Summary

The proteasome mediates selective protein degradation and is dynamically regulated in response to proteotoxic challenges. SKN-1A/Nrf1, an ER-associated transcription factor that undegoes N-linked glycosylation, serves as a sensor of proteasome dysfunction and triggers compensatory upregulation of proteasome subunit genes. Here, we show that the PNG-1/NGLY1 peptide:N-glycanase edits the sequence of SKN-1A protein by converting particular N-glycosylated asparagine residues to aspartic acid. Genetically introducing aspartates at these N-glycosylation sites bypasses the requirement for PNG-1/NGLY1, showing that protein sequence editing rather than deglycosylation is key to SKN-1A function. This pathway is required to maintain sufficient proteasome expression and activity, and SKN-1A hyperactivation confers resistance to the proteotoxicity of human amyloid beta peptide. Deglycosylation-dependent protein sequence editing explains how ER-associated and cytosolic isoforms of SKN-1 perform distinct cytoprotective functions corresponding to those of mammalian Nrf1 and Nrf2. Thus, we uncover an unexpected mechanism by which N-linked glycosylation regulates protein function and proteostasis.

Keywords: SKN-1, SKN-1A, Nrf1, Nrf2, NFE2L1, NFE2L2, PNG-1, NGLY1, peptide:N-glycanase, PNGase, NGLY1 deficiency, neurodegenerative diseases, bortezomib, proteasome, proteostasis, protein sequence editing, deglycosylation, glycobiology, N-linked glycosylation, protein quality control

Graphical Abstract

In brief

Post-translational protein sequence editing dependent on deglycosylation of N-glycosylated asparagine residues regulates proteasome function in C. elegans

INTRODUCTION

The proteasome is a highly conserved multi-protein complex responsible for selective protein degradation in eukaryotic cells (Collins and Goldberg, 2017). A key function of the proteasome is the destruction of damaged and misfolded proteins. Deficits in proteasome function cause adult-onset neurodegenerative diseases and may be a general feature of decline in cellular and organismal function during aging (Pilla et al., 2017; Saez and Vilchez, 2014). Dissecting how cells maintain homeostasis during challenges to the proteasome may provide insights into how the system fails during aging and disease.

A particular member of the stress-responsive Nrf/NFE2 family of Cap ‘n’ Collar (CnC) basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors, Nrf1/NFE2L1 regulates proteasome subunit gene expression. Nrf1 is closely related to Nrf2/NFE2L2, and binds to the same DNA sequence motif, but performs distinct functions. Nrf1 mediates the compensatory upregulation of proteasome subunit genes during proteasome dysfunction, whereas Nrf2 regulates xenobiotic detoxification and oxidative stress responses (Ma, 2013; Ohtsuji et al., 2008; Radhakrishnan et al., 2010; Steffen et al., 2010). In C. elegans, both of these functions depend on a single Nrf orthologue, skn-1 (An and Blackwell, 2003; Li et al., 2011). C. elegans skn-1/Nrf generates three protein isoforms (SKN-1A, B and C) via differential splicing and transcription start site utilization. All three SKN-1 isoforms share an identical C-terminal CnC DNA binding domain but have different N-termini and expression patterns (reviewed in (Blackwell et al., 2015)). SKN-1A contains an N-terminal transmembrane domain (not found in either SKN-1B or SKN-1C) that causes it to localize to the ER (Glover-Cutter et al., 2013). SKN-1A is expressed in all tissues. SKN-1B is expressed in two sensory neurons, and SKN-1C is expressed only in the intestine (An and Blackwell, 2003; Bishop and Guarente, 2007). Oxidative stress triggers nuclear localization of SKN-1C, suggesting that this isoform may function analogously to Nrf2 (An and Blackwell, 2003).

A conserved mechanism controls the activity of SKN-1A in C. elegans and Nrf1 in mammalian cells to regulate proteasomal gene expression. SKN-1A/Nrf1 localizes to the ER where it undergoes N-linked glycosylation (Glover-Cutter et al., 2013; Radhakrishnan et al., 2014; Wang and Chan, 2006; Zhang et al., 2007). Normally, glycosylated SKN-1A/Nrf1 is rapidly degraded by the proteasome following its ERAD-dependent retrotranslocation to the cytoplasm. But if proteasome function is impaired, some of SKN-1A/Nrf1 escapes degradation, enters the nucleus, and increases the transcription of genes encoding proteasome subunits (Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016; Radhakrishnan et al., 2010; Sha and Goldberg, 2014; Steffen et al., 2010).

To regulate proteasome subunit genes, SKN-1A/Nrf1 undergoes proteolytic cleavage by the DDI-1/DDI2 aspartic protease, and N-linked glycans are removed by the peptide:N-glycanase (PNGase) PNG-1/NGLY1 (Koizumi et al., 2016; Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016; Radhakrishnan et al., 2014; Tomlin et al., 2017). Activation of SKN-1A/Nrf1 via these processing steps is essential for survival under conditions of impaired proteasome function in C. elegans or human cells (Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016; Radhakrishnan et al., 2010). The molecular mechanism by which cleavage and deglycosylation activates SKN-1A/Nrf1 is not known.

Here, we establish the molecular basis for SKN-1A activation by the PNG-1 PNGase and the DDI-1 aspartic protease. Activation requires the conversion of specific N-glycosylated asparagine residues within SKN-1A to aspartate. This conversion is carried out by PNG-1/NGLY1, which uses N-linked glycosylation as a mark to guide site-specific protein sequence editing of SKN-1A, revealing an unexpected mechanism by which removal of N-linked glycans regulates protein function. We show that a truncated (to mimic cleavage by the protease DDI-1) and deglycosylation-mimetic mutant SKN-1A hyperactivates the proteasome and enhances proteostasis. Conversely, inactivation of this pathway reduces basal proteasome expression and activity. These data reveal the molecular mechanism of proteasome homeostasis and pave the way for targeted modulation of proteasome activity.

RESULTS

Proteolytic cleavage and glycosylation are required for SKN-1A function.

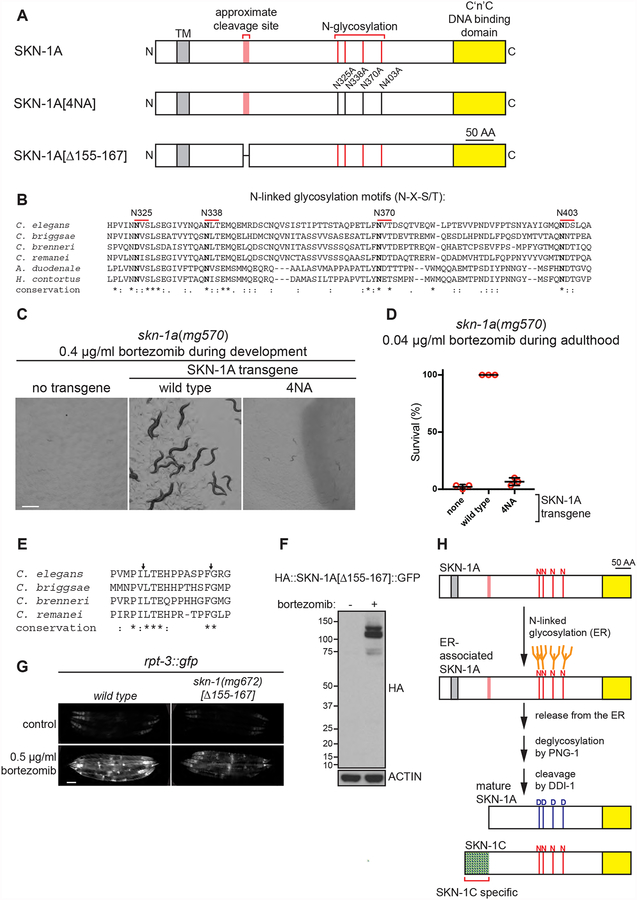

Post-translational modifications acquired within the ER are essential for SKN-1A function (Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016). Protein N-linked glycosylation occurs specifically within the ER and regulation of the proteasome by SKN-1A requires the peptide:N-glycanase (PNGase) PNG-1/NGLY1, suggesting that N-linked glycosylation status regulates SKN-1A/Nrf1 function. SKN-1A contains 4 conserved N-linked glycosylation motifs (N-X-S/T) that are likely to undergo N-linked glycosylation: N325, N338, N370, and N403 (Fig. 1a; these motifs are present in both SKN-1A and SKN-1C but only SKN-1A is ER-associated). Phylogenetic comparison reveals a strong conservation of these sequence motifs over a wide range of nematodes, including parasitic nematodes very distant from C. elegans (Fig. 1b). To test whether glycosylation at these sites affects the function of SKN-1A, we generated a mutant SKN-1A derivative with all four of these residues replaced by alanine (N325A, N338A, N370A, N403A; hereafter ‘4NA’; Fig. 1a). In contrast to control transgenes with intact N-glycosylation sites, transgenes ubiquitously expressing SKN-1A[4NA] do not rescue the bortezomib sensitivity of the skn-1a(mg570) mutant (Fig. 1c, d). This suggests that glycosylation at one or more of these sites is required for SKN-1A function. Given that a deglycosylating enzyme is required for SKN-1A activation, it is perhaps surprising that disrupting glycosylation inactivates SKN-1A. Glycosylation could be required for trafficking of SKN-1A from the ER, as glycosylation is important for recognition of many ERAD substrates (Brodsky, 2012). SKN-1A[4NA] accumulates in nuclei during bortezomib challenge similarly to wild type SKN-1A (Fig. S1). The stability and post-translational processing of wild type SKN-1A and SKN-1A[4NA] are both similarly dependent on ERAD and proteasome function (Fig. S1). These results indicate that N-linked glycosylation at these sites is not required for ERAD-dependent trafficking from the ER, proteasomal degradation, or proteolytic cleavage of SKN-1A. Instead, these data indicate that SKN-1A function requires N-linked glycosylation and subsequent deglycosylation for some other reason.

Figure 1. Identification N-linked glycosylation and proteolytic processing sites required for SKN-1A function.

(a) Model of the full length SKN-1A protein showing putative sites of proteolytic cleavage and N-glycosylation, showing mutant forms of SKN-1A analyzed in this figure. (b) Alignment showing conservation of four putative glycosylation sites of SKN-1A between C. elegans and related nematodes. (c) Images showing development of animals exposed to bortezomib. 5–10 L4 animals were shifted to bortezomib-supplemented plates and the growth of their progeny imaged after 5 days. The growth defect of skn-1a(mg570) mutants is not rescued by a transgene expressing SKN-1A lacking the four conserved glycosylation sites. Scale bar 500 μm. (d) Survival of adult animals exposed to 0.04 μg/ml bortezomib. Late L4 stage animals were shifted to plates containing 0.04 μg/ml bortezomib and checked for survival after 4 days. The survival defect of skn-1(mg570) mutants is not rescued by a transgene expressing SKN-1A lacking the four conserved glycosylation sites. Results of n=3 replicate experiments are shown; error bars show mean +/− standard deviation. Survival of 30 animals was tested for each replicate. (e) Alignment showing conservation of amino acids 152–169 of SKN-1A between C. elegans and related nematodes. Arrows indicate conserved pairs of hydrophobic residues (matching the substrate preference of retroviral aspartic proteases). (f) Western blot showing the expression and processing of dually tagged SKN-1A bearing an in-frame deletion of amino acids 155–167. Animals were treated with bortezomib (5 μg/ml) or vehicle control. (g) Fluorescence micrographs showing expression of rpt-3p::gfp in the wild type and in skn-1(mg672) mutant animals. Induction of rpt-3p::gfp following bortezomib exposure is impaired in skn-1(mg672) mutants. skn-1(mg672) is a CRISPR-induced in-frame deletion of amino acids 155–167 of SKN-1A. Scale bar 100 μm. (h) Model for SKN-1A processing. Following release of N-glycosylated SKN-1A from the ER, SKN-1A Is deglycosylated by PNG-1 and cleaved by DDI-1. Red lines indicate N-glycosylated asparagine residues predicted to undergo conversion to aspartate during deglycosylation by PNG-1. SKN-1C is shown for comparison.

After release from the ER, SKN-1A/Nrf1 undergoes proteolytic cleavage by the DDI-1/DDI2 protease (Koizumi et al., 2016; Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016). The DDI-1-dependent proteolytic cleavage of doubly tagged HA::SKN-1A::GFP releases a ~20 kD peptide containing the N-terminal HA epitope tag (Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016). A product of this size indicates that cleavage occurs approximately 160 residues from the N-terminus of SKN-1A (Fig. 1a). This region of SKN-1A bears no obvious sequence similarity to the DDI2-dependent proteolytic cleavage site of human Nrf1 (Radhakrishnan et al., 2014). The protease domain of DDI-1/DDI2 is related to that of the retroviral aspartic proteases, which often cleave their substrates between pairs of non-polar residues (Sirkis et al., 2006; Tözsér, 2010). There are two such pairs of residues in SKN-1A that are close to the apparent cleavage site, and that are conserved in other closely related nematodes (Fig. 1e). We tested whether this sequence is required for cleavage of SKN-1A with a construct that drives ubiquitous expression of dually tagged SKN-1A with an in-frame deletion of amino acids 155–167 (155PILTEHPPASPFG167), which we term HA::SKN-1A[Δ155–167]::GFP (Fig. 1a). HA::SKN-1A[Δ155–167]::GFP expression is not detectable under control conditions, but the protein is stabilized by bortezomib treatment, indicating that the in-frame deletion does not affect the ERAD-dependent degradation of SKN-1A by the proteasome (Fig. 1f). In animals exposed to bortezomib, HA::SKN-1A[Δ155–167]::GFP does not undergo proteolytic cleavage and accumulates as full length protein, similarly to the wild type SKN-1A protein in animals lacking the DDI-1 protease (Fig. 1f, S1). We used CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to introduce the same in-frame deletion of amino acids 155–167 of SKN-1A into the endogenous skn-1 locus. These skn-1(mg672) mutants show defective activation of rpt-3p::gfp following bortezomib treatment, consistent with our previous finding that proteolytic cleavage of SKN-1A is required for activation of the proteasome reporter (Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016) (Fig. 1g). Thus, proteolytic cleavage of SKN-1A by DDI-1 occurs within or immediately adjacent to amino acids 155–167. Activated SKN-1A is therefore an N-terminal truncated protein of approximately 460 amino acids. We conclude that the activated form of SKN-1A is a truncated and deglycosylated protein (Fig. 1h). SKN-C does not undergo DDI-1-mediated truncation because it lacks the SKN-1A-specific N-terminal transmembrane domain, which is essential for cleavage by DDI-1 (Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016). The activated form of SKN-1A is smaller than SKN-1C, which is a 533 AA protein (this includes all 460 amino acids within activated SKN-1A, plus an additional ~70 AA at the N-terminus; see Fig. 1h).

Conversion of glycosylated asparagine residues to aspartate is required for SKN-1A function.

PNGase catalyzes a deamidation reaction that both releases the glycan moiety and concomitantly converts N-glycosylated asparagine residues to aspartate, thereby editing the primary amino acid sequence of the substrate peptide (Suzuki et al., 1994). As a result, removal of N-glycans by PNG-1 post-translationally edits particular asparagine residues to aspartates in the primary protein sequence of SKN-1A (Fig. 1h). We sought to dissect how truncation and deglycosylation contributes to SKN-1A function by testing the ability of a panel of truncated and/or sequence-modified SKN-1 proteins to rescue skn-1a(mg570). We compared transgenes expressing full length SKN-1A, SKN-1C (the shorter non-ER associated SKN-1 isoform), and an N-terminally truncated protein that mimics the product of DDI-1-dependent proteolytic cleavage of SKN-1A (which we term SKN-1A[cut]; see Fig. 2a). We generated transgenes that express each protein with wild type sequence as well as derivatives containing point mutations that substitute aspartate for asparagine at the four SKN-1A glycosylation sites (N325D, N338D, N370D, N403D numbered relative to SKN-1A; hereafter ‘4ND’) to mimic the protein sequence editing that would result from deglycosylation of these N-glycosylated asparagine residues by PNG-1 (termed SKN-1A[4ND], SKN-1C[4ND] and SKN-1A[cut, 4ND]; see Fig. 2a). All transgenes used for this analysis are single copy insertions that drive expression from the rpl-28 promoter, which is expressed constitutively in all tissues. The transgenes encode the indicated version of SKN-1 fused to an N-terminal HA tag and a C-terminal GFP tag, and we used the GFP tag to confirm that each form of SKN-1 is expressed at approximately similar levels and is nuclear-localized (Fig S2).

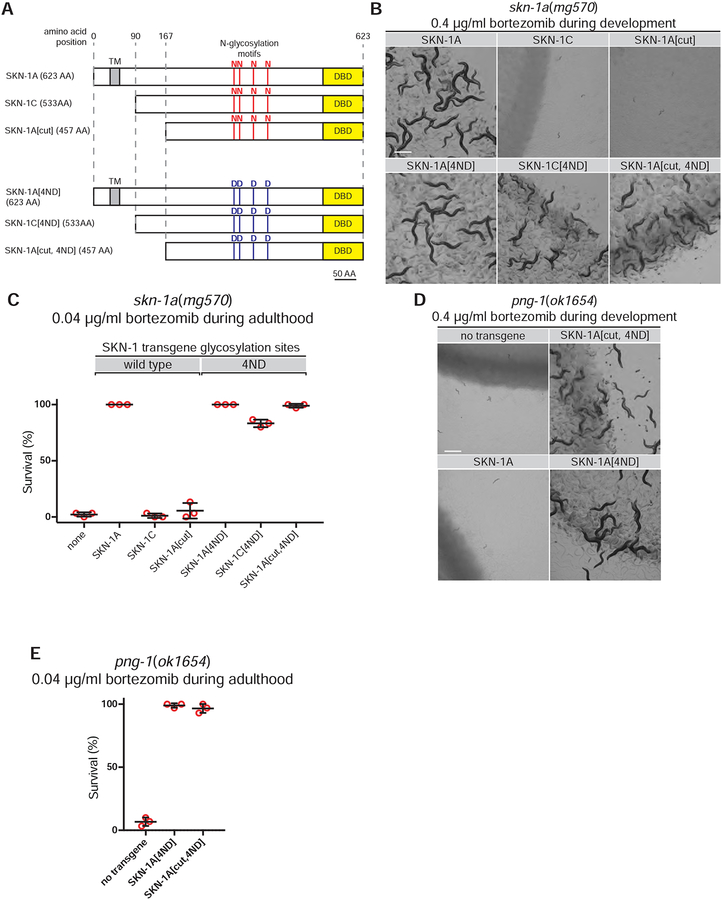

Figure 2. Truncation and conversion of glycosylated asparagine residues to aspartate are required for SKN-1A function.

(a) SKN-1A, SKN-1C and the predicted SKN-1A cleavage product. These proteins differ at their N-termini but are otherwise identical in sequence. These proteins, with addition of an N-terminal HA tag and C-terminal GFP tag, are expressed (under control of the ubiquitously active rpl-28 promoter) from the transgenes analyzed in this figure. All four asparagine residues at N-linked glycosylation sites are substituted to aspartate in 4ND constructs. Amino acid positions indicated are relative to full-length SKN-1A (DBD indicates DNA binding domain, TM indicates transmembrane domain). (b) Images showing that development of animals exposed to bortezomib requires sequence editing of SKN-1A. 5–10 L4 animals were shifted to bortezomib-supplemented plates and the growth of their progeny imaged after 5 days. The bortezomib sensitivity of skn-1a(mg570) mutants is rescued by a subset of SKN-1 expressing transgenes, in a manner dependent on length and sequence at glycosylation sites. (c) Survival of adult animals exposed to bortezomib depends on length and sequence editing of SKN-1A. Late L4 stage animals were shifted to plates containing bortezomib-supplemented plates and checked for survival after 4 days. Results of n=3 replicate experiments are shown; error bars show mean +/− standard deviation. Survival of 30 animals was tested for each replicate. (d, e) Sequence edited SKN-1A rescues the bortezomib sensitivity of png-1 mutant animals. Animals were exposed to bortezomib during development or adulthood as described in (b) and (c). All scale bars 500 μm.

We tested the ability of each modified form of SKN-1 to rescue the developmental arrest and reduced adult survival of skn-1a(mg570) mutant animals during proteasome inhibition by bortezomib (Fig. 2b, c). Unlike full length SKN-1A, transgenes driving ubiquitous expression of SKN-1C or SKN-1A[cut] do not rescue the bortezomib hypersensitivity of skn-1a mutants, suggesting that these truncated forms of SKN-1 are not competent to up-regulate proteasome genes in response to a proteasome defect. This result rules out the possibility that SKN-1C is insufficient for responses to proteasome dysfunction because its expression pattern is more restricted than that of SKN-1A, as SKN-1C expression in all tissues does not provide any improvement in resistance to bortezomib. This result also indicates that the truncation of SKN-1A by the DDI-1 aspartic protease alone does not explain its ability to regulate proteasome subunit genes.

Expression of SKN-1A[4ND] rescues the bortezomib sensitivity defect of skn-1a mutant animals, indicating that introduction of N to D substitutions at locations that are N-glycosylated in the ER does not disrupt the function of full length SKN-1A, even though substitution of these same residues to alanine is disruptive (Fig. 2b, c). The 4ND sequence-modified truncated construct (ie SKN-1A[cut, 4ND]), designed to resemble to product of truncation by DDI-1 and deglycosylation by PNG-1, also completely rescues the bortezomib sensitivity of skn-1a mutants both during development and adulthood. SKN-1C[4ND] also rescues the developmental arrest caused by bortezomib (but not completely, as many animals burst upon reaching adulthood), and the SKN-1C[4ND] rescued animals show dramatically improved survival when exposed to bortezomib during adulthood (Fig. 2b, c, Fig. S3). These results demonstrate that proteasome homeostasis is completely rescued by SKN-1A[cut, 4ND], and partially restored by SKN-1C[4ND], but not by equivalent proteins with unaltered glycosylation site sequences. This indicates that both proteolytic cleavage by the DDI-1 protease and PNG-1 mediated asparagine to aspartate sequence edits are required for SKN-1A function. These data support the model that the activated form of SKN-1A is a truncated protein that contains particular N to D amino acid edits introduced by PNG-1-mediated deglycosylation. Sequence alteration is particularly critical, as introducing four N to D substitutions is sufficient for SKN-1C, which is not normally sufficient for resistance to proteasome inhibitors, to function almost equivalently to ER-localized SKN-1A/Nrf1.

If PNGase regulates SKN-1A via protein sequence editing, then by directly expressing the edited protein, the SKN-1A[4ND] and SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] transgenes should not only rescue skn-1a mutant animals, but should also bypass the requirement for PNGase in resistance to bortezomib. We used this assay to test whether the role of PNG-1/NGLY1 in regulation of the proteasome reflects a defect in post-translational sequence editing of the SKN-1A protein. png-1 mutants are highly sensitive to bortezomib, and are unable to either develop, or survive as adults in the presence of low doses of the drug. The SKN-1A[4ND] and SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] transgenes both completely rescue these defects (Fig. 2d, e). In contrast, the bortezomib sensitivity of the png-1 mutant is not rescued by transgenes that over-express full length SKN-1A, which requires PNG-1 for its activation (Fig. 2d) (Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016). Thus, failure to generate the sequence-edited form of SKN-1A explains the defective proteasome homeostasis of png-1 mutant animals.

Conversion of glycosylated asparagine residues of SKN-1A to aspartate is required for activation of proteasome subunit gene expression.

We used reporter genes to assess how truncation and sequence editing of SKN-1A affects regulation of its transcriptional targets. SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] strongly activates the rpt-3p::gfp proteasome subunit reporter gene in the absence of any proteotoxic stress (Fig. 3a). Over-expression of SKN-1A and SKN-1A[4ND] modestly increases expression of the reporter gene, and the other modified forms of SKN-1 have little or no effect on rpt-3p::gfp expression. These data suggest that both truncation and PNG-1-dependent sequence editing of SKN-1A influence proteasome subunit gene regulation. gst-4 encodes a glutathione S-transferase implicated in oxidative stress responses and xenobiotic detoxification. gst-4p::gfp is induced in a skn-1-dependent manner in response to a number of stimuli including proteasome inhibition and oxidative stress (Paek et al., 2012; Pang et al., 2014; Tang and Choe, 2015a). The length and sequence of SKN-1 also affects its ability to regulate gst-4p::gfp, but in a manner distinct from rpt-3p::gfp (Fig. 3b). Expression of truncated SKN-1A[cut] causes strong upregulation of gst-4p::gfp, reminiscent of the induction caused by loss of WDR-23, a negative regulator of the skn-1-dependent oxidative stress response (Choe et al., 2009). Analysis of skn-1 gain-of-function alleles suggests that inhibition by WDR-23 requires an N-terminal region of SKN-1C (Fukushige et al., 2017; Tang and Choe, 2015a). The SKN-1A[cut] protein, which lacks this N-terminal domain, likely drives constitutive activation of gst-4p::gfp by escaping inhibition by WDR-23. Activation of gst-4p::gfp by SKN-1A[cut] and SKN-1C shows that failure to rescue skn-1a(mg570) does not reflect the inability of these proteins to regulate all SKN-1 target genes. Rather, these proteins fail to regulate specific targets, in particular the proteasome subunit genes, that are critical for the response to proteasome impairment.

Figure 3. Truncation and conversion of glycosylated asparagine residues to aspartate are required for regulation of proteasome subunits by SKN-1A.

Fluorescence micrographs showing the effect of various SKN-1 transgenes on basal expression levels of (a) rpt-3p::gfp and (b) gst-4p::gfp. (c) Fluorescence micrographs showing that rpt-3p::gfp expression in animals expressing SKN-1C[4ND] depends on WDR-23. (d) Fluorescence micrographs showing that SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] causes constitutive induction of rpt-3p::gfp independent of bortezomib exposure. Animals were treated for 24 hours with DMSO control or 0.5 μg/ml bortezomib. (a-d) Scale bar 100 μm. (e) Model illustrating the effect of truncation and asparagine to aspartate sequence edits at N-glycosylation motifs on regulation of SKN-1 target genes. Truncation determines regulation by WDR-23, whereas sequence edits determine target specificity, possibly via recruiting cofactors required for regulation of proteasome subunit genes. (f) Images showing SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] allows development of animals exposed to very high levels of bortezomib. 15 L4 stage animals were shifted to plates containing 10 μg/ml bortezomib and development of their progeny was imaged after 5 days. Scale bar 500 μm. (g) SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] increases bortezomib resistance. Late L4 stage animals were shifted to plates containing 10–40 μg/ml bortezomib, and their survival was monitored after 4 days. Results of n=3 replicate experiments are shown; error bars show mean +/− standard deviation. Survival of 30 animals was tested for each replicate. **** P<0.0001; ** P<0.001; ns P>0.05 (two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test) indicates P-value compared to wild type control at the same bortezomib concentration. (h) SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] mitigates pathology in a C. elegans Alzheimer’s disease model. Synchronized populations of animals raised at 25°C were scored daily for paralysis beginning at the young adult stage (48 hours). Results of n=3 replicate experiments are shown; error bars show mean +/− standard deviation. Paralysis of 100–200 animals was tested for each replicate. Paralysis of control animals was not scored at 120 hours as many animals had already died. **** P<0.0001 (two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test).

Inhibition of SKN-1C[4ND] by WDR-23 may impede its ability to regulate proteasome subunits, explaining its partial rescue of skn-1a(mg570). In animals over-expressing SKN-1C or SKN-1A[cut], depletion of WDR-23 does not cause increased expression of rpt-3p::gfp. However, depletion of WDR-23 from animals over-expressing SKN-1C[4ND] causes strong activation of the proteasome subunit reporter (Fig. 3c). Taken together with the hyperactivation of gst-4p::gfp by SKN-1A[cut], these data confirm that negative regulation of SKN-1C depends on recognition of its N-terminus by WDR-23. We conclude that SKN-1C[4ND] is inhibited by WDR-23, and so does not constitutively activate proteasome subunit gene expression, or fully rescue bortezomib resistance of skn-1a mutants.

SKN-1A (and Nrf1) is targeted for proteasomal degradation by ERAD, creating a feedback loop that limits proteasome gene expression under non-stressed conditions (Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016; Steffen et al., 2010). Because SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] does not contain the N-terminal ER-targeting domain, it should escape this negative feedback loop. Wild-type animals treated with bortezomib show strong upregulation of rpt-3p::gfp. In contrast, animals carrying the SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] transgene show constitutive activation of rpt-3p::gfp in the absence of bortezomib, and levels of rpt-3p::gfp are not further increased upon bortezomib exposure (Fig. 3d). This pattern is unchanged in skn-1a, png-1 and ddi-1 mutant backgrounds, indicating that it results from the constitutive activity of SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] (Fig. S4). This is distinct from full length SKN-1A[4ND], which confers bortezomib-inducible expression of rpt-3p::gfp in a manner that does not require PNG-1 but is impaired in ddi-1 mutants (Fig S4). We conclude that SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] (unlike full length SKN-1A) does not act as a sensor of proteasome activity and instead constitutively activates proteasome subunit gene expression.

We generated a SKN-1A construct that is truncated to mimic DDI-1-dependent cleavage in which the four glycosylation site asparagine residues are substituted with alanine (SKN-1A[cut, 4NA]). Unlike SKN-1A[cut, 4ND], this construct does not rescue the bortezomib sensitivity of skn-1a(mg570) mutants, and does not cause increased expression of rpt-3p::gfp (Fig. S5). It does, however, drive strong expression of gst-4p::gfp, indicating that the asparagine to alanine substitutions do not disrupt the transcriptional activation function of the truncated protein at oxidative stress genes (Fig. S5). Thus, SKN-1A[cut, 4NA] functions similarly to SKN-1A[cut] with unaltered glycosylation sites. These data indicate that conversion of N-glycosylated asparagine residues specifically to aspartate is required for regulation of proteasome subunit genes by SKN-1, whereas regulation of other SKN-1 targets such as the oxidative stress gene gst-4 does not depend on sequence editing. This suggests that the four N to D substitutions do not modulate regulation of SKN-1 via factors that can only recognize the unaltered version of this part of the protein. Instead, it is likely that the conversion to aspartate introduces a new function to this domain, for example creating a binding site for cofactors that are critical for transcriptional regulation of proteasome subunit genes (Fig. 3e).

To identify the sequence editing events critical to proteasome subunit gene regulation, we tested activation of rpt-3p::gfp in animals expressing truncated SKN-1A containing different combinations of N to D substitutions (Fig S5). Among constructs containing a single N to D substitution, only N338D confers strong activation of rpt-3p::gfp, and N370D alone causes a slight increase in reporter expression. Of the six possible combinations of two N to D substitutions, the three combinations that include N338D cause the strongest activation of rpt-3p::gfp. All combinations of 3 N to D alterations show strong activation of the proteasome subunit reporter. Thus, although N338D is sufficient, it is not required for proteasome gene regulation. These results indicate that none of the four sequence editing events are essential, and each position can contribute to proteasome regulation. However, the contribution of each of the four residues is not equivalent and editing at N338 appears to play the most important role.

In sum, these data clarify the mechanism through which ER-trafficking, cleavage by DDI-1, and sequence editing by PNG-1 differentiate SKN-1A from SKN-1C (Fig. 1h, Fig. 3e). Due to its N-terminal transmembrane domain, SKN-1A is N-glycosylated before being released from the ER and targeted for proteasomal degradation by ERAD (which limits SKN-1A levels when the proteasome is functioning efficiently). Cleavage of SKN-1A by DDI-1 prevents inhibition by WDR-23, and deglycosylation-dependent sequence editing of SKN-1A by PNG-1 alters target specificity to allow regulation of proteasome subunit genes. SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] both uncouples SKN-1A from negative regulation by ERAD and mimics the ER-dependent activation of SKN-1A to constitutively activate the proteasome. Importantly, SKN-1C is not ER-associated and so is not subject to either cleavage or to sequential N-linked glycosylation and deglycosylation. As a result, SKN-1C regulates an oxidative stress response - a response that is inhibited by WDR-23, but is unable to regulate proteasome subunit gene expression.

Constitutively active SKN-1A enhances proteostasis.

Consistent with constitutive activation of a cytoprotective pathway, SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] animals are remarkably resistant to proteotoxic insults. Animals carrying the SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] transgene are able to develop and survive as adults in the presence of high concentrations of bortezomib that are toxic to wild type animals (Fig 3f, g). This resistance to proteasome inhibition is not simply due to expression of SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] from a strong promoter, because over-expression of full length SKN-1A from the same rpl-28 promoter only causes a subtle increase in bortezomib resistance (Fig 3g). Given that SKN-1A normally acts during proteasome inhibition to promote compensatory synthesis of new proteasomes, these data suggest that SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] drives a constitutive increase in proteasome levels that is sufficient to compensate for very high doses of proteasome inhibitor. To test whether hyperactivation of the proteasome is protective against protein aggregation insults, we analyzed animals expressing the human amyloid beta peptide (Aβ) in muscle (unc-54p::Aβ). These animals show progressive adult-onset paralysis due to Aβ toxicity (Link, 2006). The SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] transgene causes a marked delay in the age-dependent paralysis of unc-54p::Aβ transgenic animals despite an unchanged level of Aβ mRNA expression (Fig 3h, S5). These data indicate that activation of the proteasome by truncated and sequence-edited SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] enhances proteostasis.

SKN-1A and SKN-1C are distinct transcriptional regulators.

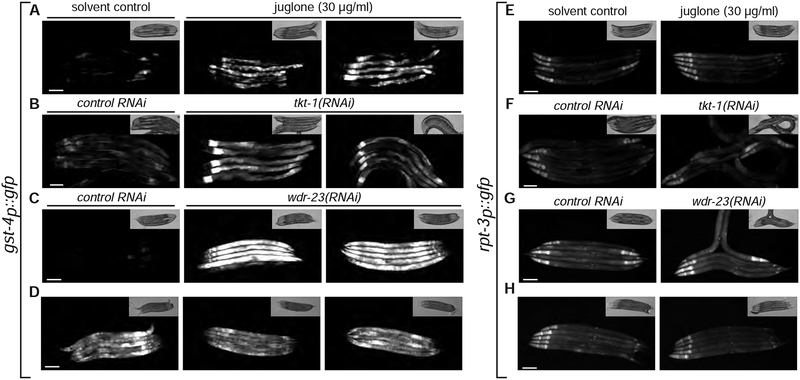

Our analysis of transgenes expressing different forms of SKN-1 suggest that SKN-1A and SKN-1C mediate distinct transcriptional programs. To confirm this, we examined control of gene expression by endogenous SKN-1A/C. SKN-1 responds to oxidative stress and starvation, but whether these responses involve SKN-1A has not been tested (An and Blackwell, 2003; Paek et al., 2012). To test the role of SKN-1A in this context, we examined regulation of gst-4p::gfp in skn-1a(mg570) mutant animals (the mg570 lesion disrupts SKN-1A but does not affect SKN-1C). Upregulation of gst-4p::gfp during oxidative stress caused by juglone or depletion of transketolase (TKT-1) is not affected in skn-1a(mg570) mutant animals (Fig. 4a, b). wdr-23 negatively regulates skn-1-dependent oxidative stress responses (Choe et al., 2009; Fukushige et al., 2017; Tang and Choe, 2015a), but activation of gst-4p::gfp by wdr-23(RNAi) is unaltered in skn-1a(mg570) mutants (Fig. 4c). These data indicate that the transcriptional response to oxidative stress does not require SKN-1A. The skn-1(zu67) allele, which affects both SKN-1A and SKN-C (Bowerman et al., 1992), abrogates gst-4 upregulation in wdr-23 mutants and renders animals hypersensitive to oxidative stress (An and Blackwell, 2003; Staab et al., 2013). We therefore conclude that oxidative stress responses are mediated by SKN-1C, not SKN-1A.

Figure 4. SKN-1A and SKN-1C mediate distinct transcriptional responses.

(a-d) Fluorescence images showing expression of gst-4p::gfp. Induction of gst-4p::gfp by exposure to juglone, tkt-1(RNAi) or wdr-23(RNAi) does not require SKN-1A. Hyperactivation of gst-4p::gfp in skn-1(lax188) mutants does not require SKN-1A or PNG-1. SKN-1A is disrupted in skn-1(lax188mg673) animals by a premature stop codon in a skn-1a-specific exon. (e-h) Fluorescence images showing expression of rpt-3p::gfp. Exposure to juglone, tkt-1(RNAi) or wdr-23(RNAi) does not induce rpt-3p::gfp. skn-1(lax188) mutants do not hyperactivate rpt-3p::gfp. All scale bars 100 μm.

The skn-1(lax188) gain-of-function allele, which causes an E to K amino acid substitution in both SKN-1A (E237K) and SKN-1C (E147K), activates gst-4 expression (Paek et al., 2012). lax188 could hyperactivate either or both of SKN-1A and SKN-1C. We used CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce a SKN-1A-specific premature termination codon to skn-1(lax188) animals, thus generating animals that express E147K mutant SKN-1C, but lack SKN-1A. This does not alter the activation of gst-4p::gfp compared to the parental skn-1(lax188) strain (Fig. 4d). Although loss of PNG-1 inactivates SKN-1A, gst-4p::gfp levels are also unaffected in png-1(ok1654); skn-1(lax188) double mutants (Fig. 4d). We conclude that SKN-1C, but not SKN-1A, mediates the starvation/detoxification response activated in skn-1(lax188) animals.

We used the rpt-3p::gfp proteasome subunit transcriptional reporter to examine regulation of proteasome subunits under conditions that lead to increased gst-4 expression. Expression of rpt-3p::gfp is not induced by any of the conditions that increase expression of gst-4p::gfp via SKN-1C (Fig. 4e–h). Transcriptome profiling of wdr-23 and skn-1(lax188) mutants revealed upregulation of many SKN-1 target genes but no alteration in proteasome subunit mRNA levels (Paek et al., 2012; Staab et al., 2013). These results indicate that although oxidative stress and the lax188 mutation activate SKN-1C, neither condition activates SKN-1A and downstream proteasome subunit genes. Secondly, SKN-1C regulates a set of target genes that includes gst-4 but excludes proteasome subunit genes.

Pharmacological proteasome inhibition by bortezomib causes SKN-1A and PNG-1-dependent upregulation of both gst-4 and proteasome subunits (Fig. S6). These results are consistent with the specific requirement for SKN-1A in regulation of proteasome subunits and with the distinct genetic requirements for gst-4 activation following oxidative stress and proteasome inhibition (Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016; Wu et al., 2017). Taken together, these data support a model in which different SKN-1 isoforms respond to different stimuli and regulate distinct but overlapping sets of target genes (Fig. S6). This distinction is consistent with the effects of post-translational truncation and sequence editing on the function of SKN-1A revealed by our structure-function analysis.

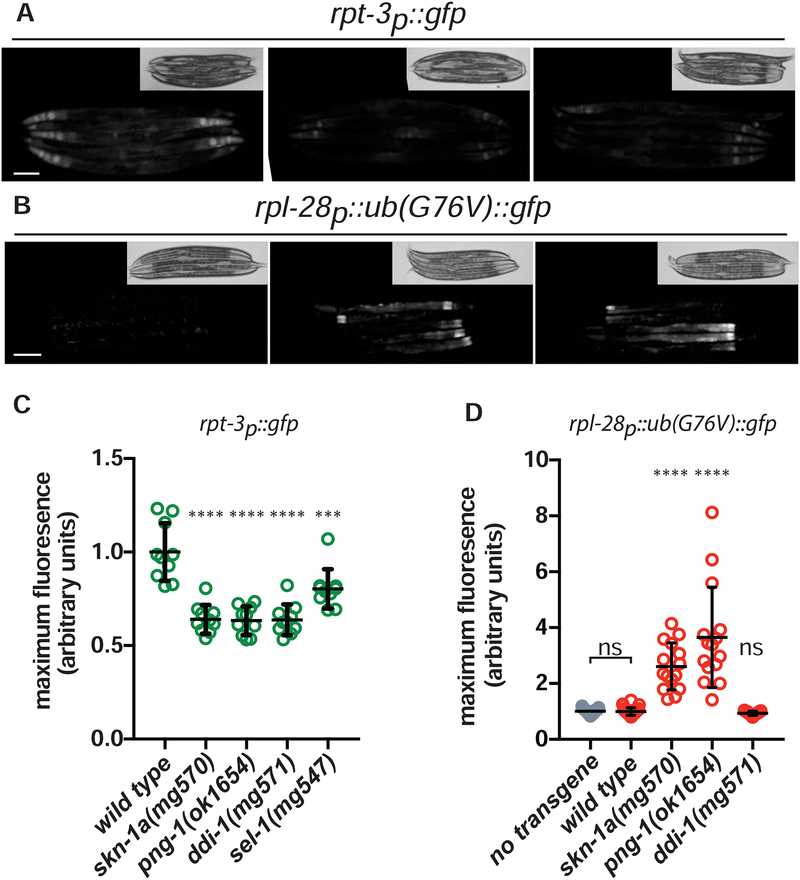

The skn-1 gene has also been linked to regulation of proteasome levels and activity in situations that do not involve proteasome dysfunction (Li et al., 2011; Segref et al., 2014; Steinbaugh et al., 2015), but whether this depends on SKN-1A or other isoforms of SKN-1 is not known. We therefore tested whether PNG-1 and SKN-1A affect proteasome gene expression and function in the absence of exogenous proteasome insults. Under standard culture conditions, expression of rpt-3p::gfp is reduced in skn-1a(mg570) mutants (Fig. 5a). rpt-3p::gfp expression is also reduced in png-1(ok1654), ddi-1(mg571), or sel-1(mg547) mutants defective in ER-trafficking and post-translational processing of SKN-1A (Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016) (Fig. 5a, c). To test whether SKN-1A affects basal levels of proteasome activity, we assayed protein degradation using a UB(G76V)::GFP fusion protein, which is subject to rapid degradation by the proteasome (Johnson et al., 1995; Segref et al., 2011). We generated a transgene that drives constitutive expression of this proteasome activity reporter under the control of a ribosome subunit promoter (rpl-28p::ub(G76V)::gfp). UB(G76V)::GFP is not detectable in wild type, but is stabilized in skn-1a(mg570) and png-1(ok1654) mutants, confirming that sequence-edited SKN-1A supports basal proteasome activity (Fig 5b, d). The defect in proteasome function in skn-1a and png-1 mutants occurs primarily in intestinal cells, even though this tissue also expresses SKN-1C (An and Blackwell, 2003). Interestingly, we did not observe such a defect in ddi-1(mg571) animals, indicating that while PNGase-dependent sequence editing is essential, cleavage of SKN-1A following its release from the ER is dispensable for this aspect of SKN-1A function (Fig 5d). This is consistent with our previous observation that png-1 and skn-1a mutations increase bortezomib sensitivity more dramatically than loss of DDI-1 (Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016). These data suggest that PNG-1-dependent activation of SKN-1A may also ensure proteasome expression in the absence of acute insults to the proteasome.

Figure 5. SKN-1A and PNG-1 control basal proteasome expression and activity.

(a) Fluorescence images showing reduced basal rpt-3p::gfp expression in skn-1a(mg570) and png-1(ok1654) mutant animals. (b) Florescence images showing stabilization of ub(G76V)::GFP in skn-1a(mg570) and png-1(ok1654) mutant animals. (c) Quantification of basal rpt-3p::gfp expression. n=10 day 1 adults. Error bars show mean +/− standard deviation. (d) Quantification of basal ub(G76V)::GFP levels. n=15 L4s. Error bars show mean +/− standard deviation. **** P<0.0001; *** P<0.001; ns P> 0.05 indicates P-value compared to wild type control (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Scale bars 100 μm.

DISCUSSION

The mechanism of SKN-1A activation.

Regulation of proteasome subunit genes and resistance to bortezomib depends on the editing of the protein sequence of SKN-1A at essential N-linked glycosylation motifs. We identified by sequence comparisons and mutational analyses four conserved glycosylation motifs at N325, N338, N370, and N403. Our mutational analysis showed that an alanine substitution renders full length SKN-1A non-functional, but that aspartic acid substitutions at these positions activates a pre-truncated SKN-1A even in the absence of the deglycosylation and deamidation enzyme PNG-1/NGLY1. These results genetically prove that these asparagines are glycosylated and then deglycosylated with deamidation to aspartic acid to sequence edit the SKN-1A protein. Regulation of proteasome subunit genes by truncated (non-ER-associated and therefore non-N-glycosylated) forms of SKN-1 only occurs if the asparagine residues within the N-linked glycosylation motifs are genetically replaced by aspartate. The fact that conversion of the same asparagine residues to alanine has no effect on truncated SKN-1A[cut] indicates regulation of proteasome subunit genes requires this precise change in amino acid sequence.

We do not yet understand how sequence editing of SKN-1A alters its function as a transcriptional regulator. The edited residues are unlikely to alter DNA binding, which depends on a separate C-terminal CnC domain far from the edited sites (Blackwell et al., 1994). Acidic amino acid residues are important for the function of some transactivation domains (Triezenberg, 1995), suggesting that these particular N to D edits may modulate the transactivation function of SKN-1A. Phylogenetic analysis of the SKN-1A glycosylation sites and surrounding sequences endorses the function of acidic residues in this domain. In addition to the four glycosylation motifs, this domain contains five conserved acidic residues and the N325 glycosylation site is disrupted in C. brenneri by a deglycosylation-mimetic N to D substitution (Fig. 1b). We speculate that activated SKN-1A interacts with cofactors that specifically recognize the sequence-edited domain and facilitate activation of proteasome subunit genes (Fig. 6). It will be of interest to identify sequence-dependent interactors and understand how they influence target specificity of SKN-1.

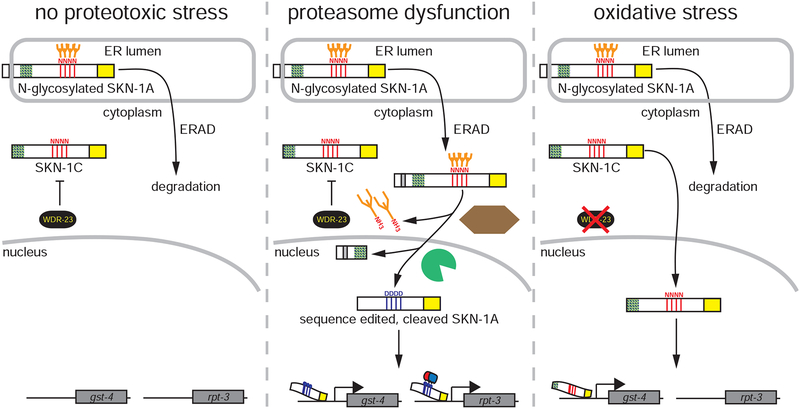

Figure 6. Model showing stress-responsive regulation of gene expression by SKN-1A and SKN-1C.

Under basal conditions cytoplasmic SKN-1C is inhibited by WDR-23, whereas N-glycosylated SKN-1A is rapidly degraded by the proteasome following release from the ER by ERAD (feedback control of basal proteasome expression by SKN-1A may also occur under this condition but is not shown). During proteasome dysfunction, SKN-1A is not degraded and undergoes PNG-1 dependent sequence editing and proteolytic cleavage by DDI-1. This truncated, sequence edited form of SKN-1 activates expression of both gst-4 and rpt-3. Sequence edits at N-glycosylation sites introduced by PNG-1 are required for regulation of rpt-3, likely by mediating recruitment of unidentified cofactors. During oxidative stress, inhibition of SKN-1C is relieved, and SKN-1C (which does not undergo sequence editing) activates expression of gst-4 but does not induce rpt-3.

PNGase is a glycosylation-dependent peptide sequence editing enzyme.

PNGase is highly conserved throughout eukaryotes, and removes N-linked glycans from ERAD substrate proteins to ensure their efficient disposal by the proteasome (Suzuki, 2016). It has been known for more than 20 years that deglycosylation occurs via a deamidation reaction that causes conversion of glycosylated asparagine residues to aspartate, effectively editing the sequence of the substrate peptide, but this activity was of unknown functional significance (Suzuki et al., 1994; 1993). Our rescue of png-1 mutants by expression of sequence altered SKN-1 reveals that the bulk deglycosylation of cytoplasmic glycoproteins by PNG-1/NGLY1 is dispensable for bortezomib resistance. Rather, PNGase performs an essential function as the glycosylation-dependent protein sequence editor of a single target protein, the transcription factor SKN-1A/Nrf1. Fluorescent protein variants that require asparagine deamidation by PNGase for maturation of the fluorophore have been engineered as tools for studying ERAD (Grotzke et al., 2013), but SKN-1A is the first endogenous protein that depends on this deamidation reaction for its normal function. This finding raises the possibility that other proteins may require PNGase-dependent sequence editing of N-glycosylated asparagine residues for their function. Identification (for example from mass-spec. proteomics data) of peptides with N to D substitutions at N-glycosylation motifs may reveal further substrates of PNGase-dependent sequence editing.

SKN-1A and SKN-1C are distinct stress-responsive transcription factors that function analogously to mammalian Nrf1 and Nrf2.

This study reveals that SKN-1A and SKN-1C, though both encoded by the skn-1 gene, are two functionally distinct transcription factors. Not only is the context-specific activation of each isoform controlled by a different mechanism, but PNGase-dependent sequence editing means that despite their shared DNA binding domain, SKN-1A and SKN-1C regulate different target genes (Fig. 6), mirroring the relationship between Nrf1 and Nrf2. The DNA binding domains of Nrf1 and Nrf2 are highly homologous and bind to the same DNA sequence motif (Biswas and Chan, 2010; Ma, 2013; Motohashi et al., 2002). Despite this similarity, Nrf1 and Nrf2 largely function non-redundantly in responses to proteasome dysfunction and oxidative stress respectively (Leung et al., 2003; Ohtsuji et al., 2008; Radhakrishnan et al., 2010; Steffen et al., 2010). Interestingly, WDR-23/WDR23 specifically inhibits SKN-1C in C. elegans and Nrf2 in humans (Lo et al., 2017). Considering the striking parallels in their modes of regulation and physiological functions, it is apparent that SKN-1A is C. elegans Nrf1, whereas SKN-1C functions analogously to Nrf2. Phylogenetic comparisons suggest that the vertebrate Nrf1 and Nrf2 genes arose from duplication of an ancestral locus that, like skn-1, encoded distinct ER-associated and cytoplasmic isoforms through alternative splicing (Fuse and Kobayashi, 2017). As such, animal cells deploy distinct SKN-1/Nrf isoforms to combat distinct proteotoxic challenges.

These findings prompt a re-evaluation of the role of SKN-1A/Nrf1 and SKN-1C/Nrf2 in longevity. skn-1 is essential for many interventions that extend lifespan [reviewed in (Blackwell et al., 2015)], but nearly all studies of SKN-1 function have analyzed mutations or RNAi conditions that inactivate both SKN-1A and SKN-1C. We have found that SKN-1A promotes longevity (NL unpublished), and several studies have shown that WDR-23 and SKN-1C affect lifespan (Choe et al., 2009; Curran and Ruvkun, 2007; Tang and Choe, 2015b; Tullet et al., 2008). Because both oxidative protein damage (mitigated by SKN-1C/Nrf2), and impaired proteasome function (compensated by SKN-1A/Nrf1) could contribute to aging, it will be important to clarify the extent to which various longevity interventions depend on each SKN-1 isoform.

PNG-1/NGLY1 and SKN-1A/Nrf1 control proteostasis.

The proteasome mediates the selective degradation of most proteins; maintaining adequate proteasome function is essential for proteostasis and cell viability. SKN-1A controls both basal and induced proteasome subunit gene expression and proteasome activity in C. elegans. The orthologues of PNG-1 and SKN-1A in Drosophila, mice and human cells also control basal and induced proteasome subunit gene expression (Grimberg et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2013; 2011; Owings et al., 2018; Radhakrishnan et al., 2010; Rodriguez et al., 2018; Steffen et al., 2010; Tomlin et al., 2017), indicating that deglycosylation of SKN-1A/Nrf1 is a conserved requirement for regulation of proteasome function in animals.

Inadequate proteasome function is associated with pathology of aging and diseases including neurodegeneration and cancer (Rousseau and Bertolotti, 2018; Saez and Vilchez, 2014). Mutations affecting NGLY1 (the human png-1 orthologue) cause progressive neurodegeneration (Enns et al., 2014; Lam et al., 2017). In the mouse, brain-specific Nrf1 inactivation causes a similar neurodegenerative phenotype (Lee et al., 2011). This suggests that defective regulation of the proteasome by Nrf1 causes neurodegeneration in NGLY1 deficiency. Neurodegeneration is a feature of some congenital disorders of glycosylation (Freeze et al., 2015). Because sequential glycosylation and deglycosylation are necessary for SKN-1A function, proteasome dysregulation could also occur in these conditions. While inactivation of SKN-1A/Nrf1 is catastrophic, our results suggest that enhancing SKN-1A/Nrf1 activity can enhance proteasome function and increase resistance to proteotoxic insults. A recent study found that a pharmacological activator of Nrf1 is protective in a mouse model of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (Bott et al., 2016). Our data support the hypothesis that boosting proteasome levels via Nrf1 can enhance proteostasis and may be a useful approach for treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

STAR METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Gary Ruvkun (ruvkun@molbio.mgh.harvard.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

C. elegans maintenance and genetics.

C. elegans were maintained on standard media at 20°C and fed E. coli OP50. A list of strains used in this study is provided in the Key Resources Table. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). png-1(ok1654) was generated by the C. elegans Gene Knockout Project at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, part of the International C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-HA-peroxidase | Roche | Cat#12013819001 |

| Anti-Actin | Abcam | Cat#3280 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody, HRP | Thermo Fisher | Cat#31430 RRID: AB_228307 |

| Bacterial Strains | ||

| E. coli OP50 | CGC | N/A |

| E. coli HT115 | CGC | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Bortezomib | LC Laboratories | Cat#B1408 |

| Juglone | Cayman Chemical Company | Cat#16216 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| TURBO DNA-free kit | Invitrogen | Cat#AM1907 |

| High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat#4368814 |

| Power SYBR Green PCR master mix | Thermo Fisher | Cat#4367659 |

| NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix | New England Biolabs | Cat#E2621L |

| Q5 Site-directed mutagenesis kit | New England Biolabs | Cat#E0554S |

| Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate | Thermo Fisher | Cat#32209 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C. elegans strain CL2166: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III | CGC | CL2166 |

| C. elegans strain CL2006: dvIs2[unc-54p::Aβ1–42] | CGC | CL2006 |

| C. elegans strain GR2183: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2183 |

| C. elegans strain GR2197: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; skn-1(mg570) IV | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2197 |

| C. elegans strain GR2198: mgTi1[rpl-28p::skn-1a::gfp, unc-119(+)] I; unc-119(ed3) III | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2198 |

| C. elegans strain GR2211: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; ddi-1(mg571) IV | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2211 |

| C. elegans strain GR2212: unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi4[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a::gfp, unc-119(+)] | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2212 |

| C. elegans strain GR2213: unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi5[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a::gfp, unc-119(+)] | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2213 |

| C. elegans strain GR2215: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; sel-1(mg547) V | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2215 |

| C. elegans strain GR2225: unc-119(ed3) III; ddi-1(mg571) IV; mgTi5[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a::gfp, unc-119(+)] | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2225 |

| C. elegans strain GR2230: unc-119(ed3) III; sel-1(mg547) V; mgTi4[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a::gfp, unc-119(+)] | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2230 |

| C. elegans strain GR2234: png-1(ok1654) mgTi1[rpl-28p::skn-1a::gfp, unc-119(+)] I; unc-119(ed3) III | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2234 |

| C. elegans strain GR2236: png-1(ok1654) I; mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2236 |

| C. elegans strain GR2245: skn-1(mg570) IV | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2245 |

| C. elegans strain GR2246: png-1(ok1654) I | Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016 | GR2246 |

| C. elegans strain GR3081: png-1(ok1654) I; dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; skn-1(lax188) IV. | this study | GR3081 |

| C. elegans strain GR3083: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; skn-1(mg570) IV | this study | GR3083 |

| C. elegans strain GR3084: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp]II; skn-1(lax188) IV | this study | GR3084 |

| C. elegans strain GR3085: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; skn-1(lax188mg673)[SKN-1A:G2STOP, E237K; SKN-1C: E147K] IV | this study | GR3085 |

| C. elegans strain GR3086: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp]II; skn-1(mg672)[SKN-1A:Δ155–167, SKN-1C:Δ65–77] IV | this study | GR3086 |

| C. elegans strain GR3087: unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi4[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3087 |

| C. elegans strain GR3088: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; mgTi4[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3088 |

| C. elegans strain GR3090: mgIs77[rpl-28p::ub(G76V)::gfp, unc-119(+), myo-2p::mcherry] V | this study | GR3090 |

| C. elegans strain GR3093: unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi18 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[Δ155–167]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3093 |

| C. elegans strain GR3094: skn-1(mg570) IV; mgIs77[rpl-28p::ub(G76V)::gfp, unc-119(+), myo-2p::mcherry] V | this study | GR3094 |

| C. elegans strain GR3095: ddi-1(mg571) IV; mgIs77[rpl-28p::ub(G76V)::gfp, unc-119(+), myo-2p::mcherry] V | this study | GR3095 |

| C. elegans strain GR3096: png-1(ok1654) I; mgIs77[rpl-28p::ub(G76V)::gfp, unc-119(+), myo-2p::mcherry] V | this study | GR3096 |

| C. elegans strain GR3099: unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi20[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3099 |

| C. elegans strain GR3100: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi20[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3100 |

| C. elegans strain GR3101: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi20[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3101 |

| C. elegans strain GR3102: png-1(ok1654) I; mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; mgTi20[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3102 |

| C. elegans strain GR3103: skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi20[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3103 |

| C. elegans strain GR3104: png-1(ok1654) I; mgTi20[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3104 |

| C. elegans strain GR3106: unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi22[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3106 |

| C. elegans strain GR3107: unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi23[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3107 |

| C. elegans strain GR3109: unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi25[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4NA]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3109 |

| C. elegans strain GR3115: unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi28[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4NA]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3115 |

| C. elegans strain GR3116: unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi29[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3116 |

| C. elegans strain GR3117: unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi30[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c:: gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3117 |

| C. elegans strain GR3118: unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi21[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3118 |

| C. elegans strain GR3119: unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi22[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3119 |

| C. elegans strain GR3120: unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi25[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4NA]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3120 |

| C. elegans strain GR3121: unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi26[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4NA]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3121 |

| C. elegans strain GR3122: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; mgTi20[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3122 |

| C. elegans strain GR3123: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; mgTi31[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c:: gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3123 |

| C. elegans strain GR3125: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi21[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3125 |

| C. elegans strain GR3126: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi22[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3126 |

| C. elegans strain GR3127: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi27[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4NA]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3127 |

| C. elegans strain GR3128: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi28[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4NA]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3128 |

| C. elegans strain GR3129: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi29[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3129 |

| C. elegans strain GR3130: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi30[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c:: gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3130 |

| C. elegans strain GR3131: unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi23[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3131 |

| C. elegans strain GR3132: unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi24[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3132 |

| C. elegans strain GR3133: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi23[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3133 |

| C. elegans strain GR3134: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi24[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3134 |

| C. elegans strain GR3135: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; mgTi16[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3135 |

| C. elegans strain GR3136: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; mgTi21[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3136 |

| C. elegans strain GR3137: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; mgTi23[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3137 |

| C. elegans strain GR3138: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; mgTi24[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3138 |

| C. elegans strain GR3139: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; mgTi27[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4NA]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3139 |

| C. elegans strain GR3140: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; mgTi28[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4NA]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3140 |

| C. elegans strain GR3194: dvIs2[unc-54p::Aβ1–42]; mgTi20[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3194 |

| C. elegans strain GR3252: unc-119(ed3) III; ddi-1(mg571) IV; mgTi18[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[Δ155–167]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3252 |

| C. elegans strain GR3253: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; ddi-1(mg571) IV; mgTi20[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3253 |

| C. elegans strain GR3254: unc-119(ed3) III; sel-1(mg547) V; mgTi25[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4NA]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3254 |

| C. elegans strain GR3255: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi34[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NNND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3255 |

| C. elegans strain GR3256: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi36[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NNDD]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3256 |

| C. elegans strain GR3257: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi35[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DDNN]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3257 |

| C. elegans strain GR3258: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi37[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DDND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3258 |

| C. elegans strain GR3259: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi38[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DNNN]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3259 |

| C. elegans strain GR3260: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi39[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DDDN]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3260 |

| C. elegans strain GR3261: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi40[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NNDN]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3261 |

| C. elegans strain GR3262: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi41[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DNDD]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3262 |

| C. elegans strain GR3263: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi42[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NDNN]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3263 |

| C. elegans strain GR3264: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi44[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NDND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3264 |

| C. elegans strain GR3265: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi45[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DNDN]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3265 |

| C. elegans strain GR3266: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi46[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NDDN]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3266 |

| C. elegans strain GR3267: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi47[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DNND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3267 |

| C. elegans strain GR3268: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi48[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3268 |

| C. elegans strain GR3269: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi43[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NDDD]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3269 |

| C. elegans strain GR3270: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; ddi-1(mg571) IV; mgTi48[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3270 |

| C. elegans strain GR3271: unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi48[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3271 |

| C. elegans strain GR3272: mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; skn-1(mg570) IV; mgTi48[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3272 |

| C. elegans strain GR3273: png-1(ok1654) I; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi48[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3273 |

| C. elegans strain GR3274: png-1(ok1654) I; mgIs72[rpt-3p::gfp] II; unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi48[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3274 |

| C. elegans strain GR3288: unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi29[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3288 |

| C. elegans strain GR3289: unc-119(ed3) III; mgTi48[rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4ND]::gfp, unc-119(+)] | this study | GR3289 |

| C. elegans strain N2: + | CGC | N2 |

| C. elegans strain SPC168: dvIs19[gst-4p::gfp] III; skn-1(lax188) IV. | CGC | SPC168 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S1. | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid: pNL262 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[Δ155–167]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL336 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4NA]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL240 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016 | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL273 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[4ND]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL302 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c::GFP::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL333 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL334 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1c[4ND]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL313 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4ND]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL337 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, 4NA]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL368 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DNNN]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL369 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NDDD]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL370 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DDDN]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL371 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NNND]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL372 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DDNN]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL373 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NNDD]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL374 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DDND]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL375 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NNDN]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL376 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DNDD]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL377 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NDNN]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL378 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NDND]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL379 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DNDN]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL380 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, NDDN]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL381 rpl-28p::HA::skn-1a[cut, DNND]::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL121 rpl-28p::ub(G76V)::gfp::tbb-2 (Minimos) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pJW1285 Dual Cas9 + sgRNA expression vector. |

Ward, 2015. | Addgene: #61252 |

| Plasmid: pNL300 Cas9 + sgRNA targeting skn-1 at cleavage site (SKN-1A 155–167) |

This study | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL219 Cas9 + sgRNA targeting skn-1a exon 1. |

Lehrbach and Ruvkun, 2016 | N/A |

| Plasmid: pNL243 Cas9 + sgRNA targeting dpy-10 |

This study | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | Rasband, W.S (NIH) |

https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Clustal Omega | EMBL-EBI | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/ |

| Ape (A plasmid editor) | M. Wayne Davis | http://jorgensen.biology.utah.edu/wayned/ape/ |

| Graphpad Prism | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Zen | Zeiss | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/us/products/microscope-software/zen.html |

METHOD DETAILS

Genome modification by CRISPR/Cas9.

Guide RNAs were selected by searching the desired genomic interval for ‘NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNRRNGG’, using Ape DNA sequence editing software (http://biologylabs.utah.edu/jorgensen/wayned/ape/). Guide RNA constructs were generated using the Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (New England Biolabs #E0554S) to alter pJW1285 (Ward, 2015). Mutagenic oligonucleotides are listed in Table S1. We used editing of dpy-10 (to generate cn64 rollers) as phenotypic co-CRISPR marker (Arribere et al., 2014; Ward, 2015). Injection mixes contained 60 ng/μl each of the dpy-10 co-CRISPR and gene of interest targeting guide RNA/Cas9 construct, and 50 ng/μl each of the dpy-10 co-CRISPR and gene of interest repair oligos. Repair oligos are listed in Table S1. After injections, cn64/+ roller progeny were selected, and the presence of the desired edit was detected by diagnostic PCR and subsequently confirmed by sequencing.

RNAi by feeding.

RNAi by feeding was performed using E. coli HT115 expressing double stranded RNA corresponding to wdr-23 or tkt-1, or containing a control dsRNA expression plasmid that does not contain sequence corresponding to any C. elegans gene (Kamath and Ahringer, 2003). To prevent contamination by E. coli OP50, animals were added to RNAi plates by picking gravid adults into 10 μl bleach solution on the edge of the plate. Progeny were analyzed for RNAi-induced phenotypes following 2–4 days.

Transgenesis.

Cloning was performed using the NEBuilder HiFi DNA assembly kit (New England Biolabs, #E2621L). All constructs were assembled in pNL43, a modified version of pCFJ909 containing the pBluescript MCS, and are described in more detail below. MiniMos transgenic animals were isolated as described, using unc-119 rescue to select transformants (Frøkjaer-Jensen et al., 2014). Extra-chromosomal arrays were generated using myo-2::mcherry as a co-injection marker. EMS mutagenesis was used to induce integration of extrachromosomal arrays

Integrated array transgenes.

Ub(G76V)::GFP: This construct was generated to drive ubiquitous expression of ub(G76V)::GFP under control of the rpl-28 promoter. A synthesized DNA fragment encoding ubiquitin was cloned in frame with GFP to generate the Ub(G76V)::GFP coding sequence. The G76V mutation was introduced by the oligos used for Gibson assembly. This was inserted into pNL43 with the rpl-28 promoter (605 bp immediately upstream of the rpl-28 start codon) and tbb-2 3’UTR (376 bp immediately downstream of the tbb-2 stop codon).

MiniMos constructs.

To generate constructs that express different forms of SKN-1, we used the skn-1c and skn-1a constructs described in Lehrbach and Ruvkun 2016. skn-1a[Δ155–167]::gfp was generated by deleting sequence corresponding to amino acids 155–167 of SKN-1A, by isothermal assembly of appropriate fragments of the skn-1a minigene. SKN-1A[cut] constructs were generated by Gibson assembly using a fragment of the SKN-1A minigene corresponding to amino acids 168–623 of SKN-1A. Constructs containing substitutions (4NA: N325A, N338A, N370A, N403A, and 4ND: N325D, N338D, N370D, N403D) were generated by replacing the DNA sequence corresponding to amino acids 300–435 of SKN-1A with a synthetic DNA fragment containing the desired alterations. All SKN-1 constructs were inserted into pNL43 with the rpl-28 promoter, an N-terminal HA tag, a C-terminal GFP tag, and the tbb-2 3’UTR. A schematic describing these SKN-1A constructs is shown in Figure S2.

SKN-1A[cut] constructs containing each of the possible combinations of single, double and triple asparagine to aspartate substitutions at N325, N338, N370 and N403 were generated by isothermal assembly using appropriate fragments from the SKN-1A[cut] and SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] constructs. These constructs were inserted into pNL43 with the rpl-28 promoter, an N-terminal HA tag, a C-terminal GFP tag, and the tbb-2 3’UTR.

Microscopy

Low magnification bright field and GFP fluorescence images (those showing larval growth, rpt-3p::gfp, gst-4p::gfp or rpl-28p::ub(G76V)::gfp) were collected using a Zeiss AxioZoom V16, equipped with a Hammamatsu Orca flash 4.0 digital camera, and using Axiovision software. High magnification DIC and GFP fluorescence images (those showing subcellular localization of SKN-1A/C/cut::GFP) were collected using a Zeiss Azio Image Z1 microscope, equipped with a Zeiss AxioCam HRc digital camera, using Axiovision software. Images were processed and analyzed using ImageJ software. For all fluorescence images, images shown within the same figure panel were collected using the same exposure time and then processed identically. Drug treatments were performed by transferring animals to bortezomib or vehicle supplemented NGM plates (with E. coli OP50) 6–8 hours before imaging. To quantify rpt-3p::gfp expression, the maximum pixel intensity within a transverse section approximately 25 μm posterior to the pharynx of adult animals was measured. To quantify UB(G76V)::GFP levels, maximum pixel intensity within the anterior-most pair of intestinal cells of L4-stage animals was measured.

Bortezomib sensitivity assays

Bortezomib sensitivity was assessed by the ability of animals to develop, or survive as adults, on plates supplemented with various concentrations of bortezomib (LC Laboratories, #B1408). Plates were supplemented with bortezomib by directly spotting a bortezomib solution on top of NGM plates seeded with OP50. The bortezomib solution was allowed to dry into the plates overnight before beginning the assay. All treatment conditions contained less than 0.1% DMSO. For developmental assays, 5–10 L4 animals were picked to a fresh plate supplemented with 0.4 μg/ml bortezomib. Plates were imaged to assess the growth of progeny after 5 days. For adult survival assays, 30 L4 animals were picked to fresh plates supplemented with 0.04 μg/ml bortezomib. The survival of these animals was scored after 4 days. For strains that are able to develop on this concentration of bortezomib, animals were transferred to fresh bortezomib supplemented plates after 2–3 days to ensure that the assay animals could be distinguished from their progeny.

Aβ-induced paralysis assay

For each assay at least 100 starvation-synchronized L1 stage animals were raised at 25°C. Animals grown under this condition reach adul thood after ~48 hours. Starting at 48 hours, animals were scored for paralysis every 24 hours. Animals were scored as paralyzed if they showed no sign of movement after tapping the plate or gentle prodding.

qRT-PCR.

Drug treatments were performed in liquid culture in 6-well tissue culture plates. In each well we mixed C. elegans suspended in S-basal (~3000 L4 animals from a synchronized culture grown at 20°C on NGM agar plates) and E. coli OP50 in S-Basal (equivalent to E. coli from ~4mL saturated LB culture), supplemented with 50 μg/ml Carbenicillin, and the desired concentration of bortezomib, and made the mixture up to a final volume of 700 μl with S-Basal. All wells contained 0.01% DMSO. The tissue culture plates were sealed with Breathe-Easy adhesive film (Millipore Sigma, #Z380059) and incubated at 20°C for 7–9 hours. After the treatment the animals were collected to 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes and washed twice in water to remove bacteria. The worm pellet was resuspended in 1 mL TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, #15596), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. RNA extraction was pe rformed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples were DNAse treated with using the TURBO DNA-free kit (Invitrogen, #AM1907). Reverse transcription was performed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Thermo Fisher, #4368814). Real time PCR was performed using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real Time PCR System instrument and Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Thermo Fisher, #4367659). Expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method, normalizing to the mRNA of the ribosomal subunit gene rps-23. Oligonucleotide primers used are listed in Table S1.

Western blot following bortezomib treatment.

Drug treatments were performed in liquid culture in 6-well tissue culture plates. In each well we mixed C. elegans suspended in S-basal (~1000–2000 worms collected from a mixed stage culture grown at 20°C on NGM agar plate s) and E. coli OP50 in S-Basal (equivalent to E. coli from ~ 4mL saturated LB culture), supplemented with 50 μg/ml Carbenicillin, and the desired concentration of bortezomib, and made the mixture up to a final volume of 700 μl. All wells contained 0.01% DMSO. The tissue culture plates were sealed with Breathe-Easy adhesive film (Millipore Sigma, #Z380059) and incubated at 20°C for 7–9 hours. After the treatmen t the animals were collected to 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes, washed twice in PBS to remove bacteria and the worm pellet was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The worm pellet was briefly thawed on ice, mixed with an equal volume of 4× LDS-Sample buffer (Boston Bioproducts, #BP-610), heated to 95°C for 10 min, a nd centrifuged at 16,000g for 10 min to pellet debris. SDS-PAGE was performed using NuPAGE apparatus, 4–12% polyacrylamide Bis-Tris pre-cast gels (Invitrogen, #NP0321). Western blotting was performed using the iBlot 2 transfer system and nitrocellulose transfer stacks (Invitrogen, #IB23002) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following antibodies were used: HRP-conjugated mouse anti-HA (Roche, # 12013819001), and mouse anti-Actin (Abcam; #3280), HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (Thermo Fischer, #31430).

Multiple alignment of protein sequences.

Multiple alignment was performed using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical parameters, including the exact value of ‘n’, descriptive statistics (mean +/− standard deviation) are stated in the Figure legends. For bortezomib survival and Aβ-induced paralysis assays, ‘n’ refers to the number of replicate experiments performed, and each replicate experiment was performed with independent populations of animals. The number of animals analyzed per replicate in these experiments is indicated in the Figure legends. For quantification of GFP reporter fluorescence, ‘n’ indicates the number of individual animals analyzed. Individuals were selected for imaging at random from populations of animals of the indicated genotype. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. Statistical tests used are indicated in the Figure legends. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05, as determined by one-way or two-way ANOVA and subsequent correction for multiple testing.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1 Related to Figure 1. Localization and processing of SKN-1A[4NA] and SKN-1A[Δ155–167]. (a) Fluorescence images showing localization of SKN-1A and SKN-1A[4NA] under control conditions and in animals exposed to 5 μg/ml bortezomib. Both SKN-1A and SKN-1A[4NA] localize to the nucleus during proteasome inhibition by bortezomib but not under control conditions. SKN-1A and SKN-1A[4NA] are detected via a C-terminal GFP tag. Scale bar 10 μm. (b) Western blot showing expression and processing of a SKN-1A and SKN-1A[4NA] in animals treated with 5 μg/ml bortezomib or DMSO control. SKN-1A and SKN-1A[4NA] are both detected via an N-terminal HA tag. In the wild-type, bortezomib treatment leads to accumulation of a ~20 kD peptide resulting from proteolytic cleavage. This peptide also accumulates in animals expressing SKN-1A[4NA] indicating that both SKN-1A and SKN-1A[4NA] undergo proteolytic activation. High levels of full length SKN-1A and SKN-1A[4NA] (both ~110 kD) accumulate in sel-1 mutant animals even in the absence of proteasome inhibitor, showing that both SKN-1A and SKN-1A[4NA] are normally targeted for proteasomal degradation by ERAD. (c) Western blot comparing the expression and processing of SKN-1A and SKN-1A[Δ155–167]. SKN-1A and SKN-1A[Δ155–167] are detected via an N-terminal HA tag. In wild type animals bortezomib treatment causes accumulation of a ~20 kD peptide from SKN-1A but not SKN-1A[Δ155–167]. In ddi-1 mutant animals SKN-1A accumulates as full length protein (~110 kD) that co-migrates with SKN-1A[Δ155–167] expressed in the wild type. The migration of SKN-1A[Δ155–167] does not change in ddi-1 mutant animals. * indicates a non-specific band.

Figure S2 Related to Figure 2. A panel of transgenes to examine the role of proteolytic cleavage and deglycosylation-dependent sequence editing in the function of SKN-1A. (a) schematic showing the structure of each transgene. (b-d) fluorescence micrographs showing expression and localization of each form of SKN-1 expressed by the transgenes shown in (a). All transgenes use the same ubiquitous and strong rpl-28 ribosomal gene promoter. Images show animals treated with DMSO control or 5 μg/ml bortezomib. Nuclear SKN-1A, SKN-1A[4ND], SKN-1C, and SKN-1C[4ND] is only detectable in bortezomib treated animals as these forms of SKN-1 undergo proteasome dependent degradation. Nuclear SKN-1A[cut] and SKN-1A[cut, 4ND] is detectable in both bortezomib and control animals. Scale bars 10 μm.

Figure S3 Related to Figure 2. Analysis of vulval rupture in animals exposed to bortezomib during development. Percentage of young adult animals that show vulval rupture following development in the presence of (a) 0.4 μg/ml bortezomib, or (b) DMSO control. skn-1a(mg570) mutants partially rescued by expression of SKN-1C[4ND] show frequent vulval rupture in the presence of bortezomib but not under control conditions. Results of n=3 replicate experiments are shown; error bars show mean +/− standard deviation. Rupture of >100 animals was tested for each replicate.