Abstract

Objective

To evaluate a potential reduction in injury related healthcare costs when using the ‘11+ Kids’ injury prevention programme compared with a usual warmup in children’s football.

Methods

This cost effectiveness analysis was based on data collected in a cluster randomised controlled trial over one season from football teams (under-9 to under-13 age groups) in Switzerland. The intervention group (INT) replaced their usual warmup with ‘11+ Kids’, while the control group (CON) warmed up as usual. Injuries, healthcare resource use and football exposure (in hours) were collected prospectively. We calculated the mean injury related costs in Swiss Francs (CHF) per 1000 hours of football. We calculated the cost effectiveness (the direct net healthcare costs divided by the net health effects of the ‘11+ Kids’ intervention) based on the actual data in our study (trial based) and for a countrywide implementation scenario (model based).

Results

Costs per 1000 hours of exposure were CHF228.34 (95% CI 137.45, 335.77) in the INT group and CHF469.00 (95% CI 273.30, 691.11) in the CON group. The cost difference per 1000 hours of exposure was CHF−240.66 (95%CI −406.89, −74.32). A countrywide implementation would reduce healthcare costs in Switzerland by CHF1.48 million per year. 1002 players with a mean age of 10.9 (SD 1.2) years participated. During 76 373 hours of football, 99 injuries occurred.

Conclusion

The ‘11+ Kids’ programme reduced the healthcare costs by 51% and was dominant (ie, the INT group had lower costs and a lower injury risk) compared with a usual warmup. This provides a compelling case for widespread implementation.

Keywords: children, football, soccer, injury prevention, FIFA 11+ Kids

Introduction

A physically active lifestyle and active participation in sport at a young age can promote lifelong healthy active behaviour.1–3 Football (soccer) is one of the most popular sports worldwide, and a suitable physical activity setting for children.4 Although there are many health benefits of sport participation, sport is the main cause of injury in children and adolescents.5–9 Injuries in young athletes can reduce current and future involvement in physical activity and lead to substantial healthcare and societal costs.10 11 This economic burden associated with injury involves medical, financial and human resources at many levels.11–13

The football specific warmup and injury prevention programme, ‘11+’, prevents injuries in recreational youth football.14–17 There is, however, a dearth of data on sport injury prevention in children.18 Based on our epidemiological data,19 20 we developed and evaluated an injury prevention programme for children’s football (‘11+ Kids’).21 In a randomised controlled trial, this warmup programme reduced the overall injury risk in children’s football by 48% and the risk for severe injuries by 74%.22 Here we report the cost effectiveness study that ran alongside that randomised controlled trial.22

Our cost effectiveness analysis compared direct healthcare costs of the ‘11+ Kids’ intervention group with costs in a control group who undertook their usual warmup.22 The intervention was investigated from a societal perspective, considering all relevant costs and effects, regardless of who pays or who benefits from the effects.

Methods

Sample, design and data acquisition

We followed the CHEERS statement for the reporting of this cost effectiveness analysis.23 Study participants were boys and girls, aged 7–12 years, participating in the 2014/2015 football season (August to June). Boys and girls train and compete together in these age categories. Healthcare resource use was collected prospectively in the Swiss study arm of a cluster randomised controlled trial. This trial was conducted to test the efficacy of the ‘11+ Kids’ injury prevention programme compared with a regular warmup programme in children’s football. The study involved four countries (Switzerland, The Netherlands, Germany and the Czech Republic). The primary outcome was the potential reduction of all football related injuries. The study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02222025) complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee (Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz, EKNZ, approval No 2014–232). All children and their parents received written information about the project prior to the start of the study. Participation was voluntary and all parents of injured children gave their active consent. Study specific details of the randomised controlled trial are described in the original paper.22

Intervention

The intervention group (INT) used the ‘11+ Kids’ programme, replacing their usual warmup at the beginning of each training session throughout the season. The ‘11+ Kids’ is a 15 min warmup programme designed to prevent injuries in children’s football, consisting of seven different exercises each with five levels of difficulty.22 The exercises focus on dynamic stability, power, core strength and falling techniques. ‘11+ Kids’ has been proven to be efficacious in preventing injuries.22 Participants in the control group (CON) performed their usual warmup routine.

Outcome measures

Injury

During the football season, football related injuries that resulted in at least one of the following were recorded and followed-up by the research coordinators for up to 3 months following the end of the season19: (a) inability to complete the current match or training session and/or (b) absence from subsequent training sessions or matches and/or (c) injury requiring medical attention. Injury type, location and mechanism as well as time loss (ie, absence from sport participation) were documented via an internet based injury registration platform. Coaches entered injuries on a weekly basis. Directly after an injury was entered in the online system, study coordinators contacted coaches, parents and injured children to get more details on the injuries using a standardised questionnaire. Injuries were followed-up on a weekly basis at least until the child was back in training. In the case of an injury, parents forwarded the medical diagnosis and cost relevant information to the study coordinators.

Healthcare resource use and costs

Costs considered included direct healthcare costs and intervention costs. Intervention costs included actual expenses for the printed manuals and the organisation of instruction courses for the coaches, and potential opportunity costs of coaches due to their attendance at the ‘11+ Kids’ instruction course (table 1, for further information see online supplementary material 1).24 We used the sum of these costs and the number of players to calculate the total intervention costs per player (ie, player season).

Table 1.

Intervention costs in the study and estimated costs for a countrywide implementation of ‘11+ Kids’

| Costs in the study | Countrywide implementation scenario* | |

| Costs for printing and delivering the ‘11+ Kids’ manual | ||

| Cost per unit | 7.22 | 4.05 |

| Total costs for the manuals | 267 | 21 463 |

| Costs for ‘11+ Kids’ education courses | ||

| Cost per course | 220 | 1940 |

| Total costs for the courses | 2200 | 515 070 |

| Website | ||

| Development costs | N/A | 12 000 |

| Maintenance per year | N/A | 4000 |

| Total costs for the website | N/A | 32 000 |

| Overall costs | ||

| Total intervention/implementation costs | 2467 | 568 533 |

| Total costs per player season | 4.02 | 1.94 |

All costs are reported in Swiss Francs (for additional information, see online supplementary material 2).

*Across Switzerland over a time horizon of 5 seasons.

N/A, not applicable.

bjsports-2018-099395supp001.docx (62KB, docx)

The healthcare resource use of injured players (ie, information on the number of visits to healthcare professionals, medical examinations, treatments and equipment used by injured players) was derived by contacting the parents of injured children via telephone. We applied the cost analysis from a healthcare perspective (direct costs). Standardised medical fees according to the national medical association (‘Tarmed’, V.1.08) enabled a precise estimation of the medical treatment costs of injuries.25 This approach has been applied previously and allowed for valuing the healthcare resources used (eg, visits to physicians, X-rays, casts).24 Out of pocket healthcare costs borne by the parents of injured players (eg, physical therapy, braces and visit to a chiropractor) were estimated based on the prices of various providers of such services and products. All costs are reported in Swiss Francs (CHF, 2015).

Projected costs and health effects for a nationwide implementation scenario of ‘11+ Kids’ in Switzerland (model based scenario)

In a further analysis, we estimated the costs of a nationwide implementation of ‘11+ Kids’ in Switzerland (table 1). These costs include expenses for printing and shipping the ‘11+ Kids’ manual, organisation of instruction courses to reach football coaches (including time expenditure for travel), loss of productivity during attendance of the course as well as the development and hosting of a website to provide the digital version of the manual over a time horizon of 5 seasons (see online supplementary material 1). We estimated a 50% turnover of coaches (ie, new coaches replacing coaches who retire/resign) over the course of 5 seasons. Therefore, we multiplied the costs for the manuals and the courses by an inflation factor of 1.5. The resulting overall costs for the printed manuals, education courses and the website were CHF568 533 over a 5 season period. Based on the actual number of players in children’s football in Switzerland (58 622 in the 2014/2015 season), this relates to CHF9.70 per player over a 5 season period and CHF1.94 per player season.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the mean cost per player (ie, player season) as the total cost in each group divided by the total number of players in each group, as well as the mean cost per injured player as the total cost in each group divided by the total number of injured players in each group. Further, we calculated the cost of injuries per 1000 hours of football exposure in each group. To obtain the corresponding 95% CI, we used non-parametric bootstrapping with 1000 samples to account for the skewed cost distributions.24

We calculated injury incidence density for both groups with corresponding 95% CI. Further, we analysed the time to event data using a mixed effects Cox model. The model accounted for clustering effects on team level and allowed analysis of multiple injuries to individual players while accounting for potential correlations on the intra-person level. We used age and age adjusted body height as covariates, as described previously.20 22

Cost effectiveness analysis

We calculated the differences in mean cost per player (ie, player season), mean cost per injured player and cost per 1000 hours of football exposure between the INT and CON groups. Differences in costs between the groups are presented as absolute cost differences (95% CI).

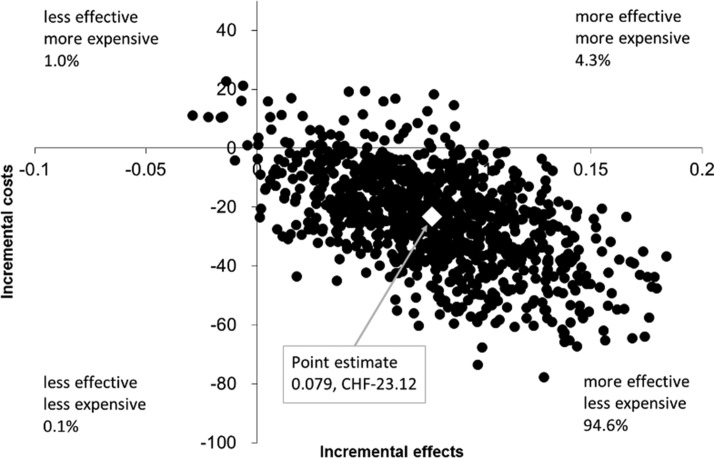

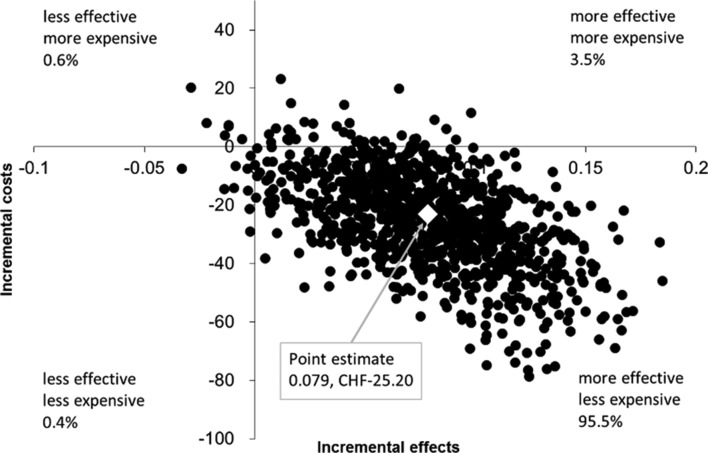

We estimated the incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) to summarise the cost effectiveness of ‘11+ Kids’ and created cost effectiveness planes (figures 1 and 2).24 26 The ICER is the difference in cost per player between the INT and CON groups, divided by the difference in the number of injuries per player between the INT and CON groups. We calculated the ICERs for the ‘trial based’ data (figure 1) and for the ‘model based’ (countrywide implementation) scenario (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Cost effectiveness plane presenting cost effect pairs in the ‘11+ Kids’ study (trial based data). Cost effect pairs were estimated using bootstrapping (1000 samples) for the difference in the costs and injury risk in the ‘11+ Kids’ intervention group versus the control group. Values in the southeast (dominant) quadrant indicate that the intervention group showed lower costs and lower injury incidence density. Data in the northwest quadrant (dominated) indicate that the intervention group showed higher costs and a higher injury incidence density.

Figure 2.

Cost effectiveness plane presenting model based data for a countrywide implementation of the ‘11+ Kids’. Cost effect pairs were estimated using bootstrapping (1000 samples) for the difference in the costs and injury risk in the ‘11+ Kids’ intervention group versus the control group. The figure shows simulated data for a countrywide implementation scenario in Switzerland over one football season. Values in the southeast (dominant) quadrant indicate that the intervention group showed lower costs and lower injury incidence density. Data in the northwest quadrant (dominated) indicate that the intervention group showed higher costs and a higher injury incidence density.

The cost effectiveness planes show four quadrants. Values in the southeast (dominant) quadrant indicate that the INT group showed lower costs and a lower injury incidence density. In contrast, the northwest quadrant (dominated) indicates that the intervention leads to higher costs and a higher injury incidence density. The southwest quadrant indicates that the intervention is less effective but less expensive and the northeast quadrant indicates that the intervention is more effective but more expensive.

If the intervention was ‘dominant’, an ICER was not calculated. We applied the cost evaluation with a time horizon of one football season and from a societal perspective, considering all relevant costs and effects, regardless of who pays or who benefits from the effects.

Results

Initially, 846 clubs in Switzerland were invited to participate. A total of 55 clubs (with 78 teams) agreed to take part in the study and were randomised according to the age groups of the teams and the size of the club. In total, 62 teams with 1002 players completed the study (for study flow of participants, see online supplementary material 2). Anthropometric characteristics were similar in the INT and CON groups. During the study period, 99 injuries (INT=42 injuries, CON=57 injuries) occurred, of which 53 were medically treated (table 2). For more details on injury characteristics (number, percentage and injury incidence density by injury location, type and mechanism for the INT and CON groups) and intervention effects on injury risk, see online supplementary material 2. Two of these 53 injuries were sustained by girls (both in the INT group). Table 3 shows the healthcare resource use of injured players and respective medical costs in both groups.

Table 2.

Player characteristics, exposure, injury, cost data and cost differences between the ‘11+ Kids’ intervention and control groups

| Outcome | Intervention | Control | Total |

| No of players (N) | 614 | 388 | 1002 |

| No of girls (% of total) | 45 (7.3) | 29 (7.5) | 74 (7.4) |

| Teams (N) | 37 | 25 | 62 |

| Age (years) | 11.0 (1.2) | 10.6 (1.1) | 10.9 (1.2) |

| Body height (m) | 1.46 (0.09) | 1.44 (0.08) | 1.45 (0.08) |

| Body mass (kg) | 37.2 (7.7) | 36.1 (7.0) | 36.8 (7.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17.2 (2.6) | 17.2 (2.3) | 17.2 (2.5) |

| Exposure time (hours) | 43 777 | 32 596 | 76 373 |

| Total No of injuries (N) | 42 | 57 | 99 |

| Medically treated injuries (N) | 20 | 33 | 53 |

| Total No of injured players (N) | 20 | 32 | 52 |

| No of players with one injury (N) | 20 | 31 | 51 |

| No of players with two injuries (N) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| No of injuries by time loss (N) (% of total) | |||

| No time loss | 1 (5.0) | 3 (9.1) | 4 (7.5) |

| 1–3 days | 0 (0) | 3 (9.1) | 3 (5.7) |

| 4–7 days | 6 (30.0) | 1 (3.0) | 7 (13.2) |

| 8–28 days | 10 (50.0) | 14 (42.4) | 24 (45.3) |

| >28 days | 3 (15.0) | 12 (36.4) | 15 (28.3) |

| Sum of days lost to injury (days) | 355 | 910 | 1265 |

| Mean lay-off time (95% CI) (days) | 17.7 (11.9, 23.6) | 27.6 (17.9, 37.3) | 23.9 (17.5, 30.3) |

| Comparison between groups | Intervention | Control | |

| IID and HR (95% CI) | IID 0.96 (0.71, 1.30) | IID 1.75 (1.35, 2.27) | HR 0.50 (0.29, 0.86) |

| Costs per player* (95% CI) (CHF) | 16.28 (9.80, 23.94)† | 39.40 (22.96, 58.06) | CD −23.12 (−39.09,–7.14) |

| Costs per injured player (95% CI) (CHF) | 238.02 (154.61, 335.68)† | 268.20 (179.11, 371.49) | CD −30.19 (−166.13, 105.75) |

| Costs per 1000 hours of exposure (95% CI) (CHF) | 228.34 (137.45, 335.77)† | 469.00 (273.30, 691.11) | CD −240.66 (−406.89,–74.32) |

*Per player season.

†Taking into account CHF4.02 intervention costs per player in the study setting.

CD, cost difference between the ‘11+ Kids’ intervention and control groups in Swiss Francs; CHF, Swiss Francs; HR, Hazard R atio between the ‘11+ Kids’ intervention and control groups; IID, injury incidence density per 1000 hours of exposure.

Table 3.

Healthcare resource use of injured players and respective medical costs in the ‘11+ Kids’ intervention and control groups

| Healthcare resource use | Intervention | Control | ||

| n=20 injuries | n=33 injuries | |||

| Units | Cost* (CHF) | Units | Cost* (CHF) | |

| Physician visits (including consultation and clinical diagnostics) | 17 | 3201 | 32 | 7495 |

| Diagnostics | ||||

| X-ray | 7 | 299 | 17 | 761 |

| Ultrasound | 3 | 263 | 1 | 101 |

| MRI | 3 | 1124 | 7 | 2684 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Wound care | 1 | 59 | 3 | 205 |

| Casts and braces | 7 | 600 | 16 | 1638 |

| Physical therapy | 3 | 1663 | 3 | 2388 |

| Other | 1 | 320 | 1 | 16 |

| Sum | 42 | 7529 | 80 | 15 288 |

*Total costs for the number of units.

CHF, Swiss Francs (rounded to the nearest whole number).

Trial based cost effectiveness analysis

We took the actual costs of the ‘11+ Kids’ intervention in the study setting into account. These costs include expenditures for the manuals, organisation of education courses for the coaches as well as costs of coaches attending the ‘11+ Kids’ instruction course. Total intervention costs were CHF4.02 per player (ie, player season) in our study (table 1, and see additional information in online supplementary material 1).

Figure 1 depicts the cost effectiveness plane of the INT group in comparison with the CON group. The ICER for the INT group in comparison with the CON group was dominant (95% CI dominant, dominant), based on a difference in the mean cost per player (ie, player season) of CHF−23.12 and a difference in the mean efficacy of 7.9% (ie, 14.7% of players injured in the CON group versus 6.8% in the INT group). Of all bootstrapped ICERs, 94.6% were located in the southeast (dominant) quadrant (figure 1), indicating that there were considerably lower costs and fewer injuries compared with the CON group.

Incremental cost effectiveness ratio for a countrywide implementation scenario in Switzerland

For a countrywide implementation scenario (model based), the ICER was dominant (95% CI dominant, dominant), based on a difference in the mean cost per player of CHF−25.20 and assuming the same difference in efficacy of 7.9%. For this scenario, 95.5% of the bootstrapped ICERs of the INT group were located in the southeast quadrant, demonstrating dominance of the INT group above the CON group (figure 2).

Estimated injuries and costs avoided with implementing ‘11+ Kids’ in Switzerland

Table 1 displays the data on which we based our estimation of costs for implementing the programme in Switzerland (further information in online supplementary material 1). Based on the difference in the mean cost per player (CHF−25.20) between the INT group and the CON group and the number of players in Switzerland, CHF1.48 million in healthcare costs could be avoided with the ‘11+ Kids’ injury prevention strategy in just one season.

Discussion

Main study findings

The new injury prevention programme ‘11+ Kids’ has been shown to reduce football injuries in children in a multicentre cluster randomised controlled trial compared with a standard warmup.22 Based on data from Switzerland, we analysed direct medical costs of injuries. This exercise based injury prevention programme is efficacious in reducing the number of football injuries by 50%. In addition to the number of injuries, healthcare costs per player season were 59% lower (CHF−23.12, 95% CI −39.09 to –7.14) and costs per 1000 hours of football exposure were 51% lower (CHF−240.66, 95% CI −406.89 to –74.32) compared with the team’s usual warmup. Further, the cost effectiveness analysis showed a 94.6% likelihood (trial based data) and a 95.5% likelihood (model based implementation scenario) for the intervention programme being dominant (ie, more effective and less costly) over the usual warmup routine.

Comparison with previous studies

A previous study investigating the cost effectiveness of a neuromuscular training programme in youth football (13–18 years) found both a reduction in injuries (−38%) and costs (−43%). These findings highlight the importance of widely implementing exercise based injury prevention strategies in youth football.27 No study has previously investigated the economic impact of exercise based injury prevention in children’s football. Our findings (in players <13 years of age) show similar beneficial injury and cost reduction effects as the above mentioned study in older players. A randomised controlled trial in adult male amateur football players, however, did not show an overall reduction in injury, but did show a reduction in direct healthcare costs related to injury (−27%). The authors concluded that the cost savings might be related to the preventive effect of knee injuries in the INT group.28

In The Netherlands, annual cost savings of €35.9 million (CHF38.4 million, EUR-CHF 1.07, 2015; USD39.8 million, EUR-USD 1.11, 2015; GBP26.0 million, GBP-EUR 1.38, 2015) have been estimated, given a widespread application of a programme to reduce the recurrence of lateral ankle sprains, compared with usual care.29 A further study from this group concluded that bracing is the dominant secondary preventive intervention over both neuromuscular training and the combination of neuromuscular training and bracing.24 In contrast with other intervention programmes, the proposed ‘11+ Kids’ does not require special training equipment, like balance boards, which is a major advantage regarding cost effectiveness.27

Strengths and limitations

The proportion of girls was representative of the population of football playing children in Switzerland. However, the absolute number was too low to draw conclusions about girls specifically. In older players, similar preventive effects of the ‘11+’ have been described for young female and male football players.30 31 Hence comparable effects could be expected for girls and boys in children’s football.

Costs related to side line treatment of injuries (eg, first aid, tape) were not recorded. However, it could be assumed that the total costs of these treatments were low and did not substantially influence the results. If there was an influence, it could be speculated that it would be in favour of the INT group, as the risk for mild and moderate injuries was also reduced.22

We did not investigate indirect costs related to injury (eg, loss in productivity of parents when nursing the injured child). In a study on Dutch schoolchildren aged 10–12 years, indirect costs accounted for 40% of the total injury related costs.11 Therefore, it can be assumed that the reduction in injury costs observed in our study substantially underestimates the total financial savings.

In common with previous high quality studies, injury data were reported by coaches. Only if an injury was reported by the coach, parents and players were contacted to gather detailed information.30–32 To maximise the quality of reporting, all coaches of the INT and CON groups were thoroughly instructed on the injury definitions and were regularly contacted by our study assistants to ensure timely and complete data entry. To minimise potential recall bias, coaches received an automated reminder via email within a week if they did not enter data into the online system. After 2 weeks without data entry, our study assistants contacted the coaches personally (via telephone and/or email).

Data recording in the INT teams started after the ‘11+ Kids’ instruction session. Therefore, the exposure time was lower in the INT group than in the CON group. We performed a sensitivity analysis by cutting the respective time period (exposure time and injury events) in the CON group at the beginning of the season. The results were similar compared with the regular analysis. Consequently, the observed intervention effect was very likely not biased.

The statistical approach does not allow controlling for potential confounders. However, in the corresponding publication on the efficacy of ‘11+ Kids’, we controlled the analysis for team and intra-person clustering, age, age independent body height and match training ratio.22 It was, however, not possible to control the analyses for previous injury as the level of detail of these retrospectively collected data was too heterogeneous. The observed point estimate of the intervention effect got stronger (ie, in favour of the INT group) by controlling for the above mentioned confounders. Therefore, the reported cost reductions could be considered conservative.

Societal costs may be additionally reduced through less dropouts from sport, leading to higher physical activity levels in the long term. Children remain active and are more likely to become active adults with a lower risk of lifestyle related diseases.1 3 33 34 However, our data provide only a snapshot of the potential short and long term effects of implementing such a sports injury prevention programme.

Future perspective

A major argument for coaches to use exercise based injury prevention is the positive effect on athletes’ performance.21 35 36 It is important to convince coaches and players to regularly use the programme, as compliance with the programme is directly linked to the reduction in injury risk.22 35 37 38 It has been shown that injuries had a significant negative influence on team performance in male professional football.39 This underlines the importance of injury prevention to increase a team’s chances to win matches.

Injuries are among the most important reasons for dropping out from sport.40 Dropout from sport is directly associated with lower physical activity levels. The resulting reduction in physical activity negatively affects health and well being.2 41 Injury prevention not only supports the individual to stay injury free but it is also positively associated with physical activity in the long term.3 As such, it can be stated that the relevance of injury prevention at an early age is widely underestimated.

An efficacious preventive programme needs to be adopted and used in the real world setting to achieve health benefits in the population.42 When developing ‘11+ Kids’, we worked closely with researchers, clinicians, practitioners and members of the target community.43 Therefore, the programme has a good chance of fulfilling the requirements of being adopted by the wider community. Including the ‘11+ Kids’ in coaches’ education could enable a countrywide reach. Countrywide campaigns have started in New Zealand (see http://fit4football.co.nz/the-11plus/11plus-kids) and the Czech Republic. It is planned that other countries will follow soon.

Conclusion

The warmup and injury prevention programme for children’s football ‘11+ Kids’ substantially reduced injury related costs and was cost effective compared with a usual warmup routine, in terms of realistic implementation costs. These findings provide strong evidence for the implementation of this programme.

What are the new findings?

The ‘11+ Kids’ programme reduced the injury related healthcare costs by 51% in players aged 7–12 years.

The cost effectiveness analysis showed a 94.6% likelihood (trial based data) and a 95.5% likelihood (model based implementation scenario) for ‘11+ Kids’ being dominant (ie, more effective and less costly) over usual warmup.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the near future?

The clear reduction in injury related costs provides strong evidence for a widespread implementation of the ‘11+ Kids’.

A countrywide application of ‘11+ Kids’ in Switzerland could prevent approximately 2500 medically treated injuries and save CHF1.48 million in direct healthcare costs per year.

Countrywide implementation campaigns have started already in New Zealand and the Czech Republic

Acknowledgments

We thank the study assistants Nadine Rolser, Silvan Stürchler, Florian Giesin, Fridolin Petersen, Florian Lohberger and Marco Bassanello for their support during data collection. We thank all participating football clubs, coaches, players and parents.

Footnotes

Contributors: RR, EV and OF designed the study protocol. AJ and JD contributed to the design of the study. RR organised the study (ie, recruitment, data collection, quality control). EL contributed to study organisation. RR conducted the overall data management and organised the data preparation. EL contributed to the data preparation. RR analysed the data. RR and NR wrote the manuscript. RR, OF, EV and NR revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to reviewing and revising the manuscript, and agreed on the final draft.

Funding: This study was supported by Fédération Internationale de Football Association and the University of Basel (grant: Top-Up Stipend).

Competing interests: AJ was a member of the FIFA Medical Assessment and Research Centre (F-MARC). JD was chairman of F-MARC and consulting member of the FIFA Medical Committee until Autumn 2016.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz, EKNZ (approval No 2014-232).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Azevedo MR, Menezes AM, Assunção MC, et al. Tracking of physical activity during adolescence: the 1993 Pelotas Birth Cohort, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica 2014;48:925–30. 10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048005313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Landry BW, Driscoll SW. Physical activity in children and adolescents. Pm R 2012;4:826–32. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.09.585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Janssen I, Leblanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010;7:40 10.1186/1479-5868-7-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Faude O, Kerper O, Multhaupt M, et al. Football to tackle overweight in children. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010;20(Suppl 1):103–10. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01087.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Michaud PA, Renaud A, Narring F. Sports activities related to injuries? A survey among 9-19 year olds in Switzerland. Inj Prev 2001;7:41–5. 10.1136/ip.7.1.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bijur PE, Trumble A, Harel Y, et al. Sports and recreation injuries in US children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149:1009–16. 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170220075010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. King MA, Pickett W, King AJ. Injury in Canadian youth: a secondary analysis of the 1993-94 Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Survey. Can J Public Health 1998;89:397–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hedström EM, Bergström U, Michno P. Injuries in children and adolescents–analysis of 41,330 injury related visits to an emergency department in northern Sweden. Injury 2012;43:1403–8. 10.1016/j.injury.2011.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Belechri M, Petridou E, Kedikoglou S, et al. Sports injuries among children in six European union countries. Eur J Epidemiol 2001;17:1005–12. 10.1023/A:1020078522493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maffulli N, Longo UG, Gougoulias N, et al. Long-term health outcomes of youth sports injuries. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:21–5. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.069526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Collard DC, Verhagen EA, van Mechelen W, et al. Economic burden of physical activity-related injuries in Dutch children aged 10-12. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:1058–63. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.082545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Caine D, Caine C, Maffulli N. Incidence and distribution of pediatric sport-related injuries. Clin J Sport Med 2006;16:500–13. 10.1097/01.jsm.0000251181.36582.a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Öztürk S, Kılıç D. What is the economic burden of sports injuries? Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi 2013;24:108–11. 10.5606/ehc.2013.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mayo M, Seijas R, Alvarez P. [Structured neuromuscular warm-up for injury prevention in young elite football players]. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol 2014;58:336–42. 10.1016/j.recote.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barengo NC, Meneses-Echávez JF, Ramírez-Vélez R, et al. The impact of the FIFA 11+ training program on injury prevention in football players: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:11986–2000. 10.3390/ijerph111111986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Herman K, Barton C, Malliaras P, et al. The effectiveness of neuromuscular warm-up strategies, that require no additional equipment, for preventing lower limb injuries during sports participation: a systematic review. BMC Med 2012;10:75 10.1186/1741-7015-10-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Al Attar WS, Soomro N, Pappas E, et al. How effective are f-marc injury prevention programs for soccer players? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2016;46:205–17. 10.1007/s40279-015-0404-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rössler R, Donath L, Verhagen E, et al. Exercise-based injury prevention in child and adolescent sport: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2014;44:1733–48. 10.1007/s40279-014-0234-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rössler R, Junge A, Chomiak J, et al. Soccer injuries in players aged 7 to 12 years: a descriptive epidemiological study over 2 seasons. Am J Sports Med 2016;44:309–17. 10.1177/0363546515614816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rössler R, Junge A, Chomiak J, et al. Risk factors for football injuries in young players aged 7 to 12 years. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2018;28:1176–82. 10.1111/sms.12981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rössler R, Donath L, Bizzini M, et al. A new injury prevention programme for children’s football–FIFA 11+ Kids–can improve motor performance: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. J Sports Sci 2016;34:549–56. 10.1080/02640414.2015.1099715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rössler R, Junge A, Bizzini M, et al. A multinational cluster randomised controlled trial to assess the efficacy of '11+ kids': a warm-up programme to prevent injuries in children’s football. Sports Med 2018;48:1493–504. 10.1007/s40279-017-0834-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. BMJ 2013;346:f1049 10.1136/bmj.f1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Janssen KW, Hendriks MR, van Mechelen W, et al. The cost-effectiveness of measures to prevent recurrent ankle sprains: results of a 3-arm randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:1534–41. 10.1177/0363546514529642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zentralstelle für Medizinaltarife UVG. TARmeD Tarifbrowser. TARMED Suisse 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fenwick E, Marshall DA, Levy AR, et al. Using and interpreting cost-effectiveness acceptability curves: an example using data from a trial of management strategies for atrial fibrillation. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:52 10.1186/1472-6963-6-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marshall DA, Lopatina E, Lacny S, et al. Economic impact study: neuromuscular training reduces the burden of injuries and costs compared to standard warm-up in youth soccer. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1388–93. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krist MR, van Beijsterveldt AM, Backx FJ, et al. Preventive exercises reduced injury-related costs among adult male amateur soccer players: a cluster-randomised trial. J Physiother 2013;59:15–23. 10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70142-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hupperets MD, Verhagen EA, Heymans MW, et al. Potential savings of a program to prevent ankle sprain recurrence: economic evaluation of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:2194–200. 10.1177/0363546510373470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Silvers-Granelli H, Mandelbaum B, Adeniji O, et al. Efficacy of the FIFA 11+ Injury prevention program in the collegiate male soccer player. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:2628–37. 10.1177/0363546515602009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Soligard T, Myklebust G, Steffen K, et al. Comprehensive warm-up programme to prevent injuries in young female footballers: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008;337:a2469 10.1136/bmj.a2469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grooms DR, Palmer T, Onate JA, et al. Soccer-specific warm-up and lower extremity injury rates in collegiate male soccer players. J Athl Train 2013;48:782–9. 10.4085/1062-6050-48.4.08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Janz KF, Dawson JD, Mahoney LT. Tracking physical fitness and physical activity from childhood to adolescence: the muscatine study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:1250–7. 10.1097/00005768-200007000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flynn MA, McNeil DA, Maloff B, et al. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with ’best practice' recommendations. Obes Rev 2006;7(Suppl 1):7–66. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00242.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Faude O, Rössler R, Petushek EJ, et al. Neuromuscular adaptations to multimodal injury prevention programs in youth sports: a systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Physiol 2017;8:791 10.3389/fphys.2017.00791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zarei M, Abbasi H, Daneshjoo A, et al. Long-term effects of the 11+ warm-up injury prevention programme on physical performance in adolescent male football players: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. J Sports Sci 2018. 8:1–8. 10.1080/02640414.2018.1462001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hammes D, Aus der Fünten K, Kaiser S, et al. Injury prevention in male veteran football players - a randomised controlled trial using “FIFA 11+”. J Sports Sci 2015;33:873–81. 10.1080/02640414.2014.975736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Steffen K, Emery CA, Romiti M, et al. High adherence to a neuromuscular injury prevention programme (FIFA 11+) improves functional balance and reduces injury risk in Canadian youth female football players: a cluster randomised trial. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:794–802. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hägglund M, Waldén M, Magnusson H, et al. Injuries affect team performance negatively in professional football: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:738–42. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grimmer KA, Jones D, Williams J. Prevalence of adolescent injury from recreational exercise: an Australian perspective. J Adolesc Health 2000;27:266–72. 10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00120-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. World Health O. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks: World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Verhagen E, Finch CF. Setting our minds to implementation. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:1015–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hanson D, Allegrante JP, Sleet DA, et al. Research alone is not sufficient to prevent sports injury. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:682–4. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bjsports-2018-099395supp001.docx (62KB, docx)