscle: properties, distribution, neural control. Prog Neurobiol. 1985;25:297–325. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(85)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salpeter MM, Smith CD, Matthews-Bellinger JA. Acetylcholine receptor at neuromuscular junctions by EM autoradiography using mask analysis and linear sources. J Electron Microsc Tech. 1984;1:63–81. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salpeter MM, Cooper DL, Levitt-Gilmour T. Degradation rates of acetylcholine receptors can be modified in the postjunctional plasma membrane of the vertebrate neuromuscular junction. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1399–1403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sealock R, Butler MH, Kramarcy NR, Gao K-X, Murnane AA, Douville K. Localization of dystrophin relative to acetylcholine receptor domains in electric tissue and adult and cultured skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:1133–1144. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Settles DL, Cihak RA, Erickson HP. Tenasin-C expression in dystrophin-related muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:147–154. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199602)19:2<147::AID-MUS4>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shyng S-L, Salpeter MM. Degradation rate of acetylcholine receptors inserted into denervated vertebrate neuromuscular junctions. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:647–651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shyng S-L, Salpeter MM. The effect of reinnervation on the degradation rate of junctional acetylcholine receptors synthesized in denervated skeletal muscles. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3905–3915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-12-03905.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shyng S-L, Xu R, Salpeter MM. Cyclic AMP stabilizes the degradation of original junctional acetylcholine receptors in denervated muscles. Neuron. 1991;6:469–475. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90254-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sicinski P, Geng Y, Ryder-Cook AS, Barnard EA, Darkinson MG, Barnard PJ. The molecular basis of muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse: a point mutation. Science. 1989;244:1578–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.2662404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Somerville LL, Wang K. Sarcomere matrix of striated muscle: in vivo phosphorylation of titin and nebulin in mouse diaphragm muscle. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;262:118–129. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stiles JR, Salpeter MM. Absence of nerve-dependent conversion of rapidly degrading to stable acetylcholine receptors at adult innervated endplates. Neuroscience. 1997;78:895–901. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00628-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Torres LFB, Duchen LW. The mutant mdx: inherited myopathy in the mouse-morphological studies of nerves, muscles and end-plates. Brain. 1987;110:269–299. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turner PR, Westwood T, Regen CM, Steinhardt RA. Increased protein degradation results from elevated free calcium levels found in muscle from mdx mice. Nature. 1988;335:735–738. doi: 10.1038/335735a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turner PR, Schultz R, Ganguly B, Steinhardt RA. Proteolysis results in altered leak channel kinetics and elevated free calcium in mdx muscle. J Membr Biol. 1993;133:243–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00232023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watkins SC, Hoffman EP, Slayter HS, Kunkel LM. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of dystrophin in myofibres. Nature. 1988;333:863–866. doi: 10.1038/333863a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wetzel DM, Salpeter MM. Fibrillation and accelerated AChR degradation in long-term muscle organ culture. Muscle Nerve. 1991;14:1003–1012. doi: 10.1002/mus.880141012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Witkowski JA. Tissue culture studies of muscle disorders: part 1. Techniques, cell growth, morphology, cell surface. Muscle Nerve. 1986;9:191–207. doi: 10.1002/mus.880090302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu R, Salpeter M. The degradation rate of Rs acetylcholine receptors on mouse diaphragms is regulated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Cell Physiol. 1995;165:30–39. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041650105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]