Abstract

Objective

To determine the potential differences in both scapular positioning and scapular movement between the symptomatic and asymptomatic contralateral shoulder, in patients with unilateral subacromial pain syndrome (SAPS), and when compared with participants free of shoulder pain.

Setting

Three different primary care centres.

Participants

A sample of 73 patients with SAPS in their dominant arm was recruited, with a final sample size of 54 participants.

Primary outcome measures

The scapular upward rotation (SUR), the pectoralis minor and the levator scapulae muscles length tests were carried out.

Results

When symptomatic shoulders and controls were compared, an increased SUR at all positions (45°, 90° and 135°) was obtained in symptomatic shoulders (2/3,98/8,96°, respectively). These differences in SUR surpassed the minimal detectable change (MDC95) (0,91/1,55/2,83° at 45/90/135° of shoulder elevation). No differences were found in SUR between symptomatic and contralateral shoulders. No differences were found in either pectoralis minor or levator scapulae muscle length in all groups.

Conclusions

SUR was greater in patients with chronic SAPS compared with controls at different angles of shoulder elevation.

Keywords: scapular kinematic, shoulder pain, chronic pain

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An exhaustive ultrasound and clinical assessment was carried out to avoid the inclusion of patients with rotator cuff tears.

The examiner who assessed all the measurements was an experienced clinical professional.

The inter-rater reliability was not calculated, so this could introduce bias.

The minimal clinically important difference for scapular upward rotation is unknown, thus we cannot make a conclusion as to whether the differences found in this study reached clinical importance or not.

Introduction

Shoulder pain is the most common musculoskeletal condition after neck pain and low back pain.1 Shoulder pain point prevalence figures range from 6.9% to 26%, from 18.6% to 31% for 1 month prevalence, from 4.7% to 46.7% for 1 year prevalence and from 6.7% to 66.7% for lifetime prevalence.2 Furthermore, shoulder pain prevalence is even higher in women,3 in the working population4 and increases with age.5

Subacromial pain syndrome (SAPS) is the most common cause of shoulder pain.6 7 It is defined as a non-traumatic, usually unilateral, shoulder disorder that causes localised pain around the acromion, often worsening during or subsequent lifting the arm.8 The best therapeutic approach in SAPS is still under debate. Half of the patients with shoulder pain being attended in primary care do not completely recover after 6 months from their initial episode.9 Thus, there is a need to explore different non-invasive strategies in these patients. One of the approaches that can be beneficial for the patient is to focus on the scapulothoracic joint. To date, there is inconsistent evidence to support a relationship between SAPS symptoms and scapular orientation.6 10 The most common causative mechanism of an altered scapular positioning involves the soft tissue, such as inflexibility (tightness) and alterations in the periscapular muscles.11 Specifically, both a decreased activation and strength of the serratus anterior, as well as alterations in upper/lower trapezius couple forces, can alter scapular upward rotation (SUR) and posterior tilt.11 Likewise, pectoralis minor, levator scapulae muscles12 13 and biceps short head11 have been traditionally assessed as their shortening may potentially influence scapular positioning.

Previous studies have reported normative values on pectoralis minor length in the dominant and non-dominant side in both symptomatic and control populations, by using the Pectoralis Minor Index (PMI)14 and the acromion-table distance test.15 Recently, pectoralis minor length and its shortening have received remarkable empirical attention, in terms of studies of its reliability,16 its association with shoulder external rotation,17 and as an outcome measure after a stretching programme in participants with shoulder pain.18 However, differences between symptomatic groups and healthy controls were not calculated. To the best of our knowledge, differences in the Levator Scapulae Index (LSI) between symptomatic and control populations have not been determined yet. With regard to patterns of movement, there is conflicting evidence. While some studies have shown association between a reduced SUR and scapular posterior tilt in SAPS,19 20 others attained inconclusive findings.6 10

Advanced equipment exists to assess scapular positioning and kinematics. However, most of them are very technical and highly expensive, which makes them almost unattainable in the clinical practice.21 In this regard, research states that the SUR seems suitably evidence based for clinical use, while pectoralis minor length measurements should be used as supplementary clinical assessment methods in addition to others.22 23 Additionally, the levator scapulae muscle length measurement has been shown to be a reliable tool, and it has been proposed as part of the scapula assessment because the levator scapulae directly attaches in the superior angle of the scapula13 and thus it is another possible cause of scapular dysfunction.24

Specifically, there is a lack of evidence on the potential differences in PMI, LSI and SUR, between painful and contralateral non-painful shoulders, and control subjects. The existence of differences in scapular positioning and pattern of movement could contribute to steer physiotherapy treatments towards a scapular focused treatment approach.

Hence, the aim of this study was to analyse the differences in scapular positioning and pattern of movement, between the symptomatic and asymptomatic shoulder, in patients with unilateral chronic SAPS, and in controls, using three different tests: (1) SUR, (2) pectoralis minor muscle length and (3) levator scapulae muscle length. The null hypothesis (H0) was that there are no differences in the groups in these three different tests. The alternative hypothesis (Ha) was that there is an increased SUR in painful shoulder when comparing with contralateral and control shoulder, as well as a decreased both pectoralis minor and levator scapulae length in painful shoulder.

Method

Study design

This was a cross-sectional, observational study, carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study has been reported following the recommendations of the STROBE statement for observational studies.

Participants

A sample of 73 patients with chronic SAPS in their dominant arm was recruited from three different primary care centres, with a final sample size of 54 participants obtained after applying the inclusion criteria. General practitioners recruited the participants who were screened for eligibility by a research assistant. Participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) men or women aged between 18 and 55 years; (2) unilateral pain located in the anterior and/or lateral shoulder region8; (3) two out of three positive clinical tests (Hawkins-Kennedy; Jobe; Neer)25; (4) pain with normal activity ≥4/10 on a visual analogue scale; (5) shoulder pain lasting more than 3 months; (6) a history of non-traumatic onset of shoulder pain. Participants were ineligible to participate in this study if any of these conditions were present: (1) history of significant shoulder trauma, such as fracture or ultrasonography-clinically suspected full thickness cuff tear, following the classification of Wiener and Seitz, 199326; (2) recent shoulder dislocation in the past 2 years; (3) systemic illnesses such as rheumatoid arthritis; (4) adhesive capsulitis; (5) shoulder pain originating from the neck or if there was a neurological impairment, osteoporosis, haemophilia and/or malignancies.

A sample of 40 participants with both shoulders free of pain for the last year was selected. They were recruited from the same three primary care centres as the participants with shoulder pain. Furthermore, to participate in the study, they had to present: (1) a Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) score ≤15 points, based on the minimal clinically detectable change for this tool27; (2) negative results for Neer test, Hawkins-Kennedy test and Jobe test; (3) no painful arc present during flexion or abduction; (4) no pain during resisted lateral rotation and/or abduction. Asymptomatic participants were specifically age and gender matched to the symptomatic group.

Outcome measurements

All measurements were taken by a physiotherapist with more than 25 years of experience, including height which was necessary to calculate PMI and LSI values. This physiotherapist was blinded to the fact of participants having shoulder pain or not.

Scapular upward rotation

The measurement of SUR was performed using two Plurimeter-V gravity reference inclinometers.28 One inclinometer was Velcro taped perpendicular to the humeral shaft, just above the humeral epicondyle. At resting position, the humeral inclinometer was calibrated as 0°. Next, the patients were instructed to perform shoulder abduction in the coronal plane with full elbow extension and 45° of external humeral rotation, with the thumb abducted. The patients were asked to stop at 45°, 90° and 135° of humeral abduction, where the SUR was measured with a second inclinometer, manually aligned along the scapular spine (figure 1). Three measurements were collected at each position and then the mean was obtained. The arm was repositioned between measurements.

Figure 1.

Scapular upward rotation measurement.

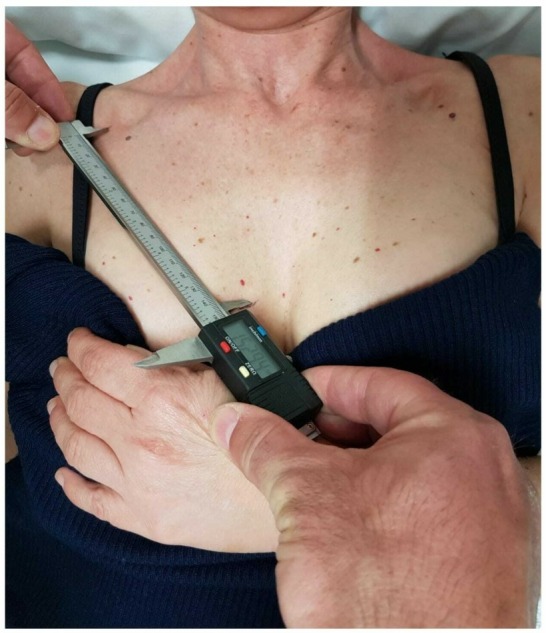

Pectoralis minor length

The measurement of the pectoralis minor length was carried out with the participant in the supine position. A small pillow was placed under the participant’s head for comfort. The participant’s arm was passively placed along the side of the body in the neutral position resting on the table.29 Because of the variability among subjects this measurement was best normalised creating a PMI, which was calculated by dividing the resting muscle length measurement by the subject height and multiplying by 100, as previously described by Borstad et al.12 Height was measured with the patient in a standing position, by using a calliper placed at the top of the head and marking a point on a scale placed on the wall. The resting muscle length was measured from the caudal edge of the fourth rib to the inferomedial aspect of the coracoid process with a sliding calliper (figure 2). PMI values less than 7.65 have been identified as a shortened pectoralis minor, measured in standing position.12 The measurement was taken during inspiration.14

Figure 2.

Pectoralis minor length measurement.

Levator scapulae length

Participants were standing with their arms relaxed at their sides. The subjects were asked to look directly ahead without any craniocervical movement.13 The instruction was to palpate two anatomical reference points in line that represent levator scapulae length: (1) the dorsal tubercles of the transverse processes of the second cervical vertebrae and (2) the superior angle of the medial borders of the scapula. The assessor used a skin-marker pencil to mark the reference points. The marks were cleaned immediately after each test session. The distance between these two bony reference points was measured with a sliding calliper (figure 3). By creating an LSI (levator scapulae length (cm)/subjects' height (cm)*100), the subjects' variability in body height was normalised.13 The LSI was expressed as a percentage of the subjects' height.

Figure 3.

Levator scapulae length measurement.

The SPADI was assessed in all participants. The SPADI is composed of 13 questions and contains two domains: pain and disability. The score of the questionnaire ranges from 0 to 100, with very high scores indicating worse function. The numeric pain scale runs from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no pain and10 representing the worst pain.30 The SPADI has shown a good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95 for the total score, 0.92 for the pain subscale and 0.93 for the disability subscale as well as the ability to detect change over time.31 A Spanish version of the SPADI was used since English was not the native language for all the participants.32

Data analysis

SPSS V.23.0 for Mac was used to analyse the collected data. Normality for all variables was explored using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for the group of participants with shoulder pain (affected and non-affected) and for the control subjects. Two different analysis strategies were carried out: first, to determine differences in SUR at different degrees of abduction, a repeated measures ANOVA was developed in every group. For this analysis, F statistic was adjusted in case of non-sphericity (tested by Mauchly’s test), with the Greenhouse-Geissner correction. Second, to determine between-groups differences for all the outcome measurements, one-way ANOVA test was calculated with Bonferroni and Tukey post-hoc estimations. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The intraclass correlation coefficient was greater than 0.90 for all the tests, which means an excellent reliability,33 except for LSI (0.87). The MDC95 was as follows: SUR45°=0.91; SUR90°=1.55; SUR135°=2.83; PMI=0.80; LSI=1.08.

Patient and public involvement

The participation of all subjects was voluntary, and no incentives were given to encourage enrollment. Patients with shoulder pain from each primary care centre were not involved neither in the design of the study nor in the recruitment of the participants. The results of the present study were sent by e-mail to those participants who wanted to be informed.

Results

Sample characteristics

Demographic characteristics are shown in table 1. There were not significant differences between groups in terms of gender and age.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, mean (SD)

| Patients (mean and SD) (dominant and non dominant shoulder) |

Healthy subjects (mean and SD) (dominant shoulder) |

|

| Age (years; SD) | 46.39 (9.96) | 46.42 (7.02) |

| Women | 33 (61.1%) | 23 (57.5%) |

| Men | 21 (38.9%) | 17 (42.5%) |

| SPADI (CI) | 56.37 (20.01) | 2.66 (2.88) |

| Chronicity of symptoms | 3–6 months: 18 | N/A |

| 6–12 months: 5 | ||

| More than 1 year: 31 |

N/A: non-applicable; SPADI, Shoulder Pain and Disability Index; SD: Standard Deviation.

Mean values for the outcome measures and intrarater reliability data

Mean values of SUR (expressed in degrees), LSI and PMI for all the groups are presented in table 2. There were statistically significant differences in SUR when comparing the three groups, while no differences were found for the rest of the outcome measurements (LSI and PMI) (see table 2). Furthermore, there was an increase in SUR from 45° to 90° and 135° of shoulder abduction for all the groups, analysed by repeated measures ANOVA, with the following results: (1) symptomatic shoulder: F (1,51; 80.05)=1009.22; p<0.001; (2) asymptomatic shoulder: F (1,46; 77.37)=1356.57; p<0.001; (3) healthy controls: F (1,46; 56.89)=1196.18; p<0.001

Table 2.

Mean values (95% CI) of Pectoralis Minor Index (PMI), Levator Scapulae Index (LSI) and scapular upward rotation (SUR) expressed in degrees in different groups; F: one-factor ANOVA for differences in symptomatic, asymptomatic and healthy controls

| Symptomatic shoulder | Asymptomatic shoulder | Healthy controls | F | P values | |

| SUR | |||||

| 45° of GH abduction | 4.55 (3.79–5.32) |

5.71 (4.82–6.60) |

2.55 (1.81–3.29) |

F(2,145)=14.14 | <0.001* |

| 90°of GH abduction | 20.75 (18.81–22.69) |

21.42 (19.88–22.96) |

16.77 (15.49–18.04) |

F(2,145)=8.08 | <0.001* |

| 135° of GH abduction | 45.18 (42.76–47.59) |

44.16 (42.20–46.12) |

36.22 (34.34–38.09) |

F(2,145)=18.64 | <0.001* |

| LSI | 7.81 (7.42–8.20) |

7.81 (7.53–8.30) |

7.76 (7.42–8.11) |

F(2,145)=0.02 | 0.978 |

| PMI | 10.52 (10.27–10.76) |

10.86 (10.26–11.46) |

10.07 (9.73–10.42) |

F(2,145)=2.97 | 0.054 |

Bonferroni post-hoc analysis were carried out.

* S tatistically significant (p<0.01).

Differences in SUR, PMI and LSI between groups

Comparisons between groups are described in detail in table 3. There were statistical significant differences in SUR between symptomatic and control groups at 45°, 90° and 135° of shoulder elevation, while no differences between symptomatic and asymptomatic group were found. There were not statistically significant differences between groups for both PMI and LSI (see table 3).

Table 3.

Between-group differences (Tukey post-hoc analysis)

| Symptomatic vs Asymptomatic shoulder differences (95% CI) | P values | Symptomatic vs Control shoulder differences (95% CI) |

P values | |

| SUR At 45°GH abduction |

− 1.15 (− 2.46 to − 0.15) |

0.09 | 2.01 (0.59 to 3.42) |

0.003* |

| At 90° GH abduction | −0.67 (−3.35 to 2) |

0.82 | 3.98 (1.08 to 6.88) |

0.004* |

| At 135° GH abduction | 1.02 (−2.41 to 4.45) |

0.76 | 8.96 (5.24 to 12.6) |

< 0.001 * |

| PMI | −0.34 (−1.04 to 0.36) |

0.49 | 0.45 (−0.32 to 1.21) |

0.351 |

| LSI | 0.00 (−0.55 to 0.55) |

1 | 0.05 (−0.55 to 0.64) |

0.98 |

*Statistically significant (p<0.05).

GH, glenohumeral; LSI, Levator Scapulae Index; PMI, Pectoralis Minor Index; SUR, scapular upward rotation.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore potential differences in scapular positioning and scapular pattern of movement between the symptomatic shoulder in patients with chronic SAPS, compared with the contralateral asymptomatic, and control shoulders. We found statistical significant differences in the three groups in SUR at 45°, 90° and 135° of shoulder elevation. Specifically, an increased SUR at all positions (45°, 90° and 135°) was found in favour of the symptomatic shoulders when symptomatic and control participants were compared. No differences were found between symptomatic and asymptomatic groups. Hence, our hypothesis was only partially confirmed. Regarding PMI and LSI, there were no significant differences in the groups, thus, our hypothesis was not confirmed.

This is the first study that compares SUR, PMI and LSI between both symptomatic and asymptomatic shoulders in patients with SAPS, and between symptomatic shoulder with control subjects, using accessible and low-cost tools. Previous studies have reported differences in SUR during arm elevation between the symptomatic and the asymptomatic shoulder,19 20 34 showing a decreased SUR in the symptomatic shoulders, mainly within the first degrees of elevation in the scapular plane. We found a significantly increased SUR in the symptomatic shoulder of patients when compared with control subjects. These differences surpassed the MDC95 in all the positions (45°, 90° and 135° of shoulder elevation). This is not supported by current literature, which suggests the presence of a decreased SUR in shoulders with subacromial symptoms compared with healthy controls19 34 35 This can be explained by the fact that patients that were included in our study experienced shoulder pain of a long duration, meaning chronicity of symptoms. In this context, the firing pattern of scapular muscle units can change, generating an early SUR in an attempt to avoid pain. This altered pattern has been found in a recent study.36 It can be hypothesised that early stages of SAPS could present a deficit in SUR while more advanced stages can develop a compensatory increased SUR. As this was not measured in this study, further investigation is needed to confirm that. In other shoulder conditions, current research analysing SUR in both symptomatic and pain-free shoulders does not sustain strong conclusions. Kijima et al 37 showed an absence of differences in SUR, measured by a three-dimensional scapular kinematic analysis, in symptomatic rotator cuff tears, contralateral shoulder and healthy shoulders. Furthermore, Hung et al 38 reported no differences in SUR, measured by three-dimensional analysis, in patients with glenohumeral instability and healthy controls.

With regard to the pectoralis minor length, there was an absence of statistical significant difference between the symptomatic and the asymptomatic shoulders, as well as in symptomatic shoulder patients when compared with controls. This finding was contrary to what was expected, since a more anterior tilted positioning of the scapula is thought to be correlated with a potential risk of SAPS. Our results are in line with those obtained by Struyf et al.14 The aforementioned study showed PMI values of 9.17 (SD 0.54) in the dominant side in the control group, 9.66 (SD 0.68) in the symptomatic side and 9.64 (SD 0.72) in the asymptomatic side in the patient group, but they did not study the statistical differences between groups. On the other hand, Lewis et al 15 also reported values that analysed pectoralis minor length. Nevertheless, comparisons with the present study are not possible as the used test was different (acromion-table distance test). To our knowledge there are no studies investigating these potential differences. Previous studies12 have found a similar scapular behaviour to those suffering from SIS, in healthy subjects with a shortened pectoralis minor. Likewise, pectoralis minor length presents a weak positive correlation with the acromiohumeral distance in healthy male athletes,29 which means that the pectoralis minor could have a slight influence in the scapular positioning in the case of shortening. However, based on the results obtained in the present study, and also on previous inconsistent evidence on this topic,6 10 a shortened pectoralis minor does not seem to play a key role in patients with chronic SAPS, when compared with contralateral non-affected shoulders and control subjects.

In relation to levator scapulae length, there was an absence of differences between symptomatic and asymptomatic shoulder in patients, and between symptomatic shoulder and controls in this study. As far as we know, this is the first study that analyses such differences between subjects with shoulder symptoms and controls, so comparisons with others are difficult. It is thought that a shortened levator scapulae can produce a scapula more downwardly rotated13 and, hence, a greater compromise of the subacromial space during overhead movements. As we did not determine the scapular position in this study, a conclusion on the absence of differences in levator scapulae length in different groups cannot be made, thus further studies are needed in this field.

Some strong points from this study need to be mentioned. First, an exhaustive ultrasound and clinical assessment to avoid the inclusion of patients with rotator cuff tears, was carried out. Second, the examiner who assessed all the measurements had extensive clinical experience.

On the other hand, some limitations need to be recognised. As only one examiner assessed all the outcome measures, inter-rater reliability was not calculated, so this could introduce bias. Moreover, as the minimal clinically important difference of SUR is unknown, we cannot make a conclusion as to whether the differences found in this study have clinical importance or not. Our results should be taken with caution when interpreted, as a sample with chronic SAPS was studied, so we do not know if these results can be extrapolated to other populations, for example, acute shoulder pain. Lastly, including healthy controls by using a SPADI score below 15 points could mean bias.

The present results could have clinical implications, and could contribute to increase the body of knowledge in the field of scapular biomechanic tests. First, it seems that pectoralis minor and/or levator scapulae are not distinguishing factors when comparing the symptomatic and the contralateral asymptomatic shoulder in subjects suffering from SAPS. Second, the use of the SUR test at 45°, 90° and 135° of shoulder elevation may be useful in the assessment of shoulder conditions when compared with values from control subjects.

Further research that analyses levator scapulae length and scapular positioning, and the minimal clinical important difference in SUR, would contribute to enhance knowledge in this field. Moreover, studies analysing changes in SUR and pectoralis minor length after application of physical therapies are necessary to corroborate their contribution, as indicators of improvement, when patients with chronic SAPS are treated.

In conclusion, SUR is greater in patients with chronic SAPS when compared with controls at different angles of shoulder elevation, and is also greater in PMI values at rest position. The usefulness of the present findings is theorised, but further studies to confirm this in clinical practice are needed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The presented work follows the ICMJE recommends for authorship, based on the following four criteria: all authors have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work (SN-L and AL-S); or the acquisition (SN-L, MF-S and AL-S), analysis (JMM-A and AL-S) or interpretation of data for the work (SN-L and AL-S). Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content (SN-L, MF-S, FS, JM-C, JMM-A and AL-S). Final approval of the version to be published (SN-L, MF-S, FS, JM-C, JMM-A and AL-S). Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. In addition, authors have confidence in the integrity of the contributions of their coauthors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethicalapproval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Health Care Districtwhere the primary care centres were located (PI9/012014).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data sharing statement is currently not available due to a secondary analysis is being made. However, the available data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author when the whole work is finished.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Herin F, Vézina M, Thaon I, et al. . Predictors of chronic shoulder pain after 5 years in a working population. Pain 2012;153:2253–9. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Luime JJ, Koes BW, Hendriksen IJ, et al. . Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population; a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol 2004;33:73–81. 10.1080/03009740310004667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bergman GJ, Winters JC, Groenier KH, et al. . Manipulative therapy in addition to usual care for patients with shoulder complaints: results of physical examination outcomes in a randomized controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010;33:96–101. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roquelaure Y, Ha C, Leclerc A, et al. . Epidemiologic surveillance of upper-extremity musculoskeletal disorders in the working population. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:765–78. 10.1002/art.22222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Linsell L, Dawson J, Zondervan K, et al. . Prevalence and incidence of adults consulting for shoulder conditions in UK primary care; patterns of diagnosis and referral. Rheumatology 2006;45:215–21. 10.1093/rheumatology/kei139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ratcliffe E, Pickering S, McLean S, et al. . Is there a relationship between subacromial impingement syndrome and scapular orientation? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1251–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCreesh KM, Crotty JM, Lewis JS. Acromiohumeral distance measurement in rotator cuff tendinopathy: is there a reliable, clinically applicable method? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:298–305. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Diercks R, Bron C, Dorrestijn O, et al. . Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of subacromial pain syndrome. Acta Orthop 2014;85:314–22. 10.3109/17453674.2014.920991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Windt DA, Koes BW, Boeke AJ, et al. . Shoulder disorders in general practice: prognostic indicators of outcome. Br J Gen Pract 1996;46:519–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Timmons MK, Thigpen CA, Seitz AL, et al. . Scapular kinematics and subacromial-impingement syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Sport Rehabil 2012;21:354–70. 10.1123/jsr.21.4.354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kibler WB, Ludewig PM, McClure PW, et al. . Clinical implications of scapular dyskinesis in shoulder injury: the 2013 consensus statement from the ’Scapular Summit'. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:877–85. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Borstad JD, Ludewig PM. The effect of long versus short pectoralis minor resting length on scapular kinematics in healthy individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2005;35:227–38. 10.2519/jospt.2005.35.4.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee JH, Cynn HS, Choi WJ, et al. . Reliability of levator scapulae index in subjects with and without scapular downward rotation syndrome. Phys Ther Sport 2016;19:1–6. 10.1016/j.ptsp.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Struyf F, Meeus M, Fransen E, et al. . Interrater and intrarater reliability of the pectoralis minor muscle length measurement in subjects with and without shoulder impingement symptoms. Man Ther 2014;19:294–8. 10.1016/j.math.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewis JS, Valentine RE. The pectoralis minor length test : a study of the intra-rater reliability symptoms. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007;10:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rosa DP, Borstad JD, Pires ED, et al. . Reliability of measuring pectoralis minor muscle resting length in subjects with and without signs of shoulder impingement. Braz J Phys Ther 2016;20:176–83. 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosa DP, Santos RV, Gava V, et al. . Shoulder external rotation range of motion and pectoralis minor length in individuals with and without shoulder pain. Physiother Theory Pract 2018;16:1–9. 10.1080/09593985.2018.1459985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosa DP, Borstad JD, Pogetti LS, et al. . Effects of a stretching protocol for the pectoralis minor on muscle length, function, and scapular kinematics in individuals with and without shoulder pain. J Hand Ther 2017;30:1–9. 10.1016/j.jht.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Struyf F, Nijs J, Baeyens JP, et al. . Scapular positioning and movement in unimpaired shoulders, shoulder impingement syndrome, and glenohumeral instability. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2011;21:352–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ellenbecker TS, Cools A. Rehabilitation of shoulder impingement syndrome and rotator cuff injuries: an evidence-based review. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:319–27. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Struyf F, Nijs J, Mottram S, et al. . Clinical assessment of the scapula: a review of the literature. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:883–90. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Larsen CM, Juul-Kristensen B, Lund H, et al. . Measurement properties of existing clinical assessment methods evaluating scapular positioning and function. A systematic review. Physiother Theory Pract 2014;30:453–82. 10.3109/09593985.2014.899414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De GA, Van KM, Vervloesem N, et al. . Ac ce pt us t. Physiotherapy 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ben KW, Sciascia A. Current concepts : scapular dyskinesis Current concepts : scapular dyskinesis. Sport Med 2010:300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cools AM, Cambier D, Witvrouw EE. Screening the athlete’s shoulder for impingement symptoms: a clinical reasoning algorithm for early detection of shoulder pathology. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:628–35. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.048074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wiener SN, Seitz WH. Sonography of the shoulder in patients with tears of the rotator cuff: accuracy and value for selecting surgical options. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993;160:103–7. 10.2214/ajr.160.1.8416605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Engebretsen K, Grotle M, Bautz-Holter E, et al. . Predictors of shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI) and work status after 1 year in patients with subacromial shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:218 10.1186/1471-2474-11-218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Watson L, Balster SM, Finch C, et al. . Measurement of scapula upward rotation: a reliable clinical procedure. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:599–603. 10.1136/bjsm.2004.013243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mackenzie TA, Herrington L, Funk L, et al. . Relationship between extrinsic factors and the acromio-humeral distance. Man Ther 2016;23:1–8. 10.1016/j.math.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roach KE, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, et al. . Development of a shoulder pain and disability index. Arthritis Care Res 1991;4:143–9. 10.1002/art.1790040403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. MacDermid JC, Solomon P, Prkachin K. The shoulder pain and disability index demonstrates factor, construct and longitudinal validity. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2006;7:12 10.1186/1471-2474-7-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Membrilla-Mesa MD, Cuesta-Vargas AI, Pozuelo-Calvo R, et al. . Shoulder pain and disability index: cross cultural validation and evaluation of psychometric properties of the Spanish version. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:1–6. 10.1186/s12955-015-0397-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Portney LG, Watkins MP. Statistical measures of reliability Foundations of clinical research : applications to practice, 2000:557–86. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Turgut E, Duzgun I, Baltaci G. Scapular asymmetry in participants with and without shoulder impingement syndrome; a three-dimensional motion analysis. Clin Biomech 2016;39:1–8. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ludewig PM, Cook TM. Alterations in shoulder kinematics and associated muscle activity in people with symptoms of shoulder impingement research report alterations in shoulder kinematics and associated muscle activity in people with. Phys Ther 2000;80:276–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Michener LA, Sharma S, Cools AM, et al. . Relative scapular muscle activity ratios are altered in subacromial pain syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2016;25:1861–7. 10.1016/j.jse.2016.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kijima T, Matsuki K, Ochiai N, et al. . In vivo 3-dimensional analysis of scapular and glenohumeral kinematics: comparison of symptomatic or asymptomatic shoulders with rotator cuff tears and healthy shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015;24:1817–26. 10.1016/j.jse.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hung Y, Darling WG. Scapular orientation during planar and three-dimensional upper limb movements in individuals with anterior glenohumeral joint instability, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.