Significance

Structures of GPCR–G-protein complexes show how cognate G proteins interact with GPCRs. However, noncognate GPCR–G-protein interactions are poorly understood, despite their relevance in cells. The conceptual advancements in our study show 1) the C terminus of Gαs, Gαi, and Gαq proteins assume a small dynamic ensemble of unique orientations when coupled to their cognate GPCRs, explaining the variations observed in the X-ray and cryo-EM structures of GPCR–G-protein complexes; and 2) the noncognate G proteins interact dynamically with latent, previously uncharacterized cavities within the GPCR cytosolic cavity. Engineering these latent cavities with hotspots to the noncognate G proteins tunes promiscuity in the GPCR. This study provides a framework for understanding how GPCR dynamics subtly modulate signaling in different pathways.

Keywords: G-protein−coupled receptor, GPCR, functional selectivity, structural plasticity, dynamics

Abstract

While the dynamics of the intracellular surface in agonist-stimulated GPCRs is well studied, the impact of GPCR dynamics on G-protein selectivity remains unclear. Here, we combine molecular dynamics simulations with live-cell FRET and secondary messenger measurements, for 21 GPCR−G-protein combinations, to advance a dynamic model of the GPCR−G-protein interface. Our data show C terminus peptides of Gαs, Gαi, and Gαq proteins assume a small ensemble of unique orientations when coupled to their cognate GPCRs, similar to the variations observed in 3D structures of GPCR−G-protein complexes. The noncognate G proteins interface with latent intracellular GPCR cavities but dissociate due to weak and unstable interactions. Three predicted mutations in β2-adrenergic receptor stabilize binding of noncognate Gαq protein in its latent cavity, allowing promiscuous signaling through both Gαs and Gαq in a dose-dependent manner. This demonstrates that latent GPCR cavities can be evolved, by design or nature, to tune G-protein selectivity, giving insights to pluridimensional GPCR signaling.

G-protein−coupled receptors (GPCRs) bind a diverse array of agonists and regulate multiple physiological processes. Upon binding agonists, GPCRs couple to single or multiple G-protein subtypes and initiate cell-specific signaling pathways. Studies with novel bioluminescence resonance energy transfer sensors show GPCRs exhibit a promiscuous and “pluridimensional” behavior, coupling to many Gα-proteins with different strengths (1–4). While a receptor may show similar affinity to different Gα proteins, the cellular context may render certain couplings moot (1, 5–9). There are four major subtypes of heterotrimeric (Gαβγ) G proteins, typified by the Gα subunit: Gαs, Gαi/o, Gαq/11, and Gα12/13. The downstream cellular response elicited by G-protein signaling pathways are dependent on these distinct Gα-protein subfamilies. Current models of G-protein signaling cannot explain why certain GPCRs bind multiple subtypes, while others are selective. Currently, seven distinct 3D structures of Class A agonist−GPCR−G-protein complexes (10–16) provide details on the residue interactions in the GPCR−G-protein interface. This structural information, coupled with phylogenetic analysis of GPCR and G-protein sequences, highlight the G-protein barcodes for selectivity (17, 18). However, untangling which of these interacting pairs are critical “hotspots” mediating selectivity warrants probing the dynamics of the GPCR−G-protein interface, the focus of our current study.

Seminal works have shed light on the critical involvement of GPCR intracellular (IC) loops and the transmembrane (TM) helix 6 (TM6) interface in mediating selective G-protein interactions (19–23). Analysis of 3D structures combined with previous cell-based assay studies show the α5 helix in the C terminus of the Gα protein exhibits a large effect on selective coupling to GPCRs (24–29). Here we study the dynamic interactions of the C terminus of Gαs, Gαi, and Gαq proteins, hereafter referred to as s-pep, i-pep, and q-pep, in combination with seven class A GPCRs (β2-Adrenergic Receptor, β2AR; β3-Adrenergic Receptor, β3AR; Dopamine 1 Receptor, D1R; α2A-Adrenergic Receptor, α2AAR; Cannabinoid 1 Receptor, CB1R; α1A-Adrenergic Receptor, α1AAR; and Vasopressin 1A Receptor, V1AR), to delineate the GPCR−G-protein selectivity determinants. Our focus is to delineate the contribution of the receptor−G-protein dynamics in G-protein selectivity and promiscuity.

Previous receptor dynamics studies showed that agonist binding makes the IC half of the receptor more dynamic and conformationally heterogeneous (30–32), while G-protein binding stabilizes the GPCR conformation and increases the affinity of a GPCR for a full agonist (33–35). Detailed dynamics studies of the agonist−GPCR−Gα-protein complex to identify selectivity determinants are sparse. In this work, we use extensive Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations combined with a scalable fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) sensor technique called Systematic Protein Affinity Strength Modulation (SPASM) that is performed in live cells. The advantage of the SPASM technique is that tethering GPCRs to Gα proteins with the length-adjustable α-helical ER/K linker (36) allows scaling of the effective localized concentration of GPCR and Gα protein to span various, plausible, cellular concentrations. SPASM is sensitive to measuring weak and dynamic protein−protein interactions in cellular conditions (29, 37, 38). This permits comparison between the binding affinities of cognate (canonical signaling partners) and noncognate (weak or uncharacterized partners) Gα proteins at the same stoichiometric ratios with the GPCR, which is not feasible with other biophysical techniques used in live cells (1, 4, 39, 40). Recent findings with SPASM FRET sensors show a physiologic effect of noncognate G proteins to prime GPCR signaling within the cell (41), demonstrating the importance for probing these noncognate G-protein interactions within the cell.

The key findings from our study are as follows: 1) The Gα peptides assume a small ensemble of unique orientations when coupled to a cognate GPCR. 2) The s-pep binds in a different IC cavity of its cognate GPCR and orients its C terminus toward TM helices 5 and 6 (TM5 and TM6) compared with i-pep and q-pep that orient toward TM2 and IC loop 1 (ICL1). 3) MD simulations of β2AR complexed with the noncognate q-pep reveal formation of a transient cavity in the β2AR IC interface, resembling the stable IC cavity observed in the V1AR:q-pep complex. Mutation of the hotspot residues identified for Gαq coupling in V1AR, into β2AR, stabilizes this transient cavity. We have generated a triple mutant, β2AR−Q142K5.67−R228I5.68−Q229W34.54, that displays dose-dependent, isoproterenol-induced, promiscuity toward Gαs- and Gαq-coupled signaling pathways. 4) This promiscuous β2AR mutant demonstrates that GPCRs contain defined, latent IC receptor cavities showing weak interactions with noncognate G proteins. These latent cavities can couple to the noncognate G proteins if stabilized with the necessary hotspot residues, through mutagenesis or natural evolution. The promiscuous β2AR mutant thus serves as a model system to probe the dynamics of GPCRs exhibiting pluridimensional G-protein coupling. Our dynamics-based framework reveals the structural plasticity of the GPCR cytosolic pocket that underlies G-protein selectivity and the role of noncognate G-protein interactions in influencing GPCR dynamics. Furthermore, this study provides features of the GPCR−G-protein interaction that can be targeted by functionally selective drugs to tune therapeutic response to specific GPCR signaling pathways (42).

Results

Cognate GPCR−Gα-Protein C Terminus Complexes Reveal Distinct Conformations for Gαs, Gαi, and Gαq Signaling Pairs.

We performed atomistic MD simulations and generated a minimum of 1-μs ensembles for seven different class A GPCRs bound to full agonists and complexed with each of three Gα peptides (SI Appendix, Table S1). From the MD data, we detect that s-pep, i-pep, and q-pep insert in distinct cavities within the IC interface of their respective cognate GPCRs (Fig. 1 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). The N terminus of the Gα peptides, which protrude out of the GPCR IC cavity, are highly flexible during the MD simulations and normally engaged in intramolecular interactions with the “Ras” domain of the Gα protein (43, 44). Therefore, we omitted the N-terminal region for analysis of receptor−G-protein contacts. The C terminus of the Gα peptides (indicated by “*”, Fig. 1B) insert into the GPCR IC cavity and retain helicity. We have used the axis defined by this helical region of the Gα peptide [Common G-protein Numbering, residues H5.12 to H5.26 (17)] for our analyses of Gα-peptide orientation.

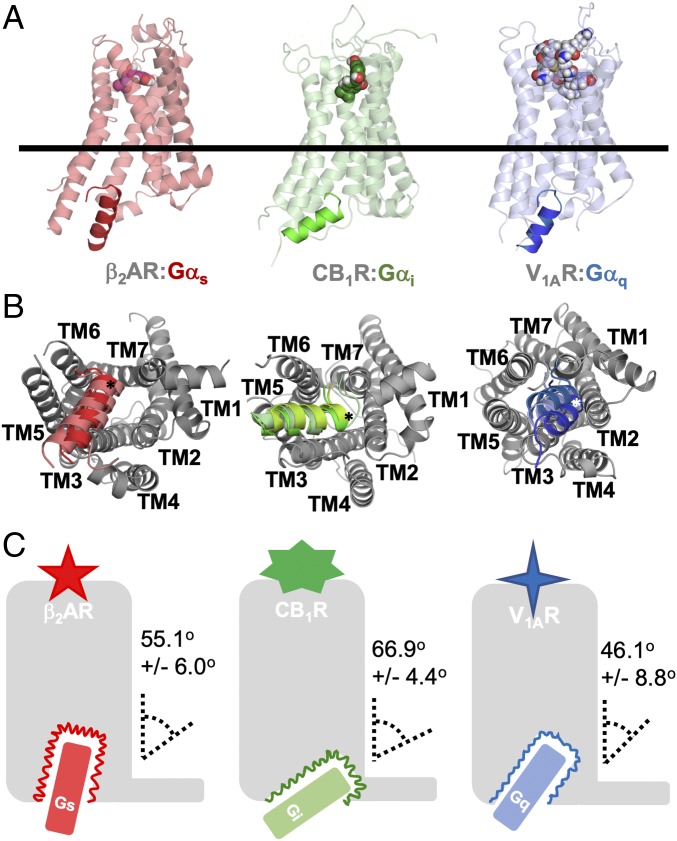

Fig. 1.

The s-pep, i-pep, and q-pep reveal distinct binding orientations in GPCR cavity of respective, cognate GPCRs. (A) View of the β2AR:s-pep (Left), CB1R:i-pep (Center), and V1AR:q-pep (Right) complexes. Each receptor is shown oriented parallel to the membrane-normal, with a horizontal plane bisecting the TM helices at the vertical center of the protein complex. The orientations of the three bound peptides in their respective cognate receptors vary. (B) IC view of each complex from A. Simulations were clustered by RMSD of the peptide backbone, and the representative conformation of the Gα peptide from the top three clusters is shown for each complex. In this view, we observe distinct differences with the orientation of each peptide, particularly that the C-terminal end of the helical portion of each peptide (denoted by “*”) points toward distinct IC regions of the respective GPCRs. (C) A schematic for each unique GPCR−Gα-peptide complex is shown. The colored wavy line which outlines the receptor IC cavity surrounding the Gα peptide represents the dynamic interface of the GPCR as it contacts and interfaces the G-protein C terminus. We have calculated the insertion angle of the principle axis of the G-protein C terminus with the principle axis of the GPCR and provided this value here. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S1.

The GPCR conformations shown (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B) are the centroid of the most populated conformation cluster from the ensemble of MD trajectories with the cognate Gα peptide bound. The Gα-peptide conformations shown in Fig. 1B, are centroids from the top three populated clusters of these simulations. The central region of all of the three Gα peptides are anchored to TM5 and ICL2 of their given GPCRs. The extreme C termini of i-pep and q-pep orient toward TM2, ICL1, and ICL2 in their cognate GPCRs, while the C terminus of s-pep orients toward an interface between TM6 and TM7 (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). We calculated the insertion of the Gα peptides in their cognate GPCRs as the angle between the principal axis of the GPCR TM core bundle and principal axis of the Gα-protein α5 helix for each cognate GPCR−G-protein simulation. We did the same for the X-ray and cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM) structures (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B and Table S2). The three Gα-protein subtypes show different angles of insertion in the GPCR IC cavity. There is also variation in the insertion angles even among the three Gαs coupled receptors studied here. Our previous FRET sensor studies (29, 37) have shown differences in coupling strengths of Gαs to β2AR, β3AR, and D1R in the order β2AR > β3AR > D1R. As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S1C, the calculated average interaction energy from MD simulations of s-pep with β2AR, β3AR, and D1R showed the same trend as observed in the FRET sensor experiments. We speculate that the differences in the α5-helix insertion may modulate the strength of interaction between GPCR and Gα peptide.

Only Cognate GPCR−Gα-Peptide Pairs Stabilize Clamping of GPCR IC Cavity on α5 Helix.

GPCRs and G proteins cluster in plasma membrane domains (45), inflating the relative concentration of cognate and noncognate G proteins compared with GPCRs (5). Gupte et al. (41) showed that noncognate G proteins can synergize the signaling efficacy of cognate G proteins. To assess how cognate and noncognate G-protein interactions affect the GPCR IC cavity, we calculated the first-order torsional entropy of the GPCR residues which interface the G protein (GPI) (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S4). A schematic of side-chain conformations of the β2AR residues with highest entropy is shown (Fig. 2B). The GPI residues show lower entropy when coupled to their cognate G proteins compared with noncognate G proteins. We also observed increased flexibility in the GPCR IC cavity measured as the distance between residues 3.50 and 6.30 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A) (46) when bound to noncognate G proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B and Table S3). The residue notations shown are the Ballesteros−Weinstein GPCR numbering system (47).The reduced entropy and flexibility of cognate interactions allows the GPCR residues in the IC cavity to form strong enthalpic interactions with the G protein, except in the Gαq-coupled α1AAR. We and others have shown, through live-cell coupling data, that α1AAR interacts promiscuously with all three Gα peptides (29, 48).

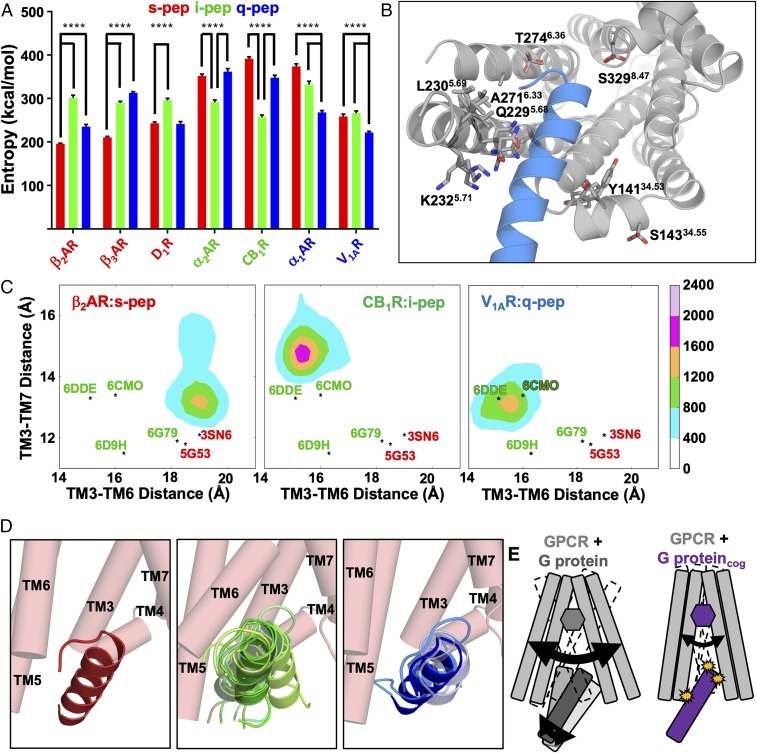

Fig. 2.

Dynamic properties of the cognate and noncognate agonist−GPCR−Gα-peptide interfaces that stabilize a signaling complex. (A) First-order torsional entropy values calculated at 300 K, using torsion angles distribution for the GPI residues of each GPCR in the presence of cognate and noncognate Gα peptides. Values are shown as means from five replicate simulations ± SEM for s-pep (red), i-pep (green), and q-pep (blue). Significance was calculated using two-sided ANOVA; ****P < 0.0001. (B) Visual model of the sampled rotamer conformations for the GPI residues of the β2AR with the highest entropy values when bound to noncognate Gα peptides. The spread of sampled rotamer angles is shown in transparent sticks. (C) Population distribution of the MD simulation snapshots for β2AR, CB1R, and V1AR when bound to their respective agonists and cognate Gα peptides, with respect to interresidue distances between TM3 and TM6, and TM3 and TM7, shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S2A; “*” denotes the interresidues distances for X-ray and cryo-EM structures, colored as in A, based on G-protein preference: 3SN6-Gαs−bound β2AR (red); 5G53-mini-Gαs−bound A2AR (red); 6DDE-Gαi−bound μOR (green); 6D9H-Gαi−bound A1R (green); 6G79-Gαo−bound 5HT-1BR (green); and 6CMO-Gαi−bound Rhodopsin (green). (D) Representation of centroids from conformational clusters of the cognate and noncognate Gα peptides bound to β2AR (shown as pink cylinders). The top clusters making up 85% of the conformational ensemble are shown. The noncognate i-pep (nine clusters, green) and q-pep (three clusters, blue) in β2AR show greater flexibility as multiple conformation clusters compared with s-pep (one cluster, red). (E) Model derived from the data in this figure: Both receptor and (cognate and noncognate) Gα peptides are highly dynamic upon interaction (Left). Thermodynamically favorable interactions allow the GPCR IC cavity to clamp onto the Gα peptide and stabilize the dynamics of the complex (Right). See also SI Appendix, Fig. S2.

The elongation of the interresidue distance between residues 3.50 and 6.30 and the contraction of the residue distance between 3.50 and 7.53 are characteristics of GPCR activation (46, 49, 50) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). MD trajectories of β2AR, β3AR, and D1R complexed with s-pep projected on these two distances show ensembles of states close to the conformation in the crystal structure of β2AR with nucleotide-free Gs [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 3SN6] and adenosine 2A Receptor (A2AR) bound to mini-Gs protein (PDB ID code 5G53; Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). Both CB1R and V1AR, with i-pep and q-pep, respectively (Fig. 2C), show ensembles representing the active state identified in the cryo-EM structures of μ Opioid Receptor (μOR) and Rhodopsin with nucleotide-free trimeric Gi (PDB ID codes 6DDE and 6CMO). We also observe that the α2AAR and α1AAR both sample active states similar to the A2AR bound to mini-Gs, Serotonin 1B Receptor (5HT-1B) bound Go protein, and β2AR bound to nucleotide-free Gαs (PDB ID codes 5G53, 6G79, and 3SN6). These distances in the X-ray and cryo-EM structures of G-protein−bound class A GPCRs are also shown in SI Appendix, Table S2.

We analyzed the Gα-peptide conformational dynamics by clustering the Gα-peptide MD simulation trajectories using root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) in coordinates. The cognate Gα peptide is stabilized in the majority of the seven GPCRs, revealed by fewer conformational clusters compared with the number of clusters sampled by noncognate Gα peptides (SI Appendix, Table S5). In the cognate interaction of β2AR with the s-pep, >85% of the MD snapshots are located within the top cluster (Fig. 2 D, Left), whereas the noncognate i-pep (green) and q-pep (blue) sample only 30% (top nine clusters to reach >85% population) and 67% (top three clusters to reach >85% population), respectively, of the population within the top cluster (Fig. 2 D, Center and Right). Taken together, these results show that the GPCR clamps tighter on the cognate Gα C terminus, lowering the flexibility, and improves the enthalpic interaction leading to productive signaling (Fig. 2E). The noncognate Gα peptides show high flexibility, show weaker interactions in the GPCR IC cavity, and eventually fall out of the cavity.

Identifying Amino Acid Hotspots in the C Terminus α5 Helix That Confer Selectivity to GPCRs.

We used an iterative combination of MD simulation analysis and SPASM experiments to identify the amino acid residues in each Gα peptide which confer selectivity to their cognate receptors among the seven studied (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). We identified residues on the Gα peptide that remain in helical conformation, and show above-average favorable interaction energies and sustained contacts (with >50% frequency) during the dynamics with the GPCR (shown in yellow boxes and bold, colored font, Fig. 3A and Materials and Methods). We observe these predicted selectivity hotspot residues to be both conserved and mutated across the Gα peptides. Where applicable, the hotspot residues were swapped with homologous positions from another Gα peptide, and binding was tested with the cognate GPCRs for both the cognate and mutated noncognate Gα peptides. For the hotspots conserved in both position and sequence across Gα peptides, the residue was mutated to alter amino acid physical characteristics and test disruption in the cognate complex.

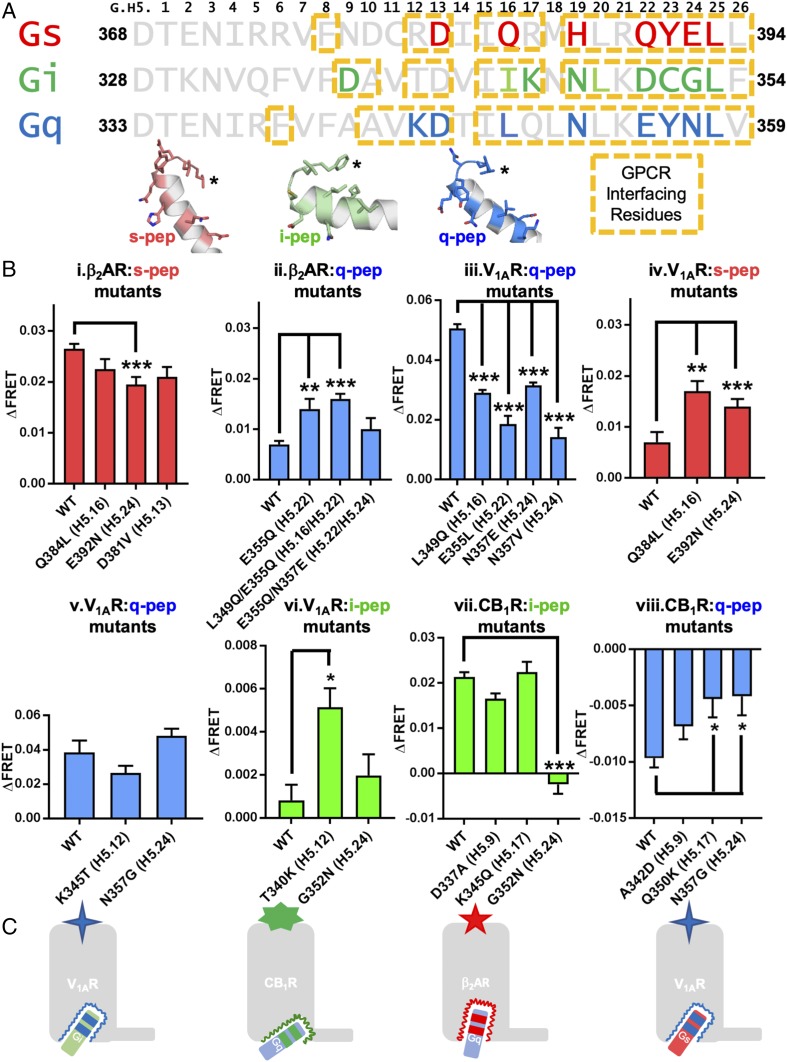

Fig. 3.

Hotspots in the G-protein α5 helix identified in cognate GPCR–Gα-peptide pairs. (A) Sequence alignment of the α5 helix of Gαs, Gαi, and Gαq C termini. The residues on the Gα peptides that make up the GPCR-interfacing residues (based on frequency of interaction) with their cognate receptors are shown in yellow boxes. The significant energetically favorable residue hotspots are marked in bold and colored font in the respective sequences and shown in stick representation in the cartoon of the Gα peptides shown below the alignment. The C termini of the peptides are marked with an asterisk for visual orientation. (B) Selectivity “hotspot” residues predicted from MD simulations were validated in SPASM FRET sensors, by mutating the Gα-peptide residue to a homologous residue of another Gα protein, and testing the interaction of the mutant Gα peptide with the original cognate GPCR (i, iii, v, vii) or the cognate GPCR of the homologous “donor” Gα peptide (ii, iv, vi, viii). (B, iv) Republished with permission of American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, from ref. 29; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. Mean FRET values were compared by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s comparison of means. Significance is denoted as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (C) The schematic model depicts that mutations to the selectivity hotspots in the α5 helix orient noncognate Gα peptides into a cognate-like orientation within a given GPCR, by making the Gα peptide amenable to the GPCR cavity available for binding. See also SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4.

We hypothesized that the swapping mutations would enable GPCRs to couple to noncognate Gα peptides with appropriate “cognate-like” swapping mutations. We tested this swapping between s-pep and q-pep and also between i-pep and q-pep using β2AR for Gαs coupling, V1AR for Gαq coupling, and CB1R for Gαi coupling. The mutations were made in SPASM FRET sensor constructs and transiently transfected into HEK-293T cells. FRET ratio is measured as agonist-stimulated minus unstimulated FRET, and comparisons to the wild type (WT) were calculated (SI Appendix, Table S6). The swapping mutations in the cognate Gα peptides led to significant reduction in FRET intensity changes upon treatment with agonist as shown in Fig. 3 B, i for β2AR with the q-like mutations in s-pep, Fig. 3 B, iii for V1AR with s-like mutations in q-pep, Fig. 3 B, vii for CB1R with q-like mutations in the i-pep, and Fig. 3 B, v for V1AR with i-like mutations in q-pep. These results affirm the conclusion that Gαs residue E392H5.24, Gαq residues L349H5.16, E355H5.22, and N357H5.24, and Gαi residue G352H5.24 are some of the selectivity hotspot residues. The details of the FRET data are discussed in SI Appendix, Table S6.

We performed reciprocal, gain-of-coupling experiments by introducing cognate hotspot residue mutations into homologous structural positions in noncognate Gα peptides. We performed FRET assays for β2AR with s-like mutations in q-pep (Fig. 3 B, ii), V1AR with q-like mutations in s-pep and also q-like mutations in i-pep (Fig. 3 B, iv and vi), and CB1R with i-like mutations in q-pep (Fig. 3 B, viii). These data show that the following residue positions mediate significant increase in G protein coupling to the noncognate GPCR: Gαq residues E355QH5.22, E355QH5.22/L349QH5.16 with β2AR (Fig. 3 B, ii); Gαs residues Q384LH5.16, E392NH5.24 (Fig. 3 B, iv), and Gαi residue T340KH5.12 with V1AR (Fig. 3 B, vi); and Gαq residues Q350KH5.17, N357GH5.24 with CB1R (Fig. 3 B, viii). Taken together, these results show that positions H5.16, H5.22, and H5.24 play a critical role in binding of all three Gα subtypes to their respective GPCRs, with positions H5.12 and H5.17 involved in ancillary roles within the Gαi and Gαq interactions. These experiments suggest that the IC cavity of a given GPCR recognizes a small number of critical structural features in the α5 helix of the Gα protein, and, if these minimal features are present in the correct orientation, the Gα protein can complex with the GPCR. This is exemplified in MD simulations of the β2AR with the noncognate q-pep becoming stabilized in the GPCR IC cavity, similar to the cognate s-pep, with the addition of the s-pep H5.16 and H5.22 hotspots (L349Q/E355Q) (Movie S1).

Rational Design of a Promiscuous β2AR Gαq- and Gαs-Coupled Receptor.

Fig. 4A shows the contribution from residues in each TM and ICL region in the Gαs-, Gαi-, or Gαq-coupled receptors toward binding their cognate Gα peptides. The relative sizes of the circles reflect the percentage of total contacts (SI Appendix, Table S7) contributed from the TM or ICL region of the given GPCR. Specifically, Gαs-coupled receptors interact with the s-pep primarily through contacts on TM3, TM5, and TM6. The i-pep contacts the residues in TM3, TM5, TM6, and ICL2 in the Gαi-coupled receptors. Most contacts in Gαq-coupled receptors are from TM2, TM3, TM5, TM6, and ICL2. Both Gαi- and Gαq-coupled receptors, but not Gαs-coupled receptors, contact the C terminus of their respective peptides through ICL1 residues. The predicted pairwise interactions between the Gα peptides and their respective cognate GPCRs are given in SI Appendix, Table S8.

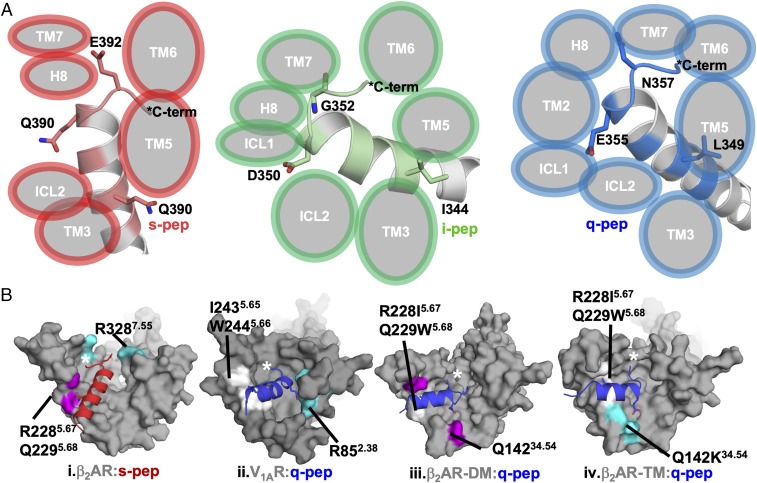

Fig. 4.

Reshaping of the IC surface of β2AR to accommodate Gαq. (A) The regions in the IC surface of the GPCR that interact with their respective cognate G peptides, as calculated from the MD simulation trajectories. The size of the circles shows the level of interaction with that particular TM helix. The larger the circle, the more favorable and stronger is the interaction with the receptor. The s-pep interaction with IC region of β2AR is shown in red, i-pep interaction with the CB1R is shown in green, and q-pep interaction with V1AR is shown in blue. The peptides are shown in cartoon representation. The C termini of the Gα peptides are indicated by an asterisk in the figure. (B) (i) The orientation of binding of the s-pep (red cartoon) in β2AR. Residues R2285.67 and Q2295.68 anchor H5.16 of s-pep to TM5, while R3287.55 draws the C terminus (H5.24) toward TM6 and TM7. (ii) The corresponding q-pep (blue cartoon) H5.16 anchoring residues in TM5 are W2445.66 and I2435.65 in V1AR, and the R852.38 residue draws the C terminus (H5.22) of q-pep toward ICL1 and TM2. (iii) The q-pep orientation in the double-mutant β2AR−R228I−Q229W. (iv) The q-pep−bound triple-mutant β2AR−Q142K−R228I−Q229W shows the same orientation as the q-pep in V1AR.

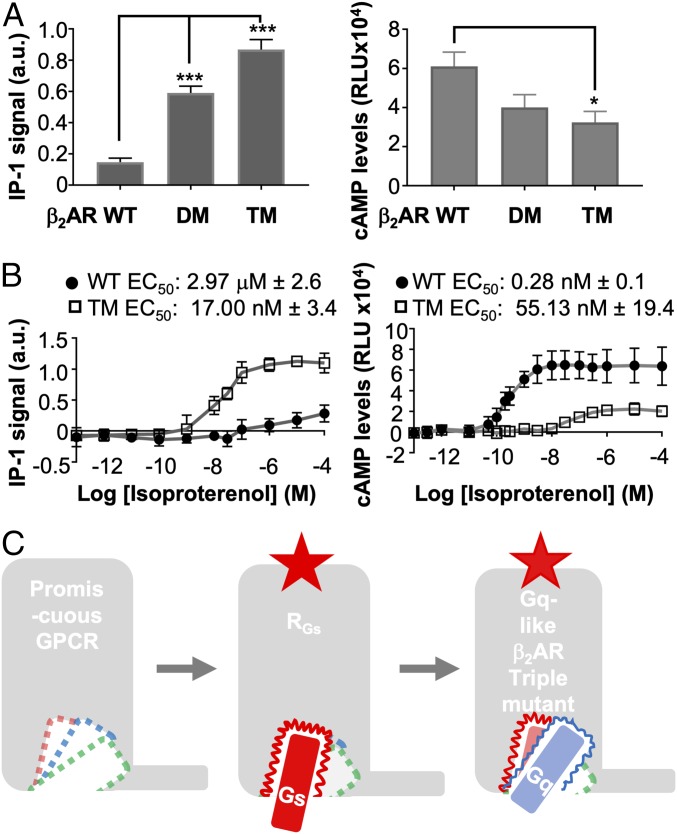

Similar to the swapping mutations we tested in Gα-peptide hotspots, we predicted GPCR hotspot swapping mutations to allow promiscuous coupling of β2AR to Gαq. We observed that the residues Q384(s-pep)/L349(q-pep) (H5.16) make sustained interactions with Q2295.68 (β2AR)/W2445.66 (V1AR), respectively (Fig. 4 B, i and ii). Although Q384(s-pep)/L349(q-pep) interact with residues on TM5 in both β2AR and V1AR, the hydrophilic interaction pair in β2AR:s-pep is swapped to a hydrophobic interaction pair in V1AR:q-pep (Fig. 4 B, i and ii), suggesting that this interaction pair could be a selectivity filter. To further strengthen the binding and coupling of Gαq to β2AR in the TM5 region, we proposed the double mutant R228I5.67−Q229W5.68. The C terminus residue E392H5.24 orients the s-pep toward the basic residue patch K2706.33, R3287.55, and R3338.51 located between TM6 and TM7. The E355H5.22 residue in q-pep orients the C terminus toward ICL1/TM2, interacting with R81ICL1, K82ICL1, T83ICL1, S842.37, and R852.38 in V1AR. From the MD simulation analysis, we observe that the dynamics of noncognate β2AR:q-pep complex samples a finite but small population of the conformation similar to that of the cognate V1AR:q-pep interaction. This guides our hypothesis that GPCRs may couple to different Gα proteins with different interfaces, but the interfaces for the noncognate G proteins could be latent cavities with weak interactions. We predicted that mutations of the β2AR TM5 interface that mimic V1AR may stabilize the short-lived V1AR:q-pep−like orientation observed in β2AR:q-pep. We expressed and tested a β2AR−R228I5.67−Q229W5.68 (β2AR-DM) construct which produced an IP-1 signal about threefold greater than WT β2AR (Fig. 5 A, Left). We also measured cAMP activity from the double-mutant construct, which showed a nonsignificant reduction in the Gαs pathway activity (Fig. 5 A, Right). This result suggests that the β2AR-DM does complex with Gαq protein, and also with Gαs but with less coupling strength.

Fig. 5.

Tuning the Gαq latent cavity in β2AR generates a promiscuous signaling receptor. (A) Secondary messengers IP-1 and cAMP production in cells showing that the triple-mutant β2AR–Q142K–R228I–Q229W and double-mutant β2AR–R228I–Q229W efficiently couples to both Gαq and Gαs in the cell. Significance is denoted as *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. (B) Dose–response curves for WT β2AR and triple mutant (β2AR–Q142K–R228I–Q229W) denoted as TM in this figure for brevity. IP-1 dose response curve for WT (circle markers) vs. triple mutant (square markers). EC50 values were calculated for each replicate (n = 3) and the mean values for IP-1 EC50 ± SEM are reported on the graph for WT (circles; mean EC50: 2.97 μM ± 2.6) and triple mutant (squares; mean EC50: 17.00 nM ± 3.4). cAMP dose–response curve for WT (circles) vs. triple mutant (squares). EC50 values were calculated for each replicate (n = 4) and the mean values for cAMP EC50 ± SEM are reported on the graph for WT (circles; mean EC50: 0.28 nM ± 0.1) and triple mutant (squares; mean EC50: 55.13 nM ± 19.4). (C) Model showing that GPCRs have latent cavities to fit Gαs, Gαi and Gαq proteins. A Gαs-coupled receptor shows a deep attractive binding cavity for s-pep, while the latent binding cavities of Gαq and Gαi are shallow. Engineering the appropriate mutations, predicted from MD simulations, reshapes the IC surface in triple-mutant β2AR, making it promiscuous to Gαs, Gαi, and Gαq.

MD simulations of the q-pep bound to β2AR-DM:q-pep were started from a Gαq-like and Gαs-like orientation. Results show favorable interaction in the Gαq-like orientation (Fig. 4 B, iii), with E355H5.22 of q-pep stably binding to Q14234.54 in β2AR-DM. We predicted that a third mutation of Q14234.54 to lysine in β2AR-DM would further strengthen the q-pep interaction with β2AR in Gαq-like orientation. As predicted, the triple mutant β2AR−Q142K34.54−R228I5.67−Q229W5.68 simulations showed q-pep binding in a similar interface to q-pep in V1AR:q-pep (Fig. 4 B, iv). Agonist-induced IP-1 production significantly increased in the triple mutant compared with WT β2AR (Fig. 5 A, Left). Measurement of agonist-induced cAMP showed a significant reduction in the triple mutant compared with WT β2AR (Fig. 5 A, Right). We tested whether Gαi signaling played a role in this decreased cAMP activity, but assays suggest this effect is insensitive to pertussis toxin (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C). Additionally, the dynamics of the triple mutant β2AR:s-pep does not show lowering in s-pep binding (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). We observe E2255.64 in the triple-mutant β2AR complementing the Q384H5.16, and the E392H5.24 hotspot shows orientation to the TM6/TM7 region where it maintains contact with K2706.32, R3287.55, and R3338.51. Dose–response curves reveal how the triple mutation in β2AR affects the potency and efficacy for the Gαq and Gαs interactions. For the Gαq pathway, we observe a reduction in the EC50 of isoproterenol from 2.97 μM to 17.00 nM in the production of IP-1 by the β2AR triple mutant, and approximately fourfold increase in overall efficacy (Fig. 5 B, Left). In the Gαs pathway, the EC50 of isoproterenol for cAMP production increased from 0.28 nM in the WT to 55.13 nM in the triple mutant, with approximately threefold reduction in overall efficacy (Fig. 5 B, Right).

We summarize the results from these data in a model (Fig. 5C). We propose that GPCRs have latent cavities within their IC surface to bind different G proteins. The cavity in which the cognate G protein binds is attractive, with enthalpically favorable hotspots that lower the entropy of the complex and stabilize the agonist-bound GPCR interaction with the cognate G protein. Although GPCRs possess latent cavities for noncognate G proteins, the cavities are dynamic and unable to stabilize the noncognate G proteins, since they lack affinity. Promiscuous GPCRs have hotspot residues in the respective G-protein binding cavities that make them attractive to multiple G proteins. We note that possible selectivity hotspots outside of the Gα-protein C terminus have not been probed in this study.

Dynamic Reshaping of the IC Cavity in β2AR.

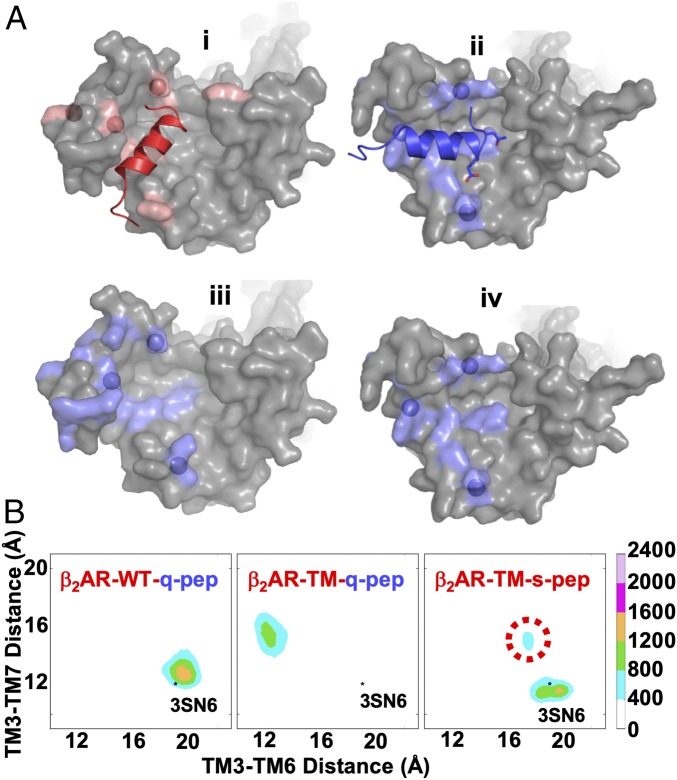

MD results suggest that the triple-mutant undergoes dynamic reshaping of the IC cavity to bind both Gαs and Gαq proteins. MD simulations of the triple-mutant β2AR coupled to s-pep and q-pep started from both Gαs-like and Gαq-like orientations revealed s-pep only binds in the Gαs-like cavity, and q-pep only binds in the Gαq-like cavity (Fig. 6 A, i and ii). The Gαs-interacting hotspots are shown as salmon-colored surface and span TM5, TM6, and TM7 and helix 8, with strongest interacting residues shown as spheres (Fig. 6 A, i). The residues that make contact with the q-pep are shown in blue surface, with the strongest interacting positions shown as blue spheres (Fig. 6 A, ii). The Gαq-interacting residues projected on the IC surface of s-pep−bound WT β2AR show that Gαq-interacting residues are spread out and form a dispersed cavity when Gαs is bound (Fig. 6 A, iii). In the triple-mutant, the IC surface reshapes and positions the Gαq-interacting residues into a trident-like pattern spanning the IC portions of TM3, TM5, and TM6 and ICL1 and ICL2 (Fig. 6 A, iv). We projected this dynamic cavity on the interresidue distances between TM3 and TM6 and between TM3 and TM7, and we observe that WT β2AR:q-pep samples a β2AR cavity similar to the Gαs-bound crystal structure. This suggests that the lack of q-pep stabilizing hotspots prevents the stabilization of the β2AR conformation observed in the triple-mutant complex wth q-pep (Fig. 6 B, Left). The q-pep interaction in the triple mutant shows a very distinct conformation, with a narrower cavity between TM3 and TM6 and a slightly wider cavity between TM3 and TM7. This shrinking of the TM3 to TM6 distance is similar to that observed in the interaction of WT β2AR with the Gαi protein in previous MD simulations (51). The β2AR conformation sampled by the triple mutant with s-pep is similar to that sampled by WT β2AR:s-pep (Fig. 2B), but the most populated conformational cluster shifts to a smaller TM3 to TM7 distance compared with WT β2AR.

Fig. 6.

Dynamic reshaping of the Gαq cavity in a Gαs-coupled receptor mutant: making β2AR promiscuous toward Gαq and Gαs. (A) (i) The IC surface rendering of WT β2AR with the residues involved in binding of s-pep shown in red surface. The bright red spheres are the residues that interact strongly with the s-pep. (ii) MD simulations of the triple-mutant β2AR–Q142K–R228I–Q229W (denoted as β2AR-TM in the figure for brevity) shows formation of a favorable Gαq-like cavity with q-peptide wedged. (iii) This is the surface of the residues shown in ii when projected on the IC surface of WT β2AR. This surface shows that the residues that should form a favorable cavity for Gαq are spread out in the WT β2AR. (iv) MD simulations of the double mutant of β2AR show reshaping of these residues in iii to form a “trident”-like pattern. These are representative snapshots taken from the most populated conformation cluster from the MD simulations. (B) Ensemble of conformations from MD simulations projected on the interresidue distances between TM3 and TM6 (distance between Cα atoms of residues 3.50 and 6.30) and between TM3 and TM7 (distance between Cα atoms of 7.53 and 3.50) for WT β2AR with q-pep (Left), β2AR triple mutant with q-pep (Center), and β2AR triple mutant with s-pep (Right).

Discussion

The 3D structures of GPCR−G-protein complexes predominantly inform us on how cognate G proteins interact with GPCRs in the nucleotide-free state. The dynamics of the agonist-bound GPCR has been well characterized by spectroscopic and computational studies (30–32, 52–55). However, the dynamics of the GPCRs with their cognate and, especially, noncognate G proteins is poorly understood, despite their relevance in cellular conditions (1, 5). Our study combining MD simulations and FRET sensor measurements has yielded the following conceptual advancements: 1) Agonist-bound and G-protein−bound GPCRs contain multiple latent IC cavities, which were not formerly characterized. The cognate and noncognate G proteins interact dynamically with their latent cavities with varying strengths. 2) The C terminus of Gαs, Gαi, and Gαq proteins assume a small ensemble of unique orientations when coupled to their cognate GPCRs. This ensemble explains the variations observed in the coupling strengths of the same G protein to different GPCRs. 3) Engineering the latent cavities with hotspots to the noncognate G proteins tunes the promiscuity of the GPCR. Using the hotspot residues identified for coupling of Gαs, Gαi, and Gαq proteins to their respective cognate GPCRs, we have tuned a latent Gαq-binding cavity in β2AR to additionally bind and signal through Gαq. This promiscuous triple mutant β2AR demonstrates the tunability of G-protein selectivity in GPCRs.

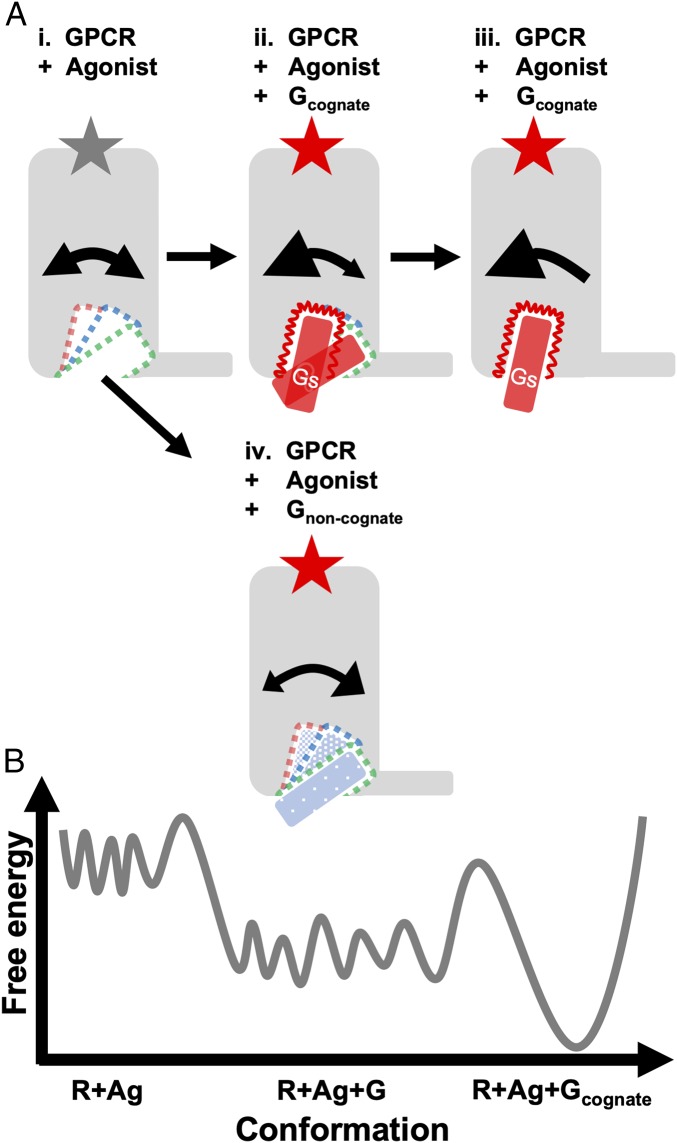

G-protein selectivity likely arises from 1) several kinetic steps involved in going from engaging the G protein in the GDP-bound state and transitioning to the nucleotide-free state and 2) the relative thermodynamic stabilities of various conformational states involved in these kinetic steps (56). Our study probes the relative thermodynamic stabilities of the agonist−GPCR−Gα-peptide complexes for the cognate and noncognate Gα peptides in the presence of the same agonist. Previous studies showed that agonist binding results in increased conformational heterogeneity (30–32, 57) in β2AR (R+Ag; Fig. 7B). Pushing this further, our study shows that G-protein insertion, be it cognate or noncognate, leads to dynamic conformational heterogeneity in the GPCR IC cavity (R+Ag+G) and to a moderate entropic stabilization (Fig. 7B). Importantly, the GPCR cytosolic pocket continues to exhibit a high degree of structural plasticity, and the cognate G protein reduces the entropy of residues in the GPCR cavity (Fig. 2A), stabilizing the receptor and enabling it to clamp down on the Gα C terminus (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). The presence of enthalpically favorable intermolecular contacts between the cognate G protein and its preferred cavity leads to full complexation and productive signaling (Fig. 7 A, iii and Fig. 7B). In contrast, the weak interactions between the GPCR cavity and noncognate G proteins result in the dissociation of Gα C terminus without productive complexation and signaling (Fig. 7 A, iv). Incorporation of single G-protein−selective residues in the latent cavities, whether by evolution or engineering, is sufficient to reshape the GPCR IC surface for productive coupling with the noncognate G proteins. We hypothesize that promiscuously coupling GPCRs evolved to make these latent cavities highly attractive, while selective GPCRs are under evolutionary pressure to optimize the affinity between one cognate G protein and cavity.

Fig. 7.

The Goldilocks Effect: Cognate peptides fit “just right” for productive activation and signaling. (A) A model of the dynamics of the GPCR IC cavity and the C terminus of the Gα proteins, cognate and noncognate, complexed with an agonist-bound GPCR. Double-sided curved arrows are drawn to show (i) balanced dynamic movement of GPCR TM bundle and Gα C terminus between the dominant and latent cavities in the IC interface during the apo state, (ii) or skewed toward the dominant cavity upon initial complexation with cognate G protein, and (iv) skewed to the latent cavity upon complexing with a noncognate G protein. (iii) Strong, unidirectional arrows reveal stabilization of the dominant cavity during G-protein activation. (B) Schematic free-energy landscape describes the relative stability of the GPCR during agonist binding, transient interaction with G proteins, and full complexation with a cognate G protein.

One of the caveats of this study is our focus on only the C terminus of the G protein. The Gα C terminus is a known determinant of G-protein selectivity, and it has long been established that swapping the last three amino acids between the Gαi and Gαq isoforms is sufficient to confer promiscuous signaling from chimeric G proteins in HEK293 cells (28). Our focus on GPCR−Gα C terminus interactions prevents confounding effects from the integration of signaling downstream of endogenous and chimeric G proteins. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that other regions are likely involved in G-protein selectivity. Another caveat is that many of our MD simulations were started from a homology model of the receptor−Gα-peptide complex. The accuracy of our dynamics and hotspot predictions will be enhanced as more structures of the GPCR−G-protein complexes emerge in literature.

This study fills the knowledge gap in linking the dynamics of ligand−GPCR complexes to the dynamics of G-protein coupling and provides a framework to interpret variance in the strength of interaction between different GPCRs and G proteins.

Materials and Methods

Modeling of the GPCRs and Agonists.

The summarized modeling details are given in SI Appendix, Table S1. Structures of the GPCRs studied were modeled based on homology to either β2AR, μOR, or CB1R templates. The models were then aligned to the active states of β2AR or Rhodopsin in the 3SN6 and 4J4Q PDB structures. Gα peptides were modeled using the α5 helix of Gαs in 3SN6, and then aligned to the α5 helix of Gαs or transducin in 3SN6 and 4J4Q. Structures were minimized using the MacroModel [Schrӧdinger Release 2015-4: MacroModel (2015); Schrӧdinger, LLC] application before simulation with Groningen Machine for Chemical Simulations (GROMACS). For more details, please see SI Appendix.

Details of MD Simulations.

MD simulations were performed in explicit POPC lipid bilayer and water using gromos 53a6 force field and following a standard protocol for GPCRs used in our laboratory (29). Details are in SI Appendix.

Computational Data Analysis.

One-microsecond ensemble trajectories were used for analyzing intermolecular contacts and interaction energies for GPCR−peptide pairs. Individual energies were calculated for each amino acid of the Gα peptides with the entire GPCR using the GROMACS “energy” application. The total nonbond energy from short-range (within 12 Å) coulombic and van der Waals forces was extracted from an energy log file and summed for the total nonbond interaction energy. Gα-peptide residues showing above-average interaction energy (Fig. 3A) are considered critical residues and potential “hotspots.” Intermolecular contacts were calculated in Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) using Tcl scripts to identify the frequency of pairwise interactions within 5 Å between peptides and receptors. Contacts made with greater than or equal to 50% frequency were deemed critical contacts. Peptide residues deemed “critical” from both interaction energy and intermolecular contact analysis were strongly considered for their role as “hotspots” for G-protein selectivity.

Calculation of first-order torsional entropy.

The first-order torsional entropy of the G-protein interacting residues shown in Fig. 2A was calculated using methods developed in-house (30). Further details of this analysis can be found in SI Appendix.

Calculation of the insertion angles of the G protein.

We measured the angle between the principal axis of the helical portion of the Gα peptide (H5.13-H5.23) and the principal axis of the GPCR TM bundle, for each frame of the trajectory. The angle θ was calculated from the dot product of these vectors using a⋅b = ‖a‖‖b‖cosθ.

Calculation of GPCR IC cavity width and active-state complex metrics.

To measure the conformational flexibility in the IC cavity of the receptor, we measured the distance between Cα atoms of the residues 3.50 and 6.30 for each receptor (numbers shown using Ballesteros−Weinstein numbering system). The distance between the residues in this pair is used as a standard indicator of receptor activation state (46). We also measured the distance between the Cα atoms of the residues 3.50 and 7.53 as another indication of receptor activation state.

Conformational clustering method.

RMSD clustering in coordinates was used to determine the number of conformational clusters sampled by Gα peptides within the 1-μs ensemble of simulations. Cα atoms from the GPCR TMs were aligned for the least-squares fit to serve as a frame of reference for comparing peptide orientations based on the backbone atoms of Gα-peptide positions H5.12 to H5.26. The aligned Gα-peptide conformations were clustered using the “gromos” method in the GROMACS “cluster” application, with a cutoff of 2 Å (58). This procedure identifies the centroid with the largest number of neighboring structures within the cutoff distance and sorts them to a unique cluster, repeating the same procedure with the remaining, unsorted structures.

Statistical analysis.

The mean ± SEM was determined from each of five 200-ns replicates of the 1-µs ensemble trajectory. Means were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s posttest to assess significance for multiple comparisons, using GraphPad Prism version 7.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, https://www.graphpad.com) (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). The Kolmogorov−Smirnov test statistic was calculated for each distribution of GPCR IC cavity width (TM3 to TM6 distances), to compare the variance of each distribution (59). The sample size of the distribution was calculated as 50,000 frames. Each comparison rejected the null hypothesis, and P values were too small to be calculated, due to limitations of machine precision (limited to 2.2 × 10−16), but all P values for each comparison were significantly less than 1.0 × 10−4 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B and Table S3).

Experimental Methods

Experiments were conducted similarly to procedures outlined in our previous study (29). Details of “Reagents and buffers,” “Molecular cloning,” and “Mammalian cell preparation and sensor expression” are found in SI Appendix.

cAMP Assays.

HEK293T-Flp-in cells were transiently transfected (XtremeGENE HP) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Where indicated, 10 h after transfection, cells were incubated with 100 ng⋅mL−1 pertussis toxin (PTX) for 20 h. Between 28 h and 32 h posttransfection, (XtremeGENE HP) HEK293T cells expressing indicated sensor were harvested to assess cAMP levels using the bioluminescent cAMP Glo assay (Promega). Cells were gently suspended in their original media, were counted using a hemocytometer, and were spun down (350 × g, 3 min). Cells were resuspended in an appropriate volume of PBS (pH 7.4; Gibco) supplemented with 800 μM ascorbic acid and 0.2% dextrose (wt/vol) to reach 4 × 106 cells/mL density. Cell suspensions were aliquoted into 384-well opaque plates. To assess Emax for cAMP production, cells were incubated with 100 μM of isoproterenol for 15 min at 37 °C. For dose–response curves, cells were incubated under the same conditions with a range of isoproterenol concentrations from 100 fM to 100 μM. Subsequently, cells were lysed and the protocol was followed according to the manufacturer’s recommendation (Promega). Luminescence was measured using a microplate luminometer reader (SpectraMax M5e; Molecular Devices). The cAMP levels (relative luminescence unit) were evaluated by subtracting the isoproterenol conditions from the untreated conditions. Each experiment had four technical repeats per condition and was independently repeated at least three times (n > 3). To obtain EC50 and Emax, dose–response data were fit to a sigmoidal dose–response equation using nonlinear least-squares regression.

IP-1 Assays.

At 28 h to 32 h posttransfection, (XtremeGENE HP) HEK293T cells expressing the indicated sensor were harvested to assess IP-1 levels using the IP-One HTRF assay kit (Cisbio). Cells were gently suspended in their original media, counted using a hemocytometer, and spun down (350 × g, 3 min). An appropriate volume of StimB buffer (CisBio: 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 4.2 mM KCl, 146 mM NaCl, 5.5 mM glucose, 50 mM LiCl, pH 7.4) was added to reach 3 × 106 cells/mL density. Cells were incubated with 100 μM isoproterenol at 37 °C for 120 min. For dose–response curves, cells were incubated under the same conditions with a range of isoproterenol concentrations from 100 fM to 100 μM. Following the manufacturer’s protocol, each reaction suspension was then incubated for 1 h shaking (500 rpm) at room temperature with 15 μL of IP-1 conjugated to d2 dye and 15 μL of terbium cryptate-labeled anti−IP-1 monoclonal antibody prepared and stored as recommended by the manufacturer. IP-1 FRET spectra were collected by exciting samples at 340 nm (band-pass 15 nm). Emission counts were recorded from 600 nm to 700 nm (band-pass 10 nm) using a long-pass 475-nm filter (FSQ GG475; Newport). Raw IP-1 signal was calculated from the 665 nm to 620 nm ratio. Data are presented as a change in raw IP-1 ratio following drug treatment. Each experiment had four repeats per condition and was independently repeated at least three times (n > 3). To obtain EC50 and Emax, dose–response data were fit to a sigmoidal dose–response equation using nonlinear least-squares regression. Compared with the cAMP data, the IP-1 data were better explained by fitting to a dose–response model (∑Residuals2 = 0.01) than by fitting to a linear model (∑Residuals2 = 0.05).

Statistical Analysis.

Data are expressed as mean values ± SEM. Experiments were independently conducted at least three times, with three to six technical repeats per condition (n > 3). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0c (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Statistical significance was performed for individual experiments using paired Student’s t test. To assess how the data varied across experimental repeats, data were pooled, and paired or unpaired Student’s t tests were conducted to evaluate significance. One-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s posttest was performed to assess significance when evaluating comparisons between multiple conditions (Figs. 3B and 5A) with P values *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; and ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research in this publication is supported by Grant NIH-R01GM117923 (to N.V. and S.S.) and Maximizing Investigator Research Award Grant NIH-R35GM126940 (to S.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1820944116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Masuho I., et al. , Distinct profiles of functional discrimination among G proteins determine the actions of G protein-coupled receptors. Sci. Signal. 8, ra123 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Namkung Y., et al. , Functional selectivity profiling of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor using pathway-wide BRET signaling sensors. Sci. Signal 11, eaat1631 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mende F., et al. , Translating biased signaling in the ghrelin receptor system into differential in vivo functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E10255–E10264 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namkung Y., et al. , Quantifying biased signaling in GPCRs using BRET-based biosensors. Methods 92, 5–10 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neubig R. R. Membrane organization in G-protein mechanisms. FASEB J. 8, 939–946 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenzel-Seifert K., Seifert R., Molecular analysis of β2-adrenoceptor coupling to Gs-, Gi-, and Gq-proteins. Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 954–966 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stallaert W., Dorn J. F., van der Westhuizen E., Audet M., Bouvier M., Impedance responses reveal β2-adrenergic receptor signaling pluridimensionality and allow classification of ligands with distinct signaling profiles. PLoS One 7, e29420 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou L., et al. , Functional selectivity of GPCR signaling in animals. J. Biol. Chem. 109, 7809–7820 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Picard L.-P., Schönegge A. M., Lohse M. J., Bouvier M.. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer-based biosensors allow monitoring of ligand- and transducer-mediated GPCR conformational changes. Commun. Biol. 1, 106 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen S. G. F., et al. , Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature 477, 549–555 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter B., Nehmé R., Warne T., Leslie A. G. W., Tate C. G., Erratum: Structure of the adenosine A2A receptor bound to an engineered G protein. Nature 538, 542 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Draper-Joyce C. J., et al. , Structure of the adenosine-bound human adenosine A1 receptor-Gi complex. Nature 558, 559–563 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-Nafría J., Nehmé R., Edwards P. C., Tate C. G., Cryo-EM structure of the serotonin 5-HT1B receptor coupled to heterotrimeric Go. Nature 558, 620–623 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang Y., et al. , Cryo-EM structure of human rhodopsin bound to an inhibitory G protein. Nature 558, 553–558 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koehl A., et al. , Structure of the µ-opioid receptor-Gi protein complex. Nature 558, 547–552 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishna Kumar K., et al. , Structure of a signaling cannabinoid receptor 1-G protein complex. Cell 176, 448–458.e12 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flock T., et al. , Universal allosteric mechanism for Gα activation by GPCRs. Nature 524, 173–179 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flock T., et al. , Selectivity determinants of GPCR-G-protein binding. Nature 545, 317–322 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong S. K., Ross E. M., Chimeric muscarinic cholinergic:beta-adrenergic receptors that are functionally promiscuous among G proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 18968–18976 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong S. K., G protein selectivity is regulated by multiple intracellular regions of GPCRs. Neurosignals 12, 1–12 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kostenis E., Conklin B. R., Wess J., Molecular basis of receptor/G protein coupling selectivity studied by coexpression of wild type and mutant m2 muscarinic receptors with mutant G αq subunits. Biochemistry 36, 1487–1495 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wess J., Molecular basis of receptor/G-protein-coupling selectivity. Pharmacol. Ther. 80, 231–264 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wess J., Brann M. R., Bonner T. I., Identification of a small intracellular region of the muscarinic m3 receptor as a determinant of selective coupling to PI turnover. FEBS Lett. 258, 133–136 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conklin B. R., Farfel Z., Lustig K. D., Julius D., Bourne H. R., Substitution of three amino acids switches receptor specificity of Gq α to that of Gi α. Nature 363, 274–276 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kostenis E., Degtyarev M. Y., Conklin B. R., Wess J., The N-terminal extension of Galphaq is critical for constraining the selectivity of receptor coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 19107–19110 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang C.-S. S., Skiba N. P., Mazzoni M. R., Hamm H. E., Conformational changes at the carboxyl terminus of Galpha occur during G protein activation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2379–2385 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Eps N., Oldham W. M., Hamm H. E., Hubbell W. L., Structural and dynamical changes in an α-subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein along the activation pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16194–16199 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaya A. I., et al. , A conserved phenylalanine as a relay between the α5 helix and the GDP binding region of heterotrimeric Gi protein α subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 24475–24487 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Semack A., Sandhu M., Malik R. U., Vaidehi N., Sivaramakrishnan S., Structural elements in the Gαs and Gαq C termini that mediate selective G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 17929–17940 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niesen M. J., Bhattacharya S., Vaidehi N., The role of conformational ensembles in ligand recognition in G-protein coupled receptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13197–13204 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nygaard R., et al. , The dynamic process of β2-adrenergic receptor activation. Cell 152, 532–542 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manglik A., et al. , Structural insights into the dynamic process of β2-adrenergic receptor signaling. Cell 161, 1101–1111 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maguire M. E., Van Arsdale P. M., Gilman A. G., An agonist-specific effect of guanine nucleotides on binding to the beta adrenergic receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 12, 335–339 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeVree B. T., et al. , Allosteric coupling from G protein to the agonist-binding pocket in GPCRs. Nature 535, 182–186 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee S., Nivedha A. K., Tate C. G., Vaidehi N., Dynamic role of the G protein in stabilizing the active state of the adenosine A2A receptor. Structure 27, 703–712.e3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sivaramakrishnan S., Spudich J. A., Systematic control of protein interaction using a modular ER/K α-helix linker. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20467–20472 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malik R. U., et al. , Detection of G protein-selective G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) conformations in live cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 17167–17178 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Semack A., Malik R. U., Sivaramakrishnan S., G protein-selective GPCR conformations measured using FRET sensors in a live cell suspension fluorometer assay. J. Vis. Exp., 115 e54696 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnstone E. K. M., Pfleger K. D. G., “Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer approaches to discover bias in GPCR signaling” in G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Drug Discovery, Filizola M., Ed. (Springer, 2015), pp. 191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maziarz M., Garcia-Marcos M., Rapid kinetic BRET measurements to monitor G protein activation by GPCR and non-GPCR proteins. Methods Cell Biol. 142, 145–157 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupte T. M., Malik R. U., Sommese R. F., Ritt M., Sivaramakrishnan S., Priming GPCR signaling through the synergistic effect of two G proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 3756–3761 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kenakin T. Functional selectivity and biased receptor signaling. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 336, 296–302 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sunahara R. K., Tesmer J. J., Gilman A. G., Sprang S. R., Crystal structure of the adenylyl cyclase activator Gsα. Science 278, 1943–1947 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung K. Y., et al. , Conformational changes in the G protein Gs induced by the β2 adrenergic receptor. Nature 477, 611–615 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eichel K., von Zastrow M., Subcellular organization of GPCR signaling. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 39, 200–208 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farrens D. L., Altenbach C., Yang K., Hubbell W. L., Khorana H. G., Requirement of rigid-body motion of transmembrane helices for light activation of rhodopsin. Science 274, 768–770 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ballesteros J. A., Weinstein H., “Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors” in Methods in Neurosciences, Sealfon S. C., Ed. (Academic, 1995), Vol. 25, pp. 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perez D. M., DeYoung M. B., Graham R. M., Coupling of expressed α 1B- and α 1D-adrenergic receptor to multiple signaling pathways is both G protein and cell type specific. Mol. Pharmacol. 44, 784–795 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prioleau C., Visiers I., Ebersole B. J., Weinstein H., Sealfon S. C., Conserved helix 7 tyrosine acts as a multistate conformational switch in the 5HT2C receptor. Identification of a novel “locked-on” phenotype and double revertant mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 36577–36584 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fritze O., et al. , Role of the conserved NPxxYx5,6F motif in the rhodopsin ground state and during activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2290–2295 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rose A. S., et al. , Position of transmembrane helix 6 determines receptor G protein coupling specificity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 11244–11247 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swaminath G., et al. , Sequential binding of agonists to the β2 adrenoceptor. Kinetic evidence for intermediate conformational states. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 686–691 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhattacharya S., Vaidehi N., Computational mapping of the conformational transitions in agonist selective pathways of a G-protein coupled receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5205–5214 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vaidehi N., Kenakin T., The role of conformational ensembles of seven transmembrane receptors in functional selectivity. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 10, 775–781 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim T. H., et al. , The role of ligands on the equilibria between functional states of a G protein-coupled receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9465–9474 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gregorio G. G., et al. , Single-molecule analysis of ligand efficacy in β2AR-G-protein activation. Nature 547, 68–73 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhattacharya S., Vaidehi N., Differences in allosteric communication pipelines in the inactive and active states of a GPCR. Biophys. J. 107, 422–434 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daura X., et al. , Peptide folding: When simulation meets experiment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38, 236–240 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pedregosa F., et al. , Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.