Abstract

Objective

Postnatal care (PNC) is essential for preventing maternal and newborn deaths; however, it still remains less well recognised in low-income and middle-income countries. This study was aimed to explore geographical patterns and identify the determinants of PNC usage among women aged 15–49 years in Ethiopia.

Methods

A secondary data analysis was conducted using the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. A total of 7193 women were included in this analysis. We employed spatial scan statistics to detect spatial inequalities of PNC usage among women. A multilevel binary logistic regression model was fitted to identify factors associated with women’s PNC.

Results

The prevalence of PNC usage among women was 6.9% (95% CI 6.3% to 7.5%). The SaTScan spatial analysis identified three most likely clusters with low rates of PNC use namely southwestern Ethiopia (log likelihood ratio (LLR)=18.07, p<0.0001), southeast Ethiopia (LLR=14.29, p<0.001) and eastern Ethiopia (LLR=10.18, p=0.024). Women with no education (Adjusted Odd Ratio (AOR)=0.55, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.84) and in the poorest wealth quantile (AOR=0.55, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.78) were less likely to use PNC, while women aged 35–49 years (AOR: 1.75, 95% CI 1.01 to 3.04) and with at least four antenatal care (ANC) visits (AOR=2.37, 95% CI 1.71 to 3.29) were more likely to use PNC.

Conclusion

PNC usage remains a public health problem and has spatial variations at regional levels in the country. Low prevalence of PNC was detected in the Somali, Oromia, Gambella and Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region (SNNPR) regions. Women with low educational status, old age, being in poorest wealth quantile and history of ANC visits were significantly associated with PNC usage. Hence, it is better to strengthen maternal health programmes that give special emphasis on health promotion with a continuum of care during pregnancy.

Keywords: postnatal care, demography and health survey, maternal medicine, primary care, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Having used a recent national community-based survey, the study has the potential to inform policy-makers, planners and programmers to design appropriate intervention at national and regional levels.

As a cross-sectional survey, our works are unable to draw causal conclusions. However, our method used multilevel modelling which took into account the effect of clustering to better estimate the level of association of the study factors with the outcome.

The study was based on self-reports of respondents and provided no validation of obtaining information with an objective source. This might lead to recall bias which in turn may make the findings ungeneralisable.

As the work is based on a secondary data analysis, some important variables, such as cultural beliefs, when women are allowed to leave the house in the postpartum period, roles of husbands in maternal health decision-making and perceptions about whether the pregnancy is a medical issue warranting clinical visits were not available for analysis.

In this study, the geographical coordinates of enumeration areas (EAs) were displaced by up to 5 km to prevent the identification of respondents or the community. This could affect the cluster effect in the spatial analysis. So, those issues should be interpreted with caution.

Background

In 2015, roughly 66% of the world’s maternal mortality was found in Sub-Saharan Africa.1 2 A report in Ethiopia showed the presence of a large proportion of maternal and neonatal deaths although the health system is focusing on improving maternal health.3 4

Postnatal care (PNC) is used as an indicator of maternal healthcare in the postpartum period in Ethiopia.5 According to the WHO, a postnatal period is so critical for both the mother and baby that all women and newborns receive at least three postnatal contacts following delivery.6–8 PNC is an opportunity for providers to facilitate healthy breast-feeding practices, screen for postpartum depression, monitor the newborn’s growth and overall health status, treat childbirth-related complications, counsel women about their family planning options, and refer the mother and baby for specialised care if necessary, among other services. In Ethiopia, maternal mortality rate decreased from 897 to 412 per 100 000 between 2000 and 2016,7 while antenatal care (ANC) increased from 10.4% to 32%.9 10 However, PNC usage remains very low as only 13% to 26% of women receive it.11

Studies in low-income and middle-income countries have looked into the factors associated with PNC usage. Mother’s sociodemographic characteristics, including household wealth status, maternal education, maternal occupation and residence were positively associated with PNC.12 13 In addition, history of ANC, place of delivery and mother’s knowledge of postpartum danger signs and symptoms were important predictors of PNC service usage.14 On the other hand, PNC service usage depends on birth-related complication that could end in maternal and neonatal deaths.15–17

Increasingly, efforts have been made to improve health coverage, and expenditures expanded universally; however, important maternal health inequities are concealed in smaller administrative areas. Currently, the Ethiopian healthcare strategy is focused on primary healthcare units including health centres, health stations, health posts and private clinics. However, it was noted that the magnitude of maternal health services has been geographically heterogeneous. Additionally, the extent of key barriers to PNC usage which cause maternal and neonatal death during the postnatal period is unexplained.

A spatial study is important in identifying high-risk geographical areas within a community; it also helps to understand what drives disparities in low maternal health services and suggests community-based interventions in the areas. Thus, understanding the spatial epidemiology of PNC is crucial for evidence-based decision making to improve maternal health services. However, studies on the spatial epidemiology of women’s PNC are limited, and the driving factors are poorly understood in Ethiopia. Hence, this study aimed to contribute pieces of evidence on the geographical pattern of PNC and associated factors among women.

Methods

Data source

A secondary data analysis of the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS 2016) data was conducted. Ethiopia is located in the horn of Africa, the second most populous country in the continent. Administratively, Ethiopia is subdivided into 11 geographical regions which are subdivided into zones and districts. The districts are further subdivided into kebeles (the smallest administrative units). Based on the 2007 population and housing census of Ethiopia, each kebele administration was subdivided again into enumeration areas (EAs). These were used as the primary sampling units for the fourth EDHS.18 19 In Ethiopia, healthcare service has been improved after the implementation of the Health Sector Development Plan through decentralisation into a three-tier structure. Health centres mainly provide preventative and basic curative services with a referral system to the nearest high level of care.4 Primary healthcare including PNC is offered free of charge to all women. The health centres are staffed by health extension workers and health development army to improve the universal primary healthcare (PHC) coverage at the lowest level of administration.

In recent years, Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) is a nationally representative survey designed to provide information on health indicators at the national (urban and rural) and regional levels. As a result, the 2016 EDHS was conducted by the Central Statistical Agency with a funding support from the Government of Ethiopia, the US Agency for International Development, the Government of the Netherlands, the Global Fund, Irish Aid, the World Bank, the United Nations Population Fund, Unicef and UN Women. Inner City Fund (ICF) International also provided technical support.20 The data used for this study were drawn from 2016 EDHS. The surveys used a stratified two-stage cluster sampling, which was conducted every 5 years and the 2016 EDHS was the fourth survey in Ethiopia. In the first stage, a total of 645 EAs (202 in urban and 443 in rural areas) were selected with a probability proportional to EAs size probability proportional to size (PPS) from the complete list of 84 915 EAs created for the 2007 PHC sampling frame. In the second stage, a fixed number of 28 households per cluster was chosen with an equal probability systematic selection from the newly created household listing.

The source population of this study was any women in childbearing age who gave birth in the last 5 years preceding the survey in Ethiopia, and the study population was any women in childbearing age that gave birth in the last 5 years preceding the survey in the selected EAs. In this survey, a total of 16 650 households were successfully interviewed with a response rate of 98% and a total of 7193 women in childbearing age who gave birth in the last 5 years before the survey were included in this analysis. The 2016 EDHS data sets were downloaded in SPSS format with permission from the Measure DHS website (http://www.dhsprogram.com).

The outcome variable of this study is PNC usage status among reproductive age women. In this study, PNC usage is defined as women’s health check-up after discharge from a health facility or home delivery within the first 6 weeks (42 days) after delivery.8 21 The survey collected these data from mothers’ verbal reports on whether they had received PNC after discharge from a health facility or delivery at home. We categorised this variable into ‘Yes’ (when a woman had received PNC at health facility) and otherwise ‘No’. The independent variables of this study such as sociodemographic variables (age, educational level, occupation, religion, residence, region and household wealth quintile) and maternal reproductive health-related factors (place of delivery, number of ANC visits, sex of the child) were extracted accordingly. The choice of explanatory variables was guided by the literature.

Data management and statistical analysis

After data extraction, further coding and analysis were done using STATA V.14 software. Sample weights were used to avoid geographical strata selection variability and for non-responses. The detailed explanation of the weighting procedure was provided elsewhere in the EDHS final report.22

Descriptive measures were used to summarise the overall characteristics of the participants in the study area. A multilevel binary logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the measures between each of the independent variables (mother and household characteristics) and the likelihood of mothers using PNC services. The rationales for using multilevel modelling were due to the multistage cluster sampling procedure, individual women were nested within clusters. We used regions as cluster variables. Hence, the likelihood of women seeking maternal health services is likely to be correlated to the cluster members. Variables that had a relationship with PNC usage (p<0.25) were considered for the final model. ORs with a 95 %CI were used to declare statistical significance.

Spatial analysis

The global spatial autocorrelation was assessed using the Global Moran’s I statistic (Moran’s I) to evaluate whether the pattern was clustered, dispersed or random across the study area using ArcGIS V.10.3.23 A positive value for Moran’s Index indicates a clustered pattern of PNC, while a negative value for Moran’s Index indicates a dispersed pattern.23 24

In the presence of positive global spatial autocorrelation, we employed a purely spatial scan statistics using a Bernoulli probability model to detect local clusters with a low or high rate of PNC.25 The SaTScan V.9.4 software was used for the local cluster detection analysis.25 26 It uses a circular window which moves systematically throughout the study area to identify a significant SaTScan clustering of women who received PNC. The default maximum spatial cluster size of <50% of the population was used as an upper limit which allowed to detect both small and large clusters and ignored clusters that contained more than the maximum limit. For each potential cluster, a log-likelihood ratio test statistic was used to determine if the number of observed cases within the potential cluster was significantly higher than expected or not. The circle with the maximum likelihood ratio test statistic was defined as the most likely (primary) cluster, then compared with the overall distribution of maximum values. The primary and secondary clusters were identified and assigned p values and ranked based on their likelihood ratio test on the basis of the 999 Monte Carlo replications.27 28

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients and the public were not involved in this secondary data analysis although for the original project from which data were obtained, patient and public involvement statement was essential since biomarkers such as anthropometry, anaemia and HIV testing were collected from households.22

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

A total of 7193 women aged 15–49 years and had at least one birth in the 5 years before the study were included in the analysis. The majority of 6621 (87.2%) of the respondents were rural residents with a mean age of 29.3 years (SD ±6.9). About 4791 (63.1%) of the respondents had no education and about one-third were in the poorest wealth quintile. The highest number of the participants, 3130 (41.2%) were from Oromia followed by 1633 (21.5%) Amhara and 1601 (21.1%) SNNPR states (table 1).

Table 1.

Postnatal care use by background characteristics among women age 15–49 who had given birth in the 5 years preceding the survey, EDHS 2016

| Background characteristics | Percentage of PNC use | Women PNC use (n) |

||

| Weighted | Unweighted | |||

| Age (years) | 15–19 | 4.4 | 338 | 358 |

| 20–34 | 6.6 | 5291 | 5041 | |

| 35–49 | 5.8 | 1960 | 1794 | |

| Religion | Orthodox Christian | 9.4 | 2882 | 2369 |

| Muslim | 4.0 | 2824 | 3324 | |

| Protestant | 5.5 | 1652 | 1338 | |

| Others* | 0.9 | 232 | 162 | |

| Residence | Urban | 12.1 | 969 | 1512 |

| Rural | 5.5 | 6621 | 5681 | |

| Region | Tigray | 15.6 | 538 | 772 |

| Afar | 4.2 | 71 | 647 | |

| Amhara | 8.0 | 1633 | 764 | |

| Oromia | 3.6 | 3130 | 1031 | |

| Somali | 3.0 | 269 | 806 | |

| Benishangul | 7.4 | 81 | 576 | |

| SNNPR | 6.3 | 1601 | 893 | |

| Gambella | 4.8 | 21 | 534 | |

| Harari | 11.1 | 18 | 411 | |

| Addis Ababa | 13.6 | 198 | 375 | |

| Dire Dawa | 9.1 | 33 | 384 | |

| Maternal education | No education | 4.8 | 4791 | 4359 |

| Primary | 7.7 | 2150 | 1942 | |

| Secondary | 11.9 | 420 | 577 | |

| Higher | 13.5 | 229 | 315 | |

| Husband/partner’s education level | No education | 4.9 | 3345 | 3136 |

| Primary | 6.6 | 2731 | 2160 | |

| Secondary | 9.3 | 612 | 745 | |

| Higher | 10.9 | 376 | 569 | |

| Don’t know | 9.3 | 43 | 52 | |

| Wealth index | Poorest | 3.1 | 1652 | 2428 |

| Poorer | 3.9 | 1654 | 1179 | |

| Middle | 5.9 | 1588 | 1028 | |

| Richer | 8.3 | 1426 | 917 | |

| Richest | 11.8 | 1269 | 1641 | |

| ANC visit | No ANC visit | 2.4 | 2818 | 2481 |

| ANC one to three visits | 6.6 | 2342 | 2092 | |

| ANC at least four visits | 10.5 | 2429 | 2620 | |

| Place of delivery | Health facility | 9.1 | 2408 | 2699 |

| Other than health facility | 5.0 | 5181 | 4494 | |

| Sex of child | Male | 5.8 | 3941 | 3718 |

| Female | 6.8 | 3649 | 3475 | |

| Child wanted | Wanted then | 5.9 | 5573 | 5741 |

| Wanted later | 7.9 | 1321 | 991 | |

| Wanted no more | 6.0 | 695 | 461 | |

| Birth order | 1 | 7.1 | 1434 | 1470 |

| 2–3 | 7.2 | 2281 | 2217 | |

| 4–5 | 6.0 | 1752 | 1638 | |

| 6+ | 5.0 | 2122 | 1868 | |

*Catholic, traditional and other unclassified.

ANC, antenatal care; EDHS, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey; PNC, postnatal care; SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region.

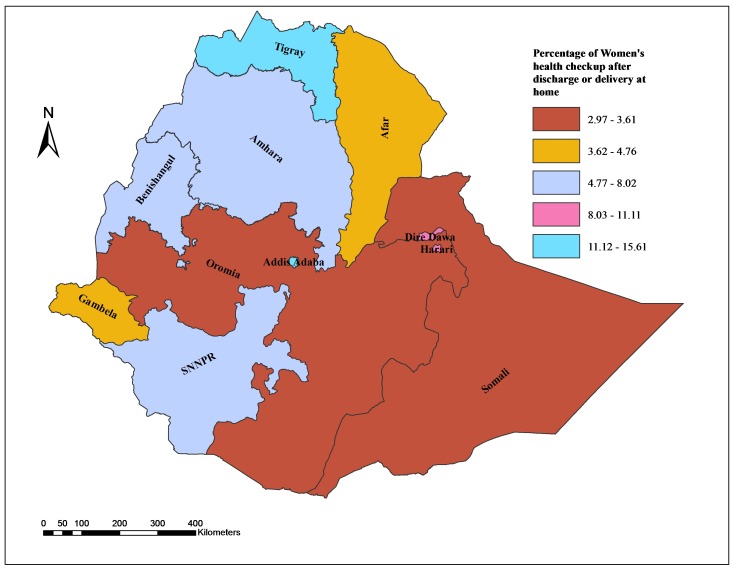

Prevalence of PNC

The prevalence of PNC usage among women was 6.9% (95% CI 6.3% to 7.5%) with 10.6% (95% CI 9.1 to 12.2) in urban and 5.9% (95% CI 5.3 to 6.6)) in rural areas. PNC usage is varied across the regions of the country with a relatively highest prevalence (15%) in Tigray region and the lowest (3%) in Somali. The prevalence of PNC was 10.5% in women with at least four visits of ANC, and 9.1% in women who delivered in health facilities (table 1).

Spatial distribution of PNC usage

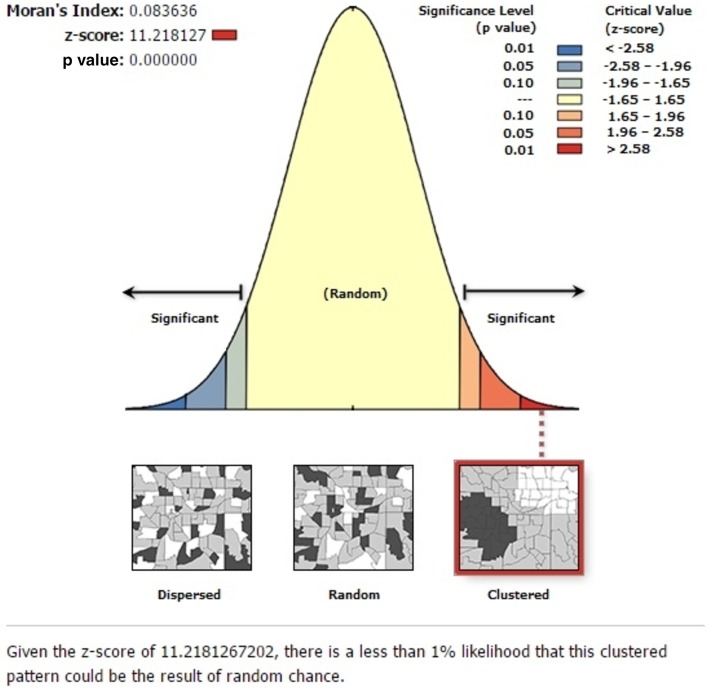

The global spatial autocorrelation analysis revealed a clustering pattern of women’s PNC usage across the study areas (Global Moran’s I=0.084, p value<0.001) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Spatial autocorrelation based on feature locations and attribute values using the Global Moran’s I statistic.

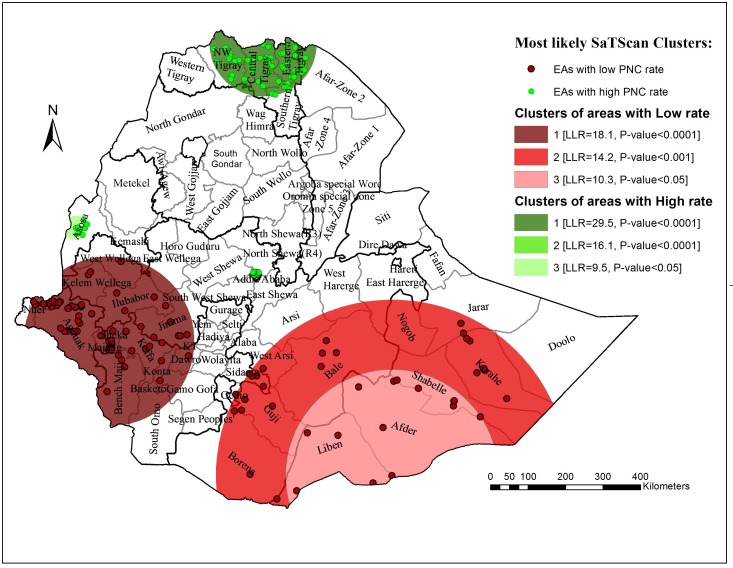

The SaTScan spatial analysis detected a total of three statistically significant SaTScan cluster areas with low PNC usage. The most likely primary SaTScan cluster of areas with low PNC was detected in southeast Ethiopia (log likelihood ratio (LLR)=20.72, p<0.0001), and secondary cluster in east Ethiopia (LLR=19.36, p<0.0001). The third most likely SaTScan cluster (LLR=10.91, p=0.048) was detected in the northern part of Ethiopia (table 2, figure 2). The highest cluster of PNC usage was observed in Tigray region (figure 3).

Table 2.

The most likely SaTScan clusters of areas with low prevalence of postnatal care among women in Ethiopia, 2016

| Cluster | Region (zones) | Clusters (n) | Radius (km) | LLR | P value |

| 1 | Oromiya Region (Kelem Wollega, West Wolega, East Wollega, Kemash and Jimma), Gambella Region (Nuer and Agnuak) and SNNPR Region (Sheka, Majang, Keffa, Benchi Maji, Konta, Dawro, South Omo and Basketo Gamo goffa) | 73 | 225.2 | 18.07 | <0.001 |

| 2 | Oromiya region (Borena, Guji, Bale, West Arsi, West and East Hararge), Ethio-Somali Region (Doolo, Korahe, Jarar and Nogab) and SNNPR (Gedio and Sidama) | 39 | 467.6 | 14.19 | <0.001 |

| 3 | Oromiya Region (Bale and Guji), and Ethio-Somali Region (Liben, Afder and Shabelle) | 14 | 282.34 | 10.28 | 0.024 |

LLR, log likelihood ratio; SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region.

Figure 2.

Spatial clustering of women’s PNC in Ethiopia, 2016. EAs, Enumeration Areas; LLR, log likelihood ratio; PNC, postnatal care.

Figure 3.

Percentage distribution of women’s postnatal care by region in Ethiopia, 2016.

Factors associated with PNC usage

Demographic and socioeconomic variables were selected using enter methods at 0.25 significance level. In the final model, maternal education, wealth index and ANC visits were identified as associated factors with women’s PNC usage after delivery.

Level of education showed a strong statistical association with PNC service usage. Mothers who had no education were about 45% times (AOR=0.55, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.84) less likely to use PNC service than educated (above secondary) women. Similarly, women belonging to the poorest wealth quintiles had 45% less chance of using PNC service (AOR=0.55, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.78) than the richest women.

The age of women was also an important predictor of PNC service usage. Mothers in the age group of 35–49 years were about 1.75 times (AOR: 1.75, 95% CI 1.01 to 3.04) more likely to use PNC service than women younger than 19 years. PNC service usage also increased with increasing ANC visits of mothers. Women who had one to three ANC visits (OR=2.37, 95% CI 1.71 to 3.29) were 2.37 times more likely to receive health checkups after delivery than those who had no visits. Moreover, mothers who had a fourth ANC visit were about threefold (AOR: 3.43, 95% CI 2.47 to 4.76) more likely to use PNC service than those who had not had any type of ANC visits (table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with PNC usage among women giving birth in the last 5 years preceding the survey in Ethiopia, 2016

| Variables | PNC use | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | ||

| Yes | No | ||||

| Maternal education | Above secondary | 45 | 270 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No education | 226 | 4133 | 0.39 (0.27 to 0.56) | 0.55 (0.37 to 0.84) | |

| Primary | 158 | 1784 | 0.57 (0.39 to 0.83) | 0.69 (0.46 to 1.01) | |

| Secondary | 67 | 510 | 0.81 (0.54 to 1.23) | 0.87 (0.57 to 1.315) | |

| Age (years) | 15–19 | 16 | 342 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 20–34 | 351 | 4690 | 1.47 (0.88 to 2.47) | 1.47 (0.87 to 2.48) | |

| 35–49 | 129 | 1665 | 1.46 (0.85 to 2.51) | 1.75 (1.01 to 3.04) | |

| Religion | Orthodox Christian | 246 | 2123 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Muslim | 179 | 3145 | 0.83 (0.63 to 1.11) | ||

| Protestant | 69 | 1269 | 0.78 (0.54 to 1.14) | ||

| Others* | 2 | 160 | 0.18 (0.04 to 0.75) | ||

| Residence | Urban | 160 | 1352 | 1.00 | |

| Rural | 336 | 5345 | 0.60 (0.47, 0. 76) | ||

| Wealth Index | Richest | 180 | 1461 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Poorest | 87 | 2341 | 0.39 (0.28 to 0.55) | 0.55 (0.39 to 0.78) | |

| Poorer | 74 | 1105 | 0.64 (0.45 to 0.89) | 0.75 (0.54 to 1.056) | |

| Middle | 75 | 953 | 0.77 (0.55 to 1.07) | 0.85 (0.61 to 1.19) | |

| Richer | 80 | 837 | 1.06 (0.78 to 1.45) | 0.94 (0.63 to 1.407) | |

| ANC visit | No antenatal care | 58 | 2423 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ANC one to three visits | 141 | 1951 | 2.58 (1.88 to 3.54) | 2.37 (1.71 to 3.29) | |

| ANC at four visits | 297 | 2323 | 4.09 (3.01 to 5.55) | 3.43 (2.47 to 4.76) | |

| Sex of child | Male | 233 | 3485 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 263 | 3212 | 1.20 (1.00 to 1.45) | ||

| Place of delivery | Health facility | 266 | 2433 | 1.00 | |

| Other than health facility | 230 | 4264 | 0.67 (0.54 to 0.82) | ||

*Catholic, traditional and other unclassified.

Bold face value indicates significant varaibles in mutivaraible logistic regresion at 0.05 level of significance or 95% confidence level.

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odds ratio; PNC, postnatal care.

Discussion

In Ethiopia, the prevalence of women’s PNC usage was found to be 6.9% with marked spatial heterogeneity. The spatial scan statistics detected a total of three statistically significant SaTScan clusters of areas with low prevalence of PNC.

The study showed that Ethiopia continued to have a low proportion of PNC usage. The finding was lower than the 2011 EDHS report9 13 which indicated that maternal and child health remained poor. This may be attributed to differences in the samples and could be an improvement in data quality to date. It was found to be below those of studies done in Amhara region, Ethiopia15 29 and southern Ethiopia.30 The difference might be due to the difference in study participants sociodemographic characteristics like residency. This study included rural areas in which having low health-seeking behaviour, accessibility of health institution and that might hinder usage of PNC. This low result may be attributed to the impact of programmatic problems on women making PNC visits and low exposure to the mass media. Compared with findings in low-income and middle-income countries, such as Kenya (47%),31 32 Nigeria (29%),33 Nepal (40.9%)12 and Tanzania (10.5%),34 PNC usage was low in Ethiopia. This could be due to differences in health service accessibility, study time and the quality of care across countries.

A clustered pattern of areas with low and high rates of the PNC was generally observed in Addis Ababa city and Tigray region, whereas low PNC rates were detected in eastern, southeastern and northern part of Ethiopia. This clustered pattern could be attributed to differences in health service accessibility and quality of healthcare. In addition, it could be the result of sociocultural differences during postnatal period activities. This finding is supported by the studies conducted in Ghana and India in which geographical variations have been observed.35 36

In the multilevel logistic regression, maternal age, educational status, household wealth quintile and ANC visits were identified as predictors of PNC. Women with no education were less likely to use PNC compared with women who had more than secondary school education. This finding is consistent with the studies conducted in Ethiopia13 15 30 37 38 and other low-income countries, such as Nigeria,39 Kenya,32 Nepal12 and India.36 This could be explained by the fact that education has a valuable input in enhancing female autonomy and helping them to develop greater confidence and capability to make decisions about their own health. Thus, literate women seek out higher quality health services and have a greater ability to use healthcare inputs that offer better health outcomes.

Similarly, women belonging to the poorest wealth quintile level were less likely to use PNC compared with those in the richest wealth quintile who attend at least one PNC visit. This study is similar to evidence from another study conducted in Ethiopia.13 Our finding is also in line with those of other studies: Pakistan,40 Nepal and Rwanda.12 41 Rich women may get more information regarding PNC from mass media and may have better healthcare access.

PNC usage was positively associated with ANC services. Women who had a history of ANC visits were more likely to receive PNC service than their counterparts. This finding is supported by the studies conducted in Nepal,12 India,36 Tanzania34 and Kenya.32 The possible reasons for the positive effects of ANC on PNC are that ANC offers women an entry point to the healthcare system as well as providing counselling and awareness above the benefits of PNC. Additionally, if the ANC experience was positive, women were more ready to make PNC visits. Furthermore, this could be due to variations in sociodemographic and cultural characteristics which may lead to seeking health service related to pregnancies.

In this study, we found that old age at delivery was positively associated with PNC use. Our finding contrasts with that of a study done in Rwanda.41 The main reason is the differences in culture. In Ethiopia, adult women are more involved in their own healthcare decision-making and enjoy better respect than younger women. This may reinforce the fact that women who are empowered to make healthcare choices based on previous experiences of any maternal healthcare services.

The main strength of this study was its use of a nationally representative community-based study with a large sample. The other strength was that we used a spatial and advanced statistical approach to accommodate the hierarchical nature of the data. However, this study is not free from limitations and should be mentioned. Due to the retrospective nature of the data and maternal verbal reports, recall bias might have been introduced. The other limitation was that DHS did not provide information about accessibility (ie, distance to a health facility) or the quality of healthcare providers which might influence the use of PNC among reproductive age women. Lastly, the geographical coordinates of EAs are displaced by up to 5 km to prevent identification of respondents or the community. This could affect the cluster effect in the spatial analysis. So, those should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

This study showed that PNC usage had variations in geographical areas of Ethiopia. Local clusters of areas with low prevalence of PNC were detected in Somali, Oromia, Gambella and SNNPR regions. Women with low educational status, older age, poorest wealth quantile and history of ANC visits were significantly associated with PNC usage. Hence, the Government of Ethiopia and other stakeholders could tailor effective maternal health programmes to mitigate the inequalities identified in this study. It is also good to promote health education and ANC visit with a continuum of care. Further research is recommended to investigate the reasons for regional disparities in the country.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Our sincere thanks go to MEASURE DHS Program and ICF International which granted us the permission to use DHS data. We also thank the University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Institute of Public Health for all support.

Footnotes

Contributors: TTG, YWD, ATA and DK conceptualised and designed the study. MMS, MFM, TTG, YWD, ATA and DK carried out the literature review, data extraction and analysis. MMS drafted the manuscript. KA, TA, AAA and MFM participate in data analysis and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All relevant data are available within the manuscript. However, the minimal data underlying all the findings in the manuscript will be available upon request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Map disclaimer: The depiction ofboundaries on the map(s) in this article do not imply the expression of anyopinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerningthe legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of itsauthorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, eitherexpress or implied.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality:1990 to 2015, Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA: The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carroli G, Rooney C, Villar J. How effective is antenatal care in preventing maternal mortality and serious morbidity? An overview of the evidence. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2001;15(Suppl 1):1–42. 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.0150s1001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kamau M, Donoghue D. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Global Action. 2015. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/7603Final

- 4. Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Success factors for women’s and children’s health: Ethiopia. 2015. http://www.who.int/pmnch/successfactors/en/

- 5. Health, E.F.M.o. HMIS indicator Definetions, Technical standards in area, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organazation. Post natal care of mother and newborn utilization guideline. Geneva/Swizerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organazation. Population Division Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group in Ethiopia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organazation. WHO Technical Consultation on Postpartum and Postnatal Care. Switzerland, Geneva, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF Macro. Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency and ICF Macro, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF Macro. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency and ICF Macro, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ethiopia Centeral Statstical Agency. Ethipiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khanal V, et al. . Factors associated with the utilisation of postnatal care services among the mothers of Nepal: analysis of Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tarekegn SM, Lieberman LS, Giedraitis V. Determinants of maternal health service utilization in Ethiopia: analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:161 10.1186/1471-2393-14-161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tefera B, Ayanos T, Tamiru B. Postnatal Care Service Utilization and Associated Factors among Mothers in Lemo Woreda, Ethiopia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miteku A, Zerfu M, Berihun A. Postnatal Care Service Utilization and Associated Factors among Women Who Gave Birth in the Last 12 Months prior to the Study in Debre Markos Town. Northwestern Ethiopia: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sinai S. Final draft, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koblinsky MA, Campbell O, Heichelheim J. Organizing delivery care: what works for safe motherhood? Bull World Health Organ 1999;77:399–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. . The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:968–74. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Central Statistical Agency (CSA). Population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at Wereda level from 2014 – 2017. Addis Ababa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey data or The Measure DHS Project. 2016. http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

- 21. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Rockville, Maryland, USA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anselin L, Getis A. Spatial statistical analysis and geographic information systems. Ann Reg Sci 1992;26:19–33. 10.1007/BF01581478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chaikaew N, Tripathi NK, Souris M. Exploring spatial patterns and hotspots of diarrhea in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Int J Health Geogr 2009;8:36 10.1186/1476-072X-8-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bernoulli. Discrete Poisson and Continuous Poisson Models: Kulldorff M. A spatial scan statistic. Communications in Statistics: Theory and Methods 1997;26:1481–96. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulldorff M and Information Management Services, Inc. SaTScanTM v8.0: Software for the spatial and space-time scan statistics. 2009. http://www.satscan.org/

- 27. Kulldorff M. SaTScanTM User Guide for version 9.4, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alemu K, Worku A, Berhane Y, et al. . Spatiotemporal clusters of malaria cases at village level, northwest Ethiopia. Malar J 2014;13:223 10.1186/1475-2875-13-223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Workineh YG, Hailu DA. Factors affecting utilization of postnatal care service in Jabitena district, Amhara region. Ethiopia Science Journal of Public Health 2014;2:169–76. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Regassa N. Antenatal and postnatal care service utilization in southern Ethiopia: a population-based study. Afr Health Sci 2011;11:390–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nancy N. Utilization of Post Natal Care Services in Kenya, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Akunga D, Menya D, Kabue M. Determinants of Postnatal Care Use in Kenya. African Population Studies 2014;28 10.11564/28-3-638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dahiru T, Oche OM. Determinants of antenatal care, institutional delivery and postnatal care services utilization in Nigeria Pan. African Medical Journal 2015;21:321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kanté AM, Chung CE, Larsen AM, et al. . Factors associated with compliance with the recommended frequency of postnatal care services in three rural districts of Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:341 10.1186/s12884-015-0769-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Asamoah BO, Agardh A, Cromley EK. Spatial analysis of skilled birth attendant utilization in Ghana. Glob J Health Sci 2014;6:117-27 10.5539/gjhs.v6n4p117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Singh PK, Kumar C, Rai RK, et al. . Factors associated with maternal healthcare services utilization in nine high focus states in India: a multilevel analysis based on 14 385 communities in 292 districts. Health Policy Plan 2014;29:542–59. 10.1093/heapol/czt039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hordofa MA, et al. . Postnatal Care Service Utilization and Associated Factors Among Women in Dembecha District, Northwest Ethiopia Science. Journal of Public Health 2015;3:686–92. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Worku AG, Yalew AW, Afework MF. Factors affecting utilization of skilled maternal care in Northwest Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2013;13:20 10.1186/1472-698X-13-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Babalola S, Fatusi A. Determinants of use of maternal health services in Nigeria--looking beyond individual and household factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:43 10.1186/1471-2393-9-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yunus A. Determinants of Postnatal Care Services Utilization in Pakistan- Insights from Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) 2006-07. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 2013;18:1440–7. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rwabufigiri BN, Mukamurigo J, Thomson DR, et al. . Factors associated with postnatal care utilisation in Rwanda: A secondary analysis of 2010 Demographic and Health Survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:122 10.1186/s12884-016-0913-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.