Abstract

Purpose

Fluorodeoxyglucose-Positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET), quantified by standardized uptake values (SUV), is one of the most used functional imaging modality in clinical routine. It is widely acknowledged to be strongly associated with Glucose-transporter family (GLUT)-expression in tumors, which mediates the glucose uptake into cells. The present systematic review sought to elucidate the association between GLUT 1 and 3 expression with SUV values in various tumors.

Methods

MEDLINE library was screened for associations between FDG-PET parameters and GLUT correlation cancer up to October 2018.

Results

There were 53 studies comprising 2291 patients involving GLUT 1 expression and 11 studies comprising 405 patients of GLUT 3 expression. The pooled correlation coefficient for GLUT 1 was r = 0.46 (95% CI 0.40–0.52), for GLUT 3 was r = 0.35 (95%CI 0.24–0.46). Thereafter, subgroup analyses were performed. The highest correlation coefficient for GLUT 1 was found in pancreatic cancer r = 0.60 (95%CI 0.46–0.75), the lowest was identified in colorectal cancer with r = 0.21 (95% CI -0.57–0.09).

Conclusion

An overall only moderate association was found between GLUT 1 expression and SUV values derived from FDG-PET. The correlation coefficient with GLUT 3 was weaker. Presumably, the underlying mechanisms of glucose hypermetabolism in tumors are more complex and not solely depended on the GLUT expression.

Introduction

Fluorodeoxyglucose -Positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET) is one of the most used functional imaging modality in clinical practice. The value of this imaging technique is based upon the display of glucose metabolism in vivo [1, 2]. This benefit has been extensively researched, especially in the field of oncologic imaging. The FDG uptake is routinely quantified by standardized uptake values (SUV), which is a robust and reliable imaging biomarker [1, 2].

Malignant tumors tend to show an altered, elevated glucose metabolism based upon aerobic glycolysis compared to normal tissue, which is called Warburg effect [3, 4].

Because of this fact, FDG-PET can be used in clinical routine to aid in discrimination between benign and malignant lesions [5–7], might predict treatment response [8–10] and might also be able to reflect histopathology parameters of tumors [11, 12].

The accumulation of the tracer FDG is acknowledged to be mainly mediated by the Glucose-transporter family (GLUT) [13, 14]. These proteins are located within the cell membranes and regulate the uptake of glucose into cells. According to the literature, especially the subtypes GLUT 1 and GLUT 3 are the most important proteins for the FDG-uptake and are overexpressed in tumors [14].

In brief, a tumor cell needs more glucose for proliferation and because of the ineffective aerobic glycolysis than a physiological cell. Thus, tumors might also express more GLUT proteins than physiological tissues to accumulate more glucose.

Moreover, it was identified that an increased glucose uptake is associated with chemotherapy resistance of gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer cells [15]. A key regulator is hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha, which mediates the metabolic pathways, including GLUT expression [15]. In another study on pancreatic cancers it was identified that GLUT 1 expression was abundantly higher in tumors and it was even the highest expressed protein of metabolic genes [16]. These findings suggest that metabolic protein expression is associated with tumor aggressiveness and treatment response.

This association between SUV and GLUT has been extensively investigated, both in experimental animal studies [17, 18] and as well as in clinical studies using immunohistochemical stainings of tumor specimens [14]. In most studies, GLUT 1 was investigated. Previously, some studies identified a strong positive correlation between GLUT expression and SUV values derived from FDG-PET, as it is hypothetically expected [19, 20]. However, there are also studies, which could not show any significant associations between SUV and GLUT [21]. The exact reason for this discrepancy is not known. Presumably, in some tumors the FDG-PET uptake may be predominantly influenced by GLUT expression. In other malignancies, however, other cellular pathways, such as the expression of hexokinase II, may be more important for FDG uptake.

Moreover, it is postulated that the cellular energy demand and tumor microenvironment show complex interactions, which go beyond a linear association between GLUT expression and FDG uptake alone [13].

The aim of the present analysis was to investigate the associations between GLUT 1 and GLUT 3 expression with SUV values derived from FDG-PET in a systemic review and to provide the first meta analysis of the published data.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition

MEDLINE and SCOPUS libraries were screened for associations between FDG-PET parameters and GLUT correlation cancer up to October 2018. The following search words were used: PET or positron emission tomography and GLUT, SUV or standardized uptake value and GLUT or glucose-transporter. Overall 292 articles were identified.

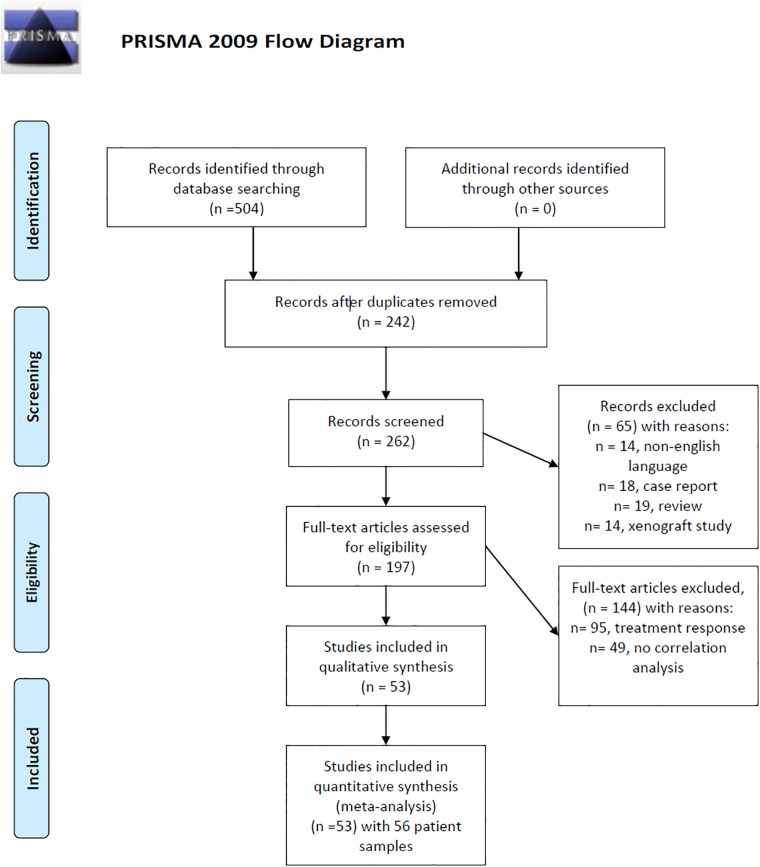

After thorough review and exclusion due to doublets, review articles, case reports, non-English publications, and articles, which not contain correlation coefficients between PET and GLUT, 53 articles were suitable for the meta analysis [19–69]. In these articles 56 patient samples were acquired. Fig 1 displays the PRISMA flow chart of the paper acquisition.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow chart.

An overview of the paper acquisition. Finally, 53 articles were suitable for the analysis. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/joumal.pmed1000097. For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org.

The primary endpoint of the systematic review was the correlation between GLUT-1 and GLUT-3 expression with SUV values derived from FDG-PET.

Studies (or subsets of studies) were included if they satisfied all of the following criteria: (1) patients with tumor with histopathological confirmation and expression analysis of GLUT-1 and/or GLUT-3; (2) FDG-PET quantified by SUV values; (3) correlation analysis between SUV values and GLUT 1 and/or GLUT 3 expression.

Exclusion criteria were (1) systematic review (2) case reports (3) treatment prediction or histopathology performed after treatment (4) non-English language (5) xenograft or mouse/rabbit model studies.

The following data were extracted from the literature: authors, year of publication, study design, tumor entity, GLUT subtype, number of patients, and correlation coefficients.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA) was used for the paper acquisition [70].

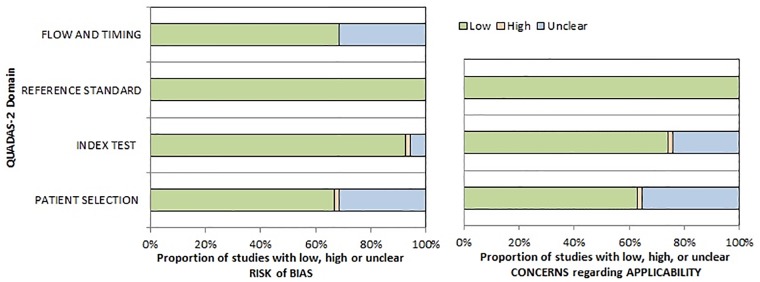

The methodological quality of the acquired studies was independently checked by two observers (HJM and AS) using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Studies (QUADAS 2) instrument according to previous descriptions (Fig 2) [71].

Fig 2. QUADAS-2 quality assessment of the included studies.

There were no possible concerns of the references standard. A small amount of studies showed unclear bias regarding flow and timing, patient selection and index test.

The assessment revealed that a small portion of studies shows an unclear risk of patient selection due to non and or unclear inclusion criteria. Regarding flow and timing, some studies did not indicate whether the histopathology analysis was in a short amount of time after the PET to assure congruent results.

Associations between PET and GLUT expression were analyzed by Spearman’s correlation coefficient. The Pearson’s correlation coefficients in some studies were converted into Spearman’s correlation coefficients, as reported previously [72].

Finally, the meta-analysis was undertaken by using RevMan 5.3 (Computer Program, version 5.3, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen). Heterogeneity was calculated by means of the inconsistency index I2 [73, 74]. Additionally, DerSimonian and Laird random-effects models with inverse-variance weights were used without any further correction [75].

Results

Associations between SUV and GLUT 1

Overall 53 studies with 56 patient samples overall comprising 2291 patients were analyzed for the meta analysis between SUVmax and GLUT 1 expression.

There were 13 (24.5%) prospective and 40 (75.5%) retrospective study designs.

Table 1 displays the included tumor entities of the GLUT 1 analysis.

Table 1. Overview of the included tumor entities of the GLUT 1 analysis.

| Tumor entity | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Lung cancer | 591 (25.8) |

| Head and neck cancer | 216 (9.4) |

| Esophageal Cancer | 191 (8.3) |

| Cervical cancer | 190 (8.3) |

| Breast cancer | 175 (7.6) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 127 (5.5) |

| Lymph node metastasis | 99 (4.3) |

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma | 94 (4.1) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 94 (4.1) |

| Endometrial cancer | 72 (3.1) |

| Sarcoma | 63 (2.8) |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 59 (2.6) |

| Colorectal cancer | 57 (2.5) |

| Mesenchymal uterine tumor | 47 (2.0) |

| Thymic cancer | 44 (1.9) |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 40 (1.8) |

| Glioma | 33 (1.4) |

| Pheochromacytoma | 27 (1.2) |

| Bile duct cancer | 26 (1.1) |

| Malignant melanoma | 19 (0.9) |

| Ovarian cancer | 17 (0.8) |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | 10 (0.5) |

| Total | 2291 (100) |

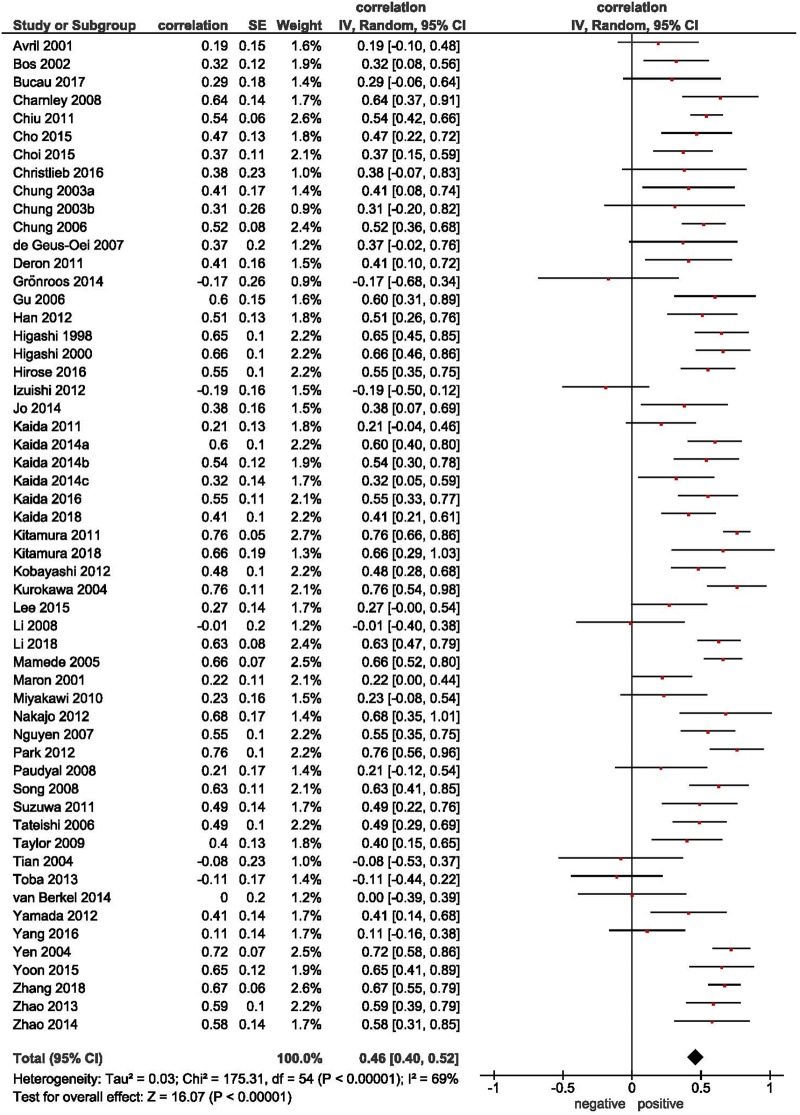

The overall pooled correlation coefficient of the association between SUVmax and GLUT 1 expression was r = 0.46 (95% CI 0.40–0.52) (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Correlation between SUVmax and GLUT 1 expression.

Forrest plots of the correlations coefficients between SUVmax and GLUT 1 in all involved studies (n = 53) comprising 2291 patients. The pooled correlation coefficient was r = 0.46 (95% CI 0.40–0.52).

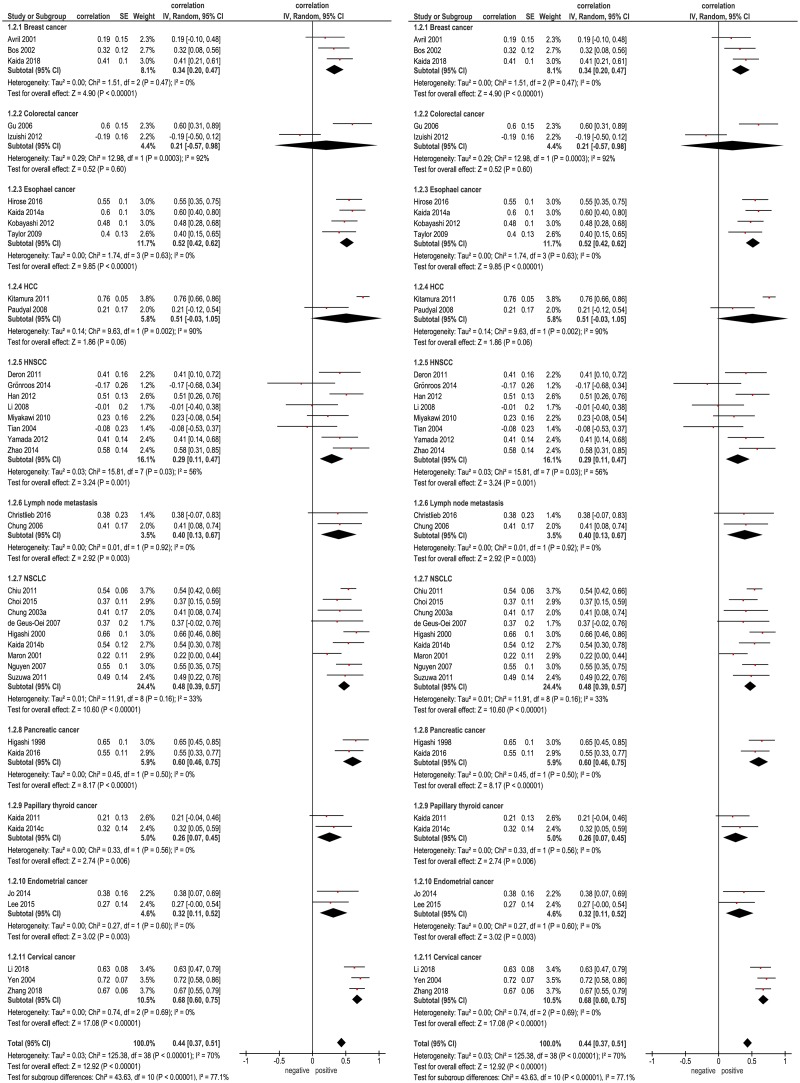

Thereafter, subgroup analyses with tumor entities comprising more than one paper were performed (Fig 4). The highest correlation coefficient was found in pancreatic cancer (r = 0.60, 95%CI 0.46–0.75), and the lowest was identified in colorectal cancer (r = 0.21 (95% CI -0.57–0.09).

Fig 4. Subgroup analyses for the correlation between SUVmax and GLUT 1 expression.

Forrest plots of the correlation coefficients between SUVmax and GLUT 1 in different primary tumors.

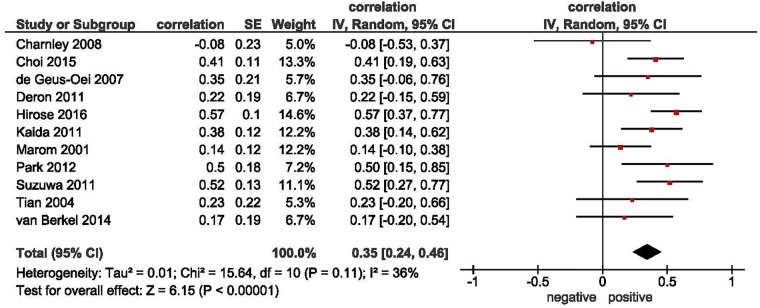

Associations between SUV and GLUT 3

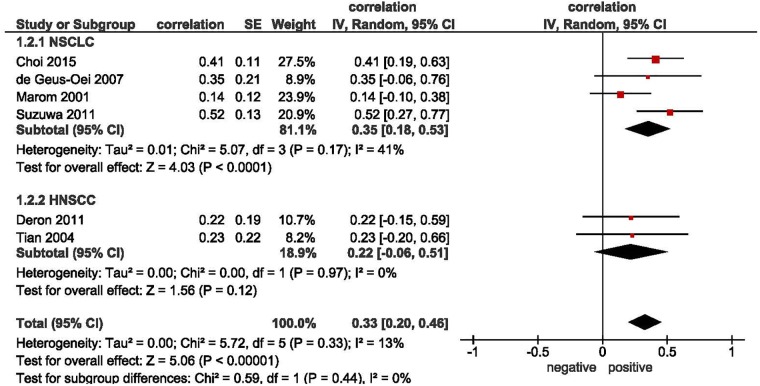

Overall 11 studies comprising 405 patients analyzed associations between SUVmax and GLUT 3 were included into the meta analysis (Fig 5). Table 2 displays the included tumor entities. The pooled correlation coefficient was r = 0.35 (95%CI 0.24–0.46). Only 2 subgroup analyses could be performed: in non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), the correlation coefficient was r = 0.35 (95%CI 0.18–0.53) and in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), it was r = 0.22 (95% CI -0.06–0.51) (Fig 6).

Fig 5. Correlation between SUVmax and GLUT 3 expression.

Forrest plots of the correlations coefficients between SUVmax and GLUT 3 in 11 studies comprising 405 patients. The pooled correlation coefficient was r = 0.35 (95%CI 0.24–0.46).

Table 2. Overview of the included tumor entities of the GLUT 3 analysis.

| Tumor entity | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Non-small cell lung cancer | 188 (46.4) |

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma | 54 (13.3) |

| Esophageal Cancer | 51 (12.6) |

| Head and neck cancer | 46 (11.4) |

| Pheochromacytoma | 27 (6.7) |

| Glioma | 20 (4.9) |

| Malignant melanoma | 19 (4.7) |

| Total | 405 (100) |

Fig 6. Subgroup analyses for the correlation between SUVmax and GLUT 3 expression.

Forrest plots of the correlation coefficients between SUVmax and GLUT 3 in HNSCC and NSCCL subgroups.

Discussion

The present systematic review represents a meta analysis elucidating the associations between SUVmax derived from FDG-PET and GLUT expression in various tumors.

As first reported by Otto Warburg over 90 years ago, a crucial characteristic of tumor cells is an increased glucose uptake resulting in an enhanced glycolytic metabolism [3, 4]. Therefore, various tumors show an overexpression of glucose transporters (GLUTs). There are 13 types of different GLUT proteins, among which, GLUT 1 is the dominant one, which is also abundantly overexpressed in tumors [16, 76].

Previous studies analyzed possible association between SUVmax and GLUT 1 and GLUT 3. Other GLUT subtypes were only sporadically investigated and could therefore not be included into the present analysis.

Early on, it was identified that FDG uptake might be associated with GLUT expression in studies investigating lung cancer and pancreatic carcinoma [36, 37, 77]. Thus, nowadays, it is an acknowledged fact that GLUT expression is one of the main mediators of FDG uptake in tumors.

However, in the present meta analysis only a moderate association was identified between SUVmax and GLUT 1 and a weak correlation between SUVmax and GLUT 3. This fact indicates that the interactions between glucose hypermetabolism displayed by FDG-PET and glucose uptake into the cells are more complex than the sole amount of GLUT expression within the cell membranes [13]. Thus, other important proteins of the glucose metabolism, such as the hexokinase II protein might have a crucial influence on the SUV value, which has been shown in several tumor entities [78, 79]. Moreover, the FDG uptake visualized via PET might be influenced by very complex interactions of the tumor microenvironment, including inflammatory cells, extracellular matrix, microvessel density and other factors. This might be some reasons of the identified results in the present analysis.

Interestingly, the correlations between GLUT 1 and SUVmax varied significantly in different tumors. As seen, it was strong in cervical and pancreatic cancers, moderate in hepatocellular carcinoma, esophageal cancer and NSCLC, and weak in HNSCC, colorectal cancer, endometrial carcinoma and papillary thyroid cancer.

The exact cause of this phenomenon is unclear. Presumably, the above discussed complex interactions of tumor microenvironment differ between tumor types and might also influence the investigated linear association between GLUT expression and SUVmax.

For other tumor entities, such as gastric cancer, renal cell carcinoma, or urothel carcinomas, to date, there are no reports regarding associations between SUVmax and GLUT 1 or 3.

According to the literature, GLUT expression is not only specific for tumor cells. So GLUT 1 is also expressed on erythrocytes and immune cells, which induces FDG uptake also in benign diseases, for example such as lung fibrosis [14] and lung inflammatory diseases [80]. However, the inflammatory tissues might express more less GLUT 1 and consecutively display a lower SUV value than malignant tissues [81].

Moreover, a small amount of tumors might express less GLUT proteins and are, therefore, negative on PET studies, which is a very important reason for false negativity of FDG-PET. For example, this was shown in lymph node staging in lung cancer patients [82, 83]. Other reasons for PET negativity are small tumor sizes and some good differentiated tumor types [84]. Furthermore, there are some tumor entities, which are inherently known to have a low FDG uptake despite their malignant nature, such as bronchioalveolar cell carcinoma and lung carcinoids, which is believed to be causes by none or low GLUT 1 expression [85]. Consecutively, no tumors entities with such a behavior could be included into the present study.

In various studies, the important prognostic benefit of SUV values derived from PET was elucidated in several tumor entities. For example, in lung cancer patients, a higher SUVmax indicates poorer overall survival and local control as well as higher chance for distant metastases [86]. Similar results were reported for head and neck cancer [87], soft tissue sarcomas [88], and breast cancer [89]. As another aspect, SUV values can guide to evaluate treatment response, for example shown in breast cancer patients after neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy [90].

These findings are corroborated by recent meta analyses investigating the prognostic relevance of GLUT 1 and GLUT 3 expression in tumors [91–95]. So, an overexpression of these GLUT subtypes was overall associated with a poorer prognosis in various tumors, indicated by a hazard radio of 1.63 for GLUT 1 and 1.83 for GLUT 3 [91]. This association can at last be applied to pancreatic carcinoma, gastric cancers, colorectal carcinomas, esophageal cancer, lung cancer, ovarian and uterine cancer, and oral squamous cell carcinoma [91–94]. For other tumor entities data are still lacking. Presumably, the prognostic performance of FDG-PET and GLUT expression might be linked by the associations between these parameters.

Furthermore, FDG-PET is associated with other histopathology parameters in tumors. For example, SUVmax moderately correlated with proliferation index Ki67, and might therefore be a surrogate parameter of the amount of proliferating tumor cells [96]. As another aspect, SUVmax seems to be related to vessel density in tissues, as it was exemplarily shown for lung cancer [97, 98].

Albeit the identified correlation between GLUT 1 and SUV were moderate, FDG-PET might aid in treatment response evaluation of chemotherapy targeting hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha, which is one of the most important mediator of metabolic gene expression including GLUT 1 [15, 16, 99–101]. Preclinical studies also elucidated the possibility of direct GLUT 1 targeting for tumor treatment, which might also be evaluated by FDG-PET. However, clinical studies are needed to proof, whether FDG-PET is capable in reflecting these treatment changes.

Moreover, FDG-PET might assess metastatic potential of tumors due to its capability to reflect the mentioned metabolic alteration, as was stated in a preclinical study [102].

There are several limitations of the present analysis to address. Firstly, most involved studies were of retrospective nature with inherent known shortcomings of this study design. Moreover, only papers published in English were included. There might be suitable papers in other languages, which were therefore not included. Secondly, different PET scanners, imaging protocols and ROI-analyses were used, which might have an influence on the correlation analysis. Thirdly, GLUT expression was estimated upon histopathology specimens, which might not be representative of the whole tumor, whereas SUVmax derived from PET represents a small area of the tumor with the highest glucose metabolism. Therefore, there might be incongruences between imaging and histopathology. Fourthly, only GLUT 1 and GLUT 3 could be included into the present analysis due to the fact that other GLUT-subtypes have not previously been investigated.

Conclusions

In summary, the present systematic review identified only a moderate association between GLUT 1 expression and SUV values derived from FDG-PET. Moreover, the correlation between SUV and GLUT 1 varied significantly in different tumors. SUV correlated weakly with expression of GLUT 3. Presumably, the underlying mechanisms of glucose hypermetabolism in tumors are more complex and not solely depended on the GLUT expression.

Abbreviations

- FDG-PET

Fluorodeoxyglucose -Positron-emission tomography

- GLUT

Glucose-transporter family

- HNSCC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- NSCLC

non-small-cell lung carcinoma

- SUV

standardized uptake values

Data Availability

The data have been restricted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Leipzig to preserve confidentiality. Researchers may request access to this data by contacting imebmi@medizin.uni-halle.de.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Kwee TC, Basu S, Saboury B, Ambrosini V, Torigian DA, Alavi A. A new dimension of FDG-PET interpretation: assessment of tumor biology. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38(6):1158–70. 10.1007/s00259-010-1713-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Galaly TC, Gormsen LC, Hutchings M. PET/CT for Staging; Past, Present, and Future. Semin Nucl Med. 2018;48(1):4–16. 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science.1956;124:269–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science.1956;123:309–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shao D, Gao Q, Tian XW, Wang SY, Liang CH, Wang SX. Differentiation and diagnosis of benign and malignant testicular lesions using 18F-FDG PET/CT. Eur J Radiol. 2017;93:114–20. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadiprodjo D, Ryan T, Truong MT, Mercier G, Subramaniam RM. Parotid gland tumors: preliminary data for the value of FDG PET/CT diagnostic parameters. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(2):W185–90. 10.2214/AJR.11.7172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohno Y, Koyama H, Matsumoto K, Onishi Y, Takenaka D, Fujisawa Y, et al. Differentiation of malignant and benign pulmonary nodules with quantitative first-pass 320-detector row perfusion CT versus FDG PET/CT. Radiology. 2011;258(2):599–609. 10.1148/radiol.10100245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, Lister TA. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059–68. 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turgeon GA, Iravani A, Akhurst T, Beaulieu A, Callahan JW, Bressel M, et al. What FDG-PET response-assessment method best predicts survival after curative-intent chemoradiation in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): EORTC, PERCIST, Peter Mac or Deauville criteria? J Nucl Med. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farag S, Geus-Oei LF, van der Graaf WT, van Coevorden F, Grunhagen D, Reyners AKL, et al. Early Evaluation of Response Using 18F-FDG PET Influences Management in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Patients Treated with Neoadjuvant Imatinib. J Nucl Med. 2018;59(2):194–6. 10.2967/jnumed.117.196642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surov A, Stumpp P, Meyer HJ, Gawlitza M, Höhn AK, Boehm A, et al. Simultaneous (18)F-FDG-PET/MRI: Associations between diffusion, glucose metabolism and histopathological parameters in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2016;58:14–20. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surov A, Meyer HJ, Schob S, Höhn AK, Bremicker K, Exner M, et al. Parameters of simultaneous 18F-FDG-PET/MRI predict tumor stage and several histopathological features in uterine cervical cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(17):28285–96. 10.18632/oncotarget.16043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wuest M, Hamann I, Bouvet V, Glubrecht D, Marshall A, Trayner B, et al. Molecular Imaging of GLUT1 and GLUT5 in Breast Cancer: A Multitracer Positron Emission Tomography Imaging Study in Mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2018;93(2):79–89. 10.1124/mol.117.110007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Chemaly S, Malide D, Yao J, Nathan SD, Rosas IO, Gahl WA, et al. Glucose transporter-1 distribution in fibrotic lung disease: association with [18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose-PET scan uptake, inflammation, and neovascularization. Chest. 2013;143(6):1685–91. 10.1378/chest.12-1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shukla SK, Purohit V, Mehla K, Gunda V, Chaika NV, Vernucci E, et al. MUC1 and HIF-1alpha Signaling Crosstalk Induces Anabolic Glucose Metabolism to Impart Gemcitabine Resistance to Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(3):392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaika NV, Yu F, Purohit V, Mehla K, Lazenby AJ, DiMaio D, et al. Differential expression of metabolic genes in tumor and stromal components of primary and metastatic loci in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32996 10.1371/journal.pone.0032996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ong LC, Jin Y, Song IC, Yu S, Zhang K, Chow PK. 2-[18F]-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) uptake in human tumor cells is related to the expression of GLUT-1 and hexokinase II. Acta Radiol. 2008;49(10):1145–53. 10.1080/02841850802482486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robey IF, Stephen RM, Brown KS, Baggett BK, Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Regulation of the Warburg effect in early-passage breast cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2008;10(8):745–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitamura S, Yanagi T, Inamura-Takashima Y, Imafuku K, Hata H, Uehara J, et al. Retrospective study on the correlation between 18-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in positron emission tomography-computer tomography and tumor volume, cytological activity as assessed with Ki-67 and GLUT-1 staining in 10 cases of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 201832(7):e285–7. 10.1111/jdv.14821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakajo M, Kajiya Y, Tani A, Yoneda S, Shirahama H, Higashi M, Nakajo M. 18FDG PET for grading malignancy in thymic epithelial tumors: significant differences in 18FDG uptake and expression of glucose transporter-1 and hexokinase II between low and high-risk tumors: preliminary study. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(1):146–51. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grönroos TJ, Lehtiö K, Söderström KO, Kronqvist P, Laine J, Eskola O, et al. Hypoxia, blood flow and metabolism in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck: correlations between multiple immunohistochemical parameters and PET. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:876 10.1186/1471-2407-14-876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avril N, Menzel M, Dose J, Schelling M, Weber W, Jänicke F, et al. Glucose metabolism of breast cancer assessed by 18F-FDG PET: histologic and immunohistochemical tissue analysis. J Nucl Med. 2001;42(1):9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bos R, van Der Hoeven JJ, van Der Wall E, van Der Groep P, van Diest PJ, Comans EF, et al. Biologic correlates of (18)fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in human breast cancer measured by positron emission tomography. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(2):379–87. 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bucau M, Laurent-Bellue A, Poté N, Hentic O, Cros J, Mikail N, et al. 18F-FDG Uptake in Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumors Correlates with Both Ki-67 and VHL Pathway Inactivation. Neuroendocrinology. 2018;106(3):274–82. 10.1159/000480239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charnley N, Airley R, Du Plessis D, West C, Brock C, Barnett C, et al. No relationship between 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and expression of Glut-1 and -3 and hexokinase I and II in high-grade glioma. Oncol Rep. 2008;20(3):537–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiu CH, Yeh YC, Lin KH, Wu YC, Lee YC, Chou TY, Tsai CM. Histological subtypes of lung adenocarcinoma have differential 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptakes on the positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(10):1697–703. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318226b677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho MH, Park CK, Park M, Kim WK, Cho A, Kim H. Clinicopathologic Features and Molecular Characteristics of Glucose Metabolism Contributing to 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose Uptake in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141413 10.1371/journal.pone.0141413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi WH, Yoo IeR, O JH, Kim TJ, Lee KY, Kim YK. Is the Glut expression related to FDG uptake in PET/CT of non-small cell lung cancer patients? Technol Health Care. 2015;23 Suppl 2:S311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christlieb SB, Strandholdt CN, Olsen BB, Mylam KJ, Larsen TS, Nielsen AL, et al. Dual time-point FDG PET/CT and FDG uptake and related enzymes in lymphadenopathies: preliminary results. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43(10):1824–36. 10.1007/s00259-016-3385-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung JK, Lee YJ, Kim SK, Jeong JM, Lee DS, Lee MC. Comparison of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake with glucose transporter-1 expression and proliferation rate in human glioma and non-small-cell lung cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2004;25(1):11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung JH, Lee WW, Park SY, Choe G, Sung SW, Chung JK, et al. FDG uptake and glucose transporter type 1 expression in lymph nodes of non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32(9):989–95. 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Geus-Oei LF, van Krieken JH, Aliredjo RP, Krabbe PF, Frielink C, Verhagen AF, et al. Biological correlates of FDG uptake in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;55(1):79–87. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deron P, Vangestel C, Goethals I, De Potter A, Peeters M, Vermeersch H, Van de Wiele C. FDG uptake in primary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. The relationship between overexpression of glucose transporters and hexokinases, tumour proliferation and apoptosis. Nuklearmedizin. 2011;50(1):15–21. 10.3413/nukmed-0324-10-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu J, Yamamoto H, Fukunaga H, Danno K, Takemasa I, Ikeda M, et al. Correlation of GLUT-1 overexpression, tumor size, and depth of invasion with 18F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake by positron emission tomography in colorectal cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(12):2198–205. 10.1007/s10620-006-9428-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han MW, Lee HJ, Cho KJ, Kim JS, Roh JL, Choi SH, et al. Role of FDG-PET as a biological marker for predicting the hypoxic status of tongue cancer. Head Neck. 2012;34(10):1395–402. 10.1002/hed.21945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higashi T, Tamaki N, Torizuka T, Nakamoto Y, Sakahara H, Kimura T, et al. FDG uptake, GLUT-1 glucose transporter and cellularity in human pancreatic tumors. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(10):1727–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higashi K, Ueda Y, Sakurai A, Mingwang X, Xu L, Murakami M, et al. Correlation of Glut-1 glucose transporter expression with [(18)F]FDG uptake in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27(12):1778–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Izuishi K, Yamamoto Y, Sano T, Takebayashi R, Nishiyama Y, Mori H, et al. Molecular mechanism underlying the detection of colorectal cancer by 18F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(2):394–400. 10.1007/s11605-011-1727-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jo MS, Choi OH, Suh DS, Yun MS, Kim SJ, Kim GH, Jeon HN. Correlation between expression of biological markers and [F]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in endometrial cancer. Oncol Res Treat. 2014;37(1–2):30–4. 10.1159/000358163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaida H, Hiromatsu Y, Kurata S, Kawahara A, Hattori S, Taira T, et al. Relationship between clinicopathological factors and fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2011;32(8):690–8. 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32834754f1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaida H, Kawahara A, Hayakawa M, Hattori S, Kurata S, Fujimoto K, et al. The difference in relationship between 18F-FDG uptake and clinicopathological factors on thyroid, esophageal, and lung cancers. Nucl Med Commun. 2014;35(1):36–43. 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaida H, Azuma K, Kawahara A, Yasunaga M, Kitasato Y, Hattori S, et al. The correlation between FDG uptake and biological molecular markers in pancreatic cancer patients. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85(10):1804–10. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaida H, Azuma K, Toh U, Kawahara A, Sadashima E, Hattori S, et al. Correlations between dual-phase 18F-FDG uptake and clinicopathologic and biological markers of breast cancer. Hell J Nucl Med. 2018;21(1):35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kitamura K, Hatano E, Higashi T, Narita M, Seo S, Nakamoto Y, et al. Proliferative activity in hepatocellular carcinoma is closely correlated with glucose metabolism but not angiogenesis. J Hepatol. 2011;55(4):846–57. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobayashi M, Kaida H, Kawahara A, Hattori S, Kurata S, Hayakawa M, et al. The relationship between GLUT-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor expression and 18F-FDG uptake in esophageal squamous cell cancer patients. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37(5):447–52. 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31823924bb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kurokawa T, Yoshida Y, Kawahara K, Tsuchida T, Okazawa H, Fujibayashi Y, et al. Expression of GLUT-1 glucose transfer, cellular proliferation activity and grade of tumor correlate with [F-18]-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake by positron emission tomography in epithelial tumors of the ovary. Int J Cancer. 2004;109(6):926–32. 10.1002/ijc.20057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee DW, Chong GO, Lee YH, Hong DG, Cho YL, Jeong SY, et al. Role of SUVmax and GLUT-1 Expression in Determining Tumor Aggressiveness in Patients With Clinical Stage I Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(5):843–9. 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li SJ, Guo W, Ren GX, Huang G, Chen T, Song SL. Expression of Glut-1 in primary and recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, and compared with 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose accumulation in positron emission tomography. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(3):180–6. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mamede M, Higashi T, Kitaichi M, Ishizu K, Ishimori T, Nakamoto Y, et al. [18F]FDG uptake and PCNA, Glut-1, and Hexokinase-II expressions in cancers and inflammatory lesions of the lung. Neoplasia. 2005;7(4):369–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marom EM, Aloia TA, Moore MB, Hara M, Herndon JE 2nd, Harpole DH Jr, et al. Correlation of FDG-PET imaging with Glut-1 and Glut-3 expression in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2001;33(2–3):99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miyawaki A, Ikeda R, Hijioka H, Ishida T, Ushiyama M, Nozoe E, Nakamura N. SUVmax of FDG-PET correlates with the effects of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2010;23(5):1205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen XC, Lee WW, Chung JH, Park SY, Sung SW, Kim YK, et al. FDG uptake, glucose transporter type 1, and Ki-67 expressions in non-small-cell lung cancer: correlations and prognostic values. Eur J Radiol. 2007;62(2):214–9 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park SG, Lee JH, Lee WA, Han KM. Biologic correlation between glucose transporters, hexokinase-II, Ki-67 and FDG uptake in malignant melanoma. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39(8):1167–72. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paudyal B, Paudyal P, Oriuchi N, Tsushima Y, Nakajima T, Endo K. Clinical implication of glucose transport and metabolism evaluated by 18F-FDG PET in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2008;33(5):1047–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Song YS, Lee WW, Chung JH, Park SY, Kim YK, Kim SE. Correlation between FDG uptake and glucose transporter type 1 expression in neuroendocrine tumors of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2008;61(1):54–60. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suzawa N, Ito M, Qiao S, Uchida K, Takao M, Yamada T, Takeda K, Murashima S. Assessment of factors influencing FDG uptake in non-small cell lung cancer on PET/CT by investigating histological differences in expression of glucose transporters 1 and 3 and tumour size. Lung Cancer. 2011;72(2):191–8. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tateishi U, Yamaguchi U, Seki K, Terauchi T, Arai Y, Hasegawa T. Glut-1 expression and enhanced glucose metabolism are associated with tumour grade in bone and soft tissue sarcomas: a prospective evaluation by [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33(6):683–91. 10.1007/s00259-005-0044-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor MD, Smith PW, Brix WK, Wick MR, Theodosakis N, Swenson BR, Kozower BD, Jones DR. Correlations between selected tumor markers and fluorodeoxyglucose maximal standardized uptake values in esophageal cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35(4):699–705. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.11.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tian M, Zhang H, Nakasone Y, Mogi K, Endo K. Expression of Glut-1 and Glut-3 in untreated oral squamous cell carcinoma compared with FDG accumulation in a PET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31(1):5–12. 10.1007/s00259-003-1316-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Toba H, Kondo K, Sadohara Y, Otsuka H, Morimoto M, Kajiura K, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography and the relationship between fluorodeoxyglucose uptake and the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, glucose transporter-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor in thymic epithelial tumours. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44(2):e105–12. 10.1093/ejcts/ezt263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Berkel A, Rao JU, Kusters B, Demir T, Visser E, Mensenkamp AR, et al. Correlation between in vivo 18F-FDG PET and immunohistochemical markers of glucose uptake and metabolism in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(8):1253–9. 10.2967/jnumed.114.137034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang L, Sun H, Du S, Xu W, Xin J, Guo Q. Evaluation of 18F-FDG PET/CT parameters for reflection of aggressiveness and prediction of prognosis in early-stage cervical cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2018;39(11):1045–52. 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li-Ou Z, Hong-Zan S, Xiao-Xi B, Zhong-Wei C, Zai-Ming L, Jun X, Qi-Yong G. Correlation Between Tumor Glucose Metabolism and Multiparametric Functional MRI (IVIM and R2*) Metrics in Cervical Carcinoma: Evidence From Integrated 18F-FDG PET/MR. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018. November 3 10.1002/jmri.26557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamada T, Uchida M, Kwang-Lee K, Kitamura N, Yoshimura T, Sasabe E, Yamamoto T. Correlation of metabolism/hypoxia markers and fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113(4):464–71. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang HJ, Xu WJ, Guan YH, Zhang HW, Ding WQ, Rong L, et al. Expression of Glut-1 and HK-II in Pancreatic Cancer and Their Impact on Prognosis and FDG Accumulation. Transl Oncol. 2016;9(6):583–91. 10.1016/j.tranon.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yen TC, See LC, Lai CH, Yah-Huei CW, Ng KK, Ma SY, et al. 18F-FDG uptake in squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix is correlated with glucose transporter 1 expression. J Nucl Med. 2004;45(1):22–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoon SO, Jeon TJ, Park JS, Ryu YH, Lee JH, Yoo JS, et al. Analysis of the roles of glucose transporter 1 and hexokinase 2 in the metabolism of glucose by extrahepatic bile duct cancer cells. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40(3):e178–82. 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhao Z, Yoshida Y, Kurokawa T, Kiyono Y, Mori T, Okazawa H. 18F-FES and 18F-FDG PET for differential diagnosis and quantitative evaluation of mesenchymal uterine tumors: correlation with immunohistochemical analysis. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(4):499–506. 10.2967/jnumed.112.113472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao K, Yang SY, Zhou SH, Dong MJ, Bao YY, Yao HT. Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in laryngeal carcinoma is associated with the expression of glucose transporter-1 and hypoxia-inducible-factor-1α and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway. Oncol Lett. 2014;7(4):984–90. 10.3892/ol.2014.1877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–36. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chalkidou A, Landau DB, Odell EW, Cornelius VR, O‘Doherty MJ, Marsden PK. Correlation between Ki-67 immunohistochemistry and 18F-fluorothymidine uptake in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(18):3499–513. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leeflang MM, Deeks JJ, Gatsonis C, Bossuyt PM. Systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(12):889–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zamora J, Abraira V, Muriel A, Khan K, Coomarasamy A. Meta-DiSc: A software for meta-analysis of test accuracy data. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2006;6:31 10.1186/1471-2288-6-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Joost HG, Thorens B. The extended GLUT-family of sugar/polyol transport facilitators: nomenclature, sequence characteristics, and potential function of its novel members (review). Mol Membr Biol. 2001;18(4):247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reske SN, Grillenberger KG, Glatting G, Port M, Hildebrandt M, Gansauge F, Beger HG. Overexpression of glucose transporter 1 and increased FDG uptake in pancreatic carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 1997;38(9):1344–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rasche L, Angtuaco E, McDonald JE, Buros A, Stein C, Pawlyn C, Thanendrarajan S, et al. Low expression of hexokinase-2 is associated with false-negative FDG-positron emission tomography in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2017;130(1):30–4. 10.1182/blood-2017-03-774422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maddalena F, Lettini G, Gallicchio R, Sisinni L, Simeon V, Nardelli A, et al. Evaluation of Glucose Uptake in Normal and Cancer Cell Lines by Positron Emission Tomography. Mol Imaging. 2015;14:490–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang ZG, Yu MM, Han Y, Wu FY, Yang GJ, Li DC, Liu SM. Correlation of Glut-1 and Glut-3 expression with F-18 FDG uptake in pulmonary inflammatory lesions. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(48):e5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mochizuki T, Tsukamoto E, Kuge Y, Kanegae K, Zhao S, Hikosaka K, et al. FDG uptake and glucose transporter subtype expressions in experimental tumor and inflammation models. J Nucl Med. 2001;42(10):1551–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baek HJ, Chung JH, Park JH, Zo JI, Cheon GJ, Choi CW, et al. FDG-PET in Mediastinal Nodal Staging of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: Correlation of False Results with Histopathologic Finding. Cancer Res Treat. 2003;35(3):232–8. 10.4143/crt.2003.35.3.232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Taira N, Atsumi E, Nakachi S, Takamatsu R, Yohena T, Kawasaki H, et al. Comparison of GLUT-1, SGLT-1, and SGLT-2 expression in false-negative and true-positive lymph nodes during the 18F-FDG PET/CT mediastinal nodal staging of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2018;123:30–35. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kumar R, Chauhan A, Zhuang H, Chandra P, Schnall M, Alavi A. Clinicopathologic factors associated with false negative FDG-PET in primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;98(3):267–74. 10.1007/s10549-006-9159-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cheran SK, Nielsen ND, Patz EF Jr. False-negative findings for primary lung tumors on FDG positron emission tomography: staging and prognostic implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(5):1129–32. 10.2214/ajr.182.5.1821129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dong M, Liu J, Sun X, Xing L. Prognostic significance of SUVmax on pretreatment 18F-FDG PET/CT in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy: A meta-analysis. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2017;61(5):652–9. 10.1111/1754-9485.12599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Huang Y, Feng M, He Q, Yin J, Xu P, Jiang Q, Lang J. Prognostic value of pretreatment 18F-FDG PET-CT for nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(17):e6721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li YJ, Dai YL, Cheng YS, Zhang WB, Tu CQ. Positron emission tomography (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake and prognosis in patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma: A meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(8):1103–14. 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kitajima K, Miyoshi Y, Yamano T, Odawara S, Higuchi T, Yamakado K. Prognostic value of FDG-PET and DWI in breast cancer. Ann Nucl Med. 2018;32(1):44–53. 10.1007/s12149-017-1217-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee HW, Lee HM, Choi SE, Yoo H, Ahn SG, Lee MK, et al. The Prognostic Impact of Early Change in 18F-FDG PET SUV After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients with Locally Advanced Breast Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(8):1183–8. 10.2967/jnumed.115.166322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen X, Lu P, Zhou S, Zhang L, Zhao JH, Tang JH. Predictive value of glucose transporter-1 and glucose transporter-3 for survival of cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(8):13206–13. 10.18632/oncotarget.14570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhao ZX, Lu LW, Qiu J, Li QP, Xu F, Liu BJ, et al. Glucose transporter-1 as an independent prognostic marker for cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;9(2):2728–38. 10.18632/oncotarget.18964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li CX, Sun JL, Gong ZC, Lin ZQ, Liu H. Prognostic value of GLUT-1 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma: A prisma-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(45):e5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sharen G, Peng Y, Cheng H, Liu Y, Shi Y, Zhao J. Prognostic value of GLUT-1 expression in pancreatic cancer: results from 538 patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(12):19760–7. 10.18632/oncotarget.15035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang J, Wen J, Tian T, Lu Z, Wang Y, Wang Z, et al. GLUT-1 overexpression as an unfavorable prognostic biomarker in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(7):11788–96. 10.18632/oncotarget.14352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Deng SM, Zhang W, Zhang B, Chen YY, Li JH, Wu YW. Correlation between the Uptake of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) and the Expression of Proliferation-Associated Antigen Ki-67 in Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129028 10.1371/journal.pone.0129028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Koh YW, Lee SJ, Park SY. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography is correlated with the pathological necrosis and decreased microvessel density in lung adenocarcinomas. Ann Nucl Med. 2018. October 15 10.1007/s12149-018-1309-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Surov A, Meyer HJ, Wienke A. Standardized Uptake Values Derived from 18F-FDG PET May Predict Lung Cancer Microvessel Density and Expression of KI 67, VEGF, and HIF-1α but Not Expression of Cyclin D1, PCNA, EGFR, PD L1, and p53. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2018;9257929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Masoud GN, Li W. HIF-1α pathway: role, regulation and intervention for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5(5):378–89. 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Evans A, Bates V, Troy H, Hewitt S, Holbeck S, Chung YL, et al. Glut-1 as a therapeutic target: increased chemoresistance and HIF-1-independent link with cell turnover is revealed through COMPARE analysis and metabolomic studies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61(3):377–93. 10.1007/s00280-007-0480-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lai IL, Chou CC, Lai PT, Fang CS, Shirley LA, Yan R, et al. Targeting the Warburg effect with a novel glucose transporter inhibitor to overcome gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(10):2203–13. 10.1093/carcin/bgu124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 102.Zhang M, Jiang H, Zhang R, Xu H, Jiang H, Pan W, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of 18F-FDG/18F-FMISO-based Micro PET in monitoring hepatic metastasis of colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):17832 10.1038/s41598-018-36238-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data have been restricted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Leipzig to preserve confidentiality. Researchers may request access to this data by contacting imebmi@medizin.uni-halle.de.