Abstract

Objective

To examine the effect of smoking on risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) in Korean young men and to examine whether serum total cholesterol levels could modify the effect of smoking on ASCVD.

Design

A prospective cohort study within a national insurance system.

Setting

Health screenings provided by national insurance in 1992 and 1994.

Participants

A total of 118 531 young men between 20 and 29 years of age and were followed up for an average of 23 years.

Outcome measure

To assess the independent effects of smoking on the risk of ischaemic heart disease (IHD), stroke and ASCVD, Cox proportional hazards regression models were used, controlling for age, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia and alcohol drinking.

Results

The total number of current smokers was 78 455 (66.2%), and 94 113 (79.7%) of the sample recorded a total cholesterol level <200 mg/dL measured at baseline. Between 1993 and 2015, 2786 cases of IHD (53/100 000 person year), 2368 cases of stroke (45.4/100 000 person year) and 6368 ASCVD (122.7/100 000 person year) occurred. The risk of IHD, stroke and total ASCVD events was found to increase for current smokers, with a HR with 95% CI of 1.5 (95% CI 1.3 to 1.6), 1.4 (95% CI 1.2 to 1.6) and 1.4 (95% CI 1.3 to 1.5), respectively. Furthermore, the risks above were also found throughout the range of serum levels of cholesterol.

Conclusions

Smoking among Korean young adult men was independently associated with increased risk of IHD, stroke and ASCVD. The concentration of cholesterol in Korean men did not modify the effect of smoking on ASCVD.

Keywords: smoking, cardiovascular disease, young adults

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Novel result from Korean young adults is that smoking is the first leading cause of cardiovascular disease (CVD) while smoking is the second leading cause of CVD in middle-aged adults.

The large sample size of cohort with 118 531 young men between 20 and 29 years of age and were followed up for an average of 23 years.

The limitations of this study include possible measurement errors and the non-random sample used.

Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ASCVD) are the leading cause of death globally, with more people dying from ASCVD than any other causes of death annually. A total of 17.7 million people died as a result of ASCVDs in 2015 globally, comprising 31% of all deaths. Of these deaths, 7.4 million are estimated to have been the result of coronary heart disease, while 6.7 million were due to stroke.1 According to previous studies published in the western countries, tobacco use has been reported to be a major risk factor for ASCVD following hypertension.1

A growing concern is that for young adults, cigarette smoking may be the first leading cause of ASCVD, owing to the high prevalence of cigarette smoking in comparison to lower levels of alternate risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes and high cholesterol levels. However, despite these observations, there remain only a small number of studies considering the relationship between smoking and ASCVD in Korea and other countries in East Asia.2–5

Furthermore, comparisons with Western populations may be less informative owing to the relatively lower levels of cholesterol commonly present in Asian countries. Biological studies have explored the interaction between smoking and serum cholesterol levels.6–9 Nevertheless, very few studies have analysed the interaction effects of smoking and serum cholesterol on ASCVD in young adults.

‘World No Tobacco Day 2018’ is a campaign, with the primary objective of raising awareness of the link between tobacco use and negative health outcomes, predominantly heart and other cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) including stroke. It will also seek to expand the range of potential strategies key public actors such as governmental and public bodies can take to reduce the health risks of tobacco use. If there is an established link between tobacco smoking in young adults and CVD, the campaign will further increase awareness on smoking in young adults. The government and the public can then subsequently take actions to reduce risks of smoking at earlier stage. Unfortunately, however, the association between smoking and CVD in young adults has not received much attention because at least a long-term (over 20 years) follow-up study is needed. This serves as motivation for this study, in which we aimed to examine the effect of smoking on risk of ASCVD in Korean young adults with relatively low serum cholesterol levels. We also investigated whether the effect of smoking can be modified by serum levels of cholesterol.

Method

Study participants

In Korea, the Korean Medical Insurance Corporation (KMIC) provided health insurance for private school staff and civil servants prior to the current insurance system, under which it was integrated as National Health Insurance.2 A total of 4 862 438 (10.7%) of the Korean population were covered by KMIC insurance, of which 1 297 833 were employees, and 3 364 605 were dependents. All insured participants are required to participate in a biennial health check-up.2 Approximately 94% of the insured participants in 1992 and 1994 were examined biennially. We established a prospective cohort for participants (aged 20–29 years) who routinely responded to the questionnaire on disease risk factors and chronic diseases, naming this study the Korean Life Course Health Study (KLCHS). The KLCHS cohort included 307 041 Koreans (142 461 males, 164 580 females) who were screened by KMIC in 1992 and 1994. Of these participants, 205 840 (67.0%) were registered in 1992 and 101 201 (33.0%) were registered in 1994.

Of these 307 041 participants, 71 760 (23.4%) who had incomplete data height, blood pressure, fasting glucose, total cholesterol or body mass index (BMI) were excluded. We also excluded 6170 people from our analysis who reported a medical history of cancer and ASCVD, as well as 2091 people who had missing information on smoking, exercise or alcohol drinking, and 65 people who died before start of follow-up. Female participants were excluded, because of the low prevalence of smoking for females in Korea, resulting in a total of 118 531 eligible participants for the analysis. This study was a retrospective cohort using past routine laboratory data and did not receive consent.

Data collection

The biennial KMIC screening was provided at local hospitals by medical practitioners according to standard protocols. During the 2 year interval examination from 1992 to 2008, we examined the variables related to the lifestyle of participants, such as daily smoking amount, duration of smoking and variables related to drinking. From data collected at baseline, participants were defined as ‘current smokers’ if they were smoking currently, ‘never smokers’ if they had no prior history of smoking and ‘ex-smokers’ if they had previously smoked but at the time of measurement did not smoke. Current smokers were further categorised by amount of cigarettes consumed on average per day (1–9, 10–19 and 20 or greater) as well as duration of smoking (1–9, 10–19 and 20 or more years) following the example of previous studies.2 10 11

The definition of hypertension was a systolic BP ≥140 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg.12 BMI was measured as weight (kg)/height (m2). Serum total cholesterol was grouped as desirable (<200 mg/dL), borderline-high (200–239 mg/dL) and high (≥240 mg/dL).13 Definition of diabetes was fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL.14

Follow-up and outcomes

The main outcome variables used in the analysis were morbidity and mortality categorised by ischaemic heart disease (IHD), stroke and ASCVD. For IHD, alone (ICD (International Classification of Diseases) 10 codes, I20–I25), acute myocardial infarction (AMI) alone (I21) and angina pectoris alone (ICD 10 codes, I20) are used. For stroke, stroke alone (I60–I69) was used. Finally, with regard to ASCVD, we used total ASCVD, including disease of hypertensive (I10–I15), IHD (I20–I25), all stroke (I60–I69), other heart disease (I44–I51), sudden death (R96) and other vascular disease (I70–I74).

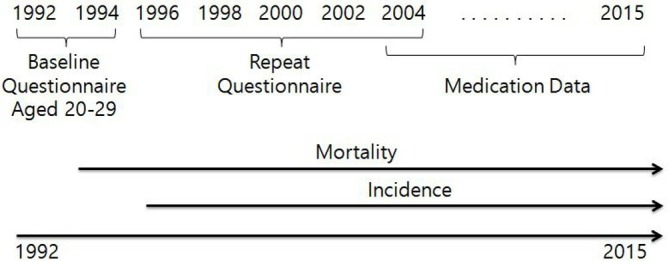

The study outcomes were identified through diagnosis information recorded in hospital admission, and from causes of death using death certificates. The study follow-up was nearly 100% complete, as we were able to search ASCVD event data electronically by KMIC registrants regarding the morbidity information of ASCVD. The period of follow-up was 23 years from 1 January 1993 to 31 December 2015. Data on causes of death were available during years 1993–2015, and incidence could be tracked during years 1995–2015. The time frames over which these outcomes could be assessed varied with data availability (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline for data collection in the Korean Life Course Health Study.

A validation study was conducted by 20 internists from the Korean Society of Cardiology in 2009.15 For the participants who provided written permission for the use of their personal information, 673 CHD events between 1994 and 2007 were confirmed with individual hospital medical records, showing that 73% of designated myocardial infarctions were valid. The validation study was updated in 2013 with a value of 93%.16 The validation study on mortality data has not been conducted.

Statistical analysis

First, we examined relationships between smoking status and established ASCVD risk factors at baseline. In considering continuous ASCVD risk factors, we used ordinary least squares regression and coded smoking quantity as an ordinal variable. In this study, the Mantel Haenszel method was applied for dichotomous variables.17

To assess the independent effects of smoking on the risk of IHD, stroke and ASCVD, Cox proportional hazards models were used, controlling for age and the confounding variables such as hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol and alcohol drinking. The proportional assumption was also tested utilising Schoenfeld residuals, and the survival curve according to smoking status was plotted using the life-table method. We used Levins formula for calculating population attributable risk (PAR).18 In additional analyses, we excluded all events that had occurred in the first 4 years of follow-up. These analyses ensured sensitivity in our results. In all analyses, a two-sided significance level of 0.05 was used.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and or public were not involved.

Results

The average age of the study participants was 26.7±2.0 (SD) years. Among the 118 531 men, 78 455 (66.2%) were current smokers, 15 126 (12.8%) were ex-smokers and 92 403 (15.4) had hypertension. For total cholesterol, 94 413 (79.7%) had a total serum cholesterol level <200 mg/dL, 19 764 (16.6%) had a borderline level of 200–240 mg/dL and 4444 (3.8%) had a level of 240 mg/dL or higher. In terms of amount of smoking, 28.9% smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day while 45.5% and 25.6% of current smokers smoked 1–9 and 10–19 cigarettes per day, respectively. Among current smokers, 92.0% smoked for less than 10 years while 7.6% and 0.4% of current smokers smoked for 10–19 years and more than 20 years, respectively.

Population characteristics by smoking status are presented in table 1. After adjusting for age, current smokers had a significantly higher BMI (p for trend=0.0056), higher consumption of alcohol drinking (p for trend <0.0001) and higher prevalence of diabetes (p for trend=0.0060) than non-smokers.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the Korean Life Course Health Study, 1992–1994 according to smoking status*

| Characteristics | Non-smokers (n=24 950) |

Ex-smokers (n=15 126) |

No of cigarettes per day among current smokers | |||

| 1–9 (n=22 642) |

10–19 (n=35 690) |

≥20 (n=20 123) |

P for trend† |

|||

| Age, year | 26.6 (2.1) | 26.9 (1.9) | 26.6 (2.0) | 26.8 (1.9) | 26.8 (1.9) | 0.1622 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 120.4 (11.6) | 120.0 (11.8) | 119.8 (11.6) | 120.1 (11.6) | 120.3 (11.6) | 0.2558 |

| Diastolic blood pressure mm Hg | 78.0 (9.0) | 77.7 (9.1) | 77.5 (9.0) | 77.8 (9.0) | 78.0 (9.0) | 0.1122 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 173.4 (32.9) | 173.4 (32.6) | 172.9 (33.1) | 174.5 (33.4) | 177.2 (34.4) | 0.9543 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.3 (2.4) | 22.4 (2.4) | 22.3 (2.4) | 22.5 (2.5) | 22.9 (2.6) | 0.0056 |

| Fasting serum glucose, mg/dL | 86.7 (13.3) | 86.6 (13.5) | 86.2 (14.1) | 86.4 (14.1) | 86.6 (15.3) | 0.4821 |

| Alcohol consumption, g/day | 7.3 (17.7) | 9.7 (19.7) | 12.2 (22.6) | 14.5 (25.1) | 20.4 (36.1) | <0.0001 |

| Conditions, % | ||||||

| Hypertension‡ | 15.7 | 15.1 | 14.5 | 15.6 | 15.7 | 0.7987 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia§ | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 0.0743 |

| Diabetes¶ | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.0060 |

| Alcohol use** | 61.2 | 81.3 | 88.2 | 88.3 | 86.9 | 0.1035 |

| Physical activity | 24.9 | 26.8 | 22.9 | 17.5 | 13.0 | <0.0001 |

*Data are expressed as means (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

†Testing for trend across nonsmokers and current smokers; ex-smokers were excluded.

‡Systolic blood pressure of at least 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mm Hg.

§Total cholesterol level of at least 6.21 mmol/L (240 mg/dL).

¶Fasting serum glucose value of at least 6.99 mmol/L (126 mg/L).

**Consumption of Soju which is a colourless distilled beverage of Korean origin.

The mean length of follow-up was 23 years, for a total of 5 191 823 person-years. During this period, 2786 (90 fatal) IHD cases (53/100 000 person year), stroke cases 2368 (126 fatal) (45.4/100 000 person year) and 6368 ASCVD cases (306 fatal) (122.7/100 000 person year) occurred.

The independent effects of smoking on IHD, stroke and ASCVD were analysed controlling for confounding factors through Cox proportional hazards models, as shown in table 2. The HR relating to IHD for current smokers were 1.5 (p<0.0001), and those of ex-smokers were 1.0 (p=0.8567). The HR of stroke was 1.4 (p<0.0001) for current smokers and 1.1 (p=0.5008) on ex-smokers.

Table 2.

Risk of morbidity from ischaemic heart disease (IHD), cerebrovascular disease (CVD) and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) in Korean Men in the Korean Life Course Health Study, 1992–2015*

| IHD | CVD | ASCVD | ||||

| Variables and categories | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value |

| Age (5-year age group) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) | <0.0001 | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.6) | <0.0001 | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) | <0.0001 |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||

| Ex-smoker | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.8567 | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 0.5008 | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 0.1406 |

| Current smoker | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.6) | <0.0001 | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) | <0.0001 | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Blood pressure† | ||||||

| High normal | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) | <0.0001 | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.3) | 0.0152 | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | <0.0001 |

| Stage 1 hypertension | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) | <0.0001 | 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) | <0.0001 | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.8) | <0.0001 |

| Stage 2 hypertension | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.5) | <0.0001 | 3.2 (2.5 to 4.0) | <0.0001 | 2.9 (2.5 to 3.3) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol‡ | ||||||

| Borderline-high cholesterol | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.6) | <0.0001 | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.6) | <0.0001 | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.5) | <0.0001 |

| High cholesterol | 2.5 (2.1 to 2.8) | <0.0001 | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.1) | <0.0001 | 2.1 (1.8 to 2.3) | <0.0001 |

| Fasting blood sugar§ | ||||||

| Diabetes | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.9) | 0.1375 | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.3) | 0.0222 | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) | 0.0008 |

| Physical activity | ||||||

| No exercise | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 0.0122 | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 0.2156 | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 0.0075 |

*HRs and 95% Cls from multivariable Cox proportional hazards models.

†The reference category is normal (systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg).

‡The reference category is desirable (serum cholesterol level, <5.17 mmol/L [200 mg/dL]).

§The reference category is a fasting serum glucose level of less than 6.99 mmol/L (126 mg/dL).

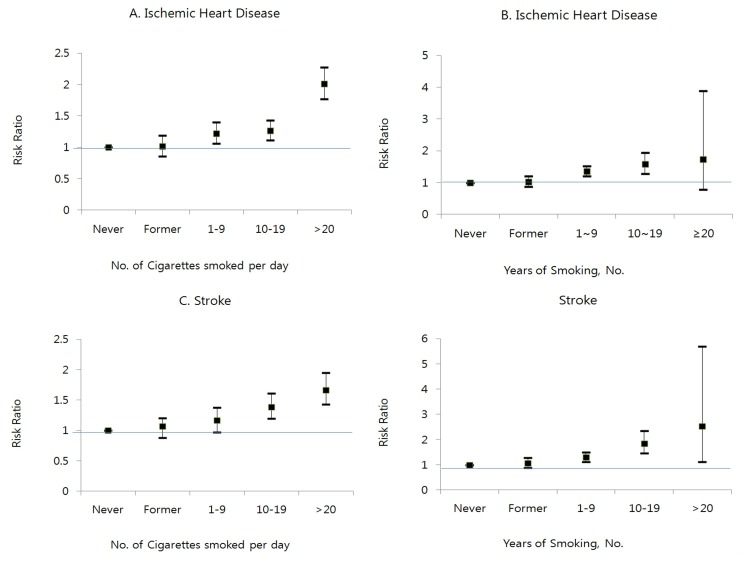

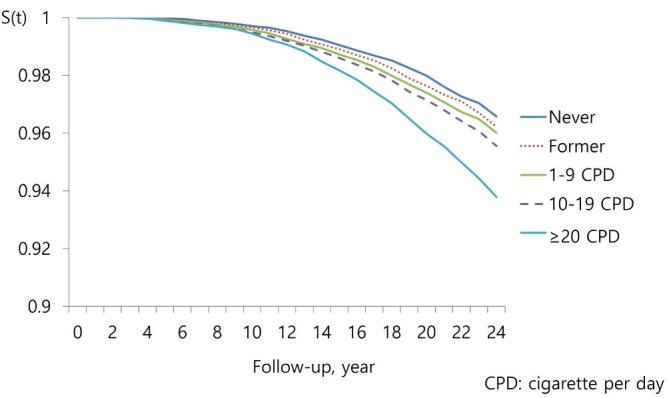

Compared with non-smokers, the HR for any ASCVD event was 1.4 (p<0.0001) in current smokers and 1.1 in ex-smokers (p=0.1406). Figure 2 shows the survival probability by smoking history (never, former, 1–9, 10–19, ≥20 cigarette per day among current smokers) and the corresponding unadjusted association with ASCVD. The overall results demonstrated that smoking among young men increased the risk for ASCVD relative to non-smokers. After adjusting for age and traditional ASCVD risk factors, the HRs for IHD and stroke were estimated for groups classified by amount of smoking (figure 3A, B) and duration of smoking (figure 3C, D). For IHD and stroke, the risk of events increased linearly with higher amount of cigarette per day (p for trend, <0.0001 and <0.0001, respectively) and longer duration of smoking (p for trend, <0.0001 and <0.0001, respectively).

Figure 2.

Survival of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease event by smoking history in Korean young adult men, 1992–2015.

Figure 3.

HR with 95% CIs for ischaemic heart disease (IHD), and stroke by cigarette per day and duration of smoking. (A) IHD. (B) IHD. (C)Stroke. (D) Stroke. (E) Atherosclerotic c ardiovascular disease (ASCVD). (F) ASCVD.

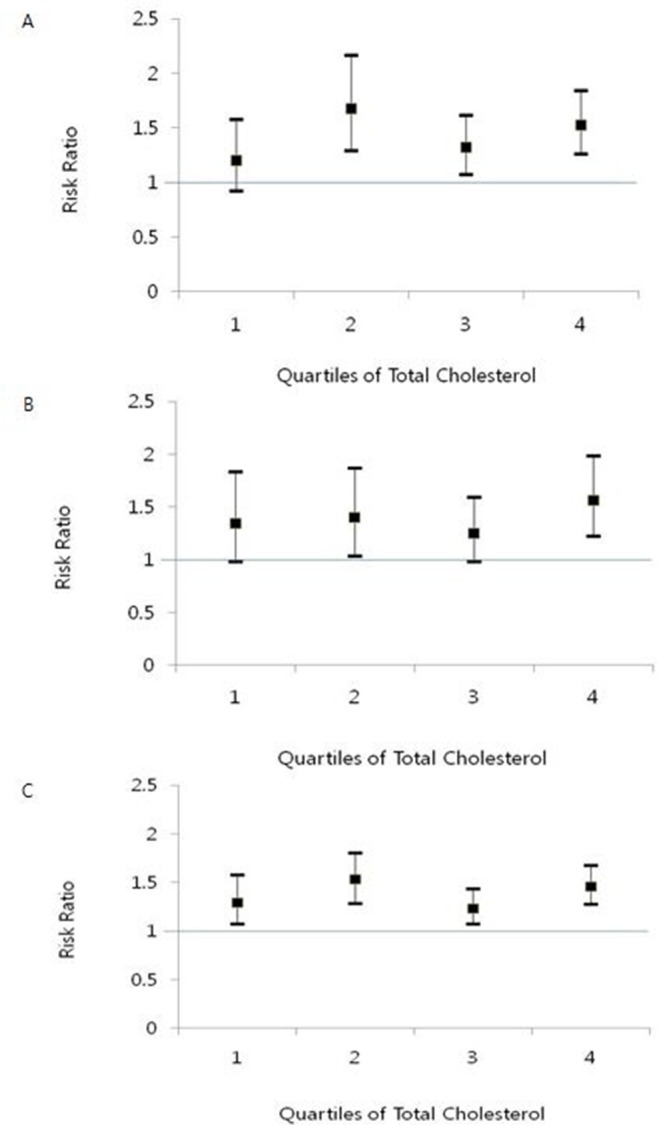

To examine whether serum total cholesterol levels could modify the effect of smoking on ASCVD, we divided the cohort participants into quartile of total cholesterol. The risks above were also found throughout the range of serum levels of cholesterol demonstrating that serum total cholesterol levels did not modify the effect of smoking on ASCVD (figure 4).

Figure 4.

HRs with 95% CIs for ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke by total cholesterol groups of smokers compared with non-smokers: each group of total cholesterol levels are as follows: first, 149 mg/dL; second, 150–169 mg/dL; third, 170–194 mg/dL and fourth, ≥195 mg/dL. The reference group is non-smokers in each quartile of total cholesterol. (A) IHD. (B) Stroke. (C) Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Estimated risk factor prevalence in current studies of smoking and other additional risk factors were used to estimate the PARs for IHD alone, stroke alone and total ASVCD (table 3). For IHD, current smoking accounts for about 24.9% of events, and hypertension accounts for 8.1% of events. In the case of stroke, smoking was estimated to account for 20.9%, while hypertension was estimated to be responsible for 13.3% of stroke cases.

Table 3.

Population attributable risks (PARs) and 95% CIs from smoking and other risk factors of ischaemic heart disease (IHD), cerebrovascular disease (CVD) and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) in Korean men: the Korean Life Course Health Study

| Variables and categories | Prevalence % | IHD PAR (95% CI) | CVD PAR (95% CI) | ASCVD PAR (95% CI) |

| Smoking | ||||

| Current smoker | 66.2 | 24.9 (16.6 to 28.4) | 20.9 (11.7 to 28.4) | 20.9 (16.5 to 24.9) |

| Blood pressure* | ||||

| Hypertension | 22.0 | 8.1 (6.2 to 9.9) | 13.3 (9.9 to 14.9) | 9.9 (9.9 to 11.7) |

| Total cholesterol† | ||||

| Borderline | 16.6 | 6.2 (4.7 to 9.1) | 6.2 (4.7 to 7.7) | 6.2 (4.7 to 7.6) |

| High | 3.8 | 5.4 (4.0 to 6.4) | 4.0 (2.9 to 4.7) | 4.0 (2.9 to 4.7) |

| Fasting blood sugar‡ | ||||

| Diabetes | 0.9 | 0.3 (−0.9 to 0.8) | 0.5 (0.08 to 1.1) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.8) |

| Physical activity | ||||

| No exercise | 0.8 | 7.4 (0 to 19.3) | 7.4 (0 to 19.3) | 7.4 (0 to 19.3) |

*The reference category is normal (systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg).

†The reference category is desirable (serum cholesterol level <5.17 mmol/L [200 mg/dL]).

‡The reference category is a fasting serum glucose level of less than 6.99 mmol/L (126 mg/dL).

Discussion

Our study investigated the association between smoking and risk of ASCVD among Korean young men within a cohort study with a 23 year of follow-up. To our knowledge, this is the first study focusing on Korean young adults. In our study, smoking was the most crucial risk factor attributing to 20% of ASCVD mortality in middle age.

Diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia are well known risk factors for ASCVD.10 However, for young adults with relatively low incidence of diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, smoking is the most important and an independent risk factor for predicting ASCVD in the present study. Furthermore, the high-smoking rate among young people is important with respect to the development of middle-aged hypertension and transition to ASCVD.19 20 Thus, middle-aged ASCVD morbidity is likely predominantly predicted by smoking in young adulthood.

The body of research centred on the health effects of smoking is steadily increasing, with findings reported from many countries around the world. However, few studies have examined the effect of smoking on ASCVD in young adults.21 Here, we present evidence that current smoking is an independent risk factor affecting the incidence of IHD, stroke and ASCVD.

These risk associations have been estimated across total serum cholesterol groups. A cohort study in Hasayama Japan found that smoking showed positive association with coronary heart disease in people with high levels of serum cholesterol above 180 mg/dL, but not with people with low level of cholesterol less than 180 mg/dL.22 23 Afterward, six epidemiological studies were conducted. Among them, one study from Puerto Rico Heart Health Program24 showed similar results, but not all.7–11 Of course, all studies were conducted among adult populations. To the best of our knowledge, no study has been done on young adults with much lower levels of serum cholesterol. In addition, the high smoking rate among young adults is likely to be, even directly, linked to high blood pressure among the adult population who developed ASCVD as a major health problem.

In this study, the non-significant risk of ASCVD among ex-smokers can be interpreted in two ways. First, this result may simply reflect the effect of smoking cessation. Most previous studies have shown that the effects of smoking cessation are immediate in CVD (most of the excess risk of vascular mortality due to smoking may be eliminated rapidly on cessation), while lung cancer occurs within 20 years25 26. In particular, most of the excess risk of vascular mortality due to smoking in women may be eliminated rapidly on cessation and within 20 years for lung diseases.26 Second, even if a number of young adult ex-smokers, aged 20–29 years, may have smoked continuously from adolescence, it is still a short-term of smoking, compared with adults. Previous study shown that reducing adult smoking pays more immediate dividends, both in terms of health improvements and cost savings.27 While present study lacks information on smoking duration of ex-smokers, current smokers who continued to smoke seem to have increased risk of CVD by 40%. Therefore, while the smoking duration of ex-smokers is unknown, it may be reasonable to consider the results were mainly affected by the smoking cessation. Further research on the effects of smoking cessation among young adults is necessary.

There are several studies regarding cardiovascular risk among young people. According to a study conducted by Bernaards et al,28 blood pressure and waist circumference were decreased by lowering weekly tobacco consumption in younger participants. However, they did not report the risk of developing CVD events due to changes in smoking. This seems to be another significant topic relating to the health of young adults. Another study conducted by Morotti et al 21 on young women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) reported an association between smoking habitude in lean PCOS patients, and the increase of soft markers of cardiovascular risk. For young adult African-Americans, the association between cigarette smoking and carotid intima assuming the genetic variation of smokers was reported and the −930A/G polymorphism modified the association among young healthy adults.29 The study on association between secondhand smoking among childhood and cardiovascular event in adulthood was conducted and found that the carotid plaque risk in adulthood is increased in children whose parents had smoked.30 31

This LCHS study has several strengths, such as high follow-up rates and a large, national sample. The large sample size of cohort allowed us to investigate the association of smoking with various levels of serum cholesterol. The civil servants and private school teachers who participated in this study accounted for about 11% of the total population in 1992. We did not compare the characteristics of the 89% population not included in the study. Therefore, this study will not represent the whole population. Moreover, selection bias may be a potential issue, since the final sample contains a subset of over 118 531 young male adults (38.6%) out of 307 041 subjects initially selected for our study. We therefore urge conservative interpretations of our study results with regard to the general population.

In conclusion, smoking is a leading cause of ASCVD among young adults in Korea, a country with a low total cholesterol level and a high-smoking rate. Moreover, the association was not modified by total cholesterol level. Smoking among Korean young adult men was independently associated with increased risk of IHD, stroke and ASCVD. The concentration of cholesterol in Korean men did not modify the effect of smoking on ASCVD. Therefore, smoking cessation on young adult smokers is essential to prevent CVD later in adult life. Moreover, clinical practice guidelines and policies should emphasise to treat nicotine addiction in young smokers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of the Korean National Health Insurance Service, which provided the data for this study.

Footnotes

SHJ and S-C contributed equally.

Contributors: Data analysis was undertaken by YJ and KJJ. The article was drafted by YJ. SL, JHB, SHJ and S-iC substantially contributed to the conception or design of the work, revising the work, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This study was funded with a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI14C2686). The funder had no role in the study design and data collection, in analysing and interpreting data or in the decision to submit this work for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study proposal obtained an approval by the Institutional Review Board of Human Research, Yonsei University (4-2001-0029) and Seoul National University(E1812/001-010).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Fact sheet. 2017. Visited at 3 March, 2018. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/

- 2. Jee SH, Samet JM, Ohrr H, et al. Smoking and cancer risk in Korean men and women. Cancer Causes Control 2004;15:341–8. 10.1023/B:CACO.0000027481.48153.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yuan J-M. Morbidity and mortality in relation to cigarette smoking in Shanghai, China. JAMA 1996;275:1646–50. 10.1001/jama.1996.03530450036029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu BQ, Peto R, Chen ZM, et al. Emerging tobacco hazards in China: 1. Retrospective proportional mortality study of one million deaths. BMJ 1998;317:1411–22. 10.1136/bmj.317.7170.1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Niu SR, Yang GH, Chen ZM, et al. Emerging tobacco hazards in China: 2. Early mortality results from a prospective study. BMJ 1998;317:1423–4. 10.1136/bmj.317.7170.1423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robertson TL, Kato H, Gordon T, et al. Epidemiologic studies of coronary heart disease and stroke in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii and California. Coronary heart disease risk factors in Japan and Hawaii. Am J Cardiol 1977;39:244–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lawlor DA, Song YM, Sung J, et al. The association of smoking and cardiovascular disease in a population with low cholesterol levels: a study of 648,346 men from the Korean national health system prospective cohort study. Stroke 2008;39:760–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.494823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hozawa A, Okamura T, Kadowaki T, et al. Is weak association between cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease mortality observed in Japan explained by low total cholesterol? NIPPON DATA80. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:1060–7. 10.1093/ije/dym169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakamura K, Barzi F, Huxley R, et al. Does cigarette smoking exacerbate the effect of total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol on the risk of cardiovascular diseases? Heart 2009;95:909–16. 10.1136/hrt.2008.147066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jee SH, Suh I, Kim IS, et al. Smoking and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in men with low levels of serum cholesterol: the Korea Medical Insurance Corporation Study. JAMA 1999;282:2149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jee SH, Park J, Jo I, et al. Smoking and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in women with lower levels of serum cholesterol. Atherosclerosis 2007;190:306–12. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003;289:2560–72. Epub 2003 May 14. Erratum in: JAMA. 2003 Jul 9;290(2):197. PubMed PMID: 12748199 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. The National Cholesterol Education Program. Report of the Expert Panel on Blood Cholesterol Levels in Children and Adolescents. NIH Publication No. 91-2732. Bethesda, MD, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14. The Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1997;20:1183–97. 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kimm H, Yun JE, Lee SH, et al. Validity of the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in korean national medical health insurance claims data: the korean heart study (1). Korean Circ J 2012;42:10–15. 10.4070/kcj.2012.42.1.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim HY. Validity of the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in Korean national medical health insurance claims data: the Korean Heart Study [Master thesis]. Seoul, Korea: Yonsei University, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. Vol. 1: The analysis of case-control studies. Lyon, France: IARC Scientific Publication:32;146–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Levin ML. The occurrence of lung cancer in man. Acta Unio Int Contra Cancrum 1953;9:531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thuy AB, Blizzard L, Schmidt MD, et al. The association between smoking and hypertension in a population-based sample of Vietnamese men. J Hypertens 2010;28:245–50. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833310e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim BJ, Seo DC, Kim BS, et al. Relationship between cotinine-verified smoking status and incidence of hypertension in 74,743 korean adults. Circ J 2018;82:1659–65. 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morotti E, Battaglia B, Fabbri R, et al. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular risk in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Fertil Steril 2014;7:301–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kiyohara Y, Ueda K, Fujishima M. Smoking and cardiovascular disease in the general population in Japan. J Hypertens 1990;8(Suppl 5):S9–S15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fujishima M, Kiyohara Y, Ueda K, et al. Smoking as cardiovascular risk factor in low cholesterol population: the Hisayama Study. Clin Exp Hypertens A 1992;14(1-2):99–108. 10.3109/10641969209036174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gordon T, Garcia-Palmieri MR, Kagan A, et al. Differences in coronary heart disease in Framingham, Honolulu and Puerto Rico. J Chronic Dis 1974;27:329–44. 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90013-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thun MJ, Day-Lally C, Myers DG, et al. Trends in tobacco smoking and mortality from cigarette use in Cancer Prevention Studies I (1959 through 1965) and II (1982 through 1988): National Cancer institute, smoking and tobacco control, monograph, 1982:8. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, et al. Smoking and smoking cessation in relation to mortality in women. JAMA 2008;299:2037–47. 10.1001/jama.299.17.2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lightwood JM, Glantz SA. Short-term economic and health benefits of smoking cessation: myocardial infarction and stroke. Circulation 1997;96:1089–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bernaards CM, Twisk JW, Snel J, et al. In a prospective study in young people, associations between changes in smoking behavior and risk factors for cardiovascular disease were complex. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:1165–71. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Murtaugh KH, Borde-Perry WC, Campbell KL, et al. Obesity, smoking, and multiple cardiovascular risk factors in young adult African Americans. Ethn Dis 2002;12:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. West HW, Juonala M, Gall SL, et al. Exposure to parental smoking in childhood is associated with increased risk of carotid atherosclerotic plaque in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Circulation 2015;131:1239–46. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roy MP, Steptoe A, Kirschbaum C. Association between smoking status and cardiovascular and cortisol stress responsivity in healthy young men. Int J Behav Med 1994;1:264–83. 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0103_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.