Abstract

Background:

Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) is known as a quantitative biomarker of prenatal brain maturation. Fast macromolecular proton fraction (MPF) mapping is an emerging method for quantitative assessment of myelination that was recently adapted to fetal MRI.

Purpose:

To compare the capability of ADC and MPF to quantify the normal fetal brain development.

Study Type:

Prospective.

Population:

42 human fetuses in utero (gestational age (GA) = 27.7 ± 6.0, range 20–38 weeks).

Field Strength/Sequence:

1.5T; diffusion-weighted single-shot echo-planar spin-echo with five b-values for ADC mapping; spoiled multi-shot echo-planar gradient-echo with T1, proton density, and magnetization transfer contrast weightings for single-point MPF mapping.

Assessment:

Two operators measured ADC and MPF in the medulla, pons, cerebellum, thalamus, and frontal, occipital, and temporal cerebral white matter (WM).

Statistical Tests:

Mixed repeated-measures ANOVA with the factors of pregnancy trimester and brain structure; Pearson correlation coefficient (r); Hotelling-Williams test to compare strengths of correlations.

Results:

From 2nd to 3rd trimester, ADC significantly decreased in the thalamus and cerebellum (P<0.005). MPF significantly increased in the medulla, pons, thalamus, and cerebellum (P<0.005). Cerebral WM had significantly higher ADC and lower MPF compared to the medulla and pons in both trimesters. MPF (r range 0.83− 0.89, P<0.001) and ADC (r range −0.43 −0.75, P≤0.004) significantly correlated with GA and each other (r range −0.32 −0.60, P≤0.04) in the medulla, pons, thalamus, and cerebellum. No significant correlations and distinctions between regions and trimesters were observed for cerebral WM (P range 0.1–0.75). Correlations with GA were significantly stronger for MPF compared to ADC in the medulla, pons, and cerebellum (Hotelling-Williams test P<0.003) and similar in the thalamus. Structure-averaged MPF and ADC values strongly correlated (r=0.95, P<0.001).

Data Conclusion:

MPF and ADC demonstrated qualitatively similar but quantitatively different spatiotemporal patterns. MPF appeared more sensitive to changes in the brain structures with prenatal onset of myelination.

Keywords: Fetal MRI, brain maturation, myelin, apparent diffusion coefficient, macromolecular proton fraction

INTRODUCTION

MRI techniques for quantitative assessment of the fetal brain tissue maturation may facilitate a new approach in early diagnosis of various prenatal brain diseases and injuries and provide fundamental knowledge about mechanisms of pre- and postnatal neurodevelopment. Among these techniques, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) has attracted significant interest over the past decade due to its high sensitivity to the fetal brain tissue changes during pregnancy, broad availability, and rapid data acquisition that is critical for fetal MRI examinations.1–17 Numerous studies demonstrated significant correlations of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) with gestational age (GA) in various brain anatomical structures1−8 and sensitivity of ADC to certain fetal pathological conditions including ischemia,9,10 intrauterine growth restriction,11,12 ventriculomegaly,13,14 Chiari malformation,15 and cytomegalovirus infection.16,17

A newer quantitative MRI method, fast macromolecular proton fraction (MPF) mapping18,19 has been recently adapted to the fetal brain applications.20,21 MPF has been histologically validated as a myelin biomarker in animal models22–25 and has shown capability to quantify myelin damage in clinical studies of multiple sclerosis26,27 and mild traumatic brain injury.28 In the recent normal fetal20 and pediatric29 brain studies, MPF maps demonstrated close quantitative agreement with spatiotemporal trajectories of myelin development. MPF mapping also showed a promise as a complementary technique for evaluation of fetal brain tumors.21 A practically useful feature of the fast MPF mapping method18,19 is the feasibility of implementation on clinical MRI scanners with acceptable scan time.20,21,29

While both DWI and fast MPF mapping reflect tissue changes in the course of brain maturation, they are driven by different biophysical mechanisms. ADC describes mobility of water molecules and is affected by the factors restricting molecular motion, including primarily the amount of cell membranes in the tissue volume and concentration of biological macromolecules. MPF is a measure of a pool of protons attached to macromolecules, which exchange magnetization with water protons and are characterized by the solid-like magnetization dynamics.18 Myelin is the dominant source of the observed MPF in brain tissues.22–24 As such, it is unknown a priory whether both techniques could provide similar or different quantitative information about maturational changes in the brain. The objective of this study was to compare the capability of DWI and fast MPF mapping to quantify the fetal brain development in the normal population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

This prospective cross-sectional study was carried out in a single institution and approved by the local Ethical Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study population included 55 pregnant women referred for fetal MRI for clinical indications. DWI and MPF mapping sequences were executed as an addition to a clinical MRI protocol with an extra scan time of 5–7 min. No sedation was administered. Patients were recruited between December 2015 and August 2018. Gestational age (GA) was determined from the last menstrual period and confirmed by ultrasonography performed within one week prior to MRI. All MRI examinations were reviewed by a pediatric radiologist with sixteen-year experience in fetal MRI (A.M.K.). The fetuses with normal brain MRI or minor abnormalities, such as mild ventriculomegaly or mega cisterna magna, were included in this study. Thirteen cases were excluded. Among them, five had major abnormal findings including two cases of holoprosencephaly, one case of Dandy-Walker malformation, one fetal brain tumor, and one intracranial hemorrhage, and eight had unsuccessful or incomplete quantitative MRI examinations. The latter group included two cases with motion-corrupted DWI, five cases with unusable MPF maps, and one case where both DWI and MPF mapping were unsuccessful due to fetal motion.

MRI Acquisition

Images were acquired on a 1.5 T whole-body scanner (Achieva; Philips Medical Systems, Best, Netherlands) with an eight-channel body coil and unmodified manufacturer’s pulse sequences in the axial plane of the fetal brain. For ADC mapping, a 2D single-shot spin-echo diffusion-weighted echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence was used with the following parameters: TR/TE = 2940/64 ms; three orthogonal diffusion directions; five b-values of 0, 125, 251, 376, and 501 s/mm2; FOV 29 × 29 cm2; matrix 144 × 123 (interpolated to 240 × 240); in-plane resolution 2.01 × 2.36 mm2 (interpolated to 1.21 × 1.21 mm2); 12 slices with thickness of 5 mm and gap of 0.4 mm; two signal averages; and scan time of 79 s. The five-point DWI protocol was adapted from the earlier adult brain study30 with a two-fold reduction of the b-values in view of the fact that ADC values in the fetal brain are two-to-three-fold larger as compared to the adult brain.1–17

An MPF mapping protocol was implemented as described previously20,21 based on a 3D spoiled fast field-echo (FFE) sequence and included the following scans: MT-weighted with TR = 32 ms, flip angle (FA) = 8° and an off-resonance saturation pulse; reference with the same parameters and without the saturation pulse; T1-weighted with TR = 20 ms and FA = 20°; and proton-density (PD)-weighted with TR = 20 ms and FA = 4°. All source images for MPF mapping were acquired with multi-shot EPI readout (acceleration factor 9); TE = 6.3 ms; 3D FOV 25 × 25 × 6 cm3; matrix 168 × 167 × 12 (interpolated to 320 × 320 × 24); voxel size 1.49 × 1.50 × 5.0 mm3 (interpolated to 0.78 × 0.78 × 2.50 mm3); and two signal averages. The scan time was 19 s for the MT-weighted and reference sequences and 12 s for the T1- and PD-weighted sequences. The block of MPF mapping sequences with the total duration about 1 min was repeated from two to four times to minimize motion problems. After exclusion of motion-corrupted datasets, images were averaged during post-processing as detailed earlier.20

Image Processing and Analysis

ADC maps were automatically reconstructed by the scanner manufacturer’s software computing linear regression over the DWI signal logarithms based on the mono-exponential model. MPF maps were reconstructed using custom C-language software based on the single-point MPF fitting algorithm18,19 with the values of non-adjustable parameters detailed elsewhere.20

Two reviewers (a radiologist with sixteen-year experience (A.M.K.) and an MRI technologist with five-year experience (I.Y.P.) blinded to the gestational age independently analyzed ADC and MPF maps using MRIcro software31 (http://people.cas.sc.edu/rorden/mricro/mricro.html). Circular regions-of-interest (ROIs) were placed in the following anatomic structures: medulla, pons, cerebellum, thalamus, and frontal, temporal, and occipital WM. ADC and MPF maps were analyzed simultaneously, and the reviewers were instructed to keep anatomic locations of the ROIs in the two image types as similar as possible. The ROI area ranged from 7.3 to 22.6 mm2 depending on the fetal brain size. Examples of ROI positioning are displayed in Fig. 1.

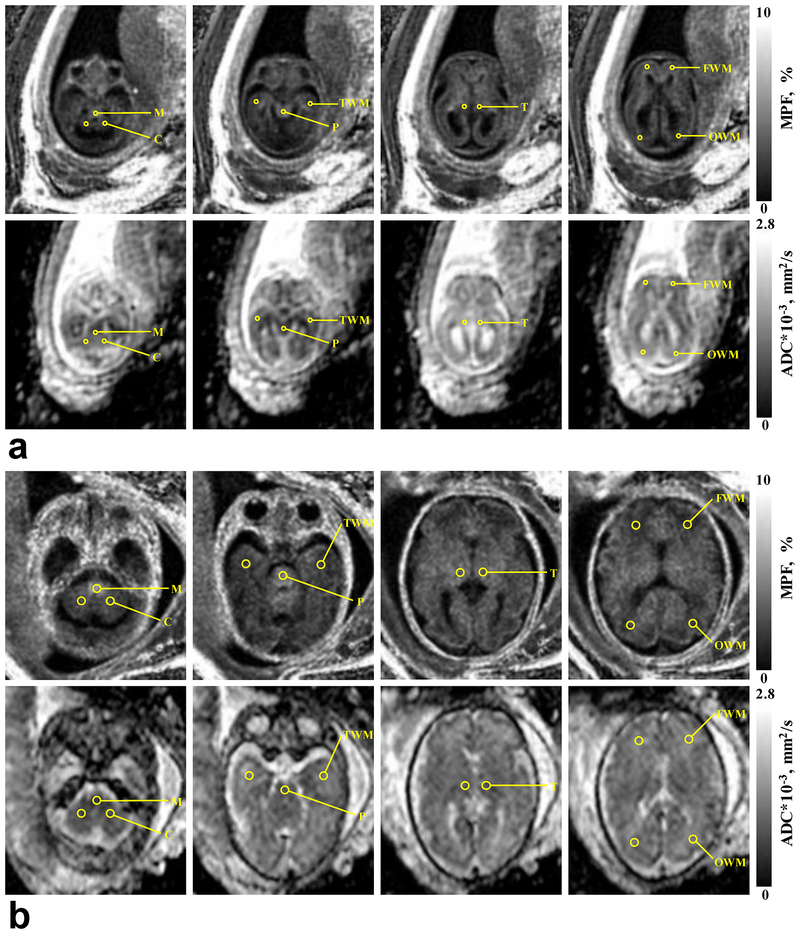

FIGURE 1:

Representative brain MPF and ADC maps obtained from the fetuses with GA of 20 (a) and 35 (b) weeks with the scheme of ROI placement. MPF maps (top rows) are presented with the grayscale range 0–10%. ADC maps (bottom rows) are presented with the grayscale range 0–2800×10−6 mm2/s. ROI labels correspond to the medulla (M), cerebellum (C), pons (P), temporal WM (TWM), thalamus (T), frontal WM (FWM), and occipital WM (OWM).

Statistical Analysis

Normality of data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. No significant deviations from the normal distribution were detected, and parametric analyses were used thereafter. Inter-observer agreement in ROI measurements was assessed by the within-subject coefficient of variation (CV) and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for each anatomic region. ICC estimates and their 95% confidence intervals were obtained using an average-measures absolute-agreement two-way mixed-effects model.32 Paired t-tests were used to detect the bias between observers. To compare ADC and MPF values between brain structures and pregnancy trimesters (defined as GA intervals of 20–26.5 and 27–38 weeks for the 2nd and 3rd trimester, respectively; 21 fetus in each group), mixed repeated-measures ANOVA model was used with the within-subject factor of the structure, between-subject factor of the trimester, and their interaction term. Greenhouse-Geisser correction for non-sphericity was applied to the degrees of freedom. Pairwise differences were assessed by the Tukey honest significant difference (HSD) post-hoc tests. Associations between ADC, MPF, and GA were tested using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r). Absolute values of correlation coefficients for correlations with GA were compared between ADC and MPF in each anatomic structure using the Hotelling-Williams test. Two-tailed tests were used in all analyses. P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were carried out in Statistica software (StatSoft Inc, Tulsa, OK, USA) except for the ICC and CV calculations, which were performed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

After exclusion of cases with major brain abnormalities and unsuccessful quantitative MRI examinations, the sample for subsequent data analysis included 42 fetuses with mean GA ± SD = 27.7 ± 6.0 weeks (range 20–38 weeks).Example ADC and MPF maps with superimposed ROIs are presented in Fig. 1. Table 1 summarizes statistics of inter-observer agreement for anatomic regions. By visual inspection, parametric maps (Fig. 1) exhibited mostly coincident areas of reduced ADC and elevated MPF (such as the brainstem structures) or vice versa (mainly in cerebral WM). There was excellent agreement (ICC > 0.8) for all ADC measurements and for MPF in all structures except for frontal, temporal, and occipital WM (ICC in a range 0.7–0.8). The later observation can be addressed to a low inherent variability of MPF in cerebral WM as detailed below. Inter-observer variability was also reasonable for the manual ROI measurements (within-subject CV in a range 4–9%). There was no significant bias between observers in any structure (P values ranged between 0.07 and 0.84).

Table 1.

Inter-observer agreement in ADC and MPF measurements in the fetal brain anatomic structures.

| Structure | ADC | MPF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV (95% CI), % | ICC (95% CI) | CV (95% CI), % | ICC (95% CI) | |

| Medulla | 8.8 (5.2, 11.3) | 0.84 (0.70, 0.91) | 5.4 (3.8, 6.6) | 0.96 (0.92, 0.98) |

| Pons | 5.3 (3.5, 6.6) | 0.96 (0.92, 0.98) | 6.2 (5.0, 7.3) | 0.90 (0.81, 0.94) |

| Thalamus | 4.4 (2.7, 5.6) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 7.9 (5.1, 10.0) | 0.88 (0.78, 0.94) |

| Cerebellum | 5.5 (3.0, 7.2) | 0.94 (0.90, 0.97) | 6.6 (5.2, 7.8) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.98) |

| Frontal WM | 4.7 (2.0, 6.3) | 0.91 (0.84, 0.95) | 6.3 (4.3, 7.8) | 0.78 (0.59, 0.88) |

| Temporal WM | 4.4 (3.3, 5.3) | 0.93 (0.87, 0.96) | 5.0 (4.1, 5.8) | 0.71 (0.47, 0.85) |

| Occipital WM | 3.9 (3.0, 4.7) | 0.95 (0.91, 0.97) | 6.6 (5.2, 7.8) | 0.71 (0.46, 0.84) |

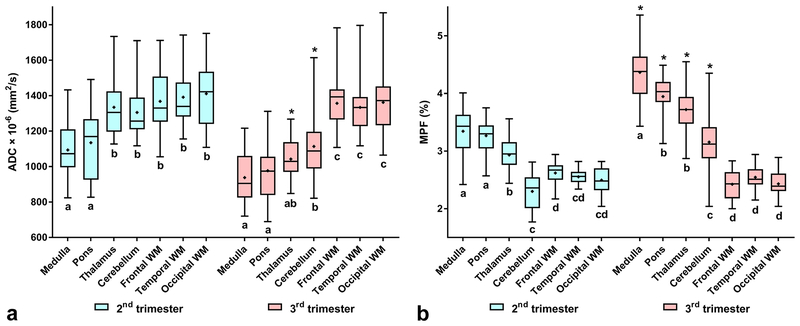

Repeated-measures ANOVA identified the highly significant effects of the brain structure, pregnancy trimester, and their interaction on both ADC and MPF (Table 2). Mean values of ADC and MPF across the trimesters and structures and the results of their pairwise comparisons are summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 2. ADC significantly decreased in the thalamus and cerebellum and did not change in cerebral WM from the 2nd to 3rd trimester. An ADC decrease was also observed for the medulla and pons (Fig. 2), but it did not reach significance after correction for multiple comparisons. MPF significantly increased in the medulla, pons, thalamus, and cerebellum and showed no differences in cerebral WM between the trimesters (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Summary of mixed repeated-measures ANOVA for ADC and MPF measurements across the fetal brain structures and pregnancy trimesters.

| Parameter | Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trimester | Structure | Trimester*Structure | |

| ADC |

F(1, 40) = 11.14 P = 0.0018 |

F(3.93, 157.25) = 74.18 P < 0.0001 |

F(3.93, 157.25) = 7.73 P < 0.0001 |

| MPF |

F(1, 40) = 41.14 P < 0.0001 |

F(3.42, 136.97) = 216.0 P < 0.0001 |

F(3.42, 136.97) = 41.96 P < 0.0001 |

Table 3.

Mean ADC and MPF values in the anatomic structures of the fetal brain for the 2nd and 3rd pregnancy trimesters.

| Structure | ADC × 10−6 (mm2/s) | MPF (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd trimester (n = 21) |

3rd trimester (n = 21) |

2nd trimester (n = 21) |

3rd trimester (n = 21) |

|

| Medulla | 1094 ± 170 | 938 ± 135 | 3.34 ± 0.42 | 4.36 ± 0.49a |

| Pons | 1134 ± 193 | 977 ± 177 | 3.27 ± 0.28 | 3.94 ± 0.38ab |

| Thalamus | 1335 ± 162bc | 1042 ± 115a | 2.93 ± 0.29bc | 3.72 ± 0.37ab |

| Cerebellum | 1305 ± 136bc | 1113 ± 195abc | 2.30 ± 0.33bcd | 3.15 ± 0.51abcd |

| Frontal WM | 1368 ± 178bc | 1357 ± 149bcde | 2.61 ± 0.18bcde | 2.42 ± 0.25bcde |

| Temporal WM | 1391 ± 169bc | 1334 ± 148bcde | 2.55 ± 0.12bcd | 2.54 ± 0.21bcde |

| Occipital WM | 1411 ± 197bc | 1363 ± 166bcde | 2.49 ± 0.21bcd | 2.43 ± 0.21bcde |

ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient; MPF: macromolecular proton fraction; WM: white matter.

Note. –Data are mean ± SD. Mean values were compared between trimesters and structures using repeated-measures ANOVA. P values are for post-hoc pairwise comparisons using the Tukey HSD test.

Significantly different from the 2nd trimester (P < .005).

Significantly different from the medulla within the same trimester (P < .005).

Significantly different from the pons within the same trimester (P < .005).

Significantly different from the thalamus within the same trimester (P < .005).

Significantly different from the cerebellum within the same trimester (P < .05).

FIGURE 2:

Box-whisker plots representing the distributions of ADC (a) and MPF (b) measurements across the fetal brain anatomical structures and pregnancy trimesters. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the 2nd and 3rd trimesters for the same structure. Shared letters indicate no significant differences between structures within the same trimester.

Both ADC and MPF showed an apparent pattern of divergence between brain structures in the 3rd trimester compared to the 2nd one (Table 3, Fig. 2). ADC in 2nd trimester were significantly different between the two groups, one of which included brainstem structures (medulla and pons) with lower values and another contained the thalamus, cerebellum, and cerebral WM with higher values. No distinctions were found within groups. In the 3rd trimester, ADC in cerebral WM was significantly higher than that in the medulla, pons, thalamus, and cerebellum. ADC in the thalamus appeared close to that in the medulla and pons and significantly smaller compared to the cerebellum, while for the last structure the significant differences from the medulla and pons were preserved. Within the similar pattern, MPF demonstrated more pairwise distinctions, which appeared statistically significant. In the 2nd trimester, MPF in the cerebral WM and cerebellum were significantly lower than those in the medulla and pons, thus showing a similar to ADC trend with opposite direction. However, MPF in the thalamus was intermediate between the above groups, being significantly different from both. In the 3rd trimester, MPF in cerebral WM was significantly lower than MPF in any other structure, MPF in the cerebellum was significantly lower compared to the thalamus, medulla, and pons, and MPF in the thalamus was significantly lower than MPF in the medulla but similar to that in the pons. Notably, the difference in MPF between the medulla and pons became significant in the 3rd trimester with the largest value in the medulla. Neither parameter showed significant distinctions between frontal, temporal, and occipital WM in both trimesters.

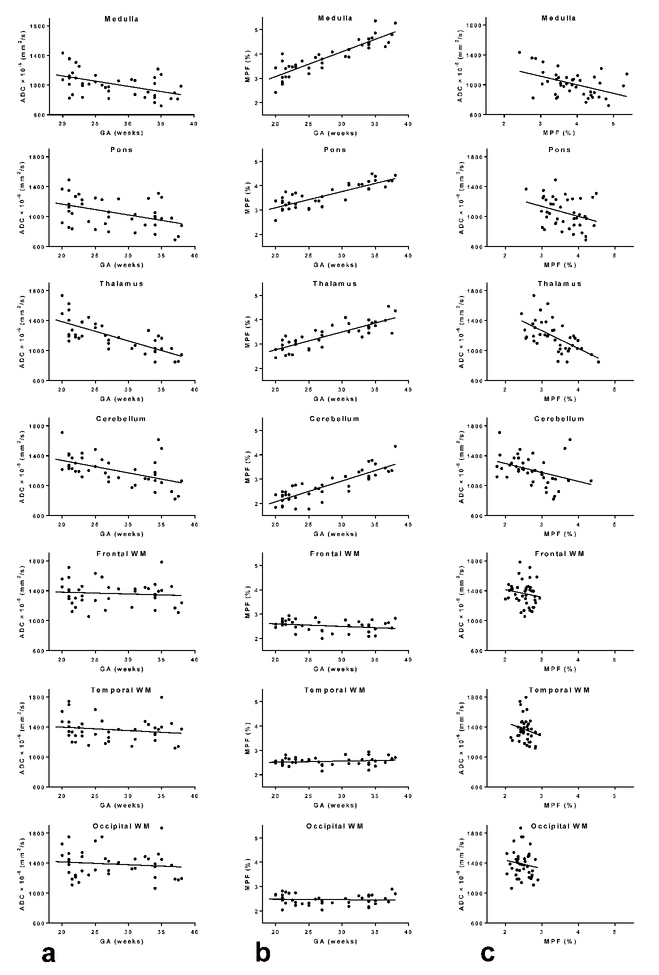

Correlations between ADC, MPF, and GA in the anatomic structures are summarized in Table 4 and Figs. 3. ADC demonstrated significant negative correlations with GA in the medulla, pons, thalamus, and cerebellum. The correlation was strong in the thalamus, and other correlations were of moderate strengths. MPF very strongly positively correlated with GA in the same structures. Comparisons between the absolute values of correlation coefficients demonstrated that correlations for MPF were significantly stronger in the medulla, pons, and cerebellum, while there was no significant difference for the thalamus. ADC and MPF showed weak-to-moderate significant negative correlations in the medulla, pons, thalamus, and cerebellum with the strongest association in the thalamus. No significant correlations were found for the cerebral WM regions.

Table 4.

Correlations between ADC, MPF, and GA in the anatomic structures of the fetal brain.

| Structure | Bivariate correlation, r (P) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ADC-GA | MPF-GA | ADC-MPF | |

| Medulla | −0.49 (0.001)a | 0.89 (<0.001)ab | −0.46 (0.002)a |

| Pons | −0.43 (0.004)a | 0.83 (<0.001)ab | −0.32 (0.04)a |

| Thalamus | −0.75 (<0.001)a | 0.84 (<0.001)a | −0.60 (<0.001)a |

| Cerebellum | −0.52 (<0.001)a | 0.84 (<0.001)ab | −0.37 (0.015)a |

| Frontal WM | −0.09 (0.58) | −0.26 (0.10) | −0.15 (0.34) |

| Temporal WM | −0.17 (0.27) | 0.17 (0.29) | −0.20 (0.21) |

| Occipital WM | −0.12 (0.45) | −0.05 (0.75) | −0.13 (0.42) |

Significant correlations.

Significant differences between ADC and MPF in their correlations with GA according to the Hotelling-Williams test for absolute values of r (P < 0.003).

FIGURE 3:

Scatterplots of correlations between ADC and GA (a), between MPF and GA (b), and between ADC and MPF (c) in the fetal brain anatomic structures. The lines depict linear regression plots.

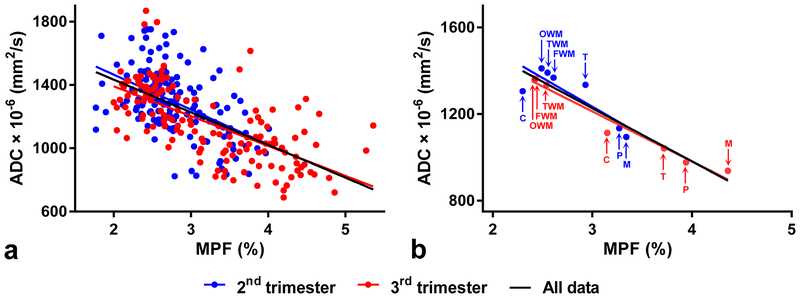

Global correlation between ADC and MPF assessed on the entire dataset (Fig. 4a) was strong-to-moderate (r=−0.63, P<0.001, n=294). Correlation taken on the subset of data corresponding to the 3rd trimester (r=−0.67, P<0.001, n=147) was stronger than correlation for the 2nd trimester (r=−0.49, P<0.001, n=147). The same analysis for the structure-averaged data (Fig. 4b) resulted in very strong correlations between ADC and MPF for both trimesters taken together (r=−0.95, P<0.001, n=14) and separately with substantially stronger correlation within the 3rd trimester (r=−0.98, P<0.001, n=7) as compared to the 2nd one (r=−0.85, P=0.017, n=7).

FIGURE 4:

Scatterplots of correlations between ADC and MPF in the fetal brain assessed for the global dataset (a) and structure-averaged data (b). The lines depict linear regression plots. Blue and red colors indicate data for the 2nd and 3rd trimester fetuses, respectively. The black lines correspond to regression over the data for both trimesters. Structure labels in panel (b) correspond to the medulla (M), pons (P), thalamus (T), cerebellum (C), temporal WM (TWM), frontal WM (FWM), and occipital WM (OWM).

DISCUSSION

The key finding of this study is a general qualitative agreement between the patterns of the fetal brain maturation identified by MPF and ADC. Both variables significantly correlated with GA in the brain structures with the known prenatal myelination onset including the brainstem (pons and medulla), cerebellum, and thalamus.33–36 At the same time, no significant correlations were found in the frontal, occipital, and temporal cerebral WM regions, which appear unmyelinated in the fetal brain and develop myelin over several postnatal years.33–35 Furthermore, structure-averaged ADC and MPF values demonstrated very strong correlation, especially in the 3rd trimester, the period when the distinctions between anatomic regions with and without ongoing myelination become apparent.33–36 MPF has been recently validated in a number of animal studies as a biomarker of myelin and showed very strong correlations with histologically determined myelin content.22–24 Close agreement between MPF and myelin density was established in the normal adult rat brain tissues22 and certain disease models, such as cuprizone-induced demyelination23 and ischemic stroke.24 Although animal model data about maturation-dependent MPF changes are limited to the postnatal brain development,25,37 these studies also suggest that myelination is the main determinant of MPF changes. Particularly, MPF maps demonstrated dramatic distinctions between temporal trajectories of myelination in the normal canine brain and a genetic dysmyelination model (shaking pup).37 A recent study25 showed a systematic increase of MPF in the majority of white and gray matter anatomic structures of the murine brain from 4 to 12 weeks of age in agreement with histology. The latest studies of age-dependent MPF changes in fetuses20 and children29 also suggest close relationship between MPF and myelination in accordance with histologically established spatial-temporal patterns of myelin development.33–36 It is worth noting in this context that MPF in the fetal brain is very low as compared to the adult brain, being 4–6-fold smaller than MPF in adult WM and 2–3-fold smaller than MPF in adult gray matter.18–20,26–28 Taken together, our results and the literature data suggest that myelination provides the dominant driving force for both MPF and ADC spatiotemporal trajectories in the fetal brain.

Despite the common features in the patterns of changes displayed by ADC and MPF, clear distinctions between these parameters were also observed. MPF showed significantly stronger associations with GA as compared to ADC in the brainstem structures and cerebellum, while correlations between ADC and MPF in these structures were rather weak. In contrast, ADC strongly correlated with both MPF and GA in the thalamus. While the biophysical mechanisms underlying the ADC behavior during brain development are complex and poorly understood, these observations suggest that in addition to myelination, ADC is substantially affected by other factors, such as neuronal remodeling and pruning, axonal sprouting, and glial proliferation, as well as global changes in the tissue cellularity and water content. In general, the number of cells per gram in the brain is dramatically reduced during prenatal development38 in lieu of increased complexity of cellular morphology that includes, for example, the formation of mature neurons with extensive arborization and the transformation of radial glia into astroglia and neurons.39 As the above phenomena drive the density of plasma membranes and extracellular space volume in opposite directions, they may limit the size of correlations between ADC and GA or MPF. In the thalamus, which can be viewed as a mixed white and gray matter structure, myelination of axons35 and formation of thalamic nuclei involving neuronal differentiation and proliferation40 may produce a synergistic effect on restricted diffusion. It is also worth mentioning that no significant correlations between ADC and MPF across both white and gray matter anatomic structures were identified in the adult brain earlier.41 The concordance between ADC and MPF observed at the fetal stage of brain development should be viewed therefore as a transient feature, which disappears in the course of maturation and suggests that sensitivity of ADC to the myelin content decreases with an increased complexity of neural tissue cytoarchitecture.

This study has several limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional design, the inferences regarding longitudinal changes in the parameters of interest are indirect. Second, the reported ADC and MPF values were obtained in a single-center single-platform setting. Therefore, an instrumental bias in the measured parameters cannot be excluded. MPF measurements performed with a standard manufacturer’s MT-weighted sequence may suffer from a bias due to suboptimal parameters of the off-resonance saturation pulse.18 Particularly, an offset frequency in this sequence is set to 1.1 kHz,20 while the optimal range for fast MPF mapping is 4–7 kHz.18 On the other hand, the MPF values in the adult brain obtained with a similar 1.5T protocol20 appeared fairly consistent with earlier MPF measurements performed using the optimally designed technique at 3T.18,19,26–28 More research is needed to precisely assess accuracy of MPF measurements in clinical MRI settings using unmodified manufacturers’ sequences. It also should be noted in this context that the literature fetal brain ADC values1–17 vary widely depending on the imaging equipment and protocol. For example, mean ADC in fetal frontal WM were reported in a range from 1370 to 2170 ×10−6 mm2/s.6,11 Our data are in overall agreement with the literature and tend to be on the lower end of the published ADC ranges. Likewise, patterns of associations between ADC and GA observed in this study a generally in line with previous investigations,3–6,8 which repeatedly demonstrated significant negative correlations for the infratentorial structures and thalamus. It should be noted, however, that the observations for cerebral WM are more controversial, as some authors found significant negative correlations between ADC in certain cerebral WM regions and GA,2,5,8 while others did not find such correlations1,6,7 or reported non-monotonic3 or positive4 trends. Third, our interpretation of MPF changes strictly in terms of the myelin development does not take into account water content changes, which may confound MPF measurements.24 It is known that the water content in brain tissues decreases in the course of brain maturation.38 Based on the literature,38 a water content decrease in the human brainstem and cerebellum from midgestation to birth is about 5–7%. A possible effect of a reduced water content on MPF measurements can be estimated using the definition of MPF18 as MPF=100*[M]/([M]+[W]), where [M] and [W] are the molar concentrations of macromolecular and water protons, respectively. Assuming that the baseline MPF is 3% and water content decreases by 7%, a resulting increase in MPF caused by the water content change alone would be 0.2% in absolute scale that is about 7% of the baseline value. This estimate is substantially less than the observed MPF increase from the 2nd to 3rd pregnancy trimester in the structures with ongoing myelination (around 30% relative change based on the averaged data for the medulla, pons, and cerebellum). Accordingly, accounting for water content variations could not change the conclusions of this study, and interpretation of the MPF dynamics in the fetal brain in terms of myelination remains biologically plausible. Fourth, a common limitation of fetal quantitative MRI in vivo, relatively low spatial resolution caused by the need in fast scanning applies to this study. Similar to other reports, our data might be affected by the partial volume effect from surrounding tissues, such as germinal matrix and cerebrospinal fluid. Fifth, our quantitative imaging protocol might be somewhat suboptimal in the context of scan time and motion sensitivity. Particularly, acquisition of DWI datasets with intermediate b-values might be redundant in view of the optimal sampling conditions for the mono-exponential analysis,42 though extra b-values still could be beneficial considering the ADC heterogeneity in the fetal brain.43 Our approach to mitigate fetal motion problems in MPF mapping was rather simplistic and included repeated data acquisition followed by exclusion of corrupted or misregistered source images from processing.20 Application of dedicated post-processing registration and motion correction algorithms44 may improve the success rate of this technique and allow reducing the number of repeated acquisitions.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that MPF and ADC reveal qualitatively similar but quantitatively different spatiotemporal patterns of the fetal brain maturation. MPF appeared more sensitive to early changes in the brain structures with known prenatal onset of myelination. Both parameters can be measured in routine clinical settings and may provide complimentary information about normal and abnormal development of the fetal brain.

Acknowledgments:

The authors are grateful to Yi Wang, PhD (Philips Healthcare, USA) for providing information about the MRI manufacturer’s DWI reconstruction algorithm implementation.

Grant support: This study was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation within the State Assignment Project No. 18.2583.2017/4.6. Drs. Korostyshevskaya and Savelov received salary support from the Federal Agency of Scientific Organizations of the Russian Federation (Project No. 0333-2017-0003). MPF mapping reconstruction software was distributed under support of NIH grant R24NS104098–01A1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Righini A, Bianchini E, Parazzini C, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient determination in normal fetal brain: a prenatal MR imaging study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003;24:799–804. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bui T, Daire JL, Chalard F, et al. Microstructural development of human brain assessed in utero by diffusion tensor imaging. Pediatr Radiol 2006;36:1133–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider JF, Confort-Gouny S, Le Fur Y, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging in normal fetal brain maturation. Eur Radiol 2007;17:2422–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannie M, De Keyzer F, Meersschaert J, et al. A diffusion-weighted template for gestational age-related apparent diffusion coefficient values in the developing fetal brain. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007;30:318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider MM, Berman JI, Baumer FM, et al. Normative apparent diffusion coefficient values in the developing fetal brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009;30:1799–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyer AC, Gonçalves LF, Lee W, et al. Magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging: reproducibility of regional apparent diffusion coefficients for the normal fetal brain. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;41:190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sartor A, Arthurs O, Alberti C, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient measurements of the fetal brain during the third trimester of pregnancy: how reliable are they in clinical practice? Prenat Diagn 2014;34:357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han R, Huang L, Sun Z, et al. Assessment of apparent diffusion coefficient of normal fetal brain development from gestational age week 24 up to term age: a preliminary study. Fetal Diagn Ther 2015;37:102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldoli C, Righini A, Parazzini C, Scotti G, Triulzi F. Demonstration of acute ischemic lesions in the fetal brain by diffusion magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol 2002;52:243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guimiot F, Garel C, Fallet-Bianco C, et al. Contribution of diffusion-weighted imaging in the evaluation of diffuse white matter ischemic lesions in fetuses: correlations with fetopathologic findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:110–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arthurs OJ, Rega A, Guimiot F, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the fetal brain in intrauterine growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017;50:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kutuk MS, Sahin M, Gorkem SB, Doganay S, Ozturk A. Relationship between Doppler findings and fetal brain apparent diffusion coefficient in early-onset intra-uterine growth restriction. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018;31:3201–3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erdem G, Celik O, Hascalik S, Karakas HM, Alkan A, Firat AK. Diffusion-weighted imaging evaluation of subtle cerebral microstructural changes in intrauterine fetal hydrocephalus. Magn Reson Imaging 2007;25:1417–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaniv G, Katorza E, Bercovitz R, et al. Region-specific changes in brain diffusivity in fetal isolated mild ventriculomegaly. Eur Radiol 2016;26:840–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mignone Philpott C, Shannon P, Chitayat D, Ryan G, Raybaud CA, Blaser SI. Diffusion-weighted imaging of the cerebellum in the fetus with Chiari II malformation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013;34:1656–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yaniv G, Hoffmann C, Weisz B, et al. Region-specific reductions in brain apparent diffusion coefficient in cytomegalovirus-infected fetuses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;47:600–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotovich D, Guedalia JSB, Hoffmann C, Sze G, Eisenkraft A, Yaniv G. Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Value Changes and Clinical Correlation in 90 Cases of Cytomegalovirus-Infected Fetuses with Unremarkable Fetal MRI Results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017;38:1443–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yarnykh VL. Fast macromolecular proton fraction mapping from a single off-resonance magnetization transfer measurement. Magn Reson Med 2012;68:166–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yarnykh VL. Time-efficient, high-resolution, whole brain three-dimensional macromolecular proton fraction mapping. Magn Reson Med 2016;75:2100–2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yarnykh VL, Prihod’ko IY, Savelov AA, Korostyshevskaya AM. Quantitative assessment of normal fetal brain myelination using fast macromolecular proton fraction mapping. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39:1341–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korostyshevskaya AM, Savelov AA, Papusha LI, Druy AE, Yarnykh VL. Congenital medulloblastoma: Fetal and postnatal longitudinal observation with quantitative MRI. Clin Imaging 2018;52:172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Underhill HR, Rostomily RC, Mikheev AM, Yuan C, Yarnykh VL. Fast bound pool fraction imaging of the in vivo rat brain: Association with myelin content and validation in the C6 glioma model. Neuroimage 2011;54:2052–20 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khodanovich MY, Sorokina IV, Glazacheva VY, et al. Histological validation of fast macromolecular proton fraction mapping as a quantitative myelin imaging method in the cuprizone demyelination model. Sci Rep 2017;7:46686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khodanovich MY, Kisel AA, Akulov AE, et al. Quantitative assessment of demyelination in ischemic stroke in vivo using macromolecular proton fraction mapping. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018;38:919–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu J, Synowiec S, Lu L, et al. Microbiota influence the development of the brain and behaviors in C57BL/6J mice. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yarnykh VL, Bowen JD, Samsonov A, et al. Fast whole-brain three-dimensional macromolecular proton fraction mapping in multiple sclerosis. Radiology 2015;274(1):210–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yarnykh VL, Krutenkova EP, Aitmagambetova G, et al. Iron-insensitive quantitative assessment of subcortical gray matter demyelination in multiple sclerosis using the macromolecular proton fraction. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2018;39:618–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrie EC, Cross DJ, Yarnykh VL, et al. Neuroimaging, Behavioral, and Psychological Sequelae of Repetitive Combined Blast/Impact Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans. J Neurotrauma 2014;31(5):425–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yarnykh V, Knipenberg N, Tereshchenkova O. Quantitative assessment of pediatric brain myelination in a clinical setting using macromolecular proton fraction In: Proceedings of the 26th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Paris, France; 2018. (abstract 525). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamasaki F, Kurisu K, Satoh K, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient of human brain tumors at MR imaging. Radiology 2005;235:985–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rorden C, Brett M. Stereotaxic display of brain lesions. Behav Neurol 2000;12:191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods 1996;1:30–46. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yakovlev PI, Lecours AR. The myelogenetic cycles of regional maturation of the brain In: Minkowski A, ed. Regional development of the brain in early life. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1967:3–70. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinney HC, Brody BA, Kloman AS, Gilles FH. Sequence of central nervous system myelination in human infancy. II. Patterns of myelination in autopsied infants. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1988;47:217–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasegawa M, Houdou S, Mito T, Takashima S, Asanuma K, Ohno T. Development of myelination in the human fetal and infant cerebrum: a myelin basic protein immunohistochemical study. Brain Dev 1992;14:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka S, Mito T, Takashima S. Progress of myelination in the human fetal spinal nerve roots, spinal cord and brainstem with myelin basic protein immunohistochemistry. Early Hum Dev 1995;41:49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samsonov A, Alexander AL, Mossahebi P, Wu YC, Duncan ID, Field AS. Quantitative MR imaging of two-pool magnetization transfer model parameters in myelin mutant shaking pup. Neuroimage 2012;62:1390–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dobbing J, Sands J. Quantitative growth and development of human brain. Arch Dis Child 1973;48:757–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashwell KWS, Mai JK. Fetal development of the central nervous system In: Mai JK, Paxinos G, editors. The Human Nervous System, 3rd edition. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press; 2012. p 31–79. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mojsilović J, Zecević N. Early development of the human thalamus: Golgi and Nissl study. Early Hum Dev 1991;27:119–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Underhill HR, Yuan C, Yarnykh VL. Direct quantitative comparison between cross-relaxation imaging and diffusion tensor imaging of the human brain at 3.0 T. Neuroimage 2009;47:1568–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xing D, Papadakis NG, Huang CL, Lee VM, Carpenter TA, Hall LD. Optimised diffusion-weighting for measurement of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in human brain. Magn Reson Imaging 1997;15:771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Correia MM, Carpenter TA, Williams GB. Looking for the optimal DTI acquisition scheme given a maximum scan time: are more b-values a waste of time? Magn Reson Imaging 2009;27:163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang S, Xue H, Counsell S, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) of the brain in moving subjects: application to in-utero fetal and ex-utero studies. Magn Reson Med 2009;62:645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]