Abstract

Objectives

Cough is the most common symptom prompting people to consult a doctor, thus representing a huge cost to the healthcare. This burden could be reduced by decreasing the number of repetitive consultations by the same individuals. Therefore, it would be valuable to recognise the factors that associate with repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough.

Design

A cross-sectional, email survey.

Setting

Public service employees in two Finnish towns.

Participants

The questionnaire was sent to 13 980 subjects; 3695 (26.4 %) participated.

Interventions

The questionnaire sought detailed information about participant characteristics, all disorders diagnosed by a doctor, various symptoms and doctor’s consultations. Those with current cough were inquired about cough characteristics and filled in the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ).

Primary outcome

Repetitive (≥3) doctor’s consultations due to cough during the previous 12 months.

Results

There were 205 participants (5.5% of the participants) with repetitive consultations. They accounted for 848 out of the 1681 doctor’s consultations (50.4%) due to cough. Among all participants, repetitive consultations were mainly related to the presence of asthma (adjusted OR (aOR) 2.90 (2.01 to 4.19)) and chronic rhinosinusitis (aOR 2.40 (1.74 to 3.32)). Among the 975 participants with current cough, repetitive consultations were mainly related to a low LCQ total score (aOR 3.84 (2.76 to 5.34) per tertile). Comorbidity, depressive symptoms and smoking were also associated with repetitive consultations.

Conclusions

A modest proportion of subjects with repetitive consultations is responsible for every second doctor’s consultation due to cough. The typical features of these subjects could be identified. These findings can help to focus on certain subpopulations in order to plan interventions to reduce the healthcare burden attributable to cough.

Keywords: respiratory medicine (see thoracic medicine), adult thoracic medicine, asthma, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The results are based on a large community-based sample of 3695 participants.

The study included a comprehensive list of possible risk factors for repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough.

All participants had equal and free-of-charge access to doctors, provided by the participating towns’ occupational healthcare organisations. Therefore, supply related factors do not interfere with the results.

Only slightly over one in four (26.4%) of the original population participated.

As all participants were public service employees, lower social classes and older individuals are underrepresented.

Introduction

Cough is the most common symptom prompting individuals to seek medical help from a physician and thus it poses a major healthcare burden.1 2 In the USA, every year there are 21 million outpatient consultations due to cough.2 Surprisingly, very little is known about the factors that prompt a visit to a doctor due to cough. At present, healthcare seeking behaviour in coughing patients has been mainly investigated in countries in which there is a high prevalence of tuberculosis, with the goal of improving tuberculosis diagnostics.3–5 In countries with a low tuberculosis prevalence, the aims may be different. In view of the ageing of the populations in the developed world and the limited healthcare resources, it would be clearly advantageous if we were able to reduce the number of doctor’s consultations due to cough. However, seeking medical help due to the appearance of recent-onset cough must not be discouraged because this would compromise early diagnostics of life-threatening lung disorders like lung cancer, tuberculosis and interstitial lung disorders. Thus, a more reasonable goal might be to decrease the number of repetitive consultations due to cough by the same individual. If we wish to plan interventions to achieve this goal, then it is important that the factors that are associated with repetitive consultations should be clarified. The present study was conducted to define the factors associated with repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough in a large population of subjects with equal and free-of-charge access to doctors provided by the participants’ occupational healthcare organisations. The present study report is related to two previous publications, which described the risk factors for cough and the consequences of cough in this population.6 7

Methods

Population

This was a cross-sectional email study conducted in all public service employees of two towns in central Finland (altogether 13 980 employees, mean 46.6 years with 79.2% females). All participants had free-of-charge access to doctors, provided by the participating towns’ occupational healthcare organisations. An invitation to the study and the questionnaire were sent to the employees’ email addresses in March to April 2017. Responses were collected via an electronic questionnaire. One reminder message was sent if a subject had not responded within 2 weeks. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the officials of both towns. The invitation letter to participate included detailed information about the study. A participant’s decision to reply was considered as informed consent.

Questionnaire

The first part of the questionnaire (57 questions) was filled in by all participants. All disorders diagnosed by a doctor were inquired, as well as a wide variety of symptoms. Asthma-related, rhinosinusitis-related and reflux-related symptoms were inquired by questions currently recommended for epidemiological studies.8–10 Depressive symptoms were inquired by utilising the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2).11 The number of doctor’s consultations due to cough during the previous 12 months was inquired from all participants. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of 23 cough-related questions to be answered by those participants reporting that they had current cough. It included detailed questions about the cough bout frequency and cough duration, as well as the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ), which measures the cough-related quality of life.12 Many questions were adapted from two previous studies, the Health Behaviour and Health among the Finnish Adult Population study13 and the Finnish National FINRISK study.14

Definitions

The main outcome was repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough. During the last 12 months, 22.5% of the responders had consulted a doctor due to cough at least once, 11.2% at least twice, 5.5% at least three times, 2.7% at least four times and 1.4% at least five times. In the present study, ‘repetitive consultations’ was arbitrarily defined as at least three doctor’s consultations due to cough in the last 12 months.

Current cough was defined as ongoing cough at the time when the survey was conducted. Chronic bronchitis was defined as daily sputum production for at least 3 months of the year. A cough trigger was defined as the presence of one or more identifiable cough triggers. Current asthma was defined as a doctor’s diagnosis of asthma at any age and wheezing during the last 12 months. Chronic rhinosinusitis was present if there was either nasal blockage or nasal discharge (anterior or posterior nasal drip) and either facial pain/pressure or reduction/loss of smell for >3 months.9 Esophageal reflux disease was present if there had been heartburn and/or regurgitation on at least 1 day of the week during the last 3 months.10 Depressive symptoms were present if the PHQ-2 score was 3 or more.11 Allergy was defined as a self-reported allergy to pollens, animals or food. A family history of chronic cough was defined as the presence (now or in the past) of chronic (duration >8 weeks) cough in parents, sisters or brothers. The disorder sum was defined as the number of medical disorders diagnosed by a doctor. The symptom sum was defined as the sum of symptoms (other than respiratory symptoms) reported by the participants.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not directly involved in the design, recruitment or in the conduct of this study. The results will be disseminated to study participants through the Kuopio town and Jyväskylä towns’ intranet portals.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive data are shown as means and 95% CI unless otherwise stated. In the participants with current cough, the LCQ total scores (LCQts) were divided into tertiles. First tertile: 3.0–14.1, second tertile: 14.2–16.8 and third tertile: 16.9–21.0. The cough bout frequency was also divided into tertiles: first tertile: on 2–3 days per week or less often, second tertile: on 4–6 days per week to once daily and third tertile: several times daily. The cough episode duration was categorised according to the current guidelines to <3 weeks (acute cough), 3–8 weeks (subacute cough) and >8 weeks (chronic cough).15 16

The bivariate associations of the following variables with repetitive consultations were analysed: current asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis, esophageal reflux disease, depressive symptoms, disorder sum, symptom sum, acetylsalicylic acid intolerance, allergy, age, gender, body mass index, years of education, family incomes, professional status, number of family members, pet ownership, moisture damage exposure, smoking history, weekly alcohol doses, level of daily physical exercise and family history of chronic cough. In addition to these factors, the following variables were included in the analyses among the 975 participants with current cough: duration of the current cough episode, current cough bout frequency, LCQts, chronic bronchitis and cough trigger.

Mann-Whitney test and χ2 test were applied when appropriate. The variables showing at least a suggestive (p<0.1) association with repetitive consultations in the bivariate analyses were included in the multivariate analyses utilising binary logistic regression analysis with backward directed stepwise process to eliminate non-significant confounders. However, only LCQts was included without its domains due to the presence of strong interrelationships.

A p<0.05 was accepted as the level of statistical significance but in the tables, all factors with at least a suggestive association (p<0.1) are presented. All analyses were performed using SPSS V.22 for the personal computer.

Results

The response rate was 26.4% (3695 participants, mean age 47.8 (47.5–48.2) years, 82.6% females, 31.4% ever-smokers, table 1). The proportion of missing values was <1% in all other questions except for family income (2.5%) and acetylsalicylic acid intolerance (1.4%).

Table 1.

The basic characteristics and their bivariate associations with repetitive (≥3 during the last 12 months) doctor’s consultations due to cough in all participants (n=3695). The figures are percentages or means and 95% CI

| Characteristic | Participants without repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough, n=3490 |

Participants with repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough, n=205 |

P value |

| Female gender, % | 82.5 | 85.3 | 0.30 |

| Age (years) | 47.8 (47.4–48.2) | 48.5 (47.1–50.0) | 0.35 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.5 (26.4–26.7) | 27.9 (27.0–28.7) | <0.001 |

| Family incomes, income class* | 1.98 (1.95–2.00) | 2.06 (1.95–2.16) | 0.17 |

| Moisture damage exposure, % | 25.4 | 33.7 | 0.009 |

| Ever smoking, % | 31.3 | 33.2 | 0.57 |

| Family history of chronic cough, % | 34.7 | 51.0 | <0.001 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid intolerance, % | 4.6 | 9.4 | 0.002 |

| Allergy, % | 17.4 | 27.8 | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms, % | 4.9 | 9.4 | 0.004 |

| Symptom sum | 2.55 (2.48–2.62) | 3.56 (3.24–3.88) | <0.001 |

| Disorder sum | 1.08 (1.04–1.13) | 2.31 (2.08–2.55) | <0.001 |

| Current asthma, % | 8.7 | 36.6 | <0.001 |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis, % | 14.2 | 40.5 | <0.001 |

| Esophageal reflux disease, % | 12.1 | 21.0 | <0.001 |

*Income classes: 1= <15 000€/year; 2=15 000–40 000€; 3=40 000–70 000€; 4=70 000–120 000€; 5=over 120 000€/year. Other definitions, see text.

Among all 3695 responders, there were 205 participants who reported repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough (5.5%). They accounted for 848 out of the 1681 doctor’s consultations due to cough (50.4%) during the last 12 months.

There were 975 participants with current cough (mean age 48.7 (48.0–49.3) years, 83.8% females, 31.4% ever-smokers). Among them, there were 135 participants (13.8% of the participants with current cough) with repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough. They accounted for 573 out of the 926 doctor’s consultations due to cough (61.9%) among the participants with a current cough.

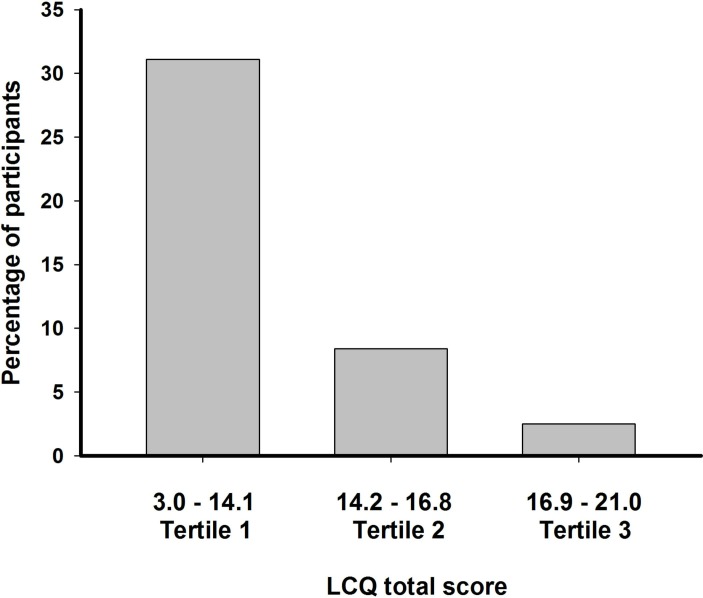

In addition to the other baseline characteristics, table 1 shows all variables for which there was at least a suggestive association with repetitive consultations in bivariate analyses among all 3695 responders. Table 2 shows the results of the multivariate analyses in these individuals. The most important factors were the presence of current asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis. Table 3 shows the results of the bivariate analyses among the 975 participants with current cough and table 4 displays the results of the multivariate analysis in these individuals. Among the participants with current cough, the LCQts was the most important determinant of repetitive doctor’s consultations. The proportions of participants with repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough within each LCQts tertile are illustrated in figure 1.

Table 2.

The characteristics that associated with repetitive (≥3 during the last 12 months) doctor’s consultations due to cough in all partcipants (3695 subjects). Multivariate analysis with adjusted OR (aOR) and CI

| Characteristic | aOR (95 % CI) | P value |

| Current asthma | 2.90 (2.01 to 4.19) | <0.001 |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 2.40 (1.74 to 3.32) | <0.001 |

| Disorder sum* | 1.33 (1.20 to 1.47) | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms† | 1.72 (1.01 to 2.92) | 0.046 |

| Family history of chronic cough | 1.38 (1.02 to 1.87) | 0.039 |

*aOR calculated for every doctor’s diagnosed disorder.

†Patient Health Questionnaire-2 score 3 or more.

Table 3.

The basic characteristics and their bivariate associations with repetitive (≥3 during the last 12 months) doctor’s consultations due to cough among the participants with current cough (n=975). The figures are percentages or means and 95% CI unless otherwise stated

| Characteristic | Participants without repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough, n=840 | Participants with repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough, n=135 |

P value |

| Female gender, % | 83.9 | 83.6 | 0.93 |

| Age (years) | 48.5 (47.8–49.2) | 49.6 (47.8–51.3) | 0.40 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.1 (26.8–27.5) | 27.7 (26.8–28.7) | 0.18 |

| Family incomes, income class* | 2.03 (1.98–2.08) | 2.04 (1.90–2.17) | 0.89 |

| Moisture damage exposure, % | 32.5 | 38.5 | 0.17 |

| Ever smoking, % | 30.4 | 37.8 | 0.085 |

| Family history of chronic cough, % | 46.3 | 53.0 | 0.15 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid intolerance, % | 5.4 | 9.8 | 0.049 |

| Allergy, % | 23.8 | 26.7 | 0.47 |

| Depressive symptoms, % | 5.4 | 6.7 | 0.56 |

| Symptom sum | 3.18 (3.03–3.32) | 3.69 (3.28–4.10) | 0.017 |

| Disorder sum | 1.50 (1.40–1.60) | 2.33 (2.04–2.62) | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchitis, % | 32.5 | 56.7 | <0.001 |

| Current asthma, % | 16.1 | 40.0 | <0.001 |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis, % | 26.5 | 45.9 | <0.001 |

| Esophageal reflux disease, % | 16.5 | 23.0 | 0.068 |

| Cough trigger, % | 73.6 | 88.9 | <0.001 |

| Duration of the cough episode (median, range) | 3–8 weeks (some days to over 10 years) |

2–12 months (some days to over 10 years) |

<0.001 |

| Cough bout frequency (median, range) |

Daily (less than weekly to several times a day) |

Several times a day (less than weekly to several times a day) |

<0.001 |

| LCQ total score | 15.7 (15.5–15.9) | 12.3 (11.8–12.8) | <0.001 |

| LCQ physical domain | 5.06 (5.00–5.12) | 4.08 (3.92–4.23) | <0.001 |

| LCQ psychological domain | 5.18 (5.10–5.25) | 3.96 (3.78–4.13) | <0.001 |

| LCQ social domain | 5.45 (5.38–5.53) | 4.25 (4.05–4.44) | <0.001 |

| Number of doctor’s consultations due to cough during the last 12 months (median, range) | 0 (0–2) | 3 (3–20) | <0.001 |

*Income classes: 1= <15 000€/year; 2=15 000–40 000€; 3=40 000–70 000€; 4=70 000–120 000€; 5=over 120 000€/year. Other definitions, see text.

LCQ, Leicester Cough Questionnaire.

Table 4.

The characteristics that associated with repetitive (≥3 during the last 12 months) doctor’s consultations due to cough among 975 participants with current cough. Multivariate analysis with adjusted OR (aOR) and CI

| Characteristic | aOR (95 % CI) | P value |

| LCQ total score* | 3.84 (2.76 to 5.34) | <0.001 |

| Current asthma | 1.85 (1.16 to 2.94) | 0.010 |

| Duration of cough episode† | 1.50 (1.17 to 1.93) | 0.001 |

| Smoking ever | 1.50 (0.98 to 2.29) | 0.059 |

| Disorder sum‡ | 1.13 (0.99 to 1.29) | 0.061 |

*aOR calculated per one less LCQ total score tertile.

†OR calculated per one duration step (<3, 3–8 and >8 weeks).

‡aOR calculated for every doctor’s diagnosed disorder.

LCQ, Leicester Cough Questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants with repetitive (≥3 during last 12 months) doctor’s consultations due to cough in each Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) total score tertile. n=975, participants with current cough. Low LCQ total score indicates poor cough-related quality of life. LCQ, Leicester Cough Questionnaire.

The associations of each of the 19 LCQ questions with repetitive doctor’s consultations were analysed and ranked according to the Mann-Whitney test z-score. The five questions with the closest associations are presented in table 5. Most of these belonged to the psychological domain of the LCQ.

Table 5.

The five Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) questions, which showed the closest associations with repetitive (≥3 during the last 12 months) doctor’s consultations among participants with current cough (n=975), according to the Mann-Whitney test z-score. The question with the strongest association is uppermost

| Question | LCQ question number, domain | Participants without repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough, n=840 |

Participants with repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough, n=135 |

Z score |

| In the last 2 weeks, my cough has made me feel anxious. | LCQ 6, psy | 5.37 (5.28–5.46) | 3.83 (3.60–4.06) | −11.2 |

| In the last 2 weeks, have you worried that your cough may indicate a serious illness? | LCQ 16, psy | 5.70 (5.61–5.79) | 4.34 (4.10–4.57) | −10.3 |

| In the last 2 weeks, my cough has made me feel fed up. | LCQ 13, psy | 4.49 (4.37–4.61) | 2.88 (2.62–3.14) | −9.5 |

| In the last 2 weeks, have you been tired because of your cough? | LCQ 3, phy | 5.29 (5.19–5.39) | 3.99 (3.76–4.23) | −9.3 |

| In the last 2 weeks, have you been concerned that other people think something is wrong with you, because of your cough? | LCQ 17, psy | 5.91 (5.83–6.00) | 4.70 (4.45–4.96) | −9.2 |

*Domain indicates the LCQ domain (Psy=psychological, Phy=physical, soc=social). The scale in each question is 1–7 with a lower value indicating more severe impairment. The figures are means and 95% CI. P<0.001 between the subgroups in all presented questions.

Discussion

The present study in an employed, working-age population revealed that a modest proportion (5.5%) of participants with repetitive doctor’s consultations was responsible for about every second consultation to the doctor because of cough. In the entire population, the list of factors underpinning the repetitive consultations resembled that of the common causes of chronic cough,15 16 that is, it was predominated by current asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis. The analysis among the 975 participants with current cough included more detailed information about the characteristics of their cough. In this analysis, the dominant factor behind the repetitive consultations was the severity of the impairment in the cough-related quality of life.

It is well known that a small proportion of individuals account for the majority of healthcare utilisation and spending. Most of the studies about these ‘high cost users’ have concentrated on the most expensive forms of healthcare, such as inpatient care, emergency consultations and operations, and have not been concerned with primary care consultations.17–20 These high cost users are often found to be elderly, have a low socioeconomic status and suffer from several comorbid illnesses including mental illnesses or addictions. Accordingly, in the present population, it was found that the number of comorbid illnesses, the presence of depressive symptoms and smoking were associated with repetitive consultations. However, age did not show an independent association. This discrepancy may be attributable to the homogeneous nature of our study population, that is, all participants were of working age. Nonetheless, most of the known characteristics of high cost users could be taken into account in the present analyses.

The present population may not represent well the general population since elderly and unemployed subjects were missing. However, this study has one feature, which makes it especially enlightening: all participants had equal and free-of-charge access to doctors, provided by the participating towns’ occupational healthcare organisations. Apart from need-related factors, healthcare utilisation is also supply dependent; this is associated with the nature of the healthcare system.21 In the present study, supply related factors did not influence the results as all the respondents could obtain medical help from their occupational healthcare centre.

Asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis are important background diseases of chronic cough15 16 and therefore it is not surprising that they were clearly associated with repetitive doctor’s consultations in the entire population. It may be fair to say that three or more yearly consultations due to cough by a patient with chronic rhinosinusitis or asthma indicates that there is inadequate control of these disorders. A better understanding of the association of these disorders with cough as well as their more efficient management might effectively decrease the number of doctor’s consultations due to cough. Esophageal reflux disease was not associated with repetitive consultations though it is also considered as an important background disease to chronic cough.15 16 We have previously reported that for some reason in our study population, esophageal reflux disease is much less clearly associated with chronic cough than asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis.6 In the present study, the diagnoses of chronic rhinosinusitis and esophageal reflux disease relied purely on self-reported symptoms, a factor which must be borne in mind when considering the associations of these disorders with repetitive doctor’s consultations.

The analysis among participants with current cough included much more information than the analysis gathered from the entire population. Therefore, different factors were evident. Among these participants, the major factor behind repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough seems to be the level of impairment in the cough-related quality of life. Patients with cough are often dissatisfied with the therapy prescribed by physicians, which may lead to another consultation as the cough continues.22 It is noteworthy that the length of the cough episode was also associated with repetitive doctor’s consultations. Therefore, repetitive doctor’s consultations due to cough could be decreased by more effective clinical management of cough on the first consultation which would make repetitive consultations unnecessary. Further education of general practitioners may be needed to achieve this goal. However, new, effective medications for the long-standing hypersensitivity of the cough reflex arch are also urgently needed.23

The quality of life was measured by the LCQ and the LCQts were divided into tertiles. Given that the present 975 participants with current cough represent an unselected, community-based population, we suggest that the first tertile (3.0–14.1) represents severe cough, the second tertile (14.2–16.8) represents individuals with moderate cough and those in the third tertile (16.9–21) have mild cough. The respective proportions of participants with repetitive doctor’s consultations were 31%, 8% and 2%, highlighting the dominant role of the quality of life impairment. Though LCQ is a well validated questionnaire,12 we are unaware of any previous attempts to grade it in a clinically meaningful way. The grading of LCQts utilised here may have several applications in everyday clinical cough management as well as in epidemiological studies. It could also be applied to create meaningful inclusion criteria for clinical drug trials.

LCQ is a very comprehensive questionnaire with 19 questions covering multiple characteristics of cough. Interestingly, the most important questions with respect to repetitive consultations belonged to the psychological domain. It seems that the crucial factor leading to the decision to seek medical attention is not the symptom per se but the feelings that the symptom induces. This finding suggests that the patient’s concerns may differ significantly from those of the doctor. The latter may be more interested if there are serious symptoms, like haemoptysis, or if there are symptoms suggestive of possible background diseases behind the cough, like wheezing or regurgitation.

There are several shortcomings in the present study. As mentioned, the population may not represent well the general population because elderly and unemployed subjects were missing. In addition, the majority of the participants were female. These facts decrease the applicability of the data to the general population. The participation rate to the survey was relatively low. However, the responders and non-responders did not differ with respect to age and sex distribution. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the low response rate could affect the associations of various features with repetitive doctor’s consultations. The authors did not have access to individual patient files, for example, to investigate physician–patient relationships, the accuracy of diagnoses or treatment details. The information gained is based on self-reports in a cross-sectional design with the associated problems of recall bias, biased reporting and the lack of any possibility to separate associations from causality.

In conclusion, a modest proportion of subjects with repetitive doctor’s consultations is responsible for half of all doctor’s consultations due to cough. This finding may help to focus on certain subpopulations in whom interventions to reduce the number of doctor’s consultations due to cough could be targeted, without compromising early diagnostics of life-threatening lung disorders. In the whole population, repetitive consultations were mainly associated with asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis. A more widespread understanding about the association of these disorders with cough and more efficient management of these disorders might effectively reduce the number of doctor’s consultations due to cough. From the patient’s point of view, the level of impairment in the cough-related quality of life and the prolongation of the cough episode increased the probability of repetitive consultations. Doctor’s consultations due to cough could thus also be decreased by more effective clinical management of cough on the first consultation which would make repetitive consultations unnecessary. Awareness of the psychological nature of the patient’s main concerns may help physicians to better understand the patient complaining of a cough.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Seppo Hartikainen for his assistance in creating the electronic questionnaire and Dr Ewen MacDonald for the language check.

Footnotes

Contributors: HOK has made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, and drafting the work. He has mainly written the manuscript. He has provided the final approval of the version to be published and has consented to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. He was involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. AML has made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, and drafting the manuscript. She has given her final approval of the version to be published and has provided an agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. JP has made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, and interpretation of data for the work, and drafting the manuscript. He has provided a final approval of the version to be published and has given his approval to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The study was funded by grants from Kuopion Seudun Hengityssäätiö and Hengityssairauksien Tutkimussäätiö Foundations. They had no input in the development of the research or in the preparation of this manuscript.

Competing interests: HOK reports grants from Kuopion Seudun Hengityssäätiö Foundation, grants from Hengityssairauksien Tutkimussäätiö, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Mundipharma, Orion Pharma, Oy, Eli Lilly Finland, Boehringer Ingelheim Finland as payments for giving scientific lectures in gatherings organised by medical companies, personal fees from Takeda Leiras, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mundipharma and AstraZeneca, to attend international scientific meetings, in addition to owning shares in Orion Pharma worth 22 000€, outside the submitted work. AML reports grants from Kuopion Seudun Hengityssäätiö Foundation, grants from Hengityssairauksien Tutkimussäätiö, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Orion, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Roche to attend international scientific meetings, outside the submitted work. JP has nothing to disclose.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kuopio University Hospital (289/2015).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Deidentified participant data are available upon request from Heikki Koskela ORCID 0000-0002-3386-3262.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Wändell P, Carlsson AC, Wettermark B, et al. Most common diseases diagnosed in primary care in Stockholm, Sweden, in 2011. Fam Pract 2013;30:506–13. 10.1093/fampra/cmt033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for disease control and prevention, USA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2015 Summary Tables. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/web_tables.htm#2015.

- 3. Hoa NB, Tiemersma EW, Sy DN, et al. Health-seeking behaviour among adults with prolonged cough in Vietnam. Trop Med Int Health 2011;16:1260–7. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02823.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Satyanarayana S, Nair SA, Chadha SS, et al. Health-care seeking among people with cough of 2 weeks or more in India. Is passive TB case finding sufficient? Public Health Action 2012;2:157–61. 10.5588/pha.12.0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Senkoro M, Hinderaker SG, Mfinanga SG, et al. Health care-seeking behaviour among people with cough in Tanzania: findings from a tuberculosis prevalence survey. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015;19:640–6. 10.5588/ijtld.14.0499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lätti AM, Pekkanen J, Koskela HO. Defining the risk factors for acute, subacute and chronic cough: a cross-sectional study in a Finnish adult employee population. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022950 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koskela HO, Lätti AM, Pekkanen J. The impacts of cough: a cross-sectional study in a Finnish adult employee population. ERJ Open Res 2018;4 10.1183/23120541.00113-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sá-Sousa A, Jacinto T, Azevedo LF, et al. Operational definitions of asthma in recent epidemiological studies are inconsistent. Clin Transl Allergy 2014;4:24 10.1186/2045-7022-4-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2012. Rhinol Suppl 2012;50:1–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, et al. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut 2014;63:871–80. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41:1284–92. 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ, et al. Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ). Thorax 2003;58:339–43. 10.1136/thorax.58.4.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institute for Health and Welfare. Health Behaviour and Health among the Finnish Adult Population. 2019. https://thl.fi/en/tutkimus-ja-kehittaminen/tutkimukset-ja-hankkeet/aikuisten-terveys-hyvinvointi-ja-palvelututkimus-ath/aiemmat-tutkimukset/suomalaisen-aikuisvaeston-terveyskayttaytyminen-ja-terveys-avtk.

- 14. National Institute for Health and Welfare. The National FINRISK Study. 2019. https://thl.fi/en/web/thlfi-en/research-and-expertwork/population-studies/the-national-finrisk-study.

- 15. Morice AH. Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax 2006;61(suppl_1):i1–24. 10.1136/thx.2006.065144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Irwin RS, French CL, Chang AB, et al. Classification of Cough as a Symptom in Adults and Management Algorithms: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2018;153:196–209. 10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rais S, Nazerian A, Ardal S, et al. High-cost users of Ontario’s healthcare services. Healthc Policy 2013;9:44–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hutchinson AF, Graco M, Rasekaba TM, et al. Relationship between health-related quality of life, comorbidities and acute health care utilisation, in adults with chronic conditions. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:69 10.1186/s12955-015-0260-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee NS, Whitman N, Vakharia N, et al. High-Cost patients: hot-spotters don’t explain the half of it. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:28–34. 10.1007/s11606-016-3790-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hensel JM, Taylor VH, Fung K, et al. Unique characteristics of high-cost users of medical care with comorbid mental illness or addiction in a population-based cohort. Psychosomatics 2018;59:135–43. 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: a systematic review of studies from 1998-2011. Psychosoc Med 2012;9:Doc11 10.3205/psm000089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Everett CF, Kastelik JA, Thompson RH, et al. Chronic persistent cough in the community: a questionnaire survey. Cough 2007;3:5 10.1186/1745-9974-3-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abdulqawi R, Dockry R, Holt K, et al. P2X3 receptor antagonist (AF-219) in refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet 2015;385:1198–205. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61255-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.