Abstract

Synaptic contacts formed by the axon of a neuron on its own dendrites are known as autapses. Autaptic contacts occur frequently in cultured neurons and have been considered to be aberrant structures. We examined the regular occurrence, dendritic distribution, and fine structure of autapses established on layer 5 pyramidal neurons in the developing rat neocortex. Whole-cell recordings were made from single neurons and synaptically coupled pairs of pyramidal cells, which were filled with biocytin, morphologically reconstructed, and quantitatively analyzed. Autapses were found in most neurons (in 80% of all cells analyzed; n = 41). On average, 2.3 ± 0.9 autapses per neuron were found, located primarily on basal dendrites (64%; 50–70 μm from the soma), to a lesser extent on apical oblique dendrites (31%; 130–200 μm from the soma), and rarely on the main apical dendrite (5%; 480–540 μm from the soma). About three times more synaptic than autaptic contacts (ratio 2.4:1) were formed by a single adjacent synaptically coupled neuron of the same type. The dendritic locations of these synapses were remarkably similar to those of autapses. Electron microscopic examination of serial ultrathin sections confirmed the formation of autapses and synapses, respectively, and showed that both types of contacts were located either on dendritic spines or shafts. The similarities between autapses and synapses suggest that autaptic and synaptic circuits are governed by some common principles of synapse formation.

Keywords: autapses, somatosensory cortex, layer 5 pyramidal neurons, whole-cell patch clamp, biocytin, camera lucida reconstruction

Chemical synapses are the predominant structures for the communication between neurons. It has, however, been found that neurons also form synapses with themselves, the so-called autapses, a term originally introduced by Van der Loos and Glaser (1972). They reported that 6 of 12 pyramidal neurons in the adult rabbit visual cortex, stained by the Golgi method, established 1–4 autapses. The existence of autapses has since then been well established in numerous cell types in different brain regions and in a wide range of vertebrate and invertebrate species (Held, 1897; Chan-Palay, 1971; Scheibel and Scheibel, 1971; Shkol’nik-Jarros, 1971; DiFiglia et al., 1976;Karabelas and Purpura, 1980; Preston et al., 1980; Kuffler et al., 1987; Shi and Rayport, 1994; Tamas et al., 1995). Despite these anatomical reports, the physiological significance of autapses has largely been disregarded. This may be attributable, in part, to their abundance under culture conditions, which has led several investigators to consider autapses as aberrant structures (see Furshpan et al., 1976,1986; Landis, 1976; Bekkers and Stevens, 1991; Segal, 1991, 1994).

In the course of experiments designed to investigate morphological and physiological properties of uni- and bidirectionally coupled layer 5 pyramidal neurons, we found regularly (92% of all coupled neurons) autaptic contacts formed by layer 5 pyramidal neurons in the neocortex. This led us to perform a quantitative anatomical investigation of the number, frequency, and distribution of autapses established by these neurons. In addition to the coupled cell pairs, we filled 15 single layer 5 pyramidal neurons to establish their autaptic contacts. The results indicate that autaptic contacts of layer 5 pyramidal cells were formed mainly on specific dendritic branches and that these dendritic locations were similar to those of synaptic contacts formed with neighboring neurons of the same class.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Slice preparation and recording. Wistar rats (13–15 d old) were rapidly decapitated, and neocortical slices (sagittal sections; 300 μm thick) were cut on a vibratome in iced extracellular solution. The right hemisphere only was placed on a block mounted at an angle of 30° such that the blade would cut from the upper (dorsal) border of the neocortex toward the lower (ventral) border and down toward the midline. With this cut, the slices contained the somatosensory cortex (Paxinos et al., 1991) as revealed by Nissl staining of some sections. Slices were incubated for 30 min at 35°C and then at room temperature (20–22°C) until they were transferred to the recording chamber (32–34°C). The extracellular solution contained (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 glucose, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm MgCl2. Layer 5 pyramidal neurons from the somatosensory cortical area were identified using infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) microscopy on an upright microscope (Zeiss-Axioplan, fitted with 40× W/0.75 numerical aperture objective, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) as described previously (Stuart et al., 1993). Somatic whole-cell recordings (15–25 MΩ access resistance) were obtained (200 μsec sampling rate; filtered at 3 kHz), and signals were amplified using combinations of Axoclamp 2B (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), EPC-9, or EPC-7 (List Electronic, Darmstadt, Germany) amplifiers. Neurons were recorded with pipettes containing (in mm): 100 K-gluconate, 20 KCl, 4 ATP-Mg, 10 phosphocreatine, 50 U/ml creatine phosphokinase, 0.3 GTP, 10 HEPES (pH 7.3, 310 mOsm). In 60 cases, 0.5% biocytin (Sigma, Munich, Germany) was added to the pipette solution. Neurons were filled with biocytin by passive diffusion during 1–4 hr of recording. Neurons typically had resting membrane potentials of −60 ± 2 mV. Of the different types of layer 5 cells, particularly large pyramidal neurons (soma sizes ∼15–25 μm, vertical diameter) were examined. These neurons are characterized by a thick apical dendrite (4–6 μm in diameter 20 μm from the soma center and 2 μm in diameter when traversing layer 2/3) and form an extensive tuft of terminal dendrites in layer 1. The chosen pairs were vertically separated no >50 μm from each other and were up to 80 μm below the surface of the slice.

Histological procedures. After recording, slices containing a single cell or pairs of neurons were fixed in cold 100 mm phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4) containing 1% paraformaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde. Twelve to 24 hr after fixation, slices were rinsed several times for 10 min each in 100 mm PB. To block endogenous peroxidases, slices were transferred into phosphate-buffered 3% H2O2 for 30 min. After thorough washing in 100 mm PB, sections were run through an ascending series of dimethylsulfoxide at the following concentrations: 5, 10, 20, and 40%, diluted in 100 mm PB (30 min for each step). After five to six rinses in 100 mm PB (10 min for each step), sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in avidin–biotin–horseradish peroxidase according to the manufacturer’s protocol (ABC-Elite, Camon, Wiesbaden, Germany). Thereafter, sections were washed several times in 100 mm PB and developed under visual control using a bright-field microscope (Zeiss Axioskop) until all processes of the cell were clearly visible (usually after 2–4 min). The reaction was stopped by transferring the sections into cold 100 mm PB. After thorough washing in the same buffer, slices were kept at 4°C overnight in the same solution while shaking. To enhance the staining contrast, slices were post-fixed for 1 hr in 0.5% phosphate-buffered osmium tetroxide (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and counterstained in 1% uranylacetate. After several rinses in 100 mm PB, sections were flattened between a glass slide and a coverslip and then dehydrated through an ascending series of ethanol in small glass vials. After two 10 min washes in propylene oxide (Merck, Darmstadt), slices were flat-embedded in Epon (Fluka, Germany) between coated glass slides. After polymerization, representative examples of well filled large layer 5 pyramidal neurons were photographed (Olympus BX-50) and drawn with a drawing tube at a final magnification of 480× using a 40× objective lens. These drawings formed the basis for our quantitative analysis. Subsequent electron microscopy was performed on selected pairs of neurons (n = 5). Serial sections were cut with an ultramicrotome (Leitz UItracut, Hamburg, Germany) and analyzed for autaptic contacts using a Zeiss EM 10 electron microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Quantitative morphological analysis. Only neurons with no obvious dendritic and axonal truncations were included in the sample (n = 41). The following morphological parameters were quantitatively analyzed: (1) location of the soma within layer 5; (2) soma diameter (length and width); (3) number and maximal span of dendritic field of basal, apical oblique, and terminal tuft dendrites; (4) the distances from the soma to the first bifurcation of the apical dendrite; and (5) number and maximal extent of horizontal and vertical axonal collaterals. Furthermore, the number and distance from the soma were determined for autaptic (n = 69) and synaptic (n = 106) contacts on the main apical dendrite, on basal dendrites, and on oblique dendrites of different orders, and for the terminal tuft (distances measured along dendrites). For all data, the mean ± SD was calculated.

RESULTS

Whole-cell recordings from single and from synaptically coupled pyramidal neurons

Whole-cell recordings were made from single neurons and pairs of adjacent layer 5 pyramidal neurons as described in Materials and Methods. All neurons had comparable current–voltage responses, were discharging with a burst of action potentials (APs) followed by slow accommodation, and had passive membrane properties comparable to those described by Mason and Larkman (1990) for thick-tufted layer 5 pyramidal neurons. Qualitative examination of the morphology of 15 single and 45 pairs of neurons filled with biocytin revealed that the IR-DIC method of identifying thick-tufted layer 5 pyramidal neurons was correct in every case. Quantification of the dendritic and axonal morphology of 41 neurons revealed that these neurons had similar morphological features, suggesting that they belonged to a homogeneous class of thick-tufted neurons comparable to those described morphologically and physiologically by Chagnac-Amitai et al. (1990),Larkman and Mason (1990), and Kasper et al. (1994a). Unitary EPSPs ranging from 50 μV to >6 mV (mean 1.3 ± 1.1, n = 172), which were mediated by both AMPA receptors (AMPA-Rs) and NMDA receptors (NMDA-Rs), were recorded from pairs of adjacent neurons.

Morphology of layer 5 pyramidal neurons

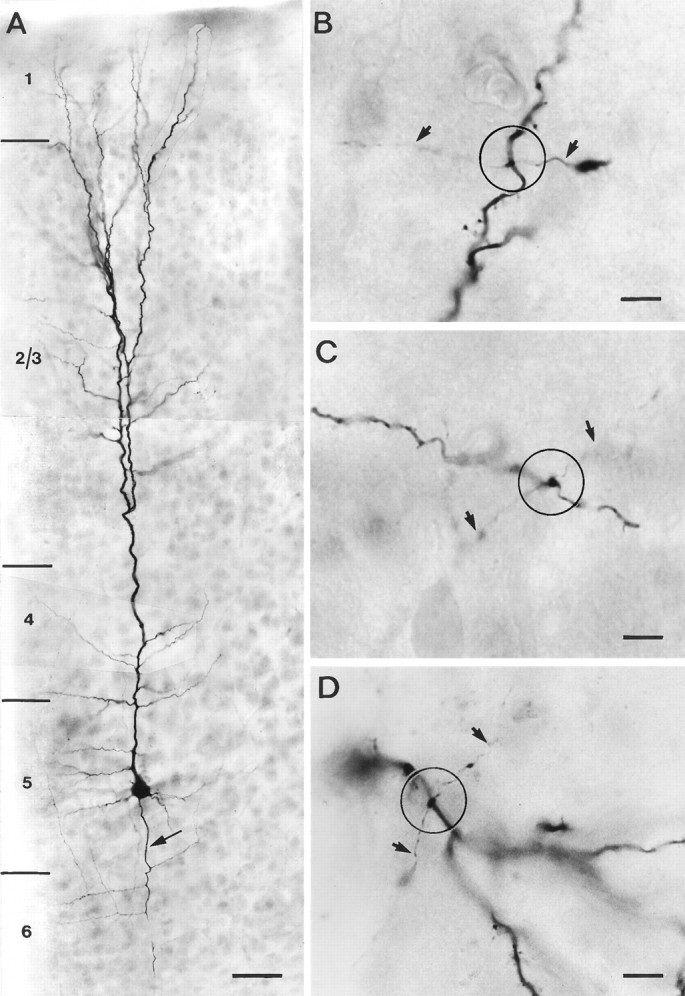

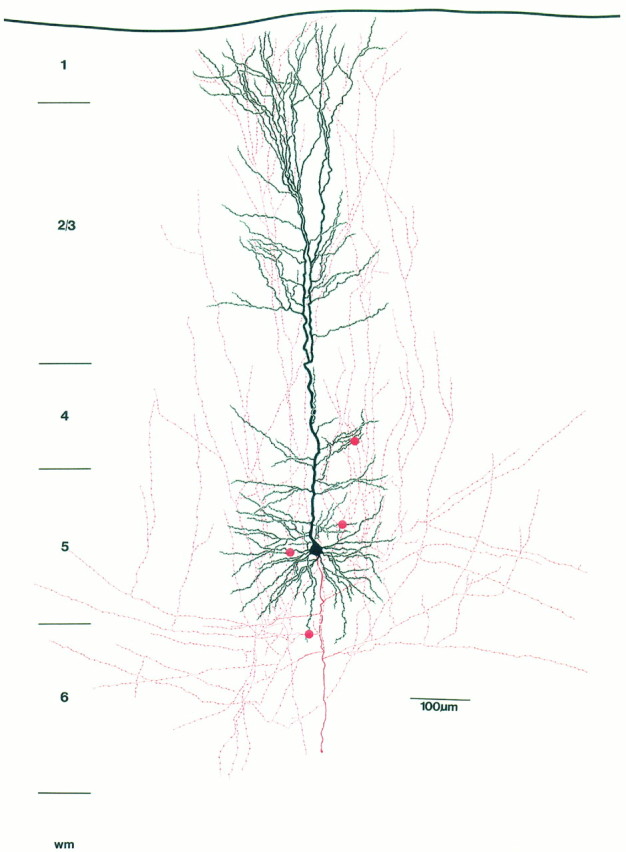

Whole-cell recordings were obtained from 15 single neurons filled with biocytin that were subsequently processed for light microscopy. The light microscopic analysis revealed that recordings were obtained only from thick-tufted layer 5 pyramidal neurons. A representative example of a neuron is shown in Figure1A and as a camera lucida reconstruction in Figure 2. The somata of the thick-tufted layer 5 pyramidal neurons were found mainly in the middle-to-upper part of layer 5. The main apical dendrites of the neuron project toward layer 1, giving rise to 8–15 apical oblique dendrites, primarily within layers 4 and 5. The main apical dendrite passes through layer 2/3 and then divides to form an extensive terminal tuft in layer 1 (mean tuft span, 268.3 ± 68.3 μm;n = 15). A few neurons (5 of 15) show a bifurcation of the main apical dendrite at the border of layers 4 and 2/3, respectively (Figs. 1A, 2). Dendrites that ascend further give rise to a terminal tuft in layer 2/3 (Figs.1A, 2). The main axon emerges either directly from the soma or from one of the primary basal dendrites and gives rise to several long horizontal collaterals (4.9 ± 1.7), mainly in layers 5 and 6. Some of these axon collaterals could be followed for up to 2.5 mm from the soma. The total arbor of horizontal axonal collaterals extended ∼600–700 μm on each side of the soma with several ascending and descending higher-order branches (Fig. 2). Vertical axon collaterals (5.3 ± 0.9) ascended on both sides of the main apical dendrite. Some of those could be followed terminating in layer 1 (Fig.2).

Fig. 1.

Representative example of a single-labeled layer 5 pyramidal neuron. A, Low magnification of a thick-tufted pyramidal neuron filled with biocytin during the recording. The main apical dendrite bifurcates in layer 2/3 giving rise to an extensive terminal tuft in layer 1. The main axon emerges directly from the soma and is indicated by an arrow. B–D, Representative examples of en passant autaptic contacts (within theopen circles) established on a secondary basal (B), tertiary basal (C), and secondary oblique (D) dendrite. Axonal collaterals are marked byarrows. Scale bar in A, 100 μm;B–D, 50 μm.

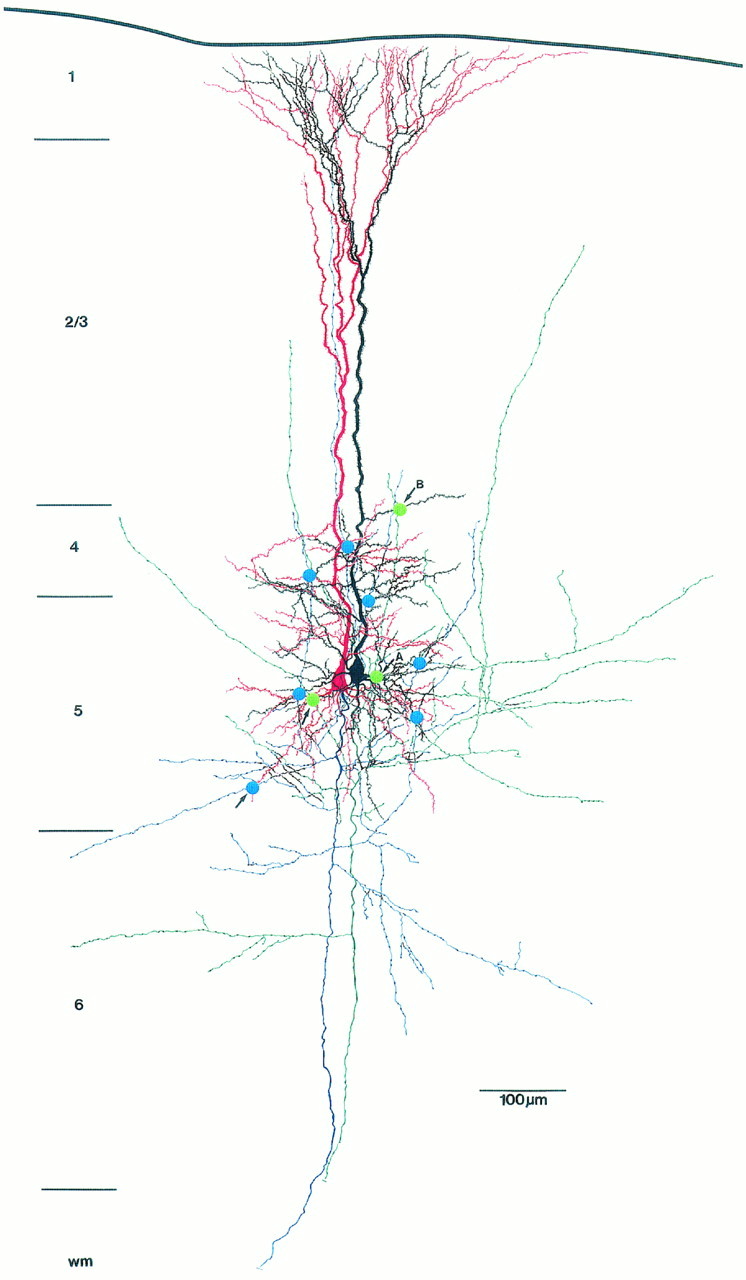

Fig. 2.

Camera lucida reconstruction of the pyramidal neuron shown in Figure 1. For better visualization, the dendritic morphology of the neuron is drawn in black, whereas the axonal arborization is drawn in red. The red dotsindicate autaptic contacts established onto basal and oblique dendrites by the axon. Note extensive vertical axonal collaterals, some of which could be followed up to layer 1.

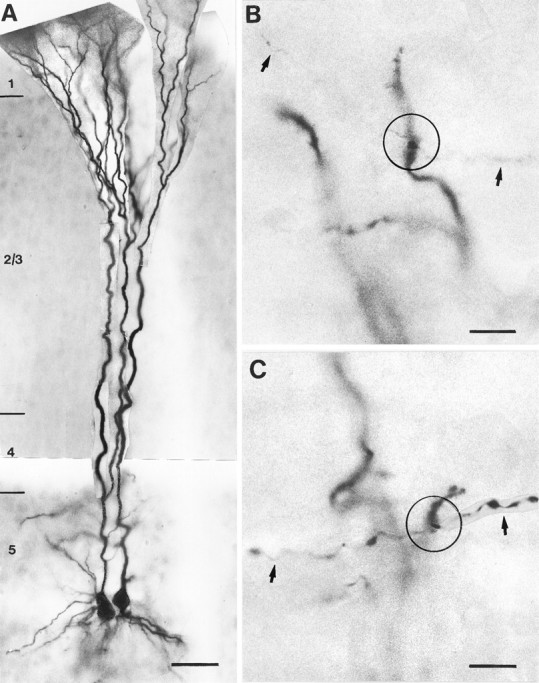

A total of 90 synaptically coupled and biocytin-filled neurons (45 pairs) were also processed for light microscopy and electron microscopy. The light microscopic analysis revealed that recordings were obtained only from pairs of neurons that resembled those described above. A representative example of a biocytin-filled, unidirectionally coupled pair of neurons is shown in Figure 3Aat low magnification.

Fig. 3.

Representative example of a unidirectionally coupled pair of thick-tufted layer 5 pyramidal neurons filled with biocytin. A, Low magnification of the pair of neurons. The neuron on the left shows a bifurcation of the main apical dendrite in layer 5. B, Representative example of an autaptic contact (open circle) onto a secondary basal dendrite. C, Autaptic contact (open circle) on a secondary apical oblique dendrite. Axonal collaterals are indicated byarrows. Scale bar in A, 50 μm; B–C, 25 μm.

Quantitative analysis of autaptic contacts established by the axons of a single-labeled layer 5 pyramidal neuron

All neurons (n = 15) were analyzed and potential autaptic contacts (n = 27) were photographed (Fig.1B–D) and marked on the camera lucida drawings as shown in Figure 2. The results of the quantitative analysis are summarized in Table 1. Putative autapses were observed in 10 of 15 pyramidal neurons (66.7%). Autapses were found exclusively on dendrites, with an average of 2–3 autapses per neuron (mean 2.6 ± 0.5; range 1–4). Their location on the dendritic tree varied from neuron to neuron; however, the majority of autapses were more frequently located on the secondary and tertiary basal dendrites (74%), to a lesser extent on primary and secondary apical oblique dendrites (26%), but none on the main apical dendrite (Table 1, see also Fig. 5A). Autapses established on basal dendrites were located within 100 μm from the soma and even autapses found on the apical oblique dendrites were situated relatively close to the soma (Table 1). Most autaptic contacts were established by second- and third-order axon collaterals.

Table 1.

Distribution pattern of autapses on the dendritic tree of single-labeled layer 5 pyramidal neurons

| Autapses | ||

|---|---|---|

| % occurrence of the total | Distance from the soma (μm) | |

| Basal 1° | – | – |

| Basal 2° | 44 (n = 12) | 59.1 ± 28.9 |

| Basal 3° | 30 (n = 8) | 73.2 ± 10.3 |

| Basal 4° | – | – |

| Oblique 1° | 4 (n = 1) | 132.2 |

| Oblique 2° | 22 (n = 6) | 147.9 ± 38.2 |

| Oblique 3° | – | – |

| Main apical | – | – |

| Terminal tuft | – | – |

Percentages of occurrence and distance from the cell body (mean ± SD) of autapses in 10 neurons out of a total of 15 cells analyzed. In five neurons, no autaptic contacts were found. The total number of autapses was 27.

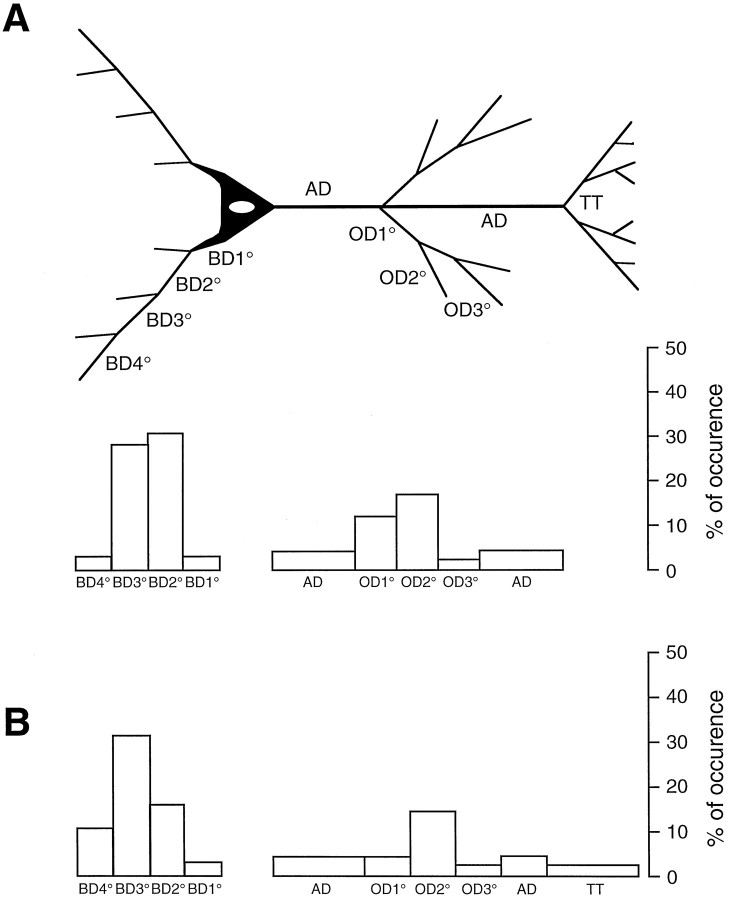

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram summarizing the distribution of autaptic and synaptic contacts at different dendritic locations.A, The distribution of autaptic contacts established by single and uni- and bidirectionally coupled layer 5 pyramidal neurons is given for 69 autapses. B, For comparison, the distribution of synaptic contacts established by uni- and bidirectionally coupled neurons is given for 106 synaptic contacts. Note the similar distribution of autaptic and synaptic contacts with two prominent peaks for the basal and apical oblique dendrites.BD1°–BD4°, Basal dendrites of increasing order;AD, apical dendrite; OD1°–OD3°, oblique dendrites of increasing order; TT, terminal tuft.

Quantitative light microscopic analysis of synaptic and autaptic contacts established by coupled layer 5 pyramidal neurons

Quantitative analysis of the number and dendritic distribution of synaptic (n = 106) and autaptic (n = 42) contacts was performed on 13 pairs of neurons (7 uni- and 6 bidirectionally coupled neurons). The neurons were reconstructed with the aid of a camera lucida, and potential synaptic and autaptic contacts were photographed (Fig. 3B,C) and marked on camera lucida drawings as shown in Figure 4. The results of the quantitative analysis are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. Potential autapses were observed in 24 out of a total of 26 pyramidal neurons (92.3%) that were also synaptically coupled with a neighboring neuron. A total number of 148 potential contacts were found in the synaptically coupled 26 neurons. Of these potential contacts, 106 (72%) were synaptic contacts formed on the coupled neurons, and 42 (28%) turned out to be autaptic contacts formed on the dendrites (ratio of synapses:autapses 2.4:1). For a single neuron, the number of synaptic contacts was 5.6 ± 1.1 (range 2–8), and the number of autaptic contacts was 2.1 ± 1.0 (range 0–4; see Table 2) and thus slightly lower when compared with autapses found on single-labeled neurons (see also Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Camera lucida reconstruction of a unidirectionally coupled pair of thick-tufted pyramidal neurons located in the middle of layer 5. The dendritic morphology of the sending neuron is drawn inred and its axonal arborization is drawn in blue. The dendritic morphology of the receiving neuron is drawn inblack and its axonal arborization is drawn ingreen. The blue and green dotsindicate synaptic or autaptic contacts, respectively, established by either the blue or the green axon. In this figure, autapses are marked by arrows. The sending neuron establishes six synaptic contacts at different locations on the dendrites of the target neuron. The axon of the receiving neuron forms three autapses on its own dendritic tree at different locations, whereas the sending neuron establishes only a single contact on one of its basal dendrites. A and B label the autaptic contacts shown in Figure 6.

Table 2.

Comparison of the frequency of occurrence of synaptic and autaptic contacts on coupled layer 5 pyramidal neurons

| Unidirectionally coupled neurons | Bidirectionally coupled neurons | Autapses on single neurons | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synapses | Autapses | Synapses | Autapses | ||

| Number of contacts per neuron | 5.7 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 0.5 |

| % of the total number of contacts | 75.5 | 24.5 | 72.5 | 27.5 | 100 |

| % contacts on the same dendrite | 25.0 | 0 | 22.6 | 8.0 | 5.5 |

Number of synaptic and autaptic contacts of uni- and bidirectionally coupled neurons is given for 13 cell pairs (mean ± SD). The number of autapses found on single-labeled neurons is added for comparison.

Autapses were found exclusively on dendrites. Most autapses were located within 100 μm from the soma, but a few were located nearly 500 μm away from the cell body (Table 3). Their location on the dendritic tree was also variable, but most autapses were located on the basal dendrites (60%), to a lesser extent on apical oblique dendrites (33%), and rarely on the main apical shaft (7%; Table 3). Furthermore, of the autapses located on basal dendrites, nearly 90% were found on secondary and tertiary branches. In general, most autaptic contacts were established by second- and third-order dendrites, which is in line with the results found for single pyramidal neurons.

Table 3.

Distribution patterns of synapses and autapses on uni- and bidirectionally coupled layer 5 pyramidal neurons

| Synapses | Autapses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % occurrence of the total | Distance from soma (μm) | % occurrence of the total | Distance from soma (μm) | |

| Basal 1° | 2 (n = 2) | 44.0 ± 35.2 | 5 (n = 2) | 69.4 ± 45.9 |

| Basal 2° | 16 (n = 17) | 75.1 ± 35.3 | 21 (n = 9) | 67.6 ± 36.8 |

| Basal 3° | 35 (n = 37) | 82.8 ± 25.2 | 31 (n = 13) | 71.9 ± 5.4 |

| Basal 4° | 10 (n = 11) | 98.3 ± 27.3 | 2 (n = 1) | 58.3 |

| Oblique 1° | 7 (n = 7) | 131.3 ± 87.4 | 19 (n = 8) | 202.6 ± 103.4 |

| Oblique 2° | 15 (n = 16) | 151.1 ± 48.0 | 12 (n = 5) | 158.6 ± 42.1 |

| Oblique 3° | 6 (n = 6) | 145.3 ± 45.3 | 3 (n = 1) | 127.3 |

| Main apical | 7 (n = 7) | 530.8 ± 116.3 | 7 (n = 3) | 490.6 ± 19.8 |

| Terminal tuft | 2 (n = 3) | 796.9 ± 98.3 | – | – |

Percentages and distances from the cell body of synaptic (n = 106) and autaptic contacts (n = 42) are given for 13 cell pairs.

The dendritic locations of putative synapses and autapses were remarkably similar (Tables 1, 3). The results are summarized in Figure5. Both synaptic and autaptic contacts show two peaks in the distribution of their locations. One peak at the basal dendrites and a smaller peak at the apical oblique dendrites with a high tendency for autapses (Fig. 5A) and synapses (Fig. 5B) to form on secondary and tertiary basal dendrites.

Electron microscopic analysis of synaptic and autaptic contacts established by layer 5 pyramidal neurons

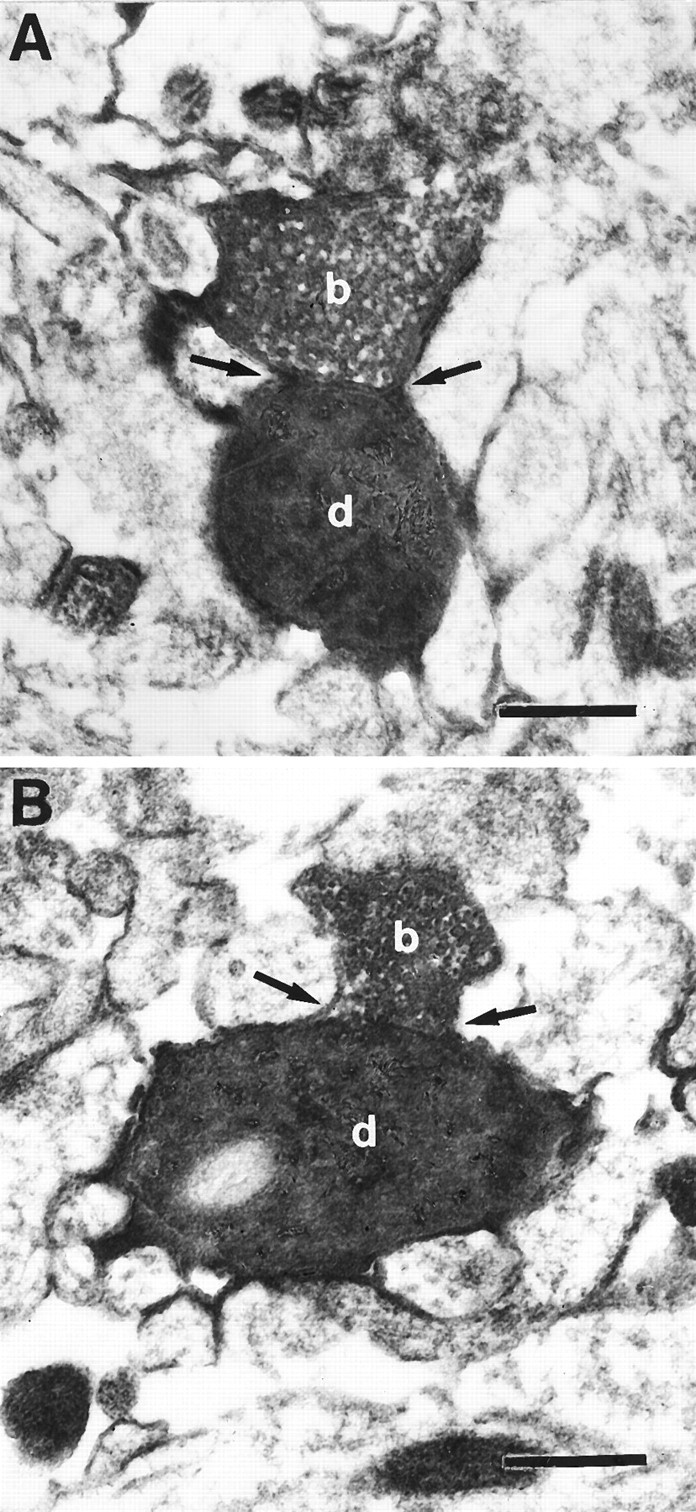

Light microscopic analysis can only reveal potential synaptic and autaptic contact sites. Serial electron microscopic (EM) analysis was used to confirm the putative synaptic and autaptic contacts and to obtain an approximation of the accuracy of the light microscopic assessment of potential contacts. In one cell pair, all four putative autaptic contacts (as marked in Fig. 4 by arrows) could be confirmed at the EM level. Two of these contacts are shown in Figure6. In another pair of coupled neurons, a total of 14 potential synaptic and 4 autaptic contacts were seen at the light microscopic level. Of these putative contacts, 11 synapses and 2 autapses could be confirmed with the electron microscope. The remaining putative contacts did not fulfill our criteria of synaptic junctions, such as vesicle accumulation in the presynaptic bouton, identifiable membrane specializations, and the presence of electron-dense material in the synaptic cleft. Of the six autapses identified at the EM level, four turned out to be axodendritic contacts (Fig. 6) and two were axospinous contacts.

Fig. 6.

Electron micrographs of axodendritic autaptic contacts. Two examples from the pair of neurons illustrated in Figure 4are shown (arrows in A and B) One autaptic contact is established on a basal dendritic branch by one of the blue axonal collaterals (A); the other one was formed on an apical oblique branch by one of the green axonal collaterals (B). Arrows point to synaptic cleft.b, Synaptic bouton; d, dendrite. Scale bar, 1 μm.

DISCUSSION

The frequency and dendritic distribution of synaptic and autaptic contacts established by layer 5 pyramidal neurons was investigated in single-labeled as well as uni- and bidirectionally coupled, biocytin-filled neurons of the developing rat neocortex. Nearly 80% of the neurons established autapses that were located exclusively on dendrites. These autapses tended to form at specific dendritic locations, in particular on secondary and tertiary branches of basal dendrites and, to a lesser extent, on apical oblique dendrites. We have shown that the distribution pattern of autapses is remarkably similar to that of synapses onto adjacent layer 5 pyramidal neurons of the same type (compare Fig. 5, A and B). This suggests that the formation of autapses and synapses of layer 5 pyramidal neurons is governed by some common principles.

The present approach of using the IR-DIC-guided identification of single and coupled pairs of neurons enabled a systematic examination of a specific autaptic and synaptic pathway within a homogeneous group of neurons. A limitation of this approach, however, is that recordings from neurons near the surface of the slice may result in an underestimation in the number of contacts. On the other hand, it is unlikely that the number of light microscopically identified autaptic and synaptic contacts is significantly overestimated, because almost all contacts subjected to EM analysis could be confirmed at the electron microscopic level. Furthermore, it is possible that small synaptic and autaptic contacts masked by thick dendrites are not included in the sample because only light microscopically visible contacts were counted. Based on these considerations, the overall error is likely to be an underestimation of the number of autapses and synapses.

The present study extends previous reports describing the existence of autapses in various brain regions and species (Held, 1897; Chan-Palay, 1971; Scheibel and Scheibel, 1971; Shkol’nik-Jarros, 1971; DiFiglia et al., 1976; Karabelas and Purpura, 1980; Preston et al., 1980; Kuffler et al., 1987; Shi and Rayport, 1994; Tamas et al., 1995) by showing that there is a high frequency of autaptic contacts in pyramidal neurons of the neocortex, which suggests that these autapses are a common feature of neurons.

A high frequency of occurrence and high numbers of autapses have been primarily reported in cultures, for example, in cultures of chicken spinal ganglion cells (Crain, 1971), sympathetic ganglion cells cocultured with myocytes (Furshpan et al., 1976, 1986), and cultured hippocampal neurons (Landis, 1976; Bekkers and Stevens, 1991; Segal, 1991, 1994). In culture, neurons grow under artificial conditions, and the frequent occurrence of autapses has been regarded as an artifact. However, a high number of autapses has also been reported for substantia nigra neurons (Karabelas and Purpura, 1980) and for somata and dendrites of basket cells in slices of cat visual cortex (Tamas et al., 1995). Therefore, autapses may be a more common feature of neurons than previously thought.

Whether autapses serve any function is still unclear. We have performed experiments on single layer 5 pyramidal neurons in an attempt to reveal the autaptic EPSPs. In these experiments, voltage traces of single action potentials (APs) initiated with short current pulses (700 μsec) were subtracted from voltage traces after application of the AMPA receptor blocker, 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX). The membrane time constant of the neuron, however, increased in the presence of CNQX, probably because background synaptic activity was removed, which prevented the dectection of EPSPs by subtraction (an inhibitory postsynaptic potential-like event was revealed). It therefore seems unlikely that the autaptic event can be isolated in the brain-slice preparation from the dominating AP. Indeed, from estimates of AP propagation time in the axon, the synaptic delay, and the velocity of AP backpropagation in the dendrite to the synapse, it seems likely that the autaptic event would occur ∼100 μsec after the onset of the backpropagating AP at the autaptic site.

It has, however, been suggested that autapses enable “self-excitation” and “self-sensing” of neurons (Held, 1897). This hypothesis was extended by Glaser and van der Loos (1972), who assumed that autapses might be the substrate of a gating mechanism such that the neuron’s output can control its input. Autapses have also been implicated in mediating part of the depolarization or hyperpolarization after action potentials, and therefore have been considered as a potential means of regulating excitability (Bekkers and Stevens, 1991; Segal, 1991; Shi and Rayport, 1994; Tamas et al., 1995). However, even with a much higher number of inhibitory autaptic contacts formed by a basket cell axon (on average, 6 autapses per neuron), no physiological evidence for a functional role could be presented byTamas et al. (1995).

To understand the functional significance of autapses within a given pathway, it is first necessary to establish their frequency, number, and precise dendritic locations. Previous studies have not provided these details. To further investigate their functional significance, it is necessary to establish the physiological properties of autapses as well as the potential importance of their preferential location on certain dendritic segments. If one assumes that autapses are of functional significance and have functional properties similar to synapses, then the mean voltage contribution of these autapses would be <500 μV. Although this voltage contribution is not likely to affect the membrane potential voltage of the neuron at the soma, especially not during afterhyperpolarization, the possibility that autapses contribute more significantly to local dendritic voltage changes cannot be excluded. Finally, an increase in autapses in pathological conditions may lead to hyperexcitability within a given neuronal circuit. Thus, an increased number of recurrent, supragranular mossy fiber collaterals innervating their cells of origin, the dentate granule cells (Frotscher and Zimmer, 1983), has been found in hippocampal tissue exhibiting abnormal functional activity (Sutula et al., 1988).

Footnotes

This work was supported by the “von Helmholtz-Programm” of the Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft, Forschung, und Technologie (J.L.) and the Minerva Foundation (H.M.). We thank Drs. P. Jonas and M. Segal for their comments on this manuscript. We are also grateful to S. Nestel, B. Joch, E. Dauer, and M. Winter for technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Joachim Lübke, Anatomisches Institut der Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg, Albertstrasse 17, D-79104 Freiburg, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bekkers JM, Stevens CF. Excitatory and inhibitory autaptic currents in isolated hippocampal neurons maintained in cell culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7834–7838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chagnac-Amitai Y, Luhmann HJ, Prince DA. Burst generating and regular spiking layer 5 pyramidal neurons of rat neocortex have different morphological features. J Comp Neurol. 1990;296:598–613. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan-Palay V. The recurrent collaterals of Purkinje cell axons: a correlated study of rat’s cerebellar cortex with electron microscopy and the Golgi-method. Z Anat Entwicklungsgesch. 1971;134:200–234. doi: 10.1007/BF00519300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crain SM. Intracellular recordings suggesting synaptic functions in chick embryo spinal sensory ganglion cell isolated in vitro. Brain Res. 1971;26:188–191. [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiFiglia M, Pasik P, Pasik T. A Golgi-study of neuronal types in the neostriatum of monkeys. Brain Res. 1976;114:245–256. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90669-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frotscher M, Zimmer J. Lesion-induced mossy fibers to the molecular layer of the rat fascia dentata: identification of postsynaptic granule cells by the Golgi-EM technique. J Comp Neurol. 1983;215:299–311. doi: 10.1002/cne.902150306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furshpan EJ, MacLeish PR, O’Lague PH, Potter DD. Chemical transmission between rat sympathetic neurons and cardiac myocytes developing in microcultures: evidence for cholinergic, adrenergic, and dual-function neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:4225–4229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furshpan EJ, Landis SC, Matsumoto SG, Potter DD. Synaptic functions in rat sympathetic neurons in microcultures. I. Secretion of norepinephrine and acetylcholine. J Neurosci. 1986;6:1061–1079. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-04-01061.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Held H. Beiträge zur Struktur der Nervenzellen und ihrer Fortsätze. Arch Anat Physiol. 1897;2:204–294. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karabelas AB, Purpura DP. Evidence for autapses in the substantia nigra. Brain Res. 1980;200:467–473. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90935-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasper EM, Larkman AU, Lübke J, Blakemore C. Pyramidal neurons in layer 5 of the rat visual cortex. I. Correlation among cell morphology, intrinsic electrophysiological properties, and axon targets. J Comp Neurol. 1994a;339:459–474. doi: 10.1002/cne.903390402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuffler DP, Nicholls J, Drapeau P. Transmitter localization and vesicle turnover at a serotoninergic synapse between identified leech neurons in culture. J Comp Neurol. 1987;256:516–526. doi: 10.1002/cne.902560404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landis SC. Rat sympathetic neurons and cardiac myocytes developing in microcultures: corellation of the fine structure of endings with neurotransmitter function in single neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:4220–4224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.4220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larkman AU, Mason A. Correlation between morphology and electrophysiology of pyramidal neurons in slices of rat visual cortex. I. Establishment of cell classes. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1407–1414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-05-01407.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mason A, Larkman AU. Correlation between morphology and electrophysiology of pyramidal neurons in slices of rat visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1415–1428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-05-01415.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paxinos G, Törk T, Tecott LH, Valentino KL. Academic; San Diego: 1991. Atlas of the developing rat brain. . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preston RJ, Bishop GA, Kitai ST. Medium spiny neurons projection from the rat striatum: an intracellular horseradish peroxidase study. Brain Res. 1980;183:253–263. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90462-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheibel ME, Scheibel AB. Inhibition and the Renshaw cell. A structural critique. Brain Behav Evol. 1971;4:53–93. doi: 10.1159/000125424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Segal MM. Epileptiform activity in microcultures containing one excitatory hippocampal neuron. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65:761–770. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.4.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segal MM. Endogenous bursts underlie seizure like activity in solitary excitatory hippocampal neurons in microcultures. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1874–1884. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi W-X, Rayport S. GABA synapses formed in vitro by local axon collaterals of nucleus accumbens neurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4548–4560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04548.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shkol’nik-Jarros EG. Plenum; New York: 1971. Neurons and interneuronal connections of the central visual system. . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuart GJ, Dodt H-U, Sakmann B. Patch-clamp recordings from the soma and dendrites of neurons in brain slices using infrared video microscopy. Pflügers Arch. 1993;423:511–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00374949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sutula T, Xiao-Xian H, Cavazos J, Scott G. Synaptic reorganization in the hippocampus induced by abnormal functional activity. Science. 1988;239:1147–1150. doi: 10.1126/science.2449733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamas G, Buhl EH, Somogyi P (1995) High degree of self-innervation by GABAergic basket cells in the visual cortex of the cat as revealed in vitro. J Physiol PC31.

- 26.Van der Loos H, Glaser EM. Autapses in neocortical cerebri: synapses between a pyramidal cell’s axon and its own dendrites. Brain Res. 1976;48:355–360. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]