Significance

This paper addresses factors that contribute to the enzymatic activity of the cGAS–cGAMP–STING pathway, a sentinel platform that senses the presence of foreign or mislocalized DNA in the cytoplasm, triggering innate immunity and interferon production. Recent studies have emphasized the contribution of the basic N-terminal segment of cGAS to enzymatic activity by demonstrating that DNA-induced liquid-phase condensation of cGAS activates innate immune signaling. We identify an additional contribution associated with a basic site-C cGAS–DNA interface, which, when mutated, disrupts cGAMP production and multivalency-induced liquid-phase condensation. We have also identified and structurally characterized a human cGASCD–DNA complex, which together with apo h-cGASCD, provides scaffolds for inhibitor drug design targeted toward the control of autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: h-cGAS–DNA complex, DNA-binding cGAS mutations, multivalent interactions, liquid-phase condensation

Abstract

The cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)–cGAMP–STING pathway plays a key role in innate immunity, with cGAS sensing both pathogenic and mislocalized DNA in the cytoplasm. Human cGAS (h-cGAS) constitutes an important drug target for control of antiinflammatory responses that can contribute to the onset of autoimmune diseases. Recent studies have established that the positively charged N-terminal segment of cGAS contributes to enhancement of cGAS enzymatic activity as a result of DNA-induced liquid-phase condensation. We have identified an additional cGASCD–DNA interface (labeled site-C; CD, catalytic domain) in the crystal structure of a human SRY.cGASCD–DNA complex, with mutations along this basic site-C cGAS interface disrupting liquid-phase condensation, as monitored by cGAMP formation, gel shift, spin-down, and turbidity assays, as well as time-lapse imaging of liquid droplet formation. We expand on an earlier ladder model of cGAS dimers bound to a pair of parallel-aligned DNAs to propose a multivalent interaction-mediated cluster model to account for DNA-mediated condensation involving both the N-terminal domain of cGAS and the site-C cGAS–DNA interface. We also report the crystal structure of the h-cGASCD–DNA complex containing a triple mutant that disrupts the site-C interface, with this complex serving as a future platform for guiding cGAS inhibitor development at the DNA-bound h-cGAS level. Finally, we solved the structure of RU.521 bound in two alternate alignments to apo h-cGASCD, thereby occupying more of the catalytic pocket and providing insights into further optimization of active-site–binding inhibitors.

The sensing of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) by cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) is a danger signal in cells (1, 2), leading to conformational transitions within the cGAS sensor to form a catalytically competent pocket for generation of cyclic dinucleotide 2′,3′-cGAMP (3–8), which then acts as second messenger by binding and activating stimulator of IFN genes (STING) and inducing the expression of type I IFN (3, 9–11). Notably, cGAS is essential for the immune response to many microbes that usually present long DNA at low abundance to the cytoplasm (12–16). Consistent with this distinction, cGAS exhibits a DNA length-dependent manner of activation, with longer DNA duplexes producing a significantly stronger immune response of cGAS (14, 17–19).

Based on the structure of an N-terminally truncated mouse cGAS (m-cGASCD, where CD stands for catalytic domain) bound to a 39-bp DNA complex, a ladder model was proposed to explain the preferential activation of m-cGASCD by long DNA (17). In this model, m-cGASCD dimers were predicted to cooperatively bind at adjacent sites along two parallel-aligned long DNA duplexes, resulting in formation of a ladder-like complex. However, human cGAS (h-cGAS) exhibits different DNA-length specificity from m-cGAS for enhanced control of immune surveillance (14, 17, 20). Previous structural studies have primarily focused on dimeric mouse/porcine cGASCD–dsDNA complexes (5–7, 17, 21–23), and only recently has attention turned to related studies on a dimeric h-cGASCD(K187N and L195R)–DNA complex (20). This complex shows the human-specific K187 and L195 residues reduce the h-cGAS binding ability for short DNAs (<45 bp) in contrast to m-cGAS, thereby promoting DNA-length specificity of h-cGAS.

Recently, it has been shown that DNA-induced liquid-phase separation of cGAS promotes cGAMP production and innate immune signaling (24). This was primarily attributed to the enhancement of cGAS–DNA liquid-phase condensation by the basic and disordered N-terminal segment of cGAS, thereby facilitating multivalent DNA complex formation. These studies also established that long DNAs were more efficient than their shorter counterparts, as was the presence of Zn2+ cations, in promoting cGAS enzymatic activity and liquid-phase condensation.

We now report on the structure-based identification and characterization of an unanticipated h-cGAS–DNA interface (labeled site-C) that promotes cGAMP production and multivalency-induced liquid-phase condensation. We have used enzymatic assay, electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), spin-down assay, and turbidity assay, together with time-lapse imaging of liquid droplet formation, to monitor cGAMP production, and multivalency-induced liquid-phase condensation in this system. We have also investigated the impact of cGAS mutations of basic residues located on the cGAS–DNA site-C interface, including a pair of tumor mutations, on cGAMP formation and liquid-phase condensation. This cGAS–DNA interface is evolutionarily strengthened on proceeding from m-cGAS to h-cGAS, providing an additional molecular explanation of h-cGAS DNA sensing specificity.

These efforts in turn have not only allowed the design of a site-C disrupting triple mutant of h-cGASCD and structure determination of its dimeric h-cGASCD–DNA complex but also led to the identification of a site-C disrupting dual mutant to improve apo h-cGASCD crystallization. Such structures of dimeric h-cGASCD–DNA complexes (this study and ref. 20), together with the structure of apo dual mutant h-cGASCD, provide a robust platform for structural characterization of small-molecule inhibitors of cGAMP production in humans, thereby opening opportunities for therapeutic treatment of autoimmune diseases. As an example, we report on the structure of RU.521 inhibitor (25) bound in two alternate alignments within the catalytic pocket of apo h-cGASCD.

Results

Full-Length cGAS Proteins Can Exist as DNA-Free Dimers in Solution.

cGAS is composed of a flexible N-terminal domain and a C-terminal catalytic domain (designated cGASCD) (Fig. 1 A, Upper). We found that DNA-free full-length (FL) h-cGAS and m-cGAS exist as dimers in solution by size-exclusion chromatography coupled with in-line multiangle light-scattering analysis (SEC-MALS) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and D). By contrast, in the absence of the N-terminal domain, h-cGASCD (152–522) eluted as two peaks on a heparin column, that were determined to be monomers and dimers by SEC-MALS (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C), while nearly all m-cGASCD existed as monomers in solution (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E). Agilent RapidFire mass spectrometry (RF-MS) assays (25) showed that the dimerization of apo h-cGASCD is required for effective DNA-mediated cGAS activation (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F). Thus, apo h-cGAS and m-cGAS proteins can form DNA-free dimers, and the N-terminal domain of cGAS promotes the dimerization (26).

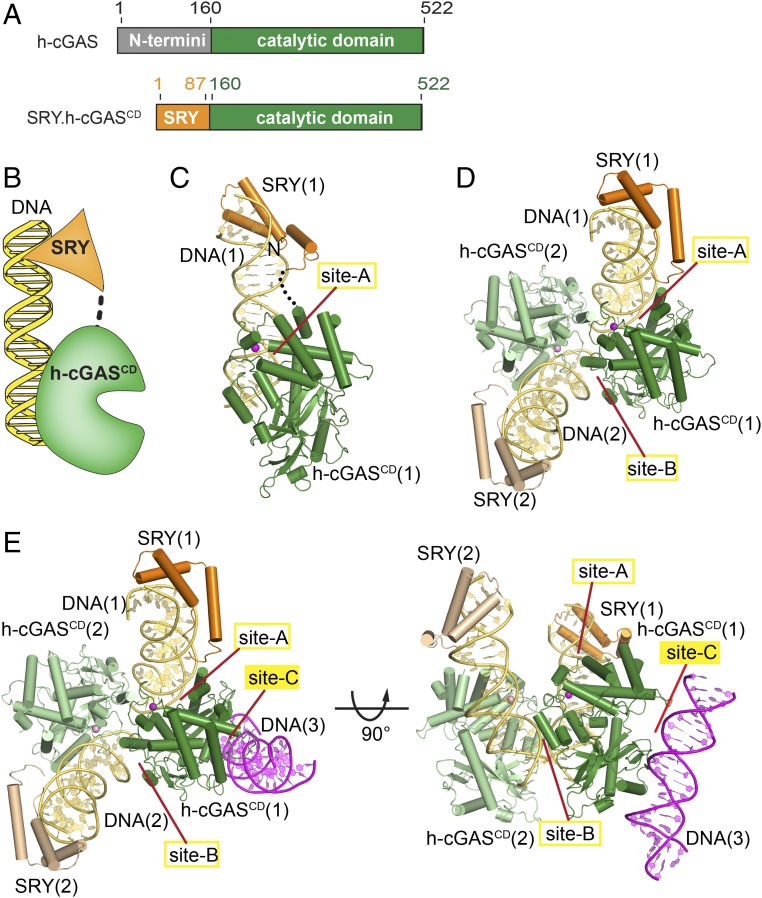

Fig. 1.

Identification of an additional protein–DNA interface in the crystal structure of the SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA complex. (A) Schematic drawing of human full-length (FL) cGAS protein, showing N-terminal domain in gray and catalytic domain (CD) in green, and a fusion SRY.h-cGASCD protein with the SRY domain in orange. Numbers above the sequence indicate the domain boundaries. (B) A schematic of the fusion SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA complex with the SRY domain binding to its sequence-specific DNA element and h-cGASCD binding nonsequence specifically to an adjacent DNA site. (C and D) Views of the monomeric (C) and dimeric (D) structure of the SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA complex. An individual h-cGASCD (1) interacts with DNA (1) (site-A) and DNA (2) (site-B) as reported previously for a dimeric complex (h-cGASCD in green and DNA in teal) (PDB ID code 4LEY). (E) Two views of the SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA complex highlighting an additional protein–DNA interface (site-C) involving recognition by cGASCD (1) of DNA (3) in magenta.

Structure of SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA Complex.

Besides promoting dimerization, the lysine/arginine-rich N-terminal domain of cGAS also has the potential for enhancing cGAS–DNA binding (27) as well as serves as the phosphoinositide-binding domain (28). To mimic FL h-cGAS and stabilize the protein–DNA interaction, we replaced the N-terminal domain of h-cGAS with the sequence-specific HMG box of human SRY (29), resulting in the formation of a hybrid protein, termed SRY.h-cGASCD, as shown in Fig. 1 A, Lower. Similar to apo h-cGASCD, apo SRY.h-cGASCD existed as both dimers and monomers in solution (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 G and H). SRY.h-cGASCD dimers, when mixed with a 21-bp DNA (plus 1-nt 5′overhang at either end) containing an SRY-sequence-specific element yielded diffraction quality crystals (I222 space group) that diffracted to 3.2-Å resolution, with the structure of the complex solved by molecular replacement using modified m-cGASCD–DNA structure (PDB ID code 4K96) and SRY–DNA structure (PDB ID code 2GZK) as search models (X-ray statistics listed in SI Appendix, Table S1). The final structure included residues 6–73 of SRY and residues 164–521 of h-cGASCD together with the entire length of bound DNA, while the linker segment between SRY and cGASCD was disordered in the structure of the complex. Each asymmetric unit contains one SRY.h-cGASCD bound with one DNA (Fig. 1C) and forms a dimeric SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA complex with its partner in the adjacent asymmetric unit (Fig. 1D), revealing a near-identical organization of dimers as reported previously for the dimeric m-cGASCD–DNA complex (21, 30).

The dimeric SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA complex contains a deep positively charged groove for dsDNA binding formed by two different interfaces of h-cGAS. Consistent with previous structural reports of cGASCD–DNA complexes, we refer to the two corresponding DNA-binding surfaces in the dimeric complex as site-A and site-B (Fig. 1D). The site-A provides an interface area of 649 Å2, while site-B provides an interface area of 360 Å2. The intermolecular site-A and site-B contacts between the protein and DNA in the complex are summarized in SI Appendix, Fig. S2A, with the majority of the contacts involving interactions between h-cGASCD and the sugar-phosphate backbone of the DNA, consistent with h-cGASCD sensing DNA in a non–sequence-specific manner. The entrance to the catalytic pocket widens on complex formation as reported previously (5).

Identification of an Additional DNA-Binding Interface in the SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA Complex.

The dimeric SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA structure and its positioning relative to the third adjacent asymmetric unit revealed an unanticipated additional interface for DNA binding, named site-C (Fig. 1E). The total interface area of site-C is 663 Å2, with this surface of cGAS showing an extended basic patch of positively charged residues formed mainly by three segments labeled the α-region (261–286), the KRKR-loop (299–302), and the KKH-loop (427–432) (Fig. 2A). The site-C intermolecular contacts between the protein and DNA in the complex are summarized in SI Appendix, Fig. S2B. The site-C interface (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) is compared with its site-A (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B) and site-B (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C) counterparts in the SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA complex, with the cGASCD domain shown in ribbon (left panel), electrostatic (middle panel), and intermolecular interface (in green, right panel) representations.

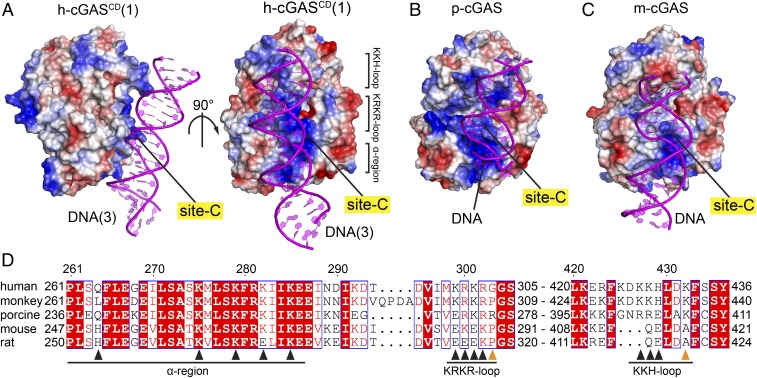

Fig. 2.

Site-C DNA interaction interface of cGAS is evolutionarily strengthened. (A) Two views of the basic cGASCD site-C DNA interface in the structure of the SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA complex, with the protein shown in an electrostatic representation and DNA colored in magenta. (B and C) The basic cGASCD site-C DNA interface in the structures of cGASCD–DNA complexes from porcine (B) (PDB ID code 4KB6) and mouse (C) (PDB ID code 4LEY), with the protein shown in an electrostatic representation and DNA colored in magenta. Electrostatic surface potentials were calculated in PyMol and contoured at ±100 (D) Sequence alignment of cGAS residues on the site-C interface from Homo sapiens (human; Uniprot Q8N884), Macaca mulatta (monkey; Uniprot A0A1D5QFG4), Sus scrofa (porcine; Uniprot I3LM39), Mus musculus (mouse; Uniprot Q8C6L5), and Rattus norvegicus (rat; Uniprot A0A0G2JVC4). Numbering above the sequences corresponds to that for h-cGAS. Black and orange triangles denote residues that interact with DNA at site-C partitioned into α-region, KRKR-loop and KKH-loop segments, with orange triangles in addition denoting tumor-associated mutation sites G303E and K432T. The alignment was visualized with ENDscript server.

Interestingly, although not reported previously, the corresponding site-C interface also exists in the previously published structures of DNA-bound porcine cGASCD (p-cGASCD; PDB ID code 4KB6) (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A) and m-cGASCD (PDB ID code 4LEY) (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Compared with h-cGASCD, the corresponding interactions between p-cGASCD and m-cGASCD with DNA at site-C are less extensive as reflected by the smaller surface areas for p-cGASCD (329 Å2) and for m-cGASCD (413 Å2), with the extent of basic patch for site-C decreasing in the order h-cGASCD (Fig. 2 A, Right), p-cGASCD (Fig. 2B) and m-cGASCD (Fig. 2C). Sequence alignment of cGAS proteins (31, 32) also showed that, at site-C, the basic residues of the α-region (261–286) are conserved between m-cGAS, p-cGAS, and h-cGAS, while the number of basic residues in the KRKR- and KKH-loops decrease on proceeding from h-cGAS to p-cGAS to m-cGAS (Fig. 2D). These results imply that the DNA binding affinity of site-C interface is evolutionarily strengthened on proceeding from m-cGAS to p-cGAS to h-cGAS.

Site-C Interface Is Essential for cGAS Activity.

The site-C interface between h-cGASCD (1) and DNA (3) is formed by an extended basic patch of positively charged residues originating from the α-region (Q264, K275, K279, K282, and K285), the KRKR-motif (K299, R300, K301, and R302), and the KKH-loop (K427, K428, and K432) (Fig. 2 A and B), allowing h-cGASCD to bind the phosphate backbone of the DNA through extensive nonspecific electrostatic interactions (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2B), while the side chain of R300 reaches into the minor groove of the DNA (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Details of h-cGASCD site-C DNA interaction interface and impact of site-C mutations on cGAMP formation. (A) Structural details of site-C interface of h-cGASCD (1) (green) bound to DNA (3) (magenta) in the SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA complex. Residues involved in intermolecular contacts are shown in yellow stick representation and partitioned between α-region, KRKR-loop and KKH-loop segments. The tumor-associated site-C mutations (G303E and K432T) are colored orange in the expanded panel. (B) Impact of site-C mutations on cGAMP production detected by RF-MS assay using FL h-cGAS and 100-bp DNA. Each reaction contains 25 nM DNA, 100 nM FL h-cGAS proteins, 100 µM ATP/GTP, incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Data are represented as means ± SD of three independent experiments. The data are partitioned by α-region, KRKR-loop, KKH-loop, and tumor (K432T and G303E) mutations on cGAMP production.

To test whether the site-C h-cGAS interface is essential for DNA-induced cGAMP production, we generated multiple Ala and charge reversal mutants of FL h-cGAS spanning site-C interfacial residues and tested their in vitro activities with a 100-bp immunostimulatory DNA (designated ISD100) for cGAMP production by RapidFire-MS (25). As shown in Fig. 3B, charge reversal mutants K275E, K279E, and K279E/K282E within the α-region of site-C showed about 3-fold to 5-fold reductions in cGAMP production, while K282E, K285E, and dual-mutant K275E/K285E also within the α-region of site-C essentially abolished activity. For mutations within the KRKR-loop, charge reversal single-mutant R300E showed about a 4-fold reduction in cGAMP production, while dual charge reversal mutant R300E/K301E and dual Ala mutant R300A/K301A abolished cGAMP production (Fig. 3B). For KKH-loop mutants, the dual charge reversal mutant K427E/K428E essentially abolished activity, while the dual Ala mutant K427A/K428A resulted in about a 3-fold reduction in cGAMP production (Fig. 3B). These mutagenesis results support the essential contribution of site-C interface for the enzymatic function of h-cGAS.

In addition, to further test whether the importance of the site-C interface is conserved between different species, we also prepared FL m-cGAS mutants of the site-C interface and tested their propensity for cGAMP formation as a function of DNA length. cGAMP formation was length-dependent and plateaued at 45 bp of DNA (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). Charge reversal substitutions of Lys by Gln at K268 and K275 (α-region of site-C), and K286 and K288 (KRKR-loop of site-C) resulted in 1.5- to 2-fold reduction of m-cGAS activity (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). These mutagenesis results are consistent with a reduced contribution by the site-C interface to the activation of m-cGAS, given that m-cGAS (with fewer basic residues in the KRKR and KKH loops, Fig. 2D) shows less extensive interactions with DNA at the site-C interface compared with h-cGAS.

Impact of Tumor-Associated Mutations Spanning the Site-C Interface.

The discovery of the site-C interface in the SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA complex allowed us to investigate the contribution of human cGAS tumor-associated mutations lining this interface to cGAMP activation. We identified and investigated the impact of two tumor-associated mutations, G303E within the KRKR-loop and K432T within the KKH-loop on cGAMP formation (orange triangles, Fig. 2D). In particular, K432T is a dominant mutation in uterine endometrioid carcinoma, with a variant allele frequency of 0.44 based on cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (33). Based on structural results, the G303E mutation would introduce a negatively charged residue within the basic patch of site-C, while K432T mutation would lead to the loss of a positively charged residue, both of which have the potential to weaken the site-C DNA binding (Fig. 3 A, close-up view). As shown in Fig. 3B, the G303E and K432T mutants caused about a 1.4-fold and about 2-fold reduction of cGAMP production, in the context of FL h-cGAS, respectively (Fig. 3B). These results establish that the two tumor-associated mutations located within site-C DNA binding interface impeded the DNA-induced cGAS activity.

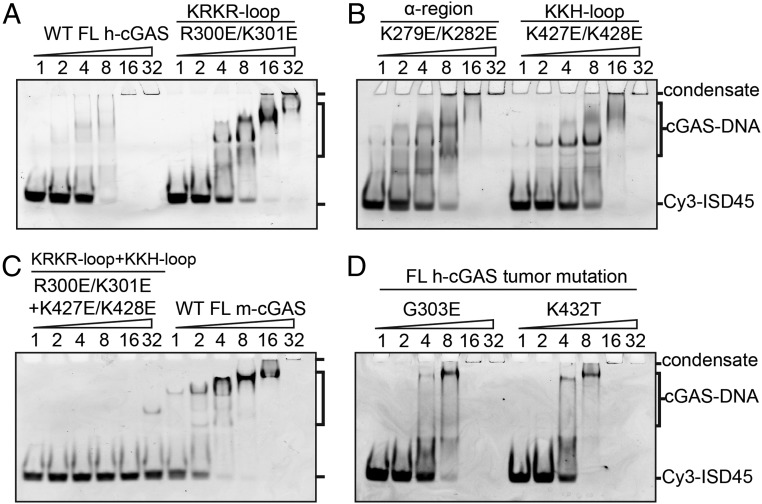

Site-C Interface of h-cGAS Is Essential for DNA Condensate Formation.

It has been shown that FL wild-type (WT) h-cGAS and m-cGAS exhibit different DNA binding behaviors using 45-bp immunostimulatory DNA (ISD45) in EMSA (20). WT m-cGAS can form either lower molecular-weight cGAS–DNA complex(es) or higher-order cGAS–DNA condensate staying on the top of the gel. By contrast, WT h-cGAS preferentially forms high-order cGAS–DNA condensate (20). Given that the site-C interface of cGAS has the potential to increase the multivalency of cGAS–DNA interactions, we hypothesized that the stronger site-C interface of h-cGAS should result in preferential formation of high-order cGAS–DNA condensate, while the smaller site-C interface of m-cGAS should lead to a mixture of lower-order cGAS–DNA complex(es) and cGAS–DNA condensate.

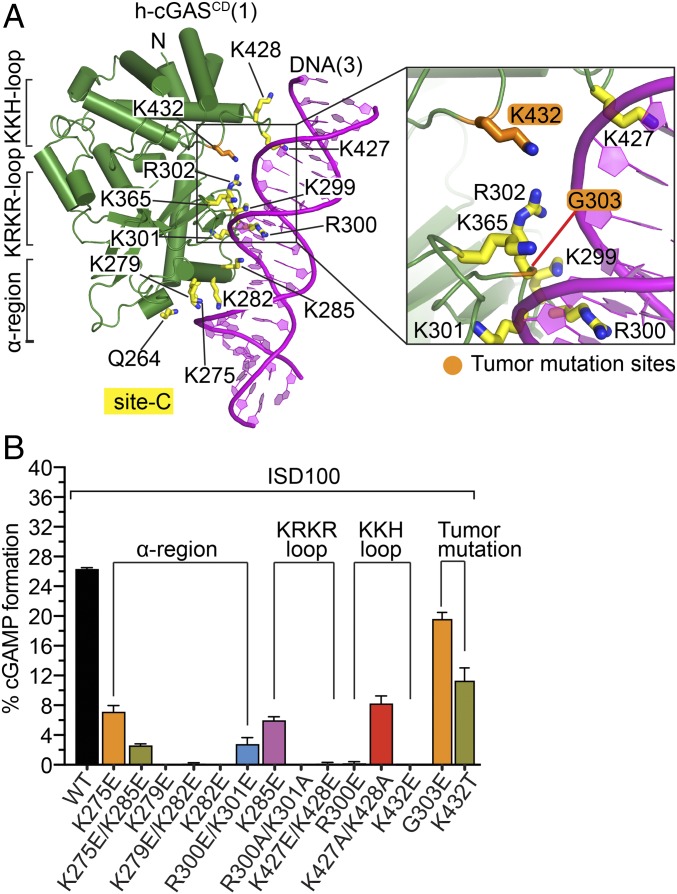

We next tested the binding behaviors of Cy3-labeled ISD45 45-mer DNA to FL WT h-cGAS and mutants spanning site-C interface using EMSA. As shown in Fig. 4A, most of WT h-cGAS-Cy3-ISD45 formed condensate staying on the top of the gel, similar to observations made previously (20, 22, 27). Dual charge reversal mutations on the site-C interface of h-cGAS (R300E/K301E, K279E/K282E, and K427E/K428E) resulted in not only reduction in DNA-binding ability but also significant appearance of a mixture of lower bands corresponding to formation of the lower molecular-weight cGAS–DNA complex(es) (Fig. 4 A and B), similar to what was observed for DNA complexes of FL WT m-cGAS (Fig. 4C). Combined mutations (R300E/K301E/K427E/K428E) at the site-C interface of h-cGAS essentially abolished DNA binding (Fig. 4C). In addition, two tumor-associated mutants (G303E and K432T) of FL h-cGAS also showed an increased formation of the lower-order cGAS–DNA complex(es) (Fig. 4D). These results imply that site-C mutations of h-cGAS exhibit DNA-binding behaviors that are similar to those observed for WT m-cGAS, which exhibits a smaller site-C DNA interface than h-cGAS.

Fig. 4.

Impact of the site-C interface mutations on DNA-binding property as monitored by EMSA. (A) Comparison of binding properties of WT (Left) and R300E/K301E KRKR-loop mutant (Right) of FL h-cGAS with DNA. (B) Comparison of binding properties of K279E/K282E α-region mutant (Left) and K427E/K428E KKH-loop mutant (Right) of FL h-cGAS with DNA. (C) Comparison of binding properties of R301E/K301E KRKR-loop and K427E/K428E KKH-loop mutants of FL h-cGAS (Left) and WT FL m-cGAS (Right) with DNA. (D) Comparison of binding properties of G300E (Left) and K432T (Right) FL h-cGAS tumor mutants with DNA. Each reaction contains 1 pmol of Cy3-ISD45 DNA. cGAS proteins were added at 2-fold increment from 1 to 32 pmol. The corresponding molar ratio of cGAS to DNA is shown at the top of the gel. The positions of DNA-cGAS condensate, the lower-order forms of DNA–cGAS complex(es), and free Cy3-ISD45 45-bp DNA are indicated on the right side of the 6% DNA retardation Gels. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

The flexible N-terminal domain of cGAS has been shown to exhibit DNA binding affinity, thereby increasing the multivalency of cGAS–DNA interactions (24, 27). To rule out the influence of the N-terminal domain to cGAS–DNA binding behavior, we tested the binding modes of Cy3-labeled ISD45 to the cGASCD using the same protocol as used for FL cGAS. Like FL h-cGAS, WT h-cGASCD preferentially forms high-order cGAS–DNA condensate on the top of the gel, while WT m-cGASCD forms both condensate and lower and less-condensed cGAS–DNA complex(es) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Similar to what was observed for FL h-cGAS samples (Fig. 4 A and B), mutations at site-C of h-cGASCD changed the DNA binding pattern, resulting in the appearance of lower molecular-weight cGASCD–DNA complex(es) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B).

Site-C Interface Promotes DNA Condensation Ability of cGAS as Monitored by a Spin-Down Assay.

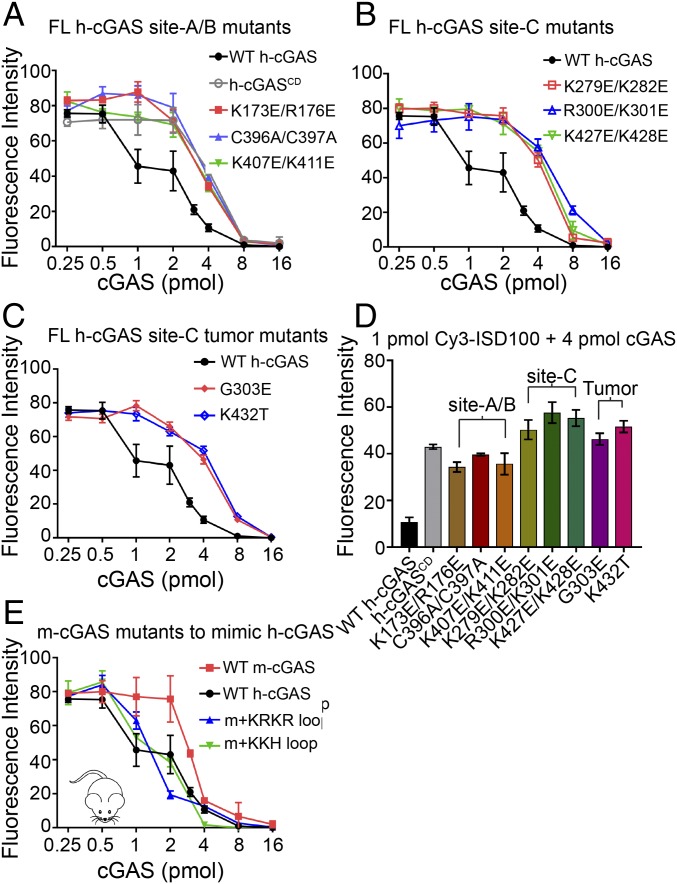

We noticed that, consistent with EMSA results, native h-cGAS mixed with ISD100 quickly became milky. Thus, we could use a spin-down assay (34) to test whether the site-C interface could promote the formation of cGAS–DNA condensate in solution. The 1-pmol Cy3-labeled ISD100 was mixed with 0.25- to 16-pmol cGAS proteins with 2-fold increase in physiological buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl). After 1-h incubation at room temperature, we used centrifugation to remove the cGAS–DNA condensation particles and tested the free Cy3-ISD100 concentration (by monitoring Cy3 fluorescence intensity) remaining in the supernatant (schematic in SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). We prepared native FL h-cGAS, h-cGASCD, multiple FL h-cGAS mutants of site-A/B (K173E/R176E, C396A/C397A, and K407E/K411E) and site-C (K279E/K282E, R300E/K301E, and K427E/K428E). As shown in Fig. 5 A and B, the Cy3 fluorescence intensities in solution following spin down for all samples containing the h-cGASCD or FL h-cGAS mutants were significantly higher than FL h-cGAS sample, implying the N-terminal domain and the three interfaces of h-cGAS all contribute to the DNA condensation ability of h-cGAS. A similar pattern of results was observed when testing the two FL h-cGAS site-C tumor-associated mutants (Fig. 5C). We then compared the contributions of different DNA binding sites of h-cGAS to DNA condensation ability using the samples containing 1-pmol Cy3-ISD100 and 4-pmol cGAS proteins. The samples containing mutations on site-C interface (including tumor-associated mutations) showed higher Cy3 fluorescence intensities in the supernatant than the h-cGASCD or site-A/B mutants samples, supporting the essential role of the site-C interface in promoting cGAS–DNA condensation (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

The site-C interface promotes the DNA condensation ability of cGAS as monitored by a spin-down assay. (A–C) DNA condensation assays of Cy3-ISD100 with FL WT and mutant h-cGAS proteins. Twofold increasing concentrations of h-cGAS proteins (from 0.25 to 16 pmol) were mixed with 1 pmol of ISD100 for 1 h at room temperature. After centrifugation to remove the cGAS–DNA condensate, the fluorescence intensity values of Cy3 in the supernatant were plotted against cGAS protein concentrations. (D) Quantification of 4-pmol h-cGAS proteins to 1-pmol DNA condensation experiments in A, B, and C. (E) FL m-cGAS mutants to mimic h-cGAS show enhanced DNA condensation ability.

We also tested the DNA condensation abilities of Cy3-labeled ISD100 on binding to the cGASCD, using the same protocol as used for FL cGAS. The Cy3 fluorescence intensities in solution for all samples containing h-cGASCD site-C mutants were significantly higher than WT h-cGASCD (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B), similar to what was observed for these site-C mutants in FL h-cGAS samples (Fig. 5 B and C).

Consistent with EMSA data, mouse cGAS samples showed higher concentrations of Cy3-ISD100 remaining in solution compared with the FL WT h-cGAS samples (Fig. 5E), indicating m-cGAS has a weaker DNA condensation ability than h-cGAS. We predicted that mutations of m-cGAS that strengthen the site-C interface would be gain-of-function mutations in cGAS–DNA condensation. We then introduced the h-cGAS site-C KRKR-loop and KKH-loop to replace the corresponding regions of native m-cGAS, resulting in two chimera proteins, m-cGAS+KRKR-loop [E285K/E287K] and m-cGAS+KKH loop [replacing m-QE (413–414) with h-KDKKH (425–429)]. As shown in Fig. 5E, both chimera proteins showed significantly enhanced DNA condensation abilities compared with native m-cGAS. These results support our hypotheses that, despite evolutionary conservation of domain architectures among mammalian cGAS sensors, the evolutionarily strengthened site-C interface of cGAS promotes cGAS–DNA condensation.

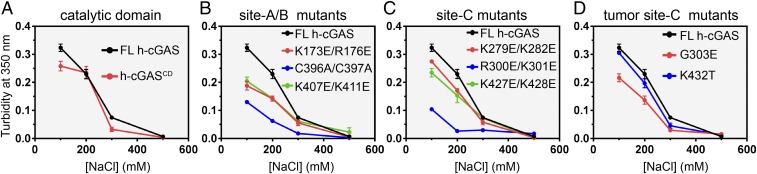

Higher Valency of cGAS Associated with Site-C Interface Identified from Quantitative Turbidity.

To further evaluate the contribution of site-C intermolecular contacts in FL h-cGAS–DNA to liquid-phase condensation, we performed turbidity assays (35, 36) by incubating purified 10 µM FL WT and mutant h-cGAS proteins with 10 µM ISD100 in the buffer containing different NaCl concentrations. The h-cGAS–DNA turbidity measurements monitoring liquid-phase condensation showed a salt-dependent trend, reflecting contributions from protein–DNA electrostatic interactions (Fig. 6A). N-terminally truncated h-cGASCD (Fig. 6A), FL h-cGAS site-A/B disrupting mutants (Fig. 6B), site-C disrupting mutants (Fig. 6C), and site-C tumor-associated mutants (Fig. 6D) all showed reduced propensity to phase condensate formation as measured by turbidity formation. Among all samples, site-C disrupting mutant (R300E/K301E) (Fig. 6C) and Zn-thumb disrupting mutant (C396A/C397A) (Fig. 6B) of cGAS exhibited the most reduced turbidity, supporting the role of site-C cGAS–DNA and Zn-ion-coordination contacts to promote cGAS–DNA liquid-phase condensation.

Fig. 6.

The site-C interface promotes the liquid-phase condensation ability of cGAS as monitored by turbidity. Quantitative turbidity graphs data on (A) FL h-cGAS and h-cGASCD, (B) site-A/B mutants of FL h-cGAS, (C) site-C mutants of FL h-cGAS, and (D) site-C tumor mutants of FL h-cGAS. Data are represented as means ± SD of three independent experiments.

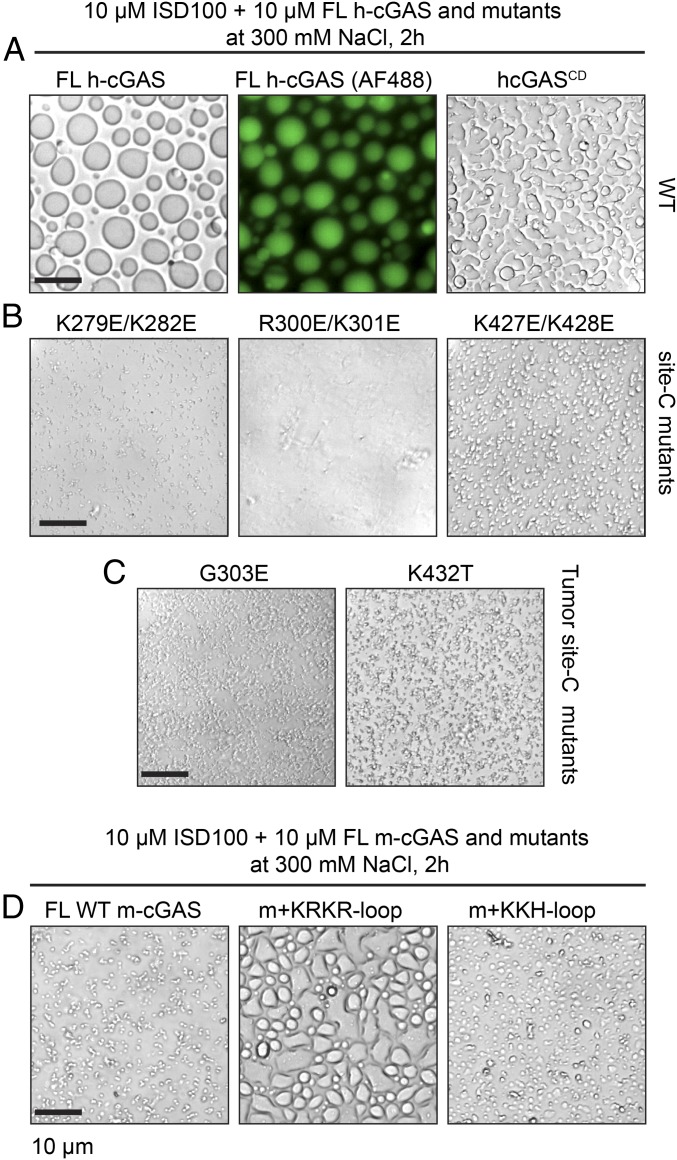

Higher Valency of cGAS Associated with Site-C Interface Identified from Time-Lapse Imaging of Liquid Droplet Formation.

A recent study established that DNA-induced liquid-phase condensation of cGAS activates innate immune signaling (24). The emphasis of this study was on the basic N-terminal domain of cGAS and the contribution of its multivalent interactions with DNA to liquid-phase condensation. Our research complements these studies but with a focus on the existence of the site-C interface and its additional contribution toward a significant increase in the multivalency of cGAS–DNA interactions (37, 38). We have tested the above concept that site-C cGAS–DNA intermolecular contacts are essential for cGAS–DNA liquid-phase condensation by time-lapse imaging of liquid droplet formation.

Time-lapse imaging of liquid droplet formation was performed by incubating purified 10 µM cGAS proteins with 10 µM ISD100 in a buffer containing 300 mM NaCl as previously reported (24). Upon mixing, WT h-cGAS and ISD100 formed micrometer-sized liquid droplets, which gradually fused into larger ones (left and central panels of Fig. 7A and SI Appendix, Fig. S7A), consistent with the previous study (24). N-terminally truncated h-cGASCD exhibited a mixture of a few liquid droplets and leopard-print–like structures (Fig. 7 A, Right), implying h-cGASCD exhibits weaker liquid-phase condensation than FL WT h-cGAS. Furthermore, FL h-cGAS site-A/B disrupting mutant samples showed more numerous but smaller liquid droplets (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B) under the same conditions as recorded for FL WT h-cGAS (Fig. 7 A, Left). Among all samples, FL h-cGAS site-C disrupting mutants exhibited the most reduced liquid droplet formation (Fig. 7B). In particular, FL h-cGAS site-C R300E/K301E mutant only showed a few pellets and failed to form any liquid droplets (Fig. 7 B, central panel). We also tested the liquid droplet formation of FL h-cGAS site-C tumor-associated G303E and K432T mutants, which also showed weaker liquid-phase condensation (Fig. 7C) than their FL WT h-cGAS counterpart (Fig. 7 A, Left).

Fig. 7.

Site-C DNA binding surface of cGAS is essential for DNA-induced liquid-phase condensation as identified from time-lapse imaging of liquid droplet formation. (A) Bright-field and GFP imaging of liquid droplet formation for FL h-cGAS and h-cGASCD complexes. (B) Bright-field imaging of liquid droplet formation for FL site-C h-cGAS K279E/K282E, R300E/K301E, and K427E/K428E mutant complexes. (C) Bright-field imaging of liquid droplet formation for FL site-C h-cGAS G303E and K432T tumor mutant complexes. (D) Bright-field imaging of liquid droplet formation for WT FL m-cGAS and swaps containing the human-specific KRKR loop and human KKH loop inserted into m-cGAS. The images shown are representative of all fields in the well. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. FL h-cGAS mutants are indicated on the top of the panels. (Scale bar, 10 µm.)

The smaller site-C interface area of m-cGAS suggested that m-cGAS should have weaker phase condensation than h-cGAS. As expected, the FL WT m-cGAS sample only exhibited a mixture of small liquid droplets and branch-like structures (Fig. 7 D, Left) under the same condition in which sizeable liquid droplets could be formed by WT FL h-cGAS sample (Fig. 7 A, Left). By contrast, we observed significant enhancement of liquid droplet formation for chimera m-cGAS+KRKR-loop (swapping of KRKR-loop of mouse for human) (Fig. 7 D, central panel), and less enhancement for chimera m-cGAS+KKH loop (swapping of KKH-loop of mouse for human) (Fig. 7 D, Right).

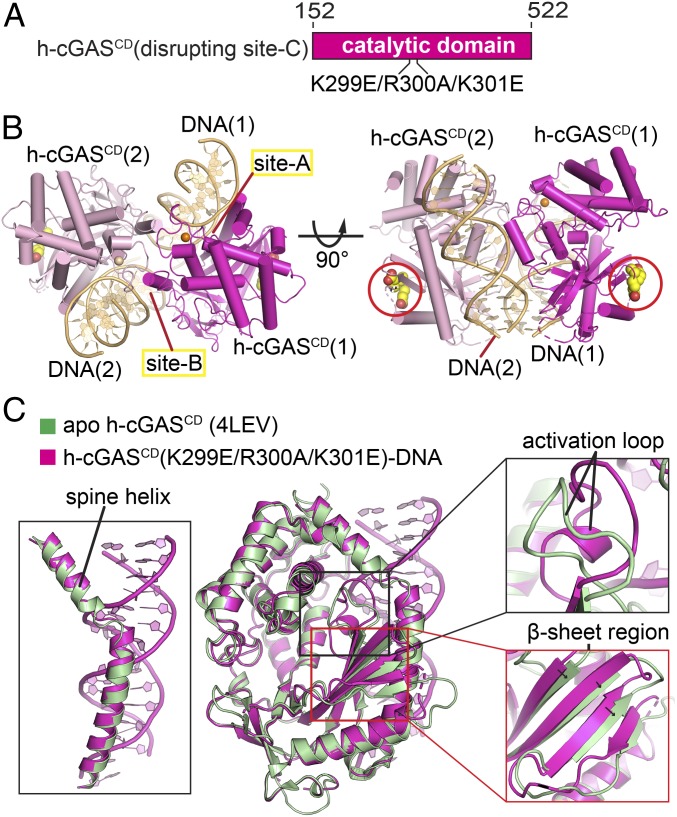

Disrupting Site-C Interface Represents a Strategy for Crystallization of h-cGASCD–DNA Complex.

An important and challenging current goal has been to discover specific inhibitors of h-cGAS, given their potential as valuable therapeutics (39–43). Such structure-guided rational drug design approaches have been undertaken to date on the apo h-cGASCD (44, 45) and the m-cGASCD–DNA complexes (25), but have been hindered until recently (20), by the absence of a structure of the DNA-bound h-cGASCD complex. The discovery of site-C interface made it likely that reducing the number of protein–DNA interfaces could represent an approach toward successful crystallization of a h-cGASCD–DNA complex. Thus, we rationalized that insertion of a minimum set of mutations that disrupt the site-C interface had the potential for generating diffraction-quality crystals of the complex. To this end, we designed h-cGASCD containing a triple mutant (K299E/R300A/K301E) in the KRKR-loop (designated mutant h-cGASCD) (Fig. 8A) and successively obtained crystals of mutant h-cGASCD bound to 16-bp DNA (with 1-nt overhang) that diffracted to 2.7-Å resolution. The crystals belong to P6122 space group with each asymmetric unit containing one mutant h-cGASCD bound to one DNA and forming a dimeric mutant h-cGASCD–DNA complex with its partner in the adjacent asymmetric unit (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Crystal structure of h-cGASCD (K299E/R300A/K301E) bound to DNA and comparison with apo h-cGASCD structure. (A) Schematic showing positioning of K299E/R300A/K301E triple mutant within h-cGASCD. (B) Side and top views of dimeric structure of h-cGASCD (K299E/R300A/K301E) bound to 16-bp DNA (containing 1-nt overhang). h-cGASCD monomers are colored in magenta and pink, while the pair of bound DNAs are colored in teal, with labeling of sites-A and site-B. The triple mutation sites are shown in a space-filling representation and indicated by red circles. (C) Superposed structures of apo h-cGASCD (PDB ID code 4LEV; in green) and DNA-bound h-cGASCD (K299E/R300A/K301E) (this study; in magenta). The structures of the two complexes exhibit an rmsd of 0.637 Å. The blow-up views compare conformational changes of the α-helix spine (Left), activation loop (Upper Right), and β-sheet segments (Lower Right). The black arrows indicate the small shift in β-strands on proceeding from apo- to DNA-bound states for m-cGASCD.

Recently, a crystal structure was reported for a dimeric h-cGASCD–DNA complex containing a dual K187N/L195R mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A) on the long spine helix within the site-A interface of the dimeric h-cGAS (PDB ID code 6CT9) (20) (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B), thereby representing an alternate solution to the same problem. Notably, the two structures of these distinct dimeric mutant h-cGASCD–DNA complexes superpose well with an rmsd of 0.286 Å (SI Appendix, Fig. S8C).

Comparison of Conformational Transitions in Mouse and Human apo-cGASCD on DNA Complex Formation.

Previous structural studies had shown the m-cGASCD exhibited large conformational changes in the spine helix and a β-sheet segment, in addition to the activation loop, on proceeding from the apo-state (in cyan) to the DNA-bound state (in red) as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S9. By contrast, the conformational changes are restricted to the activation loop on proceeding from the apo-state (in green) to the DNA-bound state (in magenta) of h-cGASCD as shown in Fig. 8C. The less pronounced global structural changes for h-cGAS on proceeding from the apo- to DNA-bound state has allowed studies of inhibitor binding to be undertaken on apo h-cGAS (44–46).

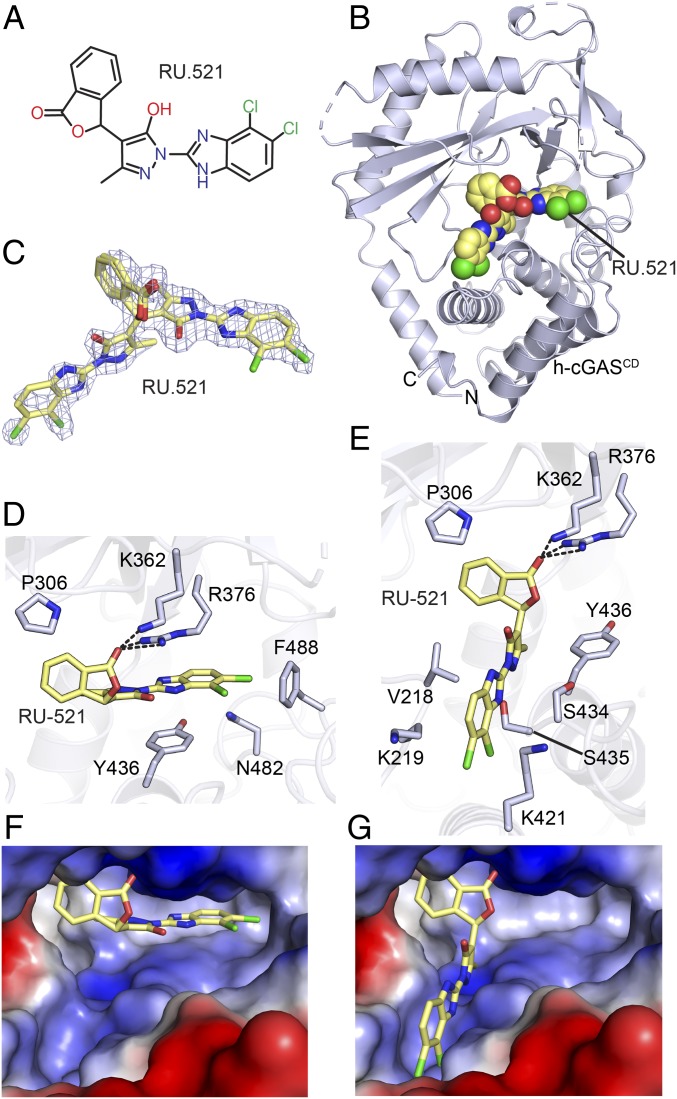

Positioning of Inhibitor RU.521 in Two Orientations in the Catalytic Pocket of Apo h-cGASCD (K427E/K428E).

We found that another dual mutant (K427E/K428E) disrupting the site-C interface significantly improved the crystallization of apo h-cGASCD, potentially serving as a future platform for characterizing inhibitor development at the DNA-free h-cGAS level. Our group previously reported on the crystal structure of RU.521 (Fig. 9A) bound to the m-cGASCD–DNA complex (25). We have now extended these studies to the human system by attempting to crystallize RU.521 with both apo h-cGASCD(K427E/K428E) and h-cGASCD(K299E/R300A/K301E)–DNA complex and were successful in obtaining diffraction-quality crystals of the former complex. The structure of RU.521 bound to apo h-cGASCD at 2.2-Å resolution is shown in Fig. 9B (X-ray statistics listed in SI Appendix, Table S1), with RU.521 bound in two orientations in the catalytic pocket (Fig. 9C). In one orientation, the planar benzimidazole-pyrazole ring system of bound RU.521 is intercalated between the side chains of Arg376 and Tyr436, while the carbonyl of the phthalide ring hydrogen bonds with the side chains of both Arg376 and K362 (Fig. 9D). In a second orientation, the planar benzimidazole-pyrazole ring system of bound RU.521 is directed downward and positioned in a channel, while the carbonyl of the phthalide ring hydrogen bonds with the side chains of both Arg376 and K362 (Fig. 9E). In both orientations, the benzimidazole-pyrazole rings are snugly anchored in place (Fig. 9 F and G). Given that RU.521 binds in two orientations, it occupies a larger segment of the catalytic pocket of apo-h-cGASCD.

Fig. 9.

Structure of RU.521 bound to apo h-cGASCD. (A) Chemical formula of RU.521. (B) Crystal structure of RU.521 bound to apo h-cGASCD(K427E/K428E). The bound RU.521 positioned in the catalytic pocket in two orientations is shown in a space-filling representation. (C) 2Fo-Fc electron density map of RU.521 bound in two orientations contoured at 1.2σ level. (D and E) Pairing alignments of bound RU.521 in one orientation where the planar benzimidazole-pyrazole rings are intercalated between the side chains of Arg-376 and Tyr-436 (D) and a second orientation where the planar benzimidazole-pyrazole rings is positioned in a channel at the bottom of the catalytic pocket (E). (F and G) Pairing alignments of bound RU.521 in two orientations in the catalytic pocket of apo h-cGASCD, with the protein shown in an electrostatic representation and RU.521 colored in yellow stick representation. Electrostatic surface potentials were calculated in PyMol and contoured at ±100.

Discussion

Identification and Perturbation of Additional Site-C Interface and Its Impact on h-cGAS–DNA Phase Condensation.

In an earlier study, it was shown that the basic and unstructured N terminus of cGAS contributed to DNA-induced liquid-phase condensation and activation of innate immune signaling (24). In this study, we have expanded on this observation by structural studies that identified an additional site-C cGAS–DNA interface (Fig. 1E) that also contributes to liquid-phase condensation. This site-C cGAS interface is very basic in human (Fig. 2 A, Right) and less so in mouse (Fig. 2C), with mutations (including tumor mutations) spanning the site-C interface disrupting phase condensation as monitored by cGAMP formation assays (Fig. 3B), gel shifts reflecting complex and condensate formation (Fig. 4), spin-down (Fig. 5), and turbidity (Fig. 6) assays, and most importantly, time-lapse imaging of liquid droplet formation (Fig. 7).

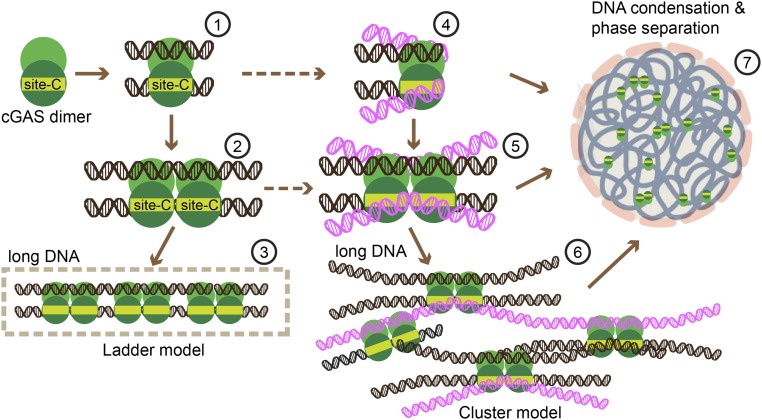

Cluster Model Contributing to h-cGAS–DNA Liquid-Phase Condensation.

The earliest structures of m-cGASCD bound to short DNA duplexes identified complexes composed of a pair of proteins bound to a pair of DNAs (schematic labeled 1 in Fig. 10) (21). A recent crystallographic effort that extended these studies to longer 39-bp DNAs established formation of a m-cGASCD–DNA structure composed of a pair of protein dimers bound at adjacent sites to a pair of DNAs (schematic labeled 2 in Fig. 8, with the X-ray structure shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S10A, Left) (17). This study highlighted the concept of cooperative binding of m-cGASCD dimers at adjacent sites to a pair of DNA duplexes generating a ladder model of higher-order complex formation (schematic labeled 3 in Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Proposed cluster model of long DNA sensed by h-cGAS. Apo cGAS proteins can exist as dimers in solution, capable of forming a dimeric cGAS–DNA complex composed of a pair of cGAS dimers bound to a pair of DNAs (structure labeled 1). Binding of an additional pair of cGAS dimers results in formation of structure labeled 2 (PDB ID code 5N6I), eventually resulting in the formation of a ladder-like model of complex formation with longer DNA (schematic labeled 3). The availability of site-C interfaces results in increased multivalency generating the proposed cluster model shown in schematics labeled 4, 5, and 6, reflecting formation of higher-order DNA complexes contributing to DNA binding affinity. Such a net-like structure shown in schematic labeled 7 can contribute to DNA condensation and phase separation.

In our case, we propose an extension of the ladder model to a cluster model based on the participation of site-C protein–DNA interface in multivalent interactions. Thus, in a stepwise manner, one generates a h-cGAS–DNA complex involving a pair of cGAS dimers bound to a pair of short DNAs (schematic labeled 4 in Fig. 10), which can be extended to cGAS dimers binding at adjacent sites on a pair of longer DNAs (schematic labeled 5 in Fig. 10 and modeled in SI Appendix, Fig. S10B, Left), which due to the additional site-C interface can result in formation of a cluster model (schematic labeled 6 in Fig. 10). Notably, the two adjacent site-C interfaces can form one extended basic surface with the total area of 1,325 Å2 as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S10B, Right (with the corresponding surface for m-cGAS–DNA complex shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S10A, Right), even larger than the total area of sites A+B (1,009 Å2), suggestive of a strong binding potential at site-C for DNA. Two adjacent DNAs bound along site-C can be aligned to mimic a slightly bent long DNA (schematic labeled 5 in Fig. 10 and SI Appendix, Fig. S10B, Left). The existence of the site-C interface significantly increases the multivalency of cGAS interactions with DNA (schematic labeled 6, Fig. 10). The increased valency suggested to us that the structure of h-cGAS bound to long DNA could result in the onset of DNA condensation (schematic labeled 7, Fig. 10), consistent with the ability of DNA-bound cGAS to form puncta in the cytoplasm (1, 13, 24, 47–49).

The proposed multivalency concept represents an approach for sensitive detection of long DNA by cGAS, since longer DNA has the potential for higher valency protein–DNA interactions to further promote phase condensation. Previous demonstration of the role of the N-terminal unstructured basic domain in DNA-induced phase condensation of cGAS (24) and our identification of an additional h-cGAS–DNA binding interface in support of the cluster model (schematic labeled 6, Fig. 10), together provide a molecular explanation for the role of DNA-induced cGAS phase condensation in promoting cGAMP production and activation of innate immune signaling.

Structure Determination of a Dimeric h-cGAS–DNA Complex Should Facilitate Development of Inhibitors Targeting the h-cGAS Scaffold.

Two different strategies have been used to generate, crystallize, and solve structures of h-cGASCD–DNA complexes as a step toward design and development of inhibitors that therapeutically target the DNA-bound cGAS catalytic pocket in humans as an approach to design and optimize inhibitors toward the treatment of cGAS-STING pathway-mediated autoimmune diseases (41). This goal has been achieved by either mutating (K187N/L195R) the site-A interface (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B) (20) or mutating (K299E/R300A/K301E) the site-C interface (Fig. 8) (this study), with structures of both complexes superposing well on each other (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B). We note that crystals of the dimeric h-cGASCD(K187N/L195R)–DNA complex were grown under high salt crystallization conditions (1.4 M Na-citrate), which could potentially impede protein–DNA electrostatic interactions so that the site-C interface was not observed in this crystal structure of the complex (20). By contrast, crystals of dimeric h-cGASCD(K299E/R300A/K301E)–DNA complex in this study were grown under a low salt condition (0.2 M NaCl), potentially facilitating structure-guided drug development, since low salt conditions may help to increase solubility and prevent disruption of polar interactions involving bound activators/inhibitors of the cGAS–STING pathway.

The availability of crystal structures of both apo mutant h-cGASCD and mutant h-cGASCD–DNA complexes (ref. 20 and our study) open opportunities for structure-guided testing of small-molecule inhibitors of cGAMP production, as therapeutic agents against autoimmune diseases. Notably, conformational changes are restricted to the catalytic pocket following comparison of structures of apo- and DNA-bound h-cGASCD (Fig. 8C), allowing both apo h-cGASCD and h-cGASCD–DNA to be used as scaffolds for inhibitor development. To date, crystal structures are only available for inhibitors bound to apo h-cGASCD (44, 45), with the structure of the complex of RU.521 bound to h-cGASCD (Fig. 9) reported in this paper added to this list.

The rectangular-shaped pocket of cGAS is quite large, with bound cGAMP (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A) and other ligands occupying one end of the binding pocket. In addition, cGAMP binding is stabilized by three factors: intercalation of the adenine ring between Arg and Tyr side chains, hydrogen bonding between the Watson–Crick edge of the guanine and a pocket Arg side chain, and between the 2-NH2 group of guanine and a pair of catalytic Asp side chains (SI Appendix, Fig. S11B). Our study shows a single stereoisomer of the ligand RU.521 was bound in two orientations to the catalytic pocket of apo h-cGAS (Fig. 9C). In one alignment, the interaction and hydrogen bonding to Arg side chain requirements are met (Fig. 9D), while in the other alignment only the hydrogen bonding to Arg side chain requirement is met (Fig. 9E). Nevertheless, by binding in two orientations, the single RU.521 stereoisomer occupies more of the binding pocket. The biochemical in vitro IC50 values for RU.521 binding to m-cGAS (0.11 µM) (25) using a RapidFire assay are on the low side, as is the cellular IC50 value for m-cGAS (0.70 µM) using a mouse RAW-Lucia macrophage cells (25). Further improvement toward optimization of RU.521 efficacy could be facilitated by positioning polar functional groups on the phthalide ring of RU.521 in efforts to introduce hydrogen-bonding potential to target the catalytic Asp residues toward meeting all three recognition requirements. Alternately, a molecule that mimics both orientations of bound RU.521 would occupy a larger proportion of the binding pocket, thereby potentially enhancing binding affinity.

Materials and Methods

Details of the materials and methods including protein expression and purification, crystallization, structure determination, RapidFire-MS, EMSA, DNA condensation, and turbidity assays, as well as time-lapse imaging of liquid droplet formation measurements are presented in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the synchrotron beamline staff at the Argonne National Laboratory for their assistance. We thank the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Molecular Cytology Facility for technical support in time-lapse imaging. We gratefully acknowledge the support generously provided by the Tri-Institutional Therapeutics Discovery Institute (TDI), a 501(c)(3) organization, to the project (not to the non-TDI labs). TDI receives financial support from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, TDI’s parent institutes (MSKCC, The Rockefeller University, and Weill Cornell Medicine), and from a generous contribution from Mr. Lewis Sanders and other philanthropic sources. This work was also supported, in part, by the following agencies: William H. Goodwin and Alice Goodwin from the Commonwealth Foundation for Research and from the Center for Experimental Therapeutics of the MSKCC (D.J.P.), GM104962 and CA179564 (T.T. and D.J.P.), and MSKCC Core Grant P30 CA008748. The crystallographic research was conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines, which are funded by National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41 GM103403) and US Department of Energy (DE-AC02-06CH11357). The RF-MS instrument was purchased with funds from the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.wwpdb.org (PDB ID codes 6EDB for SRY.h-cGASCD–DNA, 6EDC for h-cGASCD–DNA, and 6O47 for h-cGASCD-RU.521).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1905013116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sun L., Wu J., Du F., Chen X., Chen Z. J., Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 339, 786–791 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li X.-D., et al. , Pivotal roles of cGAS-cGAMP signaling in antiviral defense and immune adjuvant effects. Science 341, 1390–1394 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu J., et al. , Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science 339, 826–830 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ablasser A., et al. , cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature 498, 380–384 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao P., et al. , Cyclic [G(2′,5′)pA(3′,5′)p] is the metazoan second messenger produced by DNA-activated cyclic GMP-AMP synthase. Cell 153, 1094–1107 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kranzusch P. J., Lee A. S., Berger J. M., Doudna J. A., Structure of human cGAS reveals a conserved family of second-messenger enzymes in innate immunity. Cell Rep. 3, 1362–1368 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato K., et al. , Structural and functional analyses of DNA-sensing and immune activation by human cGAS. PLoS One 8, e76983 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu X., et al. , Molecular evolutionary and structural analysis of the cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS and STING. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 8243–8257 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao P., et al. , Structure-function analysis of STING activation by c[G(2′,5′)pA(3′,5′)p] and targeting by antiviral DMXAA. Cell 154, 748–762 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barber G. N., STING: Infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 760–770 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diner E. J. J., et al. , The innate immune DNA sensor cGAS produces a noncanonical cyclic dinucleotide that activates human STING. Cell Rep. 3, 1355–1361 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao D., et al. , Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune sensor of HIV and other retroviruses. Science 341, 903–906 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wassermann R., et al. , Mycobacterium tuberculosis differentially activates cGAS- and inflammasome-dependent intracellular immune responses through ESX-1. Cell Host Microbe 17, 799–810 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luecke S., et al. , cGAS is activated by DNA in a length-dependent manner. EMBO Rep. 18, 1707–1715 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoggins J. W., et al. , Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature 505, 691–695 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang C., et al. , Manganese increases the sensitivity of the cGAS-STING pathway for double-stranded DNA and is required for the host defense against DNA viruses. Immunity 48, 675–687.e7 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreeva L., et al. , cGAS senses long and HMGB/TFAM-bound U-turn DNA by forming protein-DNA ladders. Nature 549, 394–398 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J., Chen Z. J., Innate immune sensing and signaling of cytosolic nucleic acids. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32, 461–488 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Q., Sun L., Chen Z. J., Regulation and function of the cGAS-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nat. Immunol. 17, 1142–1149 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou W., et al. , Structure of the human cGAS-DNA complex reveals enhanced control of immune surveillance. Cell 174, 300–311.e11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X., et al. , Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is activated by double-stranded DNA-induced oligomerization. Immunity 39, 1019–1031 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Civril F., et al. , Structural mechanism of cytosolic DNA sensing by cGAS. Nature 498, 332–337 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin Q., Fu T.-M., Li J., Wu H., Structural biology of innate immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 33, 393–416 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du M., Chen Z. J., DNA-induced liquid phase condensation of cGAS activates innate immune signaling. Science 361, 704–709 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vincent J., et al. , Small molecule inhibition of cGAS reduces interferon expression in primary macrophages from autoimmune mice. Nat. Commun. 8, 750 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrone S. R., et al. , Assembly-driven activation of the AIM2 foreign-dsDNA sensor provides a polymerization template for downstream ASC. Nat. Commun. 6, 7827 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao J., et al. , Nonspecific DNA binding of cGAS N terminus promotes cGAS activation. J. Immunol. 198, 3627–3636 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnett K. C., et al. , Phosphoinositide interactions position cGAS at the plasma membrane to ensure efficient distinction between self- and viral DNA. Cell 176, 1432–1446.e11 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stott K., Tang G. S. F., Lee K. B., Thomas J. O., Structure of a complex of tandem HMG boxes and DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 360, 90–104 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X., et al. , The cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS forms an oligomeric complex with DNA and undergoes switch-like conformational changes in the activation loop. Cell Rep. 6, 421–430 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robert X., Gouet P., Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hancks D. C., Hartley M. K., Hagan C., Clark N. L., Elde N. C., Overlapping patterns of rapid evolution in the nucleic acid sensors cGAS and OAS1 suggest a common mechanism of pathogen antagonism and escape. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005203 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerami E., et al. , The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2, 401–404 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larson A. G., et al. , Liquid droplet formation by HP1α suggests a role for phase separation in heterochromatin. Nature 547, 236–240 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang A., et al. , A single N-terminal phosphomimic disrupts TDP-43 polymerization, phase separation, and RNA splicing. EMBO J. 37, 1–18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schuster B. S., et al. , Controllable protein phase separation and modular recruitment to form responsive membraneless organelles. Nat. Commun. 9, 2985 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li P., et al. , Phase transitions in the assembly of multivalent signalling proteins. Nature 483, 336–340 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H., et al. , Rubisco condensate formation by CcmM in β-carboxysome biogenesis. Nature 566, 131–135 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.An J., Woodward J. J., Sasaki T., Minie M., Elkon K. B., Cutting edge: Antimalarial drugs inhibit IFN-β production through blockade of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-DNA interaction. J. Immunol. 194, 4089–4093 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H., et al. , cGAS is essential for the antitumor effect of immune checkpoint blockade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 1637–1642 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao D., et al. , Activation of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase by self-DNA causes autoimmune diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E5699–E5705 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yum S., Li M., Frankel A. E., Chen Z. J., Roles of the cGAS-STING pathway in cancer immunosurveillance and immunotherapy. Annu Rev Cancer Biol 3, 323–344 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dai J., et al. , Acetylation blocks cGAS activity and inhibits self-DNA-induced autoimmunity. Cell 176, 1447–1460.e14 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hall J., et al. , Discovery of PF-06928215 as a high affinity inhibitor of cGAS enabled by a novel fluorescence polarization assay. PLoS One 12, e0184843 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lodoe L., et al. , Development of human cGAS-specific small-molecule inhibitors for repression of dsDNA-triggered interferon expression. Nat. Commun. 10, 2261 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall J., et al. , The catalytic mechanism of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) and implications for innate immunity and inhibition. Protein Sci. 26, 2367–2380 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mackenzie K. J., et al. , cGAS surveillance of micronuclei links genome instability to innate immunity. Nature 548, 461–465 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Collins A. C., et al. , Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune DNA sensor for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Host Microbe 17, 820–828 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang Q., et al. , Crosstalk between the cGAS DNA sensor and Beclin-1 autophagy protein shapes innate antimicrobial immune responses. Cell Host Microbe 15, 228–238 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.