Abstract

Neuronal apoptosis is a suspected cause of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Increased levels of amyloid β peptide (Aβ) induce neuronal apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. The underlying molecular mechanism of Aβ neurotoxicity is not clear. The normal concentration of Aβ in cerebrospinal fluid is 4 nm. We treated human neuron primary cultures with 100 nm amyloid β peptides Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 and the control reverse peptide Aβ40–1. We find that although little neuronal apoptosis is induced by either peptide after 3 d of treatment, Aβ1–42 provokes a rapid and sustained downregulation of a key anti-apoptotic protein, bcl-2, whereas it increases levels of bax, a protein known to promote cell death. In contrast, the Aβ1–40 downregulation of bcl-2 is gradual, although the levels are equivalent to those of Aβ1–42-treated neurons by 72 hr of treatment. Aβ1–40 does not upregulate bax levels. The control, reverse peptide Aβ40–1, does not affect either bcl-2 or bax protein levels. In addition, we found that the Aβ1–40- and Aβ1–42- but not Aβ40–1-treated neurons had increased vulnerability to low levels of oxidative stress. Therefore, we propose that although high physiological amounts of Aβ are not sufficient to induce apoptosis, Aβ depletes the neurons of one of its anti-apoptotic mechanisms. We hypothesize that increased Aβ in individuals renders the neurons vulnerable to age-dependent stress and neurodegeneration.

Keywords: amyloid β peptide, human neuron primary cultures, bcl-2, bax, apoptosis, Alzheimer’s disease

Genetic, molecular, and cell biology evidence support a role for the amyloid β peptide (Aβ) of 40 and 42 amino acids (Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42) in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD): (1) Mutations of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), which is normally processed into Aβ and a number of stable fragments, increase the production of Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42 (Citron et al., 1992,1994; Cai et al., 1993; Haass et al., 1994; Suzuki et al., 1994); (2) mutations of presenilin I and II genes of familial AD increase APP mRNA and Aβ levels (Levy-Lahad et al., 1995; Querfurt et al., 1995;Sherrington et al., 1995; Sheuner et al., 1996); (3) the ratio of Aβ1–42 to Aβ1–40 increases in sporadic AD brains (Iwatsubo et al., 1994; Kuo et al., 1996); (4) Down’s syndrome individuals who carry three copies of the APP gene and consequently overexpress APP mRNA and produce excess Aβ invariably develop AD pathology (Wisniewski et al., 1985; Tanzi et al., 1987; Teller et al., 1996); and (5) transgenic mice overexpressing normal APP, mutant APP717, or Aβ develop features of AD pathology (Games et al., 1995; Higgins et al., 1995; Hsiao et al., 1995; LaFerla et al., 1995).

Aβs cause rat hippocampal and cortical neuronal death in vitro (concentrations of 1–100 μm) and in vivo (Yankner et al., 1990; LaFerla et al., 1995). Treatment of cultured neurons with 25–100 μm Aβ induces typical features of apoptosis: neurite beading, membrane blebbing, condensed chromatin, and DNA fragmentation (Forloni et al., 1993; Loo et al., 1993; Watt et al., 1994). Evidence of neuronal apoptosis is also observed in sporadic and familial AD brains (Anderson et al., 1994,1996; Su et al., 1994; Satou et al., 1995; Yamatsuji et al., 1996). The mechanism by which Aβ induces cell death or apoptosis is not yet clearly defined. Aβ alters calcium levels, thereby promoting susceptibility to excitotoxic damage (Mattson et al., 1992), promotes free radical formation (Behl et al., 1994; Shearman et al., 1994), and possibly competes for nerve growth factor low-affinity receptor (Rabizadeh et al., 1994). In glial cells, Aβ induces the production of cytokines, tumor necrosis factor, and reactive nitrogen intermediates, any of which can mediate neuronal cell death (Meda et al., 1995). Furthermore, Aβ induces hyperphosphorylation of tau, which may promote neurofibrillary tangle formation and neurodegeneration (Busciglio et al., 1995).

In the present study, we analyzed the effect of 100 nmAβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 and control reverse peptide Aβ40–1 on human primary neuron cultures. We measured cell death by various techniques and examined the effect of Aβ on neuronal “death” bax and “anti-death” bcl-2 proteins. We do not detect significant cell death with Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, or Aβ40–1, although there is a slight increase in terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) after 72 hr of treatment with Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 compared with Aβ40–1. Interestingly, Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 but not Aβ40–1 downregulate bcl-2. Furthermore, Aβ1–42 upregulates bax. In addition, the Aβ-treated neurons show increased vulnerability to low levels of oxidative stress. We hypothesize that Aβ jeopardizes the natural bcl-2-related protective mechanism in neurons and that this effect may lead to increased neuronal degeneration during age-dependent stresses such as oxidative stress, decreased energy metabolism, or decreasing growth factor levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Neuron cultures. Human primary neurons were prepared as described (LeBlanc, 1995) from fetal brains of 13–17 weeks (Munsick, 1984). The brains were collected from human fetuses at the time of the therapeutic abortion in accordance with the Quebec Health Code (received Institutional Review Board approval). Briefly, the cerebrum is dissociated in trypsin (Life Technologies, Ontario) and deoxyribonuclease I (Boehringer Mannheim, Quebec), filtered through 40 and 130 μm nylon mesh, and plated at 3 × 106cells/ml of high-glucose-containing MEM supplemented with Earle’s salts, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 2 mm glutamine (all from Life Technologies), and 5% decomplemented serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT); 1 mm anti-mitotic fluorodeoxyuridine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) is added to inhibit proliferation of contaminating astrocytes or other dividing cells. Under these conditions, neurons establish healthy neurite networks within 3 d and can be maintained for at least 4 weeks without showing signs of degeneration. Experiments were carried out on neurons 10 d after plating. The neuronal cultures typically contain >90% neurons.

Treatment of neurons with Aβ. Fibrillar Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42 (Bachem Bioscience, Torrance, CA), and control reverse peptide Aβ40–1(Sigma) were prepared by incubating freshly solubilized peptides at 25 μm in sterile distilled water at 37°C for 5 d (Pike et al., 1993). At the beginning of each experiment, Aβ peptides were diluted to 100 nm in complete media. Neurons were treated for 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hr. For the 3 d incubation, the neuron media was changed after 48 hr.

Western blot analysis of bcl-2 and bax. After Aβ peptide treatment on 3 × 106 cells, neurons were washed in PBS and collected in 300 μl NP-40 lysis buffer (50 mmTris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1% NP40, 5 mm EDTA, pH 8.0) containing 0.05% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 μg/ml Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone, and 0.5 μg/ml leupeptin as protease inhibitors (all protease inhibitors from ICN, Montreal). Seventeen microliters of the lysate were submitted to electrophoresis on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and Western blot analysis with monoclonal anti-human bcl-2, sc-509 (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA), polyclonal anti-human bax, sc-493 (Santa Cruz Biotech), or monoclonal anti-human actin (kind gift from Dr. Eugenia Wang, Lady Davis Institute and McGill University). Immunoreactivity was detected using secondary anti-mouse (for bcl-2 and actin) or rabbit (for bax) antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) and substrates nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-chloro-3-indoyl-phosphate (Fisher, Montreal). The resulting Western blots were scanned on a Molecular Dynamics phosphorimager densitometric scanner. The data (pixels) were expressed as standard units, where 1 unit = bcl-2 or bax levels in 0 hr untreated neuron cultures. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired t test of Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42 values compared with those of Aβ40–1.

MTT and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assays. Analysis of released LDH was performed by ELISA using the Cytotoxic 96 kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pharmacia Biotech, Quebec). The MTT reduction assay was carried out using the Cell Proliferation Kit I (Boehringer Mannheim). The MTT assay measures both cell death and proliferation and is based on the conversion of the yellow tetrazolium salt MTT to blue formazan by metabolically active cells. The resulting blue color was measured at absorbance 660nm and 550 nm. MTT reduction was calculated as Abs660nm− Abs550nm, and results are expressed as a percentage of the control untreated sample. Increased absorbance readings with time indicate proliferation, whereas decreased absorbance indicates cell death.

Determination of apoptosis in cells. Neurons were fixed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium citrate. Cells were stained with 0.1 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma) for 20 min, rinsed in PBS, and mounted. TUNEL was performed using the in situ cell death detection kit AP as described by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim, Quebec). DNA ladder was performed on 3 × 106 cells. The cells were washed and harvested in PBS. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was incubated in 50 μl of a proteinase K/sarkosyl solution (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 10 mm EDTA, 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K, and 0.5% sarkosyl) for 2 hr at 50°C; 2.5 μl of RNaseA at 10 mg/ml was added, and the incubation continued for 2 hr at 50°C. The DNA was loaded on a 1.2% agarose gel in 1 × TBE and run at 50 V overnight.

Oxidative stress on neurons preexposed to Aβ. Neurons were treated for 48 hr with Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and Aβ40–1 as described above. The media was replaced with 0, 0.1, and 1.0 μm H2O2 and incubated for another 48 hr. Cells were fixed and processed for TUNEL as described above. Because the number of apoptotic cells was very high in H2O2-treated neurons, five specific areas of each coverslip were counted and added as number of TUNEL-positive cells. The density of neurons required for survival in culture does not allow determination of exact cell numbers in this experiment. Therefore the results are expressed as total number of TUNEL-positive cells rather than percentage.

RESULTS

Neuronal degeneration in Aβ-treated neurons

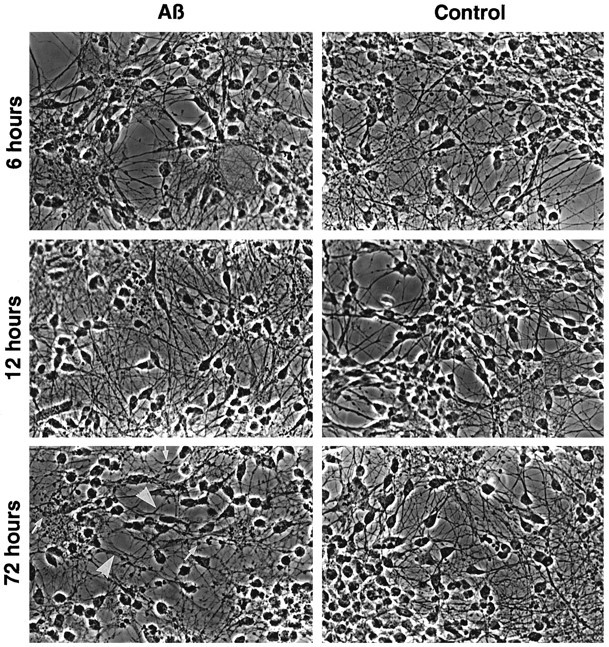

To study the effect of the Aβ peptides, 10-d-old human primary neurons with elaborate neurite networks were treated with 100 nm fibrillar Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 for 6, 12, 18, 24, 48, and 72 hr. Aβ1–40 at 100 nm is ∼25 × that of physiological Aβ concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Nakamura et al., 1994; Van Gool et al., 1994). Physiological concentrations of Aβ1–42 are not known. Our neuron cultures produce ∼1/10 Aβ1–42 compared with Aβ1–40 (A. LeBlanc and S. Younkin, unpublished results). Therefore, 100 nm Aβ1–42 likely represents 250 × the physiological concentration in CSF. Phase-contrast micrography of acid/alcohol-fixed neurons shows that neurons do not undergo neurodegeneration in an acute manner with either Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42 (Fig. 1). At 72 hr of treatment, neurites are thickened and beaded compared with control Aβ40–1-treated cells, but neither the cell density nor the neuronal bodies seem to be affected. The neuritic alterations in Aβ-treated human fetal neurons is variable with each culture, suggesting that the heterogeneity of the sample population results in different degrees of susceptibility to Aβ peptides. In time, however, each neuron culture treated with either Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42 undergoes neurite beading by 72 hr of treatment.

Fig. 1.

Neurite degeneration is observed after 72 hr of treatment with Aβ peptides. Phase-contrast micrograph of primary neuron cultures treated with 100 nm Aβ1–40or Aβ1–42 and control reverse peptide Aβ40–1 for 6, 12, and 72 hr. Arrows show neuritic beading, and arrowheads show neurite thickening.

Studies of cell death in human primary neurons treated with Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and Aβ40–1

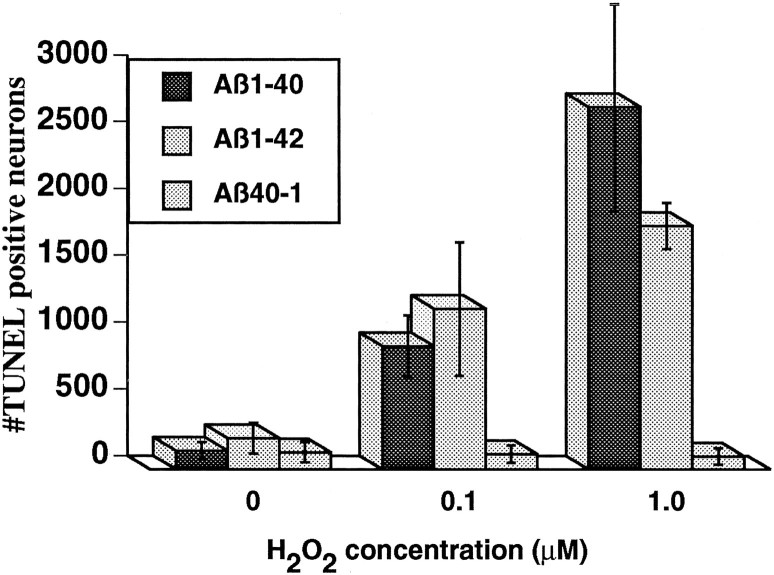

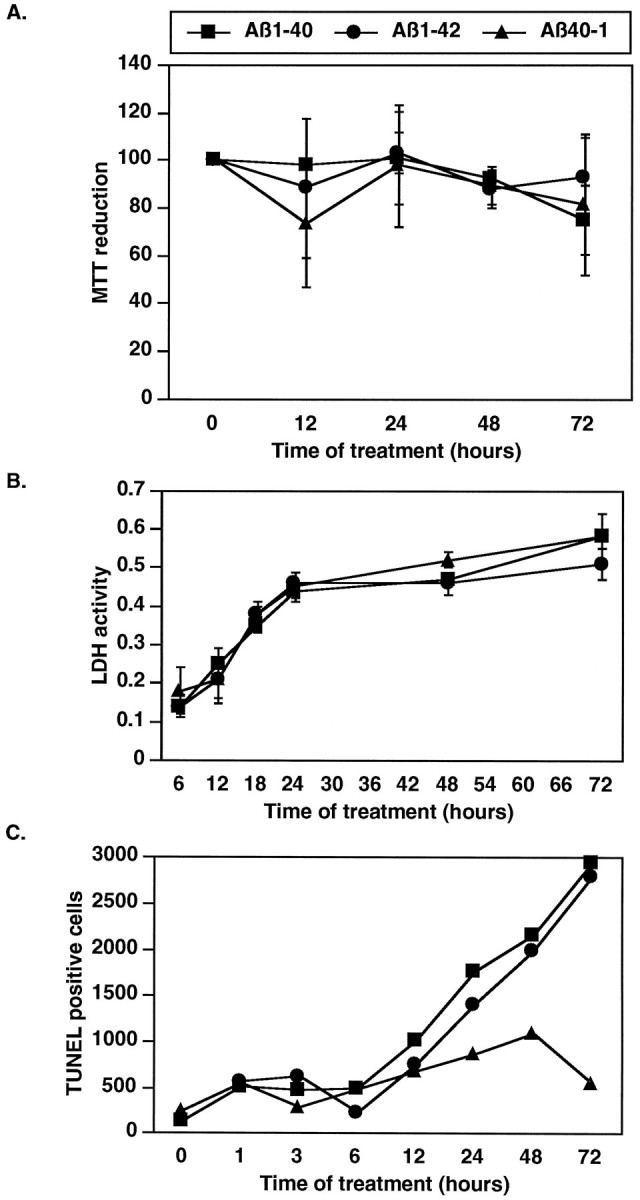

Cell death in culture is generally measured by the reduction of MTT activity and the release of LDH into the media. MTT is a tetrazolium salt cleaved to formazan by the mitochondrial respiratory chain enzyme succinate-tetrazolium reductase, which is active only in live cells. LDH is released into the cell media when cells die by necrosis. Although slightly decreasing MTT levels and increasing LDH activity with time indicate a certain amount of cell death in our cultures, there is no significant difference between Aβ1–40-, Aβ1–42-, and Aβ40–1-treated neurons (Fig.2A,B). To determine whether apoptotic cell death occurred in the neuronal cultures, we looked for fragmented DNA by TUNEL staining, condensed chromatin by propidium iodide staining, and DNA ladder formation as a function of time of treatment. Although few condensed chromatin-containing neurons were observed by propidium iodide staining of three independent experiments (results not shown), ∼2% of the neurons treated with Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 for 72 hr were TUNEL-positive against a background of 0.5% in Aβ40–1-treated neurons (Fig.2C). The absence of DNA ladder formation confirmed the low level of apoptotic neurons in the Aβ-treated cultures (not shown). These results were reproduced in three independent experiments.

Fig. 2.

Aβ peptides do not cause high levels of cell death in neuron primary cultures. Determination of cell death in Aβ1–40-, Aβ1–42-, and Aβ40–1-treated human primary neurons for 12, 24, 48, and 72 hr by MTT reduction assay expressed as a percentage of time 0 (n = 3 ± SEM) (A), LDH release assay (n = 3 ± SEM) (B), and TUNEL-positive cells in a representative experiment (C).

Aβ downregulates bcl-2 and upregulates bax

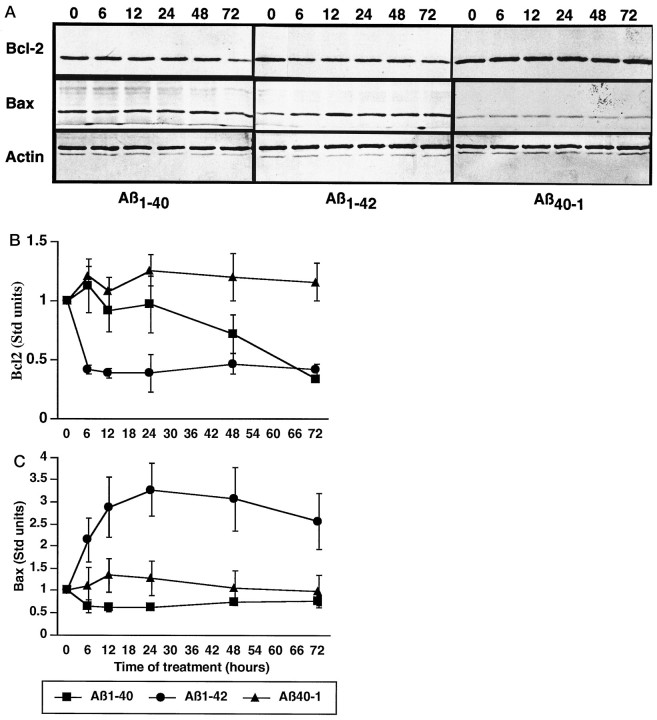

Bcl-2 and bax levels were assessed by Western blots to determine whether these key regulators of apoptosis were involved in the Aβ-induced neurotoxic mechanism (Fig. 3). Using a monoclonal anti-human bcl-2 antibody and a polyclonal antisera to bax, we consistently saw decreased bcl-2 protein levels in Aβ1–40- and Aβ1–42-treated neurons compared with Aβ40–1 control cells (Fig. 3A). With Aβ1–42, we also observed increased bax protein levels. The equivalent levels of actin detected from each time point attest to the equal protein loading in each well of the gel. We quantitated the decreased bcl-2 and increased bax protein levels by densitometric scanning with a phosphorimager. We find that the bcl-2 protein level normalized to untreated cultures (0 hr) is rapidly reduced by >50% in Aβ1–42-treated neurons compared with Aβ40–1-treated cells (Fig. 3B). The effect is observed within 6 hr of treatment and sustained for up to 72 hr. Aβ1–40 also downregulates bcl-2 protein levels, but the effect is gradual, and a significant difference with the control Aβ40–1 reverse peptide is observed only at 72 hr.

Fig. 3.

Aβ peptides downregulate bcl-2 protein and upregulate bax protein levels in primary neuron cultures.A, Western blot analysis of one representative experiment of bcl-2, bax, and actin protein levels in neurons treated with Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and Aβ40–1 for 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hr.B, Densitometric quantitation by phosphorimager of bcl-2 protein levels in neuron cultures normalized to levels in 0 hr culture (mean of three independent experiments, ± SEM) shows rapidly decreasing bcl-2 protein levels in Aβ1–42(p < 0.01, from 6–72 hr) and a gradual decrease in Aβ1–40-treated neurons (p < 0.01, at 72 hr only) compared with Aβ40–1-treated neurons. C, Densitometric quantitation by phosphorimager of bax protein levels in neuron cultures normalized to levels in untreated (0 hr) sister culture (mean of three independent experiments, ± SEM) shows rapidly increasing bax protein levels in Aβ1–42 (p < 0.05, between 24–72 hr) but no difference in Aβ1–40- compared with Aβ40–1-treated neurons.

In contrast to bcl-2 protein levels, bax protein increases three- to fourfold in Aβ1–42-treated neurons compared with Aβ40–1 (Fig. 3C). The increase in bax is apparent at 6 hr and peaks at 24 hr. The Aβ1–40 has no effect on bax levels in neurons.

The results indicate that a 25-fold increase in the level of Aβ1–40 and a 250-fold increase in Aβ1–42are not sufficient to induce significant apoptosis, although some cells in the neuronal culture are clearly more vulnerable than others to the peptides. Downregulation of bcl-2 and upregulation of bax in these Aβ-treated neurons demonstrate that the peptides have an effect on proteins that mediate apoptosis. To determine whether the neurons exposed to Aβ were more vulnerable to an age-dependent secondary insult such as oxidative stress, we first treated the neurons with Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 for 48 hr and then exposed them to low oxidative stress levels, using 0.1 and 1.0 μm H2O2. The Aβ1–40- and Aβ1–42-treated cultures contain 10–20 times more TUNEL-positive cells when treated with 0.1 and 1.0 μm H2O2, whereas these low levels of H2O2 do not increase apoptosis in Aβ40–1-treated neurons (Fig. 4). These levels of oxidative stress also had no effect on untreated neurons that showed results equivalent to those of the control Aβ40–1(not shown).

Fig. 4.

Susceptibility to H2O2 in neurons pretreated with Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42but not Aβ40–1. TUNEL labeling detects increased apoptosis in neurons pretreated for 48 hr with Aβ1–40and Aβ1–42 and then submitted to 0.1 μmH2O2 and 1.0 μmH2O2 for 48 hr. In contrast, sister cultures treated with the control peptide Aβ40–1 do not show increased sensitivity to low levels of oxidative stress. Data represent an average of four experiments.

DISCUSSION

We find that elevated but physiological concentrations of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 are insufficient to initiate significant human neuronal apoptosis in cultures. Nanomolar concentrations of fresh or aged Aβ that are likely to be physiological concentrations do not show neurotoxic effects in most systems, and human neurons have previously been shown to be resistant to micromolar concentrations of Aβ (Mattson et al., 1992; Shearman et al., 1994). Yet, there is considerable evidence that Aβ plays a primary role in Alzheimer’s disease. We find that 100 nmAβ1–42 rapidly decreases bcl-2 protein levels in neurons, whereas it increases bax levels. Interestingly, bcl-2 protein levels are also decreased in 100 nmAβ1–40-treated neurons, but only gradually, and reach Aβ1–42-treated levels by 72 hr, whereas bax levels remain unaffected. In addition, neurons preexposed to either Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42 show increased sensitivity to a mild oxidative stress. Therefore, we propose a novel hypothesis that in Alzheimer’s disease, neuronal degeneration may be caused by Aβ-mediated downregulation of bcl-2 rendering the neurons vulnerable to age-dependent secondary insults such as oxidative stress, decreasing levels of growth factors, or diminished glucose metabolism (Coyle and Puttfarcken, 1993).

Aβ neurotoxicity has been widely investigated in a number of neuronal systems with the use of very high concentrations of the aggregated or fibrillar peptide (1–100 μm). The underlying mechanisms mediating Aβ neurotoxicity are attributed to either oxidative stress (Behl et al., 1994; Thomas et al., 1996) or the destabilization of intracellular calcium levels (Mattson et al., 1992). Our observations are consistent with both mechanisms. Bcl-2 is well established as an anti-death protein in neurons. Bcl-2 can avert survival factor deprivation-induced neuronal apoptosis in sympathetic cervical ganglia, in sensory primary neurons, and in continuous cell lines such as PC12 cells (Garcia et al., 1992; Batistatou et al., 1993;Mah et al., 1993; Martinou et al., 1994). Bcl-2 and another neuronal bcl-2-related anti-death protein, bcl-xL, also prevent hypoxia and axotomy-induced neuronal death in vivo (Dubois-Dauphin et al., 1994; Jacobson and Raff, 1995; Shimizu et al., 1995). Therefore, bcl-2 and related anti-death proteins are key regulators of programmed cell death in neurons. Any disruption in the level of these proteins is likely to result in increased neuronal vulnerability. The exact mechanism by which downregulation of bcl-2 enhances neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress is not clear. Although it has been proposed by some that bcl-2 directly protects cells against reactive oxygen species (Hockenbery et al., 1993; Kane et al., 1993; Veis et al., 1993), others find that bcl-2 protects cells without decreasing reactive oxygen species (Jacobson and Raff, 1995; Shimizu et al., 1995). On the other hand, it has been shown that in human neurons Aβ enhances excitotoxicity, and this effect is attributed to increased intracellular calcium (Mattson et al., 1992). Increased calcium levels are also linked to apoptosis, and it has been suggested that bcl-2 is involved in the maintenance of cellular calcium homeostasis (Bafy et al., 1993). Downregulation of bcl-2 in human neurons may explain the dysregulation of intracellular calcium levels by Aβ. Our results show that the effect of Aβ1–42 on bcl-2 and bax levels is more drastic than that of Aβ1–40. These results are consistent with the higher aggregative potential of Aβ1–42 (Jarrett et al., 1993) and the aggregation-dependent neurotoxicity of Aβ peptides (Pike et al., 1993).

On the basis of the low levels of neurotoxicity in our human primary cultures exposed to high physiological concentrations of Aβ and the fact that familial AD is manifestly a disease of the aged, we propose that Aβ by itself is unlikely to induce apoptosis in AD patients and that it requires a second age-dependent factor to be neurotoxic. Our data suggest the possibility that downregulation of bcl-2 in the presence of Aβ renders the cell vulnerable to age-dependent stress. Although there is no overwhelming evidence for apoptotic neurons in AD brains, there are indications that such a mechanism can occur. Bcl-2 immunoreactivity generally is increased in AD neurons but decreased in degenerating neurons (Satou et al., 1995). Other evidence of apoptosis in AD brains includes increased apopTag and c-jun immunoreactivity, evidence of DNA fragmentation, and bcl-2-sensitive apoptosis induced by familial AD mutants of APP (Mullaart et al., 1990; Anderson et al., 1994; Su et al., 1994;Lassmann et al., 1995; Anderson et al., 1996; Yamatsuji et al., 1996). The effect of Aβ on fetal neurons may be criticized as a model for AD, an aging disease. The fact remains that these are the only source of human neurons at this time. The decreased bcl-2 expression observed in degenerating neurons of AD brains (Satou et al., 1995) supports the possibility that the effect of Aβ on bcl-2 levels in fetal neuron cultures is reproduced in vivo in the brain of adult individuals.

In summary, our data show that although 25-fold Aβ1–40 and 250-fold Aβ1–42 concentrations do not cause extensive apoptosis in human neurons, Aβ does alter the anti-apoptotic protective balance by downregulating bcl-2 and upregulating bax protein levels, and it increases the vulnerability of these cells to oxidative stress. The data support the hypothesis that increased Aβ concentrations in AD CSF render the neurons vulnerable to age-dependent stresses such as oxidative stress.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Alzheimer Society of Canada, National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant RO1 NS31700, and the Fond de Recherche en Santé du Québec (A.L.) and Medical Research Council (C.G.).

Correspondence should be addressed to Andréa LeBlanc, Lady Davis Institute, 3755 Ch. Côte Ste-Catherine, Montréal, Québec, Canada H3T 1E2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson AJ, Cummings BJ, Cotman CW. Increased immunoreactivity of jun- and fos-related proteins in Alzheimer’s disease: association with pathology. Exp Neurol. 1994;125:286–295. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson AJ, Su JH, Cotman CW. DNA damage and apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease: colocalization with c-jun immunoreactivity, relationship to brain area, and effect of postmortem delay. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1710–1719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01710.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bafy G, Miyashita J, Williamson J, Reed J. Apoptosis induced by withdrawal of interleukin-3 (IL-3)-dependent hemapoeitic cell line is associated with repartitioning of intracellular calcium and is blocked by enforced Bcl-2 oncoprotein production. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6511–6519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batistatou A, Merry DE, Korsmeyer SJ, Greene LA. Bcl-2 affects survival but not neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells. J Neurosci. 1993;13:4422–4428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-10-04422.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behl C, Davis J, Lesley R, Schubert D. Hydrogen peroxide mediates amyloid β protein toxicity. Cell. 1994;77:817–827. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busciglio J, Lorenzo A, Yeh J, Yankner BA. β-amyloid fibrils induce tau phosphorylation and loss of microtubule binding. Neuron. 1995;14:879–888. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai X, Golde T, Younkin S. Release of excess amyloid β protein from a mutant amyloid β protein precursor. Science. 1993;259:514–516. doi: 10.1126/science.8424174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Citron M, Oltersdorf T, Haass C, McConlogue L, Hung A, Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Lieberburg I, Selkoe D. Mutation of the β-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer’s disease increases β-amyloid protein production. Nature. 1992;360:672–679. doi: 10.1038/360672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Citron M, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Teplow D, Miller C, Schenk D, Johnston J, Winblad B, Venizelos N, Lannfelt L, Selkoe D. Excessive production of amyloid β-protein by peripheral cells of symptomatic and presymptomatic patients carrying the Swedish familial Alzheimer disease mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11993–11997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyle JT, Puttfarcken P. Oxidative stress, glutamate, and neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 1993;262:689–695. doi: 10.1126/science.7901908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubois-Dauphin M, Frankowski H, Tsujimoto Y, Huarte J. Neonatal motorneuron overexpressing the bcl-2 protooncogene in transgenic mice are protected from axotomy-induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3309–3313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forloni G, Chiesa R, Smiroldo S, Verga L, Salmona M, Tagliavini F, Angeretti N. Apoptosis mediated neurotoxicity induced by chronic application of β amyloid fragment 25–35. NeuroReport. 1993;4:523–526. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199305000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Games D, Adams D, Alessandrini R, Barbour R, Berthelette P, Blackwell C, Carr T, Clemens J, Donaldson T, Gillespie F, Guido T, Hagopian S, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, Lee M, Leibowitz P, Lieberburg I, Little S, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Montoya-Zavala M, Mucke L, Paganini L, Penniman E, Power M, Schenk D, Seubert P, Snyder B, Soriano F, Tan H, Vitale J, Wadsworth S, Wolozin B, Zhao J. Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F β-amyloid protein. Nature. 1995;373:523–527. doi: 10.1038/373523a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia I, Martinou I, Tsujimoto Y, Martinou J. Prevention of programmed cell death of sympathetic neurons by the bcl-2 proto-oncogene. Science. 1992;258:302–304. doi: 10.1126/science.1411528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haass C, Hung A, Selkoe D, Teplow D. Mutations associated with a locus for familial Alzheimer’s disease result in alternative processing of amyloid β-protein precursor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17741–17748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins LS, Rodems JM, Catalano R, Cordell B. Early Alzheimer disease-like histopathology increases in frequency with age in mice transgenic for β-APP751. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4402–4406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hockenbery DM, Oltvai ZN, Yin X-M, Milliman C, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell. 1993;75:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsiao K, Borcheldt D, Olson K, Johannsdottir R, Kitt C, Yunis W, Xu S, Eckman C, Younkin S, Price D, Iadecola C, Clark B, Carlson G. Age-related CNS disorder and early death in transgenic FVB/N mice overexpressing Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein. Neuron. 1995;15:1203–1208. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwatsubo T, Okada A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in senile plaques with end-specific Aβ monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ42(43). Neuron. 1994;13:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson MD, Raff M. Programmed cell death and bcl-2 protection in very low oxygen. Nature. 1995;374:814–816. doi: 10.1038/374814a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarrett J, Berger E, Lansbury P. The carboxy terminus of the β-amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4693–4697. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kane DJ, Sarafian TA, Anton R, Hahn H, Gralla E, Valentine JS, Ord T, Bredesen DE. Bcl-2 inhibition of neural cell death: decreased generation of reactive oxygen species. Science. 1993;262:1274–1277. doi: 10.1126/science.8235659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo YM, Emmerling MR, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Kasunic TC, Kirkpatrick JB, Murdoch GH, Ball MJ, Roher AE. Water-soluble Aβ (N-40, N-42) oligomers in normal and Alzheimer disease brains. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4077–4081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaFerla FM, Tinkle BT, Bieberich CJ, Haudenschild CC, Jay G. The Alzheimer’s Aβ peptide induces neurodegeneration and apoptotic cell death in transgenic mice. Nature Genet. 1995;9:21–30. doi: 10.1038/ng0195-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lassmann H, Bancher C, Breitschopf H, Wegiel J, Bobinski M, Jellinger K, Wisniewski H. Cell death in Alzheimer’s disease evaluated by DNA fragmentation in situ. Acta Neuropathol. 1995;89:35–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00294257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LeBlanc AC. Increased production of 4 kDa amyloid β peptide in serum-deprived human primary neuron cultures: possible involvement of apoptosis. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7837–7846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-07837.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy-Lahad E, Wasco W, Poorkej P, Romano DM, Oshima J, Pettingell WH, Yu C, Jondro P, Schmidt S, Wang K, Crowley A, Fu Y, Guenette S, Galas D, Nemens E, Wijsman E, Bird T, Schellenberg G, Tanzi R. Candidate gene for the chromosome 1 familial Alzheimer’s Disease locus. Science. 1995;269:973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.7638622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loo D, Copani A, Pike CJ, Whittemore E, Walencewicz AJ, Cotman CW. Apoptosis is induced by β-amyloid in cultured central nervous system neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7951–7955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mah SP, Zhong LT, Liu Y, Roghani A, Edwards RH, Bredesen DE. The protooncogene bcl-2 inhibits apoptosis in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 1993;60:1183–1186. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinou J-C, Dubois-Dauphin M, Staple JK, Rodriguez I, Frankowski H, Missotten M, Albertini P, Talabot D, Catsicas S, Pietra C, Huarte J. Overexpression of bcl-2 in transgenic mice protects neurons from naturally occurring cell death and experimental ischemia. Neuron. 1994;13:1017–1030. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mattson MP, Cheng B, Davis D, Bryant K, Lieberburg I, Rydel RE. β-amyloid peptides destabilize calcium homeostasis and render human cortical neurons vulnerable to excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1992;12:376–389. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00376.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meda L, Cassatella M, Szendrei G, Otvos L, Baron P, Villalba M, Ferrari D, Rossi F. Activation of microglial cells by β-amyloid protein and interferon-gamma. Nature. 1995;374:647–650. doi: 10.1038/374647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullaart E, Boerrigter M, Ravid R, Swabb D, Vijg J. Increased levels of DNA breaks in cerebral cortex of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neurobiol Aging. 1990;11:169–173. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(90)90542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munsick RA. Human foetal extremity lengths in the interval from 9 to 21 menstrual weeks of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;149:883–887. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90609-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura T, Shoji M, Harigaya Y, Watanabe M, Hosoda K, Cheung T, Shaffer L, Golde T, Younkin L, Younkin S, Hirai S. Amyloid β protein levels in cerebrovascular fluid are elevated in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:903–911. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pike CJ, Burdick D, Walencewicz AJ, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. Neurodegeneration induced by β-amyloid peptides in vitro: the role of peptide assembly state. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1676–1687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01676.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Querfurt HW, Wisjsman EM, St. George Hyslop P, Selkoe D. βAPP mRNA transcription is increased in cultured fibroblasts from the familial Alzheimer’s disease-1 family. Mol Brain Res. 1995;28:319–337. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rabizadeh A, Bitler CM, Butcher LL, Bredesen DE. Expression of the low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor enhances β-amyloid peptide toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10703–10706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Satou T, Cummings BJ, Cotman CW. Immunoreactivity for bcl-2 protein within neurons in the Alzheimer’s disease brain increases with disease severity. Brain Res. 1995;697:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00748-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shearman M, Ragan C, Iversen L. Inhibition of PC12 cell redox activity is a specific, early indicator of the mechanism of β-amyloid-mediated cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1470–1474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherrington R, Rogaev EJ, Liang Y, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Chi H, Lin C, Li G, Holman K, Tauda T, Mar L, Foncin J-F, Bruni AC, Montreal MP, Sorbi S, Rainero I, Pinessi L, Nee L, Chumakov I, Pollen D, Brookes A, Sanseau P, Pollinsky RJ, Wasco W, Da Silva HAR, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Tanzi RE, Roses AD, Fraser P, Rommens JM, St. George-Hyslop PH. Cloning of a gene bearing mis-sense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1995;375:754–760. doi: 10.1038/375754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, Song X, Citron M, Suzuki N, Bird T, Hardy J, Hutton M, Kukull W, Larson E, Levy-Lahad E, Viitanen M, Peskind E, Poorkaj P, Schellenberg G, Tanzi R, Wasco W, Lannfelt L, Selkoe D, Younkin S. Secreted amyloid β-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 1996;2:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimizu S, Eguchi Y, Kosaka H, Kamlike W, Matsuda H, Tsujimoto Y. Prevention of hypoxia-induced cell death by bcl-2 and bcl-xL. Nature. 1995;374:811–813. doi: 10.1038/374811a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su J, Anderson A, Cummings B, Cotman C. Immunohistochemical evidence for apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroReport. 1994;5:2529–2533. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki N, Cheung T, Cai D, Odaka A, Laslo O, Eckman C, Golde T, Younkin S. An increased percentage of long amyloid β protein secreted by familial amyloid β protein precursor (βAPP117) mutants. Science. 1994;264:1336–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.8191290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanzi R, Gusella J, Watkins P, Bruns G, St. George-Hyslop P, Van Keuren M, Patterson D, Pagan S, Kurnit D, Neve R. Amyloid β protein gene: cDNA, mRNA distribution, and genetic linkage near the Alzheimer locus. Science. 1987;235:880–884. doi: 10.1126/science.2949367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teller JK, Russo C, DeBusk LM, Angelini G, Zaccheo D, Dagna-Bricarelli F, Scartezinni P, Bertolini S, Mann DMA, Tabaton M, Gambetti P. Presence of soluble β-amyloid peptide precedes amyloid plaque formation in Down’s syndrome. Nat Med. 1996;2:93–95. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas T, Thomas G, McLendon C, Sutton T, Mullan M. β-amyloid-mediated vasoactivity and vascular endothelial damage. Nature. 1996;380:168–171. doi: 10.1038/380168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Gool WA, Schenk DB, Bolhuis PA. Concentrations of amyloid-β peptide in cerebrospinal fluid increase with age in patients free from neurodegenerative disease. Neurosci Lett. 1994;172:122–124. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90677-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veis DJ, Sorenson CM, Shutter JR, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2-deficient mice demonstrate fulminant lymphoid apoptosis, polycystic kidneys, and hypopigmented hair. Cell. 1993;75:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80065-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watt JA, Pike CJ, Walencewicz AJ, Cotman CW. Ultrastructural analysis of β-amyloid-induced apoptosis in cultured hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 1994;661:147–156. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wisniewski K, Wisniewski H, Wen G. Occurrence of neuropathological changes and dementia of Alzheimer’s disease in Down’s syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1985;17:278. doi: 10.1002/ana.410170310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamatsuji T, Okamoto T, Takeda S, Murayama Y, Tanaka N, Nishimoto I. Expression of V642 APP mutant causes cellular apoptosis as Alzheimer trait-linked phenotype. EMBO J. 1996;15:498–509. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yankner BA, Duffy LK, Kirschner DA. Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid β protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides. Science. 1990;250:279–286. doi: 10.1126/science.2218531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]