Abstract

The synapses made by many arthropod photoreceptors are disinhibitory and use histamine as their transmitter. Because decreases and not increases in the cleft concentration of transmitter constitute the important event at these synapses, a transporter to clear the cleft of histamine would seem particularly crucial to signal transfer. We report here that 3H-histamine is taken up selectively into barnacle photoreceptors by a Na+-dependent mechanism, presumably a transporter. Using light microscopic autoradiography, we observe heavy label over axons and presynaptic terminals of these neurons when they are stimulated during uptake. The radioactivity taken up was identified as 3H-histamine by thin layer chromatography; no metabolites were detected, even after 5 hr. Radiolabeled 5-hydroxytryptamine and GABA are not taken up by the photoreceptor.3H-histamine uptake into photoreceptors is decreased markedly by an excess of unlabeled histamine and by chlorpromazine and phenoxybenzamine. Unexpectedly for uptake dependent on the Na+ gradient, photoreceptor terminals label more intensely in the light (when depolarized) than in the dark (when hyperpolarized). Glia label more strongly than photoreceptors in dark-incubated preparations. The presence of presynaptic uptake strengthens the evidence that histamine is the neurotransmitter of arthropod photoreceptors and provides a mechanism by which this synapse could recycle transmitter, control its steady-state cleft concentration, and clear it from the cleft in response to decreases in its release from the photoreceptors.

Keywords: histamine, photoreceptor, arthropod, transporter, barnacle, autoradiography, neurotransmitter, synapse, disinhibition

Disinhibition is a common synaptic mechanism in retinas of both vertebrates and invertebrates. In arthropod simple and compound eyes, disinhibition of postsynaptic cells at the photoreceptor synapses converts presynaptic hyperpolarizations to postsynaptic depolarizing synaptic potentials. In steady light, the photoreceptors are depolarized and continuously release inhibitory transmitter, holding the postsynaptic cell silent. Dimming of the light hyperpolarizes the photoreceptor but excites the postsynaptic cell through disinhibition. At such synapses where decreases in concentration of transmitter in the cleft constitute the meaningful signal, the mechanisms of transmitter removal from the cleft might be expected to assume pivotal importance in the generation of the postsynaptic response.

Here we present autoradiographic and biochemical evidence for selective uptake into an arthropod photoreceptor of histamine, the probable neurotransmitter of many, perhaps all, arthropod photoreceptors (Hardie, 1987, 1988, 1989; Simmons and Hardie, 1988; Battelle et al., 1991; Stuart and Callaway, 1991; Burg et al., 1993; Schmid and Duncker, 1993). Uptake is Na+-dependent, suggesting that this putative histamine transporter belongs to one of the families of Na+-dependent transporters. All domains of the cell took up 3H-histamine, although when the cells were stimulated, uptake was markedly greater in the presynaptic terminals and axons than in the somata and dendrites. Unexpectedly, the terminals of photoreceptors incubated in the light labeled more heavily than those of photoreceptors incubated in the dark, where label was found over glia instead.

Some of these results have been published previously in abstract (Stuart and Mekeel, 1990; Stuart et al., 1993; Morgan and Stuart, 1995).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and preparations. Giant barnacles (Balanus nubilus) were obtained from Bio-Marine Enterprises (Seattle, WA) and maintained at 11°C in aerated, circulating artificial seawater. Preparations were dissected as described inHudspeth and Stuart (1977) in barnacle saline containing (in mm): 461.5 NaCl, 8 KCl, 20 CaCl2, 12 MgCl2, and 10 Tris(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane HCl buffer, pH 7.6–7.8.

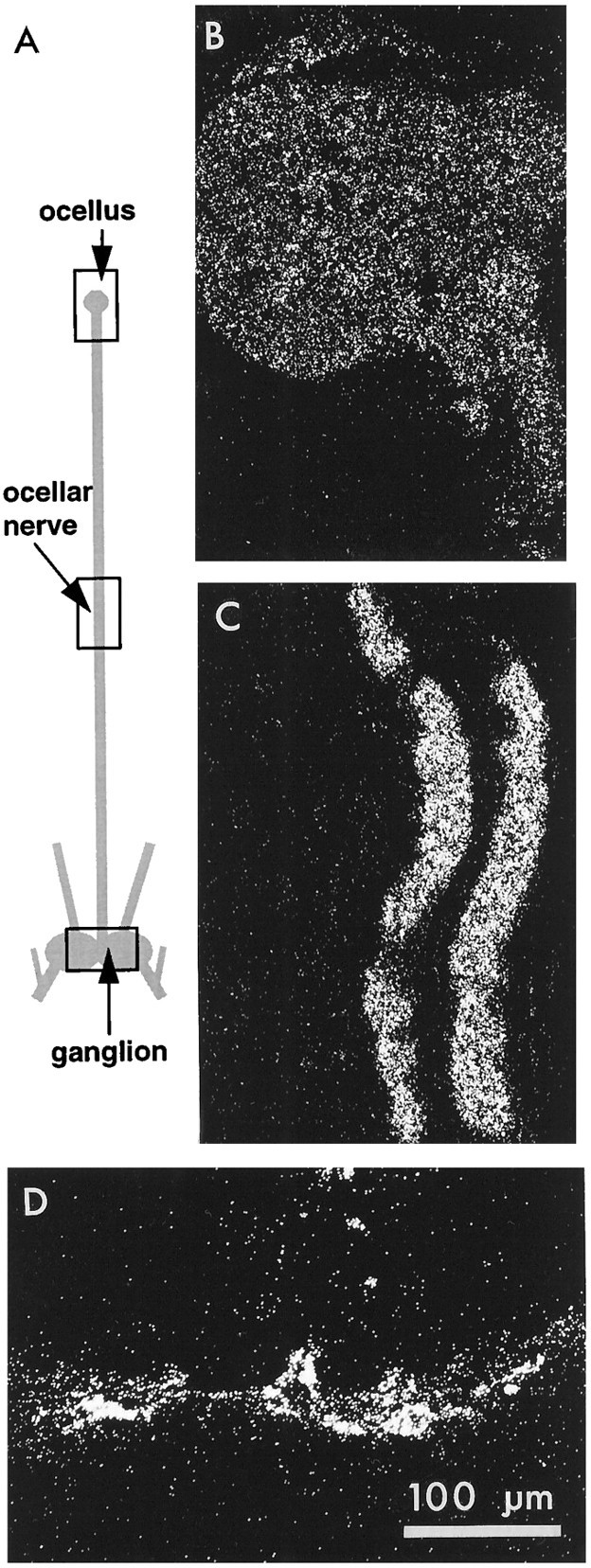

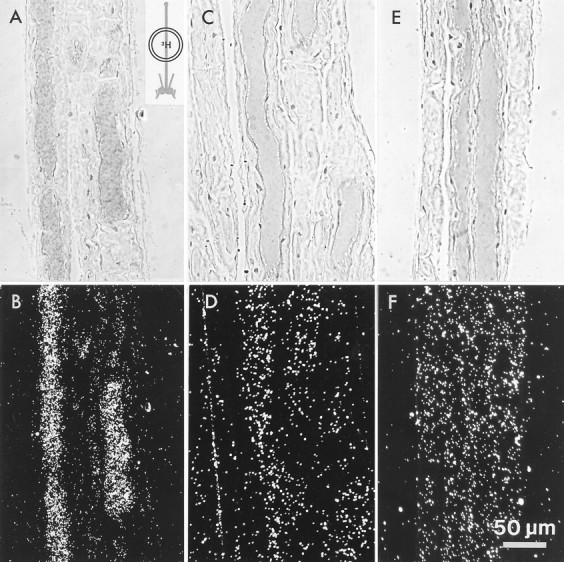

Preparations consisted of the median eye (ocellus), comprising four photoreceptor somata, the median ocellar nerve containing their axons, and the small supraesophageal ganglion, or “brain,” where these photoreceptors terminate (see Fig. 2A). Two other simple eyes positioned laterally in the animal each contain three photoreceptors that normally project through the antennular nerves to terminate in the ganglion; these nerves (and thus the lateral photoreceptor axons) were severed.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of uptake in intact photoreceptors when the whole preparation was incubated in3H-histamine. A, Diagram of the preparation (not drawn to scale) showing the median ocellus, ocellar nerve, and ganglion to which it projects. Sections through the regions indicated by the rectangles are shown in dark-field illumination on the right. B, The ocellus, which shows a uniform and light accumulation of silver grains.C, The nerve. This section cuts through two photoreceptor axons that are labeled more heavily than ocellar structures. Other axons in the nerve are not labeled. D, The portion of the ganglion containing the photoreceptor synaptic terminals, which are also heavily labeled. Scale bar applies to B, C, D.

Incubations.3H-histamine dihydrochloride (36–57 Ci/mmol; Amersham) was divided into 20 μl aliquots, and for each experiment an aliquot was dried down to remove ethanol and redissolved in barnacle saline to a concentration of 20 μm, pH 7.3. Preparations were pinned on Sylgard (Dow-Corning), in either small petri dishes or a three-compartment Plexiglas chamber. For preparations in the petri dish, a Vaseline well was constructed around the ocellus (containing the somata and dendrites of the photoreceptors), around the midportion of the ocellar nerve (containing their axons), or around the ganglion (containing their presynaptic terminals); when the Plexiglas chamber was used, the preparation was arranged so that ocellus, nerve, and ganglion were in the separate compartments isolated by Vaseline walls. The saline within the well or one of the compartments was replaced with saline (20 μl) containing the 20 μm3H-histamine, leaving the rest of the preparation in normal saline outside the well. The fluid level within the well or compartment was watched carefully to ensure that it did not decrease during the incubation, which would have indicated a leak in the Vaseline wall; in some cases aliquots were taken of the fluid outside the well to check for leaking radioactivity. Incubations in the3H-histamine were for 15 min at 15°C in constant light of moderate intensity (0.13 mW/cm2), flashing light of the same intensity (2 sec on/6 sec off), or dark. When the incubation saline was to contain a drug or altered ionic composition, the saline within the well was exchanged for experimental saline for 15–30 min before the3H-histamine was introduced.

For Na+-free incubations, it was important to superfuse the axons or terminals continuously for a period of 30 min to wash completely the Na+ from the extracellular space; exchange for a shorter time gave variable results. Na+ was replaced with choline, tetramethylammonium (TMA+),N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMG+), or Li+. For experiments in which physiological activity was monitored during the exposure of axons to Na+-free saline, a preparation in a three-chambered bath was placed on a physiology setup. Each chamber was superfused continuously with saline at a high rate (2–5 ml/min), and visual signals (a burst of activity in third-order ganglion cells at the offset of a light pulse delivered every 20 sec) were monitored throughout the experiment from one of the circumesophageal connective nerves of the supraesophageal ganglion in which the photoreceptors terminate. When3H-histamine was added to the axonal chamber, the perfusion of only that compartment was stopped for the duration of the incubation. After incubations, the 3H-histamine was washed out for 30 min in Na+-free saline.

Reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) except where noted.3H-5-hydroxytryptamine (Amersham or New England Nuclear) was applied at 40 μm (18.2 or 24.7 Ci/mmol) for experiments on the ganglion and 20 μm for experiments on the axons and ocellus;3H-GABA (Amersham) was applied at 20 μm (51.6 or 86 Ci/mmol). Drugs included phenoxybenzamine and cocaine (generous gifts of Dr. Richard Mailman), chlorpromazine, and desipramine.

After the incubation, the solution in the Vaseline well (capacity, 20 μl) was exchanged quickly with several volumes of either normal saline or, especially when the presynaptic terminals were incubated, a saline containing Co2+ (12.5 mm) and low Ca2+ (2.5 mm) to minimize release of the3H-histamine taken up. This concentration of Co2+ and Ca2+ has been shown to reduce the postsynaptic response to near zero (J. C. Callaway and A. E. Stuart, unpublished observations). The preparation was then immersed in the Co2+/low Ca2+ saline and transferred on its Sylgard platform to a chamber made from a 5 ml syringe in which it was washed with chilled Co2+/low Ca2+saline for 15–20 min (2–3 ml/min). Fifteen minutes after the beginning of the wash, <1% of the radioactivity collected during the first minute remained in the ganglion. Axons incubated in3H-histamine in Na+-free saline were washed after incubation with a Na+-free saline for 30 min at 5 ml/min.

For preparations incubated in the dark, all manipulations were carried out in total darkness until the incubation was terminated and the preparation had been washed for at least 5 min in Co2+-containing saline.

Autoradiography. Glutaraldehyde (E. M. Sciences) fixative was modified from Hudspeth and Stuart (1977) to contain 0.2 m Na+ cacodylate, pH 7.7, instead of phosphate buffer. Preparations were fixed for times ranging from 1 hr to overnight, washed several times with cacodylate buffer on a tissue rotator, postfixed in osmium tetroxide (1%) in cacodylate buffer (1 hr, room temperature), washed several times in distilled water, and dehydrated. Preparations were cut into pieces at this point so that the ocellus, median portion of the ocellar nerve, and ganglion could be embedded separately in Epon.

Blocks were sectioned serially at 2 μm. Sections were dried on gelatin-coated slides, dipped in Kodak NTB-2 autoradiographic emulsion, exposed at 4°C for 5 d to 2 weeks, and developed in D-19 (Kodak).

Assay of 3H-histamine uptake by scintillation counting. Preparations were incubated in 100 μl of 20 μm3H-histamine for 15 min at 15°C in Eppendorf tubes in flashing light. When appropriate, preparations were preincubated with drug for 15 min in the dark at 15°C. After incubation, preparations were washed with 5 vol of a 12.5 mm Co2+/2.5 mmCa2+ saline. One hundred microliters of 6% trichloroacetic acid were added to each preparation, which then sat overnight at 4°C. Each preparation was then ground in a glass/glass homogenizer in a final volume of 120 μl. Aliquots of the homogenate were counted in Biofluor scintillate. Protein was determined from the remainder of each sample using a Micro BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Thin layer chromatography. Preparations were incubated in3H-histamine for 2–5 hr in flashing light at 15°C. After incubation, the preparations were washed for 20 min in room light with saline solution containing Co2+(12.5 mm) and low Ca2+ (2.5 mm). The nerves were severed, the ocellus was discarded, and the washed ganglia were homogenized in 50 μl of a mixture of 1 m formic acid and acetone (15:85). The extract was chromatographed on Polygram SIL G sheets (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) in solvent systems of chloroform/methanol/ammonium in proportions of 12:7:1 or 2:2:1 (Weinreich et al., 1979; Elias and Evans, 1983). The unlabeled metabolites, imidazole acetic acid (Sigma), N-acetyl histamine (Sigma), N-telemethylhistamine (gift of Merck, Sharpe and Dohme) and γ-glutamylhistamine (kindly provided by Dr. D. Weinreich), were added at a concentration of 1–2 mg/ml to samples before chromatography and were visualized using a sulfanilic acid stain (Elias and Evans, 1983) or 0.2% ninhydrin in acetone. After chromatography, each lane was cut into 0.5 cm sections, eluted in 100 μl 0.1 m HCl, and counted in Scintiverse BD (Fisher). All solvents were HPLC grade from Fisher.

RESULTS

Photoreceptor terminals take up 3H-histamine

The ganglia of 19 preparations containing the presynaptic terminals of the photoreceptors were incubated in3H-histamine (20 μm). Ganglia were ringed with Vaseline and incubated for 15 min at 15°C, during which time the preparations were stimulated either with flashing light (standard conditions) or, for several preparations, with steady light. Subsequent autoradiography showed that in all of these preparations, label was highly localized within the ganglion to the terminal regions of the photoreceptors, including their axons and their entire presynaptic arbors (Fig.1A–C).

Fig. 1.

Labeling of photoreceptor terminal arbors after incubation in 3H-histamine (A–E),3H-5HT (F, G), or3H-GABA (H) in the light.A, Horizontal section of the ganglion as seen with phase-contrast illumination. Silver grains crisply delineate photoreceptor axons (fat arrows), primary processes, and bilaterally symmetrical terminal arborizations in the anterior portion of the commissure linking the two hemiganglia. The concentration of3H-histamine was 20 μm in this and all other incubations involving3H-histamine. B, Dark-field illumination of the same section. Scale bar in A applies also to B. C, A section from another preparation photographed with phase-contrast illumination. The axons in the median ocellar nerve (arrows) are particularly prominent in this preparation. Both preparations were incubated in the constant light. Sections were 2 μm and were exposed to emulsion for 2 weeks.D, Bright-field view of section through a preparation incubated in 2 mm unlabeled histamine and 20 μm3H-histamine. No accumulation of silver grains is apparent over the photoreceptor axons or primary processes (arrows) or photoreceptor terminals in the ganglion. The lack of silver grains over this and all the other serial sections of this preparation is consistent with the unlabeled histamine outcompeting 3H-histamine for uptake. E, Dark-field view of the section inD. F, Bright-field view of a preparation incubated in 3H-5HT. The label is absent from photoreceptors and glia but is associated with a fragment of axon (arrows) and varicosities in the neuropil. G, Dark-field view of the section in F. H, Section through the nerve as it enters the ganglion from a preparation incubated in 3H-GABA viewed in dark-field illumination. Silver grains are found over glia but are conspicuously lacking over the bifurcating photoreceptor axons. Anterior is up in all panels.

Figure 1A,B shows phase-contrast and dark-field views, respectively, of a horizontal section taken at the level of the photoreceptor terminals through the ganglion of a preparation that had been incubated in 3H-histamine and steady light. The section has the location and approximate dimensions of the rectangle drawn on the ganglion in the diagram of Figure2A. Each photoreceptor axon bifurcates at a variable position in the nerve as it enters the midline of the commissure linking the two hemiganglia (Hudspeth and Stuart, 1977, their Fig. 6) and then arborizes bilaterally close to the midline; this section passes through the heart of the arbors of these cells. Silver grains distinctly outline the arbors in their entirety, including the axons as they enter the ganglion, their primary branches, and their rather abrupt, bushy terminals (Schnapp and Stuart, 1983; Stockbridge and Ross, 1984; Oland and Stuart, 1986; Callaway et al., 1989; Callaway et al., 1993). The presence of grains over the entering axons (arrows in Fig. 1A) was unexpected but repeatable; longer portions of the axons of the entering photoreceptors in a section from another preparation show clearly their marked labeling (arrows in Fig. 1C).

Fig. 6.

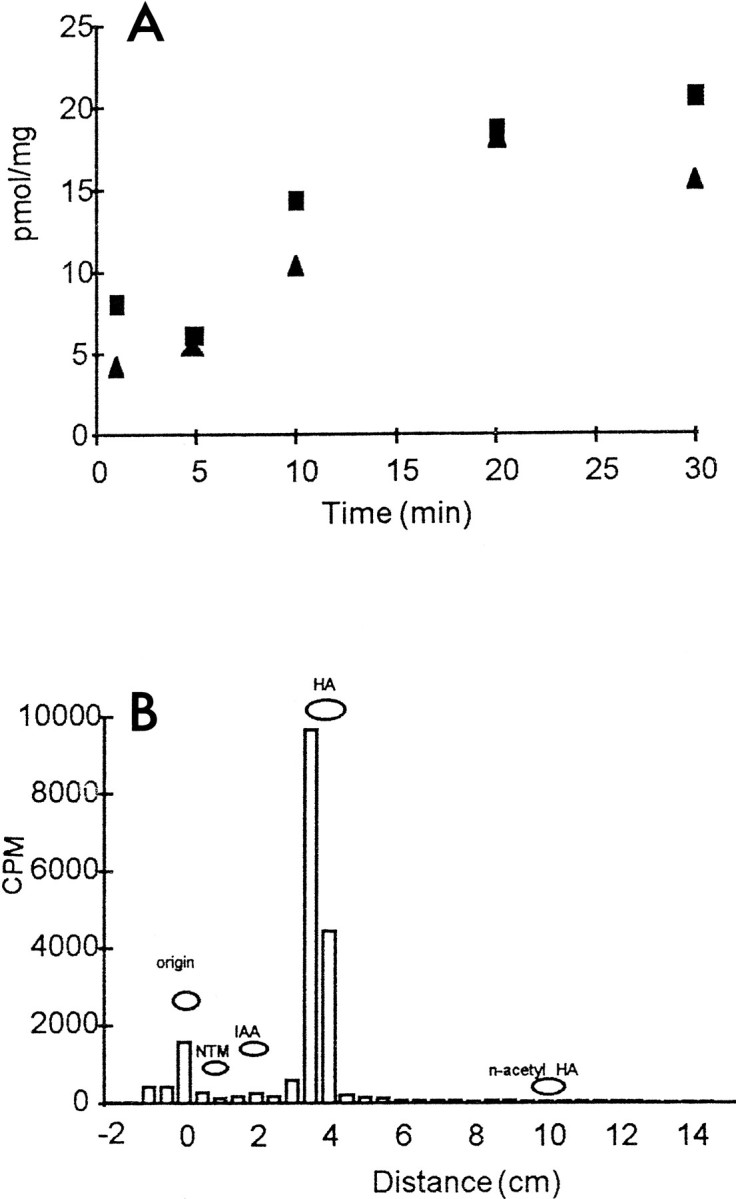

Time course and metabolism of3H-histamine taken up by the preparation.A, Time course of uptake. Whole preparations were incubated in 3H-histamine for the time indicated, each point representing a separate preparation. Squares andtriangles indicate preparations made on 2 different days.B, Thin layer chromatograph showing radiolabeled compounds present in a preparation after 2 hr of incubation in3H-histamine (20 μm; standard conditions). A large peak of radioactivity was associated with the histamine standard (HA). No substantial peaks were seen at the positions of major metabolites: imidazolacetic acid (IAA), N-acetylhistamine (n-acetyl HA), or N-telemethylhistamine (NTM). Compounds were extracted from preparations with 1 m formic acid/acetone (15:85), and separated using a 12:7:1 chloroform/methanol/ammonia solvent system.

The section shown in Figure 1A,B is from a serial set of 126 sections through the ganglion, in which 25 sections near the center of the set (sections 29 through 53) showed silver grains in the expected position of the photoreceptor terminals. The primary processes and final arbors extend in this preparation ∼100–150 μm into each hemiganglion, in agreement with previous measurements from horseradish peroxidase-filled cells (Schnapp and Stuart, 1983). In a second preparation (Fig. 1C), terminals appeared in 23 of 71 serial sections that were cut. Thus, the terminal arbors occupied about the same vertical dimension in the two ganglia (46–50 μm) and were present in a substantial fraction of the serial sections.

At lower magnification, it was possible to see that grains were distributed evenly within the main body of the ganglion (not shown), suggesting no substantial accumulation of the3H-histamine either in ganglion cells or in the glia surrounding them. This finding contrasts markedly with the dense pattern of label, presumably glial, seen after incubation in3H-GABA, where the grains spare the ganglion cells and photoreceptors but blacken the areas between them (Fig.1H).

It was a consistent observation that the “background” label over the anterior half of the commissure in which the photoreceptor terminals arborize was greater than that in the posterior half (Fig.1A) or, indeed, than over the rest of the ganglion. This label over the anterior commissure seems to be over the distinctive glial cells that envelope the photoreceptor arbors in this region (Schnapp and Stuart, 1983). Packed, unlabeled axons form the posterior half of the commissure, which is clearly distinct from the anterior half in this phase-contrast view.

The accumulation of 3H-histamine in the axons and terminals of the median photoreceptors was diminished markedly in each of two preparations by 2 mm unlabeled histamine added to the incubation medium (Fig. 1D,E), an observation consistent with uptake being a competitive process, presumably mediated by a transporter protein.

3H-5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT) and3H-GABA are not taken up by photoreceptor terminals

Two ganglia incubated in 3H-5HT (40 μm) and flashing light did not show an accumulation of grains over photoreceptor terminal arbors. Rather, these preparations accumulated silver grains over a decussating ganglion cell axon (Fig. 1F,G, fat arrows) in the same region as the unlabeled photoreceptor terminals, over varicosities in the neuropil, and over several small cell bodies (not in the section of Fig. 1F,G) in the pattern observed by Callaway et al. (1985) using immunolabeling. Thus, the uptake of 3H-histamine into the photoreceptors is highly selective for histamine over 5HT.

Two ganglia incubated in 3H-GABA (20 μm) labeled widely and diffusely, presumably attributable to uptake of this compound into glial cells. There was no label over photoreceptor terminal arbors, axons (Fig. 1H, dark, unlabeled, elongated profiles in the nerve), or other neurons. Curiously, GABA antiserum labels barnacle photoreceptor somata and axons and (less intensely) their presynaptic arbors (Callaway et al., 1989). Strong arguments, however, previously have disqualified GABA as the transmitter causing the postsynaptic response (Callaway and Stuart, 1989a) and now include the absence of 3H-GABA uptake into the terminals.

Distribution of 3H-histamine along the photoreceptor neuron

Incubation of whole preparations (n = 3) in3H-histamine in flashing light, and subsequent autoradiography of their ocelli, axons, and terminals (Fig. 2) confirmed that label appeared not only over the terminals of the photoreceptors (Fig. 2D) but also over their axons in the nerve (two axons captured in Fig. 2C). Other, smaller axons in the nerve, not belonging to photoreceptor neurons, did not label. Ocellar structures (Fig. 2B) labeled at a density above that in the surrounding capsule, but the label was apparently uniform and far less dense than in the axons. In fact, a gradient of label seems to exist in the preparation of Figure 2, with the terminals most intensely labeled, but because the axons were sampled only at their midpoint and not at other positions along their length, it was not possible to know from these experiments whether the entire cell labeled as a gradient or as three discrete domains of intensity.

Photoreceptor axons take up 3H-histamine

From the experiments illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, we did not know whether the 3H-histamine was being accumulated actively by the axons of the photoreceptors or whether it was diffusing or being retrogradely transported into the axons from the terminals. To determine whether the axons of the photoreceptors themselves could take up3H-histamine, only the middle portion of the nerve was incubated in the labeled compound (Fig. 3,inset diagram; n = 5). The ganglion and ocellus were bathed in unlabeled histamine (1 mm) to prevent uptake at these sites of 3H-histamine that might have leaked out of the axonal compartment or diffused along extracellular pathways. Subsequent autoradiography and examination with phase-contrast and dark-field optics (Fig. 3A,B) showed heavy label over the photoreceptor axons in the nerve. Figure3A, focused on the tissue, shows the large size of the photoreceptor axons in relation to the diameter of the nerve. Other smaller axons and structures within the nerve do not accumulate grains above the background density seen over the connective tissue capsule that surrounds the nerve and ganglion.

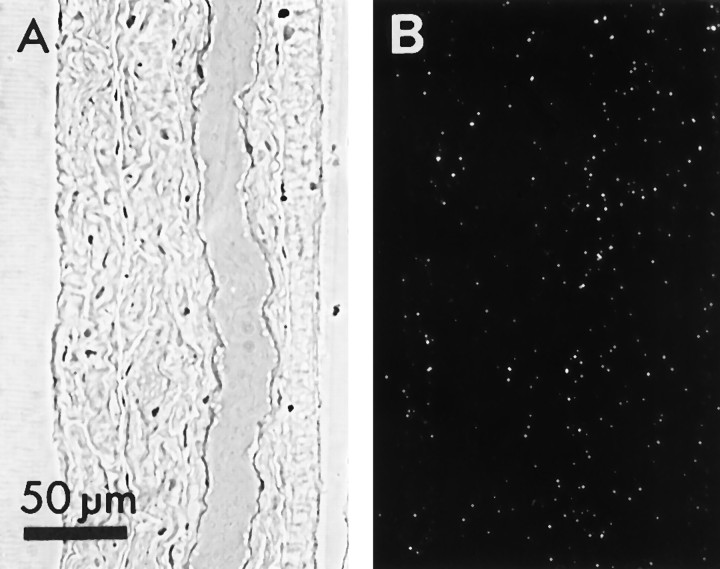

Fig. 3.

Labeling of photoreceptor axons when only the median ocellar nerve was incubated in3H-histamine (inset diagram).A, B, Phase-contrast and dark-field micrographs, respectively, of a section through the median ocellar nerve in which portions of two photoreceptor axons are seen. Only the photoreceptor axons labeled when incubated in 3H-histamine; other structures within the nerve did not accumulate grains above background seen in the surrounding capsule. C, D, Label in the photoreceptor axons is reduced to background level when 1 mm unlabeled histamine is added to the 20 μm3H-histamine.E, F, The photoreceptor axons do not take up3H-5HT. Scale bar shown in F applies to all panels.

Excess (1 mm) unlabeled histamine added to the3H-histamine in the incubation saline blocked the accumulation of grains over the axons (Figs. 3C,D;n = 2). Incubation of the nerve in3H-5HT (20 μm) also resulted in no significant accumulation of silver grains over the photoreceptor axons, or, indeed, over any of the axons in the nerve (Fig. 3E,F; n = 2). Thus uptake of3H-histamine into the photoreceptor axons has characteristics similar to uptake into the presynaptic terminals.

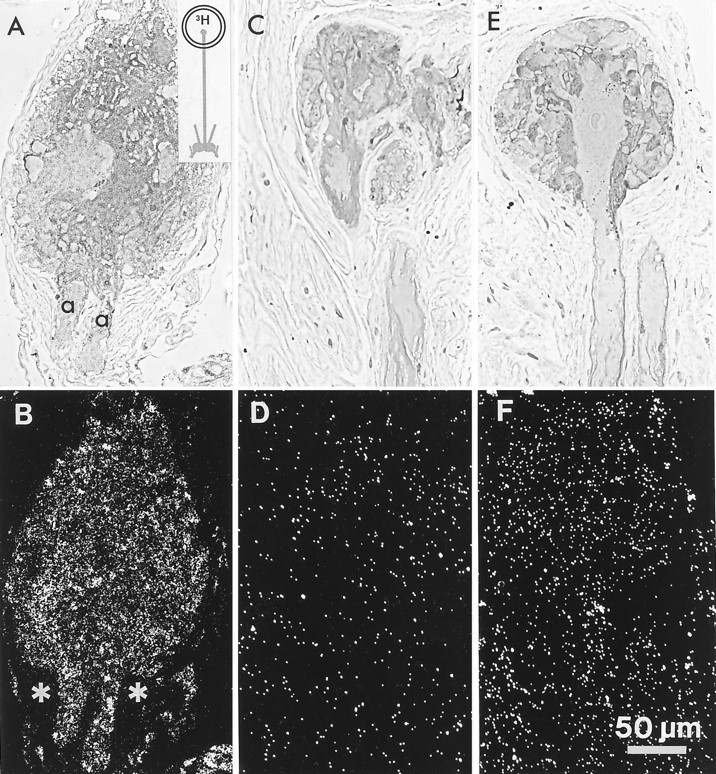

Pattern of 3H-histamine label over ocelli

In contrast to the clear label of terminals and axons, the label over ocelli incubated in 3H-histamine was light and uniform (Fig. 4A,B; n = 8). Structures within the barnacle ocellus include the four photoreceptor somata (one seen exceptionally clearly in the section of Fig.4C), their dendrites and rhabdomeres, and surrounding glial cells, which are intertwined with the dendrites (Fahrenbach, 1965;Hudspeth and Stuart, 1977). Although the accumulation of grains over ocellar structures was denser than the background level in the capsule (asterisks in Fig. 4A, B), there was no pattern to this label suggestive of selective accumulation into either the neuronal or the glial cells.

Fig. 4.

Labeling of the median ocellus after incubation in3H-histamine (inset diagram).A, B, Horizontal section through the median ocellus, showing the axon hillocks (a) of two photoreceptors exiting it. A uniform accumulation of silver grains is seen over ocellar structures at higher density than over surrounding capsule (asterisks in B). C, D, 1 mm unlabeled histamine added to the 20 μm3H-histamine. The uptake of 3H-histamine is reduced to the background level seen over the capsule. E, F, A section through an ocellus incubated in 3H-5HT. The sectioned photoreceptor soma, its dendrites, its axon, and a portion of an axon from a neighboring photoreceptor (soma in another section) clearly do not accumulate grains above the background level. Scale bar in F applies to all panels.

When excess (1 mm) unlabeled histamine was added to the incubation solution, the grains were distributed over the ocellus at background level (Fig. 4C,D; n = 3), suggesting that the uptake observed in the ocellus, although weak, is a competitive process and not simply entrapment of3H-histamine in the extracellular space.

Ocelli incubated in 20 μm3H-5HT (Fig. 4E,F; n = 4) did not show accumulation of grains above background over any ocellar structures. In the phase-contrast micrograph of Figure 4E, one can see clearly a photoreceptor soma, several of its dendrites, and the axon projecting from it that exits the ocellus. The corresponding dark-field view of this section (Fig. 4F) reveals no difference in grain density over these structures, the rest of the ocellus, and the capsule. In contrast, the density of silver grains over the ocellus attributable to the uptake of3H-histamine (Fig. 4A,B) is higher than that over the capsule (asterisks in Fig.4B).

The uptake of 3H-histamine is Na+-dependent

Using autoradiography, we determined whether3H-histamine could be taken up into photoreceptor axons or terminals in the absence of external Na+. Preparations were placed in a three-chamber bath, and the axons were incubated in3H-histamine and saline in which the Na+ had been replaced by choline or TMA+ (terminals and ocellus incubated in normal saline). Axons from all six preparations incubated in Na+-free saline showed no accumulation of silver grains (Fig. 5A,B).

Fig. 5.

Na+-dependence of the uptake of 3H-histamine into axons. A,B, Phase-contrast and dark-field micrographs, respectively, of a section through a median ocellar nerve that was incubated in Na+-free saline (Na+replaced by choline), while its ability to signal normally was verified by recording from postsynaptic cells. The absence of label indicates that uptake of 3H-histamine is a Na+-dependent process. Scale bar in Aalso applies to B.

To be certain that the lack of uptake was not attributable to damage to the axons during prolonged exposure to the Na+-free saline, we monitored the function of the photoreceptors in each experiment. Signals are known to spread along the axons of the photoreceptors in a decremental fashion without action potentials, and they do not require extracellular Na+ (Hudspeth and Stuart, 1977; Hudspeth et al., 1977). Thus it was possible to monitor the health of the axons during incubations by determining whether visual signals continued to spread from the cell soma to the terminals in the Na+-free saline. Because the ganglion cells and the photoreceptor terminals were bathed in normal saline, synaptic transmission from the photoreceptors and the responses of postsynaptic cells were preserved. Extracellular recordings from a nerve containing the axons of ganglion cells in the visual pathway showed no change in the response of these neurons to changes in light intensity during the entire time of exposure of the photoreceptor axons to Na+-free saline (30 min preincubation, 15 min incubation, 30 min wash). We conclude that signals spread normally down the photoreceptor axons in the Na+-free saline and that the absence of uptake into the axons in this saline was unlikely to be attributable to axonal damage. Fourteen ganglia were incubated in salines in which Na+ had been replaced with choline, TMA+, Li+, or NMG+. Labeling was either absent or very weak in all of these ganglia, even after 2 weeks of exposure to emulsion. Control ganglia incubated in Na+-containing saline in these experiments labeled normally. On the basis of the markedly diminished labeling and the absence of label from axons in Na+-free salines, we conclude that uptake in the terminals is Na+-dependent. A low concentration of Na+ remaining in the extracellular space around the ganglion might be expected to drive uptake to some extent, as is the case for the glutamate transporter (Schwartz and Tachibana, 1990).

Assaying uptake of 3H-histamine by scintillation counting

Preparations were incubated in 3H-histamine under standard conditions and assayed separately for uptake using scintillation counting. In 24 preparations (ocellus, median ocellar nerve, and ganglion), the mean accumulation of3H-histamine was 73 ± 43 pmol/mg protein for a 15 min incubation. Including 2 mm unlabeled histamine in the incubation medium reduced uptake by 90%. The time course of the accumulation of the 3H-histamine is shown in Figure 6A. Uptake is roughly linear for the first 15 min and approaches saturation by 30 min.

We determined whether the radioactivity was associated primarily with histamine or with a histamine metabolite. Preparations were incubated in 3H-histamine (20 μm) at 15°C and either flashing light for 2 hr (Fig. 6B) or in the dark for 5 hr. Radioactive compounds in these preparations were then separated by thin layer chromatography.

The dominant compound after either of these periods of incubation was3H-histamine (Fig. 6B). No substantial peaks were seen at the positions of imidazolacetic acid,N-acetyl histamine, or N-telemethylhistamine, the major metabolites. No peak was seen at the position of γ-glutamyl histamine, a major metabolite in molluscs (Weinreich, 1979), which would have run just to the left of imidazolacetic acid in this solvent system. Thus, the 3H-histamine seems not to be metabolized to any great extent. 3H-histamine taken up into Drosophila heads (Sarthy, 1991) or synthesized from 3H-histidine (Battelle et al., 1991; Sarthy, 1991) is also not metabolized significantly.

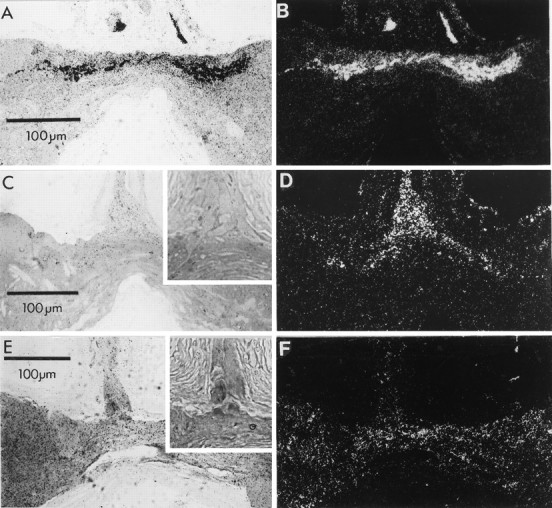

Blocking uptake of 3H-histamine into photoreceptor terminals

Four drugs known to block aminergic transport in general, or histamine uptake in other preparations, were tested for their ability to interfere with the uptake of 3H-histamine, assayed by autoradiography. Uptake was not blocked by cocaine (100 μm; Fig. 7A,B) or desipramine (100 μm; result not shown), but chlorpromazine (20 μm, n = 5; Fig.7C,D) or phenoxybenzamine (20 μm,n = 2; Fig. 7E,F) antagonized labeling of the photoreceptor axons and terminals. Phenoxybenzamine at 7 μm blocked uptake in five of eight preparations. Pyrilamine, a histamine H1 antagonist reported previously to block labeling in autoradiography (Stuart and Mekeel, 1990), also blocked uptake at 100 μm as assayed by scintillation counting, but was not pursued further because of the high concentration needed for block.

Fig. 7.

Pharmacological characteristics of3H-histamine uptake. Sections through the photoreceptor axons and expected region of terminals are shown in bright-field illumination (left) with phase-contrastinsets to reveal the axon profiles more clearly, and also in dark-field views (right) to make clear the distribution of the grains. A, B, Cocaine (100 μm) added to the incubation medium did not block labeling of photoreceptor axons and terminals. C,D, Chlorpromazine (20 μm) added to the incubation medium markedly decreased the labeling of axons, and terminal labeling was not detectable. Insets in this panel and in panel E show phase-contrast view of photoreceptor axons at the junction of the median ocellar nerve with the commissure. E,F, Phenoxybenzamine (20 μm) also blocked the uptake of 3H-histamine into photoreceptor axons and terminals.

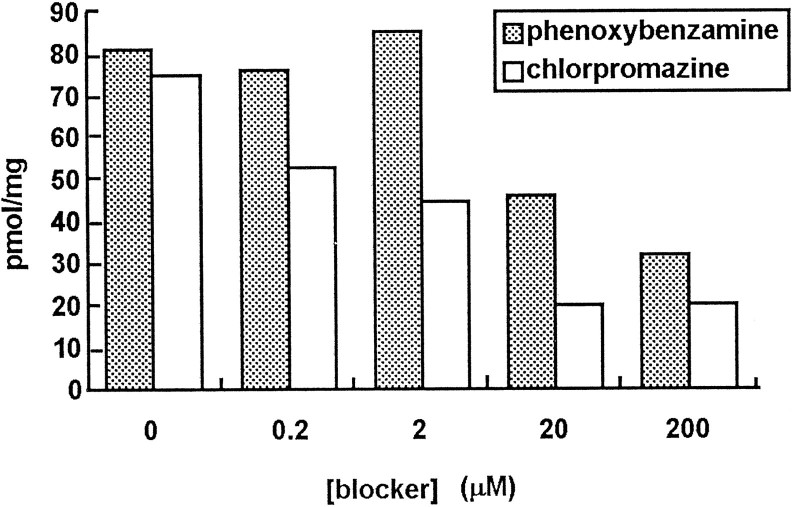

Chlorpromazine and phenoxybenzamine each exert a dose-dependent block of uptake assayed by scintillation counting (Fig. 8), with chlorpromazine being the more effective of the two drugs at lower doses. Neither antagonist is high affinity, however, because their highest concentrations reduced uptake by only 75%, whereas unlabeled histamine reduced it by 90%. We have reported (Stuart et al., 1993) that chlorpromazine (20 μm) prolongs the inhibition of the postsynaptic cell, an effect consistent with blocking transmitter uptake.

Fig. 8.

Dose-dependence of the antagonism of3H-histamine uptake by phenoxybenzamine and chlorpromazine. Each bar represents two preparations, each preincubated for 15 min in the presence of the blocker and subsequently incubated under standard conditions with the blocker and 20 μm3H-histamine.

Photoreceptor terminals incubated in the dark show markedly diminished uptake

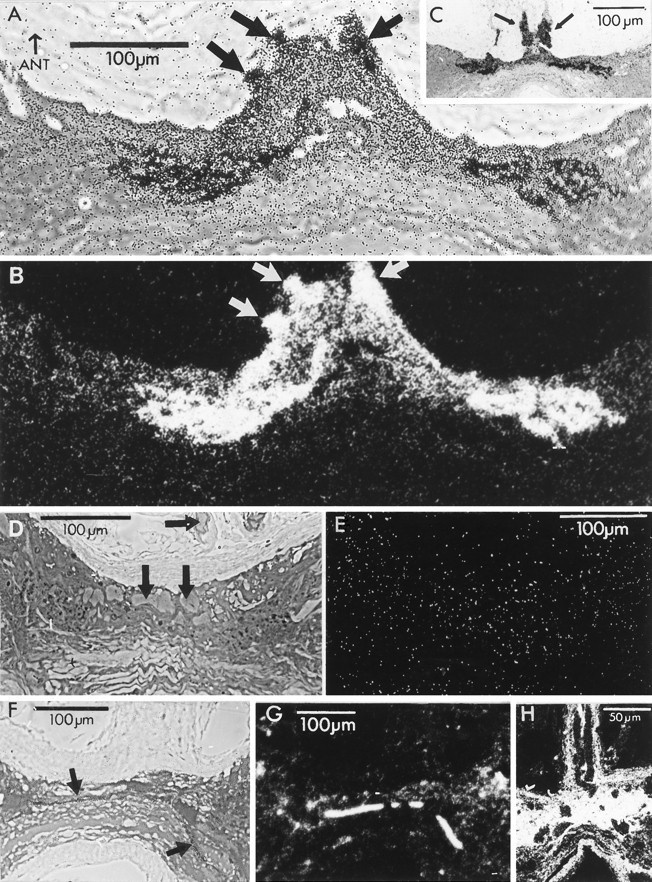

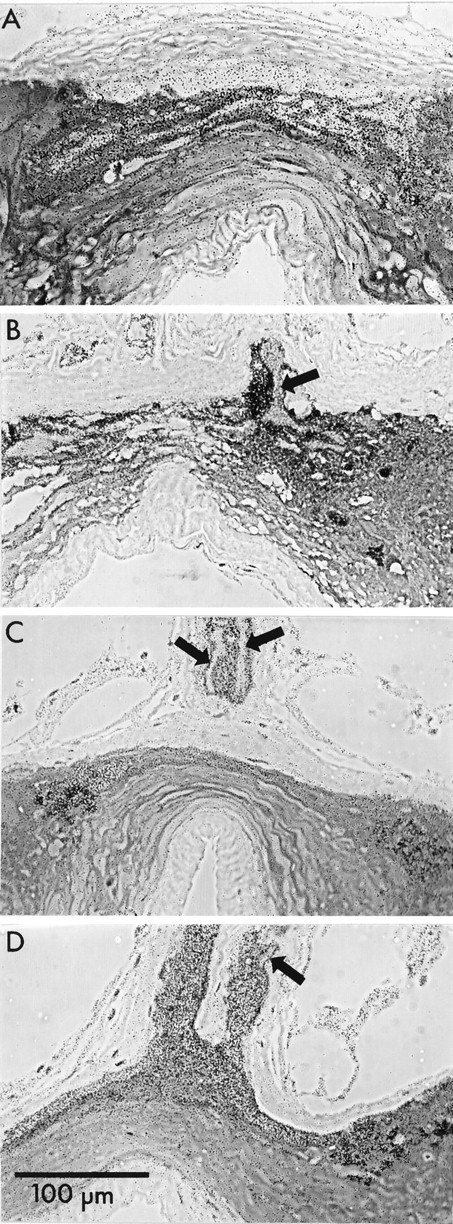

Figure 9 shows sections through photoreceptor axons and regions in which they would be expected to arborize in four preparations incubated in the dark. To our surprise, label was found predominantly over glia rather than photoreceptors. Axonal profiles in the nerve were outlined by labeled, surrounding glia (Fig.9C), and terminal arbors were labeled weakly or not at all.

Fig. 9.

Four preparations selected to represent the range of observations of labeling of ganglia incubated in3H-histamine in the dark. Phase-contrast images of sections through the entering photoreceptor axons or primary processes (arrows) and region of presynaptic terminals. The axons do not label as heavily as do their surrounding glia.A, Region of photoreceptor terminals. No labeled terminals were found in this or any other section. The heavy, diffuse label of the anterior compartment is primarily over glia (compare Fig. 1A, B). B, An axon sectioned at its bifurcation point. C, Two primary processes of an axon that has bifurcated at a more distal point. D, Section through the glial sheaths of two groups of primary photoreceptor processes illustrating the heavy glial labeling. Arrow points to the only photoreceptor axonal profile in the section. Scale bar inD applies to all panels.

This result was unexpected because Na+-dependent uptake of transmitters in other preparations increases when cells are relatively hyperpolarized, as would be the case with the dark-incubated photoreceptors, because the Na+ gradient is increased (Ayoub and Lam, 1987). These findings suggest that the balance of uptake of 3H-histamine into photoreceptor terminals and surrounding glia depends on some process or substance that reflects the state of activity of the photoreceptors.

DISCUSSION

This report that 3H-histamine is taken up selectively into barnacle photoreceptors adds a critical piece to the body of evidence that histamine is the transmitter of arthropod photoreceptors. Labeling of the terminals was greatest when the photoreceptors were stimulated by light, suggesting that the uptake of histamine is linked to its release at these highly active synapses. It is likely that a specific histamine transporter of the superfamily of Na+-dependent aminergic transmitter transporters (Amara and Kuhar, 1993) mediates this uptake. This transporter also exists in the glia surrounding the photoreceptors, because there is marked uptake into this compartment when the preparation is incubated in the dark.

Selective uptake supports a transmitter role for histamine

The presence of a removal mechanism is one of the criteria establishing that a given molecule is a transmitter. Although the criteria of synthesis, storage, and appropriate postsynaptic action of histamine have been satisfied for various arthropod preparations (for review, see Stuart and Callaway, 1991; also see Sarthy, 1991; Burg et al., 1993), uptake into photoreceptors had not been demonstrated clearly before this report. 3H-histamine was taken up only into glial cells of locust compound eye (Elias and Evans, 1984) or nonspecifically throughout Drosophila compound eye (Sarthy, 1991). Sarthy (1991) suggests that a permeability barrier interferes with demonstrating uptake into photoreceptors of insect compound eyes. There is indirect evidence for uptake into photoreceptors of the compound eye of Limulus (Hart and Battelle, 1991) and locust simple eyes (Schlemermeyer et al., 1989). Furthermore, the compound eyes of barnacle larvae also take up3H-histamine (E. Kempter, H. E. Mekeel, and A. E. Stuart, unpublished observations). Barnacle photoreceptors take up histamine at a bath concentration of 20 μm; although we do not know the actual concentration at the terminals, this concentration is within the range effective on postsynaptic cells (Callaway and Stuart, 1989b; Hardie, 1989).

For barnacle photoreceptors, the criteria that have been met to establish histamine as the transmitter (Callaway and Stuart, 1989b;Callaway et al., 1989) are that it is stored in the cell, particularly in the presynaptic terminals, that it mimics the effect of transmitter of the photoreceptors on the postsynaptic cell, that its postsynaptic action is blocked by compounds that block the action of the natural transmitter, and with this report, that it is selectively taken up into the presynaptic terminals. Furthermore, histamine is synthesized by median ocellar nerves and ganglia. 3H-histamine loaded into the preparation by uptake can be released by externally applied 100 mm K+ (Stuart and Callaway, 1991), but release in response to depolarization by light has not been shown for any arthropod photoreceptor.

3H-histamine uptake into other cell types

Mast cells, perhaps the best known histaminergic cell type, concentrate histamine in large granules and release it massively in response to a stimulus. Although one might expect a specific histamine transporter to be located in the membrane of these cells, this is not the case. Instead, histamine is synthesized from histidine and then concentrated in the granules by a proton-coupled general amine carrier that actually prefers 5HT over histamine (Ludowyke and Lagunoff, 1986). Uptake into barnacle photoreceptors is not by this type of transporter because 3H-5HT was not taken up.

Certain neurons located in the hypothalamus of all vertebrate species examined so far (Panula and Airaksinen, 1991) also show high levels of histamine and are likely to use it as a neurotransmitter. There is controversy over whether a transporter exists in these neurons (Schwartz et al., 1991). Vertebrate glial cells, however, seem to show high-affinity 3H-histamine uptake (Rafalowska et al., 1987; Huszti et al., 1990). For invertebrates, histaminergic neurons identified in molluscs (Turner and Cottrell, 1977; McCaman and Weinreich, 1985) take up3H-histamine selectively (Turner and Cottrell, 1977; Osborne et al., 1979; Turner et al., 1980; Schwartz et al., 1986;Elste et al., 1990). In Aplysia, this uptake is reported to be Na+-dependent (Schwartz et al., 1986).

Distribution of label in the photoreceptor neuron

It might seem peculiar at first glance that the uptake of3H-histamine is not localized to transmitter release sites in the terminals but occurs all along the photoreceptor axons; however, localization of the rat brain GABA transporter by antibodies (Radian et al., 1990; Pietrini et al., 1994) shows a distribution in the axons as well as in the terminals of GABAergic neurons in culture and in situ. Attempts have also been made to localize the presumed glutamate transporter in isolated glial cells (Brew and Attwell, 1987) and photoreceptors (Sarantis et al., 1988;Tachibana and Kaneko, 1988) of the vertebrate retina by iontophoresis of glutamate onto various cellular regions. Although the resolution of this approach is limited, glutamate-gated currents are maximum when glutamate is applied to the synaptic end of the photoreceptors or the endfeet of the glia cells, indicating polarity in the distribution of the uptake mechanism.

We found only a low level of 3H-histamine uptake into somata of the barnacle photoreceptors under our stimulus conditions. This result may be attributable not to the relative absence of the presumed transporter from the somatic membrane but to the Na+-dependence of the process: the somata would be expected to be depolarized for a good part of the incubation period by the light, causing a marked reduction in the Na+ gradient across the membrane. After incubation of molluscan ganglia in 3H-histamine, label is found over somata of histaminergic cells (Turner and Cottrell, 1977; Schwartz et al., 1986). On the other hand, the rat brain GABA transporter was not found in somata of neurons or of glial cells (Radian et al., 1990; Pietrini et al., 1994) and is targeted to the apical but not the basolateral membrane when expressed in polarized epithelial cells. The question of whether the histamine uptake mechanism is present throughout the barnacle photoreceptor or specifically in the axonal/synaptic domain requires further investigation.

3H-histamine uptake by terminals in the light and dark

Na+-dependent transporters typically take up their transmitter more avidly when the cell is relatively hyperpolarized and the Na+ gradient is comparatively large (Tachibana and Kaneko, 1988; Cammack and Schwartz, 1993), but we observed the opposite result for the photoreceptor terminals, which label more crisply in the light or flashing light when they are relatively depolarized than they do in the dark, when they are relatively hyperpolarized. In the dark, label seems stronger over glia.

Uptake into the presynaptic terminals might be influenced by factors in addition to the Na+ gradient in this specialized region. More active uptake might occur in the light if the intracellular histamine concentration falls when the cell depolarizes and releases transmitter, either because of the release itself or because the histamine is sequestered more actively into a vesicular pool during transmitter recycling. It is also possible that uptake might be linked to other presynaptic processes involved with transmitter release, such as ion or second messenger changes. In this regard, it will be of interest to examine how uptake into nonsynaptic regions of the cell depends on light and dark.

Footnotes

This research was supported by United States Public Health Service Grant EY03347 to A.E.S. We thank Dawn Merrick for technical assistance with thin layer chromatography, and Robert T. Fremeau and Kevin E. Martin for reading and criticism of this manuscript. Kevin E. Martin participated in some of the experiments.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Ann E. Stuart, Department of Physiology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7545.

Dr. Callaway’s present address: Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, University of Tennessee, Memphis, TN 38163.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amara SG, Kuhar MJ. Neurotransmitter transporters: recent progress. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1993;16:73–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.000445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayoub GS, Lam DM-K. Accumulation of γ-aminobutyric acid by horizontal cells isolated from the goldfish retina. Vision Res. 1987;27:2027–2034. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(87)90117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Battelle B-A, Calman BG, Andrews AW, Grieco FD, Mleziva MB, Callaway JC, Stuart AE. Histamine: a putative afferent neurotransmitter in Limulus eyes. J Comp Neurol. 1991;305:527–542. doi: 10.1002/cne.903050402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brew H, Attwell D. Electrogenic glutamate uptake is a major current carrier in the membrane of axolotl retinal glial cells. Nature. 1987;327:707–709. doi: 10.1038/327707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burg MG, Sarthy PV, Koliantz G, Pak WL. Genetic and molecular identification of a Drosophila histidine decarboxylase gene required in photoreceptor transmitter synthesis. EMBO J. 1993;12:911–919. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callaway JC, Stuart AE. Comparison of the responses to light and to GABA of cells postsynaptic to barnacle photoreceptors (I-cells). Vis Neurosci. 1989a;3:301–310. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800005496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callaway JC, Stuart AE. Biochemical and physiological evidence that histamine is the transmitter of barnacle photoreceptors. Vis Neurosci. 1989b;3:311–325. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800005502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callaway JC, Lasser-Ross N, Stuart AE, Ross WN. Dynamics of intracellular free calcium concentration in the presynaptic arbors of individual barnacle photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1157–1166. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-01157.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callaway JC, Masinovsky B, Edwards JS. Immunocytochemical study of arthropod neurons with antibodies specific to molluscan small cardioactive peptide and serotonin: a comparative study. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1985;11:326. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callaway JC, Stuart AE, Edwards JS. Immunocytochemical evidence for the presence of histamine and GABA in the photoreceptors of the barnacle, Balanus nubilus . Vis Neurosci. 1989;3:289–299. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800005484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cammack JN, Schwartz EA. Ions required for the electrogenic transport of GABA by horizontal cells of the catfish retina. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;472:81–102. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elias MS, Evans PD. Histamine in the insect nervous system: distribution, synthesis and metabolism. J Neurochem. 1983;41:562–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb04776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elias MS, Evans PD. Autoradiographic localization of3H-histamine accumulation by the visual system of the locust. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;238:105–112. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elste A, Koester J, Shapiro E, Panula P, Schwartz JH. Identification of histaminergic neurons in Aplysia . J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:736–744. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.3.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fahrenbach WH. The micromorphology of some simple photoreceptors. Z Zellforsch. 1965;66:233–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardie RC. Is histamine a neurotransmitter in insect photoreceptors? J Comp Physiol [A] 1987;161:201–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00615241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardie RC. Effects of antagonists on putative histamine receptors in the first visual neuropile of the housefly (Musca domestica ). J Exp Biol. 1988;18:221–241. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardie RC. A histamine-activated chloride channel involved in neurotransmission at a photoreceptor synapse. Nature. 1989;339:704–706. doi: 10.1038/339704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hart MK, Battelle B-A. Histamine: metabolism and release in the Limulus visual system. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:1151. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudspeth AJ, Stuart AE. Morphology and responses to light of the somata, axons, and terminal regions of individual photoreceptors of the giant barnacle. J Physiol (Lond) 1977;272:1–23. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp012031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudspeth AJ, Poo MM, Stuart AE. Passive signal propagation and membrane properties in median photoreceptors of the giant barnacle. J Physiol (Lond) 1977;272:25–43. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp012032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huszti Z, Rimanoczy A, Juhasz A, Magyar K. Uptake, metabolism, and release of 3H-histamine by glial cells in primary cultures of chick cerebral hemispheres. Glia. 1990;3:159–168. doi: 10.1002/glia.440030303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludowyke RI, Lagunoff D. Amine uptake into intact mast cell granules in vitro . Biochemistry. 1986;25:6287–6293. doi: 10.1021/bi00368a068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCaman RE, Weinreich D. Histaminergic synaptic transmission in the cerebral ganglion of Aplysia . J Neurophysiol. 1985;53:1016–1037. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.4.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan JR, Stuart AE. Subcellular distribution of a putative transporter for the transmitter histamine in an arthropod photoreceptor. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1995;21:867. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oland LA, Stuart AE. Pattern of convergence of the receptors of the barnacle’s three ocelli onto second-order cells. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55:882–895. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.5.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osborne NN, Wolter KD, Neuhoff V. In vitro experiments on the accumulation and release of 14C-histamine by snail ( Helix pomatia ) nervous tissue. Biochem Pharmacol. 1979;28:2799–2805. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90565-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panula P, Airaksinen MS. The histaminergic neuronal system as revealed with antisera against histamine. In: Watanabe T, Wada H, editors. Histaminergic neurons: morphology and function. CRC; Boca Raton: 1991. pp. 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pietrini G, Young JS, Edelmann L, Rudnick G, Caplan MJ. The axonal γ-aminobutyric acid transporter GAT-1 is sorted to the apical membranes of polarized epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4668–4674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radian R, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen JS, Castel M, Kanner BI. Imunocytochemical localization of the GABA transporter in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1319–1330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01319.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rafalowska U, Waskiewicz J, Albrecht J. Is neurotransmitter histamine predominantly inactivated in astrocytes? Neurosci Lett. 1987;80:106–110. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90504-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarantis M, Everett K, Attwell D. A presynaptic action of glutamate at the cone output synapse. Nature. 1988;332:451–453. doi: 10.1038/332451a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarthy PV. Histamine: a neurotransmitter candidate for Drosophila photoreceptors. J Neurochem. 1991;57:1757–1768. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb06378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlemermeyer E, Schutte M, Ammermuller J. Immunohistochemical and electrophysiological evidence that locust ocellar photoreceptors contain and release histamine. Neurosci Lett. 1989;99:73–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid A, Duncker M. On the function of histamine in the central nervous system of arthropods. Acta Biologica Hung. 1993;44:67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnapp BJ, Stuart AE. Synaptic contacts between physiologically identified neurons in the visual system of the barnacle. J Neurosci. 1983;3:1100–1115. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-05-01100.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz EA, Tachibana M. Electrophysiology of glutamate and sodium co-transport in a glial cell of the salamander retina. J Physiol (Lond) 1990;426:43–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz JC, Arrang JM, Garbarg M, Pollard H, Ruat M. Histaminergic transmission in the mammalian brain. Physiol Rev. 1991;71:1–51. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz JH, Elste A, Shapiro E, Gotoh H. Biochemical and morphological correlates of transmitter type in C2, an identified histaminergic neuron in Aplysia . J Comp Neurol. 1986;245:401–421. doi: 10.1002/cne.902450308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simmons PJ, Hardie RC. Evidence that histamine is a neurotransmitter of photoreceptors in the locust ocellus. J Exp Biol. 1988;138:205–219. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stockbridge NL, Ross WN. Localized Ca and calcium-activated potassium conductances in terminals of a barnacle photoreceptor. Nature. 1984;309:266–268. doi: 10.1038/309266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stuart AE, Callaway JC. Histamine: the case for a photoreceptor’s neurotransmitter. Neurosci Res [Suppl] 1991;15:S13–S23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stuart AE, Mekeel HE. Uptake of histamine into the presynaptic terminals of barnacle photoreceptors (Abstr). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:335. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stuart AE, Schmid EC, Mekeel HE. Chlorpromazine blocks the uptake of histamine into presynaptic terminals of barnacle photoreceptors and affects signals generated in the postsynaptic cell. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1993;19:938. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tachibana M, Kaneko A. l-glutamate-induced depolarization in solitary photoreceptors: a process that may contribute to the interaction between photoreceptors in situ . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5315–5319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner JD, Cottrell GA. Properties of an identified histamine-containing neurone. Nature. 1977;267:447–448. doi: 10.1038/267447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner JD, Powell B, Cotrell GA. Morphology and ultrastructure of an identified histamine-containing neuron in the central nervous system of the pond snail, Lymnaea tagnalis L. J Neurocytol. 1980;9:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF01205224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinreich D. γ-Glutamylhistamine: a major product of histamine metabolism in the marine mollusc Aplysia californica . J Neurochem. 1979;32:363–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]