Abstract

Background:

Pathways of Enhanced Recovery in Liver Surgery (ERILS) decrease inpatient opioid use, however, there is little existing data regarding their effect on discharge prescriptions and post-discharge opioid intake.

Methods:

For consecutive patients undergoing liver resection from 2011–2018, clinicopathologic factors were compared between patients exposed to ERILS and traditional pathways. Multivariable analysis was used to determine factors predictive for traditional opioid use at the first postoperative follow-up. The ERILS protocol included opioid-sparing analgesia, goal-directed fluid therapy, early postoperative feeding, and early ambulation.

Results:

Of 244 cases, 147 ERILS patients were compared to 97 traditional pathway patients. ERILS patients were older (median 57 vs. 52 years, p=0.031) and more frequently had minimally invasive operations (37% vs. 16%, p<0.001), with fewer major complications (2% vs. 9%, p=0.011). ERILS patients were less likely to be discharged with a prescription for traditional opioids (26% vs. 79%, p<0.001) and less likely to require opioids at their first postoperative visit (19% vs. 61%, p<0.001) despite similarly low, patient-reported pain scores (median 2/10 both groups, p=0.500). On multivariable analysis, traditional recovery pathway were associated with traditional opioid use at first follow-up (OR 6.4, 95% CI 3.5–12.1; p<0.001).

Conclusions:

The implementation of an ERILS pathway with opioid-sparing techniques was associated with decreased postoperative discharge prescriptions for opioids and outpatient opioid use after oncologic liver surgery, while achieving the same level of pain control. For this and other populations at risk of persistent opioid use, enhanced recovery strategies can eliminate excess narcotic availability.

INTRODUCTION

The opioid epidemic continues to be a huge public health concern both in the United States and abroad. Opioids are the source of greater than 60% of deaths related to drug overdose, and the death rate from prescription opioid use has quadrupled in the last 20years.1 In addition, the economic burden of this epidemic costs the United States an estimated $78.5 billion annually.2 For surgeons, the perioperative period is a critical setting for opioid-prescribing, and thus, an area to target for intervention. Previous research has demonstrated that prescribing opioid medications to even opioid-naive patients in the perioperative period can lead to long-term use, with rates of new persistent opioid use as great as 6.5%.3, 4 Specific to the cancer population, recent literature has shown that 10–15% of previously opioid-naïve patients undergoing oncologic surgery become new persistent opioid users.5, 6

In recent years, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) efforts have improved perioperative outcomes after many types ofoperations.7–10 Specific to liver surgery, enhanced recovery efforts are reported to decrease overall complications and hospital duration of stay.11 One of the pillars of a successful ERAS program is opioid-sparing analgesia. ERAS protocols have been demonstrated to decrease rates of inpatient opioid use,12, 13 however, data on the ability of enhanced recovery programs to minimize opioid prescriptions at discharge and outpatient opioid use in hepatobiliary surgery is lacking. It is important to define strategies for elimination of excess opioids in patients undergoing hepatobiliary surgery given the continued high proportion of open approaches, the magnitude of resections, the potential alterations to drug metabolism accompanying liver resection, and the frequent need for subsequent adjuvant therapies.

The primary objective of this study was to compare postoperative pain control and postoperative outpatient opioid requirements for patients undergoing hepatectomy, mostly for malignancy, based on whether or not the patient was managed with an evidence-based Enhanced Recovery in Liver Surgery (ERILS) protocol or a traditional recovery pathway. The secondary aim was to compare discharge prescription practices after liver resection between patients managed on the ERILS pathway and patients managed on a traditional recovery pathway.

METHODS

Study Population and Data Collection

After approval by our Institutional Review Board, a prospectively-maintained surgical database was queried for consecutive patients intended for liver resection from October 2011 through January 2018 (n=387). Patients who underwent a simultaneous major multivisceral resection (most commonly a colon resection) were excluded to control for the potential confounding effects that a concomitant major operation could have on perioperative recovery, as were patients who were explored but determined to be oncologically unresectable. Baseline patient demographics including age, sex, body mass index ([BMI], kg/m2), and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification were obtained. Performance status was prospectively-collected using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) grading system.14 Perioperative details including operative approach, operative time, estimated blood loss, and duration of stay were collected.

Type of recovery pathway (Enhanced Recovery in Liver Surgery [ERILS] vs. traditional pathway) and use of a regional analgesia technique was noted. Techniques for regional analgesia included thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA) or transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block. Epidural catheters were placed between the 5th-10th thoracic interspinous levels and dosed according to current practices with hydromorphone 5–10mcg/kg and 3–10ml of 2% lidocaine (or 0.25% bupivacaine). Standard solutions for continuous infusion were hydromorphone 5mcg/ml and bupivacaine (0.075%). TAP blocks included both preoperative ultrasonographic-guided injection (by the anesthesiologist) and intraoperative injection (by the surgeon) of long-acting liposomal bupivacaine. Major hepatectomy was defined as involving three or more contiguous liver segments.15 Complications were recorded and graded using the Accordion Severity Grading System. Complications that were grade III or greater were defined as major.16 Time to first postoperative follow-up visit was measured from the date of operation. The few patients with time-to-first-follow-up ≥30 days were excluded prior to statistical analysis.

Opioid Use and Patient-Reported Outcomes

• Preoperative opioid use was defined as any patient reporting the use of any traditional oral opioid medication within 30 days of operation. In this study, the term ‘traditional opioid’ refers to the semi-synthetic oral opioids including formulations of hydrocodone, oxycodone, and hydromorphone (Table 1). Use of tramadol hydrochloride, a weak synthetic agonist of the mu-opioid receptor with lesser addictive potential, was not included under the ‘traditional opioid’ classification but was recorded separately and is reported throughout the Results section.17 In most cases, data on patient opioid use werecollected through real-time interview by a dedicated research team. If the patient was not assessed directly by the research team, these data were captured via electronic medical record review of templated notes designed specifically to record opioid intake. All discharge prescriptions were also reviewed. Patient-reported pain scores were recorded from the first postoperative visit documentation, where the worst pain the patient had experienced in the last 24-hours was documented on a 0–10 scale.

Table 1.

Classification and Terminology of Opioid Medications

| Opioids | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Opiate | Traditional Opioids | Opiate-like narcotic |

| Origin | Natural | Semi-Synthetic | Synthetic |

| Drug(s) | Morphine | Hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone | Tramadol |

Traditional Liver Surgery Pathway

Postoperative management using a traditional pathway consisted of pain control at the discretion of the care team, most typically via intravenous and oral opiates and traditional opioids on an as-needed basis. Similarly, prescriptions for these medications were provided universally at discharge but without standardization of drug or amount.

Enhanced Recovery in Liver Surgery Pathway

The ERILS protocol has been well-described in a previous publication by Day et al.18 To be classified as using the ERILS pathway, a patient’s perioperative care must have included at minimum: patient education, early oral feeding, goal-directed fluid therapy, multimodal analgesia, and early ambulation. When assessing the ERILS implementation phase, prior to the streamlined use of order sets that included all elements of the pathway, detailed chart review was performed to determine if a patient was ERILS-element compliant. The ERILS analgesia component incorporated the use of a preoperative, multimodal oral regimen consisting of: a non-narcotic neuromodulator (pregabalin), an anti-inflammatory nonsteroidal drug [NSAIDs (i.e. ibuprofen) or COX-2 inhibitors (i.e. celecoxib)], and tramadol, as well as regional anesthetic blocks.19 Postoperatively, patients were managed with similar scheduled multimodal adjuncts and traditional opioid administration only on an ‘as needed’ basis, for pain uncontrolled by opioid alternatives and/or tramadol.

During the postoperative hospitalization, ERILS patients returned to a multimodality oral regimen that included tramadol. At discharge, depending on the inpatient response to these agents and/or issues of outpatient prescription cost, the ERILS pain management strategy consisted of scheduled COX-2 inhibitors or over-the-counter ibuprofen and oral acetaminophen or a low-volume (< 30 pills) tramadol prescription for breakthrough pain. Discharge prescriptions for traditional opioids were reserved for patients requiring consistent semi-synthetic opioid administration within the last 24 hours of admission.

Patient education and engagement were also an integral part of the ERILS management plan. As such, starting in August 2013, in conjunction with the phased ERILS implementation, all patients were contacted within 72-hours of hospital discharge and asked a standardized list of questions regarding their recovery. This interview included pain control needs and use of opioids and non-narcotic adjuncts.20

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as numerical figures and percentages and were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]) and were compared using Mann-Whitney U tests. All p values were two-sided and p<0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Clinical factors with p<0.1 on univariate analyses were included in the multivariable analysis which was performed using binary logistic regression and a backwards stepwise variable elimination method. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro software (version 12; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Study Population

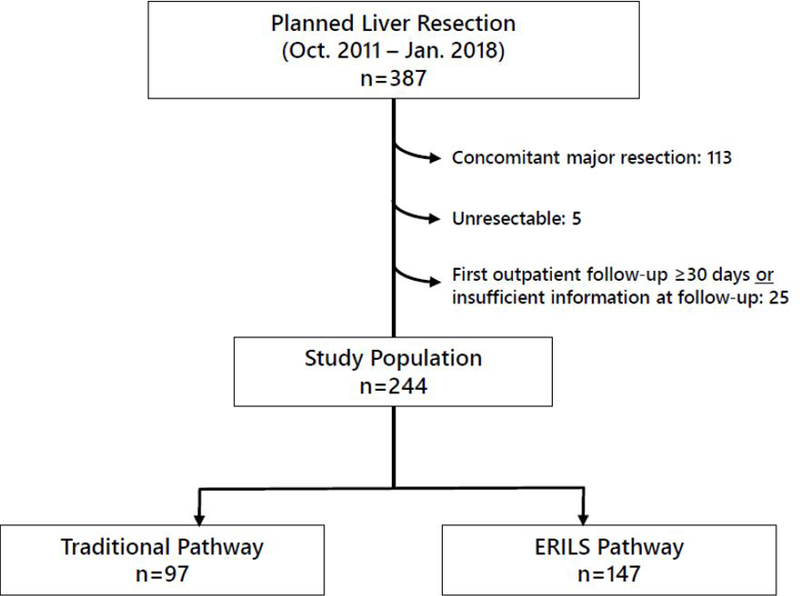

Of the 387 patients intended for liver resection during the designated time period, 244 patients met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The median age for the entire cohort was 55 years (IQR 46–62), 116 (48%) of whom were female. The median BMI was 27 kg/m2, and the vast majority of patients (91%) had an ASA classification of III. Ninety-five percent of patients underwent liver resection for a malignancy, with 127 (52%) undergoing resection of colorectal liver metastases. The next most common indications were cholangiocarcinoma ) 28 patients, 11%) and hepatocellular carcinoma (23,9%). On final pathology, 11 patients (5%) had benign disease, however, nine of these patients (82%) underwent resection out of concern for possible malignancy.

Figure 1.

Study Patient Inclusion [ERILS, Enhanced Recovery in Liver Surgery]

ERILS vs. Traditional Pathway Patients

Clinical characteristics comparing ERILS (147 patients) vs. traditional recovery pathway (97 patients) are shown in Table 2. Baseline demographics were comparable between groups, however ERILS patients were somewhat older (median age 57 vs. 52, p=0.031) and more likely to have higher ASA classification (ASA ≥ III for 96% ERILS vs. 86% of traditional pathway patients, p=0.010). Preoperative opioid use was similar between groups, including 17 ERILS (12%) and 14 traditional pathway (14%) patients (p=0.523).

Table 2.

Patient Factors, based on Recovery Pathway*

| Factor | Traditional (n=97) |

Enhanced Recovery (n=147) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | |||

| Age (years) | 52 (44, 60) | 57 (46, 63) | 0.031 |

| Sex, female | 51 (53) | 65 (44) | 0.201 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26 (24, 32) | 27 (24, 32) | 0.501 |

| ASA Class | 0.010 | ||

| II | 13 (13) | 6 (4) | |

| III | 84 (87) | 139 (95) | |

| IV | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| ECOG performance status | 0.064 | ||

| 0 | 71 (73) | 88 (60) | |

| 1 | 25 (26) | 57 (38) | |

| 2 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Opioid use | 14 (14) | 17 (12) | 0.523 |

| Perioperative | |||

| Regional anesthetic block | 68 (70) | 125 (85) | 0.008 |

| Open approach | 81 (84) | 92 (63) | <0.001 |

| Major hepatectomy† | 38 (39) | 40 (27) | 0.054 |

| Multivisceral operation‡ | 7 (7) | 5 (3) | 0.178 |

| Operative time (min) | 271 (175, 337) | 222 (157, 250) | 0.036 |

| Estimated blood loss (cc) | 150 (100, 250) | 150 (75, 25) | 0.249 |

| Duration of stay (days) | 6 (5, 7) | 4 (3, 6) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative | |||

| Any complication | 27 (28) | 33 (22) | 0.340 |

| Major complication§ | 9 (9) | 3 (2) | 0.011 |

| Bile leak | 2 (2) | 10 (7) | 0.094 |

| Wound infection | 6 (6) | 6 (4) | 0.535 |

| Organ space infection | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | 0.012 |

| Mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | −− |

Values listed as number (percentage) or median (interquartile range [IQR]).

Defined as resection of ≥3 contiguous liver segments.

Defined as minor concomitant operations involving an additional (non-liver) organ/structure.

Accordion Severity Grading System, Grade ≥3.

BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

In regard to perioperative factors, ERILS patients more frequently had a regional anesthetic block compared to traditional pathway patients (85% vs. 70%, p=0.008). Of the 125 ERILS patients who received a block, 52% had a TEA and 48% received a TAP block, whereas 97% of the 68 traditional pathway patients who received a block had TEA and only two (3%) received a TAP block. A smaller percentage of ERILS patients (63%) underwent an open operative approach, compared to 84% of traditional pathway patients (p<0.001). ERILS patients had a shorter hospital duration of stay(4 vs. 6 days, p<0.001) and a lesser rate of major complications (2% vs. 9%, p=0.011). The rates of bile leak, wound infection, and organ space infection were similar between the groups. There were no perioperative deaths in this patient cohort.

Postoperative Outpatient Opioid Utilization

Only 38 (26%) ERILS patients were discharged from the hospital with a prescription for a traditional opioid compared to 76 (79%) of traditional pathway patients (p<0.001). More ERILS patients were discharged with only tramadol (69% vs. 21%, p<0.001), and somewhat more ERILS patients were discharged with purely non-narcotic regimens (4% vs. 0%, p=0.043; Table 3).

Table 3.

Postoperative Opioid Prescriptions and Use based on Recovery Pathway*

| Traditional (n=97) |

Enhanced Recovery (n=147) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge Prescription† | |||

| Traditional opioid‡ | 76 (79) | 38 (26) | <0.001 |

| Tramadol | 20 (21) | 100 (69) | <0.001 |

| Anti-inflammatory only/No medication | 0 | 6 (4) | 0.043 |

| First Postoperative Visit | |||

| Pain Medication Use | |||

| Traditional opioid‡ | 59 (61) | 28 (19) | <0.001 |

| Tramadol | 17 (18) | 59 (40) | <0.001 |

| Anti-inflammatory only/No medication | 21 (22) | 60 (41) | 0.002 |

| Pain score§ | 2 (0, 4) | 2 (0, 3) | 0.500 |

| Time to visit | 10 (9, 13) | 10 (9, 12) | 0.049 |

Values listed as number (percentage) or median (interquartile range [IQR]).

Data available for 96 traditional patients (99%) and 144 ERILS patients (98%)

Includes oxycodone, hydrocodone, hydromorphone.

Data available for 90 traditional patients (93%) and 129 ERILS patients (88%)

The median time to first follow-up visit was 10 days for both groups. Information about patient-reported pain scores was available for 129 patients (88%) in the ERILS group and 90 (93%) in the traditional pathway group. At outpatient follow-up, the average pain score for both groups was 2 out of a 10-point scale (ERILS [IQR 0–3] vs. traditional [IQR 0–4]; p=0.500). Twenty-eight (19%) of ERILS patients reported a traditional opioid requirement at first-visit compared to 59 (61%) of traditional pathway patients (p<0.001). On sub-analysis of the patients not requiring traditional opioids at first postoperative visit, 60 (50%) of ERILS patients were taking tramadol for pain compared to 17 (45%) of traditional pathway patients (p=0.603). More ERILS patients (41%) patients were either taking no analgesic medication or only anti-inflammatory medications compared to 22% of traditional pathway patients (p=0.002).

On sub-analysis of only patients who underwent open-incision liver resection, nearly all patients (99%) received either a traditional opioid prescription or tramadol at discharge, however, ERILS patients were discharged on traditional opioids less frequently compared to non-ERILS pathway patients (34% vs. 79%, p<0.001). At the first postoperative visit, only 25% of open-approach ERILS patients reported using a traditional opioid compared to 63% of non-ERILS patients (p<0.001). There was no difference in open approach ERILS patients compared to traditional pathway patients (28% vs. 20%, p=0.193) concerning using only anti-inflammatory medications or no analgesia. As with the whole cohort, patient-reported pain scores were equivalent with a median score of 2/10 for both groups.

Multivariable analysis for factors contributing to traditional opioid requirement at the first postoperative outpatient visit is shown in Table 4 showing all factors with p<0.1 on univariate analysis for postoperative opioid use. Factors found to be independently predictive of traditional opioid use at first outpatient follow-up visit were preoperative opioid use (OR 6.1, CI 2.5–15.9; p<0.001), traditional recovery pathway (OR 6.4, 95% CI 3.5–12.1; p<0.001), and open surgical approach (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.2–5.6; p=0.011).

Table 4.

Factors Contributing to Postoperative Traditional Opioid Use*

| Factor | Opioid Use (n=87) |

No Opioid Use (n=157) |

Univariate | Multivariable | Odds Ratio |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≤ 50 (y) | 41 (47) | 46 (29) | 0.005 | 0.146 | ||

| Preoperative opioid use | 21 (24) | 10 (6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 6.1 | 2.5–15.9 |

| Traditional recovery pathway | 59 (68) | 38 (24) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 6.4 | 3.5–12.1 |

| Open approach | 74 (85) | 99 (63) | <0.001 | 0.011 | 2.6 | 1.2–5.6 |

| Major hepatectomy† | 36 (41) | 42 (27) | 0.021 | 0.366 | ||

| Multivisceral operation‡ | 7 (8) | 5 (3) | 0.093 | 0.300 | ||

| Major complication§ | 8 (9) | 4 (3) | 0.030 | 0.703 |

Designated as the time of first postoperative follow-up visit (median 10 days, IQR 9–13); only variables with p<0.1 on univariate analysis are shown in the table. ‘Traditional Opioid Use’ includes use of semi-synthetic opioids (hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone).

Defined as resection of ≥3 contiguous liver segments.

Defined as minor concomitant operations involving an additional (non-liver) organ/structure.

Accordion Severity Grading System, Grade ≥ 3.

DISCUSSION

In this study of patients undergoing mostly oncologic liver resection, the use of an enhanced recovery pathway resulted in decreased opioid use at the time of first postoperative follow-up. A decrease in outpatient utilization of traditional opioids from 61% to 19% translates into the elimination of 1860 pills with high addictive potential prescribed to a cohort of 147 patients. Importantly, despite the lesser opioid intake, both minimally invasive and open approach ERILS patients had similarly low patient-reported pain scores as the patients managed via the traditional recovery pathway. On multivariable analysis, the type of recovery pathway was the most significant factor contributing to opioid use, with patients treated on a traditional pathway having greater than 6 times the odds of requiring traditional opioids at the time of postoperative follow-up compared to those treated on the ERILS pathway.

There have been previous reports demonstrating the ability of enhanced recovery programs to decrease inpatient opioid utilization across various surgical specialties.21–25 ERAS in the setting of liver resection, specifically, has been shown to decrease inpatient opioid use.12, 13 To the authors knowledge, the present study is the first to analyze the effect of an enhanced recovery program on opioid use at the time of first postoperative outpatient follow-up. Likewise, in regard to the effect of ERAS on opioid discharge practices, there are very little published data, and the effect has been mixed.26–28 For example, a recent study by Brandal et al. determined that implementation of an ERAS program at their institution had no effect on opioid prescribing at discharge after colectomy despite substantial decreases in inpatient total morphine equivalents compared to pre-ERAS.27 In fact, 70% of patients in their study who had both low pain scores and low inpatient opioid use (without a preoperative opioid requirement) were still discharged with an opioid prescription. Other studies have demonstrated considerable variation and over-prescription of opioids after surgery.29, 30 According to a 2017 systematic review of studies using patient-reported data, post-surgical patients are highly unlikely to take the majority of opioid pills prescribed which creates the opportunities for community exposure to massive amounts of opioids.31

To be fully effective, the opioid-sparing component of ERAS must carry over into the discharge and post-discharge phases of care. In this study, ERILS patients were substantially less likely to require a traditional opioid prescription at the time of discharge, demonstrating that this is a feasible goal. After ERILS implementation, opioid minimization became the standard of care, with patients requiring traditional opioids at discharge becoming the exception rather than the rule. This change of mindset resulted in the substantial differences in opioid-prescribing observed in this study.

It should be noted that ERILS patients were more likely to be prescribed tramadol. Tramadol is classified as a synthetic opiate-like narcotic characterized by a notable decrease in euphoria compared to the effect of traditional opioid medications. Although tramadol does have potential for abuse,32 its relatively lesser addictive potential compared to other agents has been proven in both animal and human studies that indicate an addiction risk in less than 3% of users and 0.1% of previously opiate-naïve users.17, 33, 34 The analysis presented in this study which found that patients managed via the tramadol-associated ERILS pathway were substantially less likely to require traditional opioids and/or any opioids at postoperative follow-up supports the use of this medication within a multimodality, opioid-sparing regimen. The analysis further suggests that more wide-spread adoption of similar strategies could favorably impact the current nationwide opioid crisis by decreasing rates of opioid dependence in cancer surgery patients.5, 6 In addition, increasing evidence that opioids stimulate cancer cell growth and activate metastatic pathways indicates the possibility that decreasing overall opioid use may contribute to improved cancer-specific survivals.35–37

In addition to type of recovery pathway, preoperative opioid use and type of surgical approach were other factors predicting a greater likelihood of postoperative opioid requirement (OR 6.1 and OR 2.6, respectively). While the finding that preoperative opioid use predicts postoperative opioid use is not surprising or novel,38, 39 it does highlight the importance of a preoperative pain evaluation and presents an opportunity to identify patients at-risk for continued long-term opioid use postoperatively.38 More research is needed to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of preoperative opioid tapering prior to surgery, and multi-disciplinary pain management teams should be formed to assist with this vulnerable population.3

Regarding the operative approach, the observed positive impact of minimally invasive surgery on opioid use is consistent with current literature describing experiences in liver surgery and other subspecialties and emphasizes that these approaches should be utilized whenever possible.40–42 Perhaps more importantly, sub-analysis of only those patients who underwent an open approach determined that the impact of ERILS on the observed decrease in opioid use was retained. Because it is not always possible to use a minimally-invasive approach in complex, often re-operative, oncologic surgery, enhanced recovery strategies (including the use of regional nerve blocks) may be most beneficial in these patients, allowing the exposure necessary to safely and effectively complete the resection while replicating the recovery experience traditionally associated with a limited-incision approach.

The implementation of enhanced recovery programs has improved perioperative outcomes after oncologic surgery.43 Our study emphasizes the importance of extending ERAS principles beyond discharge, which requires both education and compliance. Compliance measures need to be in place in order to measure outcomes accurately that are associated with ERAS implementation. One limitation of this study is that it includes our ERILS implementation “phase-in” period. To manage this issue, we performed a detailed chart review and used strict criteria to differentiate between the components of their perioperative care in order to declare a patient on the ERILS pathway as described. In addition, prior to creation of the ERILS protocol, separate enhanced recovery components were being adopted. For example, 70% of patients in the traditional pathway received a regional anesthetic block. The implication is that traditional pathway patients were exposed frequently to individual elements of an enhanced recovery pathway. Given the magnitude of effect on opioid utilization, the presence of partial pathway patients in the traditional cohort only strengthens the conclusion that complete pathway implementation has marked benefits.

Similarly, advances in both operative technique and other aspects of perioperative management over time may have played a role in the improvement in outcomes for ERILS patients. This effect is demonstrated both by the lesser percent of patients undergoing a major hepatectomy in the ERILS group in favor of parenchymal-sparing approaches and the greater number of ERILS patients undergoing minimally invasive liver resections. Independent of these practice evolutions, this study demonstrated that a multimodal regimen incorporating regional blocks and patient education nearly eliminated traditional opioids from practice, while still providing excellent pain control.

CONCLUSIONS

In this analysis of patients undergoing liver resection at a major cancer referral center, patients managed with an enhanced recovery pathway were substantially less likely to require opioid medications at postoperative outpatient follow-up compared to patients managed on a traditional care pathway, with no increase in patient-reported pain. The direct impact of this finding is that this enhanced recovery pathway has the potential to decrease persistent opioid dependence in this and other similar, at-risk patient populations. Likewise, with the enhanced recovery patients being substantially less likely to even receive an at-discharge opioid prescription, the opportunity for excess unused opioids to enter and harm both the patient and the community can be avoided. Combined, these benefits further support the widespread implementation of enhanced recovery into surgical practice.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Brigitte M. Taylor (Department of Surgical Oncology, MD Anderson Cancer Center) for administrative assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health T32 CA 009599 and the MD Anderson Cancer Center support grant (P30 CA016672).

List of Abbreviations

- ERILS

Enhanced Recovery in Liver Surgery

- ERAS

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery

- BMI

body mass index

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- TEA

thoracic epidural analgesia

- TAP

transversus abdominis plane

Footnotes

This work was presented at the American College of Surgeons Annual Clinical Congress, Boston, MA, October 2018.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures: All authors (Drs. Lillemoe, Marcus, Day, Kim, Narula, Davis, Gottumukkala, Aloia) report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest associated with this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths--United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2016; 64: 1378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Florence CS, Zhou C, Luo F, Xu L. The Economic Burden of Prescription Opioid Overdose, Abuse, and Dependence in the United States, 2013. Med Care 2016; 54: 901–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hah JM, Bateman BT, Ratliff J, Curtin C, Sun E. Chronic Opioid Use After Surgery: Implications for Perioperative Management in the Face of the Opioid Epidemic. Anesth Analg 2017; 125: 1733–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, Moser S, Lin P, Englesbe MJ, et al. New Persistent Opioid Use After Minor and Major Surgical Procedures in US Adults. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JS-J, Hu HM, Edelman AL, Brummett CM, Englesbe MJ, Waljee JF, et al. New Persistent Opioid Use Among Patients With Cancer After Curative-Intent Surgery. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2017; 35: 4042–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuminello S, Schwartz R, Liu B, et al. Opioid use after open resection or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for early-stage lung cancer. JAMA Oncology 2018; 4: 1611–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Schwenk W, Demartines N, Roulin D, Francis N, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colonic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(R)) Society recommendations. Clin Nutr 2012; 31: 783–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melloul E, Hubner M, Scott M, Snowden C, Prentis J, Dejong CH, et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Liver Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations. World J Surg 2016; 40: 2425–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lassen K, Coolsen MM, Slim K, Carli F, de Aguilar-Nascimento JE, Schafer M, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care for pancreaticoduodenectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(R)) Society recommendations. Clin Nutr 2012; 31: 817–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerantola Y, Valerio M, Persson B, Jichlinski P, Ljungqvist O, Hubner M, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(R)) society recommendations. Clin Nutr 2013; 32: 879–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ni TG, Yang HT, Zhang H, Meng HP, Li B. Enhanced recovery after surgery programs in patients undergoing hepatectomy: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21: 9209–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page AJ, Gani F, Crowley KT, Lee KH, Grant MC, Zavadsky TL, et al. Patient outcomes and provider perceptions following implementation of a standardized perioperative care pathway for open liver resection. Br J Surg 2016; 103: 564–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant MC, Sommer PM, He C, Li S, Page AJ, Stone AB, et al. Preserved Analgesia With Reduction in Opioids Through the Use of an Acute Pain Protocol in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery for Open Hepatectomy. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine 2017; 42: 451–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. American journal of clinical oncology 1982; 5: 649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pang YY. The Brisbane 2000 terminology of liver anatomy and resections. HPB 2000; 2:333–39. HPB (Oxford). 2002; 4: 99; author reply −100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. The accordion severity grading system of surgical complications. Ann Surg 2009; 250: 177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams EH, Breiner S, Cicero TJ, Geller A, Inciardi JA, Schnoll SH, et al. A comparison of the abuse liability of tramadol, NSAIDs, and hydrocodone in patients with chronic pain. Journal of pain and symptom management 2006; 31: 465–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Day RW, Cleeland CS, Wang XS, Fielder S, Calhoun J, Conrad C, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes Accurately Measure the Value of an Enhanced Recovery Program in Liver Surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 221: 1023–30 e1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wick EC, Grant MC, Wu CL. Postoperative Multimodal Analgesia Pain Management With Nonopioid Analgesics and Techniques: A Review. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 691–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narula N, Kim BJ, Davis CH, Dewhurst WL, Samp LA, Aloia TA. A proactive outreach intervention that decreases readmission after hepatectomy. Surgery 2018; 163: 703–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarez MP, Foley KE, Zebley DM, Fassler SA. Comprehensive enhanced recovery pathway significantly reduces postoperative length of stay and opioid usage in elective laparoscopic colectomy. Surgical endoscopy 2015; 29: 2506–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu W, Daneshmand S, Bazargani ST, Cai J, Miranda G, Schuckman AK, et al. Postoperative Pain Management after Radical Cystectomy: Comparing Traditional versus Enhanced Recovery Protocol Pathway. The Journal of urology 2015; 194: 1209–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Modesitt SC, Sarosiek BM, Trowbridge ER, Redick DL, Shah PM, Thiele RH, et al. Enhanced Recovery Implementation in Major Gynecologic Surgeries: Effect of Care Standardization. Obstetrics and gynecology 2016; 128: 457–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller TE, Thacker JK, White WD, Mantyh C, Migaly J, Jin J, et al. Reduced length of hospital stay in colorectal surgery after implementation of an enhanced recovery protocol. Anesth Analg 2014; 118: 1052–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King AB, Spann MD, Jablonski P, Wanderer JP, Sandberg WS, McEvoy MD. An enhanced recovery program for bariatric surgical patients significantly reduces perioperative opioid consumption and postoperative nausea. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Rojas KE, Manasseh DM, Flom PL, Agbroko S, Bilbro N, Andaz C, et al. A pilot study of a breast surgery Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol to eliminate narcotic prescription at discharge. Breast cancer research and treatment 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Brandal D, Keller MS, Lee C, Grogan T, Fujimoto Y, Gricourt Y, et al. Impact of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery and Opioid-Free Anesthesia on Opioid Prescriptions at Discharge From the Hospital: A Historical-Prospective Study. Anesth Analg 2017; 125: 1784–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerrish AW, Fogel S, Lockhart ER, Nussbaum M, Adkins F. Opioid prescribing practices during implementation of an enhanced recovery program at a tertiary care hospital. Surgery 2018; 164: 674–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, Barth RJ Jr. Wide Variation and Excessive Dosage of Opioid Prescriptions for Common General Surgical Procedures. Ann Surg 2017; 265: 709–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiels CA, Anderson SS, Ubl DS, Hanson KT, Bergquist WJ, Gray RJ, et al. Wide Variation and Overprescription of Opioids After Elective Surgery. Ann Surg 2017; 266: 564–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feinberg AE, Chesney TR, Srikandarajah S, Acuna SA, McLeod RS. Opioid Use After Discharge in Postoperative Patients: A Systematic Review. Ann Surg 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Miotto K, Cho AK, Khalil MA, Blanco K, Sasaki JD, Rawson R. Trends in Tramadol: Pharmacology, Metabolism, and Misuse. Anesth Analg 2017; 124: 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence: Thirty-sixth report Geneva, World Health Organization, 2014. Available https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/6_1_Update.pdf [accessed 17 Jan 2019]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Epstein DH, Preston KL, Jasinski DR. Abuse liability, behavioral pharmacology, and physical-dependence potential of opioids in humans and laboratory animals: lessons from tramadol. Biological psychology 2006; 73: 90–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lennon FE, Mirzapoiazova T, Mambetsariev B, Poroyko VA, Salgia R, Moss J, et al. The Mu opioid receptor promotes opioid and growth factor-induced proliferation, migration and Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in human lung cancer. PLoS One 2014; 9: e91577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta K, Kshirsagar S, Chang L, Schwartz R, Law PY, Yee D, et al. Morphine stimulates angiogenesis by activating proangiogenic and survival-promoting signaling and promotes breast tumor growth. Cancer research 2002; 62: 4491–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans MT, Wigmore T, Kelliher LJS. The impact of anaesthetic technique upon outcome in oncological surgery. BJA Education 2019; 19: 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carroll I, Barelka P, Wang CK, Wang BM, Gillespie MJ, McCue R, et al. A pilot cohort study of the determinants of longitudinal opioid use after surgery. Anesth Analg 2012; 115: 694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raebel MA, Newcomer SR, Reifler LM, Boudreau D, Elliott TE, DeBar L, et al. Chronic use of opioid medications before and after bariatric surgery. Jama 2013; 310: 1369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mala T, Edwin B, Gladhaug I, Fosse E, Soreide O, Bergan A, et al. A comparative study of the short-term outcome following open and laparoscopic liver resection of colorectal metastases. Surgical endoscopy 2002; 16: 1059–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelly KJ, Selby L, Chou JF, Dukleska K, Capanu M, Coit DG, et al. Laparoscopic Versus Open Gastrectomy for Gastric Adenocarcinoma in the West: A Case-Control Study. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22: 3590–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mansour AM, El-Nahas AR, Ali-El-Dein B, Denewar AA, Abbas MA, Abdel-Rahman A, et al. Enhanced Recovery Open vs Laparoscopic Left Donor Nephrectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Urology 2017; 110: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marcus RK, Lillemoe HA, Rice DC, Mena G, Bednarski BK, Speer BB, et al. Determining the Safety and Efficacy of Enhanced Recovery Protocols in Major Oncologic Surgery: An Institutional NSQIP Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]