Abstract

In rat brainstem slices, we investigated the effects of low-frequency stimulation (LFS) of the primary vestibular afferents on the amplitude of the field potentials evoked in the medial vestibular nuclei (MVN). LFS induced long-term effects, the sign of which depended on whether the vestibular neurons were previously conditioned by HFS. In unconditioned slices, LFS evoked modifications of the responses that were similar to those observed after HFS but had a smaller extension. In fact, LFS caused long-lasting potentiation of the N1 wave in the MVN ventral portion (Vp) and long-lasting depression of the N2 wave in the MVN dorsal portion (Dp), whereas it provoked small and variable effects on the N1 wave. By contrast, when the synaptic transmission was already conditioned, LFS influenced the synaptic responses oppositely, reducing or annulling the HFS long-term effects. This phenomenon was specifically induced by LFS, because HFS was not able to cause it. The involvement of NMDA receptors in mediating the LFS long-term effects was supported by the fact that AP-5 prevented their induction. In addition, the annulment of HFS long-term effects by LFS was also demonstrated by the shift in the latency of the evoked unitary potentials after LFS. In conclusion, we suggest that the reduction of the previously induced conditioning could represent a cancellation mechanism, useful to quickly adapt the vestibular system to continuous different needs and to avoid saturation.

Keywords: low-frequency stimulation, high-frequency stimulation, long-lasting effect, medial vestibular nucleus, NMDA receptor, field potential

Our recent experiments on rat brainstem slices provide evidence for the existence of long-term synaptic modifications in the medial vestibular nuclei (MVN) after high-frequency stimulation (HFS) of the primary vestibular afferents (Capocchi et al., 1992;Grassi et al., 1995). HFS induces a long-lasting increase in the monosynaptic (N1) component of the field potentials elicited in the ventral portion (Vp) of the MVN and long-lasting decrease of the polysynaptic (N2) component of the potentials in the dorsal portion (Dp) of the same nuclei, whereas it provoked small and variable effects on the N1 wave. The HFS effects are mediated by the activation of the glutamate NMDA receptors (Capocchi et al., 1992; Grassi et al., 1995), which have been demonstrated to contribute to afferent synaptic transmission in the MVN (Kinney et al., 1994; Takahashi et al., 1994) and to excitatory transmission within the nuclear intrinsic circuitry (Kinney et al., 1994).

This mechanism could be the basis of the long-term adaptive changes that take place in the vestibular nuclei responsible for many vestibular plasticity phenomena, such as the vestibular reflex adaptation (Broussard et al., 1992; Khater et al., 1993, du Lac et al., 1995) and rebalancing after hemilabyrinthectomy (de Waele et al., 1990;Darlington et al., 1992; Smith et al., 1992). In fact, behavioral studies have shown that NMDA receptors are involved in the induction and maintenance of vestibular compensation (de Waele et al., 1990;Sansom et al., 1990; Darlington et al., 1992; Pettorossi et al., 1992;Smith and Darlington, 1992; Smith et al., 1992; Darlington et al., 1995) and in the development of negative optokinetic afternystagmus (Pettorossi et al., 1994).

The long-term effect provoked by HFS in MVN could not be the only synaptic modification that the system can express. In fact, one could hypothesize that long-term effects with different characteristics and/or opposite sign can be induced by changing the pattern of stimulation. This hypothesis has been prompted because of growing evidence that in other brain structures, different long-term effects can be provoked by varying the stimulus frequency. In fact, in the hippocampus and neocortex, wherein HFS induces LTP, low-frequency stimulation (LFS) evokes long-term depression (LTD), consisting in a long-lasting reduction of synaptic efficacy (Dunwiddie and Lynch, 1978;Dudek and Bear, 1992; Mulkey and Malenka, 1992; Artola and Singer, 1993; Kirkwood et al., 1993; Christie et al., 1994; Kirkwood and Bear, 1994; Linden, 1994; Linden and Connor, 1995). Furthermore, it has been reported that in the hippocampus, LFS can also counteract the long-lasting HFS synaptic facilitation, depotentiating LTP (Barrionuevo et al., 1980; Staubli and Lynch, 1990; Fujii et al., 1991; Dudek and Bear, 1993; Larson et al., 1993; Wexler and Stanton, 1993; Bashir and Collingridge, 1994; O’Dell and Kandel, 1994).

On the basis of these results, we became interested in extending the study about the synaptic plasticity of the MVN, by analyzing the long-term effects of a low-frequency pattern of stimulation. In particular, the present work was aimed at investigating whether LFS could evoke long-term modifications in the Vp and Dp of MVN and whether LFS could affect the previously conditioned responses, by delivering LFS before and after HFS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Slice preparation. The experiments were performed on brainstem slices obtained from 30 Wistar rats (150–250 gm). The method for preparing and maintaining the slices has been reported previously (Capocchi et al., 1992; Grassi et al., 1995). Briefly, transverse 400 μm thick slices, containing the middle-rostral part of MVN, were incubated at 30–31°C in oxygenated artificial CSF (ACSF) and after 1 hr transferred to an interface-type recording chamber in which they were perfused at a rate of 1–2 ml/min. In some experiments, 500-μm-thick slices were used.

Electrophysiological techniques. Ninety-five slices were used. The field potentials, elicited by vestibular afferent stimulation, were recorded in the Dp or Vp of MVN, by means of glass micropipettes filled with 2 m sodium chloride (resistance 3–10 MΩ). Stimulation of the ipsilateral vestibular afferents was performed with a bipolar NiCr-insulated electrode. In most of the experiments, a stimulating electrode was placed at the point where the vestibular afferents enter the MVN, which is in a narrow zone at the medial border of the superior or lateral vestibular nucleus (Fig. 1). The distance between stimulating and recording electrodes was ∼1 mm. Stimulus test parameters were 40–100 μA intensity, 0.07 msec duration, and 0.06 Hz frequency. In this condition, the field potentials were always evoked. Moreover, to avoid possible activation of fibers mediating internuclear interactions, in some experiments stimulating electrode was placed more laterally in the course of the vestibular root before entering the vestibular nuclear complex (Fig. 1). Because of the stimulating distance, the thickness of the slices was increased to 500 μm. In this condition, field potentials were evokable, but the eliciting probability was very low, so that suitable data were collected only from 10 slices. In addition, in some experiments we extracellularly recorded the unitary potentials elicited in the Vp or Dp by the vestibular afferent stimulation. The recorded potentials were amplified, filtered with a wide band filter, and stored in a computer (386) equipped with a data acquisition card (AT-MIO-16E-2, National Instruments, Austin, TX).

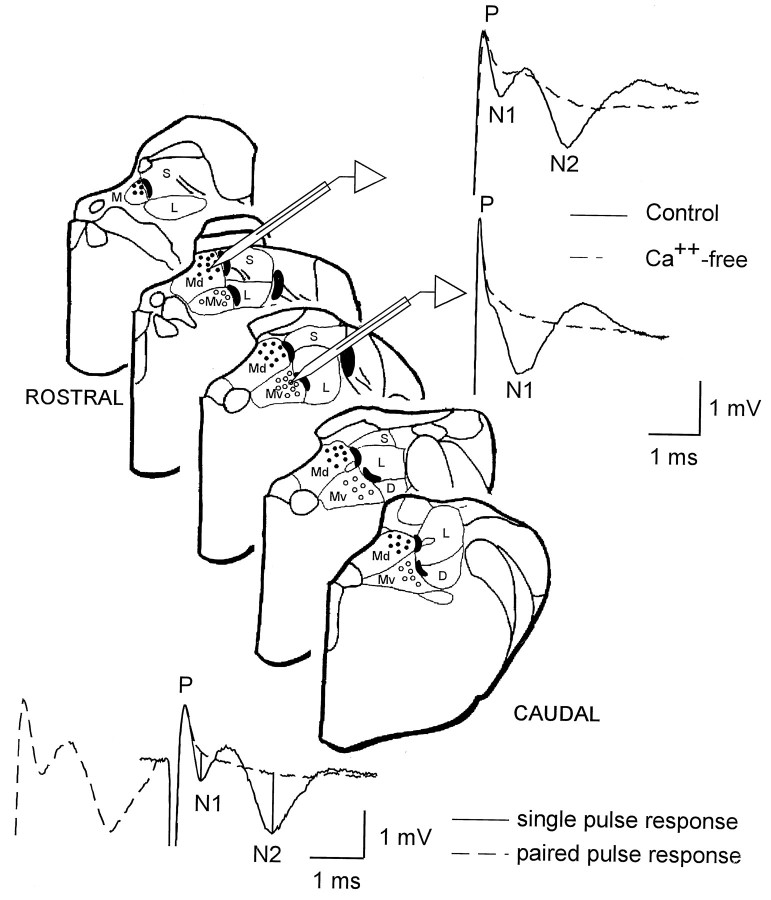

Fig. 1.

Recording sites in the dorsal (solid dots) and ventral (open dots) portion of the MVN and central and peripheral stimulating zones (black areas) are plotted on the diagrams of 0.5 mm spaced brainstem slices. On theright, the typical vestibular field potentials recorded in the Dp and Vp of MVN in normal and Ca2+-free solution are shown. At the bottom, single-pulse response is superimposed to a 3 msec paired-pulse stimulation to show how N1 and N2 peak negative voltages were calculated with respect to the baseline (vertical lines). D, Descending vestibular nucleus; M, medial vestibular nucleus; Md, Dp of the medial vestibular nucleus; Mv, Vp of the medial vestibular nucleus; L, lateral vestibular nucleus;S, superior vestibular nucleus.

Field potential characteristics. In the Dp, the recorded field potentials consisted of three waves: a positive wave (P) at a latency of 0.2 ± 0.08 msec (n = 25), the first negative wave (N1) at a latency of 0.62 ± 0.28 msec (n = 25), and the second negative one (N2) at 1.51 ± 0.53 msec (n = 25) (Fig. 1). In the Vp, the recorded field potentials were characterized by P and N1 waves, whereas the N2 component was not clearly detectable (Fig. 1). According to Shimazu and Precht (1965), the P wave represents the primary vestibular fiber activation, whereas the N1 and N2 the monosynaptic and polysynaptic activation of the secondary vestibular neurons, respectively. At the beginning of each experiment, the postsynaptic nature of the N1 and N2 waves was verified by paired-pulse test. Intervals shorter than 4 msec always caused the N1 and N2 waves to disappear leaving the P wave unaffected (Fig. 1). In some experiments, the synaptic nature of the waves was further investigated by replacing the standard medium with a Ca2+-free solution, in which Ca2+ was eliminated and Mg2+ was elevated to 6.3 mm. In this condition, the N1 and N2 waves disappeared (Fig. 1).

Conditioning stimulations. We used HFS (4 bursts at 100 Hz applied with alternated polarity for 2 sec with a 5 sec interval) and LF (a single low-frequency at 1, 2, and 5 Hz applied for 1 min with polarity that was alternated every 10 sec). LFS was applied by using a sequence of increasing frequencies from 1 to 5 Hz to study the effect of LFS before HFS and of decreasing frequencies (from 5 Hz to 1 Hz) for that of LFS after HFS.

Drugs. In some experiments, the NMDA receptor antagonistdl-AP-5 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used; 100 μm AP-5 was freshly prepared in the ACSF and perfused through the recording chamber for ∼20 min.

Data collection. The effects of conditioning stimulations were evaluated by measuring the amplitude of the N1 and N2 waves. We calculated the wave amplitude as the difference between the wave peak negative voltage and a baseline influenced by the electrical stimulus decay (Fig. 1). To quantify this voltage decay, responses to 3 msec interval paired-pulse test were recorded before and after each conditioning stimulation. In fact, the second response of the paired-pulse stimulation only represented the combination of electrical stimulus and P wave. To show the time course of the effects, the wave amplitudes were measured every 15 sec and expressed as a percentage of the baseline (the mean of the responses recorded within the first 5 min of each experiment). To compare the effects in different experiments, we calculated the means and SD of the percent values within a 5 min interval before any treatment (control) and at the poststimulus steady state (post-treatment). In each experiment, the differences between pre- and poststimulus values were statistically analyzed using unpairedt tests and statistical significance was established atP < 0.05.

The modifications induced by HFS and LFS on the unitary activity were evaluated by measuring the latency of the peak of the potential from the shock artifact. To compare the effect in different experiments, we averaged the latency values within a 5 min interval before and after HFS or LFS.

At the end of each experiment, the recording and stimulating sites were marked by delivering DC current of 50–100 μA for 10–20 sec and subsequently verified by histological analysis.

RESULTS

Effect of LFS before HFS on the vestibular field potentials in the Vp of MVN

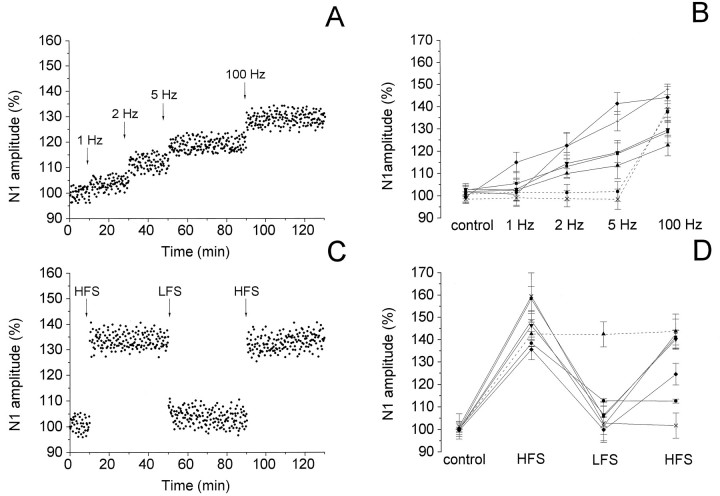

In the Vp of MVN, LFS (at 1–5 Hz) delivered before HFS induced potentiation of the N1 wave lasting more than 40 min in 5 of 10 field potentials (Fig. 2A,B). In two cases, the N1 amplitude was enhanced by stimulating at 1, 2, and 5 Hz, whereas in the other three cases only at 2 and 5 Hz (Fig. 2B). No effect was observed in the remaining cases. The LFS-induced enhancement of the N1 amplitude depended on stimulus frequency. In fact, the N1 wave increased to 103.76 ± 5.26% at 1 Hz (n = 2), 116.33 ± 5.60% at 2 Hz (n = 5), and 125.06 ± 11.59% at 5 Hz (n = 5) (Fig. 2B). Afterward, HFS caused a further increase in the N1 wave to 135.64 ± 9.04% in five cases and induced potentiation in the other two cases unaffected by LFS (Fig.2A,B).

Fig. 2.

Effect of LFS applied before (A, B) and after (C, D) HFS on the N1 wave of the field potentials recorded in the Vp of MVN. A, C, Time course of the effects in a single experiment. In this and in the following figures, the wave amplitude was measured every 15 sec, expressed as a percentage of the baseline and plotted as a function of time. The arrowsindicate the LFS and HFS delivery time. B, D, Effects in 7 of 10 experiments. The points represent the mean amplitude ± SD of the wave evaluated in each experiment within 5 min intervals, expressed as a percentage of the baseline. Dashed lines indicate the cases in which LFS had no effect. The LFS and HFS unaffected cases are not shown.

Effect of LFS after HFS on the vestibular field potentials in the Vp of MVN

In 7 of 10 slices, HFS induced potentiation of the N1 wave to 146.82 ± 9.24% (Fig. 2C,D). In these slices, we tested the effect of LFS delivered after having potentiated the N1 wave. In six of seven potentiated slices, LFS caused a reduction of the N1 wave to 104.66 ± 4.58%, lasting >40 min (Fig. 2C,D). In four cases, this effect was produced by 5 Hz, and in the other two experiments it followed 1 Hz. The lowering of the potentiated responses was a specific effect of LFS, because it was never caused by HFS. HFS applied again during the HFS-induced potentiation caused no effect. In fact, it was not able to reverse the previous potentiation but not even to increase it. On the other hand, HFS delivered after having reduced the N1 potentiation by LFS enhanced the N1 wave again to 136.75 ± 8.4% in four of six cases (Fig. 2C,D).

To provide direct evidence for the dependence of the LFS effect on the delivery time relative to the HFS, LFS was applied before and after HFS on the same field potentials. In two of three cases, LFS (5 Hz) enhanced the N1 wave to 121.60 ± 5.07% when delivered before HFS and reduced it to 103.43 ± 3.91% when applied after HFS (Fig.3A).

Fig. 3.

Effects of LFS applied before and after HFS in the same experiment. A, LFS effects on the N1 wave recorded in Vp and on the N2 wave recorded in Dp (B). Thearrows indicate the LFS and HFS delivery time. All else is as in the legend of Figure 2, A and C.

This stimulation sequence was also used in the cases in which more lateral stimulations were performed. The results were similar to those obtained by the more central stimulations. In fact, in three cases, LFS at 5 Hz increased the N1 wave to 119.35 ± 4.75% when applied before HFS. In addition, LFS applied after having potentiated the N1 wave to 138.89 ± 6.25% by HFS caused N1 reduction to 103.46 ± 3.6%.

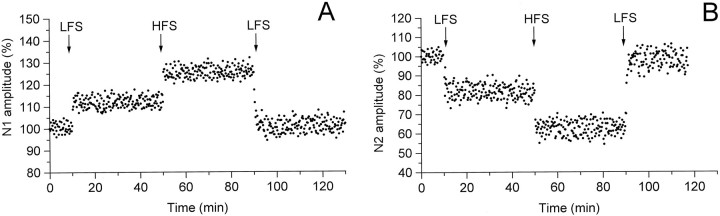

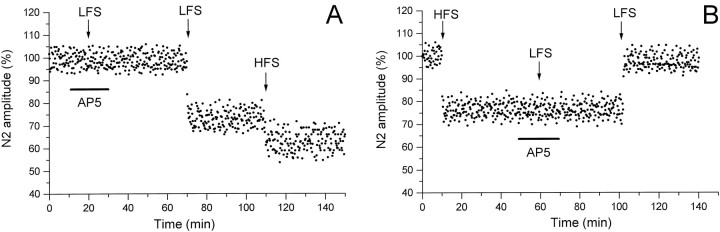

Role of NMDA receptors in the induction of LFS effects in the Vp of MVN

The involvement of NMDA receptors in inducing the LFS effects was tested by using AP-5. Under AP-5, LFS delivered both before (three slices) and after HFS (three slices) was ineffective (Fig.4A,B). The LFS effects could only be induced after drug wash-out (Fig. 4A,B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of AP-5 on the induction of LFS-dependent N1 long-term modifications before (A) and after (B) HFS. The arrows indicate the LFS and HFS delivery time, and the horizontal bars represent the AP-5 application time. All else is as in the caption of Figure 2,A and C.

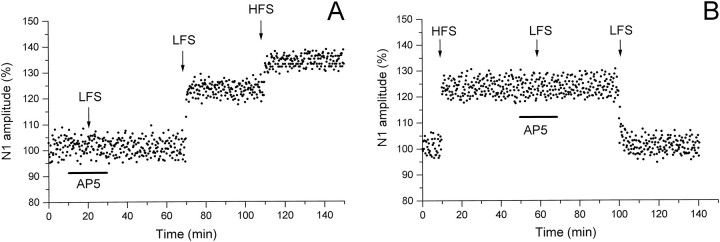

Effect of LFS after HFS on unitary activity in the Vp of MVN

In seven slices, we examined the effect of HFS and LFS on the unitary activity elicited in the Vp by vestibular afferent stimulation. The evoked unitary potentials showed a latency ranging from 1.14 to 2.56 msec. The unitary evoked activity was ascertained by comparing the morphology of the evoked potentials with that of spontaneous discharging potentials. In addition, the evoked potentials showed an all-or-nothing response. The latency of five of seven units significantly decreased by approximately 0.10 ± 0.05 msec after HFS. Afterwards, in these units, stimulation at 1–5 Hz provoked a significant latency increase of approximately 0.12 ± 0.08 msec (Fig.5).

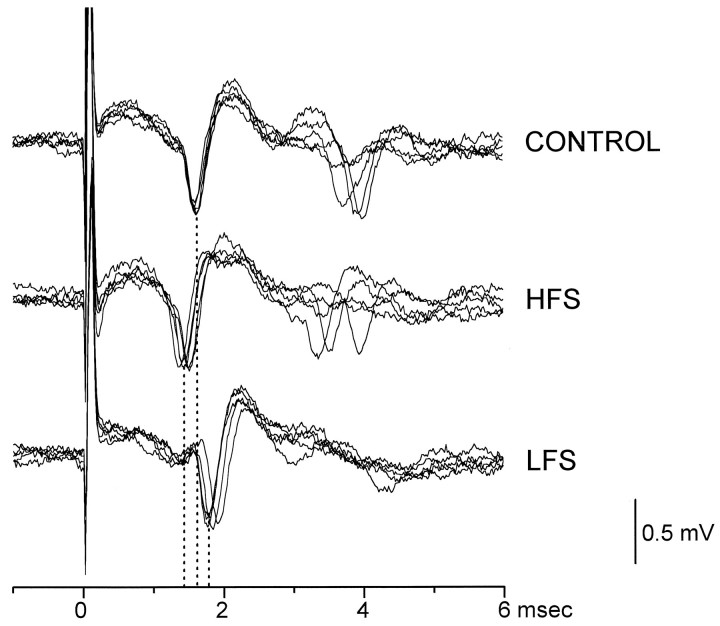

Fig. 5.

Typical effects of HFS and LFS on the peak latency of evoked unitary potentials in the Vp of MVN. The topfive superimposed traces show the potentials recorded before HFS (CONTROL). In the following traces, the potentials were recorded 5 min after HFS (HFS) and 5 min after LFS delivered after HFS (LFS). The dotted lines indicate the shift of the latency (mean values) of the early potential. A similar trend in the latency shift is shown by the late potential. Amplitude and time calibration apply for all recordings.

Effect of LFS before HFS on the vestibular field potentials in the Dp of MVN

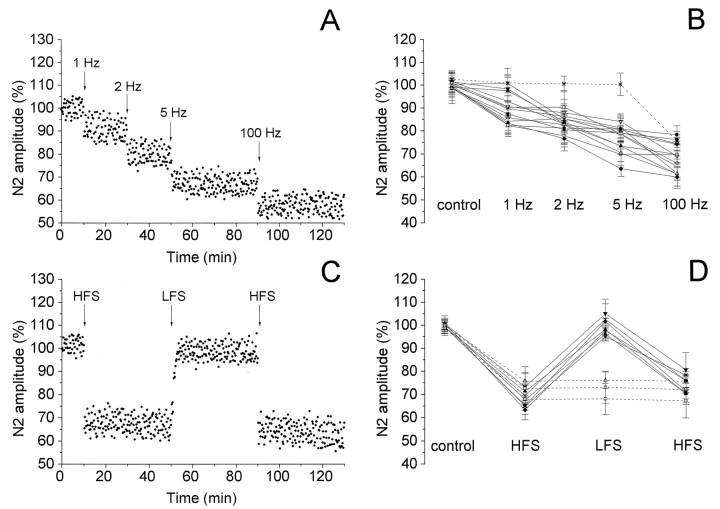

LFS caused depression of the N2 component, lasting >40 min in 13 of 18 field potentials recorded in the Dp of MVN (Fig.6A,B). In 10 cases, the N2 wave was depressed by all LFS (1–5 Hz) tested, whereas in the other 3 cases only by 2 Hz and 5 Hz (Fig. 6B). The N2 amplitude was progressively decreased with increasing stimulus frequency to reach 90.35 ± 6.7% at 1 Hz (n = 10), 84.46 ± 5.8% at 2 Hz (n = 13), and 77.86 ± 8.5% at 5 Hz (n = 13) (Fig. 6B). HFS applied after the LFS sequence provoked a further decrease in the N2 amplitude of the already depressed responses to 68.39 ± 6.3% and induced the depression in the unaffected potential (Fig.6A,B).

Fig. 6.

Effect of LFS applied before (A, B) and after (C, D) HFS on the N2 wave of the field potentials recorded in the Dp of MVN. A, C, Time course of the effects in a single experiment. The arrows indicate the LFS and HFS delivery time. All else is as in the caption of Figure 2, Aand C. Right, Effects in 14 (B) and 10 (D) experiments. All else is as in the caption of Figure 2,B and D.

In all of the cases in which N2 were affected by LFS and HFS, the N1 wave showed slight and variable modifications, consisting in either no change (2 cases), or in LTD (7 cases) or LTP (3 cases), with maximal amplitude variations no >7.5% of the controls.

Effect of LFS after HFS on the vestibular field potentials in the Dp of MVN

HFS induced a depression of the field potentials recorded in the Dp, consisting in a reduction of the N2 wave to 68.83 ± 3.84% in 10 of 15 slices (Fig. 6C,D). The N1 wave was slightly depressed (6 cases), slightly potentiated (2 cases), and unaffected (2 cases) after HFS. LFS applied after HFS restored the N2 and N1 amplitude to the control value (99.26 ± 3.66 and 101.23 ± 2.35%) in 7 of 10 slices (Fig. 6C,D). This effect lasted >40 min. It was mostly obtained by using 1 Hz stimulation, and it could never be achieved by HFS. In all the examined cases, HFS delivered during the LFS effect again provoked depression of the N2 wave to 74.53 ± 3.79% (Fig. 6C,D) and slight and variable modifications in the N1 one.

In addition, we tested the LFS effect before and after HFS on the same field potentials. In three of four cases, LFS before HFS depressed the N2 wave to 78.52 ± 2.75% (Fig. 3B), and after HFS enhanced the depressed N2 wave from 69.78 ± 4 to 100 ± 3.86% (Fig.3B). In these cases, the N1 wave was slightly depressed by LFS before HFS, and reached the control value by LFS applied after HFS.

The same trial was used in the more lateral stimulation cases. Four potentials were affected by LFS delivered before and after HFS. In fact, LFS (5 Hz) before HFS induced depression of the N2 wave to 75.54 ± 3.28%, and after HFS, which depressed the N2 wave to 62.35 ± 4.34%, increased it to 99.89 ± 2.56%. In all of these cases, the N1 wave was also slightly depressed by LFS before HFS and restored to the control value by LFS after HFS.

Role of NMDA receptors in the induction of LFS effects in the Dp of MVN

In the presence of AP-5, LFS when delivered before HFS (three cases) as well as after HFS (three cases) failed to induce any effect (Fig. 7A,B). By contrast, the LFS long-lasting phenomena were observed after drug wash-out (Fig.7A,B).

Fig. 7.

Effect of AP-5 on the induction of LFS-dependent N2 long-term modifications before (A) and after (B) HFS. The arrows indicate the LFS and HFS delivery time, and the horizontal bars represent the AP-5 application time. All else is as in the caption of Figure 2,A and C.

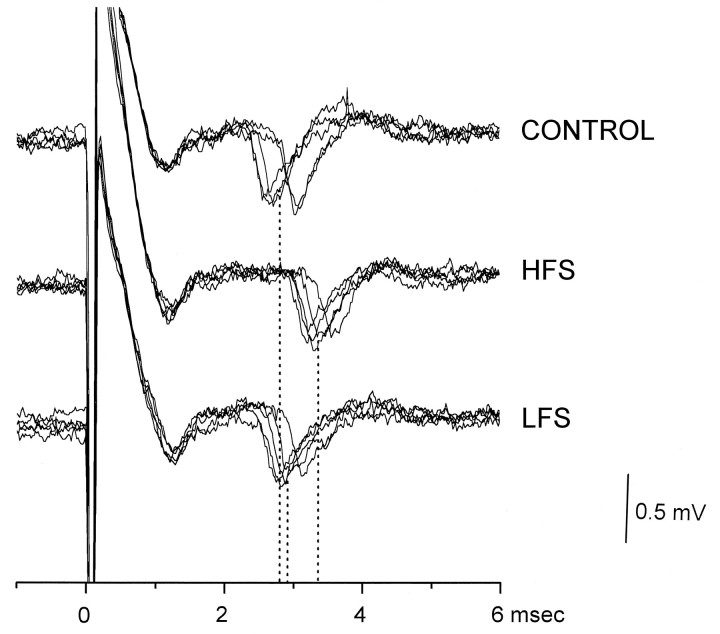

Effect of LFS after HFS on the unitary activity in the Dp of MVN

In the Dp, we recorded six unitary potentials evoked by vestibular afferent stimulation, showing latency ranging from 1.12 to 2.95 msec. In four units, HFS induced a significant increase in the latency of 0.25 ± 0.17 msec. In these units, LFS significantly reduced the latency to reach pre-HFS values (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Typical effects of HFS and LFS on the peak latency of a single evoked potential in the Dp of MVN. Amplitude and time calibration apply for all recordings. All else is as in the Figure 5caption.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have shown that LFS of the primary vestibular afferents can induce long-term synaptic modifications in the MVN. However, the sign of these effects depended on whether a previous HFS conditioning was present or not when LFS was delivered. Before HFS, LFS evoked modifications of the responses that were similar to those obtained after HFS but had a smaller extension. LFS enhanced the N1 wave in the Vp and decreased the N2 potentials in the Dp of MVN, whereas it provoked small and variable effects on the dorsal N1 wave. These changes lasted for >40 min and depended on the activation of the NMDA receptors, because they were abolished by the NMDA receptor antagonist AP-5.

By contrast, LFS delivered when the HFS long-term effects were induced, influenced the field potentials oppositely. In fact, LFS reduced or canceled the N1 wave potentiation in the Vp and the N2 depression, as well as the N1 changes in the Dp of MVN. These effects were also long-lasting, because they remained stable for >40 min. In addition, their induction required the NMDA receptor activation. The possibility to reduce or cancel previously induced synaptic modifications was an exclusive effect of LFS, because HFS was never effective in producing it.

Most of these results were obtained by stimulating at the border of the MVN, but similar effects were also seen using more lateral stimulation, at the point where the primary afferents enter the vestibular nuclear complex. These latter findings lead us to conclude that activation of internuclear fibers, which could occur with the central stimulation, is not necessary for inducing the HFS and LFS effects, as the only primary vestibular afferent activation can be sufficient to cause them.

Because the field potential waves are the expression of the activation of several neurons, we provided more direct evidence for the LFS capability to reverse the HFS effects, by studying single evoked units. Considering that the potentiation should be reflected in a decrease and the depression in an increase of the spike latency, our data from a single unit study fully confirm those obtained from the evoked field potential analysis. In fact, both in the Vp and Dp of MVN, LFS given after HFS annulled the latency shift previously provoked by HFS.

As far as the Vp of MVN is concerned, our results indicate that LFS does not induce a persistent synaptic depression (LTD) in unconditioned synapses, but it can cause LTD when LTP is present. The net result of this LTD is the annulment of LTP. Such a form of LTD has been described in the hippocampus (Barrionuevo et al., 1980; Staubli and Lynch, 1990; Fujii et al., 1991, Dudek and Bear, 1993; Larson et al., 1993;Wexler and Stanton, 1993; Bashir and Collingridge, 1994; O’Dell and Kandel., 1994), and the authors adopted the term “depotentiation” to distinguish it from the LTD in unconditioned synapses, although the same intracellular mechanisms to reduce synaptic effectiveness have been suggested. It has been demonstrated that depotentiation is not attributable to a masking of LTP by LTD, but to a real cancellation of LTP (Mulkey and Malenka, 1992; Dudek and Bear, 1993; Christie et al., 1994). In our experiments, we have not a definitive evidence to ascribe depotentiation to either mechanism. However, the cancellation seems to be the more likely mechanism, because HFS delivered after depotentiation can induce LTP again.

Regarding the Dp of MVN, we believe that the effects induced by HFS and LFS, even if opposite to those observed in Vp, are based on the same mechanisms. In fact, the results obtained by using GABAAand GABAB receptor antagonists (Grassi et al., 1995) showed that the long-lasting depression of vestibular responses in Dp is attributable to an enhancement of the GABA-inhibitory effect, caused by an HFS-dependent LTP on inhibitory GABAergic interneurons. Such an increase in GABAergic interneuron activity, reducing the excitability of this portion of MVN, causes a long-lasting depression of the polysynaptic responses. Thus, the disappearance of depression after LFS would be the result of LTP cancellation, restoring the normal amplitude of the responses. Concerning the N1 wave, the fact that it can be potentiated, depressed, or unchanged after HFS seems to be dependent on the extension of the inhibitory network impinging on the monosynaptically activated neurons (Grassi et al., 1995). However, independently of the sign, LFS constantly abolished the HFS effects on the N1 wave. Therefore, it seems that there is no difference between the Vp and Dp of MVN about the mechanisms underlying long-term synaptic modifications.

On the basis of our results, it seems that changes in the long-lasting effects can only result using different frequencies of stimulation. In particular, we can increase the extension of the previous induced long-term effect by increasing the frequency, but we can reduce or cancel it only by decreasing the stimulus frequency. Therefore, the effective frequencies for LTP induction are not necessarily high frequencies, but probably any frequency higher than the stimulus test, whereas the effective frequencies to counteract the induced potentiation should be the lower ones.

The mechanism that has been prompted to explain the opposite effects induced by HFS and LFS in other structures is based on the change of dynamic concentration of intracellular Ca2+ after different frequency stimulations and on the different threshold for activating Ca2+-dependent events leading to LTP and LTD (Mulkey and Malenka, 1992; Artola and Singer, 1993; Malenka and Nicoll, 1993; Christie et al., 1994; Linden, 1994; O’Dell and Kandel, 1994; Linden and Connor, 1995). However, a new aspect emerging from our work is that LFS can produce LTP instead of LTD in unconditioned neurons and LTD in conditioned ones. In our opinion, this new evidence could be explained within the above-reported hypothesis, when considering the possible interaction between LTP and LTD activation thresholds (Christie et al., 1994; Linden and Connor, 1995). Whether HFS causes an LFS to produce LTD through the synaptic gain modification or a specific synaptic molecular change as a long-lasting activation of metabotropic glutamatergic receptors (Wexler and Stanton, 1993;Bortolotto et al., 1994) is to be tested in future experiments.

In conclusion, MVN is provided with mechanisms to enhance the synaptic efficacy through LTP and to quickly cancel it through LTD. Because, in the vestibular system, the synaptic depression does not seem to exist as priming mechanism, the presence of a cancellation phenomenon to abolish the induced synaptic modifications enhances the vestibular plastic capability and avoids its saturation.

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche and by the Ministry of University and Scientific Research. We thank Mrs. H. A. Giles for English language advice and Mr. D. Bambagioni for technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Silvarosa Grassi, Istituto di Fisiologia Umana, Università di Perugia, Via del Giochetto, I-06100 Perugia, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Artola A, Singer W. Long-term depression of excitatory synaptic transmission and its relationship to long-term potentiation. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:480–487. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90081-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrionuevo G, Shottler F, Lynch G. The effect of repetitive low-frequency stimulation on control and “potentiated” synaptic responses in the hippocampus. Life Sci. 1980;27:2385–2391. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashir ZI, Collingridge GL. An investigation of depotentiation of long-term potentiation in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Exp Brain Res. 1994;100:437–443. doi: 10.1007/BF02738403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bortolotto ZA, Bashir ZI, Davies CH, Collingridge GL. A molecular switch activated by metabotropic glutamate receptors regulates induction of long term potentiation. Nature. 1994;368:740–743. doi: 10.1038/368740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broussard DM, Bronte-Stewart HM, Lisberger SG. Expression of motor learning in the response of the primate vestibulo-ocular reflex pathway to electrical stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:1493–1508. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.6.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capocchi G, Della Torre G, Grassi S, Pettorossi VE, Zampolini M. NMDA-mediated long term modulation of electrically evoked field potentials in the rat medial vestibular nuclei. Exp Brain Res. 1992;90:546–550. doi: 10.1007/BF00230937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christie BR, Kerr DS, Abraham WC. The flip side of synaptic plasticity: long term depression mechanisms in the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1994;4:127–135. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darlington CL, Flohr H, Smith PF. Molecular mechanisms of brainstem plasticity: the vestibular compensation model. Mol Neurobiol. 1992;5:355–367. doi: 10.1007/BF02935558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darlington CL, Gallagher JP, Smith PF. In vitro electrophysiological studies of the vestibular nucleus complex. Prog Neurobiol. 1995;45:335–346. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)00056-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Waele C, Vibert N, Baudrimont M, Vidal PP. NMDA receptors contribute to the resting discharge of vestibular neurons in the normal and hemilabyrinthectomized guinea pig. Exp Brain Res. 1990;81:125–133. doi: 10.1007/BF00230108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudek SM, Bear MF. Homosynaptic long-term depression in area CA1 of hippocampus and the effects of NMDA receptor blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4363–4367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudek SM, Bear MF. Bidirectional long-term modification of synaptic effectiveness in the adult and immature hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2910–2918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-02910.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.du Lac S, Raymond JL, Sejnowski TJ, Lisberger SG. Learning and memory in the vestibulo-ocular reflex. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1995;18:409–441. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.002205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunwiddie T, Lynch G. Long term potentiation and depression of synaptic responses in the rat hippocampus: localization and frequency dependency. J Physiol (Lond) 1978;276:353–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujii S, Saito K, Miyakawa H, Ito K, Kato H. Reversal of long-term potentiation (depotentiation) induced by tetanus stimulation of the input to CA1 neurons of guinea pig hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 1991;555:112–122. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90867-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grassi S, Della Torre G, Capocchi G, Zampolini M, Pettorossi VE. The role of GABA in NMDA-dependent long term depression (LTD) of rat medial vestibular nuclei. Brain Res. 1995;699:183–191. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00895-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khater TT, Quinn KJ, Pena J, Baker JF, Peterson BW. The latency of the cat vestibulo-ocular reflex before and after short- and long-term adaptation. Exp Brain Res. 1993;94:16–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00230467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinney GA, Peterson BW, Slater NT. The synaptic activation of N -methyl-d-aspartate receptors in the rat medial vestibular nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1588–1595. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkwood A, Bear MF. Homosynaptic long-term depression in the visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3404–3412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03404.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirkwood A, Dudek SM, Gold JT, Aizenman CD, Bear MF. Common forms of synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus and neocortex in vitro . Science. 1993;260:1518–1521. doi: 10.1126/science.8502997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larson J, Xiao P, Lynch G. Reversal of LTP by theta frequency stimulation. Brain Res. 1993;600:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90406-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linden DJ. Long-term synaptic depression in the mammalian brain. Neuron. 1994;12:457–472. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linden DJ, Connor JA. Long-term synaptic depression. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1995;18:319–357. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity: multiple forms and mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:521–527. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90197-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulkey RM, Malenka RC. Mechanisms underlying induction of homosynaptic long-term depression in area C1 of the hippocampus. Neuron. 1992;9:967–975. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90248-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Dell TJ, Kandel ER. Low-frequency stimulation erases LTP through an NMDA receptor-mediated activation of protein phosphatases. Learn Memory. 1994;1:129–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pettorossi VE, Della Torre G, Grassi S, Zampolini M, Capocchi G, Errico P. Role of NMDA receptors in the compensation of ocular nystagmus induced by hemilabyrinthectomy in guinea pig. Arch Ital Biol. 1992;130:303–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pettorossi VE, Della Torre G, Grassi S, Zampolini M, Capocchi G, Bruni R, Errico P. Visual and oculomotor functions (d’Ydewalle G, Van Rensbergen J, eds), Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1994. Influence of NMDA receptors in the optokinetic afternystagmus (OKAN). pp. 363–373. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sansom AJ, Darlington CL, Smith PF. Intraventricular injection of an NMDA antagonist disrupts vestibular compensation. Neuropharmacology. 1990;29:83–84. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimazu H, Precht W. Tonic and kinetic responses of cat’s vestibular neurons to horizontal angular acceleration. J Neurophysiol. 1965;28:991–1013. doi: 10.1152/jn.1965.28.6.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith PF, Darlington CL. The effects of N -methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists on vestibular compensation in the guinea pig: in vivo and in vitro studies. In: Berthoz A, Graf W, Vidal PP, editors. The head–neck sensory motor system. Oxford UP; New York: 1992. pp. 631–635. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith PF, de Waele C, Vidal PP, Darlington CL. Excitatory amino acid receptors in normal and abnormal vestibular function. Mol Neurobiol. 1992;5:369–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02935559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staubli U, Lynch G. Stable depression of potentiated synaptic responses in the hippocampus with 1–5 Hz stimulation. Brain Res. 1990;513:113–118. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91096-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi Y, Tsumoto T, Kubo T. N -methyl-d-aspartate receptors contribute to afferent synaptic transmission in the medial vestibular nucleus of young rats. Brain Res. 1994;659:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90895-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wexler EM, Stanton PK. Priming of homosynaptic long-term depression in hippocampus by previous synaptic activity. NeuroReport. 1993;4:591–594. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199305000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]