Abstract

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) prompted sweeping changes to Medicaid, including expanding insurance coverage to an estimated 12 million previously uninsured Americans, and imposing new parity requirements on benefits for behavioral health services, including substance use disorder treatment. Yet, limited evidence suggests that these changes have reduced the number of uninsured in substance use disorder treatment, or increased access to substance use disorder treatment overall. This study links data from a nationally-representative study of outpatient substance use disorder treatment programs and a unique national survey of state Medicaid programs to capture changes in insurance coverage among substance use disorder treatment patients after ACA implementation. Medicaid expansion was associated with a 15.7-point increase in the percentage of patients insured by Medicaid in substance use disorder treatment programs and a 13.7-point decrease in the percentage uninsured. Restrictions in state Medicaid benefits and utilization policies were associated with a decreased percentage of Medicaid patients in treatment. Moreover, Medicaid expansion was not associated with a change in the total number of clients served over the study period. Our findings highlight the important role Medicaid has played in increasing insurance coverage for substance use disorder treatment.

1. Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) leveraged the Medicaid program to improve access to insurance coverage for substance use disorder (SUD) treatment in the United States (Abraham et al., 2017; Friedmann, Andrews, & Humphreys, 2017). The ACA extended Medicaid eligibility to 12 million previously uninsured Americans, and required state Medicaid plans to cover SUD treatment, thus extending parity requirements established by the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act to apply to coverage for Medicaid enrollees newly-eligible for the program as a result of expansion, as well fee-for-service benefits when carved out of Medicaid managed care (Andrews et al., 2018).

From 2014 to 2017, Medicaid benefits for SUD treatment increased, while restrictions on use of SUD treatment dropped substantially (Andrews et al., 2018). As a result, Medicaid’s role in financing SUD treatment has greatly expanded (Abraham et al., 2017; Andrews et al., 2018; Friedmann, Andrews, & Humphreys, 2017; Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission, 2018). The program is projected to pay an estimated $12 billion annually by 2020, making it the largest funding source of SUD treatment services in the nation (Mark, Levit, Yee, & Chow, 2014).

1.1. Medicaid coverage among individuals with SUD

Although not all states adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, research suggests that it has resulted in improvements in SUD treatment coverage on a national scale. A recent study using data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) found that the percentage of Americans with a likely diagnosis of SUD who did not have insurance declined from 34% to 20% from 2012–13 to 2014–15, and that this increase in health insurance coverage occurred largely through Medicaid (Olfson, Wall, Barry, Mauro & Mojtabai, 2018). Individuals with SUD reporting Medicaid coverage increased from 30% to 60% during the same period. Another study using NSDUH data found a similar decline in the uninsured rate in Medicaid expansion states, along with a corresponding increase in Medicaid coverage, and no significant changes in rates of private insurance over a period from 2011–2012 to 2014 (Saloner, Bandara, Bachhuber, & Barry, 2017).

1.2. Changes in treatment admissions after Medicaid expansion

Less clear is the impact of these changes on the extent of insurance coverage among those who enter SUD treatment—particularly the four million Americans with SUD who became newly-eligible for Medicaid under the program’s expansion beginning in 2014. In a study drawing on Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) data from publicly-funded and licensed treatment programs in 25 states, MacLean and Saloner (2017) found that the percentage of treatment admissions with Medicaid as a payment source increased from 16% to 28% from 2010 and 2014 in states that expanded Medicaid. No changes were observed in states that did not. The study also found that treatment admissions financed through other public funds or paid for out-of-pocket declined significantly. Using the same data, Meinhofer and Witman (2018) found that, in states that expanded Medicaid, opioid use disorder treatment admissions covered by Medicaid increased 113% from 2007 to 2015. Little change in admissions was observed in states that did not expand Medicaid.

1.3. Medicaid benefits and restrictions on substance use disorder treatment

However, it remains unclear whether these early-implementation observations represent all states and reflect a longer national trend in the SUD treatment system. While prior work provides important insight into the potential impact of Medicaid expansion and insurance coverage within the SUD treatment system, these studies include a limited number of states and examine treatment admissions during a relatively early period after implementation of the Medicaid expansion.

Moreover, prior studies have not accounted for specific state Medicaid benefits for SUD treatment, which play an important role in SUD treatment programs’ willingness to serve the Medicaid population (Andrews, 2014; Andrews et al., 2018; Terry-McElrath, Chriqui, & McBride, 2011). States vary in their SUD treatment benefits, as well as use of restrictions on benefits across standard Medicaid plans, defined as states’ fee-for-service coverage as outlined in their state Medicaid plans. Variation across states, as well as changes in benefits and restrictions over time, are described in detail in two prior studies (Andrews et al., 2018; Grogan et al., 2016).

In 2017, 47% of SUD treatment services and medications were subject to prior authorization, 34% were subject to copayment, and 19% were subject to annual limits on service utilization, including quantity limits on medications for treatment of opioid use disorder. Such restrictions have been linked to reduced odds of participation in Medicaid among SUD treatment programs in prior research (Andrews et al., 2018). Given a substantial reduction in utilization controls that occurred during the same period, it remains unclear whether Medicaid expansion, benefit design and utilization controls, or both contributed to the observed increase in Medicaid-funded treatment admissions.

This study draws from a nationally-representative survey of outpatient SUD treatment programs and a unique national survey of state Medicaid agencies to address four major questions. First, did the percentage of SUD treatment patients covered by Medicaid change from 2013–14 to 2016–17—both in states that expanded Medicaid and states that did not? Second, did the percentage of SUD treatment patients who were uninsured change in states that did and did not expand Medicaid over the same period? Third, are state restrictions on Medicaid SUD treatment benefits utilization controls linked to the percentage of SUD treatment patients covered by Medicaid? And finally, are the expansion of Medicaid eligibility and SUD treatment benefits under the ACA related to an overall increase in treatment admissions between 2013–14 and 2016–17?

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

2.1.1. Treatment program survey.

This analysis draws on two data sources from the National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey (NDATSS). The first data source is a nationally-representative, longitudinal study of SUD treatment programs in the United States collected over seven waves beginning in 1988. This study uses data from waves collected in 2013–14 and 2016–17. The survey covers a broad range of topics related to SUD treatment access and quality. The first study wave of data used in the study occurred from November 2013 to May 2014, encompassing the period just before and immediately after implementation of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion in most states. The second wave of data used in the study was conducted from September 2016 to May 2017, approximately three years after the beginning of implementation of Medicaid expansion on January 1, 2014. The response rate was 85.5% in the 2013–14 wave and 86.5% in the 2016–17 wave.

To ensure our sample of SUD treatment programs was nationally representative in both sample periods, we employed a split panel design with replacement sampling to account for programs that exited the survey over time. Programs were selected for inclusion in the study based on a sampling frame that included all SUD treatment programs included in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Treatment Locator. We also developed survey weights to address possible nonresponse bias and ensure that the sample was nationally representative.

The Cornell Survey Research Institute collected the data via a 90-minute internet-based survey of program directors and clinical services supervisors in each program at two distinct time points. Potential survey respondents were mailed a letter prior to screening for inclusion in the study. The letter explained the study and informed providers that we would be phoning them to conduct an eligibility screening interview. This approach reduces the common-method variance in data analyses that stems from having a single survey respondent; allows tailoring of each survey to the respondent’s responsibilities; reduces individual respondent burden; and permits reliability checks by cross-checking supervisor and director responses. To maximize reliability and validity of the survey’s client and insurance enrollment and data, we sent program directors web-based worksheets that inform them of the requested data and enable them to consult financial and administrative records prior to administration of the survey. In addition, we performed reliability checks to identify inconsistent or infeasible responses and resolved such inconsistencies as needed.

The current analysis limits the sample to include only outpatient SUD treatment programs. One reason for this is Medicaid’s Institutions for Mental Disease (IMD) exclusion, a regulation that has largely prohibited Medicaid from reimbursing for SUD treatment in inpatient behavioral health treatment settings with 16 or more beds. Because of these limits on Medicaid reimbursement in residential and inpatient settings, we anticipated limited direct effects of changes in Medicaid eligibility and benefits in these settings. With this restriction, our final analytic sample included 524 outpatient SUD treatment programs in 2013–14, and 500 programs in 2016–17; 436 of these programs participated in the survey in both NDATSS waves.

2.1.2. State Medicaid agency survey.

Our second data source was a 15-minute, internet-based survey of Medicaid agencies in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. These data were specifically collected to complement our program-level data as part of the NDATSS study. The NDATSS study team contracted with the University of Chicago Survey Lab to assist with collection of the data. The first wave of the Medicaid agency survey was conducted from November 2013 to December 2014, and the second wave was conducted from May 2017 to December 2017. The response rate in each wave was 92%. To reduce respondent burden, the first wave was prefilled to the greatest extent possible using publicly-available data on Medicaid benefits in each state. Survey respondents were asked to review the prefilled data and make revisions as needed. Data on benefits and utilization controls for SUD treatment medications, including methadone, buprenorphine, and oral and injectable naltrexone, were taken from data collected by American Society for Addiction Medicine (ASAM) through a survey and review of state Medicaid drug formularies in 2013–14. These data were not included in the survey for review by state Medicaid representatives. In the 2017 wave, ASAM data were prefilled in the survey and states were asked to update any changes in benefits or restrictions. A more detailed description of the Medicaid agency survey methods and findings is available in previously-published research (Andrews et al., 2018; Grogan et al., 2016).

In the second wave of this state Medicaid agency survey, responses from the prior wave pre-populated the survey. Respondents were asked to review and make modifications as needed. For states that did not complete the survey—four in each study wave—a research team member added data using information from a review of publicly-available resources on state Medicaid coverage for SUD treatment. Medication data were collected through review of published state drug formularies. Only one state declined to participate in both waves of the survey.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Independent variables. The study’s independent variable was a measure of state Medicaid expansion.

To calculate the study’s primary independent variable, we interacted state Medicaid expansion status by study wave, with 2013–14 representing the pre-implementation period and the 2015–16 wave representing the post-implementation period. Two states (Louisiana and Montana) that expanded Medicaid in the year prior to the conclusion of our study period were not designated as Medicaid expansion states because there was inadequate time to assess potential changes in their SUD treatment programs resulting from the program’s expansion.

Secondary independent variables measured state Medicaid SUD treatment benefits and restrictions. We included dichotomous variables to measure state Medicaid coverage for each of the following services and medications: outpatient treatment (including individual and group), intensive outpatient treatment, recovery support services, detoxification, methadone maintenance, injectable naltrexone, and oral naltrexone. Because all 50 states and the District of Columbia covered buprenorphine during both survey ways, we did not include it in the model. None of the correlations among the above mentioned services and medications were correlated at a level above r=0.35. Second, we created measures of the percentage of covered services and medications subject to copays, preauthorization, and annual service limits. Each of the three measures (restrictions on copays, preauthorization, annual service limits) were derived by dividing the total number of services and medications to which the restriction was applied by the total number of services and medications covered by Medicaid in the state. Buprenorphine was included among the services and medications used to compute these three measures.

2.2.2. Dependent variables.

To assess potential changes in treatment admissions and insurance coverage, the study included three dependent variables, each of which were taken from the survey of SUD treatment programs: (1) the percentage of outpatient treatment patients who were covered by Medicaid in the most recent fiscal year; (2) the percentage of outpatient treatment patients who lacked insurance coverage for SUD treatment in the most recent fiscal year; and (3) the total number of outpatient clients served in the most recent fiscal year. In the first wave, all participating treatment programs reported on fiscal years ending in either 2012 or 2013. In the second wave, treatment programs reported on fiscal years ending in 2015 or 2016.

2.2.3. Control variables.

Control variables included ownership type (public, private non-profit, private for-profit), whether the program was an opioid treatment program, program size (employs 40 or more staff), accreditation (Joint Commission or Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities), average caseload size (measured in four categories: 0–10, 11–25, 26–40, >40 patients), staff professionalism (more than 75 percent of staff hold a professional degree), and whether a program received federal block grant funds. We also included measures of the percentage of African American and Latino patients, use of electronic health records, in-house billing capacity, and whether a treatment program was located in a rural county. Each of these variables, which were drawn from the treatment program survey, were selected for inclusion based on prior research using NDATSS data in which they have been important predictors of outcomes related to treatment access and utilization (Alexander, Nahra, & Wheeler, 2003; Alexander, Pollack, Nahra, Wells, & Lemak, 2007; Friedmann, Lemon, Stein, & D’Aunno, 2003; Nahra, Alexander, & Pollack, 2009).

2.3. Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics for each study variable in the first (2013–14) and second (2016–17) waves. We also conducted a difference-in-difference analysis to compare changes in each of the three study outcomes in states that expanded Medicaid and states that did not before and after the expansion occurred. We used a censored regression specification to account for left- and right-censoring of potential values for dependent variables at zero and 100%. State-level random effects were included to account for unmeasured differences between states. Comparing states that expanded Medicaid with those states that did not allowed us to account for concurrent changes in health policy that may have also affected access to health insurance coverage for SUD treatment during the study period. We also conducted a secondary analysis to assess whether state restrictions on Medicaid benefits and utilization were associated with study outcomes. To do so, we included measures of state Medicaid SUD treatment benefits and restrictions, which are described in more detail in the section above. Difference-in-difference analyses were not conducted for these secondary variables. All control variables described above were also included in each model.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and bivariate statistics

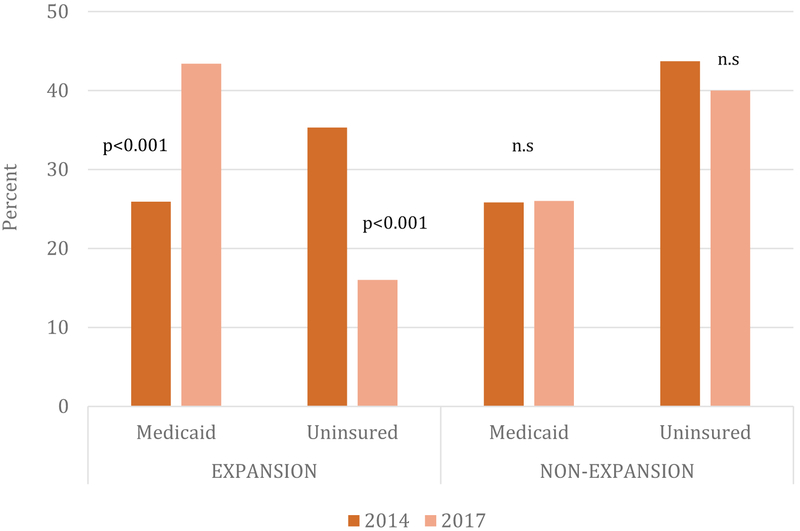

Significant changes in outpatient treatment admissions and insurance coverage occurred across all states over this time period (see Table 1). The proportion of patients insured by Medicaid increased from 26% to 38% (p<0.001), and the proportion of patients with no insurance dropped nearly in half over the three-year study period from 38% to 23% (p<0.001). The study findings indicate important differences in insurance coverage among states that did and did not expand Medicaid (see Figure 1). In states that expanded Medicaid, the mean percentage of patients with Medicaid per outpatient treatment program increased from 25.9% (95% CI: 21.0, 30.8) to 43.4% (95% CI: 37.6, 49.3). We observed a nearly identical offsetting change in the percentage of patients who were uninsured, which decreased from 35.3% (95% CI: 30.4, 40.3) to 16.0% (95% CI: 13.3, 18.6). We observed no significant changes in coverage among outpatient SUD treatment patients in non-expansion states during the study period. Total annual outpatient treatment admissions also increased significantly during the study period: from an average of 425 admissions per program in 2014 to an average of 607 admissions per program in 2017 (p<0.05).

TABLE 1:

| Medicaid Benefits | 2014 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|

| Covers outpt. treatment | 97.11 | 96.67 |

| Covers intensive outpatient | 81.35 | 81.67 |

| Covers recovery services* | 39.92 | 46.41 |

| Covers detoxification* | 91.64 | 96.68 |

| Covers methadone*** | 77.43 | 89.71 |

| Covers buprenorphine | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Covers inj. naltrexone | 90.47 | 93.78 |

| Covers oral naltrexone*** | 67.82 | 84.49 |

| % services w/ copays*** | 20.76 | 26.85 |

| % services req preauth*** | 47.84 | 38.47 |

| % of services w/ limits*** | 35.76 | 22.06 |

| Control Variables | ||

| Private non-profit* | 56.00 | 48.74 |

| Publicly-owned | 9.84 | 12.48 |

| Private for-profit* | 26.85 | 32.31 |

| Opioid treatment program | 11.67 | 11.31 |

| Caseload (categories) | 2.87 | 2.97 |

| 75%+ staff professional | 70.70 | 75.10 |

| Accredited | 44.00 | 47.23 |

| % patients African American | 18.43 | 20.70 |

| % patients Latino | 13.83 | 13.97 |

| Elec. health records** | 58.10 | 67.73 |

| In-house billing capacity | 70.61 | 79.04 |

| Block grant recipient | 49.50 | 46.94 |

| % patients Medicaid insured*** | 25.86 | 37.63 |

| % patients uninsured*** | 38.47 | 23.24 |

| Employs 40+ staff* | 7.89 | 12.63 |

| Rural county | 47.27 | 49.12 |

Note. Authors’ analysis of National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey data. Data include all outpatient programs that participated in the study in waves 2014 and 2017 (n=585).

All percentages are weighted

indicates p < 0.05;

indicates p < 0.01;

indicates p < 0.001

FIGURE 1.

Percent of Past-Year Treatment Patients Covered by Medicaid or Uninsured, by Year and Medicaid Expansion Status

Note: Authors’ analysis of National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey data. Data include all outpatient additional treatment programs that participated in the study in waves 2013–14 and 2016–17 (n=585).

From 2014 to 2017, the proportion of SUD treatment programs residing in states that covered recovery support services (from 39.9% to 46.4%, p=0.04), detoxification (from 91.6% to 96.7%, p=0.03), methadone (from 77.4% to 89.7%, p<0.001), and oral naltrexone (from 39.9% to 46.4%, p<0.001) increased significantly. The mean percentage of services and medications requiring preauthorization (from 47.8% to 38.5%, p<0.001) and annual service limits (from 35.8% to 22.1%, p<0.001) to which treatment programs were subject declined from 2014 and 2017. In contrast, the mean percent of services and medications requiring copays to which treatment programs were subject (from 20.8% to 26.9%, p<0.001) increased during the same period.

We also observed continued trends toward greater commercialization and increased technological infrastructure within the outpatient SUD treatment sector. As Table 1 shows, private for-profit treatment programs grew from 27% to 32% (p=0.02), whereas the proportion of private non-profit treatment programs decreased significantly from 56% to 49% during the same time period (p=0.02). Use of electronic health records increased from 58% to 68% (p<0.01), and capacity to bill insurance increased from 71% to 79% (p=0.02). Large programs employing 40 or more staff increased their market share from 8% to 13% (p=0.02).

3.2. Difference-in-difference model results

Multivariate difference-in-difference analyses yielded similar findings (Table 2). Treatment programs in states that expanded Medicaid reported a higher proportion of Medicaid patients before the expansion occurred (95% β: 12.1, CI: 1.1, 23.1, p=0.03). Expansion was associated with a 15.7 percentage-point increase in Medicaid-insured patients within outpatient treatment programs (95% CI: 4.6, 28.4, p=0.01). There was no significant time trend in non-expansion states.

TABLE 2:

Results of Random Effects Censored Regression Models Predicting the Percent Patients Covered by Medicaid of Uninsureda

| MEDICAIDb | UNINSUREDc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βd | Conf Intrvl | βd | Conf Intrvl | |||

| Medicaid Benefitse | ||||||

| Covers outpt. treatment | −12.19 | −43.28 | 18.90 | |||

| Covers intensive outpatient | *15.19 | 2.91 | 27.46 | |||

| Covers recovery services | −7.51 | −25.45 | 10.43 | |||

| Covers detoxification | 0.77 | −9.42 | 10.95 | |||

| Covers methadone | *13.00 | 0.66 | 25.34 | |||

| Covers inj. naltrexone | *17.47 | 3.19 | 31.74 | |||

| Covers oral naltrexone | -1.00 | −13.21 | 11.21 | |||

| % services w/ copays | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.22 | |||

| % services req preauth | −0.01 | −0.16 | 0.13 | |||

| % of services w/ limits | *−0.21 | −0.38 | −0.04 | |||

| Difference-in-Difference | ||||||

| Medicaid Expansion state | *12.09 | 1.10 | 23.08 | −6.78 | −14.23 | 0.70 |

| Year [2014 referent] | −4.24 | −14.99 | 6.50 | −6.70 | −13.96 | 0.58 |

| Year*Expansion interact. | **15.69 | 3.68 | 27.70 | **−13.70 | −22.65 | −4.75 |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Private non-profit | ***14.60 | 7.81 | 21.40 | 1.81 | −3.65 | 7.27 |

| Publicly-owned | 6.70 | −2.77 | 16.18 | 4.19 | −3.40 | 11.78 |

| Opioid treatment program | 5.84 | −0.23 | 11.91 | 0.46 | −4.39 | 5.31 |

| Caseload (categories) | 2.17 | −0.92 | 5.27 | **3.54 | 1.14 | 5.93 |

| 75%+ staff professional | −1.92 | −7.54 | 3.70 | 3.41 | −1.10 | 7.91 |

| Accredited | *6.38 | 0.23 | 12.53 | 3.20 | −1.69 | 8.08 |

| % patients Afr. American | ***0.31 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.16 |

| % patients Latino | *0.19 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.16 |

| Elec. health records | 0.68 | −5.07 | 6.43 | −1.37 | −5.94 | 3.20 |

| In-house billing | ***16.87 | 9.55 | 24.20 | 0.57 | −5.06 | 6.21 |

| Block grant recipient | −2.78 | −8.59 | 3.02 | ***12.01 | 7.35 | 16.67 |

| Employs 40+ staff | −3.43 | −12.41 | 5.54 | −6.17 | −13.45 | 1.11 |

| Located in rural county | ***14.01 | 7.88 | 20.14 | 4.33 | −0.50 | 9.15 |

Notes. Authors’ analysis of National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey data. Data include all outpatient programs that participated in the study in waves 2014 and 2017 (n=436);

indicates p < 0.05;

indicates p < 0.01;

indicates p < 0.001;

Outcome variable is the percent of outpatient treatment program patients covered by Medicaid in the most recent completed fiscal year;

Outcome variable is the percent of outpatient treatment program patients who were uninsured in the most recent completed fiscal year;

β coefficient is the average magnitude of change in the percentage of Medicaid patients served by substance use disorder treatment programs associated with each model variable, accounting for unobserved within-state homogeneity;

Measures of the percentage of covered services and medications subject to copays, preauthorization, and annual service limits were derived by dividing the total number of services and medications to which the restriction was applied by the total number of services and medications covered by Medicaid in the state. Buprenorphine was included among the services and medications used to compute these three measures.

Controlling for Medicaid expansion status, state policies regarding Medicaid’s SUD treatment benefit coverage were also positively associated with the percentage of treatment admissions with Medicaid coverage. Accounting for Medicaid expansion status, coverage for several services and medications was associated with a greater percentage of Medicaid-insured patients. Medicaid coverage for intensive outpatient treatment (β: 15.2, 95% CI: 2.9, 27.5, p=0.02), methadone (β: 13.0, 95% CI: 0.7, 25.3, p=0.04), and injectable naltrexone (β: 17.5, 95% CI: 3.2, 31.7, p=0.2) were all positively associated with the percentage of patients covered by Medicaid.

Conversely, the percentage of annual service limits imposed on SUD treatment services and medications was negatively associated with the proportion of Medicaid-insured patients served (β: 0.02, 95% CI: −4.3, −0.1). Medicaid expansion was also associated with a significant decrease in the percentage of clients who were uninsured. Medicaid expansion was associated with a 13.7 percentage-point decrease in uninsured patients (95% CI: −22.6, −4.7, p=0.004). However, expansion did not appear to be associated with an increase in the total number of patients served (Table 3).

TABLE 3:

Results of Random Effects Linear Regression Model Predicting the Total Number of Outpatient Substance use disorder Treatment Patients in the Most Recent Completed Fiscal Yeara

| βb | Conf Intrvl | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference-in-Difference | |||

| Medicaid Expansion state | 43.75 | −114.33 | 201.84 |

| Year (2014 referent) | 7.39 | −172.68 | 187.47 |

| Year*Expansion interact. | −42.50 | −265.18 | 180.18 |

| Control Variables | 100.05 | −36.67 | 236.78 |

| Private non-profit | 54.30 | −138.39 | 246.99 |

| Publicly-owned | 4.52 | −119.51 | 128.55 |

| Opioid treatment program | 97.89 | 36.56 | 159.23 |

| Caseload (categories) | **−114.28 | −232.38 | 3.82 |

| HighPropDegree | 30.88 | −92.45 | 154.21 |

| Accredited | −1.39 | −3.77 | 1.00 |

| % patients Afr. American | −1.47 | −4.41 | 1.47 |

| % patients Latino | −77.92 | −195.65 | 39.80 |

| Elec. health records | *165.41 | 23.14 | 307.67 |

| In-house billing capacity | *141.2S | 23.77 | 258.72 |

| Block grant recipient | ***674.61 | 486.42 | 862.80 |

| Employs 40+ staff | 49.23 | −70.80 | 169.25 |

| Located in rural county | 43.75 | −114.33 | 201.84 |

Notes. Authors’ analysis of National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey data. Data include all outpatient programs that participated in the study in waves 2014 and 2017 (n=436);

indicates p < 0.05;

indicates p < 0.01;

indicates p < 0.001;

β coefficient is the average magnitude of change in the total number of past-year substance use disorder treatment admissions associated with each model variable, accounting for unobserved within-state homogeneity.

4. Discussion

The proportion of uninsured outpatient SUD treatment clients declined sharply over the study period, but only in states that embraced Medicaid expansion. This finding suggests that the early impact of Medicaid expansion observed in prior studies has continued to endure, and is not explained solely by the concurrent improvements in Medicaid benefits for SUD treatment that were also promoted by the ACA (Maclean & Saloner, 2017; Olfson, Wall, Barry, Mauro, & Mojtabai, 2018).

However, the overall number of clients served by specialty outpatient SUD treatment programs did not increase during the study period. Like other studies (Maclean & Saloner, 2017; Olfson, Wall, Barry, Mauro, & Mojtabai, 2018), we found little evidence that treatment programs expanded capacity in response to Medicaid funding. At least in the short-term, Medicaid expansion’s most prominent impact has been as a financial shift within the sector, rather than an expansion in the capacity of outpatient SUD treatment programs to serve more patients.

These data do not address why treatment programs appear slow to expand in the face of both increased Medicaid resources and a burgeoning increase in treatment demand occasioned by the opioid epidemic. It is possible that treatment programs did not expand capacity in response to Medicaid expansion because health insurance coverage had not been a barrier to treatment for individuals newly enrolled in Medicaid.

However, given prior research indicating that lack of health insurance is often a major deterrent to SUD treatment access among low-income individuals (e.g., Appel, Ellison, Jansky, & Oldak, 2004; Mojtabai, Chen, Kaufmann, & Crum, 2014; Priester et al., 2016), it is likely that other dynamics may be at work. For example, policy uncertainty over both Medicaid expansion and the ACA’s general political fate may have deterred programs from making major investments, particularly in outreach to the newly-insured population (Grogan et al., 2016). Even under a favorable policy environment, it is rare for non-profit providers to expand capacity immediately. Capital and personnel investments require non-profits to first use increased revenues to build up reserves over a period of time. Even with increased Medicaid resources, outpatient SUD treatment programs may still lack the resources necessary to expand, particularly given that the other sources of SUD treatment funding, including the federal block grant, have generally not increased in recent years. Treatment programs may also be using new Medicaid revenue to improve the quality or breadth of SUD treatment services.

Increased potential competition from primary care providers and other health care providers outside the traditional specialty SUD treatment sector may also have played a role in limiting expansion of treatment capacity. For example, the introduction of buprenorphine in 2002 enabled physicians who obtained a Drug Enforcement Administration waiver to prescribe the drug to treat opioid use disorder in primary care settings. In addition, the recent increase in telehealth technology has enabled health care providers to deliver SUD treatment in new and geographically remote locations.

Adding to the current literature (Andrews, 2014; Andrews et al., 2018; Terry-McElrath, Chriqui, & McBride, 2011), our study also suggests that outpatient treatment programs in states that covered intensive outpatient treatment, as well as the full array of opioid use disorder treatment medications reported a greater percentage of Medicaid clients than treatment programs in states that provided more restrictive benefits.

Our study findings also suggest that the average proportion of services and medications subject to prior authorizations and annual limits to which treatment programs in our study were subject declined substantially. Given that our study findings also indicate that annual limits are inversely related to the proportion of Medicaid patients served, the decline in use of annual limits may have a positive influence on Medicaid participation. Treatment programs in states that imposed fewer quantity limits on the services and medications they covered reported serving a larger proportion of Medicaid patients on average.

This study is the first to assess the relationship between benefits restrictiveness and the extent of programs’ involvement in the Medicaid program, as prior research focused solely on whether programs accepted Medicaid as a form of insurance. However, further research is needed to determine whether this relationship between Medicaid benefits design and treatment programs’ willingness and ability to serve the Medicaid population is causal.

4.1. Limitations

Our findings must be interpreted in light of several study limitations. SUD treatment program study data are based on survey responses provided by treatment programs’ directors and clinical supervisors, and are susceptible to reporting bias. Moreover, treatment programs reported aggregated data on patient demographics and service receipt. Consequently, it is not possible to account for repeat treatment admissions, or changes in insurance status during the fiscal year. Moreover, the timeframe of data collection during the first wave encompassed a period of several months immediately after the implementation of Medicaid expansion on January 1, 2014. Thus, it is possible that our study findings may not fully and accurately reflect the pre-expansion period. However, our estimates of insurance coverage both before and after the implementation of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion are similar to those of MacLean and Saloner, who drew from national treatment admissions data to derive their estimates (Saloner & Maclean, 2017).

Additionally, we are unable to identify potential time trends one might potentially explore using data sources collected on a quarterly or annual basis. We are thus limited in our ability to examine the effects of early partial Medicaid expansions, or to assess whether the parallel trend assumption—an important prerequisite for use of the difference-in-difference model—has been met. However, prior studies that have tracked changes in SUD treatment admissions and payment prior to implementation of the ACA show strong evidence of parallelism prior to implementation of key provisions of the ACA in 2014, including Medicaid expansion and application of federal parity guidelines and essential health benefits to coverage for the expansion population (Maclean & Saloner, 2017; Saloner, Bandara, Bachhuber, & Barry, 2017).

Our data on state Medicaid benefits and utilization controls rely upon information specified in state Medicaid plans submitted to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, other publicly-available records, and review of the accuracy of these data by appropriate staff in each state’s Medicaid office. Although this two-pronged approach was designed to minimize data error, information provided through either the state plan amendments or from Medicaid staff could be inaccurate.

Our measures of state Medicaid benefits may not accurately reflect the benefits some enrollees in Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) may receive. While all MCOs must cover a minimum set of services defined by states, they often have some discretion with regard to use of utilization controls. Because our data capture minimum benefit policy restrictions imposed by the states, but do not capture within-state variation due to the possibility of more restrictive MCO policies, we might underestimate the impact of restrictive policies on Medicaid benefit coverage within treatment programs (Grogan et al., 2016).

4.2. Conclusion

Taken as a whole, the findings of this study suggest the ACA has played an important role in reducing the number of uninsured patients and increasing Medicaid covered patients receiving care in the specialty SUD treatment sector. This shift should benefit patients and communities by reducing the financial barriers to SUD treatment services. However, the ACA has not yet resulted in an increased number of clients in specialty outpatient SUD treatment, which is troubling in light of increased demand for treatment driven by the opioid epidemic. Future work is necessary to examine whether the reduction in the uninsured and accompanying increase in patients covered by Medicaid will improve the financial position of SUD treatment organizations, and lead to the investments necessary to expand treatment capacity.

Highlights: Medicaid Coverage in Addiction Treatment After the Affordable Care Act.

Medicaid expansion was associated with a 15.7-point increase in the percentage of Medicaid.

Expansion was also associated with 13.7-point decrease in the percentage uninsured.

Medicaid benefits restrictions were linked to fewer Medicaid patients in treatment.

Medicaid expansion did not increase the total number of clients served over the study period.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abraham AJ, Andrews CM, Grogan CM, D’Aunno T, Humphreys KN, Pollack HA & Friedmann. (2017). The Affordable Care Act transformation of substance use disorder treatment. American Journal of Public Health, 107(1), 31–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA, Nahra TA, & Wheeler JC (2003). Managed care and access to substance abuse treatment services. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 30, (2), 161–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA, Pollack H, Nahra T, Wells R, & Lemak CH (2007). Case management and client access to health and social services in outpatient substance abuse treatment. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 34(3), 221–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews CM (2014). The Relationship of state Medicaid coverage to Medicaid acceptance among substance abuse providers in the United States. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 41(4), 460–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews CM, Grogan CM, Smith BT, Abraham AJ, Pollack HA, Humphreys KN, Westlake MA, & Friedmann PD (2018). Increase in Medicaid benefits for substance use disorder treatment after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Health Affairs, 37(8), 1216–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews CM, Grogan CM, Westlake MA, Abraham AJ, Pollack HA, D’Aunno TA, & Friedmann. (2018). Do benefits restrictions limit Medicaid acceptance in substance use disorder treatment? Results from a national study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 87, 50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel PW, Ellison AA, Jansky HK, & Oldak R (2004). Barriers to enrollment in drug abuse treatment and suggestions for reducing them: opinions of drug injecting street outreach clients and other system stakeholders. The American journal of drug and Alcohol Abuse, 30(1), 129–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Andrews CM, Humphreys K. (2017). How ACA repeal would worsen the opioid epidemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 376(10), e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Lemon SC, Stein MD, & D’Aunno TA (2003). Accessibility of substance use disorder treatment: Results from a national survey of outpatient substance abuse treatment organizations. Health Services Research. 38(3), 887–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan CM, Andrews CM, Abraham AJ, Pollack HA, Humphreys KN, Smith B, & Friedmann PD (2016). Survey highlights differences in Medicaid coverage for substance use treatment and opioid use disorder medications. Health Affairs, 35(12), 2289–2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean JC & Saloner B (2017). The effect of public insurance expansions on substance use disorder treatment: Evidence from the affordable care act. Discussion Papers, No. 10745: National Bureau of Economic Research. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Levit KR, Yee T, Chow CM. (YEAR). Spending on mental and substance use disorders projected to grow more slowly than all health spending through 2020. Health Affairs, 33(8), 1407–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission. (2018). Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP. Retrieved from: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/June-2018-Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf

- Meinhofer A & Witman AE (2018). The Role of health insurance on treatment for opioid use disorders: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion. Journal of Health Economics, 60, 177–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Chen LY, Kaufmann CN, & Crum RM (2014). Comparing barriers to mental health treatment and substance use disorder treatment among individuals with comorbid major depression and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(2), 268–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahra TA, Alexander JA, & Pollack H (2009). Influence of ownership on access in outpatient substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36(4), 355–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Wall M, Barry CL, Mauro C, & Mojtabai R (2018). Impact of Medicaid expansion on coverage and treatment of low income adults with substance use disorders. Health Affairs, 37(8), 1208–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priester MA, Browne T, Iachini A, Clone S, DeHart D, & Seay KD (2016). Treatment access barriers and disparities among individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: an integrative literature review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 61, 47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B, Bandara S, Bachhuber M, & Barry CL (2017). Insurance coverage and treatment use under the Affordable Care Act among adults with mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services, 68(6), 542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry-McElrath YM, Chriqui JF, & McBride DC (2011). Factors related to Medicaid payment acceptance at outpatient substance abuse treatment programs. Health services research, 46(2), 632–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uberoi N, Finegold K, Gee E. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010–2016. (2016). Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation: Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]