Abstract

Introduction

Current treatment guidelines for European Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB) recommend cephalosporins, penicillin or doxycycline for 14–28 days but evidence for optimal treatment length is poor. Treatment lengths in clinical practice tend to exceed the recommendations. Most patients experience a rapid improvement of symptoms and neurological findings within days of treatment, but some report long-term complaints. The underlying mechanisms of remaining complaints are debated, and theories as ongoing chronic infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, dysregulated immune responses, genetic predisposition, coinfection with multiple tick-borne pathogens, structural changes in CNS and personal traits have been suggested. The main purpose of our trial is to address the hypothesis of improved outcome after long-term antibiotic treatment of LNB, by comparing efficacy of treatment with 2 and 6 weeks courses of doxycycline.

Methods and analysis

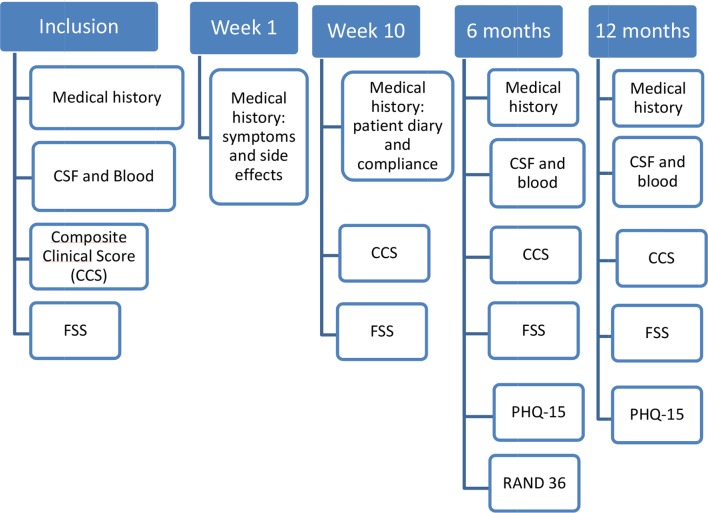

The trial has a multicentre, non-inferiority, double-blinded design. One hundred and twenty patients diagnosed with LNB according to European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS)guidelines will be randomised to 6 or 2 weeks treatment with oral doxycycline. The patients will be followed for 12 months. The primary endpoint is improvement on a composite clinical score (CCS) from baseline to 6 months after inclusion. Secondary endpoints are improvements in the CCS 12 months after inclusion, fatigue scored on Fatigue Severity Scale, subjective symptoms on the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 scale, health-related quality of life scored on RAND 36-item short form health survey and safety as measured by side effects of the two treatment arms. Blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are collected from inclusion and throughout the follow-up and a biobank will be established. The study started including patients in November 2015 and will continue throughout December 2019.

Ethics and dissemination

The study is approved by the Norwegian regional committees for medical and health research ethics and the Norwegian Medicines Agency. Data from the study will be published in peer-reviewed medical journals.

Trial registration number

2015-001481-25

Keywords: infectious disease/HIV, adult neurology, infectious diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The trial has a double-blinded design.

The inclusion criteria for Lyme neuroborreliosis are according to the EFNS guidelines.

The endpoints of the trial are well-defined.

The follow-up period of the included patients is long with registered symptoms, signs and potential side effects.

A weakness of the study is that the primary scoring tool, the composite clinical score, is not validated.

Introduction

European Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB) is caused by the tick-borne spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb). LNB can manifest weeks or months after a tick bite that only half of the patients remember. The most common clinical manifestations are subacute painful radiculitis and cranial neuropathy (most often the facial nerve). More rare manifestations are myelitis, encephalitis and peripheral neuropathies.

Patients diagnosed with LNB should be treated with antibiotics as early as possible to relieve symptoms and prevent sequelae.1–3 Most patients experience a rapid improvement within days of treatment, but some report long-term complaints.4 The most common long-term complaints are fatigue, pain, concentration and memory problems. Some patients may also have neurological sequela such as sensory disturbances, unsteadiness/vertigo, facial paresis and other paresis.5 The underlying mechanisms of remaining complaints are debated. Theories suggested are ongoing chronic Bb infection, dysregulated immune responses, genetic predisposition, coinfection with multiple tick-borne pathogens, structural changes in CNS and personal traits.

Standard treatment for LNB is intravenous ceftriaxone or penicillin, or oral doxycycline for 2–4 weeks.6 Previous studies have shown that 2 weeks of oral doxycycline and intravenous ceftriaxone are equally effective for LNB with painful radiculitis or cranial neuritis and probably also for LNB with symptoms from the central nervous system (myelitis and encephalitis).7–9 Arguments for choosing oral doxycycline are that it is inexpensive and convenient, is found to penetrate the blood–brain barrier and give adequate concentrations in the CSF and is effective against coinfections with other tick-borne agents.10 11

We lack evidence about the optimal duration of antibiotic treatment. Most guidelines recommend treatment for 14–28 days.6 12 13 In Norway, the site for the current study, the guidelines recommend 14 days of treatment. A recent Cochrane review of six randomised treatment studies of adult patients with acute LNB reported improvement in the majority of patients after the initial course of antibiotics and no consistent evidence of treatment failure or need of retreatment.14 In another systematic review, the authors conclude that there is insufficient evidence to determine if extended antibiotic treatment is beneficial to outcome.15 Despite this, and perhaps because of uncertainties surrounding LNB, there are varying treatment regimes in clinical practice, generally with more extensive treatment strategies than recommended in current guidelines. A recent study of the treatment practice of 253 Norwegian LNB patients showed that adherence to guidelines was poor and that two-thirds of the patients received >2 weeks of antibiotic treatment.16 In a time with increasing knowledge and awareness of microbial resistance and other complications of long-term antibiotic treatment, these findings seem like a paradox. The present study therefore seeks to increase the evidence of the current treatment advice by evaluating if treatment with doxycycline for 14 days is inferior or not to treatment for 6 weeks with respect to long-term prognosis of LNB.

Method

Study design and interventions

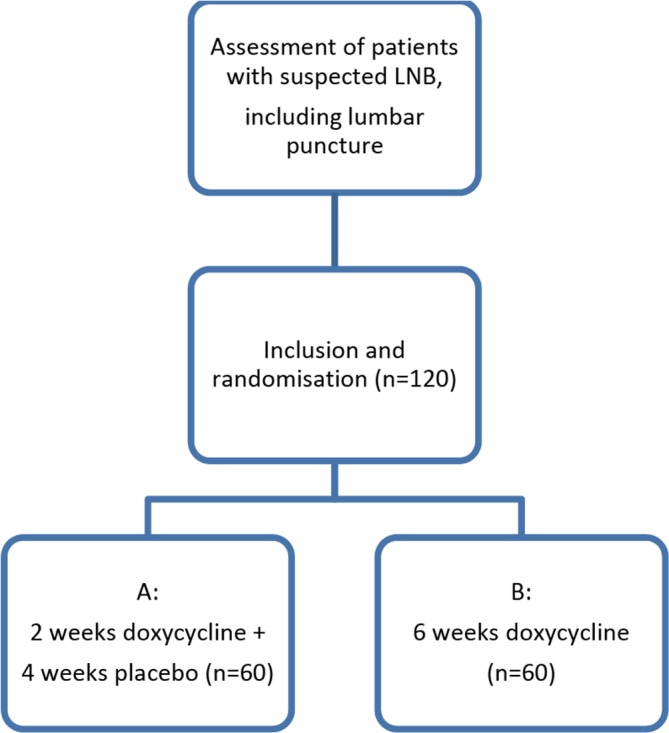

The study is a randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial with a non-inferiority design. We plan to recruit 120 patients diagnosed with definite or probable LNB according to EFNS guidelines6 at six different hospitals in the southern part of Norway as shown in figure 1. The study is coordinated from Sørlandet Hospital in Kristiansand, Agder County by neurologists connected to the large BorrSci study (Lyme borreliosis; a scientific approach to reduce diagnostic and therapeutic uncertainties). The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in box 1. Inclusion started in 2015 and will continue through December 2019 or until the necessary sample size is obtained. Eligibility before inclusion is assessed by, or discussed with, a physician connected to the study and accustomed to evaluating patients with neurological symptoms. The patients are randomised into two treatment arms: (A) doxycycline 200 mg daily for 2 weeks, followed by 4 weeks of placebo; (B) doxycycline 200 mg daily for 6 weeks (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Map of Norway with the active centres of recruitment per August 2018 marked in red.

Box 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Neurological symptoms suggestive of Lyme neuroborreliosis without other obvious reasons, and one or both of

CSF pleocytosis (leucocytes ≥5/mm3).

Intrathecal Borrelia burgdorferi antibody production.

Signed informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Age <18 years.

Treatment with cephalosporin, penicillin or tetracycline macrolide during the last 14 days before start of doxycycline treatment.

Pregnancy, breast feeding and/or women of childbearing potential not using adequate contraception.

Adverse reaction to tetracyclines.

Serious liver or kidney disease that contraindicates use of doxycyline.

Lactose intolerance.

Need to use medications contraindicated according to summary of product characteristics (SmPC) of the Investigational Medicinal Product (IMP) (antacid drugs, didanosine, probenecid, phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, rifampicin).

Figure 2.

Inclusion procedures. LNB, Lyme neuroborreliosis.

Allocation and blinding

Computerised allocation (stratified according to hospital) is performed at Department of Clinical Research Support, Oslo University Hospital, by an internet-based solution. Maximum objective performance and reporting of the study is achieved by applying a ‘penta-blinded’ approach. The first and second blinding is the traditional double blind design with blinding of participants and investigators. Third, the staff evaluating endpoints and adverse effects is blinded to all other study information. Further, the content of all tables and figures will be fixed before any study data are available. Lastly, the statistical procedures will be performed with the two treatment arms marked as group A and B. Revealing the study arms for the investigators will not take place until all patients have completed the 6-month visit, and for the patients after the 12-month visit.

Monitoring and data collection

The study is monitored independently according to good clinical practice (GCP) by the Department of Clinical Research. The coordinating investigators at Sørlandet Hospital and investigators at cooperating centres are certified according to GCP. The investigators will enter the data required by protocol into an electronic Case Report Form (Viedoc), also designed by the Department of Clinical Research. The same protocol for data management and monitoring is applied to all collected data.

Outcome measures

A composite clinical score (CCS) based on subjective symptoms and objective neurological findings from the peripheral and central nervous system (box 2) is registered at baseline, 10 weeks, 6 months and 12 months. Each of the 32 items of the CCS is scored 0=none, 1=mild (without influence on daily life) or 2=severe (with influence on daily life). Maximum total score is 64. The primary endpoint of the study is the difference in CCS sum score at baseline and 6 months after inclusion.

Box 2. Composite clinical score.

Subjective symptoms related by the patient to the current Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB):

Malaise.

Fatigue.

Headache.

Neck and/or back pain.

Abdominal and/or breast pain.

Arm pain.

Leg pain.

Generalised pain located to joints and/or muscles.

Memory and/or concentration problems.

Other.

Peripheral findings related to the current LNB:

Facial palsy.

Paresis of the eye muscles.

Reduced hearing.

Other cranial neuropathies.

Cervical radicular sensory findings.*

Cervical radicular paresis.†

Thoracic radicular sensory findings.*

Lumbar radicular sensory findings.*

Lumbar radicular paresis.†

Non-radicular sensory findings.‡

Non-radicular paresis.§

Other.

Central findings related to the current LNB:

Central findings in one extremity.¶

Central findings in a hemi pattern.

Central findings in both legs.

Central findings in all extremities.

Gait ataxia.

Dysphasia/aphasia.

Nystagmus.

Involuntary movement including tremor.

Cognitive impairment.

Other.

*Abnormal sensory pattern in a radicular pattern.

†Paresis in a radicular pattern.

‡Sensory findings matching with a peripheral nerve or plexus.

§Paresis matching a peripheral nerve or plexus.

¶Central weakness and/or spasticity, impairment in pace or fine motor skills.

Secondary endpoints are the difference in CCS at baseline and 12 months after inclusion, fatigue scored according to the questionnaire Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) at 6 and 12 months, subjective somatic symptoms scores according to the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-15 at 6 and 12 months and health-related quality of life according to RAND 36-item short form health survey at 6 months, and side effects of the treatment.

FSS measures level of agreement from 1 to 7 points with nine statements with the final score representing the mean value of nine items. FSS scores≥5 are regarded as severe fatigue. The FSS has been translated into Norwegian, validated in the general Norwegian population and normative Norwegian data are available.17

PHQ-15 charts prevalence and intensity of 13 somatic symptoms; fatigue/lack of energy and difficulty sleeping during the last 4 weeks. Sum score ranges from 0 to 28 for men and from 0 to 30 for women (only women are asked about menstrual symptoms). The following cut-off values for sum score have been stated for load of somatic symptom, 0–4 points: normal, 5–9 points: mild, 10–14 points: moderate, 15–30 points: severe. The PHQ-15 has been validated in several studies and languages, and normative Swedish data are available.18

RAND 36-item short form health survey consists of 36 questions about different aspects of health-related quality of life. The answer to each question is transformed into a score ranging from 0 to 100, where a higher score indicates better health. The questionnaire is validated in Norwegian, and Norwegian normative data are available.19

Thee patient reported outcome measures were included as secondary endpoints to evaluate the potential impact of residual symptoms on patients daily life.

Systemic and CSF inflammation will be assessed with lumbar punctures and blood samples at 6 and 12 months after treatment. There will be established a biobank from this material. Figure 3 depicts a flowchart of the study procedures.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the study procedures. FSS, Fatigue Severity Scale; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Safety

The patients are followed closely during and after treatment to monitor safety. They are contacted by phone 1 week after start of treatment and questioned about symptom severity and possible side effects. Blood sampling with a status of haematology, liver and kidney function to monitor potential side effects takes place at 2 and 4 weeks after start of treatment. The patients are also asked to fill out a patient diary on symptoms and possible side effects once a week for 10 weeks.

In cases of disease progression, the patients will be evaluated by a physician and adequate intervention initiated. Disease progression is, in this trial, defined as worsening of the patient’s condition attributed to LNB, despite treatment for 14 days with doxycycline, or serious progression of neurological signs from CNS during treatment.

Sample size

We used data including the SD from our previous treatment trial on 102 LNB patients treated with either oral doxycyline or intravenous cephtriaxone for 2 weeks and scored with an almost similar clinical scale as the CCS in the power analyses.7

From a clinical point of view, a mean group difference of Δ=0.5 in disfavour of 2 weeks treatment compared with 6 weeks treatment was regarded as an appropriate non-inferiority margin. This non-inferiority margin corresponds to a Cohen’s d effect size of Δ/σ=0.5/1.0=0.5, which is a small and clinical acceptable effect size. With a one-sided test and significance level of 0.05, 50 patients in each treatment group was found to be needed to claim non-inferiority with a non-inferiority margin on mean group difference of 0.5 and a SD of 1.0 with 80% power. To compensate for up to 20% dropouts and non-evaluable patients 120 (ie, 60 in each group) patients will be enrolled.

Statistical analysis

The main statistical analysis is planned when all patients have completed the 6-month visit. Results will be reported as mean scores with SD or proportions as appropriate.

To compare the primary outcome in the two groups we will use a general linear model with treatment group as a factor, and adjustment for duration of symptoms, gender and age. The analysis will be conducted according to the intention-to-treat principle.

For other analysis, comparison between groups will be done with, for example, independent samples t-test, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test or Pearson’s χ2 test for crosstabs as appropriate. Results from the FSS and PHQ-15 questionnaires will be dichotomised according to predefined cut-offs recommended for case definition and statistically treated as categorical outcomes.

P values <0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Ethics and dissemination

The trial is registered on Clinicaltrials.org. The study will be conducted in accordance with ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and are consistent with Internation Conference of Harmonisation- Good Clinical Pratice (ICH/GCP) (and applicable regulatory requirements.

Each patient in the trial is submitted to extensive follow-up as previously described in terms of disease, effect of treatment and side effects to outweigh potential harms. The benefits are considered to outweigh the cons of this trial in the long term, with a potentially more evidence-based treatment of LNB and less extensive use of antibiotics.

Data from the study will be published in peer-reviewed medical journals.

Patient and public involvement

Representatives from the Norwegian patient organisation for Lyme borreliosis (Norsk Lyme Borreliose Forening) were invited and participated in the early stages of planning of the BorrSci project’s design and gave feedback on the drafts of the application for funding. They were also invited to continue work with the project. Inclusion to the study, implications of the intervention and time required to participate is discussed with each individual patient. Local newspapers and other media have been involved in making the project known to the public in different parts of Norway.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

UL and ÅM contributed equally.

Contributors: AMS contributed in drafting this manuscript, has participated in revisions of the original protocol, includes patients to the study and coordinates the study at Sørlandet Hospital and at the other centres of recruitment. UL and ÅM drafted the original protocol, worked on applications for funding, contributed in drafting this manuscript and include patients to the study.

Funding: This work is supported by the Norwegian Multiregional Health Authorities through the BorrSci project (Lyme borreliosis; a scientific approach to reduce diagnostic and therapeutic uncertainties, project 2015113), letter dated 17 April 2015 with case reference 14/01152-4.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Norwegian regional committees for medical and health research ethics (REC) and the Norwegian Medicines Agency (SLV) have approved the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

References

- 1. Ljøstad U, Mygland A. Remaining complaints 1 year after treatment for acute Lyme neuroborreliosis; frequency, pattern and risk factors. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:118–23. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02756.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eikeland R, Mygland Å, Herlofson K, et al. Risk factors for a non-favorable outcome after treated European neuroborreliosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2013;127:154–60. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2012.01690.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knudtzen FC, Andersen NS, Jensen TG, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcome of lyme neuroborreliosis in a high endemic area, 1995-2014: a retrospective cohort study in Denmark. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:1489–95. 10.1093/cid/cix568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eikeland R, Ljøstad U, Mygland A, et al. European neuroborreliosis: neuropsychological findings 30 months post-treatment. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:480–7. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03563.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dersch R, Sommer H, Rauer S, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of residual symptoms in Lyme neuroborreliosis after pharmacological treatment: a systematic review. J Neurol 2016;263:17–24. 10.1007/s00415-015-7923-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mygland A, Ljøstad U, Fingerle V, et al. EFNS guidelines on the diagnosis and management of European Lyme neuroborreliosis. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:8–e4. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02862.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ljøstad U, Skogvoll E, Eikeland R, et al. Oral doxycycline versus intravenous ceftriaxone for European Lyme neuroborreliosis: a multicentre, non-inferiority, double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:690–5. 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70119-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bremell D, Dotevall L. Oral doxycycline for Lyme neuroborreliosis with symptoms of encephalitis, myelitis, vasculitis or intracranial hypertension. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:1162–7. 10.1111/ene.12420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Borg R, Dotevall L, Hagberg L, et al. Intravenous ceftriaxone compared with oral doxycycline for the treatment of Lyme neuroborreliosis. Scand J Infect Dis 2005;37:449–54. 10.1080/00365540510027228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karlsson M, Hammers-Berggren S, Lindquist L, et al. Comparison of intravenous penicillin G and oral doxycycline for treatment of Lyme neuroborreliosis. Neurology 1994;44:1203–7. 10.1212/WNL.44.7.1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: a review. JAMA 2016;315:1767–77. 10.1001/jama.2016.2884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:1089–134. 10.1086/508667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Halperin JJ, Shapiro ED, Logigian E, et al. Practice parameter: treatment of nervous system Lyme disease (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2007;69:91–102. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265517.66976.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cadavid D, Auwaerter PG, Rumbaugh J, et al. Antibiotics for the neurological complications of Lyme disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;12:Cd006978 10.1002/14651858.CD006978.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dersch R, Freitag MH, Schmidt S, et al. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological treatments for acute Lyme neuroborreliosis - a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2015;22:1249–59. 10.1111/ene.12744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lorentzen ÅR, Forselv KJN, Helgeland G, et al. Lyme neuroborreliosis: do we treat according to guidelines? J Neurol 2017;264:1506–10. 10.1007/s00415-017-8559-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lerdal A, Wahl A, Rustøen T, et al. Fatigue in the general population: a translation and test of the psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the fatigue severity scale. Scand J Public Health 2005;33:123–30. 10.1080/14034940410028406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nordin S, Palmquist E, Nordin M. Psychometric evaluation and normative data for a Swedish version of the Patient Health Questionnaire 15-Item Somatic Symptom Severity Scale. Scand J Psychol 2013;54:112–7. 10.1111/sjop.12029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garratt AM, Stavem K. Measurement properties and normative data for the Norwegian SF-36: results from a general population survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:51 10.1186/s12955-017-0625-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.