Abstract

Introduction

Different cooling strategies exist for emergency treatments immediately after sports trauma or after surgery. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of three cooling regimen during the immediate postoperative phase as well as in the rehabilitation phase.

Methods

36 patients undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction received either no cooling (control-group, Con, N=12), were cooled with a menthol-containing cooling bandage (Mtl, N=12) or cooled with an ice containing cold pack (CP, N=12). During a 12-week physiotherapy treatment the cross section of the vastus medialis muscle was examined (day—1; 30; 60; 90) and painkiller consumption was documented.

Results

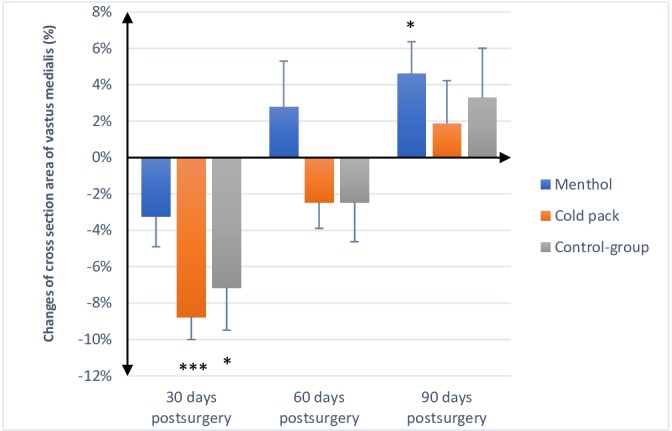

A significant reduction in the cross section area 30 days after surgery was observed in CP and Con (Mtl: −3.2±1.7%, p=0.14, CP: −8.8±4.3%, p<0.01, Con: −7.2±8.1%, p<0.05). After 90 days of therapy, a significant increase in muscle cross section area was observed in Mtl (Mtl: 4.6%±6.1%, p<0.05, CP: 1.9%± 8.1%, p=0.29, Con: 3.3%±9.4%, p=0.31). The absolute painkiller consumption was lower for Mtl (25.5±3.7 tablets) than for CP (39.5±6.9 tablets) or Con (34.8±4.2 tablets).

Conclusion

We observed a beneficial effect of cooling by a menthol-containing bandage during the rehabilitation phase. Reduction of muscle cross section within 30 days after surgery was prevented which highly contributed to rehabilitation success after 90 days of therapy. Painkiller consumption was reduced with Mtl.

Keywords: rehabilitation, recovery, sports medicine, physiotherapy, orthopaedics

Summary box.

Cooling with menthol was found to be an effective treatment in the postoperative phase as well as during physical therapy.

Cooling with menthol was perceived by the patients as safe and easy to apply.

Besides the positive subjective feedback about comfort noted in patients cooling with menthol, tendencies in clinically relevant aspects such as less intake of analgesics and less pronounced muscle atrophy were observed and will need further investigation.

Introduction

Cooling treatments are popular, non-pharmacological interventions and available immediately after sports trauma or surgery in order to treat acute responses such as swelling or pain.1 Finally, this intervention might contribute to an improved recovery due to increased efficacy rehabilitation interventions.2 3

Local cooling of skin induces numerous physiological responses by the reduction of skin surface and subjacent tissue temperature.4 5 This leads to a significant decline of nerve conduction velocity6 as well as to vasoconstriction7–9 decreasing tissue perfusion.10 Furthermore, the contraction of blood vessels prevents the development of oedema11 and reduces local swelling.12 Furthermore, local cooling affects pain perception in the postoperative period after reconstructive surgery.2 13–15 Shelbourne16 observed an increase of the pain threshold and Levy and Marmar17 an increase of the pain tolerance. Cryotherapy reduces the blood-flow and the metabolic rate in injured muscle.18 However, a few studies reported negative side effects or complications of cooling Interventions. There are rare cases where panniculitis, an inflammation of the subcutaneous adipose tissue, can be caused by cold therapy.19 Specifically, very strong cooling poses a risk for developing panniculitis, particularly for infants and young children.20 Alternatively it may lead to serious side effects, such as nerve injuries or frostbites.

Nowadays, a wide variety of cooling methods applied on body parts for full body application are used. These methods differ in their modality by application duration, frequency or cooling intensity, for example. As a consequence, the extent of the cold induced tissue temperature reduction varies as well.21 Cold water leads to a significant reduction of conduction and arterial blood flow and a reduced level of muscle soreness at 1, 24 and 48 hours after exercise.22–24 Thereby, cold water immersion is an intervention which is often used as a cooling treatment after physical exercise for supporting recovery or to treat exercise or heat induced hyperthermia.24–26 The cooling with ice is characterised by a rapid drop of tissue temperature. During a 20-min ice pack application, the muscle temperature and the subcutaneous temperature decrease by 7°C and 17°C, respectively.27 As a result, ice cooling can be applied only for a few minutes on the affected structure. Cold pack consists of frozen gels. Due to the similar and enormous cooling effect comparable with ice, direct skin contact should be avoided and a towel or a protection cover should be used to avoid skin injuries. Menthol containing cooling agents are associated with fresh and cooling sensation and just have become available in recent time.28 Menthol activates the transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8) ion channel,28 which is normally activated by cold temperatures. The cool feeling during menthol application origins from mimicking local cooling rather than a strong cooling of the respective body part. Nevertheless, some kind of evaporative cooling is included as ethanol solutions of menthol are mostly applied.29 Furthermore, the ingestion of menthol resulted in improvements of endurance performance, which was found to be to most effective application with regard to exercise performance for athletes competing in the heat.30 31 Up to now there has been little research about the effectiveness of menthol-containing liquids compared with conventional methods such as cooling with an ice or cold pack.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the effects of two cooling strategies, that is, continuous application of menthol-containing liquid against intermittent application of cold pack in a randomised, placebo-controlled study design. The major hypothesis was that the continuous application of menthol cooling leads to no differences in muscle loss, easier handling and improved comfort during its application. Besides, it was hypothesised that, due to the characteristics and additional menthol-induced activation of TRPM8, results have a sustained effect on pain reduction and a positive effect on the healing process after surgery. The objective of this study was to create a database to evaluate the efficiency of cooling in the immediate postoperative phase as well as in the rehabilitation phase and to be able to make statements about the effectiveness of two different cooling forms.

Methods

This pilot study was conducted as a randomised prospective clinical trial, carried out at the Berit-Klinik Speicher, the Hirslanden-Klinik am Rosenberg in Heiden and the Orthopädie St. Gallen to investigate the effect of cooling applications on the recovery during rehabilitation phase after operative reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Objective measures such as changes in muscle cross section or painkillers, as well as subjective measures such as comfort and pain reporting were included. Finally, surface skin temperature was measured during cooling applications (detailed description see Experimental investigations section).

Study participants/patients

The sample consisted of a total of 40 orthopaedic patients (four of them were excluded from the study because they were not able to strictly follow the study protocol) at the age of 30.9±11.1 years, with a body height of 173.7±9.7 cm and a body weight of 75.7±12.9 kg. To increase inter-subject comparability between patients and for standardisation, the study was limited to cruciate ligament patients. All patients suffered from an isolated rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament. The operative reconstruction was always done by the same surgeon. All patients were treated according to the same protocol of spinal anaesthesia, ibuprofen (2-(p-isobutyl-phenyl-)propionic acid) was always administered as the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). To avoid complications and ensure similar responses during rehabilitation process, the surgery took place at latest 8 weeks after the injury. The inclusion criteria of the study were patients aged between 18 and 60 years who had an operative reconstruction using the semitendinosus tendon. Hypersensitivity, cold tolerance, peripheral neuropathy, diabetes mellitus, allergy to and/or ethanol menthol and eczema or rash were accepted as exclusion criteria. The individuals were recruited and invited to take part in the pilot study before surgery. After acceptance and the signed informed consent form, the patients were randomised into two different cooling groups (cold pack, menthol) or to the control-group, without any cooling.

Study design

This study does not provide any personal medical information about identifiable living individuals. Patients were not involved in the study preparation (research question, study design) or evaluation of cooling. The patients included in the pilot study were assessed by the surgeon and authorised study personal. The standardised protocol of postoperative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament was applied from the first day after surgery in every randomised group. All patients, regardless of group affiliation, received the identical physiotherapeutic treatment (60 min per session) three times a week during the entire study period of 12 weeks. The physiotherapeutic treatment was performed exclusively by specially authorised physiotherapists, all of whom treated to the same physiotherapy protocol. The cooling interventions (cold pack, menthol) were applied three times a day (09:00, 14:00, 19:00) during stationary hospitalisation for 3 days. From day 4 to 30, cooling applications were applied twice a day (10:00, 17:00). The application times of the cooling interventions were implemented according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cold pack-group received the application of the cooled gel-pad (Cold pack, Nexcare) in a protection cover provided by the supplier and were cooled for 20 min. Patients of the menthol-group received a bandage wetted by a menthol-containing liquid (cool down ice fluid) and were cooled for 120 min. The control-group got the same physiotherapy treatment but received no cooling application.

Experimental investigations

The muscle cross section of the vastus medialis was determined by an Ultrasound device (Logiq e, GE Medical Systems AG, with a multifrequency probe 13 MHz, Glattbrugg, Switzerland). The measurement was conducted three times in the centre of m. vastus medialis (8 cm proximal from patella border and 6 cm medial) during a knee flexion of 90°. The mean value of the three measurements was used for further analysis. Skin temperature was continuously recorded minute by minute during stationary hospitalisation (iButton type DS1922L, Maxim Integrated, San Jose, California, USA). The sensors were fixed on the skin with tape (Curapor transparent, 7 cm×5 cm, Lohmann & Rauscher International GmbH & Co. KG, Rengsdorf, Germany) and placed just above the upper inner quadrant of the patella of the injured and uninjured knee. This allowed analysis of the cooling effect on skin temperature. The minimum skin temperature reached during cooling as well as total cooling time was obtained for every single cooling and every study participant. The minimum cooling temperature was the lowest measured temperature (°C) of a cooling period. The cooling duration included the period (min) from starting cooling to the time point where skin temperature reached again precooling values for further data analysis, the median of the parameters were calculated and compared. The subjective perception of pain, perception of comfort and the use of painkillers were recorded in a questionnaire from day 1 to 30 using the NRS scale and a thermal condition scale.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software (IBM SPSS, V.23). Values for parameters are given as mean±SD or median. All parameters were checked for normal distribution and variance homogeneity. As these assumptions were not fulfilled by all parameters (ie, two data sets for cross section area measurement, minimum cooling temperature, cooling duration, number of physiotherapy-treatment units) non-parametric statistical tests were applied. This is Wilcoxon signed rank test to analyse the relative change in cross section area at different time points, Mann-Whitney U test for the comparison of cooling parameters differences for cooling parameters and independent samples Kruskal-Wallis test for the analysis of group related differences in painkiller consumption and physiotherapy-treatment units. Independent samples Kruskal-Wallis test was applied as well for the assessment of statistical differences in the subjective pain-score and comfort-score between treatment groups because no normal distribution could be assumed for discrete data set. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

A reduction in the cross section area 30 days after surgery was observed for all groups (−3.2±5.8%, p=0.14; −8.8±4.3%, p<0.01; −7.2±8.1%, p<0.05, for menthol-containing cooling bandage (Mtl), cold pack (CP) and control-group (Con), respectively). The group receiving Mtl cooling was the only group with no significant reduction in the cross section after 30 days (figure 1). After 90 days of therapy, an increase in muscle cross section area was observed for all groups (4.6%±6.1%, p<0.05; 1.9%±8.1%, p=0.29; 3.3%±9.4%, p=0.31, for Mtl, CP and Con, respectively), while a statistical significant change was observed in Mtl only. Significant differences were found for minimum cooling temperature (Mtl: 29.7°C±1.3°C, CP: 18.1°C±4.5°C; p<0.001) and cooling period (Mtl: 173.1±17.9 min, CP: 94.1±39.4 min; p<0.001). Cooling application was perceived as more comfortable in the Mtl group. Generally, no significant differences were observed in the perception of pain (pain level in the morning: p=0.151; in the evening: p=0.282; total: p=0.213). However, on specific occasions, the menthol-group revealed the lowest perception of pain (ie, evening 7 and 28), whereas no differences were detected between cold pack-group and control-group. On the other hand, on another occasion (ie, in the morning on day 21) the cold pack-group appeared to have the highest pain level. Feedback about comfort perception revealed differences for the first 4 weeks. Highest comfort reporting was detected in Mtl while the cold pack-group showed the lowest comfort. After cooling applications, no further differences between the groups were detected. Overall, no differences could be observed between groups during total study duration (p=0.058). No significant differences were found between groups for painkiller consumption (p=0.209). However, Mtl showed lower absolute painkiller consumption (25.5±3.7 tablets) than CP (39.5±6.9 tablets) or Con (34.8±4.2 tablets). Regarding treatment units, there were no significant differences (Mtl: 30.3±1.2, Ice: 31.2±1.3, Con 31.3±2.2; p=0.664) (table 1).

Figure 1.

Changes in muscle cross section area (CSA) of vastus medialis-muscle, showing mean (SD) 30, 60 and 90 days after operative ACL-reconstruction. *Significant reduction of CSA in control-group (p=0.011) after 30 days and significant increase in menthol-group (p=0.024) after 90 days. ***Highly significant reduction in CSA in cold pack-group after 30 days (p=0.000).

Table 1.

Anthropometric data, such as therapy-visits and painkiller (Irfen)-consumption. Values are mean±SD

| Group | ||||

| Menthol | Cold pack | Control | Overall | |

| Height (cm) | 174.5±10.1 | 170.7±10.4 | 175.8±8.7 | 173.7±9.7 |

| Weight (m) | 76.3±9.8 | 70.6±10.5 | 80.2±16.6 | 75.7±12.9 |

| Age (years) | 32.2±14 | 29.8±10.9 | 30.8±8.7 | 30.9±11.1 |

| Physiotherapy-visits | 30.3±4.3 | 31.2±4.6 | 31.3±2.2 | 30.9±3.8 |

| Irfen-consumption (Tabl. à 600 mg) | 25.5±12.9 | 39.5±23.9 | 34.8±14.6 | 33.7±18.4 |

Discussion

The most important finding of this study is that cooling by a menthol-containing bandage has a beneficial effect during the rehabilitation phase.

Effect on muscle cross section

The vastus medialis is known to be essential for the biomechanical stabilisation of the knee joint. A reduction in muscle cross section of the vastus medialis was observed in all groups 30 days after surgery compared with baseline measurements, which confirms the results of other studies and the initial muscle atrophy after an accident or surgery.32 33 Continuous physiotherapy resulted in an increase of muscle cross section area in all groups 60 days and 90 days after surgery.34 All patients received an identical physiotherapy treatment without any additional exercise at home and attended the same number of physiotherapy sessions. Nevertheless, patients allocated to Mtl did not show a significant reduction 30 days after surgery. CP and Con revealed a similar reduction of approximately 8%. After 60 days, menthol-group already showed an increase in muscle cross section area, while CP and control-group showed a slight reduction. Ninety days after surgery, the physiotherapy treatment was completed and all groups showed an increase in muscle cross section over baseline level, whereby Mtl outperformed the other groups. In 2014 Sattler et al35 observed at a similar training protocol (3×1 hours/week) after 12 weeks a significant increase in quadriceps volume as well, with the effect appearing largest for the vastus medialis.

The positive findings regarding muscle cross section in menthol-group probably depends on an interaction of our punctually positive findings regarding pain level and comfort level and the analgesic effect of menthol.31 36

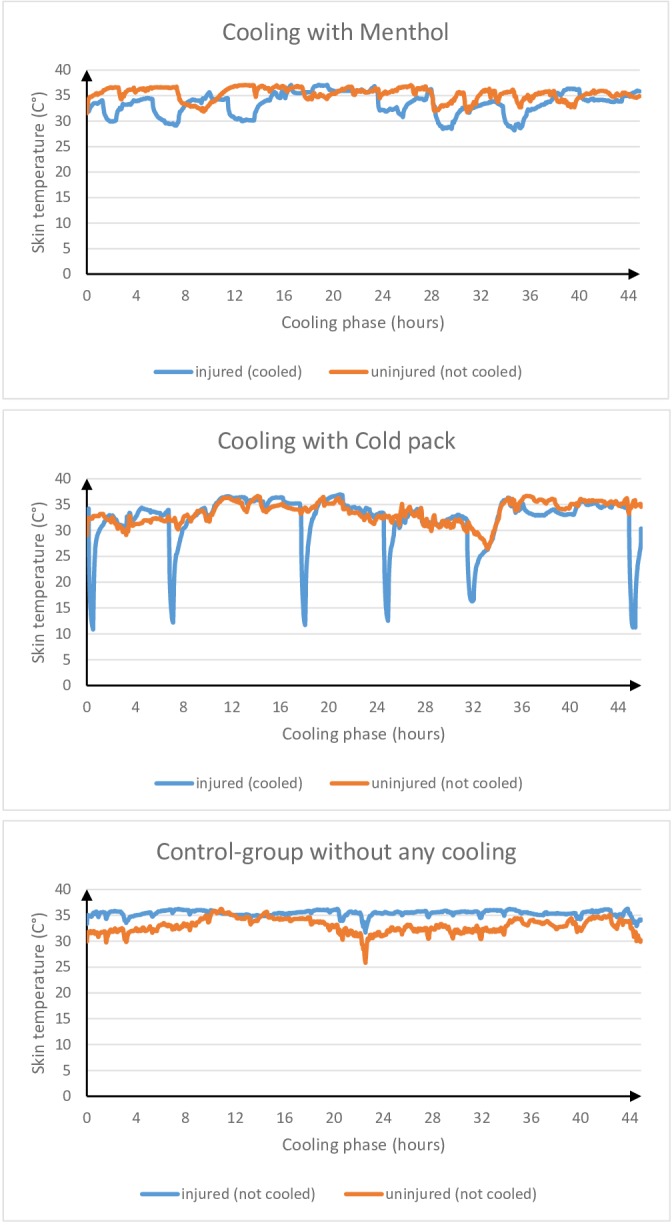

Effect on cooling parameters

Skin temperatures showed significant differences between cooling modalities (figure 2). Cooling with a cold pack is characterised by a short cooling intervention resulting in rapid temperature drops. Additionally, as a result, the cooling period of ice or a cold pack is very limited. Many patients described a comfortable feeling only up to 15 min after the cooling with ice started. During the first days after surgery the intensive cooling modality of a cold pack causes the high tissue inflammation to be perceived only just comfortable. In the continuous course, however, we observed the 20 min cooling period with cold pack a more uncomfortable feeling, especially towards the end. The longer the time left after surgery the less tissue inflammation and swelling is normally present. This is then associated again with a continuous drop of skin temperature of the operated area. Therefore, the intensive cooling characteristics of cold pack are often felt some days after surgery to be rather uncomfortable. Based on the intensive cooling characteristics of cold pack, there could also be a certain risk of tissue damage.

Figure 2.

Exemplary skin temperature course of cooling with menthol, cold pack and of control-group without cooling during cooling phase of initial 44 hours.

On the other hand, in the menthol-group, we observed only a moderate skin temperature decrease, what allows a significant longer cooling period and in principle even application forms well over 2 hours without any problems. The menthol wetted bandage can be applied by the patient himself without any clinic personal shortly after surgery in a few minutes. Other cooling methods, such as the cold and ice pack need a freezer for some hours and often additional clinic personal.

Effect on subjective pain level and comfort level

Postoperative pain management is an essential component for effective rehabilitation, recovery and patient satisfaction.37 A high pain level is inversely associated with function and with quality of life.38 39

Overall, we found no significant differences regarding pain level. However, we observed punctually positive findings in the menthol-group during the cooling period, in the first 4 weeks.

Those punctually reduced pain level findings could be related to our positive findings regarding muscle cross section of vastus medialis-muscle.

Investigations of Sattler et al35 and Wang et al40 showed a significant difference in muscle cross section of the vastus medialis in painful compared with contralateral painless limbs. Also, Cheon et al investigated the relationship between decreased lower extremity muscle mass and knee pain intensity in both the general population and patients with knee osteoarthritis.41 They found that a decreased lower extremity muscle mass was an independent risk factor for knee pain and it was associated with increased pain intensity, regardless of radiographic knee osteoarthritis. However, probably not only the reduced pain has a positive influence on the muscle cross section, but also the associated increased physical activity. An increased physical activity induces a hypertrophy of lower limb muscle, especially of vastus medialis, which positively affects reduction in the pain level and pain perception of the patients.35 41 Also stress and depression, which are often associated with chronic pain, can be positively affected by physical exercise,42 43 which further promotes the healing process.

Regarding to the subjective comfort-score, we observed significant differences in the first 4 weeks and thus exactly in the cooling period. After the cooling period no further differences were found. In the first 4 weeks, patients who were cooled with the menthol bandage expressed significant higher comfort-scores than patients who used the cold pack-cooling modality or belonged to the control-group. Surprisingly, a higher comfort-score was found for the control-group than for the cold pack-group.

A decreased pain level can reduce unconsciously the individual restraint of the operated leg, at the same time, increase the level of the whole-body activity and motion. Thus, an increased level of activity can then improve physical condition and contribute to increased muscle cross section.

Similar to our findings, in 2012 Johar et al44 observed that a menthol-based analgesic decreased perceived discomfort to a greater extent compared with ice. Possibly, rapid temperature drops and the very low skin temperatures during cooling with ice led to this result. Another reason for a higher comfort level in the menthol-group could be due to the easy handling of the menthol cooling. During the cooling with menthol bandage, the patients were hardly restricted and could applicate the bandage easily, even under the pants. During cooling with a cold pack, however, everyday movements are more difficult to perform and rather a complete immobilisation of the cooled area is needed. Of course, the self-specified pain-score and comfort-score is subjective and not objective. However, the importance of such subjective feelings for the medical staff or surgeon is often underestimated. The healing process is not only influenced by clinical, externally visible factors. Frequently subjective positive feelings represent important feedback and provide the basis for the healing process. Possibly due to the positive findings regarding pain-score and comfort-score in the menthol-group, there could be a thought to reduce therapy units and, thus, reducing costs for the health services.

To summarise, the differences in cross section area might arise from a combination of the different parameters, such as the positive effects for healing process of menthol application, a punctual lower pain level, the lower absolute painkiller consumption and a resulting improved possibility for activity in the daily life of menthol-group. Furthermore, an improved and increased activity-level of menthol-group may have a positive influence by the increased comfort level and punctual decreased pain level during the cooling period of the first 30 days (a, b, c). Differences in the muscle cross section area are due to the importance of active musculoskeletal system, very relevant for the therapeutic outcome and had a strong influence of the muscle strength. Furthermore, an increased cross section area of vastus medialis was reported to be related to a reduced cartilage loss and a decreased risk for joint replacement. Furthermore, the slight moderate temperature drop, the associated significant longer cooling period and the mentioned above benefits of menthol, could be essential reasons for our positive findings.

Currently there are many different opinions in medicine about the effects and benefits of cooling for the healing process. In addition to evidence of positive effects, possible disorders of the wound and damage of lymphatic vessels are being discussed. In our present study we could show that a more prolonged cooling method based on a menthol containing liquid resulted in a moderate drop in temperature and was applied for longer duration. In addition, positive subjective sensations and better output for clinically relevant parameters, such as a reduced muscle loss or absolute lower significant pain medication consumption, were observed. On the other hand, the study also showed that a too intensive cooling method with a rapid temperature drop and very low skin temperatures, such as the use of an ice or cold pack, had little or no benefit. Our subjects in the control-group, without any cooling, often showed better results compared with the use of intensive cooling.

Data sharing

The authors agree that data collected within this study may be released for scientific use. The following unpublished data from the study are available:

Data on torques of concentric flexion and extension of the thigh muscles. These were collected with an isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex System 3 Pro, Biodex Medical Systems, New York, USA), measured before surgery and after 3 months of physical therapy.

Data on the swelling of the operated and unoperated knee joint. This was determined with a commercially available tape measure and measured 10 cm above the patella.

To get access to this data, please contact the Corresponding Author (Dr med. Pierre Hofer, pierre.hofer@ortho-sg.ch).

Practical recommendations for use of menthol-cooling

After application clean the skin with water (→ reduced risk for skin irritation).

Main measurable effect of cooling with menthol bandage 120 min, but also longer application possible.

Basically, use of two bandages for application to obese patients possible.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the enormous effort of the nursing staff of the Berit Clinic in Speicher and the Hirslanden Clinic in Heiden. We thank Dr Ing. André Dietschi and the Kantonsspital St. Gallen (KSSG) for the provision of the ultrasound device. All cooling products were provided without any payment by the Cool Down AG. Other benefits were waved completely. We also wanted to thank the physiotherapy teams of the Berit Clinic, the Hirslanden Clinic in Heiden and the Orthopädie St. Gallen AG, which supervised the patients over the entire study period with the highest dedication.

Footnotes

Contributors: KL, PH and SA designed the study. PH and DE performed the experiments and SA analysed the data. PH, SA and DE wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: All study participants were older than 18 years and were informed prior to signing the consent form about any inpatient steps, potential risks and investigations.

Ethics approval: The procedures and interventions used in the present study were set up in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and were evaluated and approved by the Ethics Commission St. Gallen, Switzerland (EKSG 15/160; ISRCTN: 10207058; SwissEthics ProjectID: PB_2016–00286).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Adie S, Naylor JM, Harris IA. Cryotherapy after total knee arthroplasty a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty 2010;25:709–15. 10.1016/j.arth.2009.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swenson C, Swärd L, Karlsson J. Cryotherapy in sports medicine. Scandinavian journal of medicine science in sports 1996;6:193–200. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1996.tb00090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Melick N, van Cingel REH, Brooijmans F, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice update: practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016;50:1506–15. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glenn RE, Spindler KP, Warren TA, Warren TA, et al. Cryotherapy decreases intraarticular temperature after ACL reconstruction. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 2004;421:268–72. 10.1097/01.blo.0000126302.41711.eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostrowski J, Purchio A, Bartoletti M, et al. Examination of intramuscular and skin temperature decreases produced by the PowerPlay intermittent compression cryotherapy. Journal of sport rehabilitation 2017:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Algafly AA, George KP, Herrington L. The effect of cryotherapy on nerve conduction velocity, pain threshold and pain tolerance * commentary. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2007;41:365–9. 10.1136/bjsm.2006.031237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoshnevis S, Craik NK, Diller KR. Cold-induced vasoconstriction may persist long after cooling ends: an evaluation of multiple cryotherapy units. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 2015;23:2475–83. 10.1007/s00167-014-2911-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoshnevis S, Craik NK, Matthew Brothers R, et al. Cryotherapy-Induced persistent vasoconstriction after cutaneous cooling: hysteresis between skin temperature and blood perfusion. J Biomech Eng 2016;138 10.1115/1.4032126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson JM. Mechanisms of vasoconstriction with direct skin cooling in humans. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2007;292:H1690–H1691. 10.1152/ajpheart.00048.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curl WW, Smith BP, Marr A, et al. The effect of contusion and cryotherapy on skeletal muscle microcirculation. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1997;37:279–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Airaksinen OV, Kyrklund N, Latvala K, et al. Efficacy of cold gel for soft tissue injuries. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2003;31:680–4. 10.1177/03635465030310050801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klootwyk TE, Shelbourne KD, Decarlo MS. Perioperative rehabilitation considerations. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine 1993;1:22–5. 10.1016/S1060-1872(10)80025-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kullenberg B, Ylipää S, Söderlund K, et al. Postoperative cryotherapy after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective study of 86 patients. J Arthroplasty 2006;21:1175–9. 10.1016/j.arth.2006.02.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martimbianco ALC, Gomes da Silva BN, de Carvalho APV, et al. Effectiveness and safety of cryotherapy after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A systematic review of the literature. Physical Therapy in Sport 2014;15:261–8. 10.1016/j.ptsp.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hubbard TJ, Denegar CR. Does cryotherapy improve outcomes with soft tissue injury? J Athl Train 2004;39:278–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shelbourne KD. Postoperative cryotherapy for the knee in ACL reconstructive surgery. Orthopaedics 1994;2:165–70. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy AS, Marmar E. The role of cold compression dressings in the postoperative treatment of total knee arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 1993;&NA:174???178–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorsson O. [Cold therapy of athletic injuries. Current literature review]. Lakartidningen 2001;98:1512–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipke MM, Cutlan JE, Smith AC. Cold panniculitis: delayed onset in an adult. Cutis 2015;95:21–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.West SE, McCalmont TH, North JP. Ice-pack dermatosis: a cold-induced dermatitis with similarities to cold panniculitis and perniosis that histopathologically resembles lupus. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:1314–8. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auley D, Mac Auley DC. Ice therapy: how good is the evidence? International Journal of Sports Medicine 2001;22:379–84. 10.1055/s-2001-15656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gregson W, Black MA, Jones H, et al. Influence of cold water immersion on limb and cutaneous blood flow at rest. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:1316–23. 10.1177/0363546510395497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrera E, Sandoval MC, Camargo DM, et al. Motor and sensory nerve conduction are affected differently by ICE Pack, ice massage, and cold water immersion. Physical Therapy 2010;90:581–91. 10.2522/ptj.20090131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey DM, Erith SJ, Griffin PJ, et al. Influence of cold-water immersion on indices of muscle damage following prolonged intermittent shuttle running. J Sports Sci 2007;25:1163–70. 10.1080/02640410600982659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gagnon D, Lemire BB, Casa DJ, et al. Cold-water immersion and the treatment of hyperthermia: using 38.6°C as a safe rectal temperature cooling limit. Journal of Athletic Training 2010;45:439–44. 10.4085/1062-6050-45.5.439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Proulx CI, Ducharme MB, Kenny GP. Effect of water temperature on cooling efficiency during hyperthermia in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology 2003;94:1317–23. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00541.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myrer JW, Measom G, Durrant E, et al. Cold- and hot-pack contrast therapy: subcutaneous and intramuscular temperature change. J Athl Train 1997;32:238–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohacs T. Cool channel subunits reveal their independent interactions with menthol. The Journal of Physiology 2011;589 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.219543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borhani Haghighi A, Motazedian S, Rezaii R, et al. Cutaneous application of menthol 10% solution as an abortive treatment of migraine without aura: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossed-over study. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2010;64:451–6. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeffries O, Waldron M. The effects of menthol on exercise performance and thermal sensation: a meta-analysis. Journal of science and medicine in sport / Sports Medicine Australia 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens CJ, Mauger AR, Hassmèn P, et al. Endurance performance is influenced by perceptions of pain and temperature: theory, applications and safety considerations. Sports Medicine 2018;48:525–37. 10.1007/s40279-017-0852-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noehren B, Andersen A, Hardy P, et al. Cellular and morphological alterations in the vastus lateralis muscle as the result of ACL injury and reconstruction. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2016;98:1541–7. 10.2106/JBJS.16.00035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milsom J, Barreira P, Burgess DJ, et al. Case study: muscle atrophy and hypertrophy in a premier League soccer player during rehabilitation from ACL injury. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 2014;24:543–52. 10.1123/ijsnem.2013-0209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gokeler A, Bisschop M, Benjaminse A, et al. Quadriceps function following ACL reconstruction and rehabilitation: implications for optimisation of current practices. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 2014;22:1163–74. 10.1007/s00167-013-2577-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sattler M, Dannhauer T, Ring-Dimitriou S, et al. Relative distribution of quadriceps head anatomical cross-sectional areas and volumes—Sensitivity to pain and to training intervention. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger 2014;196:464–70. 10.1016/j.aanat.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galeotti N, Di Cesare Mannelli L, Mazzanti G, et al. Menthol: a natural analgesic compound. Neuroscience Letters 2002;322:145–8. 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02527-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Secrist ES, Freedman KB, Ciccotti MG, et al. Pain management after outpatient anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med 2016;44:2435–47. 10.1177/0363546515617737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chmielewski TL, Jones D, Day T, et al. The association of pain and fear of movement/reinjury with function during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008;38:746–53. 10.2519/jospt.2008.2887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Filbay SR, Ackerman IN, Russell TG, et al. Health-related quality of life after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2014;42:1247–55. 10.1177/0363546513512774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Wluka AE, Berry PA, et al. Increase in vastus medialis cross-sectional area is associated with reduced pain, cartilage loss, and joint replacement risk in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2012;64:3917–25. 10.1002/art.34681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheon Y-H, Kim H-O, Suh YS, et al. Relationship between decreased lower extremity muscle mass and knee pain severity in both the general population and patients with knee osteoarthritis: findings from the KNHANES V 1-2. Plos One 2017;12:e0173036 10.1371/journal.pone.0173036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lima LV, Abner TSS, Sluka KA. Does exercise increase or decrease pain? central mechanisms underlying these two phenomena. The Journal of Physiology 2017;595:4141–50. 10.1113/JP273355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, et al. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;1 10.1002/14651858.CD011279.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johar P, Grover V, Topp R, et al. A comparison of topical menthol to ice on pain, evoked tetanic and voluntary force during delayed onset muscle soreness. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2012;7:314–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]