Abstract

Histamine is released within skeletal muscle during exercise. In humans, antihistamines have no effect on speed, power output, or time-to-completion of short-duration high-intensity exercise. In mice, blocking histamine’s actions decreases speed and duration of endurance tasks. It is unknown if these opposing outcomes are the result of differences in histamine’s actions between species or are related to duration and/or intensity of exercise, as blocking histamine during endurance exercise has not been examined in humans.

Purpose:

Determine the effects of histamine-receptor antagonism on cycling time-trial performance in humans, with and without a preceding bout of sustained steady-state exercise.

Methods:

Eleven (3F) competitive cyclists performed six 10-km time-trials on separate days. The first two time-trials served as familiarization. The next four time-trials were performed in randomized-block order, where two were preceded by 120 min of seated rest (Rest) and two by 120 min of cycling exercise (Exercise) at 50% VO2peak. Within each block, subjects consumed either combined histamine H1 and H2 receptor antagonists (Blockade) or Placebo, prior to the start of the 120-min Rest/Exercise.

Results:

Blockade had no discernible effects on hemodynamic or metabolic variables during Rest or Exercise. However, Blockade increased time-to-completion of the 10-km time-trial compared to Placebo (+10.5 ± 3.7 s, P < 0.05). Slowing from Placebo to Blockade was not different between Rest (+8.7 ± 5.2 s) and Exercise (+12.3 ± 5.8 s, P = 0.716).

Conclusion:

Exercise-related histaminergic signaling appears inherent to endurance exercise and may play a role in facilitating optimal function during high-intensity endurance exercise.

Keywords: Time-trial, Athlete, Antihistamine, Endurance Exercise

INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle interstitial histamine concentrations are low at rest, but increase in active musculature during moderate-intensity endurance exercise (1). Histamine is released by mast cell degranulation and produced through de novo synthesis (1), secondary to increased activity of the enzyme histidine decarboxylase (HDC) (1,2). Mast cell degranulation has been shown to occur with stimuli associated with exercise such as hypoxia, increased temperature, vibration, and hyperosmolality (3). While HDC is present in high concentrations within mast cells, there is also evidence it may be expressed within skeletal muscle myocytes (2,4) and endothelial cells (4,5). HDC continually synthesizes minute quantities of histamine in resting muscle (4), but further activity can be induced by stimuli associated with exercise such as hypoxia (6), increased temperature (7,8), and decreased pH (8). Along these lines, experiments in exercising mice or using repeated electrically stimulated contractions in isolated muscle have demonstrated that the magnitude of increased HDC activity is proportional to the duration of exercise (9). Since histamine is rapidly degraded by cytosolic and membrane bound enzymes or reabsorbed by mast cells, it has a short half-life (~100 s). Therefore, histamine may have an important autocrine and paracrine action within skeletal muscle during sustained activity (10,11).

Blocking histamine’s actions in mice reduced endurance capacity during moderate-intensity long-duration exercise. In humans, blocking histamine actions has shown no discernable effect on short-duration high-intensity exercise but endurance outcomes have not been examined. Specifically, histamine H1 receptor antagonism in mice decreased the activity of a multi-hour duration gnawing test (10), the duration of multi-hour forced walking test, and in some cases required a reduction in walking speed to allow the mice to walk for multiple-hours (11,12). Similarly, blocking histamine H2 receptors tended to reduce the duration of walking tests in mice, but the effect was smaller than blockade of H1 receptors (11). Blocking H1 receptors in humans had no effect on a velocity spectrum test designed to measure quadricep isokinetic muscle strength at multiple angular velocities or quadricep contraction duration (13). Additionally, blocking H1 receptors in humans had no effect on a progressive graded treadmill test to volitional exhaustion (VO2peak tests), 30 min of steady state submaximal treadmill running at 55% of VO2peak, or running intervals consisting of alternating 30 s high-intensity sprints and 30 s rest (14,15). However, because the maximum length of human testing was brief (at most 30 min), these studies do not reveal the effect of histamine on sustained endurance task performance. Therefore, the reduced task performance in mouse based studies but not in human studies could be due to histamine’s actions related to the intensity and/or duration of the exercise tests.

Our lab has shown that in humans, 60 min of moderate-intensity exercise increased histamine concentrations within skeletal muscle (1). This intramuscular histamine activated H1 and H2 receptors on the vascular endothelium and smooth muscle, respectively, to induce a dilation of resistance arterioles, and increase local blood flow for several hours following exercise (16). Histamine plays a similar vasodilatory role in immune and inflammatory responses, in which increased local histamine concentrations increased blood flow and capillary permeability (17). It is unknown if histamine has a similar vasodilatory influence on blood vessels within the muscle during endurance exercise. Given the proximity of histamine containing and producing cells to the skeletal muscle vasculature and the physiological actions of histamine, it is a reasonable premise that exercise induced increases in intramuscular histamine contribute to dilation and increased blood flow during exercise.

If histamine aids in increasing blood flow during exercise, blocking this action could decrease nutrient and oxygen delivery as well as carbon dioxide and metabolite removal. The potential perfusion to metabolism mismatch will have a larger impact on longer-duration exercise compared to short-duration exercise, and could be an explanation for the decreased endurance task performances observed in mice (9–12) but absent in short-duration exercise studies in humans (13–15) in response to histamine blockade.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to gain insight into histamine’s role in endurance exercise in humans, and potentially reconcile the contrasting results between human and animal studies. Specifically, on multiple days, human subjects performed short-duration high-intensity exercise performance tests following a time-matched period of rest or endurance exercise. Subjects performed the tests in a condition where histamine’s effects on H1 and H2 receptors were blocked and in a placebo condition. Prior to the study, it was hypothesized that blocking both H1 and H2 receptors would increase the time-to-completion of a fixed-distance time-trial compared to placebo, and the effect would be greater following an endurance-exercise bout.

METHODS

Subjects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Oregon. Eleven (3 female, 8 male) healthy, non-smoking individuals volunteered for the present study. Each volunteer gave written and informed consent prior to participation and the study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All volunteers were competitive cyclists with a USA cycling race Category 1, 2, or 3 classification and a history of racing within the past year. No subjects were using over-the-counter or prescription medications at the time of the study, with the exception of oral contraceptives. For female volunteers, menstrual cycle phase was not controlled for within or between subjects and the use of oral contraceptives continued as directed by their physician throughout the duration of the study. The multi-day study was organized around training, work, and family schedules.

Experimental design

The study consisted of seven visits: one screening, two familiarization, and four double-blind placebo-controlled testing visits. All volunteers were required to abstain from caffeine, alcohol, and strenuous exercise for 24 h prior to each visit. A 24-h food diary was provided to the subjects prior to the first testing visit, and food intake was matched as close as possible by the subjects before testing visit 2, 3, and 4.

Screening visit

An initial screening visit was completed to expose the subjects to all testing procedures and obtain demographic and anthropometric information (age, height, weight) including measurement of 3-site skin-fold body-fat estimate (triceps, supra-iliac, and mid-thigh for females; chest, abdominal, mid-thigh for males). Subjects then completed a 10-s maximal sprint test for anaerobic power, a cycling VO2Peak test for aerobic capacity, and an isometric knee-extension strength test.

Familiarization Visits

Subjects performed two familiarization 10-km cycling time-trials that were separated by 3 to 7 days. Prior to each time-trial, an isometric knee-extension strength test was performed. Following a 10-min warm-up at a self-selected pace, blood glucose and lactate as well as rating of perceived exertion were measured, and then subjects performed a 10-km time-trial. If the difference in time-to-completion of the two visits was large (~30 s), subjects were asked to perform a third familiarization (this was done for one subject, as noted in the results). Immediately following the time-trials (within 30 s) blood glucose and lactate as well as rating of perceived exertion were measured. Isometric knee-extension strength was measured 3 min following the time trial completion.

Testing Visits

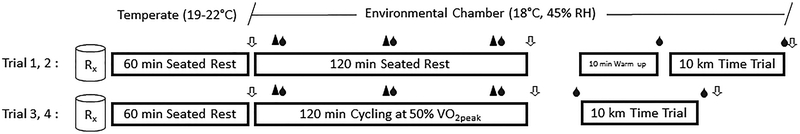

All testing visits were scheduled so that the 10-km time-trials occurred at the same time of day as the familiarization time-trials to reduce the potential influence of circadian rhythms on muscle blood flow and exercise performance. Subjects were randomized after the familiarization visits to receive either placebo pills (Placebo) or combined H1/H2 histamine receptor antagonists (Blockade) for the first two visits (Rest) and again for the second two visits (Exercise). Subjects completed a 10-km time-trial after 120-min seated rest (Rest) in the first two testing visits (1 and 2) and after 120-min cycling exercise (Exercise) in the last two visits (3 and 4), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study time line. After ingestion of Placebo or Blockade (Rx), volunteers performed either 120-min seated Rest (Visit 1 and 2) or 120-min cycling Exercise at 50% of VO2peak (Visit 3 and 4). Each arrow (⇩) represents a time where isometric knee-extension strength and body weight were measured. The blood drop (●) indicates a time point where blood was sampled. The black triangle (▲) represents a 5-min period when VO2, cardiac output, blood pressure, and perceived exertion were recorded. Testing visits 1 and 2 included a 10-min warm-up period in preparation for the 10-km time-trial; this was not included following the 120-min of cycling exercise.

Upon arriving to the lab, subjects ingested either Placebo or Blockade pills with ~90 ml of water and were seated in a temperate room (19–22°C) for 60-min before the start of Rest/Exercise. A measure of nude body weight was obtained, and then subjects were moved to an environmental chamber controlled at 18°C and 45% relative humidity (Tescor, Warminster, PA) for the remainder of the visit. Baseline measures of isometric knee-extension strength, heart rate, blood pressure, cardiac output, blood glucose and lactate, and rating of perceived exertion were made before 120-min seated Rest/Exercise. For Rest, subjects sat in a padded phlebotomy chair. For Exercise, subjects were seated on their own bikes on a CompuTrainer (RacerMate Inc., Seattle, WA, USA) computer-integrated cycle ergometer and the workload was set at a wattage corresponding to 50% of peak oxygen uptake. The CompuTrainer-bike interface was calibrated upon each visit to provide a press-on force of 2.12 to 2.14 pounds between the friction generator and the back tire of the bike. Maintaining the press-on force between visits controlled for any change in tire air pressure that might have existed between trials. The CompuTrainer was set to maintain a constant power output, allowing the subjects to self-select and vary pedal cadences throughout the 120-min. Measures of cardiac output, heart rate, blood pressure, blood glucose and lactate, and perceived exertion were made at 15, 60, and 105 min during Rest/Exercise. Subjects were provided with ~ 90 ml of Gatorade (Thirst Quencher lemon-lime, orange, or fruit punch flavored; ~300 mOsmol/L, 230 mg sodium, 65 mg potassium, 0 g Fat, 31 g carbohydrate, 0 g protein per 500 mL) every 20 min, for a total of 533 ml (18 oz) during the 120-min. In addition to Gatorade, subjects were given water ad libitum during Exercise. At the completion of Rest/Exercise, a measure of isometric knee-extension strength was recorded. After Rest, subjects completed a 10-min warm-up at a self-selected power output prior to the time-trial (Visit 1 and 2), whereas after Exercise, subjects transitioned directly to the time-trial without an additional warm-up (Visit 3 and 4). Immediately after the time-trial, perceived exertion, blood glucose and lactate, isometric knee-extension strength, and nude body weights were obtained (Figure 1). For the majority of subjects (7 of 11), each testing visit was performed 7 days apart, and for all subjects, they were separated by at least 72 h.

Measurements

10-s Maximal Sprint Test

Subjects were seated on a cycle ergometer (Excalibur Sport V2; Lode BV, Groningen, The Netherlands) and performed a 5-min warm-up at power output of 100 Watts at a self-selected cadence. Immediately following the warm up, subjects completed a 10-s sprint test of anaerobic power output. The torque factor was set to 0.70 Nm (Wingate for Windows software version 1; Lode BV, Groningen, The Netherlands). The final two subjects were unable to complete the sprint test due to computer-ergometer interface malfunctions (reported in Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| n | 11 (3F, 8M) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27 ± 5 |

| Height (cm) | 176.6 ± 9.2 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.29 ± 12.44 |

| Body Fat (%) | 16.1 ± 9.6 |

| Peak Power Output (W)* | 897 ± 262 |

| VO2 peak (ml·kg−1·min−1) | 58.7 ± 6.3 |

| Isometric knee-extension Force (N) | 603.7 ± 224.4 |

| 50% VO2 peak Workload (W) | 160 ± 30 |

Values are means ± SD.

n = 9.

VO2Peak

After the sprint test, subjects performed an additional 5- to 10-min warm-up, cycling at 1.5 Watts per kilogram of body weight at a self-selected pedal cadence. Subjects then performed an incremental cycle ergometer exercise test (Lode Excaliber, Groningen, The Netherlands) comprised of 1-min workload increments of 25–30 watts to determine peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak). The workload increment was based on the subject’s self-reported training load and intensity. Whole-body oxygen uptake was measured throughout the test via a mixing chamber system (Parvomedics, Sandy, UT) integrated with a mass spectrometer (Marquette MGA 1100, MA Tech Services, St. Louis, MO). The test was terminated when subjects were unable to maintain a pedal cadence of 40 revolutions per min. Subjects had obtained a respiratory exchange ratio of 1.13 ± 0.06 (mean ± SD), a heart rate of 95 ± 4% (mean ± SD) of age-predicted maximum, and reached subjective exhaustion [rating of perceived exertion on the Borg scale of 19–20]. The VO2peak test was performed for estimation of a 50% workload for testing visits 3 and 4.

Knee-Extension Strength Testing

Maximal voluntary isometric force of the right knee extensors was determined using a custom-built knee-extension apparatus and interfaced with a commercially available strain gauge (DP25-S, Omegadyne Inc. Sunbury, OH, USA). The knee angle was set to 45˚ of knee extension and subjects performed two to three maximal knee extension contractions with ~30 s rest between attempts. The greatest contractile force was accepted as a maximal value using the other trials as verification. Additional trials were performed as needed if trials did not agree within 10%.

10-km Time-Trial

The 10-km time-trials were performed on a computer-integrated cycle ergometer (CompuTrainer) using the subject’s own racing bike. The time-trial was implemented using the manufacturer’s cycle ergometer computer program that provided a race simulation. Subjects were instructed to complete the time-trial as rapidly as possible and were blinded to feedback (i.e. time, pedal cadence, heart rate, power output) but were given verbal cues indicating remaining distance at each 1 km, and at 500 m remaining. At the completion of each 1 km, split time and heart rate (H1 heart rate sensor, Polar, Lake Success, NY) were recorded but not shared with the subject.

The time-trials were performed adhering to the standards outlined by Currell (18). During the time-trials there was: 1) no feedback on performance, 2) no distractions, 3) no encouragement, 4) no physiological measures (except for heart rate), 5) no performance cues, 6) temperature and humidity were controlled, and 7) subjects always used their own bike equipment which was not altered between trials (i.e. gear components, seat, tires etc). Time-trials using these guidelines have been shown to be highly reproducible, exhibit a low day-to-day coefficient of variation, and are likely to show meaningful differences for an intervention (18). Time-trials in competitive cyclists also have a high logical validity as they are “real world” type tests, are reproducible (coefficient of variance = 1.1 ± 0.9 % ), and are correlated with on-the-road competitions (19).

A 10-km distance for the time-trial was selected for a number of reasons. First, as the duration of time to complete the task was approximately 15–20 min, it was of sufficient length to primarily challenge the aerobic system where muscle blood flow is an important performance determinant, but not so long as to introduce confounding influences on performance (i.e. dehydration, mental fatigue). Second, many cyclists have experience performing hard efforts of this duration, providing “real world” or ecological validity. Third, for comparison purpose, it is a common test in the human performance/exercise physiology literatures.

Histamine H1- and H2-Receptor Blockade

Oral administration of 540 mg of fexofenadine, a selective H1-receptor antagonist, reaches peak plasma concentrations within 1 h and has a 12 h half-life (20). Oral administration of 300 mg ranitidine, a selective H2-receptor antagonist, reaches peak plasma concentration within 2 h and has a 3 h half-life (21). This dosage of histamine-receptor antagonists results in more than 90% inhibition of histamine H1 and H2 receptors lasting for 6 h after administration (21). Fexofenadine and ranitidine are not thought to cross the blood-brain barrier or to have sedative effects (20). Importantly, histamine H1- and H2-receptor antagonism does not alter blood flow, heart rate, blood pressure, or smooth muscle tone at rest (22–24).

Placebo

The placebos were manufactured by a compounding pharmacy (Creative Compounds, Wilsonville, OR) and contained the inactive ingredients of the fexofenadine and ranitidine tablets.

Body Weight

Nude body weight was recorded before and after all testing visits. Weights were recorded to the nearest 0.1 g (Sartorius model CIS IS64FEG-S, Elk Grove IL). Body weights were monitored to exclude/account for dehydration as possible causative factor of fatigue during the 10-km time-trials. Fluid intake/loss was documented with the combination of measured body weights, including those taken before and after urination/defecation, and changes in water bottle weights.

Rating of Perceived Exertion

Volunteers were asked to rate their current level of exertion “right now” on a 6–20 scale before (at rest) and at 15, 60, and 105 min of the Rest/Exercise bout and as well as just prior (at rest) to the time trial. Immediately upon completion of the time trial volunteers were also asked to rate their level of exertion at the end of the trial (“how hard were you working at the end of the time trial”). We chose to query the subject immediately upon completion instead of during the time trial to avoid disturbing the cyclists’ efforts.

Blood Glucose/Lactate

Blood was obtained from the left and right earlobes with single use safety lancets (Unistik 3, Owen Mumford, Oxfordshire, UK). Blood was analyzed for glucose (Precision Xtra, Abbot Diabetes Care, Alameda, CA) and lactate concentrations (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA) in duplicate and values were averaged.

Heart Rate and Arterial Pressure

Heart rate was monitored using a three-lead electrocardiogram and arterial pressure was measured on the right brachial artery using an automated auscultometric sphygmomanometer (Tango+, SunTech Medical, Raleigh, NC, USA). Mean arterial pressure was calculated as diastolic pressure plus 2/3 pulse pressure (systolic pressure - diastolic pressure) and reported in mmHg.

Cardiac Output, Stroke Volume, Total Peripheral Resistance, and Systemic Vascular Conductance.

Cardiac output was estimated by using an open-circuit acetylene washin method. This method allows for noninvasive estimation of cardiac output. Subjects breathed a gas mixture containing 0.6% acetylene, 9.0% helium, 20.9% oxygen, and balanced nitrogen for 8 breaths via a two-way non-rebreathing valve attached to a pneumatic sliding valve. During the washin phase, breath-by-breath acetylene and helium uptake were measured by a respiratory mass spectrometer (Perkins-Elmer MGA 1100) and total volume was measured via a pneumotach (model 3700, Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, MO) linearized and calibrated by using test gases before each testing day. Total peripheral resistance was calculated as the mean arterial pressure divided by cardiac output (expressed as mmHg·min·ml−1) and systemic vascular conductance as the reciprocal of resistance (expressed as ml·min−1·mmHg−1).

Sample Size Estimation

A repeated measures ANOVA analysis selecting conventional α (0.05) and β (0.20) parameters indicated that nine to fourteen subjects would provide adequate power to detect a 1.5 to 2% change in time trial performance (15.1 −20.2 s) based off the mean finishing time of the familiarization trials (1005 s) and the standard deviation of the differences between the two trials (13.8 s). A 1.5 to 2% change was selected because previous analyses of similar length competitions have been meaningfully impacted by a ~1 to 1.5% change of within athlete performance (25).

Data and statistical Analysis

Results were not separated for a sex comparison as only 3 females volunteered for the study and the general pattern of slowing was similar between females and males. Menstrual cycle phase was not controlled for in the females as there is a strong consensus that there is no change in aerobic (26) nor anaerobic performance (27) over the menstrual cycle and females train and compete throughout all phases of their menstrual cycle.

Statistical inferences were drawn from a combination of paired t-tests and 2- or 3-way repeated measures ANOVAs with a priori contrasts, depending on the sampling of outcome measures, and models were run using SAS (Proc MIXED, SAS version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA). For all tests, significance was set at P < 0.05. All data are presented as mean ± SEM, unless stated otherwise (i.e., Table 1). A change score, calculated from time-to-completion as [(Placebo – Blockade) / Placebo)] and expressed as percent (%) change ± 95% CI was calculated for an estimation of the true value of the change in performance. A traditional effect size (Cohen’s dz) was calculated for an estimation in the strength of the percent change in performance.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

Subject’s demographic and anthropometric characteristics obtained from the screening visit including age, height, weight, body fat percentage, peak power output, VO2peak, isometric knee-extension strength, and 50% VO2peak workload are presented in Table 1.

Responses during Familiarization Visits and Time-Trial Reproducibility

One subject performed three familiarization time-trials, as their time-to-completion in the second familiarization was 27.7 s slower than the first. For this subject, only the two fastest times were used for analysis. There were no differences in time-to-completion between the first and second familiarization time-trial (1008.6 ± 25.9 s vs. 1001.7 ± 26.7 s; P = 0.128). The subjects demonstrated consistency in their efforts as the coefficient of variation between trials was 0.97%. The last kilometer of the time-trial was the fastest and the first kilometer was the slowest (P < 0.05), but pacing for each kilometer of the time-trial did not differ between trial 1 and 2 (P = 0.504). Likewise, while heart rate increased within the time-trials (main effect for time P < 0.05), it did not differ between trial 1 and 2 (P = 0.381) (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, Familiarization time-trials). There were no differences in blood glucose and lactate concentrations or strength change between trials (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, Familiarization trials).

Responses during 120-min Rest and Exercise

During 120-min Rest, there were no changes in any hemodynamic or metabolic measure in either Placebo or Blockade (Table 2). During 120-min Exercise, subjects cycled at a power output of 160 ± 30 W (mean ± SD) and all hemodynamic and metabolic measures were elevated above pre-exercise and were higher than Rest (P < 0.05), with the exception of blood lactate concentrations which did not differ between Exercise and Rest (P = 0.819). There were no differences in hemodynamic, metabolic, or perceptual measures within or between the Placebo and Blockade conditions during 120-min of Exercise (Table 2).

Table 2.

120-minutes Rest and Steady State Cycling

| Time | P value | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Drug | Pre | 10 | 60 | 110 | Drug | Phase | Drug*Phase | Time | Drug*Time | Phase*Time | Drug*Phase*Time | |

| Heart Rate (beats·min−1) | Rest | Placebo | 57 ± 1 | 56 ± 2 | 58 ± 2 | 54 ± 2 | 0.281 | <0.05 | 0.518 | <0.05 | 0.904 | <0.05 | 0.879 |

| Blockade | 55 ± 3 | 55 ± 3 | 56 ± 3 | 55 ± 2 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 63 ± 3 | 134 ± 5 | 138 ± 5 | 141 ± 6 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 63 ± 3 | 127 ± 7 | 134 ± 5 | 138 ± 6 | |||||||||

| VO2 (l·min−1) | Rest | Placebo | 0.301 ± 0.018 | 0.289 ± 0.017 | 0.297 ± 0.018 | 0.300 ± 0.016 | 0.405 | <0.05 | 0.345 | <0.05 | 0.889 | <0.05 | 0.944 |

| Blockade | 0.276 ± 0.018 | 0.294 ± 0.013 | 0.303 ± 0.013 | 0.291 ± 0.016 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 0.385 ± 0.028 | 2.225 ± 0.120 | 2.259 ± 0.148 | 2.301 ± 0.143 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 0.362 ± 0.025 | 2.342 ± 0.140 | 2.385 ± 0.176 | 2.453 ± 0.188 | |||||||||

| Respiratory Exchange Ratio | Rest | Placebo | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 0.820 | <0.05 | 0.208 | 0.563 | 0.961 | 0.119 | 0.709 |

| Blockade | 0.83 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.89 ± 0.02 | 0.87 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 0.83 ± 0.02 | |||||||||

| Respiratory Rate (breaths·min−1) | Rest | Placebo | 15 ± 1 | 14 ± 1 | 14 ± 1 | 14 ± 1 | 0.126 | <0.05 | 0.792 | <0.05 | 0.409 | <0.05 | 0.683 |

| Blockade | 16 ± 1 | 16 ± 2 | 14 ± 1 | 14 ± 1 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 15 ± 1 | 22 ± 1 | 22 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 14 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 24 ± 1 | 24 ± 1 | |||||||||

| Systolic Pressure (mmHg) | Rest | Placebo | 127 ± 5 | 128 ± 5 | 126 ± 5 | 132 ± 5 | 0.483 | <0.05 | 0.628 | <0.05 | 0.933 | <0.05 | 0.827 |

| Blockade | 129 ± 5 | 126 ± 4 | 126 ± 4 | 130 ± 4 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 137 ± 5 | 190 ± 8 | 193 ± 10 | 185 ± 9 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 134 ± 4 | 190 ± 7 | 181 ± 9 | 185 ± 8 | |||||||||

| Diastolic Pressure (mmHg) | Rest | Placebo | 74 ± 2 | 74 ± 2 | 77 ± 2 | 78 ± 2 | 0.991 | <0.05 | 0.824 | <0.05 | 0.444 | <0.05 | 0.995 |

| Blockade | 73 ± 2 | 76 ± 2 | 75 ± 3 | 81 ± 3 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 77 ± 2 | 61 ± 3 | 64 ± 5 | 59 ± 4 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 77 ± 2 | 61 ± 3 | 60 ± 3 | 63 ± 4 | |||||||||

| Mean Arterial Pressure (mmHg) | Rest | Placebo | 91 ± 3 | 92 ± 2 | 94 ± 2 | 96 ± 2 | 0.624 | <0.05 | 0.635 | 0.064 | 0.569 | 0.264 | 0.893 |

| Blockade | 92 ± 3 | 92 ± 3 | 92 ± 3 | 97 ± 2 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 97 ± 2 | 104 ±4 | 107 ± 4 | 101 ± 4 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 96 ± 2 | 104 ± 3 | 100 ± 3 | 103 ± 5 | |||||||||

| Cardiac Output (l·min−1) | Rest | Placebo | 6.43 ± 0.46 | 6.04 ± 0.51 | 5.68 ± 0.46 | 6.30 ± 0.63 | 0.706 | <0.05 | 0.821 | <0.05 | 0.948 | <0.05 | 0.783 |

| Blockade | 6.39 ± 0.45 | 5.75 ± 0.30 | 5.81 ± 0.40 | 5.72 ± 0.35 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 6.55 ± 0.34 | 14.29 ± 0.59 | 14.70 ± 0.64 | 14.51 ± 0.70 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 5.79 ± 0.63 | 14.18 ± 0.90 | 14.80 ± 1.07 | 14.09 ± 1.29 | |||||||||

| Stroke Volume (ml) | Rest | Placebo Blockade | 113 ± 8 | 109 ± 9 | 99 ± 7 | 118 ± 12 | 0.829 | 0.448 | 0.999 | 0.900 | 0.880 | 0.282 | 0.450 |

| Blockade | 121 ± 12 | 108 ± 9 | 106 ± 10 | 108 ± 10 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 108 ± 9 | 107 ± 5 | 107 ± 5 | 104 ± 6 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 94 ± 7 | 114 ± 9 | 111 ± 9 | 110 ± 101 | |||||||||

| Toal Peripheral Resistance (mmHg·min·l−1) | Rest | Placebo | 14.6 ± 0.6 | 15.9 ± 0.8 | 17.0 ± 0.8 | 16.1 ± 0.9 | 0.287 | <0.05 | 0.985 | <0.05 | 0.495 | <0.05 | 0.627 |

| Blockade | 15.0 ± 1.0 | 16.4 ± 0.8 | 16.4 ± 1.0 | 17.6 ± 1.1 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 15.2 ± 0.7 | 7.4 ± 0.4 | 7.5 ± 0.5 | 7.2 ± 0.5 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 16.9 ± 0.7 | 7.7 ± 0.6 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 7.2 ± 0.6 | |||||||||

| Systemic Vascular Conductance (ml·mmHg−1·min−1) | Rest | Placebo | 70 ± 4 | 65 ± 5 | 61 ± 4 | 65 ± 6 | 0.983 | <0.05 | 0.642 | <0.05 | 0.679 | <0.05 | 0.796 |

| Blockade | 70 ± 4 | 62 ± 3 | 64 ± 4 | 59 ± 3 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 67 ± 3 | 140 ± 9 | 138 ± 9 | 143 ± 9 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 60 ± 2 | 138 ± 10 | 149 ± 11 | 148 ± 12 | |||||||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | Rest | Placebo | 81 ± 5 | 89 ± 3 | 98 ± 4 | 93 ± 4 | 0.674 | <0.05 | 0.809 | 0.115 | 0.829 | <0.05 | 0.754 |

| Blockade | 85 ± 4 | 90 ± 5 | 93 ± 4 | 93 ± 4 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 82 ± 5 | 67 ± 3 | 72 ± 2 | 72 ± 2 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 80 ± 3 | 66 ± 3 | 71 ± 3 | 72 ± 2 | |||||||||

| Lactate (mmol/l) | Rest | Placebo | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.424 | 0.819 | 0.789 | 0.195 | 0.934 | <0.05 | 0.982 |

| Blockade | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | |||||||||

| Rating of Perceived Exertion | Rest | Placebo | 6 ± 0 | 6 ± 0 | 6 ± 0 | 6 ± 0 | 0.560 | <0.05 | 0.560 | <0.05 | 0.982 | <0.05 | 0.982 |

| Blockade | 6 ± 0 | 6 ± 0 | 6 ± 0 | 6 ± 0 | |||||||||

| Exercise | Placebo | 6 ± 0 | 9 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | ||||||||

| Blockade | 6 ± 0 | 10 ± 1 | 11 ± 0 | 12 ± 1 | |||||||||

Values are means ± SEM.

Responses during Time-Trials

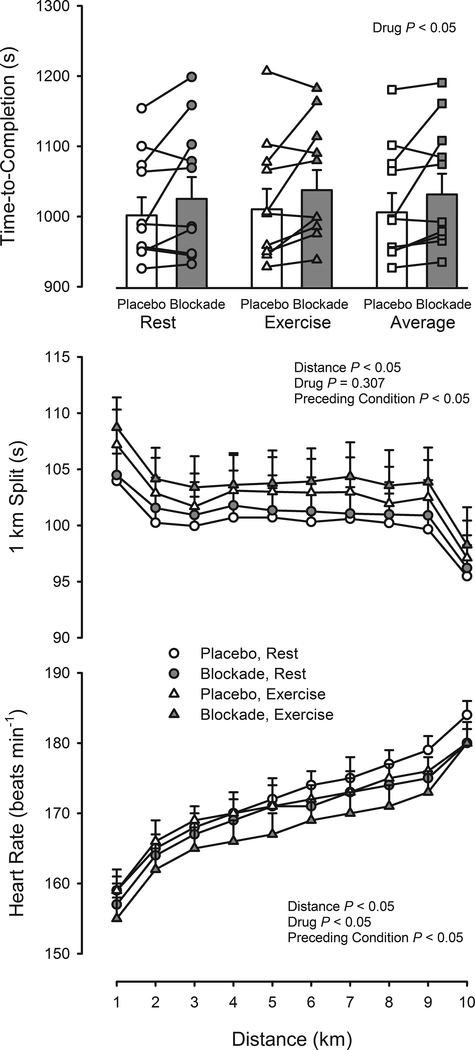

Time-to-completion of the time-trial was slower for Blockade compared to Placebo (+10.5 ± 3.7 s, Range −15.9 to +53.1 s, P < 0.05), as shown in Figure 2. There was a trend for time-to-completion to be slower after 120-min Exercise versus Rest (P = 0.057) but this was not further compounded by Blockade in comparison to Placebo as the slowing was +8.7 ± 5.2 s following Rest and +12.3 ± 5.8 s following Exercise (P = 0.716). The pattern of pacing (Figure 2) was similar to the familiarization time-trials, the first km was the slowest, the last km was the fastest (P < 0.05), and was not different in Blockade versus Placebo (P = 0.307). On average, pacing of each km was slower following Exercise versus Rest (P < 0.05) but did not differ between Blockade and Placebo (P = 0.926). Heart rate during the time-trial was higher after 120-min Exercise versus Rest (P < 0.05) and lower for Blockade compared to Placebo (P < 0.05), as shown Figure 2. Heart rate increased throughout the time-trial (P < 0.05), but the pattern was not affected by Blockade versus Placebo (P = 0.566) or by prior Exercise versus Rest (P = 0.998).

Figure 2.

Testing visit time-trials. Upper panel: Effect of prior Exercise versus Rest and Blockade versus Placebo on 10-km time-to-completion. Values are means ± SEM, as well individual values. Middle panel: Effect of prior Exercise versus Rest and Blockade versus Placebo on split time at 1-km increments. The first km was the slowest and the last km was the fastest (P < 0.05). Values are means ± SEM. Lower panel: Effect of prior Exercise versus Rest and Blockade versus Placebo on heart rate at 1-km increments. Values are means ± SEM.

Changes in Body Weight

There were no differences in nude weight at the beginning of the testing visits (P = 0.547). There was a trend for lower nude weights upon completion of 120-min Exercise compared to Rest (P = 0.081), but this was not affected by Blockade versus Placebo (P = 0.846). Subjects completed the Exercise trials slightly hypohydrated (Placebo −1.25 ± 0.18%, Blockade −1.46 ± 0.18% of pre-trial body weight). In five of the time-trials that were preceded by 120-min exercise, subjects exceeded a 2% weight loss by the end of the time-trial. The distribution of those five trials included two subjects in both their Placebo and Blockade visits, and one subject during only their Blockade visit. The one subject that exceeded 2% weight loss in only the Blockade condition completed the time trial 15.9 s faster than the Placebo condition, opposite of the general trend of the other subjects. Therefore, in consideration of the overall pattern across subjects, as described above, dehydration exceeding a 2% body weight loss does not appear to be an important confound for interpreting the effect of Blockade versus Placebo.

Analysis of Change Scores

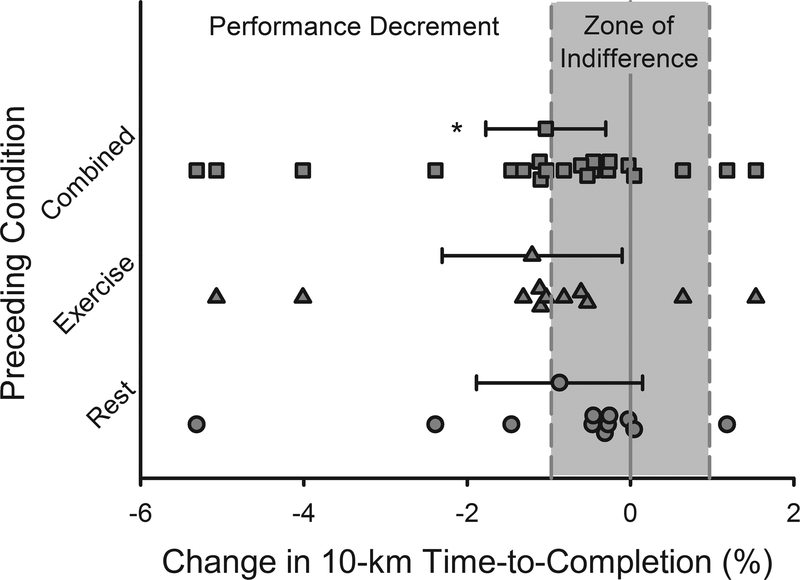

As noted above, the coefficient of variation between repeat performances from the familiarization time-trials was 0.97%. This was compared to a change score and 95% CI along with individual change scores presented in Figure 3. The percent change from Placebo to Blockade for all trials was −1.04% (95% CI: −1.77 to −0.30%) and in accordance with the conventional 3-way repeated measures ANOVA, the 95% CI limits do not cross the ‘0’ percent change. Following 120-min Rest, the change score was −0.87% (95% CI: −1.88 to 0.15%) and following 120-min Exercise, the change score was −1.20% (95% CI: −2.31 to −0.10%).

Figure 3.

Effect of Blockade versus Placebo as a percent change in 10-km time-to-completion (Combined = Rest and Exercise together) and with and without prior exercise (Exercise or Rest). Values are means ± 95% confidence intervals, as well as individual values. Yellow shaded area represents a zone of indifference (± 0.97%) based on day-to-day performance variability measured during the familiarization trials.

Additional outcome measures

There were no differences in blood glucose, blood lactate, rating of perceived exertion, or isometric knee-extension muscle strength preceding the time-trial in any condition (Table 3). Blood glucose increased from before to after Rest (P < 0.05), decreased from before to after Exercise (P < 0.05), but was not affected by Blockade versus Placebo (P = 0.809). Blood lactate increased from before to after the time-trial (P < 0.05). The rise was greater following Rest versus Exercise (P < 0.05), but there was no effect of Blockade versus Placebo (P = 0.496). Rating of perceived exertion increased from before to after the time-trial (P < 0.05), but there was no effect of Exercise versus Rest (P = 0.663) or of Blockade versus Placebo (P = 0.827). Isometric knee-extension strength was highly variable within and between subjects and therefore showed no clear indication of any change based on prior exercise (P = 0.586) or drug condition (P = 0.722).

Table 3.

Time Trials

| Rest | Exercise | P value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Blockade | Placebo | Blockade | Drug | Phase | Drug* Phase | Time | Drug* Time | Phase* Time | Drug*Phase* Time | ||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | Pre | 76.6 ± 1.5 | 72.5 ± 3.9 | 85.2 ± 2.9 | 80.7 ± 4.2 | 0.185 | 0.490 | 0.500 | 0.350 | 0.971 | < 0.05 | 0.463 |

| Post | 92.3 ± 4.8 | 83.8 ± 5.1 | 75.2 ± 6.1 | 75.5 ± 4.9 | ||||||||

| Lactate (mmol/l) | Pre | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.496 | <0.05 | 0.512 | <0.05 | 0.390 | <0.05 | 0.711 |

| Post | 11.2 ± 0.8 | 10.0 ± 0.7 | 7.1 ± 1.1 | 6.8 ± 1.0 | ||||||||

| Muscle Strength (N) | Pre | 525 ± 52 | 511 ± 52 | 504 ± 60 | 504 ± 61 | 0.722 | 0.586 | 0.862 | 0.902 | 0.994 | 0.946 | 0.997 |

| Post | 530 ± 57 | 516 ± 54 | 496 ± 55 | 487 ± 58 | ||||||||

| RPE | Pre | 7 ± 1 | 6 ± 0 | 7 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 | 0.827 | 0.663 | 0.513 | <0.05 | 0.528 | 1.00 | 0.827 |

| Post | 18 ± 0 | 18 ± 0 | 18 ± 0 | 19 ± 0 | ||||||||

Values are means ± SEM. RPE, Rating of Perceived Exertion.

Subjective observations

Upon completion of both time-trials within the Rest and Exercise conditions, cyclists were asked to subjectively assess if they believed one medication resulted in an easier/faster, harder/slower, or no change in time-trial performance. Of the 22 comparisons, there were 5 reports of “no change” between the medications, 6 reports of “harder/slower” for Placebo, and 11 reports of “harder/slower” for Blockade.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of the present investigation was that taking combined histamine H1 and H2 histamine receptor antagonists slowed time-to-completion of a 10-km time-trial in competitive cyclists (+10.5 ± 3.7 s). These results suggest that exercise-induced skeletal muscle histamine production plays an inherent role in endurance exercise capacity, corroborate the evidence suggesting blocking histamine’s actions reduces endurance in mice, and expands the observations in humans beyond the prior reports that focused on short-duration high-intensity tasks. Additionally, in the setting of competitive athletics, the combination of common over-the-counter H1 and H2 receptor antihistamines have negative influences on performance that are as large as the performance enhancing effects of altitude training or caffeine ingestion (28,29).

The research design used competitive cyclists and repeated familiarization trials. The cyclists demonstrated low variability in the 10-km familiarization trials (CV = 0.97%) and this metric allowed for an in-depth analysis of performance. The 0.97% CV was used as a zone of indifference for comparing changes between the placebo and blockade conditions, i.e., comparison of the slowing of time-to-completion from placebo to blockade compared to the day-to-day variation. The slowing of performance was −1.04% (95% CI: −1.77 to −0.30%) for all trials regardless of preceding condition. Based on the kinetics of the histamine-forming enzyme, HDC, it was assumed that Blockade would have had a larger effect on performance following Exercise. Therefore, the change scores were further divided by preceding condition. The change score following Rest was −0.87% (95% CI −1.88 to 0.15%) and −1.20% (95% CI −2.31 to - 0.10%) following exercise (Figure 3). Blockade resulted in a statistically significant slowing that was not different between the Exercise and Rest conditions. In all cases, the 95% confidence interval overlapped with the 0.97% coefficient of variation around the familiarization trials indicating that part of the decreased performance could be attributable to day-to-day performance variability and the magnitude of slowing should be interpreted with caution.

Histamine in exercise responses.

In response to exercise, histamine is both released by mast cells and produced de novo by HDC within skeletal muscle (1). Mast cell degranulation has been shown to occur with direct disruption of the cell membranes (31) and exposure to substance P, bradykinin, adenosine, nerve growth factor (32), chemokines, hypoxia (33), hyperosmolaility, superoxides, increased temperature, and vibration (3). In resting skeletal muscle, HDC enzyme activity generates minute quantities of histamine (7). HDC mRNA expression, protein abundance, and activity are increased with exercise (1,2). HDC activity appears to be enhanced by increased temperature (7,8), decreased pH (8), hypoxia (6), and several signaling molecules such as interleukin-1 (2,9), all of which may play a role during repeated muscle contractions. While its specific actions during exercise are unknown, some insight can be gained from studying histamine in other contexts, such as stimulation of afferent fibers, pathophysiological reactions, and recovery from exercise.

Contributing to afferent feedback.

Histamine has the potential to modulate feedback from exercising skeletal muscle carried by muscle afferent Group III/IV nerve fibers. The Group III/IV afferent fibers, also termed chemo- and metabo-receptors are associated with the exercise pressor response and are one third of a “triad” in that they are in close proximity to mast cells and capillaries. These afferent fibers express both H1 and H2 histamine receptor subtypes that, when bound to histamine increase the firing rate of the nerves and, through a reflexive central autonomic loop, increase heart rate. Thus, it is possible that histamine receptor antagonism reduced the activity of afferent nerves, diminishing their stimulation of the cardiovascular control centers. This would be consistent with the reduced heart rate seen during time-trials with histamine-receptor antagonism (Figure 2). With reduced afferent feedback, it is possible that muscle perfusion was not well matched to metabolic demands of the exercising muscle.

Contributing to vasodilation.

During inflammatory and immune responses, histamine binds to H1 and H2 receptors, causes vascular dilation by relaxation of smooth muscle, and increases the size of inter-cellular gaps between endothelial and pericyte cells within post-capillary venules (17). The vasodilation and increased size of the gaps results in plasma effusion into tissues. Similarly, following a moderate-intensity bout of endurance exercise, histamine interacts primarily with H1 receptors on the vascular endothelium and H2 receptors on the vascular smooth muscle, leading to a sustained vasodilation of resistance arterioles (sustained post-exercise vasodilation), and contributes to post-exercise hypotension (22,34). Germane to the present study, histamine blockade in endurance-exercised mice resulted in a reduced presence of nitric oxide metabolites in the quadriceps muscles (11), suggesting that endothelium-mediated vasodilation may be stimulated by histamine during exercise.

If histamine has a vasodilatory effect within active skeletal muscle vasculature during exercise, this could facilitate oxygen delivery, nutrient delivery, and metabolite clearance during exercise. Thus, blocking these local effects may influence systemic blood flow, oxygen uptake kinetics, and skeletal muscle metabolism (e.g. glucose uptake, lactate production/removal) and, in doing so, have a negative effect on exercise performance. In this investigation, we did not attempt to measure skeletal muscle blood flow but given the large vascular bed of exercising skeletal muscle, histamine-mediated vasodilation could affect arterial pressure. However, we did not detect any change in systemic hemodynamics (total peripheral resistance or systemic vascular conductance) during 120 min of moderate-intensity steady-state exercise (Table 2). Since arterial blood pressure is highly regulated at rest and during exercise, it is possible that the impact of any potential reduction in skeletal blood flow was masked by an offsetting increase in blood flow in another vascular bed, mediated by arterial baroreflex pathways.

Similarly, there were no changes in oxygen uptake or any other hemodynamic or metabolic measure during exercise (Table 2). These results are similar to those presented by Peterlin (15) who showed no change in total peripheral resistance or respiration after H1 receptor antagonism in individuals performing 20 min of cycling at 50% VO2 peak. Thus, it remains to be seen whether histamine contributes importantly to exercise hyperemia, and whether histamine-receptor antagonists reduce skeletal muscle blood flow during exercise. However, such an effect would be consistent with the reduced performance that was observed in the present study.

Contributing to glucose delivery.

Histamine is presumed to be a major controller of the microcirculation and may play a role in facilitating movement of glucose (and other nutrients) from the microcirculation to active myocytes. During recovery from exercise, histamine receptor antagonists were found to decrease intramuscular glucose concentrations (as assessed via microdialysis) (35). Further, blocking histaminergic vasodilation following endurance exercise reduced skeletal muscle glucose delivery and blunted whole body insulin sensitivity by 25% (35,36). Interestingly, reduced glucose delivery to skeletal muscles may have a larger impact on muscle glucose uptake in individuals with the highest VO2 (37). In mice, histamine H1 receptor antagonists have been shown to reduce intramuscular glycogen content following a 3 h prolonged walking task (11). Thus, several studies in mice and humans suggest the possibility that histamine receptor blockade could affect muscle glucose uptake during exercise. However, in the present study, we found no differences in circulating blood glucose concentrations either during the steady state conditions (Table 2) or following the time-trial in response to histamine blockade (Table 3). Of note, because glucose was sampled from the ear in this study, it served as an indicator of systemic concentrations and did not reflect uptake within the skeletal muscle. Thus, it may be that blood glucose is well maintained, but less is functionally available to the exercising muscle. If so, one would predict a greater reliance (and use) of muscle glycogen, as seen in mice (11).

Overall, we note that performance in an endurance task is diminished, and we have identified several potential mechanisms that could explain why, but we were unable to pinpoint a mechanism for the slower performance based on currently available information.

Methodological considerations

Menstrual cycle phase and therefore fluctuations in sex hormones can enhance or depress the actions of some drugs. To date, no known study has documented altered pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of fexofenadine or ranitidine through different phases of the menstrual cycle or in combination with oral contraceptive use. The date of prior menses was noted before the start of the study but no effort was made to document menstrual cycle phase nor were blood concentrations of sex hormones quantified in the female or male volunteers at each time trial. Therefore, it is unknown if menstrual cycle phase, contraceptive use, or sex hormone fluctuations may have altered the potency of histamine receptor antagonists. Additionally, we did not quantify the concentrations of fexofenadine, ranitidine, or histamine in the blood or within the skeletal muscle during testing. We also acknowledge that while we blocked histamine’s actions on H1 and H2 receptors, other pathways may have been altered and contributed to the decreased time trial performance. Regardless of the unknown concentrations of sex hormones, histamine, and histamine receptor antagonists in the blood or muscle, the pattern of time trial slowing was similar between females as the males.

Importance

This study demonstrates the importance of histamine in endurance exercise. This discovery of histamine, commonly associated with immune and inflammatory responses, as being intimately involved in endurance exercise, may open up new avenues of research as the field of physiology attempts to account for the beneficial effects of exercise beyond the improvement of traditional risk factors. Additionally, these findings have implications for competitive athletes, as the difference between a gold and silver medal can be a mere 0.52%, while a fourth place finish may trail as little as 2% behind the winning time (18). In an effort to capture the valuable seconds that determine athletic victories, competitive athletes are continuously optimizing training methods and exploring legal ergogenic aids. For example, endurance athletes partake in altitude training, carbohydrate supplementation, and caffeine ingestion which have been demonstrated to improve performance ~2%, 2–3%, and up to 5% respectively (28,29). However, competitive athletics has largely ignored the potential for antihistamines, commonly used to treat allergies and acid reflux, to hinder performance. The volunteers in the current study received a one-time dose of antihistamines prior to exercise and were asymptomatic for allergies and gastrointestinal reflux; therefore, the current findings may not apply to symptomatic athletes or those taking daily antihistamine medications. But, this question is of particular relevance to endurance athletes, as they are more likely to be diagnosed with allergies and/or allergic rhinitis than the general population (38), are five-times more likely to use allergy medication than non-athletes (39), and are two-times more likely to use oral antihistamines than sprint athletes or the general population (38). Additionally, oral antihistamines are frequently used by marathon and ultramarathon runners to treat gastrointestinal reflux and ulcers (40). The present study suggests that histamine plays an important role during endurance exercise. Furthermore, when this role is disturbed, it may have detrimental effects for competitive athletes chasing narrow margins of victory.

Conclusion

In conclusion, blocking histamine’s actions had a detrimental effect on 10-km cycling time-trial performance. These findings corroborate prior observations in mice regarding the effect of antihistamines on endurance and expand the work in humans beyond the scope of earlier studies that focused on short-duration high-intensity tasks. These results also indicate that exercise associated increases in skeletal muscle histamine concentrations are inherent to the exercise response and are necessary to facilitate optimal function during high-intensity endurance exercise.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content Table 1. Familiarization Trials

Supplemental Digital Content Figure 1. Familiarization time-trials. Upper panel: Comparison of the two visits for split time at 1-km increments, with 10-km time-to-completion shown as inset. * denotes slower than at 2-10 km (P < 0.05); # denotes faster than 1-9 km (P < 0.05) within the trials. Lower panel: Comparison of the two visits for heart rate at 1-km increments. Values are means ± SEM.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the volunteers who were willing to give honest efforts for six individual time-trials. We would also like to thank Dr. Samuel Cheuvront for guidance on the ZOI statistical analysis and the undergraduate research assistants Sabrina Raqueno-Angel, Jon Ivankovic, Chaucie Edwards, Sofia Andrews, Keeley DeBar, and Marisa Polonsky.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interests, financial or otherwise that would be affected by the outcome of this publication. This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant HL115027, the Eugene and Clarissa Evonuk Memorial Graduate Fellowship, and an ACSM Northwest Student Research Award. The authors declare that the results are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the ACSM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Romero SA, McCord JL, Ely MR, Sieck DC, Buck TM, Luttrell MJ, et al. Mast cell degranulation and de novo histamine formation contribute to sustained postexercise vasodilation in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2016;122(3):603–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayada K, Tsuchiya M, Yoneda H, Yamaguchi K, Kumamoto H, Sasaki K, et al. Induction of the histamine-forming enzyme histidine decarboxylase in skeletal muscles by prolonged muscular work: histological demonstration and mediation by cytokines. Biol Pharm Bull. 2017. August 1;40(8):1326–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metcalfe DD, Baram D, Mekori YA. Mast cells. Physiol Rev. 1997;77(4):1033–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schayer R Evidence that induced histamine is an intrinsic regulator of the microcirculatory system. Am J Physiol. 1962. January;202(1):66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsoy Nizamutdinova I, Maejima D, Nagai T, Meininger CJ, Gashev AA. Histamine as an endothelium-derived relaxing factor in aged mesenteric lymphatic vessels. Lymphat Res Biol. 2017;15(2):136–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong HJ, Moon PD, Kim SJ, Seo JU, Kang TH, Kim JJ, et al. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 regulates human histidine decarboxylase expression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009. April 7;66(7):1309–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Histamine Schayer R. and hyperæmia of muscular exercise. Nature. 1964. January 11;201(4915):195–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savany A, Croneberger L. Properties of histidine decarboxylase from rat gastric mucosa. Eur J Biochem. 1982;123(3):593–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endo Y, Tabata T, Kuroda H, Tadano T, Matsushima K, Watanabe M. Induction of histidine decarboxylase in skeletal muscle in mice by electrical stimulation, prolonged walking and interleukin-1. J Physiol. 1998;509(2):587–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoneda H, Niijima-Yaoita F, Tsuchiya M, Kumamoto H, Watanbe M, Ohtsu H, et al. Roles played by histamine in strenuous or prolonged masseter muscle activity in mice. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40(12):848–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niijima-Yaoita F, Tsuchiya M, Ohtsu H, Yanai K, Sugawara S, Endo Y, et al. Roles of histamine in exercise-induced fatigue: favouring endurance and protecting against exhaustion. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35(1):91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farzin D, Asghari L, Nowrouzi M. Rodent antinociception following acute treatment with different histamine receptor agonists and antagonists. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;72(3):751–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montgomery L, Deuster P. Acute antihistamine ingestion does not affect muscle strength and endurance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23(9):1016–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montgomery L, Deuster P. Ingestion of an antihistamine does not affect exercise performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24(3):383–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterlin MF, Keyser RE, Andres FF, Sherman G. Nonprescription chlorpheniramine maleate and submaximal exercise responses. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(7):827–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCord JL, Halliwill JR. H1 and H2 receptors mediate postexercise hyperemia in sedentary and endurance exercise-trained men and women. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101(6):1693–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Majno G, Palade G, Schoefl G. Studies on inflammation II. The site of action of histamine and serotonin along the vascular tree: a topographic study. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 11, no 3 607–626. 1961;11(3):607–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Currell K, Jeukendrup AE. Validity, reliability and sensitivity of measures of sporting performance. Sport Med. 2008;38(4):297–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer G, Dennis S, Noakes T, Hawley J. Assessment of the reproducibility of performance testing on an air-braked cycle ergometer. Int J Sports Med [Internet]. 1996. May 9 [cited 2016 Jul 14];17(04):293–8. Available from: http://www.thieme-connect.de/DOI/DOI?10.1055/s-2007-972849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell T, Stoltz M, Weir S. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and tolerance of single-and multiple-dose fexofenadine hydrochloride in healthy male volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998. December;64(6):612–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garg DC, Eshelman FN, Weidler DJ. Pharmacokinetics of ranitidine following oral administration with ascending doses and with multiple fixed-doses. J Clin Pharmacol. 1985;25(6):437–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCord JL, Beasley JM, Halliwill JR. H2-receptor-mediated vasodilation contributes to postexercise hypotension. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100(1):67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romero SA, Hocker AD, Mangum JE, Luttrell MJ, Turnbull DW, Struck AJ, et al. Evidence of a broad histamine footprint on the human exercise transcriptome. J Physiol. 2016. April;594(17):5009–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ely MR, Romero SA, Sieck DC, Mangum JE, Luttrell MJ, Halliwill JR. A single dose of histamine-receptor antagonists prior to downhill running alters markers of muscle damage and delayed onset muscle soreness. J Appl Physiol. 2016;122(3):631–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hopkins WG, Hawley JA, Burke LM. Design and analysis of research on sport performance enhancement. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999. March;31(3):472–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shephard RJ. Exercise and training in women, part II: influence of menstrual cycle and pregnancy. Can J Appl Physiol. 2000;25(1):35–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giacomoni M, Bernard T, Gavarry O, Altare S, Falgairette G. Influence of the menstrual cycle phase and menstrual symptoms on maximal anaerobic performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000. February;32(2):486–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganio MS, Klau JF, Casa DJ, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM. Effect of caffeine on sport-specific endurance performance: a systematic review. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(1):315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeukendrup AE, Martin J. Improving cycling performance. Sport Med. 2001;31(7):559–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nienartowicz A, Sobaniec-Łotowska ME, Jarocka-Cyrta E, Lemancewicz D. Mast cells in neoangiogenesis. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12(3):RA53–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noli C, Miolo A. The mast cell in wound healing. Vet Dermatol. 2001. December 1;12(6):303–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson AR, Erdos EG. Release of histamine from mast cells by vasoactive peptides. Exp Biol Med. 1973. April 1;142(4):1252–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serhan CN, Ward PA, Gilroy DW, Ayoub SS. Fundamentals of Inflammation. Serhan, Charles N ward Peter Gilroy DW, editor. Cambridge University Press; 2010. 65–85 p. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halliwill JR, Buck TM, Lacewell AN, Romero SA. Postexercise hypotension and sustained postexercise vasodilatation: what happens after we exercise? Exp Physiol. 2013. January;98(1):7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pellinger TK, Simmons GH, MacLean DA, Halliwill JR. Local histamine H1- and H2-receptor blockade reduces postexercise skeletal muscle interstitial glucose concentrations in humans. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010;35(5):617–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pellinger TK, Dumke BR, Halliwill JR. Effect of H1- and H2-histamine receptor blockade on postexercise insulin sensitivity. Physiol Rep. 2013;1(2):e00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emhoff C-AW, Barrett-O’Keefe Z, Padgett RC, Hawn JA, Halliwill JR. Histamine-receptor blockade reduces blood flow but not muscle glucose uptake during postexercise recovery in humans. Exp Physiol. 2011;96(7):664–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alaranta A, Alaranta H, Vaara MH, Alha P, Palmu P, Helenius I. Allergic rhinitis and pharmacological management in elite athletes. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2005;37(5):707–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alaranta A, Alaranta H, Heliövaara M, Airaksinen M, Helenius I. Ample use of physician-prescribed medications in Finnish elite athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2006. Nov;27(11):919–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montgomery L, Deuster P. Effects of antihistamine medications on exercise performance. Sport Med. 1993;15(3):179–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content Table 1. Familiarization Trials

Supplemental Digital Content Figure 1. Familiarization time-trials. Upper panel: Comparison of the two visits for split time at 1-km increments, with 10-km time-to-completion shown as inset. * denotes slower than at 2-10 km (P < 0.05); # denotes faster than 1-9 km (P < 0.05) within the trials. Lower panel: Comparison of the two visits for heart rate at 1-km increments. Values are means ± SEM.