Significance

A multicomponent molecular machine, called the replisome, mediates high fidelity genome duplication but requires error-free DNA as its template. The presence of lesions on DNA, like those generated after UV, halt replisome activity and can lead to replisome disassembly, a potentially life-threatening situation to the cell. Here, we show that, in cells exposed to UV, parts of the replisome independently localize at sites far from the place of DNA synthesis. In addition, we provide evidence that the replisome responds to UV by slowing down its rate of synthesis on the damaged DNA template. Modulation of the rate of DNA replication may be a general strategy used by other organisms to minimize the impact of DNA damage on the duplicating genome.

Keywords: DNA replication, replisome, fluorescence microscopy, UV, Escherichia coli

Abstract

The replisome is a multiprotein machine that is responsible for replicating DNA. During active DNA synthesis, the replisome tightly associates with DNA. In contrast, after DNA damage, the replisome may disassemble, exposing DNA to breaks and threatening cell survival. Using live cell imaging, we studied the effect of UV light on the replisome of Escherichia coli. Surprisingly, our results showed an increase in Pol III holoenzyme (Pol III HE) foci post-UV that do not colocalize with the DnaB helicase. Formation of these foci is independent of active replication forks and dependent on the presence of the χ subunit of the clamp loader, suggesting recruitment of Pol III HE at sites of DNA repair. Our results also showed a decrease of DnaB helicase foci per cell after UV, consistent with the disassembly of a fraction of the replisomes. By labeling newly synthesized DNA, we demonstrated that a drop in the rate of synthesis is not explained by replisome disassembly alone. Instead, we show that most replisomes continue synthesizing DNA at a slower rate after UV. We propose that the slowdown in replisome activity is a strategy to prevent clashes with engaged DNA repair proteins and preserve the integrity of the replication fork.

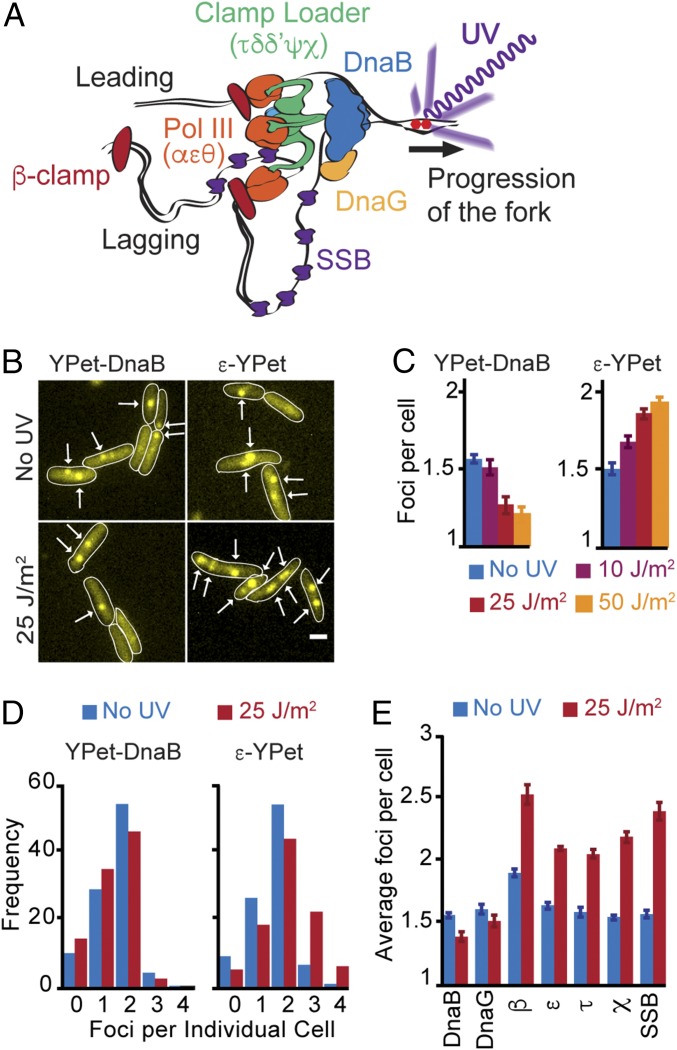

DNA replication is carried out by a multiprotein machine called the replisome. In Escherichia coli, the replisome is composed of the DnaB helicase, the DnaG primase, the DNA Pol III (αεθ), the processivity factor β clamp (β2), the clamp loader (τ3δδ′ψχ), and the single strand binding protein SSB (Fig. 1A) (1, 2). Multiple protein–protein interactions exist among these subcomplexes. DnaB and DnaG interact with each other (3, 4). Pol III and clamp loader are physically coupled by the interaction between α and τ, forming the Pol III* subcomplex (5). Pol III* and β clamp form the Pol III holoenzyme (Pol III HE) (6). Finally, the τ subunit mediates the interaction between DnaB helicase and Pol III HE (7). Once in every cell cycle, DNA replication is initiated with the assembly of two replisomes in opposite orientations at a specific locus of the chromosome, the oriC. Each replication fork duplicates half of the 4.6-Mbp circular chromosome at rates between 0.6 and 1 kbp⋅s−1 at 37 °C (8), completing replication as the two of them meet at the region opposite from oriC.

Fig. 1.

Unbinding of replisome subunits at a UV lesion. (A) Model of the architecture of an active replisome. DNA is unwound by the DnaB helicase. DnaG primase binds to DnaB. Pol III and the clamp loader bind each other through the τ subunit of the clamp loader, which also mediates binding to the DnaB helicase. The β-clamp is left behind the fork after the completion of an Okazaki fragment at the lagging strand. SSB covers ssDNA produced during the cycle of lagging strand synthesis. (B) Representative images of cells carrying YPet-DnaB or ε-YPet before, and 5 min after, exposure to 25 J/m2 UV dose. White arrows mark the location of foci. (Scale bar: 1 μm.) (C) Average number of the foci per cell of YPet-DnaB or ε-YPet 5 min after exposure to different UV doses. (D) Distribution of the number of foci per cell in cells carrying YPet-DnaB or ε-YPet 5 min after exposure to UV. (E) Average number of foci for all of the replisome subunits tested: YPet-DnaB, YPet-DnaG, YPet-β, ε-YPet, τ-YPet, χ-YPet, and SSB-YPet. Pictures were taken 5 min after exposure. Error bars represent SE.

Successful genome duplication is dependent on undamaged template DNA. Modifications in the chemistry of DNA and the presence of strand discontinuities can inhibit the progression of the replisome or lead to its disassembly, potentially generating double strand DNA (dsDNA) breaks and life-threatening consequences to the cell (9). Specialized DNA repair systems continually act on lesions to restore DNA (10–12). Prolonged replisome stalling and replisome disassembly trigger the activation of specialized mechanisms that correct dsDNA breaks and restore the replication fork—the DNA structure on which the replisome acts—followed by mechanisms to reassemble replisome at those sites (13–15). The frequency at which the replisome disassembles during normal growth and the timing required for replisome reassembly have not been well-established.

The effect of UV-C light (190 to 290 nm) on DNA and DNA replication has been widely studied. UV-C generates cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and, to a lesser extent, 6-4 pyrimidine adducts (6-4 PAs) on DNA (16). CPDs have been shown to inhibit the activity of Pol III (17) but should allow progression of the DnaB helicase as they fit through its central pore (18). Shortly after UV treatment, the rate of DNA replication significantly drops in E. coli, an effect lasting for tens of minutes (19, 20). The reduced DNA synthesis is produced in short fragments on both strands (21, 22), which was classically interpreted as the result of Pol III hopping over CPDs (21). In agreement with this model, DnaG was reported to prime both strands ahead of a lesion that blocks Pol III (23, 24), providing a mechanism by which continued progression of the DnaB helicase would mediate recruitment of Pol III HE downstream of the lesions, effectively resulting in lesion hopping. However, previous works that reported replisome stalling shortly after a lesion on the leading strand have not yet been fully reconciled with these data (25–27). In addition, different live cell studies have led to opposing conclusions on the fate of the replisome, suggesting either stable binding of the DnaB helicase or the complete disassembly of the replisome after UV (28, 29).

We used fluorescence microscopy to directly test the effect of UV on the replisome and DNA synthesis at a single-cell level. We used slow-growth conditions, with generation times above 100 min, to minimize convolution of our data by new rounds of DNA replication, as reported previously (29). Our results lead us to conclude that most replisomes remain active, although progressing at a diminished rate, after exposing cells to UV at doses where CPDs decorate DNA at every few kilobases. Our data are consistent with the capacity of the replisome to skip over lesions on DNA. In addition, we show that the Pol III HE can act independently of the DnaB helicase and the replication fork after being recruited to other sites of the chromosome in a manner dependent of the χ subunit. Pol III HE activity outside the fork may contribute to filling DNA gaps and, in conjunction with its β-clamp loading activity, may influence other processes like translesion DNA synthesis.

Results

Pol III Holoenzyme Is Recruited to Multiple Sites in the Nucleoid after Exposure to UV Light.

To test directly for replisome subunit stability after UV treatment, we used fluorescence microscopy in live cells. We studied the replisome by using previously characterized E. coli strains carrying derivatives of replisome components fused to the yellow fluorescent protein YPet (30, 31). We grew cells in conditions where they undergo a single replication event and have at most two replication forks, which translate into cells with zero, one, or two fluorescent spots for DnaB and the proof-reading exonuclease subunit of Pol III, ε (Fig. 1B) (30). Five minutes after exposing cells to UV at a dose of 25 J/m2, we observed a small decrease in the average number of YPet-DnaB foci, going from 1.57 ± 0.02 (SE) before to 1.39 ± 0.03 spots per cell after treatment (Figs. 1B and 2D). Disappearance of DnaB spots supports the idea that the replisome has disassembled in those cells. In unexpected contrast, ε-YPet showed an increase in the number of spots per cell, going from 1.64 ± 0.03 before to 2.10 ± 0.03 spots per cell after treatment. Notably, this included a significant increase in the percentage of cells with three and four spots, from 8.4 to 29.5% (Fig. 1D). The effects of UV on the distribution of DnaB and ε spots correlated with the UV dose used (Fig. 1C).

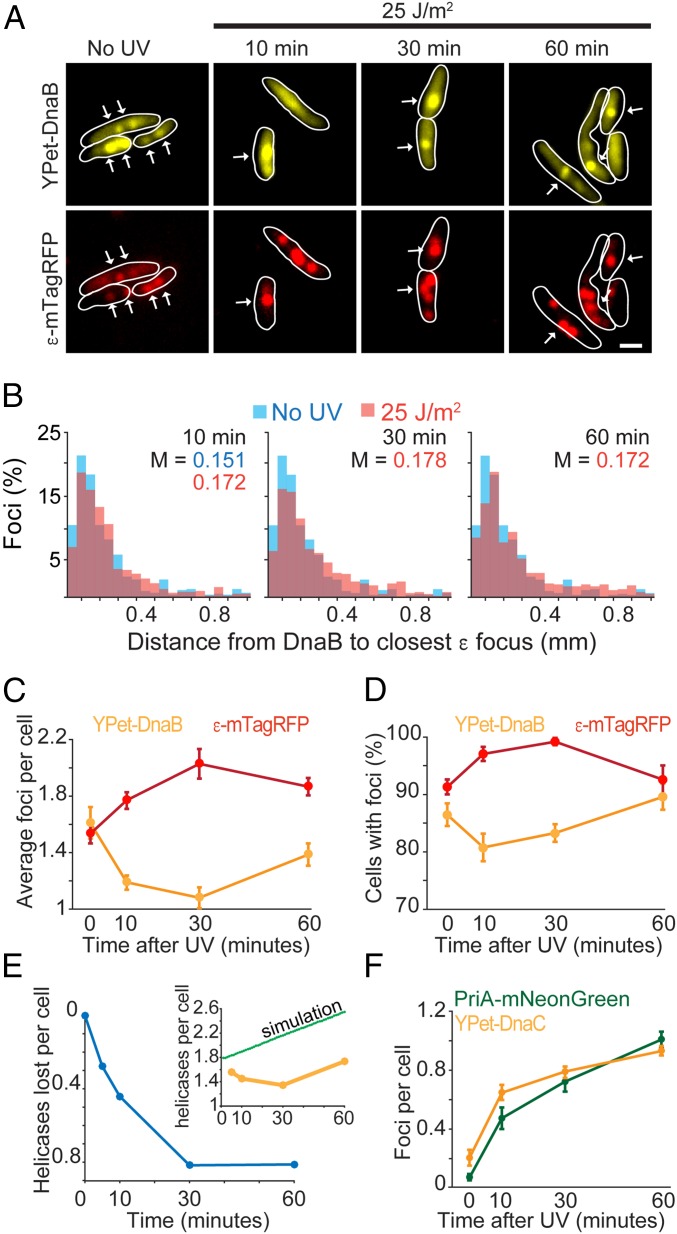

Fig. 2.

DnaB remains in proximity to Pol III after UV. (A) Representative images of a strain carrying YPet-DnaB and ε-mTagRFP before, and at various times after, UV treatment. White arrows mark colocalization of foci in the two channels. (Scale bar: 1 μm.) (B) Distribution of apparent distances between a YPet-DnaB focus and the closest ε-mTagRFP focus in a cell. The untreated sample is compared with the results at 10, 30, and 60 min after UV. The median (M) of each population is shown. (C) Average number of foci per cell for YPet-DnaB and ε-mTagRFP before (0 min) and at various times after treatment. (D) Number of cells with at least one fluorescent focus for YPet-DnaB or ε-mTagRFP at various times after treatment. (E) Estimation of helicase disassembly at various times after UV treatment. (Inset) Numbers are based on the difference between a simulated growth of foci (green line), assuming no dissasembly, and the data of YPet-DnaB from Fig. 1C and C (yellow line). (F) Number of PriA-mNeonGreen (green) and YPet-DnaC (yellow) foci per cell before (0 min) and at various times after exposure to UV. Error bars represent SE.

Further characterization of replisome subunits corroborated the existence of two different behaviors in the subcomplexes of the replisome. YPet-DnaG showed a slight reduction in the number of fluorescent spots per cell, similar to DnaB but to a lower extent, going from 1.61 ± 0.04 to 1.52 ± 0.05 before and after treatment, respectively. Whereas reminiscent of the results for ε, the number of fluorescent spots increased after UV for β-clamp from 1.9 ± 0.03 to 2.53 ± 0.08; for τ from 1.59 ± 0.04 to 2.06 ± 0.03; for χ from 1.55 ± 0.02 to 2.19 ± 0.04; and for SSB from 1.57 ± 0.03 to 2.40 ± 0.07 (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). These results match the architecture of the replisome as DnaG needs to interact with DnaB for recruitment to the replication fork, and β-clamp, clamp loader, and Pol III form the Pol III HE (Fig. 1A). In addition, our data agree with studies on the replisome dynamics where we and others showed that Pol III and the clamp loader frequently unbind from the replication fork, while the DnaB helicase is stably bound (32, 33).

To characterize the two binding regimes in the replisome, we imaged cells carrying both YPet-DnaB and ε-mTagRFP (Fig. 2). In untreated cells, we expected to observe colocalizing foci for both subunits as the replisome should contain both of them. Our results confirm this expectation: The median distance between DnaB and the closest ε spot was 0.151 µm (Fig. 2 A and F). In agreement with the results described above, the number of DnaB spots decreased and the number of ε spots increased after UV (Fig. 2 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). The greatest contrast in the spot distribution of these two subunits was reached 30 min after UV exposure, after which we observed a trend of recovery toward the pretreated state (Fig. 2 C and D). Despite the difference in abundance, the distance between DnaB and the closest ε spot did not dramatically change, having a median of 0.178 µm after 30 min. Therefore, our results suggest that all replisome subunits remain in the proximity of the replication fork after UV treatment although they may not be active—as they might be binding to gaps behind the replication fork. They also suggest the recruitment of additional copies of the Pol III HE and SSB at other sites on the chromosome, perhaps participating in DNA repair or as a result of DNA processing caused by UV lesions.

Slowdown in the Rate of DNA Synthesis Is Only Partially Explained by Replisome Disassembly.

Our initial estimates of replisome disassembly, as measured by the disappearance of YPet-DnaB foci, did not account for the elongation of cells after UV. In UV-treated cells, cell division is inhibited, but initiation of DNA replication continues (29). To obtain an accurate assessment of the frequency of replisome disassembly, we simulated the expected number of replisomes per cell in a scenario where no disassembly occurs, making the assumption that UV inhibits cell division but that the rate initiation of DNA replication remains unchanged (29), resulting in an increase in the number of replisomes per cell over time (Fig. 2E). Comparing our results with the simulated data showed that replisome disassembly continued for about 30 min, plateauing at an average of 0.8 replisomes lost per cell, when >30% of the replisomes are lost (Fig. 2E). Recovery of replisomes is not observed even after 60 min.

To complement these observations, we monitored DnaB reloading using a mNeonGreen fusion to the reloading protein PriA (Fig. 2F and SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). PriA is a crucial component of the protein complex that loads the helicase-loader DnaC-DnaB helicase in an oriC-independent manner (34). The fraction of cells with PriA spots increased after UV treatment from 7 ± 0.2% (SE), and an average of 0.067 ± 0.021 spots per cell, in untreated cells, to 78.9 ± 0.5%, and an average of 1 ± 0.05 spots per cell, 60 min after UV treatment (Fig. 2F), closely matching the estimated replisome loss. We observed a similar trend for cells carrying a YPet derivative of the helicase loader DnaC where the frequency of cells with spots increased after UV treatment from 14.20 ± 3.1% (SE), and an average of 0.19 ± 0.05 spots per cell, in untreated cells, to 61.61 ± 5%, and an average of 0.92 ± 0.03 spots per cell, 60 min after UV treatment (Fig. 2F and SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). However, these results reported a lower frequency of cells with DnaC foci compared with PriA, despite the role of DnaC in both oriC-dependent and -independent initiation. This may suggest a significant time delay between PriA binding and DnaC recruitment during reloading of the replisome.

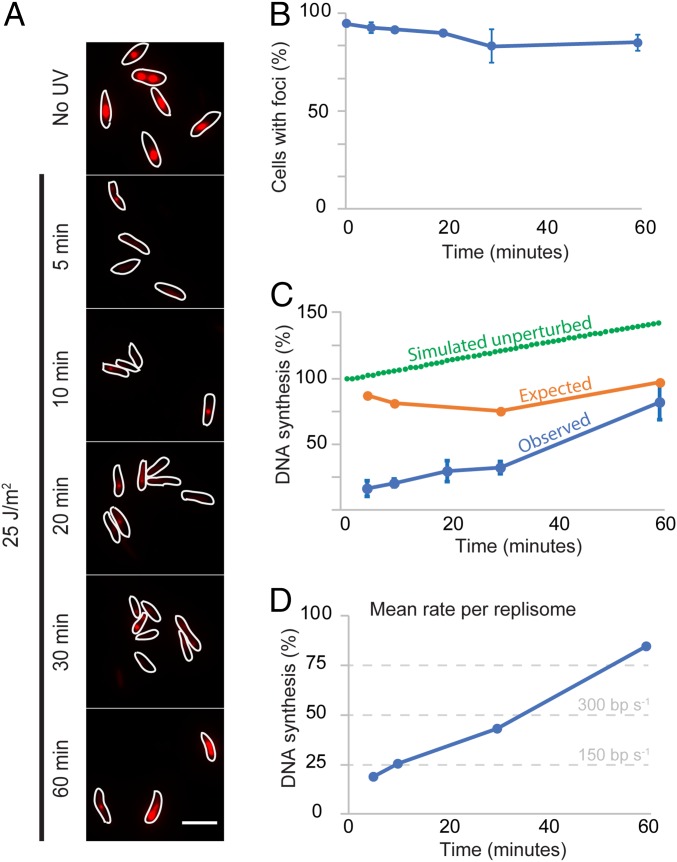

We then estimated the rate of DNA synthesis at a single cell level by fluorescently labeling newly replicated DNA through a 2-min pulse of ethyl deoxyuridine (EdU) and azide-coupled Fluor 545 (35). The number of cells with EdU fluorescent foci dropped slightly, from 93.8 ± 0.05 (SE) before UV to 82.5 ± 8.4 after 30 min (Fig. 3 A and B), indicating that DNA synthesis continued in most cells after UV treatment. We estimated the rate of new DNA incorporation based on the integrated intensity of detected spots in a given cell. DNA synthesis sharply decreased after 5 min of UV treatment, resulting in only 16.2 ± 5.8% (SE) of the incorporation in untreated cells, and progressively increasing, reaching 81.9 ± 13.8% of the original incorporation after 60 min (Fig. 3C, Observed). This decrease in DNA synthesis could be due to the fewer number of replisomes in cells following UV-induced replisome disassembly. To test this hypothesis, we calculated the predicted rate of synthesis based on our estimates of replisome loss, assuming unimpeded DNA synthesis with the same constant rate as before treatment (Fig. 3C, Expected). Interestingly, replisome loss could only account for a small part of the observed decrease in DNA synthesis, raising the possibility that the remaining replisomes act more slowly after UV. We used this “expected” rate to normalize the observed EdU incorporation so we could assess the relative synthesis rate per replisome (Fig. 3D). The corrected rates of synthesis showed that replisomes progress at 18.7% and 84.7% of their unperturbed rate 5 and 60 min after UV, respectively. Since replicating the entire chromosomes takes 65 min at 37 °C (30), we estimate that the rate of replication goes from ∼600 bp⋅s−1 before to ∼114 bp⋅s−1 5 min after UV. These results show that a considerable proportion of replication forks progress at a diminished average rate after UV treatment.

Fig. 3.

Persistence of DNA synthesis after UV. (A) Representative images of a strain carrying ∆yjjG ∆deoB after EdU labeling. Shown is a 2-min pulse of EdU, followed by fixation and coupling of fluorescence through click chemistry. Cells were sampled at various times after UV. (Scale bar: 5 μm.) Contrast and brightness have been normalized. (B) Percentage of cells with at least one focus for EdU before (0 min), and at various times after, UV. Error bars represent SE. (C) Estimated normalized DNA synthesis at various times after UV (Observed), as measured by the integrated intensity of all spots in a cell, compared with the expected synthesis if all remaining DnaB foci in Figs. 1 and 2 were fully functional replisomes (Expected), and with the expected synthesis in cells with fully functional replisomes and no replisome disassembly (Simulated unperturbed). Error bars represent SE. (D) Mean rate per replisome obtained by renormalizing the “Observed” data using the “Expected” data in C. The estimated rates in bp⋅s−1 are shown as reference.

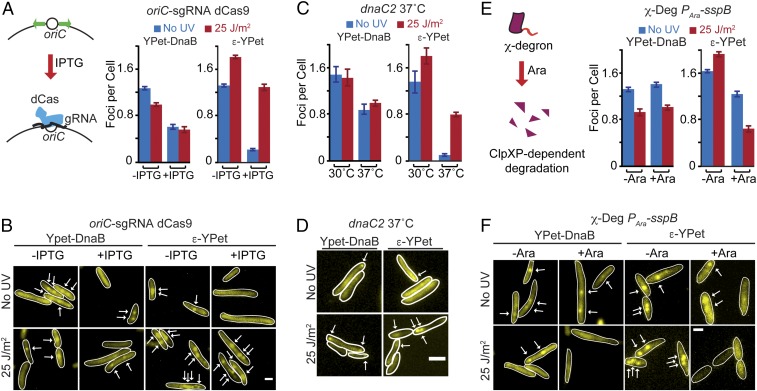

Recruitment of the Pol III HE Does Not Require Active Replication.

Copies of Pol III HE subunits at sites outside of the replication fork may mark points of DNA repair. Alternatively, they may represent new DNA replication events from oriC or mark sites behind the replication fork. To test these later models, we targeted an inactive copy of Cas9 (dCas9) to oriC, which has previously shown to inhibit initiation of DNA replication (36) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). We then waited for a period of 2 h to allow completion of ongoing DNA replication events. In these conditions, we observed a relatively high background of DnaB spots. We speculate that this is because the inhibition of initiation by dCas9 may still permit binding, but not activation, of DnaB at the oriC. But consistent with the results above, the number of spots in arrested cells did not change substantially after UV, going from 0.64 ± 0.05 to 0.58 ± 0.07 (Fig. 4 A and B). In contrast, the number of ε-YPet foci went from 0.29 ± 0.02 to 1.25 ± 0.08 after UV in the induced cells (Fig. 4 A and B). As an independent confirmation of these results, we used previously characterized strains carrying a dnaC2 temperature-sensitive allele to block initiation of DNA replication (30). As before, we allowed completion of ongoing replication events by incubating cells at the restrictive temperature (37 °C) for 2 h. Similar to the results above, we observed a relatively high background of DnaB spots, but, consistent with previous experiments, the number of spots in arrested cells changed only slightly after UV, from 0.87 ± 0.08 to 0.98 ± 0.05 (Fig. 4 C and D). In contrast, the number of ε-YPet foci went from 0.10 ± 0.02 to 0.80 ± 0.04 after UV when cells were incubated at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 4 C and D). Thus, we determined that the additional Pol III HE foci are not due to new initiation events. In addition, our results also demonstrate that additional Pol III HE foci can form even in conditions where there are no replication forks. Hence, even if some of these foci may be produced by Pol III HE binding behind the replication fork during active synthesis, a fraction of them are likely to bind elsewhere in the chromosome.

Fig. 4.

Pol III HE recruitment is independent of ongoing replication and dependent on the χ subunit. (A, Left) Description of the system to stop initiation of DNA replication. IPTG-inducible CRISPR-dCas targets the oriC to prevent new replication round. (A, Right) Cells were induced for 2 h. Average number of foci per cell of YPet-DnaB and ε-YPet before and after treatment with UV 5 min after exposure in conditions where initiation proceeds unimpeded (−IPTG) or when it is blocked (+IPTG). (B) Representative images of cells carrying YPet-DnaB or ε-YPet and the oriC blocking CRISPR-dCas system. Arrows mark positions of fluorescent foci. (Scale bar: 1 μm.) (C) Cells were incubated at the restrictive temperature for 2 h. Shown are the average number of foci per cell of YPet-DnaB and ε-YPet in a dnaC2 temperature-sensitive background at permissive and nonpermissive temperature. (D) Representative images of cells carrying YPet-DnaB or ε-YPet in a dnaC2 temperature-sensitive background at nonpermissive temperature. (Scale bar: 2 μm.) (E, Left) Description of the degron system used in this work. (E, Right) Average number of foci per cell of YPet-DnaB and ε-YPet before and after treatment with UV 5 min after exposure in conditions where χ is present (−Ara) or after χ has been degraded (+Ara). (F) Representative images of cells carrying YPet-DnaB or ε-YPet and a degradable copy of the χ subunit. (Scale bar: 1 μm.)

Recruitment of the Pol III HE Outside the Replication Fork Depends on the χ Subunit of the Clamp Loader.

Pol III HE interacts with the DnaB helicase at the replication fork, but our data suggested that it can also be at other sites independently of DnaB. To explain this observation, we hypothesized that SSB serves as an anchor for the Pol III HE at these extra sites as this protein binds to ssDNA, and SSB interacts with the χ subunit of the clamp loader (37). We tested this idea by inducing rapid depletion of the χ subunit in a strain carrying a degron-tagged version of this protein (Fig. 4 E and F) (31, 38). Imaging was done 45 min after arabinose induction. We observed a sharp decrease in the number of ε-YPet spots after UV, going from 1.22 ± 0.04 before to 0.63 ± 0.05 spots per cell after UV (Fig. 4 E and F). Depletion of χ had a smaller effect on YPet-DnaB after UV where the number of foci decreased from 1.39 ± 0.04 to 1 ± 0.04, showing a similar trend as in conditions where χ is present (Fig. 4 E and F). These results are consistent with the idea that χ helps to recruit Pol III HE at other sites of the chromosome. Nonetheless, the χ subunit has also been reported to have a role in replisome stability (39). Consequently, an alternative interpretation of these results is that UV further destabilizes the weakened χ-depleted replisome. Indeed, we observed a drop in ε-YPet foci in χ-depleted conditions before UV, compared with control cells (Fig. 4 E and F), which agrees with a role for χ in retaining Pol III HE at the fork. Consequently, at present, we cannot rule out a contribution of the stabilizing role of χ in our results.

Exposure to UV Light Changes the Binding Dynamics of the Pol III HE.

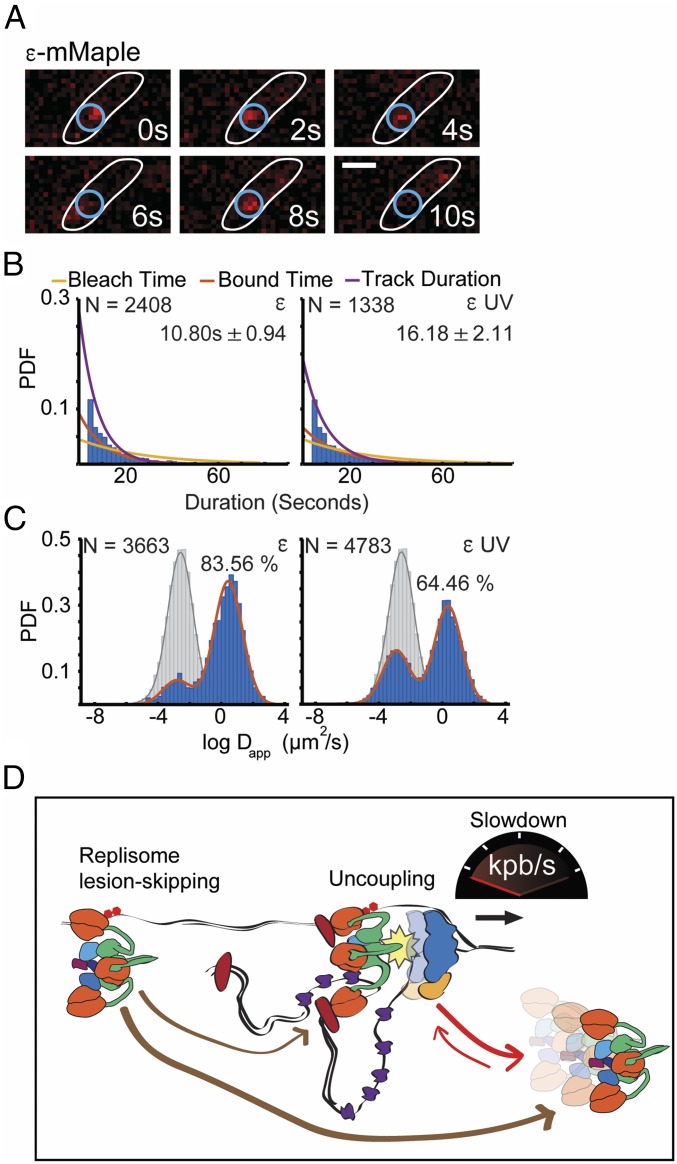

To further characterize the role of the additional Pol III HE spots in the cell, we studied the binding kinetics of the DNA Pol III using single-molecule experiments. We used a fusion of ε with the photoconvertible fluorescent protein mMaple (32, 40) and the technique of single-particle tracking Photoactivated Localization Microscopy (sptPALM) to determine the average residence time (bound time) of this subunit, as previously described (Fig. 5A) (32). Between 15 and 30 min after UV, we observed an increase in the bound time going from 10.80 s ± 0.94 before treatment, consistent with previous results (32), to 16.18 s ± 2.11 after treatment (Fig. 5B). These results are reminiscent of the increased bound time observed for Pol III* after treatment with the DNA polymerase inhibitor hydroxyurea (32).

Fig. 5.

UV irradiation affects the dynamics of the replisome. (A) Representative images of ε-mMaple in an sptPALM experiment to characterize its binding kinetics. (Scale bar: 1 μm.) (B) Representative examples of the distribution of fluorescent foci lifespans (blue bars) for Pol III ε subunit, before and after UV, showing fitting of a single-exponential decay model (purple line), the estimated bleaching rate in the same conditions (yellow line), and the corrected estimated bound time (red line). PDF, probability density function. Numbers indicate bound time in seconds with the SE in parenthesis. (Left) Pol III ε subunit before UV. (Right) Pol III ε subunit after UV (C) The distribution of the logarithm of the apparent diffusion coefficient (blue bars) for Pol III ε subunit and LacI bound control (gray bars), before and after UV, showing the fitting of a Gaussian mixture model (red and gray line). The percentage indicates the proportion of diffusing molecules. (Left) Pol III ε subunit before UV. (Right) Pol III ε subunit after UV. The y axis represents probability density function. (D) Model for the replisome slowdown. After encountering an UV lesion on the leading strand, the helicase continues unwinding through this site, but the Pol III is stalled, leading to the uncoupling between the Pol III HE and the helicase. This, in turn, results in a decrease translocation rate of the helicase. Priming by DnaG downstream of the lesion on the leading strand leads to the recruitment of a new copy or the same copy of Pol III to resume DNA synthesis, causing replisome lesion skipping.

We also determined the proportion of ε bound to DNA before and after UV by sptPALM. Capturing pictures at 20-ms rates under low-intensity continuous 405-nm laser activation, resulted on average in a single fluorescent spot per cell per frame. We characterized the behavior of DNA-bound molecules by studying a strain carrying LacI-mMaple and a lacO array where most of the molecules are bound to the chromosome (Fig. 5C) (32). The distribution of apparent diffusion coefficients for ε-mMaple before treatment showed at least two fractions, one of which represented the DNA-bound molecules—overlapping with the LacI data—and a second showing the diffusive fraction (Fig. 5C). Using a Gaussian mixture model to estimate the fraction of DNA-bound molecules in the population, we estimated that the proportion increased from 16.4% before treatment to 35.5% between 15 and 30 min after UV treatment (Fig. 5C). These data support the idea that the Pol III HE bound to DNA is not always active after UV. It also shows that exposure to UV increases the length and the frequency of the binding events of Pol III* to DNA.

Discussion

We have investigated the fate of the replisome after encountering a DNA lesion capable of inhibiting Pol III activity but that, in principle, does not threaten DnaB helicase integrity. A large body of literature that studied the effect of UV on DNA replication, spanning the last 50 y, precedes our work. However, this report focuses on the effect of UV on the replisome subunits, resulting in unique insight into the response of the replisome to DNA damage and the dynamics of DNA synthesis on a damaged DNA template. We expect that our conclusions will be also valid to other nonbulky DNA modifications that do not hinder helicase translocation.

Contrary to the long-held belief that the replisome subunits remain bound during long periods of the replication cycle, recent data from our group and other groups have demonstrated much more frequent turnover in this complex. Single-molecule in vivo data from Bacillus subtilis and E. coli have shown that the active replicative DNA polymerase is replaced every few seconds (32, 41). Similar observations were made in an independent study using a reconstituted E. coli replisome in vitro (33). Replisome disassembly exposes DNA structures sensitive to breakage, which can occur independently of external aggressions such as UV. It is therefore unclear why a stable replisome complex was not favored in evolution.

Our work unveils potential advantages of a dynamic replisome. The data are consistent with the recruitment of Pol III HE to sites other than the replication fork in a DnaB-independent manner. This is a striking result as these two subcomplexes were assumed to be found only at the replisome. We favor the model that Pol III HE is recruited at ssDNA gaps, given the presence of SSB. Polymerization activity at these sites is also likely and agrees with reports that established Pol III activity at ssDNA gaps (42, 43). Pol III HE might also contribute to loading of β-clamp at these sites, which could then serve for the recruitment of Pol V translesion polymerase. Some of these sites are likely to be found behind the replication fork, resulting from the replisome skipping over UV lesions. But since Pol III HE foci formed after UV even when cells are not replicating (Fig. 4 A–D), our data suggest that there are other recruitment sites in the chromosome which are independent of the replication fork. Loading of β-clamp away from the DNA replication fork and subsequent unbinding of the clamp loader would agree with a lack of overlap in the localization of the clamp loader and the translesion polymerases Pol IV and Pol V during DNA repair (44–46) although we note that the presence of the Pol III HE at those sites may facilitate resuming DNA synthesis after bypass by Pol V.

A Fast-Acting Rate Switch Strategy as Response to DNA Damage.

A much clearer advantage of a dynamic Pol III* binding is an almost immediate slowdown of the rate of DNA replication in response to DNA damage. Such a strategy would reduce the probability of encounters between the DnaB helicase and the engaged NER system, which may lead to helicase disassembly. It is unlikely that the rate change is due to competition of Pol III with the translesion polymerases as this effect should increase with the induction of the SOS response and should be minimal at 5 min after UV. Instead, we propose that Pol III disengages from DnaB after encountering a CPD, triggering a change in DnaB translocation rate (Fig. 5D). Previous reports show slower DnaB helicase translocation in the absence of Pol III* (47, 48). Our results show that, shortly after treatment with UV, the replisome proceeds at about 114 bp⋅s−1 (30) (Fig. 3D). This is just slightly higher than the ∼80 bp⋅s−1 single-molecule estimates of the DnaB helicase activity when it uncouples from DNA synthesis (49, 50). Thousands of CPDs are generated in the chromosome after a 25 J/m2 UV dose—we estimate one every ∼9 kbp on the leading strand based on Courcelle et al. (51). The rate of DNA synthesis progressively increased, reaching >80% of the original rate 60 min after UV, in agreement with the proposed dynamics of CPD removal after exposure to UV (52). The DNA replication averages described above using 2-min pulses of EdU labeling would then be the result of multiple cycles of engagement and disengagement, each lasting a few seconds. As such, the rate of replisome progression reflects the density of lesions on DNA.

A much greater number of replisomes simultaneously acting on the genome in eukaryotic cells, although progressing at slower rates, should increase the rate of clashes with the DNA repair systems. As in bacteria, a mechanism to rapidly modulate the rate of replisome progression has been proposed. Binding of the Mrc1–Tof1–Csm3 (MTC) complex in budding yeast has been shown to be needed for a maximal rate of DNA synthesis (53–55). In addition, the interaction between the replisome and MTC is highly dynamic, making it a good candidate to mediate a fast response to DNA damage (56). As such, fast modulation of DNA synthesis by the replisome seems to be a common strategy evolved in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. It is tempting to speculate that replisome slowdown in eukaryotes precedes the global DNA damage response (DDR), mediated by protein kinases, which should take more time to be established (57).

Continued DNA Replication after UV Supports a Replisome Lesion Skipping Model.

A classical model suggests that, after UV, DNA Pol III can hop on DNA to avoid prolonged stalling at lesions (21). A mechanistic explanation was provided by data showing that helicase progression provides a platform for priming on both strands, mediating polymerase lesion skipping after UV treatment (23, 24). We note that the original envisioning of this model, where the same copy of the DNA polymerase resumes synthesis after skipping a DNA lesion, is unlikely to occur in cells, given that Pol III* is frequently exchanged (see above). Hence, it is more probable that the resumption of DNA synthesis occurs after a different copy of Pol III* is recruited from the diffusing pool. However, consistent with the idea of lesion skipping by the replisome, our data provide yet another set of evidence by showing that, even though the rate of DNA synthesis drops after UV exposure, DNA synthesis continues (Fig. 5D). Previous reports were not able to distinguish between replisome slowdown, disassembly, and cell heterogeneity as they were based on population averages. Furthermore, we show that β-clamp continues to accumulate at sites containing DnaB helicase (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) and that the DnaB helicase remains in proximity of ε at all times after UV (Fig. 2), further supporting the idea that the activities of priming and DNA elongation continue after UV.

Experimental Procedures

Detailed descriptions of the experimental procedures used are available in SI Appendix, Supplementary Experimental Procedures. In brief, strain construction was done using P1 transduction or lambda red recombination in an AB1157 background (58). Cells were routinely grown in Luria broth or in M9 glycerol. For microscopy, cells were grown overnight in M9 glycerol and then diluted in the same medium and grown to an OD600 between 0.1 and 0.2. For degron experiments, cells were induced with 0.5% arabinose at an OD600 of 0.1 after the dilution in M9 and grown for 45 to 60 min before imaging. For degron CRISPR experiments, cells were induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) 45 min after the dilution in M9 and grown for 2 h before imaging. DnaC2 strains were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h before UV treatment. Cells were spotted on a 1% agarose pad in M9 glycerol. UV irradiation was performed in a UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene) at the dose specified in the text before placing the coverslip. Images were taken 5 min after irradiation unless stated otherwise. For single-molecule experiments, collection of images started at 15 min and ended at 30 min postirradiation. Imaging was performed at room temperature on an inverted Olympus IX83 microscope from a single-line cellTIRF illuminator (Olympus). For EdU incorporation, all cells were grown overnight in M9 glycerol at 37 °C and then diluted in the same medium and grown to an OD600 between 0.1 and 0.2. A sample of cells was put aside as an untreated control while the rest of the liquid culture was put in a sterile Petri dish and then UV irradiated. EdU to a concentration of 20 µg/mL was added for 2 min before fixation at specified times after UV exposure. Fixing and labeling were done using a modified protocol described in ref. 59. All analysis was done using custom Matlab scripts and TrackMate software in ImageJ. A custom Matlab script was used to simulate the increase in the number of copies of replisomes per cell when cell division is inhibited and replication proceeds at a slower rate. The number of repeats, sample size, and statistical tests for pairwise comparisons for all microscopy analysis presented in the figures can be found in SI Appendix, Table S4.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Anjana Badrinarayanan, Gregory Marczynski, Christian Rudolph, Steph Weber, and members of the R.R.-L. laboratory for helpful discussions. Some of the experiments were done using equipment from the Integrated Quantitative Bioscience Initiative (IQBI), funded by Canada Foundation for Innovation 9. This work was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC 435521-2013), the Fonds de Recherche du Quebec–Nature et Technologies (FRQNT 2017-NC-198919), the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR MOP 142473), the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI 228994), and the Canada Research Chairs program.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1819297116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Beattie T. R., Reyes-Lamothe R., A replisome’s journey through the bacterial chromosome. Front. Microbiol. 6, 562 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis J. S., Jergic S., Dixon N. E., The E. coli DNA replication fork. Enzymes 39, 31–88 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tougu K., Marians K. J., The interaction between helicase and primase sets the replication fork clock. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21398–21405 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tougu K., Marians K. J., The extreme C terminus of primase is required for interaction with DnaB at the replication fork. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21391–21397 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao D., McHenry C. S., Tau binds and organizes Escherichia coli replication through distinct domains. Partial proteolysis of terminally tagged tau to determine candidate domains and to assign domain V as the alpha binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4433–4440 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stukenberg P. T., Studwell-Vaughan P. S., O’Donnell M., Mechanism of the sliding beta-clamp of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 11328–11334 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao D., McHenry C. S., Tau binds and organizes Escherichia coli replication proteins through distinct domains. Domain IV, located within the unique C terminus of tau, binds the replication fork, helicase, DnaB. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4441–4446 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pham T. M., et al. , A single-molecule approach to DNA replication in Escherichia coli cells demonstrated that DNA polymerase III is a major determinant of fork speed. Mol. Microbiol. 90, 584–596 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuzminov A., Recombinational repair of DNA damage in Escherichia coli and bacteriophage lambda. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 751–813 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krwawicz J., Arczewska K. D., Speina E., Maciejewska A., Grzesiuk E., Bacterial DNA repair genes and their eukaryotic homologues: 1. Mutations in genes involved in base excision repair (BER) and DNA-end processors and their implication in mutagenesis and human disease. Acta Biochim. Pol. 54, 413–434 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iyer R. R., Pluciennik A., Burdett V., Modrich P. L., DNA mismatch repair: Functions and mechanisms. Chem. Rev. 106, 302–323 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Truglio J. J., Croteau D. L., Van Houten B., Kisker C., Prokaryotic nucleotide excision repair: The UvrABC system. Chem. Rev. 106, 233–252 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marians K. J., Lesion bypass and the reactivation of stalled replication forks. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 87, 217–238 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michel B., Boubakri H., Baharoglu Z., LeMasson M., Lestini R., Recombination proteins and rescue of arrested replication forks. DNA Repair 6, 967–980 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michel B., Sandler S. J., Replication restart in bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 199, e00102-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinha R. P., Häder D. P., UV-induced DNA damage and repair: A review. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 1, 225–236 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Echols H., Goodman M. F., Mutation induced by DNA damage: A many protein affair. Mutat. Res. 236, 301–311 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belle J. J., Casey A., Courcelle C. T., Courcelle J., Inactivation of the DnaB helicase leads to the collapse and degradation of the replication fork: A comparison to UV-induced arrest. J. Bacteriol. 189, 5452–5462 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Setlow R. B., Swenson P. A., Carrier W. L., Thymine dimers and inhibition of DNA synthesis by ultraviolet irradiation of cells. Science 142, 1464–1466 (1963). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyce R. P., Howard-Flanders P., Release of ultraviolet light-induced thymine dimers from DNA in E. Coli K-12. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 51, 293–300 (1964). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rupp W. D., Howard-Flanders P., Discontinuities in the DNA synthesized in an excision-defective strain of Escherichia coli following ultraviolet irradiation. J. Mol. Biol. 31, 291–304 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Courcelle C. T., Belle J. J., Courcelle J., Nucleotide excision repair or polymerase V-mediated lesion bypass can act to restore UV-arrested replication forks in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187, 6953–6961 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeeles J. T., Marians K. J., The Escherichia coli replisome is inherently DNA damage tolerant. Science 334, 235–238 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeeles J. T., Marians K. J., Dynamics of leading-strand lesion skipping by the replisome. Mol. Cell 52, 855–865 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McInerney P., O’Donnell M., Replisome fate upon encountering a leading strand block and clearance from DNA by recombination proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25903–25916 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pagès V., Fuchs R. P., Uncoupling of leading- and lagging-strand DNA replication during lesion bypass in vivo. Science 300, 1300–1303 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higuchi K., et al. , Fate of DNA replication fork encountering a single DNA lesion during oriC plasmid DNA replication in vitro. Genes Cells 8, 437–449 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeiranian H. A., Schalow B. J., Courcelle C. T., Courcelle J., Fate of the replisome following arrest by UV-induced DNA damage in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 11421–11426 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudolph C. J., Upton A. L., Lloyd R. G., Replication fork stalling and cell cycle arrest in UV-irradiated Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 21, 668–681 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reyes-Lamothe R., Possoz C., Danilova O., Sherratt D. J., Independent positioning and action of Escherichia coli replisomes in live cells. Cell 133, 90–102 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reyes-Lamothe R., Sherratt D. J., Leake M. C., Stoichiometry and architecture of active DNA replication machinery in Escherichia coli. Science 328, 498–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beattie T. R., et al. , Frequent exchange of the DNA polymerase during bacterial chromosome replication. eLife 6, e21763 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis J. S., et al. , Single-molecule visualization of fast polymerase turnover in the bacterial replisome. eLife 6, e23932 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heller R. C., Marians K. J., Replisome assembly and the direct restart of stalled replication forks. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 932–943 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salic A., Mitchison T. J., A chemical method for fast and sensitive detection of DNA synthesis in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2415–2420 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiktor J., Lesterlin C., Sherratt D. J., Dekker C., CRISPR-mediated control of the bacterial initiation of replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 3801–3810 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelman Z., Yuzhakov A., Andjelkovic J., O’Donnell M., Devoted to the lagging strand-the subunit of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme contacts SSB to promote processive elongation and sliding clamp assembly. EMBO J. 17, 2436–2449 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGinness K. E., Baker T. A., Sauer R. T., Engineering controllable protein degradation. Mol. Cell 22, 701–707 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marceau A. H., et al. , Structure of the SSB-DNA polymerase III interface and its role in DNA replication. EMBO J. 30, 4236–4247 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McEvoy A. L., et al. , mMaple: A photoconvertible fluorescent protein for use in multiple imaging modalities. PLoS One 7, e51314 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao Y., Li Y., Schroeder J. W., Simmons L. A., Biteen J. S., Single-molecule DNA polymerase dynamics at a bacterial replisome in live cells. Biophys. J. 111, 2562–2569 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sedgwick S. G., Bridges B. A., Requirement for either DNA polymerase I or DNA polymerase 3 in post-replication repair in excision-proficient Escherichia coli. Nature 249, 348–349 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson R. C., Reduction of postreplication DNA repair in two Escherichia coli mutants with temperature-sensitive polymerase III activity: Implications for the postreplication repair pathway. J. Bacteriol. 136, 125–130 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson A., et al. , Regulation of mutagenic DNA polymerase V activation in space and time. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005482 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henrikus S. S., et al. , DNA polymerase IV primarily operates outside of DNA replication forks in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007161 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thrall E. S., Kath J. E., Chang S., Loparo J. J., Single-molecule imaging reveals multiple pathways for the recruitment of translesion polymerases after DNA damage. Nat. Commun. 8, 2170 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim S., Dallmann H. G., McHenry C. S., Marians K. J., Coupling of a replicative polymerase and helicase: A tau-DnaB interaction mediates rapid replication fork movement. Cell 84, 643–650 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dallmann H. G., Kim S., Pritchard A. E., Marians K. J., McHenry C. S., Characterization of the unique C terminus of the Escherichia coli tau DnaX protein. Monomeric C-tau binds alpha AND DnaB and can partially replace tau in reconstituted replication forks. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 15512–15519 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ribeck N., Kaplan D. L., Bruck I., Saleh O. A., DnaB helicase activity is modulated by DNA geometry and force. Biophys. J. 99, 2170–2179 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Graham J. E., Marians K. J., Kowalczykowski S. C., Independent and stochastic action of DNA polymerases in the replisome. Cell 169, 1201–1213.e17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Courcelle C. T., Chow K. H., Casey A., Courcelle J., Nascent DNA processing by RecJ favors lesion repair over translesion synthesis at arrested replication forks in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9154–9159 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koehler D. R., Courcelle J., Hanawalt P. C., Kinetics of pyrimidine(6-4)pyrimidone photoproduct repair in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178, 1347–1350 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tourrière H., Versini G., Cordón-Preciado V., Alabert C., Pasero P., Mrc1 and Tof1 promote replication fork progression and recovery independently of Rad53. Mol. Cell 19, 699–706 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Szyjka S. J., Viggiani C. J., Aparicio O. M., Mrc1 is required for normal progression of replication forks throughout chromatin in S. cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 19, 691–697 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeeles J. T. P., Janska A., Early A., Diffley J. F. X., How the eukaryotic replisome achieves rapid and efficient DNA replication. Mol. Cell 65, 105–116 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lewis J. S., et al. , Single-molecule visualization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae leading-strand synthesis reveals dynamic interaction between MTC and the replisome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 10630–10635 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iyer D. R., Rhind N., The intra-S checkpoint responses to DNA damage. Genes (Basel) 8, E74 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L., One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang X., Lesterlin C., Reyes-Lamothe R., Ball G., Sherratt D. J., Replication and segregation of an Escherichia coli chromosome with two replication origins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E243–E250 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.