Abstract

Long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) are persistent modifications of synaptic efficacy that may contribute to information storage in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Persistently enhanced phosphorylation has been implicated in the maintenance phase of LTP. This hypothesis is supported by our previous observation that protein kinase Mζ (PKMζ), the constitutively active catalytic fragment of a single protein kinase C isoform (PKCζ), increases in LTP maintenance. In contrast, dephosphorylation may be important in LTD maintenance, because phosphatase inhibitors reverse established LTD, in addition to blocking its induction. Because phosphorylation is determined by a balance of phosphatases and kinases, both increases in phosphatase activity and decreases in kinase activity could contribute to LTD. We now report that the reduction of protein kinase activity by H7, as well as selective inhibition of PKC by chelerythrine, mimics and occludes the maintenance phase of homosynaptic LTD in rat hippocampal slices. Conversely, saturated LTD occludes the synaptic depression caused by chelerythrine. Biochemical analysis demonstrates a decrease of PKMζ, as well as PKCs γ and ε, in LTD maintenance and a concomitant loss of constitutive PKC activity. LTD and the downregulation of PKMζ are prevented by NMDA receptor antagonists and Ca2+-dependent protease inhibitors. Both LTD and the downregulation of PKMζ are reversible by high-frequency afferent stimulation. Our findings indicate that the molecular mechanisms of LTP and LTD maintenance are inversely related through the bidirectional regulation of PKC.

Keywords: long-term potentiation, long-term depression, phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, protein kinase C zeta isozyme, PKMζ, learning and memory

Persistently increased protein kinase activity is a leading hypothesis for the mechanism of long-term potentiation (LTP) maintenance (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Schwartz, 1993; Malenka, 1994). Support for this hypothesis comes from a combination of biochemical and physiological studies that have implicated both protein kinase C (PKC) (Hu et al., 1987; Malinow et al., 1988, 1989; Colley et al., 1990; Klann et al., 1991, 1993; Wang and Feng, 1992; Sacktor et al., 1993; Hvalby et al., 1994; Osten et al., 1996) and the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaM-kinase II) (Malenka et al., 1989; Malinow et al., 1989; Silva et al., 1992; Fukanaga et al., 1993; Lledo et al., 1995).

PKC consists of a family of isoforms that has been classified into three second messenger-dependent groups: conventional, new, and atypical (Nishizuka, 1995). PKC can also be converted into a second messenger-independent, constitutively active form, protein kinase M (PKM), by limited proteolysis at the hinge region of the enzyme, separating regulatory from catalytic domain (Takai et al., 1977). In the brain, only PKM of the atypical isozyme PKCζ has been observed consistently (Sacktor et al., 1993). During LTP in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, the isoforms are activated in temporally distinct phases (Sacktor et al., 1993): In the induction phase of LTP, the α, βI, βII, δ, η, and ζ isoforms translocate from the inactive state in cytosol to the active state on membrane. The translocation of PKC isoforms, however, is not sustained. In contrast, an increase in PKMζ persists in the maintenance phase of LTP. This increase lasts at least 2 hr in the hippocampal slice and linearly correlates with the degree of EPSP potentiation (Osten et al., 1996).

PKC has also been implicated in the maintenance of LTP by physiological studies with protein kinase inhibitors. These studies, however, have been limited both by the lack of selective inhibitors and by differences in experimental observations. H7, for example, a nonspecific inhibitor of protein kinases, reverses LTP maintenance (Malinow et al., 1988; Colley et al., 1990), but also depresses baseline synaptic responses (Muller et al., 1990; Leahy and Vallano, 1991; Waxham et al., 1993), confounding the effect of H7 on LTP. An overall assumption in the interpretation of these experiments, however, is that the mechanisms maintaining potentiated synaptic transmission are pharmacologically distinguishable from those maintaining baseline synaptic transmission. This need not be the case. Indeed, the observations that synaptic responses can be persistently depressed by low-frequency afferent stimulation [long-term depression (LTD)] (Dudek and Bear, 1992; Mulkey and Malenka, 1992) suggest alternative viewpoints. There may be, for instance, mechanisms maintaining the efficacy of synaptic transmission that are increased in LTP and decreased in LTD .

Supporting this notion of a bidirectional mechanism for synaptic plasticity, a decrease in phosphorylation has been implicated in LTD (Mulkey et al., 1993, 1994). Phosphatase inhibitors not only block LTD formation, but reverse established depression (Mulkey et al., 1993). The activation of calcineurin, a Ca2+-dependent phosphatase, has been directly implicated in LTD induction (Mulkey et al., 1994). The mechanism for dephosphorylation in LTD maintenance, however, may involve either persistent increases in phosphatases or decreases in kinases, because a reduction in phosphorylation may result from a shift in the balance between these two activities. To examine the regulation of phosphorylation during the maintenance of bidirectional synaptic plasticity, we first investigated the interactions among LTD, LTP, and the pharmacological reduction of protein kinase activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Electrophysiology. Hippocampal slices (450 μm) were prepared with a McIlwain tissue slicer from Sprague Dawley rats, aged 16–21 d. Recordings were performed in an interface chamber infused with saline solution containing (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 11 glucose, 1.2 MgCl2, and 1.7 CaCl2, pH 7.4, equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2 at 32°C, as described previously (Sacktor et al., 1993). Test stimuli of Schaffer collateral/commissural fibers were delivered every 15 sec through widely spaced, bipolar tungsten electrodes, in order to maximize the number of stimulated afferents. Current intensity (25–50 μA, 0.1 msec duration) was set to produce ∼50% of the maximal EPSP amplitude. Field EPSPs were recorded using standard glass microelectrodes, resistance 5–10 MΩ, filled with the saline solution and placed in stratum radiatum. After at least 10 min of stable recordings, LTD was induced by 3 Hz stimulation for 5 min (Dudek and Bear, 1992; Mulkey and Malenka, 1992). Analysis of the initial 10–50% of the field EPSP slope was performed with Superscope (GW Instruments, Somerville, MA).

LTD was saturated by three sequential stimulations of 3 Hz, 5 min at 30 min intervals. In some experiments, an LTD-saturated pathway equal in EPSP size to the original baseline was obtained by increasing the intensity of the test stimulus after the first two 3 Hz stimulations (see Fig. 2a). The ability to saturate LTD while recruiting naive synapses during the increase in stimulus strength is presumably because the depression obtained by 5 min of 3 Hz stimulation (the optimal frequency for depression; Dudek and Bear, 1992) is already close to saturation (Fig. 2c), and because only a fraction of the EPSP response is modifiable by LTD (∼45%; Dudek and Bear, 1993) (see also Fig. 2c). The stimulus strength was not increased after the last 3 Hz stimulation to avoid the addition of naive synapses before application of chelerythrine (Fig.2a).

Fig. 2.

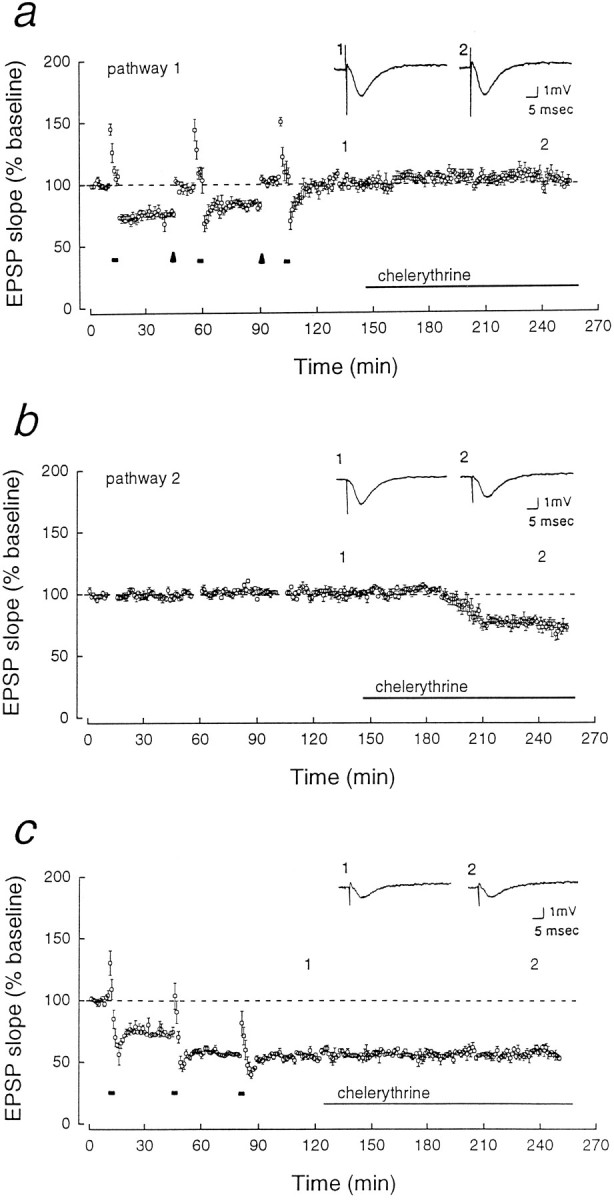

LTD occludes the effect of chelerythrine. Two pathways (shown in a and b) were obtained by placing stimulating electrodes on opposite sides of a recording electrode in CA1 radiatum. The pathways were determined to be separate by the independence of paired-pulse facilitation (data not shown).a, In pathway 1, LTD was saturated by three sequential 5 min trains of 3 Hz stimulation (short bars). To observe the effect of chelerythrine on EPSP responses equivalent in size to those in Figure 1c, the depressed EPSP was reset to the original baseline by increasing the test stimulus strength (arrowheads). Application of chelerythrine (1 μm) caused no additional depression (the responses were 103.0 ± 1.9% of the baseline after 70 min of application,n = 5). b, In the second pathway, which did not receive 3 Hz stimulation, the chelerythrine resulted in depression to 76.5 ± 2.3% of the baseline after 70 min of application (p < 0.001, Student’s pairedt test, n = 5). c, LTD saturated without readjusting the test stimulus intensity (EPSP depression to 55.1 ± 0.6%) also occluded the effect of chelerythrine (the EPSP was 101.4 ± 3.7% of the saturated LTD response after 70 min of application; n = 3).

Drug application was done by changing the chamber infusion to a saline solution containing the agent. The flow was maintained at 0.2 ml/min in a chamber volume of 1.5 ml. In the figures, the left end of the long horizontal bar is positioned at the beginning of the exchange. The explanation for the apparent differences in the time of onset of the synaptic depression by chelerythrine, which appears to depend on the previous history of synaptic activity in the slice (see Figs.1c, 2b, 3b), is not known, but could be attributable to differences in the availability of unphosphorylated protein substrate with which the drug competes. Applications of chelerythrine did not affect the level of PKMζ in slices (PKMζ in slices incubated with chelerythrine for 90 min was 105.9 ± 5.5% of adjacent control slices, set at 100%,n = 5).

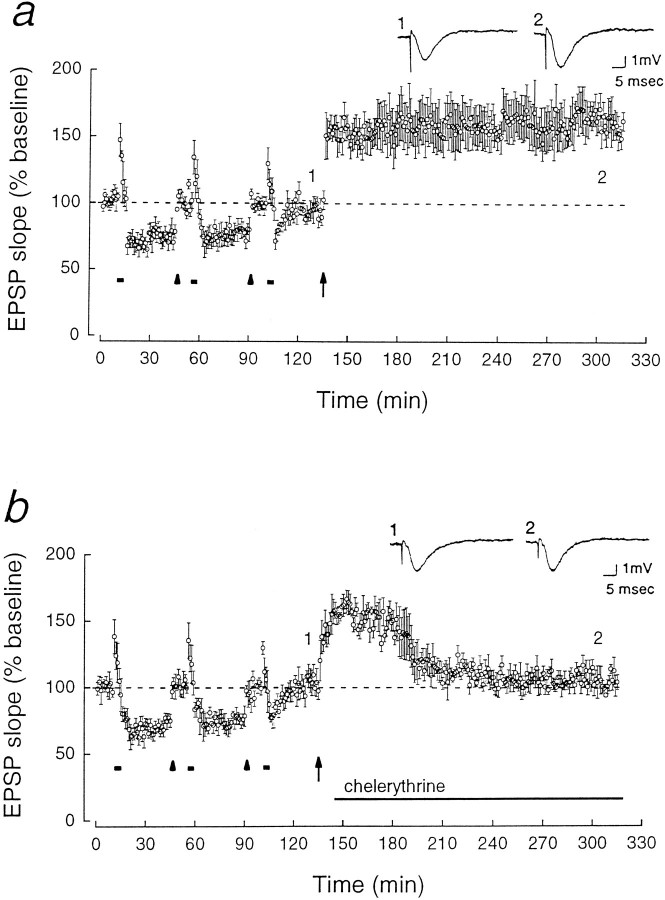

Fig. 1.

Reduction of PKC activity by kinase inhibitors mimics and occludes LTD. In each panel, representative field EPSPs (above) correspond to numbered points in the time course of initial EPSP slopes (below; mean ± SEM, normalized to baseline responses set at 100%). a, LTD induced by 3 Hz stimulation for 5 min (stimulation shown byshort horizontal bar; n = 5).b, H7 [1-(5-isoquinolinesulfonyl)-2-methylpiperazine dihydrochloride, 10 μm, Seikagaku, long horizontal bar] applied to the bath resulted in synaptic depression and prevention of LTD. To ensure equivalent postsynaptic responses to 3 Hz stimulation, the intensity of test stimulation was increased to reset the EPSP slope to the baseline that existed before the application of the drug (the EPSP responses during the readjustment, which begins at thearrowhead, are not shown). Thirty minutes after 3 Hz stimulation (short bar, n = 5), the EPSP was 94.8 ± 1.8% of the original baseline. c, Chelerythrine (1 μm, Calbiochem) applied to the bath likewise mimicked and prevented LTD. The experimental procedure is the same as in b. The EPSP response was 99.5 ± 1.8% of the baseline 30 min after 3 Hz stimulation (n = 5).

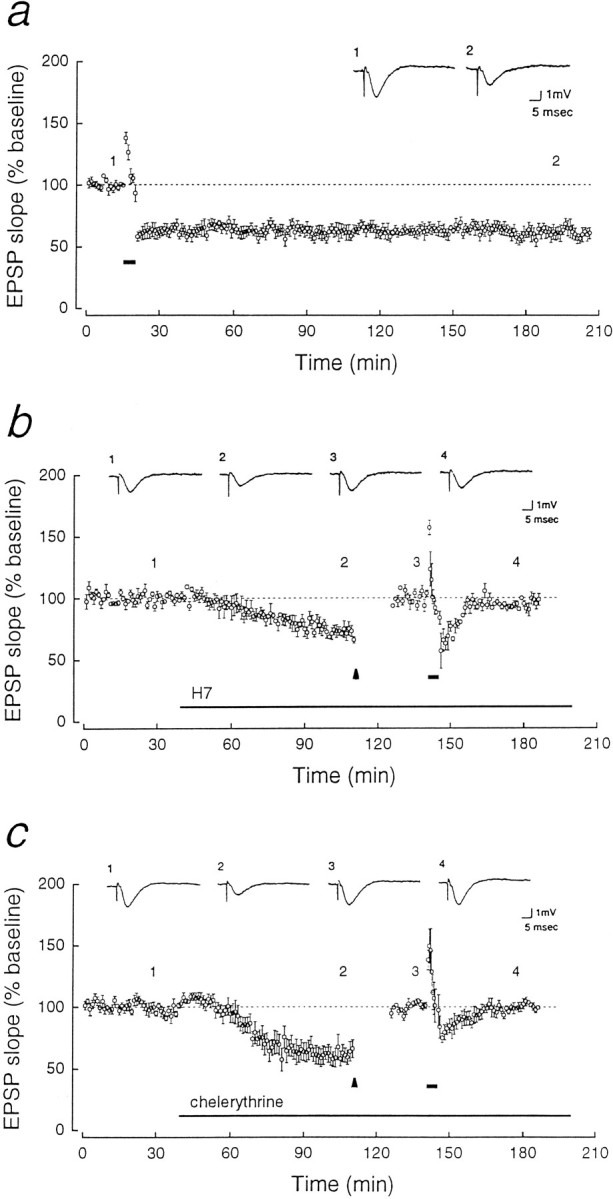

Fig. 3.

LTP after LTD restores the ability of chelerythrine to depress synaptic transmission. a, A synaptic pathway in which LTD was saturated as in Figure2a was then potentiated by a 1 sec, 100 Hz train (shown at arrow). The potentiated EPSP response was 157.7 ± 10.3% of the baseline 2 hr after the high-frequency tetanus (p < 0.02, n = 5).b, Chelerythrine (1 μm) applied 10 min after the high-frequency tetanus decreased the potentiated response. Two hours after the tetanus, the EPSP response was 104.8 ± 3.4% of the pre-LTP baseline (n = 5).

Immunoblots. Immunoblots of PKC isozymes in supernatant and membrane-particulate fractions, obtained by 100,000 × g centrifugation of isolated CA1 regions, were performed as described previously (Sacktor et al., 1993). C-terminal antisera are specific to isozyme type (Sacktor et al., 1993). [Recently, a second atypical isoform, ι/λ, has been identified (Selbie et al., 1993;Akimoto et al., 1994). Although we did not examine ι/λ in LTD, immunoblots with antiserum to the catalytic domain of ι/λ detected PKCι/λ but did not consistently detect PKMι/λ in rat hippocampus (J. Libien and T. C. Sacktor, unpublished data).] Equal amounts of total protein, determined by a modified Bradford assay (Read and Northcote, 1981; Simpson and Sonne, 1982) from the fractions of control and stimulated CA1 regions were loaded in adjacent lanes of the immunoblot. To eliminate pipetting error further, the levels of PKC isozymes were also normalized to levels of tubulin in each lane detected with a monoclonal antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (see Fig.4c). Normalizations by tubulin and by Bradford assay gave equivalent results (data not shown). The immunoblot assay was in the linear range of detection as determined by densitometric scanning of the bands with an XRS 6cx scanner (Omni- Media, Torrance, CA) using NIH-Image software.

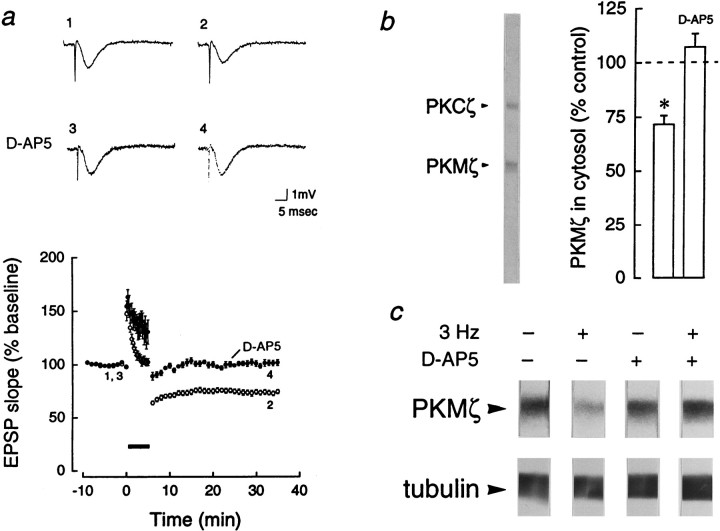

Fig. 4.

NMDA receptor-dependent downregulation of PKMζ in LTD. a, Top, Representative field EPSP traces before (traces 1, 3) and 30 min after (traces 2, 4) 3 Hz stimulation. The decrease in initial slope during LTD (1, 2) was blocked by bath application of the NMDA-receptor antagonistd(−)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP5; 50 μm; 3, 4).Bottom, LTD was maintained for 30 min (open circles, n = 12). d-AP5 blocked LTD (closed circles, n = 12).b, Left, Representative immunoblot with antiserum to ζ, showing PKCζ and PKMζ,Mr = 72 and 55 kDa, respectively.Right, Bar graph showing mean percent change of cytosolic PKMζ in CA1 regions 30 min after 3 Hz stimulation, relative to PKMζ in adjacent control CA1 regions that received only test stimulation, set at 100% (p < 0.0001, Student’s paired t test, n = 13, in which decreases were observed in all experiments). Applications ofd-AP5 blocked the decrease in PKMζ, assayed 30 min after 3 Hz stimulation (n = 6). c,Top, Immunoblots of PKMζ, representative of the experiments in b. Bottom, No changes in levels of tubulin were observed in adjacent sections of the immunoblots.

Constitutive PKC activity. Constitutive PKC activity was measured as described in Klann et al. (1993). Five microliters of cytosolic fractions from control or LTD CA1 regions, containing on average 0.5 μg of total protein, were added to a reaction mixture (50 μl) containing: 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mmMgCl2, 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 25 μg/ml leupeptin, 2.5 mm EGTA, 2 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 5–6 μCi in 100 μm[γ-32P]ATP, and 10 μm neurogranin (28–43) peptide (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). The reaction was performed for 2 min at 37°C, which is in the linear range of the assay for time and protein concentration (data not shown). The reaction was stopped by addition of 25 μl of 100 mm cold ATP and 100 mm EDTA, and 25 μl of the assay mixture was spotted onto phosphocellulose paper. Constitutive PKC activity was measured as the difference between counts incorporated in the presence and absence of neurogranin (28–43) substrate.

RESULTS

LTD and the synaptic depression caused by the reduction of PKC activity are mutually occlusive

Homosynaptic LTD of Schaffer collateral/commissural-CA1 synaptic transmission was induced in rat hippocampal slices by 3 Hz, 5 min stimulation of afferent fibers (Dudek and Bear, 1992; Mulkey and Malenka, 1992). The initial slope of the field EPSP, stable for 2 hr after the stimulation, was 62.9 ± 4.0% of the baseline EPSP (mean baseline set at 100%, p < 0.001, Student’s paired t test, n = 5; Fig. 1a). Synaptic depression could also be produced by applications of H7 (10 μm) (Muller et al., 1990; Leahy and Vallano, 1991; Waxham et al., 1993), an inhibitor acting on the ATP-binding site of protein kinases (72.2 ± 3.3% of the baseline after 70 min of application, p < 0.02, n = 5; Fig.1b). The application of H7 prevented LTD (Fig.1b).

Whereas H7 is a nonspecific inhibitor of kinases with complex effects (Amador and Dani, 1991; Leahy and Vallano, 1991), chelerythrine (toddaline) is a highly selective inhibitor of PKC, acting on the protein substrate-binding site of the enzyme’s catalytic domain (Herbert et al., 1990), which is particularly useful for studying PKC’s constitutively active catalytic fragment PKM. Chelerythrine at 1 μm has no inhibitory effect either on CaM-kinase II or on the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (Herbert et al., 1990). Application of 1 μm chelerythrine caused a synaptic depression similar to H7 (61.5 ± 6.5% of the baseline EPSP,p < 0.005, n = 5), which also prevented LTD (Fig. 1c). (Wash-out of chelerythrine was not possible with several hours of perfusion with drug-free saline; data not shown.) Neither H7 nor chelerythrine suppressed a short-term depression (STD), lasting 15–20 min after the 3 Hz stimulation, indicating that other signal transduction pathways are retained in the presence of the inhibitors.

Although the reduction of kinase activity by chelerythrine may decrease synaptic efficacy by a mechanism similar to LTD, an alternative interpretation is that the drug depresses synaptic transmission and blocks LTD induction by separate mechanisms. We therefore determined whether, conversely, established LTD occluded the depression caused by chelerythrine. LTD was saturated by multiple trains of low-frequency stimulation (Mulkey and Malenka, 1992; Dudek and Bear, 1993) (Fig.2a). To observe the effect of chelerythrine on synaptic responses that were not diminished, we reset the EPSP slope to the original baseline by increasing the stimulus strength 30 min after each of the first two 3 Hz trains. The stimulation intensity was not increased after the last 3 Hz train to avoid the addition of naive synapses. Chelerythrine caused no depression in the synaptic pathway in which LTD had been saturated (Fig. 2a). In contrast, the drug depressed an independent, naive synaptic pathway in the same slice (Fig.2b), indicating that the occlusion was specific to synapses that had undergone LTD. Chelerythrine also had no effect on pathways in which LTD was saturated without increasing the stimulus strength (Fig. 2c).

Repotentiation restores the ability of chelerythrine to depress synaptic strength

Because the ability of chelerythrine to depress synaptic transmission was eliminated by LTD, we next asked whether potentiation (or more precisely, “repotentiation”) restored the effect of chelerythrine. A high-frequency tetanus given after saturated LTD caused an enhancement of synaptic transmission that lasted for at least 2 hr (Fig. 3a). Applications of chelerythrine, initiated 10 min after the high-frequency tetanus to avoid an effect on LTP induction, reduced the potentiated EPSP response to the pre-LTP (saturated LTD) level (Fig. 3b). These experiments with kinase inhibitors, taken together, provide initial evidence for the bidirectional regulation of synaptic efficacy by PKC in LTP/LTD. To characterize the underlying molecular mechanisms for this regulation, we directly examined the changes in PKC isoforms dur- ing LTD.

Downregulation of PKMζ in LTD

PKC is active in two forms: translocated to membrane (Kraft and Anderson, 1983), as in LTP induction, and proteolytically activated to PKM (Takai et al., 1977), as in LTP maintenance. PKC isoforms in the cytosol and membrane-particulate fractions of CA1 regions from LTD slices, receiving 3 Hz stimulation, were compared with CA1 regions from adjacent control slices receiving test stimulation (Fig.4a,b). PKCs α, βI, βII, γ, δ, ε, η-related (Sublette et al., 1993), ζ, and PKMζ were assayed with immunoblots using isozyme-specific antisera. [The Western blots were linear with respect to total protein concentration (Sacktor et al., 1993); equal loading onto adjacent lanes and transfer to nitrocellulose were confirmed by probing with antiserum to tubulin (Fig. 4c).] Thirty minutes into the maintenance phase of LTD, the level of cytosolic PKMζ was reduced (71.6 ± 4.1%, p < 0.0001, Student’s pairedt test, n = 13; Fig.4b,c), whereas the levels of the membrane-bound forms of PKC were unchanged (data not shown). Of the other cytosolic species, PKCs γ and ε were also found to decrease (64.8 ± 4.9%, p < 0.0001; 63.5 ± 9.0%,p < 0.05; Bonferroni, n = 13). We examined the possibility that there were proteases active during homogenization and subcellular fractionation that might have contributed to the loss of PKMζ, despite protease inhibitors in the homogenization buffer. LTD and control CA1 regions were boiled in sample buffer to denature cellular proteins immediately without fractionation (Sacktor et al., 1993). Decreases were again observed specifically for PKMζ, PKCγ, and PKCε (76.2 ± 9.3, 76.9 ± 6.9, and 72.5 ± 11.7%, respectively, eachp < 0.05, Student’s paired t test,n = 11).

Because LTD has been reported to require the activation of NMDA receptors (Dudek and Bear, 1992; Mulkey and Malenka, 1992), we examined whether the downregulation of PKMζ, PKCγ, and PKCε shared this requirement. The NMDA-receptor antagonistd(−)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP5; 50 μm) blocked both the reductions of field EPSP (100.1 ± 1.9%, n = 28; Fig.4a) and the loss of cytosolic PKMζ (107.1 ± 6.1%, n = 6; Fig. 4b,c), PKCγ (110.1 ± 12.3%, n = 6), and PKCε (114.7 ± 19.1%,n = 3) 30 min after the 3 Hz stimulation. The other isozymes in the cytosol remained unchanged (data not shown).

Downregulation of constitutive PKC activity in LTD

In LTP, an increase of constitutive PKC activity in the cytosolic fractions of CA1 has been observed by Klann et al. (1991, 1993). This activity was determined, in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors, by Ca2+/lipid-independent phosphorylation of an exogenous neurogranin-based peptide substrate that is selective for PKC (Klann et al., 1993). We found that cytosolic constitutive PKC activity decreased in CA1 regions 30 min into the maintenance of LTD (the mean percent decrease in activity was to 82.6 ± 6.4% of the activity in adjacent control regions from the same hippocampus, set at 100%,n = 8, p < 0.05). The mean constitutive PKC activity in the control slices was 649 ± 117 pmol/min/mg; the mean activity in the LTD slices was 511 ± 78.

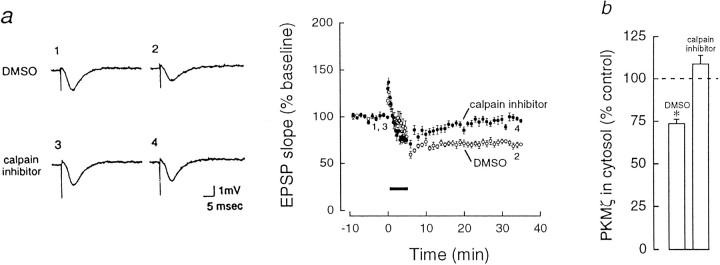

An essential role for calpain proteolysis in LTD and PKMζ downregulation

The rise in postsynaptic Ca2+ through the NMDA receptor is believed to activate Ca2+-dependent enzymes that induce LTD (Dudek and Bear, 1992; Mulkey and Malenka, 1992). Because calpain, a Ca2+-dependent protease, may contribute to both the formation and the degradation of PKM (Al and Cohen, 1993), we examined the effect on LTD of the application of calpain inhibitor I, a selective, membrane-permeable inhibitor of the protease that effectively blocks LTP, but not early NMDA-dependent potentiation (Cerro et al., 1990; Denny et al., 1990a; Fitzpatrick et al., 1992). Calpain inhibitor I [6 μm in 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] blocked the formation of LTD without affecting STD (Fig.5a) and prevented the decrease of PKMζ (108.7 ± 5.2%, n = 6; Fig. 5b). DMSO alone had no effect on either LTD (Fig. 5a) or the downregulation of PKMζ (73.6 ± 2.6%, p < 0.01, n = 5; Fig. 5b). The downregulation of PKCγ was also blocked by calpain inhibitor I (105.3 ± 3.1%,n = 6, compared with 63.6 ± 5.5% in DMSO alone,p < 0.01, n = 5).

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of calpain prevents LTD and the downregulation of PKMζ. a, Left, Representative EPSPs corresponding to the numbers in time course atright. Right, Time course of EPSP responses after 3 Hz stimulation in the presence of calpain inhibitor I (N-acetyl-Leu-Leu-norleucinal, Boehringer Mannheim, 6 μm in 0.1% DMSO, closed circles) and in DMSO alone (0.1%, open circles). Calpain inhibitor I, added 1–3 hr before 3 Hz stimulation, blocked the formation of LTD (EPSP responses were 95.8 ± 2.5% of the baseline 30 min after the 3 Hz stimulation, n = 12). No change in baseline synaptic responses was observed during the addition of the drug (data not shown). DMSO alone had no effect on LTD (71.5 ± 2.2% of baseline, p < 0.0001, n = 12). b, Inhibition of calpain proteolysis prevented the downregulation of PKMζ. PKMζ downregulation was observed in the presence of DMSO alone.

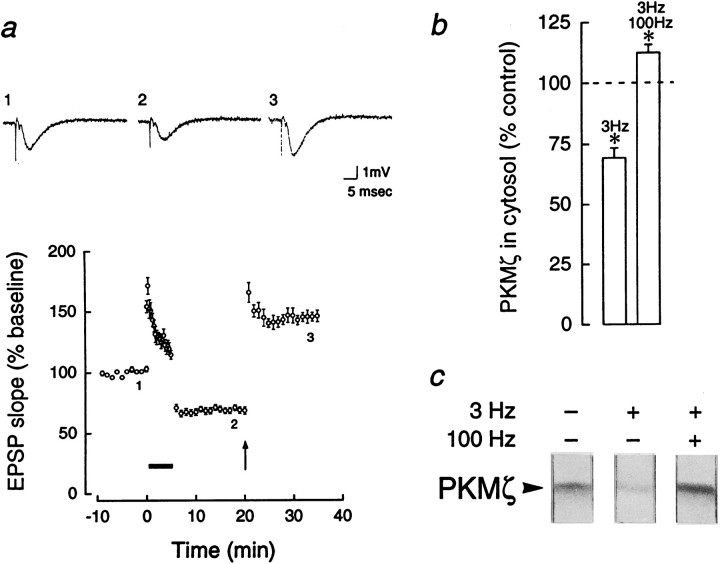

Bidirectional regulation of PKMζ in LTP/LTD

Because we have previously observed increases of PKMζ after potentiation of baseline synaptic transmission (Sacktor et al., 1993; Osten et al., 1996), we examined the bidirectional regulation of PKMζ in a single synaptic pathway. PKMζ was measured in slices in which LTD was reversed by high-frequency stimulation (Fig.6a) and compared with adjacent slices that received either LTD or only test stimulation. The level of PKMζ in slices receiving 100 Hz tetanic trains after a 3 Hz train was higher than in adjacent slices receiving 3 Hz alone (112.2 ± 3.3 vs 69.3 ± 4.1%, p < 0.01, Bonferroni,n = 8; Fig. 6b,c). PKMζ in the potentiated slices was also higher than in the slices receiving only test stimulation (set at 100%, p < 0.05, Bonferroni,n = 8; Fig. 6b,c).

Fig. 6.

Bidirectional regulation of PKMζ in LTP/LTD. Adjacent slices were divided into three groups that received: (1) test stimulation, (2) 3 Hz stimulation, showing LTD for 30 min, and (3) 3 Hz stimulation, followed after 15 min by a high-frequency stimulation, reversing the depression. The high-frequency stimulation consisted of two 1 sec 100 Hz trains separated by 10 sec, at a current set to produce 70% of the maximal EPSP response. The reversal was confirmed by following the EPSP for an additional 15 min. a,Top, Representative traces of field EPSPs showing LTD and reversal. Bottom, Reversal of LTD by high-frequency stimulation, denoted by arrow (n = 12). b, A decrease in cytosolic PKMζ, relative to the baseline set at 100%, is seen after LTD (3 Hz), whereas an increase in PKMζ above the baseline is observed when LTD is reversed by high-frequency stimulation (3 Hz, 100 Hz). Significant differences in PKMζ were found by Bonferroni for control versus LTD (p < 0.01), control versus reversal (p < 0.05), and reversal versus LTD (p < 0.01); n = 8. c, Representative immunoblots of PKMζ, demonstrating control, 3 Hz LTD, and 3 Hz reversed by 100 Hz. In addition, PKCε was downregulated in slices receiving 3 and 100 Hz (53.2 ± 6.5) and in slices receiving only 3 Hz (47.5 ± 9.7; both significantly different from controls, p < 0.01). PKCγ was decreased only in LTD slices (57.1 ± 4.1, p < 0.05), but not in slices receiving 3 and 100 Hz (108.9 ± 7.0).

DISCUSSION

Bidirectional regulation of autonomous PKC in the maintenance of LTP/LTD

Chelerythrine, an inhibitor of PKC’s catalytic domain, decreases basal synaptic transmission, occludes the maintenance of LTD, and reverses the maintenance of LTP. These observations suggest that PKC that is constitutively active during very low-frequency test stimulation contributes to basal synaptic efficacy, decreases in LTD, and increases in LTP. Although occlusion experiments are inherently limited in a complex system in which multiple molecular pathways are in play, our results may help to explain the inconsistencies among previous reports describing the effects of kinase inhibitors on “naive” and potentiated synapses. Whereas some of these earlier studies have interpreted the depression of baseline synaptic transmission by kinase inhibitors as complicating the analysis of LTP (Muller et al., 1990; Leahy and Vallano, 1991), our experiments suggest that PKC maintains synaptic transmission in both naive and potentiated synapses. Therefore, the discrepancies among previous studies (Malinow et al., 1988; Colley et al., 1990 vs Muller et al., 1990; Leahy and Vallano, 1991; Waxham et al., 1993) may be attributable to differences in the balance between potentiation and depression of the baseline accrued before experimentation, perhaps during the course of normal learning and development, rather than to differences in the mechanism of LTP.

These studies with kinase inhibitors, considered together, suggest the nature of the molecular mechanism maintaining synaptic strength. Sphingosine, polymyxin B, and calphostin C, which act on PKC’s regulatory domain, block LTP induction (Malinow et al., 1988; Colley et al., 1990; Lopez-Molina et al., 1993). These inhibitors do not reverse the later maintenance of LTP or depress synaptic transmission. In contrast, H7 and chelerythrine, inhibitors that act on different sites of the catalytic domain of PKC (including PKCζ; E. Sublette and T. C. Sacktor, unpublished observations), both reverse LTP maintenance and decrease baseline synaptic transmission. This suggests that the molecular mechanisms bidirectionally regulating synaptic transmission involve a constitutively active PKC, perhaps PKMζ, although there may be other forms of autonomous PKC to be characterized in future studies. In addition, however, staurosporine and its analog K252a, inhibitors acting on the catalytic domain of many kinases, including conventional PKCs and CaM-kinase II (Ward and O’Brian, 1992; Huber et al., 1995), have been reported not to reverse LTP maintenance (Denny et al., 1990b;Muller et al., 1992; Huber et al., 1995) (but see Matthies et al., 1991). These results appear to contradict the experiments with H7 and chelerythrine. Staurosporine, however, is not an effective inhibitor of the catalytic domain of the atypical ζ isoform that is central to our hypothesis (McGlynn et al., 1992; Kochs et al., 1993). Further experimental confirmation of ζ ’s role awaits the development of additional agents that specifically inhibit PKC isoforms.

PKC isozymes and LTP/LTD

Although these inhibitor studies suggest the potential importance of constitutive PKC activity in LTP/LTD, to characterize the molecular mechanisms underlying this persistent modulation we examined the regulation of PKC isoforms. We observed that three cytosolic PKC species, PKCγ, PKCε, and PKMζ, decreased in LTD. The downregulation of PKCγ (the most sensitive of the conventional PKCs to proteolysis by calpain; Kishimoto et al., 1989) could conceivably contribute to a loss of constitutive PKC activity. This isoform, however, is not fully autonomous when purified from cytosol (Huang et al., 1986) and, like PKCε, does not consistently increase or persistently translocate in LTP (Sacktor et al., 1993; Osten et al., 1996). Alternatively, PKCγ may participate in the interactions between LTD and LTP induction, as suggested by observations in hippocampal slices lacking the isozyme (Abeliovich et al., 1993). PKMζ is the only PKC species observed to be both fully autonomous (Nakanishi et al., 1993; Sacktor et al., 1993) and bidirectionally regulated in LTP/LTD.

PKMζ and the divergence and convergence of signal transduction pathways in LTP/LTD

Because PKMζ is common to the molecular mechanisms of LTP and LTD, its regulation must be placed into the context of the complex, multiple signal transduction pathways that have been implicated in these forms of long-term synaptic plasticity. LTP and LTD are initiated by different patterns of afferent activity, and both are triggered by neurotransmitter release, NMDA-receptor activation, and the subsequent rise in postsynaptic Ca2+. The signal transduction mechanisms of LTP and LTD induction then diverge, presumably in part as a result of different levels, kinetics, or locations of the rise in postsynaptic Ca2+. In LTP induction, several protein kinases, CaM-kinase II (Lisman, 1994), full-length PKCs (Sacktor et al., 1993), cGMP-dependent kinase (Zhuo et al., 1994), cAMP-dependent kinase (Huang and Kandel, 1994; Blitzer et al., 1995), and tyrosine kinases (O’Dell et al., 1991), all appear to act interdependently (Huber et al., 1995; Wang and Kelly, 1995), so that the inhibition of any single pathway prevents LTP. On the other hand, calcineurin has been implicated in the induction mechanisms of LTD (Mulkey et al., 1994). Because NMDA-receptor antagonists block both the increase of PKMζ in LTP (Sacktor et al., 1993; Osten et al., 1996) and its decrease in LTD (Fig. 4), our findings indicate that these divergent Ca2+-dependent pathways lead to differential proteolytic processing of ζ—limited proteolysis of PKCζ forming PKMζ in LTP, and downregulation of PKMζ in LTD.

Although the changes in PKMζ are bidirectional, the proteolytic processing of ζ in LTP and LTD need not involve separate proteases. Calpain inhibitors, for instance, block both LTP (Cerro et al., 1990;Denny et al., 1990a; Fitzpatrick et al., 1992) and LTD (Fig. 5). Proteolysis by calpain is triggered by a rise in Ca2+ but is regulated further by modulation of the proteolytic substrate. Accessibility of cleavage sites on calpain substrates, for example, has been shown to be controlled by phosphorylation (Chen and Stracher, 1989). Similarly, the extent of PKC proteolysis by calpain and other proteases is determined by the conformational state of the kinase (Kishimoto et al., 1983; Orr et al., 1992; Al and Cohen, 1993). Therefore, one scenario for the regulation of PKMζ is that calpain is activated in both LTP and LTD, but the phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of ζ by kinases and phosphatases in induction determines the accessibility of proteolytic sites and, therefore, the direction of the change in PKM. Another possibility is that differential increases in postsynaptic Ca2+ during LTP and LTD activate distinct isoforms of calpain that might have specific cleavage sites on ζ, as observed for the conventional PKCs in vitro (Kishimoto et al., 1989; Suzuki et al., 1992). Although both LTP and LTD might require the proteolysis of ζ, repeated cycles of LTP/LTD would not deplete the levels of the isoform because new protein synthesis of ζ may be rapid in LTP (Osten et al., 1996) .

While the signal transduction pathways of LTP and LTD converge on ζ in the transition from induction to maintenance, actions at the final effector mechanisms for these forms of plasticity may once again diverge. Thus, there is evidence to support modifications presynaptically (Bliss et al., 1986; Malgaroli and Tsien, 1992;Bolshakov and Seigelbaum, 1994; Stevens and Wang, 1994), postsynaptically (Davies et al., 1989; Zalutsky and Nicoll, 1990;Manabe et al., 1992; Isaac et al., 1995; Liao et al., 1995; Oliet et al., 1996), and even on different postsynaptic receptors (Muller and Lynch, 1988; Kullman, 1994; Selig et al., 1995). Our experiments suggest that these modifications are maintained by autonomous PKC phosphorylation that is increased or decreased by the pattern of ongoing afferent activity. The bidirectional regulation of PKMζ provides a plausible and parsimonious molecular mechanism for this persistent modulation.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health and the Epilepsy Foundation of America. We thank Peter Bergold, Eric Kandel, Robert Malinow, Pavel Osten, James Schwartz, Wayne Sossin, Elizabeth Sublette, and Robert K. S. Wong for advice during the preparation of this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Todd C. Sacktor, Laboratory of Molecular Neuroscience, Departments of Pharmacology and Neurology, P.O. Box 29, State University of New York at Brooklyn, 450 Clarkson Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11203.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeliovich A, Chen C, Goda Y, Silva AJ, Stevens CF, Tonegawa S. Modified hippocampal long-term potentiation in PKCγ mutant mice. Cell. 1993;75:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90613-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akimoto K, Mizuno K, Osada S-I, Hirai S-I, Tanuma S-I, Suzuki K, Ohno S. A new member of the third class in the protein kinase C family, PKCλ, expressed dominantly in an undifferentiated mouse embryonal carcinoma cell line and also in many tissues and cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12677–12683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Z, Cohen CM. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-stimulated phosphorylation of erythrocyte membrane skeletal proteins is blocked by calpain inhibitors. Biochem J. 1993;296:675–683. doi: 10.1042/bj2960675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amador M, Dani JA. Protein kinase inhibitor, H-7, directly affects N -methyl-d-aspartate receptor channels. Neurosci Lett. 1991;124:251–255. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bliss TVP, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bliss TVP, Douglas RM, Errington ML, Lynch MA. Correlation between long-term potentiation and release of endogenous amino acids from dentate gyrus of anaesthetized rats. J Physiol (Lond) 1986;377:391–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blitzer RD, Wong T, Nouranifar R, Iyengar R, Landau EM. Postsynaptic cAMP pathway gates early LTP in hippocampal CA1 region. Neuron. 1995;15:1403–1414. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolshakov VY, Seigelbaum SA. Postsynaptic induction and presynaptic expression of hippocampal long-term depression. Science. 1994;264:1148–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.7909958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cerro SD, Larson J, Oliver MW, Lynch G. Development of hippocampal long-term potentiation is reduced by recently introduced calpain inhibitors. Brain Res. 1990;530:91–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90660-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen M, Stracher A. In situ phosphorylation of platelet actin-binding protein by cAMP-dependent protein kinase stabilizes it against proteolysis by calpain. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14282–14289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colley PA, Sheu F-S, Routtenberg A. Inhibition of protein kinase C blocks two components of LTP persistence leaving initial potentiation intact. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3353–3360. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-10-03353.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies SN, Lester RA, Reyman KG, Collingridge GL. Temporally distinct pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms maintain long-term potentiation. Nature. 1989;338:500–503. doi: 10.1038/338500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denny JB, Polan-Curtain J, Ghuman A, Wayner WJ, Armstrong DL. Calpain inhibitors block long-term potentiation. Brain Res. 1990a;534:317–320. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denny JB, Polan-Curtain J, Rodriguez S, Wayner MJ, Armstrong DL. Evidence that protein kinase M does not maintain long-term potentiation. Brain Res. 1990b;534:201–208. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudek SM, Bear MF. Homosynaptic long-term depression in area CA1 of hippocampus and effects of N -methyl-d-aspartate receptor blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4363–4367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dudek SM, Bear MF. Bidirectional long-term modification of synaptic effectiveness in the adult and immature hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2910–2918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-02910.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzpatrick JS, Shahi K, Baudry M. Effect of seizure activity and calpain inhibitor 1 on LTP in juvenile hippocampal slices. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1992;10:313–319. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(92)90020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukunaga K, Stoppini L, Miyamoto E, Muller D. Long-term potentiation is associated with an increased activity of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:7863–7867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbert JM, Augereau JM, Gleye J, Maffrand JP. Chelerythrine is a potent and specific inhibitor of protein kinase C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;172:993–999. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91544-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu G-Y, Hvalby O, Walaas SI, Albert KA, Skjeflo P, Anderson P, Greengard P. Protein kinase C injection into hippocampal pyramidal cells elicits features of long-term potentiation. Nature. 1987;328:426–429. doi: 10.1038/328426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang K-P, Nakabayashi H, Huang FL. Isozymic forms of rat brain Ca2+-activated and phospholipid-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8535–8539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Y-Y, Kandel ER. Recruitment of long-lasting and protein kinase A-dependent long-term potentiation in the CA1 region of hippocampus requires repeated tetanization. Learn Memory. 1994;1:74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber KM, Mauk MD, Thompson C, Kelly PT. A critical period of protein kinase activity after tetanic stimulation is required for the induction of long-term potentiation. Learn Memory. 1995;2:81–100. doi: 10.1101/lm.2.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hvalby O, Hemmings HC, Jr, Paulsen O, Czernik AJ, Nairn AC, Godfraind J-M, Jensen V, Raastad M, Storm JF, Andersen P, Greengard P. Specificity of protein kinase inhibitor peptides and induction of long-term potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4761–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isaac JTR, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Evidence for silent synapses: implications for the expression of LTP. Neuron. 1995;15:427–434. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kishimoto A, Kajikawa N, Shiota M, Nishizuka Y. Proteolytic activation of calcium-activated, phospholipid-dependent protein kinase by calcium-dependent neutral protease. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:1156–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kishimoto A, Mikawa K, Hashimoto K, Yasuda I, Tanaka S-I, Tominaga M, Kuroda T, Nishizuka Y. Limited proteolysis of protein kinase C subspecies by calcium-dependent neutral protease (calpain). J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4088–4092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klann E, Chen S-J, Sweatt JD. Persistent protein kinase activation in the maintenance phase of long-term potentiation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24253–24256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klann E, Chen S-J, Sweatt JD. Mechanism of protein kinase C activation during the induction and maintenance of long-term potentiation probed using a selective peptide substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8337–8341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kochs G, Hummel R, Meyer D, Hug H, Marme D, Sarre TF. Activation and substrate specificity of the human protein kinase C α and ζ isoenzymes. Eur J Biochem. 1993;216:597–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraft A, Anderson W. Phorbol esters increase the amount of Ca2+ phospholipid-dependent protein kinase associated with plasma membrane. Nature. 1983;301:621–623. doi: 10.1038/301621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kullman DM. Amplitude fluctuations of dual-component EPSCs in hippocampal pyramidal cells: implications for long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1994;12:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leahy JC, Vallano ML. Differential effects of isoquinolinesulfonamide protein kinase inhibitors on CA1 responses in hippocampal slices. Neuroscience. 1991;44:361–370. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90061-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liao D, Jones A, Malinow R. Activation of postsynaptically silent synapses during pairing-induced LTP in CA1 region of hippocampal slices. Nature. 1995;375:400–404. doi: 10.1038/375400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lisman J. The CaM kinase II hypothesis for the storage of synaptic memory. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:406–412. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lledo PM, Hjelmstad GO, Mukherji S, Soderling TR, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II and long-term potentiation enhance synaptic transmission by the same mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11175–11179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez-Molina L, Boddeke H, Muller D. Blockade of long-term potentiation and of NMDA receptors by the protein kinase C antagonist calphostin C. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1993;348:1–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00168529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus: LTP and LTD. Cell. 1994;78:535–538. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malenka RC, Kauer JA, Perkel DJ, Mauk MD, Kelly PT, Nicoll RA, Waxham MN. An essential role for postsynaptic calmodulin and protein kinase activity in long-term potentiation. Nature. 1989;340:554–557. doi: 10.1038/340554a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malgaroli A, Tsien RW. Glutamate-induced long-term potentiation of the frequency of miniature synaptic currents in cultured neurons. Nature. 1992;357:134–139. doi: 10.1038/357134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malinow R, Madison DV, Tsien RW. Persistent protein kinase activity underlying long-term potentiation. Nature. 1988;335:820–824. doi: 10.1038/335820a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malinow R, Schulman H, Tsien RW. Inhibition of postsynaptic PKC or CaMKII blocks induction but not expression of LTP. Science. 1989;245:862–866. doi: 10.1126/science.2549638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manabe T, Renner P, Nicoll RA. Postsynaptic contribution to long-term potentiation revealed by the analysis of miniature synaptic currents. Nature. 1992;355:50–55. doi: 10.1038/355050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matthies H, Behnisch T, Kase H, Matthies H, Reymann KG. Differential effects of protein kinase inhibitors on pre-established long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal neurons in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1991;121:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90699-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGlynn E, Liebetanz J, Reutener S, Wood J, Lydon NB, Hofstetter H, Vanek M, Meyer T, Fabbro D. Expression and partial characterization of rat protein kinase C-δ and protein kinase C-ζ in insect cells using recombinant baculovirus. J Cell Biochem. 1992;49:239–250. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240490306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mulkey RM, Malenka RC. Mechanisms underlying induction of homosynaptic long-term depression in area CA1 of the hippocampus. Neuron. 1992;9:967–975. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90248-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mulkey RM, Herron CE, Malenka RC. An essential role for protein phosphatases in hippocampal long-term depression. Science. 1993;261:1051–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.8394601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mulkey RM, Endo S, Shenolikar S, Malenka RC. Involvement of a calcineurin/inhibitor-1 phosphatase cascade in hippocampal long-term depression. Nature. 1994;369:486–488. doi: 10.1038/369486a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muller D, Lynch G. Long-term potentiation differentially affects two components of synaptic responses in hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9346–9350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muller D, Buchs P-A, Dunant Y, Lynch G. Protein kinase C activity is not responsible for the expression of long-term potentiation in hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4073–4077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muller D, Bittar P, Boddeke H. Induction of stable long-term potentiation in the presence of the protein kinase C antagonist staurosporine. Neurosci Lett. 1992;135:18–22. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90126-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakanishi H, Brewer KA, Exton JH. Activation of the ζ isozyme of protein kinase C by phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. FASEB J. 1995;9:484–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Dell TJ, Kandel ER, Grant SGN. Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus is blocked by tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Nature. 1991;353:558–560. doi: 10.1038/353558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oliet SHR, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Bidirectional control of quantal size by synaptic activity in the hippocampus. Science. 1996;271:1294–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Orr JW, Keranen LM, Newton AC. Reversible exposure of the pseudosubstrate domain of protein kinase C by phosphatidylserine and diacylglycerol. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15263–15266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osten P, Valsamis L, Harris A, Sacktor TC. Protein synthesis-dependent formation of protein kinase Mζ in long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2444–2451. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02444.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Read SM, Northcote DH. Minimization of variation in the response to different proteins of the Coomassie Blue G dye-binding assay for protein. Anal Biochem. 1981;116:53–64. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90321-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sacktor TC, Osten P, Valsamis H, Jiang X, Naik MU, Sublette E. Persistent activation of the ζ isoform of protein kinase C in the maintenance of long-term potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8342–8346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwartz JH. Cognitive kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8310–8313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Selbie LA, Schmitz-Peiffer C, Sheng Y, Biden TJ. Molecular cloning and characterization of PKCι, an atypical isoform of protein kinase C derived from insulin-secreting cells. J Cell Biol. 1993;268:24296–24302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Selig DK, Hjelmstad GO, Herron C, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Independent mechanisms of long-term depression of AMPA and NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1995;15:417–426. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silva AJ, Stevens CF, Tonegawa S, Wang Y. Deficient hippocampal long-term potentiation in α-calcium-calmodulin kinase II mutant mice. Science. 1992;257:201–206. doi: 10.1126/science.1378648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simpson IA, Sonne O. A simple rapid and sensitive method for measuring protein concentration in subcellular membrane fractions prepared by sucrose density ultracentrifugation. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:424–427. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90608-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stevens CF, Wang Y. Changes in reliability of synaptic function as a mechanism for plasticity. Nature. 1994;371:704–707. doi: 10.1038/371704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sublette E, Naik M, Jiang X, Sacktor TC. Evidence for a new isoform of protein kinase C in rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 1993;159:175–178. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suzuki K, Saido TC, Hirai S. Modulation of cellular signals by calpain. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1992;674:218–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb27490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takai Y, Kishimoto A, Inoue M, Nishizuka Y. Studies on a cyclic nucleotide-independent protein kinase and its proenzyme in mammalian tissue. I. Purification and characterization of an active enzyme from bovine cerebellum. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:7603–7609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang J-H, Feng D-P. Postsynaptic protein kinase C essential to induction and maintenance of long-term potentiation in the hippocampal CA1 region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2576–2580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang J-H, Kelly PT. Postsynaptic injection of Ca2+/CaM induces synaptic potentiation requiring CaMKII and PKC activity. Neuron. 1995;15:443–452. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ward NE, O’Brian CA. Kinetic analysis of protein kinase C inhibition by staurosporine: evidence that inhibition entails inhibitor binding at a conserved region of the catalytic domain but not competition with substrates. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:387–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Waxham MN, Malenka RC, Kelly PT, Mauk MD. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates hippocampal synaptic transmission. Brain Res. 1993;609:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90847-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zalutsky RA, Nicoll RA. Comparison of two forms of long-term potentiation in single hippocampal neurons. Science. 1990;248:1619–1624. doi: 10.1126/science.2114039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhuo M, Hu Y, Schultz C, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Role of guanylyl cyclase and cGMP-dependent protein kinase in long-term potentiation. Nature. 1994;368:635–639. doi: 10.1038/368635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]